Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Electoral Commission’s Procurement of Services for the Conduct of the 2016 Federal Election

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess whether the Australian Electoral Commission appropriately established and managed the contracts for the transportation of completed ballot papers and the Senate scanning solution for the 2016 Federal Election.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is responsible for conducting federal elections. To assist it to conduct the 2016 federal election, the AEC procured the services of ten organisations under 17 contracts to transport ballot papers and other items at a cost of $8.7 million. The AEC also procured the services of an ICT supplier for $27.2 million to develop and deliver a Senate scanning system. This was a semi-automated process for capturing voter preferences from Senate ballot papers for entry into the count, as the previous manual process was no longer considered viable following significant changes to Senate voting provisions in the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act).

2. The procurements were undertaken, and the Senate scanning system developed, in a tight timeframe given the changes to the Electoral Act were passed 18 March 2016, the double dissolution election was announced 9 May 2016 and the election was held 2 July 2016.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of this audit was to assess whether the AEC appropriately established and managed the contracts for the transportation of ballot papers and the Senate scanning system for the 2016 federal election. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Did the procurement processes demonstrably achieve value for money?

- Were key risks to the security and integrity of ballot papers, and of ballot paper data, addressed?

- Did the AEC obtain adequate assurance of the service deliverables and of the effectiveness of risk treatments?

Conclusion

4. In delivering the 2016 federal election the AEC established and managed contracts for the transportation of ballot papers and, in a short timeframe, for a Senate scanning system. Insufficient emphasis was given by the AEC to open and effective competition in its procurement processes as a means of demonstrably achieving value for money. Its contract and risk management was also not consistently to an appropriate standard.

5. The AEC has not demonstrably achieved value for money in its procurement of Senate scanning services. It has not used competitive pressure to drive value nor given due consideration to cost in its procurement decision-making. The AEC sought to encourage competition amongst transport providers but at times struggled to achieve value for money. It would have benefited from additional logistics expertise and transport industry knowledge when establishing and managing transport arrangements.

6. Most contracts with suppliers contained comprehensive security requirements that appropriately reflected the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy. The AEC was generally satisfied that the requirements were implemented.

7. The AEC addressed risks to the security and integrity of ballot paper data through the design and testing of the Senate scanning system. The AEC accepted IT security risk above its usual tolerance. Insufficient attention was paid to ensuring the AEC could identify whether the system had been compromised.

8. The Senate scanning and transport suppliers delivered the services as contracted. The AEC had limited insight into whether its contractual and procedural risk treatments were effective. Going forward, the AEC needs to be better able to verify and demonstrate the integrity of its electoral data.

Supporting findings

Demonstrating value for money

9. The AEC procured the services of ten organisations under 17 contracts to transport ballot papers and other items at a cost of $8.7 million. The AEC also procured the services of an ICT supplier for $27.2 million to develop and deliver a Senate scanning system.

10. The AEC’s procurement processes did not encourage open and effective competition sufficiently.

11. Approval was recorded by the financial delegate for 20 of the 25 procurements examined. On six occasions, costs exceeded the approved amount prior to a new approval being sought.

12. Adequate consideration was given to costs and benefits in the procurement of the transport services. The documentation on the transport procurements outlined how value for money was considered but did not always demonstrate that value for money would be achieved.

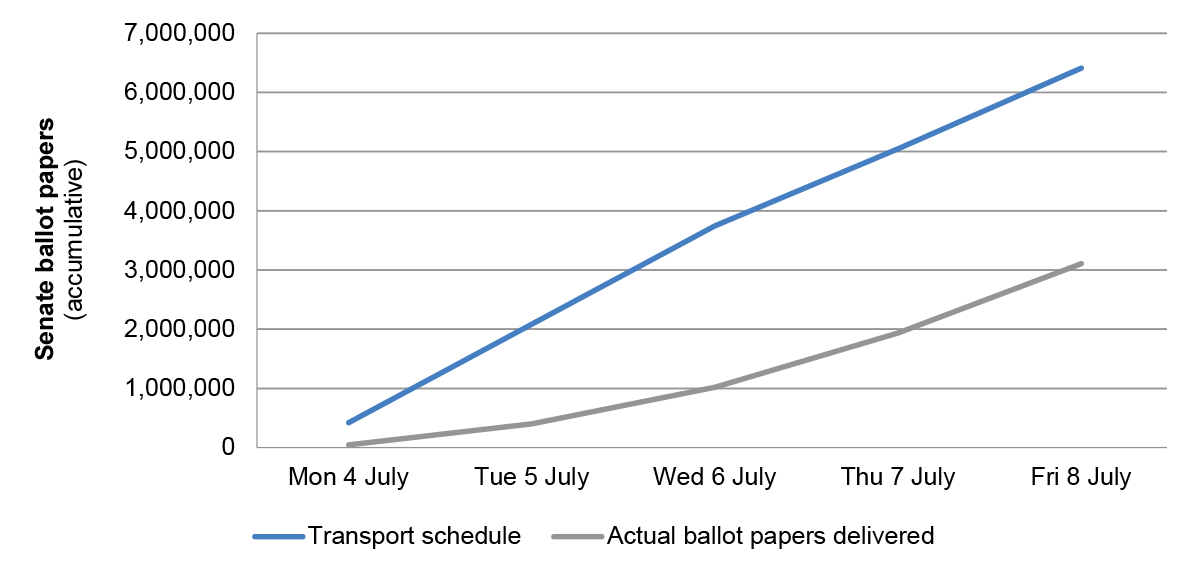

13. No consideration of financial cost was evident in the records of the AEC’s decision-making to implement the Senate scanning system. Timeliness, quality and risk were taken into account. The documentation on the Senate scanning system procurement indicates that inadequate consideration was given to assessing value for money and did not demonstrate that it was achieved.

Addressing risks to the security and integrity of ballot papers

14. The ten contracts with suppliers procured from the AEC’s transport panel contained security requirements that appropriately reflected the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy. The seven contracts with suppliers procured from outside the transport panel did not explicitly reflect the AEC requirement that ballot papers not be left unattended. The AEC was generally satisfied that the requirements were implemented but with some room for improved adherence.

15. The contracts for the Senate scanning services contained security requirements that appropriately reflected the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy. The AEC verified that the requirements had been implemented.

16. The AEC checked the political activity of suppliers during the procurement process and included political neutrality provisions in each contract. The AEC did not obtain assurance of the political neutrality of personnel transporting ballot papers. The AEC did obtain assurance of the political neutrality of supplier personnel involved in the Senate scanning system.

Addressing risks to the security and integrity of ballot paper data

17. The primary data generated by the Senate scanning system was XML files containing the voter preferences and whether the vote was formal or informal. A cryptographic digital signature on each XML file protected the data from modification. A secondary output was a digital image of each ballot paper.

18. Risks to the integrity of the ballot paper data were managed through system design and testing. To improve integrity, a late decision was made for all voter preferences to be entered by a human operator in addition to being captured by the technology. Any mismatches between the human’s and the technology’s interpretation were investigated and resolved. The AEC does not know the number or nature of mismatches to determine if this was a cost-effective risk treatment.

19. A range of IT security risk assessments were undertaken prior to operation. The AEC assessed that one quarter of the applicable Australian Government controls for treating security risks had not been implemented. The contract with the ICT supplier had not required compliance with the Australian Government IT security framework. The security risk situation was accepted by the AEC but was not made sufficiently transparent.

20. The AEC’s IT security monitoring during system operation was sufficient to support its conclusion that there was no large-scale intentional tampering of the 2016 Senate election data. It did not have a systemic data and analysis plan or adequate visibility of IT security measures.

21. The ballot paper images were securely migrated to the AEC’s repository environment after services were completed. There was a ten month delay in the AEC instructing the ICT supplier to delete electoral data from its environment.

Obtaining assurance

22. Assurance frameworks were in place for the agency and for the Senate scanning system project.

23. The AEC is unaware that any ballot papers were not accounted for. This is a considerably lower level of assurance than its stated performance indicator of accounting for 100 per cent of ballot papers.

24. The AEC relied on the effectiveness of its risk treatments to ensure the integrity of the Senate ballot paper data. It has not undertaken a statistically valid audit to verify or demonstrate data integrity.

25. The contracted transport services achieved the desired results. The AEC had difficulty reconciling invoices received for the services and it was slow in sending ballot papers to the Senate scanning centres.

26. The Senate scanning system was delivered on time and as per contractual requirements. The AEC was not able to demonstrate compliance with all elements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918.

27. The AEC’s post-election evaluation activities gathered lessons to be learned. These should inform improvements to future electoral events, including the transport of election-related materials and the operation of Senate scanning centres.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.30

The Australian Electoral Commission employ openly competitive procurement processes so as to demonstrate value for money outcomes. In those circumstances when competitive procurement processes are not able to be employed, the Australian Electoral Commission document the reasons, appropriately benchmark the quoted fee and record how it was satisfied value for money was being obtained.

Australian Electoral Commission’s response: Agreed with qualification.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.59

The Australian Electoral Commission revise its approach to procuring election-related transport services so as to improve value for money and to provide more efficient access to transport services that meet needs (which can vary between and within States). The approach should be underpinned by logistics expertise and transport industry knowledge.

Australian Electoral Commission’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.38

The Australian Electoral Commission take the necessary steps to achieve a high level of compliance with the Australian Government’s security framework when information technology systems are employed to assist with the capture and scrutiny of ballot papers for future electoral events.

Australian Electoral Commission’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 5.47

When the Australian Electoral Commission uses computer assisted scrutiny in future federal electoral events, the integrity of the data is verified and the findings of the verification activities are reported.

Australian Electoral Commission’s response: Agreed with qualification.

Summary of entity responses

28. The proposed audit report was provided to the AEC. Extracts from the proposed report were provided to Fuji Xerox Businessforce (who were contracted by the AEC to develop and deliver a Senate scanning system).

29. Formal responses to the proposed audit report were received from the AEC and Fuji Xerox Businessforce (see Appendix 1). The AEC also provided a summary response, which is below.

AEC summary response

The 2016 federal election was the largest and, in many ways, most complex in the nation’s history. The Senate voting changes were the most significant reforms to Australia’s electoral system in 30 years. In the extraordinarily short period of three months, and without prior warning, the AEC successfully developed and then implemented a robust, effective, technologically advanced and entirely new system for counting, under high levels of scrutiny, some 15,000,000 Senate votes in multiple locations around Australia.

Further layers of electoral complexity were added by: predictions of a close event (with attendant media and political focus); the election being a double dissolution; the election period following the very recent finalisation of several major boundary redistributions; a shorter than usual timeframe specified for the return of the Writs; the need to develop, test, and deliver a nuanced national education campaign for all voters about the changes; and the election being the first national event since the implementation of the Keelty Report recommendations following the 2013 federal election. Notwithstanding these additional complications, the AEC was keenly aware that failed delivery, non-delivery, or even partial delivery, of the Senate voting reforms would have had catastrophic consequences for Australia’s system of governance with both domestic and international implications.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Australian Government entities when establishing and managing contracts.

Procurement

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 On 9 May 2016, the Parliament was dissolved and a federal election was announced for 2 July 2016. The 2016 federal election was particularly complex for the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) to conduct. Reasons included that it was a double dissolution election, more people were enrolled to vote than ever before (15.7 million), polling day fell during the school holidays, there was a shorter than usual period between polling day and the return of the writ, and significant legislative changes (passed 15 weeks before polling day) needed to be communicated and operationalised.

1.2 In the 2013 federal election, 96 per cent of Senate votes were cast by selecting one group only above the line. It was only the preferences expressed below the line that needed to be entered individually into the count system. With the removal of group voting tickets and introduction of optional preferential voting for the 2016 federal election, all Senate ballot papers needed to have their individual preferences entered into the count system. The previous method of manually keying and verifying the preferences was considered unlikely to be viable on this scale. The AEC procured the design and delivery of a semi-automated process for entering voter preferences (referred to in this audit report as the ‘Senate scanning system’) at a total contract value of $27.2 million. The process involved 14.4 million Senate ballot papers being scanned, and the 101.5 million voter preferences being captured using optical character recognition technology and then verified by human operators.

1.3 The movement and security of 28.8 million completed ballot papers throughout the election period was a major logistical exercise. To assist, the AEC procured the services of ten suppliers under 17 contracts to transport ballot papers and other items at a cost of $8.7 million in 2016. The suppliers were primarily involved in the transport of ballot papers from the printers, the transport of declaration votes across States and the transport of Senate ballot papers to the scanning centre established in each capital city.

Relevant inquiries and audits

1.4 In November 2013, the AEC commissioned Mr Mick Keelty AO APM to undertake an inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the loss of 1370 Western Australian Senate ballot papers following the 2013 federal election (‘the Keelty report’).1 The Keelty report was publicly released on 6 December 2013 and included 32 findings and recommendations, which were accepted by the AEC.

1.5 Following the loss of the Western Australian ballot papers, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters requested that ANAO conduct a performance audit on AEC’s implementation of recommendations arising from earlier ANAO audit reports. The ANAO conducted three related audits covering the recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10.2 Ten recommendations were made across the three audit reports.

1.6 Since 1983, it has been the practice of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters and its predecessors to examine the conduct of each federal election and related matters. The most recent is its ‘Inquiry into and report on all aspects of the conduct of the 2016 Federal Election and matters related thereto’.3

Audit approach

1.7 The objective of this audit was to assess whether the Australian Electoral Commission appropriately established and managed the contracts for the transportation of ballot papers and the Senate scanning system for the 2016 federal election.

1.8 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did the procurement processes demonstrably achieve value for money?

- Were key risks to the security and integrity of ballot papers, and of ballot paper data, addressed?

- Did the AEC obtain adequate assurance of the service deliverables and of the effectiveness of risk treatments?

1.9 The audit examined the arrangements from the procurement of the providers through to the completion of the services. The audit team examined AEC records and it engaged with AEC staff and with the ICT supplier that delivered the Senate scanning system. The audit team could not test the Senate scanning system because it had been decommissioned. The transportation of ballot papers by air freight, internationally and by AEC staff was not in the scope of this audit. Nor was the transfer of ballot papers to storage on completion of the election in the scope (this work comprised a small component of an existing records management contract).

1.10 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $419 077.

1.11 The team members for this audit were Tracey Bremner, William Na, Erica Sekendy, Hannah Conway, Ashish Bajpai and Brian Boyd.

2. Demonstrating value for money

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the processes undertaken to procure the transport and Senate scanning services demonstrably achieved value for money.

Conclusion

The AEC has not demonstrably achieved value for money in its procurement of Senate scanning services. It has not used competitive pressure to drive value nor given due consideration to cost in its procurement decision-making.

The AEC sought to encourage competition amongst transport providers but at times struggled to achieve value for money. It would have benefited from additional logistics expertise and transport industry knowledge when establishing and managing transport arrangements.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the AEC use open, competitive procurement processes wherever possible so as to demonstrably obtain value for money.

The ANAO has also recommended that the AEC revise its approach to procuring election-related transport services so as to improve value for money and to provide AEC State and Divisional Offices efficient access to transport services that meet their needs. The approach should be underpinned by logistics expertise and a better understanding of how the transport industry operates.

What procurements were undertaken?

The AEC procured the services of ten organisations under 17 contracts to transport ballot papers and other items at a cost of $8.7 million. The AEC also procured the services of an ICT supplier for $27.2 million to develop and deliver a Senate scanning system.

2.1 The AEC entered into 17 contracts that included the transportation of ballot papers. The total cost of the transport services requested under these 17 contracts in 2016 was $8.7 million. The contracts were with nine transport providers and one printing firm (which subcontracted to a transport provider).

2.2 The AEC procured the development and delivery of the 2016 Senate scanning services via an existing Deed of Standing Offer it had with an ICT supplier (Fuji Xerox Businessforce). This involved the AEC signing three Work Orders and five Project Change Requests with a total maximum value of $27.2 million, as per Table 2.1 below. The total cost of services invoiced was lower at $27.1 million.

Table 2.1: 2016 Senate scanning services procurements

|

Date signed by AEC in 2016 |

Type of agreement |

Summary of services procured |

Maximum value |

|

24 March |

Work Order |

Design and develop the Senate scanning system to the point of it being election ready. |

$7 638 661.80 |

|

21 April |

Project Change Request |

Include a digital signature on the XML files containing ballot paper metadata. |

$9 528.75 |

|

13 May |

Project Change Request |

Include a method to allow the AEC to view the XML file for an individual ballot paper. |

$10 890.00 |

|

12 June |

Project Change Request |

Redesign the system so that every ballot paper is viewed by a human. |

$230 230.00 |

|

29 June Varied 5 August |

Work Order |

Deliver the Senate scanning system, then store the data and prepare ballot papers for transport to long-term storage. |

$19 220 000.00 |

|

5 July |

Project Change Request |

Stop end-of-day reports from being purged from the ICT supplier’s system. |

$798.60 |

|

28 July |

Project Change Request |

Secure closed-circuit television footage. |

$20 328.00 |

|

2 December |

Work Order |

Migrate the ballot paper images to the AEC’s image repository environment. |

$38 661.00 |

|

Total |

|

|

$27 169 098.15 |

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

Was open and effective competition encouraged?

The AEC’s procurement processes did not encourage open and effective competition sufficiently.

2.3 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) state that procurements should encourage competition. They outline that effective competition requires non-discrimination and the use of competitive procurement processes. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit has outlined that ‘Competition in procurement is important for a number of reasons, including the benefits that competitive pressure brings to demonstrating probity and value for money outcomes’.4

Procurement of transport services

2.4 In 2015–16 the AEC established a panel arrangement for the provision of mail, freight and courier services for electoral event and business as usual requirements. Each provider selected for the panel signed a Deed of Standing Offer agreeing that, on the issue of a Work Order by the AEC, it would supply the requested services on the terms and conditions set out in the Deed. A contract is formed when the Work Order is issued.

2.5 An open tender was used to select the panel members. The resulting panel of four providers did not have the capacity to fulfil the AEC’s transport needs. This was foreseen. It was partially addressed by extending the coverage of some panel members to categories of transport services and/or to States that they had not tendered for. For example, one panel member that had tendered to provide electoral event services in two States was then contracted to service six States/Territories and for business as usual deliveries.

2.6 The intent was that the AEC’s State Offices would request quotes from multiple panel members, evaluate the quotes and then issue a Work Order to the provider that offered best value for money. Whilst this approach has the potential to encourage competition between panel members, the actual level of competition generated was limited. The State Offices rarely received multiple quotes in response to their requests.

2.7 Of the 17 contracts entered into for ballot paper deliveries:

- four were with panel members following the receipt of multiple quotes;

- six were with panel members following the receipt of a single quote; and

- seven were with other organisations following an unsuccessful approach to the panel.

2.8 Some of the panel’s capacity to securely transport ballot papers had been expended on non-sensitive materials. For example, one of the providers that specialised in the secure transport of fragile and sensitive materials declined to quote to deliver ballot papers because its capacity had been exhausted on delivering cardboard items such as ballot boxes and voting screens. Only three of the four panel members were therefore contracted to transport ballot papers.

2.9 The AEC should be able to generate greater competition for its business, especially for the delivery of non-sensitive materials. The AEC could benefit from tapping into the pool of smaller companies5 (such as via a third-party logistics provider) as they may be more attracted to the short bursts of urgent deliveries that characterise an election than were the national providers the AEC had sought to engage. Post-election reviews, and feedback to the AEC from panel members, contained suggestions on how the AEC could make its business more attractive to transport providers and could better harness their capacity and expertise.

Western Australia

2.10 The establishment of the transport panel was in part a response to the recommendations of a 2013 inquiry into the circumstances of 1370 missing ballot papers identified during a recount of Senate votes in Western Australia.6 In preparation for the 2016 federal election, the AEC’s Western Australian office followed its department’s procurement procedures and issued requests for quotes to panel members. No quotes were received in response. One of the panel members advised, ‘Unfortunately due to our existing confirmed AEC commitments for the upcoming federal election, we are not in the position to submit a quotation for your request’. The transport services were then procured by varying the contract used in Western Australia for the 2010 and 2013 federal elections to also cover the 2016 federal election.

2.11 These circumstances indicate that more needs to be done to ensure State Offices have efficient access to a suite of providers with the capacity and capability to meet the AEC’s transport needs, including any State or Division specific requirements.

Procurement of Senate scanning services

2.12 The AEC procured the development and delivery of the 2016 Senate scanning services by seeking a quote from one ICT supplier. To contract that supplier, the AEC varied an existing Deed of Standing Offer and then issued Work Orders and change requests under that Deed.

2.13 The Deed of Standing Offer had been established following an open tender conducted late in 2014 for services described as the ‘scanning of certified lists and data analysis’ and the ‘hosting of certified list page images’. The AEC had estimated the value of these data capture services at $1.3 million over a four year period.

2.14 The services the AEC then procured from the ICT supplier via the Deed were substantially higher in value and broader in scope than could have been foreseen in 2014 by potential providers. Of note is that within the first two years of the Deed being in place the AEC had procured services relating to:

- certified lists for $0.6 million;

- postal vote applications for $2.0 million; and

- Senate scanning services for $27.2 million (as per Table 2.1).

2.15 The majority of the Senate scanning services fell outside the scope of the existing Deed and the costs were not calculated in accordance with the pricing schedule. Substantial amendments were made to the Deed so as to incorporate the Senate scanning services. The ANAO considers that the AEC had therefore procured the services via limited tender (previously known as ‘direct source’). In contrast, the AEC considers the services fell within the scope of the original approach to market in 2014 and, accordingly, publicly reported all the purchases as being by ‘open tender’.

2.16 The ANAO’s analysis is that the AEC’s approach to using this Deed of Standing Offer was inconsistent with the ‘encouraging competition’ principle set out in the CPRs. Additionally, the AEC’s approach came with the risks of over-dependency on a single supplier7 and of reducing the ability of other potential suppliers to be competitive in future approaches to market.

Procurement of services for future electoral events

2.17 To assist in the conduct of future electoral events, in 2017 the AEC undertook a procurement for supply chain expertise and a procurement for Senate scanning services. The approaches taken by the AEC were at odds with the principles underpinning the CPRs; they did not encourage open and effective competition and did not demonstrably achieve value for money.

Supply chain expertise

2.18 The AEC did not conduct an open tender to procure supply chain expertise in 2017. Instead it approached one supplier, GRA Supply Chain, and engaged it by piggy-backing on the Department of Defence’s ‘Research, Scientific, Engineering and Other Technical Services’ panel arrangement. The reported value of the AEC contract was $646 800 over the period 16 October 2017 to 30 June 2019.

2.19 When an entity uses a Deed of Standing Offer or contract that was established by another entity, the CPRs state that it must ensure that ‘the goods and services being procured are the same as provided for within the contract’. The AEC was therefore required by the CPRs to ensure that the supply chain services were the same as provided for within the panel arrangement established by the Department of Defence. The panel arrangement had been described to potential tenderers as an ‘arrangement to provide a broad range of research, scientific, engineering and other technical services to support the Defence Science and Technology Organisation’s (DSTO) research and development projects’. The panel arrangement was not clearly applicable to the nature of the supply chain services the AEC was purchasing.

2.20 The AEC’s approach was inconsistent with the CPR expectation that procurements ‘encourage competition and be non-discriminatory’. The AEC invited only one supplier to quote, notwithstanding that the Department of Defence instructed users to approach at least two panel members for procurements valued at over $80 000 and that there were 110 panel members. The business case documenting the basis for the procurement method outlined the reasons the AEC should engage GRA Supply Chain to provide the services; it did not contain any reference to the options of open tendering or approaching multiple panel members. That is, it advocated for the AEC’s preferred approach and supplier without canvassing the merits of alternatives that would have involved greater competition.

2.21 The AEC has procured services from GRA Supply Chain on six occasions (being five contracts plus a substantial contract variation) for a total of $4.4 million between 2014 and 2017 without going to open tender or otherwise applying competitive pressure.

Future Senate scanning services

2.22 The AEC also did not conduct an open tender to procure Senate scanning services for future electoral events. The AEC documented in May 2017 that an open tender was ‘not considered a feasible option’ because the time involved ‘would likely lead to a solution not being in place prior to the 30 June 2018 [election ready target date]’.

2.23 Instead the AEC issued a request for quote to each of the four suppliers on an Australian Tax Office (ATO) panel for ‘capture and digital information services’—one of which was the ICT supplier used for the 2016 federal election and another was its parent company. Notwithstanding the AEC rejected the option of approaching the open market on the basis of the time involved, the AEC gave the suppliers 36 days to respond which is in excess of the 25 day minimum specified by the CPRs for an open tender.8

2.24 While the nature of some of the services for the ATO panel was similar to the Senate scanning, overall it is very ATO specific.9 It would not have been foreseeable to potential tenderers for the ATO’s panel in 2013 that the AEC would use it in 2017 for such a significant, bespoke purchase.

2.25 Local and international organisations that may have been interested in the opportunity to provide scanning services to the AEC were denied the opportunity to compete for the AEC work in 2017 as a result of not being a successful participant in the tender conducted in 2013 by the ATO for a predominately different purpose. These suppliers also did not have the opportunity to approach members of the ATO panel to form partnerships for the AEC work because the AEC’s request for quote process was kept confidential.

2.26 The prices sought by the ATO as part of its request for tender were reflected in various price tables in the Deed of Standing Offer. The AEC did not use this pricing when estimating the value of its procurement, assessing the prices offered for the Senate scanning services or in evaluating value for money.

2.27 At the time of writing this audit report the procurement was in contract negotiation phase and so it was not appropriate to include details of the quote/s received or of the AEC’s consideration of the quote/s. ANAO analysis of the records is that the risks to value for money associated with employing approaches that reduced competitive pressure in both the 2016 and the 2017 procurements were realised. The AEC records did not contain an adequate justification for not conducting an open tender and did not demonstrate that value for money will be obtained.

Future investments in modernisation

2.28 Funds permitting, the AEC is likely to undertake further procurements of significance in the short to medium term, including for ICT goods and services. The Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters recommended in June 2017 that:

… the Australian Government consider additional funding for the Australian Electoral Commission to invest in modernisation for future federal elections, including:

- Planning and expert advice on upgrading the AEC's information technology and business systems.

- Additional training for temporary staff who are likely to remain engaged over multiple elections.

- The deployment of additional electronic certified lists at polling stations.

- A trial to test the scanning and electronic counting of House of Representatives ballot papers.10

2.29 Given the AEC’s repeated preference to use panel arrangements for major procurements instead of open tenders, it should reflect on the findings of the Australian Government ICT Procurement Taskforce. The Taskforce consulted widely with ICT businesses and industry associations. In August 2017 it recommended reforms to ICT procurement panel arrangements, which were accepted by the Australian Government, and reported:

Industry stakeholders noted that agencies often try to avoid complex procurement rules by defaulting to panels rather than exploring the market for newer smaller suppliers. Industry believes that this leads to the same suppliers being selected for contracts and can consequently exclude newer businesses from government procurement. Additionally, to save time and administrative costs, many panels are not refreshed regularly by agencies. In some cases, panels have not been refreshed in more than five years, and about one third of the 40 identified ICT panels have only a single vendor. This means that newer suppliers and solutions are potentially locked out of government ICT procurement.11

Recommendation no.1

2.30 The Australian Electoral Commission employ openly competitive procurement processes so as to demonstrate value for money outcomes. In those circumstances when competitive procurement processes are not able to be employed, the Australian Electoral Commission document the reasons, appropriately benchmark the quoted fee and record how it was satisfied value for money was being obtained.

Entity response: Agreed with qualification.

2.31 The AEC is committed to continuous improvement in procurement and contract management processes. The AEC has already implemented measures to promote best practice procurement and contract management across the Agency, including establishing the AEC Procurement Network and strengthening the AEC’s procurement planning framework. The AEC will enhance guidance for AEC procurement officials on conducting and recording value for money assessments. In order to manage agency delivery risk, the AEC will continue to assess the different procurement options available.

Were financial approvals recorded?

Approval was recorded by the financial delegate for 20 of the 25 procurements examined. On six occasions, costs exceeded the approved amount prior to a new approval being sought.

2.32 The AEC’s Accountable Authority Instruction (AAI) on procurement, which is binding on officials in the entity, stated that ‘AEC Officials must submit a spending proposal to an appropriately authorised AEC Financial Delegate and receive their approval prior to entering into an arrangement for goods or services’. Reflecting the requirements of section 18 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rules), the AAI also stated that ‘AEC Financial Delegates must record the spending proposal approval in writing as soon as practical after giving it’.

2.33 Before each of the 17 transport contracts were signed, a spending proposal was submitted to a financial delegate and their approval recorded. Where services were predicted to exceed an approved amount, then a new approval was required in advance. On five occasions, transport costs were incurred prior to a new approval being sought and recorded.

2.34 Before each of the three Work Orders for the Senate scanning system were signed, a spending proposal was submitted to a financial delegate and their approval recorded. On no occasion did the delegate record the amount of money approved, although the amount requested for approval was included in the procurement records.

2.35 The Work Order for the system’s delivery phase was initially capped at $17.6 million but was subsequently increased to $19.2 million, primarily due to data-entry operators needing to work more night and weekend shifts than originally planned. The ICT supplier submitted regular financial reports to the AEC tracking actual and projected costs. Approval for the increase was obtained a week after actual costs exceeded the initial cap, notwithstanding that the supplier had requested in advance that approval be provided as it was evident that the cap would be exceeded.

2.36 A spending proposal was not submitted to a financial delegate before each of the five Project Change Requests were signed for a total of $271 775 and a written record of the approval was not made. This was non-compliant with the AEC’s AAI and with section 18 of the PGPA Rules.

Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs)

2.37 The AEC’s AAI on procurement was inadequate. It made reference to a small minority of the core requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), PGPA Rules and the CPRs. For example, there was no reference in the suite of AEC AAIs to the core requirements that approving officials must ensure that the commitment of money will be a proper use of public resources and must not act inconsistently with any relevant policies of the Australian Government.

2.38 The AEC advised the ANAO that it has since updated its AAIs based on the Department of Finance model AAIs and made them available to officials from November 2017.

Were costs and benefits adequately considered in procurement decision-making?

Adequate consideration was given to costs and benefits in the procurement of the transport services.

No consideration of financial cost was evident in the records of the AEC’s decision-making to implement the Senate scanning system. Timeliness, quality and risk were taken into account.

2.39 The CPRs state that an official must consider the relevant financial and non-financial costs and benefits of each submission when conducting a procurement.

Considerations when procuring transport services

2.40 When procuring transport services, the AEC gave due consideration to the relevant costs and benefits. This included the fitness for purpose of the proposals and the potential providers’ relevant experience and performance history. The focus was on finding a transport provider with the capacity and capability to fulfil the delivery schedule and to meet ad hoc demands. When multiple quotes were received, cost was an influential factor in choosing between suitable providers.

2.41 Accurate quoting of costs is dependent on accurate information about the freight route, volume and weight, and on the required urgency and security of the deliveries. Some AEC officers would have benefited from additional expertise in requesting and interpreting quotes for transport-specific services. For example, one of the AEC State Offices inadvertently sent out a request for quote that added up to around half the volume of ballot papers intended and then it miscalculated the quotes received. The deliveries ended up costing six times the amount initially calculated and approved.12

Considerations when procuring the Senate scanning system

2.42 The AEC obtained a quote from the ICT supplier prior to issuing the $7.6 million Work Order to design and develop a Senate scanning system to the point of it being election ready. The AEC records did not contain an analysis of the quoted cost.

2.43 The delivery date for an election-ready system was 10 June 2016. The Senate scanning system was also described as the semi-automated solution for entering voter preferences from ballot papers into the count. In the lead up to 10 June, the AEC separately designed and tested a manual data-entry solution for entering voter preferences.

2.44 On 13 June 2016 the AEC’s executive met to decide whether to implement the semi-automated solution or the manual data-entry solution. A report on the two solutions was provided to inform their considerations and it covered the non-financial costs and benefits in detail. The report’s key focal points were: ‘achievability; integrity of Ballot Papers and associated preference/vote data; and timeliness of Writ return’. The decision taken was to implement the semi-automated solution nationally.

2.45 The records contained no indication that financial costs were considered. The 31 page report did not contain a cost estimate for either solution or contain any other reference to cost. The minutes of the meeting did not refer to cost. The formal record of the decision taken by the AEC, and of the reasons for that decision, similarly did not refer to cost. At the time the options were considered and the decision was taken, the AEC did not have a current cost estimate for the semi-automated solution and so it was not in a position to properly consider costs.13

2.46 The ICT supplier was advised on 13 June 2016 that the AEC had decided to implement its semi-automated solution. The following day the AEC sought a cost estimate from the ICT supplier and on 15 June 2016 further explained that ‘We’re looking to verify what the ball-park total figures may be’. The ANAO considers that this sequencing of events placed the AEC in a vulnerable negotiating position. The cost estimate submitted by the ICT supplier predominantly drew on previously proposed rates.

2.47 While it is recognised that timeliness, quality and risk were the priority factors, the lack of evidence that the AEC factored cost into its procurement decision-making is not consistent with an accountable authority’s duty to promote the proper use and management of the public resources for which it is responsible (section 15 of the PGPA Act).

Was documentation maintained on how value for money was considered and achieved?

The documentation on the transport procurements outlined how value for money was considered but did not always demonstrate that value for money would be achieved. The documentation on the Senate scanning system procurement indicates that inadequate consideration was given to assessing value for money and did not demonstrate that it was achieved.

2.48 The CPRs stated that officials must maintain a level of documentation commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of each procurement. The documentation should provide accurate and concise information on how value for money was considered and achieved. It must be retained in accordance with the Archives Act 1983.

2.49 The AEC’s internal procedures required that relevant records of procurement processes be filed, including on value for money and quote/tender evaluations. Procurements over $10 000 were also to be entered into the AEC’s Procurement and Contract Management Register. The register contains an ‘Evaluation and Value for Money Assessment’ field, described to users as ‘a free text field where you will need to explain your reasons for selecting the preferred supplier and how value for money has been determined’. Procurements at or above $80 000 were to have a quote/tender evaluation plan that set out, amongst other things, the basis for assessing best overall value for money.

Procurement of transport services

2.50 The records of the procurement of transport services outlined how quotes were evaluated and value for money assessed by the State Offices. The records were commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurements. Details of all 17 procurements were in the AEC’s register, with separate evaluation reports or file notes provided for 14 of these.

2.51 The records did not always demonstrate that value for money would be achieved. On nine occasions the recorded reasons for accepting a quote as value for money relied heavily on it being from the sole provider and/or from a panel member. While such reasons do not demonstrate a sufficient assessment of value for money, the evaluation records read as a whole suggest that AEC officers were at times challenged and frustrated rather than dismissive of their obligation to demonstrate value for money. As one recorded, ‘It is difficult to assess whether the estimated costs provided in [the] response would be comparable with other providers, as no other panel member provided a response’.

Consideration of value for money when establishing the transport panel

2.52 The records relating to seven of the ten contracts entered into with panel providers indicated that the AEC relied upon the providers’ rates having already been assessed as value for money when the panel was established. That assessment was not robust. For example, the tender evaluation report stated ‘If a Tenderer provided the sole submission for a Service in a Jurisdiction, the Team assumed, on advice of the Financial Management section, that the price was commercially competitive’.

2.53 Tenderers had been requested to input pricing information into a template. This template was flawed and did not align with industry practice. For example, it did not include a separation between secure freight costs and non-secure freight costs. The template did not cater for the provision of the typically cheaper ‘back load’ rates, instead seeking pricing for deliveries in one direction only.

2.54 The flaws in the template became evident when the AEC attempted to evaluate pricing across tenders. The evaluation team noted that ‘each provider had different pricing structures’ and that, ‘short of the AEC going back and stipulating the pricing structures, [AEC’s] finance advises that they each represent value for money in different scenarios.’

2.55 There was no advice to users of the resulting transport panel as to which providers represented value for money in which scenarios. For example, it was not communicated to users that the tender evaluation had concluded that one of the panel members ‘did not offer value for money for urgent and small courier deliveries’. This provider was then engaged for small courier deliveries, such as the delivery of a single item to a location nine minutes away for $1001.

Need for additional logistics expertise

2.56 The transport panel arrangement was established and managed centrally by a generalist procurement team. Prior to its establishment, each State Office provided detailed input on their transport needs and challenges. It is evident from that input that the State Offices hold a vast amount of jurisdiction-specific knowledge and that some Divisions within jurisdictions have unique requirements. But this input became diluted in the final product. The panel achieved the aim of national consistency of contractual terms and conditions but this did not need to come at the cost of State-specific requirements. The final product also did not reflect transport industry standard practices sufficiently. The tender process was well managed and the procurement team provided the AEC sound advice on procedures and on the drafting and management of contracts. The gap was specialist logistics expertise and transport industry knowledge.

2.57 One of the larger States addressed this gap by arranging for a staff member from their contracted transport supplier to be embedded in the AEC State Office during the election period. The staff member provided two key services: logistics advice, planning services and related information; and the ability to quickly solve identified issues and initiate a rapid response from the provider’s transport network when issues arose. This arrangement has been described by the AEC as a ‘crucial element’ and ‘of significant benefit to the successful service delivery’. The cost of embedding this staff member equated to less than one per cent of the value of that State’s contracts with the provider.

2.58 From ANAO examination of a sample of the invoices paid by the AEC, it appears that the potential for improving value for money would likely offset the cost of engaging additional expertise in future elections. Examples of where expertise on transport pricing and scheduling may have been beneficial include:

- the transport of ballot papers (six consignments) from an airport to a location 20 minutes away cost $15 278;

- the transport of ballot papers from a capital city to ten locations within the State cost $351 119 (the subsequent return of ballot papers from those ten locations to the capital city by the AEC’s records-storage contractor cost $7830);

- the transport of one carton of unspecified materials from a capital city to a location four and a half hours away cost $3236 (the subsequent transport of 45 cartons of ballot papers back to the capital city by the records-storage contractor cost $1513, which was 47 per cent of the cost for 45 times the volume); and

- five ‘client changed mind’ charges totalling $1901, nine ‘unable to access’ charges totalling $3725 and four ‘delayed uplift requested’ charges totalling $2041 on one invoice.

Recommendation no.2

2.59 The Australian Electoral Commission revise its approach to procuring election-related transport services so as to improve value for money and to provide more efficient access to transport services that meet needs (which can vary between and within States). The approach should be underpinned by logistics expertise and transport industry knowledge.

Entity response: Agreed.

2.60 Following the 2016 Federal Election, the AEC revised its approach to procuring election-related logistics services. The AEC has conducted a national procurement for freight and logistics services which has been informed by market research and industry experts. It is anticipated that this national procurement approach will deliver increased value for money outcomes for the AEC and meet the AEC’s business requirements. To support this approach the AEC has increased internal capability through the establishment of a Supply Chain team, this team will be responsible for implementing the new contracting arrangements and ensuring efficient access to logistics services.

Procurement of the Senate scanning system

2.61 It was not apparent from AEC records that value for money was adequately considered or achieved in the procurement of the Senate scanning system. The extent of the value for money assessment and associated record-keeping was not commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurements. Six of the eight agreements exceeded $10 000 but only the three Work Orders appeared in the AEC’s Procurement and Contract Management Register. Three of the eight agreements with the ICT supplier exceeded $80 000 but no quote evaluation plan or report was produced.

System design phase

2.62 The record of the value for money assessment of the $7.6 million to design and develop the Senate scanning system was as follows:

Value for money has been established by comparison with our alternative manual entry, expected to cost around $18–30 million nationally, and by the lower risk using a scanning provider we have an existing relationship and established infrastructure and previously evaluated value for money.

2.63 The AEC’s reference to the ‘previously evaluated value for money’ (above) was of limited relevance to assessing the value for money of the Senate scanning services. The costings were not based on the fee schedule established through the open tender process that had been previously evaluated.

2.64 The full cost of the manual-entry solution was not a useful benchmark for determining whether the design cost of the semi-automated solution represented value for money. At that time the AEC did not know which solution it would choose or whether the semi-automated solution would work. Further, the broadness of the estimate given for the manual-entry solution—‘around $18-30 million’—indicates that it was not a robust benchmark.

2.65 The AEC needed to assess the value of spending $7.6 million designing a system that it may not implement. The AEC did not own the intellectual or physical property that would result from this expenditure. The price included a $4.1 million contribution to ‘project infrastructure and equipment’ and the AEC did not include an asset clause in the contract nor otherwise put in place a mechanism for ensuring it would benefit from this expenditure in any future purchases of data capture services from this supplier.

System delivery phase

2.66 The record of the AEC’s value for money assessment of the $17.6 million initially approved for the delivery phase was as follows:

The provider is contracted to the AEC to provide scanning and data capture services and has implemented a solution to process Senate ballot papers … that has been tested and accepted by the AEC. In addition, [the provider has] met the AEC’s requirements in proving readiness to deliver the solution for the 2016 Federal Election, and in accordance with the AEC’s integrity and security requirements.

In comparison with alternative solutions (specifically an expansion of the previously used EasyCount manual data entry solution), the … scanning solution provides the best value for money in that it best meets requirements and presents lower cost and risk.

2.67 Again value for money was determined by comparison with the AEC’s manual-entry solution as a whole.

2.68 Half of the cost to deliver the Senate scanning system was attributed to ‘manual validation/data entry’. The AEC did not benchmark the hourly rates proposed for the data entry operators to those recently offered to the AEC by a labour hire firm so as to be assured it was obtaining value for money. The hourly rates offered the AEC by the labour hire firm were considerably lower.14 The AEC advised the ANAO that ‘Time pressures in delivery of the project did not permit for benchmarking of rates to take place’.

Procurement of future Senate scanning services

2.69 In its 2017 procurement of Senate scanning services for future electoral events, the AEC did not benchmark the proposed rates against those offered by other suppliers for similar services notwithstanding that time permitted. Value for money was determined by comparison with the estimated total cost of alternative methods, being manual-entry or the establishment of a scanning centre within the AEC.

Record keeping

2.70 The record keeping issues observed during the course of this audit extended beyond the inadequate documentation of value for money. Record keeping for the procurement and management of the 2016 Senate scanning services was not consistent with the requirements of the CPRs or the Archives Act 1983.

2.71 The AEC had a print-to-paper records management system. Yet very few records were maintained on a paper-based registry file. Nor were the electronic records saved in a single location. They were distributed throughout shared drives, a GovDex site, the Procurement and Contract Management Register, a mail register and in personal emails. Such systems do not contain appropriate records management functionality. It took considerable resources to locate the relevant records for this audit. To fulfil an ANAO request for some of the core procurement documents, the AEC asked its contracted ICT supplier for them.

2.72 To see if the above shortcomings were widespread, the ANAO examined the records of four other procurements undertaken by the AEC’s National Office for election-related services. The issues identified are outlined below:

- $53 403 procurement: delegate approval poorly documented and for less than the contract value; contract was issued after the services were provided and did not detail the services; non-compliant with the reporting requirements;

- $154 789 procurement: no contract was issued by the AEC to the provider; delegate’s verbal approval not documented; quotes and new approvals not obtained prior to requesting additional deliveries; non-compliant with the reporting requirements;

- $1.2 million procurement: contract issued after $0.5 million in services were provided; non-compliant with the reporting requirements; and

- $1.4 million procurement: no reference to value for money; contract not in the AEC’s register; non-compliant with the reporting requirements.

During 2017 the AEC has been procuring an electronic document and records management system to replace its paper-based system. The move is consistent with the Australian Government’s Digital Transition Policy of 2011. It will not solve the AEC’s record-keeping shortcomings unless it is accompanied by a change in culture.

3. Addressing risks to the security and integrity of ballot papers

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether risks to the security and integrity of ballot papers in the custody of transport and Senate scanning system suppliers were appropriately addressed by the AEC.

Conclusion

Most contracts with suppliers contained comprehensive security requirements that appropriately reflected the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy. The AEC was generally satisfied that the requirements were implemented.

Did the contracts with transport providers contain appropriate security requirements for ballot papers?

The ten contracts with suppliers procured from the AEC’s transport panel contained security requirements that appropriately reflected the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy. The seven contracts with suppliers procured from outside the transport panel did not explicitly reflect the AEC requirement that ballot papers not be left unattended. The AEC was generally satisfied that the requirements were implemented but with some room for improved adherence.

3.1 The risk of loss or misplacement of ballot papers was realised in the 2013 federal election in Western Australia, and had also been realised in earlier elections (although the number of ballot papers that had gone missing had not previously been large enough to affect the result). Risks to the physical security of ballot papers have also been identified by independent inquiries. ANAO audit reports in 2010 and 2014 made recommendations aimed at improving the security arrangements for the storage and transport of ballot papers. The 2013 inquiry into the circumstances of 1370 missing Western Australia ballot papers (the ‘Keelty report’) made 13 recommendations around ballot paper handling, which included the transport and security of completed ballot papers.

3.2 In the lead up to the 2016 election, the AEC established ballot paper principles that reflected a recommendation in the Keelty report to adopt a doctrine emphasising the security and sanctity of ballot papers. The principles were that:

1. All ballot papers remain ‘live’ from printing through to statutorily authorised destruction.

2. The security, integrity and accountability of ballot papers must be preserved at all times—including transit and storage by the AEC, contractors or other third parties.

3.3 The AEC also released a revised ballot paper handling policy in May 2016 with the aim to ‘know, at all times, that all ballot papers in its control are safe, secure and accounted for’.

Contracts for transport services

3.4 When the AEC gives a third-party custody of ballot papers it is important that AEC handling requirements are clearly communicated and are enforced under the contract. This is to help ensure the security of ballot papers (that they are not lost or stolen) and the integrity of ballot papers (that they are not tampered with).

3.5 An ANAO audit of the 2013 election had identified that seven of the eight AEC transport contracts examined did not include appropriate provisions promoting secure handling and movement of election material. ANAO analysis of transport contracts entered into for the 2016 federal election identified an improved approach.

3.6 For the 2016 federal election, the ten contracts with the three providers engaged under the transport panel arrangement included security requirements consistent with the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy.

3.7 The contracts with the seven non-panel suppliers contained fewer security measures. Of note was that all seven contracts had provisions that reflected AEC policy for enclosed, secure vehicles and a ‘track and trace’ facility. These contracts should also have explicitly set out the AEC’s requirement that ballot papers not be left unattended at any time.

Tracking of ballot papers in transit

3.8 The AEC intended to use the transport providers’ ‘track and trace’ facilities to help monitor the movement of election materials down to box or parcel level. The AEC’s ballot paper handling policy specified tracking to parcel level but the wording in the contracts did not make this clear. Some transport providers did not have a facility that complied with AEC expectations, including two of the four suppliers on its transport panel. AEC’s post-election observations identified the need for clarification about the facility to ensure consistency with AEC policy and security requirements. Feedback to the AEC from one of the providers included, ‘Track and trace to parcel level isn’t really feasible, per pallet consignment is okay’.

3.9 The AEC had an online portal called CeDaRS to track the movement of Senate ballot papers between AEC-operated premises and the eight Senate scanning centres. The AEC entered the delivery details and the consignment number issued by the transport provider into its CeDaRS system when a container was ready for dispatch. AEC officials at the Senate scanning centres then updated the record in CeDaRS on receipt of each transport container and resolved any apparent discrepancies. This process was additional to the ICT supplier’s tracking system, which is outlined at paragraph 3.17 below.

Implementation of the security requirements

3.10 The AEC conducted a post-election survey of contract managers. It included the following question in respect of transport panel providers: ‘Were you satisfied that the Supplier met the AEC’s security requirements in delivering the goods/services during the 2016 Federal Election?’ Eight of the twelve responses received stated ‘Yes’. Of the four that indicated they were dissatisfied, the reasons provided did not reference security incidents involving ballot papers. Other AEC records supported that contract managers were generally satisfied with some room for improving adherence to security requirements by transport providers and their sub-contractors.

Did the contracts with the ICT supplier contain appropriate security requirements for ballot papers?

The contracts for the Senate scanning services contained security requirements that appropriately reflected the AEC’s ballot paper handling policy. The AEC verified that the requirements had been implemented.

3.11 The introduction of a Senate scanning system was complex and created significant logistical and security challenges. In total, 14.4 million Senate ballot papers were sent to eight centres across Australia for scanning and verification. In New South Wales alone, 4.5 million ballot papers were brought to one facility—an exercise described by the AEC as the ‘largest collection of federal ballot papers in Australia’s history’.15

3.12 After polling day, completed Senate ballot papers were progressively dispatched to a scanning centre in the capital city of each state and territory. More than 34 000 transport containers were dispatched. Custody of the Senate ballot papers was transferred to the ICT supplier at the time each transport container was received at each scanning centre.

Contract for Senate scanning system

3.13 The eight Senate scanning centres were owned or leased by the ICT supplier. The AEC contracts specified a number of physical and operational controls to address the risk of loss, damage or unauthorised access to ballot papers at scanning centres. Physical controls included alarm systems, 24 hour on-site security guard patrols and closed-circuit television coverage. Procedural controls included that transport containers could only be opened, and ballot papers could only be scanned, in the presence of at least two personnel to help ensure they were not tampered with. The provisions appropriately reflected AEC policy for ballot paper handling and storage, including the requirement for ‘ballot paper secure zones’.

3.14 All scanning centres were required to have segregated, secure work and storage zones that were only accessible to authorised personnel. Transport containers could only be opened in secure work zones. Site set-up and procedures were consistent with the Keelty report recommendations that the AEC:

- ‘institutes a concept of ‘ballot secure zones’ at all premises where ‘live’ ballot papers are handled or stored (including fresh scrutiny centres and non-AEC premises)’; and

- ‘ensures all ballot secure zones are cleared before the arrival of ‘live’ ballot papers, and that they remain secured and ‘sterile’ at all times when ballots are present’.16

Implementation of security requirements

3.15 The AEC undertook site inspections prior to scanning system operation to assess compliance. ANAO analysis of AEC records indicates that the inspections were comprehensive and that the security controls were assessed as having met contractual requirements. During system operation, AEC officials on-site helped ensure adherence to security procedures. A post-implementation review, jointly undertaken by the AEC and its ICT supplier, reported positively on ballot paper handling and physical security at the scanning centres and reported that security staff had enforced requirements.

Tracking of ballot papers at scanning centres

3.16 An internal report of June 2016 to the AEC executive recommending the semi-automated system over the manual system stated that ‘integrity is improved for [a semi-automated system] as on every [scanning centre] site the AEC will always know where a ballot paper is’. The recommendation to proceed with the system was based in part on the implementation of ‘a continual and trackable chain of custody for the ballot papers’.

3.17 The contract required that the ICT supplier track all ballot papers as they progressed through the scanning centre. This requirement was met. If a particular ballot paper needed to be retrieved, then the ICT supplier was able to locate it. The key controls implemented were as follows:

- the AEC bundled the ballot papers into batches of up to 50 papers and attached a coversheet with a unique barcode to each batch;

- the AEC placed up to ten batches into each transport container, sealed it and attached a unique barcode. A spare copy of the transport container label was included inside;

- the ICT supplier scanned the barcode on each transport container as it was received at the scanning centre. The location of each transport container on-site was tracked using the ICT supplier’s digital tracking software;

- the ICT supplier scanned the coversheet of each batch at the time the ballot papers in that batch were scanned;

- each ballot paper was assigned a unique identifier in the system at the time it was scanned (legislation restricts placing an identifier on the ballot paper itself); and

- the identifier of the ballot paper was linked to the identifier of the batch, which was linked to the identifier of the transport container, which was tracked throughout.

Figure 3.1: Tracking and storage of ballot papers at Senate scanning centres

Source: AEC records.

Was assurance of the political neutrality of suppliers and suppliers’ personnel obtained?

The AEC checked the political activity of suppliers during the procurement process and included political neutrality provisions in each contract. The AEC did not obtain assurance of the political neutrality of personnel transporting ballot papers. The AEC did obtain assurance of the political neutrality of supplier personnel involved in the Senate scanning system.

3.18 Obtaining assurance as to the political neutrality of suppliers and of supplier personnel helps address actual or perceived risks to the security and integrity of the ballot papers in their custody. Further, the AEC operates in a politically sensitive environment. Any employee, contractor or supplier to the AEC who is, and is seen to be, active in political affairs and intends to publicly carry on that activity may compromise the strict political neutrality of the AEC.

Political neutrality of suppliers

3.19 The AEC procurement procedures set out the process to be used to gain assurance of the political neutrality of potential suppliers.17 Consistent with these procedures, the political activity of the transport providers and the Senate scanning supplier over the preceding three year period was checked by the AEC using the funding and disclosure receipt information it holds. The results were presented to the financial delegates for consideration and, in each case, stated that no political activities had been identified.

3.20 The AEC procurement procedures also state that, ‘During the contracting process, AEC Officials must ensure that the supplier or contractor signs and returns a Deed Poll, which incorporates the AEC’s political neutrality requirements … Signed Deed Polls must be attached to the relevant Spending Proposal together with the signed contract’. A Deed Poll signed by the scanning supplier was attached to the spending proposal in the AEC’s Procurement and Contract Management Register as required.

3.21 There were no Deed Polls signed by transport providers identified on the AEC’s register. The AEC provided the ANAO a copy of a Deed Poll signed in 2014 by the off-panel provider used in Western Australia and it contained assurances as to political neutrality. The AEC also provided copies of ‘Tenderer Declaration’ Deed Polls signed by each of the four panel members at the time they submitted their tenders in 2015. These Deeds included a sub-heading ‘Political neutrality and Conflict of Interest’ but did not otherwise contain the term ‘political neutrality’.

3.22 The terms of the contracts entered into with the scanning and transport suppliers reflected the AEC’s political neutrality policy. For example, in addition to other relevant clauses, the contracts with transport panel providers stated that ‘the Service Provider must: (a) respect the strict political neutrality of the AEC; and (b) not associate the AEC in any way with any political activity that they undertake’.

Political neutrality of supplier personnel

3.23 The Keelty report found that ‘despite the existence of a relevant provision in the contract, the WA office did not ask the contractor to enquire as to the political neutrality of all persons under its control who were responsible for the transport of components (ballots, parcels, boxes and pallets).’ The report recommended that ‘the AEC should continue to assure itself, to the best of its ability, of the political neutrality of all persons, including subcontractors, having contact with a ballot paper (other than electors at the time of voting)’.18 The AEC agreed to the recommendation and advised Parliament that implementation was completed for the 2016 election.19

3.24 The relevant provisions in the contracts for scanning and transport services for the 2016 federal election included that ‘Where the Service Provider supplies Service Provider Personnel to provide any of the Services, the AEC in its absolute discretion may: (a) require the Service Provider to ensure that those Service Provider Personnel sign a declaration of political neutrality substantially in the form set out in Schedule 7…’

3.25 Specified personnel of the Senate scanning supplier signed declarations of political neutrality.

3.26 AEC policy was not to require that personnel transporting ballot papers sign a declaration of political neutrality. Accordingly, the AEC did not require this for any of the 17 transport contracts examined. The AEC advised the ANAO that:

The AEC relied on the panel suppliers entering into these Deeds of Standing Offer to provide assurances around political neutrality, as opposed to seeking individual declarations from all service provider personnel. Given the nature of the services (i.e. changing rosters, volume etc) seeking political neutrality assurances from the panel supplier was considered a practical and efficient approach.

3.27 Prior to the 2016 services commencing, the off-panel provider used in Western Australia requested a political neutrality form for its drivers to sign. The AEC gave this supplier a standard form entitled Acknowledgement and declaration of key obligations relating to the Ballot Paper Principles - labour hire and contracted staff. This form did not contain any reference to political neutrality. It did contain other important information about ballot paper handling and security, which the provider communicated to its drivers.

4. Addressing risks to the security and integrity of ballot paper data

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether risks to the security and integrity of the ballot paper data generated by the Senate scanning system were appropriately managed by the AEC.

Conclusion

The AEC addressed risks to the security and integrity of ballot paper data through the design and testing of the Senate scanning system. The AEC accepted IT security risk above its usual tolerance. Insufficient attention was paid to ensuring the AEC could identify whether the system had been compromised.

Areas for improvement

The AEC needs to increase confidence in the integrity of the ballot paper data it uses to generate the Senate election result through improved IT security controls and monitoring, consistent with the Australian Government IT security framework.

What ballot paper data was generated by the system?

The primary data generated by the Senate scanning system was XML files containing the voter preferences and whether the vote was formal or informal. A cryptographic digital signature on each XML file protected the data from modification. A secondary output was a digital image of each ballot paper.

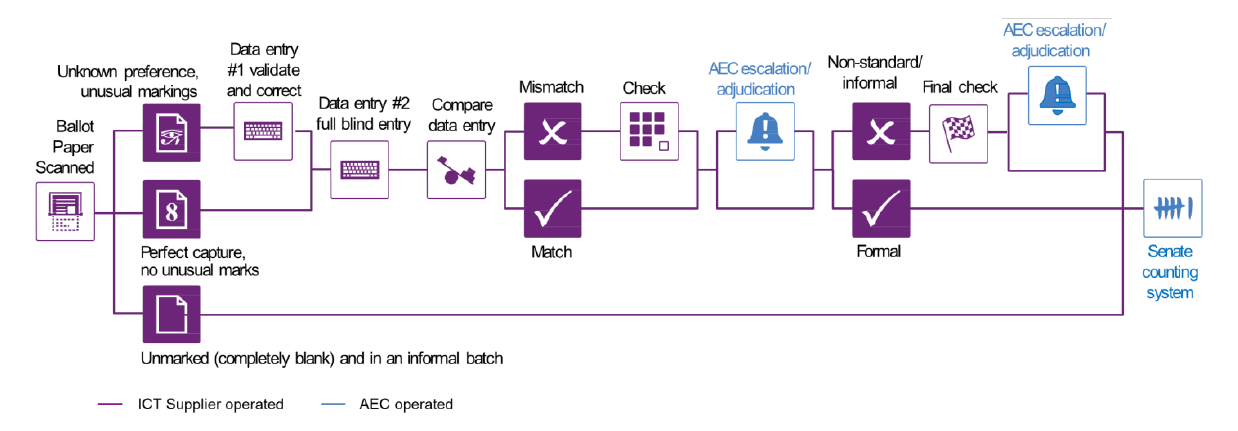

4.1 The Senate scanning system was a semi-automated process introduced to capture voter preferences for entry into the AEC’s count system (known as Easycount). As per the simplified diagram at Figure 4.1, the following processes were undertaken by ICT supplier staff:

- ballot papers were scanned to produce a digital image and the voter preferences captured using optical character recognition technology;

- any ballot paper with unknown preferences or unusual markings was sent to a human operator for verification (‘data entry 1’);

- all ballot papers were sent to a human operator for full blind entry of every preference (‘data entry 2’). That is, the operator could not see the results of the optical character recognition or of data entry 1;

- any mismatches in the voter preferences recorded during the above stages, unreadable preferences or other concerns were routed to a senior staff member to either resolve or to escalate to an AEC official; and

- ballot papers identified as having informal preferences above or below the line, or having a sequence breakdown, were sent to a senior staff member for rechecking.

4.2 AEC officials scrutinised ballot papers that were potentially informal due to being voter identified, form altered or not authentic, as well as any ballot paper escalated to them by the ICT supplier.

4.3 The exceptions to the above process were completely blank ballot papers that AEC officials had placed in batches marked ‘informal’ or a placeholder ballot paper that had been routed to the retrievals queue. ‘Placeholders’ were used when a ballot paper could not be scanned (due to damage, for example) and so an AEC official needed to retrieve the hardcopy and manually key in the voter’s preferences.

Figure 4.1: Simplified diagram of Senate scanning system

Source: ANAO modification of AEC diagram.