Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Government Funding of Public Hospital Services — Risk Management, Data Monitoring and Reporting Arrangements

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of risk management, data monitoring and public reporting arrangements associated with the Australian Government's funding of public hospital services under the 2011 National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In 2016–17, there were 695 public hospitals in Australia. Each state1 operates its own public hospital system. Under the 2011 National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA), the Australian Government contributes to the cost of operating these public hospitals. In 2017–18, the Australian Government provided $19.94 billion under the NHRA, with the states providing $26.57 billion. The Australian Government contribution is provided primarily on the basis of ‘activity based funding’ (ABF) — a structure where hospitals are funded for the number and mix of patients they treat.2

2. The NHRA specified the establishment of two ‘national bodies’ plus a statutory position to administer the new public hospital funding arrangements; the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (Pricing Authority), the National Health Funding Body (Funding Body), and the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool3 (the Administrator).

3. Amongst other functions4, the Pricing Authority determines the National Efficient Price (NEP), a key input into the calculation of the Australian Government’s National Health Reform (NHR) ABF contribution. The Funding Body assists the Administrator in undertaking their functions, including advising the Treasurer on both the total Australian Government NHR payment contribution for the upcoming year and whether any adjustments should be made to payments after the end of the year due to changes in number of hospital services provided or other reasons. The Administrator also publishes reports on Australian and state government NHR funding levels and numbers of public hospital services.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The Pricing Authority and Funding Body have important roles under NHRA arrangements through setting the efficient price of public hospital services and then calculating and administering Australian Government public hospital funding. The audit was selected as the integrity of key processes in both entities are highly reliant on the accuracy and completeness of state public hospital cost and service activity data.

5. The audit examines whether the NHR funding arrangements, including public reporting, provides transparency on the allocation of Australian Government funding. In a different context, the ANAO’s audit Monitoring the Impact of Australian Government School Funding5 highlighted a lack of sufficient assurance that relevant Australian Government funding had been distributed to schools on the basis of need as required by the relevant legislative framework. The current audit also assesses progress towards relevant policy objectives under the NHRA. The importance of monitoring the impact of Australian Government funding, and to provide greater accountability, was also a theme in the ANAO’s school funding audit.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of risk management, data monitoring and public reporting arrangements associated with the Australian Government’s funding of public hospital services under the 2011 National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA).

7. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted two high-level criteria:

- the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have appropriate processes for managing risks to the accuracy of the public hospital service and cost data and to monitor significant changes to the data; and

- relevant Australian Government entities appropriately utilise available data to provide transparent public reporting on both the Government’s funding of public hospital services and progress towards the hospital-related policy objectives of the NHRA.

8. The audit scope does not include an assessment of the technical process through which the Pricing Authority determines the National Efficient Price or National Efficient Cost or through which the Funding Body calculates and subsequently reconciles Australian Government funding amounts.

Conclusion

9. The Pricing Authority and the Funding Body have effectively implemented data-related risk management and monitoring arrangements that are consistent with their public hospital funding roles under the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA). Public reporting by a range of Australian Government entities provides reasonable transparency regarding funding levels, numbers of services and progress towards NHRA objectives of improved hospital efficiency, patient access, and safety and quality of clinical care in hospitals. The failure to implement the agreed reporting at the Local Hospital Network level has weakened the NHRA’s ability to drive systematic improvement in the performance of public hospitals across Australia.

10. The Pricing Authority and Funding Body have put in place controls to mitigate risks posed by inaccurate or incomplete data. The nature of these controls and other risk-related processes are consistent with their respective roles under the NHRA.

11. Both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body monitor public hospital service and cost data to identify and analyse any significant changes. The mandate of the Funding Body to undertake more detailed analysis on the causes of growth in Australian Government activity based funding (ABF) could benefit from clarification.

12. Agreement has also not been reached between stakeholders on an approach to manage the risks of the Australian Government making duplicate payments for the same public hospital service. Recent work indicates that these payments may be in the range of $172 million to $332 million per year.

13. There is public reporting by Australian Government entities on public hospital funding provided under NHRA. Transparency regarding the fulfilment of state governments funding commitments could be improved. Estimates of the number of public hospital services delivered by individual Local Hospital Networks are reported, noting that the actual number of services are only reported at the aggregated national level. The absence of the originally intended Local Hospital Network level performance reporting has weakened the reporting framework’s ability to achieve associated performance improvement objectives under the NHRA.

14. Public reporting shows mixed progress against NHRA hospital performance objectives. There have been some positive trends regarding hospital efficiency. On patient access, emergency department performance has declined slightly, but for elective surgery there have been improvements in some indicators. There has been no notable progress on improving the safety and quality of clinical care, although only a limited range of performance indicators are currently reported on.

Supporting findings

15. Under the NHRA, the Australian and state governments are responsible for the integrity of the data held within their systems, including data provided to the Pricing Authority and Funding Body.

16. The 2017 Addendum to the NHRA introduced additional data quality and integrity measures. Notably, state governments must include a statement of assurance regarding the accuracy and completeness of service activity data used to support the reconciliation of Australian Government ABF payments. The value of the statement of assurance process has been reduced by inconsistencies in the level of information provided by states against its required elements.

17. Both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have embedded systematic risk management strategies and practices into the key ABF-related business processes that use state data. These include undertaking a range of data validation and quality review processes in relation to both cost and service activity data.

18. Through mutual representation on each entity’s advisory committees, the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have awareness of, and communicate about, their respective data-related risk management approaches.

19. Both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have undertaken or commenced reviews of their broader risk management frameworks in 2018. Both entities regularly review their risk registers and other relevant process documents such as data plans.

20. The Pricing Authority and Funding Body monitor relevant data to identify significant changes and trends. States consider that the conduct of this work by the Funding Body is inconsistent with its key functions under the NHRA and the National Health Reform Act 2011.

21. In part due to lack of agreement between stakeholders about the use of relevant data, the Funding Body has not been able to accurately monitor the extent to which the Australian Government is making duplicate payments for public hospital services through the NHRA and Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Preliminary work by the Funding Body does however indicate that potential duplicate payments may be in the range of $172 million to $332 million per year. The lack of agreement has also meant that the Department of Health has not had access to the matched public hospitals MBS data that would facilitate more comprehensive compliance and recovery action on potential duplicate MBS payments.

22. The Performance and Accountability Framework established under the NHRA was only partially implemented. Notably, the intended Local Hospital Network level reporting never occurred, weakening the framework’s ability to drive improved performance and achieve the associated objectives under the NHRA. Some public reporting against a limited set of performance indicators has occurred. Work has commenced to consolidate the existing multiple health reporting frameworks and develop a definitive set of performance indicators for public reporting.

23. Public reporting, mainly by the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool, provides transparent information on Australian Government public hospital funding services down to the Local Hospital Network level. However, public reporting does not provide clarity on whether state governments are fulfilling their commitment in the NHRA to maintain their own 2017–18 funding of public hospital services at 2015–16 levels.

24. Public reporting by the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool provides transparent information on the forecasted volume of public hospital funding services expected to be delivered at the Local Hospital Network level. The Administrator also reports the actual number of services delivered, but only at the aggregated national level rather than at the local level.

25. Existing public reporting provides a reasonable level of information about the mixed progress towards the hospital-related policy objectives under the NHRA of increased efficiency, patient access and safety and quality of clinical care. Reporting on efficiency suggests a modest improvement based on the stability of the national efficient price and improvements in the time a patient spends in hospital compared to expectations. Reporting on patient access suggests a slight decrease in performance against emergency department indicators, contrasted by a slight improvement in elective surgery related indicators. There has been no notable progress on improving the safety and quality of clinical care, although only a limited range of performance indicators are currently reported on.

26. The current development of a definitive set of performance indicators under the 2017 Australian Health Performance Framework should assist with the transparency and reliability of future reporting.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.61

The Department of Health:

- work with relevant state government entities to reach agreement on the appropriate data monitoring analysis roles for the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority and National Health Funding Body; and

- incorporate the agreed roles into the revised National Health Reform Agreement currently under negotiation.

Department of Health: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.72

The Department of Health:

- identify and prevent potential duplicate payments, including Medicare Benefits Schedule payments, by the Australian Government for public hospital services; and

- identify and recover past duplicate payments to the maximum extent permitted by law.

Department of Health: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.15

The Department of Health seek the agreement of states to implement reporting arrangements that provide transparency on whether state governments are maintaining public hospital services funding levels in accordance with National Health Reform Agreement obligations.

Department of Health: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

27. Summary responses were received from the Department of Health and the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority and are provided below. The National Health Funding Body did not provide a summary response. The full responses of all three entities are at Appendix 1.

Department of Health

The Department is pleased that the ANAO found public reporting by a range of Australian Government entities in the Health Portfolio provides reasonable transparency regarding funding levels, number of services and progress towards the National Health Reform Agreement objectives of improved public hospital efficiency, patient access, and safety and quality of clinical care in hospitals.

Also positive, the report finds the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority and the National Health Funding Body have effectively implemented data-related risk management and monitoring arrangements are consistent with their public hospital funding roles under the National Health Reform Agreement.

The report has identified the absence of performance reporting at the Local Hospital Level (LHN) areas has limited the reporting framework’s ability to achieve the performance improvement objectives under the National Health Reform Agreement. While the proposal has merit, the department notes the LHNs vary considerably in characteristics, size and service mix, and their composition is determined by the states and territories. Any future performance reporting at the LHN level will be dependent on state and territories providing this data.

The report proposes more comprehensive compliance and recovery action on potential duplicate payments under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and National Health Reform Agreement. MBS compliance activities are a part of the department’s normal business, however, the use of matched National Health Reform funding and MBS claims is required to comprehensively identify duplicate payments. A pilot data matching activity has been progressed in a careful and methodical manner given inter-agency and inter-jurisdictional complexity. The department agrees that the future effectiveness of related compliance action is largely dependent on agreement by stakeholders about the use of relevant data and will continue to work toward this outcome in National Health Reform Agreement negotiations.

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority

The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA) has developed and implemented robust risk management processes since the agency was established in 2011.

Agency staff regularly reviews the strategic risk register, and risk treatments are in place for all significant risks that have been identified. Those risks and their treatments are considered by IHPA’s executive, its audit and risk committee and the Pricing Authority.

The quality of activity and cost data supplied by jurisdictions to IHPA for the purposes of determining the NEP and NEC has consistently been identified as a key risk. As a result IHPA has instituted a number of important strategies to validate and quality assure data supplied by states and territories, including the development of the Secure Data Management System (SDMS), which allows data submitters to validate data prior to submission to IHPA enabling them take steps to address any issues detected prior to submission.

Once data is submitted, IHPA undertakes considerable analysis of the data so as to understand the impact that decisions IHPA has taken may have had on the delivery of public hospital services.

Where potential issues are identified, IHPA works closely with jurisdictions through the Jurisdictional Advisory Committee (JAC) to identify and understand the underlying drivers.

IHPA works closely with the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool and the National Health Funding Body (NHFB), and has commenced a process to address the formal identification of shared risks between the agencies, as required under the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. As part of this a renewed Memorandum of Understanding between the NHFB and IHPA will be executed in early 2019.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Public hospitals in Australia

1.1 In 2016–17, there were 695 public hospitals in Australia providing 62,000 beds.6 Table 1.1 shows the geographic distribution of these facilities.

Table 1.1: Public hospitals in Australia, 2016–17

|

|

NSW |

Vic. |

Qld |

WA |

SA |

Tas. |

ACT |

NT |

Total |

|

Major cities |

66 |

53 |

20 |

19 |

15 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

176 |

|

Regional |

137 |

96 |

70 |

37 |

44 |

19 |

0 |

1 |

404 |

|

Remote |

19 |

2 |

33 |

35 |

18 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

115 |

|

Total |

222 |

151 |

123 |

91 |

77 |

23 |

3 |

5 |

695 |

Source: Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW).

1.2 Of the 695 public hospitals, 171 had 10 beds or fewer, and 302 had between 10 and 50 beds. The number of beds per head of population varies by location. In major cities, there are 2.43 beds per 1000 people. In regional areas, the figure is 2.79, and in remote areas, it is 3.58. On a national basis, the number of beds per head of population has remained virtually unchanged in the period 2012–13 and 2016–17.

1.3 The Australian Government does not operate any public hospitals.7 Each state8 operates its own public hospital system. Management of public hospitals within this system is through mainly regionally-based Local Hospital Networks (LHNs), of which there are 147 throughout Australia. Each LHN has an annual service agreement with the relevant state health department setting out the nature and number of public hospital services the relevant LHN will provide.

Public hospital funding under the National Health Reform Agreement

The National Health Reform Agreement

1.4 Prior to 2012, the Australian Government contributed to the cost of operating public hospitals primarily through multi-year ‘block’ funding arrangements.9 Payments were indexed by a range of factors, but generally included allowances for healthcare cost inflation, population and demographic changes, and higher demand for services resulting from better technology.10 During this period the Australian Government also funded public hospitals under a range of national partnership arrangements and programs.11

1.5 The National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA) was agreed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in August 2011. It introduced a fundamental change whereby Australian Government payments to public hospitals would be primarily made on the basis of ‘activity based funding’ (ABF) — a structure where hospitals are funded for the number and mix of patients they treat.12 Apart from the quality and safety matters covered in Table 1.4, Australian Government funding levels under the NHRA are not dependent on the states achieving any performance benchmarks or implementing specific reform measures.

1.6 The NHRA specified the establishment of two ‘national bodies’ plus a statutory position to administer the new public hospital funding arrangements; the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (Pricing Authority), the National Health Funding Body (Funding Body), and the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool (the Administrator). The respective roles and responsibilities of these bodies, as well as those of other relevant Australian Government entities, are outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Entity roles and responsibilities

|

Entity |

Roles and responsibilities |

|

Pricing Authority |

Determining the National Efficient Price (NEP), a key input into the calculation of the Australian Government’s National Health Reform (NHR) ABF amount. The NEP provides a price signal or benchmark for the efficient cost of providing hospital services. Determining the National Efficient Cost (NEC), which establishes the Australian Government funding contribution to (mostly rural) block funded hospitals. It represents the average cost of block funded hospitals across Australia. Determining the public hospital functions that are to be funded by the Australian Government. Developing national classifications for public hospital activity. |

|

Administrator |

Calculating the Australian Government NHR funding amounts and advising the Australian Government Treasurer on these. Overseeing payment of Australian Government NHR funding flowing through the National Health Funding Pool. Reconciling the estimated and actual volume of public hospital service delivery and advising the Australian Government Treasurer regarding any proposed additional reconciliation payments. Public reporting of funding and volume of services provided. |

|

Funding Body |

Assisting the Administrator in carrying out his or her functions. |

|

Treasurer |

Approving the NHR Australian Government funding amounts. |

|

Department of Health |

Providing health and hospitals policy advice to the Australian Government, including negotiating a new public hospital funding agreement to take effect from 2020. Administering related funding programs including the Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. |

Source: National Health Reform Agreement 2011 and entity documentation.

1.7 The Pricing Authority was established under the National Health Reform Act 2011 and the Administrator and Funding Body under an amendment to the Act in 2012. Separating the pricing function (Pricing Authority) from the funds administration function (Administrator and Funding Body) into distinct independent entities was intended to address concerns raised by some states that the Administrator would be handling state funds and therefore would need to be an officer appointed by the states.13

Calculating Australian Government funding

1.8 Figure 1.1 shows NHR funding provided by the Australian Government and the states over the life of the NHRA. Australian Government funding in 2017–18 was $19.94 billion with total state government funding14 $26.57 billion.

Figure 1.1: National Health Reform Funding 2012–13 to 2017–18

Note: Funding refers to amounts actually paid in the relevant year. State funding has been adjusted for cross border payments

Source: ANAO analysis of public reporting by Administrator.

1.9 The Australian Government’s annual NHR funding contribution is the total of three funding components: activity based funding, block funding and public health funding.

Activity based funding

1.10 Australian Government ABF payments made in 2017–18 were $17.22 billion, and constituted 86.4 per cent of its NHR funding for public hospitals.

1.11 Under the funding formula set out in the NHRA, the Australian Government’s annual ABF contribution for each state is the sum of:

- the previous year’s Australian Government ABF amount15;

- a price adjustment — 45 per cent of any change in the NEP from the previous year; and

- a service volume adjustment — 45 per cent of any change in the estimated number of services to be delivered as compared to the previous year. 16

1.12 The key steps in calculating the NEP (and thus the ABF price adjustment) are outlined in Box 1.17

|

Box 1: Key steps in the Pricing Authority’s annual calculation of the National Efficient Price |

|

Step 1: Use state public hospital cost and service activity data to calculate the weighted average cost of delivering a public hospital service in Australia. Step 2: Deduct specified ‘out of scope’ funding and services to calculate a revised average cost. Step 3: Apply an indexation factor to allow for estimated increases (or decreases) in the cost of delivering services in the relevant NEP year. For example, the 2018–19 NEP is based on 2015–16 cost data and indexation allows these costs to be projected forward to 2018–19. |

1.13 Both the number of public hospital services, and the nature of those services, to be delivered change from year to year. For NHRA purposes, services are expressed as National Weighted Activity Units (NWAUs) (see Box 2).

|

Box 2: Measuring and pricing services: the National Weighted Activity Unit |

|

The NWAU provides a way to compare and value each public hospital service by weighting it for clinical complexity, with one NWAU equalling the ‘average’ hospital activity. Simple (and thus less expensive) hospital services are worth a fraction of an NWAU, while more intensive and expensive services have higher weightings. For example in 2018–19:

Given that the NEP for 2018–19 is $5012 per NWAU, the respective ‘efficient cost’ of delivering these services are:

Price weights and adjustments (expressed as NWAUs) are also applied to the price to reflect the legitimate and unavoidable variations in the cost of delivering health care services, such as the location of the patient’s residence and patient complexity. |

1.14 Under transitional arrangement accompanying the introduction of the NHRA, the pre-NHRA block funding amounts each state was receiving effectively formed the ‘base amount’ from which Australian Government ABF funding from 2014–15 onwards has been calculated. The net result is that current Australian Government ABF funding levels are still influenced by the varying proportions of each state’s public hospital costs that were funded by the Australian Government under pre-NHRA block funding arrangements. These arrangements were the result of calculations based on historical costs, intergovernmental negotiation and prior government decisions. These calculations incorporated funding growth based on population estimates rather than number and mix of patients treated, whereas ABF contributions are based on activity. As a consequence, each jurisdiction receives a different Australian Government ABF contribution per NWAU as shown in Table 1.3. Tasmania receives the highest funding at $2236 and the Northern Territory the lowest at $1497. On a national basis, Australian Government funding is $1940 per NWAU.

Table 1.3: Australian Government 2016–17 activity based funding

|

Jurisdiction |

Australian Government activity based funding per NWAU ($) |

Proportion of the National Efficient Price funded by Australian Government (%) |

|

New South Wales |

1849 |

37.9 |

|

Victoria |

1942 |

39.8 |

|

Queensland |

2058 |

42.1 |

|

Western Australia |

2071 |

42.4 |

|

South Australia |

1807 |

37.0 |

|

Tasmania |

2236 |

45.8 |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

2142 |

43.9 |

|

Northern Territory |

1497 |

30.7 |

|

National |

1940 |

39.7 |

Note: As at early December 2018, 2016–17 figures were the most recent reconciled figures. The 2016–17 National Efficient Price is $4883 per NWAU.

Source: ANAO analysis of Administrator and Funding Body documents.

1.15 The impact of the ABF formula (under which the Australian Government is funding 45 per cent of efficient growth) means the differences will reduce over time. Chapter 3 provides more information on Australian Government contributions and funding levels over time for each state.

1.16 Some people are admitted into public hospitals as private patients. Australian Government ABF is payable for such patients, but with a variable discount applied to account for the revenue received by the treating hospital from the health insurer as well as any Australian Government payments to treating doctors through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).18

Block funding

1.17 Under the NHRA some public hospital services and functions are considered to be more appropriately funded through block grants rather than ABF.19 The Pricing Authority has developed block funding criteria in consultation with the states, and these criteria determine which services and functions are eligible for block funding. Australian Government block funding totalled $2.33 billion in 2017–18.

1.18 The major categories of block funding are:

- approximately 400 small rural hospitals receive funding under the national efficient cost (NEC) process (total payments of $903 million for 2017–18);20

- funding for teaching, training and research (total payments $536 million for 2017–18);

- other non-admitted services (total payments of $890 million for 2017–18).21

1.19 The Pricing Authority receives hospital level cost data from the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW)22 for the NEC model to determine block funding for small rural hospitals. The Pricing Authority does not receive cost data for the remaining categories in paragraph 1.18, instead relying on advice from the states on their expected expenditure. The Pricing Authority commissioned a review in 2018 to provide better information as to whether these block funding amounts accurately reflect actual costs.23

Public health funding

1.20 The Australian Government provided $387 million in 2017–18 for public health activities. This funding is calculated by the Australian Government Treasury and includes amounts for general public and youth health services and essential vaccines. Under the NHRA, states have complete discretion about how they use this funding in relation to their own health-related activities.

Public hospital funding flows

1.21 Under NHRA arrangements, a National Health Funding Pool (the Pool) has been created to consolidate all Australian Government ABF and block and state ABF. The Pool is comprised of separate Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) bank accounts for each state. In addition, each state has a discrete State Managed Fund for the purpose of receiving block funding. Each State Managed Fund is administered by the individual jurisdictions and lies outside the RBA system.

1.22 The Australian Government Treasury makes monthly ABF, block and public health funding payments into the Pool, with the block funding amount flowing through the Pool to each of the State Managed Funds. Each state determines when and how much funding they deposit into the Pool and the State Managed Funds. With the exception of some payments that go direct to state government health departments, payments from the Pool and the State Management Funds are then transferred to the LHNs who are responsible for delivering public hospital services. A simplified representation of the relevant funding and payment flows is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Simplified 2017–18 public hospital funding and payment flows

Note: Differences in the total funding and total payments are due to timing issues of funds moving into and out of the Funding Pool and State Managed Funds. Payments of activity based funding out of the National Health Funding Pool are made through a Department of Human Services payments system. The NSW Ministry of Health transfers the $10.09 billion shown above to NSW LHNs. See paragraph 3.9 for more detail.

Source: Administrator’s 2017–18 Annual Report and ANAO analysis.

1.23 The monthly payments made into the Pool are prospective payments based on LHN estimates of hospital service activity levels.24 At the end of each six-month (July to December) and annual (July to June) period, the states provide actual hospital activity data to the Funding Body (via the Pricing Authority) to enable it to reconcile these to the previous estimates. The Australian Government’s payments are then adjusted annually in arrears to account for this reconciliation.

1.24 The Pool’s accounts are audited each year by the respective Auditor-General for each state, and each audited financial statement is published in the Administrator’s annual report.

NHRA hospital related policy objectives

1.25 In addition to increasing the proportion of public hospital costs funded by the Australian Government and promoting the transparency of how public hospitals are funded, key NHRA objectives relating to the public hospital system are listed below.

- Improving public hospital efficiency. Efficiency is usually defined in terms of minimising the cost of a specific hospital service.

- Improving patient access to hospital services. Accessibility is usually defined as being able to obtain health care at the right place and right time.

- Improving standards of clinical care. This is usually defined in terms of patient safety (avoidance of adverse events) but more recently quality of care concepts, such as clinical outcomes and a patient’s experience in hospital, are being incorporated into development of new performance indicators.

The 2017 NHRA Addendum

1.26 The NHRA commenced in 2012–13 with a transition period for the first two years, whereby Australian Government funding to the states was capped at the funding levels that would have applied under previous National Healthcare Specific Purpose Payment block funding agreement. From 2014–15 to 2016–17 the Australian Government funded 45 per cent of increased costs flowing from the ‘efficient growth’25 of public hospital services.

1.27 Australian Government funding was to increase from 45 per cent of efficient growth to 50 per cent from 2017–18 onwards. However, with Australian Government NHR funding growth accelerating from 5.6 per cent in 2013–14 to over 11 per cent in both 2014–15 and 2015–16,26 the Australian Government negotiated an addendum to the NHRA that retained its contribution at 45 per cent. In addition, the addendum introduced a 6.5 per cent national cap on growth in the Australian Government contribution to apply from 2017–18.

1.28 Table 1.4 summarises key provisions in the addendum.

Table 1.4: Key 2017 NHRA Addendum provisions

|

Amendment |

Additional details |

|

Australian Government funding contribution |

Australian Government funding remains at 45 per cent of the cost efficient growth, subject to the funding cap. |

|

Funding Cap |

Limits total Australian Government funding increases to 6.5 per cent annually from 2017–18. Funding increases to individual states is also limited to 6.5 per cent except where slower growth in some jurisdictions allows left over funds to be proportionally redistributed to higher growth jurisdictions as part of the annual reconciliation process. |

|

Incorporation of quality and safety into hospital pricing and funding |

Any episode giving rise to a sentinel event27 will not be funded by the Australian Government. A pricing and funding model for hospital-acquired complications will be introduced from 1 July 2018, and an appropriate pricing and funding model for avoidable hospital readmissions will be determined after 1 July 2018. |

|

Reforms to decrease avoidable demand for public hospital services |

Agreement to develop a range of coordinated care reforms for patients with chronic and complex conditions to deliver better care and reduce avoidable demand for health services. |

|

Data quality and integrity |

A commitment to jurisdictions working together and with the national bodies to share and work towards best practice approaches. A data conditional payment to encourage the prompt provision of the required data for timely reconciliation. Each jurisdiction must annually issue a Statement of Assurance on the completeness and accuracy of approved data submissions to the Australian Government. Public reporting on compliance with data requirements by the Administrator. |

|

Certainty of reconciliation |

The final Australian Government funding entitlement of a jurisdiction will not be adjusted unless any issues affecting the accuracy of the entitlement is advised to the Administrator within 12 months of the end of the financial year. The Administrator can also identify issues including inaccuracies or errors within 12 months of the end of the relevant financial year. |

Source: NHRA Addendum.

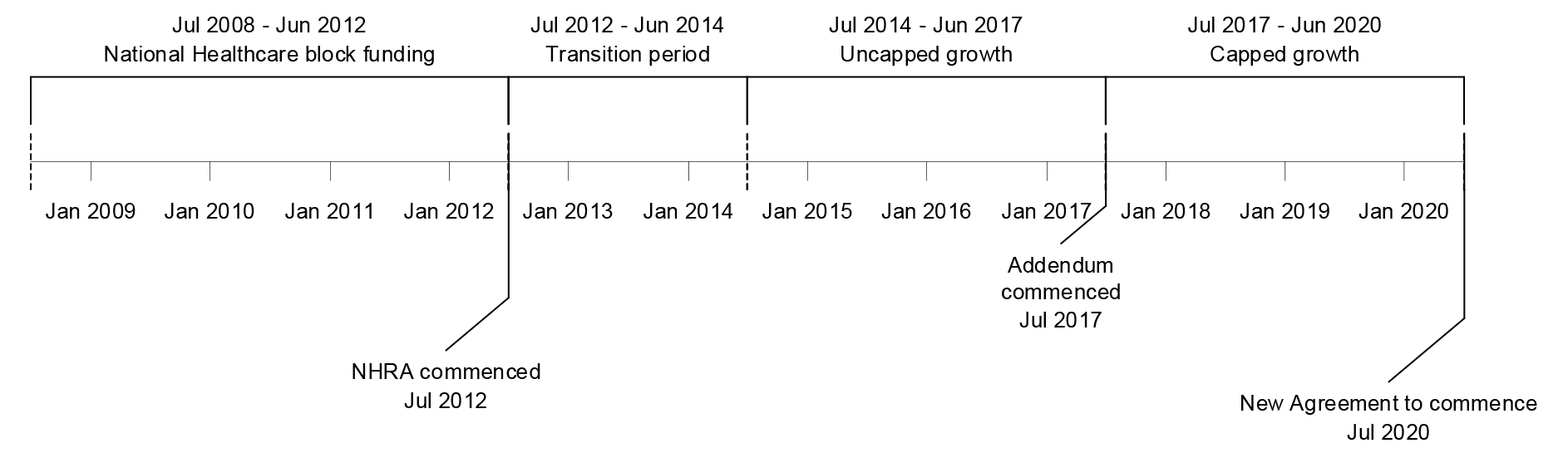

1.29 At the time of the audit, a new five-year national funding agreement is being negotiated to take effect from July 2020. Figure 1.3 provides an overview of the timeframes of health care agreements from 1 July 2008.

Figure 1.3: Overview of health care agreement timeframes

Source: NHRA, NHRA Addendum and COAG Heads of Agreement.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.30 The Pricing Authority and Funding Body have important roles under NHRA arrangements through setting the efficient price of public hospital services and then calculating and administering Australian Government public hospital funding. The audit was selected as the integrity of key processes in both entities are highly reliant on the accuracy and completeness of state public hospital cost and service activity data.

1.31 The audit examines whether the NHR funding arrangements, including public reporting, provides transparency on the allocation of Australian Government funding. In a different context, the ANAO’s audit report Monitoring the Impact of Australian Government School Funding28 highlighted a lack of sufficient assurance that relevant Australian Government funding had been distributed to schools on the basis of need as required by the relevant legislative framework. The current audit also assesses progress towards relevant policy objectives under the NHRA. The importance of monitoring the impact of Australian Government funding, and to provide greater accountability, was also a theme in the ANAO’s school funding audit.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.32 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of risk management, data monitoring and public reporting arrangements associated with the Australian Government’s funding of public hospital services under the 2011 National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA).

1.33 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have appropriate processes for managing risks to the accuracy of the public hospital service and cost data and to monitor significant changes to the data; and

- relevant Australian Government entities appropriately utilise available data to provide transparent public reporting on both the Government’s funding of public hospital services and progress towards the hospital-related policy objectives of the NHRA.

1.34 The audit scope does not include an assessment of the technical process through which the Pricing Authority determines the NEP and NEC or through which the Funding Body calculates and subsequently reconciles Australian Government funding amounts.

Audit method

1.35 The audit method comprised:

- analysis of relevant aspects of the Pricing Authority and Funding Body’s operations, including data-related risk management and monitoring process associated with core business processes;

- reviewing the activities of hospital financing and medical benefits areas of the Department of Health, including advice provided to the Australian Government;

- obtaining evidence from the offices of state Auditors-General about their recent work on public hospital funding and performance29;

- obtaining evidence from the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, and the Productivity Commission regarding their hospital-related performance framework and reporting roles; and

- analysis of relevant data held and/or reported by the Funding Body, Administrator, Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, and the Productivity Commission.

1.36 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $572,785. The team members for this audit were Angus Martyn, Renee Hall, Michael Jones, Ailsa McPherson, Danielle Page, Paul Bryant and Julian Mallett.

2. Risk management and monitoring

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (Pricing Authority) and National Health Funding Body (Funding Body) have appropriate processes for managing risks to the accuracy of public hospital service activity and cost data and to monitor significant changes to the data.

Conclusion

The Pricing Authority and Funding Body have put in place controls to mitigate risks posed by inaccurate or incomplete data. The nature of these controls and other risk-related processes are consistent with their respective roles under the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA).

Both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body monitor public hospital service and cost data to identify and analyse any significant changes. The mandate of the Funding Body to undertake more detailed analysis on the causes of growth in Australian Government activity based funding (ABF) could benefit from clarification.

Agreement has also not been reached between stakeholders on an approach to manage the risks of the Australian Government making duplicate payments for the same public hospital service. Recent work indicates that these payments may be in the range of $172 million to $332 million per year.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at clarifying data monitoring and analysis roles and also preventing and/or recovering duplicate payments for public hospital services.

Does the National Health Reform Agreement include provisions about data quality and integrity?

Under the NHRA, the Australian and state governments are responsible for the integrity of the data held within their systems, including data provided to the Pricing Authority and Funding Body.

The 2017 Addendum to the NHRA introduced additional data quality and integrity measures. Notably, state governments must include a statement of assurance regarding the accuracy and completeness of service activity data used to support the reconciliation of Australian Government ABF payments. The value of the statement of assurance process has been reduced by inconsistencies in the level of information provided by states against its required elements.

2.1 Australian and state government entities are jointly responsible for the provision of a range of data to the Pricing Authority and Funding Body to enable them to carry out their functions under the NHRA, as outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Key data provided to the Pricing Authority and the Funding Body

|

Type of data |

Data provider |

Data recipient |

Frequency of submission |

Purpose |

Accompanying data integrity statements |

|

Activity data |

|||||

|

Estimated number of services (expressed as National Weighted Activity Units or NWAUsa) to be delivered in coming year |

State government health departments |

Funding Body |

Annualb |

Input into calculating Australian Government Activity Based Funding (ABF) amounts |

Nil |

|

Actual number and detail of services delivered |

State government health departments |

Pricing Authority, who provides to the Funding Body |

Six monthlyc |

Input into calculating the Nationall Efficient Price (NEP) and National Efficient Cost (NEC); Input into reconciliation of Australian Government ABF payments against actual services delivered |

Statement of Assurance |

|

Cost data |

|||||

|

National Hospital Cost Data Collection |

State government health departments |

Pricing Authority |

Annual |

Input into calculating the NEP |

Data quality statement |

|

National Public Hospital Establishments Database |

Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) |

Pricing Authority |

Annual |

Input into calculating the NEC |

Data quality statement |

|

Funding and other data |

|||||

|

De-identified pharmaceutical program payments |

Department of Health |

Pricing Authority |

Annual |

Input into calculating the NEP |

Nil |

|

De-identified Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme(PBS) claims data |

Department of Health |

Funding Body |

Annual |

Match with activity data to identify potential duplicate payments |

Statement of assurance |

Note a: National Weights Activity Units (NWAUs) provide a way to compare and value each public hospital service by weighting it for clinical complexity, with one NWAU equalling the ‘average’ hospital activity. See Box 2 in Chapter 1.

Note b: Non-binding estimates can also be provided by states at any time.

Note c: Provided every six months up to 2017–18, however in accordance with the Pricing Authority’s three year data plan for 2018–19 to 2020–21, data will be submitted each quarter from 1 July 2018.

Source: ANAO summary of the three year data plans for the Pricing Authority and the Administrator.

2.2 Under the NHRA, governments are responsible for the integrity of data they provide to the national bodies, including the Pricing Authority and Funding Body.30 As part of this, all jurisdictions must have appropriate independent oversight mechanisms for data integrity.31

2.3 During the negotiation of the NHRA Addendum in 2016 and 2017, the Funding Body developed a range of proposed measures intended to enhance integrity and assurance arrangements relating to the ABF system. These included:

- the development of a National Data Integrity Framework to improve the quality and timeliness of state activity data; promote a consistent national approach; and establish a national standard against which state Auditors-General could undertake quality reviews; and

- that the Funding Body — on behalf of the Administrator of the National Health Funding Pool (the Administrator) — undertake a review of activity data to assist states to comply with their obligations under the NHRA.

2.4 Neither of these proposals were supported by the states as they were considered too prescriptive.32 However, agreement was reached that state governments must include a statement of assurance on the completeness and accuracy of the activity data submissions provided for the reconciliation process.

2.5 The required content of the statements of assurance, and associated administrative processes, were agreed between respective governments in December 2017. Under these processes, the statements of assurance are not made public but the Administrator does publicly report on whether a statement of assurance has been submitted by each jurisdiction.33 In terms of content, jurisdictions are required to provide commentary against three elements, with a fourth being optional, as illustrated in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Statements of assurance: summary of states’ commentary provided against agreed elements

|

|

Description provided of steps taken by state regarding completeness and accuracy of hospital service activity dataa |

Description provided of efforts by state to classify activity in accordance with current year’s standards, data plans and determinations |

Commentary on variations in activity levels and movements between ABF and block funding |

Any other commentary (optional) |

|

New South Wales |

Yes |

Yes |

Reports that activity growth was higher than expected due to increase in acute and emergency admissions. |

Provides links to new policies and describes strategies for improving health IT infrastructure. |

|

Victoria |

Yes |

Yes |

Reports lower than anticipated NWAU due to implementing a new coding standard. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Queensland |

Yes |

No |

Reports that there was no movement between ABF and block funding. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Western Australia |

Yes |

Yes |

Reports detailed information of changes in activity and movements between ABF and block funding at the hospital level. |

Provides information on changes in hospitals and their impact on the data collections. |

|

South Australia |

Yes |

No |

Nil information provided. |

Provides information on a discrepancy that is currently being investigated for one type of data. |

|

Tasmania |

Yes |

Yes |

Reports change in activity levels, and no movement between ABF and block funding. |

Provides information on technical issues with one data type. |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

No |

Yes |

Reports changes in two types of activity data. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Northern Territory |

Yes |

No |

Reports changes in activity data. |

Provides explanations for activity data streams affected by critical errors or high numbers of warning errors. |

Note a: This element is relevant to providing information on the oversight mechanisms for data integrity that each government has in place as per NHRA requirements.

Source: ANAO analysis of statements of assurance provided with the six month activity data submission in September 2018.

2.6 As shown in Table 2.2, there was significant variation in the detail of information against the second and third elements, and in some cases no commentary was provided at all, with no explanation provided for its absence. While it is to be expected that individual commentaries will reflect differences in the maturity of data collection and governance processes between jurisdictions, the value of the statement of assurance process largely depends on a reasonable level of information being provided against all three compulsory elements. This is particularly so in light of the lack of progress in providing the Administrator with state data integrity frameworks.34 Neither the Pricing Authority nor Funding Body took any follow-up action regarding the lack of commentary or information against some of the mandatory elements. However, the Funding Body did advise that it had used the statements of assurance to identify issues requiring investigation as part of the 2016–17 reconciliation process.

2.7 The Pricing Authority considered the statements could be enhanced if the results of any steps taken to promote completeness and accuracy of data (such as coding35 audits) were required to be included in the statement. This is a matter that could be usefully considered in the review of the content of the statements that is due to occur under the auspices of the cross-jurisdictional Health Services Principals Committee.

2.8 Cost data is accompanied by data quality statements, an arrangement that predates the introduction of statements of assurance. While under NHRA arrangements, jurisdictions are not required to provide these statements, all did so for the most recent (2016–17) round of cost data provided to the Pricing Authority. Jurisdictions provide information against four elements, as illustrated in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Data quality statement information: summary of states’ commentary provided against agreed elements

|

|

Indication of state’s conformance with Australian hospital patient costing standards (AHPCS)a |

Information on state’s data quality assurance arrangements |

Information on limitations in the provided data |

Notice of state’s plans to address data limitations (where relevant) |

|

New South Wales |

Data aligns with AHPCS version 3.1. |

Describes data reconciliation processes, audit program and third party peer reviews. |

Describes technical issues relating to five data types. |

Describes costing methodology changes to further refine and improve data collection. |

|

Victoria |

Data conforms with AHPCS version 3.1 — qualified for three data types. |

Describes compliance with Victorian cost data collection business rules and specifications, and data reconciliation reports. |

Describes technical or collection issues relating to four data types. |

Notifies it is transitioning to apply AHPCS standards for one data type. |

|

Queensland |

Data aligns with AHPCS version 3.1 — qualified for two data types. |

Nil information provided. |

Describes technical or collection issues relating to two data types. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Western Australia |

Data conforms with AHPCS version 3.1 — qualified for one data type. |

Describes data reviews by area health services and data reconciliation processes with the state health department; and data validation and matching processes with activity data. |

Describes: technical issues relating to one data type; that aggregate costs relating to one data type have been excluded; and notes the closure of hospitals and the impact on the casemix and service provision. |

Notifies that there is improved patient level costing process to allow for separate reporting of admitted emergency costs at all sites, and that it continues to work on costing the small amount of outpatient activity that remains at an aggregate level. |

|

South Australia |

Data conforms with AHPCS version 3.1. |

Describes the costing system and processing of data, and reviews by state health department in conjunction with Local Hospital Networks (LHNs). |

Describes technical and collection issues relating to four data types. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Tasmania |

Data conforms with AHPCS version 3.1. |

Limited information provided. |

Nil information provided. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

Data conforms with AHPCS version 3.1. |

Describes a recent system wide data review which included the cost data provided for 2016–17. |

Describes technical or collection issues with four data types. |

Nil information provided. |

|

Northern Territory |

Data conforms with AHPCS version 3.1 — qualified for three data types. |

Limited information provided. |

Describes technical and collection issues relating to three data types. |

Nil information provided. |

Note a: The Australian hospital patient costing standards (AHPCS) are intended to provide best practice principles to costing hospital products, with consistent application of the standards generating high quality, reliable and comparable data.

Source: ANAO analysis of data quality statements provided with 2016–17 cost data (used to calculate the 2019–20 NEP).

Have the Pricing Authority and Funding Body embedded systematic risk management strategies and practices into those key business processes that use state data?

Both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have embedded systematic risk management strategies and practices into the key ABF-related business processes that use state data. These include undertaking a range of data validation and quality review processes in relation to both cost and service activity data.

2.9 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy (CRMP) supports the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and aims to strengthen the risk management practices of Australian Government entities. Entities subject to the CRMP ‘must ensure that systematic management of risk is embedded in key business processes’.

Risk management documentation

2.10 The ANAO reviewed the Pricing Authority and Funding Body’s key risk management policy and operational documents against the CRMP and relevant PGPA Act principles. The results of the review are outlined in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Pricing Authority and Funding Body risk management policy alignment

|

|

Pricing Authority |

Funding Body |

|

Entity type (as defined under the PGPA Act) |

Corporate Commonwealth entity |

Non-corporate Commonwealth entity |

|

CRMP requirements are mandatory |

Noa |

Yes |

|

Entity risk policy and framework aligned with CRMP |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Entity has risk register in place |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Entity risk register identifies relevant operational policies and procedures |

Yes |

Yes |

Note a: It is not mandatory for corporate Commonwealth entities (CCEs) to comply with the required elements of the CRMP however it states that CCE’s should review and align their risk management frameworks with the CRMP as a matter of good practice.

Source: ANAO analysis of entity risk management documentation.

2.11 The risk management policies and operational documents were largely aligned with the CRMP. The following minor improvements could be made:

- Pricing Authority36 — clear linking of its risk management policy to strategic objectives; and identifying the specific shared risks it manages through its communication and consultation practices. The management of shared risks between the Pricing Authority and the Funding Body is further discussed at paragraphs 2.33–41.

- Funding Body — clarifying its approach for measuring risk management performance.

2.12 In relation to the data required by the Pricing Authority and Funding Body to undertake their primary functions, a key risk identified by both entities is that data is of poor quality, not reliable or cannot be used. To assist in managing this broad risk, each entity publishes a rolling three year data plan. The data plans, which are developed with input from all jurisdictions and are updated annually, set out the approved data classifications37 and specifications38 for the required data, submission schedules and compliance reporting requirements.

2.13 The respective data plans of the Pricing Authority and Funding Body are appropriately aligned through setting common requirements such as data specifications.39 They are consistent with the data rationalisation objective in the NHRA, particularly the ‘single provision, multiple use’ concept.

Pricing Authority — key data review strategies and practices

ABF data quality

2.14 Consistent with its Data Quality Assurance Framework40, the Pricing Authority applies a range of quality-related processes to the activity and cost data it receives from states. These processes are intended to deliver improved data over time.

2.15 Since March 2017, all cost and activity data is submitted to the Pricing Authority through a secure data management system (SDMS) portal.41 Developed and owned by the Pricing Authority, the SDMS allows each state to run a validation check against the required data specifications contained in the Pricing Authority’s data plan before it submits the data. Validation reports that show the type and number of any errors in the data are also produced by the SDMS for the Pricing Authority once the data is submitted.42 In October 2018, the Pricing Authority completed a post-implementation review of the SDMS. The review indicated that data preparation and validation processes introduced under the SDMS have led to a reduction in the number of errors contained in relevant submissions and thus contributed to better data quality.

2.16 Following validation, activity and cost data is linked to create a merged data set. Quality assurance reports are produced both at the individual hospital and state level. The quality assurance reports include information on anomalies43, outliers44 and comparison of data with previous year’s results.45 The merged data and quality assurance results are then classified into three categories — ‘no material issues’, ‘some issues’ and ‘many issues — review required’. The results are provided to the Pricing Authority’s costing and pricing teams for review and comment, and any significant issues are referred back to the states, requesting comment or corrective action.

2.17 The ANAO reviewed the eight state level quality assurance reports for the 2016–17 cost and activity data that are being used to determine the NEP for 2019–20. As shown in Figure 2.1, the reports noted ‘some issues’ were found in most submissions in the five activity data streams, with three jurisdictions requiring review due to ‘many issues’ with acute or subacute activity data.

Figure 2.1: Number of jurisdictions overall data quality assurance result for 2016–17

Note: The Pricing Authority reporting indicates that ‘many issues’ represents the volume of issues represented in a data stream. For example, in one state’s result ‘many issues’ in the non-admitted activity data stream was due to the identification of 13,637 outliers.

Source: ANAO analysis of jurisdiction-level quality assurance reports.

2.18 Issues may be resolved through the relevant jurisdiction providing confirmation that the submitted data is correct, or in some cases formal resubmission of amended data. The resolution of issues is monitored by the Pricing Authority through its executive committee.46 Major data issues that continue over multiple submissions from the same state without improvement or resolution are publicly reported on the Pricing Authority’s website.47

2.19 Since 2015 there has been only one instance where public reporting of non-compliance directly relating to data quality has been required. That was caused by technical issues that prevented the relevant state from being able to provide non-admitted patient level activity data within agreed deadlines. The state subsequently provided the required data.

Financial reviews of ABF cost data

2.20 As an additional data validation measure, the Pricing Authority commissions an annual financial review to assess whether the cost data submitted by a sample of hospitals and LHNs reconciles with broader financial data in the relevant hospital and Local Hospital Network (LHN) systems. Participation by the states in the review process is voluntary, however all states engage in the process. The review of 2015–16 cost data was published in January 2018. The review did not find any significant deficiencies in the cost data48 and concluded that recent measures introduced in a number of jurisdictions had contributed to a more robust costing process. It also noted that some additional quality-related measures would be incorporated into the 2016–17 cost data collection process.49

2.21 Selection of the specific hospitals and LHNs to participate in the review is undertaken by the respective state health departments from a shortlist of ABF-funded hospitals and LHNs provided to them by the Pricing Authority. The mix of hospitals and LHNs on the shortlist are designed to achieve a variety of hospital sizes, complexity of services provided, and geographic locations.50 The size of the sample selected of the 2015–2016 cost data represents approximately four per cent of relevant hospitals and less than one per cent of LHNs. The sample size and selection process is not underpinned by a specific methodology to provide confidence that the review findings apply to ABF cost data in general or that the review is targeting higher risk hospitals or LHNs. The Pricing Authority advised the ANAO that the review sample size reflects a need to ‘balance the cost and effort of increased scope, with the improved benefits that may result from widening the scope’.51

Block funding

2.22 The major data input for the calculation of the NEC, which relates to Australian Government block funding of small rural hospitals under the NHRA, is the public hospital expenditure reported in the National Public Hospital Establishments Database (NPHED). The NPHED is a national dataset which comprises a core set of data elements agreed for mandatory collection and reporting at a national level. The NPHED is maintained by the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare and provided annually to the Pricing Authority. A data quality statement on the NPHED is published online.

2.23 The NEC Determination includes other categories of block funding, for services such as teaching, training and research and non-admitted mental health services (see paragraph 1.18). The funding amounts for these services are determined by the Pricing Authority on advice from the states. Where a state or territory advises an amount that would result in funding growth rate for these services greater than the NEC growth rate in that year (which was 2.9 per cent in 2018–19), the Pricing Authority requires additional evidence from the state before agreeing to this amount such as publicly available state budget papers. Where a state is unable to provide such supporting evidence, the Pricing Authority sets the relevant funding at the previous year’s amount, indexed by the NEC growth rate.52

2.24 As mentioned in Chapter 1, the Pricing Authority has undertaken a review on block funding to gain better information on whether the data underpinning jurisdictional advice, including the processes in place in each state to determine their block funding amounts, and the link between the amounts included in the NEC Determination and the funding provided by states and territories. The review found that the requirements to justify block funded amounts requested by the states have become more stringent over time and that the majority of states could break down block funding amounts with actual costs or expenditure on the services. The review also made three recommendations for improving the process of states nominating block funding amounts for the NEC Determination. The report was provided to Australian and state government health ministers for comment in early December 2018.

Funding Body — key data review strategies and practices

Calculation of Australian Government ABF contribution

2.25 Each state government provides the Funding Body with estimates of the number of public hospital services (expressed as NWAUs) that they anticipate each of their LHNs will provide for the upcoming financial year. This is a key data input into the Funding Body’s calculation of the level of Australian Government ABF. Estimates are provided at agreed milestone dates53 and are then updated when required.54

2.26 Once the NWAU estimates from each LHN are received, the Funding Body compares these with the NWAU figures contained in the service level agreements (SLAs) that each LHN has established with their relevant state health department.55 The ANAO conducted targeted testing of a sample of 15 LHN NWAU estimates against the relevant SLAs from a total population of 147 received by the Funding Body. All NWAU estimates tested matched the NWAU figures contained in the corresponding SLA.

2.27 The Funding Body also undertakes a review of the submitted NWAU estimates to identify any significant changes in the various activity categories (such as acute care or non-admitted services) from the previous year. Where the Funding Body identified such significant changes in 2018–19 estimates, there was evidence that it contacted the relevant jurisdiction to confirm whether there was a reasonable explanation for the change.

2.28 Figure 2.2 shows that, since the start of the NHRA, the number of NWAUs delivered each year on a national basis has consistently exceeded the estimates provided by the states. This has contributed to significant additional Australian Government ABF payments being made through the reconciliation process, particularly for 2015–16 ($512 million above original forecasts) and 2016–17 ($661 million above original forecasts). However, NWAU estimates for 2017–18 were much more accurate.

Figure 2.2: National estimated and actual National Weighted Activity Units

Source: ANAO analysis of Funding Body data.

ABF reconciliation process

2.29 State government health departments provide actual activity data to the Funding Body via the Pricing Authority twice annually — 31 March for the preceding July to December half year period, and 30 September for the full year. The Funding Body uses this to calculate whether any reconciliation adjustments should be made to Australian Government ABF payments.

2.30 Actual activity data is submitted through the Pricing Authority’s SDMS, and goes through the validation process referred to in paragraph 2.15 before being forwarded to the Funding Body. The Funding Body reviews the data to determine whether data characteristics (such as age profiles, indigenous status, location of services, types of services) indicate that the data is reasonable for use in the funding reconciliation and again contact relevant jurisdictions as considered necessary to gain an understanding of any major changes in underlying data. Funding Body records show that for the 2016–17 reconciliation, some outstanding data issues were discussed through formal meetings with state health departments and other stakeholders (including the Pricing Authority) and/or discussed at the Administrator’s jurisdictional advisory committee (JAC).56

2.31 Following the completion of the reconciliation process, including technical input from the Pricing Authority, the Funding Body prepares advice for the Administrator on any proposed retrospective adjustments to Australian Government ABF. The Administrator then provides detailed advice to the Treasurer (the decision-maker) on any recommended adjustment, including how this was calculated. Based solely on actual NWAUs delivered in 2016–17, the indicative additional Australian Government ABF payment was $791 million above what had been estimated for the relevant period by the states. However, the Funding Body applied a range of adjustments57 to reduce this to $307 million.58 The Administrator’s advice to the Treasurer noted that the states were critical of the methodology used in some of these adjustments59 but considered the adjustments were consistent with the ‘back-casting’60 provisions in the NHRA and that they were supported by the Minister for Health.

2.32 The Treasurer’s determination for 2016–17, incorporating the adjustment recommended by the Administrator, was made via legislative instrument registered on 2 October 2018. Following a regular meeting of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Health Ministers on 12 October 2018, state governments announced that they did not accept the adjustment determined by the Treasurer. The issue of public hospital funding and future reconciliation processes was discussed at the December 2018 COAG meeting but no change was made to the Treasurer’s determination regarding 2016–17 Australian Government funding.

Are effective processes in place between the Pricing Authority and Funding Body to communicate and manage shared risks regarding data received from the states?

Through mutual representation on each entity’s advisory committees, the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have awareness of, and communicate about, their respective data-related risk management approaches.

2.33 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy (CRMP) defines shared risks as:

those risks extending beyond a single entity which require shared oversight and management. Accountability and responsibility for the management of shared risks must include any risks that extend across entities and may involve other sectors, community, industry or other jurisdictions.61

2.34 While the Pricing Authority and Funding Body are independent statutory entities, their respective roles in administering NHRA public hospital funding arrangements means that their operations impact on each other. Notably, changes to pricing methodology and hospital services classifications by the Pricing Authority can have significant impacts on the Funding Body’s calculation of Australian Government ABF payments. These impacts have contributed to delays in determining the final Australian Government reconciliation payments for 2015–16 (determined in April 2018) and 2016–17 (determined in October 2018).

2.35 The degree of explicit articulation of shared risk issues and their management varies between the two entities. A key risk identified on the registers of both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body is that data is of poor quality, not reliable or cannot be used. As previously mentioned, the entities have prepared and aligned three year data plans to assist in managing this broad risk.

2.36 The Funding Body recognises the Pricing Authority’s role with regard to data provision in its risk management documentation, in particular in its: external systemic risk framework62; enterprise risk register; and draft funding pool risk register.63 In some instances, specific Pricing Authority processes are recognised as a control to manage Funding Body risks such as the inaccurate calculation of Australian Government funding.

2.37 While the Pricing Authority does not do the same, its current risk management policy provides that communication and consultation processes are used to manage shared and cross-jurisdictional risks. Shared risks are not explicitly identified.

2.38 The ANAO’s review of Pricing Authority advisory committee and working group records indicate that there has been communication about, and consultation on, an extensive range of data-related matters, including:

- understanding the impacts on jurisdictions of collecting the required data;

- timelines to incorporate standardised data collection methodologies;

- processes that ensure data accuracy;

- preliminary results from hospitals; and

- data quality.

2.39 Transparency is provided through the Pricing Authority’s advisory processes. For example, the Pricing Authority’s review of activity data is tabled at its technical advisory committee (TAC)64 and jurisdictional advisory committee (JAC)65 meetings. The Funding Body and Department of Health also attend the Pricing Authority JAC meetings.

2.40 The Administrator’s policies articulate the reconciliation and calculation processes, including the required data specifications provided to external stakeholders. The jurisdictions are able to comment on these documents prior to their publication at the Administrator’s JAC. During the reconciliation process, the Funding Body works with the Pricing Authority to discuss issues relating to the activity data and the calculation process and confirm NWAU calculations have been applied correctly.

2.41 A cooperation and information exchange memorandum of understanding (MOU) was in place between the two entities up until 2015. As at November 2018, the Pricing Authority and Funding Body had commenced discussions about developing a new MOU.66

Are the effectiveness of data-related risk management strategies and practices periodically reviewed?

Both the Pricing Authority and Funding Body have undertaken or commenced reviews of their broader risk management frameworks in 2018. Both entities regularly review their risk registers and other relevant process documents such as data plans.

Pricing Authority

2.42 The Pricing Authority started a review of a broad range of its governance and security policies during the conduct of the audit in August 2018. The review included its risk management policy and strategic risk register.67 As at November 2018, the Pricing Authority’s risk appetite statement had been updated and communicated to all staff, however remaining risk management aspects of the review have yet to be completed.

2.43 Prior to the review, the risk management policy was last updated in August 2016. As at October 2018, the risk register reflects recent developments such as the introduction of the SDMS in 2017, organisational changes68 and policy/process changes.69

2.44 Key policies identified as treatments in the Pricing Authority’s strategic risk register such as its three year data plan and data compliance policy have been updated in the last two years, however the data quality assurance framework, which is relied on as a key risk treatment, has not been reviewed since May 2012. While the data quality assurance framework document includes procedures that are currently undertaken by Pricing Authority staff, the policy terminology is outdated. A review of the data quality assurance framework would be timely.

2.45 To address risks with data management processes, including the effectiveness of the full lifecycle of processes and controls from data submission to management, use and disposal, the Pricing Authority has established a rolling annual internal audit ‘to review the design and operating effectiveness of the controls in place at the … [Pricing Authority] … in relation to Data Governance Processes.’ There have been six recommendations arising from the first two data management internal audits (July 2015 and February 2017) and all recommendations have been reported as implemented to the audit risk and compliance committee within six months. A third audit in September 2017 resulted in no recommendations.

Funding Body

2.46 The most recent review of the Funding Body’s overarching risk framework and risk policy, which also looked at implementation issues, was completed in March 2018. Two key findings in the review were that: