Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Coordination and Targeting of Domestic Violence Funding and Actions

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services’ role in implementing the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan) was developed in partnership with all states and territories and endorsed and released by COAG in February 2011. The National Plan is the Australian Government’s framework to address two types of violence where women are more likely to be victims: domestic and family violence; and sexual assault.

2. The vision of the National Plan is that ‘Australian women and their children live free from violence in safe communities’.1 Governments set the target for ‘a significant and sustained reduction in violence against women and their children’2, over the 12-year plan.

3. The National Plan sets out six National Outcomes for all governments to deliver during the 12 years from 2010–2022. These National Outcomes are:

- Communities are safe and free from violence.

- Relationships are respectful.

- Indigenous communities are strengthened.

- Services meet the needs of women and their children experiencing violence.

- Justice responses are effective.

- Perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account.

4. The National Plan identifies that outcomes will be delivered through four three-yearly action plans. Governments agreed that each action plan would identify priority areas for all governments to focus on over the three-year period and practical actions designed to drive national improvements. The Third Action Plan 2016–2019, was launched in October 2016. The Fourth Action Plan is due to be launched in July 2019.

5. The Australian Government has responsibility for delivering financial support and other services through family law, legal assistance and the social security system, including crisis payments. The Commonwealth also funds national support services, primary prevention and evidence building initiatives led by national partners3 under the National Plan.

6. Total expenditure by the Commonwealth across the life of the National Plan to date, is around $723 million. This figure includes $103.9 million announced in 2016 under the Third Action Plan, $328 million announced in March 2019 in advance of the start of the Fourth Action Plan and the $101.2 million Women’s Safety Package announced in 2015.

7. The Department of Social Services (the department) is the lead Commonwealth entity overseeing implementation of the overall National Plan, three-yearly action plans and key national services. These national services, delivered by National Plan partners are:

- 1800RESPECT — a national telephone and online counselling and support service launched in 2010;

- Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) — provides access to information services, conducts and commissions research and was established in 2013;

- DV-alert — provides free nationally accredited domestic and family violence response training to frontline workers since 2007;

- Our Watch — established in 2013 to focus on primary prevention activities and raise awareness of violence against women; and

- White Ribbon — an international campaign, starting in Australia in 1992, aimed at engaging men and boys to end violence against women.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

8. Domestic violence causes long-term impacts to individuals and families as well as significant costs to the economy. Reducing these impacts involves changing individual behaviour and delivering integrated services across organisational boundaries and at all levels of government. In 2011, all Australian Governments agreed to a long-term plan to reduce violence, with the Commonwealth Government taking a leadership role. As this National Plan is in its ninth year, it is timely to assess whether the Department of Social Services has been effective in administering its responsibilities under the National Plan, including monitoring the plan’s achievements and progress.

Audit objective and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services’ role in implementing the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children 2010–2022.

10. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Effective governance arrangements are in place.

- Targeting of funding and actions is aligned to the outcomes of the National Plan.

- Monitoring and reporting of performance for key Department of Social Services’ initiatives and the National Plan is effective.

Conclusion

11. The Department of Social Services’ effectiveness in implementing the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children 2010–2022 is reduced by a lack of attention to implementation planning and performance measurement.

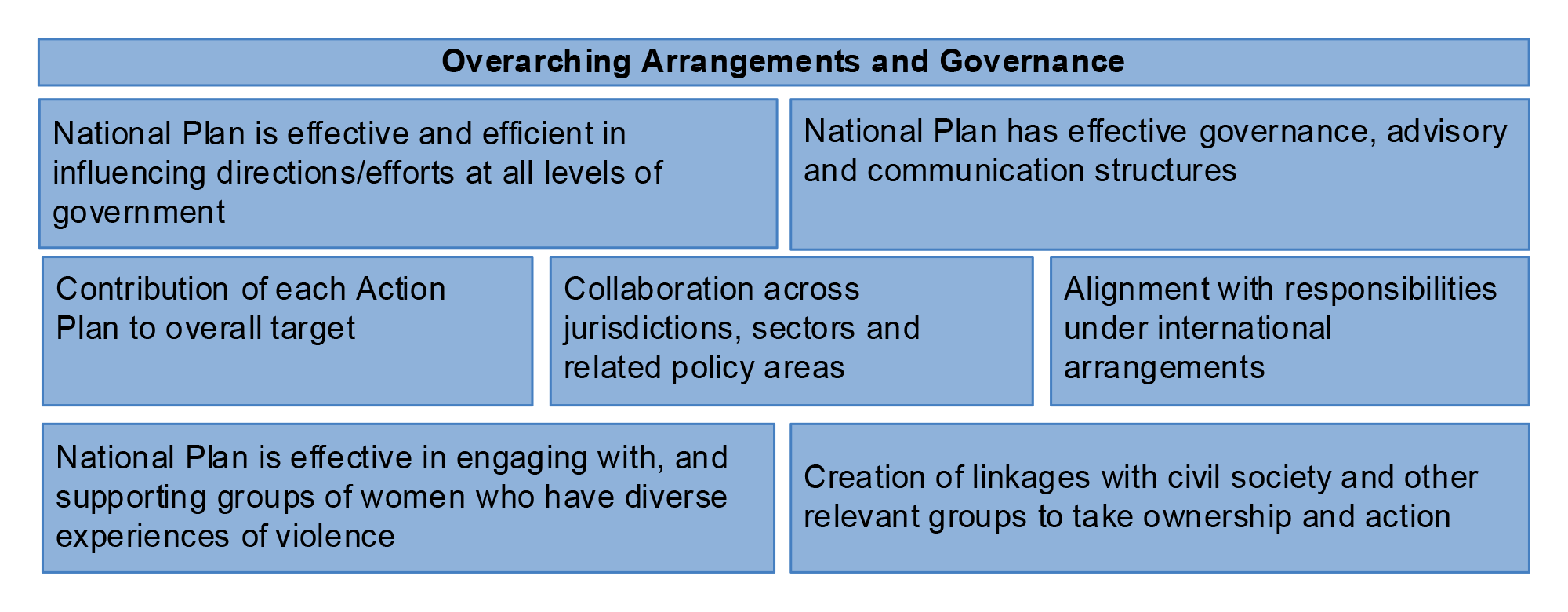

12. The department has established effective governance arrangements to support implementation of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022. These arrangements include clear accountabilities, processes for oversight and decision-making, and information sharing arrangements. The department has used a variety of mechanisms to engage formal stakeholders at key points throughout the life of the National Plan.

13. The evidence suggests that the department’s funding and actions taken during the Third Action Plan are aligned with the Plan’s key priorities and that the department established the two mechanisms required under the National Plan to improve the evidence base. The department cannot demonstrate that the actions taken are prioritised based on available evidence or that they are collectively contributing to the outcomes of the National Plan. Subsequently, there is scope to better target research activities towards projects that identify what works for whom and in what contexts.

14. Performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting is not sufficient to provide assurance that governments are on track to achieve the National Plan’s overarching target and outcomes. In order to assess and demonstrate the achievements of the National Plan as a whole, the department will need to develop new measures of success and data sources, plan for evaluations beyond the National Partner initiatives and improve public transparency.

Supporting findings

15. The roles and responsibilities for the implementation and monitoring of the National Plan are clear and fit-for-purpose for the cross-jurisdictional delivery of the National Plan. The Council of Australian Governments and relevant Commonwealth, state and territory ministers oversee implementation of the Third Action Plan and lead whole-of-government involvement. Implementation Executive Groups (ImpEG), with representatives from several Commonwealth entities and all states and territories, provide strategic and operational policy advice to ministers. The Department of Social Services develops and reports against action plans, oversees key national services and provides secretariat support to the ImpEG.

16. The department has established and implemented suitable arrangements to share and coordinate information and engage formal stakeholders, including government and non-government representatives with expertise in areas relevant to the National Plan. Mechanisms established to interact with these stakeholders include: working groups, engagement with National Plan partners, committees, National Summits and other consultations.

17. Consultations undertaken for the Second Action Plan evaluation and development of the Fourth Action Plan have identified scope to improve links with the community and collaboration with the non-government sector.

18. The National Centre of Excellence committed to in the National Plan has been established and progress made towards operationalising a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework (DCRF). In the absence of a plan identifying the sequence and priority of activities required to ensure that DCRF is operational by its target date of 2022, the department cannot demonstrate that jurisdictions are on track to deliver this outcome.

19. The department has funded research to build the evidence base. This research program as a whole does not provide sufficient focus on program evaluation and research synthesis to inform policy decisions and program improvements that contribute to achieving the National Plan’s outcomes.

20. The development of the Third Action Plan incorporated past learnings, drawing on a range of evidence including stakeholder feedback, findings from government inquiries and an evaluation report of the Second Action Plan.

21. Funding provided by the Commonwealth and administered by the department is aligned to the key priorities agreed and endorsed by all governments for the Third Action Plan. An implementation plan for the Third Action Plan was not completed, reducing the transparency around what actions governments have committed to and accountability in meeting those commitments.

22. Some metrics to assess performance against outcomes were established at the outset of the National Plan, except these currently measure limited aspects of each outcome. During development of the Fourth Action Plan and any future National Plan there is opportunity for the department to consider developing short- and medium-term outcomes, new measures of success and more frequent data collection mechanisms. Without such changes the ability for jurisdictions to demonstrate the success of the National Plan will be limited.

23. Appropriate administrative arrangements are in place to monitor progress against the Australian Government’s commitments under the National Plan’s action plans, including initiatives delivered by National Plan partners. These arrangements include monitoring project status and deliverables agreed in activity work plans.

24. Evaluations or reviews of National Partner initiatives and of the Second and Third Action Plans have been completed or are planned, but do not sufficiently focus on assessing the achievement of outcomes. The Third Action Plan evaluation methodology proposes assessing the contribution of this plan to the National Plan outcomes, but without robust data, is unlikely to achieve this purpose.

25. The quality of data and assessment of the impacts of actions undertaken across jurisdictions need to be improved to support outcome-focused action plan evaluations. Without these improvements, the overall achievements of the National Plan will not be able to be fully assessed.

26. Overall, Annual Progress Reports do not provide a sufficient level of information for public transparency and accountability. The department does not publicly report on the extent to which outcomes of the National Plan are being achieved, with the exception of the draft 2017–18 report (yet to be released). Limited internal reporting of outcomes is undertaken and is focused on disseminating results from the two National Surveys undertaken every four years.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.32

The Department of Social Services specify research and data projects as actions under each of the priority areas agreed by governments for the Fourth Action Plan.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.67

The Department of Social Services, in consultation across governments, develop a National Implementation Plan for the Fourth Action Plan.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.10

The Department of Social Services identify and develop new measures of success, data sources and specific outcomes for the Fourth Action Plan, and any future National Plan.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.45

The Department of Social Services work with the states and territories to plan evaluations of individual services and programs funded across jurisdictions under action plans to inform an outcome evaluation of the Fourth Action Plan and overall National Plan.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.61

That public annual progress reports for the Fourth Action Plan document the status of each action item and the outcomes of the National Plan as a whole.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

27. The proposed report was provided to the Department of Social Services (DSS). An extract was provided to Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety. Full responses are provided at Appendix 1. The summary response from DSS is set out below.

The department is committed to building on what the ANAO acknowledges are the effective governance arrangements already in place to support implementation of the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan). The report’s insights will help strengthen the final development phase and subsequent implementation of the Fourth Action Plan of the National Plan.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

28. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 In May 2008 the Government established an 11-member National Council4 to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the National Council) tasked with the role of drafting a national plan.

1.2 The National Council’s report Time for Action: The National Council’s Plan for Australia to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2009‐2021 was released on 29 April 2009. The report contained 11 recommendations, including that the Government refer the plan to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG); and request that COAG develop an ‘integrated, comprehensive response endorsed by all levels of government by early 2010’.5

1.3 The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan) was subsequently developed in partnership with all states and territories and endorsed and released by COAG in February 2011. The National Plan sets out a framework to address two types of violence where women are more likely to be victims: domestic and family violence, and sexual assault.6 A timeline of key events associated with the National Plan is at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of key events

Source: ANAO review of Department of Social Services documentation.

Objective and outcomes of the National Plan

1.4 The vision of the National Plan is that ‘Australian women and their children live free from violence in safe communities.’7 Governments set the target for ‘a significant and sustained reduction in violence against women and their children’8, over the 12-year plan.

1.5 The National Plan sets out six National Outcomes for all governments to deliver during the 12 years from 2010–2022. Each Outcome has an accompanying ‘measure of success’ that describes the changes expected over time. In addition, governments agreed to four high-level ‘indicators of change’, to monitor progress across the life of the National Plan and four ‘foundations for change’ that underpin the capacity of governments to work together (see Table 1.1). Reporting and monitoring against the National Outcomes and indicators of change is discussed in chapter four.

Table 1.1: National Outcomes, measures of success, indicators of change and foundations for change

|

National Outcomes |

Measures of success |

|

Communities are safe and free from violence |

Increased intolerance of violence against women |

|

Relationships are respectful

|

Improved knowledge, skills and behaviour by young people |

|

Indigenous communities are strengthened |

Reduction in the proportion of Indigenous women who consider family violence, assault and sexual assault are problems for their communities and neighbourhoods |

|

Increased proportion of Indigenous women who are able to have their say within the community on important issues including violence |

|

|

Services meet the needs of women and their children experiencing violence |

Increased access to and responsiveness of services for victims of domestic/family violence and sexual assault |

|

Justice responses are effective

|

Increased rates of women reporting domestic violence and sexual assault to police |

|

Perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account |

A decrease in repeated partner victimisation |

|

Indicators of change |

|

|

Reduced prevalence of domestic violence and sexual assault |

|

|

Increased proportion of women who feel safe in their communities |

|

|

Reduced deaths related to domestic violence and sexual assault |

|

|

Reduced proportion of children exposed to their mother’s or carer’s experience of domestic violence |

|

|

Foundations for change |

|

|

Strengthen the workforce |

|

|

Integrate systems and share information |

|

|

Improve the evidence base |

|

|

Track performance and report publicly |

|

Source: National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022, 2011.

Delivering the National Plan

1.6 The National Plan identifies that outcomes will be delivered through four three-yearly action plans. The four action plans were designed as a series to be implemented over the 12 years, each building on the other as described below:

- First Action Plan (2010–13) — Building a Strong Foundation

- focused on building an evidence base and establishing frameworks to achieve attitudinal and behavioural change.

- Second Action Plan (2013–16) — Moving Ahead

- focused on consolidating the evidence base and strengthening existing strategies.

- Third Action Plan (2016–19) — Promising Results

- the current Action Plan, launched on 28 October 2016, is intended to deliver results from the long term initiatives implemented during the first two Action Plans.

- Fourth Action Plan (2019–2022) — Turning the Corner

- ‘expected to see the delivery of tangible results in terms of reduced prevalence of domestic violence reduced proportions of children witnessing violence, and an increased proportion of women who feel safe in their communities’.9

1.7 Governments agreed that each action plan would identify priority areas for all governments to focus on over the three-year period (see Table 1.2) and practical actions designed to drive national improvements.

1.8 Governments anticipated that action plans would be at a high level and implemented in different ways by each jurisdiction. Jurisdictions would therefore indicate which actions they commit to in individual implementation plans as part of the implementation process (see from paragraph 3.63).

Table 1.2: Action Plan priority areasa

|

First Action Plan 2010–2013 |

Second Action Plan 2013–2016 |

Third Action Plan 2016–2019 |

|

Building primary prevention capacity |

Driving whole of community action to prevent violence |

Prevention and early intervention |

|

Enhancing service delivery |

Understanding diverse experiences of violence |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children |

|

Strengthened justice responses |

Supporting innovative services and integrated systems |

Greater support and choice |

|

Building the evidence base |

Improving perpetrator interventions |

Sexual violence |

|

– |

Continuing to build the evidence base |

Responding to children living with violence |

|

– |

– |

Keeping perpetrators accountable across all systems |

Note a: The Fourth Action Plan is currently being developed.

Source: ANAO presentation of priorities listed in National Action Plans.

1.9 Since the National Council presented its report to the Australian Government in 2009, domestic and family violence has been the subject of a number of reports including:

- NSW Auditor-General’s Report, Responding to domestic and family violence, 2011;

- Special Taskforce on Domestic and Family Violence in Queensland, 2014;

- Domestic and family violence services audit (Queensland), 2016;

- Royal Commission into Family Violence (Victoria), 2016;

- Commonwealth of Australia Senate Finance and Public Administration Reference Committee: Domestic violence in Australia, 2016; and

- Commonwealth of Australia Senate Finance and Public Administration Reference Committee: Delivery of National Outcome 4 of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, 2017.

1.10 Several jurisdictions now have their own plans or strategies separate from the National Plan, for example:

- Safe Homes, Safe Families: Tasmania’s Family Violence Action Plan 2015–2020;

- Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Strategy 2016–2026 (Queensland);

- NSW Domestic and Family Violence Blueprint for Reform 2016–2021: Safer Lives for Women, Men and Children;

- NSW Domestic and Family Violence Prevention and Early Intervention Strategy 2017–2021;

- NSW Sexual Assault Strategy 2018–2021;

- Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan for Change (2016);

- Free from Violence: Victoria’s strategy to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women;

- Domestic, Family & Sexual Violence Reduction Framework 2018–2028 (Northern Territory).

1.11 The National Plan is not part of the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations and is therefore not subject to the public accountability and performance reporting framework for National Agreements. Spending and implementation of specific initiatives is determined by individual jurisdictions and may reflect commitments made under the National Plan as well as jurisdictional strategies.

1.12 States and territories hold primary responsibility for delivering services for women who have experienced violence and for the administration of justice and child protection responses. The Australian Government has responsibility for delivering support and services through family law, including legal assistance and the social security system, including crisis payments. The Commonwealth also funds national support services, primary prevention and evidence building initiatives led by national partners under the National Plan.

1.13 Total expenditure by the Commonwealth across the life of the National Plan to date, is around $723 million. This figure includes $103.9 million announced in 2016 under the Third Action Plan, $328 million announced in March 2019 in advance of the start of the Fourth Action Plan and the $101.2 million Women’s Safety Package announced in 2015. Activities funded under this package support work being undertaken as part of the National Plan and are managed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Key Commonwealth initiatives and national partners

1.14 Under the National Plan the Commonwealth has established and/or supported a number of key initiatives. These initiatives are 1800RESPECT, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, DV-alert, Our Watch, and White Ribbon. Collectively the organisations that deliver these initiatives are referred to as National Plan partners.

1800RESPECT

1.15 1800RESPECT, the National Sexual Assault Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service, is a national telephone and online counselling and support service which commenced on 1 October 2010. Establishment of this service was a recommendation of the National Council’s Time for Action plan.10

1.16 1800RESPECT is operated by Medibank Health Solutions, with trauma specialist counselling sub-contracted to three not-for-profit organisations.11

Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS)

1.17 ANROWS was formed under the National Plan in 2013, fulfilling the National Council’s Time for Action plan recommendation to establish a National Centre of Excellence. It is jointly funded by the Commonwealth and state and territory governments.

1.18 ANROWS’s mission is to deliver relevant and translatable research evidence which drives policy and practice leading to a reduction in the levels of violence against women and their children. Further information about ANROWS’s contribution towards building this evidence base is in chapter three from paragraph 3.14.

DV-alert

1.19 DV-alert is a free nationally accredited training program, operated by Lifeline Australia, which aims to improve the capacity of health, allied health and frontline workers to recognise, respond to and refer clients who are experiencing, or are at risk of experiencing, domestic violence to relevant support services.

1.20 Accredited DV-alert training streams include general, Indigenous, multicultural, settlement, disability and tailored workshops, as well offering as an elearning module in the general training stream for frontline workers that are not able to attend face-to-face training. Six new training streams are being developed by Lifeline Australia and will be piloted for frontline workers in 2018–19. Community members can also attend DV-alert non-accredited awareness sessions.

Our Watch

1.21 In June 2013, the Commonwealth and Victorian governments established Our Watch as a key initiative under the National Plan. It was officially launched in September 2014.

1.22 Our Watch has launched a number of primary prevention initiatives, including:

- delivering The Line, a behavioural change campaign targeted at 12–20 year olds, that is predominantly delivered online through platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and YouTube; and

- publishing a primary prevention framework, Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia.

White Ribbon

1.23 White Ribbon is an international campaign aimed at engaging men and boys to end violence against women. It operates through primary prevention awareness raising initiatives and education programs involving young people, schools, workplaces and the broader community.

1.24 White Ribbon events have been held in Australia since 1992, with the White Ribbon Foundation established as a legal entity for operational purposes in 2007.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.25 Domestic violence causes long-term impacts to individuals and families as well as significant costs to the economy. Reducing these impacts involves changing individual behaviour and delivering integrated services across organisational boundaries and at all levels of government. In 2011, all Australian Governments agreed to a long-term plan to reduce violence, with the Commonwealth Government taking a leadership role. As this National Plan is in its ninth year, it is timely to assess whether the Department of Social Services has been effective in administering its responsibilities under the National Plan, including monitoring the plan’s achievements and progress.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.26 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services’ role in implementing the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan).

1.27 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Effective governance arrangements are in place.

- Targeting of funding and actions is aligned to the outcomes of the National Plan.

- Monitoring and reporting of performance for key Department of Social Services’ initiatives and the National Plan is effective.

Audit methodology

1.28 The audit methodology included:

- examining performance reporting, contracts and deliverables for key initiatives and grants funded by the Department of Social Services (the department);

- reviewing departmental policies and plans relevant to the National Plan and outcomes from previous evaluations and progress reports;

- reviewing minutes and Terms of Reference for key stakeholder working groups and/or committees led by the department;

- reviewing departmental reporting to government and other relevant parties; and

- interviews with department personnel and Commonwealth stakeholders.

1.29 The audit scope did not include work undertaken at the state and territory level.

1.30 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of about $509,000. The team members for this audit were Tracy Cussen, Christine Preston, Michael Fitzgerald, Hannah Climas and David Brunoro.

2. Governance and engagement arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter reports on the governance arrangements, including the roles and responsibilities and stakeholder engagement mechanisms, established to support implementation of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022.

Conclusion

The department has established effective governance arrangements to support implementation of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022. These arrangements include clear accountabilities, processes for oversight and decision-making, and information sharing arrangements. The department has used a variety of mechanisms to engage formal stakeholders at key points throughout the life of the National Plan.

Have roles and responsibilities been clearly identified and are they fit-for-purpose?

The roles and responsibilities for the implementation and monitoring of the National Plan are clear and fit-for-purpose for the cross-jurisdictional delivery of the National Plan. The Council of Australian Governments and relevant Commonwealth, state and territory ministers oversee implementation of the Third Action Plan and lead whole-of-government involvement. Implementation Executive Groups (ImpEG), with representatives from several Commonwealth entities and all states and territories, provide strategic and operational policy advice to ministers. The Department of Social Services develops and reports against action plans, oversees key national services and provides secretariat support to the ImpEG.

2.1 Delivering the outcomes of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the National Plan) is a shared responsibility of the Commonwealth, state and territory governments. Jointly these governments endorsed the National Plan and each subsequent action plan.

2.2 While there have been changes to the governance arrangements over successive action plans, these arrangements have consistently provided for cross-jurisdictional ministerial forums; oversight by senior officials; advisory functions; consultation across the sector; and reporting on the progress of action plans. The key stakeholder groups involved across the action plans are broadly set out in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Overview of governance structure for the National Plan

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Social Services documentation.

2.3 The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) oversees the National Plan and has responsibility for linking policy and investment across all levels of government. For example, both the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2021 and Women’s Safety Package (announced in September 2015) are policy initiatives with links to the National Plan.

2.4 Commonwealth, state and territory Women’s Safety Ministers12 oversee implementation of the Third Action Plan and lead whole-of-government involvement. These ministers advise COAG on matters relating to violence against women, approve significant projects agreed to by COAG13 and oversee the Women’s Safety Package. Women’s Safety Ministers meetings are supported by the Office for Women, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

2.5 The Council of Attorneys-General14 advises COAG on law enforcement, crime reduction and law reform matters and oversees relevant projects funded under the National Plan. Across 2017 and 2018 the Council: established a family violence working group; agreed to the Commonwealth working with all jurisdictions to commence reporting on National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions (NOSPI); and agreed for jurisdictions to aspire to achieve alignment with the National Risk Assessment Principles for Family and Domestic Violence (NRAP).15

2.6 The National Plan Implementation Executive Group (ImpEG) was established in 2014 under the Second Action Plan. The ImpEG comprises a Senior Officials Group (made up of Branch Manager/Executive Director equivalent officials) and, as at 2017, an Operational Group (made up of executive level officers). Both groups are represented by Commonwealth, state and territory government personnel with secretariat support provided by the Department of Social Services (the department).

2.7 Under the ImpEG’s Terms of Reference, the role of the Senior Officials Group is to provide strategic policy advice to enhance the development and implementation of the four action plans. The Senior Officials Group reviews items going to COAG such as the Stop it at the Start campaign, items going forward to Women’s Safety Ministers meetings, Third Action Plan implementation, and monitoring and reporting.

2.8 Under the Terms of Reference, the Operational Group’s role is to provide advice on operational-related activities for existing commitments as part of action plans under the National Plan. Operational group meetings have focused on jurisdictional updates on progress against action plan items, working group activity and service delivery information.

2.9 Both groups have met regularly (face-to-face and by teleconference) since they were formed. The frequency of these meetings increases during key periods, such as development of the Third Action Plans. Recent ImpEG activity has focused on planning the Fourth Action Plan, including the roundtable discussions held to inform its development.

2.10 The role and responsibilities of the ImpEG are similar to those identified under the Terms of Reference for the National Plan Implementation Panel established under the First Action Plan. The key difference between the National Plan Implementation Panel and ImpEG is the absence of representation from the non-government sector on the ImpEG groups.

2.11 Under the First Action Plan, a non-government representative was nominated by each state and territory to participate on the National Plan Implementation Panel, with up to six additional non-government representatives to be nominated by the Commonwealth. Departmental records indicate that, following completion of the First Action Plan, the Government committed to more targeted engagement with a larger group of stakeholders. The mechanisms used to engage with stakeholders are discussed further from paragraph 2.21.

2.12 Senior officials at the ImpEG meeting held on 6 March 2017 endorsed governance arrangements developed to monitor and report on the implementation of actions under the Third Action Plan. The agreed governance structure is depicted in Figure 2.2. The Minister for Social Services and Minister for Women subsequently noted these arrangements.

Figure 2.2: Governance structure for the Third Action Plan

Source: Department of Social Services documentation.

2.13 Under this governance structure the department is responsible for chairing ImpEG meetings, providing secretariat support16 to the ImpEG, liaising with National Plan partners and monitoring the work they undertake that is funded under the National Plan. Monitoring and reporting arrangements are discussed in chapter four.

2.14 Governance arrangements for the Fourth Action Plan are currently under development. The department has established a Fourth Action Plan Board and Commonwealth Senior Executive Service (SES) Steering Group17 to aid project management and development of the Fourth Action Plan.

Are suitable mechanisms in place to share and coordinate information and promote engagement with formal stakeholders?

The department has established and implemented suitable arrangements to share and coordinate information and engage formal stakeholders, including government and non-government representatives with expertise in areas relevant to the National Plan. Mechanisms established to interact with these stakeholders include: working groups, engagement with National Plan partners, committees, National Summits and other consultations.

Consultations undertaken for the Second Action Plan evaluation and development of the Fourth Action Plan have identified scope to improve links with the community and collaboration with the non-government sector.

Third Action Plan working groups

2.15 Under the Third Action Plan, state and territory-led working groups were to be established to monitor and progress key actions. Groups comprise government officials, academics, experienced managers and practitioners in the family, domestic and sexual violence sectors, and community members. The role of these groups, as defined in the Terms of Reference, is to:

bring the evidence from research, evaluations and other sources to inform the implementation of relevant Actions. They will bring members together regularly to discuss and drive work on:

- policy settings and proposals

- evidence on effective programs or approaches

- implementation, and

- monitoring the progress of implementation.

2.16 The subjects of these working groups were to be: Sexual Violence; Housing and Homelessness; Children and Parenting; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children; and Workforce Strategies. Jurisdictional leads for these working groups were confirmed at the June 2016 meeting of the ImpEG. State and territory officials were to chair established working groups and determine the frequency of meetings with the department providing support by facilitating teleconferences, providing suggestions and scoping potential research projects.

2.17 Establishment of the Workforce Strategies working group was deferred to 2018 to allow for the completion of workforce survey projects being undertaken at the state and Commonwealth level. These projects are ongoing as at March 2019.

2.18 The Sexual Violence working group did not progress, as the lead jurisdiction prioritised developing a state-level Sexual Assault Strategy.

2.19 The three established working groups (Housing and Homelessness, Children and Parenting and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children) began meeting in 2017 and provided progress updates at ImpEG meetings.

2.20 The department provided support to these three working groups by providing research and other sources of evidence to inform the implementation of actions. For example, the department set up research databases for each of these working groups from which information relevant to the subject matter of each group was accessible.The department also commissioned discrete research projects on the basis of advice from the groups that the research was required. The following research was funded by the department to support working group projects:

- National survey on the impact of tenancy laws on women and children escaping violence ($108,225), to support the Housing and Homelessness working group;

- Service system responses to the needs of children to keep them safe from violence and assess the extent to which service interventions further victimise women who are experiencing violence ($107,185), to support the Children and Parenting working group;

- Resources on how to obtain consent when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who have experienced family and domestic violence ($84,047), to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children working group; and

- Building safety in families reunifying after experiencing family and domestic violence ($399,950) to jointly support the three working groups.

Additional engagement mechanisms

2.21 The department advised the ANAO that a senior staff member from the Family Safety Branch has responsibility for engaging with sector and state and territory governments in relation to all branch activities including the National Plan. This role includes engagement with the National Plan partners (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS), 1800RESPECT, DV-alert, Our Watch and White Ribbon Australia). The Commonwealth and state and territory senior officials are members of the ANROWS Board and these jurisdictions are principal or ordinary members of the Our Watch Board.

2.22 The department leads several project-level governance groups, established to support the implementation of Commonwealth-funded initiatives under the Third Action Plan, including:

- Engaging Local Governments in Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Prevention Project Reference Committee. The group provides oversight of the local government domestic, family and sexual violence prevention project.

- National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions (NOSPI) Working Group.18 The group supports the development of the NOSPI and comprises members from women’s safety, police, justice and corrections agencies across all jurisdictions. Progress on the NOSPI is reported to COAG through the Council of Attorneys-General.

- The 1800RESPECT Performance and Improvement Committee provides oversight and review of the performance of the 1800RESEPECT service by senior executives from the department, Medibank Health Solutions (MHS) and MHS subcontractors.

2.23 A time-limited19 COAG Advisory Panel on Reducing Violence against Women and their Children was established in 2015 represented by members of the government and non-government sectors. The Panel provided three reports to COAG during its lifetime and was supported by a secretariat in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

2.24 COAG sponsored National Summits on Reducing Violence Against Women and their Children were held in both 2016 and 2018. These summits were attended by community experts, leaders, key stakeholders, Ministers and officials from across Australia. The department has also engaged with key stakeholders, across a range of mechanisms, to develop action plans (see chapter three, from paragraph 3.37).

2.25 The department also informs stakeholders about the National Plan through a dedicated website: plan4womenssafety.dss.gov.au. The website includes information about the implementation of the National Plan, including initiatives, resources, latest news and ways to get involved. Summaries of public consultations, evaluations and links to other government websites are also accessible.

2.26 In March 2017 the department released its evaluation of the Second Action Plan. That evaluation found that ‘governance, advisory and communication mechanisms were generally considered by stakeholders to be operating effectively’20, particularly in relation to gathering advice from a range of stakeholders. These stakeholder consultations also identified scope to improve links with the community and other relevant groups.

2.27 Later consultations, undertaken by the department in 2018 to inform the development of the Fourth Action Plan, also noted a need to improve collaboration and information sharing between the government and non-government sectors, specifically to reduce duplication of effort and improve congruence between state/territory planning and the National Plan.

3. Funding and targeting of resources

Areas examined

This chapter reports on the Department of Social Services’ actions to establish an evidence base to support the National Plan, develop the Third Action Plan, and fund and implement Commonwealth actions under that Action Plan. The chapter also reflects on actions undertaken to date in developing the Fourth Action Plan.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that the department’s funding and actions taken during the Third Action Plan are aligned with the Plan’s key priorities and that the department established the two mechanisms required under the National Plan to improve the evidence base. The department cannot demonstrate that the actions taken are prioritised based on available evidence or that they are collectively contributing to the outcomes of the National Plan. Subsequently, there is scope to better target research activities towards projects that identify what works for whom and in what contexts.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving the transparency and accountability around government commitments under the National Plan.

The ANAO also suggested that the department develop an implementation plan for the National Data Collection and Reporting Framework and ensure the planned review of ANROWS considers the department’s expectations around policy-relevant deliverables and processes for identifying research priorities.

Have mechanisms to build a suitable evidence base been established?

The National Centre of Excellence committed to in the National Plan has been established and progress made towards operationalising a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework (DCRF). In the absence of a plan identifying the sequence and priority of activities required to ensure that DCRF is operational by its target date of 2022, the department cannot demonstrate that jurisdictions are on track to deliver this outcome.

The department has funded research to build the evidence base. This research program as a whole does not provide sufficient focus on program evaluation and research synthesis to inform policy decisions and program improvements that contribute to achieving the National Plan’s outcomes.

3.1 Improving the evidence base is one of the National Plan’s four ‘foundations for change’ and a key priority of the National Plan. The Second Action Plan identified that improving the evidence base requires ongoing work to:

collect and report national survey data; strengthen jurisdictional administrative data so it can be shared nationally and individual pathways through systems can be followed; and produce, bring together and disseminate research that is high quality and can usefully inform policy and practice.21

3.2 The Commonwealth committed to funding two national surveys — the Personal Safety Survey (PSS) and the National Survey on Community Attitudes Towards Violence Against Women — on four-year cycles (see further discussion of these surveys in chapter four from paragraph 4.3).

3.3 To strengthen administrative data and research evidence, governments committed to develop a national Data Collection and Reporting Framework (DCRF) that will be operational by 2022; and to establish a National Centre of Excellence.

Mechanisms to improve data under the National Plan

National Data Collection and Reporting Framework

3.4 The National Plan and supporting action plans identify that the lack of nationally consistent data presents a significant challenge to measuring the progress of the National Plan. To improve the consistency and reliability of domestic, family and sexual violence data, all jurisdictions agreed to develop a DCRF with the aim of creating nationally consistent data definitions and collection methods.

3.5 Under the First Action Plan, the department funded the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to undertake a series of projects to develop the DCRF which resulted in three publications. The final of the three publications, published in 2014, was The Foundation for a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework.

3.6 This foundation report identifies key data items and recording formats required to improve reporting of family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia. It aims to provide a clear structure for data collection activities, guidance for collecting consistent and comparable data, and advice to organisations on the implementation of data storage and reporting practices.

3.7 The ABS identified, in the foundation report, that the next step in developing the statistical evidence base is applying the DCRF to existing administrative datasets and noted that the DCRF could also be used to establish new data collection activities to fill gaps in the evidence base.

3.8 The department has funded a number of projects aimed at improving administrative data sets that have collectively assisted in operationalising the DCRF across the life of the National Plan. Around $2.7 million has been provided to the ABS, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and Australian Human Rights Commission for projects across the Third Action Plan. These projects aim to:

- expand the ABS Directory of Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence22 (providing an update to the 2013 release) ($186,000);

- assess the nature, quality and coverage of family, domestic and sexual violence data collected and recorded in the legal assistance sector and to recommend improvements ($300,000);

- conduct a National Workplace Sexual Harassment Survey (building on the previous survey conducted in 2012) ($445,000);

- scope the addition of family and domestic violence flags (or indicators) to AIHW datasets, including a nationally comparable approach to adding this information to emergency data across jurisdictions and a proof of concept for service-level data ($657,521);

- continue to improve family, domestic and sexual violence related data in the ABS collections Recorded Crime, Victims and Recorded Crime, Offenders23, and develop and publish related experimental data in the Criminal Courts, Australia and Corrective Services, Australia collections ($1.014 million); and

- identify and recommend improvements to current domestic and family violence death review and data reporting mechanisms, including options for monitoring coronial review recommendations made to government entities ($110,800).

3.9 The AIHW was also funded by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments to produce two national reports that collate relevant family, domestic and sexual violence datasets. The first of these reports — Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia — was released on 28 February 2018. This report brings together information on victims and perpetrators and on the causes, impacts and outcomes of violence from multiple sources. The report highlights data gaps which, if filled, could strengthen the evidence base and support the prevention and reduction of family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia. An update to this report is due for release in June 2019.

3.10 The National Plan commits to the DCRF being operational by 2022; however, governments have not agreed an implementation plan and consequential funding arrangements for the long term development of data assets. An implementation plan was drafted in 2011 but the department was unable to verify whether it was endorsed. That plan proposed a phased approach for the development of the DCRF which aligned with the schedule for the four action plans specified in the National Plan. The first phase would deliver foundation documents and gaps analysis with subsequent phases identifying high priority areas for data development.

3.11 While the department continues to progress the implementation of the DCRF, through projects such as those noted in paragraph 3.8, the absence of a plan identifying the sequence and priority of activities needed for the DCRF to be considered operational in 2022 means the department cannot provide assurance that jurisdictions are on track to achieve this goal.

3.12 The department should work with relevant entities and jurisdictional governments to develop an agreed implementation plan for the DCRF. This plan should identify and prioritise the sequencing of key activities and funding still required to operationalise the DCRF across jurisdictions, the entity responsible for undertaking each activity and the target dates for their implementation.

Research under the National Plan

3.13 In addition to improving the available data, a primary way the National Plan intends to improve the evidence base is through increasing the volume and relevance of research on violence against women. A commitment of governments was to establish a National Centre of Excellence to bring together existing research as well as undertake new research under an agreed national research agenda.24

National Centre of Excellence

3.14 The National Centre of Excellence, later renamed Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS), was established in 2013 The Commonwealth and state and territory governments jointly fund ANROWS, with the Commonwealth providing half of ANROWS core funding and state and territory governments providing the remainder on a per capita basis. To date, ANROWS’s core funding has been provided under two contracts, the first spanning 2013 to 2015–2016 and the current contract which spans from 2016–17 to 2019–20.

3.15 The Commonwealth has committed to provide ANROWS core funding of $1.7 million per year over four years for the current 2016–20 core funding contract, with a further $1.7 million per year, from 2020–2022, subject to satisfactory performance. In addition to the core funding, ANROWS has received around $8 million from the department for a range of research projects. These projects are discussed further from paragraph 3.25.

3.16 In 2014 ANROWS developed and released a National Research Agenda, endorsed by the Commonwealth and state and territory governments. This agenda provides a framework for the ANROWS research program and identifies four strategic research themes. Table 3.1 shows how ANROWS related its four strategic research themes to the six outcomes identified in the National Plan (the National Plan Outcomes are listed in Table 1.1).

Table 3.1: National Research Agenda Strategic Research Themes mapped against the outcomes in the National Plan

|

Strategic Research Theme |

National Plan Outcomes |

|

Experience and impacts |

Research addressing this Strategic Research Theme is fundamental to the overall delivery of the National Plan and links closely to work in the National Data Collection and Reporting Framework. |

|

Gender inequality and primary prevention |

1. Communities are safe and free from violence. 2. Relationships are respectful. 3. Indigenous communities are strengthened. |

|

Service responses and interventions |

1. Communities are safe and free from violence. 3. Indigenous communities are strengthened. 4. Services meet the needs of women and their children experiencing violence. 6. Perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account. |

|

Systems (including government policy and the criminal justice, child protection and legal systems) |

3. Indigenous communities are strengthened. 4. Services meet the needs of women and their children experiencing violence. 5. Justice responses are effective. 6. Perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account. |

Source: ANROWS National Research Agenda May 2014, p19.

3.17 ANROWS has commissioned research under two grants rounds linked to research priorities developed in consultation with the department and other stakeholders. These grants rounds were held in 2014 and 2017.

3.18 Under its 2014 grants round, ANROWS identified 24 research priorities and funded 22 projects. Three main types of publications were produced:

- Compass publications — which aim to provide concise summaries of key findings of the research;

- Horizons publications — which are technical reports on empirical research produced under ANROWS’s research program; and

- Landscapes publications — which draw on published literature and existing research and/ or practice and knowledge of a specific area.

3.19 For its 2017 grants round, ANROWS identified 33 research priorities and funded 14 projects. The majority of these 14 projects addressed more than one of the 33 research priorities. Collectively these projects addressed 22 of the 33 priorities, covered each of the four strategic research themes and cost $2.5 million. All projects funded under this round were required under the grant guidance to include a focus on priority populations.25 Thirteen of the projects identified at least one of the priority populations as either an explicit topic or focus of the research. A list of the projects funded is at Table 3.2 and a list of the priority areas is at Appendix 2.

Table 3.2: Research projects funded under the 2017 grants round

|

Project title |

Funding amount |

Priority area/s addresseda |

|

The relationship between gambling and domestic violence against women |

$230,848 |

2,6 |

|

Domestic violence, social security law and the couple rule |

$21,004 |

5,7,12 |

|

Crossing the line: Lived experience of sexual violence among trans women from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse backgrounds in Australia |

$261,820 |

10 |

|

Young people as agents of change in preventing violence against women (R4Respect) |

$173,104 |

18 |

|

The MuSeS project: Multicultural and settlement services supporting women experiencing violence |

$297,874 |

4,19,22 |

|

Sustainability of identification and response to family violence in antenatal care (SUSTAIN study) |

$298,077 |

19,22 |

|

Examining the power of Child-At-Risk electronic medical record (eMR) alerts to share interpersonal violence, abuse and neglect concerns: Do child protection alerts help? |

$50,000 |

3,22 |

|

Preventing gender-based violence in inpatient mental health units |

$123,645 |

4,5,11,22 |

|

Mothers and children with disability using early intervention services: Identifying and sharing promising practice |

$254,076 |

12,14,17,19,22 |

|

Constructions of complex trauma and implications for women’s wellbeing and safety from violence |

$179,099 |

4,9,14,22,26 |

|

Transforming legal understandings of intimate partner violence |

$26,216 |

1,32 |

|

Prioritising women’s safety in Australian perpetrator interventions: The purpose and practices of partner contact |

$259,731 |

19,33 |

|

Kungas’ Trauma experiences and effects on behaviour in Central Australia |

$50,000 |

23,24 |

|

Exploring the impact and effect of self-representation by one or both parties in Family Law proceedings involving allegations of family violence |

$248,879 |

27 |

Note a: See Appendix 2 for the numbered list of priority areas.

Source: ANROWS Research Priorities (2017 grants), Summary May 2018 https://www.anrows.org.au/core-research/ [accessed 3 April 2019].

3.20 In addition to delivering or commissioning research, ANROWS is required under its contract to disseminate and promote relevant research; conduct a biennial research conference; develop and maintain a knowledge translation and exchange function; and establish a survey of stakeholders to measure the ease of access and satisfaction with the applicability of published research.

3.21 To disseminate and promote relevant research and knowledge ANROWS has produced a range of publications including practice guidelines, fact sheets and occasional papers (covering key findings from ANROWS and non-ANROWS research). It has also organised a number of events for policy makers, service providers and practitioners including two national research conferences26.

3.22 Stakeholder feedback27 from both government and non-government stakeholders, gathered from a departmental review of ANROWS published in May 201628 and survey conducted by ANROWS in 2017, noted overall satisfaction with the research produced and some areas for improvement. These survey respondents noted a need for:

- improved search functionality of the ANROWS website;

- research with a greater emphasis on policy and practice;

- short sharp overviews of each research projects and work that pulls together the outcomes of different pieces of work, integrating the research outcomes;

- a more nuanced understanding of policy developers’ needs, taking into account government and other policy developers, and the varying agendas across jurisdictions; and

- research findings to identify: what the research does and does not identify; what policy direction or options could be taken on the basis of the research and what service models should be funded.

3.23 The department’s MOU with the states and territories, concerning the operation of ANROWS, notes that a review, managed by the Commonwealth will be conducted after a period of three years, prior to committing additional funding. The terms of reference for the review are to be determined by the Commonwealth and states and territories and are to cover matters such as: the extent to which ANROWS is meeting the objects of the company as outlined in its Constitution; the usefulness of ANROWS outputs for jurisdictional policy and program development; and any other matters that the jurisdictions wish to review.

3.24 In developing the criteria for the review there may be benefit in the department considering:

- its expectations around policy-relevant deliverables and how to best communicate these to ANROWS; and

- whether the process for identifying research priorities is delivering manageable results.

Research targeting specific areas of need identified under the National Plan

3.25 Two reports29 used to inform the development of the National Research Agenda and the AIHW’s Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia 2018 report identified gaps in the evidence base, including in the areas of:

- experiences of specific population groups including children, Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders, people with disability and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people;

- services and responses that perpetrators receive; and

- the effectiveness of services and support for people that have experienced violence including the evaluation of the implementation of programs and interventions.

3.26 In addition to research funded under the agreed National Research Agenda through core funding provided to ANROWS, the department has commissioned additional projects to support actions under the Third Action Plan and to further address identified gaps. The total funding provided for this additional research under the Third Action Plan to date is around $30.7 million. This figure includes $699,407 provided for working group projects described at paragraph 2.20, and $8 million provided to ANROWS (referred to at paragraph 3.15) to: develop a perpetrator intervention research stream and grants round ($3 million); National Risk Assessment Principles ($100,000); conduct the National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey ($3.1 million); and a range of other projects.

3.27 This funding has also been used for cohort specific studies, capacity building projects, action research activities (designed to support program implementation) and additional survey and data projects. The funded parties include academics, non-government service providers and government entities, including the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A breakdown of the funded projects is at Appendix 3.

3.28 While the department maintains a list of all funded research and monitors its progress, it has not developed a plan that assists it in allocating priority to funding research, helps to identify gaps in the research evidence base or track whether identified gaps are being filled.

3.29 Overall, the research that has been funded to date has largely focused on gaining a better understanding of the experience of people from particular cohorts or in specific contexts, with limited emphasis on evaluating which services are working, for whom and in what contexts. In the small number of projects focused on reviewing or evaluating a service or service delivery approach, the ANAO found limited evidence of consideration of cost effectiveness.

3.30 With the exception of the perpetrator intervention research stream, there was limited evidence of the department planning research activities that could build on prior learnings. There would be benefit in the department examining approaches to identify short, medium and long term priorities around key topics to allow for sequencing of research activities and to build the evidence base over time.

3.31 There is also scope for the department to consider directing data and research funding towards projects such as meta-evaluations, research synthesis and other studies that draw together findings about which initiatives most effectively address National Plan outcomes. This in turn would provide policy officers across jurisdictions with more guidance on the best areas to focus funding. In order to emphasize the importance of continuing to build the evidence base, data improvement and research projects need to be explicitly reintegrated into the Fourth Action Plan.

Recommendation no.1

3.32 The Department of Social Services specify research and data projects as actions under each of the priority areas agreed by governments for the Fourth Action Plan.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

3.33 The Fourth Action Plan is under development. Each of the priority areas will identify research and data projects.

Did the development of the Third Action Plan incorporate past learnings?

The development of the Third Action Plan incorporated past learnings, drawing on a range of evidence including stakeholder feedback, findings from inquiries and an evaluation report of the Second Action Plan.

3.34 The National Plan sets out the expectation for the development of four three-yearly action plans, successively building on one another. The differences between the National Priorities set and agreed by governments for the action plans demonstrate a shift in the focus from foundation setting under the First Action Plan to making progress across systems under the Second Action Plan and demonstrating impacts for specific cohorts under Third Action Plan (see Table 3.3)

Table 3.3: Action Plan priority areas

|

First Action Plan: Building a strong foundation |

Second Action Plan: Moving ahead |

Third Action Plan: Promising results |

|

Building primary prevention capacity |

Driving whole of community action to prevent violence |

Prevention and early intervention |

|

Enhancing service delivery |

Understanding diverse experiences of violence |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children |

|

Strengthening justice responses |

Supporting innovative services and integrated systems |

Greater support and choice |

|

Building the evidence base |

Continuing to build the evidence base |

Sexual violence |

|

– |

– |

Responding to children living with violence |

|

– |

– |

Keeping perpetrators accountable across all systems |

Source: National Plan Action Plans.

3.35 The development of the Third Action Plan was to be based on wide-ranging consultation and collaboration with key stakeholders; the existing evidence base; and the evaluation of the Second Action Plans.

3.36 The Third Action Plan was endorsed by Women’s Safety Ministers on 29 September 2016 and launched by the Prime Minister on 28 October 2016.

Stakeholder engagement

3.37 The department developed an overarching process and timeline for developing the Third Action Plan,30 including a stakeholder engagement plan. Under this plan the department proposed focusing engagement on refining specific actions and building on, rather than duplicating, the range of public consultation already undertaken by governments.31

3.38 Work on the development of the Third Action Plan commenced in late 2015 with consultations between the department and other Commonwealth agencies. Feedback from the Implementation Executive Group (ImpEG) was sought (see from paragraph 2.6 for further discussion on ImpEG) and agreement, between the department and ImpEG, to a two-phased consultation approach was reached in January 2016.

3.39 The phased approach included one-on-one meetings with key stakeholders, including, but not limited to, National Plan partner organisations, and roundtable discussions. Phase one consultations focused on: sexual violence; research and evidence; appropriate responses for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children; and innovation. This early consultation informed the draft priorities developed in February 2016.

3.40 Phase two consultations were undertaken following the release of the final report of the COAG Advisory Panel on Reducing Violence Against Women and their Children in April 2016. These consultations tested and refined the priorities developed following Phase one and focused on the needs of people in priority groups including: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with disability, and those living in rural, remote and regional locations.

3.41 The roundtable discussions included more than 400 participants from the government and non-government sectors (the latter comprised service delivery organisations, academics and business). The discussions documented in a roundtable summary report reflects alignment between the issues and focus areas suggested by stakeholders and priorities identified in the Third Action Plan.

The evidence base

3.42 The Third Action Plan recognises that its start marked the halfway point of the 12-year National Plan. Work completed during the First and Second Action Plans was used to inform the development of Third Action Plan priorities.32

3.43 In addition to the stakeholder consultation described in the previous section the evidence used to inform the development of actions under the priority areas of the Third Action Plan included:

- recommendations of the final report from the COAG Advisory Panel on Reducing Violence Against Women and their Children;

- evidence emerging from recent reviews, including the Special Taskforce on Domestic and Family Violence in Queensland, the Commonwealth of Australia Senate Inquiry into Domestic Violence and the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence;

- interim findings of the evaluation of the Second Action Plan; and

- findings from the review of DV-alert (see description of DV-alert at paragraph 1.19).

3.44 In late 2015 the department prepared a discussion paper for ImpEG to provide a snapshot of current information and efforts to address violence against women and their children. The paper drew out available evidence from National Surveys, ANROWS research and findings from government inquiries against each of the National Plan outcomes.

3.45 In March 2016 ImpEG proposed 32 actions for inclusion in the Third Action Plan. These 32 actions were mapped, as relevant, to the National Plan outcomes, recommendations of the COAG Advisory Panel and Senate Inquiry33, selected research reports and prior discussion held at ImpEG meetings. Of the 36 Key Actions agreed for inclusion in the final Third Action Plan, 22 can be directly linked to proposals from ImpEG. The remaining 14 Key Actions (related primarily to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children, perpetrator interventions and domestic violence frontline services) are aligned with stakeholder feedback and findings from the evaluation of the Second Action Plan and review of DV-alert.

3.46 The COAG Advisory Panel’s Final Report on Reducing Violence against Women and their Children (released in April 2016) recommended six areas for action, with 28 associated recommendations. The Third Action Plan priority areas and actions are aligned with the Advisory Panel’s areas for action and several of its recommendations. Table 3.4 documents the Advisory Panel’s areas of action and examples of Third Action Plan actions.

Table 3.4: COAG Advisory Panel areas of action and Third Action Plan actions

|

Advisory panel areas of action |

Examples of Third Action Plan actionsa |

|

National leadership is needed to challenge gender inequality and transform community attitudes |

Drive nationwide change in the culture, behaviours and attitudes that lead to violence against women and their children

|

|

Women who experience violence should be empowered to make informed choices |

Strengthen safe and appropriate accommodation options and supports for women and their children escaping violence, including specialist women’s services |

|

Children and young people should also be recognised as victims of violence against women |

Identify and address service gaps and build capacity of specialist and mainstream service providers to recognise and respond to the impacts of violence on children |

|

Perpetrators should be held to account for their actions and supported to change |

Improve targeted perpetrator interventions, including police, courts, corrections, child protection, legal services and support, behaviour change programs, offender programs and clinical services |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities require trauma-informed responses to violence |

Establish community-driven, trauma informed supports that give choice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children who have experienced domestic, family or sexual violence |

|

Integrated responses are needed to keep women and their children safe |

Develop and implement national principles for risk assessment for victims and perpetrators of violence, based on evidence, including the risks that are present for children and other family members who experience or are exposed to violence |

Note a: The ANAO selected these examples from actions identified in the Third Action Plan, available at https://www.dss.gov.au/women/programs-services/reducing-violence/third-action-plan [accessed 28 March 2019].

Source: Commonwealth of Australia, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, COAG Advisory Panel on Reducing Violence against Women and their Children — Final Report, PM&C, 2016; Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Social Services, Third Action Plan 2016–2019 of the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against women and their Children 2010–2022, DSS, 2016.

Evaluation

3.47 The department’s evaluation plan for the National Plan notes that the purpose of the three-year implementation cycle for the National Plan is so that the department ‘can review the strategies and actions once they are implemented and design future efforts to be as effective as possible.’34

3.48 The evaluation of the Second Action Plan was completed in April 2016.35 That report identified nine areas of focus, where policy could be strengthened and government action could be focused under the Third Action Plan, to achieve greater progress against the outcomes of the National Plan. The department proposed progressing eight36 of these actions through the Third Action Plan. This proposal was noted by the Minister in August 2016.

3.49 The eight areas of focus identified in the Second Action Plan evaluation and progressed as actions under the Third Action Plan are:

- maintaining the momentum around raised community awareness of the issue of violence against women and children and encouraging community, government, businesses and sporting organisations to continue working together;

- ensuring that specialist and/or tailored services are available for women with special needs who experience violence for example Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, women with a disability, and women from culturally diverse backgrounds;

- promoting greater gender equality through programs that emphasise female leadership and empowerment, particularly in high risk groups such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and culturally and linguistically diverse communities;

- ensuring that the social media engagement strategies for The Line and Our Watch maximise contact with the public, particularly with regard to integrating social media assets;

- continuing to incorporate respectful relationships education into the school curriculum;

- continuing efforts to improve information sharing across sectors in particular between the courts, police and service providers including the national system for domestic and family violence apprehended violence orders;

- considering the future development of policy and programs that focus on addressing the particular needs of women and their children who have been exposed to sexual violence; and

- continuing to refine the evidence base to establish a base line against which success of future Action Plans can be considered.

3.50 Further information about the department’s evaluation activities are discussed from paragraph 4.31.

Actions taken to inform the development of the Fourth Action Plan

3.51 The development process for the Fourth Action Plan is similar to the development process for the Third Action Plan, consisting of consultation with key stakeholders; examination of the existing evidence base; and evaluations of previous Action Plans.