Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements by Emergency Management Australia

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of the terms of the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements Ministerial determination.

Summary

Introduction

1. Australia is exposed to natural disasters on a recurring basis. Prime responsibility for the response to a disaster rests with state and territory governments.1 Nevertheless, as natural disasters often result in substantial expenditure by state governments, for many years the Commonwealth has provided financial assistance to the states for recovery and reconstruction activities, as well as to support the provision of urgent assistance to disaster affected communities.

2. In the context of its recent inquiry into natural disaster funding arrangements, the Productivity Commission2 has reported that, over the past decade, the Australian Government has spent around $8 billion on post-disaster relief and recovery. Another $5.7 billion is expected to be spent over the forward estimates for past natural disaster events. This assistance has been principally provided through the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA). NDRRA is a Ministerial determination administered by Emergency Management Australia (EMA) within the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD).

3. In addition, for two states, oversight and accountability measures were introduced in early 2011 to supplement the existing NDRRA arrangements following the widespread flooding that occurred in the eastern states and Queensland tropical cyclones over the 2010–11 Australian spring and summer seasons. These measures were seen as prudent given preliminary estimates had indicated that the Australian Government would need to contribute $5.6 billion to the rebuilding of flood-affected regions, to be funded under NDRRA. The additional measures were reflected in separate National Partnership Agreements (NPAs) signed with the Queensland and Victorian state governments. Of note was that the NPAs enabled the establishment of the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate (the Inspectorate) to undertake reviews of reconstruction projects.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of the terms of the NDRRA Ministerial determination.

5. The audit examined EMA’s administration of the determination, including the provision of guidance to the states on the NDRRA framework, and its claims verification and assurance activities. The ANAO’s audit work was also informed by examination of a selection of NDRRA claims made by three states (Western Australia, Victoria and New South Wales) in respect to seven disaster events covering a range of disaster types and sizes. The relevant disasters had occurred between 2006 and 2011, with the associated NDRRA reimbursement claims being some of the more recent available for examination (the claims were lodged with EMA between 2008 and 2014).3 The ANAO’s performance audit work was also informed by a recent performance audit of the Inspectorate’s value for money reviews of Queensland reconstruction projects.4

6. The audit criteria were primarily based on the aim of the NDRRA, the principles for assistance to states, and the various definitions, conditions, requirements and other provisions set out in the determination and associated guidelines.

Overall conclusion

7. The Commonwealth plays a major role in providing financial and other assistance to help alleviate the burden on states and to support the provision of urgent assistance to disaster affected communities. Under the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA), the Commonwealth reimburses up to 75 per cent of the state recovery bill after certain thresholds are met. The majority of NDRRA expenditure is used to provide partial reimbursement to states for rebuilding essential public assets, in particular roads and road infrastructure. NDRRA generally operates on a reimbursement basis, with the Australian Government having little oversight of reconstruction as it occurs as there is no reporting from the states until such time as they seek reimbursement, which is commonly some years after disasters occur.

8. The NDRRA determination sets out the types of expenditure that are eligible for Australian Government reimbursement, as well as establishing various conditions and limits on the financial assistance that will be provided. In its administration of NDRRA, Emergency Management Australia (EMA) has placed significant reliance on the framework being well understood and complied with by state coordinating agencies, jurisdiction auditors and state delivery agencies and councils who undertake recovery and reconstruction work. This reliance has not been well placed given:

- there remains significant gaps in the extent to which key terms and conditions in the determination have been adequately defined and explained, notwithstanding that some additional guidance has been provided by EMA in recent years5; and

- limited oversight at the conclusion of reconstruction is afforded to the audited claims submitted by states, with no project level information provided in these claims.

9. Overall, EMA has not been alert to clear signals that the NDRRA framework has required tightening. Its claims verification and assurance processes have also not adequately protected the Commonwealth’s interests, including by placing too much reliance on state vetting and sign-offs.6 The result has been millions of dollars of ineligible claims being reimbursed to the states at the Commonwealth’s expense.7 A much more active and disciplined approach to EMA’s administration of NDRRA is required so that payments are limited to those items the Australian Government intended to cover, given the significant quantum of funding that is involved.

10. EMA has been reluctant to accept criticism of its approaches. Of note is that EMA did not agree with the finding of a February 2013 internal audit that there were ‘significant weaknesses’ in departmental processes for claims verification and assurance. Instead, EMA opined that its existing approach provides ‘a substantial level of assurance’. Further, notwithstanding that internal audit had identified that the shortcomings in the NDRRA framework ‘inhibits the ability of jurisdiction auditors to develop measurable audit criteria’, EMA has advised the ANAO that it is ‘reasonable and appropriate’ for it to continue to rely on state ‘vetting’ of expenditure claims and associated audit sign-offs. This advice was provided notwithstanding this audit identifying various instances of ineligible expenditure claims that had been paid by EMA.

11. A key message from this audit is that improvements in administrative effectiveness, including savings in NDRRA expenditure, can be expected if EMA took more timely and effective action to improve upon longstanding administrative approaches. A positive move in this direction involved EMA obtaining, in July 2014, a report from internal audit to support the development of a compliance assurance framework for NDRRA. However, it remains noteworthy that EMA has not yet made any use of the power it was given in 2012 to undertake project-level assurance activities either before reconstruction work is completed, or after expenditure claims have been submitted. In this respect, the ANAO’s earlier audit of the Inspectorate’s review of Queensland reconstruction projects had concluded that:

The experience to date of the project level scrutiny provided by the Inspectorate and the Taskforce (which have identified potential reductions in NDRRA claims from Queensland totalling more than $100 million) is likely to be beneficial in informing the approach adopted by EMA in its ongoing administration of NDRRA in respect to natural disasters that occur in other states and territories. It also underlines for other Commonwealth agencies the potential benefits of closely considering arrangements for assuring information provided by the states and territories, where this information determines the amount of Commonwealth payments.

12. Against this background, the ANAO has made two recommendations. The first is focused on the development of a more robust framework to govern the provision of financial assistance under NDRRA. The second is aimed at stronger controls being implemented by EMA to increase the level of assurance over the veracity of NDRRA payments to the states.

Key findings by chapter

NDRRA Framework (Chapter 2)

13. The NDRRA framework comprises the Ministerial determination, Schedule 1, six attachments and 10 guidelines. This framework defines those natural disasters that are covered, and identifies those measures that are eligible for funding.

14. The framework that is in place to support the delivery of NDRRA funding is inadequate in a number of important respects. Of note is that EMA has not acted sufficiently promptly to address deficiencies in the guidance available for state, territory and local governments involved in administering or delivering NDRRA assistance.8 This has resulted in varying interpretations of NDRRA eligibility requirements by state agencies and incorrect claims being submitted to EMA and paid.

15. Inadequacies in the NDRRA framework have also been raised by the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate, in light of the findings of its review of a sample of Queensland reconstruction projects. The Inspectorate has reported that the NDRRA framework would benefit from ‘better defined eligibility criteria’ and also that the ‘current procedures are often vague, inconsistent and complicated’. Similarly, comments on the NDRRA framework from states examined by the ANAO as part of this audit included that it is ‘complex and ambiguous’ and, while recently issued guidance from EMA has been welcomed, there remains ‘uncertainty about the interpretation of NDRRA Determinations’.

16. The inadequacies in the NDRRA framework have been reflected in varying interpretations of NDRRA across and within the sampled states. It has also been reflected in states claiming, and EMA making payment for, expenditure that is not eligible under NDRRA. In this respect, EMA’s submission to the recent Productivity Commission inquiry acknowledged that there has been some shifting of states’ operational disaster response costs to the Commonwealth because ‘a much broader range of state and territory pre-deployment and response costs have been covered under the NDRRA than was originally envisaged’. Similarly:

- the Inspectorate has identified ‘systemic eligibility issues in road construction projects’ in Queensland;

- the National Commission of Audit raised concerns about the extent to which state and local governments have been upgrading their assets using Commonwealth NDRRA funds; and

- in each of the three states examined by the ANAO as part of this audit, EMA has paid claims for expenditure that were not eligible under NDRRA.

17. EMA has had little visibility over these matters given the small amount of information it obtains from states before paying NDRRA claims. It has also approved payments notwithstanding that information in its possession at the time of assessment shows the claim is not consistent with the NDRRA determination.

Claims Verification and Assurance (Chapter 3)

18. The NDRRA determination provides for two types of NDRRA claims to be made: general claims and audited claims. A general claim is unaudited and may include estimates of expenditure. An audited claim is required to be based on actual expenditure. The significant majority of NDRRA claims involved audited claims. Accordingly, NDRRA generally operates on a reimbursement basis.

19. There are three basic principles that limit the Commonwealth assistance to states to the partial reimbursement for ‘state expenditure’ on ‘natural disasters’. Specifically: the expenditure must be on ‘eligible measures’; the expenditure must meet certain financial requirements (such as being above set thresholds); and other conditions set out in the determination must also be met.

20. For some time the work of the Inspectorate has been drawing attention to ineligible activities being included in Queensland reconstruction activities. More broadly, a February 2013 internal audit report concluded that there were ‘significant weaknesses’ in EMA’s processes for verifying and paying NDRRA claims. EMA did not agree with this conclusion. Instead, it opined that the ‘existing arrangements provide a substantial level of assurance’. The ANAO’s analysis is that this is not the case.

21. In this context, EMA’s claims processing approach places significant reliance on states accurately calculating the amounts to be claimed, with the associated provision of an audited financial statement. However:

- as outlined at paragraphs 14 to 16, the NDRRA governance framework does not promote understanding of, and compliance with, the NDRRA determination. This inhibits the ability of the states, and their auditors, to prepare claims that only include expenditure that is eligible for reimbursement;

- the NDRRA claim forms provide EMA with little in the way of useful information for claims analysis. For example, they do not require the states to provide any project level information. Instead, the department places significant weight on the audited high level information submitted by the states notwithstanding that the shortcomings in the framework inhibits the ability of state auditors to develop measurable audit criteria; and

- there are no requirements specified in relation to the records that are required to exist before a NDRRA claim is made, or the records that are to be maintained in support of a claim that has been made. In this respect, it was common for there to be long delays in state delivery agencies and councils being able to provide the ANAO with information to support amounts they had claimed under NDRRA, or for them to be unable to produce any supporting documentation for the amounts they had claimed.

22. Significant benefits, including reducing the extent to which payments are being made for ineligible expenditure, can be expected from EMA implementing improved oversight and assurance arrangements for NDRRA claims. Specifically:

- obtaining more detailed information from the states on the expenditure that has been submitted for reimbursement before claims are paid, or of estimates where payments are made on that basis; and

- implementing a risk-based approach to examining the eligibility and value for money of a sample of recovery and reconstruction projects. The power to undertake assurance activities was provided to EMA in December 2012, but has not yet been used.

23. Each of the Productivity Commission’s proposed natural disaster funding reform options involve a move from reimbursement of actual expenditure on the reconstruction of essential public assets to payments based on damage assessments and estimates of the cost of reconstruction made soon after a disaster. In this respect, the work of the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate has been largely based on examining the estimated cost of approved reconstruction projects, rather than expenditure on completed works. In this context, even if NDRRA moves to payments based on project damage assessments and cost estimates, significant benefits can be expected from EMA obtaining more detailed claims information and implementing a risk-based program of assurance activities.

Summary of agency responses

24. The proposed report was provided to the Attorney-General’s Department; the Department of the Treasury; and the Chair of the Inspectorate, as these Australian Government entities have various roles and responsibilities associated with NDRRA. Extracts of the report were also provided to four state departments and agencies and two Local Government Authorities (LGAs) in NSW; six state departments and agencies and two LGAs in Victoria; and three state departments and agencies and six LGAs in Western Australia, as references to these entities are included in the report.

25. Formal comments on the proposed report were provided by the Attorney-General’s Department and the Chair of the Inspectorate, and are included in full in Appendix 1. A summary of the Attorney-General’s Department’s comments is also included below. Formal comments on the proposed report were also provided by the NSW Treasury; Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance; Wellington Shire Council (Victoria); and Western Australian Department of Premier and Cabinet. These are also included at Appendix 2.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response

26. Over the last 40 years, the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) has provided states and territories with the autonomy and flexibility to decide the level and means of recovery support, which appropriately facilitated quick implementation of recovery strategies by providing certainty around the level of Australian Government support that would be available. However, the increase in the Australian Government’s liability of around $10 billion since 2010–11, has led to the implementation of more onerous administrative practices to obtain greater fiscal transparency, address ineligible claims and appropriately contain costs. The result has been reduced state autonomy to manage their constitutional responsibilities, and overly-complex NDRRA administration.

27. The Attorney-General’s Department (‘the department’) agrees the Australian National Audit Office’s recommendation 1(a) noting the department has been implementing arrangements in line with this recommendation over the last two years. A decision to implement recommendations 1(b) and 2 would require extensive consultation between governments. These recommendations represent the governance arrangements in place under between (sic) the Commonwealth and Queensland Government National Partnership Agreement for reconstruction and recovery, which has been at a cost to the Australian Government of approximately $10 million and to the Queensland Government of over $95 million.

28. The department is taking immediate action to decrease the risk of ineligible expenditure being erroneously included in state claims by re-writing the 2012 NDRRA determination. The department will also examine alternative compliance options to those proposed by the ANAO, which will be considered by Government together with the ANAO’s recommendations.

ANAO comment

29. The ANAO does not recommend adopting the Queensland or Victorian oversight arrangements or introducing new or amended NPAs. Recommendation 2(b) proposes a risk-based approach to examining a sample of recovery and reconstruction projects. Any project-level scrutiny by AGD would be a significant improvement over the department’s current approach, but would still involve significantly less scrutiny than is being applied by either the:

- Queensland Reconstruction Authority, which reviews all project submissions from local government and state delivery agencies for eligibility and/or value for money, as part of its progressive review of projects as they proceed from initial estimates to delivery and acquittal; or

- the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate, which uses a Cumulative Monetary Amount sampling methodology to examine a selection of projects using a three-tiered review process.9

30. The department already has the authority to implement the ANAO’s recommendations under clauses 6.6 and 6.8 of the current Determination (see paragraph 3.14). The audit notes the reported benefits that have been attributed to conducting project-level scrutiny of NDRRA claimed expenditures (for example, see paragraphs 3.6 and 3.7). The audit report also demonstrates that, despite a relatively modest ANAO sample and considerable constraints on the quality and quantity of information voluntarily made available by states, there are indications of widespread NDRRA over claiming.

31. The department has not advised the source or context for its cited costs of the NPA to the Australian and Queensland Governments. However, by way of comparison, the Queensland Reconstruction Authority has reported that, as at August 2014, the oversight arrangements established by the NPA between the Commonwealth and Queensland have resulted in $4.6 billion in rejected or withdrawn claims10 in that state alone.

32. The Attorney-General’s Department is responsible for administering NDRRA consistent with the Ministerial Determination. The audit demonstrates that a much more active role is required on the department’s part to protect the Commonwealth’s interests, with any costs of additional scrutiny likely to be more than repaid through reduced payments on items not eligible under the Determination.

Recommendations

Set out below are the ANAO’s recommendations and the Attorney-General’s Department’s abbreviated responses. More detailed responses are shown in the body of the report immediately after each recommendation.

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.75 |

The ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department significantly improve the administration of disaster relief and recovery funding by:

Response: (a) Agreed. (b) Agreed with qualification. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.70 |

To provide improved oversight and assurance in its administration of the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements, the ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department:

Response: (a) Agreed with qualification. (b) Agreed with qualification. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the assistance provided by the Australian Government under the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA). It also sets out the audit objectives, scope and criteria.

Background

1.1 Australia is exposed to a wide variety of natural hazards. Natural hazards become natural disasters when they have a significant and negative impact on the community.

1.2 Over the past 40 years, storms have been the most frequent disasters causing insured property losses.11 Floods have also been frequent as well as typically being the most expensive form of natural disaster. Bushfires have been less frequent, but have accounted for most fatalities.

Australian Government financial assistance to states

1.3 Prime responsibility for the response to a disaster rests with state and territory governments.12 Nevertheless, as natural disasters often result in substantial expenditure by state governments in the form of disaster relief and recovery payments and infrastructure restoration, the Commonwealth has established arrangements to provide financial assistance to the states in certain circumstances. The key mechanism for providing financial assistance is through the NDRRA.13

1.4 Responsibility for administering NDRRA was transferred from the former Department of Transport and Regional Services to the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) on 24 January 2008. In this context, the National Disaster Recovery Programs Branch (NDRPB) within Emergency Management Australia (EMA) has some 22 full time equivalent staff and an annual budget of approximately $2.9 million.

Productivity Commission review

1.5 In December 2013, the Government announced its intention to establish a Productivity Commission inquiry into natural disaster funding arrangements in support of the Council of Australian Governments’ national policy shift from a natural disaster response and recovery focus to proactively building disaster resilience. Accordingly, on 28 April 2014, the Productivity Commission (the Commission) was asked by the Treasurer to undertake a public inquiry into the efficacy of current national natural disaster funding arrangements, taking into account the priority of effective natural disaster mitigation and the reduction in the impact of disasters on communities.

1.6 The Commission’s draft report was released on 25 September 2014. It proposed a major restructure of Australian Government funding for natural disasters. Its key findings included that:

- the current funding arrangements are not efficient, equitable or sustainable as well as being ‘prone to cost shifting, ad hoc responses and short-term political opportunism’;

- the evolution of the funding arrangements ‘can be characterised by growing generosity by the Australian Government during the previous decade, followed by a swing to constrain costs and increase oversight after the recent concentrated spate of costly disasters’; and

- governments generally overinvest in post-disaster reconstruction, and under invest in mitigation that would limit the impact of natural disasters in the first place such that ‘natural disaster costs have become a growing, unfunded liability for governments, especially the Australian Government’.

1.7 The Commission concluded that NDRRA dilutes the link between asset ownership, risk ownership and funding, providing a financial disincentive for state and local governments to invest in mitigation or insurance. It further concluded that financial support to the states for natural disaster relief and recovery be reduced14 while mitigation funding be increased (from about $40 million to $200 million annually) to encourage governments to manage natural disaster risks more sustainably and equitably. Consequentially, the Commission’s draft recommendations included that the amount of post-disaster financial support provided by the Australian Government be reduced by:

- decreasing the marginal cost sharing rate from 75 per cent to 50 per cent; and

- increasing the trigger amounts at which assistance is provided (both the small disaster criterion15 and the annual expenditure threshold16).

1.8 Each of the Productivity Commission’s proposed natural disaster funding reform options involve a move from reimbursement of actual expenditure on the reconstruction of essential public assets to payments based on damage assessments and estimates of the cost of reconstruction made soon after a disaster.

1.9 The final report was presented to the Australian Government in mid-December 2014. In February 2015, AGD advised the ANAO that the Government will release its response to the final report by the end of May 2015.

ANAO audit activity

Related audits

1.10 The ANAO has undertaken three audits of key aspects of the National Partnership Agreements (NPAs) signed with Queensland and Victoria in relation to natural disasters over the 2010–11 Australian spring and summer seasons.

1.11 The objective of the first audit (ANAO Audit Report No.24 2012–13) was to assess the extent to which the disaster recovery work plans for Queensland and Victoria were prepared, and appropriate monitoring reports provided, in accordance with the relevant NPA. In the context that the Australian Government will meet up to 75 per cent of eligible reconstruction expenditure, the second and third audits (ANAO Audit Report No.23 2012–13 and ANAO Audit Report No.8 2013–14) assessed the effectiveness of the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate, supported by the National Disaster Recovery Taskforce17, in providing assurance that value for money is being achieved in recovery and reconstruction expenditure in Victoria and Queensland respectively.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.12 The objective of this current audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of the terms of the NDRRA Ministerial determination.

1.13 The audit examined EMA’s administration of the determination, including through analysis of a selection of NDRRA claims made by three states (Western Australia, Victoria and New South Wales) in respect to seven disaster events covering a range of disaster types and sizes, as reflected in terms of the overall costs claimed and the numbers and geographic spread of affected areas. The relevant disasters had occurred between 2006 and 2011, with the associated NDRRA reimbursement claims being some of the more recent available for examination (the claims were lodged with EMA between 2008 and 2014).18 The audit criteria were primarily based on the aim of the Arrangements, the principles for assistance to states, and the various definitions, conditions, requirements and other provisions set out in the determination and guidelines.

1.14 The audit of EMA was conducted under section 18 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). The ANAO had planned that the audit also consider the performance of a sample of states, pursuant to section 18B of the Act (which empowers the ANAO to conduct a performance audit of a Commonwealth partner). The three sampled states were New South Wales (NSW), Victoria and Western Australia. However, the relevant central agencies in NSW and Victoria informed the ANAO that they had doubts about the applicability of section 18B of the Act to state expenditures incurred under NDRRA, but each agreed to relevant state agencies participating voluntarily in the audit.

1.15 Legal advice obtained by the ANAO in respect to the matters raised by NSW and Victoria was that there was some doubt that section 18B empowered the ANAO to audit a state’s NDRRA activities to the extent that the activities are funded by reimbursements by the Commonwealth where the payment is made only with respect to past expenditure (which is the case in relation to the majority of NDRRA claims for all states excluding Queensland). Accordingly, the audit conclusions are directed to the performance of Commonwealth agencies and not state agencies (Commonwealth partners), drawing on information provided voluntarily by the states.

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $765 000.

Report structure

1.17 The audit findings are reported in the following chapters.

|

Chapter |

Chapter overview |

|

2. Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements Framework |

Examines the NDRRA framework and outlines its operation. |

|

3. Claims Verification and Assurance |

Examines whether claims for NDRRA funding are consistent with the Ministerial Determination. |

2. Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements Framework

This chapter examines the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) framework and outlines its operation.

Background

2.1 NDRRA is a Commonwealth ministerial determination. NDRRA assistance takes account of a state’s capacity to fund disaster recovery and is usually in the form of partial reimbursement of actual state expenditure. Advance payments are also sometimes provided. States are required to provide audited financial statements to acquit expenditure, including expenditure of advance payments, and repay to the Commonwealth amounts not properly spent.

2.2 The determination defines those natural disasters that are covered by NDRRA, and identifies those measures that are eligible for NDRRA funding. Subject to administrative rules set out in the determination, upon notification of the natural disaster to the Secretary of the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department by the affected state, Commonwealth assistance will be provided in respect to eligible measures. In this context, there are four categories of assistance:

- Category A – emergency assistance provided to individuals;

- Category B – restoration or replacement of essential public assets, concessional loans and counter disaster operations (CDOs);

- Category C – community recovery packages for community facilities and/or clean-up and recovery grants for small businesses and primary producers; and

- Category D – exceptional circumstances assistance.

2.3 NDRRA generally operates on a reimbursement basis. There are three basic principles that limit the assistance to states to the partial reimbursement for ‘state expenditure’ on ‘natural disasters’: the expenditure must be on ‘eligible measures’; the expenditure must meet certain financial requirements; and the ‘state’ must meet other conditions set out in the determination.

2.4 The determination provides for two types of NDRRA claims to be made: general claims and audited claims. A general claim is unaudited and may include estimates of expenditure. An audited claim is required to be based on actual expenditure. The significant majority of NDRRA claims involved audited claims.19

2.5 The claim and acquittal form; expenditure breakdown form; and a prescribed format for the independent audit report are provided as attachments to the determination.20 Time limits apply to the submission of claims and acquittals, with provision for extensions to be requested by states.

2.6 The ANAO examined:

- revisions and updates to the determination;

- the NDRRA guidelines and advisories;

- the framework for meeting costs relating to the restoration or replacement of essential public assets;

- the practice of claiming costs relating to ‘Day Labour’;

- the interaction of state guidelines with NDRRA;

- disaster notification and registration;

- state acknowledgement of Commonwealth assistance; and

- post disaster assessment reporting.

Revisions and updates to the determination

2.7 The NDRRA framework comprises the ministerial determination, Schedule 1, six attachments and 10 guidelines.21 These documents are publicly available on the ‘Disaster Assist’ website.22 A ‘Companion Guide’ that was intended to ‘simplify and improve the usability of the determination’ was to be completed by December 2009. More than five years later it is still an incomplete draft that does not achieve this stated intention.

2.8 In January 2014, EMA advised the ANAO that its guidelines and advisories have been issued ‘in place of issuing a companion guide’. However, none of the 10 guidelines individually or collectively could be characterised as simplifying the Determination. Further, the advisories have not been published on the website. In addition:

- the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance commented to the ANAO that EMA guidance on the claiming of Counter Disaster Operations (CDOs) does not fully clarify eligibility matters and that other guidance ‘remains unclear’, ‘making it difficult for the state and for VicRoads to assess expenditure accurately’ (see further at paragraphs 2.17 to 2.23). The ANAO was further advised that:

Following significant natural disasters in recent years, all states have actively encouraged the Commonwealth to provide a better understanding of what local councils and states can undertake when seeking to repair, reinstate and ‘better’ damaged essential public assets.

- NSW Treasury described NDRRA as ‘complex and ambiguous’ and further commented to the ANAO that there is ‘uncertainty about the interpretation of NDRRA Determinations’ and ‘while NSW acknowledges the usefulness of recently released EMA advisories supporting Determination 2012, states have been obliged to develop guidelines on interpretation of the NDRRA’;

- state-based approaches to providing NDRRA interpretations and guidance has led to inconsistent approaches, including WA employing a different (and incorrect) accounting approach in respect to claims examined by the ANAO (see further at paragraphs 3.61 to 3.65); and

- as illustrated by various examples discussed in this ANAO audit report, as well as other instances identified by the ANAO in the course of this audit, claims for expenditure ineligible under NDRRA have been made across each of the three sampled states. This is a similar situation to that identified by the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate in respect to Queensland.

Timing of determination changes

2.9 Ideally, changes to the Arrangements should be aligned to financial years, since this is the basis for the claims submitted by states. Traditionally this had been the case, in that the eight determinations reissued between 1988 and 2004 all took effect from 1 July of the relevant year of issue. A particular advantage of this timing was that states were well aware of any changes before they came into effect on 1 July and therefore did not need to absorb changes or divert attention from their response and recovery efforts during the ‘disaster season’ (which typically occurs between November and April).

2.10 The last four determinations were issued on 22 March 2006, 21 February 2007, 21 March 2011 and 18 December 2012 respectively, which from the states’ perspective are all in the midst of the disaster season. As these determinations are effective from the date of signature, depending on the extent of the changes, this complicates eligibility assessments, as delivery agencies, state NDRRA administrators and EMA staff are effectively dealing with two sets of requirements for one financial year.

2.11 In November 2013, the NSW Audit Office found it necessary to contact EMA in order to ascertain the date of effect of the current determination. Accordingly, it would be of benefit if the Disaster Assist website included the signed and dated determinations.

NDRRA guidelines and advisories

2.12 Clause 8.1 of the determination provides that the Secretary of AGD may issue guidelines from time to time to provide clarification of the interpretation and administration of the determination; and to provide assistance and guidance on the forms and procedures to be adopted by states for obtaining payments made under the determination. As indicated in paragraph 2.7, there are currently 10 guidelines posted on the Disaster Assist website.

2.13 In March 2013, EMA advised the AGD Audit Committee that the ‘current guidelines are appropriate for the majority of NDRRA claims and expenditure’ and that it would ‘finalise and formalise NDRRA policies and procedures by 30 September 2013’. However, a number of submissions to the Productivity Commission review raised concerns about a lack of clarity concerning NDRRA funding rules. For example, the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate submitted that there is a lack of clarity around eligibility criteria, the guidelines lack definition in relation to eligibility of costs for reimbursement and that NDRRA is at risk of not being applied consistently. Similarly, in its seventh report, provided to the Prime Minister in December 2013, the Inspectorate had highlighted that:

- the NDRRA framework would benefit from ‘better defined eligibility criteria’ and the ‘current procedures are often vague, inconsistent and complicated’; and

- one of the key challenges faced has been the varying interpretations of NDRRA by state agencies. Under NDRRA, the devolved approach risks the inconsistent interpretation of key terms, and has resulted in instances where reconstruction has extended beyond the replacement of what was originally there at a significantly increased cost to the Commonwealth.

2.14 Similarly, the Inspectorate’s eighth report provided to the Prime Minister in September 2014 outlined that many of its specific observations remained unchanged since the seventh report, including ‘a need to clarify some important programme parameters, simplify processes and define eligibility criteria.’ In this respect, in January 2014, AGD had advised the ANAO that:

… the Department is … continuing to deliver important, low cost improvements to its administration of NDRRA, such as developing formal eligibility advice to provide better guidance to Australian Government agencies, the states and state auditors-general in interpreting the intent of NDRRA and executing their responsibilities.

2.15 However, although some progress has been made, formalising such advice has largely not yet occurred. In this respect, EMA has been slow to issue ‘draft’ guidance and after considerable elapsed time has still not finalised and formalised much of this material. For example, a 2005 review of the Arrangements identified the need for the development of ‘NDRA Eligible Measures Specifications’, which were essentially intended to be ‘a detailed list of eligible measures’. This had not occurred by August 2009 and was again identified at that time as an important need. However, nine years have passed since the 2005 review but this matter remains outstanding, as reflected in a recommendation of the Finance Insurance Review.23

2.16 Further in this respect, the first six ‘Eligibility advices’ issued by EMA were due for completion by 30 September 2013. However, these were not provided to the NDRRA Stakeholders Group (NSG)24 until April 2014. With one exception, to date these documents have not been published on the Disaster Assist website.

2.17 One of these advices was in relation to CDOs25, which were introduced in the 2007 Determination. However, there is no definition of CDOs within the determination. The NSG meeting held on 4 August 2009 identified that a definition and eligibility guidance was required. It was not until some five years later (and more than seven years after CDOs became an eligible measure) that a guideline was finalised and issued by EMA (in October 2014).

2.18 EMA is aware that states have adopted their own interpretations of the provisions and that this has resulted, for example, in the shifting of the states’ operational disaster response costs to the Commonwealth. In this regard, AGD publicly acknowledged in its submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry that:

Over time, a much broader range of state and territory pre-deployment and response costs26 have been covered under the NDRRA than was originally envisaged. Some of these costs, such as aerial firefighting costs, are already subject to separate Australian Government cost-sharing arrangements.

2.19 However, EMA reimbursed these costs, with claims examined by the ANAO also including, for example:

- over $7.3 million claimed as CDOs by 14 Local Government Authorities (LGAs) in relation to the severe thunderstorms that crossed the Wheat Belt region of Western Australia on 29 January 2011. Twenty shires were declared as affected by this event, ranging from the Shire of Perenjori in the north, to the Shire of West Arthur in the south. [AGRN 427]. For example, the Shire of Cuballing claimed $821 286, primarily for tree clean-up work on low-trafficked rural access roads. While the affected roads were opened to traffic within days of the storm event (work which is intended to be eligible under NDRRA as CDOs)27, the bulk of the shire’s claim related to removing fallen tree debris on roadside verges long after the event occurred (see Figure 2.1). This work commenced in July 2011 (some five months after the storm impacted the region) and continued until March 2012. As such, most of the work claimed could not be considered to have been undertaken on an urgent basis, in ‘public urban areas’; and could not reasonably be expected to reduce the need to provide emergency assistance to individuals. 28

Figure 2.1: Tree debris pushed to side of the road, Shire of Cuballing, Western Australia

Source: Shire of Cuballing.

- among the 12 shires declared by Western Australia as affected when the Gascoyne river catchment area experienced substantial flooding as a result of a monsoonal low in mid-December 2010 (the Carnarvon flood) [AGRN 418], $742 412 was claimed by the Shire of Carnarvon as CDOs to assist individuals (under Category A). This included over $60 000 for a building appraisal project, conducted over the period from mid-February 2011 to June 2011, with the purpose of inspecting 174 properties ‘to determine the number and status of all buildings on the property’. The June 2011 report found a large percentage of unapproved buildings that were non-compliant with the current requirements of the Building Code of Australia. Of 289 houses inspected, 102 houses were below the 1-in-100 year flood line and many of the houses did not have ‘sanitary conveniences’. Some years before the flood the council changed its regulations such that each septic system was required to have two leach drains. Most of the 73 leach drains installed by council and for which the costs were included in the NDRRA claim appear to be for the purpose of meeting this requirement, rather than as a result of damage caused by the flood. Council also paid for the installation of 42 new septic tanks (there was no evidence provided that these were replacing tanks washed away). The claimed cost of the septics and leach drains installed was over $280 000. The available evidence was that Council organised the installations because septic systems did not exist or residents had ‘unapproved’, inadequate, makeshift and poorly sited septic systems. Accordingly, it was not evident that all of the claimed expenditure had been incurred on alleviating individuals’ personal hardship or distress arising as a direct result of the declared natural disaster event; and

- in respect to the Gippsland Flood that occurred in June 2007 [AGRN 278], Victoria made a Category A CDOs claim which included $95 000 for the construction of levee banks to protect residential properties at Narracan Creek in the Latrobe LGA. However, the supporting documentation provided to the ANAO by the Victorian Department of State Development, Business and Innovation showed that this expenditure was incurred on a flood warning system installed in April 2008.29

2.20 In February 2015, the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) acknowledged that the amount pertaining to the activity at Narracan Creek was intended as a mitigation project and therefore should not have been claimed for NDRRA reimbursement.

2.21 As indicated at paragraph 2.17, guidance on CDOs was issued by EMA in October 2014. Guideline 10 now provides some examples of the types of CDOs that may be eligible for NDRRA reimbursement. States are also now required to demonstrate the extraordinary nature of the events being claimed. In this regard, state and local governments must now be able to prove the extraordinary nature of the costs and that their existing human, capital and financial resources are unable to meet the demands of responding to a disaster or disasters. Importantly, states must now be able to demonstrate that the extraordinary CDOs undertaken were intended to reduce Category A assistance being provided. Further, the guideline places responsibility on the state or local governments to clearly differentiate NDRRA-eligible costs from other costs (which are not eligible and therefore to be covered within the state or local government’s resource capacity). An attachment to the guideline also lists some 22 activities that states have been claiming as CDOs which EMA recommends be categorised against a different clause or measure under NDRRA.30

2.22 In January 2015, EMA commented in respect to the ANAO’s analysis of NDRRA guidelines and advisories that:

It is incorrect to suggest there is a lack of clarity and formality with respect to NDRRA guidelines and it is inaccurate to conclude that in more recent years EMA has been slow to issue guidelines.

2.23 However, in addition to being at odds with the ANAO’s analysis, EMA’s perspective was not shared by state and local councils in their comments to the ANAO. For example, in February 2015, the Victorian DTF advised the ANAO that:

DTF notes that while the development of this guidance [on CDOs] is helpful, it still does not fully clarify what costs are eligible or ineligible regarding those activities undertaken to protect the general public.

Other guidance for Plant and Equipment also remains unclear, making it difficult for the State and VicRoads to assess expenditure accurately.

2.24 A common response by EMA to the issues raised by this ANAO performance audit was to advise the ANAO that:

The state is responsible for vetting local and state government expenditure to ensure it complies with the NDRRA. State government officials, along with state auditors-general, attest to the eligibility of expenditure claimed from the Australian Government under NDRRA. It is reasonable and appropriate for the Government to rely on the integrity of state audit office practices and findings.

2.25 However, an approach that involves EMA placing ‘significant trust’ in the abovementioned certifications and sign-offs from the states is not sound where guidance is lacking or insufficiently clear. In addition to the ANAO’s analysis, EMA’s view that there is sufficient clarity in relation to NDRRA guidance is at odds with the findings publicly reported by the Australian Government Reconstruction Inspectorate, various submissions to the Productivity Commission review and specific comments provided to the ANAO by state entities and councils. Further, a July 2014 report prepared by the firm contracted as AGD’s internal auditor outlined that ‘there are a number of principles and measures under the determination that remain open to interpretation and that have not been defined or demonstrated’. The report provided to EMA by the internal audit firm stated that this situation ‘inhibits the ability of jurisdiction auditors to develop measurable audit criteria’.

Restoration or replacement of essential public assets

2.26 In its fifth report to the Prime Minister, the Inspectorate observed that it is up to each state to determine what it considers to be ‘an essential public asset’ in accordance with the NDRRA determination. The Inspectorate noted that this can lead to inconsistent application of NDRRA funding across the states.

2.27 In late-2012, the Taskforce liaised with EMA in relation to a number of areas identified during its project reviews where there was uncertainty about the eligibility of assets claimed for NDRRA funding. A Finance review of insurance arrangements also raised concerns about states’ interpretation and application of the definition of eligible assets.31 Subsequently, the guidelines released with the 2012 NDRRA determination included a clearer definition of an ‘essential public asset’. This provided greater clarity to the states in relation to essential public assets damaged on or after the date of the determination. For example, Guideline 6 lists 15 examples of assets that the Commonwealth would generally consider to be eligible. It also provides the examples of assets that the Commonwealth would not generally consider to be essential public assets.

2.28 However, effective action has not yet been taken in relation to the related issue of the Inspectorate’s project assessments identifying:

… systemic eligibility issues in road construction projects under the NDRRA where delivery agents have used ‘current engineering standards’ as justification to support the upgrading of their asset. The NDRRA provides funds for infrastructure to be reconstructed on a ‘like for like’ basis, using current construction methodologies and building materials. Upgraded constructions, such as road widening and additional drainage structures, do not fall within the definition of ‘current engineering standards’ and need to be funded separately.32

2.29 In this context, in February 2015, the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance commented to the ANAO that:

Victoria understands that while the concept of betterment was introduced in the 2007 NDRRA Determination, it was not well understood by either the states, local councils or the Commonwealth and that, to date, only one swimming pool in NSW has received funding from the Commonwealth for betterment.

2.30 Nevertheless, ANAO analysis of the sampled claims identified that it has been relatively common for NDRRA payments made by EMA to include amounts that relate to upgraded constructions. Similarly, in February 2014, the National Commission of Audit had also raised concerns about the extent to which state and local governments can in effect upgrade their assets using Commonwealth NDRRA funds. However, notwithstanding that the Taskforce provided a draft guideline to EMA in 2012, guidance has not yet been formalised and promulgated by EMA.

2.31 In the lead up to the re-issue of the determination in December 2012, the Taskforce had also requested that EMA define ‘engineering standards’ in the determination, but this did not occur. In addition, although what constitutes the appropriate standards was to be agreed between Queensland and EMA within two weeks of the execution of the National Partnership Agreement signed on 8 February 2013, this did not occur.33

2.32 In October 2014, EMA advised the ANAO that its recently revised and reissued Guideline 6 on ‘Essential Public Asset Restoration or Replacement’ includes guidance on ‘current building and engineering standards’. However, this provides little more than a rationale for allowing current standards to be used.34 It does not adequately address the concerns previously raised.35 In this context, demonstrating that the practices observed by the Inspectorate in respect to Queensland reconstruction projects are symptomatic, the projects examined by the ANAO included instances where it was evident that NDRRA funding claimed as being for the restoration or replacement of essential public assets had been applied to upgraded assets.

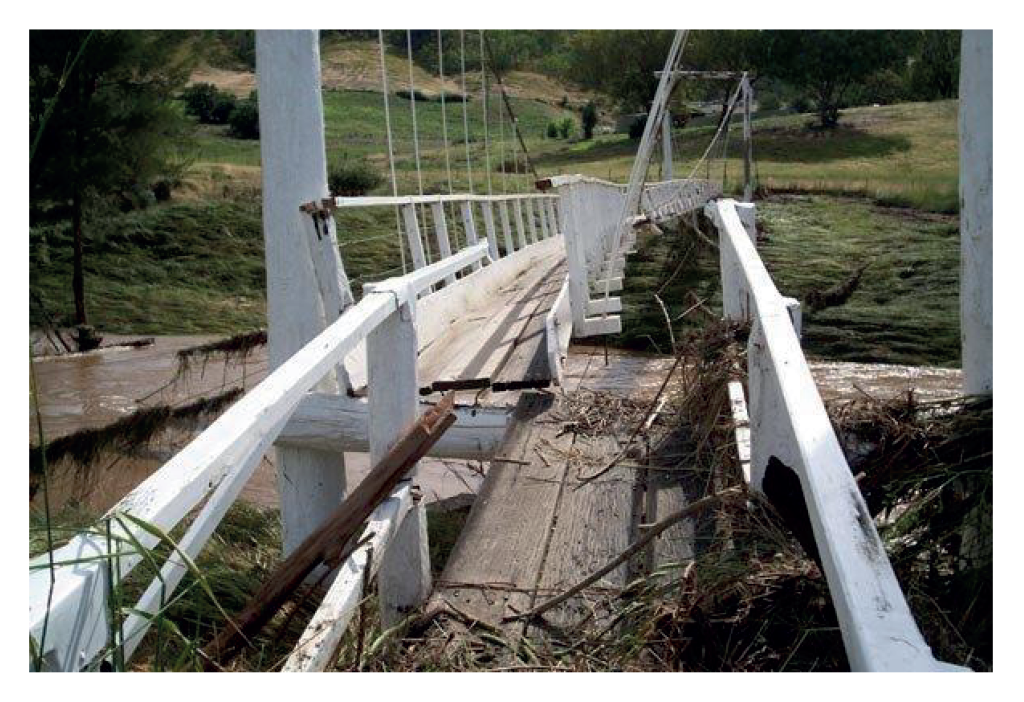

2.33 For example, the suspension footbridge over the Tuena Creek in Tuena was damaged during the NSW floods event that occurred in late-November 2010 and affected 53 LGAs and the state’s ‘unincorporated area’ [AGRN 421]. The original bridge was constructed in 1894. As it had also been damaged by floodwaters and repaired many times over previous years, rather than repairing the bridge, the Upper Lachlan Shire Council decided to replace it with a similar design, but to be built at a higher level to provide more protection from future floods. The new footbridge is now 1.5 metres higher and 15 metres longer (7.5 metres longer at each end) than the previously existing structure, at a (NDRRA) claimed cost of $421 484 (see Figure 2.2, Figure 2.3 and Figure 2.4). Although there were significant enhancements to this asset (including an increase in overall length and disaster resilience), no council contribution was made for the costs of the upgrades that extended beyond the like-for-like repair of the bridge (and no betterment application was submitted to the Commonwealth).

Figure 2.2: Tuena Creek footbridge, Tuena, NSW (before flood damage)

Source: www.pbase.com/image/71060830.

2.34 Evidencing the shortcomings of EMA’s current approach of placing significant trust in state agency certifications, both NSW Treasury and NSW Public Works suggested to the ANAO that there was no betterment included in the restoration of the bridge as it was constructed in accordance with current engineering standards. However, in February 2015 Upper Lachlan Shire Council advised the ANAO that:

The Tuena footbridge was replaced at a higher level to protect it from future flooding (it had been damaged numerous times in the past – suspension bridges are easily damaged by floods). Council staff collected a significant amount of anecdotal evidence to establish what level was required to protect the new bridge from damage caused by future routine flood events. The additional length was needed to connect the higher bridge to the bank on each end.36

Figure 2.3: Tuena Creek footbridge, flood damage

Source: http://imageshack.com/a/img259/8025/tuenab.jpg.

Figure 2.4: Tuena Creek footbridge, after rebuilding

Source: NSW Public Works.

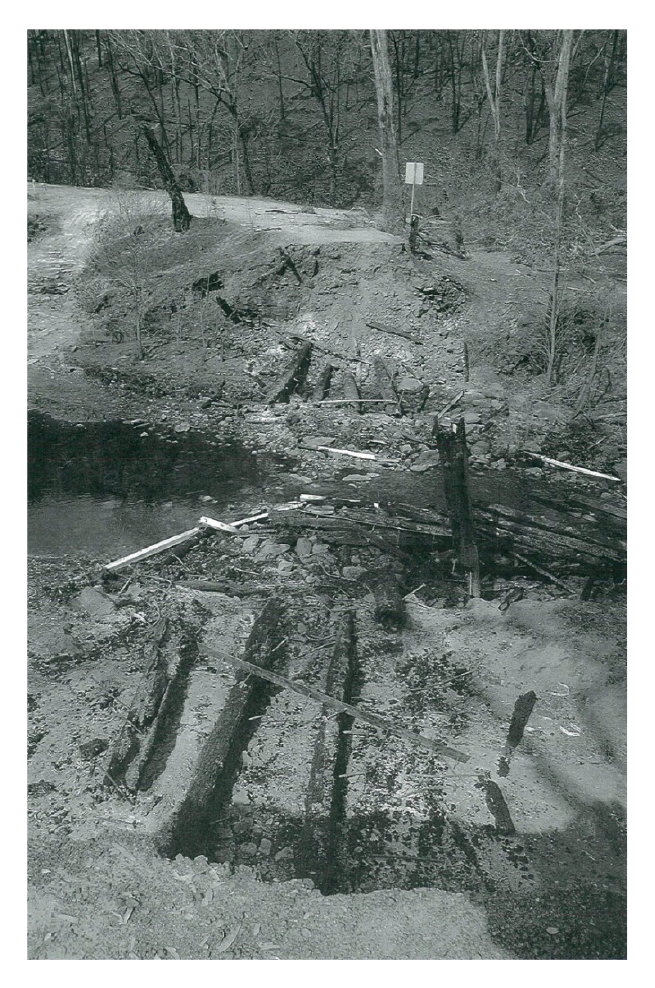

2.35 A similar example involved the Barkly River Bridge on the Glencairn Road in the Licola area in Victoria. It was built as a two span timber bridge 23 metres long and three metres wide with a 16 tonne load limit. As it was constructed in 1931, it was at or approaching the end of its economic life.37 After it was destroyed during the December 2006 Great Divide bushfires [AGRN 255] (see Figure 2.5), it was replaced with a higher three span concrete bridge 30 metres long and 4.5 metres wide with a 44 tonne load limit at a (NDRRA) claimed cost of $503 609. The stated reason for the bridge upgrade was to enable logging trucks to harvest timber in the area.38 Wellington Shire Council’s contribution to the project was only $15 000. No details were available in the contemporaneous documentation regarding how this figure was determined. In this respect, in February 2015 Wellington Shire Council advised the ANAO that:

The replacement structure was built in line with minimum Australian and Austroads Standards for bridge design including load capacity (T44) and width (4.5m) for a single lane bridge. There was no major alteration to the vertical alignment, with the abutments of the new structure constructed in the same vertical positions as the previous bridge.

… The $36 000 referred to within contract documentation is in relation to the bridge abutment construction, an integral part of the bridge structure, as opposed to the road approach. Approach earthworks were undertaken, as a method of both providing small improvements to approach geometry in line with design guidelines for new and replacement bridge structures and as a means of gaining access to natural materials suitable for associated civil works at the bridge abutments that were otherwise unavailable for a great distance. Given the nature of these works, it was agreed in discussions between VicRoads representatives and Council staff that an amount of $15 000 was attributable to any improvement outcomes that arose from these activities and this amount was subsequently paid by Wellington Shire Council.

Figure 2.5: Barkly River Bridge destroyed by fire, Licola, Victoria

Source: Wellington Shire Council.

2.36 A further example related to the March 2011 monsoonal flood and trough event which affected the Derby, Wyndham and Halls Creek areas in the Kimberley Region [AGRN 440] of Western Australia. The state’s claim included $2 441 927 for restoration works for the Great Northern Highway Fitzroy River Crossing. However, the supporting documentation provided by Main Roads Western Australia (MRWA) revealed that the Fitzroy River Bridge remained undamaged during this flood event. As shown in Figure 2.6, the amount claimed was actually to install extensive rock protection to the river bank to minimise future erosion and scouring (upstream near the south eastern end of the bridge, extending towards the Fitzroy Lodge). This is mitigation and enhancement work rather than the restoration of an asset to its pre-disaster standard and as such is not eligible for NDRRA reimbursement.39

Figure 2.6: Rock wall protection to river bank being installed at Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia

Source: Main Roads Western Australia.

2.37 Claims for the November 2010 NSW Floods examined by the ANAO similarly included installing rock protection, culverts and causeways at various sites where these did not previously exist; improving drainage; and raising the height of roads and causeways. In some instances it was apparent that roads were unformed, unmaintained or were being extensively sheeted with gravel in situations where this material did not constitute the pre-disaster road surface.

2.38 Reinforcing that these issues and NDRRA claiming practices are not isolated, in April 2013 the Queensland Audit Office reported that there was not enough reliable evidence provided that assets in that state were restored to their pre-disaster condition, or that only the proportionate costs relating to pre-disaster standards had been claimed. It recommended that councils affected by natural disasters implement the systems, processes and controls to demonstrate their funding claims relate only to eligible costs.

Interaction of state guidelines with NDRRA

2.39 State guidelines examined by the ANAO generally do not have a clear line of sight with the determination, particularly in relation to distinguishing between Category A, B, C and D eligible measures. In practice, this perpetuates common misconceptions among delivery agencies that all assistance measures are eligible in all situations, whereas the determination provides for targeted assistance in relation to various defined, and in some cases very specific, situations. Some of the perceived complexity attaching to the NDRRA funding rules is in part a result of differences between what is eligible for full funding under state disaster assistance schemes and the more restricted eligibility for partial reimbursement under NDRRA.

2.40 Under the Arrangements as currently designed, EMA does not have sufficient transparency of event-level expenditures to enable it to assess eligibility of the expenditures included in claims it approves for payment. In effect, state delivery agencies largely self-assess what they will claim for NDRRA advances and/or reimbursement. Accordingly, EMA places a very heavy reliance on the states ‘getting it right’40, yet has not provided sufficient, clear and consistent information that would enable such an expectation to be met. EMA has also given insufficient attention to how effectively information about NDRRA is disseminated to and within the various state departments and delivery agencies.

2.41 For example, EMA has not actively reviewed state guidelines to assess their consistency with the determination. In July 2009, states that had created their own ‘user guide’ were requested to provide these to EMA for information. Similarly, in September 2009, states that had ‘already established state-level disaster relief arrangements documentation’ were requested (through the NSG) to provide copies to other NSG members (including EMA). Only Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania provided such documentation. Further, EMA did not assess the adequacy of any of the state guidelines that were provided.

2.42 Depending on state administrative arrangements, it is also not uncommon for there to be more than just a single set of guidance (such as the central coordinating department’s guidelines) in relation to natural disaster assistance. For example, in NSW, as well as the Disaster Assistance Guidelines (NSWDAG) issued by Emergency Management NSW (now Ministry for Police and Emergency Services), a Treasury Circular providing guidelines for reimbursing agency expenditures related to disaster emergency and recovery operations; Roads and Maritime Services guidelines; and Public Works guidelines have been issued. In this and other jurisdictions, there were significant inconsistencies between these state guidelines and the determination (discussed below). Even where state guidelines have been provided to EMA, it has not detected and corrected inaccuracies, inconsistencies, omissions and other instances where further elaboration or clarification of requirements (such as eligibility conditions) would be beneficial.41

2.43 In the NSWDAG, local councils are advised that an initial agreed estimate is required before works start on the repair and restoration of their assets, which ‘can include council day labour costs and equipment and/or contractor costs to undertake the work’. Similarly, the NSW Public Works guidelines advised that:

… financial assistance is available to cover actual restoration costs, regardless of whether it is performed by council staff and equipment … and regardless of whether it is performed in standard hours or by using overtime or extra shifts.

2.44 This advice is contrary to the conditions set out in the determination. It is therefore not surprising that charges for day labour and for the use of plant and equipment owned by delivery agencies was included in NSW claims for NDRRA reimbursement examined by the ANAO, as is discussed further at paragraphs 2.45 to 2.62.

Day labour

2.45 One of the underlying principles of NDRRA is that lower levels of government should exhaust all resources prior to accessing assistance from higher levels. The requirement for each level of government to contribute appropriately to reconstruction is aimed at ensuring that lower levels of government do not shift the costs of their reconstruction responsibilities to the Commonwealth. In accordance with this principle, clause 5.2.5 of the determination provides that allowable ’state expenditure’ excludes:

d) amounts attributable to salaries or wages or other ongoing administrative expenditure for which the state would have been liable even though the eligible measure had not been carried out.

2.46 In this respect, in April 2010 EMA received legal advice that:

… a claim by a State Government in respect of ordinary wages of people in the ongoing employment of State or local governments is not consistent with the meaning of paragraph 5.2.5 (d) and the underlying philosophy of the Determination even though those employees may have been diverted from normal duties to natural disaster relief and recovery duties. The costs associated with overtime or backfilling to enable the ordinary duties of those employees to be completed could however be claimed.

2.47 Examination of the supporting documentation provided to the ANAO by delivery agencies for the sampled disasters revealed that it has been common for claims to include the ordinary wages of ongoing employees and related costs and charges, as well as indications of employees being claimed as contractors. For example:

- Western Australia’s 2011–12 claims for the December 2010 monsoonal low and associated flooding event [AGRN 418] included an amount of $312 962 described as work done by external contractors for reinstatement of the Carnarvon-Mullewa Road in the Shire of Upper Gascoyne. The supporting documentation recorded that the ‘contractor’ was MRWA and that the claim included $13 348 for MRWA employees’ normal time wages and salaries (ineligible day labour) as well as oncosts of $5473 (described as a ‘Payroll Surcharge’ and imposed at a rate of 41 per cent). The bulk of the claim ($241 865 or 77 per cent of the total amount claimed) consisted of MRWA plant hire charges42; and

- in 2006–07, the Rural City of Wangaratta (Wangaratta) claimed $226 452 for the King Valley and Tatong bushfires (included in Victoria’s NDRRA claim as the Great Divide Bushfire Complex which commenced on 1 December 2006 [AGRN 255]). Over 30 per cent of the claimed amount was for ordinary hours wages and oncosts (totalling $68 303). VicRoads correctly removed this ineligible amount when it reimbursed Wangaratta. However, the full amount was included in the state’s NDRRA claim (because the claim was based on initial estimates, rather than the amounts actually paid to local governments by VicRoads). Wangaratta also included ineligible owned-plant charges of $59 560 and a 10 per cent oncost on all materials supplied (these charges were not removed by VicRoads from the claim). On this basis, the ANAO analysis was that some two-thirds of the total amount claimed was ineligible for NDRRA reimbursement.

2.48 In February 2015, DTF acknowledged that it incorrectly claimed at the time the Rural City of Wangaratta’s normal day labour salaries and wages amounts through the NDRRA acquittal. It also commented that ‘this was not queried by EMA with reimbursement of the overall NDRRA acquittal provided to DTF’. It further advised that:

VicRoads notes that while EMA has recently developed guidance around the eligibility of Plant and Equipment, eligible costs associated with plant and equipment remains unclear, … especially around internal rate charges that Councils may wish to claim. This continued lack of clarity makes it difficult for the State and VicRoads to assess expenditure accurately on this basis.

2.49 Of particular note from the ANAO’s analysis was that day labour costs may have been included in all NSW claims for restoration or replacement of essential public assets. This is as a result of state guidelines which have instructed delivery agencies to include these costs in their claims (see paragraph 2.43). In accordance with this advice, the ANAO observed that in relation to the November 2010 NSW flood event [AGRN 421]:

- the Dubbo City Council claimed a total of $1 282 264 through NSW Public Works for emergency works and restoration works associated with this flooding event undertaken at the Macquarie Regional Library; Dubbo Visitors Information Centre; and various parks and landcare facilities. Of this amount, general ledger transaction listings were included in the supporting documentation provided to the ANAO for $316 640 (25 per cent of the total claimed). This included payroll costs for council employees43 plus oncosts charged variously at 59 per cent and 27 per cent; hire of council-owned plant plus plant oncosts charged at 50 per cent; materials oncosts charged at 18 per cent; and stores oncosts charged at 17 per cent; and

- although only ‘lump sum’ costs per road were provided to the ANAO that did not disaggregate restoration costs by provider (such as the use of council’s own labour force and equipment versus the use of equipment and labour supplied by external contractors), in March 2012 the Upper Lachlan Shire Council acknowledged to the NSW Minister for Finance and Services that in relation to this flood event ‘Council has mainly used day labour … to repair its roads … and costs in relation to wages for those activities have been paid’ by the then Roads and Traffic Authority, now Roads and Maritime Services (RMS). Council received a total of $5 739 939 from RMS for road restoration. In addition it received $588 186 from NSW Public Works for the restoration of two pedestrian foot bridges, which also included an unquantified component of day labour costs.

2.50 Further evidencing that the current administrative arrangements, which EMA advised the ANAO it views as adequate44, are insufficiently effective, the NSW Department of Public Works advised the ANAO in February 2015 that:

In developing operational guidance for applying the 2007 Determination, NSW Public Works and the NSW Treasury, determined with respect to the eligibility of normal wages and salaries, the following guidance:

- Operational wages and salaries of an overhead/supervisor type were not eligible as they were considered to be council core business.

- Wages and salaries associated with the initial clean-up component of disaster recovery were not eligible as it was considered to be council core business.

- Direct wages associated with asset restoration/rebuilding were eligible as they were not considered council core business and where employees were redeployed from other council work.

This issue was not clarified further by the Commonwealth until March 2014 when guidelines regarding wages and salaries (Clause 5.2.5) were issued. Following receipt of this guidance, NSW Public Works immediately issued changes to the eligibility criteria guidance regarding wages and salaries to align with the clarification to the December 2012 Determination.45 The new guidance applies to all disasters declared after 23 October 2013, the date that the NSW Government formally aligned its natural disaster eligibility criteria guidance to the December 2012 Determination.46 There has subsequently been a significant maturity with respect to the detail in guidelines supporting the release of the new Determination to assist with administration and consistency. With the release of the 2012 Determination there are now ten guidelines issued.47 Emergency Management Australia is to be commended for this initiative.

2.51 Similarly demonstrating the ineffectiveness of the existing arrangements, in February 2015:

- Dubbo City Council acknowledged to the ANAO that its claims for natural disaster assistance included the costs of using council’s staff and plant; and

- Upper Lachlan Shire Council in NSW advised the ANAO that:

Council used day labour (supplemented by a number of contractors) to repair its damaged roads. Council staff had carried out natural disaster repairs in this manner before and was unaware that this action was unacceptable to NDRRA.

2.52 Also in February 2015, the NSW Roads and Maritime Services (RMS) also advised the ANAO that:

RMS’ natural disaster program guidelines (current and those in operation in 2010) align with the NDRRA and do not allow day labour costs to be claimed by councils. These guidelines are publicly available on the RMS website for councils.

… RMS concedes that council may seek to incorporate labour costs in the unit rates used to assess damage. RMS notes however, that the current assessment process does not provide the level of visibility required to identify and exclude ineligible cost components. This matter will be considered as part of the review of NSW natural disaster arrangements currently being implemented by the Ministry for Police and Emergency Services.

2.53 Notwithstanding there is evidence that day labour continues to be incorrectly included in NDRRA claims, in January 2015, AGD advised the ANAO that the department has provided advice to states on day labour and also received assurances from states on ‘numerous occasions’ that they are not claiming day labour costs. AGD further advised that the Prime Minister in 2010 also sought and AGD received assurances from all states that day labour costs had not been included in any NDRRA claim (with the exception of Queensland, since EMA in 2010 identified the inclusion of day labour in its 2008–09 claim).

2.54 However, EMA records show that the assurances provided in 2010 by two of the states were not unequivocal, having been qualified as follows:

- NSW acknowledged that ‘it may have included some ineligible costs in its claims submitted to the Commonwealth previously’ (at the time NSW had not submitted its claims for the five years ended 30 June 2013 – see further at paragraph 2.63)48; and

- Western Australia acknowledged that it was claiming for ‘plant overtime’. That is, the claiming of external hire rates for the use of plant and equipment owned by state delivery agencies when operated outside weekday hours of 9.00am to 5.00pm.49

2.55 Further, with the exception of the assurances specifically requested by the Prime Minister in 2010, EMA was unable to provide the ANAO with evidence that it had received any assurances on any occasions that states have not been claiming day labour costs.

Disaster notification and registration

2.56 Successive determinations have required that when a natural disaster occurs and the relevant state knows, or expects, the disaster to be an eligible disaster, the state must notify the Secretary of AGD of that fact as soon as practicable. The notification must be in the form set out in Attachment A to the determination. ANAO analysis of the three sampled states was that while in practice EMA may become aware of state disaster declarations soon after they are issued (such as through monitoring of state media releases) it is not uncommon for there to be delays in EMA being notified. For example:

- for 36 Western Australian events where relevant data was available: the average elapsed time taken to provide the notification was almost 34 days; the median was 13 days; and the notifications ranged from the same day to 246 days;

- for 158 NSW events where relevant data was available: the average was 98 days; the median was 80 days; and the notifications ranged from two days to 538 days (the latter was a storm event on 19 January 2011 which was notified to EMA on 10 July 201250); and

- for 24 Victorian events where relevant data was available: the average was 24 days; the median was seven days; and the notifications ranged from three days to 380 days.

2.57 It was also quite common for EMA to be slow (taking up to six months) to acknowledge disaster notifications. Further, the types of details recorded in EMA’s NDRRA disaster event notifications register have varied over the years and within years. Recording has been inconsistent, and in parts the information is inaccurate or incomplete.

2.58 The current administrative arrangements also do not adequately manage the risk of claims for NDRRA assistance including costs that relate to undeclared events or for LGAs that were not declared as affected by a particular disaster. For example, in respect to the Kimberley Monsoonal Flood and Trough that occurred in March 2011 [AGRN 440], the WA Department of Parks and Wildlife claimed for amounts that involved works at locations not within the declared LGAs (the shires of Derby-West Kimberley, Halls Creek and Wyndham-East Kimberley), as follows:

- six invoices for $5874 were claimed for various works undertaken in Broome (within the Shire of Broome); and

- $30 500 was claimed for travel on a commercial charter vessel to undertake works at Rowley Shoals (situated in the Indian Ocean approximately 300 kilometres west of Broome).51

2.59 In February 2015, the Department of Parks and Wildlife advised the ANAO that the six invoices for works undertaken in Broome had been ‘erroneously coded’ to this event notwithstanding that these claims had been cross-checked and authorised for reimbursement to the department by the state authority responsible for administration of NDRRA. In respect to the claim relating to the Rowley Shoals Marine Park, the department acknowledged to the ANAO that this park falls within the Shire of Broome which was not a declared LGA for the event. It further advised the ANAO that there was an ‘unintentional oversight’ by the department in claiming for an expense that did not fall within the declared NDRRA boundaries and that this was ‘compounded by the extensive remediation works that were being undertaken concurrently in adjacent declared areas’. The department also suggested that consideration be given to vessel mooring infrastructure being considered an essential public asset so that they might, in future, be eligible for NDRRA funding.