Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Central Administration of Security Vetting

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to examine whether the Department of Defence provides an efficient and effective security vetting service for Australian Government entities through the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency.

Summary

Introduction

1. Security vetting involves the assessment of an individual’s suitability to hold a security clearance at a particular level. Australian Government employees and contractors require a security clearance to access classified resources, which can relate to Australia’s national security, economic and other interests. The security vetting and clearance process is an important risk mitigation activity intended to protect the national interest, which can also affect an individual’s employment and the business operations of entities if not managed effectively or in a timely manner.

2. Australian Government entities managed their own security vetting for employees and contractors until the end of September 2010. The Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) was then established within the Department of Defence (Defence) from 1 October 2010 to centrally administer personnel security vetting on behalf of Australian Government entities.1 Centralised vetting was expected to result in: a single security clearance for each employee or contractor, recognised across government entities; a more efficient and cost-effective security vetting service; and cost savings of $5.3 million per year.

3. Most government entities must use AGSVA’s security vetting service for personnel that require a clearance.2 AGSVA’s vetting process involves enquiry into, and corroboration of, a person’s background, character and personal values, before a decision is made by AGSVA on whether to grant or continue a clearance. AGSVA has management responsibilities for some 349 000 active Australian Government security clearances, and issued over 33 000 clearances in 2013–14.

Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA)

4. AGSVA forms part of Defence’s Intelligence and Security Group. The agency includes: an executive group in Canberra; a National Coordination Centre in Brisbane; a Vetting Support Centre in Adelaide; and regional offices in each state and territory, which manage security vetting assessments and determinations. As at 30 March 2015, AGSVA employed 272 Australian Public Service (APS) staff, including some 130 Assessing Officers (AOs). AGSVA also manages a contracted workforce of over 300 personnel, who provide administrative support, and conduct vetting and psychological assessments. AGSVA’s Industry Vetting Panel (IVP) comprises 21 companies and approximately 200 AOs, who complete around half of AGSVA’s vetting assessments.

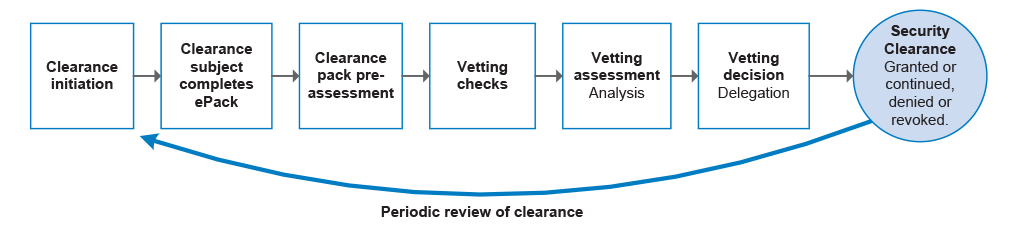

5. Figure S.1 illustrates AGSVA’s security vetting process. Each individual subject to the vetting process provides mandatory information using AGSVA’s ePack system, and sends AGSVA supporting documentation. AGSVA then assesses the submitted information for completeness, and initiates or conducts a range of vetting checks, such as referee checks, a police records check and a financial history check. An AO analyses the information provided by the individual and the results of checks undertaken, and requests further information and conducts interviews as necessary. The AO then makes a recommendation on the suitability of the individual to hold a clearance at the requested level to an AGSVA Delegate, who reviews the case and makes a decision. AGSVA charges government entities (other than Defence) on a fee-for-service basis for each clearance request.3

Figure S.1: Overview of the security vetting process

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA documentation and processes.

Personnel security policy and clearance levels

6. A decision about granting a security clearance should be made in accordance with the standards identified in the Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF).4 Vetting assessments and decisions are to take into account all available and reliable information, whether favourable or unfavourable, about the clearance subject. The Personnel Security Core Policy states that: ‘Any doubt about the suitability of a clearance subject is to be resolved in favour of the national interest.’5

7. The PSPF identifies four levels of security clearance: Baseline, Negative Vetting 1 (NV1), Negative Vetting 2 (NV2) and Positive Vetting (PV). Higher level clearances involve additional vetting checks and allow personnel to access increasing levels of classified resources. Under the PSPF, AGSVA is responsible for initiating periodic reviews of security clearances at set intervals, ranging from 15 years for Baseline to five years for PV clearances.

8. In late 2014, the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) introduced a number of reforms to personnel security policy. The reforms are intended to clarify the responsibilities of government entities, direct resources to the areas of greatest risk and further strengthen the assessment of a person’s ongoing suitability to hold a security clearance. The reforms were initiated in response to high profile international security incidents6, which highlighted the potential consequences of inadequate security vetting and employer monitoring and reporting.

Audit objectives and scope

9. The audit objective was to examine whether the Department of Defence (Defence) provides an efficient and effective security vetting service for Australian Government entities through the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA).

10. The high-level criteria used to assess AGSVA’s performance were:

- AGSVA’s establishment was well planned and supported by an implementation strategy that enabled the agency to undertake the responsibilities conferred upon it;

- AGSVA has adequate guidelines, procedures and systems in place to support the security clearance process;

- AGSVA’s security clearance policies and procedures comply with Australian Government policy, including the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF);

- AGSVA identifies areas for improvement in security clearance arrangements and implements strategies to enhance performance; and

- Defence monitors, evaluates and reports on the efficiency and effectiveness of AGSVA’s security vetting service.7

Overall conclusion

11. Security vetting involves the assessment of an individual’s suitability to hold a security clearance at a particular level. Australian Government employees and contractors require a security clearance to access classified resources, which can relate to Australia’s national security, economic and other interests; and security vetting of individuals in positions of trust is an important risk mitigation activity for the protection of such government resources.

12. In November 2009, the then Government decided to establish AGSVA within Defence to perform security vetting for most Australian Government entities on a fee-for-service basis, replacing a decentralised system in which individual entities managed personnel security vetting based on Australian Government policy requirements. The Government expected that centralised vetting would: result in a more efficient vetting process; improve the consistency of vetting practices; and deliver $5.3 million in annual cost savings.

13. Overall, the performance of the centralised vetting system established in October 2010 has been mixed, and key Australian Government expectations relating to improved efficiency and cost savings have not been realised. AGSVA was not ready to effectively provide whole-of-government vetting services in 2010 due to inadequate implementation planning, risk management and resourcing. While Defence has made progress since 2012 in its implementation of centralised vetting—by strengthening the management of vetting work, documenting its vetting procedures and applying additional human resources—AGSVA continues to fall well short of fully meeting its vetting responsibilities in a timely manner, and anticipated savings have been eroded. There is scope for Defence to develop a clear pathway to strengthen AGSVA’s capacity to deliver services, and improve quality control over aspects of vetting practice and decision-making.

14. The mixed performance of centralised vetting has its roots in an inadequate policy proposal developed in 2009 by AGD in consultation with Defence and the then Department of Finance and Deregulation, which did not effectively assess Defence’s capacity to deliver whole-of-government services with the resources proposed. AGSVA commenced operations on the back foot, with significantly reduced vetting resources compared to those previously deployed across government, and without an appropriate management structure, documented procedures and adequate ICT systems. The failure to identify and address key risks during the policy development and implementation planning phases has had lasting consequences for AGSVA’s delivery of vetting services.8

15. Over time, Defence has attempted to overcome identified shortcomings and improve AGSVA’s performance. AGSVA’s APS staffing level has been increased, as has utilisation of contractors to conduct security clearance assessments. These additional resources have been provided to AGSVA from within Defence’s overall budget, eroding the savings originally anticipated from centralised vetting. Other key changes included: the introduction from 2012 of a revised management structure incorporating more appropriate governance arrangements; implementation of a centrally managed suite of procedural documentation; and the accreditation of AGSVA’s Quality Management System to an internationally recognised standard in April 2014.9 Notwithstanding these changes, AGSVA still needs to improve the level of assurance over IVP contractors’ work practices through a targeted audit program, and strengthen quality control over vetting decisions through a review process. These measures would help address inconsistencies in vetting assessment processes identified by AGSVA, and concerns raised by some stakeholders about the rigour of AGSVA’s assessment process.

16. Defence has invested over $37 million since 2008 in upgrading AGSVA’s core ICT systems—ePack and the Personnel Security Assessment Management System (PSAMS)—expecting that the upgrades would make a marked difference to vetting performance. While the upgraded systems help ensure the completion of mandatory vetting tasks and compliance with policy requirements, they still lack reliability and functionality. The ePack system remains a frustrating and difficult system for individual users to navigate, raising efficiency and productivity issues in the vetting process. Further, there is at times a reliance on inefficient hard copy documentation processes. PSAMS also does not support certain tasks performed by AGSVA as part of the ongoing management of clearances. Notwithstanding Defence’s substantial investment in PSAMS, the department formed the view in early 2014 that the system did not have the functionality needed for future vetting operations.

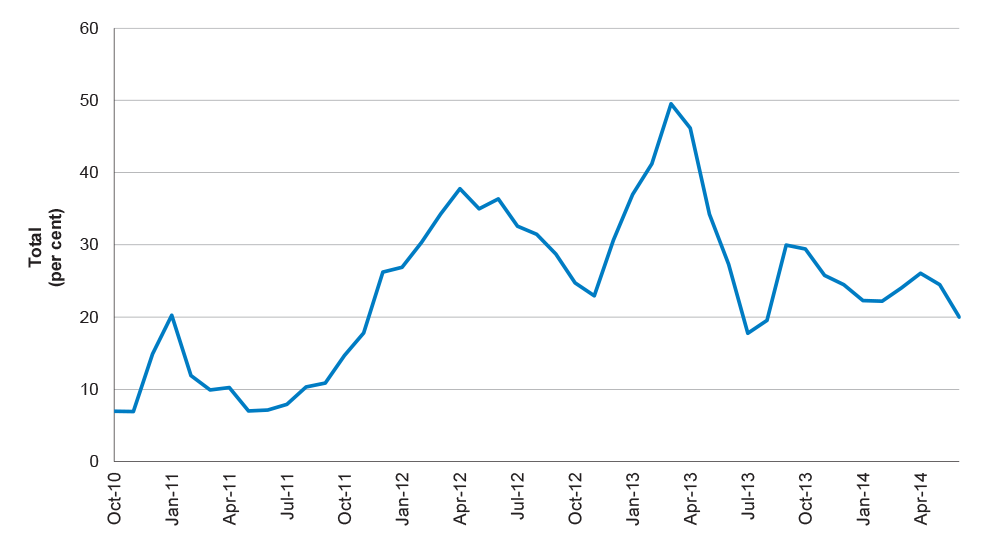

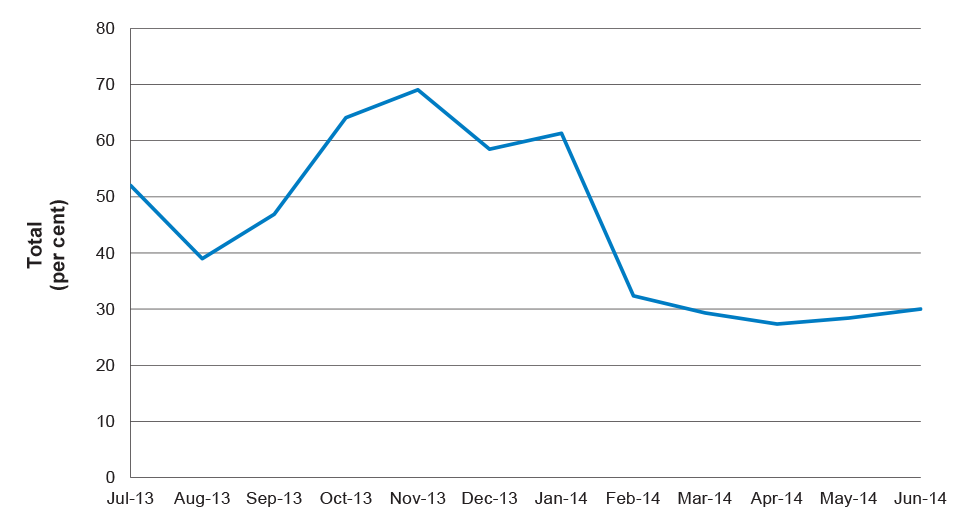

17. AGSVA has been unable to meet agreed benchmark timeframes for processing security clearances since 2010, and despite investments in people, systems and processes, there has been no noticeable improvement in the timeliness of clearance processing. In 2013–14, AGSVA completed 55 per cent of clearances within the relevant benchmark timeframe, compared to the target of 95 per cent. In March 2015, over 13 000 security clearances were overdue for revalidation—a process involving the assessment of individuals’ ongoing suitability to hold security clearances. The backlog is a consequence of AGSVA using available resources to prioritise the processing of initial clearances, so as to enable employees and contractors to start work in positions that require a security clearance. The significant backlog of revalidation work requires management attention at a time of heightened government concern about the threat posed by trusted insiders.10

18. A key lesson of this audit is that successful implementation of a large system-level reform should be based on sound analysis and include a comprehensive risk assessment.11 Such assessments enable government to make informed decisions on whether the reform is likely to succeed, resource requirements and the level of service which can be expected.12 In the case of centralised vetting, implementation planning and risk management were inadequate and many significant issues emerged after AGSVA commenced operations. While investments in AGSVA’s people and vetting processes have since been made, they have been of limited effectiveness in realising the expected benefits of centralised vetting.

19. Notwithstanding additional APS staff, increased utilisation of contractors and investment in ICT systems, AGSVA remains unable to meet whole-of-government vetting demand within agreed timeframes. Against this background, Defence should develop a pathway—including agreed strategies, targeted resources and a timetable—to improve its management of security vetting. Continued senior Defence management oversight, combined with a more disciplined management approach, is necessary until AGSVA’s performance levels reach agreed standards. The ANAO has made three recommendations intended to promote AGSVA’s delivery of more effective and timely vetting services. The recommendations involve Defence strengthening its quality assurance of vetting processes and decisions, and developing a pathway to achieve agreed timeframes for processing and revalidating security clearances.13

Key findings by chapter

Policy Advice and Implementation (Chapter 2)

20. The concept of centralised vetting for Australian Government entities was first raised in December 2007, and until September 2009, planning focused on the creation of a centralised vetting unit within AGD. AGD originally proposed to exempt Defence from the arrangement—which accounted for around half of all vetting activities in 2007–08—raising concerns within government about the coverage of centralised vetting and achievement of efficiencies. Defence subsequently agreed to host the centralised vetting unit by expanding its existing vetting operation to incorporate whole-of-government requirements. AGD developed a revised proposal on this basis, and in November 2009 the then Government agreed to centralise security vetting in Defence with limited exemptions. Centralised vetting was expected to increase efficiency in the vetting process, improve consistency in vetting practice, reduce delays in the transfer of clearances between entities and deliver cost savings of $5.3 million per year.

21. In a number of key areas, AGD’s revised proposal to establish a centralised vetting unit within Defence was not soundly based. The proposed staffing for the centralised vetting unit represented a 25 per cent reduction compared to the reported number of vetting staff across government in 2007–0814; and the proposed $6.5 million contractor budget represented a 59 per cent reduction on reported contractor costs across government.15 Further, the proposal did not consider potential risks relating to the overall reduction in resource levels; particularly how Defence would maintain vetting throughput and achieve anticipated savings. The proposal rated the overall implementation risk of centralised vetting as low on the basis that Defence already had systems and processes in place. However, Defence’s core vetting systems were undergoing critical upgrades to meet internal vetting requirements, and the department had also been expending significant funds on contractors to clear large clearance backlogs.16

22. Defence’s implementation of centralised vetting was under-resourced and AGSVA commenced operations without appropriate procedural documentation, or robust, fully functional ICT systems. AGSVA also inherited the former Defence Vetting Branch management structure which was not designed for whole-of-government work, and lacked appropriate governance and quality management arrangements. A succession of internal and external reviews conducted since AGSVA’s establishment have commented on AGSVA’s inability to meet expectations for efficient and effective whole-of-government security vetting, due to insufficient implementation planning, inadequate risk management and under-resourcing. In attempting to manage its workload and improve systems and processes, AGSVA’s APS staffing level increased from 228 employees in October 2010 to 272 by March 2015, and its expenditure on vetting services contractors was over $17 million in 2013–14. Overall, between 2011–12 and 2013–14, AGSVA’s expenditure was some 21 per cent higher than originally estimated in the November 2009 policy proposal. The additional funding was provided from within Defence’s overall budget and eroded the savings anticipated from centralised vetting.

23. To recover the cost of security vetting, Defence charges other government entities a fee for each security clearance they sponsor. The fees were introduced in 2010 and increased between 15 and 67 per cent in July 2014, indicating the charges had not been aligned with vetting costs for some time. Further, Defence did not commence charging its own contractors for security clearances until January 2015. Defence contractors could obtain a security clearance free of charge through Defence, whereas other government entities were charged for the contractor personnel they sponsored. Going forward, a more disciplined approach to the fee setting regime is required, including close tracking of vetting expenses and revenue, informing stakeholders about factors that influence vetting costs and ongoing review of charges. As the sole provider of vetting services to most government entities, there would also be benefit in AGSVA periodically reviewing its vetting methodologies, and benchmarking its activities against comparable systems to the extent practicable, with a view to identifying ways to improve efficiency and minimise charges for vetting services.

The Security Vetting Process (Chapter 3)

24. Since 2012, there have been improvements in AGSVA’s administrative arrangements, policies and procedures, including its overall approach to maintaining quality in vetting operations. AGSVA’s Quality Management System was accredited to an internationally recognised standard in April 201417, and includes security vetting policies and procedures, an internal quality audit program and quarterly management reviews. AGSVA conducted 14 internal quality audits in 2013 covering the breadth of activities carried out by its staff, which identified many areas for improvement.18 Going forward, AGSVA needs to look beyond the milestone of gaining accreditation of its Quality Management System, and continue to support the internal quality audit function as a means to identify problems and promote continuous improvement.

25. AGSVA’s security vetting process is well established and familiar to government entities that request clearances on a regular basis.19 The vetting process has evolved in response to the changing threat environment and advances in digital technology—AGD’s 2014 update of personnel security policy included additional declarations, financial history and digital footprint checks, and AGSVA is implementing these checks in consultation with AGD. However, in 2013–14, almost one-third of clearance cases were cancelled at some point during the vetting process, with AGSVA applying considerable resources to cases that were ultimately cancelled.20 The underlying causes of cancellations require further attention to help identify opportunities for improved efficiency.

26. Around 50 per cent of AGSVA’s security clearance assessments are completed by IVP contractors under a Deed of Agreement with Defence. AGSVA conducts an informal program of visits to IVP contractors’ premises, and IVP assessments are reviewed by an AGSVA Delegate as part of the decision-making process for each clearance. These arrangements provide relatively limited assurance as to whether the IVP contractors comply fully with personnel security policy and AGSVA’s procedures. AGSVA had planned to implement an IVP audit program in 2014, but this has been deferred to late 2015. Implementation of the planned audit program would provide additional assurance that IVP contractors have appropriate systems and processes in place, and adhere to relevant policy and legislation.21

27. Over time, AGSVA has denied a relatively small proportion of security clearances.22 AGSVA has advised that this reflects: clearance subjects having already been through employment screening processes; the cancellation of complex cases during the vetting process; and AGSVA’s obligation to apply the principle of procedural fairness, which can result in mitigation of identified security concerns.23 The low rate of clearance requests which are denied has raised a concern among some entities that security risks may not have been fully identified, or mitigated. In response to the ANAO’s September 2014 Questionnaire24, several entities also questioned the rigour of AGSVA’s assessment process. Further, an AGSVA internal quality audit in 2013 identified inconsistent additional checks at the vetting assessment and decision stages for similar clearance cases. In light of concerns expressed by stakeholders, and findings of the internal quality audit, Defence should implement a program of internal peer review of Delegate decisions, supplemented by periodic external independent quality assurance, to strengthen quality control over vetting decisions, promote consistent decision-making and strengthen confidence in the vetting process.

Management of Information Systems (Chapter 4)

28. AGSVA uses two primary information systems to process security clearances. The ePack system allows clearance subjects to complete and submit their security vetting packs through an online portal, and the system uploads clearance information directly to PSAMS.25 In May 2008, the PSAMS Refresh Project was approved to upgrade the ePack and PSAMS systems to improve the Defence security vetting process. At that time, the ePack upgrade was expected to be completed by June 2009 and PSAMS by March 2010 at a combined cost of $4.785 million.

29. The ePack upgrade (ePack2) was released in September 2010 at a cost of $5.627 million. However, ePack2 had a large number of defects26, resulting in many clearance subjects experiencing difficulty with the system. While AGSVA has subsequently completed a series of technical updates of ePack2, users of the system continue to experience useability, compatibility and stability issues. The ePack system is the public face of AGSVA, but remains a frustrating and difficult system for individual users to navigate. This raises efficiency and productivity issues for customer entities and the vetting process as a whole.

30. The PSAMS (PSAMS2) upgrade was eventually released in December 2012 at a cost of over $32 million.27 Defence documentation indicates that shortcomings in project planning, insufficient application of ICT expertise and major changes in project scope to deliver whole-of-government vetting functionality requirements, contributed to the substantial increase in costs. PSAMS2 is intended to support adherence to personnel security policy by not allowing vetting personnel to progress through the vetting process without completing mandatory tasks.28 However, the upgraded system has not delivered anticipated efficiencies. For example, there is at times a reliance on inefficient hard copy documentation processes. In addition, AGSVA’s Vetting Support Centre29 uses Microsoft Outlook to manage workflow due to limitations in the functionality of PSAMS. In February 2014, Defence identified the need for long-term and potentially significant investment in ICT solutions because PSAMS2 did not have the ‘functionality needed for the future’.30

31. AGSVA currently manages some 349 000 security clearances and is responsible for the security, availability and accuracy of sensitive clearance data. The ANAO reviewed AGSVA’s access control policies and procedures for Defence’s records management system, and found no formalised policy and inconsistent practices, including instances where staff members could access clearance records beyond their ‘need-to-know’. In February 2015, Defence assessed AGSVA’s electronic information risk profile and identified a number of gaps in the framework of internal controls and instances of control breakdown.31 Defence needs to strengthen its controls framework for the management of sensitive personnel information captured as part of the security vetting process.

Performance Monitoring and Reporting (Chapter 5)

32. The AGSVA Service Delivery Charter includes four Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that address different aspects of vetting service delivery. One of these KPIs measures the timeliness of AGSVA’s vetting process, with AGSVA aiming to complete 95 per cent of clearance cases within agreed benchmark timeframes. While this is a relevant measure of AGSVA’s efficiency in meeting customer demand, there is no apparent relationship between the 95 per cent target and the proportion of vetting cases that are complex, and therefore require additional information and review. The remaining KPIs do not measure the effectiveness of AGSVA’s service delivery to inform management decision making. Reflecting the weaknesses in the program KPIs, public reporting on AGSVA’s service delivery in the Defence Annual Report has been opaque, and has not conveyed the agency’s performance in delivering whole-of-government vetting services over time. There remains scope for Defence to improve the quality of performance measures and public reporting on AGSVA’s performance.

33. Since its inception in October 2010, AGSVA has been unable to meet its 95 per cent target for processing security clearances within benchmark times, with around 45 per cent of clearances in 2013–14 processed in timeframes exceeding the relevant benchmark. AGSVA has given priority to processing initial clearances to enable employees and contractors to start work in positions that require a security clearance, resulting in a backlog of some 13 000 clearance revalidations. Notwithstanding increases in staffing and contractor expenditure, and system upgrades since 2010, AGSVA has struggled to manage the demand for security vetting services. Against this background, Defence should develop a pathway—including agreed strategies, targeted resources and a timetable—to improve its performance against benchmark timeframes, and address the revalidation backlog at a time of heightened focus on the threat posed by trusted insiders.32

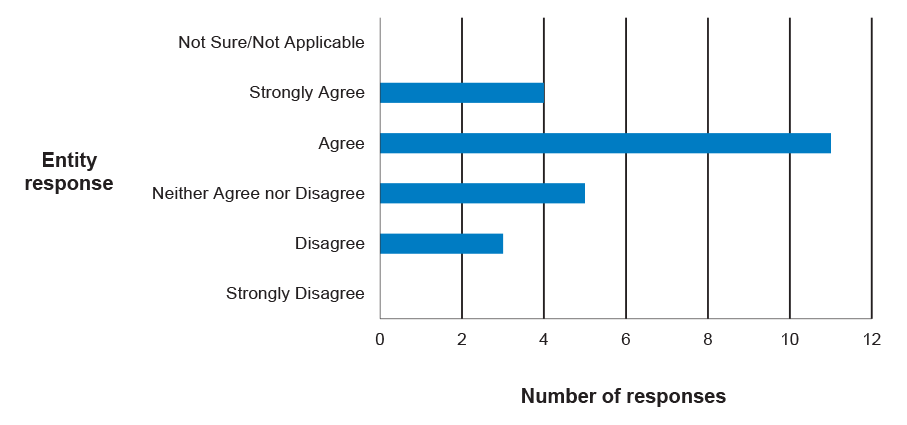

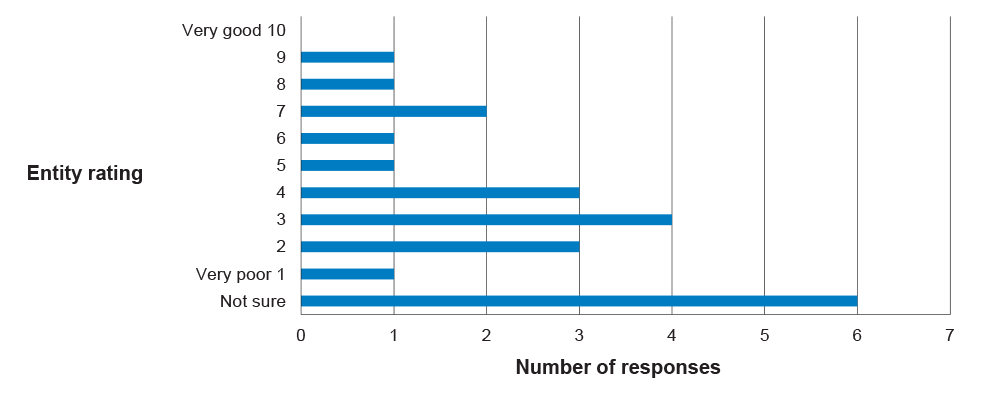

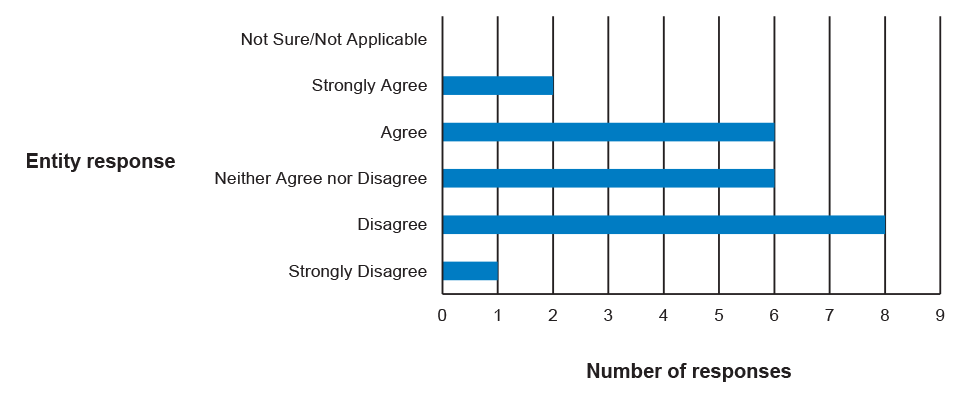

34. Twenty-three Australian Government entities provided feedback on AGSVA’s service delivery in response to the ANAO’s September 2014 Questionnaire. While 78 per cent of the respondents agreed that AGSVA’s vetting services had improved over the past two years, respondents also raised concerns about aspects of AGSVA’s performance, including the agency’s lack of communication about the status of complex cases and identified security concerns for clearance subjects. Effective ongoing management of clearances is dependent on communication and information sharing between the sponsoring entity and AGSVA, including where security concerns are identified such as past criminal behaviour. There would be benefit in AGSVA considering how best to provide feedback to the relevant entity on specific security concerns identified during the vetting process, to facilitate entities’ supervision of affected staff.33

Summary of entity responses

35. The proposed audit report was provided to Defence, the Attorney-General’s Department and the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. Entities’ summary responses are included below and Defence’s full response is included at Appendix 1.

Defence

36. Defence welcomes the ANAO’s report on the Central Administration of Security Vetting and accepts the report’s three recommendations, which will strengthen and enhance the business improvement initiatives that the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) is currently progressing.

37. Defence acknowledges the challenges faced when security vetting services were centralised in 2010, and that deficiencies and inaccuracies in resourcing, demand and performance estimations made at the time have impacted upon service delivery and expected efficiencies. As identified in the report, government personnel security policy has been substantially reviewed and reformed over the last two years. This has necessitated significant changes to the AGSVA’s policy, systems and processes, which has also affected vetting throughput.

38. Defence also acknowledges that in the face of these challenges the AGSVA, as highlighted by the ANAO, has: continued to comply with Government security policy requirements34; achieved ISO 9001 accreditation of its quality management system; improved the usability of its ICT system in response to internal and customer feedback; and initiated substantial improvements to process automation. The AGSVA is also developing and implementing structured professional judgement tools to enhance quality, risk identification, mitigation and management in complex and changing social and threat environments. These initiatives will improve the efficiency, effectiveness and agility of security vetting assessments and service delivery, and will ensure continued confidence in the AGSVA’s delivery of the outcomes expected by Government.

39. Defence notes that in addition to the three formal recommendations, the ANAO’s report makes a number of informal recommendations: consultation with stakeholders on redevelopment of Key Performance Indicators; increased information sharing with agencies where risks are identified through the vetting process; and strengthening its information management controls framework. Defence agrees with the ANAO and has independently commenced work in these areas.

Attorney-General’s Department

40. The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) has protective security policy responsibility for the Australian Government as detailed in the Protective Security Policy Framework. The commentary in the ANAO audit report on Central Administration of Security Vetting does not appropriately balance the roles of the Departments of Defence and Finance with that of the Attorney-General’s Department in the development of the new policy proposal.35 In addition, the report does not adequately acknowledge the complex and contested policy space in which the centralised vetting proposal was developed.

41. AGD supports the three recommendations that will strengthen centralised vetting arrangements delivered by the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA). However, the report contains a number of findings, which in AGD’s view should be coupled with recommendations to ensure the gaps and vulnerabilities identified in the current centralised vetting arrangements are appropriately addressed.

42. The outcomes of the ANAO audit will be used to inform AGD strategic review of the Australian Government’s personnel security arrangements.

Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

43. Significant strides have been made with the AGSVA in resolving some of the points of difference that have historically existed in the relationship. Chief amongst these was the agreement reached with the AGSVA in early 2015 for ASIO to commence its security assessment of individuals only once the AGSVA’s vetting recommendation had been finalised. It is anticipated that this will significantly reduce system inefficiencies by providing ASIO with access to all information collected during the vetting process thereby reducing exchanges with the AGSVA over requests for further information, significantly improving ASIO’s response timeframes, and limiting ASIO effort expended on cases that are later rejected by the AGSVA on eligibility or suitability grounds.

44. Substantial progress has also been made in recent months over the drafting of a formal ASIO/AGSVA Protocol intended to address issues raised in the ANAO report commentary regarding such matters as processing times for non-complex cases, mandatory data requirements, and ICT arrangements. It is expected this draft will be finalised by July this year and provide a robust and flexible framework for engagement.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 3.31 |

To provide additional assurance that AGSVA’s Industry Vetting Panel (IVP) contractors are operating in accordance with applicable security policies and procedures, the ANAO recommends that Defence implement a targeted audit program to assess IVP contractors’ operations. Defence response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.55 |

To strengthen quality control over vetting decisions and promote consistent decision-making, the ANAO recommends that Defence introduce a program of internal peer review supplemented by periodic independent external quality assurance of Delegate decisions. Defence response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 5.39 |

To improve efficiency and maintain the integrity of security vetting, the ANAO recommends that Defence develop a clear pathway to achieve agreed timeframes for processing and revalidating security clearances. Defence response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the role of the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency in the management of personnel security. It also introduces the audit objective, scope and methodology.

Background

1.1 Security vetting involves the assessment of an individual’s suitability to hold a security clearance at a particular level. Australian Government employees and contractors require a security clearance to access classified resources, which can relate to Australia’s national security, economic and other interests. The security vetting and clearance process is an important risk mitigation activity intended to protect the national interest, which can also affect an individual’s employment and the business operations of entities if not managed effectively or in a timely manner.

1.2 Australian Government entities managed their own security vetting for employees and contractors until the end of September 2010. AGSVA was then established within the Department of Defence (Defence) from 1 October 2010 to centrally administer personnel security clearances on behalf of Australian Government entities.36 Centralised vetting was expected to result in: a single security clearance for each employee or contractor, recognised across government entities; a more efficient and cost-effective security vetting service; and cost savings of $5.3 million per year.

1.3 Most government entities must use AGSVA’s security vetting service for personnel that require a clearance.37 AGSVA’s vetting process involves enquiry into, and corroboration of, a person’s background, character and personal values, before a decision is made by AGSVA on whether to grant or continue a clearance.

Australian Government Security Vetting Agency

1.4 The security vetting services provided by Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) to Australian Government entities38 include: assessing individuals’ applications for security clearances; managing reported changes in individuals’ circumstances; and periodically assessing individuals’ ongoing suitability to hold a security clearance. The AGSVA Service Level Charter (Charter) documents the services to be provided by AGSVA, fees payable for the services, agreed performance standards and vetting responsibilities of AGSVA and entities.

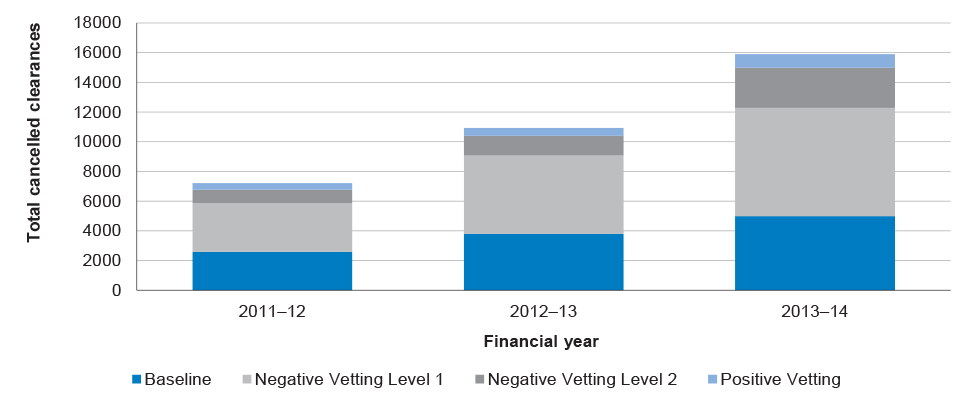

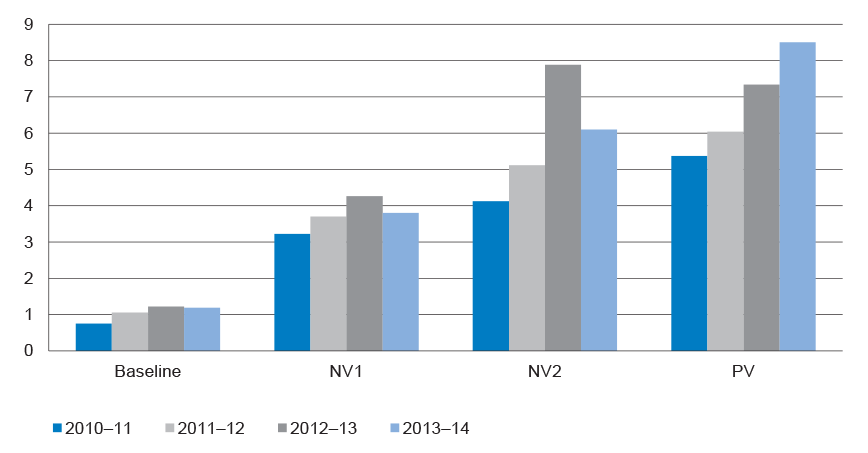

1.5 As at March 2015, AGSVA had management responsibilities for over 349 000 active Australian Government security clearances.39 Figure 1.1 shows the number of security clearance cases finalised by AGSVA since the agency’s first full year of operations. Finalised cases include those that were granted, continued, denied or revoked. It does not include clearances cancelled during the clearance process.40 The figure shows a slight reduction in finalised cases from approximately 39 000 in 2011–12 to 33 000 in 2013–14. The reduction in finalised cases broadly corresponds with the reduction in overall Australian Public Service (APS) staff numbers in 2012–13 and 2013–14.41

Figure 1.1: Number of security clearance cases finalised by AGSVA, by level, 2011–2014

Source: Analysis of AGSVA annual reports to Secretaries’ Committee on National Security (SCNS).

Organisational structure and personnel

1.6 AGSVA forms part of Defence’s Intelligence and Security Group, and is led on a day-to-day basis by the Assistant Secretary Vetting. The current organisational structure of AGSVA includes an executive group in Canberra, a National Coordination Centre in Brisbane, a Vetting Support Centre in Adelaide and regional offices in each state and territory. The National Coordination Centre conducts administrative activities, including coordinating vetting work and managing contractors. The Vetting Support Centre manages security clearance maintenance activities and the AGSVA Customer Service Centre. The regional offices are responsible for vetting assessments and determinations.

1.7 Before the launch of AGSVA, the then Defence Vetting Branch comprised 188 full-time equivalent APS staff. At the same time, the Australian Security Vetting Service (ASVS) within AGD, provided security vetting services for some government entities which did not have an in-house vetting function. In establishing AGSVA, the then Government moved ASVS functions from AGD to Defence as a Machinery of Government change, and increased Defence’s civilian average staffing level by 40, including the ASVS staff. This meant that AGSVA was initially funded to have 228 APS staff. As at March 2015, AGSVA employed 272 APS staff.

1.8 The former Defence Vetting Branch used a contracted workforce to perform vetting services and supplement APS staff. AGSVA also relies on a contracted workforce to perform certain vetting assessment work and provide support services. AGSVA has three main contracting arrangements in place: the Industry Vetting Panel (IVP); the CareersMultiList (CML) contract; and contracted psychological services:

- The IVP comprises 21 companies and approximately 210 Assessing Officers (AOs).42 Upon receipt of a request from AGSVA, the IVP AOs assess an individual’s suitability to access classified resources and make a recommendation to AGSVA as to whether a security clearance should be granted.

- The CML contract is used to provide AGSVA with short-term administrative support personnel. CML personnel perform vetting support services such as checking submitted clearance packs for completeness and printing hard copy clearance packs for IVP assessment. As at February 2015, 49 CML personnel worked at AGSVA’s Brisbane office and another 18 at the Adelaide office.

- AGSVA also utilises a panel of approximately 48 industry psychologists to supplement its internal psychological assessment capability as required.

ICT systems

1.9 AGSVA uses a number of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) systems to support security vetting, including the Personnel Security Assessment Management System (PSAMS), ePack and Defence’s records management system, Objective:

- PSAMS is intended to be the authoritative source of all personnel security clearance data managed by AGSVA. It is used to coordinate clearance requests, track their progress and record decisions made.

- After PSAMS is used to initiate a clearance process, the clearance subject accesses the ePack questionnaire, which takes them through a series of information requirements and enables the provision of most information through the Defence Online Services Domain.43

- After submission by the clearance subject, the ePack and supporting information is uploaded into PSAMS. Documentation relevant to the security clearance process is contained in each clearance subject’s Personal Security File (PSF) and stored in Defence’s records management system, Objective.

Personnel security policy and clearances

1.10 The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) establishes controls for the Australian Government to protect its people, information and assets.44 The PSPF includes: Personnel Security Core Policy, Personnel Security Protocol, Vetting Practices Guidelines, and Personnel Security Agency Responsibility Guidelines which provide detailed policy and guidance on personnel security and security vetting. A decision about granting a security clearance should be made in accordance with the standards identified in the PSPF.

1.11 The Personnel Security Core Policy aims to:

- reduce the risk of loss, damage or compromise of Australian Government resources by providing assurance about the suitability of personnel authorised to access those resources;

- create an environment where those accessing Australian Government resources are aware of the responsibilities that come with that access and abide with their obligations under the PSPF;

- minimise potential for misuse of Australian Government resources through inadvertent or deliberate unauthorised disclosure; and

- support a culture of protective security.45

1.12 The Personnel Security Core Policy establishes nine mandatory requirements for personnel security, which apply to Commonwealth entities, personnel and/or the entities that conduct security vetting (see Appendix 2). Under the Core Policy, vetting assessments and decisions are to take into account all available and reliable information, whether favourable or unfavourable, about the clearance subject. The Personnel Security Core Policy states that: ‘Any doubt about the suitability of a clearance subject is to be resolved in favour of the national interest.’46

1.13 Australian Government entities must ensure that access to, and dissemination of, classified resources is restricted to those personnel who need the resources to do their work—the ‘need-to-know’ principle.47 There are four levels of security clearance that allow personnel to access associated levels of classified resources. Table 1.1 outlines the clearance levels, corresponding access levels, and the reported number of active clearances for each level as at March 2015.

Table 1.1: Active security clearances, current levels, March 2015

|

Clearance level |

Security level of accessible resources |

Active clearances |

|

Baseline |

Protected |

58 361 |

|

NV1 |

Protected, Confidential, Secret |

59 696 |

|

NV2 |

Protected, Confidential, Secret, Top Secret |

21 878 |

|

PV |

All classification levels including certain types of caveated, compartmented and codeworded information. |

5 346 |

|

Total |

|

145 281 |

Source: AGD, Australian Government Personnel Security Protocol, Version 2.0, Canberra, September 2014, pp. 16–17, and ANAO analysis of PSAMS data.

1.14 The four current security clearance levels were introduced as part of the PSPF in 2010. Before that time, there were six national and non-national security clearance levels. Table 1.2 shows the number of clearances at previous levels which were still active as at March 2015, and their alignment with current clearance levels.

Table 1.2: Active security clearances, previous levels, March 2015

|

Previous clearance level |

Current equivalent clearance level |

Number of active clearances |

|

Restricted and Entrya |

No equivalent |

47 430 |

|

Protected |

Baseline |

36 322 |

|

Highly Protected |

No equivalent |

13 506 |

|

Confidential |

No equivalent |

43 951 |

|

Secret |

NV1 |

50 283 |

|

Top Secret Negative Vetting (TSNV) |

NV2 |

8 327 |

|

Top Secret Positive Vetting (TSPV) |

PV |

4 114 |

|

Total number of active clearances |

|

203 933 |

Source: ANAO analysis of PSAMS2 data.

Note a: Restricted and Entry level clearances were entity specific levels and not recognised as whole-of-government clearance levels.

1.15 Recent high profile international incidents have highlighted the importance of sound personnel security practices, and the potential consequences of inadequate vetting and employer monitoring and reporting.48 In a speech to the 2014 Security in Government Conference, the Attorney-General stated that:

The leaking of classified information both at home and overseas highlights the importance that our framework must remain up to date to guard against the threat posed by trusted insiders. …

To address the risks that could arise from a trusted insider, the importance of security vetting, contact reporting and ongoing monitoring of our employees’ suitability to access information should never be underestimated.49

1.16 In late 2014, AGD introduced a number of reforms to personnel security policy. The reforms are intended to clarify the responsibilities of government entities, direct resources to the areas of greatest risk and further strengthen the assessment of a person’s ongoing suitability to hold a security clearance.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.17 The audit objective was to examine whether the Department of Defence provides an efficient and effective security vetting service for Australian Government entities through the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA).

1.18 The high-level criteria used to assess AGSVA’s performance were:

- AGSVA’s establishment was well planned and supported by an implementation strategy that enabled the agency to undertake the responsibilities conferred upon it;

- AGSVA has adequate guidelines, procedures and systems in place to support the security clearance process;

- AGSVA’s security clearance policies and procedures comply with Australian Government policy, including the PSPF;

- AGSVA identifies areas for improvement in security clearance arrangements and implements strategies to enhance performance; and

- Defence monitors, evaluates and reports on the efficiency and effectiveness of AGSVA’s security vetting service.50

1.19 The ANAO consulted with relevant stakeholders including Australian Government entities and industry representatives. In September 2014, the ANAO issued a Questionnaire to a selected group of 30 Australian Government entities to obtain feedback on AGSVA’s performance and identify areas for improvement. Twenty-three entities responded to the Questionnaire, and their feedback has been included in relevant sections of the audit report.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of some $560 000.

Report structure

1.21 The remaining report structure is outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Report structure

|

Chapter number and title |

Contents |

|

Chapter 2: Policy Advice and Implementation |

Examines the development of policy advice to government on the establishment of centralised vetting arrangements; implementation planning and management for the establishment of AGSVA; and reviews and reforms of AGSVA’s operations following the agency’s launch. |

|

Chapter 3: The Security Vetting Process |

Examines AGSVA’s management of security vetting, including oversight of the Industry Vetting Panel and compliance with protective security policy. |

|

Chapter 4: Management of Information Systems |

Examines the development and management of AGSVA’s information systems and security clearance data. |

|

Chapter 5: Performance Monitoring and Reporting |

Examines AGSVA’s key performance indicators and performance reporting. It also examines the timeliness of AGSVA’s security vetting services and entity feedback on the agency’s performance. |

2. Policy Advice and Implementation

This chapter examines the development of policy advice to government on the establishment of centralised vetting arrangements; implementation planning and management for the establishment of AGSVA; and reviews and reforms of AGSVA’s operations following the agency’s launch.

Introduction

2.1 Before the establishment of AGSVA, Australian Government security vetting was decentralised, with over 100 government entities managing personnel security vetting based on Australian Government policy requirements. In December 2007, the then Government agreed that the Attorney-General would bring forward a cross-portfolio savings option to establish a single security vetting agency for all Australian Government security clearances. The option to establish a centralised vetting unit within AGD was explored until September 2009, at which time the Secretary of AGD agreed to discuss the possibility of Defence hosting the centralised vetting unit with the Secretary of Defence. This led to a proposal recommending the establishment of AGSVA within Defence, which was presented to the National Security Committee of the Cabinet (NSC) in November 2009. Following ministerial agreement to the proposal, Defence had ten months to prepare for the launch of AGSVA on 1 October 2010.

2.2 In this chapter, the ANAO examines:

- policy advice to government on the establishment of centralised security vetting arrangements;

- Defence’s implementation planning and management for the establishment of AGSVA; and

- reviews of AGSVA’s operations following the agency’s launch in October 2010, and related reforms of AGSVA’s structure, systems and processes.

Policy advice on centralised vetting

2.3 In reviewing the development of policy for the proposed centralised vetting unit, the ANAO focused on proposed implementation arrangements and risk management. Experience shows that a policy initiative is more likely to achieve its intended outcomes when the question of how the policy is to be implemented has been an integral part of policy design. It is also important to inform the Government of any significant risks to implementation and proposed responses, particularly when rapid policy development and implementation are required.51

Vetting Review Scoping Study

2.4 As mentioned in paragraph 2.1, in December 2007, the then Government agreed that the Attorney-General would bring forward a cross-portfolio savings option to establish a single security vetting agency in place of the decentralised model operating at that time. The measure was to be considered as part of the 2008–09 Commonwealth Budget process. Subsequently, in March 2008, the then Prime Minister agreed to defer consideration of the savings option, and that AGD should undertake a cross-entity survey to identify ways to achieve efficiencies in security vetting and assess the feasibility of a centralised vetting agency.

2.5 AGD conducted the survey of Australian Government entities, referred to as the Vetting Review Scoping Study (Scoping Study), between 25 June 2008 and 9 July 2008. The Scoping Study attempted to gauge the level and cost of security vetting activity across government, and the nature of the administrative arrangements used to perform the work. Of the 164 entities invited to participate in the survey, 111 (68 per cent) responded.52 Some of the main findings of the Scoping Study are summarised in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Findings of the Vetting Review Scoping Study

|

Subject matter |

Main findingsa |

|

Vetting activities |

The survey respondents reported finalisation of 42 646 initial security clearances in 2007–08. Defence reported finalisation of 24 131 initial security clearances in 2007–08 (some 57 per cent of total initial clearances). |

|

Vetting costs |

The respondents estimated their total expenditure on the administration of security clearances for 2007–08 at $43.9 million, excluding corporate overheads. Defence reported expenses of $26.2 million in 2007–08 (some 60 per cent of expenditure). |

|

Staff involved |

The respondents reported 304 full-time public servants directly involved in the administration of security clearances. Defence reported that 154 FTPS administered its security clearance process (some 50 per cent of the total FTPS). |

|

Staff qualifications |

Thirty-seven per cent of respondents reported that their assessing officers did not hold formal security vetting qualifications. |

|

Contractor work |

Forty-eight per cent of the respondents reported use of contracted service providers for vetting activities, with some respondents relying solely on contractors. Fifty-one per cent of the respondents who used contracted service providers reported that they had no process to verify the qualifications of service provider staff. |

|

Processing times |

The reported average security clearance processing times ranged from 49 working days for Protected clearances through to 124 working days for TSPV clearances. |

|

Transfer of clearances |

Five respondents reported that they had rejected the transfer of a security clearance from another entity. |

Source: AGD, Vetting Review Scoping Study, 2008.

Note a: The data in the table does not include survey responses provided by authorised vetting agencies other than Defence; specifically: the Australian Federal Police (AFP), the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and those Australian Intelligence Community agencies not in the Department of Defence.

2.6 The Scoping Study highlighted a number of inefficiencies in decentralised security vetting arrangements, including over 50 government entities managing separate contracts with vetting service providers, and entities not accepting the transfer of security clearances granted by other government entities. The Scoping Study also identified shortcomings in administrative arrangements, including that many entities employed staff with no formal vetting qualifications, did not verify the qualifications of contracted personnel performing vetting work and/or did not adequately oversee vetting work performed by contractors. These findings provided a basis for subsequent advice to government on the benefits of establishing a centralised vetting agency.

2.7 While the Scoping Study provided useful information on security vetting activities and costs for the respondents during 2007–08, it did not establish the total number and cost of vetting activities across government. In particular, 53 out of 164 entities (nearly one-third) invited to participate in the survey did not respond, and over half of the respondents did not answer all of the survey questions.53 Further, entities self-assessed their vetting activities, costs and arrangements, and the data they provided was not independently validated, even on a sample basis.

Proposal for a centralised vetting unit within the Attorney-General’s Department

2.8 Following completion of the Scoping Study, in early 2009, AGD commenced development of a proposal to centralise government security vetting and provide ‘whole-of-government’ security clearances. The proposal involved the establishment of a centralised vetting unit within AGD, with the majority of the work to be contracted out to a panel of service providers, managed by the centralised vetting unit.

2.9 Under the AGD proposal, certain law enforcement and intelligence entities were to be exempted from centralised vetting due to the sensitive environment in which they operated. Further, Defence was to be exempted due to concerns that the centralised vetting unit could not manage the high volume Defence vetting workload, and on the basis that Defence already had the infrastructure and systems in place to perform this work in the most efficient manner. The exclusion of Defence, and the high start-up costs faced by AGD in the establishment of a centralised vetting unit, initially reduced its ability to identify significant cost savings.

2.10 The proposal was considered by the Secretaries’ Committee on National Security (SCNS) in September 2009, which requested further work to address concerns raised by some entities regarding the proposed business model. The proposal to exempt Defence, which accounted for around half of vetting activities in 2007–08, brought into question the achievement of efficiencies under the proposed business model. In other words, to achieve the benefits associated with centralisation, AGD needed to develop a model which included Defence.

Proposal for a centralised vetting unit within Defence

2.11 Notwithstanding an initial reluctance to host a centralised vetting unit, following a request from the Secretary of AGD in September 2009, Defence agreed to do so by expanding its existing vetting operation to manage whole-of-government requirements.

2.12 In November 2009, Ministers agreed to centralise security vetting in Defence, with limited exemptions54, on the basis of a revised proposal developed by AGD in consultation with Defence and the then Department of Finance and Deregulation. The centralised vetting unit was to be the authority for granting and revalidating security clearances, which would have automatic application across the Australian Government, except for other authorised vetting agencies. Introduction of centralised vetting was expected to increase efficiency in the vetting process, improve consistency in vetting practice, reduce delays in the transfer of clearances and deliver cost savings of $5.3 million per year.

2.13 However, in a number of key areas, the revised proposal was not soundly based. In particular, there were shortcomings relating to vetting resource requirements and costs savings, and implementation readiness and risks. AGD informed the ANAO in May 2015 that the revised proposal was developed in the context of a complex and contested policy space.

Centralised vetting resources and cost savings

2.14 The identification of potential savings from centralised vetting depended on the methodology used to calculate cost estimates, and the assumptions made about vetting activity and future resource requirements. Cost estimates for the revised proposal were calculated as follows:

- Firstly, the overall annual cost of decentralised vetting activity was estimated at $43.9 million, based on the Scoping Study survey responses.

- Secondly, the estimated annual cost of centralised vetting activity within Defence was derived using a Defence cost modelling tool and the Department of Finance and Deregulation 2010–11 costing template for personnel finance.

- Two key assumptions were made: that the level of vetting activity undertaken by the proposed centralised vetting unit would be similar to that reported by entities for 2007–08; and that the unit would comprise 228 staff. The total cost of vetting activities by a Defence centralised vetting unit was estimated to be $38.6 million.

- The difference between $43.9 million and $38.6 million was used to estimate the annual cost saving arising from the move to centralised vetting—some $5.3 million.

2.15 The cost estimates relied on incomplete and unverified data from the Scoping Study. As discussed, nearly one-third of entities did not respond to the Scoping Study survey and many respondents did not answer all questions related to expenses. However, the revised proposal placed no caveats on the $5.3 million savings figure.

2.16 The proposed number of centralised vetting unit staff (228) represented a 25 per cent reduction on the reported number of vetting staff across government for 2007–08. Further, the revised proposal was based on conducting the majority of vetting activity in-house, whereas around half of the survey respondents had reported using contractors to process clearances.

2.17 The Scoping Study identified contractor costs under decentralised vetting arrangements of $15.9 million for 2007–08. In contrast, the revised proposal estimated centralised vetting unit contractor costs at $6.5 million, which was a reduction of $9.4 million (59 per cent). The proposal did not address how the proposed Defence centralised vetting unit would manage the volume of whole-of-government vetting activity without increased reliance on external vetting contractors.

2.18 The revised proposal did not consider potential risks relating to the overall reduction in resource levels; particularly how Defence would maintain vetting throughput and achieve anticipated savings. In the event, the number of staff employed by AGSVA has increased over time—as at March 2015, AGSVA employed 272 staff, compared to 228 in October 2010. In addition, AGSVA has continued to rely heavily on a range of contracted personnel to perform vetting and support activities. In 2013–14, the IVP conducted approximately 90 per cent of vetting assessments for NV1 and NV2 clearances and approximately 15 per cent of PV clearances, at a cost of approximately $12.8 million; and AGSVA’s total expenditure on vetting services contractors in 2013–14 was some $17 million.

Implementation readiness and risks

2.19 The revised proposal rated the overall implementation risk for the proposed centralised vetting arrangement as ‘low’, and it was presented as an efficient option using an ongoing vetting operation in Defence that already processed the majority of government security clearances. The proposal noted that Defence had a strong record managing a high volume vetting workload, and start-up costs would be minimised because Defence already had the necessary infrastructure, technology, personnel and expertise. The proposal did not mention that Defence had experienced significant backlogs in the completion of its own security vetting.

2.20 In addition, the revised proposal did not mention that Defence’s two primary security vetting processing systems—PSAMS and ePack—were undergoing critical upgrades to meet vetting requirements. Defence had identified the importance of these upgrades as early as 2007:

By not improving the technology used within the vetting processes, [the Defence Security Authority] will be unable to meet current and future demand for security clearances. This will impact on the Department in extended recruitment times, higher risk of a major security breach and continued bad publicity for the department in regards to its clearance process.55

2.21 The system upgrades were initially combined and known as the ‘PSAMS Refresh Project’. The August 2009 Project Plan identified a number of risks and issues which had the potential to affect Defence’s readiness for centralised vetting on the proposed establishment date. Ultimately, both of the system upgrades encountered major difficulties, which are discussed later in this chapter and in chapter 4.

2.22 At the time the revised proposal was put to government (November 2009), significant changes to protective security policy were planned. The PSPF was released in June 2010, replacing the Protective Security Manual (PSM). The changes brought about by the PSPF included the introduction of revised national security clearance levels (refer to Table 1.2), mandatory periodic review periods for all security clearance levels56, and mandatory competencies for security vetting practitioners.

2.23 The revised proposal suggested that the centralised vetting unit start date be delayed from July 2010 until October 2010, to give Defence sufficient time to respond to the protective security policy changes by amending its IT systems to support vetting under the revised security clearance levels. However, the revised proposal did not consider any other potential implications of prospective changes to personnel security policy for the centralised vetting unit’s operations. For example, it did not consider the potential need to:

- align existing security clearances with the new clearance levels;

- process security clearance revalidations for all clearance levels in specified timeframes; and

- train the vetting workforce to meet mandatory competencies.

Purchaser-provider arrangement

2.24 The main risk identified in the revised proposal was that the Defence centralised vetting unit may be inefficient and unresponsive. This risk was to be mitigated through a rigorous and transparent purchaser-provider arrangement and performance reporting.

2.25 Purchaser-provider arrangements have been adopted by many public sector organisations in recent decades. These arrangements separate the ‘purchaser’ from the ‘provider’ of public services in order to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery.57 In the Australian Government context, purchaser-provider arrangements have been used to draw on the experience of entities that have specialised delivery skills.

2.26 Under the proposed centralised vetting purchaser-provider model, Defence was to charge other government entities the cost of processing clearances.58 This arrangement was intended to mitigate the risks of over or under funding of the central vetting unit. The intent was also to send a clear message (price signal) to customers about the actual cost of resources involved in security vetting. Charges were to be updated annually and approved by the Secretary of Defence in consultation with the then Department of Finance and Deregulation.

2.27 AGSVA’s fees were incorporated in its Charter in August 2010. The fees remained unchanged until July 2014, when increases of 15 to 67 per cent for initial clearances and 15 to 30 per cent for revalidations were made (refer to Table 2.2). The significant fee increases indicate that charges were not well aligned with the cost of security vetting for some time.

Table 2.2: AGSVA fee increases

|

Clearance level |

Initial clearance |

Revalidation |

||

|

2010 ($) |

2014 ($) |

2010 ($) |

2014 ($) |

|

|

Baseline |

333.67 |

394.46 |

133.58 |

157.78 |

|

NV1 |

637.68 |

1067.22 |

255.06 |

426.89 |

|

NV2 |

1757.71 |

2023.12 |

703.25 |

809.25 |

|

PV |

6791.73 |

8967.31 |

5432.80 |

7173.58 |

Source: Department of Defence, AGSVA Service Level Charter, 5 August 2010; and Department of Defence, AGSVA Service Level Charter, 1 July 2014.

2.28 Until recently, Defence contractors could obtain a security clearance free of charge through Defence, whereas other government entities were charged for the contractors they sponsored. On 1 January 2015, AGSVA commenced charging Defence industry providers and contractors for security vetting services, indicating that: ‘All revenue raised—estimated at $7–10 million per annum—will be used to build vetting capacity and enhance service delivery.’59

2.29 Recent fee increases have been significant, and going forward, a more disciplined approach to the fee setting regime is required, including: close tracking of vetting expenses and revenue; informing stakeholders about factors that influence vetting costs; and ongoing review of charges. As a sole provider of vetting services to most government entities, there would also be benefit in AGSVA periodically reviewing its methodologies, and benchmarking its activities against comparable systems to the extent practicable, with a view to identifying ways to improve efficiency and minimise charges.

Implementation planning and management

2.30 The successful implementation of a new policy initiative requires sound implementation planning and management:

In situations where timeframe imperatives have curtailed the consideration of implementation issues during policy development, the risk to successful implementation ‘down the track’ increases markedly. One of the most pressing priorities for the senior responsible officer is to promptly reduce this risk by seeking expert implementation advice and experience as soon as possible in the delivery phase. …

Successful implementation relies on the identification and management of risk. A robust risk management framework will promote accurate, well-informed judgements and mitigation strategies. The analysis of risks should commence as the policy is being developed and should continue through the implementation process.60

2.31 Following the November 2009 decision to establish AGSVA with a commencement date of 1 October 2010, Defence developed governance arrangements and implementation plans for the project. AGSVA was established within Defence’s Intelligence and Security Group under the control of the Chief Security Officer. An Assistant Secretary Vetting was appointed and a Project Implementation Team established to facilitate the transition from the then Defence Vetting Branch to AGSVA. A Steering Committee was also established to oversee the transfer of the Australian Government Security Vetting Service (ASVS) from AGD to Defence under a Machinery of Government change.

2.32 The Project Implementation Team developed several planning documents between February and April 2010 including: the Introduction into Service Plan for the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency; the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency Project Plan; and the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency Change Management Strategy. These plans identified a substantial body of work to be completed before the commencement of AGSVA’s operations. Key tasks included:

- the development of standard operating procedures and directives for the new organisation;

- business and financial model development;

- development and finalisation of service level agreements with other Australian Government entities;

- staff recruitment, transfers and training;

- significant upgrades to ePack and PSAMS;

- the creation of new external provider contracts and development of contract management arrangements; and

- testing of the AGSVA business model.61

2.33 Defence’s Project Plan identified seven project risks, including that a Defence revalidation backlog would not be cleared, the new ePack system would not be operational62, and modification of PSAMS to support the processing of clearances at the revised levels would not be completed by AGSVA’s commencement date of 1 October 2010. However, in planning for AGSVA’s implementation, Defence did not identify any risks arising from: the development of new operating procedures for whole-of-government vetting; protective security policy changes, including mandatory clearance review timeframes, and staff competencies; or the scale and complexity of implementation work, including the transfer of clearance data from other government entities. Experience has demonstrated that these were significant risks associated with the transition to centralised vetting and more could have been done to analyse and treat implementation risks.

2.34 Adding to the challenge, Defence lacked expertise in the delivery of whole-of-government services. Internal concerns were subsequently expressed that Defence’s implementation arrangements were not suited to respond to the scale and complexity of the task. By way of example, a 2011 Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) inquiry into allegations of inappropriate vetting practices within Defence stated:

I am advised that the oversight and implementation of [the ePack upgrade] was managed by the same team that had responsibility for the significant task of planning for and implementing the transition of the Vetting Branch to the AGSVA. This arrangement does not seem to have been fully effective.63

2.35 AGSVA commenced operations on 1 October 2010 without a comprehensive, centrally managed set of procedural documentation or robust, fully functioning ICT systems. It also inherited the Defence Vetting Branch management structure which was not designed for whole-of-government work, and lacked adequate governance, oversight and quality management processes. Weaknesses in the overall model and implementation planning were identified in subsequent reviews.

Post implementation reviews and reforms

2.36 A number of reviews have been conducted since AGSVA was established, including:

- Inquiry into Allegations of Inappropriate Vetting Practices in the Defence Security Authority and Related Matters, by the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS), December 2011;

- Review of the Processes and Management Arrangements Supporting Australian Government Security Vetting (also known as the ‘Colley Review’), January 2012;

- Organisational Analysis of the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency, undertaken by Mercer Pty Ltd for Defence’s Chief Security Officer, September 2012;

- four Defence internal audits of AGSVA, including three annual reviews of AGSVA’s compliance with government vetting policies in response to a recommendation of the IGIS inquiry;

- an assessment of AGSVA resourcing by Remote Pty Ltd in 2013; and

- an enterprise risk deep dive assessment of AGSVA, presented to the Defence Committee in February 2014.

2.37 The focus, key conclusions and recommendations of these reviews are discussed in the following sections.

Inquiry into Allegations of Inappropriate Vetting Practices

2.38 On 16 May 2011, ABC television’s Lateline program aired allegations made by three former contractors who had worked at the Defence Security Authority’s (DSA) National Coordination Centre in Brisbane. They made a series of allegations about inappropriate vetting practices, including ‘falsifying’ the information relating to clearance subjects to ‘get the numbers up’.64 The former contractors alleged that they were encouraged to make unapproved changes when entering information from submitted security packs into PSAMS to increase the volume of security clearances processed.

2.39 On 29 May 2011, the then Prime Minister requested that the IGIS conduct an inquiry into the Lateline allegations. The resulting December 2011 IGIS report confirmed the allegations and identified a number of factors that led to these practices, including:

- delayed and inadequate systems upgrades;

- inadequate formal documentation and manuals;

- inadequate training for contractors and APS staff;

- the use of delegates who had not completed formal qualifications;

- poor systems and process change management;

- inadequate quality assurance;

- inadequate management oversight and contractual arrangements; and

- sustained pressure for vetting output following increases in demand.

2.40 The IGIS report made 13 recommendations, which were all agreed to by the then Government. The recommendations addressed wide ranging aspects of AGSVA’s administration, including the need to:

- appropriately document business processes, policies and procedures;

- professionalise the vetting workforce;

- implement a Quality Management System;

- provide appropriate management oversight of contracted personnel;

- review the adequacy of staffing numbers; and

- assign high priority to the implementation of PSAMS2.

2.41 A September 2014 Defence internal audit concluded that 11 of the 13 IGIS recommendations had been implemented, with two recommendations relating to staff training yet to be fully implemented.

Defence Security Vetting Review (Colley review)

2.42 The Colley review focused on the development of AGSVA’s management arrangements and work practices, and recommended 16 actions. The review report concluded in January 2012 that:

Progress in the review and the implementation of [the review’s] recommendations has been slower than expected, primarily because the work required to help bring the current AGSVA work instructions up to a fit for purpose standard has been more extensive than envisaged, the extensive remediation task faced by AGSVA, and a limited pool of subject matter experts.

… a comprehensive, fit for purpose set of documentation for current business processes is unlikely before the end of 2012.65

Organisational analysis

2.43 An organisational analysis of AGSVA was undertaken by external consultants during 2012. The aim of this work was to develop the most appropriate future structure and staffing model for AGSVA to support the anticipated demand for vetting services across Australia.66

2.44 The outcomes of the organisational analysis were reported in September 2012, and included the following recommendation:

… a reconsideration of AGSVA permanent staffing requirements given the analysis. It is understood that there are political considerations in requesting additional [staff], however an appropriately sized workforce is required for a sustainable structure, maintaining internal vetting capability, reducing risk and reducing overall staffing costs. Mercer also recommends minimising the amount of vetting assessment work that is outsourced to IVP as this has the potential to erode internal capability, poses greater risks and quality management issues, and is overall a more costly approach.67

Defence internal audits of AGSVA

2.45 Recommendation No.3 of the December 2011 IGIS report, referred to above, was that:

The Defence Chief Audit Executive should review and report annually on the AGSVA’s compliance with all applicable Government security vetting policies, with the first review to be completed by 30 June 2012. The results of the reviews should be reported in Defence’s annual report. The need for annual reviews should be reconsidered after three years.68

2.46 Defence’s Chief Audit Executive completed three internal audits of AGSVA, in June 2012, August 2013 and September 2014.69 The audits reviewed AGSVA’s compliance with government security vetting policy, implementation of the IGIS report recommendations and the progress of the associated AGSVA reform agenda. Defence completed a fourth internal audit in July 2014, which examined financial management in AGSVA.