Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Commonwealth Resource Management Framework and the Clear Read Principle

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Commonwealth entities spend significant amounts of public money to deliver government outcomes each year.

- To enable the Parliament to hold the Government to account for the delivery of those outcomes, there should be a clear read through entities' reporting between the allocation and use of public resources, and the results being achieved.

Key facts

- The JCPAA has described that a clear read is demonstrated by entities' reporting:

- within a reporting cycle;

- across reporting cycles; and

- between entities.

- The Department of Finance is responsible for administering the resource management and performance reporting frameworks under the Finance Minister. This role includes providing support and guidance to assist entities, and monitoring implementation by entities.

- Entities are responsible for providing the Parliament and the public with meaningful information.

- The entities selected for this audit were the Departments of Defence, Health and Home Affairs.

What did we conclude?

- The Department of Finance's design and the selected entities’ implementation of the clear read principle is partially effective.

- Parliamentary expectations relating to a clear read have not been fully realised.

- Finance’s current guidance to entities focuses on a clear read within the reporting cycle, and does not adequately address a clear read across reporting cycles, or between entities.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations to the Department of Finance. They relate to amending requirements and guidance, and monitoring advice provided to entities to improve implementation of the clear read principle.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The use and management of public resources within the Commonwealth public sector is governed by the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework (the framework). The framework is underpinned by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), PGPA Rule and supporting directions and guidance.

2. A key objective of the principles-based framework is to establish a strong performance reporting system to demonstrate to the Parliament and the public that resources are being used efficiently and effectively by Commonwealth entities. Implementation of the framework was expected to improve both financial and non-financial performance information by placing obligations on officials for the quality and reliability of performance information. The benefits were expected to include:

…achieving a clear line of sight between the information in appropriation Bills, corporate plans, Portfolio Budget Statements and annual reports. Entities will need to define, structure and explain their purposes and achievements to create a clear read across these documents.1

3. The Minister for Finance is responsible for administering the framework and is supported by the Department of Finance (Finance).2 Finance is responsible, under the Minister, for the whole-of-government administration of the framework and related legislation. Finance is also able to issue directions and guidance on all elements of the framework.

4. The Commonwealth Performance Framework — a key element of the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework — took effect from 1 July 2015 and ‘aims to improve the line of sight between what was intended and what was delivered’.3 Finance describes the performance framework as delivering the following benefits:

The public and the parliament – like the shareholders of a company and financial supporters of charitable institutions – have a right to know what results are being achieved with the money they have provided. A balanced and complete performance framework should provide both financial and non-financial information that allows judgements to be made on the public benefit generated by public expenditure.4

5. The framework has been subject to scrutiny by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (the JCPAA), and an independent review under subsection 112(4) of the PGPA Act. Recommendations arising from this scrutiny have encompassed the design of the framework and its administration by Finance, and included matters related to the clear read, or line of sight, in key mandated publications produced by entities under the framework.

6. The role of key publications produced by entities under the framework is as follows:

- Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) — the primary financial planning document for entities;

- Corporate Plans — the primary non-financial planning document for entities; and

- Annual Reports — incorporate the performance statements and audited financial statements of entities, which report respectively on the non-financial and financial results achieved by entities.

7. Entities are expected to provide meaningful information to the Parliament and the public in their corporate plans and annual performance statements, together with the PBS, financial statements and annual reports.5 Finance issues reporting templates and guidance to assist entities in the preparation and presentation of these documents.

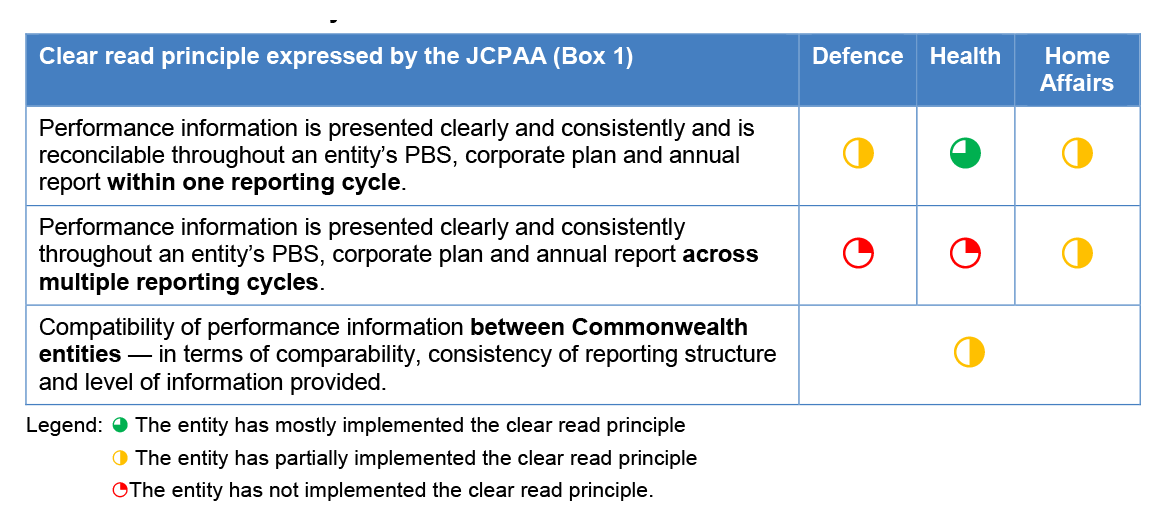

8. In December 2015 the JCPAA described — in Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework — a ‘clear read’ of entities’ performance information as exhibiting the following characteristics:

- performance information is presented clearly and consistently and is reconcilable throughout an entity’s PBS, corporate plan and annual report within one reporting cycle;

- performance information is presented clearly and consistently throughout an entity’s PBS, corporate plan and annual report across multiple reporting cycles; and

- compatibility of performance information between Commonwealth entities — in terms of comparability, consistency of reporting structure and level of information provided.

9. In this report, the ANAO has referred to these characteristics collectively as ‘the clear read principle’.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

10. Commonwealth entities spend significant amounts of public money to deliver government outcomes each year. The Commonwealth Resource Management Framework is intended to contribute to an accountable and transparent public sector by enabling the Parliament to hold the Government to account for the delivery of those outcomes through the scrutiny of entities’ performance reporting.

11. To meet this aim, reporting by entities under the framework — through PBSs, corporate plans and annual reports — should provide a ‘clear read’ and a ‘line of sight’ between the allocation and use of public resources, and the results being achieved. Parliamentary review of the framework, in particular by the JCPAA, has resulted in recommendations to support implementation of a ‘clear read’.

12. The JCPAA also recommended in December 2017 (during the third performance reporting cycle) that the ANAO ‘consider conducting an audit of one complete Commonwealth performance reporting cycle, including whether a clear read of performance information has effectively been established, with consistent terminology and improved ‘line of sight’ across performance reporting documentation’.6 This performance audit addresses the agreed recommendation.

Audit objective and criteria

13. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the design and implementation of the clear read principle under the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework.

14. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- the Department of Finance effectively established the clear read principle in the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework, and monitored its implementation; and

- the Department of Defence (Defence), the Department of Health (Health) and the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) addressed Parliamentary expectations, and established a clear read through their 2017–18 performance measurement and reporting.

Conclusion

15. The Department of Finance’s design and the selected entities’ implementation of the clear read principle under the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework has been partially effective and Parliamentary expectations have not been fully realised.

- The expectations of Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, as expressed in three reports, was that the characteristics of the clear read principle would be exhibited by entity reporting: within the annual performance reporting cycle; across multiple reporting cycles; and between entities (for example, in respect to joined-up or linked activities).

16. Finance has informed entities of the clear read principle, provided guidance on some aspects of achieving a clear read, and carried out monitoring and assessment of entities’ implementation of framework requirements. Finance’s current guidance is focused on supporting entities to implement the clear read principle within a reporting cycle. Expanding this guidance to address implementation of the clear read principle across reporting cycles and between entities would contribute to the realisation of the Parliament’s expectations. Finance could further improve its support of entities’ implementation of the clear read principle by directly providing entities with advice based on its assessments of entity reporting, and monitoring the effectiveness of its own activities on implementation.

17. The selected entities’ implementation of the clear read principle:

- within the 2017–18 reporting cycle — was mostly effective in the case of Health and partially effective in the case of Defence and Home Affairs;

- across reporting cycles — was partially effective in the case of Home Affairs and not effective in the case of Defence and Health; and

- between entities — was partially effective in the case of the three departments. A clear read was most evident in those areas where reporting was underpinned by framework requirements, in particular for the presentation of information in entity PBSs and annual reports.

Supporting findings

Design and monitoring of the clear read principle by Finance

18. As recommended by the JCPAA in Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework (December 2015), and agreed to by the Government, Finance has incorporated examples of better practice in its guidance and in its reports on lessons learned, which support entities to implement the clear read principle within a reporting cycle. However, Finance has not fully addressed this recommendation as examples of better practice reporting of joined-up programs have not been included in its guidance to entities. There also remains scope to further support entities by providing additional examples in its guidance, focusing on how to achieve a clear read across multiple reporting cycles, and promoting comparability between entities.

19. Finance’s guidance requires improvement to adequately support entities’ implementation of the clear read principle. Current guidance is focused on supporting entities to implement the clear read principle for performance information within a reporting cycle. There remains scope to promote the integration of non-financial and financial performance information through PBSs, corporate plans and annual reports. The guidance does not adequately support entities to demonstrate a clear read across reporting cycles, or between entities. In particular, the reporting of linked programs — to enable the Parliament to obtain sufficient understanding of the planned and actual performance of those programs — requires attention.

20. Finance has undertaken monitoring and review activities, including assessments of the compliance and quality of entities’ performance reporting documents, but has not yet established an ongoing evaluation initiative as recommended by the JCPAA in Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework (Recommendation 3), and agreed to by the Government. Finance is taking steps to address Recommendation 4 made in JCPAA Report 469: Commonwealth Performance Framework (December 2017), relating to a more comprehensive monitoring and evaluation program for the ongoing implementation of the Commonwealth Performance Framework.

21. Finance has communicated the broad learnings from its monitoring activities through lessons learned papers and communities of practice events. Further, Finance has provided feedback to entities when requested, and has launched transparency.gov.au, which is intended to facilitate comparisons of data between government entities. There remain opportunities for Finance to further support implementation of the clear read principle by: advising entities of the outcomes of its assessments of entity reports; maintaining records of the advice provided; and monitoring the effectiveness of its advisory activities.

Establishment of the clear read principle in entities’ 2017–18 reporting

22. The selected entities have assessed, and made improvements to, the quality of performance information they have provided to the Parliament and the public under the Commonwealth Performance Framework. This process has included the implementation of recommendations and addressing observations made by Parliamentary committees on aspects of entities’ performance reporting. There is scope for the selected entities to improve their compliance with the framework requirements for corporate plans and performance statements.

23. While the selected entities’ reporting did not fully demonstrate to the Parliament and the public a clear read of their performance within the 2017–18 performance cycle, each entity demonstrated one or more examples of better practice in the areas examined by the ANAO.

24. Health’s 2017–18 reporting most closely reflected the clear read characteristics identified by the JCPAA, in particular by taking steps to establish connections between financial and non-financial performance in its 2017–18 annual report. The clear read of Defence’s and Home Affairs’ 2017–18 reporting would have been enhanced if their PBSs and corporate plans clearly demonstrated their alignment, and the results of financial and non-financial performance were integrated. The analysis presented by the selected entities in their performance statements, and elsewhere in their annual reports, could have been improved to better demonstrate a clear read within the reporting cycle.

25. The selected entities’ reporting could better demonstrate to the Parliament and the public a clear read across performance cycles. In particular, there is scope to: explain changes to an entity’s performance framework between performance cycles; and provide comparative results to support the reader’s understanding of an entity’s performance over time.

26. A clear read between the selected entities’ reporting of their performance in the 2017–18 performance cycle was established in those areas underpinned by framework requirements for the presentation of entity PBSs and annual reports. The clear read between entities was less evident where similar framework requirements did not exist, including in respect to the presentation of corporate plans and the identification of linked programs.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.8

The Department of Finance updates guidance issued under the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework to include better practice examples of reporting that:

- is reflective of joined-up/linked programs; and

- facilitates comparison between entities.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.47

The Department of Finance amends the:

- Finance Secretary’s Direction to require a linked program presented in an entity’s Portfolio Budget Statements to also be reflected in the linked entity’s, or entities’, Portfolio Budget Statements; and

- corporate planning and annual report requirements to require entities to report on linked programs that were presented in the Portfolio Budget Statements.

Department of Finance response: Noted.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 2.66

The Department of Finance:

- advises entities of the results arising from any assessments of their Portfolio Budget Statements, corporate plans or annual performance statements;

- maintains records of advice provided to entities; and

- monitors the impact of its advice in improving implementation of the framework by entities.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

27. Summary responses from the Departments of Finance, Defence, Health and Home Affairs are provided below. Full responses can be found at Appendix 1.

Department of Finance

Finance considers that the Report does not reflect the ongoing work in this area. In particular, amendments proposed to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 and the Finance Secretary Direction will improve the link between Portfolio Budget Statements and corporate plans and improve the content of entity corporate plans.7

Finance will continue to work with entities on ways to improve the presentation of Portfolio Budget Statements, corporate plans and annual performance statements to facilitate the clear read principle.

Department of Defence

Defence acknowledges the recommendations and findings to update the guidance and information available to support agencies to strengthen performance information in and across reporting cycles.

Defence is committed to ongoing improvement in its measurement and reporting of performance in line with the broader findings of the audit. The ANAO audit analysis and findings will help Defence strengthen its approach to the 2020-21 performance framework and 2019-2020 annual performance statements.

Department of Health

The Department of Health (the department) welcomes the findings in the report and will implement the suggested opportunities to improve performance reporting to Parliament and the public.

It was pleasing to note the department was found to be largely effective in reflecting the clear read principles across the 2017-18 performance cycle. The enhanced performance reporting elements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act (2019) and the Rule has facilitated clear linkages and a consistent narrative between performance reporting documents, including the Portfolio Budget Statements, Corporate Plan and Annual Report.

Department of Home Affairs

The Department welcomes the overall conclusions and findings of the audit.

The Department notes the ANAO’s observations that the Department, and other selected entities, considered the implementation of the clear read principle and made improvements to the quality of performance information provided to Parliament and the public. In relation to this, the Department notes that the Senate Standing Committee described the overall standard of the Department’s performance reporting in its 2017-18 Annual Report as ‘extremely high’.

The Department also acknowledged the ANAO’s finding that the clear read principle was partially implemented by the selected entities. In this context, the Department notes the ANAO’s conclusion that existing guidance for entities on implementing the clear read principle has not yet been fully developed across all three areas examined. This is reflected in the three recommendations made by the ANAO, specifically related to updating and amending the Department of Finance’s existing guidance documentation available to entities. This context is important in any assessment of the Department’s application of the principle.

The Department will consider the findings and continue to improve our implementation of the clear read principle under the Enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Commonwealth entities spend significant amounts of public money each year to deliver government outcomes. In the Budget 2019–20, the Australian Government identified that Commonwealth entities would have responsibility for administering approximately $500.9 billion in expenses ‘to deliver services for individuals, families and businesses’.8 The use and management of public resources within the Commonwealth public sector is governed by the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework (the framework), which is underpinned by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).9

1.2 A key objective of the PGPA Act is to establish a strong performance reporting system to demonstrate to the Parliament and the public that resources are being used efficiently and effectively by Commonwealth entities.10 Implementation of the PGPA Act was expected to improve both financial and non-financial performance information by placing obligations on officials for the quality and reliability of performance information.11 The benefits were expected to include:

…achieving a clear line of sight between the information in appropriation Bills, corporate plans, Portfolio Budget Statements and annual reports. Entities will need to define, structure and explain their purposes and achievements to create a clear read across these documents.12

1.3 The PGPA Act is principles-based.13 In this respect the Revised Explanatory Memorandum for the PGPA Bill noted that:

The primary legislation contains the main principles and requirements and will be supported by rules … The rules made by the Finance Minister under the Bill will replace a range of instruments under the current legislation, including the … [current] Regulations and Finance Minister’s Orders. They will be used to prescribe the requirements and procedures necessary to give effect to the governance, performance and accountability matters covered by the Bill.

1.4 The Minister for Finance (Minister) is responsible for administering the framework and is supported by the Department of Finance (Finance).14 The Minister has made two rules relating to the framework to date:

- Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (the Rule); and

- Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Financial Reporting) Rule 2015 (the Financial Reporting Rule).

1.5 These rules are expected to ‘provide the detailed, technical guidance to support the nuanced application of the framework’s requirements’.15 Finance is responsible, under the Minister, for the whole-of-government administration of the framework and related legislation. Finance is able to issue directions and guidance on all elements of the framework. Since the commencement of the PGPA Act, Finance has issued two directions under subsection 36(3) of the PGPA Act. The first direction applied to estimates provided for the 2016–17 Portfolio Budget Statements. The second (and current) relates to estimates provided for the 2017–18 Portfolio Budget Statements and later years.

The Commonwealth Performance Framework

1.6 The Commonwealth Performance Framework — a key element of the resource management framework — took effect from 1 July 2015 and ‘aims to improve the line of sight between what was intended and what was delivered’.16 Finance describes the performance framework as delivering the following benefits:

The public and the parliament – like the shareholders of a company and financial supporters of charitable institutions – have a right to know what results are being achieved with the money they have provided. A balanced and complete performance framework should provide both financial and non-financial information that allows judgements to be made on the public benefit generated by public expenditure.17

1.7 The role of key publications in the framework is as follows:

- Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) — the primary financial planning document for entities;

- corporate plans — the primary non-financial planning document for entities; and

- annual reports — incorporate the financial statements and Annual Performance Statements (performance statements) of entities, which report respectively on the financial and non-financial results achieved by entities.

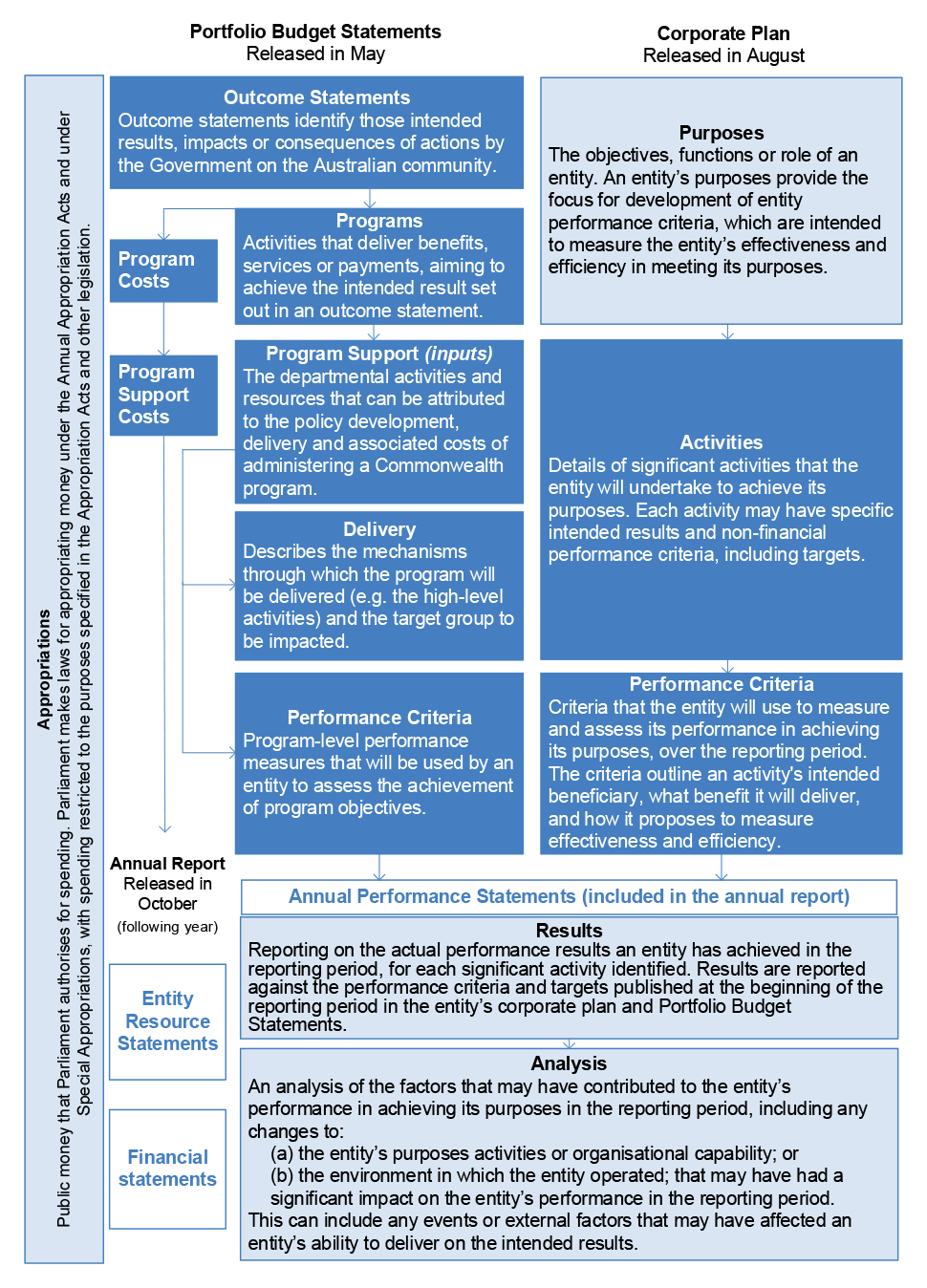

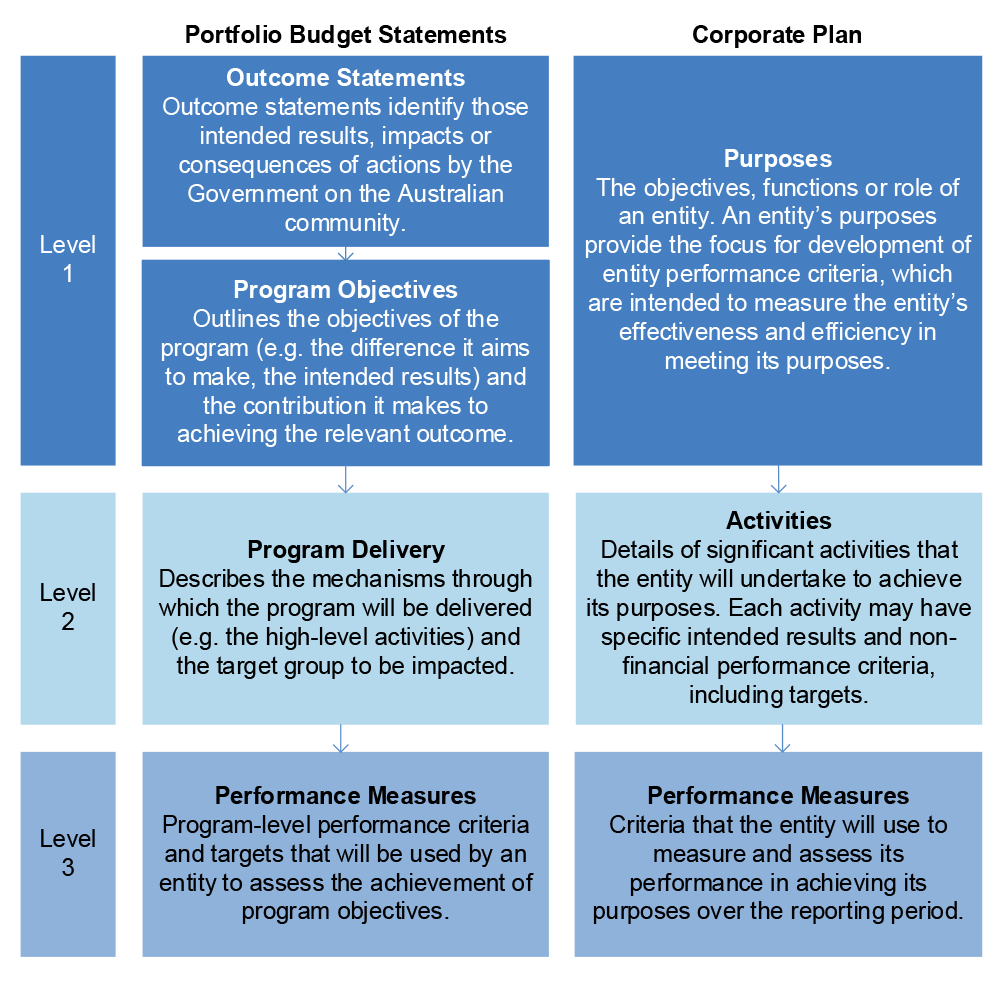

1.8 Entities are expected to provide meaningful information to the Parliament and the public in their corporate plans and annual performance statements, together with the PBS, financial statements and annual reports.18 Finance issues reporting templates and guidance to assist entities in the preparation and presentation of these documents. The information entities are required and/or guided to present in the key framework publications, are set out in Figure 1.1 below.

Figure 1.1: Commonwealth performance reporting

Source: ANAO analysis of Appropriation acts, PGPA Act and Rule, and accompanying Finance guidance.

Parliamentary review

1.9 The Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (the JCPAA) has an ongoing general oversight role with regard to the PGPA Act, and reviews all rules under the PGPA Act before they are tabled in the Parliament. 19 In addition, the JCPAA has a specific role in approving any changes to the annual report rule for Commonwealth entities under Division 6 of the PGPA Act.20

1.10 The JCPAA has conducted three inquiries relating to the performance framework since the PGPA Act was implemented.21 The reports on these inquiries are:

- Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework, December 2015;

- Report 457: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework — Second Report, May 2016; and

- Report 469: Commonwealth Performance Framework, December 2017.

1.11 In Report 469, the JCPAA commented that:

Improving the Commonwealth Performance Framework, to ensure line of sight between the use of public resources and the outcomes achieved by Commonwealth entities, has been a long-term focus of the JCPAA. In JCPAA Report 453, Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework, the Committee made the following observations relevant to this inquiry:

- the importance of a ‘clear read’ of performance information — with performance information being presented clearly and consistently throughout all relevant reports produced by a Commonwealth entity within the annual reporting cycle, and across annual reporting cycles

- the importance of establishing clear criteria (such as relevance, reliability and completeness) that performance information should satisfy

- the importance of strong and sustained leadership at all levels, including senior leadership teams within entities, to ensure the effectiveness of the new performance reporting framework

- the importance of establishing effective performance monitoring, reporting and evaluation regimes for improved accountability.22

1.12 As part of the inquiry underpinning Report 469, the Department of Finance advised the JCPAA in November 2016 that it ‘believes it will take three to five reporting cycles for mature practice to emerge’ from entities’ implementation of the performance framework.23

Characteristics of a ‘clear read’ of performance information — JCPAA

1.13 In the report from its initial (2015) inquiry into the performance framework — Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework — the JCPAA described the achievement of a ‘clear read’ as follows:

Another concept within the Framework is that of a ‘clear read’ between planning and reporting. In providing a ‘clear read’, entities must ensure that a reader can easily reconcile planned performance information presented in corporate plans and PBSs with acquittal information presented in annual performance statements and annual reports. While accounting for the diversity of entities’ roles within the Commonwealth, a ‘clear read’ also applies to working towards compatibility of performance information across entities.24

1.14 The JCPAA further commented that:

The Committee believes that a ‘clear read’ also relates to the compatibility of information across several entities — in terms of consistency of reporting structure and level of information provided. A further issue is the ability to clearly communicate the performance of co-delivered or ‘joined-up’ programs — those that are managed by multiple government entities.25

1.15 The Committee also noted that a ‘clear read’ of performance information requires clear and consistent use of terminology between budgetary and other performance information.26

1.16 Box 1 summarises the key characteristics of a ‘clear read’ or ‘clear line of sight’ based on the JCPAA’s statements in Report 453.

|

Box 1: What are the key characteristics of a ‘clear read’ of performance information? |

|

In Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework (December 2015) the JCPAA described a ‘clear read’ of entities’ performance information as exhibiting the following characteristics:

In this audit report, the ANAO has referred to these characteristics collectively as ‘the clear read principle’. |

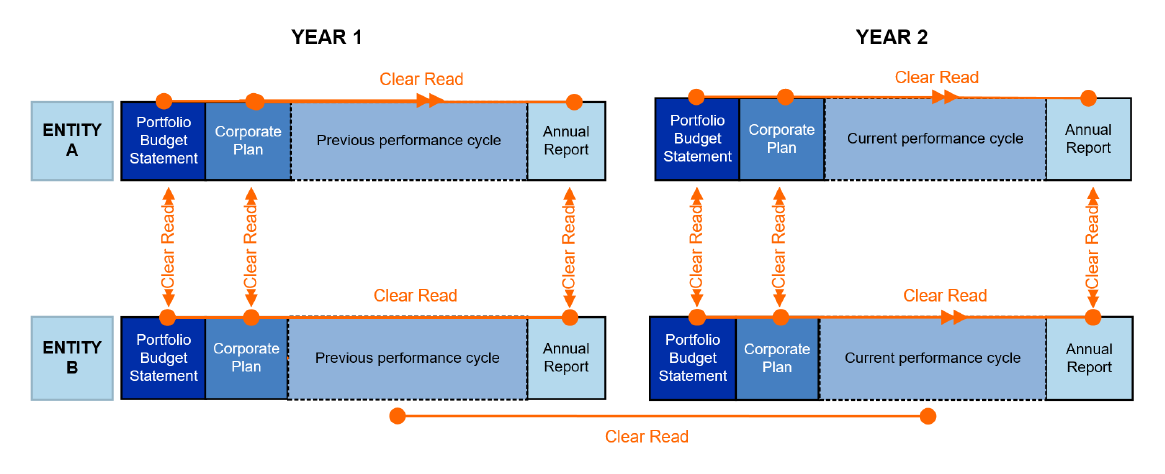

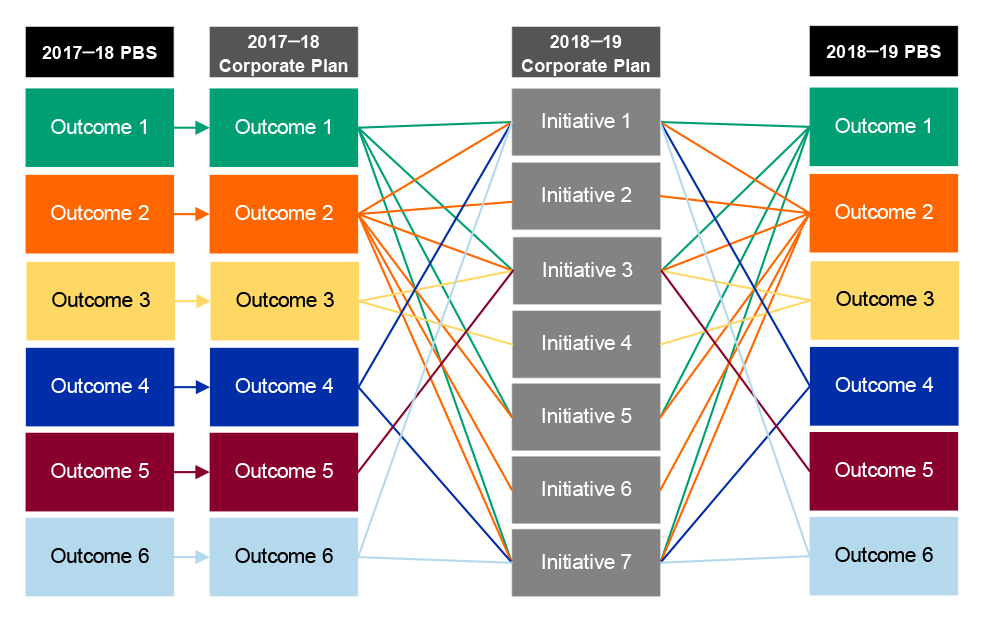

1.17 Figure 1.2 illustrates how reporting by entities under the performance framework would be connected to demonstrate a ‘clear read’ as described by the JCPAA in Report 453.

Figure 1.2: Demonstrating the clear read principle as described by the JCPAA

Source: ANAO analysis of JCPAA Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework.

Recommendations to improve implementation of the clear read principle

Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit

1.18 Since 2015, the JCPAA has made four recommendations directed to the implementation of a ‘clear read’ and ‘line of sight’ across performance information (see Table 1.1). Two recommendations were made to Finance as part of the first inquiry of the performance framework. A further recommendation was made to Finance as part of the third inquiry into the performance framework. The ANAO also received a recommendation as a result of the third inquiry.

Table 1.1: JCPAA clear read recommendations

|

Report and Recommendation No. |

Recommendation |

Response |

|

Report 453, Recommendation 1 (December 2015) |

The Committee recommends that relevant Resource Management Guidance issued by the Department of Finance demonstrates, via better practice examples, how a ‘clear read’ of performance information might be achieved — throughout an entity’s annual performance reporting cycle and for joined-up programs. |

The Government agrees. (September 2016) |

|

Report 453, Recommendation 3 (December 2015)

|

The Committee recommends that the Department of Finance commit to an ongoing monitoring, reporting and evaluation initiative for the Commonwealth Performance Framework, performance information in Portfolio Budget Statements and the broader Public Management Reform Agenda. Summary results from this initiative should be publicly reported and submitted to the Committee. Further, the Committee requests that the Department of Finance consider how it might implement this initiative — including providing details on what may be monitored and included or excluded from summary reports — and inform the Committee of its preferred approach in time for its next meeting with the Committee in February 2016. |

The Government agrees. (September 2016) |

|

Report 469, Recommendation 4 (December 2017) |

The Committee recommends that the Department of Finance (Finance) undertake a more comprehensive monitoring and evaluation program for the ongoing implementation of the Commonwealth Performance Framework, including reporting on:

Finance should provide a yearly report to the Committee on the above matters by way of a snapshot on the ‘health’ of the Commonwealth Performance Framework, with this report to also be published on the Finance website. |

The Department of Finance agrees. (June 2018) |

|

Report 469, Recommendation 5 (December 2017) |

The Committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office consider conducting an audit of one complete Commonwealth performance reporting cycle, including whether a clear read of performance information has effectively been established, with consistent terminology and improved line of sight across performance reporting documentation. |

The ANAO agrees. This performance audit addresses the agreed recommendation. (June 2018) |

Source: ANAO analysis of Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit reports.

2018 review of the PGPA Act and Rule

1.19 Subsection 112(4) of the PGPA Act requires the Minister for Finance to cause an independent review to be conducted of the operation of the PGPA Act and rules as soon as practicable after 1 July 2017. The review was asked to give consideration to the enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework, including the provision of:

Timely and transparent, meaningful information to the Parliament and the public, including clear read across portfolio budget statements, corporate plan, annual performance statements and annual reports.28

1.20 The review commenced in September 2017 and its final report was released in September 2018 with 52 recommendations. The review observed that ‘With strong support from the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, the Act promoted the idea of a clear read of performance information between portfolio budget statements, corporate plans and annual reports.’29

1.21 The Government responded to the report on 2 April 2019, noting that:

…the Government accepts, in principle, the 48 out of 52 recommendations of the Independent Review into the operation of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Rule that are within its area of responsibility.30

1.22 The report made a number of recommendations directed to improving performance reporting. Three of these related to the clear read of information being presented to the Parliament and the public by entities (see Table 1.2 below).

Table 1.2: PGPA Review clear read recommendations

|

Recommendation No. |

Recommendation |

|

Recommendation 10 |

The Department of Finance should develop ‘lessons learned’ papers that cover complete performance cycles to identify good-practice examples of a clear read of performance information across portfolio budget statements, corporate plans and annual reports. |

|

Recommendation 28 |

The Department of Finance should clarify and explain the integrated performance reporting requirements and linkages in portfolio budget statements, corporate plans and annual reports to achieve transparency to the Parliament, with reference to the views of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit and in consultation with the Australian National Audit Office. |

|

Recommendation 29 |

The Department of Finance should explore opportunities to better link performance and financial results so that there is a clear line of sight between an entity’s strategies and performance and its financial results. |

Source: E Alexander AM and D Thodey AO, Independent Review into the Operation of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Rule, Commonwealth of Australia, September 2018.

1.23 During the course of this performance audit, Finance circulated a consultation paper31 outlining proposed amendments to the Rule and Finance Secretary’s Direction. The consultation paper outlined that the amendments are intended to implement several recommendations made in the PGPA Review. Finance advised in that consultation paper that consultation on the amendments ‘would inform the Government’s response to the Independent Review, expected in early 2020’.

Previous ANAO audit coverage

1.24 The ANAO routinely examines entities’ implementation of PGPA Act requirements in the course of its work. Entities’ implementation of specific non-financial performance reporting requirements has been examined through two series of audits examining the compliance and quality of entities’ corporate plans and annual performance statements.

1.25 In this series of audits, the ANAO has made a number of observations relating to entities’ implementation of the clear read principle. In particular, the ANAO has highlighted the benefit of:

- clear and concise purposes, that are easily identifiable in the corporate plan;32

- establishing connections between corporate plan elements, such as risk oversight and management and environment33, and reflecting their influence over the results and analysis in the performance statements;34

- consistency and completeness of the presentation of performance criteria, targets and results across PBSs, corporate plans and performance statements. This includes drawing users’ attention to, or clearly explaining, overlapping measures or changes;35

- consistency in the presentation of corporate plan elements across entities;36 and

- establishing links between the funding reported in the PBS through programs, and the performance criteria presented in corporate plans.37

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.26 Commonwealth entities spend significant amounts of public money to deliver government outcomes each year. The Commonwealth Resource Management Framework is intended to contribute to an accountable and transparent public sector by enabling the Parliament to hold the Government to account for the delivery of those outcomes through the scrutiny of entities’ performance reporting.

1.27 To meet this aim, reporting by entities under the framework — through PBSs, corporate plans and annual reports — should provide a ‘clear read’ and a ‘line of sight’ between the allocation and use of public resources, and the results being achieved. Parliamentary review of the framework, in particular by the JCPAA, has resulted in recommendations to support implementation of a ‘clear read’.

1.28 The JCPAA also recommended in December 2017 (during the third performance reporting cycle) that the ANAO ‘consider conducting an audit of one complete Commonwealth performance reporting cycle, including whether a clear read of performance information has effectively been established, with consistent terminology and improved ‘line of sight’ across performance reporting documentation’.38 This performance audit addresses the agreed recommendation.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.29 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the design and implementation of the clear read principle under the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework.

1.30 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- the Department of Finance effectively established the clear read principle in the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework, and monitored its implementation; and

- the Department of Defence (Defence), the Department of Health (Health) and the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) addressed Parliamentary expectations, and established a clear read through their 2017–18 performance measurement and reporting.

1.31 This audit focused on the 2017–18 performance reporting cycle, the third reporting cycle under the current arrangements (see Figure 1.2 on page 21). The reporting cycle commenced with the publication of PBSs in May 2017 and concluded with the tabling of annual reports in September or October of 2018 — approximately 18 months later. The next opportunity to consider a complete performance reporting cycle would not occur until the conclusion of the 2018–19 performance cycle in October 2019.

1.32 The audit considered Finance’s design activities up to the 2019–20 performance reporting cycle with reporting focusing on the extent to which Finance’s guidance established the clear read principle (see Box 1) to inform entities and Finance’s activities to address agreed recommendations from JCPAA Report 453 and Report 469 (see Table 1.1).

1.33 The Departments of Defence, Health and Home Affairs each have responsibility for significant Commonwealth expenditure, which contributed to their inclusion in this audit. The ANAO also selected the entities on the basis that:

- Defence received two recommendations in the JCPAA’s Report 470: Defence Sustainment Expenditure related to the Department’s reporting under the framework, including that the Department ‘ensure a clear read of both financial and descriptive performance information’.

- Health has a large number of outcomes and programs, and was referred to in the Department of Finance’s ‘lessons learned’ papers as having demonstrated good practice in implementation of the framework.

- Home Affairs experienced significant changes during 2017–18 following the establishment of the Home Affairs portfolio.

1.34 The audit has examined the extent to which entities have established the clear read principle in performance reporting and improved the quality of information presented to the Parliament over time. Reporting in 2016–17, 2017–18 and 2018–19 and plans for 2019–20 have been reviewed.

1.35 In April 2019, the JCPAA released Report 477: Commonwealth Financial Statements – Second Report, and Foreign Investment in Real Estate. In this report, the JCPAA recommended that the ANAO consider:

…undertaking an audit of one complete Commonwealth financial reporting cycle (for one or more Commonwealth entities), focused on clarity of terminology and a clear read of financial information (line of sight) across aggregated and disaggregated financial reporting documentation (budget papers, Portfolio Budget Statements, annual reports and financial statements) — including ease of tracking financial reporting information over time.39

1.36 On 5 September 2019, the Auditor-General responded to the above recommendation, advising the JCPAA that it would be considered as a possible next step in a series of clear read audits as part of the ANAO’s future audit work program planning.40

Audit methodology

1.37 The audit involved:

- reviewing guidance and other information that Finance has issued to assist entities to establish a clear read across their PBSs, portfolio additional estimates statements, corporate plans and annual reports;

- reviewing submissions, transcripts of hearings and reports from JCPAA inquiries into the PGPA Act and Rules;

- comparing the PBSs, portfolio additional estimates statements, corporate plans and annual reports (incorporating annual performance statements and financial statements) of the Departments of Defence, Health and Home Affairs to assess whether a clear read has been established;

- examining records supporting the development and publication of PBSs, portfolio additional estimates statements, corporate plans and annual reports for the Departments of Defence, Health and Home Affairs to assess whether the clear read principle was considered across their reporting; and

- discussions with officials from the Departments of Finance, Defence, Health and Home Affairs.

1.38 To assess the extent to which the JCPAA’s expectations of a clear read of performance information have been communicated through Finance guidance and implemented by entities, the ANAO has applied the characteristics in Table 1.3 below. The characteristics were developed with reference to the JCPAA’s expectations as set out in Box 1 above, and the object of the PGPA Act that entities provide meaningful information.41 These characteristics, and Figure 1.3 demonstrating the clear read principle, were discussed with Finance prior to the commencement of this audit.

Table 1.3: Assessment characteristics of the clear read principle

|

Characteristic |

Description |

Clear read element addressed (Box 1) |

|

Clear |

Information presented in budget statements, corporate plans and annual reports can be understood by the Parliament and the public. |

|

|

Consistent |

Information presented across budget statements, corporate plans and annual reports can be interpreted consistently by the Parliament and the public. |

|

|

Reconcilable |

Planned performance presented across budget statements and corporate plans can be easily reconciled to actual performance in annual reports by the Parliament and the public. |

|

|

Comparable |

Information presented across budget statements, corporate plans and annual reports can be compared across reporting cycles, and to other entities, by the Parliament and the public. |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of JCPAA Report 453 and the PGPA Act.

1.39 The proposed changes to the Rule and Direction (as set out in a consultation paper discussed in paragraph 1.23) have not been examined as part of this audit as they had not been finalised by Finance as at the end of October 2019.

Report structure

1.40 This performance audit examined the current Finance guidance and reporting by entities, having regard to the Parliament’s expectations concerning a clear read as expressed by the JCPAA (summarised in Box 1 on page 18). In consequence there are many overlapping elements in the analysis and this audit report is technical in nature.

1.41 In light of this the report includes tables summarising the chapter findings. The tables relate to:

- Finance’s establishment of the clear read principle in directions and guidance issued to entities, having regard to the JCPAA’s expectations (see Table 2.3); and

- whether the selected entities established a clear read in their 2017–18 reporting to the Parliament and the public, consistent with Finance guidance and the JCPAA’s expectations (see Table 3.1).

1.42 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $357,300.

1.43 The team members for this audit were Jennifer Hutchinson, Kara Ball and Sally Ramsey.

2. Establishment and monitoring of the clear read principle by Finance

Areas examined

This chapter considers whether the Department of Finance (Finance) effectively established the clear read principle, as expressed by the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), in the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework, and monitored its implementation.

Conclusion

Finance has informed entities of the clear read principle, provided guidance on some aspects of achieving a clear read, and carried out monitoring and assessment of entities’ implementation of framework requirements. Finance’s current guidance is focused on supporting entities to implement the clear read principle within a reporting cycle. Expanding this guidance to address implementation of the clear read principle across reporting cycles and between entities would contribute to the realisation of the Parliament’s expectations. Finance could further improve its support of entities’ implementation of the clear read principle by directly providing entities with advice based on its assessments of entity reporting, and monitoring the effectiveness of its own activities on implementation.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made three recommendations to Finance. They relate to amending requirements and guidance, and monitoring advice provided to entities to improve implementation of the clear read principle.

2.1 The JCPAA, through its inquiries into the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and Commonwealth Performance Framework, has expressed the Parliament’s expectations with regard to the clear read principle (Box 1). This chapter assesses whether the Department of Finance (Finance), in its role administering the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework, has:

- implemented recommendations made by the JCPAA, and agreed to by the Government, in regard to establishing the clear read principle;

- provided entities with adequate guidance to support their implementation of the clear read principle; and

- effectively monitored implementation of the clear read principle, including in response to recommendations made by the JCPAA, and agreed to by the Government, in regard to Finance’s monitoring and evaluation of the framework.

Has Finance implemented the JCPAA’s recommendation to provide examples of better practice to support entities’ implementation of the clear read principle?

As recommended by the JCPAA in Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework (December 2015), and agreed to by the Government, Finance has incorporated examples of better practice in its guidance and in its reports on lessons learned, which support entities to implement the clear read principle within a reporting cycle. However, Finance has not fully addressed this recommendation as examples of better practice reporting of joined-up programs have not been included in its guidance to entities. There also remains scope to further support entities by providing additional examples in its guidance, focusing on how to achieve a clear read across multiple reporting cycles, and promoting comparability between entities.

2.2 In Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework, the JCPAA stated that:

Guidance produced by Finance stresses the importance of achieving a ‘clear read’, however, at present there is a lack of examples or case studies of better practice. Such examples may provide entities with a useful compass during a period of significant change and assist entities to more rapidly understand the expectations from reporting. Examples may also assist in achieving some level of consistency between reports from different entities.

2.3 The JCPAA recommended (Recommendation 1, Report 453) that Finance demonstrate, via better practice examples in its resource management guidance, how a ‘clear read’ of performance information might be achieved — throughout an entity’s annual performance reporting cycle and for joined-up42 programs.43 The Government agreed to the recommendation in September 2016.

2.4 As outlined in paragraphs 1.4 and 1.5, Finance issues directions and guidance (known as Resource Management Guides or RMGs) under the PGPA Act to assist accountable authorities in discharging their responsibilities under the framework.44 The resource management guidance applying in the 2017–18 reporting period is set out in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Guidance issued by Finance — 2017–18 performance reporting period

|

Portfolio Budget Statements |

Corporate Plans |

Annual Performance Statements |

Financial Statements |

Annual Reports |

|

RMG 130 — Overview of the enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework |

||||

|

Guide to the preparation of the 2017–18 PBS |

RMG 132 — Corporate plans for Commonwealth entities RMG 131 — Developing good performance information |

RMG 134 — Annual Performance Statements for Commonwealth entities |

RMG 125 — Commonwealth Entities Financial Statements Guide |

RMG 136 — Annual Reports for non-corporate Commonwealth entities |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.5 The clear read principle is referenced in a number of Finance’s RMGs, as outlined in Table 2.2 below. Two RMGs included examples of better practice, drawn from Finance’s reports on lessons learned (discussed further from paragraph 2.56).

Table 2.2: References to ‘clear read’, and better practice examples in Finance’s Resource Management Guides

|

Guidance |

Is ‘clear read’ referenced? Were relevant better practice examples included? |

|

RMG 125 Commonwealth Entities Financial Statements Guide, March 2018 |

‘Clear read’ is referenced. No examples of a clear read are included. |

|

RMG 130 Overview of the enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework, July 2016 |

‘Clear read’ is referenced. No examples of a clear read are included. |

|

RMG 131 Developing good performance information, April 2015 |

‘Clear read’ is referenced. No examples of a clear read are included. |

|

RMG 132 Corporate plans for Commonwealth entities, January 2017 |

‘Clear read’ is referenced. Better practice examples (nos. 1–7, and 11) focus on:

|

|

RMG 134 Annual Performance Statements for Commonwealth entities, July 2017 |

‘Clear read’ is referenced. Better practice examples (nos. 1, 6, 8, 10 and 11) focus on:

|

|

RMG 135 Annual Reports for non-corporate Commonwealth entities, May 2018 |

Clear read’ is referenced. No examples of a clear read are included. |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.6 Finance’s guidance for the preparation of the PBS also referenced the ‘clear read’.45 Entities were provided with templates that demonstrated how to: link PBS programs to purposes in the corporate plan; and present new or modified criteria in the PBS across reporting cycles. 49F

2.7 The better practice examples and templates that Finance has included in its guidance illustrate elements of a clear read of performance information within a reporting cycle, and across reporting cycles. Finance has not included examples of better practice reporting of joined-up or linked programs as sought by the JCPAA (and agreed by Government in September 2016). Examples of better practice reporting that promotes comparability between entities (one of the three key characteristics outlined by the JCPAA) are also not included in Finance guidance.

Recommendation no.1

2.8 Finance updates the guidance issued under the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework to include better practice examples of reporting that:

- is reflective of joined-up/linked programs; and

- facilitates comparison between entities.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

2.9 (a): Agree, noting that enhancements to Finance guidance relating to the reporting of linked programs is dependent on Government consideration of the issues raised in Recommendation 2.

2.10 (b): Agree, noting that improvements to comparisons between entities need to be consistent with the principles-based framework.

Is the guidance provided by Finance adequate to support entities’ implementation of the clear read principle?

Finance’s guidance requires improvement to adequately support entities’ implementation of the clear read principle. Current guidance is focused on supporting entities to implement the clear read principle for performance information within a reporting cycle. There remains scope to promote the integration of non-financial and financial performance information through PBSs, corporate plans and annual reports. The guidance does not adequately support entities to demonstrate a clear read across reporting cycles, or between entities. In particular, the reporting of linked programs — to enable the Parliament to obtain sufficient understanding of the planned and actual performance of those programs — requires attention.

2.11 As discussed in paragraph 1.3, the PGPA Act is principles-based. The success of entities’ implementation of those principles will be influenced by the quality of the guidance and support they are provided by Finance, the framework administrator. The ANAO examined whether Finance’s guidance46 has helped establish the clear read principle in the Commonwealth Resource Management framework, focusing on the extent to which Finance guidance addresses the three key characteristics of a clear read as expressed by the JCPAA (as summarised in Box 1).

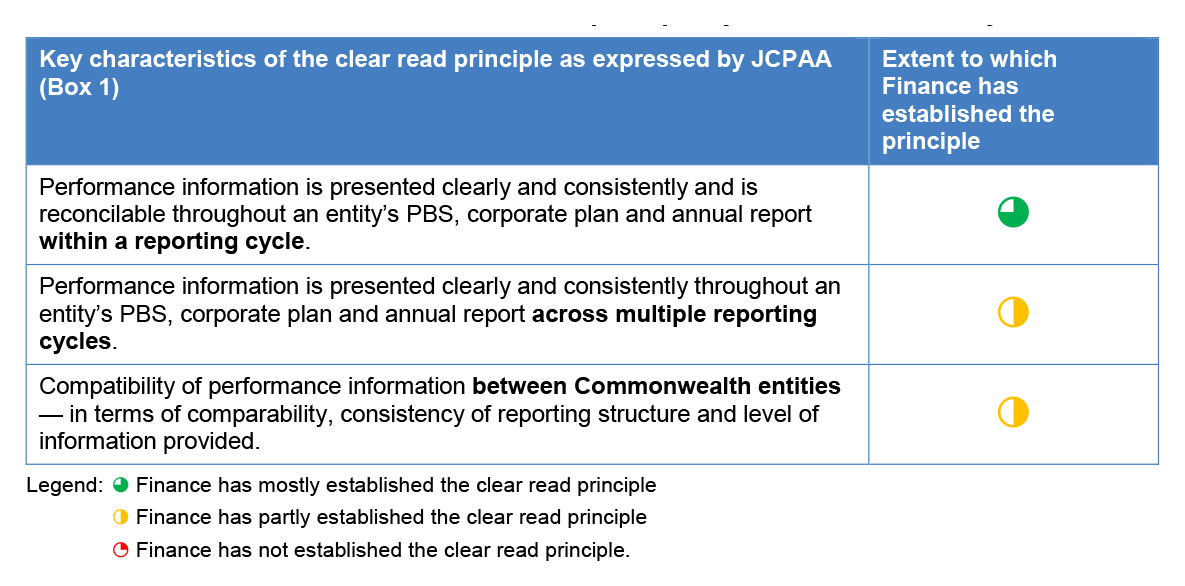

2.12 Table 2.3 provides a high level summary of the ANAO’s findings formed on the basis of the detailed analysis presented in this chapter.

Table 2.3: Establishment of the clear read principle by Finance — summary

Source: ANAO analysis.

Guidance supporting the provision of clear, consistent and reconcilable performance information within a reporting cycle

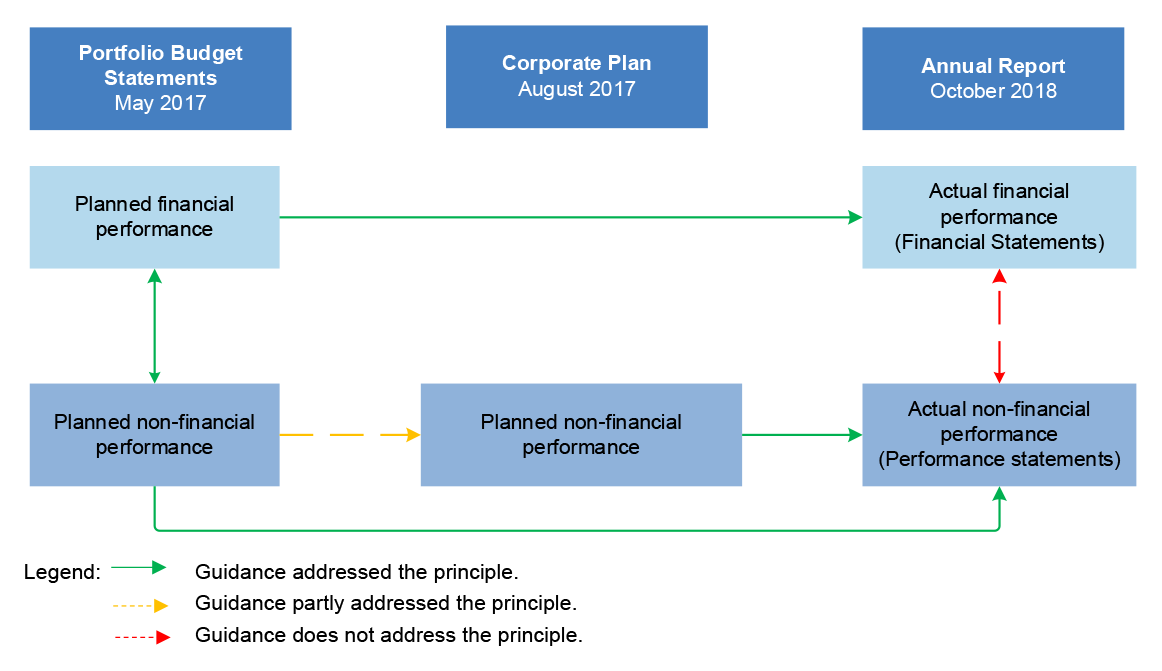

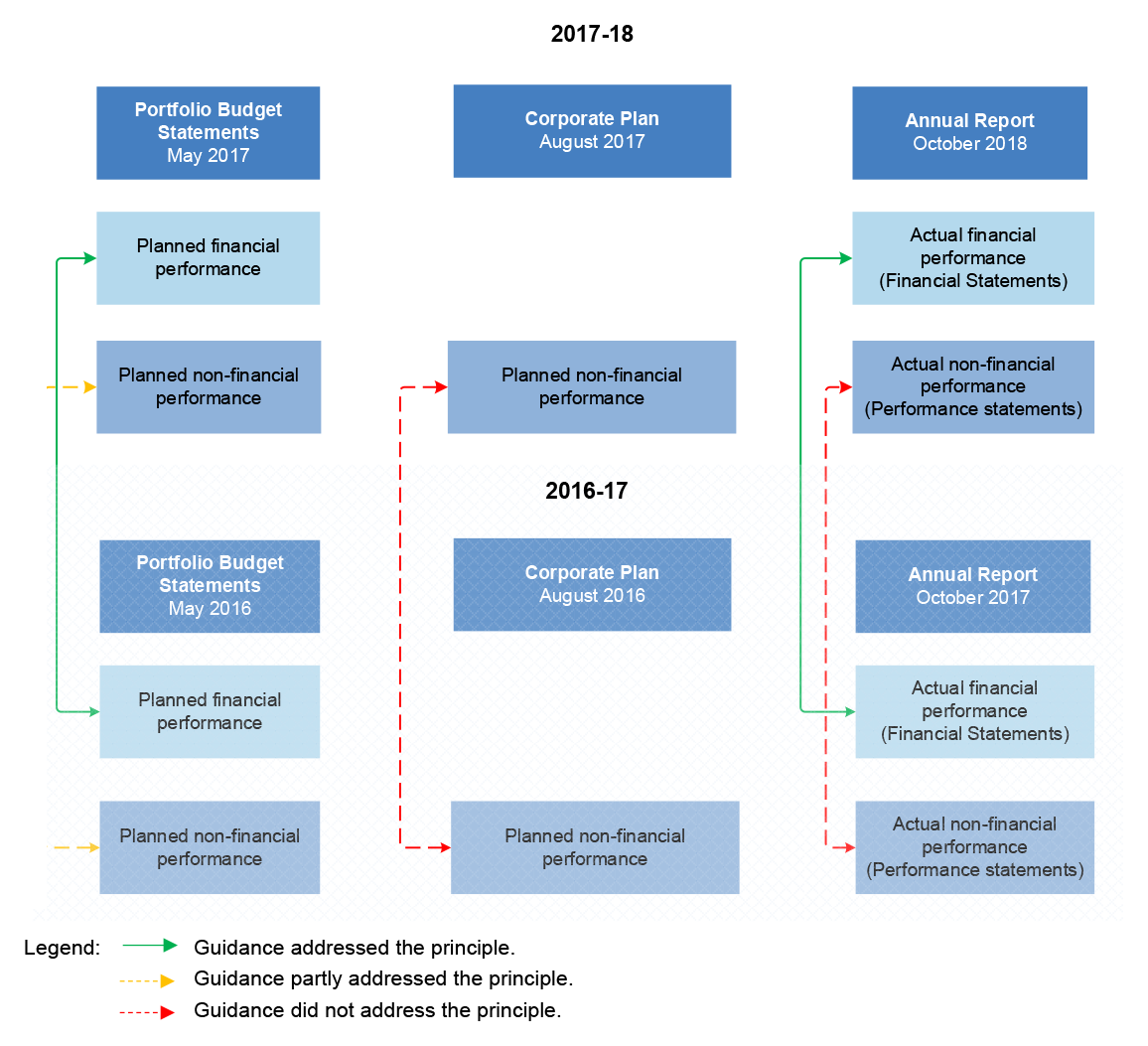

2.13 Finance’s guidance has mostly established the clear read principle to support entities’ implementation of the principle within a reporting cycle. Figure 2.1 on the following page shows those areas of Finance’s guidance that address the clear read principle (green arrows) and areas where the design could be improved (yellow and red arrows).

Figure 2.1: Assessment of the clear read within a reporting cycle 2017–18

Source: ANAO analysis of Finance guidance.

2.14 The PGPA Act, the Rule and the Finance Secretary’s Direction provide a basis for implementation of the clear read within a cycle (green arrows) by establishing requirements for entities to:

- prepare estimates for the budget statements in accordance with the Finance Secretary’s Direction. The direction requires an entity to present at least one performance criteria for each PBS program (see Appendix 2);

- prepare financial statements that comply with the Australian Accounting Standards, including AASB 1055 Budgetary Reporting, by presenting analysis in the audited financial statements that provides a comparison of planned financial performance set out in the PBS to actual financial performance; and

- acquit their planned non-financial performance set out in the PBS and the corporate plan in the annual performance statements.

2.15 These requirements are supported by Finance’s resource management guides and other guidance material, as discussed from paragraph 2.4.

2.16 Areas where the PGPA Rule, Finance Secretary’s Direction, and/or guidance could be improved with regard to delivering a clear read within the cycle are:

- actual financial and non-financial performance in annual reports (red arrow); and

- planned non-financial performance set out in the PBS and in corporate plans (yellow arrow).

Connecting actual financial and actual non-financial performance in annual reports

2.17 The explanatory memorandum for the PGPA Bill states that under the PGPA Act and Rule, an integrated entity annual report ‘brings together information about an entity’s strategy, governance and financial and non-financial performance’ and that:

An integrated annual report is an important way to strengthen accountability, along with improving the consistency of reporting requirements and achieving a clearer line of sight between reporting documents.47

2.18 As discussed in paragraph 1.6, Finance has also stated that the Parliament and the public have a right to know what results are being achieved with the money they have provided, and that:

A balanced and complete performance framework should provide both financial and non-financial information that allows judgements to be made on the public benefit generated by public expenditure.48

2.19 Under the PGPA Act, entities are required to report actual financial performance in financial statements49, and non-financial performance in performance statements.50 Subsections 43(4) and 39(1)(b) of the PGPA Act respectively, require these statements to be presented to the Parliament in the entity’s annual report.

2.20 There is no requirement in the PGPA Rule for entities to integrate, or relate, the analysis presented in the performance statements to the financial statements, or to the report on financial performance.51 Presenting analysis in the annual report that integrates these results would provide a basis for the Parliament to connect the outcomes delivered by an entity to the costs associated with their delivery. Finance’s annual report guidance references this concept, noting that:

A strong emphasis is placed on compatibility between budget and performance information documents, and entities should focus on presenting an annual report that combines with the entities’ annual performance statement to provide a clear end-of-cycle picture of an entity’s performance.

2.21 However, there is no detailed guidance, or examples, to demonstrate how this concept should be applied in practice by entities.52 Addressing this matter could improve the quality of information provided to the Parliament and the public, enabling judgements to be made on an entity’s holistic performance, rather than financial and non-financial performance separately.

Connecting planned performance between the PBS and corporate plan within a reporting cycle

2.22 The Finance Secretary’s Direction under subsection 36(3) of the PGPA Act requires: entities to present planned performance criteria and forecasted results in the PBS; and the ‘mapping the PBS outcomes, programs and performance criteria to the entity’s purposes as expressed in its corporate plan.’53

2.23 The decision to issue a direction was noted in the Government response to JCPAA Report 453 Recommendation No. 1. The response noted that a Finance Secretary’s Direction would ‘provide for a clear read throughout an entity’s annual performance reporting cycle and for joined-up programs.’ 54 The direction is reproduced at Appendix 2 and the background to the direction is outlined in Box 2 below.

|

Box 2: Background to the Finance Secretary’s Direction |

|

As part of the JCPAA’s role in overseeing the development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework, the committee considered an early proposal by Finance to remove non-financial performance information from the PBSs. The Committee did not accept this proposal and made commencement of the performance framework conditional on the retention of performance information in the PBSs,55 noting that:

To address the committee’s views, Finance proposed the use of a Finance Secretary’s Direction that would require entities to include specific information in their PBS. The Committee agreed to this approach, but noted:

Other performance reporting requirements are set out in the PGPA Rule. |

2.24 The Finance Secretary’s Direction does not sufficiently establish a clear read throughout an entity’s annual performance reporting cycle as described by Finance to the JCPAA. The ANAO has previously observed that where an entity’s PBS outcomes and programs are not clearly aligned to the purposes and underpinning activities of the corporate plan, this can make it difficult for a reader to determine the connection between planned resources and performance measurement.58

2.25 Auditor-General Report No.17 2018–19 Implementation of the Annual Performance Statements Requirements 2017–18 — the most recent ANAO examination of the performance framework — commented in respect to the Finance Secretary’s Direction that:

Finance may also consider whether the Finance Secretary’s Direction is assisting to establish this alignment [between financial and non-financial performance], or if requiring entities to map their PBS program performance information to a level lower than the purpose, such as objectives or activities, would improve this line of sight.59

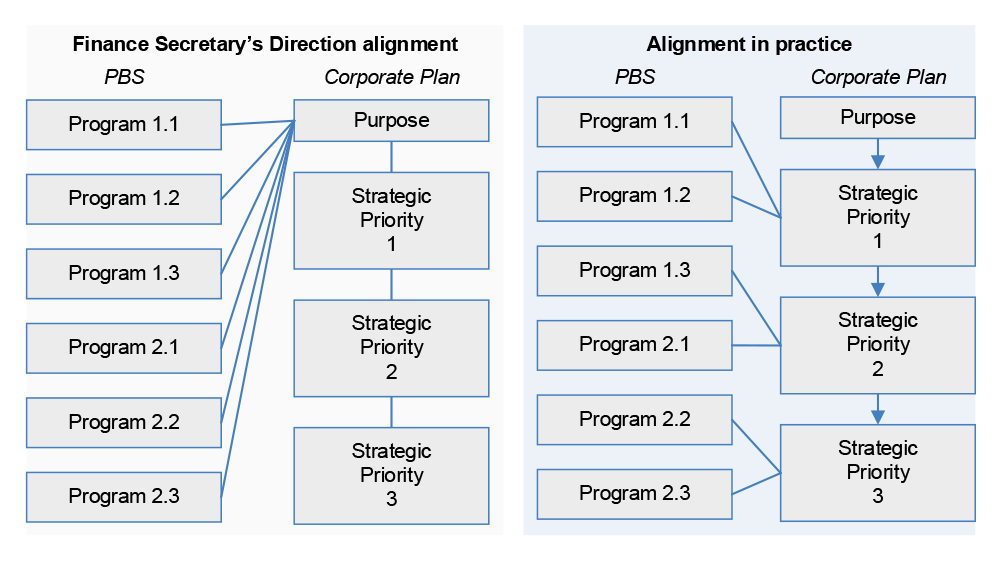

2.26 To illustrate the problem, Figure 2.2 provides an example of the difficulty which arises where an entity has a series of strategic priorities set out in the corporate plan that underpin a single purpose (see the ‘Alignment in practice’ section of Figure 2.2). Under the Finance Secretary’s Direction, the alignment of PBS programs to those strategic priorities is not visible as the programs are required to be mapped to the purpose only (see the ‘Finance Secretary’s Direction alignment’ section of Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Example of the reported alignment between the PBS and corporate plan to address the Finance Secretary’s Direction, compared to the alignment in practice

Source: Example developed by the ANAO based on analysis of the Finance Secretary’s Direction.

Guidance supporting the provision of consistent and comparable performance information across reporting cycles

2.27 Finance’s guidance has partly established the clear read principle to support entities’ implementation of the principle across reporting cycles. Figure 2.3 shows those areas of the direction and guidance that address the clear read principle (green arrows) and areas where the design could be improved (yellow and red arrows).

Figure 2.3: Clear read across reporting cycles (2016–17 and 2017–18)

Source: ANAO analysis of Finance guidance.

2.28 The PGPA Act provides a basis for implementation of the clear read across cycles (green arrows) by establishing requirements for entities to:

- prepare estimates for the budget statements as directed by the Minister for Finance. This is further supported by Finance’s Guide to preparing the 2017–18 Portfolio Budget Statements, and accompanying templates, which set out the presentation of planned financial performance, including estimated actuals for the previous financial year to enable comparison across cycles; and

- prepare financial statements that comply with the Australian Accounting Standards, by presenting prior year results in the audited financial statements60, and disclosing any material changes to, or errors in, those comparative results.61 This is supported by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Financial Reporting) Rule 2015, and Finance guidance.

2.29 Areas where the PGPA Rule and/or Finance guidance could be improved are:

- non-financial performance set out in corporate plans and performance statements across reporting cycles (red arrows); and

- non-financial performance set out in the PBS across reporting cycles (yellow arrow).

Comparing non-financial performance information presented in corporate plans and performance statements across reporting cycles

2.30 Under the framework, an entity is not required to highlight and/or explain changes made to the corporate plan across reporting cycles.62 This includes changes to key elements such as an entity’s purpose, activities and/or planned performance measures across years. Changes to these elements (in particular performance measures) between reporting periods should be explained to a reader to address the clear read principle. Finance does not address these matters in its guidance.

2.31 This approach contrasts with the approach taken to an entity’s financial performance, where the results from the previous reporting period are required to be included in the financial statements. Further, any material changes to an entity’s accounting policy between years, and the associated financial impact, must be described to the reader in the financial statements.63 Implementation of the clear read principle would be strengthened if entities were expected to adopt a similar standard for financial and non-financial reporting, by: presenting comparative results in the performance statements; and explaining changes and/or errors across reporting cycles.

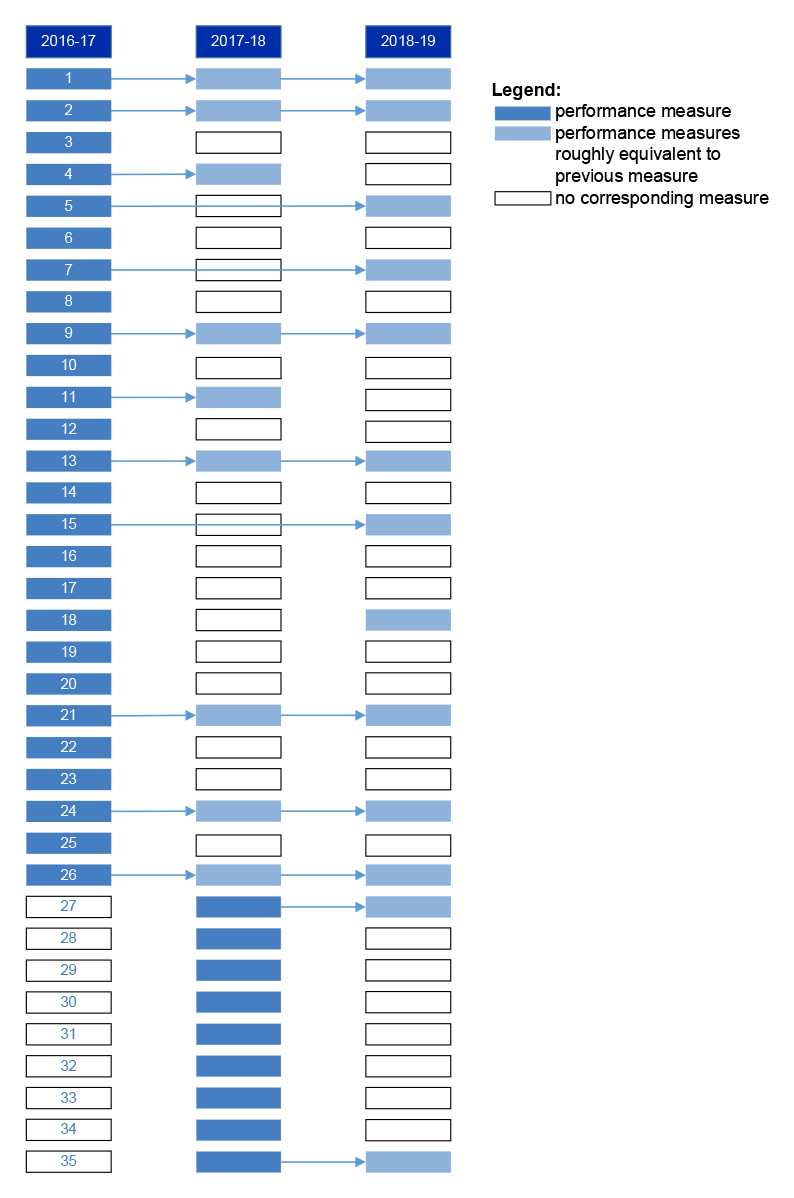

Comparing non-financial performance presented in PBSs across reporting cycles

2.32 The Finance Secretary’s Direction requires entities to ‘include forecasts of program performance against expected targets for the current financial year’.64 In practice, this means that an entity’s 2017–18 PBS was expected to contain a forecast of performance against the measure and target presented in 2016–17, as well as the expected performance for the upcoming year and forward estimates periods. This information was intended to provide users of the PBS with a basis to identify changes to measures between reporting periods.

2.33 An entity’s PBS must also include ‘all performance criteria, targets and expected dates of achievement’ for new programs and programs that have materially changed65 since the previously presented budget.66 When the JCPAA was considering the proposed Finance Direction in 2015, Finance advised the Committee that this approach ‘gives a much clearer read as to the impact of the moneys that we are seeking the parliament to appropriate and the impact those moneys will have on government activities.’67 Finance guidance advises entities to mark these material program changes through italicisation and underlining of the new or amended measures — signalling to the PBS user that a change occurred between cycles.

2.34 This approach only partly addresses the issue of providing a clear read across reporting cycles because entities are not required to explain changes to their performance criteria for an existing program that was not subject to a material change.68 Finance’s guidance for the preparation of PBS does not address this matter.

Guidance on the provision of comparable performance information between Commonwealth entities

2.35 In Report 453, the JCPAA observed that a clear read also ‘applies to working towards compatibility of performance information across entities’.69 Finance’s guidance reiterates this as an aim of the enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework, noting that:

The aim is for published performance data to provide high-level information about the extent to which government policy objectives are being met. Such performance information will support a more joined-up view of government activity by providing the parliament and the public with the means to relate contributions by different Commonwealth entities in shared policy areas. For example, over time, it is anticipated that good-quality data will allow for links to be made between related results in employment, education and health.70

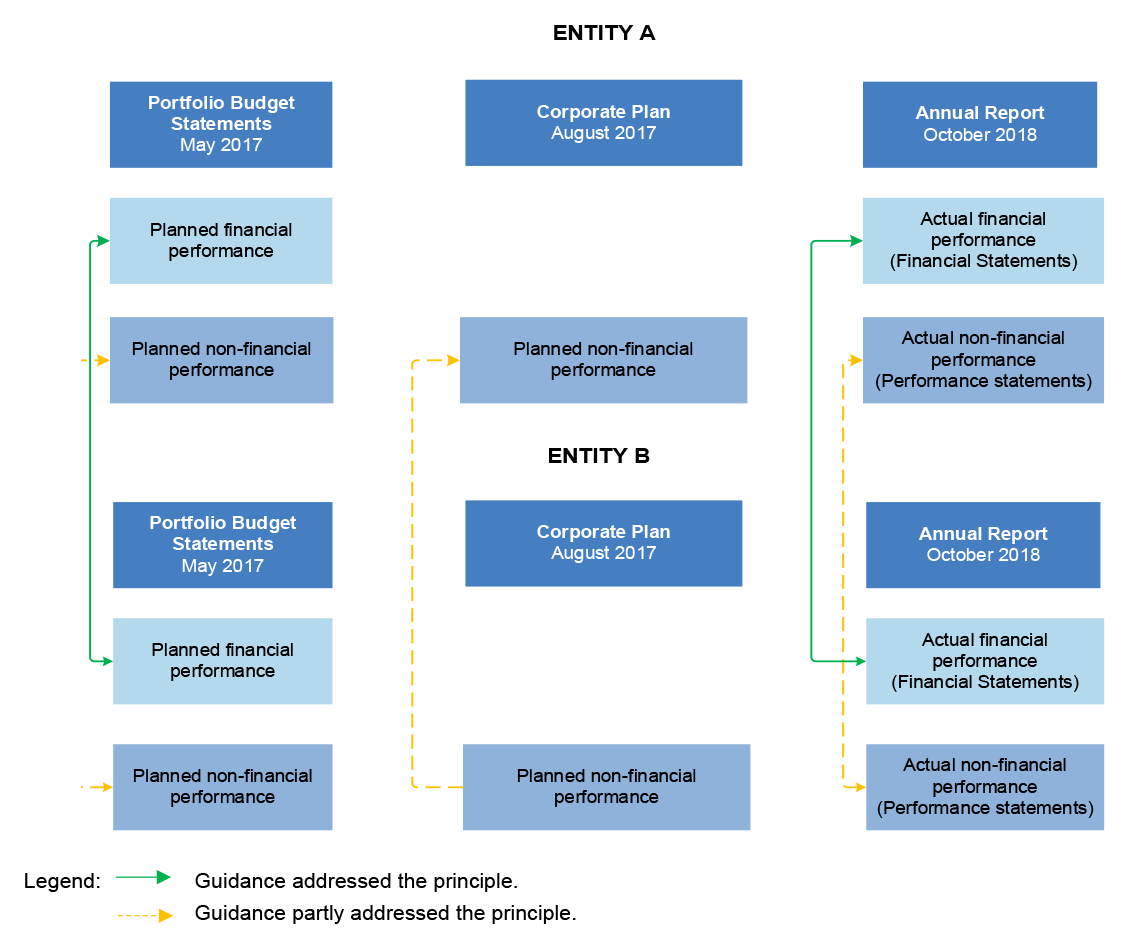

2.36 Figure 2.4 illustrates that Finance guidance had partly established the clear read principle to support comparable performance information between entities. Figure 2.4 also identifies areas for improvement to the guidance, specifically in respect to:

- comparing planned and actual non-financial performance between entities (see the corporate plan and annual report yellow arrows); and

- comparing planned and actual delivery of ‘joined up’ or linked programs (see the PBS yellow arrow).

Figure 2.4: Clear read between Commonwealth entities’ reporting (2017–18)

Source: ANAO analysis of Finance guidance.

2.37 The PGPA Act provides a basis for implementation of the clear read between entities by establishing requirements for entities to:

- prepare estimates for the budget statements as directed by the Finance Minister; and

- prepare financial statements that comply with the Australian Accounting Standards.

2.38 These requirements are supported by Finance guidance. This material includes templates to promote consistency across entities presentation of planned and actual financial performance in the PBS and audited financial statements.

2.39 Areas where the PGPA Rule and/or Finance guidance could be improved are:

- comparing planned and actual non-financial performance between entities; and

- comparing planned and actual delivery of ‘joined up’ programs.

Comparing planned and actual non-financial performance between entities

2.40 The PGPA Rule outlines the ‘matters’ that must be included in an entity’s corporate plan71 and performance statements72 and the specific requirements for annual reports.73 For example, an entity’s corporate plan must contain ‘matters’ relating to the following topics: ‘purpose’, ‘environment’, ‘risk oversight and management’, ‘capability’ and ‘performance’.74 The performance statements must contain results and analysis. The accountable authority has discretion over the presentation of these matters.

2.41 Finance’s guidance references the benefits of entities publishing non-financial performance information which allows the audience (the Parliament and the public) to compare the performance of different Commonwealth entities, in particular for shared outcomes. The guidance does not provide examples of how entities may achieve this comparability.

2.42 Templates (included in Finance guidance for PBSs and annual reports) are intended to aid consistency in presentation between entities. The guidance for annual reports states that if entities depart from the suggested structure they ‘should be prepared to explain their reasons for doing so.’ Guidance for performance statements and corporate plans is less prescriptive. Using a suggested format for performance statements to ‘…enable presentation in a consistent form by entities’ is encouraged by Finance in its guidance75, while also advising that the corporate plan ‘is not obliged to follow the structure of the PGPA rule’.76

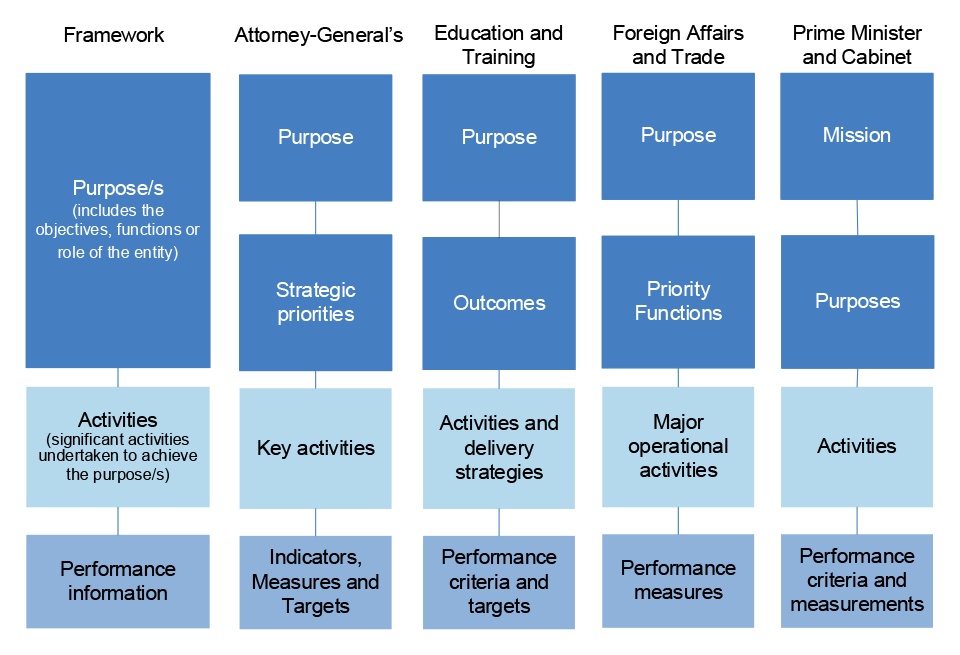

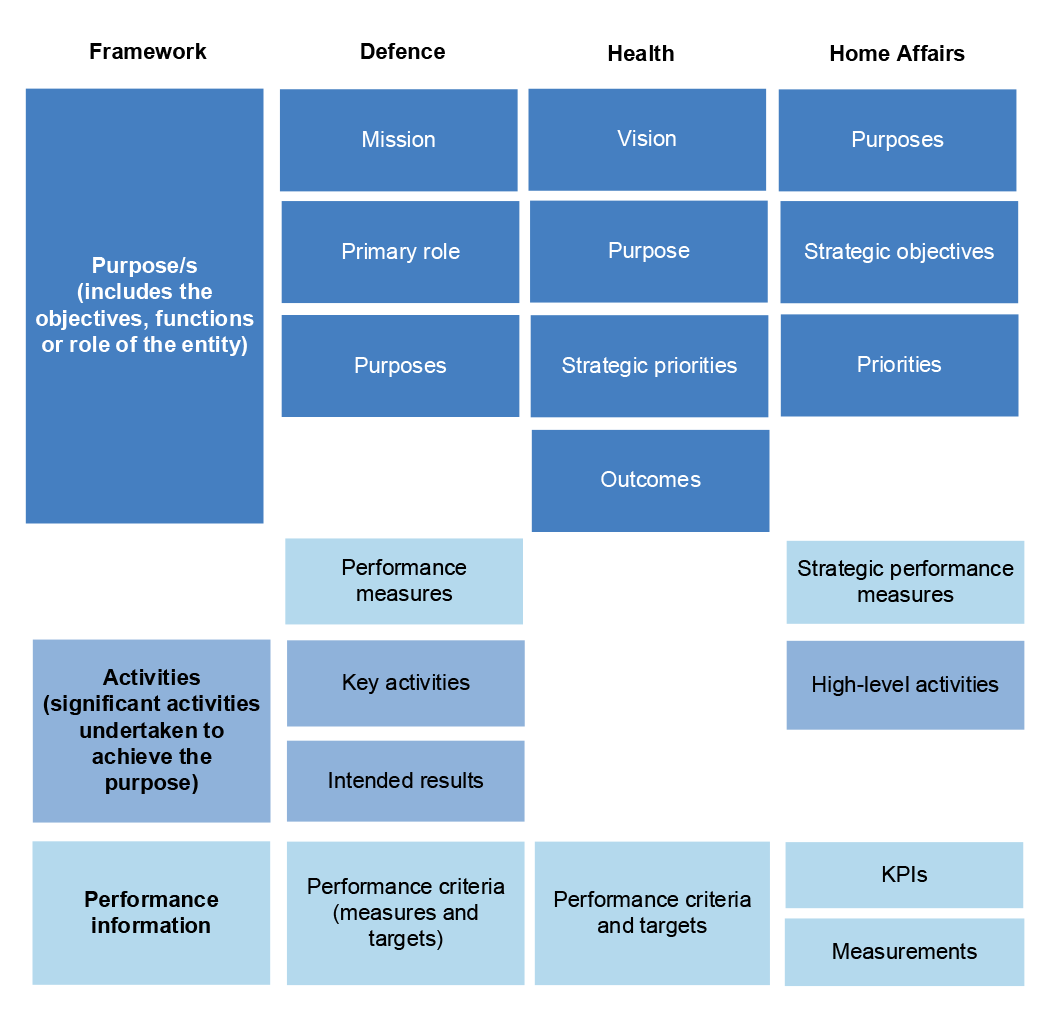

2.43 The ability to compare information across entities by the Parliament and the public has been identified as an issue by the JCPAA.77 The ANAO has also commented in previous audit reports on the variability in entities’ labelling of corporate plan elements — namely purposes and activities — and the impact of this on the comparability of corporate plans across entities.78 This variability is illustrated in Figure 2.5, which is drawn from a previous audit and shows that an entity’s purpose may be its objectives, functions or role — a situation which may reduce the comparability of planned and actual non-financial performance between entities. The issue is compounded when attempting to compare actual performance, as entities structure their performance statements (which report on entity performance) to reflect the corporate plan (which addresses anticipated performance).

Figure 2.5: Comparison of corporate plan elements of selected departments

Source: Auditor-General Report No. 17 2018–19 Implementation of the Annual Performance Statements Requirements 2017–18, December 2018.

Comparing planned and actual delivery of ‘joined up’ programs

2.44 In Report 453, the JCPAA identified ‘the ability to clearly communicate the performance of co-delivered or ‘joined-up’ programs — those that are managed by multiple government entities’ — as an area for improvement in achieving a clear read of entity reporting.79 The Finance Secretary’s Direction requires entities to report ‘links with the programs and outcomes of other entities’. Finance advised the JCPAA that the direction was intended to provide:

… a useful map that helps senators and members pull the drawstrings together through all PBSs so that they see how government activities are being funded in a particular area.80

2.45 Finance guidance relating to preparation of the PBS provides limited direction to entities as to how to identify these program links81, and entities have incorrectly interpreted the requirement. For example, the Department of Defence’s 2017–18 PBS lists Finance’s Program 1.4 Insurance and Risk Management as a ‘linked program’ that contributes to the department’s achievement of Outcome 2. This contribution is noted as ‘working with the Department of Finance to ensure Commonwealth assets are adequately insured and where necessary claims are made in accordance with Commonwealth guidelines and policy’.82 As all Commonwealth entities engage with Finance in this way, it is not clear how Defence highlighting this as a ‘linked program’ in the PBS demonstrates the expectation expressed by the JCPAA in paragraph 2.44 about co-delivered or joined-up programs.

2.46 Further, there is no requirement in the PGPA Rule or the Finance Secretary’s Direction for the linked programs presented in an entity’s PBS to also be: reflected in the other relevant entity’s PBS; presented in the corporate plan; or reported against in the annual report.83 In the absence of such information relating to linked programs, the user of performance documents can be left uncertain as to the impact of other entities’ contributions outlined in an entity’s PBS. Finance guidance does not address these matters.

Recommendation no.2

2.47 The Department of Finance amends the:

- Finance Secretary’s Direction to require a linked program presented in an entity’s Portfolio Budget Statements to also be reflected in the linked entity’s, or entities’, Portfolio Budget Statements; and

- corporate planning and annual report requirements to require entities to report on linked programs that were presented in the Portfolio Budget Statements.

Department of Finance response: Noted.

2.48 Amendments to the Finance Secretary Direction and corporate plan and annual report requirements require consideration by Government and the endorsement of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).

Has Finance monitored implementation of the clear read principle by entities?

Finance has undertaken monitoring and review activities, including assessments of the compliance and quality of entities’ performance reporting documents, but has not yet established an ongoing evaluation initiative as recommended by the JCPAA in Report 453: Development of the Commonwealth Performance Framework (Recommendation 3), and agreed to by the Government. Finance is taking steps to address Recommendation 4 made in JCPAA Report 469: Commonwealth Performance Framework (December 2017), relating to a more comprehensive monitoring and evaluation program for the ongoing implementation of the Commonwealth Performance Framework.

Finance has communicated the broad learnings from its monitoring activities through lessons learned papers and communities of practice events. Further, Finance has provided feedback to entities when requested, and has launched transparency.gov.au, which is intended to facilitate comparisons of data between government entities. There remain opportunities for Finance to further support implementation of the clear read principle by: advising entities of the outcomes of its assessments of entity reports; maintaining records of the advice provided; and monitoring the effectiveness of its advisory activities.

Monitoring the implementation of the enhanced performance framework

2.49 During the development of the performance framework, the JCPAA noted that it ‘wishes to see a clear and ongoing commitment by Finance for a central monitoring, reporting and evaluation initiative’ and that ‘this should provide a focal point for quality assurance, compliance assessment, identification of improvement activities and collection of data in support of the independent review [of the PGPA Act and Rule]’.84 The JCPAA recommended that Finance: