Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Finance’s (Finance) and selected entities’ implementation of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework (the framework). The audit continues the ANAO’s coverage of the framework, to provide Parliament with: information on its development; campaign expenditure over time; and assurance as to whether entities have effectively implemented the framework and complied with the applicable requirements of the Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities (the Guidelines).

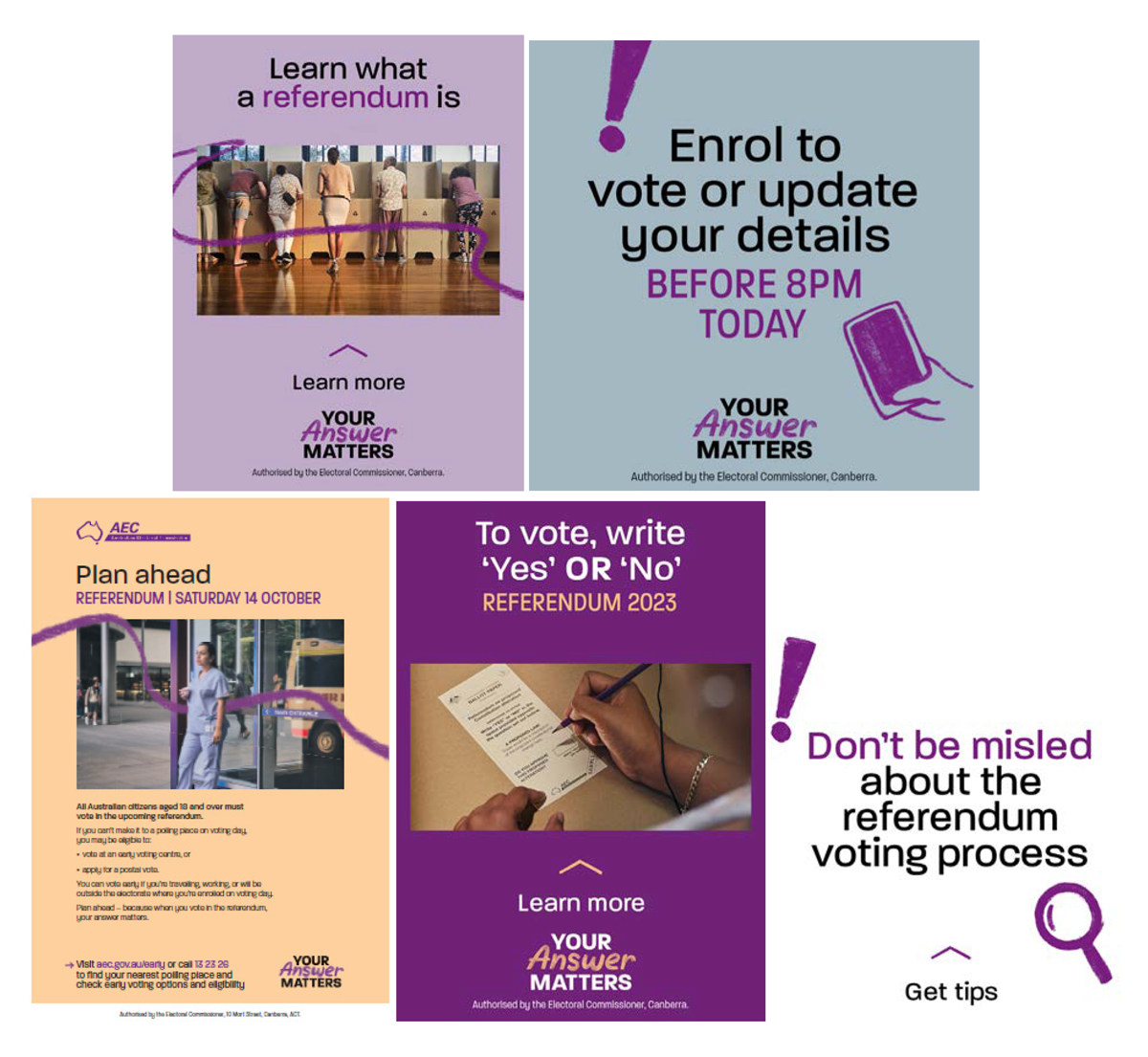

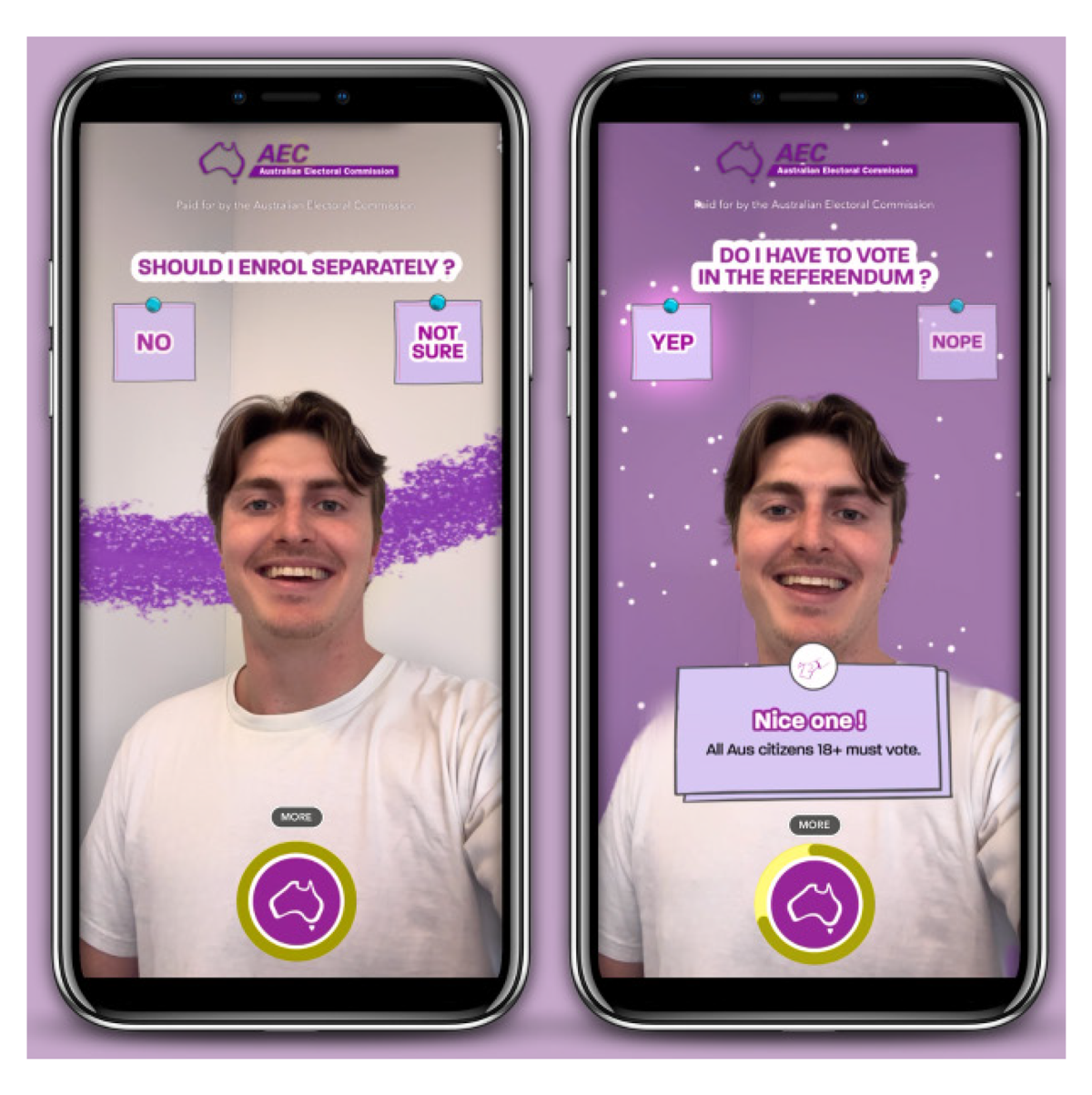

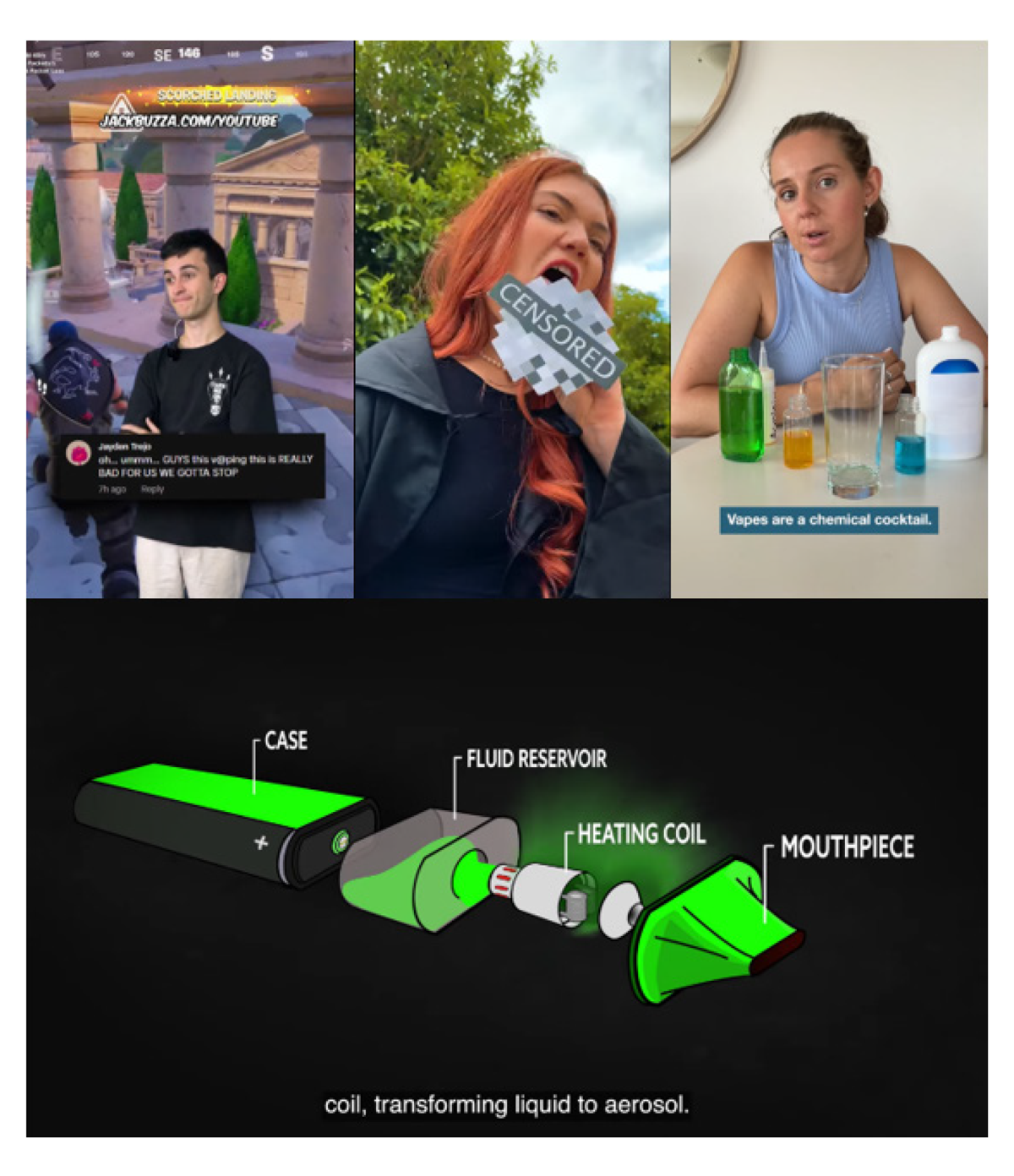

- The ANAO reviewed the Attorney-General’s Department’s (AGD) One Talk at a Time campaign; the Australian Electoral Commission’s (AEC) Your Answer Matters campaign and the Department of Health and Aged Care’s (Health) Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign.

Key facts

- The Guidelines were reviewed in 2022.

- The AEC has an exemption from most elements of the framework. This was most recently approved by the Minister for Finance in October 2022.

What did we find?

- Finance is effective in its whole-of-government administration of the framework.

- AGD and Health were largely compliant with the framework.

- The AEC has largely complied with its internal requirements and the intent of the framework.

What did we recommend?

- There were two recommendations to Finance aimed at development of policy and guidance to manage emerging risks including brand safety relating to the use of artificial intelligence and emerging technologies in advertising and improving procurement practices. There was one recommendation to the AEC aimed at improving its internal arrangements for campaign development and approval.

- Finance and the AEC agreed to the recommendations.

$57.6 m

was the value of the campaigns examined in this audit (GST exclusive).

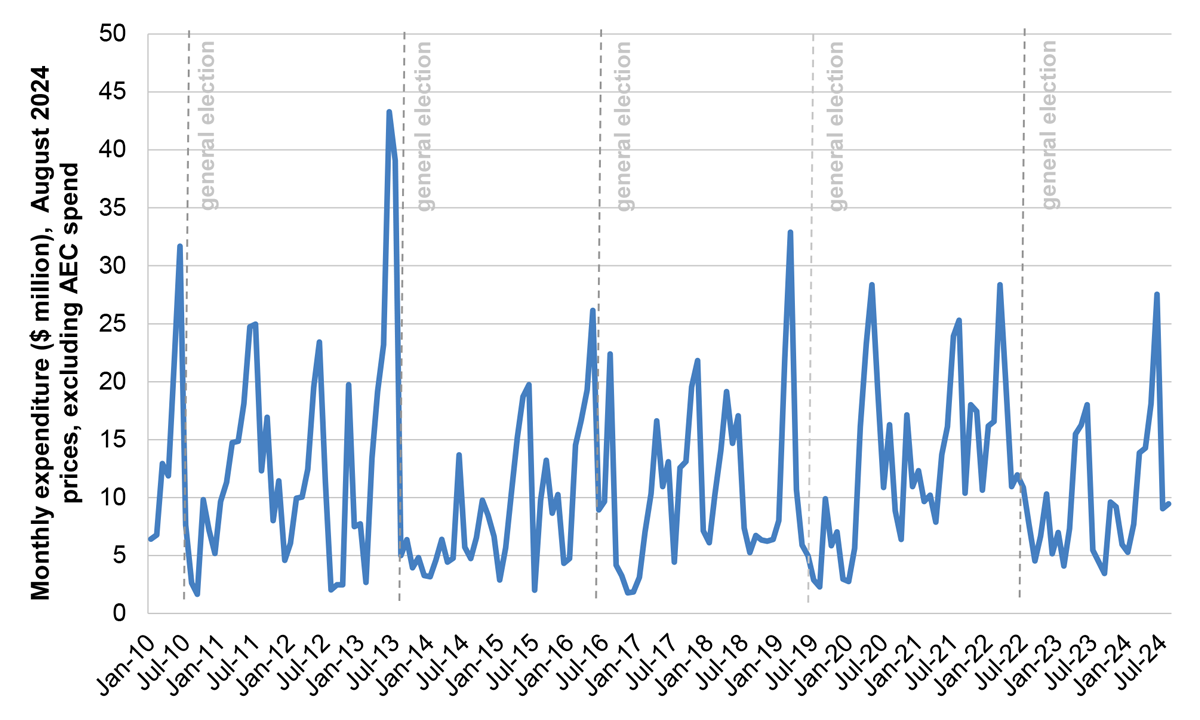

$769.1 m

was the expenditure on Australian Government advertising between July 2021 and June 2024.

1

campaign was exempted from the Guidelines between November 2021 and November 2024 (in addition to the AEC’s general exemption).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework (the framework) applies to non-corporate Commonwealth entities under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).1 The overarching aim of the framework, introduced in 2008, is to provide the Parliament and the community with confidence that public funds are used to meet the genuine information needs of the community.2

2. The government periodically issues guidance for entities undertaking information and advertising campaigns. The most recent version of the Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities (the Guidelines) was released in December 2022 (2022 Guidelines)3, replacing the October 2020 Guidelines (2020 Guidelines). The Guidelines are administered by the Department of Finance (Finance) and state that they:

operate on the underpinning premise that:

- members of the public have equal rights to access comprehensive information about government policies, programs and services which affect their entitlements, rights and obligations; and

- governments may legitimately use public funds to explain government policies, programs or services, to inform members of the public of their obligations, rights and entitlements, to encourage informed consideration of issues or to change behaviour.4

3. The Guidelines apply to all information and advertising campaigns5 undertaken in Australia by non-corporate Commonwealth entities.6 Entities subject to them:

must be able to demonstrate compliance with the five overarching principles when planning, developing and implementing publicly-funded information and advertising campaigns. The principles require that campaigns are:

- relevant to government responsibilities

- presented in an objective, fair and accessible manner

- objective and not directed at promoting party political interests

- justified and undertaken in an efficient, effective and relevant manner, and

- compliant with legal requirements and procurement policies and procedures7

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. This audit is part of an ongoing program of performance audits on Australian Government advertising. The rationale for undertaking this audit is to provide the Parliament with information on key developments in the framework since the period covered by the 2022 ANAO audit8, when the ANAO last reported on its operation.

5. The audit provides independent assurance on whole-of-government administration of the framework by the Department of Finance and selected entities’ compliance with the Guidelines and the wider framework requirements.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Finance’s and selected entities’ implementation of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework.

7. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Does the Department of Finance effectively administer the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework?

- Were selected campaigns compliant with the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework?

8. The audit examined developments in the administration of the framework from November 2021 to November 2024. Three campaigns were selected for review:

- One Talk at a Time campaign, conducted from October 2023 to April 2025, administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD)9;

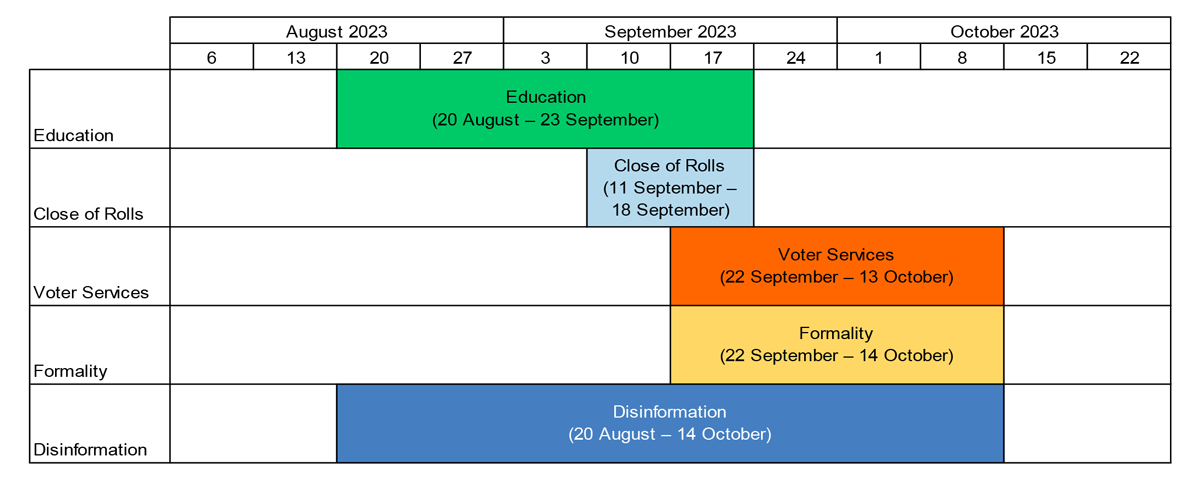

- Your Answer Matters campaign, conducted from August to October 2023, administered by Australian Electoral Commission (AEC)10; and

- Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign, conducted from February to June 2024, administered by the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health).11

Conclusion

9. Finance has been effective at administering the framework. AGD and Health were largely compliant with the framework. The AEC largely complied with its internal requirements and the intent of the framework.

10. Finance has supported entities undertaking campaigns and has arrangements in place to manage brand safety risks relating to advertising on social media platforms. There are emerging gaps relating to the identification and management of risks, including to brand safety, associated with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and emerging technologies in government advertising campaigns, and the changing nature of campaign activities, such as the use of media partnerships and influencers to reach target audiences in government campaigns. Finance extended the whole-of-government Master Media Agency contract after all extension options had been exercised. Finance has met its reporting requirements for expenditure on advertising campaigns.

11. AGD’s One Talk at a Time campaign largely complied with the review, certification and publication requirements of the framework. AGD complied with the requirements of Principles 1 to 3 and largely complied with Principles 4 and 5 of the 2020 Guidelines. Campaign effectiveness was reduced by the delayed implementation of pre-launch public relations activities. Not all campaign materials contained appropriate attribution of Australian Government involvement and two procurements were not accurately reported on AusTender. The advertising component of the campaign was evaluated, with the evaluation report finding that the campaign ‘achieved’ one objective and ‘partially achieved’ two objectives. At November 2024, an evaluation addressing other aspects of the campaign had not been undertaken as public relations activities were still underway.

12. Since 2009, the AEC has had an exemption from most aspects of the framework and has committed to complying with the intent of the 2022 Guidelines. Documentation capturing the AEC’s requirements for campaign development and certification, known as ‘AEC communication campaigns: Guidelines and mandatory checklist’ (AEC Guidelines), was in draft and there was no documented approval. The AEC’s Your Answer Matters campaign largely complied with the review and publication requirements. Publication requirements were met, although AEC did not publish campaign research reports, did not document consideration of whether doing so was appropriate and there were inaccuracies in the reporting of campaign expenditure figures in the AEC annual report and subsequent reporting to the Department of Finance. The AEC complied with Principles 1 to 4 of the 2022 Guidelines and largely complied with Principle 5. Legal advice addressing all legal requirements of Principle 5 was finalised after the campaign had commenced. The AEC’s requirements for attribution of AEC contribution to media partnerships and public relations materials was not documented. The AEC evaluated the campaign with the evaluation report finding that of the total 23 objectives, 16 were ‘met’, six were ‘partly met’ and one was ‘not met’.

13. Health largely complied with the review, certification and publication requirements of the framework. Health complied with the requirements of Principles 1, 3 and 4 of the 2022 Guidelines and largely complied with Principles 2 and 5 of the 2022 Guidelines. Health did not document how campaign imagery reflected a diverse range of Australians. Not all campaign materials contained attribution of Australian Government involvement. Health evaluated the Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign to determine its effectiveness. The evaluation report consolidated the campaign’s original seven objectives into four objectives. The evaluation found that two objectives were achieved and two objectives were partially achieved.

Supporting findings

Administration of the Australian Government campaign advertising framework — Finance

14. Finance maintains a suite of guidance documents on a clearly signposted section of its website and manages a campaign community through its GovTEAMS site to support entities undertaking campaigns throughout the campaign advertising development process. Finance facilitates the Independent Communications Committee’s review process and provides advice to government regarding requests for exemption from the Guidelines. Finance has established arrangements to receive feedback from suppliers and entities through evaluations undertaken at the end of campaigns, with annual reviews providing a whole-of-government view across all campaigns. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.21)

15. Finance has arrangements to manage risks relating to brand safety on social media platforms. Given the changing nature of campaign activities there are emerging gaps in relation to the use of media partnerships, public relations and influencers. Gaps relate to the appropriateness of the level of information relating to these activities provided for final government review and the attribution of campaign materials. There is an absence of guidance around emerging risks, including to brand safety, relating to the potential use of AI and emerging technologies in advertising and information campaigns. Finance extended the whole-of-government Master Media Agency contract after all extension options had been exercised. ( See paragraphs 2.22 to 2.80)

16. Finance has reported to the Parliament on annual media placement and associated campaign development expenditure by non-corporate Commonwealth entities, for campaigns with expenditure greater than $250,000 (exclusive of GST), in its annual report on Campaign Advertising by Australian Government Departments and Entities. Details of expenditure relating to Finance’s contracts with the Master Media Agency and Independent Communications Committee (ICC) members have not been included in these reports. Finance guidance does not address the publication of advertising campaign research reports which, under the 2022 Guidelines, must be published on entity websites ‘where it is appropriate to do so’ for campaigns with an expenditure of $250,000 (exclusive of GST) or more. (See paragraphs 2.81 to 2.93)

One Talk at a Time campaign

17. AGD’s One Talk at a Time campaign received government approvals in accordance with the framework requirements applying at the time it was considered.

18. The Secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department (Secretary of AGD), as the accountable authority, certified that the campaign complied with all five principles of the 2020 Guidelines and the certification was published on AGD’s website, as required. The Secretary’s certification was informed by a third-party certification from the ICC, as required by the 2020 Guidelines, and AGD advice on compliance. AGD provided the Attorney-General with the signed Secretary’s certification.

19. AGD complied with publication requirements, except for those relating to the statement in its 2023–24 annual report. AGD published its developmental research report on the One Talk at a Time campaign website. (See paragraphs 3.14 to 3.24)

20. AGD complied with Principles 1 to 3 of the 2020 Guidelines and largely complied with Principles 4 and 5.

21. For Principle 4, campaign effectiveness was reduced by the delayed execution of pre-launch public relations activities. For Principle 5, 17 of the 21 media partnership materials had appropriate attribution statements noting Australian Government involvement and two of the campaign procurements were not accurately reported on AusTender. (See paragraphs 3.25 to 3.62)

22. Advertising components of the One Talk at a Time campaign were evaluated to determine their effectiveness. This evaluation identified that the advertising component of the campaign ‘achieved’ one objective and ‘partially achieved’ two objectives. At November 2024, the planned integrated evaluation of all campaign components, including media partnerships and public relations, had not been completed.

23. The performance of the campaign was monitored against media metrics, including key performance indicators (KPIs). AGD received in-flight monitoring of the campaign’s performance, including a mid-campaign report and a final media performance report. (See paragraphs 3.63 to 3.71)

Your Answer Matters campaign

24. Due to its exemption, the AEC was not subject to review by the ICC or government review and approval processes. The AEC had documented requirements for campaign development and certification in the form of the AEC Guidelines. The version of the AEC Guidelines used for the Your Answer Matters campaign was in draft and there was no documented approval.

25. Under the AEC Guidelines, the AEC has committed to complying with the intent of the 2022 Guidelines. The AEC Guidelines did not establish a requirement for legal advice confirming compliance with Principle 5 of the 2022 Guidelines to be provided to the Electoral Commissioner prior to campaign certification.

26. The AEC followed an internal review process that involved the Electoral Commissioner providing approval for key campaign development milestones. The Electoral Commissioner signed two certifications for the campaign, which were both published on the AEC’s website in accordance with the AEC Guidelines. The AEC did not publish campaign research reports on its website and did not document consideration of whether publication of the research reports was appropriate and there were inaccuracies in the reporting of campaign expenditure figures in the AEC annual report and subsequent reporting to the Department of Finance. (See paragraphs 4.18 to 4.40)

27. The AEC complied with the intent of Principles 1 to 4 of the 2022 Guidelines and largely complied with Principle 5. Legal advice addressing all legal requirements of Principle 5 was finalised after the campaign had commenced. The AEC had not documented attribution requirements for media partnerships or public relations materials. Details of one procurement were not accurately reported on AusTender. (See paragraphs 4.41 to 4.78)

28. The Your Answer Matters campaign was evaluated to determine its effectiveness. Of the 23 objectives across the five phases of the campaign, 16 were assessed as ‘met’, six were assessed as ‘partly met’ and one was assessed as ‘not met’.

29. The performance of the campaign was monitored against media metrics, including KPIs. The AEC received weekly reporting on the performance of media channels. (See paragraphs 4.79 to 4.85)

Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign

30. Health’s Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign received government approvals in accordance with the framework requirements applying at the time it was considered.

31. The accountable authority, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Aged Care (Secretary of Health and Aged Care), certified that the campaign complied with the five ‘overarching principles’ of the 2022 Guidelines and the certification was published on Health’s website, as required. The Secretary’s certification was informed by a third-party review from the ICC, as required by the 2022 Guidelines, and Health advice on compliance. Health provided the Secretary’s certification to the Minister for Health and Aged Care on 3 May 2024, approximately three months after the campaign commenced, which was not compliant with the 2022 Guidelines.

32. Health complied with publication requirements. Health published the campaign developmental research report on its website. (See paragraphs 5.12 to 5.23)

33. Health complied with Principles 1, 3 and 4 and largely complied with Principles 2 and 5 of the 2022 Guidelines.

34. For Principle 2, Health did not document how campaign imagery reflected a diverse range of Australians. Legal advice provided in support of compliance with Principle 5 addressed the media partnerships component of the campaign but not the influencer component. Seventeen of the 28 media partnership materials did not contain attribution of Australian Government contribution to the materials. Health’s audit trail of procurement decision-making was mostly complete. (See paragraphs 5.24 to 5.74)

35. Health evaluated the Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign to determine its effectiveness. The evaluation report consolidated the campaign’s original seven objectives into four objectives. The evaluation found that two objectives were achieved and two objectives were partially achieved.

36. Campaign performance was monitored against media metrics, including KPIs. Health received in-flight monitoring of the campaign’s performance, including a report on the performance of influencers, a mid-campaign report and a final media performance report. (See paragraphs 5.75 to 5.82)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.55

The Department of Finance develop supporting policy and guidance to identify and manage emerging risks, including to brand safety, relating to the use of artificial intelligence and emerging technologies in government advertising campaigns.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.72

When planning future procurements for Master Media Agency services for Australian Government advertising, the Department of Finance provide sufficient time to enable the procurement process to be completed prior to exhausting all extension options available under the existing contract.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.21

The Australian Electoral Commission update the ‘AEC communications campaigns: Guidelines and mandatory checklist’ (AEC Guidelines) to include:

- a requirement for legal advice confirming compliance with Principle 5 of the Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising campaigns to be provided to the Electoral Commissioner prior to campaign certification; and

- details of version control and approval of the AEC Guidelines.

Australian Electoral Commission response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

37. The proposed audit report was provided to Finance, AGD, AEC and Health, with an extract being provided to the Independent Communications Committee. The entities’ summary responses are provided below, and their full responses are included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Department of Finance

The Department of Finance welcomes the conclusion that the Department has been effective in the whole-of-government administration of the Government’s campaign advertising framework, including Finance’s role in supporting entities, providing secretariat support to the Independent Communications Committee, meeting its requirements for reporting on campaign advertising expenditure by non-corporate Commonwealth entities, and having arrangements in place to manage brand safety risks relating to advertising on social media platforms.

Finance agrees the two recommendations directed to the Department and will take appropriate action to address the matters raised.

Attorney-General’s Department

The Attorney-General’s Department (the department) welcomes the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) report on Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024, in particular the findings for the department’s “One Talk at a Time” campaign.

The department agrees with the recommendations and acknowledges the opportunity for administrative improvements in relation to record keeping, attribution of Australian Government involvement in campaign activity and reporting on AusTender.

The department acknowledges the ANAO’s finding that the campaign successfully achieved one objective and “partially achieved” two others. However, the full evaluation of the campaign’s effectiveness is yet to be completed and is expected to conclude in 2025, following the completion of below-the-line activities.

The department is committed to continuous improvement and will use the ANAO’s findings and recommendations to further refine our campaign processes and guidance.

Australian Electoral Commission

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) welcomes the ANAO report.

The AEC notes it is exempt from the Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities, including exemption from review and approval of AEC campaigns by government. This is due to the need for campaigns on electoral events to be independent of government. Instead, the AEC has its own Guidelines and certification process.

The AEC agrees with the one recommendation relating to improvement of our own Guidelines; and acknowledges the areas for improvement. We have reviewed and are addressing the highlighted administrative processes, noting they do not compromise compliance with our Guidelines.

The AEC remains committed to continuous improvement, and to our ongoing conformance with the intent of the Australian Government Guidelines.

Department of Health and Aged Care

The Department of Health and Aged Care (the department) acknowledges the findings in this report. The department is committed to responding to the opportunities for improvement identified by the Australian National Audit Office.

It is pleasing to note the finding the department was largely compliant with the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework, including the review, certification and publication requirements.

The department also welcomes the finding the department complied with the requirements of Principles 1, 3 and 4 of the 2022 Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns and largely complied with Principles 2 and 5 of the Guidelines. The department also appreciates the report’s recognition the department established arrangements and processes to meet the objectivity requirements of Principle 2 of the Guidelines and mitigate the risks associated with engaging with influencers.

The audit identified two opportunities to improve the documentation of how a diverse range of Australians are reflected in campaign imagery and ensuring campaign materials contain appropriate attribution of the department’s involvement. To address these findings, the department will continue to strengthen its administrative processes when implementing government advertising campaigns.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

38. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Stewardship by framework policy owners

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

Australian Government campaign advertising framework

1.1 The Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework (the framework) applies to non-corporate Commonwealth entities under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).12 The overarching aim of the framework, introduced in 2008, is to provide the Parliament and the community with confidence that public funds are used to meet the genuine information needs of the community.13

1.2 The government periodically issues guidance for entities undertaking information and advertising campaigns. The most recent version of the Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities (the Guidelines) was released in December 2022 (2022 Guidelines)14, replacing the October 2020 Guidelines (2020 Guidelines). The Guidelines are administered by the Department of Finance (Finance) and state that they:

operate on the underpinning premise that:

- members of the public have equal rights to access comprehensive information about government policies, programs and services which affect their entitlements, rights and obligations; and

- governments may legitimately use public funds to explain government policies, programs or services, to inform members of the public of their obligations, rights and entitlements, to encourage informed consideration of issues or to change behaviour.15

1.3 The Guidelines apply to all information and advertising campaigns16 undertaken in Australia by non-corporate Commonwealth entities.17 Entities subject to them:

must be able to demonstrate compliance with the five overarching principles when planning, developing and implementing publicly-funded information and advertising campaigns. The principles require that campaigns are:

- relevant to government responsibilities

- presented in an objective, fair and accessible manner

- objective and not directed at promoting party political interests

- justified and undertaken in an efficient, effective and relevant manner, and

- compliant with legal requirements and procurement policies and procedures18

1.4 The framework is intended to provide transparency in the development and implementation of government advertising and information campaigns, value for money in procurement, and the proper use of public resources. The key components of the framework are described in Box 1. As part of the framework, Finance has established mandatory procurement and evaluation mechanisms for entities conducting campaigns, which are described in Box 2. When reading the framework guidance, as reflected in Box 1, it is important to note the application of requirements relating to information campaigns as compared to advertising campaigns, as they may differ.

|

Box 1: Components of the framework |

|

Responsibility for administration of the framework The Government Communications Subcommittee (GCS) oversees and reviews Australian Government advertising campaigns involving paid media placement with a total campaign budget of more than $500,000 (exclusive of GST). The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) issued a circular in 2022 for all entities preparing items for consideration by the GCS. Initiation of proposed advertising campaigns valued above $250,000 (exclusive of GST) requires authority from the Minister for Finance. The Minister for Finance can exempt campaigns from complying with the Guidelines. Exemptions are discussed in paragraphs 2.10 to 2.12 of this report. Finance provides policy advice, whole-of-government coordination, and assistance to entities conducting advertising activities. Finance publishes the Guidelines, which set out the five overarching principles that provide the context in which Australian Government campaigns are to be conducted. Finance reports to the Parliament annually on campaign advertising by Australian Government departments and entities with expenditure greater than $250,000 (exclusive of GST).a For each campaign, these reports provide a short description and breakdown of expenditure by medium. They also provide data on media placement, market research and advertising production costs. Other Finance functions related to government advertising campaigns include:

Responsibilities of ministers and entities conducting government campaigns Ministers may authorise an advertising campaign’s launch. Entities subject to the Guidelines must be able to demonstrate compliance with the five overarching principles when undertaking campaigns. An entity’s accountable authority is required to:

There is also an expectation that the accountable authority will provide information to Finance for the purpose of Finance preparing reports to the Parliament that detail expenditure on all advertising campaigns with expenditure in excess of $250,000 (exclusive of GST), commissioned by PGPA Act entities. Third-party review role The ICC consists of three members appointed by the Minister for Finance. Since early 2015b the ICC’s role in the framework has been to:

The ICC’s compliance advice is published on Finance’s website.d The Guidelines provide that information campaigns are not subject to ICC review, or certification by the accountable authority, but must comply with the Guidelines. Discussion of the ICC’s terms of reference and the level of assurance provided to accountable authorities by the ICC is discussed in paragraph 2.6. Government review and approval of campaigns The GCS approves the final creative materials and media plans for campaigns. Since November 2022, the GCS has overseen and reviewed campaigns involving paid media placement with a total campaign budget of more than $500,000 (exclusive of GST). The GCS receives evaluation summary reports from Finance. |

Note a: These reports are published at https://www.finance.gov.au/publications/reports/advertising.

Note b: As outlined in paragraph 1.6, the ICC was suspended under the Interim Guidelines that were in place between July 2022 and December 2022.

Note c: The Guidelines state that ‘Entities will be responsible for providing a report to their Accountable Authority on campaign compliance with Principle 5 of the Guidelines.’

Note d: This advice is published at https://www.finance.gov.au/publications/compliance-advice.

Source: ANAO analysis of Finance information.

|

Box 2: Procurement and evaluation arrangements under the framework |

|

Central Advertising System The Central Advertising System (CAS) is the whole-of-government procurement arrangement mandated for all campaign and non-campaign advertising undertaken by non-corporate Commonwealth entities.a The arrangement was established to consolidate expenditure and buying power to secure optimal media rates for the placement of government advertising. Following an open tender process, Finance appointed Universal McCann (UM) as the sole supplier Master Media Agency (MMA) for the period 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2021. The contract end date was extended in April 2021, to 30 June 2024. In May 2024 the contract was further extended to 30 September 2024. At 22 August 2024, the value of the MMA contract, as reported on AusTender, was approximately $77.3 million. The MMA utilises UM Central, an online management system, which entities use to brief UM on their advertising requirements. Government Communications Campaign Panel The Government Communications Campaign Panel (GCCP) is the mandated whole-of-government panel arrangement, established by Finance in 2021. The GCCP lists 20 suppliers, each of which has a specific professional and content area aligned to the six pre-determined government priorities in which it can operate. Use of the GCCP is mandatory for all non-corporate Commonwealth entities with the exception of the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC)b and the Defence Force Recruiting campaigns.c Whole-of-government campaign evaluation framework Effective 1 July 2018, following a limited tender process, Finance established a single provider (Hall & Partners) to provide standardised benchmarking, tracking and evaluation research services for all campaigns with total budgets above $500,000 (exclusive of GST) per financial year. Finance entered into a new arrangement with Hall & Partners in July 2022. In June 2024 this arrangement was extended to 30 June 2025. The use of the whole-of-government campaign evaluation framework is mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities, with the exception of the AEC.b In October 2024, Finance estimated Hall & Partners provided campaign evaluation services to the value of approximately $7.9 million (inclusive of GST) between 1 July 2022 and 30 September 2024. |

Note a: Corporate Commonwealth entities, Commonwealth companies under the PGPA Act and certain other approved organisations provided with Commonwealth funding for advertising or communications purposes may place their advertising through the CAS.

Note b: The AEC’s exemption is discussed in paragraphs 4.2 to 4.4.

Note c: The Defence Force Recruiting exemption from using the GCCP commenced in 2021 and is not in scope of this audit. As discussed in paragraph 1.14, Defence Force Recruiting advertising was assessed in Auditor-General Report No. 45 2023–24 Defence’s Management of Recruitment Advertising Campaigns.

Source: ANAO analysis of Finance information.

Framework developments

1.5 The ANAO last reviewed the framework in 2022.19 Developments since then have included revisions (see paragraph 1.7) to the Guidelines and implementation of the ‘village model’ of campaign development.

Revised Guidelines

1.6 Interim Guidelines were in effect between July and December 2022.20 They suspended the operation of the ICC21 and provided for the Minister for Finance to approve campaigns to proceed to market. This did not affect the three campaigns assessed in this audit.

1.7 The Guidelines have been revised periodically since their introduction in 2008. Changes between the 2020 Guidelines and the 2022 Guidelines were:

- clarification that all dollar figures are to be read as exclusive of GST;

- the Minister for Finance assuming responsibilities previously undertaken by the Special Minister of State; and

- that specific consideration is given to communicating with people with disability and that imagery used in campaigns appropriately reflects people with disability.22

Governance arrangements

1.8 In 2022, PM&C issued a circular to all entities preparing items for consideration by the GCS. The circular captures oversight and review arrangements established by the GCS.23

Implementation of the ‘village model’

1.9 The 2022 ANAO audit reported on the establishment of a ‘new communications framework and strategic themes for government campaigns’.24 Following reviews undertaken in 2019 into the effectiveness of the approach to developing government campaigns, changes were implemented under which campaigns are aligned to one of six strategic themes, and campaigns within each theme are developed with the support of a ‘village’ of suppliers.25 The village model is discussed further in paragraphs 2.13 to 2.18.

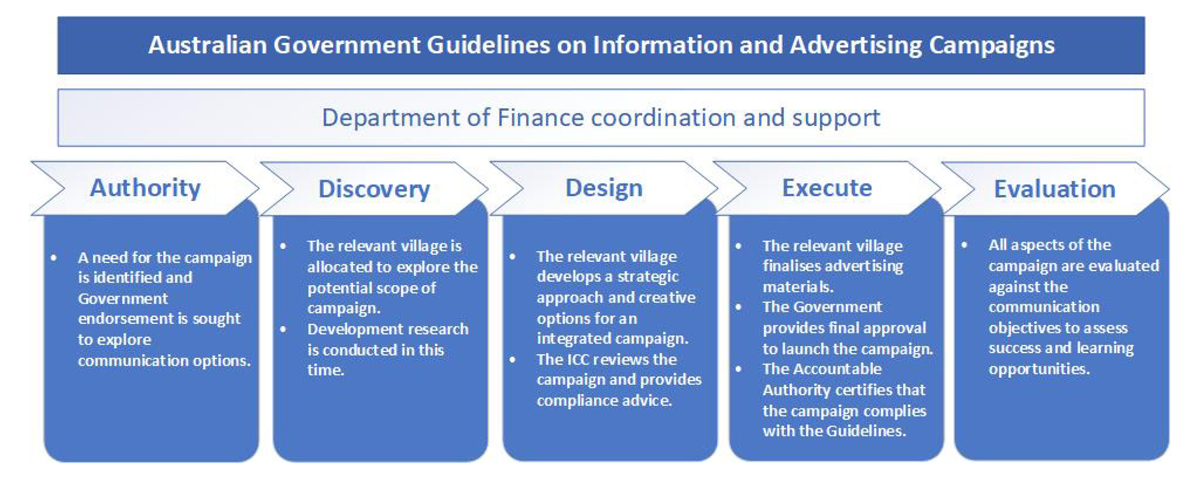

1.10 The campaign development process is outlined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Campaign development process

Source: Finance documentation.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.11 This audit is part of an ongoing program of performance audits on Australian Government advertising. The rationale for undertaking this audit is to provide the Parliament with information on key developments in the framework since the period covered by the 2022 ANAO audit, when the ANAO last reported on its operation.

1.12 The audit provides independent assurance on whole-of-government administration of the framework by the Department of Finance and selected entities’ compliance with the Guidelines and the wider framework requirements.

Previous audits

1.13 The administration of Australian Government advertising has been examined in previous ANAO performance audit reports, which also reviewed the development of the framework since its introduction in 2008. The 2019 audit report included 10 recommendations, five of which were directed to Finance or the Australian Government and five directed to the three other entities included in the audit.26 The 2022 audit contained seven recommendations, one directed to Finance and six directed to the other entities included in the audit.27 Finance’s implementation of the recommendation addressed to it in the 2022 audit is discussed in paragraphs 2.27 to 2.28.28 The other entities assessed in this audit were not included in the 2022 audit.

1.14 In 2024, an audit of Defence’s Management of Recruiting Advertising Campaigns assessed whether three Defence Force Recruitment campaigns complied with the framework.29 The audit found that ‘The Department of Defence’s management of the three selected advertising campaigns for Australian Defence Force recruitment was largely effective.’30 The report contained three recommendations aimed at improving the transparency of Defence’s public reporting on individual advertising campaigns and complying with the framework with respect to end of campaign evaluations.31

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.15 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Finance’s and selected entities’ implementation of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework.

1.16 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Does the Department of Finance effectively administer the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework?

- Were selected campaigns compliant with the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework?

1.17 The audit examined developments in the administration of the framework from November 2021 to November 2024. Three campaigns were selected for review:

- One Talk at a Time campaign, conducted from October 2023 to April 2025, administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD)32;

- Your Answer Matters campaign, conducted from August to October 2023, administered by Australian Electoral Commission (AEC)33; and

- Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign, conducted from February to June 2024, administered by the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health).34

The Australian Electoral Commission exemption

1.18 Since 2009, the AEC has an exemption from most elements of the framework.35 The AEC has committed to adhering to the intent of the Guidelines and places media through the MMA. The AEC’s exemption is discussed in paragraphs 4.2 to 4.4. For the purposes of this audit, the AEC was assessed for compliance against its internal review and certification arrangements, and for compliance with the intent of the Guidelines.36

Audit methodology

1.19 The audit methodology included:

- reviewing Finance’s advice to government, advice to entities and public reporting produced by Finance;

- reviewing meeting minutes and decisions of the ICC, and meeting with committee members;

- reviewing entity documentation relating to campaign design, administration, certification and evaluation to determine compliance; and

- meetings with key personnel at each designated entity.

1.20 Australian Government entities largely give the ANAO electronic access to records by consent, in a form useful for audit purposes. For the purposes of this audit, the Department of Health and Aged Care advised the ANAO that it would not voluntarily provide certain information requested by the ANAO due to concerns about its obligations under the Privacy Act 1988, secrecy provisions in Health and Aged Care portfolio legislation, confidentiality provisions in contracts and the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013. Health advised that this type of information largely was not segregated in Health’s record-keeping systems and Health could not be certain, in providing documents through electronic means, that documents containing this type of information were excluded. To provide comfort to the Secretary of Health and Aged Care regarding its obligations under portfolio legislation, on 30 April 2024 the acting Auditor-General issued the Secretary of Health and Aged Care with a notice directing the Secretary of Health and Aged Care to provide information and produce documents pursuant to section 32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997. Under this notice, Health agreed to provide the information and documents requested through electronic means.

1.21 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $773,700.

1.22 The team members for this audit were James Sheeran, Grace Guilfoyle, Stephanie Gill, Alexandra McFadyen, Alannah Perry and Susan Drennan.

2. Administration of the Australian Government campaign advertising framework — Finance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Finance (Finance) has effectively administered the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework (the framework).

Conclusion

Finance has been effective at administering the framework. Finance has supported entities undertaking campaigns and has arrangements in place to manage brand safety risks relating to advertising on social media platforms. There are emerging gaps relating to the identification and management of risks, including to brand safety, associated with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and emerging technologies in government advertising campaigns, and the changing nature of campaign activities, such as the use of media partnerships and influencers to reach target audiences in government campaigns. Finance extended the whole-of-government Master Media Agency contract after all extension options had been exercised. Finance has met its reporting requirements for expenditure on advertising campaigns.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at the establishment of policy and guidance to identify and manage risks relating to the use of AI in government advertising campaigns and improving procurement practices.

The ANAO identified three opportunities for improvement. These relate to: reviewing the appropriateness of the level of information provided as part of government review of advertising campaigns; developing guidance on the attribution of media partnerships, public relations and influencer materials; and developing guidance relating to publication of campaign-related research.

2.1 The framework is intended to provide transparency in the development and implementation of government advertising and information campaigns, value for money in procurement, and the proper use of public resources.

2.2 Finance provides whole-of-government policy advice, coordination, and assistance to entities conducting campaign and non-campaign advertising activities.37 Finance supports entities implementing the framework by providing general guidance, support for individual campaigns and managing whole-of-government procurement arrangements. Finance is also responsible for responding to emerging risks and issues relating to Australian Government advertising and supporting transparency through public reporting.

Does Finance effectively support entities in their implementation of the framework?

Finance maintains a suite of guidance documents on a clearly signposted section of its website and manages a campaign community through its GovTEAMS site to support entities undertaking campaigns throughout the campaign advertising development process. Finance facilitates the Independent Communications Committee’s review process and provides advice to government regarding requests for exemption from the Guidelines. Finance has established arrangements to receive feedback from suppliers and entities through evaluations undertaken at the end of campaigns, with annual reviews providing a whole-of-government view across all campaigns.

Guidance and resources for entities

2.3 Finance publishes information relating to the framework on its website, which is signposted under four categories: Government Advertising Overview; Policies and Guidance; Publications and Compliance Advice; and Guidance and Information.38 Advice to entities is further facilitated on the ‘Campaign Community’ GovTEAMS site, which is administered by Finance39, and by responding to entity enquiries via email and telephone.40 Finance does not collect data on the number of emails and phone calls it receives from entities seeking advice.

2.4 At September 2024, there were 201 members from 28 entities with access to the GovTEAMS site, which provides entities access to:

- high level information on campaign governance processes;

- access to seminars and learning materials;

- a resource library for different campaign stages;

- a ‘news’ function through which Finance provides updates to entities on procurement arrangements, newly commenced campaigns and updates to guidance and other resources available on the GovTEAMS site; and

- contact details for officers in Finance providing support to entity campaign managers and campaign suppliers.

2.5 Between July 2022 and November 2024, Finance delivered 11 seminars through GovTEAMS to support entities in their advertising activities. Topics covered included: examples of campaign development under the village model; campaign evaluation insights; inclusivity in campaigns; media mixes; and the evolution of television and video-based advertising.

Independent Communications Committee

2.6 The Independent Communications Committee (ICC) undertakes a third-party review of government advertising campaigns and provides compliance advice to entity accountable authorities.41 The committee’s functions are described in its terms of reference:

- reviewing the evidence and documentation supporting the development of campaigns, particularly in regard to adherence with the Principles 1 to 4 of the Guidelines. The Committee’s consideration of compliance draws upon;

- associated market research or supporting evidence, media strategy and media plan, and any other information or independent expert advice available.

- meeting with representatives from responsible entities developing campaigns to clarify information presented in the documentation (if required);

- providing a report to the Accountable Authority (Chief Executive/Secretary) on compliance with reference to Principles 1 to 4 of the Guidelines42;

- reporting to responsible Ministers on the operation of the Guidelines, as necessary, including any trends and emerging issues; and

- considering and proposing to responsible Ministers any revisions to the Guidelines as necessary in light of experience.

2.7 The ICC has not provided advice to the responsible minister during the period under review.43

2.8 Finance provides secretariat support for the ICC and attends all meetings. A guide for entities has been developed on the ICC process, including an overview of the ICC’s role, meeting arrangements and the level of representation entities should provide at meetings. Templates are also provided to entities to assist with the efficiency of briefing materials and feedback is provided to entities, from the ICC, regarding their processes and expectations.

2.9 The ICC held 34 meetings between 1 November 2021 and 18 September 2024. The minutes documented 65 instances where the ICC determined that campaigns were capable of being compliant with the Guidelines and 13 instances where the ICC advised entities that more work was required before independent advice on the proposed campaign and compliance with the Guidelines could be provided. ICC members advised the ANAO in September 2024 that they had initiated a process change under which minutes of ICC meetings are provided to accountable authorities for transparency purposes.44

Exemptions from the Guidelines

2.10 The 2022 Guidelines provide that the Minister for Finance can exempt a campaign from complying with the Guidelines ‘on the basis of a national emergency, extreme urgency or other compelling reason.’ The 2020 Guidelines had the same provision, except that the Special Minister of State (SMOS) was the decision-maker.45 Both the 2020 and 2022 versions of the Guidelines provided that ‘Where an exemption is approved, the Independent Communications Committee will be informed of the exemption, and the decision will be formally recorded and reported to the Parliament as soon as is practicable.’ Finance facilitates consideration of exemption requests by advising entities on the required process, providing briefings to government on requests received and fulfilling reporting obligations.

2.11 During the audit period, one campaign was exempted. This was the Department of Health and Aged Care’s COVID-19 campaign, for which the Minister for Health and Aged Care sought an exemption for the month of January 2022 only. The campaign was to inform the Australian community on: vaccine delivery; changes to COVID-19 testing requirements and eligibility; and the benefits of COVID-safe behaviour. Finance prepared briefing materials for the SMOS and informed the ICC of the exemption, as required under the 2020 Guidelines. The exemption was reported to the Parliament, fulfilling the requirements of paragraph 9 of the 2020 Guidelines.46 The exemption was reported in Finance’s Campaign Advertising by Australian Government Departments and Entities Report 2021–22.

Australian Electoral Commission’s exemption

2.12 The Australian Electoral Commission’s (AEC’s) exemption from aspects of the framework, including the Guidelines, is discussed in paragraphs 4.2 to 4.4. The Electoral Commissioner requested the exemption by writing directly to the Minister for Finance and noted that Finance had been consulted in preparing the exemption request.

Implementation of the ‘village model’

2.13 In March 2021, Finance established the Government Communications Campaign Panel (GCCP) (SON3754402) as a mandatory whole-of-government panel for the engagement of communications suppliers for advertising and information campaigns undertaken by non-corporate Commonwealth entities.47 Since the establishment of the panel, Defence Force Recruiting (DFR) campaigns48 and campaigns undertaken by the AEC have been exempt from using the GCCP.49

2.14 Suppliers on the GCCP are structured under six ‘strategic themes’: security; health and wellbeing; economy; program delivery; building our community; and infrastructure and innovation.50 GCCP suppliers, together with the Master Media Agency (MMA) (Universal McCann (UM)), the whole-of-government evaluations supplier (Hall & Partners), entities undertaking campaigns, and Finance51 form ‘villages’ under each strategic theme. The same combination of suppliers (one from each category) work on all campaigns within the same theme.52 Under the circular issued by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), the Minister for Finance approves the strategic theme and the associated village of suppliers for each campaign.53 Finance advised the ANAO in October 2024 that:

It should be noted that Minister for Finance’s role has evolved over the period of the audit to no longer being responsible for the allocation of proposed campaigns to Government Communications Campaign Panel (GCCP) Villages. This change in role aligns with the update to the Commonwealth Procurement [Rules]–July 2024 (CPRs) that state:

“3.2 Except where required by law, it is the government’s policy position that ministers will not:

- be involved in the conduct of procurement processes; or

- direct officials about the conduct of procurement processes.”

…

The role of allocation of campaigns to GCCP Villages is now undertaken by the Department of Finance.

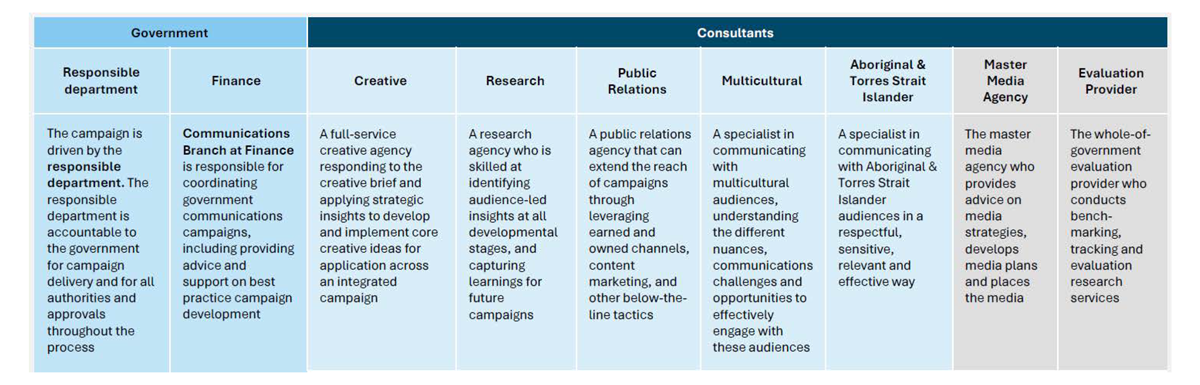

2.15 Finance further advised the ANAO in October 2024 that it ‘has liaised with PM&C to seek an update to the relevant Circular’. Figure 2.1 shows the make-up of each campaign village.54

Figure 2.1: Village model for campaign developmenta

Note a: GCCP suppliers provide the services in columns 3 to 7.

Source: Finance documentation.

2.16 Finance has detailed the campaign development process that occurs under the village model in the Village Implementation Guide (the Guide). The February 2023 version of the Guide states:

This Village format allows teams of consultants to work more closely together, and from an earlier stage, with the responsible department to respond to specific campaign requirements. Developing knowledge and experience on certain campaign themes, and applying those learnings with each new campaign that is initiated.

2.17 The village model facilitates entities undertaking campaigns to work with Finance and their assigned village suppliers from the initiation of a campaign until its completion and evaluation.55 Finance attends campaign development meetings with suppliers, ICC meetings and meetings where campaigns are reviewed by government. Finance’s Communications Advice Branch (CAB) assigns a ‘CAB Campaign Manager’ to each campaign to support the process. The Guide states that the CAB Campaign Manager:

- Provides leadership of campaign development from a whole-of-government perspective

- Assists in the successful operation and collaboration across the Village and seeks to resolve any issues related to process or approach

- Works closely with the responsible department Campaign Manager.

…

- Review of Village efficacy and collaboration on a regular basis

- Provision of operational feedback to Village outside of normal campaign reviews.

2.18 For each step in the campaign development process, the Guide provides information on the outcomes to be achieved and links to resources in the form of guidance and templates (see paragraphs 2.3 to 2.5).

Village model feedback

2.19 Finance has received feedback from suppliers and entities engaged under the village model through evaluations undertaken at the end of each campaign.56 Respondents were asked three questions:

How do you rate the overall advice and support provided by CAB throughout the process, including as an escalation point?

Do you think CAB provides appropriate/useful guidance on best practice implementation of the Village model, to help with campaigns?

Are there areas in which CAB could provide guidance or support that it is not currently providing?

2.20 At September 2024, there had been two ‘annual reviews’ capturing information from evaluations across two periods: from August 2022 to June 2023 (dated August 2023); and July 2023 to February 2024 (dated March 2024). The reviews found:

- entities’ ratings for Finance’s overall advice and support improved by 13 percentage points between the two reporting periods, with 87 per cent providing a ‘good’ rating or above in the August 2023 report, and 100 per cent providing the same rating in the March 2024 report.57

- suppliers’ ratings for Finance’s overall advice and support improved by two percentage points between the two reporting periods, with 93 per cent providing a ‘good’ rating or above in the August 2023 report and 95 per cent in the March 2024 report.

2.21 In both the August 2023 and March 2024 reports, 94 per cent of village suppliers thought that Finance provided ‘appropriate/useful guidance on best practice implementation of the village model, to help with campaigns’. The number of respondents who identified areas of additional guidance or support that Finance could provide fell from 42 per cent in the August 2023 report to 26 per cent in the March 2024 report (16 percentage point decrease).

Has Finance managed emerging risks and issues relating to government advertising?

Finance has arrangements to manage risks relating to brand safety on social media platforms. Given the changing nature of campaign activities there are emerging gaps in relation to the use of media partnerships, public relations and influencers. Gaps relate to the appropriateness of the level of information relating to these activities provided for final government review and the attribution of campaign materials. There is an absence of guidance around emerging risks, including to brand safety, relating to the potential use of AI and emerging technologies in advertising and information campaigns. Finance extended the whole-of-government Master Media Agency contract after all extension options had been exercised.

Evolving communication activities

2.22 Government advertising campaigns are increasingly using communication activities such as media partnerships58, public relations and influencers59, in addition to, or instead of, established communication channels such as the placement of advertisements on television, radio, outdoor displays and in cinemas. Campaigns assessed in this audit have included media partnerships, public relations and influencers.60 Key aspects of the framework — such as government approval and accountable authority certification — are primarily focused on advertisements, meaning there is a risk that different communication activities, as described above, are not subject to the same level of oversight or they are not addressed in guidance provided by Finance.

Definition of advertising

2.23 The 2022 Guidelines distinguish between ‘advertising campaigns’ and ‘information campaigns’61, stating that ‘An advertising campaign includes paid media placement and an information campaign does not’. Advertising campaigns with a budget of $250,000 (exclusive of GST) or more are subject to review by the ICC and accountable authority certification. Advertising campaigns with a budget of $500,000 (exclusive of GST) or higher are also subject to review and approval by the Government Communications Subcommittee (GCS). Information campaigns are not subject to these review steps, irrespective of budget. Whether campaign activities or materials constitute ‘advertising’ also affects authorisation requirements for campaign materials (see paragraphs 2.31 to 2.32).

2.24 In September 2024, Finance issued guidance clarifying the definition of ‘paid media placement’, which states that:

“Paid media placement” refers to communication material that is placed in an environment or in front of an audience for a fee. It encompasses all forms of advertising, including, but not limited to, standard advertising placement, media partnerships and paid influencer activity.62

Certification and approval of paid partnership and public relations activities

2.25 The arrangements for approval by the GCS and certification by the accountable authority are timed to allow for the review of advertising materials.63 This does not always allow for the review of other campaign materials, such as those relating to media partnerships, public relations activities and influencers, which may still be in development at the time of GCS review and accountable authority certification.64

2.26 The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), AEC and Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) campaigns reviewed in this audit included media partnership and public relations materials. Entities’ review of final media partnership and public relations materials varied.

- In the AGD campaign, no media partnership materials and only a small number of public relations materials had been created at the final government review and accountable authority certification stage.65

- In the Health campaign, five of the media partnership materials and no public relations materials were submitted at these review stages.66

- In both the AGD and Health campaigns, materials were later reviewed and approved by officials prior to their use in the campaign.67

- In the AEC campaign, the Electoral Commissioner reviewed and approved final media partnership and public relations materials prior to their use.68

2.27 Auditor-General Report No. 17 2021–22, Australian Government Advertising: May 2019 to October 2021 (2022 ANAO Government Advertising Report) included a recommendation that: ‘The Department of Finance clarify the application of certification requirements for public relations activities under the 2020 Australian Government Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities.’69 In Auditor-General Report No. 17 2023–24, Implementation of Parliamentary Committee and Auditor-General Recommendations — Department of Finance, this recommendation was assessed as ‘not implemented’.70

2.28 Finance provides guidance to entities on accountable authority certification. In September 2024, Finance updated its guidance to clarify that certification requirements applied to both advertising and non-advertising activities, including public relations:

The Accountable Authority considers the campaign in its entirety and certifies that both advertising and non-advertising activities comply with the Guidelines.

This includes activities described as “public relations”, “community engagement” or “below the line.” These terms are commonly used to describe communication approaches that seek to influence the attitudes, knowledge or behaviour of an audience through communication methods that are not advertising and do not require a placement fee. Activities include, but are not limited to, editorial media, digital content/social media, stakeholder engagement and events. Public relations activity often targets priority audiences, including First Nations Australians and people from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds.71

2.29 The guidance further states that:

A comprehensive communications strategy outlining intended public relations, media partnership, and/or influencer activity should be submitted to the Accountable Authority to allow for proper review of all campaign elements as part of the certification process.

Opportunity for improvement

2.30 Finance could review the appropriateness of the level of information relating to media partnerships, public relations and influencers provided as part of government review of advertising campaigns.

Authorisation and attribution of campaign materials

2.31 In 2022, Finance developed and circulated an information sheet regarding authorisations for advertising campaigns which states:

The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918, the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 and the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 contain similar requirements relating to the authorisation of advertisements that contain electoral, referendum or political matter. This ensures that regulators and Australian voters know who is responsible for the statements contained in advertising and other materials.

Because of the broad definitions of electoral and political matters contained in these Acts, the Australian Government has adopted a convention of authorising its advertising campaigns to ensure they comply with these laws.72

2.32 The information sheet provides specific instructions on what authorisation statements are to be included in different forms of advertisements and the form the statements should take. This applies to advertisements and campaign websites only. The information sheet does not specify requirements for media partnership content or public relations activities.

2.33 Finance has provided advice to entities on ‘attribution’ of entities’ funding of, or contribution to, media partnership and influencer materials.73 Finance advised Health in December 2023:

There are a few ways we could attribute content when/if using influencers or paid partnerships, it will depend on the platform used as well as the content design. Some ways that you can attribute include Sponsored by Australian Government or in Partnership with Australian Government or #Ad or #Sponsorship or #PaidPromotion. Of course, you can have the talent say it.

2.34 Finance advised AGD in January 2024:

due recognition is required in some form for media partnerships where the Government has contributed funding but doesn’t have full control of the content. Usually an “in partnership with the Australian Government” or “brought to you by the Australian Government” is sufficient …

2.35 Finance has referred entities to section 2.7 of the Australian Association of National Advertisers’ Code of Ethics, which states:

Influencer and affiliate marketing often appears alongside organic/genuine user generated content and is often less obvious to the audience. Where an influencer or affiliate accepts payment of money or free products or services from a brand in exchange for them to promote that brand’s products or services, the relationship must be clear, obvious and upfront to the audience and expressed in a way that is easily understood (e.g. #ad, Advert, Advertising, Branded Content, Paid Partnership, Paid Promotion). Less clear labels such as #sp, Spon, gifted, Affiliate, Collab, thanks to … or merely mentioning the brand name may not be sufficient to clearly distinguish the post as advertising.

2.36 Greater consistency in advice could be achieved by Finance developing and issuing standardised guidance relating to attributions on media partnership, public relations and influencer materials.

Opportunity for improvement

2.37 Finance could develop guidance for entities on the attribution of media partnerships, public relations and influencer materials.

Brand safety

2.38 Finance manages brand safety risks with the assistance of the MMA, which at the time of this audit was UM. UM documentation states:

Brand safety refers to mitigating the risk of an advertiser’s exposure to inappropriate content. This could be an ad published next to, before, or within an unsafe environment. In practice, this means avoiding placing ads next to inappropriate content.

2.39 Finance’s contract with UM includes the following regarding brand safety:

- requirements for UM to use its best efforts to mitigate brand safety risks;

- a list of ‘inappropriate content’ that advertising should not appear alongside74;

- requirements for UM to monitor and advise the relevant entity and Finance immediately if advertising appears alongside inappropriate content;

- requirements for UM and subcontractors to establish, maintain and review an exclusion list of websites and applications where advertising may and may not appear; and

- reporting requirements for third party verification monitoring, includes details on brand safety.75

2.40 One of the service level agreements identified in the UM contract is that:

There are no significant or material instances of Advertising Services or Additional Advertising Services delivered to Customers that are not in accordance with Finance’s and/or the Customer’s brand safety requirements.

2.41 Finance advised the ANAO in August 2024 that ‘There have not been any identified issues to warrant documentation or reporting of non-compliance with this service level.’

2.42 UM provides Finance with brand safety appraisals that assess brand safety risks associated with different digital platforms. This includes new and emerging platforms that have not hosted Australian Government advertising before and platforms for which brand safety concerns or incidents have previously arisen. The assessments present information from pilots undertaken in which brand safety controls and performance of platforms not currently used in government advertising have been tested. The brand safety appraisals provide UM’s overall assessment on digital platforms, including recommendations for applications within platforms that are considered brand safe and those that are not.

2.43 Brand safety requirements for non-digital media are captured in the terms and conditions agreed with individual media outlets. Finance advised the ANAO in August 2024:

Brand safety risks are most prevalent in the digital space given its seemingly endless volume of user generated content. Given its relative risk profile, in comparison to more traditional forms of media that are subject to higher levels of industry scrutiny (e.g. content classifications, Broadcasting Services Act etc.), the level of emphasis on digital brand safety approaches is appropriate.

2.44 Entities making media placements through UM are asked for brand safety requirements specific to their campaigns.

Brand safety incidents

2.45 Evidence provided by Finance indicates that there was one brand safety incident during the audit period. In September 2022, Finance was alerted to a risk to brand safety for Australian Government advertising on the Twitter platform.76 This related to the placement of advertisements on individual Twitter profiles that featured inappropriate content, as identified in the UM contract. UM provided Finance with advice on Twitter’s response to the incident and which Australian Government campaigns were affected. UM’s recommended response was to temporarily pause advertising on the platform and to cease advertising on Twitter search results77 and profiles78, to which Finance agreed.

Government advertising on TikTok

2.46 On 4 April 2023, AGD issued Protective Security Policy Framework Direction 001-2023 (the Direction), preventing the installation of TikTok on Government devices, unless a legitimate business reason exists. The Direction stated:

The TikTok application poses significant security and privacy risks to non-corporate Commonwealth entities arising from extensive collection of user data and exposure to extrajudicial directions from a foreign government that conflict with Australian law.

On advice from lead protective security entities, I have determined that the installation of the TikTok application on government devices poses a significant protective security risk to the Commonwealth. …

Entities must prevent installation and remove existing instances of the TikTok application on government devices, unless a legitimate business reason exists which necessitates the installation or ongoing presence of the application.79 [emphasis in original]

2.47 In May 2023, Finance provided advice to the Minister for Finance on potential implications of using TikTok for government advertising. Further advice was prepared in November 2023. On both occasions the advice related to the use of TikTok in government advertising, as the Direction did not address this.

2.48 In April 2024, Finance advised the ANAO that there was no official position on the use of TikTok for government advertising. The first non-corporate Commonwealth entity to place paid advertising on TikTok was Health in its Give up for Good campaign, which launched in June 2024.80 Prior to this, entities have engaged with media partnerships and influencers who have used TikTok for campaign activities, including Health’s Youth Vaping Education (phase one) campaign, which is discussed in Chapter 5 of this report.

Social media influencers

2.49 In August 2018, the government decided that social media influencers were not to be used in government advertising campaigns unless a compelling case and risk mitigation strategy was provided to the Service Delivery Committee of Cabinet (SDCC).81 This was in response to negative media attention relating to the use of social media influencers in campaigns administered by Health and the Department of Defence (Defence).82 In mid-August 2018, Finance advised Australian Government entities of the government’s decision that ‘with immediate effect, paid social media influencer strategies are not to be used in campaign advertising and/or related public relations activities’.

2.50 In March 2023, Finance prepared advice for government on the use of social media influencers in campaign advertising. The advice included proposed guidance documents for entities considering the use of social media influencers and vetting processes that entities could undertake. The submission containing the advice was not signed by the Minister for Finance. Finance advised the ANAO in May 2024 that:

GCS agreement, earlier this year [2024], to implement the youth vaping campaign (Health) which contained both the use of influencers and TikTok, signalled that these channels could be utilised for Australian Government campaign communications on a case-by-case basis.83

2.51 Finance issued guidance on the use of social media influencers in campaigns in September 2024.84 The guidance stated that:

By its nature, the use of social media influencers requires a willingness to engage with a level of risk in order to obtain the benefits of engagement that influencers can bring through their authenticity. Accordingly, the proposed use of social media influencers needs to be supported by a robust brand safety risk mitigation strategy to minimise any potential reputational damage to the Australian Government through association or alignment with controversial or inappropriate behaviour of nominated talent.

Thorough due diligence checks must be undertaken for proposed influencer talent. Checks, conducted by the department, public relations agency, or both, should be ongoing over the duration of the campaign. Consideration should be given to determining the appropriate frequency of checks (daily, weekly etc).

In particular, past social media posts and public activity should be reviewed to assess any potential reputational damage to the Australian Government through association or alignment with controversial or inappropriate online behaviour.

The use of artificial intelligence and emerging technologies

2.52 Outside of the government context, there has been increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI)85 and emerging technologies in advertising, including in the development and distribution of advertising materials and analysis of related data.86

2.53 In September 2024, the Digital Transformation Agency published the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government, which introduced mandatory requirements for non-corporate Commonwealth entities.87 The policy states that it ‘provides a framework to position the Australian Government as an exemplar under its broader safe and responsible AI agenda.’88 It established a requirement for entities to ‘designate accountability for implementing this policy to accountable official(s)’89 and ‘make publicly available a statement outlining their approach to AI adoption and use’.90 The policy further states that entities should consider ‘Integrating AI considerations into existing frameworks’.91

2.54 Finance advised the ANAO in October 2024 that ‘Finance is not aware of the use of artificial intelligence in the production of final campaign materials’ and that guidance had not been provided to entities on the use of AI in advertising campaigns.

Recommendation no.1

2.55 The Department of Finance develop supporting policy and guidance to identify and manage emerging risks, including to brand safety, relating to the use of artificial intelligence and emerging technologies in government advertising campaigns.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

2.56 Finance agrees the two recommendations directed to the Department and will take appropriate action to address the matters raised.

Administration of mandatory procurement arrangements

2.57 Finance is responsible for managing the mandatory procurement arrangements relating to government advertising. This includes the MMA contract, the whole-of-government campaign evaluation contract and the GCCP.92 Use of these arrangements is mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities, with exceptions for Defence Force Recruiting campaigns, which are not required to use the GCCP, and campaigns undertaken by the AEC, which is exempt from using the GCCP and the whole-of-government evaluation supplier.93

2.58 Mandatory procurement arrangements with a sole supplier or a limited number of suppliers can make it difficult to demonstrate the achievement of value for money. This is particularly applicable where the suppliers are appointed following a limited tender process, which was the case for Hall & Partners94 and the GCCP. Finance has implemented measures in the contractual arrangements with each supplier to mitigate risks relating to the achievement of value for money, which are outlined below.

Master Media Agency services — Universal McCann

2.59 In 2018, Finance appointed Universal McCann (UM) as the sole supplier MMA for the period 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2021 following an open tender process.95 The contract end date was extended in April 2021 with an end date of 30 June 2024. In May 2024, the contract was varied again to extend the end date until 30 September 2024.96

2.60 Finance’s contract with UM for the period 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2024 included an annual retainer and potential performance payments.97 During the period 1 July to 30 September 2024 (second contract extension), Finance’s contract with UM included a retainer but no performance payments.98

Customer satisfaction assessment

2.61 During the audit period, three annual performance assessments of the contract were undertaken by a third-party contractor (Kantar Public, now known as Verian) via Customer Satisfactions Surveys. These were in November 2022, November 2023 and December 2024. The surveys assessed customer (entity) satisfaction with UM’s performance in delivering campaign and non-campaign advertising and opportunities for improving service delivery.99 UM’s Customer Satisfaction Survey scores for 2021–22, 2022–23 and 2023–24 are presented in Table 2.1.