Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Procurement of Fuels, Petroleum, Oils, Lubricants, and Card Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

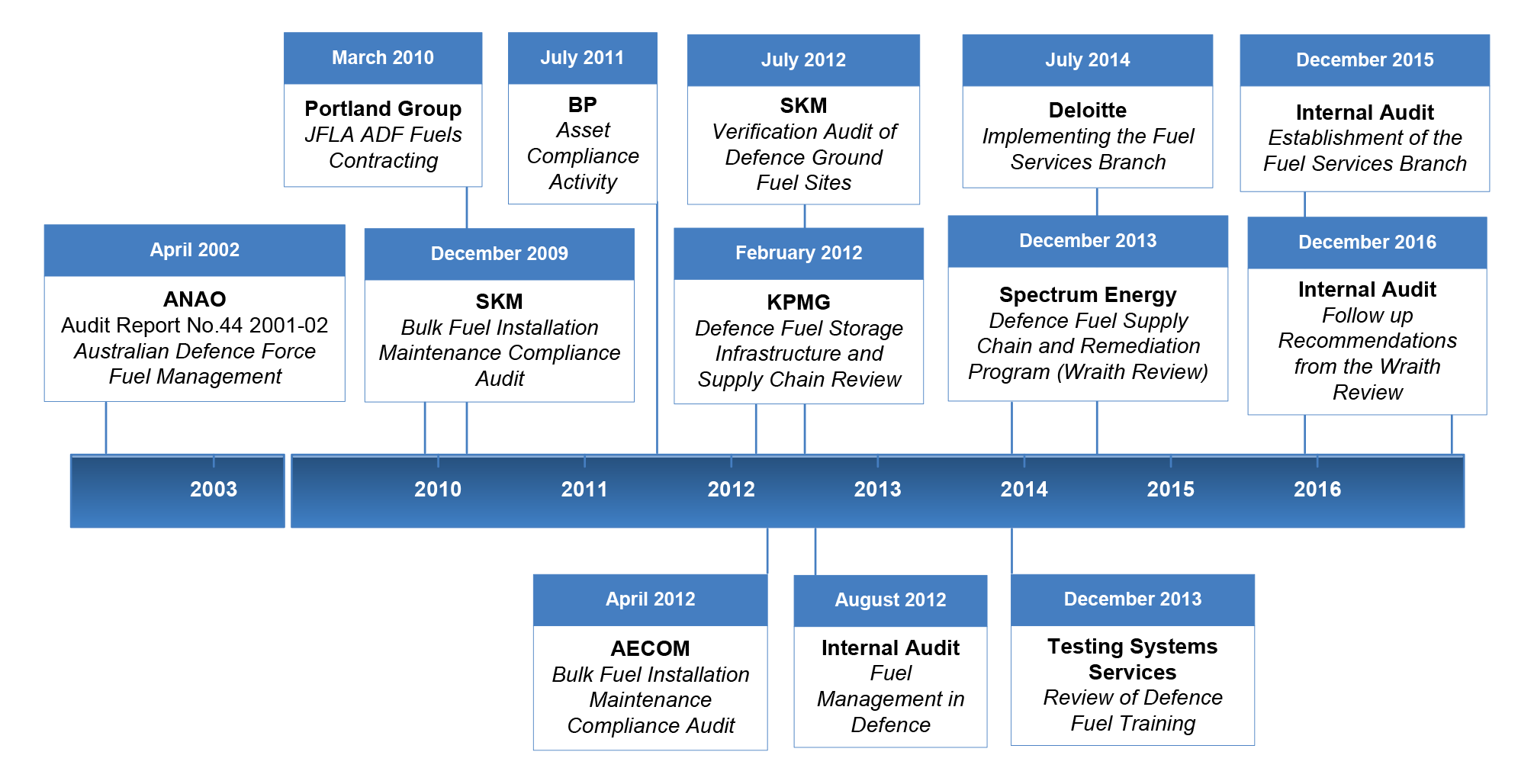

The audit objective was to assess whether Defence achieves value for money in the procurement of fuels.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Defence Force (Defence) procures, stores and distributes a combination of ten commercial and military grade fuels and lubricants to geographically dispersed locations to maintain the mobility of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Military specification fuels include additives that Defence considers essential for the operation of its ships, aircraft and vehicles, often in demanding environments.

2. Fuel is Defence's largest single commodity expenditure, amounting to an annual spend of approximately $423 million in 2016-17. In 2015, Defence undertook an open tender exercise to secure supplies of bulk fuels, petroleum, oils and lubricants, and fuel cards for the five year period from February 2016 until February 2021.

3. Defence's fuel supply chain has been the subject of numerous reviews over the past 15 years, both internal and external. These reviews have consistently identified weaknesses in Defence's fuel supply chain management.

4. The scope of this audit focuses on the 2015 procurement of bulk fuel, petrol, oil and lubricants and fuel card services. The audit also examines Defence's contract management arrangements and the controls framework for Defence's fuel inventory.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence achieves value for money in the procurement of fuel. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- procurement processes complied with the Commonwealth procurement framework and relevant Defence requirements; and

- Defence's contracting and purchasing arrangements achieve value for money for the Commonwealth.

Conclusion

6. Defence designed and implemented an effective competitive tender process but did not develop a negotiation strategy to maximise value for money and there remains scope to improve the effectiveness of contract management, purchasing and assurance arrangements to demonstrate that value for money is being achieved.

7. Defence's open tender and evaluation processes were fit for purpose. The processes were largely compliant with Commonwealth and Defence requirements. While the fuel pricing formula applied was industry standard, Defence was unable to demonstrate that value for money was maximised as Defence did not seek to negotiate lower prices for some components of the pricing formula before supply contracts were signed.

8. Defence's contract management would benefit from improved integration of key information systems and reduced manual intervention, including in the calculation of fuel prices.

9. Defence's ability to provide assurance over the management of its fuel supply chain is limited by infrastructure and information technology deficiencies and insufficient central data analysis. Defence is currently implementing some short-term initiatives to improve central oversight, however significant systems level improvement regarding assurance controls is not scheduled to commence until 2022.

Supporting findings

The Commonwealth procurement framework and Defence's internal requirements

10. Defence's procurement process for bulk fuel was largely compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and Defence's internal requirements. Weaknesses in administration related to:

- conflict of interest management—while Defence developed clear probity and conflict of interest plans, Defence did not appropriately manage a declared potential conflict of interest in relation to a key person on the Tender Evaluation Team;

- risk management procedures—a risk register for the procurement was developed early in the tender process, however it was not updated at key milestones during the process or when new risks emerged; and

- records management—Defence produced and retained all official evaluation reports but was unable to locate various working files and meeting records for the purposes of this audit.

The tender evaluation process

11. The complexity of the procurement was significant, with detailed requirements for over 100 geographically dispersed sites, multiple fuel types and several service requirements.

12. Defence's design of the tender evaluation process was fit for the purpose of dealing with this complexity. The Tender Evaluation Plan provided for multiple assessment stages, specialist working groups and comprehensive criteria.

13. Defence implemented the evaluation process and stages as outlined in its Tender Evaluation Plan. It produced the documents required for each stage of the evaluation and weighted criteria in line with the advice provided to tenderers. However, the clarity and transparency of Defence's decision making was reduced by a lack of adequate records underpinning the outcomes as determined by the tender evaluation working groups.

Value for money assessment

14. The 2015 fuels tender and evaluation process was designed to produce a value for money outcome. Defence undertook an open tender process, conducted detailed evaluation of tenders, considered price and non-price value, and applied an industry standard fuel pricing methodology.

15. Defence's failure to negotiate to attempt to achieve lower prices for some components of the fuel pricing formula before supply contracts were signed compromised its ability to demonstrate that value for money was maximised for the Commonwealth.

Managing the bulk fuel contracts

16. Defence's processes and controls over the calculation of fuel prices do not provide adequate assurance, with manual processes supplementing inadequate information technology systems. Defence's fuel management inventory system is still not fully integrated with Defence's financial management system.

17. Defence relies on a range of documents to guide contract management and oversight of each supplier's performance. Development of an internal procedural guidance document would assist staff and provide a source of corporate knowledge.

18. While Defence recognised that it required skills in the fuels services area not immediately available to it on the establishment of the Fuel Services Branch, it continues to rely heavily on contracted services at high cost.

Inventory management and assurance

19. Although Defence has some inventory management controls in place—such as physical security at large fuel installations—key elements of Defence's controls and assurance processes to detect volume discrepancies remain ineffective. Central data analysis is insufficient, and infrastructure and information technology systems require modernisation. These deficiencies have been known about for several years.

20. Defence is undertaking corrective action to enhance assurance controls and to better manage bulk fuel stocks pending more permanent reforms, which are planned as part of the Defence Fuels Transformation Program.

21. The development of a more contemporary and integrated system for collecting and storing fuel inventory data would strengthen risk management, the control and assurance framework and support more informed fuel purchasing decisions. Improvements to relevant infrastructure, IT and controls under the Defence Fuels Transformation Program are not scheduled to commence until 2022.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.39

That, for future procurements within the Fuels Services Branch, Defence:

- explicitly considers the potential conflicts of interest that may arise when employing individuals and contractors with recent industry experience; and institutes controls to ensure that all such matters are fully managed and documented;

- reviews and updates procurement risk registers at a minimum at all key decision points and milestones, when risk events materialise and as new risks arise throughout a procurement; and

- strengthen risk and records management by ensuring that all personnel involved are aware that tenders and related documents cannot be removed from Defence's classified systems without express authority by senior management.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.89

That for future procurements within the Fuels Services Branch, Defence conducts an independent evaluation of the 2015 fuel procurement process, strategy and arrangements to inform the next procurement process and to maximise a value for money outcome.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.43

To improve the management of its bulk fuel inventory, Defence should implement arrangements to provide assurance that control arrangements are working as intended.

Summary responses

22. A summary response from the Department of Defence is set out below. Kiah Consulting was provided with extracts of the draft report and its summary comments are also set out below.

Department of Defence

23. Defence welcomes the ANAO Audit Report into the Procurement of Fuels, Oils, Lubricants and Card Services and agrees with the recommendations.

24. Defence is satisfied with the value for money outcome achieved from the procurement process. In addition to price, Defence sought fuel suppliers which could provide Defence with assured cost-effective supply solutions that featured flexibility in meeting routine and surge requirements as well as support through alternate supply options or storage. The fundamental objective of the procurement process was the need for Defence fuel supply contracts to be able to supply volumes of fuel products as required by Defence to various physical locations across Australia within specific timelines.

25. Defence notes the recommendations provided build upon the progress currently being made by Defence across the Defence fuel supply chain. Many of these outcomes have stemmed from the Defence Fuel Network Review which was completed in June 2017. This review delivered an Implementation Strategy for the Future Defence Fuel Supply Chain; which led to the establishment of the Defence Fuel Transformation program to execute the Implementation Strategy. The Defence Fuel Transformation program is fully funded and Defence will be seeking Government endorsement later this year to progress this activity.

Kiah consulting

26. We appreciate the opportunity to make comment on the observations regarding probity and use of consultants that reflect on Kiah.

27. We seek to be clear that any probity process failure was outside of our influence and that we took care to ensure that any perceived conflict of interest was declared. While there may be some concern as to the process, we do observe that a purchaser turned supplier may present a conflict, but a 'poacher turned gamekeeper' simply makes for a knowledgeable consultant, however discomforted the suppliers may feel.

28. The view that consultants should be replaced by public servants is without foundation. We provide a managed services work program using consultants drawn from industry senior executives. Kiah consultants are working alongside Defence to re-establish a self-reliant Defence capability, operating safely to contemporary standards. This is not a role that can be achieved from within the public sector without assistance. The lack of expertise is what gave rise to the issues being addressed and the public sector simply cannot internally generate the expertise it needs.

29. When Defence urgently sought to establish the Fuels Services Branch (FSB), they leveraged two existing contracts. Since FSB has been established we have been competed three times, in addition to the competitive establishment of the panels. We have been awarded two contracts and a portion of a third, with Kiah providing about 50% of the overall consulting effort. We have repeatedly demonstrated our comparative value through competition.

30. The value of our contribution is also demonstrable and measureable. At a cost of around $4m a year, effort and skills varying according to need, we have delivered contemporary industry practices at a fraction of what it cost industry when developed for them. We have been instrumental in delivering $15m pa savings in operating costs and at least $200m of avoided infrastructure spend. None of it would have been achievable by Defence without the introduction of diversity of thought and industry experience that we provide – otherwise the benefits would have been reaped already.

31. Defence has acted engaged wisely, sought competition and established a model that integrates Defence and the consultants for sustainable outcomes and knowledge transfer. We are disappointed that this is not recognised in the report.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by entities when managing procurements and large inventories.

Procurement

Records management

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Supplies, including fuel, are a fundamental input to Defence capability. Defence procures, stores and distributes fuel to geographically dispersed locations to maintain the mobility of the Australian Defence Force. Defence uses a combination of ten commercial and military grade fuels.1 Military specification fuels include additives that Defence considers essential for the operation of its ships, aircraft and vehicles, often in demanding environments.

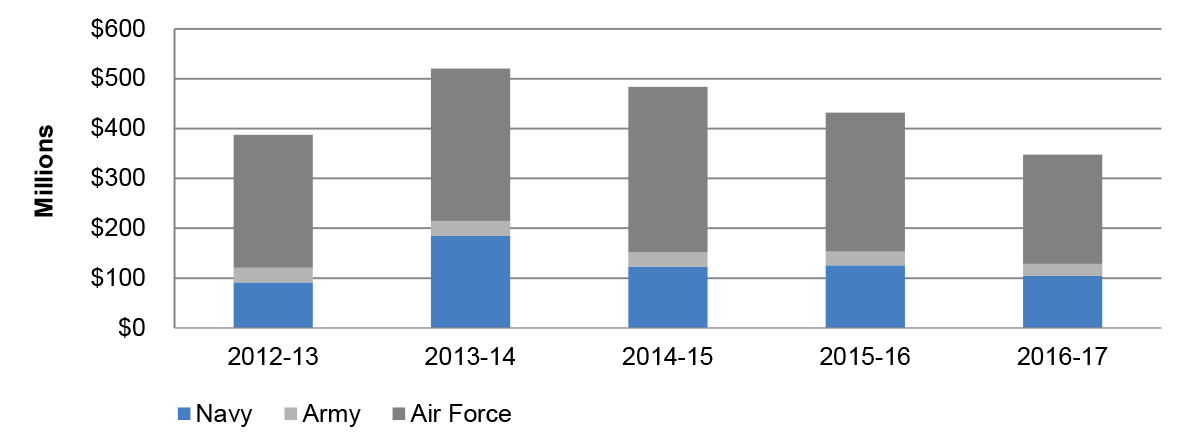

1.2 Fuel is Defence's largest single commodity expenditure. Primarily, Defence purchases fuel in bulk, with the majority of fuel consumed by Air Force and then Navy, with Army being the smallest consumer. The majority of this demand is for military specific grades of fuel for which Defence is the sole Australian customer.

1.3 Key statistics about Defence's fuel arrangements are:

- 107 fuel sites, with the capacity to store 167 million litres (ML);

- a requirement for seven different types of fuel, including three military specification fuels (MilSpec);

- annual fuel consumption of 423 ML (2016–2017), equivalent to 0.9 per cent of total fuel consumption in Australia (2015–16);

- the largest user of fuel by service is Air Force, which consumes approximately 70 per cent of total fuel; and

- an annual spend on fuel of approximately $423 million.

1.4 Figure 1.1 shows the cost of fuel and lubricants purchased by Defence from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2017. Over this period, Defence spent $2.1 billion on fuel and lubricants, including $630 million by Navy, $139 million by Army and $1.4 billion by Air Force.

Figure 1.1: Total cost of fuel ($m), by Service, 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2017

Source: Defence documents.

1.5 Table 1.1 summarises the estimated contract values for bulk fuels and related products over five years from Defence's seven suppliers. Financial approvals at contract signature totalled $1.9 billion, but actual contract values will depend on prices at the time of delivery.

Table 1.1: Summary of approved estimated deed values (February 2016–February 2021)

|

Company |

Estimated value ($, millions AUD, five year period) |

|

Caltex |

867.4 |

|

Viva Energy |

491.1 |

|

BP |

401.7 |

|

Viva Energy Aviation (formerly Shell Aviation) |

119.1 |

|

AS Harrison |

8.2 |

|

World Fuel Services |

5.6 |

|

Interchem |

3.2 |

|

Total (over five years) |

1896.3 |

Source: Defence documentation

1.6 These contracts and the related procurements are administered by the Fuel Services Branch within Defence's Joint Logistics Command Group.

Audit objective and criteria

1.7 The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence achieves value for money in the procurement of fuel. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- procurement processes complied with the Commonwealth procurement framework and relevant Defence requirements; and

- Defence's contracting and purchasing arrangements achieve value for money for the Commonwealth.

1.8 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed relevant Defence files and documentation, including contracts, policies, briefs and performance reports;

- collected and analysed data relating to the bulk fuel contracts; and

- interviewed key Defence personnel including: Commander Joint Logistics; members of the Fuel Services Branch; relevant stakeholders; and representatives from each of the Services.

Audit scope

1.9 The scope of this audit includes Defence's 2015 procurement of bulk fuel, petrol, oil and lubricants and fuel card services; and the subsequent management of relevant contracts. It also examines aspects of the controls framework for Defence's bulk fuel inventory.

1.10 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $472,467.

1.11 The team members for this audit were Dr Marlene Edmondson, Robina Jaffray, Dr Ashlin Lee, Jed Andrews and David Brunoro.

2. The fuel procurement process

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether Defence's 2015 procurement process for the purchase of fuel was designed and implemented to achieve value for money for the Commonwealth.

Conclusion

Defence's open tender and evaluation processes were fit for purpose. The processes were largely compliant with Commonwealth and Defence requirements. While the fuel pricing formula applied was industry standard, Defence was unable to demonstrate that value for money was optimised as Defence did not seek to negotiate lower prices for some components of the pricing formula before supply contracts were signed.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at improving Defence's administration of probity issues, risk management and document security during procurements. A further recommendation is directed towards conducting an independent evaluation of the 2015 fuels procurement process to inform the next procurement.

2.1 This chapter considers:

- whether the 2015 procurement process complied with the Commonwealth procurement framework and relevant Defence requirements, focusing on:

- the procurement strategy;

- procurement planning and governance;

- probity arrangements;

- risk management;

- records management;

- whether the tender evaluation process was fit for purpose; and

- whether Defence achieved value for money.

Did the procurement process follow the Commonwealth's procurement framework and Defence requirements?

Defence's procurement process for bulk fuel was largely compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and Defence's internal requirements. Weaknesses in administration related to:

- conflict of interest management—while Defence developed clear probity and conflict of interest plans, Defence did not appropriately manage a declared potential conflict of interest in relation to a key person on the Tender Evaluation Team;

- risk management procedures—a risk register for the procurement was developed early in the tender process, however it was not updated at key milestones during the process or when new risks emerged; and

- records management—Defence produced and retained all official evaluation reports but was unable to locate various working files and meeting records for the purposes of this audit.

The Commonwealth procurement framework and Defence's internal requirements

2.2 Defence procurement is governed by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules2 and Defence's Procurement Policy Manual. Risk management, an integral part of procurement, is governed by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy3 and Defence's Project Risk Management Manual. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules contain both mandatory requirements and good practice to assist agencies in their procurement activities. The Rules are issued by the Minister for Finance and apply to all Australian Public Service procurements.

2.3 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.4 In achieving value for money, procurements should:

- encourage competition and be non-discriminatory;

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth;

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision making;

- encourage appropriate engagement with risk; and

- be commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.

2.4 Defence has developed its own Defence Procurement Policy Manual which is 'the principal compliance document for Defence officials conducting procurement'.5 The purpose of the Defence Procurement Policy Manual is to assist Defence officials to comply with the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and Defence policy when undertaking procurements and to provide general guidance around the process, such as using plain English and encouraging officials to use 'a strategic approach and commercial expertise'.6

Procurement strategy

2.5 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules provide that a 'consideration of value for money begins by officials clearly understanding and expressing the goals and purpose of the procurement'. The Director General of Fuel Services approved a procurement strategy for fuel contracts on 21 May 2015. Reflecting the broader Commonwealth Procurement Rules, Defence's fuels procurement strategy aimed to: provide demonstrable value for money benefits to Defence; encourage competition; facilitate accountable and transparent decision making; encourage appropriate engagement with risk; and be commensurate with the scale and scope of Fuel Services Branch business requirements.

2.6 The conditions of tender included the following objectives for the procurement:

- support for the Australian Defence Force fuel supply chain vision of safe sustained delivery of an efficient, effective, integrated and professional fuel and petroleum, oils and lubricants supply chain that supports the operational needs of the ADF;

- surety of supply: at all locations; within and across the greatest number of delivery methods; for the maximum range of supplies; and with a minimum number of contractors;

- best value for money in accordance with the evaluation criteria; and

- provide the range of supplies through a prime contractor relationship with the Commonwealth.

Procurement planning and governance

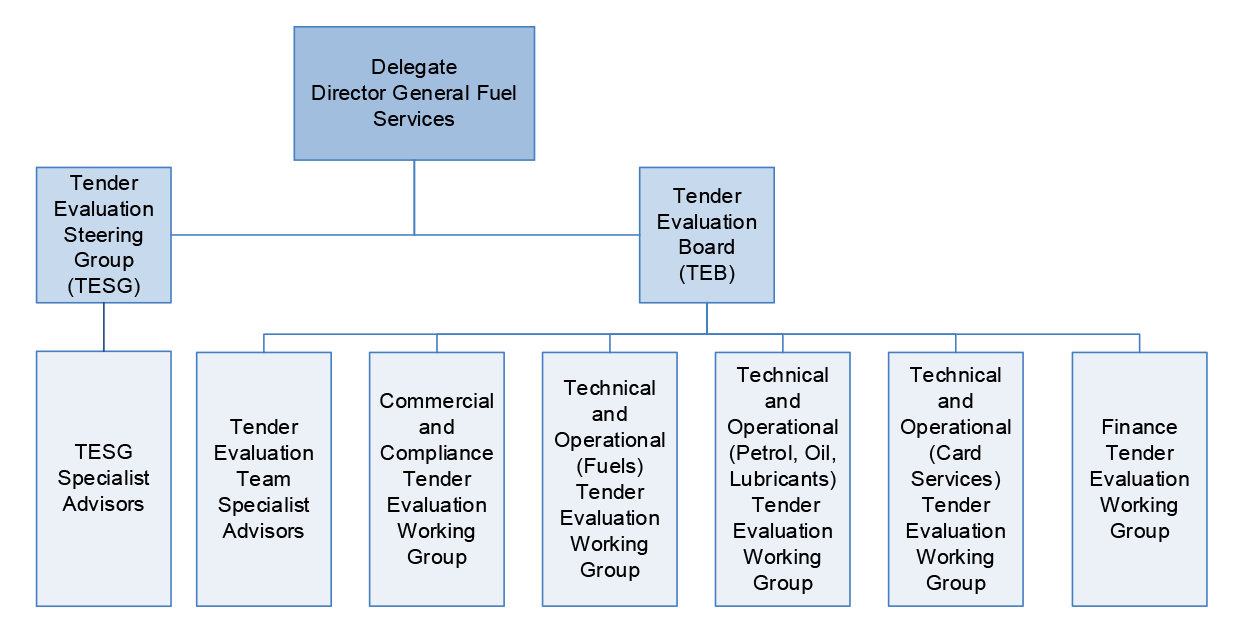

2.7 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules provide that accountability and transparency in procurement is achieved through effective planning and governance. In addition to the tender documentation prepared by Defence for listing on AusTender, Defence prepared a tender evaluation plan, probity plan and risk documentation. The tender evaluation plan established the criteria, processes and methodologies through which tenders were to be assessed for the supply of fuel. It also defined the roles and responsibilities of the Tender Evaluation Team, which comprised the Tender Evaluation Board and seven tender evaluation working groups.7 Independent probity and procurement advice was also available. Governance arrangements for the tender are presented in Figure 2.1 below.

Figure 2.1: Tender governance arrangements

Source: Defence Tender Evaluation Plan.

2.8 The Tender Evaluation Team was required to:

- conduct evaluations of each of the tenders in accordance with the tender evaluation plan;

- evaluate all tenders ethically and fairly;

- undertake the detailed evaluation according to the evaluation criteria; and

- prepare narratives, summaries and reports.

2.9 The Tender Evaluation Board had responsibility for overseeing the working groups and the production of a Source Evaluation Report which provided final recommendations to the delegate. The Board comprised the Tender Evaluation Team Chair and Deputy Chair, and leaders of the working groups—totalling four personnel.8 The Tender Evaluation Working Groups conducted detailed evaluations and included officers/contractors with specialist expertise.9

2.10 The Tender Evaluation Plan stated that the Tender Evaluation Steering Group's role was to provide advice to the delegate and the tender evaluation team to ensure 'that the [Tender Evaluation Team] complied with Commonwealth policies including [the Commonwealth Procurement Rules] and Department policies, procedures and practices to ensure achievement of [value for money]'.10 The Steering Group comprised three members: the Chair of the 2010 procurement; Defence's Chief Procurement Officer; and the 2015 Tender Evaluation Board Chair.

2.11 Defence was unable to provide minutes or meeting records for the Tender Evaluation Working Groups or Tender Evaluation Steering Group. Consequently, there is no visibility of the advice provided by the Tender Evaluation Steering Group, and it is not possible to confirm that the Tender Evaluation Steering Group met on two occasions as required by the Tender Evaluation Plan. As required in the Tender Evaluation Plan, the Steering Group endorsed the Source Evaluation Report, prepared by the Tender Evaluation Board, on 11 November 2015.11

Probity management

2.12 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules require the ethical administration of procurement, including the identification and management of conflicts of interest and the equitable treatment of participants.

2.13 A comprehensive probity plan was finalised in July 2015. The plan set out the authority and structure to address probity issues in relation to the fuels procurement. The plan provided that:

a. there is to be a clear and fair procurement process that is conducted in accordance with applicable Commonwealth legislation and policy;

b. all tenderers are to be treated fairly and equitably…;

c. tender evaluation is to be conducted in accordance with the approved Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP);

d. commercially sensitive information… is to be protected at all times;

e. there must be a clear audit trail; and

f. perceived, potential and actual conflicts of interest must be identified and addressed.

2.14 The probity plan also provided for the appointment of an independent probity advisor and set out the scope of the advisor's role. The probity advisor was consulted on a number of occasions for advice on matters such as: alternative tenders; requests from tenderers for clarification after closure of the tender submission date; screening queries; the appropriateness and accuracy of advice to tenderers during the process; and conflict of interest management.

Conflict of interest management

2.15 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules require officials to act ethically throughout the procurement.12 Defence also has specific instructions on managing potential conflicts of interest, which apply to Defence personnel and external service providers under contract to Defence. Conflicts can be actual, potential or perceived.

2.16 In November 2014, in preparation for the 2015 bulk fuel tender, Defence sought contractor assistance in developing the Statements of Work for the 2015 bulk fuel tender. Defence received a single tender response from a consulting firm nominating a contractor for the position. The contractor had been employed a short time earlier as deed manager for a major supplier to Defence under previous fuel supply contracts, having until September 2014 worked in the area.

2.17 Defence required all personnel working on the tender evaluation to complete a Conflict of Interest Declaration, although there was no requirement to complete a declaration for pre-tender work.13 Seven personnel declared a potential conflict of interest, including the contractor, who appropriately declared previous employment with a supplier.

2.18 At Defence the contractor assisted with a number of specific technical roles, including at the pre-tender stage (December 2014–July 2015), reviewing the Statements of Work and making recommendations on pricing formulae. Post tender, the contractor had significant roles in evaluating value-for-money outcomes for Defence as the chair of the Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group and as a member of the Tender Evaluation Board. In these roles, the contractor, as a member of the Tender Evaluation Board, signed off on the Initial Screening Report, the Comparative Assessment Report, the Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group evaluation, and the Source Evaluation Report, all of which included evaluations of the tender submitted by the company in which the contractor had previously been employed.

2.19 Defence provided the independent probity advisor with only six of the seven declared conflict of interest forms. There is no evidence that Defence provided the contractor's form to the probity advisor, or raised the contractor's declared potential conflict of interest with the probity advisor at any point. Consequently, Defence officials did not receive any advice on this particular declaration as a basis for developing an appropriate management strategy.14

The probity implications of Defence's Fuel Network Review for the tender process

2.20 The probity plan requires that all tenderers are to be treated fairly and equitably. A probity issue arose during the tender evaluation period and when meetings of Defence's Fuel Network Review took place concurrently with the fuel procurement evaluation process.15 The objectives of the Fuel Network Review were to identify enterprise risk and network resilience, reduce costs and explore greater collaboration with industry. The Fuel Network Review process involved consultation with selected industry stakeholders.

2.21 Two participants in Fuel Network Review meetings were also tenderers being evaluated for the supply of fuels to Defence. This was recognised as a potential probity issue, with both the fuel procurement Tender Evaluation Team and the Fuel Network Review team seeking probity advice on the matter. The probity advice, which was shared between the two teams, included strategies to ensure that the integrity of the tender process was not compromised and stated that 'for reasons of accountability, Defence needs to ensure that these probity issues have been identified and addressed, and that a record is made showing that this was done'.

2.22 Defence did not provide any written advice to participants regarding the necessity not to discuss the fuels tender at future Fuels Network Review meetings. Defence has advised that one further Fuel Network Review meeting took place on 3 November 2015, but no record of this meeting appears in the probity or communications registers.

Security of tender information

2.23 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules 2014 provided that:

7.20 When conducting a procurement … entities should take appropriate steps to protect the Commonwealth's confidential information; and

7.21 [Suppliers'] submissions must be treated as confidential before and after the award of a contract.16

2.24 The Tender Evaluation Plan required all tendered material to be handled appropriately, to be kept secure and not to be used for personal gain or to prejudice fair competition. The evaluation working groups and their advisers were responsible for ensuring the physical security and confidentiality of all information relating to evaluation.

2.25 The Tender Evaluation Plan stated that all tender material was to be downloaded and receipted from AusTender and then transferred to Objective, Defence's secure electronic records system. From this point on, tender information was to be classified 'For Official Use Only' and kept secure. The Tender Evaluation Plan further required the Tender Evaluation Team Chair to approve the removal of any documents from the evaluation location or the accessing of tender documents electronically at remote locations.17

2.26 Defence records indicate that tender information was removed from Defence's secure system. Defence has not been able to provide evidence that the removal of the information was approved in accordance with Defence requirements. In the course of the audit the ANAO advised Defence of this issue and it is currently being reviewed by Defence.

Risk management

2.27 There were several frameworks in place to assist Defence to manage risk in procurement activity at the time of the fuel procurement. These included:

- the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013;

- the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy 2014;

- the Commonwealth Procurement Rules 201418; and

- Defence's Project Risk Management Manual.

2.28 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA) establishes a framework for the identification and management of risk. In particular, s16 of the PGPA Act provides that accountable authorities of all Commonwealth entities must establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight, management and internal control for the entity. Risk management is expected to be embedded as part of the culture of an entity.

2.29 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules 2014 require entities to establish processes for the identification, analysis, allocation and treatment of risk when conducting procurements. The Rules provide that the effort directed to risk assessment and management should be commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement. 19

2.30 Defence's Project Risk Management Manual was initially developed for the Defence Materiel Organisation (now the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group). Its purpose is to 'define robust and systematic risk management processes and provide defence personnel with advice and guidance on how to manage risk in projects'. The manual requires that all project risks be documented in a risk register and that staff are to update the risk assessment for a project at key decision points and milestones.

2.31 A risk register was established for the 2015 procurement. The risk register showed progressive refinement in the initial weeks in terms of the risks identified, their source and their degree of seriousness.20 Defence advised that the resources used to develop the initial risk register included the material liability risk template, the risk category and the risk impact categories as described in the Project Risk Management Manual, and risk registers from previous procurements.

2.32 Defence advised that Fuel Services Branch was obliged to operate in line with Defence and Commonwealth procurement policy, which included reference to the Defence Project Risk Management Manual for practical advice and guidance. The Project Risk Management Manual required Defence personnel to update the risk register at key decision points and milestones. There is no evidence that risks were reviewed after 30 June 2015 even though the Request for Tender did not close until 30 July 2015, after major milestones were achieved and when contracts were signed in 2015 and 2016.21

2.33 Defence advised that its approach in addressing risks was to 'appropriately [resolve] issues, as they arose, to ensure all tenderers had access to the same information and clarifications':

The risk register was used to plan the procurement strategy and processes. All issues that arose during tender release and evaluation stages were appropriately considered and Defence's management approach was to immediately action and resolve such issues by either:

- releasing RFT Addendums via AusTender to ensure all tenderers have access to the same information/clarifications from the Commonwealth; or

- identifying and addressing … issues for negotiation in the Source Evaluation Report and Deed Negotiation Directives.

2.34 Defence should have documented risks arising throughout the procurement and any mitigating treatments, which is useful to inform future procurements. However, Defence did not do this.

Records management

2.35 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules require entities to maintain documentation commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement, including records of relevant approvals and decisions. A key purpose of these record keeping requirements is to document how value for money is considered and achieved.22

2.36 Defence's Endorsement to Proceed and Tender Evaluation Plan required the maintenance of an audit trail. The Tender Evaluation Plan stated that:

To maintain an audit trail, records of the evaluation process will be kept and include reasons justifying decisions made by each [Tender Evaluation Working Group] as well as the [Tender Evaluation Board] in relation to each of the evaluation criteria assessed.

2.37 Defence prepared reports as required by the Tender Evaluation Plan. However, Defence was unable to locate various working files and meeting records for the purposes of this audit, including:

- working files of the conduct of the corporate assessments, or of the financial viability assessments undertaken for five suppliers, which underpinned analysis in the Financial Evaluation Report;

- records that specifically detailed how the estimated Deed values were calculated, or to provide a breakdown of the estimated Deed value by product type and contractors;

- minutes and working documents for meetings of the tender evaluation working groups or tender evaluation steering group; and

- complete records of how it addressed possible risks brought to its attention by potential suppliers.

2.38 The absence of working files and meeting records meant there was an insufficient audit trail for review of all aspects of the tender process.

Recommendation no.1

2.39 That, for future procurements in Fuel Services Branch, Defence:

- explicitly considers the potential conflicts of interest that may arise when employing individuals and contractors with recent industry experience; and institutes controls to ensure that all such matters are fully managed and documented;

- reviews and updates procurement risk registers at a minimum at all key decision points and milestones, when risk events materialise and as new risks arise throughout a procurement; and

- strengthen risk and records management by ensuring that all personnel involved are aware that tenders and related documents cannot be removed from Defence's classified systems without express authority by senior management.

Entity response:

2.40 Defence accepts the recommendation to apply to future Fuel Services Branch complex procurements.

2.41 Defence will amend the standard operating procedures and policies within Fuel Services Branch as they relate to procurement to ensure all issues in this report are appropriately addressed.

Was the tender evaluation process fit for purpose?

The complexity of the procurement was significant, with detailed requirements for over 100 geographically dispersed sites, multiple fuel types and several service requirements.

Defence's design of the tender evaluation process was fit for the purpose of dealing with this complexity. The Tender Evaluation Plan provided for multiple assessment stages, specialist working groups and comprehensive criteria.

Defence implemented the evaluation process and stages as outlined in its Tender Evaluation Plan. It produced the documents required for each stage of the evaluation and weighted criteria in line with the advice provided to tenderers. However, the clarity and transparency of Defence's decision making was reduced by a lack of adequate records underpinning the outcomes as determined by the tender evaluation working groups.

2.42 To assess if the tender process was fit for purpose, the ANAO considered the following:

- the tender process and evaluation criteria; and

- the evaluation process.

The tender process and evaluation criteria

2.43 The Defence procurement process starts with an Endorsement to Proceed. This document was signed off on 3 June 2015 and formally progressed the procurement process to allow Defence to release the Request for Tender to the market for a potential procurement initially estimated at $1.5 billion over five years.23

2.44 Defence's Request for Tender comprised:

- the overarching Request for Tender document;

- Statements of Work for the three components to be procured (bulk fuels; petroleum, oils and lubricants; and fuel card services)24; and

- detailed tender data requirements.

2.45 Tenderers were invited to submit a response against an individual statement of work, all statements of work or any combination of the three statements of work. The statements of work were detailed and specified the products and services to be delivered, product specifications, delivery locations, relevant standards and applicable timeframes.

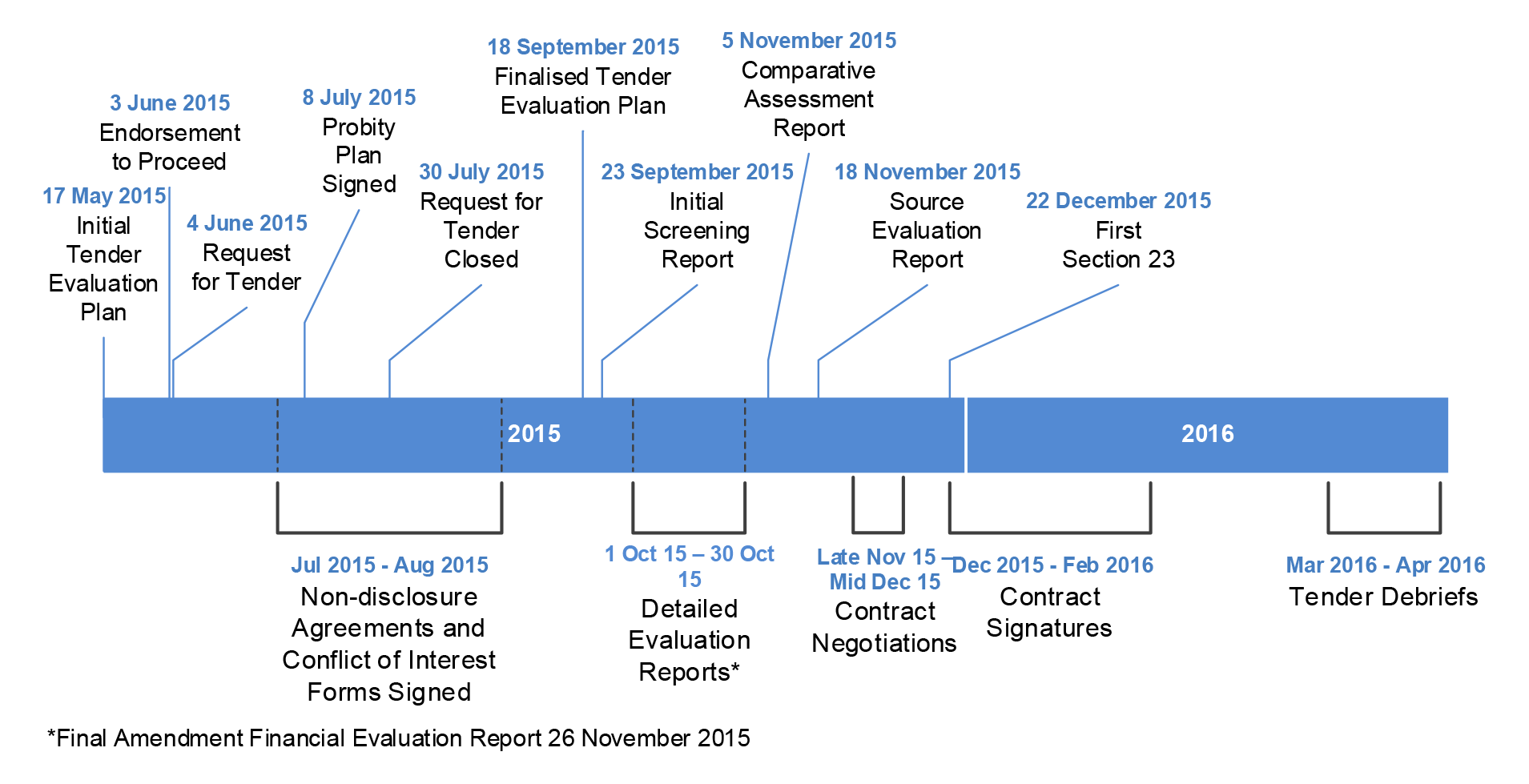

2.46 Potential suppliers were given eight weeks to submit tenders (from 4 June to 30 July 2015) and tender evaluation was conducted between 31 July 2015 and 11 November 2015, when the Source Evaluation Report was signed off by the Tender Evaluation Board. Contracts were signed progressively from December 2015 to February 2016.25 Figure 2.2 illustrates key processes and timeframes.

Figure 2.2: Timeline of bulk fuel tender (May 2015─April 2016)

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

The tender evaluation process

2.47 The size, scale and scope of the procurement resulted in a complex tender evaluation process. There were detailed tender requirements for over 100 sites and three different statements of work to assess (for bulk fuels; packaged petroleum, oil and lubricants; and card services). The assessment process used both weighted and unweighted criteria, resulting in a range of factors having to be considered to arrive at final judgements about each supplier.

2.48 As noted at paragraph 2.6 Defence was seeking an outcome that would provide surety of supply: at all locations; within and across the greatest number of delivery methods; the maximum range of supplies; and with a minimum number of contractors.

2.49 The Tender Evaluation Plan outlined that a value for money assessment was to be produced that had regard to:

- the degree to which the tender met technical, compliance and commercial requirements;

- an assessment of each tender against its offered pricing proposal; and

- an assessment of the risks and opportunities identified with each tender.

2.50 The six stages of the evaluation process and the outcomes are shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Tender evaluation stages

|

Stage |

Reports and Outcomes |

|

Stage 1: Initial Screening |

Eight of the ten tenders met the Tender Evaluation Plan's mandatory compliance requirements. These eight tenders were:

|

|

Stage 2: Shortlisting

|

Initial Screening and Shortlisting Report (23 September 2015) Shortlisting was not conducted given the completeness of compliant tender submissions. |

|

Stage 3A: Detailed Evaluation against Technical and Operational, Commercial and Compliance Requirements

|

Technical and Operations Tender Evaluation Working Group Detailed Evaluation Report (30 October 2015) Commercial and Compliance Tender Evaluation Working Group Detailed Evaluation Report (23 October 2015) These reports included: an analysis of each tenderer's performance against evaluation criteria in the form of a score for each criteria; and a qualitative statement that addressed key strengths and weaknesses of each tender and for compliance and risk. |

|

Stage 3B: Detailed Evaluation against Financial Requirements

|

Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group Detailed Evaluation Report (final amendment 26 November 2015) The report included: financial viability of tenderers; compliance with pricing and payment terms; early payment and national discounts; and an analysis of bids—lowest cost solutions and modelling of alternative scenarios. |

|

Stage 4: Comparative Assessment, and identification of risks and opportunities

|

Comparative Assessment Report (5 November 2015) Value for money assessment and an overall ranking of the tenders. |

|

Stage 5: Source Evaluation Report

|

Source Evaluation Report (18 November 2015) The SER serves to record the detailed evaluation results, provide the source from which issues for contract negotiation will be drawn, and to provide an audit trail for the detailed assessments made in arriving at the source selection recommendation. |

|

Stage 6: Negotiations, tender notification and debriefing

|

Negotiation Reports Shell Aviation (17 December 2015) Viva Energy (17 December 2015) Caltex (17 December 2015) AS Harrison (18 December 2015) Interchem (22 December 2015) World Fuel Services (22 December 2015) BP (11 February 2016) Contract Negotiation Reports are prepared after contract negotiations are concluded and detail the outcomes of contract negotiations with the authorised representatives of the successful tenderers. The reports contain a summary of negotiation outcomes for areas such as deed management, pricing and supply chain resilience issues. Defence offered and conducted tender debriefings in 2016. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

Initial screening and shortlisting

2.51 As required under the tender evaluation plan, initial screening by the Tender Evaluation Board was undertaken to check tenders against minimum content and format requirements, conditions for participation, and essential requirements (conditions of tender 5.5, 5.6 and 5.7 respectively). Ten tenders were received and two were assessed as not meeting one or more of the requirements listed above. The initial Screening and Shortlisting report was produced by the Tender Evaluation Team Chair on 23 September 2015. The report concluded that there was little to be gained in conducting shortlisting, due to the completeness of the tender submissions which passed initial screening. Eight tenders proceeded to the working group evaluation stage.

Detailed evaluation by working groups

2.52 The tender evaluation working groups (described in Figure 2.1) were responsible for the detailed evaluation against specific criteria and reporting to the Tender Evaluation Board. Tenders were to be assessed against evaluation criteria released to the market as set out below (Box 1).26

|

Box 1: Published tender evaluation criteria |

|

Clause 6.1.1 of the conditions of tender stated:

|

2.53 The allocation of responsibilities to each working group was as follows:

- the Commercial and Compliance Working Group assessed tenders against criteria (a), (d) and (g);

- the Technical and Operations Working Group assessed tenders against criteria (b), (c) and (h); and

- the Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group assessed tenders against criteria (e) and (f).

2.54 The Tender Evaluation Plan provided for financial submissions to be separated out from the matters to be considered by the commercial and compliance, and technical and operations working groups, so that these working groups 'did not have visibility of the pricing information and would not be influenced by pricing in their technical and commercial assessments'.27

2.55 The Commercial and Compliance Working Group's report ranked tenderers according to each of the three criteria in relation to the statement of work. The report comprises a narrative for each tenderer, summarising the key benefits, deficiencies and risks for that tenderer. The report also identifies issues for legal review for each tenderer.

2.56 One of the criteria for evaluation by the commercial and compliance working group related to past performance. The working group assessed claimed past performance of tenders based on information provided by companies in their tender submissions. Defence advised the ANAO that:

To ensure equitable treatment of all tenderers, not just previous suppliers to Defence and to ensure that there were no undue benefits of incumbency, Defence evaluated tenderers based on the merits of each submission, and conducted assessments of the commercial, technical and operational impact and risk of the individual offers. This assessment included the review of past performance information presented by tenderers in their submission.

2.57 There is no evidence in the report of the Commercial and Compliance Working Group that incumbent companies' claims were tested for validity using relevant performance information—that should have been available in Defence's own systems—to inform the assessment of tenderers' past performance.

2.58 The Technical and Operations Working Group reviewed submissions against the statements of work, using an assessment tool developed for the purpose. The report provides a narrative assessment on each tenderer and a scorecard showing a risk rating, numerical score and qualitative rating against each of the criteria (b), (c) and (h) and their subsets for that tenderer. The report also contains detailed spreadsheets listing each individual item for supply and the relevant information on that item by tenderer.

2.59 The Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group produced an analysis of each tenderer's performance for the two financial criteria in the form of a qualitative statement that addressed the key strengths and weaknesses of each tender and the compliance and risk assessments, as required under the Tender Evaluation Plan. The Detailed Finance Evaluation Report provided a summary of the working group's findings, value for money recommendations and a comparison of suppliers across product offerings. It also included:

- tables showing the lowest priced option by product within each Statement of Work; and

- information on comparative savings on a like-for-like basis.

2.60 Defence advised the ANAO that, in relation to the Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group's responsibilities under the Tender Evaluation Plan, the working group did not rank the tenders, but reached 'a common price identification for comparison which was achieved by identifying the lowest priced bids for each location by product type and delivery method' for consideration in the comparative assessment.

2.61 Defence further advised that at the comparative assessment stage, the Finance Tender Evaluation Working Group modelled various supply chain outcomes at the request of the Tender Evaluation Board Chair to inform the final rankings as detailed in the Source Evaluation Report.28 Defence advised:

This was required to inform the final rankings as detailed in the [Source Evaluation Report]. The overall VFM assessment identified the optimal composition of the resultant Deeds consistent with the procurement principles of providing strategic value and benefit to the Commonwealth. Defence does not have a written record of this direction.

2.62 Modelling was undertaken but Defence was unable to locate records of the modelling which underpinned the rankings produced in the annexes to the Comparative Assessment Report. In addition, terminology was inconsistent throughout the report as was the presentation of the analysis of the bids.

2.63 The Tender Evaluation Plan required working groups to produce reports for consideration by the Tender Evaluation Board. Each of the working groups produced their report by early October 2015.

The comparative assessment

2.64 The comparative assessment was stage four of the evaluation process. The Tender Evaluation Plan provided that evaluation team members could conduct 'any comparative analysis and risk assessments as necessary' and set out a detailed process for this assessment and determination of value for money. The results of the comparative assessment were documented in the Comparative Assessment Report. The report provided an understanding of how the Board synthesised the ratings and assessments in the working group reports into final recommendations.

2.65 The Tender Evaluation Board was required to undertake a comparative assessment process, as follows:

(a) determine a preliminary ranking of tenders for each of the three statement of work service product categories, based on the combined assessment outcome across the tender evaluation criteria …;

(b) this preliminary ranking to be used to determine potential outcomes for each of the Statement of Work (by Annex) service product categories that will provide the required totality of the requirements coverage across all locations and/or all products within the individual Statement of Work [SOW] service product category and then consider tenderers ranked second, third etc sequentially until the totality of the Commonwealth's requirements are met for that SOW service product category …; and

(c) having determined an outcome of one or more preferred tenderers for each statement of work and the optimal allocation of required locations and/or products to each tenderer, the TEB will then consider opportunities provided by any preferred tenderer that offers the potential for integration of services across more than one statement of work, or across all three statements of work, and where that multi-SOW solution may be assessed as resulting in enhanced value for money in the delivery of requirements across locations and/or products…

2.66 The following inputs were also considered in the development of the comparative assessment:

- a risk assessment, which included consideration of the tenderers' financial and corporate capacity;

- advice of Tender Evaluation Steering Group Chair, the Legal Advisor and the Fuels Services Branch Senior Desk Engineer.

2.67 To arrive at a value for money comparative assessment the Tender Evaluation Board was required to make comparative assessments using both weighted and unweighted criteria. The Board also needed to synthesise qualitative and quantitative assessments from the individual working group reports before developing its recommendations to the Delegate.

2.68 The Comparative Assessment Report was signed off on 5 November 2015 by the Tender Evaluation Board, comprising the Tender Evaluation Team Chair and the leaders of the working groups. The report set out the value for money assessment, having regard to:

- the degree to which the Tender meets the Technical, Compliance and Commercial Requirements;

- an assessment of each Tender against its offered pricing proposal; and

- an assessment of the risks and opportunities identified with each Tender.

2.69 The report also set out its methodology for arriving at a value for money conclusion and further noted that 'the overall [value for money] ranking for each statement of work is as per the recommendations for each statement of work'.

2.70 The Comparative Assessment Report is a comprehensive document, which reflects the requirements for the comparative assessment set out in the tender evaluation plan. It contains detailed explanations of the methodology for arriving at its recommendations. The report usefully details matters to be raised in the course of negotiations and some recommendations are predicated on negotiated modifications to tenderer contractual requirements.

The source evaluation report

2.71 The Source Evaluation Report was dated 11 November 2015 and signed off by the Delegate on 18 November 2015. The Source Evaluation Report relies heavily on the Comparative Assessment Report. The report summary affirms the value for money approach as adopted by the Board in the comparative assessment—the 'optimal composition of deeds consistent with the procurement principles of providing strategic value and benefit to the Commonwealth'—and includes a ranked table of preferred tenderers for each Statement of Work. The Source Evaluation Report identified potential savings of $10.69 million per annum, representing a 3.2 per cent per annum saving on the existing deed arrangements.

2.72 Defence followed the tender evaluation process and stages as outlined in its Tender Evaluation Plan, producing the required reports. The Comparative Assessment Report contained assessments, final ranking of tenderers for each Statement of Work and recommendations for the award of the tenders. It also included issues to be addressed in negotiations for each of the successful tenders. However, the methodology for determining value for money for the Commonwealth was complex and difficult to follow.

2.73 In its advice to the ANAO, Defence expressed confidence that its tender process was designed to create a level playing field, reduce the benefits of incumbency and maintain competitive pressure:

Defence evaluated tenderers based on the merits of their submission and an assessment conducted by discrete TEWGs of the commercial, technical and operational impact and risk of the offers presented by tenderers.

All Defence approaches to the market were conducted via AusTender. Competitive pressures were achieved through the open market tender approach to industry, and the use of a minimal number of RFT essential requirements. The outcome of the procurement demonstrates that a competitive environment was achieved in that:

- [there was an] award of a Deed to World Fuel Services for aviation fuel supply at civilian airports, a company that has not previously held a Deed with Defence;

- Viva Energy became majority supplier of marine fuel (previously BP); and

- BP became a supplier of land fuel supply (previous supplier was Caltex only).

The finance evaluation report

2.74 The finance evaluation report was signed off on 2 October 2015 by the two team members. The report set out the assessment of the tenders against the two financial criteria, by 'lowest cost option' and alternative scenarios for each product. The report made value for money recommendations for each statement of work category based on the financial assessment. It also contained a table which estimated approximate whole of life contract values for the preferred tenders.

2.75 Defence advised that, subsequent to the 2 October 2015 report, Fuel Services Branch had requested revised financial assessment costing calculations at the time of the Source Evaluation Report development to ensure consistency in the comparative analysis. The request arose from concerns which had been raised about the working group's financial modelling scenarios used to produce like-for-like comparisons in the assessment tables in the October financial evaluation report.

2.76 Revised financial assessment costing calculations were provided to the Board via email and used in the development of the Source Evaluation Report prior to the Source Evaluation Report being signed off on 11 November 2015.

Tender results

2.77 The outcome of the tender was the award of up to $1.9 billion in contracts over five years from 2016─2021.29 Caltex, the major supplier under the previous contract, was allocated about 46 per cent of this work, worth up to $867.4 million.30 BP was initially the preferred tenderer for a number of land fuel sites, but withdrew its offer after inspecting a number of sites, with the result that Caltex, as the second preferred tenderer, picked up those sites. All seven companies which passed initial screening were successful in securing Defence contracts, as set out in Table 1.1.31 Financial commitment approvals were signed in December 201532 and Defence signed contracts between December 2015 and February 2016 thereby ensuring the continuation of fuel supplies.

Did Defence achieve value for money from the procurement?

The 2015 fuels tender and evaluation process was designed to produce a value for money outcome. Defence undertook an open tender process, conducted detailed evaluation of tenders, considered price and non-price value, and applied an industry standard fuel pricing methodology.

Defence's failure to negotiate to attempt to achieve lower prices for some components of the fuel pricing formula before supply contracts were signed compromised its ability to demonstrate that value for money was maximised for the Commonwealth.

Formula based pricing and price negotiation

2.78 A key objective of Defence's tender process was to achieve value for money through the use of industry standard pricing formulae as had been used in the 2010 tender and which had delivered 'significant savings'.33 The formulae were developed prior to the 2010 tender, when Defence sought external advice from the Portland Group34 on the applicability of its fuel pricing arrangements, to test the suitability of its then pricing formulae and its competitiveness against industry standards.

2.79 The Portland Group Report found that:

- the then ADF formula for petroleum products was largely inconsistent with standard industry practices for large commercial customers, where a significantly increased level of product transparency was the norm; and

- the components and the strengths and weaknesses of the various formulae were not well understood by [Defence's Joint Fuels and Lubricants Agency], including their impact on Defence's costs and the potential risks inherent in the formulae.

2.80 Another factor of significance was the volatility of the market and the Portland Report noted that 'for large consumers with transparent pricing formulas…this risk is visible, and can be managed or mitigated'. Defence is considered to be a large consumer and the report therefore advised that it was essential that Defence understood the discrete cost components that reflected the reality of product supply.

2.81 The report further noted that 80 to 90 per cent of the total cost of the delivered product was attributable to product benchmark and taxes and hence not negotiable. Therefore, Defence's ability to negotiate prices would be dependent on its ability to separate out the 10 other factors listed in the report and negotiate on these individual elements of the pricing profile. The Portland Report reveals that of these 10 pricing elements, two (local freight, and storage and handling), had the greatest capacity for negotiation, five elements had some capacity and three had no capacity for negotiation because suppliers were not likely to surrender relevant information.

2.82 Defence amended its pricing methodology for the 2010 procurement in line with the Portland Group's advice by amending its pricing formula to incorporate the separate elements of the product supply chain. Defence retained this methodology for the 2015 procurement. The Wraith Review in 201335 noted that the Defence procurement methodology and pricing formulae was 'sophisticated to the extent that better than Terminal Gate Pricing has been achieved to date'.

2.83 Prior to going to tender in 2015, Fuel Services Branch stated in its Endorsement to Proceed that the pricing arrangement used for the 2011–2015 fuel contracts was 'industry standard' and incorporated a 'traceable and flexible' approach to current world-wide fuel prices. This conclusion was reached following the Wraith review and Defence retained the pricing arrangement for the new tender process.

2.84 Defence advised the ANAO that its current pricing methodology is in line with industry standards for wholesale fuel procurement and takes into account market factors. Defence further advised that:

Subsequent to [the Portland Group] report, the price methodology applied in the Deeds awarded in 2010 mirrored the [Import Parity Pricing] methodology, a methodology used by large commercial customers that covers costs of all elements in the supply chain to import fuels into Australia…For the 2015 procurement, Defence also used the [Import Parity Pricing] methodology in price adjustment formula and engaged a consultant with extensive industry experience to verify that the methodology was relevant and in line with industry standard.

2.85 The Defence Procurement Policy Manual applicable at the time of the 2015 procurement states that a decision to negotiate might be influenced by the prospect of an improved value for money outcome and that because the price of supplies is a potential area for negotiation, it should form part of the negotiation plan. However, Defence advised the ANAO that because the pricing methodology [specified by Defence in the Request for Tender] 'dictated that price negotiation was not an element of achieving improved value for money', price was not included in the negotiation strategy.36 In its advice to the ANAO, Defence did not expand on why the pricing methodology determined that price was not a matter for negotiation.

2.86 The Defence Procurement Policy Manual also states that circumstances where price negotiation may be appropriate include where the contract is to provide for cost plus or incentive pricing. Defence did not have a strategy to negotiate certain cost components and subsequently did not seek to negotiate a reduction in tendered prices at the negotiation phase.

2.87 Defence was seeking to purchase high quantities of fuel and is a regular and reliable customer, consuming approximately one per cent of Australia's total fuel and spending over $400 million per year. The tender process provided Defence with up-to-date comparative information, potentially valuable to negotiating lower prices. Due to the volumes consumed, even relatively small price savings achieved through negotiation could have delivered overall savings to the Commonwealth.

Average pricing methodology

2.88 Defence uses an averaging pricing arrangement to flatten the amount of variability in the underlying price, which fluctuates daily on global markets. Defence might benefit from modelling the outcomes from the averaging pricing arrangement against the actual prices over time to identify whether the averaging arrangement is to its financial advantage and whether it should be retained.

Recommendation no.2

2.89 That, for future procurements within the Fuels Services Branch, Defence conducts an independent evaluation of the 2015 fuel procurement process, strategy and arrangements to inform the next procurement process and maximise a value for money outcome.

Entity response:

2.90 Defence accepts the recommendation to apply to the next open market procurement process for bulk fuels, oils, lubricants and fuel card services.

2.91 Defence will engage a fuel industry specialist to conduct the independent evaluation.

3. Managing the fuel contracts

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether Defence's contracting and assurance arrangements were appropriate for effectively managing the fuel supply chain.

Conclusion

Defence's contract management would benefit from improved integration of key information systems and reduced manual intervention, including in the calculation of fuel prices.

Defence's ability to provide assurance over the management of its fuel supply chain is limited by infrastructure and information technology deficiencies and insufficient central data analysis. Defence is currently implementing some short term initiatives to improve central oversight, however significant systems level improvement regarding assurance controls is not scheduled to commence until 2022.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at improving the management of Defence's bulk fuel contracts, with a focus on strengthening assurance arrangements over the fuel inventory.

3.1 This chapter considers Defence's management of contractual arrangements via deeds of standing offer with its fuel suppliers. The deeds set out the details for determining prices, delivery, payment, performance monitoring and quality. The effectiveness with which Defence manages the deeds and the arrangements with suppliers will impact on the quality of service and the value for money achieved under the contracts.

3.2 Procurement Rules require entities to establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight and internal management. Risk is considered with specific reference to the management of fuel volume discrepancies at Defence fuel installations.

3.3 Defence is in the early stages of implementing its Fuels Transformation Program, a long term reform program to improve the operational efficiency of the fuels network. The program is a consolidated program of works to remediate enterprise risk and reduce the cost of the fuels program.

Are contract management arrangements effective in managing the fuel supply chain?

Defence's processes and controls over the calculation of fuel prices do not provide adequate assurance, with manual processes supplementing inadequate information technology systems. Defence's fuel management inventory system is still not fully integrated with Defence's financial management system.

Defence relies on a range of documents to guide contract management and oversight of each supplier's performance. Development of an internal procedural guidance document would assist staff and provide a source of corporate knowledge.

While Defence recognised that it required skills in the fuels services area not immediately available to it on the establishment of the Fuel Services Branch, it continues to rely heavily on contracted services at high cost.

Contract management

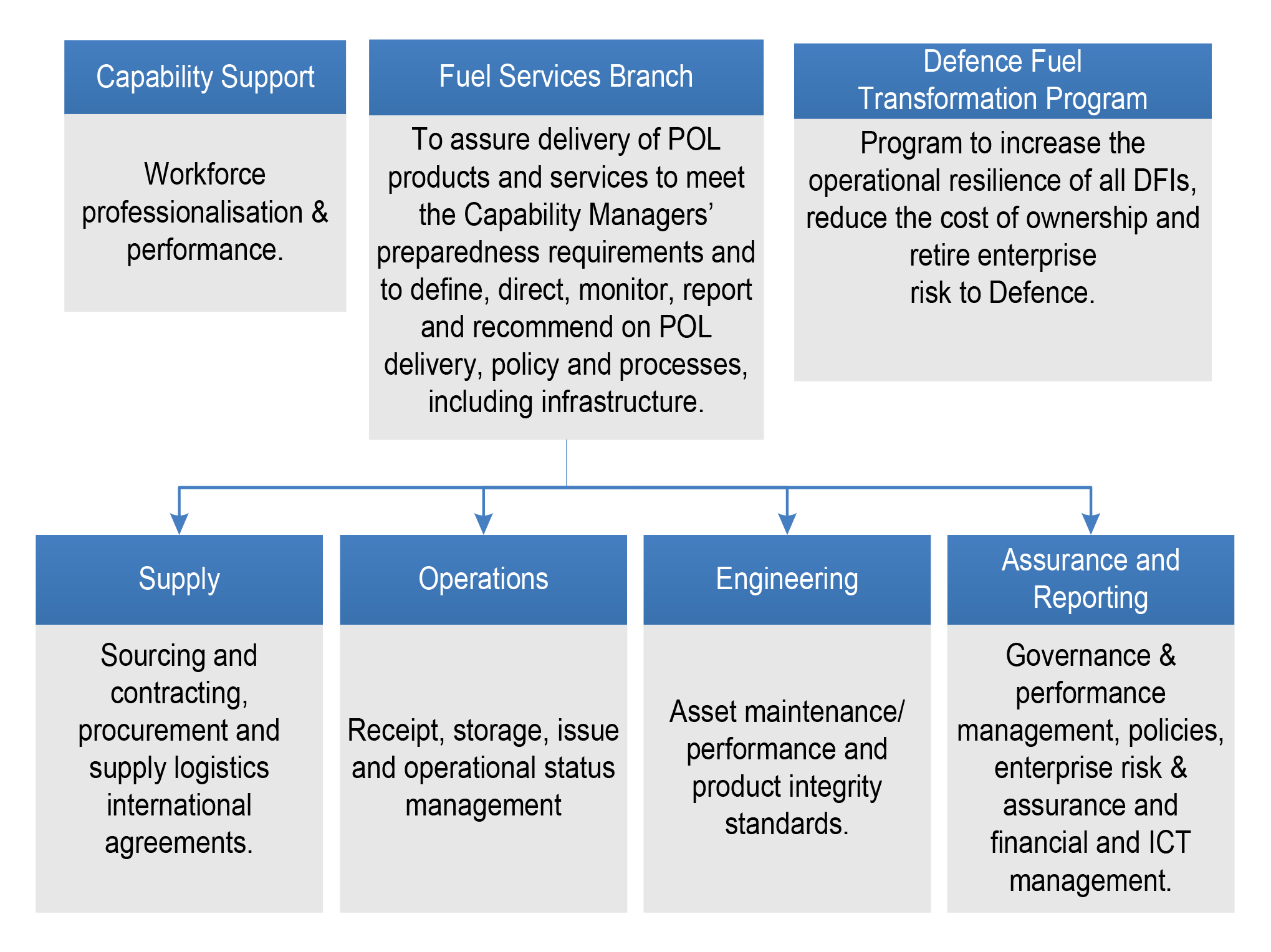

3.4 The Fuel Services Branch is responsible for managing the contractual arrangements and for monitoring and review of fuel prices and inventory management. The Fuel Services Branch structure and responsibilities are set out in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Summary of Fuel Services Branch roles and responsibilities

Source: Defence documents.

Deeds management

3.5 Arrangements for managing the deeds are set out in the individual deeds. The deeds require the contractor, among other things, to keep records and provide to Defence quarterly status reports, attend performance reviews and to develop a risk management register. Defence advised the ANAO that it 'maintains a schedule of key contract administration and governance activities'37 which are used for deed management purposes. The key documents include:

- the contract manager's master schedule, a register of deeds of standing offer showing dates, value of contract, expiry dates and any change proposals, the dollar value and effective dates;

- checklists and key performance indicators tracking spreadsheets for both fuels and POL products; and

- administrative arrangements within Fuel Services Branch.

3.6 While Defence tracks the Departmental and supplier activities undertaken in relation to the requirements under the deeds via spreadsheets and checklists, it has not yet developed an internal procedural guidance document within the Fuel Services Branch. Such a document would inform the administration of contracts in a systematic way and provide for the capture of corporate knowledge. Defence advised the ANAO that it is in the process of developing an internal procedural guidance document within the Fuel Services Branch.

Calculation and assurance over prices of fuel

3.7 A major part of the management of the contractual arrangements requires Defence to regularly calculate fuel prices using the fuel price formulae set out in the deeds of standing offer.38 Defence provides the results to suppliers for their confirmation, prior to formally agreeing the price to be paid for that supply period. The assurance over fuel prices is dependent on accurate manual data input and the confirmation from suppliers that prices are accurate.

Calculation of fuel prices

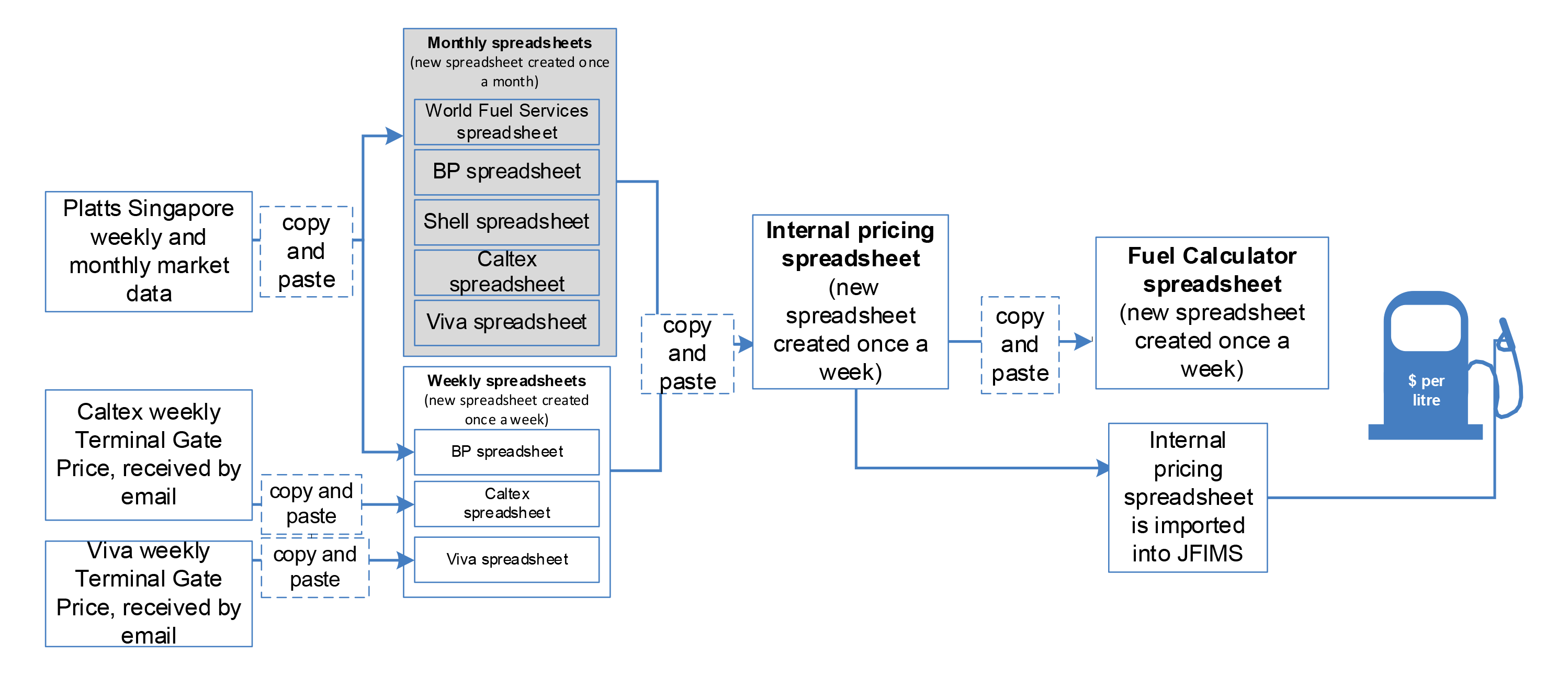

3.8 Under the standing offer arrangements, Defence establishes fuel prices according to the contractual formulae in the deeds, with each of its suppliers. The calculations are dependent on factors such as the supplier; the location; the fuel type; and the date. The majority of fuel pricing adjustments are calculated using the average base price of the particular fuel type (such as Platts39), for the preceding week or month. The fuel price calculations are obtained through a combination of automated systems and manual effort. A high-level diagram of Defence's process for calculating fuel prices is outlined in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Defence process for calculating fuel price per litre, per location

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

3.9 Defence manually calculates the weekly and monthly fuel prices for some 300 locations using spreadsheets, an exercise that is independent of the Joint Fuels Information Management System. The calculation process involves the creation of new spreadsheets each week and/or month, and multiple instances of manual copying and pasting before providing prices to the supplier for comment. Defence then produces the adjusted prices for review by suppliers. Defence has advised that 'the manual copying and pasting of information is intended to ensure commercially sensitive information is managed appropriately, to produce discrete supplier specific files and ensure that commercially sensitive information is disclosed only to personnel conducting price adjustments'. Defence further advised the ANAO that:

Contractors then validate the adjustments prepared by Defence using their own internal processes/systems; as such any inconsistency in pricing is identified and corrected promptly by both parties (Defence and contractors).

The Defence calculation process ensures a record of each and every price adjustment for each supplier is saved for record keeping and audit purposes.

3.10 In the period from the commencement of the contracts in February 2016 until March 2017, Defence created a total of 370 individual spreadsheets, comprising 3383 worksheets.40 Defence notes that 'the number of spreadsheets created is commensurate with the frequency of price adjustments, number of suppliers, the contracted price adjustment methodology for each supplier by fuel type, and the number of pricing components of the contracted pricing methodology'. A breakdown of the number of spreadsheets and worksheets created at each stage of Defence's process for calculating fuel prices is provided in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: The number of spreadsheets/worksheets created, Feb 2016–March 2017

|

Spreadsheet name |

Number of spreadsheets |

Number of worksheets |

|

Monthly and Weekly |

230 |

2760 |

|

Internal Pricing |

69 |

552 |

|

Fuel Calculator |

71 |

71 |

|

Total |

370 |

3383 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

3.11 Consultation with suppliers enables Defence and the fuel supplier to verify the agreed standing offer price to be used for the next supply period in order to avoid significant issues on pricing and invoicing after fuel is supplied.

3.12 Defence maintains that its fuel price calculation arrangements provide adequate assurance. Defence advised the ANAO that:

The internal Defence documents used to adjust fuel prices were developed in close consultation with each Supplier and to ensure transparency, they are shared with each Supplier immediately following any price adjustment. Suppliers are required to validate the adjusted prices against their own internal processes and will promptly advise when there is discrepancy between the two parties' calculations.

3.13 The current process for calculating fuel prices, particularly the manual creation of thousands of spreadsheets per annum, increases the potential for input error. Defence advises that there is a process for verifying the prices loaded into the fuels management system:

Defence does audit the upload of prices into FuelsManager.41 Since Deed commencement, fuel prices uploaded into FuelsManager have been verified by FSB staff by validating the prices uploaded in JFIMS against the prices contained in the upload file. This process was conducted in working files however individual records were not saved. Since mid Sep 17, FSB have updated this process following development of a Microsoft Excel spread sheet which automates the reconciliation of prices imported into FuelsManager…Check files are now saved as corporate records.42

3.14 Defence also advised the ANAO that: all Defence supplier invoices are reconciled to fuel receipts; that there is annual testing of Fuel Services Branch procurement activity under its business process testing controls framework, which includes random sampling of invoice payments; and that Defence Finance conducts random sampling of payment transactions on an ad hoc basis.

3.15 Although the ANAO found no evidence of inappropriate fuel price advice from suppliers, Defence's primary quality assurance mechanism of relying on suppliers to detect and advise on pricing calculation errors exposes Defence to some risk.43 A more thorough evaluation process over fuel price calculations could provide Defence with a higher level of assurance around the integrity and accuracy of its data and its price determination processes.

Information systems: JFIMS and Roman

3.16 Defence uses two primary information systems to support the management of the fuel inventory and the calculation of fuel prices:

- Joint Fuels Information Management System (JFIMS), which manages demand (volume) and contains some purchase information;

- Resource and Output Management Accounting Network (ROMAN) is the whole-of-Defence financial management system, and includes budgeting, accounting and reporting.

3.17 The relationship between JFIMS, the fuel inventory management system, and ROMAN, the financial management system, is fundamental to assurance of price paid and inventory management. The linkage between the two datasets is important to ensure that the invoiced price and paid price is the same as the fuel price list loaded in JFIMS. Payment is then made in the ROMAN system. However, when data was requested to enable the ANAO to analyse end to end transactions, Defence was not able to provide the linkage required to join JFIMS and ROMAN tables.