Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Management of Contracts for the Supply of Munitions — Part 1

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The implementation of a Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance (GWEO) enterprise was announced as a key government priority in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review, and the domestic manufacture of GWEO and munitions was one of seven Sovereign Defence Industrial Priorities announced by the Australian Government in the Defence Industry Development Strategy in April 2024.

- This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s establishment of a 10-year agreement with Thales from July 2020 for the continued management and operation of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities. It builds on previous ANAO work examining Defence’s management of the facilities over time.

Key facts

- The Mulwala and Benalla facilities are Commonwealth-owned and have been operated by a third party (Thales Australia) since 1999.

- The current contract, the Strategic Domestic Munitions Manufacturing (SDMM) contract, replaced a five-year interim contract, which was established after a competitive process was terminated in 2014.

What did we find?

- Defence’s conduct of the sole source procurement for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020 was partly effective.

- Defence’s planning for the operation and maintenance of the facilities beyond the expiry of the 2015–20 interim contract was partly effective.

- Defence’s conduct of the sole source procurement process to establish the 2020–30 contractual arrangements was partly effective.

- Defence’s management of probity was not effective and there was evidence of unethical conduct.

What did we recommend?

- There were eight recommendations to Defence aimed at improving: procurement planning; advice to decision-makers; management of probity risks and issues; compliance with record keeping requirements; and traceability of negotiation directions and outcomes.

- Defence agreed to the eight recommendations.

$1.2 bn

contract price (GST exclusive) at 31 March 2024.

$108 m

value (GST inclusive) of reported contract variations (relating to survey and quote work orders) at 19 June 2024.

$225 m

minimum munitions order value (GST exclusive) under the contract.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Mulwala facility in New South Wales is the sole remaining manufacturing site of military propellants and high explosives in Australia. The nearby munitions facility at Benalla, Victoria, uses some of the output of the Mulwala facility in its operations. Both facilities are owned by the Commonwealth and operated by a third party, Australian Munitions, a wholly owned subsidiary of Thales Australia (Thales).1 Thales has managed and operated the facilities at Benalla and Mulwala under several different contractual arrangements since 1999 (outlined in Appendix 3).

2. The Australian Government announced on 29 June 2020 that the Department of Defence (Defence) had signed a new 10-year agreement valued at $1.2 billion with Thales for the continued management and operation of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities.2 The agreement was intended to provide surety of supply of key munitions and components for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and maintain a domestic munitions manufacturing capability. The agreement took effect on 1 July 2020 and resulted from a complex multi-year sole source procurement begun in 2016. The sole source procurement followed a terminated competitive procurement process undertaken between 2009 and 2014.

3. The Australian Government also announced on 29 June 2020 a new contract between the Commonwealth and NIOA Munitions (NIOA) for a tenancy at the Benalla munitions factory.3 This agreement was to establish NIOA as a tenant alongside Thales and provide opportunities for domestic manufacturing while enhancing supplies of key munitions for Defence.4

4. On 24 April 2023, the Australian Government released a public version of the final report of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR).5 It referenced the continuing importance of advanced munitions manufacturing, stating that the immediate focus must be on consolidating ADF guided weapons and explosive ordnance (GWEO) needs, establishing a domestic manufacturing capability, and the acceleration of foreign military and commercial sales. The report further outlined that, to do this, the ADF must hold sufficient stocks of GWEO and have the ability to manufacture certain lines, with the realisation of a GWEO enterprise being ‘central to achieving this objective.’6

5. At 19 June 2024, the implementation of a GWEO enterprise remains a key government priority, with the domestic manufacture of GWEO and munitions in Australia included: as one of seven ‘Sovereign Defence Industrial Priorities’ in the Defence Industry Development Strategy (announced in February 2024)7; and as part of the ‘immediate priorities’ set out in the public versions of the 2024 Integrated Investment Program (IIP) and the 2024 National Defence Strategy (both announced on 17 April 2024).8

6. On 5 May 2023, the Minister for Defence Industry announced the appointment of a senior responsible officer with responsibility for a Defence GWEO enterprise.9 At June 2024, Defence’s website stated that the facilities at Mulwala and Benalla ‘are key assets within the GWEO enterprise and will play a role in the expansion of domestic GWEO manufacturing.’10

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. To establish the arrangements for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020, Defence undertook a complex and lengthy procurement process that was based on a sole source approach. This audit examined whether this process was effective and in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

8. This audit builds on previous work by the ANAO which has examined Defence’s management of the Benalla and Mulwala facilities over time, and provides independent assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s establishment of arrangements for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020.

Audit objective and criteria

9. The audit objective was to assess whether the arrangements for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020 were established through appropriate processes and in accordance with the CPRs.

10. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were selected:

- Did Defence plan effectively for the operation and maintenance of the facilities beyond the expiry of the 2015–20 interim contract?

- Did Defence conduct an effective sole source procurement process to establish the 2020–30 contractual arrangements?

- Did Defence effectively manage probity throughout the process?

11. This report is the first of two performance audit reports examining Defence’s establishment and management of the facilities beyond June 2020. It focuses on Defence’s establishment of the 2020–30 operating arrangements, including the tender assessment process, advice to decision makers and the decision to conduct a sole source procurement. Defence’s management of performance against the contract is the focus of a second report, which will be presented for tabling later in 2024.

Conclusion

12. Defence’s conduct of the sole source procurement for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020 was partly effective. Defence’s management of probity was not effective and there was evidence of unethical conduct.

13. Defence’s planning processes prior to the expiry of the 2015 interim contract were partly effective. While options for the management of the facilities beyond June 2020 were developed, deficiencies were identified in Defence’s subsequent procurement and probity planning processes and in its advice to decision-makers. Defence’s decision to conduct a sole sourced procurement was not informed by an estimated value of the procurement prior to this decision and Defence did not document the legal basis for selecting a sole sourced procurement approach, as required by the CPRs. Probity risks were realised in 2016 when Defence personnel provided Thales with confidential information relating to its Investment Committee (IC) proposal, and advice to decision-makers did not address how value for money would be achieved and commercial leverage maintained in the context of a sole source procurement.

14. Defence’s conduct of the sole source procurement process to establish the 2020–30 contractual arrangements was partly effective. Risk assessments were not timely and appropriate records for key meetings with Thales during the tender process were not developed or retained by Defence. After assessing Thales’ tender response as not being value for money in October 2019, Defence proceeded to contract negotiations in December 2019 notwithstanding internal advice that Defence was at a disadvantage in such negotiations due to timing pressures.

15. The negotiated outcomes were not fully consistent with Defence’s objectives and success criteria. Defence’s approach to negotiating the contract in accordance with high-level issues reduced the line of sight between the request for tender (RFT) requirements and the negotiated outcomes. Defence’s advice to ministers on the tender and contract negotiations did not inform them of the extent of tender non-compliance, basis of the decision to proceed to negotiations, or ‘very high risk’ nature of the negotiation schedule.

16. Defence did not establish appropriate probity arrangements in a timely manner. A procurement-specific probity framework to manage risks associated with the high level of interaction between Defence and Thales was not put in place until July 2018. Probity risks arose and were realised during 2016 and 2017, including when a Defence official solicited a bottle of champagne from a Thales representative. Defence did not maintain records relating to probity management and could not demonstrate that required briefings on probity and other legal requirements were delivered.

Supporting findings

Planning during the interim contract period

Options development and consideration of facilities management beyond June 2020

17. Defence provided advice to the Minister for Defence during 2014 on a range of options for the management of the facilities beyond June 2020, including: continuing with the status quo; the Commonwealth operating the facilities; and closing the facilities. These options continued to be considered by Defence and the government between 2015 and mid-2017. In 2016, a clear preference emerged to sole source the operation and maintenance of the facilities to the incumbent, Thales. By July 2016, Defence was primarily focused on developing a proposed ‘strategic partnership’ arrangement with Thales. Defence did not document the legal basis (that is, an exemption provided by paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs) for the proposed sole source activity to inform its subsequent procurement planning (see paragraphs 2.1 to 2.51).

18. A procurement-specific probity framework was not put in place until July 2018, to help manage probity risks in the context of pursuing a strategic partnership arrangement with Thales. These risks crystallised during 2016 when:

- senior Defence personnel advised Thales at an October 2016 summit meeting that Defence’s preference would be to progress a government-owned contractor-operated arrangement with Thales into the future.

- a Defence official sought assistance from and provided information to Thales in November 2016 on the development of internal advice to the IC, Defence’s committee processes, and internal Defence thinking and positioning. Government information of this sort is normally considered confidential, and the relevant email exchange evidenced unethical conduct (see paragraphs 2.48 to 2.51).

Advice and analysis informing the decision to conduct a sole source process with the incumbent operator

19. Defence’s advice to the IC in December 2016 and the Minister for Defence Industry in mid-2017 on the decision to sole source was not complete. The advice did not address the legal basis for the procurement method, the risks associated with a sole source procurement approach, or value for money issues — including how Defence expected to achieve value for money and maintain commercial leverage in the context of a sole source procurement. When the IC approved the sole source procurement method in December 2016, Defence had not estimated the value of the procurement. This was not consistent with the CPR requirement to estimate the value of a procurement before a decision on the procurement method is made (see paragraphs 2.52 to 2.71).

Establishment of the 2020–30 arrangements

Procurement planning activities

20. Defence’s procurement planning activities were not timely. Prior to mid-2017, Defence’s planning had largely focussed on seeking approval by June 2017 to inform Thales of the arrangements for the facilities beyond June 2020 (as required of Defence under the interim contract) and to enable collaborative contract development with Thales to commence. Defence’s advice to decision-makers was not informed by the results of key planning processes, as required by the CPRs and Defence’s procurement policy framework. These key processes were not conducted until after December 2016, when the sole source procurement method was approved and included:

- the progressive development of Defence’s requirements for the facilities between March 2017 and July 2019, with assistance from Thales; and

- internal workshops between October 2017 and May 2018, which identified risks that had not been previously documented. Defence did not develop a risk management plan to actively manage those risks (see paragraphs 3.1 to 3.31).

Development of the request for tender

21. Defence undertook a process which included the principal elements of a complex procurement as set out in Defence’s procurement policy framework, including an Endorsement to Proceed (EtP), RFT process and detailed contract negotiations. A feature of Defence’s process was the high level of interaction with Thales on the contents of the RFT before and after it was issued on 16 August 2019, including during the tender response period. Defence’s Complex Procurement Guide (CPG) identified ‘probity risks inherent in such activities’ and stated that relevant engagement processes and activities ‘should be planned and conducted with appropriate specialist support.’ Seeking specialist advice on the propriety and defensibility of its approach would have been prudent and consistent with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) duty that officials exercise care and diligence (see paragraphs 3.32 to 3.63).

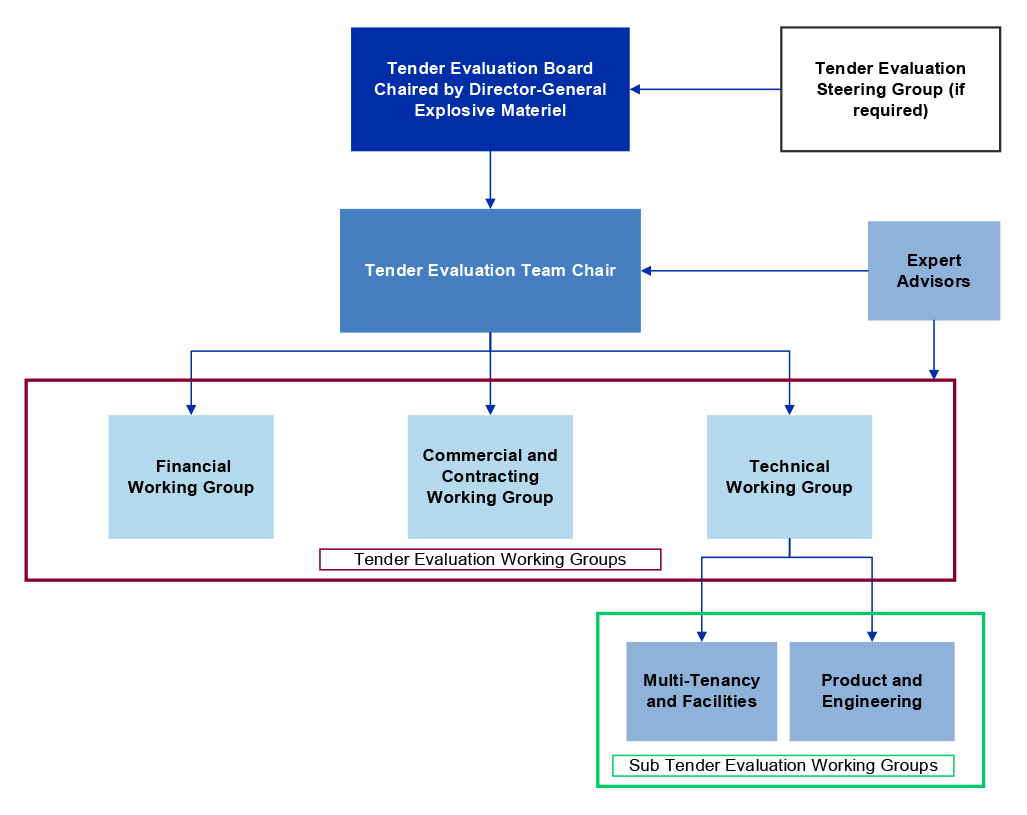

Tender evaluation

22. By October 2019, Defence had determined that Thales’ tender response was not value for money due to assessing the proposal as ‘Deficient – Significant’ with ‘High’ risk against all five evaluation criteria and identifying 199 non-compliances against the RFT. Defence considered the number of non-compliances to be ‘unprecedented’ and initially agreed, internally, to extend the interim contract with Thales to allow sufficient time to negotiate the non-compliances with the RFT (see paragraphs 3.64 to 3.78).

23. Following senior-level discussions in November 2019 with Thales, Defence decided to conclude the evaluation process on 4 December 2019 and proceed to contract negotiations. This decision was made notwithstanding internal advice that Defence was at a disadvantage in negotiations due to timing pressures. Defence’s internal advice considered that it had no ‘off-ramps’ due to the impending expiry of the interim contract on 30 June 2020. Defence did not clearly document the basis for reducing risk ratings against all the evaluation criteria from ‘High’ to ‘Medium’, following the senior-level discussions with Thales (see paragraphs 3.79 to 3.90).

24. Defence did not prepare or retain appropriate records for key meetings with Thales during the tender where the identified risks required active Defence management in the Commonwealth interest. Defence’s approach to record keeping was not consistent with requirements in the relevant Communications Plan, internal procurement advice, guidance in the CPG, or the CPRs (see paragraphs 3.91 to 3.100).

Negotiation outcomes

25. The negotiated outcomes for the 2020–30 contract were not fully consistent with Defence’s objectives and success criteria approved by Defence in July 2019. At the conclusion of negotiations in February 2020, three of the 15 success criteria aimed at incentivising satisfactory performance and reducing the contract management burden and total cost of ownership for the facilities were reported as not achieved. Defence’s approach to negotiations involved agreeing a schedule and high-level negotiation issues with Thales, to guide negotiations between December 2019 and February 2020. Defence did not systematically address the 199 non-compliances it had identified in Thales’ tender response. This approach reduced the traceability between the RFT requirements, risks and issues identified during tender assessment, and the negotiated outcomes in the agreed contract (see paragraphs 3.101 to 3.114).

26. Defence’s advice to its ministers on the tender and 2020–30 contract negotiations did not inform them of key issues such as the extent of tender non-compliance, the basis of the decision to proceed to negotiations, and Defence’s assessment of the ‘very high risk’ nature of the negotiation schedule (see paragraphs 3.115 to 3.133).

Probity management

Establishment of probity arrangements

27. Defence did not establish appropriate probity arrangements in a timely manner. Defence did not have project and procurement-specific probity arrangements in place until July 2018, more than two years after its initial engagement with Thales (in March 2016) about future domestic munitions manufacturing arrangements. Prior to establishing these probity arrangements, Defence did not assess or take steps to manage potential probity risks arising from ongoing direct engagement with the incumbent operator or remind those involved of their probity obligations, including in relation to offers of gifts and hospitality. During this period, probity risks were realised and there was evidence of unethical conduct, including when a Defence official solicited a bottle of champagne from a Thales representative (see paragraphs 4.1 to 4.30).

28. While Defence’s CPG identified ‘inherent’ probity risks in ‘any procurement that involves high levels of tenderer interaction’ Defence did not appoint a probity adviser that was external to the department. Defence maintained a register of probity documentation but did not retain relevant records for one of the 65 personnel recorded as having completed documentation. For 22 (25 per cent) of the 87 personnel who completed probity documentation, this completion was not recorded in any register. There was no relevant probity documentation for a further six individuals involved for a period in the procurement. Defence’s conflict of interest (COI) register for the procurement was also incomplete. It did not record six instances where a Defence official or contractor declared a potential, perceived or actual COI, including a Tender Evaluation Board member’s declaration of long-term social relationships with Thales staff. Defence was unable to provide evidence that briefings on probity and other legal requirements were delivered in accordance with the Legal Process and Probity Plan for the procurement (see paragraphs 4.31 to 4.50).

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.31

The Department of Defence document at the time the proposed procurement activities are decided:

- the circumstances and conditions justifying the proposed sole source approach, to inform subsequent procurement planning; and

- which exemption in the CPRs is being relied upon as the basis for the approach and how the procurement would represent value for money in the circumstances.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.61

The Department of Defence, including its relevant governance committees, ensure that when planning procurements, the department estimates the maximum value (including GST) of the proposed contract, including options, extensions, renewals or other mechanisms that may be executed over the life of the contract, before a decision on the procurement method is made.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.64

The Department of Defence, including its relevant governance committees, ensure that advice to decision-makers on complex procurements is informed by timely risk assessment processes that are commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the relevant procurement.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.61

The Department of Defence ensure that when it undertakes complex procurements with high levels of tenderer interaction, it seeks appropriate specialist advice, including from the Department of Finance as necessary.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.94

The Department of Defence ensure compliance with the Defence Records Management Policy and statutory record keeping requirements over the life of the 2020–30 Strategic Domestic Manufacturing contract, including capturing the rationale for key decisions, maintaining records, and ensuring that records remain accessible over time.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.112

The Department of Defence ensure, for complex procurements, that there is traceability between request for tender (RFT) requirements, the risks and issues identified during the tender assessment process, and the negotiated outcomes.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.10

The Department of Defence develop procurement-specific probity advice for complex procurements at the time that procurement planning begins and develop probity guidance for:

- complex procurements involving high levels of tenderer interaction; and

- managing engagement risks in the context of long-term strategic partnership arrangements.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.25

The Department of Defence make appointment of external probity advisers mandatory for all complex procurements with high probity risks, such as procurements with high levels of tenderer interaction.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

29. The proposed audit report was provided to Defence. Defence’s summary response is reproduced below. The full response from Defence is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Department of Defence

Defence acknowledges the findings contained in the audit report on Defence’s Management of Contracts for the Supply of Munitions, which assessed the effectiveness of the procurement and contract establishment for the Department’s Strategic Domestic Munitions Manufacturing contracting arrangement.

The Mulwala and Benalla munition factories underpin Australia’s ability to develop critical propellants, explosives and munitions for the Australian Defence Force and are recognised as a world-class capability. Since this procurement activity, the strategic landscape has changed, as outlined in the Defence Strategic Update of 2020 and the Defence Strategic Review in 2023. The National Defence Strategy further prioritises these factories as critical and foundational industrial capabilities for Australian domestic manufacturing, supporting sovereign resilience and our allies.

Defence welcomes collaborative engagement with our industry partners in delivering unique capability outcomes. Defence acknowledges and understands the need to ensure that such engagement is appropriately managed, and will strengthen the guidance in relation to identifying and managing procurement and probity risks early in the process as well as maintaining these records for the life of the procurement activity. Defence is continually improving and updating the Defence frameworks that underpin the issues raised.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

30. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Mulwala facility in New South Wales is the sole remaining manufacturing site of military propellants and high explosives in Australia. The nearby munitions facility at Benalla, Victoria, uses some of the output of the Mulwala facility in its operations. Both facilities are owned by the Commonwealth and operated by a third party, Australian Munitions, a wholly owned subsidiary of Thales Australia (Thales).11 Thales has managed and operated the facilities since 1999.

1.2 The Australian Government announced on 29 June 2020 that the Department of Defence (Defence) had signed a new 10-year agreement valued at $1.2 billion with Thales for the continued management and operation of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities.12 The agreement was intended to provide surety of supply of key munitions and components for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and maintain a domestic munitions manufacturing capability. The agreement took effect on 1 July 2020 and resulted from a complex multi-year sole source procurement begun in 2016 that had followed a terminated competitive procurement process undertaken between 2009 and 2014.

1.3 The Australian Government also announced on 29 June 2020 a new contract between the Commonwealth and NIOA Munitions for a tenancy at the Benalla munitions factory.13 This agreement was to establish NIOA as a tenant alongside Thales Australia and provide opportunities for domestic manufacturing while enhancing supplies of key munitions for Defence.14

Defence industry policies

1.4 The Australian Government’s defence industry policies have referenced the importance of a domestic munitions manufacturing capability to support the ADF since the release of the 2009 Defence White Paper in May 2009.15

1.5 On 24 April 2023, the Australian Government released a public version of the final report of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR).16 It referenced the continuing importance of advanced munitions manufacturing, stating that the immediate focus must be on consolidating ADF guided weapons and explosive ordnance (GWEO) needs, establishing a domestic manufacturing capability, and the acceleration of foreign military and commercial sales. The report further outlined that, to do this, the ADF must hold sufficient stocks of GWEO and have the ability to manufacture certain lines, with the realisation of a GWEO enterprise being ‘central to achieving this objective.’17

1.6 At June 2024, the implementation of a GWEO enterprise remains a key government priority, with the domestic manufacture of GWEO and munitions in Australia included: as one of seven ‘Sovereign Defence Industrial Priorities’ in the Defence Industry Development Strategy (announced in February 2024)18; and as part of the ‘immediate priorities’ set out in the public versions of the 2024 Integrated Investment Program (IIP) and the 2024 National Defence Strategy (both announced on 17 April 2024).19

Defence’s administrative arrangements

1.7 On 5 May 2023, the Minister for Defence Industry announced the appointment of a senior responsible officer with responsibility for a Defence GWEO enterprise.20 At 19 June 2024, Defence’s website stated that the facilities at Mulwala and Benalla ‘are key assets within the GWEO enterprise and will play a role in the expansion of domestic GWEO manufacturing.’21

1.8 Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) held primary responsibility for overseeing contractor management of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities from the time of CASG’s establishment in 2015 until May 2023, when Defence established the GWEO Group. The Chief of Joint Capabilities was designated as the Capability Manager in July 2018, as part of Defence’s implementation of the ‘One Defence’ Capability Policy Framework.22 In May 2023, the Chief of GWEO assumed the Capability Manager role.

1.9 At 7 June 2024, the GWEO Group consisted of two divisions — the GWEO Systems Division and GWEO Manufacturing Division. The Industrial Delivery Branch within the GWEO Manufacturing Division is responsible for the provision of contracted support for the operation and maintenance of the Benalla and Mulwala facilities. The contract is managed day-to-day by the Strategic Domestic Munitions Manufacturing team based in Penrith, New South Wales.

Contracting arrangements

1.10 Thales has managed and operated the facilities at Benalla and Mulwala under several different contractual arrangements since 1999 (outlined in Appendix 3). The arrangements examined as part of this audit are outlined below at paragraphs 1.11 to 1.17.

Domestic Munitions Manufacturing Arrangements project (2009–14)

1.11 Defence established the Domestic Munitions Manufacturing Arrangements (DMMA) project in December 2009 to determine successor arrangements to the 1998–2015 agreements.23 The project scope and competitive procurement methodology were approved by government in June 2012. The DMMA procurement process was suspended in January 2014 in response to a November 2013 Defence Gate Review recommendation24, and pending direction from the Australian Government on the long-term future of the facilities.25 The DMMA procurement process was terminated in September 2014.

2015–20 Strategic Munitions Interim Contract

1.12 In November 2014, Defence entered into the 2015–2020 Strategic Munitions Interim Contract (SMIC, or 2015 interim contract) with Thales through a sole source process. The interim contract was for a period of five years commencing on 1 July 2015.

1.13 Auditor-General Report No. 26 2015–16 Defence’s Management of the Mulwala Propellant Factory noted that there would be significant merit in another approach to market to replace the 2015 interim contract. The report included two recommendations that were agreed by Defence. Recommendation 1 was:

To achieve better value from the significant investment in a domestic munitions capability to date, by the end of 2016, Defence:

- advise the Government on options for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla Facilities from June 2020; and

- develop a plan for the timely and cost-effective implementation of the Government’s preferred option.26

1.14 Consistent with advice received from Defence in mid-2017, the Minister for Defence Industry announced on 6 February 2018 that Defence would enter into direct negotiations with Thales to establish a ‘new strategic arrangement for the management and operation of the factories, improving price competitiveness and increasing export potential for Australian-manufactured ammunition and explosive products.’27

2020–30 Strategic Domestic Munitions Manufacturing contract

1.15 The new strategic arrangement involved a sole source procurement and was implemented through the SDMM contract which took effect on 1 July 2020. A timeline of the procurement process is set out in Appendix 4.

1.16 The SDMM contract is comprised of leases between Defence and Thales for all of the Mulwala facility, part of the Benalla facility, certain surrounding pastoral lands, and an agreement to provide services and supplies (see Table 1.1 below).28 At June 2024, there were 54 types of munitions listed within the contract that are able to be supplied to Defence.

1.17 A point of difference from the previous contractual arrangements is Thales’ role as the Commonwealth’s ‘strategic partner’ under the SDMM contract. Thales is required to ‘share information in a transparent manner about future Contractor investment opportunities under consideration at the Facilities [Mulwala and Benalla]’ and ‘work collaboratively with the Commonwealth to enable investment opportunities to align with Best for Defence, the Contract Objectives and to provide mutual benefits to the Parties.’

Value of SDMM contract

1.18 At 19 June 2024, the SDMM contract had a reported value of $1,369 million (GST inclusive) on Austender. This was an increase of $108 million (8.5 per cent), due to the inclusion of survey and quote work orders, compared to the original reported value of $1,261 million (GST inclusive).29

1.19 Key components of the SDMM contract price as set out in the contract — which were GST exclusive figures — at 31 March 2024, are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Components of the SDMM contract price at 31 March 2024

|

Price component |

Total component price (GST exclusive) ($AUD millions)d |

|

Facilities operations paymenta |

913.8 |

|

Minimum order valueb |

225.0 |

|

Survey and quotec |

103.9 |

|

Total |

1242.7 |

Note a: The facilities operations payment includes the facilities operating cost, utilities pass through costs, facilities operating payment contingency, general and administrative costs, Thales corporate fee, and Thales’ profit margin. At contract signature, Thales and Defence agreed the facilities operation payment for the first two years of the contract, with the remaining eight years of the initial 10-year term estimated by escalating the agreed amount. The facilities operations payment component of the contract price has decreased from $921.4 million as a result of a periodic cost review undertaken between October 2021 and May 2022. These reviews set the price at regular intervals during the contract term, taking escalation and cost efficiencies into account.

Note b: The minimum order value reflects the agreed minimum order value of $25 million per year for Years 1–5 and $20 million per year for Years 6–10. Accordingly, it does not include the value of munitions orders placed by Defence in excess of the minimum order value.

Note c: The survey and quote value reflects all price-impacting survey and quote work orders, excluding those related to munitions orders, approved by Defence at 31 March 2024.

Note d: The original total contract price was $1,146,388,000 million (GST exclusive).

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

1.20 In addition to the facilities operation payment and munitions orders (outlined in Table 1.1), Thales receives payments for undertaking other work approved by Defence under five survey and quote provisions in the contract. These provisions are covered by a separate pricing structure. The five categories of survey and quote provisions are: munitions supply services; capital works services; research and development services; pass-through cost services; and miscellaneous services.

Funding arrangements and expenditure against the SDMM contract

1.21 The facilities operations payment is funded under Product Delivery Schedule CJC01/Integrated Product Management Plan GWEO01 (CJC01/GWEO01), with survey and quote services being funding from various funding sources.30 Munitions supply survey and quote services are funded through the individual military Services’ (Army, Navy or Air Force) sustainment or acquisition budgets, while all other survey and quote services are predominately funded under CJC01/GWEO01 and acquisition budgets.

1.22 CJC01/GWEO01 actual expenditure from 1 July 2020 to 31 December 2023 was $469.6 million, with:

- $399.7 million spent on the SDMM contract at 31 December 2023; and

- $69.9 million spent on activities related to multi-tenancy, facility maintenance, major works and ‘engineering & branch support’.

1.23 Allocated funding to 30 June 2030, and actual expenditure at 31 December 2023, under CJC01/GWEO01 on the SDMM contract and associated capability costs are outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Allocated funding and actual expenditure — 1 July 2020 to 31 December 2023

|

Funding source |

Allocated funding to 30 June 2030 (at 31 December 2023) ($AUD) |

Expenditure at 31 December 2023 ($AUD) |

Percentage of funding expended (%) |

|

CJC01/GWEO01 |

1,013,527,000 |

469,603,028 |

46.3 |

|

CA59: Explosive Ordnance — Army Munitions Brancha |

198,000,000 |

130,430,719 |

66.8 |

|

JP2092 Phase 1 GWEO Enterprise |

184,900,000 |

14,286,733 |

0.1 |

|

CAF33 — Air Force Guided Weaponsb |

38,500,000 |

11,557,054 |

30.0 |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 3c |

11,000,000 |

11,742,929 |

106.8 |

|

Total |

1,445,927,000 |

637,620,463 |

44.1 |

Note a: ‘CA’ here stands for Chief of Army, as the Capability Manager for this Army sustainment product.

Note b: ‘CAF’ here stands for Chief of Air Force, as the Capability Manager for this Air Force sustainment product.

Note c: AIR 6000 Phase 3 is a Defence project to acquire new weapons and countermeasures for the F-35A Joint Strike Fighters and F/A-18F Super Hornets in service with the Royal Australian Air Force.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

Previous Auditor-General reports

1.24 Aspects of Defence’s management of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities were examined by the ANAO in the following performance audits.

- Auditor-General Report No. 40 2005–06 Procurement of Explosive Ordnance for the Australian Defence Force (Army).

- Auditor-General Report No. 24 2009–10 Procurement of Explosive Ordnance for the Australian Defence Force.

- Auditor-General Report No. 26 2015–16 Defence’s Management of the Mulwala Propellant Factory.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.25 To establish the arrangements for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020, Defence undertook a complex and lengthy procurement process that was based on a sole source approach. This audit examined whether this process was effective and in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

1.26 This audit builds on previous work by the ANAO which has examined Defence’s management of the Benalla and Mulwala facilities over time, and provides independent assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s establishment of the arrangements for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities beyond June 2020.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.27 The audit objective was to assess whether the arrangements for the operation and maintenance of the Mulwala and Benalla facilities from July 2020 were established through appropriate processes and in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

1.28 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were selected:

- Did Defence plan effectively for the operation and maintenance of the facilities beyond the expiry of the 2015–20 interim contract?

- Did Defence conduct an effective sole source procurement process to establish the 2020–30 contractual arrangements?

- Did Defence effectively manage probity throughout the process?

1.29 This report is the first of two performance audit reports examining Defence’s establishment and management of the facilities beyond June 2020. It focuses on Defence’s establishment of the 2020–30 operating arrangements, including the tender assessment process, advice to decision makers and the decision to conduct a sole source procurement. Defence’s management of performance against the contract is the focus of a second report, which will be presented for tabling later in 2024.

Audit methodology

1.30 The audit procedures included:

- reviewing Defence records, including procurement planning, tender assessments, advice to decision-makers, and contract management documentation;

- meetings with Defence officials and Defence contractors; and

- walkthroughs of Defence systems.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $497,453.

1.32 The team members for this audit were James Woodward, Adam Reddiex, Jay Banpel, Jude Lynch, Raveen Spindary, and Amy Willmott.

2. Planning during the interim contract period

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence (Defence) planned effectively for the operation and maintenance of the Benalla and Mulwala facilities beyond the expiry of the 2015–2020 interim contract.

Conclusion

Defence’s planning processes prior to the expiry of the 2015 interim contract were partly effective. While options for the management of the facilities beyond June 2020 were developed, deficiencies were identified in Defence’s subsequent procurement and probity planning processes and its advice to decision-makers.

Defence’s decision to conduct a sole sourced procurement was not informed by an estimated value of the procurement prior to this decision and Defence did not document the legal basis for selecting a sole sourced procurement approach, as required by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). Probity risks were realised in 2016 when Defence personnel provided Thales with confidential information relating to its Investment Committee (IC) proposal, and advice to decision-makers did not address how value for money would be achieved and commercial leverage maintained in the context of a sole source procurement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving Defence’s procurement planning and advice to decision-makers.

2.1 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) state that procurement begins when a need has been identified and a decision has been made on the procurement requirement.31 Procurement continues through the processes of risk assessment, seeking and evaluating alternative solutions, and the awarding and reporting of a contract.

Were options for the management of the facilities beyond June 2020 appropriately developed and considered?

Defence provided advice to the Minister for Defence during 2014 on a range of options for the management of the facilities beyond June 2020, including: continuing with the status quo; the Commonwealth operating the facilities; and closing the facilities. These options continued to be considered by Defence and the government between 2015 and mid-2017. In 2016, a clear preference emerged to sole source the operation and maintenance of the facilities to the incumbent, Thales. By July 2016, Defence was primarily focused on developing a proposed ‘strategic partnership’ arrangement with Thales. Defence did not document the legal basis (that is, an exemption provided by paragraph 2.6 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules) for the proposed sole source activity to inform its subsequent procurement planning.

A procurement-specific probity framework was not put in place until July 2018, to help manage probity risks in the context of pursuing a partnership arrangement with Thales. Probity risks crystallised during 2016 when:

- senior Defence personnel advised Thales at an October 2016 summit meeting that Defence’s preference would be to progress a government-owned contractor-operated arrangement with Thales into the future.

- a Defence official sought assistance from and provided information to Thales in November 2016 on the development of internal advice to the IC, Defence’s committee processes, and internal Defence thinking and positioning. Government information of this sort is normally considered confidential, and the relevant email exchange evidenced unethical conduct.

Domestic Munitions Manufacturing Arrangements project

2.2 From July 1998 to June 2015, the production of propellant and high explosives at the Mulwala facility, and the production and sale of munitions from the Benalla facility, were governed by the Mulwala Agreement and the Strategic Agreement for Munitions Supply (SAMS). Defence undertook extensive work as part of its Domestic Munitions Manufacturing Arrangements (DMMA) Project between 2009 and 2014 to determine successor arrangements to the 1998–2015 agreements (see Appendix 3).32

2.3 After suspending the DMMA procurement process in January 2014, Defence entered into the 2015–2020 Strategic Munitions Interim Contract (SMIC, or 2015 interim contract) with Thales through a sole source process in November 2014. The interim contract was for five years commencing on 1 July 2015.

2.4 The DMMA project work included commissioning two studies in 2011–12 to examine the global munitions market (undertaken by the RAND Corporation) and the regional economic contribution of the Benalla and Mulwala facilities (undertaken by KPMG).33 These studies informed Defence’s approach in establishing the new 10-year Strategic Domestic Munitions Manufacturing (SDMM) arrangements from July 2020 and were drawn on in Defence advice to responsible ministers for several years thereafter. The RAND Corporation study (RAND review) observed the following.

- ‘If maintaining a domestic munitions industry is desirable, using the full production capacity at Benalla is the key to controlling costs’.

- ‘Increased production at Benalla would lower the overall cost per unit of munitions output as subsidised labour is shifted to production and production costs decrease due to efficiencies tied to volume’.

- ‘By aligning investment with ADF demand, the CoA [Commonwealth of Australia] can increase production at Benalla and Mulwala (which would increase sales at Benalla), minimising the size of the subsidised labour pool.’34

2.5 The DMMA procurement methodology was approved by government in June 2012. The procurement was to involve a two-stage process comprising a request for proposal (RFP) process followed by a request for tender (RFT) process. The RFP was issued to six companies on 28 November 2012 and closed on 25 March 2013.35

2.6 Evaluations of the RFP responses were finalised on 19 July 2013, with three respondents recommended to proceed to the RFT stage. Of those three, Thales was the third-ranked respondent. Defence’s evaluation found that on a number of parameters, Thales’ proposal was not as competitive as the other shortlisted respondents. Defence’s evaluation records stated that Thales’ proposal involved ‘significantly higher risk to the Commonwealth’ and required significantly more capital investment than the two other proposals (indicating a ‘significant reliance on ongoing Commonwealth support’).

DMMA suspension and the 2015 interim contract arrangements

2.7 The DMMA RFT was not released in December 2013 as planned and the process was suspended in January 2014, in response to a November 2013 Defence Gate Review recommendation and decisions by the Australian Government on the long-term future of the facilities. The Gate Review had concluded that the DMMA RFT was not ready to be released and recommended that alternative options, including reshaping of the DMMA project, be developed and provided for government consideration as a priority.36

2.8 In March 2014, the DMMA Project Director issued a probity guidance note to the DMMA project team, which outlined that the delays to the project had required interim arrangements to be established with Thales ‘in order to deal with the potential gap between the end of the current arrangements (30 June 2015) and the commencement of the new arrangement’. The guidance note further stated that ‘[s]ome personnel who have been involved in conducting the DMMA process will be assisting in these additional activities.’ The guidance note contained two attachments. The first, titled ‘Responsibility Areas’, set out the probity principles for the ‘additional activities’. The second, titled ‘Other Matters to be Conscious of (Specifically for Individuals Engaging with Thales)’, included the following ‘matters’ (and related guidance).

- ‘Ensure the continued provision of a level playing field to all tenderers’.37

- ‘Ensure that interactions with Thales in the course of dealing with these matters are appropriate and consistent with a resumption of the DMMA RFT’.38

- ‘Enable Defence to release (to the fullest extent possible, but subject to appropriate confidentiality obligations to Thales) updated information from Thales in respect of the facilities and their condition to other tenderers’.

- ‘Avoid vendor lock in’.39

2.9 Between January and August 2014, Defence continued to provide advice to government, including seeking direction from the Minister for Defence regarding the future of the facilities.40 Defence’s advice examined future options and cost estimates for the sites, which were: close and potentially sell the facilities; recommence the DMMA process; or establish a direct source medium term performance-based arrangement for operation of the facilities, most likely with Thales.

2.10 At a meeting on 25 June 2014, the minister requested that Defence prepare a further submission to inform government, notionally in late 2014, regarding the long-term future of domestic munitions manufacture. The minister also requested that a submission detailing interim arrangements for the short-term operation of the facilities be prepared for the minister’s consideration.41

2.11 On 28 August 2014, Defence advised the minister that it expected to enter into the interim arrangements in October 2014, pending successful negotiations with Thales, and that it intended to bring forward a submission for government consideration by the end of 2014 for a decision on the long-term arrangements for the facilities. Defence advised the minister that a decision any later than 30 June 2017 on the long-term arrangements would pose ‘considerable schedule challenges’ for the conduct of another competitive tender process or disposal of the facilities as a ‘going concern’ by June 2020.

2.12 On 1 September 2014, the minister wrote to the Prime Minister advising that the DMMA process had been suspended in January 2014 and ‘a business case around the most appropriate mechanisms to manage ADF munitions purchase’ would be brought forward for government consideration in 2016. The minister’s letter stated there were three broad options for the future of the sites — closing the sites and acquiring ADF munitions on the global market, recommencing the suspended DMMA process, or a direct source medium term arrangement with Thales.42

2.13 On 8 September 2014, the minister noted Defence’s advice of 28 August 2014 and approved ‘Defence entering into interim arrangements for ongoing operation of the Benalla and Mulwala facilities with the incumbent contractor, Thales Australia, for a period of up to 5 years’. There is no evidence that a business case was brought forward in 2016 for the government’s consideration, as advised in the minister’s 1 September 2014 letter to the Prime Minister nor were the facilities brought forward for any further government consideration between 2016 and July 2020 (when the current SDMM arrangements commenced).

Advice on long-term arrangements for the facilities

2.14 Under the interim arrangements executed in November 2014, Defence was obligated to give Thales written notice on or before 30 June 2017 of any extension to the 2015 interim contract beyond 30 June 2020. Defence’s advice on the long-term arrangements was not progressed until February 2016, after receiving a request for advice from the Minister for Defence.43

2.15 In response to the minister, Defence advised on 19 February 2016 that it would be in a position to ‘provide advice to Government in mid-2017 on options for the future operation of the two factories’. To inform the development of that advice, Defence noted that it intended to ‘conduct an analysis of the future strategic requirement for the facilities, taking into account recommendations from the 2016 Defence White Paper in relation to domestic manufacturing capabilities’.44

2.16 Defence considered options for the long-term operation of the facilities between March and October 2016. This was consistent with the approach developed by Defence to implement the ANAO recommendations agreed in February 2016 (see paragraph 1.13), which included reviewing the commercial data from the terminated DMMA process and developing a paper for the IC..45 Defence’s planned approach also included advice to government on options to be investigated, followed by further advice outlining Defence’s findings and recommendations.46

2.17 Defence records state that the ANAO recommendations were ‘completed’ in June 2017. As discussed at paragraph 2.13, a submission on the long-term operation of the facilities was not brought forward for consideration by the government between September 2014 and July 2020.

Munitions Manufacturing Integrated Product Team

2.18 In January 2015, Defence established a Munitions Manufacturing Integrated Product Team (IPT) to facilitate collaboration between the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG), Joint Logistics Command (JLC), the ADF Services and Thales ‘for execution of the Government’s directive for the domestic munitions manufacturing’ at the facilities.47 The IPT was to be an advisory body for ADF Capability Managers and a forum for discussion and prioritisation of domestic munitions manufacturing.48

2.19 Consistent with the findings of the RAND review (see paragraph 2.4), the focus of meetings for the first two years was on increasing the use of the facilities by identifying ‘potential candidate munitions for manufacture’ by Thales during the interim contract period. In October 2017, the IPT was expanded to include other companies — NIOA Nominees Pty Ltd (NIOA) and Chemring Australia Pty Ltd — as a source of advice to government on the ‘domestic capabilities of the industrial base’.49 The IPT meetings occurred quarterly on average, until it was replaced in June 2018 by the Explosive Ordnance Manufacturing Review Board.

Development of advice for the Defence Investment Committee

2.20 A gate review of the Mulwala Redevelopment Project conducted in April 2016 found that it was ‘not clear that the necessary underpinning work’ was underway to support advice to government on long term options for the facilities. The reviewers recommended ‘further work be undertaken on contractual options’ for the long term operation of Mulwala to support this advice and address the ANAO recommendation.’ The recommendations were agreed to by Head Joint Systems, CASG (SES Band 2 or two-star equivalent) on 19 April 2016.

2.21 Between early June and August 2016, an issues paper was developed by the Explosive Materiel Branch for consideration by Head Joint Systems. A proposed ‘strategy for the future management of … [the] factories’ was set out in the issues paper and ‘endorsement of the intended course of action’ proposed by the Explosive Material Branch was sought. The paper referenced learnings from the DMMA process and the Mulwala Redevelopment Project and stated that Defence’s options were:

- disposal of the factories by abandonment;

- a government-owned government-operated (GOGO) model;

- a government-owned contractor-operated (GOCO) model; and

- a contractor-owned contracted-operated (COCO) model.

2.22 The paper also stated that an ‘assessment of risks’ would support ‘selecting either the GOCO or COCO option without the need to approach the market’. The risks identified focused on technical, schedule, commercial and financial risks associated with a change of operator, with Defence considering a new arrangement with Thales the lowest risk option for government.

2.23 The recommendations in the issues paper included the following.

- Do not go to market as the market is well understood and the DMMA process provided sufficient information to support decision-making.50

- Retain a GOCO model as the lowest risk option to mitigate immediate environmental clean-up costs and avoid the need to gain/hold a Major Hazard Facility licence.

- Retain Thales as operator of the two sites, as it is a known entity with an existing performance-based contract and experience to operate a Major Hazard Facility.

- Extend commercial SMIC (2015 interim contract) arrangements as they allow for the supply of ammunition to be split from operation of the factories.

- Institute new governance arrangements better suited to strategic management of the factories as a capability, rather than a contract to supply ammunition. In particular, the paper stated that ‘future ownership arrangements should establish a long term strategic partnership between Defence and the operator’ and should ‘emphasise the benefit of mutual respect and cooperation.’

2.24 On 12 July 2016 Head Joint Systems endorsed a sole source procurement approach with Thales and approved further development of this approach for consideration by the IC. Between 12 and 18 July 2016, officials within the Explosive Materiel Branch of CASG’s Joint Systems Division raised the following issues regarding the proposed sole source approach.

- The potential merit in opening the facilities to global suppliers who could leverage their global business to achieve maximum economies of scale and offset low ADF demand.

- That by deciding to sole source to Thales at this stage, Defence had ‘discounted the potential benefits of another operator with a larger munitions business, without truly testing the Course of Action’.

- Insufficient consideration of insights from the cancelled DMMA process.

- That Defence had a better understanding of the facilities to compare operator options that it did not have pre-2015.51

2.25 On 18 July 2016, the Director-General Explosive Materiel (SES Band 1 or one-star equivalent) acknowledged this input, noting however that the endorsed approach was ‘consistent with where the DEPSEC CASG [Deputy Secretary CASG] would want … to take things’ and that ‘it would be high risk (potentially disastrous to go to another operator).’52

Procurement framework matters

2.26 Two documents (a draft Project Execution Strategy and Preliminary Procurement Strategy) were progressively developed between July 2016 and September 2017, in line with the approach endorsed by Head Joint Systems (see paragraph 2.24). The legal basis for the proposed sole source procurement approach was not documented at the time, and this did not occur until August 2018.53

2.27 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules 2014 (CPRs) applied at the time of the sole source procurement decision.54 Under the CPRs, a sole source procurement above the relevant threshold could be undertaken by relying on the following provisions.

- Paragraph 2.6, which provided that:

Nothing in any part of these CPRs prevents an official from applying measures determined by their Accountable Authority to be necessary for the maintenance or restoration of international peace and security, to protect human health, for the protection of essential security interests, or to protect national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value.

- Appendix A, which listed 17 exemptions from the rules in Division 2 of the CPRs regarding competitive processes. Exempt procurements were still required to be undertaken in accordance with value for money requirements.

2.28 These CPR provisions were reflected in the Defence Procurement Policy Manual (DPPM) applying at the time, which stated that the Secretary of Defence had determined, for paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs, that the procurement of goods under Federal Supply Code 13 Ammunition and Explosives and services relating to operation of government-owned facilities was exempt from the operation of Division 2 of the CPRs. Defence subsequently relied on this part of the DPPM to support its decision to exempt the procurement from Division 2 of the CPRs and undertake a sole source procurement.

2.29 The DPPM also stated that ‘if a procurement is exempt from Division 2 of the CPRs, Defence officials are still required to undertake their procurement in accordance with Division 1 of the CPRs.’55 The DPPM further stated that:

where a determination is made that an exemption is available, the officer responsible for signing the Endorsement to Proceed [EtP] must ensure that the reasons supporting that determination are documented and appropriately captured.56

2.30 Defence documented its reliance on paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs in an EtP signed in August 2018 (see paragraph 3.28), two years after the July 2016 agreement by Head Joint Systems for a sole source procurement approach with Thales. The legal basis for Defence’s preferred sole source approach (that is, its reliance on paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs) was therefore not documented as part of the 2016 decision-making process on the procurement method.

Recommendation no.1

2.31 The Department of Defence document at the time the proposed procurement activities are decided:

- the circumstances and conditions justifying the proposed sole source approach, to inform subsequent procurement planning; and

- which exemption in the CPRs is being relied upon as the basis for the approach and how the procurement would represent value for money in the circumstances.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.32 Defence notes that its current Defence Commercial Framework requires officials to document the commercial basis for proposed sole source procurement activities.

2.33 Defence is reviewing the One Defence Capability System (ODCS). This review will ensure that ODCS is reflective of all relevant procurement policy considerations including sufficiently documenting for procurement planning.

2.34 A draft Project Execution Strategy (PES) for the future ownership of Benalla and Mulwala was developed, which sought to retain the factories under commercial management by Thales either under a five-year extension of the 2015 interim contract or a renegotiated version of the interim contract, under which Defence would commit to a strategic partnership with Thales and new governance arrangements.57 Under either approach, Defence would commit to a strategic partnership with Thales and new governance arrangements.

2.35 Since April 2017, the DPPM has required the development of a written procurement plan, which ‘explains how the procurement is to be undertaken’, for all procurements valued at or above $200,000 (GST inclusive).58 While not a requirement at the time59, a draft Preliminary Procurement Strategy for a Future Domestic Munitions Manufacturing (FDMM) activity was developed for the IC’s consideration in December 2016.60

2.36 The draft strategy document proposed progressing an options paper for government consideration as a ministerial submission (rather than a cabinet submission), with the draft to be considered by the IC and Defence Committee by mid-November 2016 and advice provided to the minister in December 2016.61 This approach anticipated receiving government direction in February 2017 and approval of contractual arrangements by Quarter 2 of 2019.

2.37 The draft strategy document also observed that allowing the interim contract to expire would challenge the value for money of Defence’s investment to date and Defence would be liable for the cost of decommissioning activities. The document also noted that extending Thales as the incumbent operator would not encourage competition in line with the value for money requirements of the CPRs. Rather, it was noted that Thales would be provided with significant negotiation leverage during contractual renegotiations, future munitions sales and future capital investment opportunities.

Engagement with Thales

2.38 Defence needed to engage with Thales, the current operator, on a business-as-usual (BAU) basis regarding the ongoing operation of the facilities. It was also necessary for Defence personnel to differentiate these BAU matters from procurement planning activities, so as to maintain probity in procurement and support the achievement of value for money.

2.39 Paragraph 6.6 of the 2014 CPRs stated that officials undertaking procurement must act ethically throughout the procurement, and that ethical behaviour includes ‘dealing with potential suppliers, tenderers and suppliers equitably’ (emphasis in original).

2.40 The July 2013 exposure draft of ‘Defence’s Industry Engagement during the Early Stages of Capability Development Better Practice Guide’ (BPG)62 observed that:

Defence’s engagement with industry can, if not planned and managed appropriately, involve or give rise to ‘probity’ concerns that risk damaging Defence’s reputation, the quality of Defence and Government decision making and Defence’s ability to achieve best value for money capability solutions. During the early stages of capability development (ie prior to First Pass Approval) these concerns may involve allegations of bias in favour of particular solutions or suppliers and / or risks to the competitiveness or fairness of future Defence procurement processes.

Whenever interacting with industry, Defence personnel should refrain from making verbal or written representations that could be perceived as binding or committing Defence or Government to a particular option or course of action that has not been officially endorsed or approved.63

2.41 The BPG also noted the importance of detailed planning for industry engagement to ensure that ‘all relevant probity considerations [and] risks are understood and appropriately managed’.

2.42 In early 2016, as part of its BAU activities, Defence was engaging with Thales at established governance committees, including the: Explosive Ordnance Strategic Governance Board (EOSGB) — a discussion forum for strategic level issues established under the 2015 interim contract, which was co-chaired by Defence’s Director-General Explosive Ordnance and Thales’ Managing Director of Australian Munitions; and the Munitions Manufacturing Integrated Product Team — on munitions to be manufactured during the interim contract term (discussed at paragraphs 2.18 to 2.19).

2.43 Between March and April 2016, Thales and Defence senior leaders agreed that an ‘Ordnance Summit’ between Defence and Thales be held. Thales proposed that the summit be for senior-level discussion of topics similar to those discussed at the Munitions Manufacturing Integrated Product Team meetings, including: current operations of ordnance manufacture; future orders of munitions for Australia; and joint long-term strategic goals of ordnance manufacture in Australia.

2.44 Thales developed a presentation to support discussions at the summit meeting. Versions of the presentation were provided to Defence before the summit, enabling Defence to provide input on the content prior to the meeting.64

2.45 To prepare internally for the meeting, Defence held a one-day pre-summit workshop on 12 October 2016.65 The merits and risks of each option for the facilities were discussed and a strategy was developed for the summit.66 The strategy stated that Defence would advise Thales of its intention to ‘explore the … Thales option and its merits and opportunities’ for beyond June 2020. The strategy also stated that a Defence-Thales charter should be developed, and that the key ‘next steps’ post-summit included the following.

- Use the Charter to establish principles for a working group of Defence and Thales personnel to develop a path forward from Dec 2016 to June 2017 (to start with).

- Identify that a “marching pause” is required between now [October 2016] and Dec 2016 when Defence will have confirmed (in principle) a sole source approach.

2.46 The strategy further stated that the proposed charter ‘shall contain off ramps in case progress is not being achieved, that lead to alternative open source sourcing process (and extension of the SMIC).’ Materials distributed by CASG’s Explosive Materiel Branch to Defence personnel to support the workshop, included:

- a Defence-developed issues paper (discussed in paragraphs 2.21 to 2.23)67;

- a Thales-developed ‘draft Joint Directive’68; and

- Defence analysis of the Thales presentation.

2.47 The Explosive Ordnance Summit was held on 13 October 2016 and attended by senior representatives from Defence and Thales.

2.48 The summit minutes indicate that the matters set out in the various background papers were discussed, including the design of future contractual arrangements with performance-based tenure extensions. It was agreed that the interim contract would be used as a starting point for development of future contractual arrangements and that a ‘terms of agreement’ should be drafted to support the development of an ‘evolved SMIC [the interim contract]’ with a target completion date of December 2017. The minutes also stated that:

HJS [Head Joint Systems] acknowledged the various options for consideration for the ownership and operation of the factories, and taking into account MHF [Major Hazard Facilities] licensing complications, along with Thales competence demonstrated over previous commercial arrangements, that Defence’s preference would be to progress a Government Owned Contractor Operated (GOCO-T) arrangement with Thales into the future.

2.49 These representations were made prior to final government decision-making and, as outlined by Defence’s BPG (see paragraph 2.40), could have been perceived as committing Defence and government to a course of action that had not been officially endorsed or approved.

2.50 Defence records indicate that Defence’s engagement with Thales regarding the future contractual model continued following the summit in October 2016 and up to December 2016, when the IC considered and approved CASG’s proposal to sole source to Thales. In November 2016, a Defence official sought assistance from, and provided information to, Thales on: the development of internal advice to the IC; Defence committee processes; and internal Defence thinking and positioning.69 Government information of this sort is normally considered confidential and these exchanges evidenced unethical conduct.

2.51 While planning activities for the procurement had commenced by March 2016, Defence did not implement project or procurement specific probity arrangements until July 2018, over two years later (see paragraph 4.15). Defence did not assess the probity risks or remind those involved in the procurement activities of their probity obligations before July 2018 and did not clearly differentiate between BAU engagement with Thales and its procurement planning activities.70

Was the decision to conduct a sole source process with the incumbent operator informed by appropriate advice and analysis?

Defence’s advice to the IC in December 2016 and the Minister for Defence Industry in mid-2017 on the decision to sole source was not complete. The advice did not address the legal basis for the procurement method, the risks associated with a sole source procurement approach, or value for money issues — including how Defence expected to achieve value for money and maintain commercial leverage in the context of a sole source procurement. When the IC approved the sole source procurement method in December 2016, Defence had not estimated the value of the procurement. This was not consistent with the CPR requirement to estimate the value of a procurement before a decision on the procurement method is made.

2.52 The DPPM included the following guidance between April 2017 and June 2021 relevant to adopting a sole source procurement approach:

Whilst early contractor selection and sole source procurement can also be an effective and efficient execution strategy in appropriate cases, it should not be used solely to avoid the need for competitive tendering, especially when a viable competition can be held. Sound commercial judgment, not convenience, should determine the right approach.71

Defence Investment Committee consideration — December 2016

2.53 On 9 December 2016, Deputy Secretary CASG, as the Capability Sponsor, presented the IC with options for the future of the factories and a recommended approach. The options presented were consistent with those developed in mid–2016 (see paragraphs 2.21 to 2.23): a government-owned contractor-operated (GOCO) model with the incumbent operator, Thales, or a new operator; disposal of the factories by abandonment72; a government-owned government-operated (GOGO) model73; and selling the factories to adopt a contractor-owned contractor-operated (COCO) model.74 All options apart from the GOCO model were ‘not recommended’. The recommended approach comprised the following.

- That the Mulwala propellant and explosives factories and the Benalla munitions factory be retained in Defence ownership as strategic capability enablers.

- That the current Government Owned Contractor operated arrangement be continued.

- That the tenure of the current operator of the Mulwala and Benalla factories — Thales Australia — be extended within a revised strategic partner framework.

- That CASG continue to provide management of the contractual matters, on behalf of VCDF [Vice Chief of the Defence Force] Group, as the Capability Sponsor.

2.54 The IC was advised that the recommended approach would mitigate supply chain risks and reduce shelf-life wastage associated with the stockpiling of munitions to meet preparedness requirements.

2.55 The sponsor’s paper stated that government had consistently indicated a preference to retain the factories as strategic assets, investing approximately $1.8 billion since 1999. The paper also stated that the previous DMMA procurement process had established the following.

- That ‘all potential commercial options to operate the factories would require ongoing Government subsidies to remain competitive in the world market’.

- That ‘it would take at least two years to transition the Thales “know-how” in manufacturing, qualifying and certifying propellant, explosives and munitions to any new contractor’.

- That ‘there is no expertise in Australia in the operation and maintenance of the factories as Major Hazard Facilities outside of Thales.’

2.56 As discussed in paragraph 2.37, risks associated with sole sourcing to Thales had been documented between July and September 2016 in the draft Preliminary Procurement Strategy. Those risks were not outlined in the sponsor’s paper to the IC. The term ‘value for money’ did not appear in the sponsor’s paper and the advice did not address:

- whether the conditions for a sole source procurement in the CPRs and Defence procurement guidance could be satisfied by Defence;

- the DMMA RFP evaluation findings (discussed in paragraph 2.6);

- the market’s capacity to competitively respond to a procurement;

- the estimated value of the proposed procurement (a CPR requirement)75; or

- how commercial leverage would be maintained and value for money achieved by Defence in a sole source arrangement.76

2.57 The IC was also not advised of Thales’ role in developing the paper (see paragraph 2.50).

2.58 In its comments on the December 2016 advice to the IC, Defence’s Contestability Division observed that the ‘value for money proposition of the contracts for Mulwala and Benalla [had] not been tested for more than 10 years’, and by 2025 — when the first ‘rolling wave extension’ under the new Strategic Partnership Agreement would be likely — the contract ‘will not have been competitively tested in over twenty years.’77 The Contestability Division also stated that the new arrangements should ‘involve periodic market testing, to assure value for money from an otherwise perpetual monopoly’.78

2.59 The IC agreed on 19 December 2016 to the capability sponsor’s recommendations and noted that: ‘the Defence position is that retaining these facilities is as per the Government Direction to do so’; and the ministerial submission to the Minister for Defence ‘should clearly articulate the costs associated with the facilities, the contract and the potential remediation costs down stream.’

2.60 The IC also noted that ‘the contract needs to be market tested at an appropriate future point’ and ‘that the approach to and timing of the next wave of large investment in the facilities needs to be understood by Defence as a part of the planning.’ No timeframe for doing so was proposed in the sponsor’s paper or by the IC. The IC’s decision to approve the use of a sole source procurement method was not consistent with the CPR requirement to estimate the value of a procurement before selecting the method.

Recommendation no.2

2.61 The Department of Defence, including its relevant governance committees, ensure that when planning procurements, the department estimates the maximum value (including GST) of the proposed contract, including options, extensions, renewals or other mechanisms that may be executed over the life of the contract, before a decision on the procurement method is made.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.62 Defence advises that its current Defence Commercial Framework requires officials to comply with Commonwealth Procurement Rules, including paragraphs 9.2–9.6. Defence is reviewing the One Defence Capability System (ODCS) governance and processes to reinforce these requirements.