Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Management of ICT Systems Security Authorisations

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Malicious cyber activity represents a key risk for the Department of Defence (Defence).

- Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) Policy 11 outlines how ICT systems can be protected through authorisation activities to support the delivery of government business.

- This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s arrangements for the management of its ICT systems authorisations.

Key facts

- The Defence Security Principles Framework (DSPF) requires that ‘all Defence ICT systems must be authorised prior to processing, storing or communicating official information’.

- The DSPF provides for system authorisation decisions to be escalated to more senior personnel based on the system’s assessed residual risk level.

What did we find?

- Defence's arrangements to manage the security authorisation of its ICT systems have been partly effective.

- Defence’s arrangements for system authorisation have not been regularly reviewed and do not reflect current PSPF requirements.

- Defence’s reporting did not comply with DSPF requirements, omitted key system authorisation data, and indicated a more optimistic outlook than was reflected in other Defence documentation.

- Defence did not comply with the PSPF and DSPF system authorisation requirements for the five case studies examined in the audit.

What did we recommend?

- There were eight recommendations to Defence aimed at improving: the review and update of assessment arrangements; training; the quality of supporting information; assurance and reporting arrangements; and compliance with authorisation requirements.

- Defence agreed to the eight recommendations.

285 days

was the average time to process system authorisations from September 2020 to September 2021.

5%

of Defence’s ICT systems have been registered in Defence’s ICT authorisation management system as at June 2024.

47%

of those ICT systems registered have been recorded as ‘Expired’ or ‘No accreditation’ as at August 2024.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The security of government information and communications technology (ICT) systems, networks and data supports Australia’s social, economic and national security interests as well as the privacy of its citizens. Malicious cyber activity has been identified as a significant threat affecting Australians, exacerbated by low levels of cyber maturity across many Australian Government entities.1

2. The Department of Defence’s (Defence’s) mission and purpose is to defend Australia and its national interests in order to advance Australia’s security and prosperity. Defence’s 2022 Cyber Security Strategy states that ‘Malicious cyber activity now represents one of Defence’s most critical risks.’2

3. The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) was introduced in 2010 to help Australian Government entities protect their people, information and assets, both at home and overseas. The PSPF sets out the government’s protective security policy approach and is comprised of 16 core policies.3 PSPF Policy 11 Robust ICT systems requires that:

Entities must [emphasis in original] only process, store or communicate information and data on an ICT system that the determining authority (or their delegate) has authorised to operate based on the acceptance of the residual security risks associated with its operation.4

When establishing new ICT systems, or implementing improvements to an existing system, the decision to authorise (or reauthorise) a system to operate must [emphasis in original] be based on the Information Security Manual’s [ISM] six step risk-based approach for cyber security.5

4. Defence has established the Defence Security Principles Framework (DSPF) to support compliance with the requirements of the PSPF. The DSPF outlines Defence’s requirements for ICT assessment and authorisation including that ‘all Defence ICT systems must be authorised prior to processing, storing or communicating official information’.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. Through its 2022 Cyber Security Strategy, Defence has recognised that ‘Malicious cyber activity now represents one of Defence’s most critical risks.’ Robust ICT systems protect the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the information and data that entities process, store and communicate. PSPF Policy 11 outlines how entities can safeguard ICT systems through assessment and authorisation activities to support the secure and continuous delivery of government business.

6. Questions regarding Defence’s system authorisation process were raised at hearings of the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee in June 2021, including in relation to:

- Defence’s use of provisional authorisations beyond 12 months for systems where security concerns have not been sufficiently addressed;

- deficiencies in Defence’s processes for identifying and assessing risks as part of the authorisation process; and

- DSPF compliance with the Information Security Manual (ISM).

7. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s arrangements for the management of ICT systems security authorisations.6

Audit objective and criteria

8. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s arrangements to manage the security authorisation of its ICT systems.

9. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Does Defence have fit-for-purpose arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems?

- Has Defence implemented its arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems?

Engagement with the Australian Signals Directorate

10. Independent timely reporting on the implementation of the cyber security policy framework supports public accountability by providing an evidence base for the Parliament to hold the executive government and individual entities to account. Previous ANAO reports on cyber security have drawn to the attention of Parliament and relevant entities the need for change in entity implementation of mandatory cyber security requirements, at both the individual entity and framework levels.

11. In preparing audit reports to the Parliament on cyber security in Australian Government entities, the interests of accountability and transparency must be balanced with the need to manage cyber security risks. The Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) has advised the ANAO that adversaries use publicly available information about cyber vulnerabilities to more effectively target their malicious activities.

12. The extent to which this report details the cyber security vulnerabilities of Defence was a matter of careful consideration during the course of this audit. To assist in appropriately balancing the interests of accountability and potential risk exposure through transparent audit reporting, the ANAO engaged with ASD to better understand the evolving nature and extent of risk exposure that may arise through the disclosure of technical information in the audit report. This report focusses on matters material to the audit findings against the objective and criteria.

Conclusion

13. Defence’s arrangements to manage the security authorisation of its ICT systems have been partly effective. Systems have not been authorised in a timely manner and were assessed through processes that did not consistently comply with Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) requirements.

14. Defence’s arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems are partly fit for purpose. Defence’s policies, frameworks and processes to support system assessment and authorisation have not been regularly reviewed or updated to align with PSPF and Defence Security Principles Framework (DSPF) requirements. These policy and process documents are internally inconsistent. Defence has not established training to ensure that key personnel involved in the authorisation process remain up-to-date with changing cyber security requirements in the Information Security Manual (ISM) and PSPF.

15. Defence has partly implemented arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems. Defence’s data on its system assessments and authorisations is incomplete and indicates that System Owner obligations to obtain and maintain authorisation of their systems are not being fulfilled.

16. There were deficiencies in relation to Defence’s monitoring and reporting arrangements, including non-compliance with DSPF reporting requirements. Key information on the system authorisation status of Defence’s systems was omitted from Defence’s reporting, including not addressing a request from the Minister for Defence to include metrics in reporting on unapproved ICT systems within Defence. Defence’s internal and external reporting on its assessments indicated a more optimistic outlook than was otherwise reflected in other internal Defence documentation. Across the ICT systems examined in case studies, deficiencies included: the absence of key data and mandatory security documentation; no evidence of assessment of control implementation; and deficiencies in the peer review process.

Supporting findings

Defence’s arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems

17. Defence has not appropriately maintained its policy and governance framework for the authorisation of its ICT systems. When the DSPF was implemented in July 2018, some sections were not complete, with key authorisation roles listed but not defined for 13 of the 14 Defence Services and Groups listed. These roles remained undefined until a May 2024 review of the DSPF. Prior to the May 2024 update, DSPF Principle 23 and DSPF Control 23.1 had not been updated since July 2020. This meant that key changes to the mandatory requirements in PSPF Policies 10 and 11 between August 2020 and February 2022 — such as the introduction of the ‘Essential Eight’ and the ISM six-step process for system assessment and authorisation — were not reflected in the DSPF until 10 May 2024. (See paragraphs 2.3–2.25)

18. Directives, instructions, and policies issued by the Australian Defence Force (ADF) services for ICT authorisations for Army, Navy and Air Force systems contain provisions that are either not consistent with or not permitted by the requirements of the DSPF, or PSPF Policy 11. These provisions have allowed for exemptions to Defence’s system authorisation process that are not permitted under the DSPF or PSPF. (See paragraphs 2.26–2.38)

19. A key supporting framework, the Defence ICT Certification and Accreditation Framework (DICAF) — developed to ensure consistency in the authorisation process for all Defence ICT systems that process, store or communicate official, sensitive or classified information — has been in draft since December 2015. As at May 2024, the DICAF remains incomplete with a placeholder remaining for a key section that was to be developed on the assessment and authorisation process. In response to shortcomings identified in the DICAF by an internal audit in May 2020, Defence developed a separate ‘Assessment and Authorisation Framework’ document in December 2021. The framework was approved by Defence’s Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) in February 2024 and released in May 2024. (See paragraphs 2.39–2.51)

20. Defence does not have an up-to-date set of consolidated guidance to support the implementation of its framework in a consistent manner across the organisation. Defence’s assessment and authorisation process guidance is internally inconsistent and a number of supporting templates have not been finalised or are outdated. Separate instructions, directives and policies exist for the Army, Navy and Air Force, which include some requirements that are inconsistent with Defence’s assessment and authorisation process, the DSPF and PSPF. (See paragraphs 2.52–2.73)

21. Defence has not established training to ensure that Security Assessors remain up-to-date on evolving cyber security requirements, instead relying on peer review and Assessment Authority review to mitigate any ‘deficiencies in knowledge’. Deficiencies were identified in Defence’s implementation of the peer review process and Defence does not undertake assurance activities to monitor the extent to which training is completed. The absence of a formalised training approach to support the implementation of DSPF requirements for the assessment and authorisation of ICT systems creates a risk that systems are not being authorised as intended. Defence data on ICT system authorisations shows that 47 per cent of its systems have a status of either ‘Expired’ or ‘No accreditation’, indicating that System Owner obligations in respect to obtaining and maintaining the authorisation of their systems are not being met. (See paragraphs 2.74–2.93)

Implementation of arrangements for the security authorisation of Defence’s ICT systems

22. Defence’s data indicates that the obligations of System Owners to obtain and maintain the authorisation of their systems are not being fulfilled. (See paragraphs 3.5–3.26)

23. Defence self-assesses and reports annually on its compliance with PSPF Policy 11 and has established governance and internal reporting requirements for DSPF controls, including DSPF Control 23.1 ICT Certification and Accreditation. Deficiencies in Defence’s reporting include that:

- Defence has not reported on the authorisation status of ICT systems at an enterprise level since 2018–19 in its PSPF and DSPF reporting (a key indicator of compliance against DSPF Control 23.1 and PSPF Policy 11);

- Defence’s PSPF and DSPF reporting is not consistent with, and does not reflect, other information available within Defence on the assessment and authorisation of its ICT systems; and

- Defence has not complied with the DSPF requirement to provide individual Control Owner reports to the Defence Security Committee since 2019–20. (See paragraphs 3.27–3.68)

24. Defence has not briefed the minister on its ICT assessment and authorisation activities in the last three years. In September 2019, the minister requested that Defence include a metric on the reduction of unapproved systems in an ‘ICT reform stream report’. Defence did not address this request. (See paragraphs 3.69–3.73)

25. Defence has not consistently complied with the requirements of its assessment and authorisation process. For example, for all five systems examined:

- key supporting data had not been entered in Defence’s ICT authorisation management system, and mandatory security documentation had not been provided to the Security Assessors;

- Defence was unable to substantiate that document reviews and control implementation assessments took place; and

- there were shortcomings in the peer review process, including not identifying that mandatory security documentation was missing, and not identifying inaccuracies and errors in Risk Assessments. (See paragraphs 3.74–3.90)

26. There were instances where systems had been re-authorised based on the re-authorisation triggers in the DSPF. These re-authorisations were not always granted prior to authorisation expiry. (See paragraphs 3.91–3.100)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.24

The Department of Defence ensure that DSPF roles and requirements for system assessment and authorisation are complete, current, and regularly reviewed for alignment with the PSPF and Group/Service appointments.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.72

The Department of Defence conducts a review of, and updates, its assessment and authorisation process documentation to ensure:

- alignment with current DSPF and PSPF requirements;

- consistency across all internal guidance documents, including those developed by the ADF Services; and

- that any internal inconsistencies within individual guidance documents are eliminated.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.89

The Department of Defence:

- implements improved training and awareness raising activities to ensure that key personnel involved in the assessment and authorisation process are aware of their obligations under the PSPF and DSPF, and remain up-to-date with evolving cyber security requirements; and

- implements a framework to monitor and report on the completion of training and awareness raising activities.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.25

The Department of Defence develops and implements processes to ensure that information entered into its ICT authorisation management system is complete, accurate, and supports effective monitoring of ICT system authorisations.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.45

The Department of Defence:

- implement enterprise-wide assurance arrangements to support the effective implementation of DSPF system authorisation requirements; and

- implement arrangements to ensure that deficiencies and non-compliance identified through Service assurance activities relating to system authorisations are addressed and rectified.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.67

The Department of Defence implement arrangements to ensure reporting to senior Defence leadership on compliance with system authorisation requirements under the PSPF and DSPF is comprehensive, accurate, and based on available data.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.72

The Department of Defence:

- ensures that relevant ministers are provided with timely and accurate advice on key issues and risks relating to Defence’s ICT security authorisations and its compliance with the PSPF; and

- provides regular (at least annual) updates to relevant ministers to support oversight for improvements to its assessment and authorisation policies, frameworks and processes.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 3.98

The Department of Defence implements arrangements to ensure that PSPF requirements, DSPF requirements and Defence’s assessment and authorisation process are complied with, including:

- ensuring that all required documentation has been completed prior to system assessment and authorisation;

- documenting the approval and review of mandatory supporting documentation;

- conducting and documenting assessments of the implementation and effectiveness of controls and provisional authorisation conditions against all relevant ISM and DSPF controls; and

- ensuring systems are proactively monitored against the conditions for re-authorisation.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Summary of the Department of Defence’s response

27. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Defence. Defence’s summary response is provided below, and its full response is included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Defence welcomes the Auditor-General Report: Defence’s Management of ICT Security Authorisation. Defence agrees to the eight recommendations aimed at improving Defence’s Cyber Security Assessment and Authorisation Framework to more effectively govern and monitor the authorisation of ICT systems and networks and control cyber-related ICT risk.

Defence is committed to strengthening and standardising our approach to safeguarding data from cyber threats and ensuring the secure operation of our ICT systems to protect the continuous delivery of Defence outcomes. Defence is currently reviewing its Cyber Security Assessment and Authorisation Framework, along with the associated policies, practices and processes, as part of Defence’s wider initiative to uplift cyber security governance and its cyber risk management framework. This includes an overhaul of several pertinent Defence Security Principles Framework policies, which are undergoing review, along with a program to drive Essential 8 Maturity.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

28. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The security of government information and communications technology (ICT) systems, networks and data supports Australia’s social, economic and national security interests as well as the privacy of its citizens. Malicious cyber activity has been identified as a significant threat affecting Australians, exacerbated by low levels of cyber maturity across many Australian Government entities.7

1.2 The Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) Cyber Threat Report 2022–23 identified that:

the regional strategic environment continues to deteriorate, which is reflected in the observable activities of some state actors in cyberspace. In this context, these actors are increasingly using cyber operations as the preferred vector to build their geopolitical competitive edge, whether it is to support their economies or to underpin operations that challenge the sovereignty of others. In the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation’s Annual Report 2021–22, espionage and foreign interference was noted to have supplanted terrorism as Australia’s principal security concern.8

1.3 The Department of Defence’s (Defence’s) mission and purpose is to defend Australia and its national interests in order to advance Australia’s security and prosperity. Defence’s 2022–23 Annual Report states that, to enable the warfighting capabilities of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) globally, it is supported by one of the largest and most complex ICT environments in the nation.9

1.4 Defence’s 2022 Cyber Security Strategy states that ‘Malicious cyber activity now represents one of Defence’s most critical risks.’10 This risk was reflected in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review, which found that limited workforce availability had resulted in project slippage and insufficient ADF and Australian Public Service (APS) staff to manage heavily outsourced ICT functions. The review recommended:

- the appointment of a ‘dedicated senior official for Chief Information Officer Group (CIOG) capability management leadership and a dedicated senior official accountable for [Defence’s] secret network’, and rebalancing of the CIOG workforce to a 60:40 APS- and ADF-to-contractor ratio;

- enhancement of Defence’s cyber security arrangements in collaboration with ASD; and

- increasing Defence’s cyber security operations capability in CIOG and decommissioning legacy systems and platforms.11

1.5 The Australian Government agreed to the recommendations.

Protective Security Policy Framework

1.6 The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) was introduced in 2010 to help Australian Government entities protect their people, information and assets, both at home and overseas. The PSPF sets out the government’s protective security policy approach and is comprised of 16 core policies.12 Under the PSPF, all entities are required to develop their own protective security policies and procedures. PSPF Policy 10 Safeguarding data from cyber threats and Policy 11 Robust ICT systems outline how entities can safeguard their ICT systems and mitigate their exposure to cyber security risks.

PSPF Policy 10 — Safeguarding data from cyber threats

1.7 PSPF Policy 10 Safeguarding data from cyber threats requires entities to mitigate common security threats by implementing eight essential mitigation strategies (the Essential Eight).13 Prior to February 2022, only four of the strategies were mandatory. Entities must implement Maturity Level 2 for each of the eight strategies to be compliant.14 Defence’s system authorisation process requires consideration of the Essential Eight as part of supporting security documentation (see paragraphs 2.58–2.59).

PSPF Policy 11 — Robust ICT systems

1.8 PSPF Policy 11 Robust ICT systems requires that entities ensure the secure operation of their ICT systems to safeguard their information and data and the continuous delivery of government business by applying the Information Security Manual’s (ISM) cyber security principles during all stages of the lifecycle of each system. Specifically, PSPF Policy 11 requires that:

Entities must [emphasis in original] only process, store or communicate information and data on an ICT system that the determining authority (or their delegate) has authorised to operate based on the acceptance of the residual security risks associated with its operation.15

When establishing new ICT systems, or implementing improvements to an existing system, the decision to authorise (or reauthorise) a system to operate must [emphasis in original] be based on the Information Security Manual’s six step risk-based approach for cyber security.16

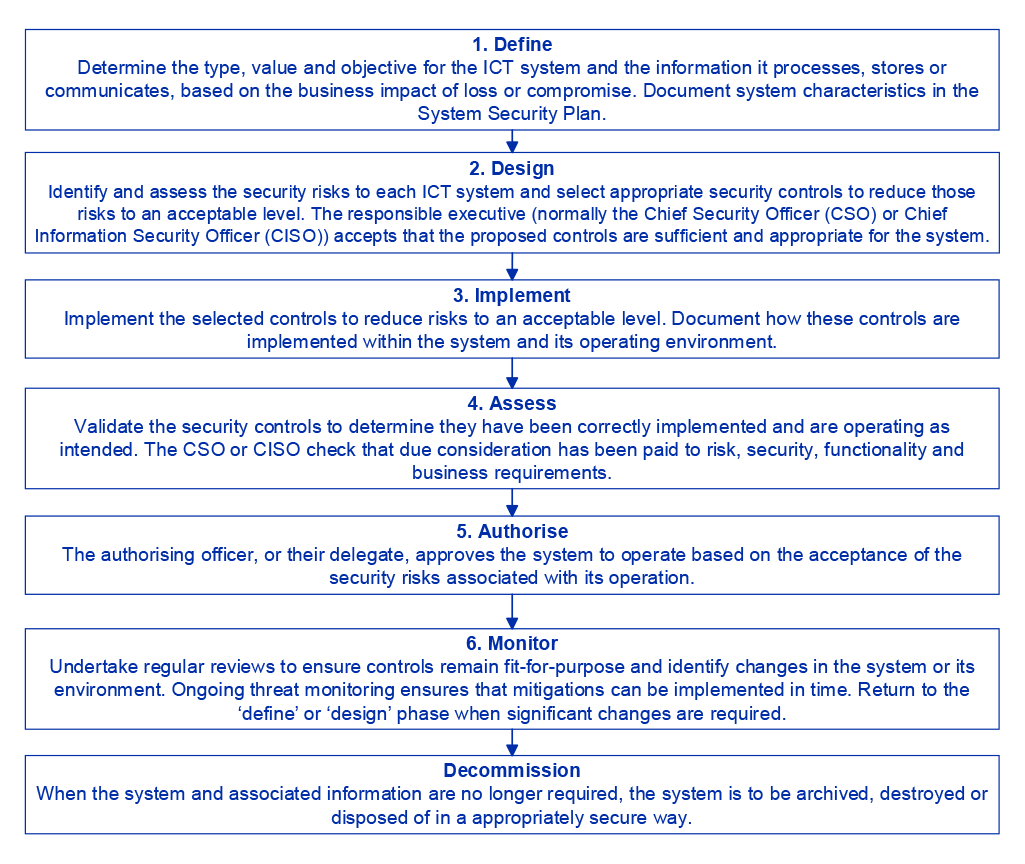

1.9 The ISM six-step process is outlined in Figure 1.1 below.

Figure 1.1: ISM six-step risk-based process

Source: ANAO analysis of PSPF Policy 11.

1.10 Prior to August 2020, PSPF Policy 11 used the terms ‘certification’ and ‘accreditation’ and referred to the key decision-making roles for certification and accreditation as the ‘certification authority’ and ‘accreditation authority’ respectively. Since August 2020, PSPF Policy 11 refers to ‘certification’ as ‘assessment’ and ‘accreditation’ as ‘authorisation’. The key decision-making roles for assessment and authorisation have been defined in PSPF Policy 11 as the Chief Security Officer (CSO) or Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) and ‘authorising officer’ respectively.17

ICT system authorisations in Defence

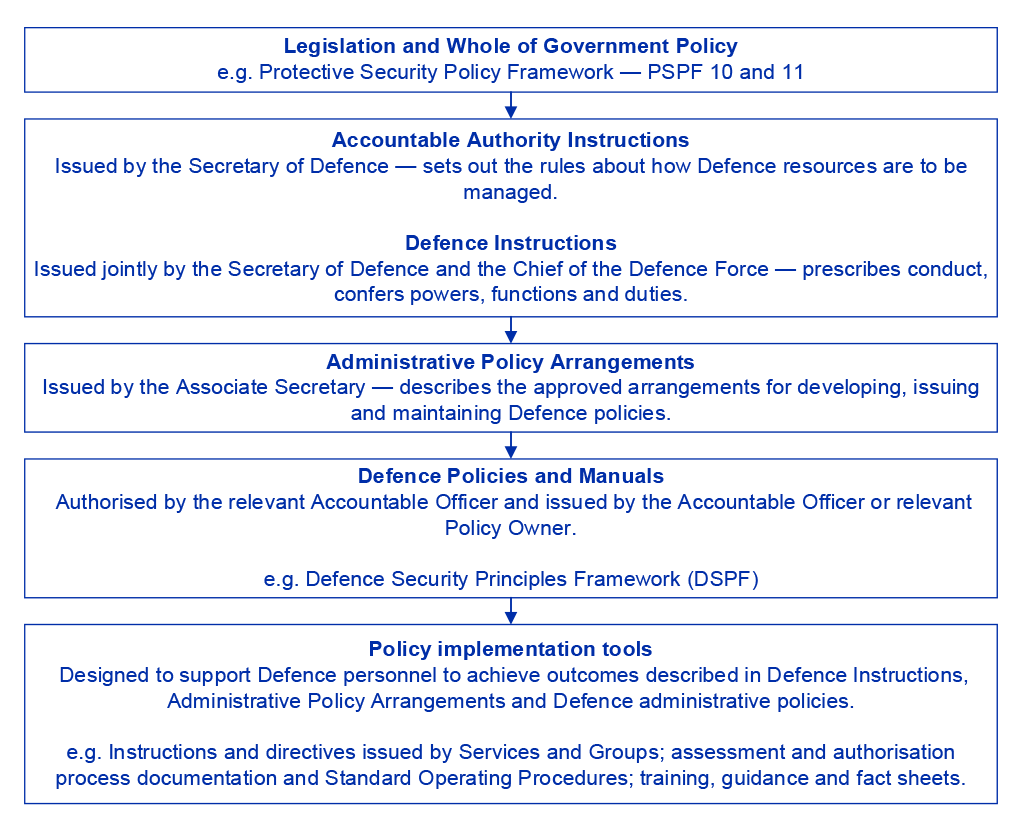

1.11 Defence has developed Administrative Policy Arrangements which establish the authority and hierarchy for Defence documents. This hierarchy, and its relationship to key documents referred to throughout this report are outlined in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Hierarchy of Defence documents

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence’s Administrative Policy Arrangements.

Defence Security Principles Framework

1.12 Defence has established the Defence Security Principles Framework (DSPF) to support compliance with the requirements of the PSPF. DSPF Principle 23, which is supported by Control 23.1 ICT Certification and Accreditation, outlines Defence’s requirements for ICT assessment and authorisation including that:

- all Defence ICT systems must be authorised prior to processing, storing or communicating official information;

- the authorising officer is based on the level of assessed system risk; and

- ICT systems are to be re-authorised under various conditions including when: new or emerging threats are identified; a cyber security incident occurs; changes to the certified system architecture occur; or the system’s authorisation expires.

1.13 The DSPF is supported by directives and instructions issued by Defence’s Services and Groups, discussed further at paragraphs 2.26–2.38.

Defence Cyber and Information Assurance Branch

1.14 The Defence Cyber and Information Assurance Branch (DCIAB) sits within Defence’s Cyber Command18 and is responsible for ensuring cyber security risks are effectively quantified and managed across Defence systems and networks. This includes the provision of ICT system assessment and authorisation services conducted by the Cyber Security Assessments and Authorisation (CSAA) Directorate within DCIAB. Defence’s CISO is the head of DCIAB.19

1.15 Between 2020–21 and 2022–23 DCIAB’s expenditure increased by 234 per cent. The number of contractors engaged by DCIAB increased by 72 per cent and the number of APS and ADF personnel increased by 3 per cent over the same three-year period.

Defence ICT systems

1.16 Defence defines a ‘system’ in its ‘Cyber Security Assessment and Authorisation Framework’ as:

a single or a group of interacting Information and Communication Technology (ICT) hardware and/or software components that enable users to accomplish a task (i.e. that stores, processes or communicates information). Systems may include other systems.

1.17 In September 2021, Defence commenced an ICT inventory project to develop a ‘comprehensive knowledge base of all current Defence portfolio ICT systems, networks, applications and services’ (see paragraphs 3.7–3.11).

1.18 Approximately 48 per cent of the systems that have been identified through the inventory project are systems that ‘manage the creation, processing, presentation and storage of information’ and need to be authorised in accordance with PSPF Policy 11. Of these systems, 5 per cent were recorded in Defence’s system for managing ICT authorisations as at June 2024. The data recorded in Defence’s ICT authorisation management system is not complete or accurate (see paragraphs 3.15–3.26).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.19 Through its 2022 Cyber Security Strategy, Defence has recognised that ‘Malicious cyber activity now represents one of Defence’s most critical risks.’ Robust ICT systems protect the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the information and data that entities process, store and communicate. PSPF Policy 11 outlines how entities can safeguard ICT systems through assessment and authorisation activities to support the secure and continuous delivery of government business.

1.20 Questions regarding Defence’s system authorisation process were raised at hearings of the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee in June 2021, including in relation to:

- Defence’s use of provisional authorisations beyond 12 months for systems where security concerns have not been sufficiently addressed;

- deficiencies in Defence’s processes for identifying and assessing risks as part of the authorisation process; and

- DSPF compliance with the ISM.

1.21 This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s arrangements for the management of ICT systems security authorisations.20

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria, and scope

1.22 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s arrangements to manage the security authorisation of its ICT systems.

1.23 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Does Defence have fit-for-purpose arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems?

- Has Defence implemented its arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems?

1.24 The audit scope included examination of the arrangements Defence has in place to identify, assess, and mitigate or accept ICT system security risks, and examination of Defence’s implementation of its arrangements. ICT systems included in the scope of the audit are systems that process, store or communicate official information.

1.25 The scope did not include examination of the authorisation of Top Secret ICT systems. These authorisations are done by the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), not Defence.

Audit methodology

1.26 The audit methodology included discussions with relevant Defence officials and an examination and analysis of Defence records.

1.27 The audit was open to contributions from the public. The ANAO did not receive any submissions.

1.28 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $504,803.

1.29 The team members for this audit were Jarrad Hamilton, Hugh Balgarnie, Candy Chu, Sky Lo, and Amy Willmott.

2. Defence’s arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence (Defence) has fit for purpose arrangements in place for the security authorisation of its ICT systems.

Conclusion

Defence’s arrangements for the security authorisation of its ICT systems are partly fit for purpose. Defence’s policies, frameworks and processes to support system assessment and authorisation have not been regularly reviewed or updated to align with Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) and Defence Security Principles Framework (DSPF) requirements. These policy and process documents are internally inconsistent. Defence has not established training to ensure that key personnel involved in the authorisation process remain up-to-date with changing cyber security requirements in the Information Security Manual (ISM) and PSPF.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: reviewing and updating the DSPF and Defence’s assessment and authorisation process; and implementing improved training to ensure key assessment and authorisation personnel are aware of their obligations under the PSPF and DSPF.

2.1 Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) Policy 11 Robust ICT systems mandates that entities must only process, store or communicate information and data on an ICT system that the ‘determining authority’ has authorised to operate based on the acceptance of the residual security risks associated with its operation. The decision to authorise a system must be based on the Information Security Manual’s (ISM’s) six-step risk-based approach to cyber security (see Figure 1.1).

2.2 Since February 2022, PSPF Policy 10 Safeguarding data from cyber threats has required entities to mitigate common security threats by implementing eight essential mitigation strategies, known as the ‘Essential Eight’ (see footnote 13). Prior to this update, only four of the strategies were mandatory. Defence has established policies to support PSPF Policy 10 and 11 through ICT assessment and authorisation in the Defence Security Principles Framework (DSPF) and Service-level directives, instructions, and policies.

Has Defence established an appropriate policy and governance framework for the security authorisation of its ICT systems?

Defence has not appropriately maintained its policy and governance framework for the authorisation of its ICT systems. When the DSPF was implemented in July 2018, some sections were not complete, with key authorisation roles listed but not defined for 13 of the 14 Defence Services and Groups listed. These roles remained undefined until a May 2024 review of the DSPF. Prior to the May 2024 update, DSPF Principle 23 and DSPF Control 23.1 had not been updated since July 2020. This meant that key changes to the mandatory requirements in PSPF Policies 10 and 11 between August 2020 and February 2022 — such as the introduction of the ‘Essential Eight’ and the ISM six-step process for system assessment and authorisation — were not reflected in the DSPF until 10 May 2024.

Directives, instructions, and policies issued by the Australian Defence Force (ADF) services for ICT authorisations for Army, Navy and Air Force systems contain provisions that are either not consistent with or not permitted by the requirements of the DSPF, or PSPF Policy 11. These provisions have allowed for exemptions to Defence’s system authorisation process that are not permitted under the DSPF or PSPF.

A key supporting framework, the Defence ICT Certification and Accreditation Framework (DICAF) — developed to ensure consistency in the authorisation process for all Defence ICT systems that process, store or communicate official, sensitive or classified information — has been in draft since December 2015. As at May 2024, the DICAF remains incomplete with a placeholder remaining for a key section that was to be developed on the assessment and authorisation process. In response to shortcomings identified in the DICAF by an internal audit in May 2020, Defence developed a separate ‘Assessment and Authorisation Framework’ document in December 2021. The framework was approved by Defence’s Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) in February 2024 and released in May 2024.

Defence Security Principles Framework

2.3 Defence has established its primary policy requirements for ICT system assessment and authorisation through the DSPF. The DSPF was introduced in July 2018, replacing the Defence Security Manual (DSM). The introduction of the DSPF reflected Defence’s stated transition from a ‘compliance model of security management under the Defence Security Manual’ to a ‘principles based approach’ under the DSPF. The DSPF states that this approach:

- Allows all parts of Defence to manage security within their operational context and constraints. This recognises the best security decisions are made in accordance with agreed principles, with a desired outcome in mind.

- Ensures the most appropriate people are setting security requirements. Those who know their business are best placed to set security standards and requirements for that aspect of Defence business.

2.4 Under DSPF Principle 23, Control 23.1 ICT Certification and Accreditation requires that ‘All Defence ICT systems must be accredited prior to processing, storing or communicating Official information’ and outlines: Defence’s high-level process for assessment and authorisation, including Authorising Officer levels, which are aligned to risk ratings; an assessment and authorisation flowchart; and requirements for re-authorising ICT systems.

2.5 The DSM included similar authorisation requirements to the DSPF, but also included additional requirements that were not retained after the introduction of the DSPF, such as:

- annual review and monitoring of authorised ICT systems (see footnote 74);

- mandatory training for Authorising Officers (see paragraph 2.74);

- recording the extent of a system’s compliance against all applicable ‘must’ and ‘should’ statements contained in the ISM, as part of the assessment process;

- the issuing of a dispensation (provisional authorisation) for a specified timeframe by the relevant Group Head or Service Chief in exceptional circumstances;

- the closure of a system and withdrawal of provisional authorisation where there is a failure to meet the conditions of the authorisation within the specified timeframe; and

- not using the provisional authorisation process ‘as a means to circumvent the proper application’ of the authorisation process.

2.6 The DSPF states that it is a ‘flexible policy framework’ and that ‘DSPF documents will be reviewed and updated as necessary’. Prior to 10 May 2024, DSPF Principle 23 was last approved by the Chief Security Officer in July 2020, and had not been updated to reflect amendments made to PSPF Policy 11 in August 2020, including mandating the ISM’s six-step authorisation process and changes to PSPF language.21 An updated version of DSPF Principle 23 and Control 23.1, which reflects the six-step process and updated PSPF language, was approved by the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) on 10 May 2024.

2.7 DSPF Control 20.1 Information Systems Lifecycle Management was last reviewed in July 2020 and only recognises four of the ISM’s Essential Eight strategies as being mandatory. This is not in line with the requirements of PSPF Policy 10, which were amended in February 2022 and state that ‘[t]o meet the minimum requirements established under the PSPF maturity model, entities must implement Maturity Level Two for each of the eight essential mitigation strategies’.

DSPF roles and responsibilities

2.8 Roles and responsibilities for personnel involved in the assessment and authorisation process are primarily established in the DSPF through Control 20.1 Information Systems Lifecycle Management and Control 23.1 ICT Certification and Accreditation.

2.9 Prior to updates to the DSPF in May 2024, the Control Owner for these controls was Defence’s IT Security Advisor (ITSA), which is an Executive Level 2 (EL2) position.22 The DSPF states that Controls Owners are ‘An SES or ADF [Australian Defence Force] Star Rank Officer assigned accountability and authority to manage a specific defence security risk. These will be derived from the DSPF Principles and Expected Outcomes. The relevant Control Owner in each instance may be a Group Head or Service Chief, or a more appropriate subordinate’. As at March 2024, the only controls in the DSPF delegated below SES or ADF Star Rank Officer level were controls delegated to the ITSA. The CISO (an SES Band 1 Officer) has been appointed as the Control Owner in Defence’s May 2024 updated DSPF Control 23.1.The ITSA no longer has a defined role in the updated DSPF Control 23.1.

2.10 Table 2.1 outlines the roles and responsibilities as established in the July 2020 approved DSPF controls (which applied at the time this audit commenced in November 2023).

Table 2.1: ICT security authorisation roles and responsibilities, as per July 2020 DSPF

|

Role title (and classification) |

Role description |

|

Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) Classification: SES Band 1 |

|

|

Information Technology Security Advisor (ITSA) Classification: EL2 |

|

|

Accreditation Authority Classification: EL1/O4 to SES3/3-Star. Referred to as ‘Authorising Delegate’ in the updated May 2024 DSPF Control 23.1. Referred to as ‘Authorising Officer’ in PSPF Policy 11 and in this report. |

|

|

Certification Authority Referred to as ‘Assessment Authority’ in this report (and in the updated May 2024 DSPF Control 23.1). Classification: EL2/O5 to SES3/3-Star. |

|

|

Certification Consultant Referred to as ‘Security Assessor’ in this report (and the updated May 2024 DSPF Control 23.1). |

|

|

System Owner |

|

Note a: This responsibility is established under Control 19.1 Information Systems (Logical) Security.

Note b: As discussed at footnote 19, ICTSB transitioned to DCIAB as part of a restructure in December 2023.

Note c: Since 2018, the DSPF has established the Commanding Officer of Air Force’s 462 Squadron as the Assessment (Certification) Authority for Air Force standalone systems. PSPF Policy 11 stipulates the Chief Security Officer (CSO) or CISO as the responsible officer for ensuring that the assessment process has given due consideration to ‘risk, security, functionality and business requirements’. Prior to being updated in August 2020, PSPF Policy 11 established the CSO (or delegated security advisor) as the ‘Certification Authority’. Defence advised the ANAO in June 2024 that the Commanding Officer of 462 Squadron was delegated the Authorising Officer role from Air Force’s Provost Marshall (the Air Force’s Single Service Security Authority) ‘well before the creation of the PSPF / DSPF and the CSO role. This delegation is understood to have been grandfathered into the DSPF in 2018 from the Defence Security Manual.’

Note d: Defence advised the ANAO in May 2024 that no formal Control Owner approval has been provided for Defence’s assessment and authorisation process (discussed at paragraphs 2.53–2.73), Deputy Chief of Army Directive 01-20 — Army ICT Security Plan (discussed at paragraphs 2.27–2.30), the Navy Cyberworthiness policy (discussed at paragraphs 2.31–2.32) or Air Force instruction AFSI (OPS) 05-02 (discussed at paragraphs 2.33–2.35). Defence further advised in June 2024 that Control Owner approval was not provided for Air Command Standing Instruction AC SI(OPS) 05-50 (discussed at paragraph 2.36).

Note e: The ‘Assessment Authority’ role is not specifically outlined in PSPF Policy 11. As noted at Note c, PSPF Policy 11 stipulates the CSO or CISO as the responsible officer for ensuring that the assessment process has given due consideration to ‘risk, security, functionality and business requirements’.

Note f: The DSPF states that whether an outside consultant will be required ‘will be dependent on the Group/Service and the Protective Marking of the material to be processed, stored and communicated on the system’.

Note g: Defence advised the ANAO in August 2024 that this requirement was included to ensure that the assessment of systems outside of the CISO’s assessment responsibilities (such as Air Force systems) were reported to the ITSA.

Source: ANAO analysis of the DSPF.

2.11 The DSPF also establishes Authorising Officer ‘escalation thresholds’ for system authorisation, outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: DSPF system authorisation escalation thresholds per July 2020 DSPF Control 23.1

|

Risk rating |

Authorising officer — Chief Information Officer Group (CIOG) managed or connected systems |

Authorising officer — Group/Service managed systems |

|

Low |

Minimum SES Band 1 or 1 Star. |

EL1 or O4a employed in a relevant ICT security role. |

|

Moderate |

Minimum SES Band 1 or 1 Star. |

EL2 or O5b employed in a relevant ICT security role. |

|

Significant |

Minimum SES Band 1 or 1 Star. |

Appointed Cyber Security Advisor (CSA) or the ITSA in the event that a CSA has not been appointed. |

|

High |

SES Band 2 or 2 Star. |

Appointed Cyber Security Executive (CSE) or the CISO in the event that a CSE has not been appointed. |

|

Extreme |

SES Band 3 or 3 Star. |

Appointed Group Head or Service Chief. |

Note a: O4 rank is equivalent to a Lieutenant Commander (Navy), Major (Army), or Squadron Leader (Air Force).

Note b: O5 rank is equivalent to a Commander (Navy), Lieutenant Colonel (Army), or Wing Commander (Air Force). The updated DSPF Control 23.1, approved by the CISO in May 2024: does not distinguish between CIOG systems and Group/Service systems; has set the minimum level for risk acceptance as SES Band 1 or 1 Star; and does not refer to CSA or CSE roles.

Source: ANAO analysis of DSPF.

2.12 The DSPF also includes tables to outline the specific personnel appointed to the roles of Authorising Officer, Assessment Authority, Cyber Security Executive (CSE) and Cyber Security Advisor (CSA) for 14 Defence Services or Groups and five ‘Special Portfolios’.23 As noted in Table 2.1, these positions are the key decision-makers for system assessment and authorisation.

2.13 Until DSPF Control 23.1 was updated in May 2024, the following details were missing for the six years since the DSPF was established in 2018:

- the responsible CSE had not been defined for 13 Services or Groups;

- the responsible CSA had not been defined for 12 Services or Groups; and

- the responsible Authorising Officer, Assessment Authority, CSE, and CSA had not been defined for three special portfolios.

2.14 Further, the Groups and Services reflected in the DSPF had not been updated to reflect structural changes made in Defence since July 2020. For example:

- various groups are not included, such as the Associate Secretary Group, Australian Defence Force Headquarters, Defence Intelligence Group, Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Group, and Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group; and

- four Groups listed either no longer exist or have been renamed.24

2.15 Defence’s September 2022 draft Cyber Security Enterprise Governance Framework, established to consolidate and describe the governance arrangements that support cyber security in Defence, noted that:

The DSPF … is out of date with references to roles and responsibilities that are no longer relevant, to authorities and delegations that do not match the positions and there are several gaps or areas with TBC roles, responsibilities and expectations have not been defined. Some updates to the DSPF are planned however, more are required and the cadence for these updates needs to be more frequent to keep up with the evolving security landscape.

2.16 As a result of the May 2024 update, the DSPF Control 23.1 no longer includes a table of specific personnel appointed to key decision-making roles, but states that ‘[t]he list of the appointments for Groups and Services who can assess and authorise Defence ICT systems prior to operational use can be located on the Defence Intranet’. The DCIAB intranet page includes a list of ‘functional appointments for Groups and Services across Defence’ that was updated in April 2024. The updated list aligns with the current Defence organisational structure, and the Assessment Authority and Authorising Officer appointments are complete for all Groups and Services. The list of appointments does not include CSA or CSE roles.

Assessment and authorisation independence requirements

2.17 As outlined in Table 2.1, Security Assessors are required to maintain independence throughout the assessment process. Under the July 2020 DSPF Control 23.1, System Owners were required to maintain independence from the Authorising Officer.25

2.18 Defence advised the ANAO in February 2024 that Conflict of Interest and Statutory Declaration forms are completed for each contractor, and that it maintains a list of contractors against each Security Assessor to ensure they are not assigned assessment of a system to which a company in their employment chain has a stake.26 Defence further advised that ‘This process is not currently formalised within policy.’

2.19 Defence advised the ANAO in May 2024 that independence between the System Owner and Authorising Officer is maintained ‘through checks performed by the Certification Consultant [Security Assessor] as part of commencing and completing the Security Assessment Report and development of the [Decision] Brief’ and that this check ‘is not currently formalised in [Assessment and Authorisation] process documentation’.

Delegating system authorisation

2.20 PSPF Policy 11 notes that ‘An impartial (and in some cases independent) security assessment can be a valuable tool in authorisation decisions.’ As outlined in Table 2.2, under the July 2020 DSPF Control 23.1, the CISO was the Authorising Officer, responsible for authorising high-risk Group/Service managed systems where a CSE has not been appointed. As outlined in Table 2.1, the Assistant Secretary of the ICT Security Branch, who fulfils the role of CISO, is also the Assessment (Certification) Authority, responsible for assessing all ICT systems except those within Air Force. Thus, under the July 2020 DSPF Control 23.1, for high-risk Group/Service managed systems where a CSE had not been appointed, the CISO could both assess and authorise those systems. For significant-risk Group/Service managed systems where a CSA had not been appointed, the Authorising Officer was the ITSA, who reports directly to the CISO. The May 2024 updated DSPF Control 23.1 and associated list of appointments (see paragraph 2.16) no longer provides for the CISO or ITSA to fulfil Authorising Officer roles.

2.21 ANAO analysis of Defence’s ICT authorisation management system data identified systems where the CISO was recorded as both the Assessment Authority and Authorising Officer. Of the systems which had an Authorising Officer recorded, 7 per cent had recorded the Authorising Officer as the ‘Chief Technology Officer / Chief Information Security Officer’. For 18 per cent of those systems the CISO was also the Assessment (Certification) Authority.

2.22 Army, Navy and Air Force have each appointed CSAs and CSEs. Chief of Army Directive 02/20, issued in March 2020, states that, while the Director General Special Operations Modernisation is not a CSA, that position is responsible for authorising systems with significant risk.27 The DSPF does not provide for the Authorising Officer role to be delegated to this position.28 Army Standing Instruction (Protective Security) was signed by the Chief of Army in August 2022, and superseded Directive 02/20. The Standing Instruction appointed the CSA role to the Director General Land Operations.29

2.23 In response to an internal audit in May 2020 into Certification and Accreditation of Defence ICT Networks, which found that Defence’s assessment and authorisation process lacked clarity and consistency, Defence advised that it would conduct an ‘evaluation of current delegated Accreditation and Certification Authorities and determination of the appropriate approach to future delegation of Accreditation and Certification Authority’.30 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2024 that amendments to delegations are being made as part of the transition to the Assessment and Authorisation Framework (see paragraphs 2.49–2.51).

Recommendation no.1

2.24 The Department of Defence ensure that DSPF roles and requirements for system assessment and authorisation are complete, current, and regularly reviewed for alignment with the PSPF and Group/Service appointments.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.25 Defence will implement a continuous improvement function for the assessment and authorisation (A&A) approach as part of the newly established Cyber Security Policy hub. This function will be responsible for maintaining currency of all A&A delegations and authorities, as well as ensuring continued alignment and compliance with the PSPF and ISM.

ADF service group policies

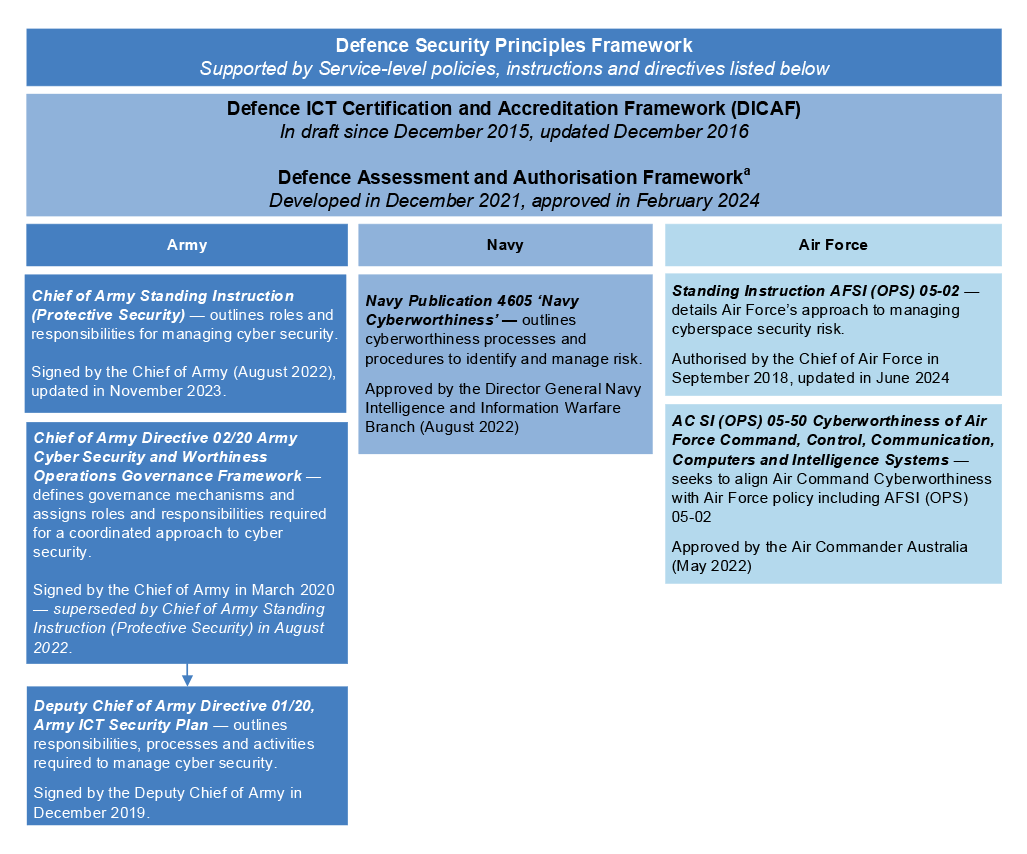

2.26 Army, Navy and Air Force have each issued policies, instructions or directives to support compliance with DSPF Principle 23 and Defence’s assessment and authorisation process (discussed at paragraphs 2.53–2.73).31 Figure 2.1 outlines the documentation issued by Army, Navy and Air Force to support DSPF Principle 23 as at July 2024.

Figure 2.1: Service-level documents supporting the DSPF

Note a: Defence advised the ANAO in August 2024 that the Assessment and Authorisation Framework ‘was developed to replace the DICAF’.

Note: Where a document hierarchy has been established in Service issued documentation, this is reflected by arrows in Figure 2.1. The remaining documents are ordered by the seniority of the approving officer.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

2.27 In December 2019, the Deputy Chief of Army issued Directive 01/20 Army ICT Security Plan to ‘provide clear direction on the responsibilities, processes and activities required to effectively manage the Cyber Security and Worthiness of Army’s in-service ICT and information assets.’ In this context, the directive:

- states that ‘all Army ICT systems must be accredited prior to processing, storing or communicating unofficial, official, sensitive or classified Defence information’; and

- outlines System Owner responsibilities for monitoring the expiry of system authorisations and seeking re-authorisation, as well as the requirements for system security documentation.

2.28 For ‘Some Distribution Limitation Marker (DLM) or FOUO [For Official Use Only] systems’ the Chief of Army directive provides for a ‘streamlined security assessment’ and approval process ‘in lieu of a formal certification and accreditation.’

2.29 Defence advised the ANAO in April 2024 that this streamlined process was ‘a reference to an old and obsolete … whitelisting process and that all Defence (Army) systems are to go through the normal accreditation process’. Defence also advised that:

the updated version of the Army ICT Security Plan (currently awaiting delegate approval) states “IAW [in accordance with] DSFP Principle 23, all Army ICT … systems must be accredited prior to processing, storing or communicating official or classified Defence information”.

2.30 As noted at paragraph 2.27, this requirement was set out in the 2019 Deputy Chief of Army directive. Defence advised the ANAO in June 2024 that the Army ICT Security Plan was ‘in the final stages of review prior to release’.

2.31 In August 2022, Defence released a Navy ‘Cyberworthiness’ policy, approved by the Director General of Navy Intelligence and Information Warfare to ‘significantly reduce cyberworthiness risks to all Navy owned ICT … materiel and support systems.’32 The policy notes that the DSPF is the ‘authoritative source for managing security risks and their associated controls’, and outlines the ISM six-step process for system assessment.

2.32 Defence acknowledges in the cyberworthiness policy that some inconsistency exists between the policy and the DSPF — namely, that Navy’s system for rating risks does not align with the DSPF’s risk evaluation matrix.33 The policy also states that the Chief of Navy is the System Owner for all Navy systems and the Authorising Officer for systems with a risk rating of ‘Extreme’. This means that for systems with an ‘Extreme’ risk, the Chief of Navy is both the System Owner and the Authorising Officer — a situation that does not align with the DSPF. As outlined in Table 2.1, the July 2020 DSPF requires the System Owner to be independent of the Authorising Officer.

2.33 Air Force instruction AFSI (OPS) 05-02, issued in September 2018, details Air Force’s approach to managing cyberspace security risk. The instruction establishes the Commanding Officer of 462 Squadron (462SQN) as the ‘Certification Authority’ for Air Force and states that ‘Air Force information systems owners may use other DSPF authorised Certification Authorities if 462SQN is unable to support (due to either lack of capacity or specialist skill requirements) or where a more suitable option exists’.

2.34 The instruction requires that Air Force information systems are assessed and authorised in accordance with the ISM and DSPF. The instruction also states that:

Where a system is to be force assigned34 without or with partial certification, risks and limitations are to … be recorded as part of the certification.

2.35 This statement is not aligned with the DSPF requirement that all Defence ICT be authorised prior to processing, storing or communicating official information. This statement is also not in accordance with Chief of Joint Capabilities Directive 07-20 ADF Cyberworthiness Governance Framework, issued in December 2020, which states that Capability Managers ‘are to ensure that only certified and accredited mission systems are force assigned to operations, and that this status is verified during pre-deployment’. The directive outlines that the ADF Cyberworthiness Governance Framework is for ‘implementation across the Services to ensure cyberworthiness efforts are streamlined, consistent and effective.’

2.36 A further Air Force instruction, AC SI(OPS) 05-50 Cyberworthiness of Air Force Command, Control, Communication, Computers and Intelligence Systems, issued in May 2022, also outlines assessment and authorisation requirements. The instruction notes that:

a Provisional ICT Accreditation (PICTA) is awarded where the Accreditation Authority has requested further controls and/or risk mitigation activities to be undertaken during the provisional accreditation period …

A PICTA achieves efficiencies through reduced rework of C&A [Certification and Accreditation] activities. Ref D [AFSI (OPS) 05-02 – Cyberworthiness, Certification and Accreditation] identifies that a PICTA may be upgraded to an ICTA without undertaking a full re-certification activity.

2.37 AFSI (OPS) 05-02 does not address the issuing of provisional authorisations and the DSPF does not provide for provisionally authorised systems to be re-authorised without undertaking a full re-assessment activity.

2.38 The Deputy Chief of Air Force approved an updated version of AFSI (OPS) 05-02 in June 2024. The 2024 instruction does not refer to provisional authorisation and requires all Air Force systems to be authorised prior to operation. The 2024 instruction provides for moderate and low risk systems to be authorised by personnel below Senior Executive Service (SES) 1 or 1 Star officer level. This does not accord with the updated May 2024 DSPF Control 23.1, which requires SES 1 or 1 Star authorisation of these systems.

Defence ICT Certification and Accreditation Framework

2.39 The Defence ICT Certification and Accreditation Framework (DICAF) was developed by the ICT Security Branch (now DCIAB) to ‘ensure that Certification and Accreditation activities are conducted in a repeatable and consistent manner across [Defence]’ and applies to all Defence ICT systems that process, store or communicate official, sensitive or classified information.

2.40 The DICAF has been in draft since December 2015 and was last updated in December 2016.

2.41 The DICAF provides a high-level overview of Defence’s assessment and authorisation requirements. It outlines which systems are subject to the assessment and authorisation requirements and defines the roles and responsibilities of personnel involved in the system authorisation process. A section outlining the detailed process for system assessment and authorisation was to be developed and included with a supporting annex to the DICAF. At July 2024, the process section and the supporting annex had not been developed.

2.42 A draft February 2017 ICT Security report35 provided a progress update on the development of the DICAF and stated that:

Progress is being made to update the draft DICAF based on feedback received from the DICAF Working Group and other stakeholders. It is anticipated that the DICAF will be in releasable format by mid-2017.

2.43 The 2018–19 DSPF Control Owner report for DSPF Control 23.136 provided an update on the DICAF in July 2019, stating that:

ICTSB [now DCIAB] is currently reviewing the extant Cyberspace Security Governance Framework37 with the intention for the new Framework to become a charter to improve stakeholder investment. It is intended that it will absorb the Defence ICT Certification and Accreditation Framework (DICAF) to align cybersecurity governance roles and responsibilities.

2.44 This statement was repeated in the 2019–20 control owner report in July 2020.

2.45 Defence’s Cyberspace Security Governance Framework (CSGF) was last reviewed in November 2016 (as at July 2024). The CSGF states that the DICAF forms part of the ‘related documents and legislation’ for the CSGF. Defence advised the ANAO in March 2024 that:

The Cyberspace Security and Governance Framework (CSGF) is a legacy left over from the original establishment of, and appointments … of the Defence CISO and ITSA in 2015-16 … The decision to delay its revision (as specified in the Control Owners Reports 2018-2019 & 2019-20) was largely because events had overtaken matters with responsibilities of the Cyber Security Governance Board (CSGB) moving across to the enterprise governance committee structures (such as the Defence Security Committee), [which] had achieved improvements to the oversight and control of cyber security related matters. This along with the anticipated changes in cyber security governance expected through the design and delivery of the Defence Cyber Security Strategy and the changes scheduled through [the ICT Security Program] (including the A&A [Authorisation and Assessment] framework) became the primary focus of effort.38

2.46 Defence’s May 2020 internal audit into Certification and Accreditation of Defence ICT Networks identified ‘risks within the existing certification and accreditation process for ICT networks and systems which are not being controlled effectively by the Department.’ The report found that there were inconsistencies in the authorisation processes being applied across Defence, and that the DICAF did not provide sufficient guidance for identifying what systems require authorisation and ensuring a risk-based approach is applied during system assessments.39

2.47 The internal audit recommended that ‘CIOG should re-assess the design of its current Certification and Accreditation Framework, including (as relevant) the policy setting and detailed processes and procedures adopted for the certification and accreditation of ICT networks and systems.’40

2.48 In February 2021, DCIAB’s Directorate of Integrated Risk Management (now the Directorate of Cyber Security Assessments and Authorisation) held a meeting to discuss the development of the DICAF in response to the internal audit findings. The meeting presentation noted that:

There is no authoritative source that defines the “framework”. Previous draft iterations of the Defence ICT Certification and Accreditation Framework (DICAF) did not provide adequate coverage in terms of end to end processes.

2.49 In December 2021, Defence’s Head of ICT Operations (HICTO)41 signed a minute recommending the internal audit recommendation be closed, and outlining action taken to address the findings, including the development of ‘a modernised Certification and Accreditation Framework, known as the Defence Authorisation and Assessment Framework.’

2.50 The framework remained in draft until a final version was approved by the CISO in February 2024 and released in May 2024.

2.51 The framework: outlines roles and responsibilities for assessment and authorisation; defines the systems to which the framework applies; and outlines Defence’s process requirements against each step of the ISM’s six-step process. The framework does not mandate the inspection and validation of control implementation as part of the assessment and authorisation process for all systems. This is not consistent with Step 4 of the six-step process (see Figure 1.1) which requires entities to validate security controls to determine they have been correctly implemented and are operating as intended.

Has Defence developed fit-for-purpose guidance to support the implementation of its framework?

Defence does not have an up-to-date set of consolidated guidance to support the implementation of its framework in a consistent manner across the organisation. Defence’s assessment and authorisation process guidance is internally inconsistent and a number of supporting templates have not been finalised or are outdated. Separate instructions, directives and policies exist for the Army, Navy and Air Force, which include some requirements that are inconsistent with Defence’s assessment and authorisation process, the DSPF and PSPF.

2.52 In September 2021, an assessment and authorisation process was published on the Defence intranet. Documentation developed and issued by Army, Navy and Air Force (see paragraphs 2.26–2.38) refers to the assessment and authorisation process, and stipulates additional requirements and templates, discussed further in the context of the Defence process below.42

Defence’s assessment and authorisation process

2.53 Defence’s assessment and authorisation intranet process sets out four steps: ‘lodge certification and accreditation request’; ‘conduct certification assessment’; ‘review certification assessment’; and ‘finalise certification and accreditation’. A responsibility assignment matrix is documented at each step, outlining responsibilities for key tasks and links to the ISM and DSPF.

2.54 While the intranet process was published on Defence’s intranet after PSPF Policy 11 was amended in August 2020, the process does not reflect the updated language in PSPF Policy 11.43 The process also does not fully reflect the ISM’s six-step process for system assessment and authorisation.44 At July 2024, the assessment and authorisation process was no longer accessible on Defence’s intranet. Defence advised the ANAO in July 2024 that this was due to the intranet page no longer being supported internally and that the content would be made accessible ‘as resourcing allows’.

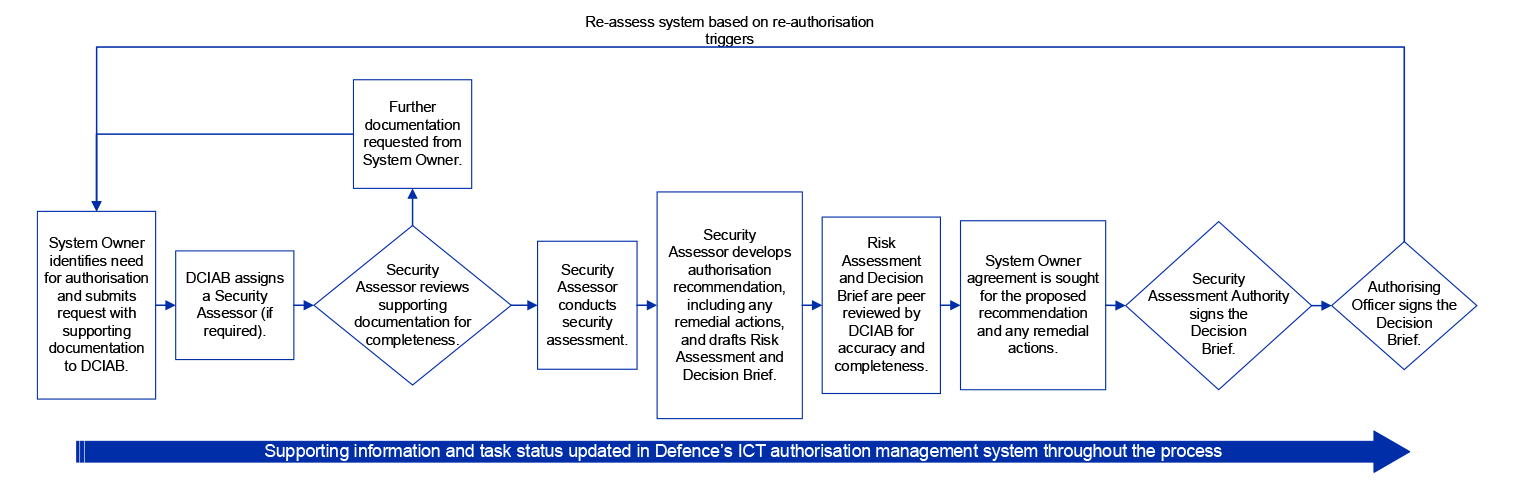

2.55 A summary of Defence’s assessment and authorisation process is shown in Figure 2.2.

Lodge certification and accreditation request

2.56 Requests for the assessment and authorisation of ICT systems are lodged by System Owners or their delegates through Defence’s ICT intranet job portal. The portal requires System Owners to provide key information, including the required operating date for the system, urgency of the request and system classification level. The request is then assessed by a ‘Security Analyst’ to ensure that sufficient information has been provided and to confirm the priority of the request.

2.57 The System Owner is also required to enter system information into Defence’s ICT authorisation management system45, including the assessed Business Impact Level46, and system threats and risks. The System Owner is also required to provide a System Security Plan (SSP) and System Risk Score document.

2.58 Defence’s System Risk Score document enables DCIAB to assess the overall system risk and allocate a risk score, based on the System Owner’s Business Impact Level assessment, system characteristics and potential security management controls. The System Risk Score template is a mandatory document under the assessment and authorisation process. As at July 2024, the October 2013 template had not been updated to reflect Essential Eight requirements.47 The document does not have a stipulated period for review.48

2.59 Defence’s SSP template outlines the information on the system to be authorised, description of system threats and safeguards, compliance with Essential Eight requirements, and processes for detecting and responding to cyber security incidents. The SSP requires executive sign-off and approval prior to being submitted, however neither the assessment and authorisation process nor the linked SSP template identifies the appropriate authority for sign-off.

2.60 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2024 that:

Under the DSPF … System Owners are responsible for developing relevant security artefacts for their systems. If the sign-off/approval requirement is not well understood by the System Owner and/or team, the Certification Consultant will clarify this. However, there is currently no formal or specific guidance advising that the System Owner is the one who signs off on the SSP. This potential ambiguity is being resolved in the latest A&A [Assessment and Authorisation] framework release.

2.61 The Assessment and Authorisation Framework, released in May 2024, did not include any requirements in relation to a SSP sign-off. In June 2024, Defence provided the ANAO with an updated SSP template from March 2024 (which was available on the Cyber Security Assessment and Authorisation intranet page).49 Guidance within the template states that the SSP should be approved by the System Owner.

Figure 2.2: Defence assessment and authorisation process, as at May 2024

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence records.

2.62 Defence’s assessment and authorisation process lists other documentation that ‘may be required depending on the nature and complexity of the system’ including: the SSP Essential Eight Annex50; Security Risk Management Plan (SRMP)51; Defence Logging and Monitoring Guide; Defence Continuous Monitoring Guide; Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)52; and Incident Response Plan (IRP).53 As at June 2024, the templates for the Defence Logging and Monitoring Guide, Defence Continuous Monitoring Guide, and IRP were all listed as ‘pending’ in the process. Defence advised the ANAO in June 2024 that these templates remain under development and are expected to be finalised by August 2024.

2.63 Step 5 of the ISM six-step assessment and authorisation process states that:

Before a system can be granted authorisation to operate, sufficient information should be provided to the authorising officer in order for them to make an informed risk-based decision as to whether the security risks associated with its operation are acceptable or not. This information should take the form of an authorisation package that includes the system’s system security plan, cyber security incident response plan, continuous monitoring plan, security assessment report, and plan of action and milestones.

2.64 Defence advised the ANAO in February 2024 that there is no formal guidance to assist in making the judgement as to whether these additional documents are required as part of the assessment and authorisation process, and that ‘the need for additional documents … will be identified during the certification process and communicated to system delegates’.54

2.65 Following the submission of information and documentation by the System Owner, a Security Assessor (Certification Consultant) and Peer Reviewer are assigned to the task through Defence’s ICT authorisation management system.

Conduct certification assessment

2.66 The Security Assessor reviews the security documentation provided to ensure that documentation is complete and engages with the System Owner if further information is required.55 Once the Security Assessor has sufficient information, they conduct a ‘Stage 1 Assessment’ which includes: a detailed analysis of the system design to assess risks; a determination as to whether appropriate security controls have been implemented; and a review of all relevant controls specified in the ISM and DSPF.

2.67 The Security Assessor also determines whether a cyber assessment is required, based on risk appetite, security requirements, and threat data.56 A ‘Stage 2 assessment’ may also be conducted if the system is a high profile, high risk, or highly complex system and involves cross-checking system inspection findings against documentation to verify the implementation of security controls.57

2.68 Following the assessment, the Security Assessor prepares a Risk Assessment and Decision Brief outlining the security posture of the system, the assessed residual risk, and any suggested remediation actions. If further actions are required, a Remediation Plan may be developed by the Security Assessor and sent to the System Owner.

Review certification assessment

2.69 The Risk Assessment and Decision Brief are reviewed by a peer reviewer. The peer reviewer is a Security Assessor within DCIAB’s Certification Management team58 who conducts a quality assurance check of the Risk Assessment and Decision Brief to assess accuracy and completeness, and determine that the correct approvers have been identified. The report is also reviewed by the System Owner, and any caveats or recommendations, as well as the proposed authorisation outcome are agreed on.

2.70 Once the System Owner has agreed to the Risk Assessment and Decision Brief, the Risk Assessment is signed by the Security Assessor and submitted to the Assistant Director or Director of DCIAB’s Cyber Security Assessments and Authorisation (CSAA) Directorate for final review and sign-off before progressing to the Assessment (or Certification) Authority.

Finalise certification and accreditation

2.71 The Risk Assessment and Decision Brief then proceed to the Assessment Authority (which is the CISO for all Defence systems except for Air Force) for approval. The Decision Brief is supported by the CSAA Directorate approved Risk Assessment, which is included as an attachment to the brief. Once approved by the Assessment Authority, the assessment and brief are then sent to the Authorising Officer for further approval, noting acceptance of the residual risk in operating the system.59 The System Owner is required to be advised of any caveats on the authorisation, and documentation is to be filed to Defence’s records management system, Objective.

Recommendation no.2

2.72 The Department of Defence conducts a review of, and updates, its assessment and authorisation process documentation to ensure:

- alignment with current DSPF and PSPF requirements;

- consistency across all internal guidance documents, including those developed by the ADF Services; and

- that any internal inconsistencies within individual guidance documents are eliminated.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.73 Defence is formalising an A&A [Assessment and Authorisation] Improvement Program to build on and consolidate the current set of A&A initiatives underway. Defence will undertake a comprehensive integrated review of the A&A approach, policies, processes and documentation.

Has Defence developed fit-for-purpose training and other support for personnel responsible for implementing its framework?

Defence has not established training to ensure that Security Assessors remain up-to-date on evolving cyber security requirements, instead relying on peer review and Assessment Authority review to mitigate any ‘deficiencies in knowledge’. Deficiencies were identified in Defence’s implementation of the peer review process and Defence does not undertake assurance activities to monitor the extent to which training is completed. The absence of a formalised training approach to support the implementation of DSPF requirements for the assessment and authorisation of ICT systems creates a risk that systems are not being authorised as intended. Defence data on ICT system authorisations shows that 47 per cent of its systems have a status of either ‘Expired’ or ‘No accreditation’, indicating that System Owner obligations in respect to obtaining and maintaining the authorisation of their systems are not being met.

2.74 Specific training requirements in relation to ICT system assessment and authorisation have not been established in the DSPF. Prior to the DSPF being introduced in July 2018, the Defence Security Manual (DSM) required that Security Assessment Authorities and Authorising Officers, as well as external service providers engaged to perform assessment and authorisation activities, successfully complete an approved course of training.60

2.75 Specific system authorisation training requirements have been established by Army. High-level training requirements have also been established by Navy.61 Deputy Chief of Army Directive 01/20 Army ICT Security Plan (see paragraphs 2.27–2.30) requires that Information Technology Security Managers (ITSMs) and Information Technology Security Officers (ITSOs)62 complete courses including: cyber security awareness63; ICT certification and accreditation; and an ITSO/ITSM course.

Information Technology Security Officer/Manager course

2.76 The ITSO/ITSM course includes assessment and authorisation content such as: roles and responsibilities throughout the assessment and authorisation process; Army’s assurance arrangements, which include assessing the authorisation status of systems (see paragraphs 3.33–3.34); and stipulating that changes to an ICT system may require re-authorisation.64

2.77 Defence advised the ANAO in February 2024 that: