Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Medical Specialist Training Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s administration of the Medical Specialist Training Program.

Summary

Introduction

1. State and territory governments currently fund over 90 per cent of all medical specialist training in Australia through specialist trainee1 positions in public teaching hospitals. Over the past 15 years the Australian Government has also contributed to medical specialist training through a range of Commonwealth-funded programs administered by the Department of Health (Health).2

2. Australian Government programs were consolidated in 2009 as the medical Specialist Training Program (STP), in order to create a simpler and more flexible funding program. In March 2010 the then Government announced additional funding of $144.5 million over four years to increase the number of specialist training positions under the STP from around 360 to 900 by 2014.3 The funding increase—part of a wider National Health and Hospitals Network initiative—was intended to assist in addressing a forecast shortage of specialists in Australia by drawing on the private sector and other non-traditional avenues for training.4

Specialist Training Program

3. The Government intended that medical specialties with shortages were to be targeted through the expanded STP, including general surgery, pathology, radiology, dermatology, obstetrics and gynaecology. Priority was also given to providing training positions ‘where Australians need them, such as in rural and regional areas’.5

4. The objectives of the STP are to6:

- increase the capacity of the health care sector to provide high quality, appropriate training opportunities to facilitate the required educational experiences for specialists in training;

- supplement the available specialist workforce in outer metropolitan, rural and remote locations; and

- develop specialist training arrangements beyond traditional inner metropolitan teaching hospitals.

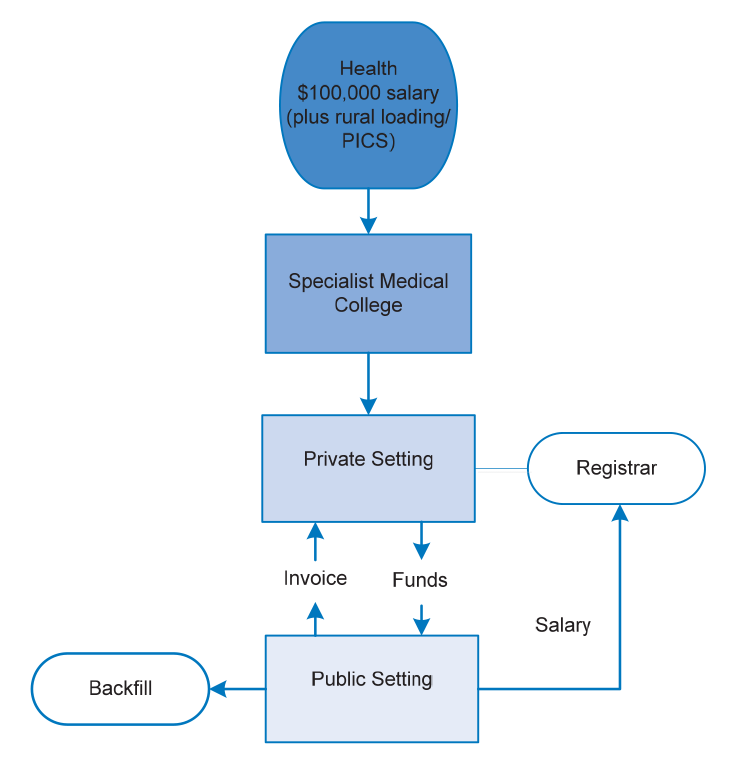

5. The STP is an executive grants program7 involving annual competitive funding rounds. The Australian Government provides financial assistance to hospitals and other medical facilities or health organisations (known as ‘settings’) to employ specialist trainees. Depending on the circumstances, STP grants to settings can consist of a number of components, as follows:

- the primary component is in the form of salary support to settings to assist with the cost of employing a specialist trainee in a specified training position. Salary support is set at $100 0008 per full-time equivalent (FTE) per year;

- training positions outside metropolitan areas are eligible for an additional rural loading of $20 000 per FTE per year; and

- training positions in a private sector setting are eligible for the Private Infrastructure and Clinical Supervision allowance, consisting of a supervision allowance of $30 000 per FTE per year9 and a training infrastructure allowance of $10 000 per FTE once every three years.

6. As a consequence, an STP grant will typically provide financial assistance of between $100 000 to $153 333 per FTE per year for a training position.

7. Under the STP, specialist trainees are placed in specified training positions within public or private hospitals, other medical facilities or health organisations that are accredited for the purpose of specialist training by the relevant specialist medical college (college). Specialist trainees will generally rotate through a number of training positions at different hospitals or facilities during their specialist training in order to gain a broad range of experience and skills. Completion of specialist training normally takes between three and six years depending on the speciality involved. Subject to meeting any other college requirements, specialist trainees are then eligible to apply for Fellowship10 of the relevant college and be recognised as a fully qualified specialist.

8. While Health has overall responsibility for STP administration, the department does not have a direct contractual relationship with the settings, which are the grant recipients. The administration of STP grant funds is managed through separate agreements between Health and the colleges.11 Under this ‘college administration’ model, all grant funding for STP training positions for a particular specialty is provided by Health to the relevant college.

9. Overall, STP expenditure from 1 July 2010 to 31 December 2014 has been $379 million. While the STP is an ongoing initiative, current funding agreements with colleges expire at the end of 2015. As at January 2015, the Government has not made a decision on future STP funding.

Previous audit coverage

10. The ANAO has not previously examined the STP. ANAO Performance Audit Report No.34 2010–11 General Practice Education and Training examined the management of general practice vocational education and training programs by General Practice Education and Training Limited (GPET), then a Commonwealth company.

Audit objective and criteria

11. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s (Health) administration of the STP. The audit focused on key aspects of Health’s administration of the STP since the consolidation of funding programs in 2009, and the achievement of key program targets and objectives. To assess the department’s grants administration, the ANAO focused on the fourth annual grant funding round (the 2014 round) which was completed in December 2013 and funded training positions from the beginning of 2014.

Overall conclusion

12. Australian Government programs providing support for medical specialist training were consolidated in 2009 as the Specialist Training Program (STP), and in March 2010 the then Government announced additional funding of $144.5 million over four years to increase the number of specialist training positions funded under the STP from around 360 to 900 by 2014. The funding increase was intended to help address a forecast shortage of specialists in Australia by tapping into the private sector and other non-traditional training settings. The STP is a grants program, with four annual competitive funding rounds conducted since its expansion in 2010. While the Department of Health (Health) has overall responsibility for STP administration, the department receives advice from state health services12 and specialist medical colleges as part of the grants assessment process, and disburses grants through the colleges.

13. Health has made substantial progress towards achieving the key STP targets and objectives, adopting a generally sound administrative approach which has improved over time. The STP training targets established in March 2010 have largely been met, with college reports indicating that some 93 per cent of training positions have been filled13, and some 89 per cent of funded training positions have been located in non-traditional settings. However, in the 2014 grant funding round Health adopted an internal review and rescoring procedure which was not documented, and the department did not strictly adhere to the published selection criteria; an approach which affected the transparency and to an extent the equity of the assessment process when viewed in terms of the application form and other explanatory material that informed applicants’ expectations about how grants would be selected.

14. The ANAO’s analysis of specialist medical college reports provided to Health indicates that, on a full-time equivalent (FTE) basis, around 833 training positions were filled as at 30 June 2014, representing some 93 per cent of the target of 900 training positions announced in March 2010. Further, college reporting indicates that the STP has been successful in utilising non-traditional settings to expand the number of specialist training opportunities. The most recent (July 2014) reporting indicates that 800 (89 per cent) of the training positions are in ‘expanded’ (non-traditional) settings, with 369 (41 per cent) in regional or rural areas.

15. The 2014 funding round, which was completed in December 2013 with a view to funding training positions from early 2014, increased the number of funded training positions from 750 to 900. The first stage of the assessment process for the 2014 round was soundly-based and benefited from third-party assessment of applications by state health services and colleges. However, Health decided not to fund some highly-rated applications recommended by the state health services and colleges as it sought to obtain a relatively even distribution of the new training positions against the population. In adopting this approach, which also featured in the previous (2013) funding round14, the department effectively applied a selection criterion that was not documented in the application form or other explanatory material made available to applicants. Although the program’s funding priorities, which underpinned the assessment criteria, were reviewed between rounds, Health did not take the opportunity to incorporate a reference to the approach adopted on population distribution in the 2014 round application form or explanatory material. Nevertheless, when considered in the context of the program’s intended outcomes (which include achieving a better geographical distribution of specialist services) the department’s approach in relation to this matter was not unreasonable.15

16. Further, the department advised the ANAO that it also adopted an internal review and rescoring procedure in the 2014 round16, to address differences in assessment scores from the state health services and colleges17; another departure from documented processes. Health’s approach was also inconsistent with information provided to applicants that the department would ‘collate’ assessment results received from state health services and the colleges, and advice to the Health Minister in March 2013 that the department’s selection of applicants was ‘essentially administrative’ as individual assessments were based on recommendations received from the state health services and colleges.

17. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the transparency and equity of Health’s grants administration by: reviewing program guidelines and assessment criteria to incorporate lessons learned from funding rounds; and providing operational guidance to staff on moderation or other quality control processes to be applied to assessments by third-party advisers.

Key findings by chapter

Assessment and Selection of Applications (Chapter 2)

18. In the 2014 funding round, applications for STP grants were open to a broad range of organisations, consistent with the general program objective that specialist training occur beyond traditional teaching settings. The assessment process for the selection of grants was also outlined in explanatory material to the application form. Stakeholders informed the ANAO that the opening of the 2014 round was well publicised amongst potential applicants, and in the event, some 467 applications were received for the 150 available grants.

19. Health trialled the use of shared services for the 2014 funding round, to make the application process easier for applicants and to achieve administrative efficiencies. However, stakeholders advised the ANAO that while the electronic application process had improved overall administration compared to previous rounds, the trial suffered from insufficient testing prior to implementation. In particular, the trial encountered significant technical problems relating to the receipt and processing of applications, and the anticipated benefits and efficiencies were not fully realised.

20. The assessment criteria and selection processes outlined in the department’s assessment plan, application form and other publicly available explanatory material for the 2014 round reflected Australian Government priorities, which were informed by published research of Health Workforce Australia. Further, the involvement of specialist medical colleges and state health services in the assessment of applications strengthened the assessment process. In particular, the state health services and colleges provided third-party advice to Health on the educational merit of applications, the potential impact of applications on health services, and the extent to which applications met program funding priorities.

21. ANAO testing of Health’s final assessment of applications for the 2014 funding round indicated that the department adopted an internal review and rescoring process after receiving input from state health services and the colleges. Around 250 of the 467 applications received in the 2014 STP funding round were reviewed as part of this process, which was not documented. ANAO analysis indicates that the rescoring directly affected funding outcomes for 13 applications, representing some 2.8 per cent of all (467) 2014 round applications. For 12 of these applications, the final score assigned by Health was above that which was calculated by the ANAO based on input from the specialist medical colleges and state health services, indicating these applications likely benefited from the review and rescoring process to the extent that they were offered grants. As there were only 150 grants available through the 2014 round, the elevation of the 12 applications meant that some applicants that may have otherwise been offered a grant were not. One application was scored down by the department and as a consequence of this, was not offered a grant.

22. Further, the department decided not to fund some highly-rated applications received as part of the 2014 funding round. Specifically, 13 applications were placed on a ‘reserve’ list18, as the relevant setting had submitted applications for two or more training positions in the same specialty.19 In these cases, Health funded only one place in order to obtain ‘a relatively even distribution of the new training positions against the population data’. In adopting this approach, Health effectively applied a selection criterion that was not documented in the application form or other explanatory material made available to applicants for the 2014 funding round. Health’s approach was inconsistent with the instructions provided to applicants for completing the program application form, which indicated that the department would ‘collate’ assessment results received from state health services and the colleges. Further, the approach adopted was not consistent with advice provided to the Health Minister in March 2013 that the department’s selection of applicants to be funded under the STP was ‘essentially administrative’, and that individual assessments were based on recommendations received from the state health services and colleges.

23. The lack of appropriate record-keeping and quality control in the internal review and rescoring process, and the use of a selection criterion that was not contained in the 2014 round application form or other explanatory material available to applicants, affected the transparency and to an extent the equity of the assessment process when viewed in terms of the application form and other explanatory material that informed applicants’ expectations about how grants would be selected.20 However, as previously noted, the department’s approach in using a selection criterion that incorporated population distribution considerations was not unreasonable in the context of the program’s intended outcomes.

Administration of Funding Agreements (Chapter 3)

24. A feature of the STP is that while Health has overall responsibility for its administration, the department does not have a direct contractual relationship with individual settings, which are the grant recipients. Rather, the administration of STP grant funds is managed through separate agreements between Health and the respective colleges. Under this ‘college administration’ model, developed by the department in 2010, all grant funding for STP training positions within a particular specialty is provided by Health to the relevant college.

25. The colleges and settings interviewed by the ANAO indicated that the ‘college administration’ model generally worked well. However, some potential risks were not fully assessed by Health when developing the model, including the risk that the Australian Government’s financial framework requirements might apply to the colleges if they handled public money.21 It is prudent for government entities to consider, at the design stage, the full implications of complex financial and administrative arrangements—such as those involving third-party administration of government programs—so as to avoid potential compliance and reputational risks.22

26. The department relies on reports received from the colleges to inform its oversight of the college administration model.23 Since 2012 Health has sought additional management and performance information from the colleges, particularly relating to financial issues. However, the presentation of financial information by colleges—particularly income and expenditure—has varied significantly, sometimes making it difficult for Health to assess how funds have been spent. Where variations in reporting have occurred, Health has undertaken follow-up communication with colleges to determine their actual financial position.

27. As at 31 December 2013, total surpluses of STP funds held by the colleges were $36.28 million.24 By 30 June 2014, total surpluses had risen to $56.31 million. The surpluses can be partly attributed to timing issues, including delays in the submission of invoices by training settings to the colleges. During 2014, Health responded more actively where surpluses were identified, by withholding a proportion of scheduled progress payments. In consequence, $23.89 million that was due to be paid following receipt of the July 2014 college reports was withheld.

Program Performance and Evaluation (Chapter 4)

28. The STP has had key performance indicators (KPIs) in place since the consolidation of the program in 2009. However, explicit outcome-linked KPIs were only developed in 2013, and the colleges have reported against these KPIs since January 2014.

29. College reporting against the program’s KPIs indicates that the STP has been successful in utilising non-traditional settings to expand the number of training positions for specialist trainees, with 89 percent of STP-funded positions being located in non-traditional settings. In discussions with the ANAO, stakeholders also suggested that the expanded range of work environments has contributed to the overall quality of training.

30. ANAO analysis of college reporting indicates that on a FTE basis, around 833 training positions were filled as at 30 June 2014, representing 93 per cent of the target of 900 positions. Overall, the additional specialist trainee positions funded by the STP have boosted the availability of specialist services, including in regional and rural areas. However, it remains unclear to what extent the STP has, or will, contribute to an improved geographical distribution of specialist services to meet community need, over the longer term.

Summary of entity response

31. The Department of Health agrees with the audit recommendation. The findings of the audit will be of value in the future administration of the Medical Specialist Training Programme.

32. Health’s full response is provided at Appendix 1.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.45 |

To improve transparency and equity in the administration of grants, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

Department of Health response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides the background and context for the audit including an overview of the Medical Specialist Training Program. The audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology are also outlined.

Training medical specialists in Australia

1.1 In Australia, medical graduates must undergo a 12 month period of additional training before becoming fully qualified as medical practitioners (doctors) and receiving a provider number to enable billing under Medicare.25 Most commonly, this training involves an internship at a public hospital, followed by a further 12 months as a resident medical officer. After this, doctors may undertake further training, either in general practice or in a particular medical specialty.26 In the latter case, a doctor will enter a training program under the auspices of the relevant specialist medical college (college).27

1.2 Under these college programs, specialist trainees (also known as registrars) are placed at specified training positions28 within public or private hospitals, other medical facilities or health organisations that are accredited for the purpose of the specialist training programs by the relevant college.29 Specialist trainees will generally rotate through a number of training positions at different hospitals or facilities (which are called ‘settings’) during their specialist training in order to gain a broad range of experience and skills.

1.3 On completion of specialist training—which may take between three and six years30—and subject to meeting any other requirements of the relevant college, specialist trainees are eligible to apply for Fellowship31 of the college and be recognised as a fully qualified specialist. Whilst undergoing training, specialist trainees may choose to focus on a particular sub-speciality or discipline.32 Alternatively, they may train across a broader spectrum: in some cases this may lead to specialist trainees qualifying within a ‘generalist’ specialist stream.33 An illustrative medical education and training pathway for a specialist is shown at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Medical specialist education pathway in Australia

Source: Health Workforce 2025—Volume 3 Medical Specialties, p. 406.

1.4 There has been substantial growth in the overall number of fully qualified specialists in recent years. Excluding general practice specialists, the number of actively-practising college Fellows has risen from 26 946 in 2008 to 32 702 in 2012, an increase of 21.4 per cent.34,35 Excluding general practice, the number of specialist trainees undergoing specialist training increased from 10 649 in 2009 to 13 801 in 2013, an increase of 29.6 per cent.36 In comparison, Australia’s population increased by 7.7 per cent between 2008 and 2013.37

The Specialist Training Program

Background

1.5 State and territory governments currently fund over 90 per cent of all medical specialist training in Australia through specialist trainee positions in public teaching hospitals. Over the last 15 years the Australian Government has also contributed medical specialist training through a range of programs administered by the Department of Health (Health). These programs have funded a broad range of activities, including those with a specific geographic focus38, directed at a particular specialty39, or dealing with doctors trained outside Australia.40 In 2009, programs funded by the Australian Government were consolidated into the medical Specialist Training Program (STP) in order to create a ‘simpler, more flexible funding program’.41

1.6 In March 2010, the then Australian Government announced a range of significant health policy and funding measures under the National Health and Hospitals Network initiative. A component of the initiative was additional funding of $144.5 million over four years to increase the number of specialist training positions under the STP from around 360 to 900 by 2014.42

1.7 The 2010 Australian Government announcement noted that work by the Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee43 and the colleges suggested there would be a shortage of 1280 specialists in Australia by 2020. The expansion of the STP aimed to deliver 680 additional specialists by 2020 by drawing on the private sector and other non-traditional avenues for training. The remainder of the projected shortfall was to be addressed by state health services44 increasing the number of training positions in their public teaching hospitals. Specialties where shortages existed were to be targeted through the expanded STP, including general surgery, pathology, radiology, dermatology, obstetrics and gynaecology. Priority was also given to providing training positions ‘where Australians need them, such as in rural and regional areas’.45

1.8 The objectives of the STP are to46:

- increase the capacity of the health care sector to provide high quality, appropriate training opportunities to facilitate the required educational experiences for specialists in training;

- supplement the available specialist workforce in outer metropolitan, rural and remote locations; and

- develop specialist training arrangements beyond traditional inner metropolitan teaching hospitals.

1.9 The objectives outlined above were to be ‘achieved without an associated loss to the capacity of the public health care system to deliver services’.47’48

1.10 Associated with the STP objectives are nine ‘expected outcomes’49:

- rotation of specialist trainees through an integrated range of settings beyond traditional inner metropolitan teaching hospitals, including a range of public settings (including regional, rural and ambulatory settings), the private sector (hospitals and rooms), community settings and non-clinical environments;

- increased number and better distribution of specialist services;

- increased capacity within the sector to train specialists;

- improved quality of specialist training with trainees gaining appropriate skills not otherwise available through traditional settings;

- development of system wide education and infrastructure support projects to enhance training opportunities for eligible trainees;

- improved access to appropriate training for overseas trained specialists seeking Fellowship with a college;

- increased flexibility within the specialist workforce;

- development of specialist training initiatives that complement those currently provided by state health services; and

- establishment of processes which enable effective and efficient administration of specialist training positions, with reduced complexity for both stakeholders and the administering department.

1.11 The STP is administered by the Australian Government through the Department of Health (Health).50 Formal stakeholder input into the operation of the STP is through two main sources: the Medical Training Review Panel51 and the STP inter-college forum.52

How the program is delivered

1.12 The STP is an executive grants program53 involving annual competitive funding rounds.

Funding

1.13 The grants are provided to hospitals and other medical facilities or health organisations to employ specialist trainees. Depending on the circumstances, STP grants to settings can consist of a number of components, as follows:

- The primary element is in the form of salary support to settings to financially assist them to employ a specialist trainee at a specified training position. Salary support is set at $100 000 (ex GST)54 per full-time equivalent (FTE) per year.55

- Training positions outside metropolitan areas are eligible for an additional rural loading of $20 000 per FTE per year.56 ANAO discussions with settings indicate this ‘rural loading’ is used to subsidise a range of expenses, including covering transport costs or, in some cases, providing specialist trainees with accommodation and/or a vehicle.

- Where the position is in a private sector setting, it is also eligible for the Private Infrastructure and Clinical Supervision allowance. This consists of a clinical supervision allowance of $30 000 per FTE per position, per year—which is intended to recognise the time and effort involved in a specialist supervising a specialist trainee whilst they are undertaking training—and a training infrastructure allowance of $10 000 per FTE once every three years.57 Consistent with the intent of the STP to utilise non-traditional avenues for specialist training, the Private Infrastructure and Clinical Supervision provides an incentive for the private sector to participate in the program.

1.14 As a consequence, an STP grant will typically provide financial assistance of between $100 000 to $153 333 per FTE per year for a training position.

1.15 In order to avoid cost-shifting58, the STP only funds ‘new’ training positions. Training positions that have been funded from any source for more than 12 months out of the last three years are ineligible for STP grants.59,60 Applications must also be accompanied by a letter of support from the local hospital network as well as the relevant college.

Administration

1.16 A feature of the STP is that while Health has overall responsibility for its administration, the department does not have a direct contractual relationship with the settings, which are the grant recipients. Rather, the administration of STP grant funds is managed through separate agreements between Health and the colleges. Under this ‘college administration’ model, all grant funding for STP training positions within a particular specialty is provided by Health to the relevant college. Under their respective funding agreements with Health, the colleges have responsibility for:

- disbursing the STP grant funds to the relevant settings through periodic payments;

- oversight of the conduct of the funded training positions through contractual and liaison arrangements with the settings;

- the development and implementation of strategic training and education projects to support the network of STP training positions;

- promoting the integration of training provided through STP training positions with that provided by state health services; and

- providing progress and financial reporting to the department.

1.17 Colleges receive funding from Health to undertake the administrative functions referred to in paragraph 1.16.61 The amount of administrative funding provided by Health varies between specialist medical colleges when measured on a ‘per position’ basis. However, for the majority of specialist medical colleges the amount of administrative funding is approximately $5000 to $10 000 per position, per year.62

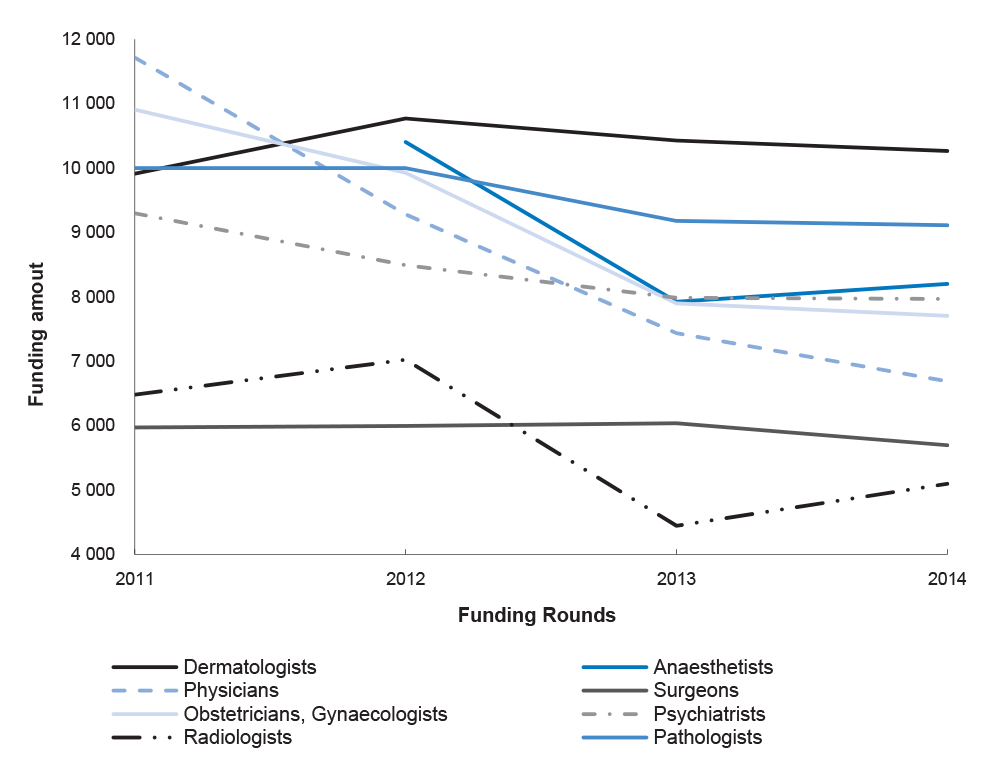

Progress in implementing the Specialist Training Program

1.18 Since the expansion of the STP announced in 201063, four annual STP competitive funding rounds have been conducted by Health.64 The 2014 round65, which was completed in December 2013, increased the number of training positions funded under the program from 750 to 900. The progressive expansion in the number of STP training positions through the four funding rounds is shown in Table 1.1. As at December 2014, the Australian Government has not announced whether any further funding rounds will be undertaken, or whether supported training positions will have funding extended beyond the current contractual commitments that cease at the end of December 2015.

Table 1.1: Expansion of STP training positions 2011–2014

|

Funding Round |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

New training positions funded |

158 |

82 |

150 |

150 |

|

Cumulative training positions funded |

518 |

600 |

750 |

900 |

Source: Department of Health Annual Reports.

1.19 While the STP has achieved the target of 900 training positions, some funded settings have subsequently withdrawn from the program or have had periodic difficulties in attracting or retaining specialist trainees in the training positions. In such cases, colleges have utilised so-called ‘reserve lists’ of highly ranked unsuccessful applicants from the previous funding round to boost the number of occupied training positions. While calculating the exact number of occupied training positions is difficult due to some variations in the relevant college reports and/or late reporting by settings, ANAO analysis indicates that around 833 of the 900 training positions66 (93 per cent) were occupied during the January to June 2014 reporting period. Several colleges with higher vacancy rates67, or which experienced underspends of previously provided STP funds68, indicated in their July 2014 progress reports that they will draw on reserve lists from the 2014 funding round to increase the number of occupied training positions in the second half of 2014 and in 2015.

1.20 ANAO analysis of Health’s financial records indicates that over the four years from 2010–11 to 2013–14, some $336.53 million has been expended on the STP, as shown in Table 1.2. In the first six months of 2014–15, expenditure has slowed over that of the previous year, with $42.46 million spent to 31 December 2014. This reflects the department’s decision to withhold a proportion of scheduled progress payments in response to the build–up of significant surpluses of STP funds held by the colleges.69

Table 1.2: STP expenditure 2010–11 to 2014–15

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 (to 31 December 2014) |

|

$58.06 million |

$71.34 million |

$96.25 million |

$110.88 million |

$42.46 million |

Source: Department of Health data.

Notes: The above figures do not include the amounts for two other initiatives, Emergency Department Workforce (Doctors and Nurses) and Specialist Training in the Tasmanian public health system, which are largely delivered under STP agreements with the colleges. These two initiatives provide funds, including to support specialist training positions, of up to $123.83 million from 2010–11 to 2015–16. Further details are at paragraphs 1.23–1.28.

Distribution of Specialist Training Program training positions

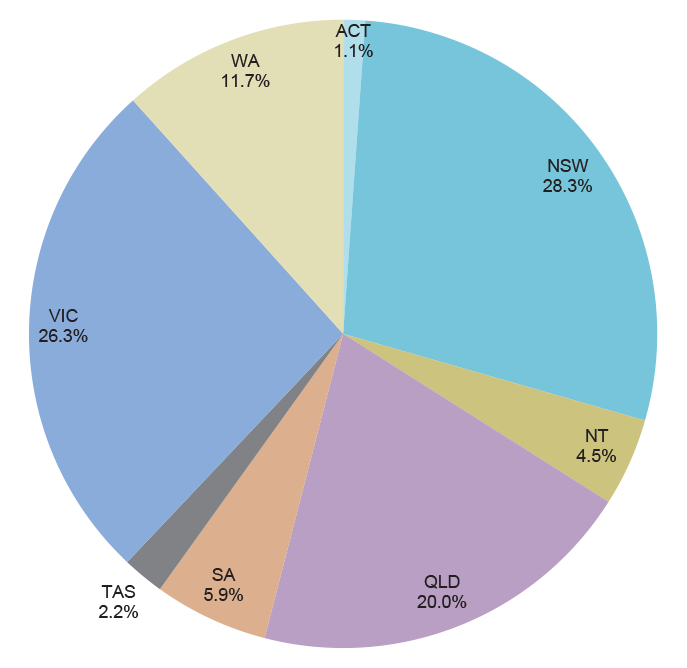

1.21 The national distribution of all funded STP training positions is shown in Figure 1.2. The distribution broadly corresponds to population distribution, with the exception of the Northern Territory, which has 4.5 per cent of STP training positions but only one per cent of Australia’s population.70

Figure 1.2: Funded STP training positions 2010–14 by State and Territory

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Health data.

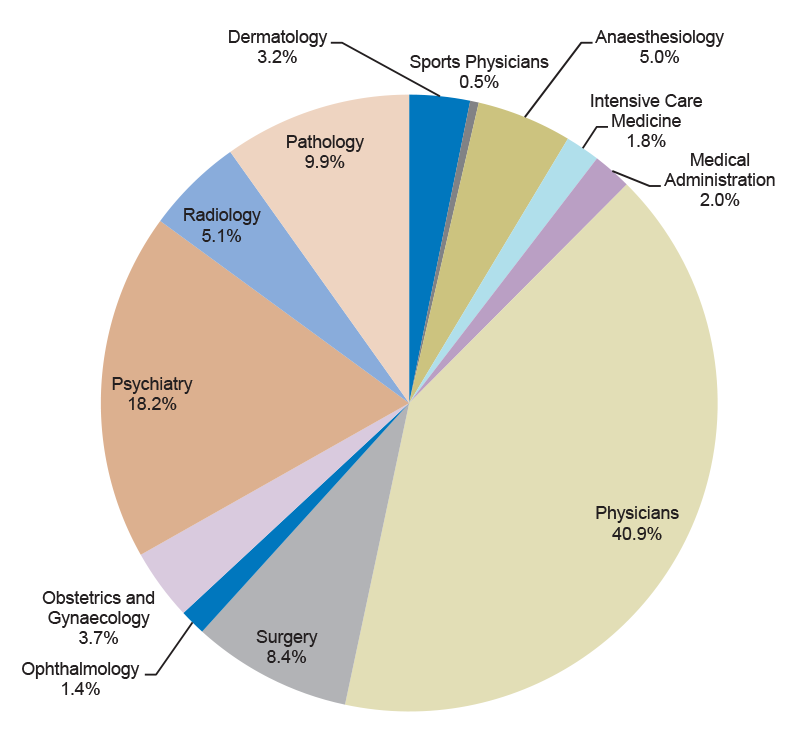

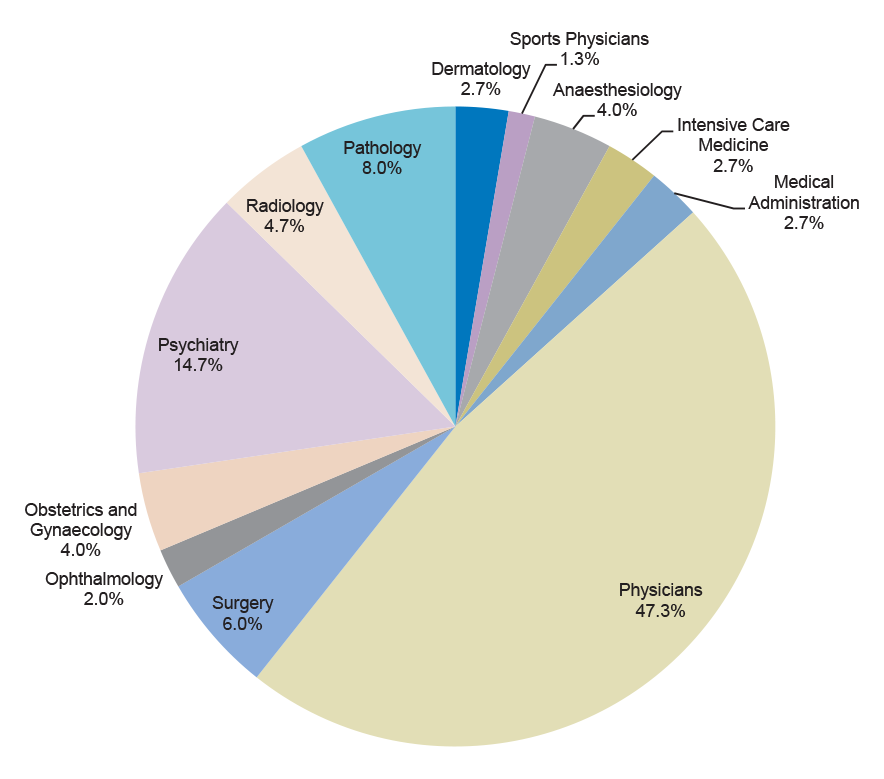

1.22 The distribution of STP training positions by medical speciality is shown in Figure 1.3. Some 40.9 per cent of training positions are in specialties that fall within the auspices of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. These cover a broad range of specialties, including public health medicine, paediatrics, geriatric medicine, medical oncology and cardiology. The significant proportion of psychiatry training positions (18.2 per cent) is consistent with the increased emphasis on mental health in Australian health policy in recent years.

Figure 1.3: Funded STP training positions 2010–14 by medical specialty

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Health data.

Note: Percentages do not equal 100 per cent due to rounding up and down of original data. Not shown are the two training positions funded through the STP that are administered by the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. These represent 0.2 per cent of all STP training positions.

Delivery of other activities through the Specialist Training Program

Emergency Department Workforce (Doctors and Nurses)

1.23 In July 2010, the then Australian Government announced the $96 million Emergency Department Workforce (Doctors and Nurses) measure. This was intended to increase the capacity of the healthcare sector to train emergency department specialists, nurses and support staff, as well as training general practitioners in emergency medicine.

1.24 A significant component of this measure has been delivered through the STP. Grant applications for new training positions for specialist trainees specialising in emergency medicine have been considered through the annual STP funding rounds.71 Each year, 22 additional training positions have been funded through this process—these are additional to the 900 training positions targeted by the STP process. During the January to June 2014 reporting period, 87 training positions were filled72, an outcome very close to the target of 90 training positions specified in the relevant funding agreement.73 The grants are administered through a funding agreement between Health and the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) using the STP model, although ACEM’s reporting obligations are slightly different to the other colleges.74

Specialist Training in the Tasmanian public health system

1.25 In June 2012, the Australian Government announced a $325 million Tasmanian ‘health assistance’ package. One element of the package was the $39.6 million Training more Specialist Doctors in Tasmania initiative (the ‘Tasmanian project’), which provided targeted grants to specifically address the public health needs of Tasmania and the medical specialist workforce in Tasmania’s public hospitals.75 Tasmania’s difficulty in recruiting and retaining its health workforce, including specialist trainees and specialists, was a key issue in the 2004 review of the Tasmanian health system by an expert advisory group.76 The provision of specialist services also featured in the 2012 preliminary report of The Commission on Delivery of Health Services in Tasmania.77

1.26 Following discussions between Health, the Tasmanian Department of Health and Human Services, Tasmanian regional health organisations and colleges, a detailed implementation plan for the Tasmanian project was approved by the Australian Health Minister in June 2013. The project involves Health providing grants to fund an initial 38 FTE specialist trainees and 10.7 FTE specialist supervisor positions in specified settings in the Tasmanian public sector health system in 2013–14, rising to 51 FTE and 14.5 FTE positions in 2015–16.78 The Tasmanian project explicitly funds the full cost of the relevant positions.79 On a FTE basis, this equates to around $120 000–180 000 per year for a specialist trainee, depending on their speciality and seniority, and an average of $365 000 for a specialist supervisor.

1.27 STP funding agreements were amended in 2013 to provide for delivery and administration of Tasmanian project funding through the agreements. As is the case for STP funds, Tasmanian project funds are administered by the relevant college, but there are different reporting requirements and payment schedules applying to the Tasmanian project funds. The colleges do not receive further administration funding for the Tasmanian project over and above the STP funding that they receive from Health.

1.28 As at June 2014, progress in filling funded Tasmanian positions has been relatively slow. In part, this was due to a previously unrecognised legal issue concerning medical indemnity, with resolution of this matter also delayed by a change of government in Tasmania in March 2014. During the January to June 2014 reporting period, 31.35 FTE specialist trainees and 7.46 FTE supervisors were in place, around 80 per cent of the target for 2013–14.

Grants administration framework

1.29 The STP is subject to the Australian Government’s framework for grants administration, which has operated since 2009. Commonwealth Grant Guidelines were introduced under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and Financial Management and Accountability Regulations (FMA Regulations) in July 2009 and updated in June 2013. Since July 2014, the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines have operated pursuant to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and related Rules. Since 2009, the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines and subsequently the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines have outlined a generally consistent legislative, policy and reporting framework for administering grants, and seven key principles for better grants administration. For the purposes of this audit, clear reference is made to which set of guidelines and/or rules (2009, 2013 or 2014) are relevant to the discussion of Health’s administration of the STP at any one time.

Health grants policy

1.30 In 2011, following the completion of a review of administrative arrangements in the Health and Ageing portfolio, the Australian Government decided to implement a range of changes within the portfolio, including consolidating 159 programs (many of them grant programs) into 18 internal ‘flexible funds’.80 The flexible funds concept was intended to ‘reduce red tape, provide increased flexibility to respond to emerging issues and deliver better value with public money’81 The STP falls within one of these flexible funds, the Health Workforce Fund. The primary objective of the Health Workforce Fund is to strengthen the capacity of the health workforce to deliver high quality care.82 Policy responsibility for the STP, as for other Health Workforce Fund matters, lies with the department’s Health Workforce Division. However, administration of the STP funding agreements, including the assessment of college reporting and the authorisation of progress payments, is undertaken by the department’s Grant Services Division.83

Previous reviews of the Specialist Training Program and specialist training

1.31 The ANAO has not previously examined the STP. ANAO Performance Audit Report No.34 2010–11 General Practice Education and Training examined the management of general practice vocational education and training programs by General Practice Education and Training Limited (GPET), then a Commonwealth company.

1.32 A review of Health’s administration of the funding agreement with one of the colleges in receipt of STP grant funding was carried out by the department’s internal audit unit in 2012. The review indicated that ‘substantial improvement’ was required in key aspects of the department’s administration. Key findings related to unspent grant funds, a substantial shortfall in the number of training positions actually filled, and inconsistencies in financial reporting.

1.33 In 2012, the then Australian Government commissioned a review (the Mason Review) to assess the appropriateness, effectiveness and efficiency of the health workforce programs and activities, and their alignment with Australia’s workforce priorities.84 The review’s April 2013 report observed that:

The STP has been highly successful in extending vocational training into new settings, particularly in the rural and private sectors. It has also demonstrated that specialist colleges can take a flexible approach to accrediting new positions and to supporting networked training arrangements involving multiple health care settings, sometimes in different regions.85

1.34 However, the review also made some observations about career pathways for medical graduates wishing to specialise, and recommended a full review of the STP to inform its future direction and consider whether existing training positions were meeting the program’s objectives.

1.35 Observations about the overall coordination of training pathways for specialists were also made by Health Workforce Australia in its 2012 report Health Workforce 2025:

While better organised and targeted at a national level, the Commonwealth [specialist and GP training programs] lack the requisite level of coordination and alignment with state and territory approaches to best leverage the collective tax payer funded training investments of both levels of government. Rectifying these shortcomings is essential to achieving the long-term workforce outcomes required.86

1.36 The coordination of medical training is being considered through the National Medical Training Advisory Network, formed in 2012 under Health Workforce Australia.87 Health advised that the National Medical Training Advisory Network is developing a series of rolling medical training plans, including in relation to specialists, to inform the Australian Government, health and education sectors.88 The department further advised that the first specialist training plan (for psychiatrists) is expected to be provided to Health Ministers for their consideration around February or March 2015.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.37 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s (Health) administration of the Specialist Training Program (STP). The audit focused on key aspects of Health’s administration of the STP since the consolidation of funding programs in 2009, and the achievement of key program targets and objectives. To assess the department’s grants administration, the ANAO focused on the fourth annual grant funding round (the 2014 round) which was completed in December 2013 and funded training positions from the beginning of 2014.

1.38 The audit methodology involved:

- conducting over 30 interviews with primary stakeholders of the STP, including specialist medical colleges, state health services, the Australian Medical Association, and settings that received STP grants;

- undertaking a detailed review of key aspects of the application and assessment process for the 2014 funding round, including how Health handled the assessment results received from the colleges and jurisdictions;

- reviewing the process through which existing funding agreements were varied to take account of the outcomes of the 2014 funding round; and

- examining college reporting for 2013–14, Health’s analysis of that reporting and the making of progress payments.

1.39 The audit reviewed Health’s administration of the STP against the Australian Government’s resource management and grants frameworks and the ANAO’s grants administration better practice guide.89

1.40 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $450 140.

Report structure

1.41 The structure of the audit report is outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Structure of the audit report

|

Chapter 2 – Assessment and Selection of Applications |

Examines the conduct of the 2014 Specialist Training Program funding round, including the development of program guidelines and funding priorities, the application, assessment and selection process. |

|

Chapter 3 – Administration of Funding Agreements |

Examines Health’s administration of the Specialist Training Program funding agreements with the specialist medical colleges. |

|

Chapter 4 – Program Performance and Evaluation |

Examines performance monitoring and evaluation for the Specialist Training Program. |

2. Assessment and Selection of Applications

This chapter examines the conduct of the 2014 Specialist Training Program funding round, including the development of program guidelines and funding priorities, the application, assessment and selection process.

Introduction

2.1 The 2014 funding round was the fourth to be conducted following the Australian Government’s decision in 2010 to significantly expand the Specialist Training Program (STP). The 2014 round was intended to fund an additional 150 training positions, so as to bring the total number of STP training positions up to the target of 900.

2.2 The application, assessment and selection process for the 2014 funding round broadly followed the model established in previous rounds. The only significant change was that applications were to be completed and submitted electronically utilising a ‘smartform’, with storage and processing of the applications occurring through an existing Department of Social Services (Social Services) online funding management system, FOFMS. This process was intended to improve Health’s grants administration by making it easier to apply and achieving efficiencies in the department’s handling of applications during the assessment and selection stages.

Development of grant guidelines and application documentation

2.3 Under the Australian Government’s grants framework, all grant activities must be administered according to a set of approved guidelines. These guidelines must also be made publicly available.90 The STP guidelines were originally developed by Health in 2009 and subsequently approved by the Expenditure Review Committee of Cabinet in December 2009, as then required by Australian Government policy. Consistent with changes in Australian Government policy, subsequent revisions of the STP guidelines (including in relation to the 2014 round) were subject to a risk-based assessment, rather than Expenditure Review Committee consideration, involving consultation with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the then Department of Finance and Deregulation.

2.4 The STP grant guidelines were subsequently revised and renamed as the STP Operational Framework (Operational Framework) in 2011.91 The Operational Framework sets out: the program objectives and expected outcomes; governance arrangements; available funding amounts; eligibility requirements; and an overview of the application and assessment process. The Operational Framework is supplemented by the STP Priority Framework (Priority Framework), which sets out the funding priorities for each round.

2.5 Stakeholder input into the Operational Framework and Priority Framework for the 2014 round was received through the Medical Training Review Panel. In addition, work by Health Workforce Australia informed the development of the Priority Framework.92

2.6 Priorities for the 2014 round were:

- private sector healthcare settings;

- settings in regional, rural and remote areas;

- non-hospital settings including aged care, community health and aboriginal medical services;

- specific areas of medicine (obstetrics and gynaecology, ophthalmology, anatomical pathology, diagnostic radiology, radiation oncology, medical oncology, geriatric medicine and psychiatry);

- generalist training93; and

- dual training.94

2.7 In addition, the Priority Framework specified that preference would be given in the assessment process to training positions which demonstrated:

- their capacity to be filled with Indigenous trainees;

- specialist trainee involvement with clinical academic research or teaching junior doctors and/or medical students; or

- capacity for an individual trainee to complete the majority of training requirements for Fellowship95 in an on-going position in a rural, regional or remote setting.

2.8 The Priority Framework for the 2014 round was approved by the Minister for Health in early March 2013. As with the previous round, the Minister delegated authority to approve the 2014 round application documentation to the department’s relevant First Assistant Secretary. The Minister also delegated authority to the First Assistant Secretary to approve the ‘outcomes’ of the round—that is, the selection of applications to be funded. In seeking the Minister’s approval, the department advised that ‘the Priority Framework is the key document that determines the composition of the outcomes’ with the actual approval of outcomes being ‘essentially administrative, as the assessment is based on the recommendations from the colleges and [state] health services’.

2.9 Immediately after receiving the Minister’s approval, the First Assistant Secretary approved the application documentation. This documentation included both public material (the Operational Framework, the Priority Framework, the application form and the associated guidance material for applicants) as well as the internal assessment plan. The documentation was also reviewed by Health’s internal grants advisory area96, although the relevant clearance indicates the review was done before the assessment plan was drafted. Other than a slightly different set of priorities, the only material change in the 2014 assessment plan over the 2013 round was the insertion of a section on ‘probity, accountability and ethics’.

Application process

2.10 As in previous rounds, a broad range of organisations were eligible under the Operational Framework to apply for an STP grant, including medical education providers, state health services (including local hospital networks and regional hospitals), community health organisations, private healthcare organisations and settings, and Aboriginal community–controlled health services.

2.11 The application process opened on 20 March 2013 and closed on 1 May 2013. Stakeholders advised the ANAO that the opening of the 2014 round was well publicised amongst potential applicants, including through the colleges advising their Fellows and other contacts. Stakeholders also considered that the six week period was generally sufficient to develop an application with all necessary supporting documentation97 and the information required in the application was proportionate to the nature of the grants on offer and the objectives of the STP. Some 467 applications were received for the 150 training positions on offer, with another 44 applications for the 22 Emergency Department Workforce training positions.98 The number of applications was similar to previous rounds, indicating on-going demand for STP funding.

Use of shared services to support the 2014 round

2.12 As noted by the 2014 National Commission of Audit99, one way that agencies can achieve efficiencies and reduce costs is through the appropriate use of shared services. Shared services involve the single provision of particular functions to more than one agency. They commonly cover activities in the areas of human resources, information management, communication, technology, procurement and financial management.

2.13 Since 2005, the Department of Social Services100 has administered the FaHCSIA Online Funding Management System (FOFMS). One of the main capabilities of FOFMS is the administration of grant activities. In 2012, under an agreement with Social Services, Health started to progressively roll out the use of FOFMS to manage a range of payments it administered.101

2.14 In late 2012, Health decided to use FOFMS to support the upcoming STP 2014 funding round. This involved the development of a tailored ‘smartform’ by Social Services102 that allowed applicants to complete and submit applications electronically, including letters of support from the relevant college and the local hospital network. Development of the smartform and integrated FOFMS process took place from October 2012 to March 2013. It was originally anticipated that the project would enable applications to open around early March, however the operational smartform was not delivered to Health until 18 March 2013.

2.15 Stakeholders advised the ANAO that they generally considered the electronic application process to be an improvement on previous rounds, although some problems were encountered when unexplained error messages were received when attempting to complete the form or where there were difficulties in attaching the required supporting documentation.

2.16 However, a number of more significant technical problems arose when receiving and processing applications, which reduced the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the application process. Notably, FOFMS experienced an outage on the day immediately before applications closed, and applications could not be submitted during this time. Some applicants instead emailed applications to the Health STP mailbox, and the volume of data caused the mailbox to crash. As a consequence, these applications had to be manually loaded into FOFMS by departmental staff. Due to the various technical issues encountered, a large number of duplicate applications were stored in and extracted from FOFMS, requiring significant work by departmental staff to identify which applications were duplicates.103 Further, Health had anticipated that it could implement automated screening of ineligible applications by FOFMS—for example, where applications did not include the required letters of support—but the technical problems precluded this.

2.17 A post-implementation review of the project by Social Services, with the involvement of Health, resulted in 23 recommendations intended to inform any future activity of this sort. Further development of the smartform application concept to support a FOFMS-based grants funding round for the Rural and Regional Teaching Infrastructure Program was undertaken by Health in 2014. A specific risk management process, derived directly from the review of the STP pilot, and involving more extensive testing, training and technical support, was developed to inform the use of FOFMS for the Rural and Regional Teaching Infrastructure Program funding round. However, in October 2014, Health advised the ANAO that the Rural and Regional Teaching Infrastructure Program round, which was due to open for applications in September 2014, did not go ahead as the program was put ‘on hold’.

Assessment process

2.18 A key consideration in administering granting activities is to implement a selection process that identifies and recommends for funding those applications that will provide greatest value with public money in the context of government objectives for the granting activity, as set out in the grant guidelines.104 Well-designed assessment processes can provide confidence that decision-makers have equitably and transparently selected applicants that best represent value for public money in the context of the program objectives and outcomes.105

Assessment criteria

2.19 The instructions provided to applicants for completing the application form stated:

Each eligible application will be assessed by:

- the relevant specialist medical college for rating in terms of the position’s ability to meet the appropriate educational imperative; and

- the relevant state or territory government for rating in terms of jurisdictional areas of workforce need.

These assessments will be provided to the Department of Health and Ageing who will collate assessment results for the decision maker. The outcome of the 2014 STP Application Round will be based on the 2014 Priorities and further application weightings as detailed in the 2014 STP Priority Framework (Attachment B). These weightings are in no particular order. Additional information may be sought from the relevant college or jurisdiction to assist with this process.

2.20 Other sections of the lengthy instructions indicated that the colleges and state health services would also be involved in assessing applications against the Priority Framework, and would not be restricted to assessing educational and workforce need aspects.

2.21 In summary, applications would be assessed by third parties—the colleges and state health services—and the assessments collated by the department prior to consideration by a departmental decision-maker.

Assessment of applications by the colleges and state health services

2.22 Health’s internal assessment plan provided for an initial screening of applications by the department against mandatory requirements. However, the initial screening did not occur due to the problems with FOFMS, discussed above, and all applications were accepted as compliant and proceeded to assessment. 106

2.23 The assessment process was conducted in two stages. The first stage was an assessment by the colleges and state health services. Health provided the colleges and state health services with a four–page template to assist in applying a consistent approach to assessments and a spreadsheet on which their assessment responses could be recorded. The template and spreadsheet provided for assessment against two key criteria:

- The extent to which the application met each of the Commonwealth priorities and preferences in the Priority Framework outlined in paragraph 2.6–2.7. Assessment responses were required to indicate ‘yes’ or ‘no’ against each priority and preference.

- An overall ‘global rating’ of the application using a four point sliding scale—strong support, moderate support, minimal support or no support. Health’s advice to the colleges and state health services was that, in addition to the application’s strength in addressing the Priority Framework, the global rating should reflect (in the case of the state health services assessments) ‘the benefit to health services’ and (for college assessments) the ‘educational merit’ of the application.107

2.24 Applications were provided to the relevant colleges and state health services by Health on 17 May 2013.108 Assessment responses were generally returned to the department by mid-June, although one was not received until late June.109

2.25 The colleges and state health services advised the ANAO that they took a number of different approaches to how they assessed applications, including through established or ad hoc committees, providing the applications to local health networks or, in the case of the colleges, having senior officers or Fellows of the college advise on the applications. Similarly, the approaches adopted by the colleges and state health services in managing potential conflicts of interest varied. Most colleges and state health services told the ANAO that either formal or informal mechanisms were in place to manage the risk of real or perceived conflicts of interest.110 Nonetheless, in one instance, a senior manager of a public hospital was directly involved in advising the jurisdiction’s Chief Medical Officer on the assessment of applications from the public hospital at which that manager was employed. As such, the manager had a direct interest in the outcome of these applications.

2.26 The assessment documentation provided to colleges and state health services by Health did not address conflict of interest issues. Health advised the ANAO that:

The Department did not specifically request the colleges/jurisdictions to ensure that reasonable conflict of interest provisions were in place for the 2014 funding round. It should be noted that most colleges and jurisdictions had completed three assessment processes before with the operational framework and assessment guidelines distributed to the colleges/jurisdictions clearly explaining roles and included explanatory notes. The Invitation to Apply [documentation] also included a section on how the applications would be assessed and described the STP Complaints Handling Procedures.

No issues have been raised with the Department about possible conflict of interest issues arising during the 2014 funding round.

2.27 Since its introduction in 2009, the Australian Government’s grants administration framework has consistently highlighted the need to manage the risk of real or perceived conflicts of interest.111 A recent ANAO performance audit of Commonwealth entities reviewed how conflicts of interests were managed for grants programs where applications were subject to assessment by third parties.112 That audit observed that by its very nature, third-party assessment through peer review processes presents inherent conflict of interest issues. Appropriate management is therefore necessary to satisfy grants framework requirements that agencies ensure the impartiality of decision-making.113 While Health was the ultimate decision-maker regarding the selection of successful applicants, the college and state health services assessments informed Health’s decisions and hence funding outcomes. Should any future funding rounds be conducted and assessed in a similar way, there would be merit in the department providing appropriate guidance to colleges and state health services regarding its expectations around the management of potential conflicts of interest.

Calculation of scores by Health

2.28 The second stage of the assessment was undertaken by Health. The assessment plan provided that, subject to receiving at least a moderate global rating from both the college and state health services, applications would be assessed against the Priority Framework with the ‘final ranking based on the number of priorities the proposed training position addresses’.

2.29 In fact, all applications were assessed against the Priority Framework. As in the previous round, Health did this by taking the college and state health services assessment responses—relating to whether individual applications met the priorities and preferences set out in the Priority Framework—and converting them into a score. Table 2.1 shows the relative weighting of the various priorities and preferences used to calculate an applicant’s score. The weightings were not included in the application documents provided to applicants or the departmental assessment plan.

Table 2.1: Relative weighting of priorities and preferences

|

Priority or preference |

Score |

|

Priority setting |

3 points |

|

Priority specialty |

1 point |

|

Generalist training |

2 points |

|

Dual training |

1 point |

|

Indigenous health component or commitment to support indigenous trainee |

2 points |

|

Trainee involved in teaching or research |

1 point |

|

Majority of Fellowship training requirement able to be completed in a rural, regional or remote location |

2 points |

|

Maximum total score |

12 points |

Source: 2014 round Health assessment report.

Notes: A priority setting means a setting in the private health sector, in a regional, rural or remote area, or an aged care, community health or Aboriginal medical service or facility.

2.30 By the end of the second stage of assessment, each application had received two scores out of 12 from Health: one based on the college assessment, and one on the relevant state health service assessment.

2.31 To assess the accuracy of Health’s calculation of scores, the ANAO replicated this scoring process based on the Health weightings reported in Table 2.1. The ANAO analysis was based on the college and state health service assessment responses for 449 out of 467 applications assessed in the 2014 round.114 The analysis identified 178 applications (39.6 per cent of the applications included in the ANAO analysis) in which the score recorded by Health on its assessment database varied from that calculated by the ANAO.

2.32 The ANAO raised the issue of variances with Health, as there was nothing in the assessment report or other records examined by the ANAO to explain the variances. Health advised that for some applications, the scores initially calculated by the departmental assessment team (based on the college assessment response) were different to those calculated from the state health service assessment response. For example, using the weightings in Table 2.1, a college assessment response might equate to a score of eight, but the relevant state health service assessment for the same application might only equate to a score of six. In effect, this meant that the relevant college and state health service had different views on the extent to which an application met the various priorities and preferences contained in the Priority Framework.

2.33 Health advised the ANAO that the differences in the calculated scores had prompted the department’s assessment team to review the ‘initial’ scores of those applications receiving either strong or moderate global ratings, totalling around 250 applications. Following this review, the Health team then assigned a ‘final’ score to the application that they considered most accurately reflected the information in the application. In relation to this ‘review and rescoring’ procedure, Health was able to provide the ANAO with working papers that recorded the initially assigned application scores. However, Health did not document any of the key decisions involved in this procedure–in particular no records were kept of the specific reasons for making changes to the scores of individual applications. The department acknowledged that in hindsight, these changes should have been recorded on the assessment database. The Health assessment team advised that they could not recall any discussions with the colleges or state health services about this subsequent departmental review and rescoring process115, nor could they recall any discussion with the relevant Assistant Secretary within Health.

2.34 The department also acknowledged that there was no further quality control undertaken during the review and rescoring process and that this may have led to some variations or input errors that affected the final scores assigned by Health.

Ranking of applications by Health

2.35 Under the 2014 round, funding was available for 150 new training positions. While the global rating provided by the colleges and state health services was the primary factor in ranking applications and determining funding outcomes, the scores assigned by Health also played a role in the ranking process, and in some cases the department exercised discretion to not fund applications.116

2.36 As Table 2.2 illustrates, 147 applications of the total of 467 applications received a strong global rating by both the relevant college and state health services (a ‘strong/strong’ rating). Of these, 121 (82.3 per cent of all strong/strong applications) were ranked by Health in the ‘top 150’—that is, selected as one of the 150 applications to be offered STP grant funding.117 A further 22 strong/strong applications (15.0 per cent of all strong/strong applications) were placed on the reserve list, and four (2.7 per cent) were unsuccessful. Of the remaining 29 applications that were ranked in the top 150, all received a strong rating from the relevant college and a moderate rating from the relevant state health services, or vice-versa (a ‘strong/moderate’ rating). These 29 successful applications represented 27.1 per cent of all strong/moderate applications. The remaining 78 strong/moderate applications were placed on the reserve list.

Table 2.2: Ranking of 2014 round applications

|

Global |

Total number of applications |

Number of applications in top 150 (offered funding) |

Number of applications placed on reserve list |

Number of applications placed on unsuccessful list |

|

Strong/Strong |

147 |

121 |

22 |

4 |

|

Strong/Moderate |

107 |

29 |

78 |

0 |

|

Strong/Other |

103 |

0 |

0 |

103 |

|

Moderate/Moderate |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

|

Moderate/Other |

57 |

0 |

0 |

57 |

|

Minimal/Other |

33 |

0 |

0 |

33 |

|

Total |

467 |

150 |

120 |

197 |

Source: 2014 round Health assessment report.

Note: The term ‘Other’ in the rating column means either minimal support or no support.

2.37 As noted in paragraph 2.35, in some cases the department exercised a discretion to not fund applications. Of the 22 strong/strong rated applications that were placed on the reserve list, 13 (representing 8.8 per cent of all strong/strong applications) involved situations where the hospital or medical organisation had submitted applications for two or more training positions in the same specialty.118 In such cases, Health funded only one place in order to obtain ‘a relatively even distribution of the new training positions against the population data’, an approach which also featured in the previous (2013) funding round.119 As a result, some relatively high–scoring, strongly–rated applications were not offered funding. The remainder of the unfunded strongly–rated applications were either relatively low–scoring (between two and four), or, in the case of the four unsuccessful applications, were from Tasmanian public hospitals and were not funded on the basis that specialist training in the Tasmanian public sector was being separately supported through the Tasmanian project.

2.38 The 29 ‘strong/moderate applications ranked by Health in the top 150 had scores ranging from a high of nine to a low of five, with three applications scoring five. However there were also 29 applications with the same ‘strong/moderate’ rating that scored either six or seven and which were placed on the reserve list. Health was unable to provide any specific evidence as to why the three applications scoring five were funded in preference to the 29 applications scoring six or seven.

Transparency of the scoring and ranking process

2.39 As noted in paragraph 2.8, Health had advised its Minister in March 2013 that the approval of assessment outcomes by the departmental delegate was ‘essentially administrative, as the assessment is based on the recommendations from the colleges and [state] health services’. While the college and state health service global ratings were the single most influential factor in deciding which applications received funding, the relevant score subsequently assigned by Health was also a factor. As such, the assessment team’s decision to change the initial scores across a substantial proportion of the applications through a review and rescoring procedure that was not documented was a feature of the assessment process.

2.40 Health’s approach was inconsistent with information provided to applicants—in the instructions for completing the program application form—that the department would collate assessment results received from the state health services and colleges.120 The failure to document the additional review and rescoring procedure in the program guidelines and instructions; the lack of record–keeping regarding the reasons for changing initial assessment scores; and the failure to provide advice on the procedure in the assessment report121 provided to the decision-maker, meant that the procedure was not consistent with sound practice.122 As discussed, Health acknowledged also that that there were no specific quality control measures in place for the additional review and rescoring, further increasing the risks introduced by the procedure.

2.41 As a result of the variances observed by the ANAO, the department undertook a complete rescoring of applications for the 2014 round.123 As at December 2014, this work remained incomplete.

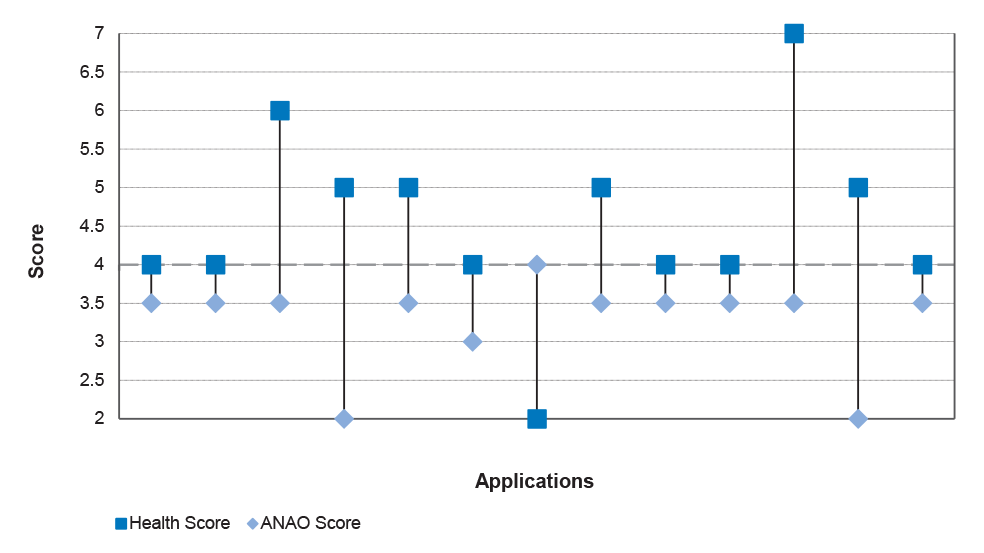

2.42 Assessing the impact of the undocumented review and rescoring process was made difficult as there was not always a strict ‘cut off’ score for funding. However, there were 12 applications in the top 150 for which the scores calculated by the ANAO124 were between two and three and a half points out of 12 but were ultimately assigned a score by Health of between four and seven. In these cases, the department’s rescoring increased the prospects of applications being funded. Conversely, there was one application on the reserve list (which received a strong/strong rating) where the ANAO calculated a score of four but Health assigned a score of two. Had that application been assigned a score of four, it may have been placed in the top 150 and offered funding.

2.43 The ANAO’s analysis of the rescoring of the 13 applications discussed above (which together represented 2.8 per cent of the 467 applications received in the 2014 round) is illustrated in Figure 2.1. The hatched horizontal line at the score of four represents the general minimum score for applications placed in the top 150. As the figure shows, there were 12 applications where the score calculated by the ANAO, based on the college and state health service assessment responses (the ANAO score), was under four, but which were given a final score by Health of four or more; with one application having an ANAO score of four but a Health score of two.

Figure 2.1: Effect of rescoring process on selected applications

Source: ANAO analysis of college and state health services assessment responses and Health data.

2.44 In addition to the review and rescoring process, the department also decided not to fund some applications that received a strong/strong global rating and a relatively high score.125 As discussed in paragraph 2.37, 13 applications were placed on the reserve list where the setting had submitted applications for two or more training positions in the same specialty.126 In such cases, Health funded only one place in order to obtain ‘a relatively even distribution of the new training positions against the population data’. In adopting this approach, Health effectively applied a selection criterion that was not documented in the 2014 round application form or other explanatory material available to applicants. In adopting this approach, which also featured in the previous (2013) funding round127, the department effectively applied a selection criterion that was not documented in the application form or other explanatory material made available to applicants.128 Although the program’s funding priorities, which underpinned the assessment criteria, were reviewed between rounds, Health did not take the opportunity to incorporate a reference to the approach adopted on population distribution in the 2014 round application form or explanatory material. Nevertheless, when considered in the context of the program’s intended outcomes (which include achieving a better geographical distribution of specialist services) the department’s approach in relation to this matter was not unreasonable.

Recommendation No.1

2.45 To improve transparency and equity in the administration of grants, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

- review program guidelines and assessment criteria at the conclusion of grant funding rounds, to incorporate lessons learned; and

- provide operational guidance to staff on moderation or other quality control processes to be applied where applications have been assessed by third-party advisers.

Department of Health Response:

2.46 Agreed.

2014 round outcomes

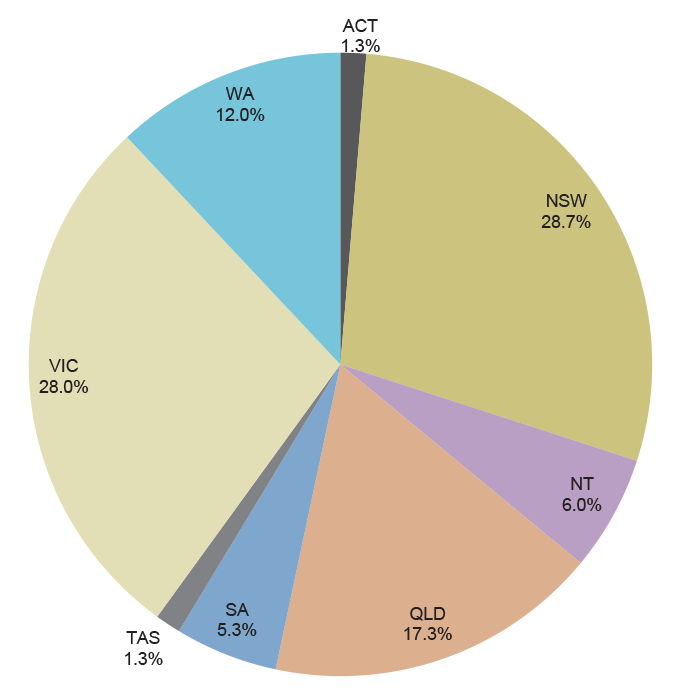

2.47 A total of 150 STP training positions were funded nationally in the 2014 round. Figure 2.2 shows the proportion of training positions located in each state and territory jurisdiction. The proportions broadly correspond to each state and territory’s share of population.129 However, the Northern Territory was funded for nine training positions; representing six per cent of all 150 training positions, in contrast to its population share of about one per cent.

Figure 2.2: Funded 2014 round STP training positions by State and Territory

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Health data.