Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Commonwealth Environmental Watering Activities

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office’s administration of environmental water holdings.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Murray–Darling Basin (the Basin) is an area of national environmental, economic and social significance. The Basin comprises Australia’s three longest rivers—the Darling, the Murray and the Murrumbidgee—and nationally and internationally significant wetlands, billabongs and floodplains. The Basin covers one-seventh of Australia’s land mass and extends across four states—Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia (the Basin states)—and the Australian Capital Territory. Thirty-nine per cent of the national income derived from agricultural production is generated in the Basin, and it is home to over two million people.1

2. Throughout much of the twentieth century, infrastructure was constructed and water resources were allocated within the Murray–Darling Basin for irrigation, livestock and human consumption that disrupted the natural flows of the river system. It is now recognised that irrigation infrastructure and an over-allocation of water for consumptive use are having unintended environmental consequences.

3. In recent years there have been a number of reforms aimed at improving the management of water resources and addressing the imbalance between consumptive and environmental water use in the Basin. Major reforms include the:

- passage of the Water Act 2007 on 3 March 2008, which established the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH) and the Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA)2;

- production, implementation and enforcement of the first Basin-wide water sharing and management Plan (the Basin Plan) by the MDBA3; and

- progressive acquisition of water entitlements by the Commonwealth for use by the CEWH to water environmental assets in the Basin.4 The water entitlements under management by the CEWH, as at February 2013, were valued by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPaC) at $1.89 billion.5

Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder

4. The functions of the CEWH include managing Commonwealth environmental water holdings (that is, water entitlements) to make water available for the purpose of protecting and restoring areas of environmental significance within the Basin (including water courses, wetlands and floodplains) so as to give effect to relevant international agreements.6 The CEWH is also required to perform functions and exercise powers in a way that is consistent with the Environmental Watering Plan (within the Basin Plan) and the Basin-wide environmental watering strategy (to be developed by the MDBA).7 The CEWH’s various obligations contained in the Basin Plan are expected to be implemented over the short, medium and/or long term.

5. The CEWH’s environmental watering function is a relatively new area of Commonwealth activity, and does not have an international equivalent or precedent. The management and use of the CEWH’s portfolio of water holdings occurs within the complex sets of Basin system management rules established and regulated by the Basin states. The Basin system management rules were designed primarily for irrigation purposes to extract water from the river system. In contrast, environmental water generally contributes to enhanced river flows and the inundation of neighbouring wetlands and floodplains. Consequently, current Basin rules do not always facilitate the CEWH’s intended watering activities, and can sometimes complicate or inhibit their execution. Within this context, the effective discharge of the environmental watering function requires the CEWH to:

- determine the environmental assets to water and the quantity of environmental water to use, having regard to Basin conditions and the views of key stakeholders;

- ensure that delivery partners and/or river operators8 deliver environmental water as intended, which generally occurs through controlled releases from dams, weirs and barrages; and

- monitor and report on the ecological results of its water deliveries9 and the achievement of its legislated objective of protecting and restoring environmental assets in the Murray–Darling Basin.

6. The Government appointed a senior executive service officer from the Water Group within DSEWPaC to perform the role of the CEWH. The CEWH is currently supported by approximately 57 staff across two branches, which are known collectively as the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office (CEWO).10 The office operates as a distinct unit within DSEWPaC, with a current budget of $33 million in 2012–13 (over a third of which relates to the cost of holding water entitlements and delivery fees and charges). The CEWO is supported by committees of external advisors, that provide advice in relation to scientific and stakeholder issues.11

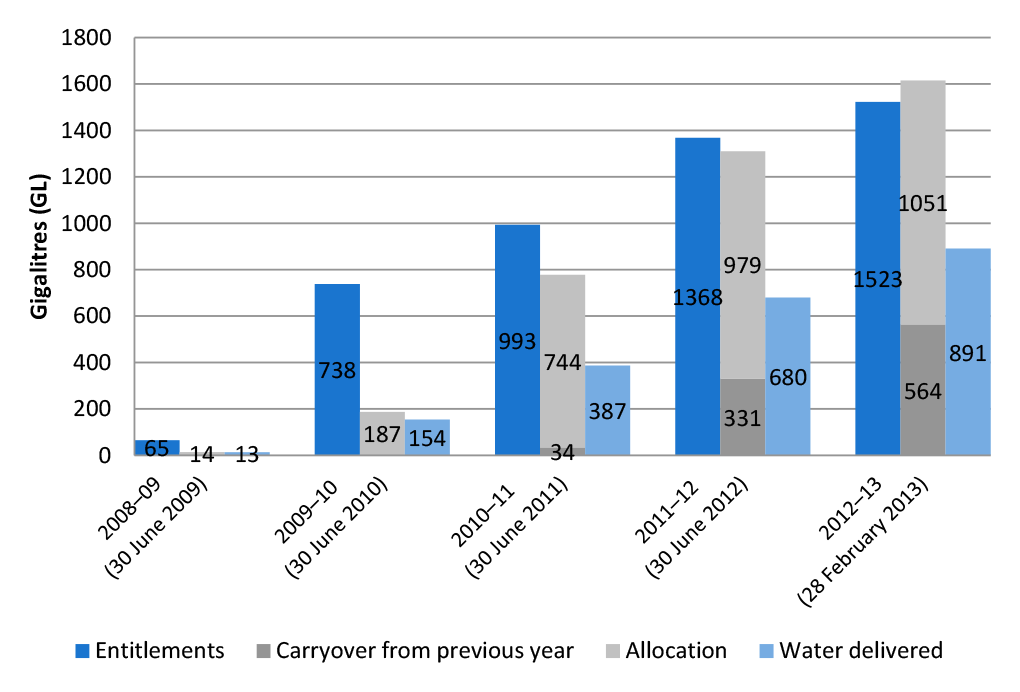

7. As at 28 February 2013, the Commonwealth held water entitlements totalling 1523 gigalitres/year12 (GL/yr) in 17 of the 19 catchments across the Basin, which equates to between 35 and 42 per cent of the CEWH’s anticipated final entitlement holdings.13 Since 2010–11, the CEWH has received increasing water allocations because of a significant growth in the CEWH’s water entitlements and generally wetter catchment conditions.14 As at 28 February 2013, 2124 GL of Commonwealth environmental water has been delivered to a range of environmental assets across the Basin since the CEWH’s establishment. Notwithstanding this activity to date, the CEWH’s current water holdings represent only a small proportion of streamflows throughout the Basin (less than six per cent of an average year’s inflows). Figure S1 illustrates the quantity of Commonwealth-held water entitlements, annual water allocations and water delivered to environmental assets between 1 July 2008 and 28 February 2013.

Figure S1 Availability and use of Commonwealth water holdings for the period from July 2008 to February 2013

Source: CEWO.

Note: Carryover represents unused water allocations in one year that have been brought forward (or carried over) for use in the following year.

Audit objectives and scope

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office’s administration of environmental water holdings.

9. The audit examined whether the CEWO’s:

- governance arrangements are appropriate to effectively manage and report on the CEWO’s environmental watering activities;

- engagement of all relevant stakeholders effectively facilitates the management of the CEWO’s environmental watering activities;

- arrangements to plan and target available Commonwealth environmental water at priority environmental assets are effective;

- arrangements to deliver Commonwealth environmental water to the designated environmental assets are effective and timely; and

- monitoring and evaluation activities effectively identify the outcomes achieved from the CEWO’s environmental watering activities, and influence future water use decisions.

Overall conclusion

10. The environmental watering function of the CEWH is a relatively new area of Commonwealth activity and a key element of the reforms introduced by the Commonwealth to address the imbalance between consumptive and environmental water use in the Basin. In its five years of operation, the CEWH has accumulated the largest holding of water entitlements in the Basin, currently valued at $1.89 billion. The CEWO, which supports the CEWH, has developed and continues to refine environmental watering frameworks, policies and practices to manage and use water entitlements within a complex set of Basin system management rules.

11. There are a wide range of stakeholders within and outside the Basin that are involved in, or have an interest in, the effective use of, and the environmental outcomes achieved from, Commonwealth-held water entitlements. The CEWO relies on its delivery partners and river operators to deliver Commonwealth environmental water, while avoiding potential adverse stakeholder impacts, such as the inadvertent flooding of private land. With the assistance of delivery partners and river operators, the CEWO has delivered over 2000 GL of water to a range of environmental assets across the Basin since the commencement of the first watering action in March 2009.

12. Overall, the CEWO has developed and continues to strengthen its arrangements to support the effective administration of the CEWH’s environmental watering function. The CEWO’s water use planning and decision-making approach is sound and appropriately underpinned by an assessment framework that is mostly applied as intended. The CEWO has established appropriate water delivery arrangements with delivery partners that resulted in the delivery of environmental water to its intended destinations, while managing water delivery risks and issues.

13. The CEWO’s environmental watering frameworks have evolved and continue to mature. The CEWO is preparing to make changes to its key water use guidance materials and introduce additional reporting to meet the requirements of the recently introduced Basin Plan. To enhance its longer-term management of the water holdings portfolio, the CEWO is also developing a framework to guide the trade of water entitlements and allocations, and intends to introduce multi-year water use planning to complement the existing annual planning approach.

14. The CEWO has made environmental watering information broadly available to interested parties and has progressively established productive relationships with various stakeholder groups, including regional and local bodies, delivery partners and the MDBA. The CEWO is continuing to enhance its engagement with stakeholders on its environmental watering function by the recent establishment of a stakeholder register, and through activities such as the intended employment of local engagement officers in key locations across the Basin. Given the diverse interests and involvement of the different stakeholder groups in the CEWO’s watering activities, there remains scope to better target stakeholder communications activities.

15. In the absence of a long-term monitoring and evaluation strategy, the CEWO has adopted a measured approach to short-term ecological monitoring and evaluation that is based on delivery partner monitoring activities and detailed studies at key locations where Commonwealth environmental water has been delivered. Short-term results reported by the CEWO include: sustaining wetland and native plant refuges during the drought prior to 2010; improving water quality to provide refuges for native fish; and supporting native bird and fish breeding. However, it is difficult to apportion the outcomes achieved from Commonwealth environmental water from that of total river flows.

16. To measure the intermediate and longer-term achievements from the use of environmental water, the CEWO is currently developing a strategy to implement its monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement (MERI) process from July 2014. The adoption of the MERI process will better position the CEWO to establish meaningful key performance indicators and demonstrate the environmental outcomes of watering activities and, ultimately, the extent to which water holdings have been used to protect and restore the Basin’s environmental assets.

17. While the ANAO has not made any recommendations as the CEWO’s strategies for managing environmental water are generally sound, a number of suggestions have been made in the report to enhance the CEWO’s current approach to administering the environmental watering function. In particular, a strong focus on the establishment of the MERI process will be necessary to position the CEWO to report on the extent to which its use of environmental water has contributed to protecting and restoring the environmental assets of the Murray–Darling Basin.

Key findings by chapter

Governance arrangements for environmental water use (Chapter 2)

18. The administrative arrangements underpinning the environmental watering function have been progressively strengthened and enhanced over time. Since December 2011, the CEWH’s responsibilities have been exclusively focused on the environmental watering function.15 The number of staff supporting the CEWH’s operations has increased over time in line with the accumulation of entitlements and increased environmental watering activity. The CEWO has effectively engaged with the Environmental Water Scientific Advisory Panel (EWSAP)16 to assist with the development of: environmental watering frameworks, water use plans and actions; and monitoring and evaluation activities. The CEWO has also recently established a stakeholder reference panel, and there are plans in place to establish an advisory council to provide advice on governance issues.

19. While there were weaknesses in early risk management approaches, the CEWO has progressively strengthened its approach to managing the risks associated with the effective use of Commonwealth environmental water. The early risk assessments were not formally endorsed or regularly updated and the monthly risk summaries varied substantially in their coverage from month-to-month. In January 2012, the CEWO engaged the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS) to identify and assess the sources of CEWO’s strategic, legal and governance risks and identify appropriate treatments. The detailed assessment, finalised in June 2012, indicated that risk treatments could reduce the ratings of most risk sources to ‘medium’ or ‘low’. While the CEWO is progressively implementing the proposed risk treatments, the implementation of treatments for some risks has been delayed.

20. The CEWO uses a hierarchy of plans (business, branch and section) to support and guide its operations. While the CEWO’s plans contain relevant information that assists with the execution of the CEWO’s environmental watering function, their usefulness would be improved through: a greater focus on the links between activities and outcomes; an increased alignment of their structure and content; and routine reviews of performance against the plans during the year.

21. There is considerable public interest in the activities and performance of the CEWO, with many stakeholders seeking clear and demonstrable benefits and outcomes from the use of Commonwealth-held water entitlements. The CEWO’s annual performance reporting, through the Portfolio Budget Statements, annual reports and outcomes reports, is confined to its activities, outputs and early ecological outcomes from particular watering actions. As previously mentioned, short-term results reported by the CEWO in recent annual outcomes reports include: sustaining wetland and native plant refuges during the drought prior to 2010; improving water quality to provide refuges for native fish; and supporting native bird and fish breeding. Establishing the full impact of Commonwealth environmental watering activities has, however, been challenging as:

- the CEWO’s water represented a smaller proportion of total river flows during the very wet Basin conditions in 2010–11 and 2011–12; and

- a number of third-party monitoring activities and studies referenced by the CEWO in its outcomes reports have not attempted to separately identify the outcomes from Commonwealth environmental water from that of total river flows.

22. The CEWO considers that its implementation of the MERI strategy, from July 2014, will allow it to better demonstrate the intermediate and longer-term ecological results achieved across the Basin from its environmental watering function.

Stakeholder engagement (Chapter 3)

23. In November 2010, the CEWO engaged a consultant to develop a communications strategy to guide its stakeholder engagement activities. The CEWO used the consultant’s draft strategy to inform the development of a stakeholder communications strategy, which was finalised in April 2012. While a useful starting point, there was limited coordination of the tasks and actions identified in the strategy to improve the CEWO’s stakeholder engagement. Most tasks have delivery dates that are either ‘ongoing’ or ‘progressive’ making monitoring implementation difficult. Further, the strategy is not underpinned by an assessment of stakeholder engagement needs, which would help to improve the effectiveness of the CEWO’s stakeholder engagement activities.

24. The CEWO has identified, through its stakeholder communications strategy, the importance of establishing a comprehensive register of environmental watering stakeholders. The stakeholder register, which was originally scheduled for completion in April 2012, was finalised in March 2013. The stakeholder register contains the names and most of the contact details for 683 stakeholders (which had been classified into 20 different stakeholder types, and included 643 representatives from 290 organisations and a further 40 stakeholders registered in an individual capacity). However, for a significant number of stakeholders, their catchments of interest and recent engagement history with the CEWO (including frequency of contact and issues discussed) has yet to be identified. Given the nature of the CEWO’s work and the importance and extent of stakeholder interest, there would be merit in reviewing the adequacy of the current register and the completeness and integrity of stakeholder data holdings.

25. To date, the CEWO has made information broadly available to interested parties—primarily through its website—and targeted stakeholder engagement activity to various stakeholder groups, including regional and local bodies, delivery partners and the MDBA. While the CEWO has increasingly gained access to existing regional and local groups and committees with waterways or environmental management responsibilities, the CEWO expects that its employment of local engagement officers across the Basin during 2013 will significantly enhance regional and local stakeholder engagement.

26. The CEWO also works well with its key delivery partners in respect to environmental planning, water delivery and monitoring and evaluation activities—which was consistent with the overall views expressed by delivery partners to the ANAO. The CEWO and the MDBA also informed the ANAO that they work together productively on areas of common interest, and each agency was satisfied with the breadth and depth of current engagement activity.

Water use planning (Chapter 4)

27. Given the variability of environmental and catchment conditions, a sound planning approach is necessary to help ensure that the CEWO is able to respond in an appropriate and timely manner. The CEWO has progressively established the elements of an integrated planning approach for environmental water use. Prior to 2011–12, water use planning was conducted throughout the year solely on a watering action by watering action basis. In 2011–12, the CEWO produced, for internal purposes, its first annual plans for each Basin catchment (or catchment group)—11 in total—that identified potential water use options at the start of the year. The following year the CEWO published its annual catchments plans (known as annual water use options documents) and also began to publish portfolio management statements for each catchment/catchment group, demonstrating to stakeholders a more strategic consideration of the relationship between the three potential uses of environmental water—that is, delivery/use, carryover and trade. In future years the CEWO intends to: introduce a framework to guide its trading of water entitlements and allocations between catchments and with third parties; and complement the current annual catchment planning approach with multi‑year water use plans covering up to five years.

28. The CEWO has developed appropriate water use planning and guidance tools to support the environmental watering function. Together, the water use framework, catchment delivery documents, environmental assets database17 and operational risk guidelines provide a sound basis for the CEWO to develop annual water use plans and assess the merits of individual watering proposals.

29. The CEWO’s annual water use options documents take account of internal and external information sources and identified potential water use options relevant to a range of future catchment conditions (from ‘extreme dry’ to ‘very wet’). The assessment framework underpinning the CEWO’s annual water use planning was mostly applied as intended. The exception was that identified water use options were not being prioritised during the planning process.

30. While the annual water use options documents have been refined and improved over time, the comprehensiveness of the assessment of the watering options varied between catchments. Although a total of 57 stakeholders were consulted during the development of the five 2012–13 annual water use options documents examined by the ANAO, only 32 were included on the draft stakeholder register in existence at the time. It was also unclear whether all key stakeholders had been consulted during the development of the annual water use options documents.

31. Overall, the 20 watering proposals18 examined by the ANAO (out of a total of 39) contained up-to-date information relevant to the CEWO’s proposed water use, including risk assessments, on which the CEWH makes decisions to undertake watering actions. However:

- the relationship between the watering proposals and the annual water use options documents was generally not clear;

- less than half of the watering proposals examined provided a rationale to indicate that their objectives were achievable using the intended watering approach; and

- less than half the watering proposals made specific mention of stakeholder consultation and, where mentioned, referred to the stakeholders’ involvement in a specific aspect of the proposals rather than the stakeholders’ views of the proposals overall.

32. Improvements to the watering proposal template and increased consistency in the template’s application, would improve the integration of watering proposals into the CEWO’s annual catchment planning approach. It would also allow the CEWO to better demonstrate the basis for the water use decisions being recommended to the CEWH for approval.

Water delivery arrangements (Chapter 5)

33. The CEWO has established appropriate arrangements with delivery partners and river operators to facilitate the delivery of environmental water throughout the Basin. A thorough risk assessment undertaken by the AGS noted that the delivery of Commonwealth environmental water through delivery partners significantly mitigates many of the risks that could arise during water delivery, including: compliance with applicable water, environment and heritage legislation; and negative impacts on people and property. Nevertheless, the AGS identified a number of additional treatments, which are being implemented by the CEWO, to further reduce the likelihood and consequence of the risks impacting directly on the CEWO. Notwithstanding the effectiveness of current delivery arrangements, there is scope to improve the assessment of the adequacy of the monitoring and measurement arrangements for each watering action, which would provide greater assurance over the effective delivery of Commonwealth environmental water.

34. Delivery partners monitor the CEWO’s water deliveries as they proceed (‘operational monitoring’), with the CEWO also monitoring the delivery of its water and other factors that could influence its watering actions (such as rainfall). The ANAO reviewed the 22 final delivery reports prepared by delivery partners at the conclusion of 2011–12 water deliveries. While the reports addressed any risks that materialised during the deliveries, the reports were of variable quality and completeness, with a number of reports submitted outside of the agreed timeframes. Overall, the reports provided only limited assurance that operational monitoring met the intended objectives. In particular:

- while water quantities and delivery dates were specified, many reports did not adequately describe the delivery partners’ monitoring/ measurement approach;

- reports rarely indicated explicitly that the quality of the environmental water delivered was within acceptable parameters; and

- initial ecological responses were generally missing or very briefly described. In addition, the absence of the watering action’s objectives from some reports inhibits a determination of the relevant ecological responses that should be observed.

35. An internal review of the operational monitoring practices of the CEWO and delivery partners, which was finalised in February 2013, identified shortcomings with current practices—many of which broadly align with the ANAO’s findings. To address the identified shortcomings, the CEWO intends to: implement a standard framework to determine the operational requirements for watering actions; implement a consistent approach to storing operational monitoring data; and prepare a CEWO final operational monitoring report, incorporating operational monitoring data and the delivery partner’s final delivery report.

36. The CEWO has established a spreadsheet-based Water Holdings Register to manage the accounting and use of water entitlements and allocations. A 2012 review of a sample of water delivery transactions by DSEWPaC’s internal auditors has provided the CEWO with general assurance as to the integrity of the water transfer process. The review, however, identified some internal control weaknesses and non-compliance, which were similar to those found during the ANAO’s testing of 2011–12 water delivery documentation for the five catchments examined. The CEWO has since implemented improvements to business processes, recordkeeping and documentation recommended by the internal auditors. A new Water Holdings Register, which is expected to be implemented by the CEWO in early 2013–14, will help to strengthen the control over water holdings data.

37. The efficient delivery of the CEWO’s environmental water is affected by a range of natural (mostly topographical) and artificial (infrastructure and rules-based) impediments. While the Commonwealth and state governments have undertaken (and plan to undertake) initiatives to address many impediments (generally involving infrastructure works and property acquisitions), the CEWO can pursue changes to Basin system management rules to improve the efficient and effective use of Commonwealth environmental water. In this regard, the CEWO has:

- established water shepherding arrangements with the Queensland and NSW governments to protect its water from extraction by other consumptive entitlement holders in Basin catchments that lack water control infrastructure and public storage facilities19; and

- negotiated temporary rule changes within the River Murray system that, among other things, allowed CEWO water to flow in-stream from the Murray headwaters to the Lower Lakes in SA.

Monitoring and evaluation (Chapter 6)

38. In the absence of a formal monitoring and evaluation framework and strategy, the CEWO initially used delivery partners to monitor the short-term ecological outcomes from specific watering actions since the first CEWO water deliveries in 2009. In response to EWSAP’s concerns regarding monitoring and evaluation arrangements, the CEWO began to engage researchers (monitoring partners) to undertake detailed monitoring studies at key locations where Commonwealth environmental water has been delivered from mid-2011. These monitoring studies commonly involve sampling prior to, during and after the watering action to determine baseline values and changes in water quality, and populations/health of flora and fauna. The results of the four reports from monitoring partners received, accepted and published by the CEWO to date have also been summarised in its recent annual outcomes reports.

39. While the monitoring reports have addressed their monitoring objectives, the relationship between the monitoring objectives and the ecological outcomes achieved from the CEWO watering actions was not always clear. Monitoring reports that express clear conclusions on the achievement of watering action objectives would better place the CEWO to measure its performance and apply learnings to future watering actions.

40. From July 2014, the CEWO intends to change the focus of its ecological monitoring activities from an action-by-action basis to monitoring particular sites on a long-term basis using the MERI process.20 To this end, the CEWO finalised a framework document in May 2012 to guide the application of the MERI process to the environmental watering function (the MERI framework document). The principles, program logic and different levels of monitoring outlined in the MERI framework document provide a sound basis for the CEWO to: develop a strategy to implement the MERI process; support an assessment of its environmental watering function; and integrate its monitoring with the Basin-wide monitoring to be undertaken by the MDBA under the Basin Plan. The framework document also identified the seven sites within the Basin selected for long-term monitoring by the CEWO.21

41. In July 2012, the CEWO began work to develop a five-year strategy to implement the monitoring component of the MERI process (the MERI strategy) at a cost of $23.4 million. Although the implementation of the MERI strategy was originally scheduled to commence from July 2013, the strategy’s implementation has been delayed until July 2014 to allow more time to complete the strategy’s development. While the CEWO advised the CEWH that the MERI strategy development would be managed in accordance with DSEWPaC’s project management standards, a project plan was not endorsed until March 2013—some nine months into the strategy’s development and after key decisions had been taken. The delayed development of a comprehensive risk assessment and treatment plan as part of an endorsed project plan increased the risk to the successful development of the MERI strategy.

42. The approach to developing the strategy includes:

- the direct sourcing of a MERI advisor to provide high-level scientific, consultation and project management services to assist the CEWO to develop the MERI strategy (which occurred in October 2012);

- the development of an overall monitoring approach and site-specific monitoring requirements by the MERI advisor that takes into account consultations with stakeholders, including EWSAP, and the results of a peer review (February to October 2013);

- the selection (through open tender) and contracting of monitoring partners to monitor each site (scheduled for the end of July and October 2013, respectively); and

- the development of detailed site-specific monitoring plans by monitoring partners (scheduled for the end of February 2014).

43. The CEWO intends to select monitoring partners using a two-staged approach to develop (Stage 1) and implement (Stage 2) detailed site-specific monitoring plans. In the first stage, monitoring partners will be selected on the basis of their capacity to develop and deliver the long-term monitoring program. As detailed proposals will not be sought from prospective monitoring partners, the CEWO intends to assess the proposals’ value for money by examining the hourly or daily rates for proposed personnel and costings for the development of site-specific monitoring plans. Under the second stage, the CEWO will retain the right to approach other service providers where suitable arrangements to implement site-specific monitoring plans with Stage 1 monitoring partners cannot be negotiated. Given the early stage at which partners are being engaged and the level of uncertainty around future monitoring arrangements, this staged approach is reasonable.

Summary of agency response

44. DSEWPaC’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities notes the ANAO’s findings that the department’s strategies for managing environmental water are generally sound.

The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office has developed and strengthened its arrangements in line with the growth in the water holdings. While the report concludes the existing arrangements for the management of Commonwealth environmental water are appropriate, the department supports the suggestions made in the report to further strengthen the management of Commonwealth environmental water.

Footnotes

[1] Murray–Darling Basin Authority 2013, Explore the Basin: About the Basin, available from <http://www.mdba.gov.au/explore-the-basin/about-the-basin> [accessed 1 March 2013].

[2] The MDBA assumed responsibility for all of the functions of the former Murray–Darling Basin Commission.

[3] After a development period of some four years, the Basin Plan was adopted into law by the Australian Parliament on 22 November 2012. The Basin Plan provides a high-level framework that sets standards for the Commonwealth, Basin states and the MDBA to manage the Basin’s water resources in a coordinated and sustainable way in collaboration with the community.

[4] Water entitlements are a perpetual or ongoing entitlement by, or under, a law of a state to access a share of the water resources of a water sharing plan area.

[5] Water entitlement valuations fluctuate over time, reflecting movements in market prices. The current valuation of water entitlements takes into account impairment losses of $0.31 billion from the value of the water entitlements at the time of their acquisition. The current valuation of water entitlements does not take into account ancillary program expenditure associated with the acquisition of the entitlements (which includes expenditure on irrigation infrastructure improvements).

[6] Areas of environmental significance, defined as environmental assets, include water-dependent ecosystems, ecosystem services and sites with ecological significance. International agreements include intergovernmental treaties, conventions and agreements related to: wetlands of international importance (Ramsar agreement); the conservation of wildlife and habitats (Bonn Convention); biological diversity (Convention on Biological Diversity); and migratory birds (agreements with Japan, China and the Republic of Korea).

[7] Clause 8.03(1) of the Basin Plan.

[8] Delivery partners include: state and territory departments and agencies; private irrigation infrastructure operators; and catchment management authorities. River operators, which include state government authorities and the MDBA, control, operate and manage the water delivery infrastructure within the Basin.

[9] Ecological monitoring can involve impacts on aquatic and terrestrial vegetation, waterbirds, fish, frogs, tadpoles, insects and other invertebrates.

[10] Prior to the establishment of the CEWO in December 2011, the CEWH was supported by an environmental watering section or branch. For the purposes of the audit, the CEWO has been used exclusively to refer to the DSEWPaC staff supporting the CEWH.

[11] The CEWO intends to establish a further advisory committee to provide advice in relation to governance issues.

[12] One gigalitre equals 1000 megalitres or 1 000 000 000 litres.

[13] The CEWH’s anticipated final entitlement holdings were determined by reference to: the targets established under the Basin Plan for recovering water entitlements across the catchments of the Basin; the potential adjustments to the Basin Plan targets to account for the impacts of future environmental works and measures; and the further quantity of entitlements the Commonwealth has committed to acquire under the Water Amendment (Water for the Environment Special Account) Act 2013.

[14] State water management authorities allocate a specific volume of water to a water entitlement, usually expressed as a percentage of the entitlement, in a given water year or as specified within a water sharing plan. The ‘millennium drought’ (from 2000 to 2009–10) brought historically low water allocations against entitlements. Conversely, flooding within the Basin during 2010–11 and 2011–12 has seen water allocations against entitlements increase markedly.

[15] In the period from March 2008 to November 2011, the CEWH discharged duties as a division head in DSEWPaC that included departmental responsibilities other than the environmental watering function.

[16] EWSAP has been providing scientific advice to the CEWH and the CEWO since the Panel’s establishment in October 2008. EWSAP comprises scientists and experts in fields, such as hydrology, limnolgy, river operations management, river and floodplain ecology and management of aquatic ecosystems.

[17] The environmental assets database, jointly developed by the CEWO and the MDBA, records data of Basin environmental assets covering matters such as: environmental condition and significance; threatened flora and fauna; watering requirements and history; operational and ecological monitoring; and evaluation history and results.

[18] The CEWO uses a template to develop watering proposals throughout each year.

[19] Without these agreements, CEWO water delivered in-stream could trigger access thresholds to be exceeded downstream, which would otherwise allow downstream entitlement holders to extract the CEWO’s water for consumptive purposes.

[20] The MERI process provides a generic framework for monitoring, evaluating and reporting activities and improving the management of key environmental assets. The MERI process was developed in 2003 by evaluation researchers and applied in natural resource management programs in 2009 by the then Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

[21] The seven sites are: the Gwydir Wetlands (wetlands and floodplains); Lower Lachlan river system (in‑stream and on fringing wetlands); Murrumbidgee River (in-stream, on fringing wetlands, and floodplains); Edward–Wakool river system (in-stream and on fringing wetlands); Goulburn–Broken river system (in-stream and on fringing wetlands); Lower Murray (in-stream and on fringing wetlands); and Toorale Station (in stream and floodplains, as well as an indicator of upstream unregulated rivers).