Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Domestic Fishing Compliance Program

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Fisheries Management Authority’s administration of its Domestic Fishing Compliance Program.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Fishing Zone is the world’s third largest and it extends up to 200 nautical miles offshore.3 In 2010–11, the gross value of Australia’s fisheries production was $2.23 billion, including high-value export species such as salmonoids, rocklobster, prawns, abalone and tuna. The fishing industry is estimated to employ over 100 000 people, both directly in fishing activities, and indirectly in post-catch activities, such as processing, transport, wholesale and retail, and restaurants.4

2. The Australian Government manages commercial fishing in waters from three nautical miles offshore to the limit of the Australian Fishing Zone (Commonwealth fisheries). The states and territories manage fisheries in inland and coastal waters (up to three nautical miles offshore). Generally, the state and territory governments also assume responsibility for recreational fishing in the Australian Fishing Zone. The Commonwealth fisheries are shown in Figure S1 on the following page.

3. The Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA or the Authority) is the Australian Government agency responsible for the efficient and sustainable management of Commonwealth fish resources on behalf of the Australian community. AFMA was established as a statutory authority in 1992 and operates under the Fisheries Administration Act 1991 (the FA Act) and the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (the FM Act).

4. AFMA’s core responsibilities include: developing management plans for all Commonwealth fisheries; providing information to inform the setting of Total Allowable Catch (TAC) for Commonwealth fisheries; issuing and managing licences for commercial fishing activity in Commonwealth fisheries; collecting scientific data to inform fisheries management5; managing the domestic and foreign fishing compliance programs; and providing input into international forums.

Figure S1 Commonwealth fisheries

Source: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

Note: The Southern and Eastern Shark and Scalefish Fishery (not shown on map) incorporates the Commonwealth Trawl Sector, Commonwealth Great Australian Bight Trawl Sector, East Coast Deepwater Trawl Sector, and Gillnet Hook and Trap Sector Fisheries.

5. AFMA has an annual budget of around $42 million, with approximately $14 million cost recovered from the fishing industry, via levies on licence holders.6 The levies are set each year based on AFMA’s anticipated costs of managing each fishery for the following financial year. The levies do not cover the costs of AFMA’s Domestic Fishing Compliance Program (Domestic Compliance Program), as these costs are funded directly by the Australian Government.7

6. In September 2012, the Government commissioned an independent review of the operation of the FA Act and the FM Act to ensure: that the FM Act is the lead document in fisheries management legislation; Ministerial powers are clearly set out; there is consistency in the precautionary principle as expressed in the FM Act and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999; and that the FM Act is modernised, including updating penalty provisions and references to technology. The review report was provided to the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry for consideration in December 2012. At the time of preparation of this report, the Government had not issued a response to the review.8

AFMA compliance arrangements

7. AFMA’s fisheries management rules and regulations are designed to protect the fisheries resource (that is, fish stocks), the broader marine environment, and the property rights (the Statutory Fishing Rights, fishing licences and quota that have been legitimately applied for by fishers).9 Non compliance can lead to the depletion of fish stocks, environmental damage that may result in the closure of fishing grounds or entire fisheries, and/or reduced community support for the fishing industry. All of these factors may impact on the long-term sustainability of commercial fishing in Commonwealth fisheries.

8. Accordingly, the detection, investigation and enforcement of illegal foreign and domestic fishing activities in Commonwealth fisheries, and subsequent enforcement of penalties for illegal activities, are key AFMA responsibilities under the FM Act.

9. From 1 July 2009, AFMA adopted a centralised model for its Domestic Compliance Program, the subject of this audit.10 Under this model, AFMA plans and delivers the compliance program largely from its Canberra office. The annual budget for the Domestic Compliance Program is around $2.8 million, and includes the following key components:

- compliance intelligence—collection, analysis and reporting of intelligence information to support the compliance function;

- risk assessment and planning—a biennial risk assessment process to assist in the targeted planning of compliance activities;

- communications—education and awareness activities to increase rates of voluntary compliance with fisheries management requirements;

- compliance monitoring—incorporating a planned general deterrence program, targeted activities addressing key identified compliance risks, and special operations to address specific issues or fishing operators; and

- enforcement—seeking to affect a timely and appropriate response to non-compliance.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

10. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Fisheries Management Authority’s administration of its Domestic Fishing Compliance Program. The ANAO assessed the extent to which AFMA has:

- an effective risk management framework, including the use of available intelligence, to identify domestic compliance risks and guide its compliance activities;

- developed and implemented a compliance program that effectively meets its domestic fishing regulatory obligations; and

- appropriate measures to determine whether the Domestic Compliance Fishing Program is meeting its planned objectives.

11. The audit did not include aspects of AFMA’s operations relating to: foreign fishing compliance; licensing services; the setting and administration of levies; and the setting of Total Allowable Catch (TAC) and quota management. In addition, AFMA’s role in establishing the regulatory requirements for the fishing industry was not within the scope of this audit.11

Previous audit coverage

12. In June 2009, the ANAO completed a performance audit that examined AFMA’s regulatory compliance responsibilities in respect of domestic fishing in Commonwealth waters.12 Overall, the 2009 audit found that, while AFMA was managing some aspects of its regulatory functions effectively, there were opportunities for improvement, particularly with regard to quota management, the inspection and enforcement program, and performance reporting.

13. The audit made five recommendations, with four recommendations related to the implementation and monitoring of compliance and enforcement activities. These recommendations were directed towards improving: the quality, consistency and targeting of the general deterrence inspections program; the outcomes of enforcement actions; and compliance intelligence, particularly its contribution to the proposed centralised approach to domestic fishing compliance. The audit also recommended that the Authority develop measurable intermediate outcomes linked to its overall outcome, and expand its reported deliverables to include relevant quantitative performance measures for the Domestic Compliance Program. The current audit examined AFMA’s implementation of the four recommendations related to the delivery of the centralised compliance program.

Overall conclusion

14. AFMA is responsible for the efficient and sustainable management of Commonwealth fish resources on behalf of the Australian community. The Authority’s operating environment includes a large geographic area, with differing management arrangements established for each Commonwealth fishery. Approximately 320 vessels regularly fish in Commonwealth fisheries, landing their catch at up to 75 ports around the country.13

15. The Domestic Compliance Program is a key element of AFMA’s regulatory framework and includes education and awareness activities, a general deterrence inspections program, and targeted risk mitigation activities undertaken by Compliance Risk Management Teams (CRMTs).14 In 2011–12, the Domestic Compliance Program conducted 222 inspections of vessels and fish receivers15, with 32 per cent of vessels fishing in Commonwealth fisheries inspected at least once for that year. Where AFMA detects non compliance, there are a range of enforcement measures currently available under the FM Act. These range from warnings and fines through to prosecution. In addition, administrative sanctions, such as temporary suspension of a fishing licence, are used by AFMA to supplement current legislated enforcement actions.

16. Overall, AFMA has developed and implemented effective arrangements for administering its centralised Domestic Compliance Program. The delivery of targeted compliance activities, aimed at reducing or eliminating key compliance risks, is based on compliance intelligence and a documented risk assessment framework. Compliance activities are effectively planned and delivered in accordance with AFMA’s internal policies and guidelines. Compliance investigations reviewed by the ANAO adhered to the Australian Government Investigations Standards (AGIS), which is a requirement for all public sector agencies conducting investigations. Operating within the available enforcement framework, AFMA’s enforcement actions are guided by internal policies and guidelines, consistently applied and generally recorded appropriately in the Authority’s case management systems.

17. AFMA has also undertaken considerable work to implement the recommendations of the ANAO’s 2009 audit of the Domestic Compliance Program. This work has included: increased resourcing of the compliance intelligence function; development of intelligence reports and analytical tools to support a risk-based compliance approach; and implementation or enhancement of compliance support tools, such as the Vessel Monitoring System (VMS).16 In addition, a new intelligence and case management system has been implemented and guidance materials enhanced to help ensure consistency in enforcement actions.

18. The current audit did, however, identify further scope for strengthening the Domestic Compliance Program. AFMA has recently decided to move from annual to biennial risk assessments to inform the planning of its compliance activities. AFMA’s decision was taken in recognition that the risks had not significantly changed over recent years, and the process was resource intensive. Against this background, it will be important for AFMA to adopt a structured approach to monitoring existing and emerging risks to assess their likelihood and potential consequences, and to implement appropriate mitigation strategies, in the period between biennial risk assessments. Also, the Authority’s measurement and reporting of performance for the Domestic Compliance Program would be enhanced by the development of measures and targets across all key compliance risks and activities, rather than the existing partial coverage. The ANAO has made two recommendations directed towards these areas.

Key findings by Chapter

Collecting and Analysing Compliance Intelligence (Chapter 2)

19. AFMA has significantly enhanced its intelligence capability since 2009, including an expansion of the sources of its intelligence data, an increased ability to share intelligence with other Commonwealth, state and territory agencies, and enhanced analytical capabilities.

20. While AFMA has developed and implemented a number of intelligence initiatives over recent years, the decisions to progress these initiatives were not underpinned by a structured analysis of intelligence capability gaps, or a strategy to implement the initiatives, as recommended in the 2009 audit. During the audit (in August 2012), AFMA prepared a Functional Strategy that outlines current intelligence sources and collection capabilities, and new intelligence analysis methodologies. The development of the Strategy will better position AFMA to adopt a more structured and planned approach to its intelligence function, including identifying and addressing gaps in information gathering and intelligence analysis.

Assessing Risks and Planning Compliance Operations (Chapter 3)

21. AFMA’s Domestic Compliance Program is based on a documented risk assessment and management framework, with the underpinning methodology and risk assessments approved by AFMA’s Senior Executive.

22. In 2012, AFMA moved from annual to biennial risk assessments. This decision was made on the basis that the key risks identified in the 2011–12 risk assessment remained unchanged and that the Authority has a clear understanding of key compliance risks and the likelihood of any change in risk profile.17 While the move to a biennial assessment may achieve efficiencies for AFMA, it is important for the Authority adopt a structured approach to monitoring existing and emerging risks to assess their likelihood and consequences, and implement appropriate mitigation strategies, in the period between biennial risk assessments.

23. AFMA has a well established and comprehensive planning framework for its Domestic Compliance Program. The framework clearly communicates AFMA’s risk-based approach to compliance and the planned compliance activities for each financial year, including general deterrence inspections and Compliance Risk Management Team (CRMT) activities. AFMA has also outlined a range of compliance objectives across a number of key documents, such as the Domestic Compliance and Enforcement Policy and the Corporate Plan. The development of a clear and overarching objective that articulates the purpose of the program would further assist AFMA to coordinate, align and measure the effectiveness of its compliance activities.

24. The effective delivery of AFMA’s planned compliance activities is reliant on an appropriately trained and qualified workforce. AFMA officers are required to obtain specific qualifications and training to perform their roles safely and effectively. AFMA monitors the currency of fisheries officers’ qualifications and their attendance at required training courses through a register, and is developing a broader learning and development strategy. Fisheries officers are also provided with guidelines and standard operating procedures to assist them in fulfilling their responsibilities.

Managing Compliance (Chapter 4)

25. AFMA’s targeted, risk-based program of compliance and enforcement aims to encourage voluntary compliance and deter non-compliance. As previously noted, the Authority implements a range of measures to achieve this, including education and awareness activities, general deterrence inspections program, and targeted compliance risk mitigation activities, including special operations.

26. AFMA’s domestic compliance education and awareness activities are undertaken as part of ongoing compliance activities. These activities are not, however, covered by AFMA’s communications strategy. Further, AFMA does not monitor or assess the effectiveness of its compliance-related education and awareness activities. There would be merit in AFMA updating the current communications strategy to include the activities delivered by the Domestic Compliance Program. Developing a set of measures against which the effectiveness of education and awareness activities can be assessed would further assist AFMA to monitor the effectiveness of its compliance communication activities.

27. General deterrence inspection activities are well planned and conducted in accordance with AFMA’s policies and guidelines. A schedule of general deterrence inspections is developed on a ‘rolling’ two-month basis, taking into account key identified risks and intelligence analysis. Each inspection targets a particular geographic area, which may include a number of ports and fisheries. The ANAO reviewed the planning and reporting for 10 inspection visits conducted in 2011–12, and accompanied AFMA officers on three general deterrence inspection visits, covering four ports and 21 inspections of vessels and fish receivers. The ANAO’s review found that, while each inspection was adequately planned and conducted in accordance with AFMA’s Standard Operating Procedures, there was scope to improve the content and quality of post-inspection reporting.

28. In 2011–12 AFMA conducted a total of 222 inspections, including: 116 in-port vessel inspections; 27 at-sea vessel inspections; and 79 inspections of fish receivers. The number of general deterrence inspections has decreased from 476 in 2008–09, to an average of 236 per year in the three years since the centralised compliance program was implemented. This decrease was anticipated by AFMA and is, in part, due to the increased targeting of inspections. AFMA met its target of conducting inspections on at least three per cent of total landings18, for the previous three years (2009–10 to 2011–12).

29. AFMA has established five CRMTs to target the following key areas of non-compliance: compliance with VMS requirements; fishing or navigating in closed areas; taking in excess of allocated quota and failing to reconcile within the required timeframe; quota evasion; and failure to report interactions with Threatened, Endangered and Protected (TEP) species. Each CRMT has specific objectives and methodologies, which may include information analysis, inspections, and/or special operations, including surveillance of individual vessels or concession holders.

30. Performance measures have been established for all five CRMTs and targets established for three (compliance with VMS requirements, closure breaches and quota reconciliation). To date, there have been positive results achieved from CRMT activities, for example:

- compliance with VMS requirements has increased from 87.5 per cent in 2008–09 to 96.7 per cent in 2011–12;

- activities conducted under the closure breach CRMT, which was established to address the risk of fishing or navigating in closed areas, have resulted in the number of suspected breaches reducing from 17 each month to an average of two each month; and

- the percentage of logbooks returned late to AFMA reduced from 5.5 per cent in 2009 to 1.4 per cent in 2010 (the target was three per cent).

Responding to Non-compliance (Chapter 5)

31. At the time of the audit, the enforcement options available to AFMA when non-compliance was detected ranged from infringement notices through to the referral of offences to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) for prosecution. Since 2009, there has been an overall decline in the number of enforcement actions taken, with AFMA’s approach focusing on higher risk non compliance (as targeted by CRMT activities). For example, in 2008–09, AFMA issued one or more infringement notices for 12 instances of (minor) non-compliance, while in 2011–12 AFMA issued one or more notices on six occasions. In 2008–09, 11 prosecutions were completed, compared to seven prosecutions completed in 2011–12.

32. AFMA has also been exploring the greater use of ‘administrative’ sanctions, such as the temporary suspension of a fishing licence, to supplement current legislated enforcement actions. Since 2009–10, AFMA has suspended 11 fishing licences for periods up to 30 days and ordered eight vessels back to port for non-compliance with licence conditions, such as VMS operation requirements or Seabird Management Plan19 obligations. AFMA considers administrative sanctions to be more immediate and that they provide a greater deterrent for fishers because of their financial impact.

33. AFMA has developed guidelines and standard operating procedures for the conduct of investigations and any subsequent enforcement actions. The ANAO reviewed 80 enforcement actions undertaken between 2009–10 and 2011–¬12 (20 per cent of the enforcement actions completed). This review found that AFMA has made improvements to its case management processes by more comprehensively: documenting key decisions; recording the reasons for these decisions; and ensuring relevant approvals are sought, where necessary. However, there is scope for AFMA to improve the integrity of information retained in its case management system to better capture relevant details of investigation and enforcement activities.

Measuring and Reporting on Compliance Effectiveness (Chapter 6)

34. AFMA’s decision to move to a centralised model for its Domestic Compliance Program was designed to achieve cost savings and greater efficiencies. AFMA has achieved a modest decrease in the budgeted expenditure for the Domestic Compliance Program since 2009, with the budget reduced from approximately $3 million to $2.8 million. However, expenditure on the program now exceeds (by $250 000 in 2011–12) the amount expended on domestic compliance under the previous decentralised model. The primary reason for this increase is because state fisheries agencies did not always expend the compliance budget allocated to them under the decentralised model. Since introducing the centralised model, actual expenditure for the program has closely aligned with the budget.

35. AFMA collects a range of data to measure the effectiveness of aspects of the Domestic Compliance Program, however, the approach to measuring performance was not consistent across all of the key compliance risks. Although performance measures were established for all CRMTs, performance targets had not been developed for the CRMTs addressing quota evasion and Threatened, Endangered and Protected (TEP) species reporting. Further, performance measures or targets had not been established for the general deterrence inspections program or the domestic compliance education and awareness activities. The Authority’s measurement and reporting of performance would be enhanced by the development of performance measures and targets across all key compliance activities.

36. AFMA has established an appropriate reporting framework to communicate information on the Domestic Compliance Program to internal and external stakeholders, comprising: monthly internal reports; Ministerial/Parliamentary Secretary reports; annual reports and a regular newsletter. The absence of performance measures for some compliance activities, and integrity issues with some reported data20, indicates that there is further scope for AFMA to improve its existing data management and reporting arrangements by:

- strengthening data controls and validations processes; and

- providing additional information on program performance to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Domestic Compliance Program in meeting AFMA’s regulatory obligations.

Summary of agency response

37. AFMA’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

AFMA welcomes the ANAO’s overall assessment that AFMA has developed and implemented effective arrangements for administering its centralised Domestic Compliance Program. AFMA also welcomes the ANAO’s acknowledgement that compliance activities are now targeted at reducing or eliminating key risks based on compliance intelligence, risk assessment frameworks and effective planning programs. This ensures delivery of the program is in accordance with AFMA internal policies and guidelines, and that enforcement actions are applied consistently.

AFMA agrees with both of the ANAO’s recommendations and has already begun work, or has incorporated into its planning schedule, activities to implement the changes required to address them. This includes;

- Refining the risk monitoring processes to incorporate a more structured approach whereby information collected through the risk monitoring mechanisms embedded within the compliance program are formally assessed on a quarterly basis.

- Clearly defining program objectives and continuing to pursue the development of measures to assess the effectiveness of the National (Domestic) compliance program and in doing so recognising that it is the overall level of compliance achieved, rather than a quantification of activities, which will determine the success of the program.

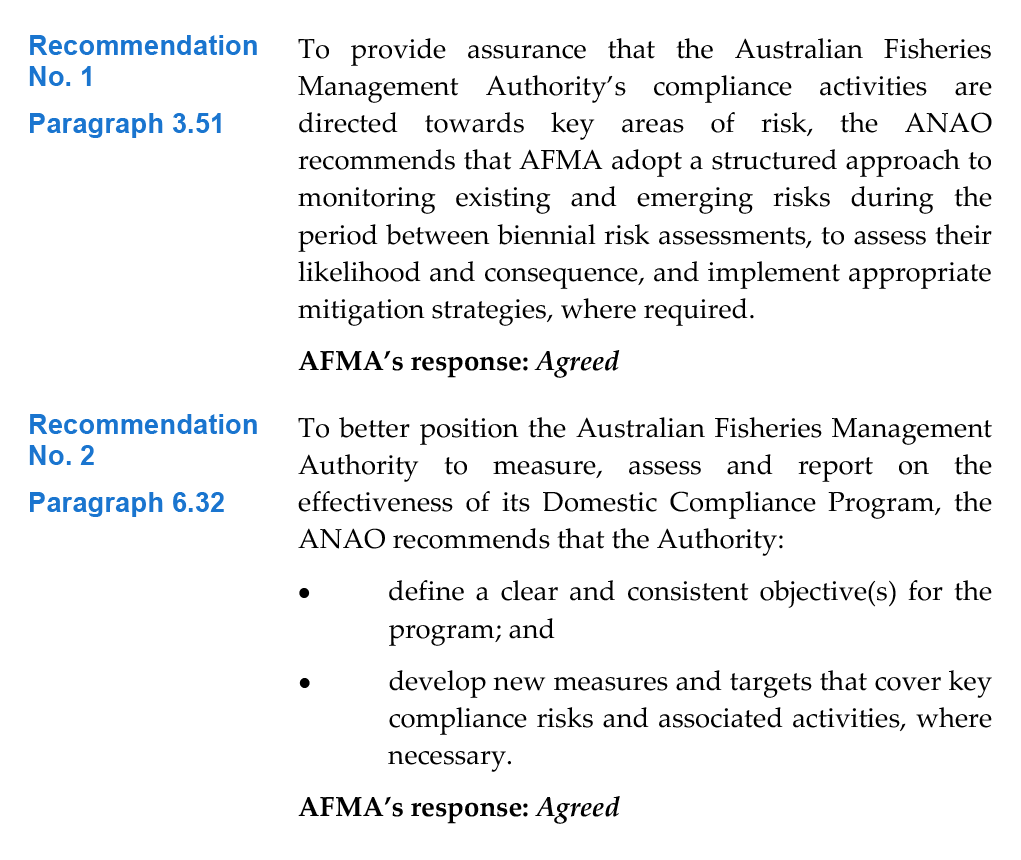

Recommendations

Footnotes

[3] The Australian Fishing Zone was first declared in 1979 and relates only to the use or protection of fisheries. Further information is available from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry’s website <http://www.daff.gov.au/fisheries/domestic/zone> [accessed 13 August 2012].

[4] Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), Australian Fisheries Statistics 2011, December 2012, pp. 1, 2 and 39. Available from: <http://adl.brs.gov.au/data/warehouse/9aam/afstad9aamd003/2011/AustFishStats_2011_v1.1.0.pdf> [accessed 14 January 2013].

[5] Scientific data can be collected by providing observers on domestic and foreign fishing vessels to capture information on the status of fish stocks, fishing catch and effort (referring to the location, time, equipments used and method), bycatch, interactions with Threatened, Endangered and Protected species, and weather.

[6] A fishing licence (also referred to as a concession) is held by a person who has been granted Statutory Fishing Rights or a fishing permit under the FM Act.

[7] In previous years, compliance costs were allocated between the Australian Government and industry, but in 2010 AFMA decided to assume 100 per cent of compliance costs following a review of its Cost Recovery Impact Statement. Available from: <http://www.afma.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/AFMA-Cost-Recovery-Impact-Statement-20101.pdf> [accessed 26 October 2012].

[8] Further information is available from: <http://www.daff.gov.au/fisheries/review-of-fisheries-management-act-1991-and-fisheries-administration-act-1991> [accessed 22 January 2013].

[9] AFMA, Domestic Compliance and Enforcement Program 2011–12, p. 4.

[10] Prior to July 2009, AFMA’s domestic fishing compliance functions were performed under Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with state and territory fisheries agencies. Under these arrangements, state and territory officers conducted the agreed compliance tasks outlined in annual Service Level Agreements.

[11] In August 2012, prompted by a complaint from Mr Andrew Wilkie MP, the Commonwealth Ombudsman announced an investigation into actions undertaken by AFMA in determining the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) for the Small Pelagic Fishery. On 16 January 2013, Mr Wilkie publicly released the Ombudsman’s response which acknowledged AFMA’s admission of the failure of one of its statutory committees to comply with legislative requirements for managing conflicts of interest. In this instance, a committee member with a declared commercial interest in the Small Pelagic Fishery and a concurrent financial interest in a commercial fishing vessel procured for its capability to better exploit any fishing quota (the FV Margiris (later renamed the FV Abel Tasman and referred to as a ‘super trawler’), was allowed to provide input into discussions about the setting of fishing quota but was not allowed to vote on the committee’s final position. The committee’s recommendations are provided to the AFMA Commission, which has responsibility for determining the TAC for this fishery. AFMA advised the Ombudsman of a number of actions that had been undertaken to improve committee governance in response to the Ombudsman’s review.

[12] ANAO Audit Report No. 47 2008–09, Management of Domestic Fishing Compliance.

[13] These figures reflect active vessels and ports as at June 2012. AFMA analysis indicates that 30 ports are the most regularly used for landings.

[14] Compliance Risk Management Teams (CRMTs) involving AFMA compliance and intelligence officers and other relevant Authority staff are formed in response to risks identified in the Domestic Compliance Program biennial risk assessment and prioritised by AFMA for treatment.

[15] Fish receivers are fish processors, wholesalers or retailers who purchase the catch from Commonwealth fishers. A number of Commonwealth Fishery Management Plans require fish receivers to hold a licence as provided for by the FM Act. This allows AFMA to monitor the catch unloaded to these receivers.

[16] All fishing vessels nominated to a Commonwealth fishing licence are required to have a VMS fitted and operating at all times. The VMS includes a Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver and satellite transponder, which transmits information on the vessel’s location to AFMA.

[17] The 2011–12 risk assessment identified the following risks requiring ongoing compliance monitoring and action: compliance with VMS requirements; fishing or navigating in closed areas against regulatory requirements; taking in excess of allocated quota and failing to reconcile within the required timeframe; quota evasion and avoidance; and failure to report interaction/retention of Threatened, Endangered and Protected (TEP) species.

[18] Total landings refers to the number of times vessels within the Commonwealth fleet have unloaded their catch. AFMA informed the ANAO that the three per cent target (previously five per cent under the decentralised model) was set to ensure a minimum presence in the field, within resourcing considerations. In November 2012, AFMA commenced drafting a new program plan for the general deterrence inspections program, including new targets for the inspections program.

[19] AFMA introduced compulsory Seabird Management Plans for the Commonwealth Trawl Sector Fishery (see Figure S1) in October 2011. Each plan aims to minimise the risk to seabirds from fishing activities and require fishers to use specified equipment to deter birds, and to avoid discharging fish processing waste while fishing is underway.

[20] The ANAO’s analysis highlighted discrepancies between AFMA’s internal and external reports. For example, AFMA’s 2010–11 Annual Report indicated that there were 176 vessel inspections undertaken. However, the internal end-of-year report for the Domestic Compliance Program stated there were 163 inspections undertaken. The ANAO also noted differences between the number of compliance activities provided in the internal monthly reports and those included in reports generated by AFMA’s case management system.