Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the VET FEE-HELP Scheme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and administration of the VET FEE-HELP scheme.

Summary and key learnings

Background

1. The VET FEE-HELP (VFH) scheme was a component of the Australian Government’s Higher Education Loan Program. Under the program, eligible students could access Government income contingent loans, which removed up-front cost barriers to tertiary education and training. VFH loans were incurred by the student and the course fees paid directly to the education provider. Students are required to repay the loan(s) once their income reaches a threshold.

2. The VFH scheme was established in June 2008, primarily1 to increase participation in vocational education and training (VET).2 Initially designed to support pathways to higher education, the scheme was subsequently expanded by allowing all eligible students to access a VFH loan, and abolishing the requirement for a pathway to higher education. These changes resulted in significant growth in the uptake of the expanded VFH scheme, particularly from 2012 to 2015, but legislative and policy changes implemented from 1 April 2015 substantially reversed the growth. At its peak in 2015, the total value of VFH loans was $2.9 billion (up from $25.6 million in 2009). The value of VFH loans not expected to be repaid is significant. As at 30 June 2016, the Australian Government Actuary estimated that $1.2 billion in loans issued inappropriately by VFH providers in 2014 and 2015 would not be recovered. The Actuary also estimated that a further $1.0 billion in VFH loans would not be repaid, largely relating to loan recipients not expected to meet the income repayment threshold for new debts raised in 2015–16.

3. The VFH scheme was administered by the Department of Education and Training. The Australian Skills Quality Authority manages risks to the quality of VET outcomes for students. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, (and state and territory counterpart Australian Consumer Law regulators), has economy-wide responsibilities in relation to consumer protection, and can address misleading or unconscionable conduct of VFH providers.

4. In October 2016, the Minister for Education and Training announced that the VFH scheme would cease on 31 December 2016, and a new program, VET Student Loans, would commence from 1 January 2017. The Minister stated that the new program ‘would return integrity to the vocational education sector and deliver a win-win for students and taxpayers through a range of protections’.3 Legislation supporting the new scheme was passed by Parliament on 1 December 2016.

5. As the VFH scheme is scheduled to cease shortly after this audit report is tabled, the report focuses on the lessons learned from the administration of the scheme. The aim is to inform debate about the proposed replacement VET Student Loans program and support other Commonwealth entities in designing and implementing policies and programs.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and administration of the VET FEE-HELP scheme. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the Australian National Audit Office adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- the design and implementation of the VFH scheme supported the achievement of the scheme’s objectives; and

- administrative arrangements safeguarded the operation of the VFH scheme, including by supporting students to understand their rights and obligations.

Conclusion

7. The VFH scheme was not effectively designed or administered. Poor design and a lack of monitoring and control led to costs blowing out even though participation forecasts were not achieved and insufficient protection was provided to vulnerable students from some unscrupulous private training organisations.

8. The design of the expanded VFH scheme in 2012 was weighted heavily towards supporting growth in the VET sector, but an appropriate quality and accountability framework addressing identified risks was not put in place. As the responsible department, Education did not establish processes to ensure that all objectives, risks and consequences were managed in implementing the expanded scheme. In effect, the department’s focus on increasing participation overrode integrity and accountability considerations that would have been expected given the inherent risks. The department inadequately considered the implications of the changed incentives facing providers and students in the expanded scheme and its role in ensuring effective regulation in conjunction with other regulators—principally the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. There was also a lack of data analytics capability in Education and little internal management reporting or analysis of the VFH scheme to identify emerging problems. The department did not develop measures to assess broader objectives of the scheme (beyond growth) including those related to value and quality in the VET sector. In redesigning the VFH scheme, insufficient regard was given to relevant experiences in other jurisdictions, particularly Victoria, and the risks identified in a Regulation Impact Statement.

9. The administration of the VFH scheme did not safeguard its operation, and did not support the achievement of objectives relating to integrity, quality, value and sustainability. Similar to the scheme’s design and implementation failures, there were weaknesses in Education’s administrative processes for: approving VFH providers; developing and undertaking risk, fraud and compliance activities; controlling payments to providers; making information readily available to students about their rights and obligations under the VFH scheme; and managing and resolving student complaints. While improvements were made to many of these processes in 2016, the initiatives were in place for a relatively short period of time prior to the cessation of the VFH scheme from 31 December 2016.

Supporting findings

Design and implementation of the VET FEE-HELP scheme

10. Strategic and operational risks were identified in the expansion of the VFH scheme in 2012, but were not adequately addressed in the legislative and policy design that significantly changed the requirements for participation in the scheme. While concerns about the application of legislative arrangements designed for higher education were identified in 2012, the expanded VFH scheme did not include adequate controls to manage risks specific to vocational education. Weaknesses included insufficient safeguards for students from misleading or deceptive conduct, and inadequate monitoring, investigation and payment controls for poor or non-compliant providers. The recommendation in a Regulation Impact Statement for a staged approach over three years did not occur, and the expanded scheme did not incorporate adequate controls over the risks identified in the statement.

11. Arrangements were not in place between Education and the regulation agencies to effectively monitor and address risks to the implementation of the expanded VFH scheme, particularly in relation to integrity, quality and sustainability. There was poor engagement by Education with the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to exchange information and intelligence about low quality or unscrupulous VFH providers. Within Education, until 2016 there was little analysis or internal management reporting of the VFH scheme to identify emerging problems.

12. The VFH scheme did not achieve many of its stated objectives, and is to be replaced by the VET Student Loans program from 1 January 2017. While achieving increased participation in vocational education and training as intended following the expansion in 2012, Education did not provide evidence that the scheme achieved objectives relating to quality, value and sustainability of the VET sector, consumer protections, or support for the productivity and skills agenda. In analysing the performance of the scheme, Education did not develop measures to assess broader objectives of the scheme, including those related to value and quality in the VET sector, and did not revise the key objectives and outcomes following expansion of the scheme.

Administration of the VET FEE-HELP scheme

13. There was no evidence of adequate consideration of risk in the development of the approval process for registered training organisations to achieve VFH provider status, or that the process effectively safeguarded the VFH scheme at this early stage of provider engagement. Education did not analyse the results of the process to understand the behaviour and motivation of organisations seeking access to the VFH loan scheme, and how best to strengthen the approval process.

14. VFH providers were not effectively monitored and regulated by Education. The department acknowledges that there was not an effective compliance framework for the scheme, noting the serious limitations in its compliance powers under the VFH legislation. In effect, there was very limited and reactive compliance activity, including of the expanded VFH scheme from 2012. Education did not act promptly at that time to clarify the roles and regulatory powers of the department and other regulators, to ensure a sound regulatory framework for VFH. From mid-2015, compliance and regulatory activities increased in response to the identified risks. Education initiated several major compliance audits, began the development of a new risk-based compliance framework, and worked with Australian Consumer Law regulators in taking a number of established VFH providers to court under the prevailing VFH legislation.

15. Payments to approved VFH providers were calculated on data submitted by VFH providers and not effectively controlled. Education had little visibility of the students entering into a loan arrangement through their VFH providers; and relied on self-reporting by providers. There were also weaknesses in departmental guidance provided to staff processing the payments, and in evidence supporting delegate approval of the payments.

16. Information provided by Education was not easily accessible to students to help them understand their rights and obligations under the VFH scheme, including access to information regarding the cost, quality and reputation of VFH providers. The department had a limited level of assurance that students understood (through accessing the available information or being properly informed by the VFH provider) that they had entered into a VFH loan arrangement. Outreach initiatives by Australian Consumer Law regulators, and additional information provided by Education in early 2015, sought to warn students about inappropriate marketing practices by VFH providers. The department launched its main campaign, savvy student, in September 2015, and could have acted sooner.

17. Until mid-2015, the department had limited focus on managing and resolving student complaints about the VFH scheme. Until September 2016, the department’s websites had not provided clear information on the types of complaints that it would investigate, and encouraged students to contact other agencies without outlining the types of complaints these other agencies were able to investigate. Improvements from mid-2016 to Education’s complaints handling mechanisms included three additional staff dealing specifically with VFH complaints and the development of a new Feedback and Complaints System that would enable the department to view complaints that students had submitted directly to their VFH providers. Information about how to lodge a complaint is readily available on the VET regulator websites, and through the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s website. Education had not effectively collected and analysed VFH complaints data, and the information held on complaints had been of limited use in monitoring the VFH scheme.

Key learnings

18. The VFH experience again4 underlines how critical sound program design and implementation practices are to achieving policy outcomes. The audit identified key learnings of relevance to the introduction of the proposed VET Student Loans program and to other Commonwealth entities responsible for the design or implementation of Government programs.

19. Key learnings include the importance of:

- thoughtfully considering the critical differences between a new program and any existing program on which it had been modelled, including how different incentive structures for key participants (including financial incentives) will create risks to the achievement of program objectives. Similarly, in revising an ongoing program, recognising how substantially altered incentive structures will change behaviours and risks;

- learning from comparable experiences in other agencies or jurisdictions, and carefully considering supporting program documents, such as regulation impact statements, when designing and implementing programs;

- integrating risk management principles and processes into the design, implementation and administration of a program, to effectively manage risks to the achievement of the objectives and outcomes of programs;

- placing emphasis on achieving all program objectives and outcomes, rather than excessively focussing on the prime objective (such as participation in a program). Integrity, quality and sustainability are often intrinsically linked to the primary objective and need to be achieved;

- developing key performance indicators to measure the success of the program against all key objectives and outcomes. This will help focus attention on achieving all objectives and prevent entities from overlooking key risks. Evaluating programs with a focus on understanding their impact will indicate whether the underlying policy approach is an effective intervention;

- establishing a strong data analytics capability and management reporting processes to identify emerging threats and promote understanding and visibility of the outcomes of the scheme. In demand driven programs, modelling and sensitivity analysis should be undertaken to forecast demand, and monitoring both uptake and cost can provide early warnings of potential threats to the effective and efficient implementation of programs;

- clarifying roles and responsibilities and introducing effective mechanisms for information sharing and engagement with all entities with a role in design or implementation. Where other regulators have a role, the key implementation agency should consult with those regulators to analyse the strength of the regulatory environment and address any notable shortcomings, including by drawing these to the attention of the Government as early as possible; and

- ensuring fraud, risk and compliance arrangements are operational from the commencement of a program, and reflect program risks and requirements.

Summary of entity responses

20. The summary responses to the report of the Department of Education and Training, the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Taxation Office are provided below, while their full responses are at Appendix 1.

Department of Education and Training response

The Department of Education and Training (the department) acknowledges the work conducted by the ANAO and thanks the review team for the collaborative way in which the audit was conducted.

While the department notes the proposed report does not make any specific recommendations, the ANAO has identified significant areas of concern. The department has acted to address and strengthen a number of administrative processes and practices in these areas and will continue to do so through the new VET Student Loans program.

Since 2015 the department has strengthened its administration of the VET income contingent loan scheme by increasing available resources in this work area; providing compliance training to staff; strengthening record keeping practices; recording student and provider enquiries and complaints and the actions taken to resolve these; instigated improved payment processes; increased the availability of course costs and broader information for students; increased data sharing with regulators (ASQA and ACCC) and improved monitoring and investigation of compliance issues.

On 5 October 2016, Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham, Minister for Education and Training, announced the commencement of VET Student Loans program from 1 January 2017. The Minister also announced that the VET FEE−HELP scheme will cease on 31 December 2016. These changes are subject to the passage of the VET Student Loans Bill 2016 through parliament.

The design of the proposed new program is intended to address significant issues with the operation of the previous scheme, including a clearer articulation that the program is designed to link training with employment outcomes; a new provider application process with a higher bar for entry based on track record; banning of brokers and curtailing the use of third party training providers; loan caps on eligible courses to put downward pressure on fees and protect students from rising debts; ensuring that payments to providers will be in arrears based on actual student numbers; requiring students to demonstrate genuine engagement in their training to continue to access their loan; and introducing stronger powers to allow the department to rapidly address matters of compliance or poor performance.

Information on the new VET Student Loans program and the transition from VET FEE−HELP, including fact sheets for students and new providers applying to participate in VET Student Loans, and arrangements for current VET FEE−HELP students and providers, is available on the department’s website at http://www.education.gov.au/vet-student-loans.

Australian Skills Quality Authority response

The Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) welcomes the report and its findings which documents the roles and responsibilities of the Australian Department of Education and Training, the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The report accurately describes the role of the Department of Education and Training as the administrator of the VET FEE−HELP scheme, including its role in approving, monitoring and ensuring the compliance of VET FEE−HELP providers.

The report accurately describes ASQA’s role in the regulation of Registered Training Organisations and the consultation that has occurred with ASQA in relation to the operation of the VET FEE−HELP Scheme, since ASQA’s establishment in July 2011 and the scheme’s expansion in 2012. During this period, ASQA has increasingly adopted a risk based approach to its regulatory task. This approach enabled ASQA to identify (in late 2014) and respond to the heightened risk within its legislative jurisdiction posed by a number of VET FEE−HELP providers and to work co−operatively with other agencies to share regulatory intelligence and co−ordinate regulatory activity.

Australian Taxation Office response

The ATO welcomes this review and considers the report supportive of our overall approach to administering loans and repayments under the Vocational Education and Training (VET) FEE-HELP scheme on behalf of the Government.

The ATO’s role under the VET FEE-HELP scheme is to receive these loans from the Department of Education and Training and then manage the loan and repayments of it. The ATO undertook this role in accordance with the legislative framework.

Following the review, and at the request of the Department of Education and Training, the ATO amended the process for accessing VET FEE-HELP loans and ceased providing Tax File Numbers (TFNs) directly to VET providers from the end of September 2016.

1. Background

VET FEE-HELP scheme

1.1 The VET FEE-HELP (VFH) scheme was a component of the Australian Government’s Higher Education Loan Program.5 Under the Higher Education Loan Program, eligible students could access Government income contingent loans, which removed up-front cost barriers to tertiary education and training. VFH loans were incurred by the student and the course fees paid directly to the education provider. Students are required to repay the loan(s) once their income reaches a minimum threshold.6

1.2 The VFH scheme was established in June 2008 under an amendment to the Higher Education Support Act 2003—the Higher Education Support Amendment (VET FEE-HELP Assistance) Act 2008.7 The legislative amendment and authorising VET Provider Guidelines:

- extended Commonwealth loan provisions, available to students in higher education, to full-fee paying students in the vocational education and training (VET) sector studying VET Diploma, Advanced Diploma, Graduate Diploma and Graduate Certificate courses;

- required that the Diploma and Advanced Diploma courses be credited towards a higher education qualification (credit transfer requirement); and

- established criteria for VET providers wishing to offer VFH loan places to be ‘approved’ VFH providers under the scheme.

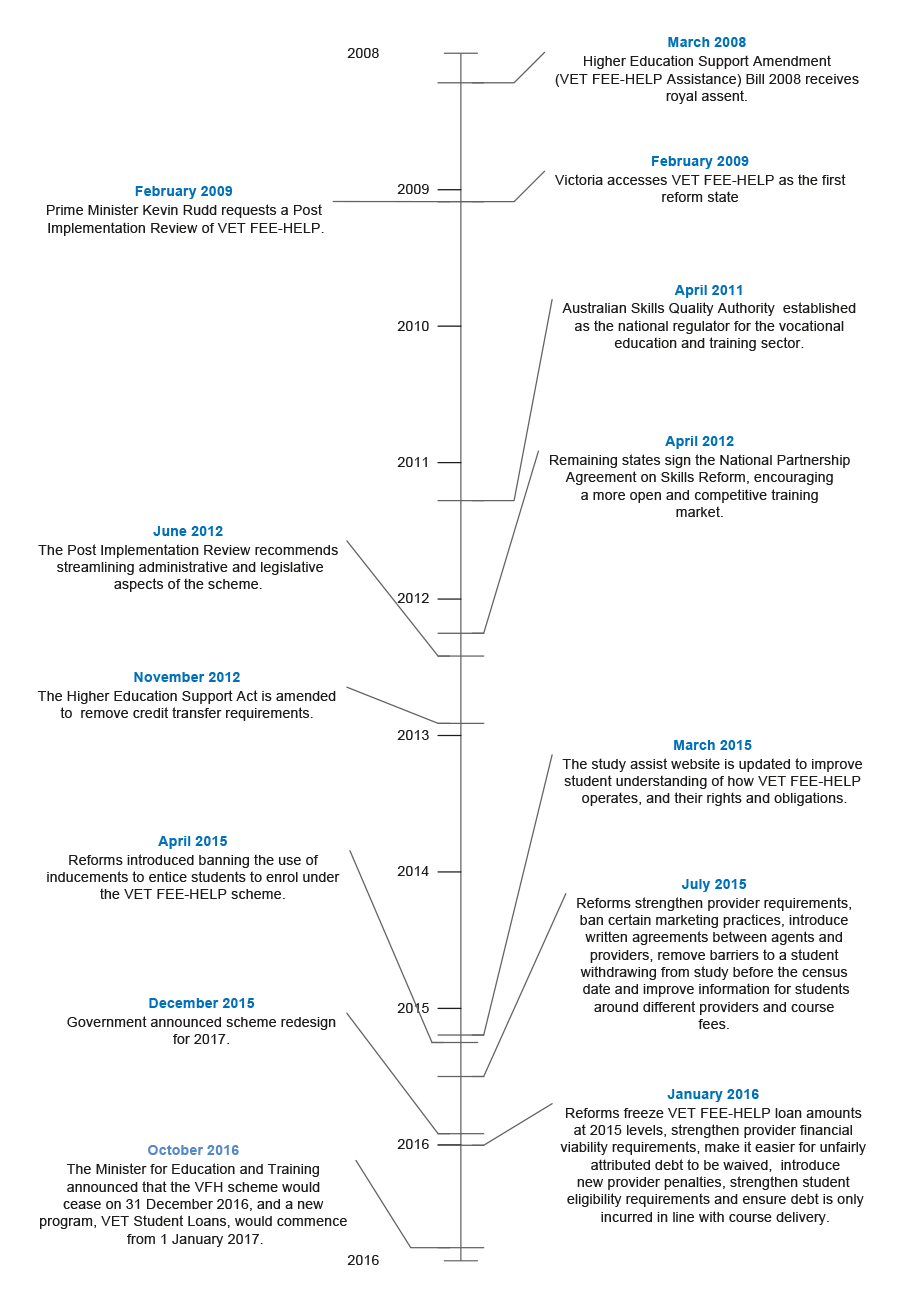

1.3 The focus of the VFH scheme on full-fee paying students was in line with the existing FEE-HELP scheme (that assists higher education students pay tuition fees), and was designed to offer financial support to those students who would not otherwise receive subsidies from state and territory governments to undertake a VET qualification. The credit transfer requirement regulated the standard of the VET course. Criteria for VET providers to be ‘approved’ under the VFH scheme included that they were a registered training organisation in the relevant jurisdiction. Figure 1.1 outlines the key developments in the introduction and operation of the VFH scheme.

Figure 1.1: Key developments in the VET FEE-HELP Scheme

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.4 Initially designed to support pathways to higher education, amendments to the VET Provider Guidelines in 2009 expanded access to the scheme by allowing all eligible students to access a VFH loan and abolishing course credit transfer requirements.8 Access to the expanded VFH scheme was initially only available to students in the VET sector in Victoria. Victoria was then the only jurisdiction deemed a ‘reform’ state by the Australian Government, on the basis of VET sector reforms underway at that time.9

1.5 The extended VFH scheme was subsequently available (from 2012) in all other states and territories as they agreed to reform their VET sector, and were also deemed ‘reform’ states by the Australian Government, through the Council of Australian Government Reform Agenda. From 2013, a trial to extend VFH loans to students in selected Certificate IV courses was also implemented (trial to end 31 December 2016), further increasing the number of students who could access a VFH loan.

1.6 These changes, and other measures to streamline administrative requirements of the scheme, resulted in significant growth in participation and cost. As shown in Figure 2.1 (in Chapter 2), almost 200 000 (full time equivalent) students accessed a VFH loan in 2015, to a total loan value of $2.9 billion (up from $25.6 million in 2009). Much of the growth occurred following the extension of the scheme in 2012, when $325 million in loans were issued. Growth reversed in 2016, following legislative and policy changes to the operation of the scheme, introduced from 1 April 2015.

1.7 The VFH scheme, within the broader Higher Education Loan Program, was administered by the Department of Education and Training from 2014, following several machinery of government changes over the life of the scheme (Appendix 2). The department was responsible for administering the VET FEE-HELP program under the Higher Education Support Act 2003 and the Higher Education Support (VET) Guidelines 2015. As such, it was responsible for provider approvals and payments, and various powers to undertake a range of compliance actions against VET FEE-HELP providers. Higher Education Loan Program debt is indexed annually, with repayments collected by the Australian Taxation Office.

Issues with the operation of the VFH scheme

1.8 Issues with the operation of the VFH scheme are well documented within the public domain, including through the:

- Higher Education Support Amendment (VET FEE-HELP and Tertiary Admission Centres) Bill 2009, Parliamentary Digest Services, Bills Digest No.3210;

- Discussion Paper, VET FEE-HELP Redesign 2012, Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education11;

- Higher Education Support Amendment (VET FEE-HELP Reform) Bill 2015, Parliamentary Digest Services, Bills Digest No.6012; and

- Redesigning VET FEE-HELP Discussion Paper 2016, Department of Education and Training.13

1.9 The VFH scheme also featured in an inquiry by the Senate Education and Employment References Committee. The final report of the inquiry, Getting our money’s worth: the operation, regulation and funding of private vocational education and training (VET) providers in Australia, October 2015, included 16 recommendations to strengthen the scheme’s regulatory and administrative provisions.14

1.10 In 2015, the ANAO audit Administration of Higher Education Loan Program Debt and Repayment found: there was limited measurement of the sustainability of the Higher Education Loan Program, including the VFH scheme; and ‘of particular significance is that the Department of Education and Training does not include in its reporting information about VFH debt, which is the fastest growing component of Higher Education Loan Program debt’.15

1.11 VET sector peak bodies, in their publicly available submissions16 to the Redesigning VET FEE-HELP Discussion Paper 2016, commented on unethical actions of some providers continuing to overshadow the reputation of ethical VET providers and the sector generally. Concerns raised about the operation of the VFH scheme included the:

- rapid growth of the scheme (the number of loans that could be accessed each year was uncapped) placed considerable pressure on the tuition assurance schemes provided by the peak bodies (TAFE Directors Australia and the Australian Council for Private Education and Training), with a heightened risk of large providers collapsing and displacing students17;

- unregulated use of brokers, agents and other intermediaries to enrol students; and

- added regulatory and administrative burden placed on all VET providers, with the introduction of measures (from 1 April 2015) intended to strengthen regulation of the scheme.

1.12 In October 2016, the Minister for Education and Training announced that the VFH scheme would cease on 31 December 2016, and a new program, VET Student Loans, would commence from 1 January 2017. The Minister stated that the new program ‘would return integrity to the vocational education sector and deliver a win-win for students and taxpayers through a range of protections’.18 Legislation for the new scheme was passed by Parliament on 1 December 2016.

Vocational education and training sector

1.13 Through a mix of public and private providers, Australia’s VET sector delivers accredited training in workplace specific and technical skills to approximately 4.5 million students annually. The sector is represented by: TAFE Directors Australia, the peak national body incorporated to represent Australia’s 58 government owned Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes and university TAFE divisions, and the Australia-Pacific Technical College; the Australian Council for Private Education and Training; and Community Colleges Australia, the peak body that represents and provides services to community owned, not-for-profit education and training providers.

1.14 The total number of registered training organisations operating in the VET sector from 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2016 decreased from 4947 to 4632.19 Registered training organisations that were approved as VFH providers (public and private) from 2008 to 30 June 2016 increased from five to 282, with the largest increase in private sector providers (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Approved VET FEE-HELP providers, 2008 to 30 June 2016

Source: Department of Education and Training Provider Details report.

Regulation of the vocational education and training sector

1.15 The Australian Skills Quality Authority is responsible for managing risks to the quality of vocational education and training outcomes for students, employers and the community. Throughout 2011–12, the Australian Skills Quality Authority assumed regulatory functions for the VET sector (through the Council of Australian Governments reform agenda) from most state and territory jurisdictions.20 From 1 July 2012, except for Victoria and Western Australia, the Australian Skills Quality Authority has had responsibility for registration and regulation of:

- vocational education and training providers;

- accredited vocational education and training courses; and

- the Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students providers, including those delivering English Language Intensive Courses to Overseas Students.

1.16 Victoria and Western Australia have maintained their own regulators, the: Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority; and Training Accreditation Council Western Australia. However, the Australian Skills Quality Authority retains regulatory functions in Victoria and Western Australia for registered training organisations that offer: courses in any state or territory other than Victoria or Western Australia, including by offering online courses; and courses to overseas students.

1.17 All VET providers (irrespective of the jurisdiction in which they operate) are regulated through the VET Quality Framework21, which aims to achieve greater national consistency in the way registered training organisations are registered and monitored, and how standards in the VET sector are enforced. In addition, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (and state and territory counterparts), having economy wide responsibilities in relation to consumer protection, can address misleading or unconscionable conduct of VFH providers.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and administration of the VET FEE-HELP scheme.

1.19 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- the design and implementation of the VFH scheme supported the achievement of the scheme’s objectives; and

- administrative arrangements safeguarded the operation of the VFH scheme, including by supporting students to understand their rights and obligations.

1.20 The audit focused on administration of the VFH scheme by the Department of Education and Training. The Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission were also designated in the audit.

1.21 In light of the announcement in October 2016 that the VFH scheme would cease on 31 December 2016, the audit report focuses on the causes of the key problems with the design and administration of the scheme. The aim is to inform debate about the proposed replacement VET Student Loans program, together with analysis and review of the VFH scheme undertaken by other entities. The lessons outlined in the report are also relevant to other Commonwealth entities in designing and implementing policies and programs.

Audit methodology

1.22 The ANAO reviewed records and information technology systems used by the Department of Education and Training to manage the VFH scheme, and interviewed departmental officers and key stakeholders in the VET sector.

2. Design and implementation of the VET FEE-HELP scheme

Areas examined

This chapter examines the design and implementation of the VET FEE-HELP (VFH) scheme and assesses if the scheme had met its objectives.

Conclusion

The design of the expanded VFH scheme in 2012 was weighted heavily towards supporting growth in the VET sector, but an appropriate quality and accountability framework addressing identified risks was not put in place. As the responsible department, Education did not establish processes to ensure that all objectives, risks and consequences were managed in implementing the expanded scheme. In effect, the department’s focus on increasing participation overrode integrity and accountability considerations that would have been expected given the inherent risks. The department inadequately considered the implications of the changed incentives facing providers and students in the redesigned scheme and its role in ensuring effective regulation in conjunction with other regulators—principally the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. There was also a lack of data analytics capability in Education and little internal management reporting or analysis of the VFH scheme to identify emerging problems. The department did not develop measures to assess broader objectives of the scheme (beyond growth) including those related to value and quality in the VET sector. In redesigning the VFH scheme, insufficient regard was given to relevant experiences in other jurisdictions, particularly Victoria, and the risks identified in a Regulation Impact Statement.

Were strategic and operational risks identified and addressed in the design of the expanded VET FEE-HELP scheme?

Strategic and operational risks were identified in the expansion of the VFH scheme in 2012, but were not adequately addressed in the legislative and policy design that significantly changed the requirements for participation in the scheme. While concerns about the application of legislative arrangements designed for higher education were identified in 2012, the expanded VFH scheme did not include adequate controls to manage risks specific to vocational education. Weaknesses included insufficient safeguards for students from misleading or deceptive conduct, and inadequate monitoring, investigation and payment controls for poor or non-compliant providers. The recommendation in a Regulation Impact Statement for a staged approach over three years did not occur, and the expanded scheme did not incorporate adequate controls over the risks identified in the statement.

2.1 The VFH scheme commenced in 2008, through amendments to legislative arrangements supporting loans to students in the higher education sector. The overarching objective of the scheme was to increase participation in vocational education and training. A Post Implementation Review22 of the VFH scheme released in June 2012, noted that the scheme had ‘taken off more slowly than anticipated’ and that:

- it was administratively complex, hindering participation rates;

- some elements of the scheme, based on a higher education model, were inappropriate; and

- the extension of the scheme in Victoria had translated into much higher registered training organisation (RTO) participation levels, resulting in significantly higher numbers of eligible courses and student enrolments.

2.2 The Post Implementation Review made ten recommendations to further improve take-up of the scheme by RTOs and students, including that credit transfer requirements be removed, and administrative and legislative aspects of the scheme be streamlined. In response to the review, the department’s Discussion Paper VET FEE-HELP Redesign 201223, sought submissions from stakeholders (by 22 July 2012), on proposed changes to the scheme. The discussion paper included that the scheme required redesign to ensure that it better met the needs and operational realities of the VET sector, in order to:

- improve student access and participation in VET;

- simplify, streamline and improve the suitability of the scheme in the VET sector without compromising its quality and integrity;

- improve the take up of VFH by states and territories and quality RTOs; and

- improve stakeholder’s experience with the scheme.

2.3 Changes to the scheme were subsequently implemented later that year, through legislative amendments (with further minor amendments in 2013)24 and changes to the VET Provider Guidelines that removed many of the barriers to RTO and student participation, including by:

- abolishing the credit transfer requirements (to higher education), which allowed more RTOs to become VFH providers and increased the range of courses for which a VFH loan could be accessed;

- extending the loan facility to state or territory subsidised students outside Victoria, which increased the number of students who were eligible for a VFH loan; and

- streamlining many of the administrative requirements (for example, more flexible arrangements associated with the setting and reporting of census dates25), which simplified the compliance requirements for approved VFH providers.

2.4 The growth in the number of students accessing a VFH loan between 2009 and 2016, and the estimate and mid-year revision of the estimate for each year is shown in Figure 2.1. The data reflects the initially slow take up of the scheme prior to 2012, and large variations between estimates and actual numbers as the expanded VFH scheme was fully implemented from 2013 to 2015, when student numbers and the value of loans peaked. The estimated reduction in participation in the scheme in 2016 is a result of further legislative and policy amendments, implemented from 1 April 2015, to address issues with the operation of the expanded scheme (discussed later in this report).

Figure 2.1: Estimated and actual VFH student places, 2009 to 2016

Note: EFTSL, equivalent full-time student load for one year.

Source: ANAO analysis of estimated and actual EFTSL for which VFH loans were paid, published in the annual reports of the departments with responsibility for administration of the VFH scheme 2009 to 2015 (refer Appendix 2); and Portfolio Budget Statements 2016 and 2017. Actual and estimated actual places to December 2016 provided by Education.

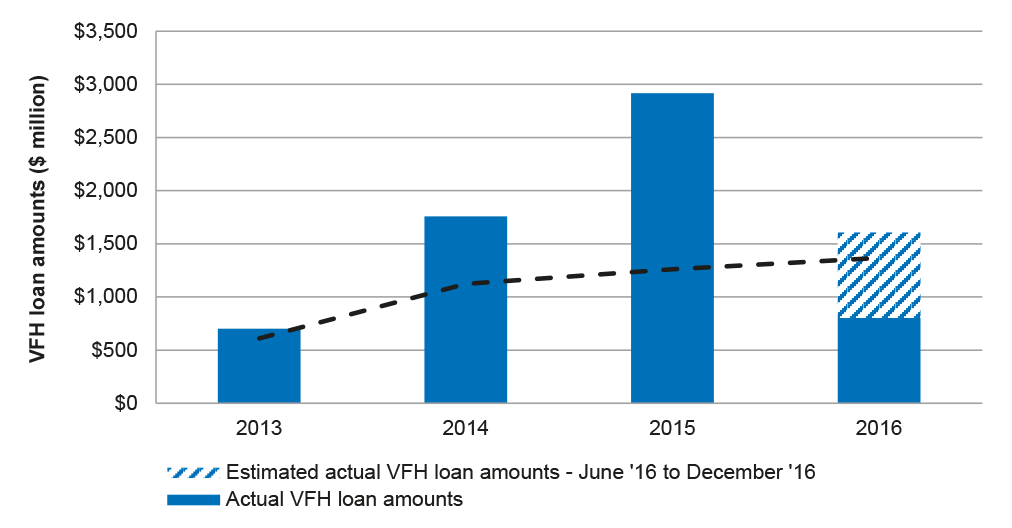

2.5 As a result of rapidly increasing course fees, the value of loans issued under the expanded VFH scheme significantly exceeded forecasts in departmental modelling conducted in March 2013 (Figure 2.2). This was contrary to the number of students accessing VFH loans not reaching forecasts as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.2: Forecast and actual value of VFH loans, 2013 to 2016

Source: ANAO analysis of forecast VFH loan amounts from an internal Education Costing Model of March 2013, and data as to actual and estimated (to December 2016) VFH loans paid provided by Education in 2016.

Strategic and operational risks associated with the expanded VFH scheme

2.6 Strategic and operational risks associated with the expanded VFH scheme were identified in the Regulation Impact Statement VET FEE-HELP Redesign 2012 that accompanied the Higher Education Support Amendment (Streamlining and Other Measures) Bill 2012.

2.7 The Regulation Impact Statement, commenting on the initial design of the VFH scheme (that included credit transfer requirements with higher education providers) and on aspects of the functioning of the expanded scheme in Victoria from 2009, included, p. 7:

VET FEE-HELP’s requirements for participating RTOs are rigorous to ensure there are effective safeguards for students and public monies. However, the administrative burden imposed by the Government is proving to be a barrier to participation for most RTOs. Thus competing interests exist between reducing barriers to increase participation in VET FEE-HELP, while maintaining the HELP scheme’s integrity.

The quality of RTOs across the VET sector varies. As VET FEE-HELP will be progressively extended to state and territory subsidised VET diploma and advanced diplomas nationally, it is vital that VET FEE-HELP is underpinned by a framework supporting quality outcomes for all stakeholders. Current mechanisms in place to ensure quality under VET FEE-HELP should be enhanced to protect students and public monies through the:

- improvement of suspension and revocation provisions;

- introduction of safeguards for students from misleading or deceptive conduct; and

- improvement of transparency and the ability to share information.

If the limitations identified with VET FEE-HELP’s quality and accountability framework are not addressed, the potential to damage industry confidence in the quality of VET qualifications and the role of VET FEE-HELP is high. As VET FEE-HELP continues to grow, improvements to the quality framework underpinning the HELP schemes are key to ensuring its agility and robustness in a dynamic skills environment.

2.8 The Regulation Impact Statement included (p. 8) that the Government’s ability to reduce the administrative and compliance burden on RTOs, while maintaining the quality and integrity of the scheme, was limited by a number of legislative and regulatory arrangements (applicable at that time). These limitations included: the lack of provisions (in the Higher Education Support Act 2003) ‘to prohibit a person or body corporate from misrepresenting or misleading potential students’, referring to complaints to the Government that had identified instances where people with an intellectual disability had been targeted for enrolment, or gifts had been offered to students as an incentive to enrol in courses; and that there were no legislative provisions to enable the Government to deter or stop such actions from occurring.

2.9 The Regulation Impact Statement recommended a staged implementation of the redesign of the VFH scheme over a three-year period (to 2014–15), noting that such an approach aligned with the Council of Australian Governments National Partnership and implementation could ‘occur with sufficient lead times, thereby minimising the cost and disruption to RTOs and the Government’.

Issues with the design and control of the expanded VFH scheme

2.10 The purpose of the amendments in the Higher Education Support Amendment (Streamlining and Other Measures) Act 2012 reflected the risks identified in the Regulation Impact Statement:

The purpose of the amendments are to strengthen the integrity and quality framework underpinning the HELP schemes, improve information sharing and transparency with the national education regulators, improve arrangements for the early identification of low quality providers, and position the Government to better manage risk to students and public monies.

2.11 The legislation sought to balance measures to allow increased access to quality vocational education and training, while maintaining the integrity of the VFH scheme. The amendments significantly changed the dynamics of a scheme that had been implemented (in 2008) to align ‘as much as possible with the FEE-HELP scheme operating in the higher education sector, and a high bar was set to ensure only quality [RTOs] were approved to effectively manage the risks to students and public monies’. The substantive changes to the VFH scheme were acknowledged in the recommendation in the Regulation Impact Statement for a staged implementation, but this did not occur.

2.12 Rather, with an emphasis on increasing participation in vocational education and training, insufficient consideration was given to the design of the expanded VFH scheme to achieve a balance between streamlining requirements for participation in the scheme, and maintaining an effective regulatory framework that would have addressed a range of risks, including those associated with:

- the incentives available to VFH providers operating in an environment where payment of a loan was based on student enrolment in an eligible VFH course, with no controls as to the capacity of the student to participate in, or to complete the course; and little protection for students as consumers of vocational education and training, particularly those with lower levels of education and financial literacy26;

- the financial incentives, and low barriers to entry, which influenced the quality and usefulness of VET courses, as some VFH providers based their course offerings on training that attracted the highest subsidy, benefit or profit, at the lowest cost. Consequently, lower standard training was provided to students in areas where skill shortages did not exist;

- reduced sensitivity to pricing among students accessing VFH loans that allowed providers to substantially increase their course fees27; and

- lack of clarity about the roles and regulatory powers of the department and those of VET regulators, where Education had responsibility for VFH provider approvals and payments, and various powers to undertake a range of compliance actions against VFH providers.

2.13 Consequently, within two years of the implementation of the expanded VFH scheme, measures were being developed to address loopholes in the regulatory framework that were being exploited by some VFH providers and undermining the reputation of the VET sector. Some measures were implemented quickly through the VET Guidelines, while others required legislative changes.28 The full list of guideline and legislative changes to the VFH scheme, introduced in three tranches in: 1 April 2015, 1 July 2015 and 1 January 2016, are shown in Appendix 3 (as listed in the Redesigning VET FEE-HELP: Discussion Paper 2016, p. 50). Of note, are the measures introduced to protect vulnerable students, identified as a risk in the 2012 Regulation Impact Statement.

2.14 The integrity and quality framework underpinning the expanded VFH scheme in 2012 would have been stronger if greater emphasis had been placed on addressing the risks outlined in the Regulation Impact Statement. There was also the opportunity for the design of the expanded scheme to have paid greater attention to the lessons learned from the expansion of the VFH scheme in Victoria (as discussed in the Regulation Impact Statement), where similar issues to those that affected the expanded VFH scheme had emerged earlier in Victoria, as it was the lead state in implementing the expanded VFH reforms.

Levels of loan debt

2.15 The new measures also aimed to address the levels of VFH loan debt to the Commonwealth. The ANAO audit Administration of Higher Education Loan Program Debt and Repayments included that the value of total HELP debt was projected to grow to approximately $67.6 billion by 2017–18. At that time, VFH was the fastest growing component of the program and the repayment prospects for this debt were relatively unknown. The audit also found that the ATO, which has responsibility for monitoring and managing HELP debt, did not differentiate between debt associated with the higher education and VET sectors, and consequently repayment information was not available by loan type. The report also noted that Education was unable to demonstrate that it routinely monitored and analysed factors affecting the repayment of HELP debt.29

2.16 The Australian Government Actuary models the HELP doubtful debt for the purposes of financial reporting on the HELP asset. The report of the Australian Government Actuary to Education, 18 August 2016, estimated that $1.2 billion relating to loans issued inappropriately by VFH providers in 2014 and 2015 would not be recovered. The Actuary also estimated that a further $1.0 billion in VFH loans would not be repaid, largely relating to loan recipients not expected to meet the income repayment threshold for new debts raised in 2015–16.30

2.17 In November 2015, the department received Government approval to develop an expanded HELP debtor database, to improve the understanding and management of loan debt. The database will match demographic and educational data from the department and income and occupation-related information from the Australian Taxation Office, and will contain actuarial analysis on the likelihood of debt repayment from the Australian Government Actuary. Education expects that an initial version of the database will become available by mid-2017.

Were arrangements in place between agencies to monitor implementation risks?

Arrangements were not in place between Education and the regulatory agencies to effectively monitor and address risks to the implementation of the expanded VFH scheme, particularly in relation to integrity, quality and sustainability. There was poor engagement by Education with the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to exchange information and intelligence about low quality or unscrupulous VFH providers. Within Education, until 2016 there was little analysis or internal management reporting of the VFH scheme to identify emerging problems.

2.18 Education had responsibility for administering the VFH scheme under the Higher Education Support Act 200331, and other agencies interacted with it in important ways:

- registration as a RTO with the Australian Skills Quality Authority, or the state regulatory bodies, (the Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority, and Training Accreditation Council Western Australia), was a pre-condition to being approved as a VFH provider (from April 2015, RTO status was renewed every seven, previously five, years);

- Australian Consumer Law regulators32, provide protection to consumers across all sectors of the economy and can address misleading or unconscionable market behaviour of VFH providers;

- the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (a not-for-profit company owned by the Commonwealth and state and territory ministers with responsibility for vocational education and training) provides research and statistics about the VET sector; and

- the Australian Taxation Office collects debt incurred by students accessing loans through the Higher Education Loan Program.

2.19 Legislative amendments establishing the expanded VFH scheme included to improve information sharing and transparency with the national education regulators, and improve arrangements for the early identification of low quality providers.

Information sharing with other agencies

2.20 Prior to early 2015, there is little evidence that Education had engaged with other agencies to exchange information, data or intelligence about the operation of the VFH scheme, other than in relation to the assessment of applications from RTOs for VFH provider status.33 Consequently, these agencies had limited visibility of the levels of proposed and/or actual funds paid to providers, or the growth in student numbers, that would have been relevant to their regulatory and compliance functions.

2.21 There is also little evidence that Education, in its administration of the VFH scheme, gave due consideration to information and/or intelligence gained by those agencies. For example, the report of a national strategic review conducted by the Australian Skills Quality Authority, Marketing and advertising practices of Australia’s registered training organisations (published September 2013) was initiated ‘because of the serious and persistent concerns raised within the training sector about registered training organisations and other bodies providing misleading information in the marketing and advertising of training services’.34 The review examined the websites of 480 organisations and their online marketing and advertising of training services. Of these 480 websites, 421 belonged to RTOs and 59 to organisations that were not RTOs, and the review found that:

45.4 per cent of RTOs investigated could be in breach of the national standards required for registration as an RTO under the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 and of the Australian consumer law and/or state and territory fair trading laws with respect to their marketing and advertising. These potential breaches range from relatively minor concerns that can and should be rectified quickly and easily, to more serious breaches that could involve major sanctions being applied, including a loss of the RTO’s registration.35

2.22 An internal Education minute of 10 June 2014 sought approval to forward information about the VFH scheme, collected under the Higher Education Support Act 200336 (including funding amounts, number of students, course costs and completions) to the Australian Skills Quality Authority ‘annually, intermittently or as requested’. The purpose was to determine if issues concerning the behaviour of some VFH providers were present under the Australian Skills Quality Authority legislation. The provision of information to the Australian Skills Quality Authority was made in response to Education’s concerns about VFH provider growth (refer Table 3.1):

… occurring now and in recent years, of thousands of percent over a period of 24 months, 12 months or less is untenable and we hold serious concerns regarding the level of quality of training, student support available and the risk of minimal beneficial outcomes for students.

2.23 The delegate approved the provision of data, with instructions that a Memorandum of Understanding be developed to support the arrangement. The Memorandum of Understanding between the Australian Skills Quality Authority and Education was not established until June 2016, although the Australian Skills Quality Authority had been provided with data from early January 2015.

2.24 As at September 2016, Education advised that it was revising the current Memorandum of Understanding with the Australian Taxation Office (on HELP administration) in relation to HELP debt, and developing a separate agreement with the Australian Government Actuary.

Monitoring of the VFH scheme by the Department of Education and Training

2.25 Advice from Education was that it had not realised the extent of the problems with the operation of the VFH scheme until late 2014, when verified data of the number of students accessing a VFH loan in the first six months of the year was available (Figure 2.1). This data showed extremely rapid growth in uptake of the scheme in that period, requiring a 30 per cent variation to the budget estimates for 2014–15 (increased from 172 300 students in May 2014 to 225 500 in February 2015).37

2.26 The expanded VFH scheme had been designed to increase participation in vocational education and training, but there was little evidence that trends in key aspects of the scheme had been monitored, analysed or reported, in light of the risks identified in the 2012 Regulation Impact Statement, and to support the early identification of low quality providers and better manage risk to students and public monies. Education advised that departmental executive reporting on the VFH scheme had typically been provided through quarterly briefs prepared for meetings of Senate Estimates committees and in periodic briefs on individual matters.

2.27 It would have been prudent for Education to have monitored scheme participation against estimated cost from the outset of the expanded scheme, as the higher cost per student would have provided it with an earlier appreciation of the impact of VFH course fee price increases on the sustainability of the scheme (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2). Analysis of characteristics of the scheme such as trends in uptake in disadvantaged and remote communities, including type of courses (such as business administration), and completion rates would also have provided the department with an earlier appreciation of problems with the implementation of the scheme.

2.28 In mid-2015 the lack of a strong data analytics capability was identified by Education as a significant issue in the administration of the VFH scheme. Problems identified included: a general lack of priority allocated to VFH data production; higher than acceptable error rates; expertise gaps; inconsistent reporting; and a significant backlog of data requests resulting in an over-reliance on other teams in the broader HELP program. There was very limited capability to utilise data analytics to identify emerging and existing risks, develop new policy ideas and prepare for the redesign of the program. In 2016 the department increased its internal capability and capacity to collect and analyse data38, and new standards of executive reporting are being developed.

Did the VET FEE-HELP scheme achieve its objectives?

The VFH scheme did not achieve many of its stated objectives, and is to be replaced by the VET Student Loans program from 1 January 2017.

While achieving increased participation in vocational education and training as intended following the expansion in 2012, Education did not provide evidence that the scheme achieved objectives relating to quality, value and sustainability of the VET sector, consumer protections, or support for the productivity and skills agenda. In analysing the performance of the scheme, Education did not develop measures to assess broader objectives of the scheme, including those related to value and quality in the VET sector, and did not revise the key objectives and outcomes following expansion of the scheme.

2.29 The broad objectives of the VFH scheme, developed through the Council of Australian Government National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development (revised April 2012), and National Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform (April 2012 to June 2017), were to: build a more highly skilled workforce; provide equity to students in the VET sector with higher education students; and support reform of the VET sector across state and territory jurisdictions.39 More detailed objectives and outcomes of the scheme are illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: VET FEE-HELP scheme: key objectives and outcomes

Note: * relate to the VFH scheme before the credit transfer requirement to higher education was abolished.

Source: ANAO, adapted from the Post Implementation Review (2011) of the VET FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme.

2.30 The expanded VFH scheme achieved increased participation in vocational education and training, but measuring the success of the VFH scheme against other objectives, including those relating to quality and value in the VET sector, is more challenging. The report of a review commissioned by the Victorian Department of Education and Training included that (p. 6)40:

A demand driven VET sector, like Victoria’s, is vulnerable to a range of market failures and equity issues that can lead to sub-optimal quality outcomes. This is in part due to the:

- structure of the VET market, which has a large number of providers and a diverse range of qualifications, which can lead to overwhelming choice;

- cohort of VET consumers, which includes young students, those with low levels of education and financial literacy and other vulnerabilities;

- nature of VET, which by its very nature is: (1) an 'experienced good', making quality difficult to assess until after completion; and (2) competency based, encouraging flexibility but reducing comparability between individual services or outcomes.

2.31 While recognising the challenges in measuring the success of the VFH scheme against objectives other than growth and participation, Education did not provide evidence that the scheme achieved many of its objectives, including those relating to quality, value and sustainability of the VET sector, consumer protections, or support for the productivity and skills agenda. Education did not develop performance measures, or draw on information from other regulators, such as the Australian Skills Quality Authority, to assess the broader outcomes of the scheme.

2.32 In addition, the objectives and outcomes shown in Figure 2.3 reflect the design of the scheme before the credit transfer requirement (to higher education) was abolished and have not been subsequently revised. In external reporting, Education reports only on the number of VFH loans accessed each year, against Portfolio Budget Statements estimates.41

VET Student Loans program

2.33 Irrespective of reforms implemented in 2015 and 2016 (as set out in Appendix 3), the Redesigning VET FEE-HELP Discussion Paper 2016 reported that the Government considered the VFH scheme was not sustainable in its current form. On 5 October 2016, the Minister for Education and Training announced cessation of the VFH scheme and implementation of a new program, VET Student Loans, from 1 January 2017.

2.34 The objectives of the new VET Student Loans program are yet to be finalised, with the current focus on arrangements to strengthen administration of loans to provide value for money to both students and taxpayers via tougher barriers to entry for providers. The program will include:42

properly considered loan caps on courses, stronger course eligibility criteria that aligns with industry needs, mandatory student engagement measures, a prohibition on the use of brokers to recruit students and a stronger focus on students successfully completing courses.

Characteristics of the new scheme are set out in Box 1.

|

Box 1: Characteristics of the VET Student Loans program to be implemented from 1 January 2017 |

|

Source: Announcement by Minister for Education and Training, media release, 5 October 2016.

3. Administration of the VET FEE-HELP scheme

Areas examined

This report preparation paper examines administrative arrangements to safeguard the operation of the VET FEE-HELP (VFH) scheme.

Conclusion

The administration of the VFH scheme did not safeguard the operation of the VFH scheme, and did not support the achievement of objectives relating to integrity, quality, value and sustainability. Similar to the scheme’s design and implementation failures, there were weaknesses in Education’s administrative processes for: approving VFH providers; developing and undertaking risk, fraud and compliance activities; controlling payments to providers; making information readily available to students about their rights and obligations under the VFH scheme; and managing and resolving student complaints. While improvements were made to many of these processes in 2016, they were in place for a relatively short period of time prior to the cessation of the VFH scheme from 31 December 2016.

Did the approval process for VET FEE-HELP provider status effectively mitigate risks to the scheme?

There was no evidence of adequate consideration of risk in the development of the approval process for registered training organisations to achieve VFH provider status, or that the process effectively safeguarded the VFH scheme at this early stage of provider engagement. Education did not analyse the results of the process to understand the behaviour and motivation of organisations seeking access to the VFH loan scheme, and how best to strengthen the approval process.

3.1 To become an approved VFH provider in the VFH scheme, a training organisation had to first be registered as a registered training organisation (RTO) by the regulator within the relevant jurisdiction. The RTO then registered for access to Education’s Higher Education Loan Program information technology system (a high level view of the systems used for administering the program, including the VFH scheme, is at Appendix 4), which enabled it to lodge an online application to Education to be assessed for VFH provider status. Once approved, VFH providers were not required to re-apply for VFH status, as long as their RTO registration remained valid.

3.2 The 2012 post implementation review of the design of the VFH scheme recommended streamlining the application process to encourage greater participation by RTOs within the VET sector. The post implementation review included that, in the previous year, some 562 RTOs commenced an application to become a VFH provider, but did not finalise and submit their applications:

Some of the more significant issues experienced by RTOs was the substantial support required during the application process, particularly in regards to an RTO’s ability to meet the financial viability, principal purpose, credit transfer and tuition assurance requirements. This meant that many applicants withdrew or were not approved under the Scheme.43

3.3 Credit transfer requirements were abolished in 2012, but other components of the application process were retained, and the extent of the assessment process for VFH provider status (over and above the requirements for RTO registration44) remained substantial, as would be expected for a scheme that provided access to considerable public funds.

3.4 The financial viability requirements45, for example, were reviewed and strengthened at various times since commencement of the scheme and included consideration of 26 financial viability risk indicators, supported through the provision of accounts and financial reports. Applicants for VFH provider status were also assessed in terms of the Fit and Proper Person Specified Matters 2012 instrument46 that focuses on the person’s record of honesty, financial management and compliance with relevant regulatory schemes. Nevertheless, the number of applications for VFH provider status increased from 2012 to 2015 (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: Applications received from registered training organisations seeking approved VET FEE-HELP provider status, 2008 to 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of the Department of Education and Training applications data.

3.5 There is no evidence that adequate consideration of risk was undertaken in developing the approval process, and that the process effectively mitigated risks to the VFH scheme at this early stage of provider engagement.

3.6 Data on applications lodged with Education from 1 January 2009 to 17 August 2016 showed that of the 1538 applications commenced by RTOs over the period, at 17 August 2016, 925 had been withdrawn or discarded. The number of applicants who commenced but subsequently withdrew or discarded their application may indicate that aspects of the application process were working effectively (by deterring potentially non-compliant providers). The additional requirements for VFH provider status, introduced from 1 January 2016 (including that RTOs seeking approval as VFH providers must have been trading since at least 1 January 2011) would also have reduced the number of RTOs that applied. However, Education did not routinely report on or analyse data on the status and outcomes of applications to support an understanding of the behaviour and motivation of organisations seeking access to the VFH loan scheme. Such analysis could have been considered in strengthening the approval process to help ensure that only suitable RTOs gained access to the scheme.

Were approved VET FEE-HELP providers effectively monitored and regulated?

VFH providers were not effectively monitored and regulated by Education. The department acknowledges that there was not an effective compliance framework for the scheme, noting the serious limitations in its compliance powers under the VFH legislation. In effect, there was very limited and reactive compliance activity, including of the expanded VFH scheme from 2012. Education did not act promptly at that time to clarify the roles and regulatory powers of the department and other regulators, to ensure a sound regulatory framework for VFH. From mid-2015, compliance and regulatory activities increased in response to the identified risks. Education initiated several major compliance audits, began the development of a new risk-based compliance framework, and worked with Australian Consumer Law regulators in taking a number of established VFH providers to court under the prevailing VFH legislation.

3.7 Prior to 2012, Education’s approach to providing assurance for the VFH scheme was largely reactive, responding on a case-by-case basis to risks emerging among existing providers; and, as previously discussed, with little reference to data and or information from the VET or Australian Consumer Law regulators. Following legislative amendments in 2012, the department initiated a number of measures to develop a risk-based approach47 but these were not effectively implemented. Measures included:

- 2012, commissioning the development of a Risk Assessment Tool to assess the levels of risks associated with each provider;

- 2013, developing the HELP Program Assurance Strategy, 2013–14 (not VFH specific);

- 2014, commissioning a high-level review of the department’s VFH compliance framework, finalised in December 2015.48 The report of the review included that the: risk indicators in the Risk Assessment Tool were not reliable in assessing provider risk, providing ‘false comfort’ to the overall level of compliance risk within the VFH scheme; and the department discontinue use of the Risk Assessment Tool and build a new compliance framework; and

- 2015, separating the compliance approach for VFH from the broader strategy and developing the VET FEE-HELP Compliance Strategy 2015-2017, but the strategy lacked detail and was never implemented.

3.8 The department was able to provide only limited detail of compliance activities49 relevant to the VFH scheme (conducted from commencement of the scheme to 2016), advising that information may be available regarding some compliance audits undertaken in 2014 and 2015 in the department’s electronic record management system (TRIM) but may be difficult to identify. Information regarding compliance activities and audits underway in 2016 is further discussed below.

3.9 The Redesigning VET FEE-HELP Discussion Paper 2016 acknowledged that there had not been an effective compliance framework, noting that there continued to be serious limitations in the department’s compliance powers, irrespective of new measures introduced from 1 January 2016. Key limitations included:

- significant non-compliance by a provider with the Higher Education Support Act 2003 and the VET Guidelines does not necessarily undermine a provider’s right to payment;

- audit and information gathering powers are currently weak and do not enable the department to search and seize documents and image computer systems. Rather, the powers principally rely on the cooperation of the VFH provider; and

- limited capacity for the department to take compliance action against a provider where the provider’s RTO status had been cancelled by the Australian Skills Quality Authority, and the cancellation is subject to a merits review.

3.10 The ANAO also notes that elements of the VFH operating environment were conducive to designing an effective compliance strategy. In particular, there was a relatively small number of providers (282 in June 2016), with ready opportunities for the department to identify the smaller number of providers at greater risk of non-compliance, in terms of likelihood and consequence, to direct its compliance activities. For example, Education could have focussed on larger, newer and more rapidly expanded private providers, and those with higher rates of disadvantaged students and lower course completion rates, if it had applied a risk-based compliance approach commonly employed across Australian Government programs.

New compliance activities in 2016

3.11 In the May 2015 Federal Budget, Education received $18.2 million in additional funds over the four year forward estimates for the implementation of an enhanced compliance regime for VFH, including to develop a new performance and risk management framework, and to improve the data collection and reporting capability of the department. Of the total amount, $3.6 million was allocated for capital costs to enhance the information technology systems supporting administration of the scheme and broader Higher Education Loan Program.

3.12 As at August 2016, Education had seconded (from November 2015) a Senior Executive Officer from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to: lead a new focus on major compliance under the current arrangements for the VFH scheme; and develop a new compliance framework and strategy, complaint handling strategy and a new records management plan, to support the redesigned scheme when it commences in 2017.

Compliance activities

3.13 Education is working with regulators (the Australian Skills Quality Authority, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and state and territory counterparts) to: identify VFH providers at the higher end of inappropriate business practices, non-compliance, and perceived fraudulent activity; and initiate appropriate action. Student surveys (commissioned by Education) showed that around 25 per cent of enrolments submitted to Education by these VFH providers were for students who were unaware they had been enrolled in a course, or had entered into a loan arrangement. The extent of this problem beyond the surveyed VFH providers is unknown.50

3.14 As at 29 August 2016, audits of 28 VFH providers were underway, of which: 19 were compliance and payment audits, and nine were primarily focussed on payment issues. The department had received some initial draft audit reports and was analysing these. The preliminary findings of the draft audit reports appear to provide a basis for the department undertaking compliance action against a number of providers, and for withholding and potential reduction of payments to a number of providers.51

3.15 The department also advised that it has joined as a party to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Federal Court action against four VFH providers for alleged misleading and unconscionable conduct, in breach of the Australian Consumer Law when marketing VFH funded courses.52 The department joined the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s court action primarily to assist in seeking to recover payments the Commonwealth made to the VFH providers if the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission is successful in getting a student’s debt cancelled due to breaches of consumer law.

3.16 As discussed in Chapter 2 (paragraph 2.12), there was a lack of clarity about the roles of Education and other regulators following the expansion of the VFH scheme in 2012. As the agency with primary responsibility for administering the scheme, it was the role of Education to assess the strength of the regulatory environment and take steps to address any notable shortcomings. Accordingly, Education should have more promptly informed government of the need for additional regulatory controls to ensure higher quality training, contract management and market oversight, as the government was providing a significant financial investment. Education should also have increased its own compliance activity more promptly following the expansion of the scheme in 2012, notwithstanding limitations to its compliance powers.

3.17 Issues with the integrity of the VFH scheme had substantial implications for the workload of regulators. The Australian Skills Quality Authority advised in September 2016 that the amount of resources devoted to the regulatory scrutiny of RTOs that were also VFH approved providers was significant and in excess of the proportion of the total number of RTO’s within the regulator’s responsibility—less than 6 per cent of the 4000 plus providers regulated by the authority.53 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission also advised that it had dedicated considerable resources and fast tracked its actions in the VFH area. Investigations included in the order of 10 per cent of the commission’s consumer protection investigators through the life of the matters, being more than any other consumer protection issue in the period; and in 2015–16, five of 19 cases commenced in the Federal Court concerned VFH.

Were payments to approved VET FEE-HELP providers effectively calculated and controlled?

Payments to approved VFH providers were calculated on data submitted by VFH providers and not effectively controlled. Education had little visibility of the students entering into a loan arrangement through their VFH providers; and relied on self-reporting by providers. There were also weaknesses in departmental guidance provided to staff processing the payments, and in evidence supporting delegate approval of the payments.

Establishing a VFH loan

3.18 The process of enrolling in a VET course and applying for a VFH loan was conducted between a student and the VFH provider, using the Commonwealth Assistance Form: Request for a VET FEE-HELP loan form that was only available from the provider.54 The form was to be completed and signed by the student applying for the loan.

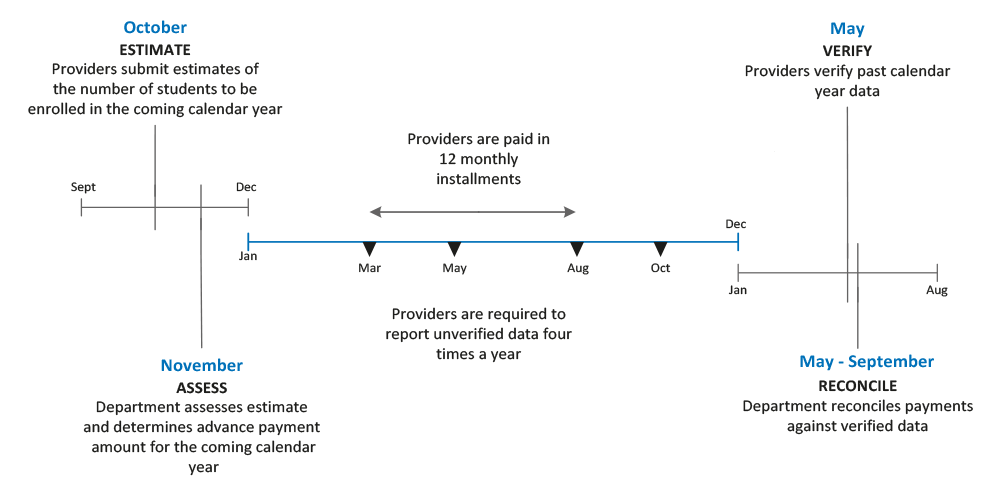

3.19 Education had no visibility of students accessing a VFH loan, even though the critical consideration for determining payments to VFH providers was whether or not the students enrolling with a VFH provider had an entitlement to VFH. The application process for enrolling in a VET course and accessing a VFH loan is outlined in Appendix 5. It shows the limited role of Education in the process, and indicates the department’s reliance on identification processes of the Australian Taxation Office.

3.20 All applications for VFH loans must include the student’s tax file number (TFN). Through ‘authorised contact’ arrangements, the Australian Tax Office supplied VFH providers with the TFNs of students enrolled in a VET course, where the TFN had not been provided by the student.55 The arrangement was also in place for higher education providers. The Australian Tax Office estimates that, since 2009, it has responded to thousands of requests from VFH providers for student TFNs, with some requests listing up to 200 students. As at 29 August 2016, Education advised that:

… the department has become aware that authorised representatives of VET FEE-HELP providers can obtain, confirm or clarify an individual’s tax file number (TFN) directly with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). The VET FEE-HELP Branch’s compliance team were made aware of this when people had stated in their statutory declarations that they had either not given a TFN, or had suspected it was a scam and provided a broker with a made up TFN. However, subsequently these people have been recorded in [Education’s information technology systems] as being enrolled with a VET FEE-HELP provider and having a VET FEE-HELP debt.