Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

ASIC's Processes for Receiving and Referring for Investigation Statutory Reports of Suspected Breaches of the Corporations Act 2001

The objectives of this audit were to:

- examine the effectiveness of ASIC's processes for receiving reports of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act; and

- assess the efficiency with which statutory reports are referred and investigated by ASIC.

The audit commenced in February 2006. ANAO undertook an assessment of ASIC's processes for receiving and referring for investigation statutory reports. ANAO also undertook a detailed examination of a random sample of 416 statutory reports received by ASIC in the period 2002–03 to 2004–05.

The audit scope did not extend to the role of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions in prosecuting offences referred to it by ASIC.

Summary

Background

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) enforces and regulates company and financial services laws to protect consumers, investors and creditors 1. It was established under section 261 of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act). The ASIC Act provides ASIC with a range of powers and functions as are conferred on it by or under the corporations legislation. The Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act) provides the regulatory framework within which Australian companies must operate and also provides that ASIC has general administration of the Corporations Act.

Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act is entitled ‘External Administration'. It deals with the different means of reorganising the manner in which a company is controlled or arranging for a company to be wound up. These circumstances may arise simply because the company's directors and shareholders wish to cease operations. However, the primary focus of Chapter 5 is on companies that have become insolvent and is intended to protect the interests of various stakeholders, especially creditors of insolvent companies.

If a company is about to become, or has become, insolvent, an independent person may be appointed to protect stakeholders' interests. Depending on circumstances, this person may be a receiver, an administrator or a liquidator (collectively referred to in this report as external administrators). An external administrator's primary task is to examine the company's records and recommend the most appropriate course of action to the company's stakeholders. This may include allowing the company to continue trading in an attempt to restore it to financial health or winding it up in an orderly fashion that best preserves stakeholders' interests.

As part of external administrators' responsibilities under Chapter 5, sections 422, 438D and 533 of the Corporations Act require them to report to ASIC, among other things:

- suspected breaches of the Corporations Act;

- any misapplication or retention of funds; and

- any negligence, default, breach of duty or breach of trust,

by past and present company officers or members. Liquidators are under a further specific obligation to report to ASIC where a corporation may be unable to pay its unsecured creditors more than fifty cents in the dollar. Reports made pursuant to these sections are referred to in this report as statutory reports.

Role of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services in relation to the Corporations Act

Section 243 of the ASIC Act creates a role for the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services (JCCFS) to, among other things, inquire into the operations of the corporations legislation. Since ASIC's establishment, the JCCFS has held a number of inquiries in accordance with this mandate.

On 14 November 2002, the JCCFS resolved to ‘consider and report on the operations of Australia's insolvency and voluntary administration laws'. One of the Inquiry's Terms of Reference was to consider ‘the reporting and consequences of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act' as required by sections 422, 438D and 533 of the Corporations Act.

In its June 2004 report, the JCCFS stated that the reporting obligations:

are among the most important mechanisms in the law for bringing to light possible breaches of the Corporations Act [and] it is vital that this function be performed to a high standard as external administrators are the primary investigators of the affairs of insolvent companies. 2

In its Report, the Committee raised a number of concerns about ASIC's investigation of reported breaches and stated that it was ‘not convinced that sufficient priority is being given to the assessment and investigation of reported possibly serious breaches of the Corporations Act'. The Committee also raised concerns that there may be a lack of resources for that task.

Among the 63 recommendations that the JCCFS made in its report was the following:

The Committee requests that ANAO conduct a performance audit of ASIC's processes in receiving and investigating statutory reports.

In response to the JCCFS' recommendation, a potential audit of ASIC's Processes for Receiving and Referring for Investigation Statutory Reports of Suspected Breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 was included by the Auditor General in the 2005–06 Performance Audit Work Programme.

Audit Approach

The objectives of this audit were to:

- examine the effectiveness of ASIC's processes for receiving reports of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act; and

- assess the efficiency with which statutory reports are referred and investigated by ASIC.

The audit commenced in February 2006. ANAO undertook an assessment of ASIC's processes for receiving and referring for investigation statutory reports. ANAO also undertook a detailed examination of a random sample of 416 statutory reports received by ASIC in the period 2002–03 to 2004–05.

The audit scope did not extend to the role of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions in prosecuting offences referred to it by ASIC.

Audit Conclusions

A key role for ASIC is to investigate serious corporate crime and misconduct. In this respect, effective enforcement and regulation engenders confidence in Australia's financial markets, products and services. In its June 2004 report, the JCCFS stated that the provisions of the Corporations Act which require external administrators to report breaches of the Act to ASIC are among the most important mechanisms of the law.

Statutory reports lodged by external administrators are an important source of ‘front line' information for ASIC about possible breaches of the Corporations Act. ASIC has effective processes in place to ‘risk score' initial reports from external administrators so as to, among other things, identify those matters of most regulatory significance in which case further information is sought from the external administrator. 3 However, ASIC has not had processes in place to ensure this further information is actually obtained.

Additional information obtained from external administrators is subject to a further process of evaluation. This is undertaken so as to identify those matters where regulatory action is available and appropriate. Subject to various enforcement resourcing and other considerations, action may then be taken by ASIC to act upon reports of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act reported by the external administrator.

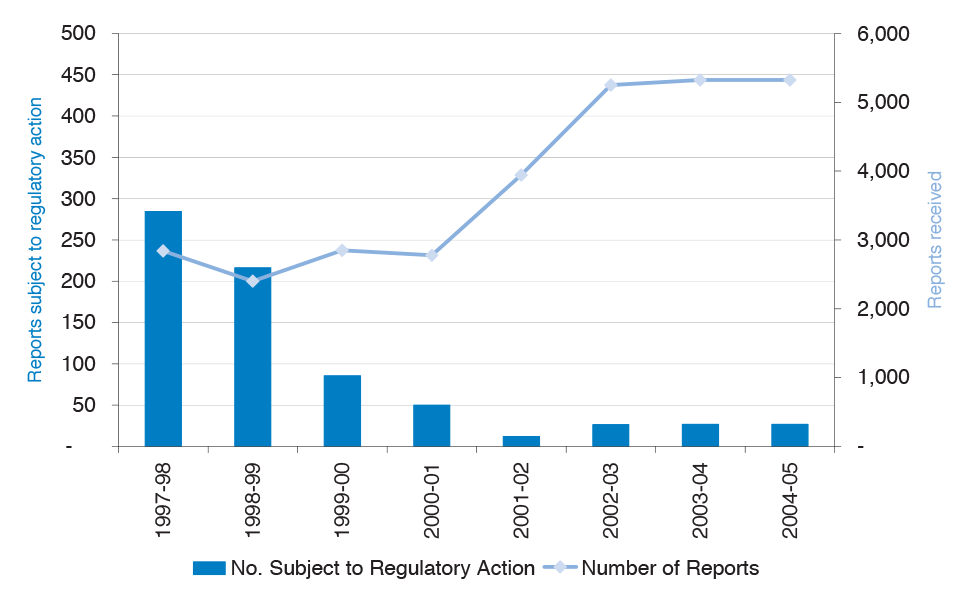

Over time, ASIC has acted on fewer statutory reports, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of reports received.4 For example, in the three years between 1997–98 and 1999–00, ASIC received an average of almost 2 700 statutory reports of alleged breaches of the Corporations Act and undertook investigation or surveillance activities on an average of almost 200 in each year. In comparison, in each of the three years between 2002–03 and 2004–05, ASIC received an average of almost 5 300 reports of alleged breaches but undertook investigation or surveillance activities on an average of 27 each year. 5

The JCCFS was concerned that insufficient priority was being given to the assessment and investigation of statutory reports of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act. In this respect, the significant reduction in activity with respect to statutory reports was not the result of a decision to act on fewer reports. Rather, ASIC advised ANAO in December 2006 that the reduction had occurred mainly in surveillance activity (rather than formal investigations) as a result of a deliberate regulatory strategy to move from 'reactive' to 'proactive' surveillances in the area of insolvency.

It is properly a matter for ASIC to determine where the balance lies in deciding whether to act upon reports of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act reported by external administrators. However, in light of the marked reduction in regulatory activity and of the concerns expressed by the JCCFS, it is timely for ASIC to review its current approach, including the opportunities for increasing the number of reports it investigates.

Key findings

Receipt and assessment of reports (Chapter 2)

The processes by which statutory reports are received and assessed by ASIC have changed over time. In relation to the receipt of reports, one of the most notable changes has been the introduction in 2002–03 of a facility to allow external administrators to be able to lodge an initial statutory report (known as a Schedule B report) electronically. In 2005–06, 83 per cent of Schedule B reports were lodged electronically. ASIC uses a computer system to ‘risk score' the Schedule B reports that it receives electronically.

Since 2004–05, where the risk score for a report does not meet a predetermined threshold, the report for the activity is finalised and a letter is automatically generated and sent to inform the external administrator that no further action will be taken. Risk scoring is intended to allow ASIC to quickly identify the matters of most regulatory significance with minimal use of the liquidators time. ASIC advised the ANAO that this enables it to devote its resources to more intensive work on more detailed reports and provide liquidators with assistance to complete and manage their administrations in a timely manner according to law.

External administrators are required by law to report to ASIC suspected breaches of the Corporations Act. In addition to this obligation, administrators have the discretion to lodge further reports. In this context, ASIC advised the ANAO that correct recording of statutory reports is important for the following reasons:

- it is of critical importance to external administrators that when they provide certain types of information to ASIC, particularly information that comprises suspected but unsubstantiated or bare allegations of contraventions by an individual or entity, that such statements attract the qualified privilege afforded by ss 426, 442E and 535 of the Corporations Act;

- ASIC is required to maintain a register and make all documents lodged with it publicly available for inspection, unless the document is specifically exempted by the law. Sub-section 1274(2)(a)(iv) of the Corporations Act creates an exception to the public inspection rule for statutory reports and consequently they must be differentiated from publicly available information; and

- Section 15 of the ASIC Act provides that ASIC may conduct a particular type of investigation with respect to statutory reports received under sections 422 and 533 of the Corporations Act. Clear identification of reports received under those sections allows ASIC to preserve as many bases for investigation as the legislation provides.

ANAO found that ASIC's recording of statutory report information was accurate to a high degree. However, its reporting to the Parliament and other stakeholders has been deficient in the following respects:

- Prior to ANAO's audit, ASIC had not documented its procedures for calculating figures relating to statutory reports for publication in ASIC Annual Reports.6

- The form in which information on statutory reports has been presented in ASIC's Annual Reports has varied over time, and there have been a series of methodological changes. The changes to the methodologies used by ASIC in successive Annual Reports impede year-on-year comparison of the extent to which ASIC has taken regulatory action on statutory reports.

- In some years ASIC reclassified its recording of statutory reports from the ‘analysed, assessed and recorded' category to the ‘resolved' or ‘investigation' categories in its Annual Reports. However, there was no auditable trail of the activities that ASIC had reclassified for 2002–03 and 2003–04. In addition, for 2004–05, ASIC did not conduct an examination of the records underlying the reclassified activities. Following ANAO enquiries, ASIC identified that the reclassification of some activities in 2004–05 had been erroneous. As a result, in 2004–05, ASIC reported that seven per cent of statutory reports had been ‘resolved' when in fact the correct figure was only one per cent.7

Investigation and enforcement (Chapter 3)

Where ASIC identifies that a statutory report raises issues of regulatory significance, further information about the matter is sought by ASIC from the external administrator. However, that additional information is not always obtained by ASIC. Specifically, in ANAO's sample, no further report was obtained by ASIC in almost 40 per cent of instances where the additional information was requested.

ASIC has a wide range of possible remedies available to it to deal with offences identified in statutory reports or other deficiencies which warrant some sort of regulatory action. These range from warning letters to directors of companies for less serious offences, to prosecution and potentially imprisonment for more serious offences. However, ANAO's analysis revealed that, although the number of statutory reports alleging offences received by ASIC has increased significantly over time, regulatory action is taken by ASIC in relation to a relatively small number of those reports. Specifically, of the average 5 300 statutory reports received in each year from 2002–03 to 2004–05, ASIC took regulatory action8 on no more than 27 in any one year (0.5 per cent). This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Reports alleging offences received and reports subject to investigation or surveillance activity:

1997–98 to 2004–05

Given the large number of statutory reports received by ASIC each year that allege offences against the Corporations Act, it is appropriate that ASIC has systems in place to prioritise its regulatory actions, through risk scoring. Nevertheless, as stated by the JCCFS, the statutory reporting obligations are among the most important mechanisms in the law for bringing to light possible breaches of the Corporations Act. Accordingly, the small number of statutory reports subject to regulatory action by ASIC each year indicates that there is opportunity for greater regulatory action on these reports.

Prosecutions initiated by ASIC

Under the terms of the Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) has the primary responsibility for instituting and conducting prosecution of offences against Commonwealth law. This gives effect to the principle enunciated in the Prosecution Policy that there should be a separation of the investigative and prosecutorial functions in the Commonwealth criminal justice system. However, the Prosecution Policy allows for a few Commonwealth agencies, with the agreement of the CDPP, to conduct their own summary prosecutions for ‘high volume matters of minimal complexity'.

In 1992, the CDPP and ASIC agreed a set of Guidelines under which ASIC was permitted to conduct prosecution of minor regulatory offences. In 2003 the two organisations reached agreement that ASIC could prosecute offences under a number of explicitly nominated sections of the Corporations Act. In its enforcement procedures, ASIC did not pay due regard to the clear terms of the agreement. As a result, on 26 occasions between 2002 and 2006 ASIC had, without consulting the CDPP, prosecuted offences for which it had no specific agreement to do so from the CDPP. 9

Disqualification from acting as a director

The Corporations Act empowers ASIC, independently of the Courts or the CDPP, to disqualify a person from managing corporations for up to five years. This power is intended to protect the public from the conduct of a person who has demonstrated an inability to manage corporations, rather than to punish the person.

Exercise of this power requires accurate recording of statutory reports, which ASIC has demonstrably achieved. ASIC's use of its disqualification power has decreased considerably over time. In addition, where ASIC has exercised its disqualification power, there have often been delays in its application. There are a number of factors leading to these two circumstances, including:

- ‘risk scoring' and other processes intended to focus ASIC's attention on the most serious regulatory matters;

- guidance material provided to analysts not accurately reflecting the circumstances in which ASIC can exercise its power to disqualify persons; and

- incorrect application of the legislative requirements by analysts when assessing which matters are eligible for disqualification action.

ASIC advised ANAO that it has recently conducted national training in relation to its banning powers. However, there remains a need to ensure guidance material relied upon by analysts is accurate.

Improvement opportunities

The ANAO made five recommendations arising from this audit. Given the large number of reports received each year that allege offences, and the JCCFS' concerns that sufficient regulatory priority be given to such reports, the key recommendation (Recommendation No. 2) is that ASIC identify opportunities for increasing the number of statutory reports that it currently investigates.

The remaining recommendations are aimed at:

- improving the clarity of ASIC's reporting to the Parliament;

- maintaining the separation between investigatory and prosecution roles, except where the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions has agreed otherwise;

- timely follow-up of additional information requested from external administrators where an initial report has raised significant issues; and

- ensuring that ASIC's guidance material to analysts correctly reflects the provisions of the Corporations Act relating to the disqualification of directors.

Agency response

ASIC agreed to all the audit recommendations. ASIC's full response to the audit is provided at Appendix 1 to the report. ASIC also provided a summary of its comments as follows:

ASIC generally agrees with the recommendations made by the ANAO. In particular ASIC recognises that as a result of its Assetless Administration and External Administrator Assistance programs and additional funding provided by the Government in 2005, there are greater opportunities to increase the number of statutory reports that ASIC investigates. ASIC confirms that all recommendations have been or are currently being reviewed for implementation.

ASIC is continuing to work closely with the insolvency industry to increase the quality and timeliness of statutory reports alleging offences, and thereby increase the levels of regulatory action available to ASIC to take in response to statutory reports.

ASIC also believes that the additional funding provided by the Government will allow ASIC to increase its impact in this area going forward. Early indications of the success of these initiatives has been the disqualification of 43 company officers for a total of 163.5 years in 2006; and prosecution of 494 company officers for the failure to assist external administrators, resulting in fines and costs awards of $1 039 613.

ASIC welcomes the confirmation by the ANAO of the high degree of accuracy of our processes for the receipt and recording of statutory reports of suspected breaches of the Corporations Act 2001. Since our introduction of electronic reporting by external administrators and automated risk assessment for these electronic reports on 1 July 2004, ASIC has been consistently working to improve the quality of our data capture and more importantly the analysis of information collected to ensure a timely and appropriate regulatory response to statutory reports.

Footnotes

1 ASIC website www.asic.gov.au

2 Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Corporate Insolvency Laws: a Stocktake, June 2004.

3 In 2004–05, ASIC requested further information in relation to 12 per cent of the statutory reports received from external administrators.

4 Over the period 1997–98 to 2004–05, the number of reports received alleging offences increased by almost 90 per cent, while the number of reports that ASIC investigated or subjected to surveillance decreased by more than 90 per cent.

5 Of the remainder, an average of 90 per cent in each of the three years were ‘analysed, assessed and recorded' which resulted in external administrators being advised that ASIC did not intend to take any further action.

6 ASIC prepared for ANAO a documented entitled ʻStatutory Reports – Annual Report Overviewʼ which was intended to explain these changes. However, ANAO analysis showed that the Annual Report Overview did not correctly reflect the processes used in the calculation of the statistics for the 2004–05 Annual Report.

7 This error was disclosed in ASICʼs 2005–06 Annual Report.

8 That is, reports referred for compliance, investigation or surveillance (see page 23 of ASICʼs 2005–06 Annual Report).

9 This did not affect the validity of the prosecutions.