Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Government Crisis Management Framework

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF) is the basis for the Australian Government’s response to crises including pandemics, natural disasters, terrorism, and cyber incidents.

- To provide assurance to Parliament over processes to identify and disseminate lessons learnt, and on the readiness of government systems and processes to respond to future crises, as part of phase 3 of the ANAO COVID-19 multi-year audit strategy.

Key facts

- Between 2020 and 2023, the AGCMF has been used to respond to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters such as floods and cyclones, cyber security incidents, and Australian Government humanitarian assistance to overseas disasters.

- The Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet (PM&C) conducted a review of the AGCMF in 2023.

What did we find?

- PM&C has developed a largely appropriate framework for responding to crises.

- A structured assessment of the readiness of systems and processes was not undertaken prior to the 2023 AGCMF Review which commenced in March 2023.

- The revised AGCMF released in September 2024 incorporates an increased emphasis on continuous improvement and improved oversight.

What did we recommend?

- There were five recommendations aimed at processes to support annual updates of the AGCMF, additional guidance in the AGCMF, and the inputs into the development of the annual national exercise program.

- PM&C agreed to all four recommendations. The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) agreed to one recommendation.

9

recommendations in the 2023 AGCMF Review conducted by PM&C.

14

hazards identified under the revised AGCMF released in September 2024 — increasing from 12 in the previous version.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF) outlines the Australian Government’s approach to preparing for, responding to, and recovering from crisis.1 The AGCMF describes an ‘all-hazards’ approach that includes mitigation, planning, and assisting states and territories to manage emergencies resulting from natural events.2

2. The AGCMF has been used to respond to a variety of crises between 2020 and 2023 including:

- the COVID-19 pandemic;

- natural disasters such as prolonged flood events across Australia and tropical cyclone events;

- cyber security incidents including data breaches involving Medibank and Latitude Financial, and the security breach affecting the email gateway system supporting some ACT Government systems; and

- the Turkiye and Syria earthquake for which the Australian Government committed humanitarian assistance.

3. In March 2023, government agreed to conduct a review of the AGCMF. The Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet (PM&C) conducted this review. Following the 2023 AGCMF Review, a revised AGCMF was released at the 2024–25 Higher Risk Weather Season National Preparedness Summit in Canberra on 18–19 September 2024.3

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The AGCMF is the basis for the Australian Government’s response to crises including pandemics, natural disasters, terrorism, and cyber incidents. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on whether Australian Government entities have identified and applied lessons from crises between 2020 and 2023, including the COVID-19 pandemic, to the AGCMF in preparation for future severe to catastrophic crises.

5. In its report on the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management approaches, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) recommended that the Auditor-General consider undertaking a performance audit of the AGCMF, and include within the audit scope whether the updated framework adequately reflects lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.4 The JCPAA also identified an audit of the AGCMF as an audit priority of the Parliament in 2022–23.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess whether the Australian Government has established an appropriate framework for responding to crises.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the readiness of systems and processes to respond to crises been assessed?

- Is the AGCMF fit for purpose to respond to a changing threat environment?

8. The audit examined whole-of-government crisis coordination arrangements established through seven versions of the AGCMF between 2020 and 2023, and the 2023 review of the AGCMF undertaken by PM&C. The audit focussed on whole-of-government crisis coordination arrangements between 2020 and 2023 including the supporting mechanisms to convene key committees under the AGCMF.

9. The audit did not examine:

- the application of the framework to the response to the COVID-19 pandemic or other crises;

- the adherence to individual national plans required under the AGCMF;

- agency specific crisis coordination arrangements; or

- operational responses to crises.

Conclusion

10. In establishing the revised AGCMF, PM&C has developed a largely appropriate framework for responding to crises. The revised AGCMF incorporates lessons from prior crises and provides increased guidance for all-hazards responses, including complex and concurrent crises. The increased oversight and additional continuous improvement activities established in the revised AGCMF will be important to ensure the framework remains appropriate for responding to crises over time as threats and the environment continue to evolve. The revised AGCMF represents a shift in approach from previous versions of the AGCMF and will require sustained effort to build and maintain appropriate capability.

11. A structured assessment of the readiness of systems and processes contained in the AGCMF was not undertaken prior to the 2023 Review. Updates to the AGCMF during 2020 to 2023 were administrative in nature and reflected changes that had already been operationalised. The roles and responsibilities set out under previous versions of the AGCMF were not clearly defined. The 2023 AGCMF Review was guided by a project plan which captured evidence from a range of inputs including comprehensive stakeholder engagement and testing of recommendations and proposed actions. Clarifying arrangements for annual updates and future comprehensive reviews is important to ensure these activities adequately capture and address required changes in a timely manner. The lessons management capability and associated processes are evolving. Formal lessons activities are not conducted for all crises. Thresholds for conducting a lessons process had not been defined or documented prior to 2024.

12. The revised AGCMF released in September 2024 incorporates an increased emphasis on continuous improvement and improved oversight. These amendments, if effectively implemented, should position the framework to respond to a changing threat environment. Activities that informed the 2023 AGCMF Review, such as ‘futures workshops’, would provide value to the framework into the future as they provide an opportunity to examine whether the framework is strategically positioned to adapt to the future. The revised AGCMF introduces several new roles. The responsibilities of these roles are largely clear. Until 2024, there has been a lack of oversight over national level plans to ensure they are reviewed and updated. The annual national exercise program conducted by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) has primarily focussed on natural disaster scenarios. Compounding non-natural disaster specific impacts are now being integrated into natural disaster scenario-based exercises within the program. There is scope to improve the transparency and currency of national plans and risk planning in relation to shared risks and key management personnel risks.

Supporting findings

Readiness of systems and processes

13. Within the AGCMF, specific hazards are identified with lead ministers and entities assigned to these hazards. The emergence of newly identified hazards has led to updates in the AGCMF. Space weather events were added as a specific hazard as they were identified as posing a risk to critical infrastructure. Cyber incidents were added as a specified hazard following a review of crises that indicated roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined. Under previous versions of the AGCMF, triggers and thresholds for activation of whole-of-government crisis coordination were broad and did not provide clear guidance to entities. There are multiple mechanisms that support crisis coordination and response. Some of these mechanisms were not defined in the AGCMF. The role and interactions between various crisis mechanisms could have been more clearly defined. The National Coordination Mechanism (NCM) was introduced as a means to provide broader engagement than previously existing arrangements. The NCM was embedded in the AGCMF after it became a regularly used mechanism during the COVID-19 pandemic response. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.33)

14. Updates undertaken annually between 2020 and 2023 were largely limited to documenting machinery of government changes. These updates varied in the approach and stakeholder engagement. There was no engagement with states and territories as part of the administrative updates in 2020, the second update in 2021 or 2022. More significant comments relating to the framework were held over in anticipation of a future review, which was conducted in 2023. The 2023 AGCMF Review had not been approved at the time. The approach to the 2023 AGCMF Review was guided by a project plan which captured evidence from a range of inputs including comprehensive stakeholder engagement and testing of recommendations and proposed actions. There are minor gaps in documentation relating to the analysis of some of this evidence base. Lessons management, including a lessons management capability, to inform continuous improvement activities is evolving. (See paragraphs 2.34 to 2.79)

15. There are gaps in lesson management at the whole-of-government level. As the lessons management capability matures, implementation of actions to address identified lessons is improving. During crises between 2019 and 2023, an APS Surge Reserve was established from lessons relating to capability across the APS. While intended to provide additional personnel capacity in the event of a crisis, the APS Surge Reserve provides staff with generalist skills. The 2023 AGCMF Review identified a gap in suitably qualified staff for crisis management roles. NEMA has sought opportunities to utilise the Centres for National Resilience for certain crises, however, an agreement to utilise Department of Finance managed centres has not yet been established. NEMA has established the National Emergency Management Stockpile to enable the rapid deployment of resources. (See paragraphs 2.80 to 2.97)

Responding to a changing threat environment

16. Risk assessments do not include potential key management personnel risks. The 2023 ACGMF Review incorporated strategic risk consideration including future scenario planning which had not previously been conducted. The Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) methodology has been embedded in NEMA’s approach to operational response activities, however, the methodology has not yet been established as a consistent planning tool across the range of entities involved in crisis management, or in horizon scanning activities to detect emerging threats. When fully embedded, the CASP methodology has the potential to provide a robust approach to planning and preparedness as well as recovery. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.37)

17. The revised AGCMF provides increased clarity on roles and responsibilities. This includes introduction of a tiered crisis coordination model intended to provide greater flexibility as crises evolve. The revised AGCMF groups key information relating to roles and responsibilities together for an easier read. The Handbook provides additional guidance to senior officials. The revised AGCMF has largely addressed feedback obtained during the 2023 AGCMF Review to improve the clarity of the arrangements for the available crisis mechanisms. PM&C have identified ongoing activities are required to support the implementation of the revised AGCMF including by improving capability. (See paragraphs 3.38 to 3.67)

18. Previous versions of the AGCMF did not establish oversight arrangements for the full suite of national level plans to ensure they are reviewed and updated to respond to future events. The September 2024 version of the AGCMF establishes oversight arrangements. As at July 2024, thirty-two per cent of the publicly available plans have not been updated in the last three years. (See paragraphs 3.68 to 3.80)

19. NEMA delivers two annual national-level exercises primarily focussed on multi-jurisdictional natural disasters. Since 2022 compounding non-natural disaster specific impacts such as mass power outages and supply chain issues have been included in NEMA led exercises. Prior to 2024, there were gaps in the arrangements to identify and prioritise whole-of-government exercises. There are limitations with arrangements to capture information relating to exercises led by other entities, reducing the ability to advise government on the preparedness of Australian Government entities to response to crises. The expanded role of the Crisis Arrangements Committee under the revised AGCMF provides coverage of these gaps. Higher Risk Weather Season (HRWS) preparedness has evolved with the addition of ministerial exercises and the HRWS National Preparedness Summit. (See paragraphs 3.81 to 3.111)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.44

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet:

- document a process for annual administrative updates that provides a consistent approach including ensuring appropriate records of engagement and input are maintained; and

- ensure significant issues are documented to be considered in comprehensive reviews of the AGCMF.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.75

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet:

- provide stronger guidance to entities in their development and updating of entity level and relevant national level crisis management policies and plans; and

- provide a formal response to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit that outlines actions taken to address recommendation three from Report 494: Inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.23

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet embed arrangements for future scenario planning into ongoing review and update arrangements for the AGCMF. These should be appropriately documented to ensure lessons are captured and can be learned.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.79

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet include in the Australian Government Crisis Management Handbook criteria for the publication of plans to appropriately inform stakeholders of crisis arrangements.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.97

The National Emergency Management Agency document its consideration of Crisis Arrangements Committee advice on gaps and priorities for whole-of-government exercising, as well as the annual analysis undertaken to review and update the list of identified hazards under AGCMF, to inform the development of the annual national exercise program. This should include ensuring that exercises consider both natural and all-hazard scenarios.

National Emergency Management Agency response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

20. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the National Emergency Management Agency. Letters of response provided by each entity are included at Appendix 1. The summary responses provided are included below. The improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are at Appendix 2.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) welcomes the proposed report on the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF). PM&C accepts the key findings and recommendations, and has commenced steps to address these matters.

PM&C is committed to strengthening the Australian Government’s crisis management arrangements and preparedness in partnership with other Australian Government agencies. It has undertaken a comprehensive review of the AGCMF, resulting in the development of a new and enhanced Framework, supporting Handbook and more robust continuous improvement processes. It will continue to enhance guidance under these products to guide the publication of plans, assessment of staffing capacities and the development of surge arrangements.

PM&C will also continue to work other relevant agencies, including the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), to enhance guidance on national planning and preparedness activities, including human rights considerations and consider options to clarify crisis responsibilities following machinery of government changes. It will establish improved guidance and repeatable processes for the annual review of the AGCMF, as well as for future comprehensive reviews, to ensure lessons from future scenario planning and exercises are captured. PM&C will also assess its senior staffing capacities in the context of crisis response.

National Emergency Management Agency

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) welcomes the findings of the ANAO Performance Audit of the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF) and is committed to preparing Australia for all hazard crisis events, now and into the future. The Performance Audit complements the recent review of the AGCMF. NEMA will continue to work with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), the Australian Government, jurisdictions, industry and non-government organisations for continuous improvement in crisis management preparedness.

NEMA will work with PM&C to ensure whole-of-government crisis exercising aligns to the priorities identified by the Crisis Arrangements Committee, including consideration of natural and all-hazard impacts and consequences.

Acknowledging the current and future risk of consecutive, compounding and concurrent crises, NEMA will continue building crisis capability within the agency and across the Australian Government. NEMA will work alongside PM&C to assess crisis workforce planning needs and increase crisis workforce capability.

NEMA is committed to building the Australian Government’s strategic crisis planning capability through the Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) methodology. We will continue to support a nationally-consistent approach to planning and preparedness activities through CASP, ensuring Australians and their communities are supported before, during and after crisis events.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

21. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Records management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF) outlines how the Australian Government prepares for, responds to, and supports recovery from crises.5 Crises are characterised by three key conditions; a high degree of danger or threat against something that is desirable to protect, a lack of certainty regarding the specific nature of the threat and its consequence, and time pressure or urgency of counter measures.6 Crises may impact Australia’s economy, security, infrastructure and environment, and can have a significant impact on Australian’s health, wellbeing and livelihoods.7 Crises are often difficult to predict and have no standard response.

1.2 Australia’s threat and risk environment is evolving, resulting in new hazards with increased intensity and duration.8 This includes an increase in concurrent and consecutive hazard events, a changing climatic environment, increased digital connectivity and evolving national security environment.9

1.3 A number of reviews and inquiries into disaster events and crises have highlighted the impact of crises on vulnerable communities, including the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements10 and the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 report.11 Vulnerable communities may have a range of characteristics, such as impaired mobility or sensory awareness, chronic health conditions, or social and economic limitations, that may reduce their ability to prepare for and respond to crises. This can result in a greater risk of loss, injury, illness, and death during crises.12

The Australian Government Crisis Management Framework

1.4 The AGCMF describes an ‘all-hazards’ approach to crisis management that recognises the need for consistency across the Australian Government’s crisis management systems in preparation for the full spectrum of hazards that may affect life, property or the natural environment.13

1.5 In 2008, a Review of Homeland and Border Security14 highlighted the need for a more integrated approach to emergency management. The review highlighted the need for an overarching policy framework and strategic direction to better equip the Australian Government to plan and evaluate the national security activities of agencies and address fundamental gaps in emergency management. The AGCMF resulted from this review. Since its release, the AGCMF has been updated on 11 occasions.15

1.6 The AGCMF has been used to respond to a variety of crises between 2020 and 2023 including:

- the COVID-19 pandemic;

- natural disasters such as prolonged flood events across Australia and tropical cyclone events;

- cyber security incidents including data breaches involving Medibank and Latitude Financial, and the security breach affecting the email gateway system supporting some ACT Government systems; and

- the Turkiye and Syria earthquake for which the Australian Government committed humanitarian assistance.

Australian Government crisis management continuum

1.7 The Australian Government crisis management continuum comprises seven phases of crisis management and recovery.16 These phases are:

Table 1.1: Phases of the Australian Government crisis management continuum and their definitions

|

Phase |

Definition |

|

Prevention |

Measures to eliminate or reduce the severity of a hazard or crisis. |

|

Preparedness |

Arrangements to ensure that, should a crisis occur, the required resources, capabilities and services can be efficiently mobilised and deployed. |

|

Response |

Immediate actions taken to ensure that crisis impacts and consequences are minimised, and that those affected are supported as quickly as possible. |

|

Relief |

Meeting the essential needs of food, water, shelter, energy, communications and medicines for people affected by a crisis event. |

|

Recovery |

Early and longer-term measures to restore or improve the livelihoods, health, economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets, systems and activities, of a disaster-affected community or society. |

|

Reconstruction |

Implementing longer-term strategies post-incident to ‘build back better’ from a crisis, including identifying sustainable development approaches and mitigation measures that may be applicable beyond the directly affected community. |

|

Risk reduction |

Reducing future risk and identifying measures that may be taken to reduce the impact of future crises. |

Source: Australian Government Crisis Management Framework.

1.8 The focus of the AGCMF is near-term crisis preparedness, response, relief and early recovery.17

Roles and responsibilities

1.9 The Australian Constitution establishes the legislative powers of the Parliament of Australia.18 States and territories retain legislative powers over matters not specifically listed in the Constitution. State and territory governments are the first responders to incidents that occur within their jurisdictions. The Australian Government contributes to crisis management during significant crises.

1.10 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) is responsible for setting, and oversight of, whole-of-government crisis management policy, including coordinating updates to the AGCMF.19 The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) is the custodian of Australian Government crisis capabilities that support some or all elements of crisis coordination. This includes administering the National Coordination Mechanism on behalf of Australian Government agencies, the Australian Government National Situation Room and providing guidance on crisis preparation and strategic planning, crisis communication and recovery.20 21

2023 Australian Government Crisis Management Framework review

1.11 In March 2023, government decided to conduct a review of the AGCMF. PM&C conducted this review. The scope of this review was to consider the:

- objectives of the framework;

- triggers for escalation;

- accountabilities of agencies and ministers and mechanisms to resolve accountabilities where they are unclear or overlap during a crisis;

- arrangements for coordinating information, decision-making, reporting and transparency;

- arrangements for the receipt, coordination and deployment of international assistance; and

- gaps in the framework including providing confidence the framework can deal with crisis at scale, multiple crises and new and emerging vectors.

1.12 Following the 2023 AGCMF Review, a revised Australian Government Crisis Management Framework was released at the 2024–25 Higher Risk Weather Season National Preparedness Summit in Canberra on 18–19 September 2024.

Other scrutiny

1.13 The operations of the crisis management framework — including in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic response — have been subject to external scrutiny such as:

- Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements February 2020;

- Senate Select Committee on COVID-19; and

- Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements.

1.14 The Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements was established on 20 February 2020 to inquire into and report on national natural disaster arrangements at all phases of disaster management, including mitigation, adaptation, preparedness, response and recovery, and make recommendations about any policy, legislative, administrative or structural reforms the Commissioners deemed appropriate.22 The report was published on 28 October 2020.

1.15 The Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 was established on 9 April 2020 to inquire into and report on the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.23 The Committee undertook public hearings and received submissions from a range of stakeholders. The Committee released its final report in April 2022.24

1.16 The JCPAA undertook an inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements, based on the findings and recommendations made in Auditor-General Report No. 39 2021–22 Overseas Crisis Management and Response: The Effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Management of the Return of Overseas Australians in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.25

1.17 The Commonwealth Government COVID-19 Response Inquiry was announced on 21 September 2023. The inquiry will review the Commonwealth Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and make recommendations to improve response measures in the event of future pandemics.26

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 The AGCMF is the basis for the Australian Government’s response to crises including pandemics, natural disasters, terrorism, and cyber incidents. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on whether Australian Government entities have identified and applied lessons from the crises between 2020 and 2023, including the COVID-19 pandemic, to the AGCMF in preparation for future severe to catastrophic crises.

1.19 In its report on the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management approaches, the JCPAA recommended that the Auditor-General consider undertaking a performance audit of the AGCMF, and include within the audit scope whether the updated framework adequately reflects lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.27 The JCPAA also identified an audit of the AGCMF as an audit priority of the Parliament in 2022–23.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The audit objective was to assess whether the Australian Government has established an appropriate framework for responding to crises.

1.21 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the readiness of systems and processes to respond to crises been assessed?

- Is the AGCMF fit for purpose to respond to a changing threat environment?

1.22 The audit examined whole-of-government crisis coordination arrangements and the 2023 review of the AGCMF being undertaken by PM&C. The audit focussed on whole-of-government crisis coordination arrangements between 2020 and 2023 (i.e. excluding agency-specific crisis coordination arrangements) including the supporting mechanisms to convene key committees under the AGCMF.

1.23 The audit did not examine:

- the application of the framework to the response to the COVID-19 pandemic or other crises;

- the adherence to individual national plans required under the AGCMF;

- agency specific crisis coordination arrangements; or

- operational responses to crises.

Audit methodology

1.24 The audit involved:

- reviewing records concerning the administration of the AGCMF, particularly relating to updates to the AGCMF between 2020 and 2023, and the 2023 review of the AGCMF; and

- meetings with key Australian Government officials involved in whole-of-government crisis coordination arrangements and the review of the AGCMF.

1.25 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $440,165.

1.26 The team members for this audit were Jacqueline Hedditch, Jade Ryan, Mary Potter, and Corinne Horton.

2. Readiness of systems and processes

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the readiness of systems and processes to respond to crises has been assessed. Systems and processes for crisis response are contained within the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF).

Conclusion

A structured assessment of the readiness of systems and processes contained in the AGCMF was not undertaken prior to the 2023 Review. Updates to the AGCMF during 2020 to 2023 were administrative in nature and reflected changes that had already been operationalised. The roles and responsibilities set out under previous versions of the AGCMF were not clearly defined. The 2023 AGCMF Review was guided by a project plan which captured evidence from a range of inputs including comprehensive stakeholder engagement and testing of recommendations and proposed actions. Clarifying arrangements for annual updates and future comprehensive reviews is important to ensure these activities adequately capture and address required changes in a timely manner. The lessons management capability and associated processes are evolving. Formal lessons activities are not conducted for all crises. Thresholds for conducting a lessons process had not been defined or documented prior to 2024.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) documenting a process for annual administrative updates and providing guidance to entities for the consideration of human-rights in entity-level and relevant national-level crisis management policies and plans.

The ANAO also identified an opportunity for improvement for PM&C to work with the Department of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission to consider machinery of government guidance and associated guidance to entities to ensure crisis responsibilities are captured.

2.1 The nature of a crisis requires a quick response to minimise impacts and provide support for those affected.28 Readiness of systems and processes includes establishing arrangements to ensure that the required resources, capabilities, and services can be efficiently mobilised and deployed.29 Clear definitions of roles and responsibilities and regular reviews of arrangements, including processes to identify and learn lessons, are important to ensure that Australia is ready to respond to increasingly severe and complex crises often with events occurring concurrently.30

2.2 This chapter relates to versions of the AGCMF in effect between 2020 and 2023 and the review processes related to these versions.

Were roles and responsibilities clearly defined in previous versions of the AGCMF?

Within the AGCMF, specific hazards are identified with lead ministers and entities assigned to these hazards. The emergence of newly identified hazards has led to updates in the AGCMF. Space weather events were added as a specific hazard as they were identified as posing a risk to critical infrastructure. Cyber incidents were added as a specified hazard following a review of crises that indicated roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined. Under previous versions of the AGCMF, triggers and thresholds for activation of whole-of-government crisis coordination were broad and did not provide clear guidance to entities. There are multiple mechanisms that support crisis coordination and response. Some of these mechanisms were not defined in the AGCMF. The role and interactions between various crisis mechanisms could have been more clearly defined. The National Coordination Mechanism (NCM) was introduced as a means to provide broader engagement than previously existing arrangements. The NCM was embedded in the AGCMF after it became a regularly used mechanism during the COVID-19 pandemic response.

2.3 The AGCMF was first released in 2010 following the 2008 Australian Government Review of Homeland and Border Security. The AGCMF has been updated on 11 occasions since the previous format31 was released in 2012. This includes five updates in the period 2020 to 2023.32 The updates were published in:

- October 2020;

- July 2021;

- December 2021;

- November 2022; and

- September 2023.

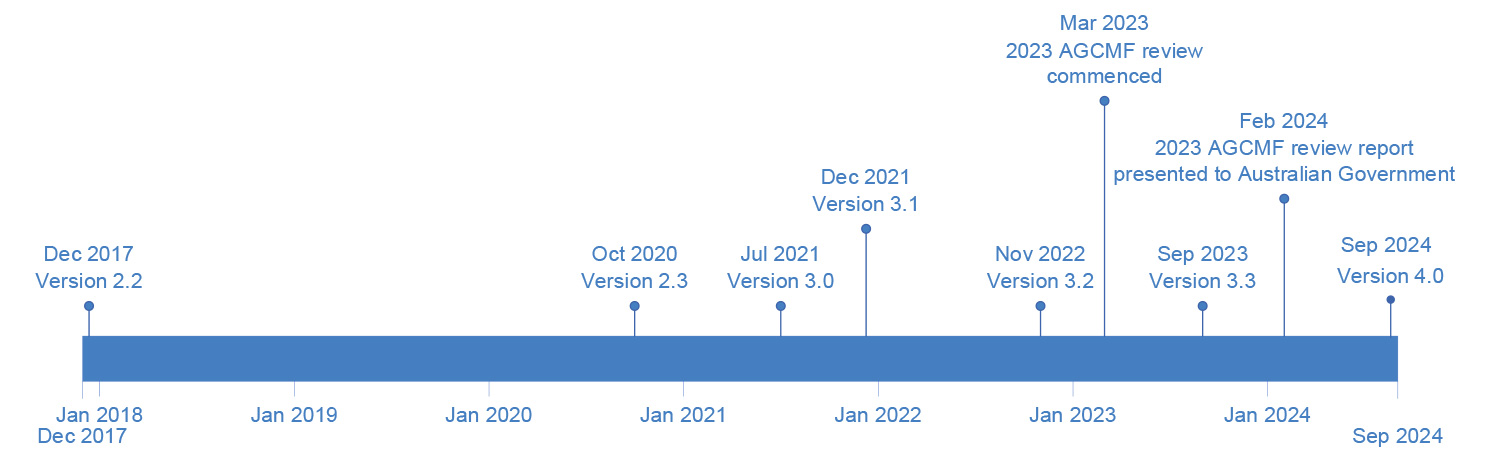

2.4 In 2023, PM&C commenced the first comprehensive whole-of-government review of the AGCMF since its establishment. A timeline of updates to the AGCMF is outlined in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Timeline of updates to the AGCMF

Source: ANAO.

Oversight roles

2.5 PM&C is responsible for whole-of-government national security and intelligence policy coordination. The Resilience and Crisis Management Division in PM&C has:

policy responsibility for Australian Government crisis management arrangements and continuity of executive government, coordinates across government to support continuous improvement and reform of Commonwealth disaster management policy and capability. This includes undertaking a comprehensive review of the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework and leading the National Preparedness Taskforce.

2.6 PM&C is responsible for setting, and oversight of, whole-of-government crisis management policy, in accordance with the AGCMF.33

2.7 The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) was established on 1 September 2022 to provide national leadership and strategic coordination for emergencies and disaster preparedness, response, relief, recovery, reconstruction, risk reduction and resilience.34 NEMA was created by combining the National Recovery and Resilience Agency (NRRA) and the Emergency Management Australia (EMA) division of the Department of Home Affairs.35

2.8 NEMA has defined one of its strategic objectives as ‘leading and coordinating national action and assistance across the emergency management continuum.’36 References to NEMA were included throughout the AGCMF for specific activities, such as:

- developing and delivering the annual national exercise program (see paragraphs 3.81 to 3.111);

- maintenance of the Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning methodology (see paragraphs 3.25 to 3.35);

- operating the Australian Government National Situation Room (see paragraph 3.37);

- working with lead agencies to capture observations as part of the lessons management process (see paragraphs 2.64 to 2.68); and

- chairing or co-chairing relevant crisis committees (see paragraphs 2.20 to 2.33).

2.9 NEMA also has responsibility for specific national-level crisis plans (see paragraphs 3.68 to 3.80).

2.10 As outlined in paragraph 1.9, state and territory governments retain primary responsibility for the protection of life, property and the environment. The Australian Government provides support to states or territories where the nature of the crisis has or is expected to exceed the sovereign capacities of the state or territory to manage.

Lead ministers and agencies

2.11 Under the AGCMF, a lead minister is responsible for the coordination of the Australian Government’s near-term crisis preparation, immediate crisis response, and early recovery from a crisis arising from specific hazards. The lead minister is determined by the nature of the hazard or hazards. The lead minister is responsible for overseeing the coordination and delivery of the Australian Government response in conjunction with state and territory counterparts, exercise executive responsibilities in consultation with ministers with relevant portfolio interests and representing the Australian Government as the key spokesperson.

2.12 Under previous versions of the AGCMF, ministerial and lead agency responsibilities for specified hazards were outlined in Annex C.37 The minister responsible for Home Affairs, supported by the minister responsible for Emergency Management, is the lead minister where there is no clear ministerial lead for a domestic crisis.

2.13 The lead agency is also determined by the nature of the hazard or hazards. Prior to September 2024, lead agencies were responsible for:

- coordinating, leading and implementing whole-of-government response actions and overseeing the strategic response to a crisis;

- providing support and advice to lead ministers, preparing and exercising plans to manage all-hazards38;

- providing subject matter expertise;

- ensuring that ministerial directions and decisions are implemented;

- exercising relevant powers and decision-making responsibilities;

- working with jurisdictional partners to inform Australian Government situational awareness; and

- contributing to predictive analysis and decision support through effective information sharing.

2.14 In 2020, ten specific hazards were identified in the AGCMF.39 Space weather events were added as a hazard in July 2021, and cyber incidents were added in September 2023. Space weather events were added as a specific hazard as they were identified as posing a risk to critical infrastructure.40 Cyber incidents were added as a specific hazard following a review of significant cyber incidents which indicated that cyber incident response roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined.41

2.15 While new hazards have been identified and specific response plans have been developed, there has been no review of the appropriateness of the collective suite of existing plans (see paragraphs 3.72 to 3.78 for further detail). As outlined in paragraph 2.41, machinery of government changes have resulted in some conflict in relation to roles and responsibilities for specified hazards. Under the revised AGCMF released in September 2024, the Crisis Arrangements Committee has an expanded role in relation to crisis plans (see paragraphs 3.58 to 3.59).

Triggers and thresholds for activation

2.16 Triggers for activating a whole-of-government coordination response are identified in the AGCMF. These triggers remained the same between December 2017 and September 2023. Potential triggers for activating a whole-of-government coordination response included:

- the scale of the crisis and its potential or actual impact on Australia, Australians, or Australia’s national interests;

- formal ministerial consideration of the event;

- a crisis affecting multiple jurisdictions or industry sectors;

- a request from an affected nation, state and/or territory for Australian Government capabilities or assistance;

- a crisis with both domestic and international components;

- a crisis resulting in a large number of Australian casualties;

- community expectations of national leadership; or

- multiple crises occurring simultaneously which require coordination, resource prioritisation and de-confliction.

2.17 Previous versions of the AGCMF outlined that entities ‘may also choose to escalate issues where there is a novel event or crisis for which a specific Government plan does not exist.’ Previous versions of the AGCMF did not provide further guidance for entities to escalate such issues or detail on which supporting arrangements such as crisis committees may be utilised.

2.18 Triggers and thresholds for activation have been updated in the revised AGCMF released in September 2024 (see paragraph 3.55).

Crisis mechanisms

2.19 Crisis mechanisms such as crisis committees support crisis preparedness and response activities. The AGCMF identified some of these crisis mechanisms. Other mechanisms also operated in support of the AGCMF, however, were not defined in the AGCMF. These can be categorised as one of three types of mechanisms.

- Australian Government — these mechanisms and committees include representatives from Australian Government entities.

- National — these mechanisms and committees include representatives from Australian Government entities, states and territories, and where relevant may include other external stakeholders such as industry and non-government organisations.

- State and territory — these mechanisms and committees relate to states and territories.42

Australian Government crisis mechanisms

Crisis Arrangements Committee

2.20 The Crisis Arrangements Committee (CAC) is intended to provide strategic direction in the development of coordinated Australian Government crisis management arrangements. The CAC was formed in 2015 to assist in developing coordinated, whole-of-government approaches to Australian Government crisis management matters. Membership includes Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2 or 3 level officials from agencies with roles in crisis or emergency management matters.

2.21 PM&C advised the ANAO on 27 February 2024 that prior to its re-establishment in 2023, the CAC last met in December 2019. The CAC was re-established in June 2023 to provide whole-of-government oversight of the 2023 AGCMF Review. Prior to September 2024, the CAC was not defined in the AGCMF.

Australian Government Crisis and Recovery Committee

2.22 The Australian Government Crisis and Recovery Committee (AGCRC) was the ‘primary mechanism for bringing together relevant Australian Government Agency representatives, primarily in response to domestic crises’.43 The AGCRC did not have a formalised terms of reference to guide its operations. The scope of the AGCRC was defined as ‘crisis with a predominantly domestic impact’ under the AGCMF. The AGCRC provided similar operational support to what is now the NCM (see paragraphs 2.22 to 2.23).

2.23 During the 2023 AGCMF Review, entity consultation identified that the existence and usage of multiple coordination groups, particularly at the senior officials’ level which includes the AGCRC, may cause confusion and duplication. The consultation feedback highlighted issues around the clarity of purpose and quantity of committees and mechanisms in place for crisis response and coordination. The AGCRC has since been replaced by an NCM function known as NCM-AUSGOV (see paragraphs 3.65 to 3.67).

Inter-Departmental Emergency Task Force

2.24 An Inter-Departmental Emergency Task Force (IDETF) ‘manages the whole-of-government response to overseas incidents or crises that impact or threaten to impact Australians or Australia’s interests overseas.’ An IDETF is chaired by the Deputy Secretary Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), and may be co-chaired by the Deputy Secretary PM&C.

2.25 As part of the 2023 AGCMF Review (see paragraphs 2.48 to 2.63), DFAT provided feedback to PM&C that indicated further clarity around the triggers for and identification of participants in an IDETF may be beneficial. DFAT also queried whether both the AGCRC and the IDETF were necessary.

National crisis mechanisms

National Cabinet

2.26 The National Cabinet is a mechanism comprising the Prime Minister, state premiers and territory chief ministers. The National Cabinet held its first meeting on 15 March 2020.44 On 29 May 2020, the Prime Minister announced that National Cabinet would replace the Council of Australian Government (COAG).45 The role of COAG was not defined in the AGCMF.

2.27 In the October 2020 version of the AGCMF, the National Cabinet was referenced only in a note to a visual representation of the relationship between state and territory coordination arrangements, entity led coordination, and whole-of-government coordination, stating that ‘in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Cabinet was convened to support coordination between First Ministers.’

2.28 The July 2021 version of the AGCMF included the National Cabinet as an option to ‘ensure coordinated, timely action across Australian governments where cooperation across all states and territories is required.’ The wording remained through to the September 2023 version. There was no further guidance as to the scope or role of the National Cabinet in a crisis or its link to other committees within crisis coordination arrangements.

2.29 The National Security Committee (NSC) is a committee of Cabinet. The role of the NSC is to consider the highest-priority, highest-risk and most strategic national security matters of the day.46 Prior to 2024, the NSC was not specifically identified in the AGCMF, however, has acted as one of the key decision-making committee’s during crises.47

National Coordination Mechanism

2.30 The AGCMF stated that:

in some cases it may still be appropriate for the Prime Minister, or the Minister leading the response to a crisis, to establish special purpose / temporary response mechanisms in parallel with existing response mechanisms (AGCC, NCC or IDETF). Special purpose/temporary mechanisms may include, for example: the appointment of a special envoy; an ad hoc Secretaries’ coordination meeting; and/or a dedicated whole-of-government taskforce. Any special purpose/temporary mechanisms should be guided by existing arrangements, to ensure a consistent and effective whole-of-government response.48

2.31 The NCM was established on 5 March 2020 as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response.49 The intent of the NCM was to operationalise plans used during the COVID-19 pandemic and coordinate Commonwealth agencies’ planning and preparedness measures for non-health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The NCM was formally embedded in the October 2020 version of the AGCMF. NEMA administers the NCM on behalf of Australian Government entities. The relevant Deputy Coordinator-General NEMA convenes or chairs the NCM. The Deputy Secretary PM&C may elect to co-chair the NCM.

2.32 The Department of Home Affairs drafted Terms of Reference (ToRs) for the NCM in March 2020. The draft ToRs were returned to the NCM in May 2020 as ‘not endorsed’ with a note that they were ‘not required’.50 On 18 July 2024, NEMA advised the ANAO that the NCM does not fit within the typical construct for government committees and is not designed for stakeholders to have a ‘seat at the table’ and that ToRs for the NCM ‘would not be appropriate for its modality’. The NCM continues to operate under a national coordination and domain concept, which is a visual representation of the groups that may participate in the NCM.51

2.33 Prior to the establishment of the NCM, the National Crisis Committee (NCC) was the committee by which Australian Government and relevant state and territory government coordination in response to domestic crises would occur. As part of the 2020 administrative update of the AGCMF (see paragraph 2.36), entity feedback highlighted that there was a lack of clarity between the NCC and NCM which could create a ‘real risk’ during a crisis. The NCC was included in the AGCMF until July 2021.

Were updates to the AGCMF informed by evidence and analysis?

Updates undertaken annually between 2020 and 2023 were largely limited to documenting machinery of government changes. These updates varied in the approach and stakeholder engagement. There was no engagement with states and territories as part of the administrative updates in 2020, the second update in 2021 or 2022. More significant comments relating to the framework were held over in anticipation of a future review, which was conducted in 2023. The 2023 AGCMF Review had not been approved at the time. The approach to the 2023 AGCMF Review was guided by a project plan which captured evidence from a range of inputs including comprehensive stakeholder engagement and testing of recommendations and proposed actions. There are minor gaps in documentation relating to the analysis of some of this evidence base. Lessons management, including a lessons management capability, to inform continuous improvement activities is evolving.

2.34 As the AGCMF has been utilised to support a range of crises between 2020 and 2023 (see paragraph 1.6), there is a base of actual experiences available to examine and analyse in order to identify examples of good practice and opportunities for improvement to be adopted in updates.

Updates to the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework

2.35 The December 2017 version of the AGCMF stated that the framework is ‘updated as necessary to maintain its relevance and currency and may be comprehensively reviewed every three years if required.’ 52

2.36 In 2020, PM&C wrote to four entities to provide input to an administrative update led by PM&C. These entities were the Department of Home Affairs53, Department of Health, Department of Defence, and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

2.37 An agenda for a 3 September 2020 Interdepartmental Committee (IDC) meeting was prepared to discuss:

- entity comments and proposed amendments,

- changes to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) architecture and establishment of the National Federation Reform council, and

- interim decisions on disaster management.

2.38 There are no meeting minutes or outcomes arising from the IDC meeting.

2.39 A requirement to conduct an annual review of the AGCMF was introduced in 2021.54 Prior to 2021, there was no time-based requirement to review and update the AGCMF.

2.40 The AGCMF was updated twice in 2021 — once in July 2021 which saw an update from version 2.3 to 3.0 (considered by PM&C to be a ‘more comprehensive review’) and again in December 2021 which saw an update from version 3.0 to 3.1 (considered by PM&C to be an administrative update).

2.41 In 2022, PM&C wrote to thirteen entities to comment on an updated draft of the AGCMF. As part of the PM&C clearance process, sensitivities relating to machinery of government (MoG) changes between Home Affairs and Attorney-General’s portfolios were identified as ‘difficult to reconcile within the scope’ of the 2022 administrative update. PM&C noted that ministerial and agency lead responsibilities remained unchanged and would require further consideration in a more extensive review proposed to commence in early 2023. At this time, the 2023 AGCMF Review had not been approved.

2.42 The 2023 annual administrative update was undertaken concurrent to the 2023 AGCMF Review (see paragraphs 2.48 to 2.63). Twenty-two Australian Government entities were provided with the opportunity to comment on an updated draft of the AGCMF. Some comments made by entities as part of this update were to be considered as part of the 2023 AGCMF Review.55

2.43 PM&C does not have a documented process for undertaking administrative updates. The level of stakeholder engagement in each of the annual administrative updates varied. As there was no process documentation, it is not clear how and why stakeholders were identified for inclusion in each administrative update.

Recommendation no.1

2.44 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet:

- document a process for annual administrative updates that provides a consistent approach including ensuring appropriate records of engagement and input are maintained; and

- ensure significant issues are documented to be considered in comprehensive reviews of the AGCMF.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

2.45 PM&C will review and document the processes for annual administrative reviews and updates of the AGCMF. These processes will include the documentation of significant issues to be considered in future comprehensive reviews.

2.46 Machinery of government changes often result in changes to roles and responsibilities between ministers and their relevant departments. In previous versions of the AGCMF, PM&C had not established triggers to prompt an administrative update of the AGCMF, other than noting the requirement to conduct a review annually. The revised AGCMF released in September 2024, states that machinery of government changes may prompt an administrative update of the AGCMF.

Opportunity for improvement

2.47 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet work with the Department of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission to consider including references to the AGCMF in the guidance to entities for implementing machinery of government changes so that those with new crisis responsibilities are clear on their role in a crisis.

2023 AGCMF Review

2.48 On 27 March 2023, the Australian Government agreed to a review of the AGCMF to be led by PM&C, with staff seconded from relevant agencies. The review was framed as a ‘comprehensive review’. The AGCMF Review team comprised of seconded officers from NEMA, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the Department of Home Affairs.56

Project management

2.49 PM&C developed a project plan for undertaking the review which defined five stages for delivery of the review. These stages, activities and timing are outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Stages, planned activities and planned timings for the 2023 AGCMF Review

|

Stage |

Activities |

Timing |

|

Environmental scan |

|

July 2023 |

|

Insights |

|

August to September 2023 |

|

Options |

|

September to October 2023 |

|

Recommendations |

|

November to December 2023 |

|

Enhanced crisis framework |

|

Through to June 2024. |

Source: PM&C documentation.

2.50 The AGCMF review team developed a ‘placemat’ which was updated on several occasions to reflect updates to work conducted and planned. The first of these was titled ‘initial draft’ and is dated 21 July 2023. The ‘placemat’ was updated on 25 July 2023 and four times in August 2023.57 The ‘placemat’ was used to summarise emerging findings from the review based on the desktop research and consultation conducted by the review team. The emerging findings subsequently formed the basis of the 2023 AGCMF Review report.

2.51 While the placemats and report refer to lessons identified from the review of four prior crises (conducted as part of issues exploration and identification in the environmental scan phase as outlined in Table 2.1), it is unclear what analysis was conducted over these lessons to validate and contextualise them. Recurring themes identified during consultation with entities were reflected in the placemats and report. Comparison activities with international crisis management arrangements were also referenced, however, there were limitations with the documentation relating to this input.

2.52 PM&C considered the crisis management arrangements of the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, Singapore, and the Republic of South Korea (environmental scan as outlined in Table 2.1). The 2023 AGCMF Review Report also refers to input from New Zealand and the United States, however, there was no evidence of input received from these countries.

Environmental scan phase

2.53 As part of the environmental scan phase, PM&C conducted consultation with Australian Government entities as well as states and territories, industry stakeholders and non-government organisations.

2.54 In July 2023, PM&C advised the CAC of emerging insights, which included ‘desire for increased clarity in the interface with State and Territory arrangements.’ This ‘desire’ was identified in consultation with Australian Government entities. Consultation with states and territories subsequently took place in September 2023.

Insights phase

2.55 Following the consultation undertaken as part of the environmental scan phase, PM&C developed an ‘observations report’ that provided a summary of observations from the consultation with Australian Government entities. This report was provided to the CAC in September 2023. A summary of observations is outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Summary of observations from entity engagement as presented to the Crisis Arrangements Committee

|

Category |

Observations |

|

Awareness and useability |

|

|

Gaps for future risks |

|

|

Scope and structure |

|

|

Governance and coordination |

|

|

Capability and improvement |

|

Note a: This observation was included under both ‘Awareness and useability’ and ‘Gaps for future risks’.

Source: ANAO summary of PM&C documentation.

2.56 In September 2023, PM&C presented an update on the 2023 AGCMF Review to the CAC. The update stated that ‘a number of pieces of analysis are feeding into the AGCMF Review including workshops, international comparisons and engagement with non-Government stakeholders and industry partners.’ There was consultation with all Australian states and territories and input from Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia. This input was provided in September 2023, after the need for clarity relating to the interface with states and territories was reported to the CAC. There is no evidence of input from the remaining states and territory.

Options phase

2.57 The project plan outlined that the options phase would include developing options that address key themes and insights; testing options with stakeholders using scenarios; and drafting a report.

2.58 PM&C developed a ‘preliminary model’ for testing with the Deputy Coordinator-General NEMA in September 2023.

2.59 PM&C developed a document titled ‘Next steps and suggested recommendations options’. This document builds on the thematic categories outlined in Table 2.2 and was presented to the CAC. This document was intended to inform discussions between PM&C and NEMA and to inform ‘co-design’ sessions with selected entities.58 PM&C facilitated two co-design workshops — the first on 4 October 2023 and the second on 13 October 2023.

2.60 The first workshop involved a discussion on ‘key’ draft recommendations and potential options to improve the AGCMF. The draft recommendations and whether it was supported by participants is outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Draft recommendations and support from workshop participants

|

Recommendation |

Support from workshop participants |

|

Tiered, scalable model for whole of government response |

Supported in principle |

|

Ability to pivot response from hazard management to consequence management |

Supported in principle |

|

Triggers and thresholds for escalation |

Supported in principle |

|

One lead coordination body for severe to catastrophic, novel or cross-sectoral crises |

Supported in principle |

|

Mechanisms for advising and reporting to government |

Requires refinement |

|

Activation vs Notification |

Supported in principle |

|

Provision of operational guidance for crisis response |

Requires refinement |

Source: ANAO summary of PM&C documentation.

2.61 The second workshop was referred to as a ‘futures workshop’. This workshop was intended to explore future scenarios based on input from the national intelligence community. PM&C advised the ANAO on 19 February 2024 that as this workshop was based on a classified scenario, no documentation was developed as an input to the workshop.

2.62 Proposed recommendations were presented to and agreed by the CAC in November 2023.59 A summary of the recommendations presented to the CAC are outlined in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Summary of recommendations presented to the CAC in November 2023

|

Recommendation number |

Summary of recommendation |

|

1 |

Reaffirm the status of the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework as the Australian Government’s capstone policy framing Australia’s national crisis management arrangements. This included an updated framework and new Australian Government Crisis Management Handbook. |

|

2 |

Clarify and codify a coordinated approach to whole-of-government crisis communication and public messaging, including clearly articulating communications-related roles and responsibilities during a crisis. |

|

3 |

Clarify the role of the National Security Committee of Cabinet (NSC) during crises. |

|

4 |

Introduce a new tiered scalable crisis response model in the framework. |

|

5 |

Establish NEMA as the lead coordination agency for Australian Government responses to cross-sectoral, concurrent and catastrophic crises. |

|

6 |

Address gaps identified during the 2023 AGCMF Review including the establishment of new national plans. |

|

7 |

Establish continuous improvement and exercising of Australia’s crisis management arrangements. |

|

8 |

Improve crisis management capability, capacity and surge workforce arrangements. |

|

9 |

Formalise the Crisis Arrangements Committee (CAC) as the peak whole-of-government senior officials’ body for crisis management planning and preparedness. |

Source: ANAO summary of PM&C documentation.

Recommendations phase

2.63 PM&C presented the 2023 AGCMF Review Report to the Australian Government in February 2024. The report and its recommendations were noted.

Lessons management processes and capability

2.64 Lessons management is an overarching term that refers to collecting, analysing, disseminating, and applying learning experiences from events, exercises, programs and reviews.60 A lesson is knowledge or understanding gained by experience. An experience may be positive or negative. The concept of lessons learned requires two components — the identification of a lesson and resulting change in behaviour.61

2.65 Version 3.0 of the AGCMF introduced a requirement for the lead minister’s entity to work with NEMA to capture lessons learned in the management of crisis as part of the government’s commitment to continuous improvement.62

2.66 NEMA utilises the Observations – Insights – Lessons Identified – Lessons Learned (OILL) methodology as set out in the Australian Disaster Resilience Handbook for Lessons Management.63 The OILL methodology is intended to provide a repeatable process NEMA can use throughout and following crises.

2.67 On 26 February 2024 NEMA advised the ANAO that a lessons process is applied to some but not all events or crises. NEMA further advised on 18 July 2024 that a general guiding principle was that a lessons process be conducted for activations of the Crisis Coordination Team and events of national significance. NEMA had not documented or defined what it considered to be events of national significance. NEMA is refining its lessons approach following the 2023 AGCMF Review, noting the recommendation for lessons to be conducted following Tier 4 events (see Table 3.3).

2.68 On 18 July 2024, NEMA advised the ANAO that it also utilises adaptive and agile lessons processes to implement strategic and operational changes during or as close as possible to a crisis occurring. For example, in December 2022 NEMA provided support to New South Wales and Victoria in response to flooding on the Murray River. Following these requests for assistance, NEMA developed a new internal product to assess the likelihood of future assistance from South Australia as flood waters moved down the Murray River. This internal product allowed NEMA to identify potential types of requests for assistance and map against expected flood levels and timing based on inputs from the Australian Climate Service.

Implementation of recommendations from external scrutiny

2.69 As discussed in paragraphs 1.13 to 1.17, the Australian Government response to crises (including the COVID-19 pandemic) has been subject to scrutiny such as parliamentary inquiries and Royal Commission reviews, that have resulted in recommendations relating to crisis management.

2.70 In March 2023, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) presented Report 494: Inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements. The JCPAA recommended that PM&C, in the 2023 review of the AGCMF, incorporate human rights considerations in the framework, and outline measures to ensure that any crisis response limiting or restricting human rights is necessary, reasonable and proportionate.64

2.71 The JCPAA also recommended that PM&C should require relevant entities to update their entity-level crisis management policies and plans to reflect this change. The government has not provided a response to this recommendation.65

2.72 PM&C advised the ANAO on 5 April 2024 that:

the new principles for the revised framework endorsed by the Crisis Arrangements Committee in June 2023 stated that the Framework:

- Acknowledges community at the core of a response and considers the particular needs of vulnerable and disadvantaged Australians

- Recognises the importance of engaging with First Nations people and their communities before, during and after emergencies.

2.73 The principles outlined in the revised AGCMF include that the framework ‘acknowledges human rights considerations to ensure that measures enacted during crises are necessary, reasonable and proportionate’. There is no further information relating to the consideration of human rights.

2.74 The JCPAA recommendation was not identified in the ToRs or other planning documentation for the 2023 AGCMF Review. In September 2024 the CAC ToRs were updated to incorporate human rights considerations. The ToRs state that ‘the CAC has agreed to invite a representative from appropriate agencies to provide advice on human rights considerations relating to crisis arrangements’.

Recommendation no.2

2.75 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet:

- provide stronger guidance to entities in their development and updating of entity level and relevant national level crisis management policies and plans; and

- provide a formal response to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit that outlines actions taken to address recommendation three from Report 494: Inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

2.76 PM&C is working with NEMA to develop stronger guidance for agencies on national plans and policy, through the current review of the National Plan Guidelines. This will include guidance on the consideration of human rights. PM&C has updated the terms of reference for the Crisis Arrangements Committee (CAC) to include a representation from the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) to support consideration of human rights in strategic crisis preparedness and planning activities.

2.77 PM&C will provide a formal response to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit that outlines these actions which address Recommendation 3 from Report 494: Inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements.

2.78 The Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements (the Commission) report was published 28 October 2020. The Commission was established in response to the 2019–2020 bushfires, however, extended its scope to include natural disaster management. The role of the Australian Government was highlighted as necessary to ensure the coordination of whole-of-government cooperation and effort.

2.79 The Commission made 80 recommendations in total. Sixty-five were the responsibility of state and territory governments either independently or in partnership with the Australian Government. The Australian Government assumed primary responsibility for the remaining 15. The commission did not make any specific recommendations relating to the AGCMF. However, in recommendation 24.1, the Commission noted that the Australian Government should establish accountability and assurance mechanisms to promote continuous improvement and best practice in natural disaster arrangements. An interim report prepared by NEMA on 20 October 2023 that outlines the status of implementation of recommendations stated that the 2023 AGCMF Review would address this recommendation. The status of the recommendation was recorded as implemented.66

Were lessons relevant to the AGCMF applied?

There are gaps in lesson management at the whole-of-government level. As the lessons management capability matures, implementation of actions to address identified lessons is improving. During crises between 2019 and 2023, an APS Surge Reserve was established from lessons relating to capability across the APS. While intended to provide additional personnel capacity in the event of a crisis, the APS Surge Reserve provides staff with generalist skills. The 2023 AGCMF Review identified a gap in suitably qualified staff for crisis management roles. NEMA has sought opportunities to utilise the Centres for National Resilience for certain crises, however, an agreement to utilise Department of Finance managed centres has not yet been established. NEMA has established the National Emergency Management Stockpile to enable the rapid deployment of resources.

2.80 As noted in paragraph 2.64, the concept of lessons learned requires two components — the identification of a lesson and resulting change in behaviour.

2.81 Gaps in lessons management at the whole-of-government level were identified as part of the 2023 AGCMF Review. This included reporting to the CAC in September 2023 that ‘we aren’t very good at ‘learning our lessons’ from major crisis responses’. The 2023 AGCMF Review report included a recommendation for lessons identified to be recorded to inform updates to the Framework and Handbook.

2.82 Reviews of the AGCMF were administrative in nature between 2020 and 2023. There was an absence of process to capture lessons relating to the operations of the framework at the whole-of-government level. The application of lessons to the AGCMF were primarily driven by lessons identified by, or recommendations from, external scrutiny.

NEMA lessons implementation

2.83 As outlined in paragraph 2.67, a lessons process is applied to some but not all events or crises. Where a lessons process is conducted, NEMA develops insight reports as part of the lessons learned process.67 One purpose of these reports is to validate and prioritise the insights among senior executive and subject matter experts, and that separate pieces of work will progress the actions and lessons identified that may result from these reports.

2.84 Although NEMA has captured a large volume of insights from prior crises, it is not clear that all insight reports progress to lessons identification and development of recommendations. On 26 February 2024, NEMA advised the ANAO that it considers lessons management to be a maturing process.

2.85 An example of where NEMA has identified insights that have transitioned to lessons identification and some lessons have been learned is outlined in Case Study 1.

|

Case study 1. Lessons learned from the 2022 east coast floods |

|

In February 2022, the Director-General Emergency Management Australia (EMA) activated the Australian Government Disaster Response Plan (COMDISPLAN) in anticipation of requests for non-financial assistance from states affected by severe rain and flooding. EMA produced an insights report following the event. The insights report included 246 observations that informed 17 insights. The insights report informed the development of a lessons and recommendation report. Five whole-of-government lessons were identified, and 11 recommendations were made. Although there is no evidence of further reporting against the lessons and recommendations report that demonstrates active tracking of recommendations, six of the relevant recommendations made in relation to NEMA (then EMA) that relate to the scope of the AGCMF audit have either been implemented or are in the process of being implemented. These recommendations include:

Two recommendations have been considered as part of the 2023 AGCMF Review. These include that PM&C should update the AGCMF to reflect machinery of government changes and continuous improvement, and improvements to whole-of-government talking points. In the absence of tracking, the status of the following recommendations could not be determined.

|

Capacity and capability related recommendations

2.86 The NEMA Corporate Plan 2023–24 to 2026–27 states that a robust, tested and collaborative national emergency management capability and capacity is critical for Australia to be ready to respond and recover from increasingly intense and severe disasters.68 Emergency management capability and capacity includes people and assets to support coordination and response activities.

People

2.87 The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the operation of the Australian Public Service (APS), which needed to deploy staff on a large scale to support critical functions and quickly adapt to operating in a COVID-safe environment.69

2.88 Auditor-General Report No. 20 2020–21 Management of the Australian Public Service’s Workforce Response to COVID-19 found that whole of government crisis management documents did not include information on managing the APS workforce in response to a pandemic, and there would be value in whole-of-government crisis management frameworks, plans and arrangements being updated to include consideration of APS-wide operational management matters, such as roles and responsibilities for identifying critical functions, mobilising the APS workforce and issuing-APS wide directions.70

2.89 The 2023 AGCMF Review Report refers to feedback from agencies that ‘the current Australian Public Service Commission surge reserve, whilst used during the Covid-19 response, often did not provide officers that were appropriately trained or experienced in the specifics of crisis management’. While the APS surge reserve is intended to provide staff with ‘generalist’ skills, the 2023 AGCMF Review Report acknowledges the capability gap in relation to crisis management skills and includes a recommendation to improve cross-government crisis management capability, capacity and surge workforce.71 This includes the development of a standard crisis management training package to be developed by NEMA to support a surge crisis workforce across the APS.

Assets

Centres for national resilience

2.90 Centres for National Resilience are purpose-built quarantine facilities in Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth constructed as part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Australian Government funded construction of the centres and state governments were responsible for the operation and management of the facilities for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Centres for National Resilience were expected to provide Australia with a new resilience capability following their use during the COVID-19 pandemic.72

2.91 NEMA considers that the Centres for National Resilience may provide capacity to support COMDISPLAN73 or AUSRECEPLAN.74 For COMDISPLAN the Centres for National Resilience may provide temporary accommodation for people displaced due to natural disasters or emergency service personnel. For AUSRECEPLAN the Centres for National Resilience may provide temporary accommodation and quarantine for returning citizens and permanent residents.

2.92 The Department of Finance and NEMA commenced drafting a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in March 2024, to establish a framework that allows for the potential use of the centres for national resilience for emergency accommodation as well as general storage and emergency management stockpile. As at July 2024, this MOU has not been finalised.

National Emergency Management Stockpile