Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme.

Summary

Introduction

1. The provision of legal assistance to disadvantaged persons is recognised as a key element of equitable and accessible justice systems. In general, government-funded legal assistance arrangements aim to provide people with better and early access to information and services that can help them prevent and resolve disputes, and receive appropriate advice and assistance, no matter how they enter the justice system. This support may occur through legal assistance services available for all eligible members of the community or through services specifically directed at particular matters or groups. The Australian Government funds legal assistance services including state and territory run legal aid commissions; community legal centres; family violence prevention legal services and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services.

2. In the Australian context, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) people are generally over-represented in the criminal justice system, and adverse contact with the justice system is recognised as contributing more broadly to disadvantage. The Australian Government has funded Indigenous-specific legal assistance services since 1971. Providing Indigenous people with access to justice that is effective, inclusive, responsive, equitable and efficient remains a priority within the Australian Government’s approach to improving the ability of the justice system to meet the needs of Indigenous people.1

3. Relative to other Australians, Indigenous people are considered to face particular barriers when accessing law and justice services including: financial capacity; language barriers; and mainstream services being less culturally sensitive or not delivering services to more remote parts of Australia. Other issues such as anxiety, lack of familiarity, fear of detention, and reluctance to use available services are seen as further contributors to Indigenous people not fully accessing mainstream legal services. In this setting, a cycle of disadvantage can arise as barriers to justice lead to poorer outcomes and high imprisonment rates, which in turn negatively affects wellbeing, opportunity and community safety—potentially resulting in further engagement with the justice system.

4. State and territory governments are responsible for the operation, and funding, of the law and justice sector in their jurisdictions. Within this arrangement, the Australian Government administers the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme (ILAP). Under the program, legal assistance services are provided by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services (referred to in this report as ILAP service providers) specifically for Indigenous people—mostly with respect to criminal law but also servicing family and civil law. ILAP service providers are Indigenous-controlled, community based, not-for-profit organisations responsible for the delivery of legal assistance services. Since 1971 the numbers of providers and their funding arrangements have varied. Under the funding arrangements in place since 2011, services have been delivered by eight providers which, with some exceptions, are located in each state and territory.2 Each provider maintains local service outlets in urban, regional and remote areas and as at December 2014 there were 80 outlets nationally.

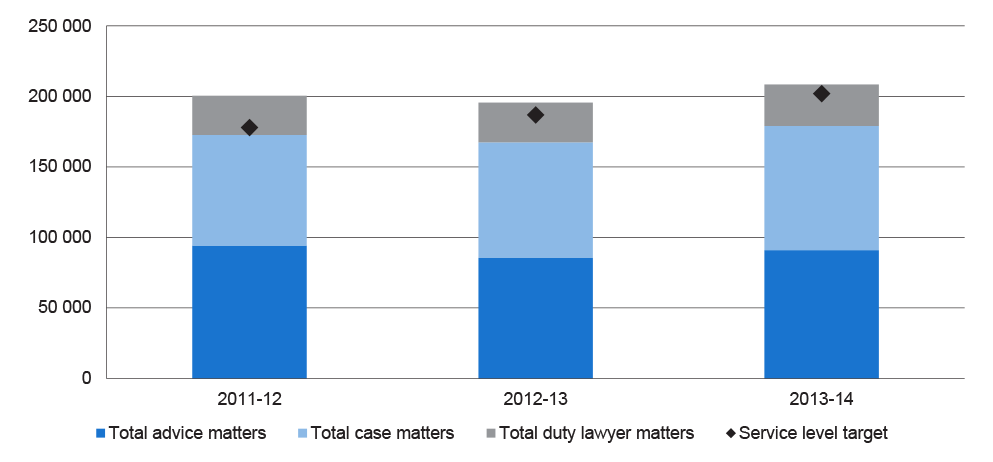

5. The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) has been responsible for administering ILAP since 2004. Reflecting the overall policy intent to facilitate access to justice services, the objective of ILAP is to:

deliver culturally sensitive, responsive, respectful, accessible, equitable and effective legal assistance and related services to Indigenous Australians so that they can fully exercise their legal rights as Australian citizens…3

6. Ongoing concerns about the high rates of Indigenous imprisonment and deaths in custody have resulted in legal assistance services being mainly focussed on criminal law matters and on supporting Indigenous people at risk of being detained or imprisoned.4 Although ILAP service providers are funded by the Australian Government, the matters they deal with generally arise from the laws of the states and territories, and providers therefore work through the state and territory justice systems.

7. How an Indigenous person accesses legal services provided through ILAP will depend on an individual’s legal needs and circumstances. An individual’s legal need may involve a civil, criminal and/or family law matter and require legal assistance ranging from legal information and initial advice, one-off representation at a court or tribunal, known as duty lawyer assistance, or ongoing legal assistance and representation in the form of casework services. The approach to service delivery under ILAP is that when an Indigenous person has a legal problem they can seek to access legal services directly at an ILAP service provider office or outlet. In circumstances where an Indigenous person has been arrested or is being detained, providers maintain after hours telephone numbers that Indigenous people can contact. Access to duty lawyer services is also provided at some courts, including some remote area courts, where duty lawyers are available to assist Indigenous people that have to appear before court on a particular day or have been detained for criminal offences.

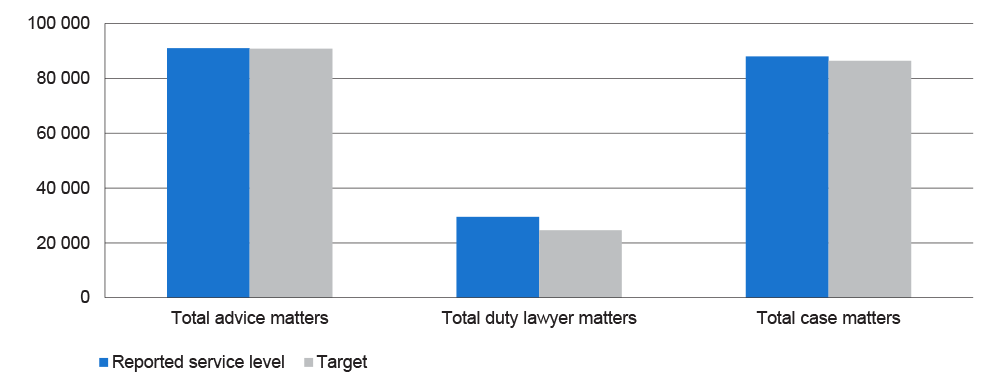

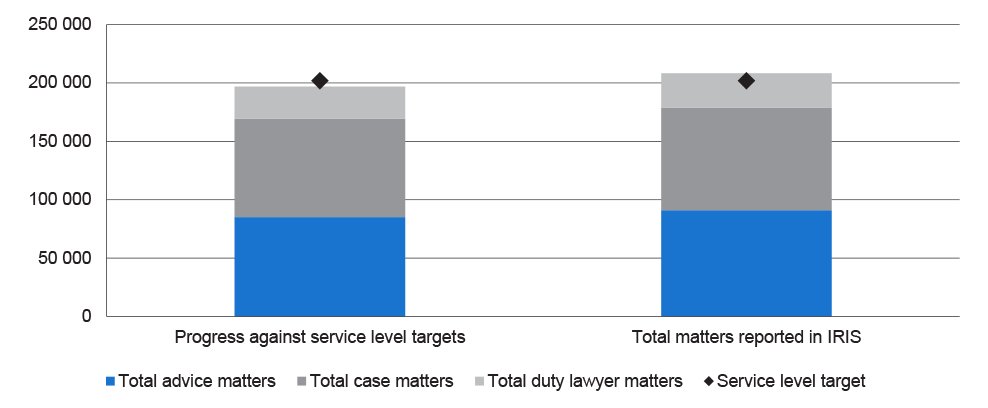

8. In 2013–14, AGD distributed $74.9 million amongst the eight ILAP service providers—each of which has a grant funding agreement with AGD until July 2015. Funding levels for each provider are determined by a funding allocation model, which considers a range of demographic and social risk factors in estimating the likely level of need for legal assistance services in the areas covered by each provider. During 2013–14, AGD reported that service providers gave 90 103 advices, undertook 29 436 duty lawyer services and conducted 86 949 cases. Australian Government funding arrangements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal assistance providers along with legal aid commissions, community legal centres and family violence prevention legal services expire on 30 June 2015. From July 2015, a new national strategic framework for all Australian Government funded legal assistance services is expected to be in place and will provide high level policy direction and set out shared national objectives and outcomes. Once agreed by the Commonwealth, state and territory ministers, the framework is expected to inform future funding agreements with service providers, including providers of Indigenous legal assistance.

Audit objectives and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme. To conclude on this objective the ANAO adopted high level criteria relating to the effectiveness of program management arrangements, AGD’s management of funding agreements, performance monitoring and reporting arrangements.

Overall conclusion

10. Access to appropriate legal assistance services is an important element of a fair and equitable legal system. Since 2011, funding through the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme (ILAP) has enabled service providers to deliver a cumulative total of 604 519 legal assistance services, or an average of 201 506 per year. Over the same period, ILAP funding has enabled these service providers to operate an average of 84 outlets each year to provide services. Research undertaken by a range of government and non-government bodies indicates generally that the level of unmet demand for Indigenous legal assistance services is higher than the supply of those same services. Additionally, the Productivity Commission has reported in the 2014 Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report that between 2000 and 2013, Indigenous imprisonment rates have continued to worsen with the imprisonment rate for Indigenous adults increasing by 57.4 per cent.5 There have also been significant increases in juvenile detention rates since 2001. While these trends in themselves are not necessarily reflective of levels of access and the quality of services provided through ILAP, they do indicate that demand for Indigenous legal assistance services is high and is likely to remain so.

11. Facilitating appropriate access to justice is complex and involves a number of different institutions. For the most part, Australians interact with the justice system at the state and territory level, and accessibility is largely determined by how that justice system functions. As a result, while Australian Government support through ILAP is able to address some barriers to access, it is not able to address all factors relevant to improving access to justice for Indigenous people. Further, the demand for services arises largely from the operation of state and territory laws. In this respect, demand for Indigenous legal assistance services is not in the control of the Australian Government and can be affected significantly by changes made to state and territory laws.

12. In this context, and considering the small size of the program, the overall management approach taken by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) is reasonable. The approach recognises that there are institutional and jurisdictional differences in justice systems across Australia, and acknowledges that ILAP service providers are better placed than AGD to identify appropriate service approaches in the areas they service. Accordingly, AGD allows service providers flexibility in their planning and delivery approach. In circumstances where national programs allow for local flexibility, program management arrangements need to be designed to achieve appropriate levels of consistency. Performance information arrangements also need to be well developed to enable appropriate comparative analysis and assessment of program performance overall.

13. AGD has put in place a range of approaches to promote consistent national management of ILAP. These include a formula based funding allocation model that incorporates information specific to each jurisdiction, but assesses each jurisdiction against the same criteria and weightings to determine the funding levels to be allocated to each service provider. Expectations in relation to service delivery are promoted by the Service Delivery Directions, made available to service providers to inform the annual development of service plans, and the development of the Indigenous Quality Practice Portal designed to support the collection and analysis of relevant performance information and monitor delivery against Service Standards. Grant funding is managed through standard funding agreements that are in place with each service provider.

14. AGD’s management of ILAP has matured since it assumed responsibility for the program in 2004, and while the current management framework is reasonable overall, improvements can be made in the following areas. Firstly, to give better effect to the intent of the program to prioritise assistance to communities with the highest need, the funding allocation model, which is currently being revised by AGD, could be enhanced by the inclusion of additional social and economic indicators of disadvantage to better target available resources. Secondly, there would be benefit in developing greater consistency in relation to performance expectations. Currently, each ILAP service provider proposes targets for the number of services they expect to provide in their annual service plans, which are endorsed by AGD as part of the annual planning process. However, the definition of a service can vary between jurisdiction and AGD has not developed a benchmark level of service against which an assessment of proposed targets can be made. Further, service plans are not integrated into funding agreements, and as a result, there is no clear link between the funding amounts provided in the agreements and the expected level of performance.

15. Generally, ILAP funding agreements are compliance focussed and show only a limited performance orientation. While the reporting requirements established in the funding agreements give AGD sufficient visibility to identify issues of compliance, AGD has not always been timely in verifying or addressing matters relating to service provider compliance. Further, the focus of AGD’s program measurement and reporting is mainly on the levels of funding expended and the number of legal services delivered. This information is relevant in view of the demand-driven nature of ILAP. However, in the absence of targets or baseline information in relation to access, AGD is unable to assess whether access to justice has improved as a result of ILAP funding. Improvements to the collection, reporting and use of currently available performance information—directed towards measuring and reporting on the quality of services delivered and supported by appropriate assurance and verification mechanisms—would better enable AGD to strengthen its focus on whether the program is performing in line with expectations, and that barriers to access are being appropriately addressed.

16. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving AGD’s approach to setting and assessing performance targets.

Key findings by chapter

Program Management Arrangements (Chapter 2)

17. Program objectives for ILAP have been clearly stated in the program guidelines and focus on the provision of legal assistance services that are culturally sensitive, responsive, respectful, accessible, equitable and effective. The program’s funding strategy of using Indigenous organisations to provide these services using local outlets, is reasonably aligned with the program’s objectives, and the service usage patterns are generally consistent with the overall distribution of the Indigenous population.

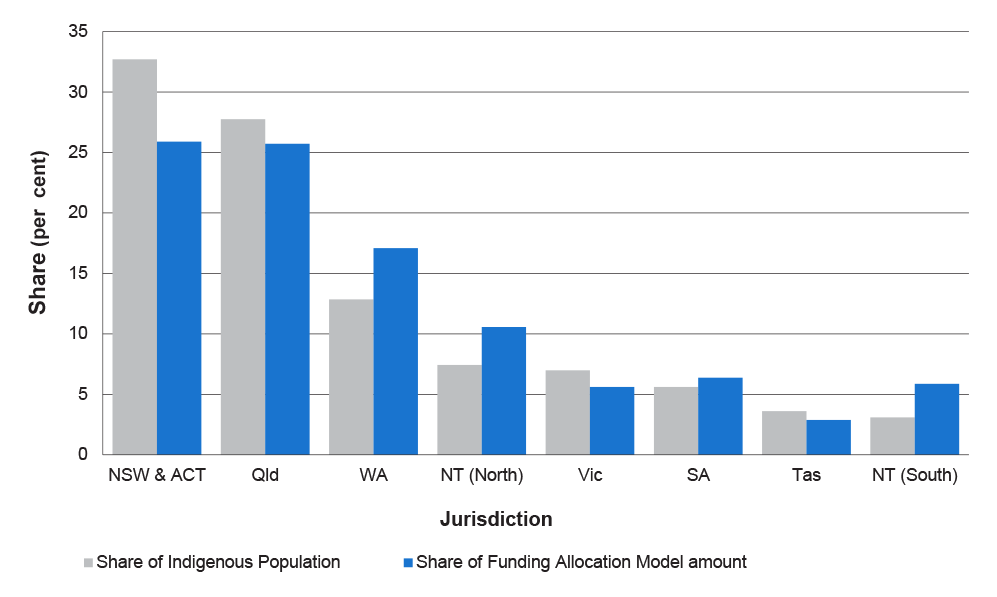

18. Allocation of funding between jurisdictions is based on the Funding Allocation Model (FAM). The FAM uses statistical information from census and other sources, and funding is allocated according to weighted factors which address the cost of service delivery, number of and demand for services, and risk of detention or imprisonment. Although a stated priority of ILAP is to deliver services to those communities with the highest need, communities have not been defined beyond the jurisdictional boundaries of service providers, and funding allocations are determined at a broader level—derived from assessing a combination of population, risk and cost factors. To date, AGD has not undertaken any significant work to determine which areas of the Indigenous community are considered to be ‘high need’, or which communities are experiencing access barriers, and the FAM currently does not include factors or indicators relating to relative disadvantage between areas.

19. Service providers are given the flexibility to prioritise where they deliver services, within the available funding. ANAO analysis of case work matters indicates that most matters are undertaken in regional areas (41.5 per cent) followed by metropolitan areas (29.6 per cent) and remote areas (28.9 per cent). Proportionately, however, the share of services relative to population is lower for urban areas with 71.1 per cent of matters delivered in metropolitan and regional areas, where 78.6 per cent of Indigenous people are located. Conversely, some 28.9 per cent of services are delivered to remote areas where 21.3 per cent of the Indigenous population is located. At a broad level, this data indicates a slight over-servicing of remote populations. However, it is likely that remote services are concentrated in areas that are relatively more accessible, which masks a more limited delivery of services in other more remote areas.

Managing Service Delivery (Chapter 3)

20. To support the management of the program, AGD has developed a grants administration framework that comprises program guidelines, funding agreements, supporting guidance and a set of reporting requirements. These arrangements support AGD in monitoring compliance with the terms of the funding agreements, but overall do not support a strong focus on performance against the objectives of the program. Key performance requirements are described at a broad level but these are not set out in the actual agreements and are managed separately through the annual service plan submitted by service providers. While in place, the comprehensiveness and quality of these plans varied across different service providers. Additionally, there are some variations in the definition of a ‘service’ across some providers which makes it difficult for AGD to assess the efficiency of service delivery consistently. The approach to annual target setting is largely based on assessing levels achieved in prior years. AGD would be better positioned when endorsing annual targets if it developed benchmark levels of performance against which proposed service targets could be assessed.

21. Monitoring arrangements rest on the provision by service providers of a range of reports covering service plans, service quality and financial performance. In an effort to simplify reporting requirements, AGD developed the Indigenous Justice Quality Practice Portal, an online portal through which service providers submit their reports. This is a positive initiative, however, while the system provides AGD with a high level view of compliance it gives generally limited visibility over the details of actual performance against service standards. Overall, AGD’s arrangements for managing the funding agreements are reasonable in their design, but would be strengthened by introducing a greater focus on expected results in the funding agreements, and periodic assurance by AGD of relevant performance data submitted by providers to inform assessments of improvements in access, the quality of services provided and the performance of service provider organisations.

Program Performance Monitoring and Reporting (Chapter 4)

22. Program performance information collected by AGD is currently focused on the quantity and type of services delivered, and whether providers are complying with their funding agreements. These reporting arrangements are useful in respect to ascertaining levels of activity, location of services and types of legal assistance matters addressed. However, they are not sufficiently comprehensive to provide AGD with an appropriate level of visibility over other more qualitative aspects of program performance, including whether services are of high quality, appropriate, accessible and equitable.

23. While it is reasonable to expect that the provision of legal assistance services through ILAP would contribute to improved access to justice outcomes for Indigenous people, no baseline information on existing levels of access, or desired levels of access, has been collected by AGD. As a result the performance reporting framework is not able to generate robust and meaningful program performance information that gauges whether access is improving, and the contribution of ILAP service providers to this result.

Summary of entity response

24. AGD’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The department welcomes the performance audit of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme, and largely agrees with the findings and recommendations of the report.

The report presents an accurate view of the unique challenges faced by the Attorney-General’s Department in administering the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme and ensuring services are delivered in culturally sensitive and accessible manner, so that Indigenous Australians can fully exercise their legal rights as Australian citizens.

The department is committed to working with Indigenous legal assistance providers, stakeholders and community to support the delivery of quality legal assistance services and achieving the outcomes of the programme.

The findings in this report will assist in the future effective delivery of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 4.37 |

To support a stronger performance focus in the development of future funding arrangements, ANAO recommends AGD further develops its performance measurement and reporting framework by: (a) developing and incorporating baseline data, against which service targets could be assessed and changes measured; and (b) strengthening systems and processes to capture, monitor and report data, including conducting periodic data integrity checks to assess the accuracy and reliability of the data collected. AGD Response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme. The audit objective, scope, criteria, methodology and report structure are also presented.

Background

1.1 Adverse contact with the justice system is recognised as having a strong, perpetuating influence on Indigenous disadvantage. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner noted in 2013:

While we have neglected targets for justice issues, there has been a danger that this has undermined our efforts to meet the other targets set in the Closing the Gap agenda. This is because we know that imprisonment has such a profoundly destructive impact, not only on individuals, but on the entire community. It affects areas such as health, housing, education and employment—all the building blocks of creating stable and productive lives.6

1.2 In 1991 the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) found there were a disproportionate number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) people, compared with non-Indigenous people, in both police and prison custody.7 Despite governments around Australia making commitments in response to RCIADIC recommendations, the proportion of Indigenous people in prison has increased steadily since 1991.8

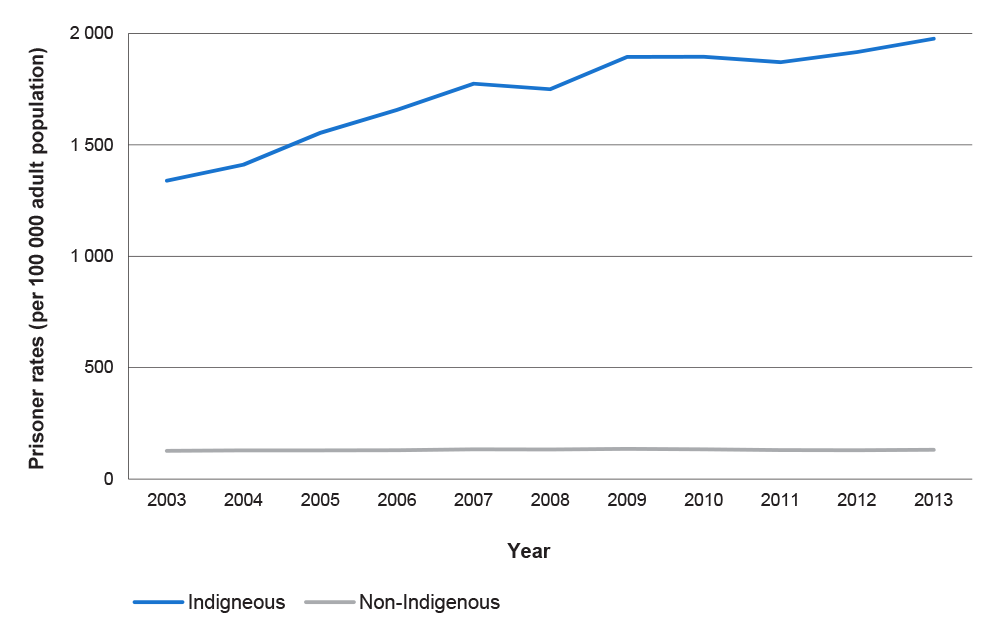

1.3 The Productivity Commission has reported in the 2014 Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report that between 2000 and 2013, Indigenous imprisonment rates continued to worsen with the imprisonment rate for Indigenous adults increasing by 57.4 per cent.9 In 2013 the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that Indigenous prisoners comprised just over a quarter (27 per cent) of the total prisoner population. The trend increase in Australia’s per capita Indigenous adult prisoner population for 2003–2013 is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Rates of adult imprisonment—Australia

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS, 4517.0 Prisoners in Australia—2013, Indigenous Status of Prisoners, Canberra, 5 March 2014 update, available from: <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/ Lookup/4517.0Main+Features12013?OpenDocument> [accessed 12 March 2014].

1.4 High rates of Indigenous imprisonment are accompanied by disproportionately high levels of expenditure on Indigenous people in the justice system. In 2012–13, total direct Indigenous-specific expenditure on building safe and supportive communities by all Australian governments was $8 billion.10 This expenditure is incurred primarily by state and territory governments in the operation and administration of their justice systems, with most expenditure relating to policing and corrective services. By comparison, the Australian Government’s component of overall expenditure is smaller and focuses on contributing to the provision of legal assistance services.11

Legal assistance arrangements in Australia

1.5 Effective legal assistance arrangements are acknowledged to provide benefits for the overall justice system. A 2009 study of the economic value of legal assistance observed that:

There is a direct relationship between the efficiency of the court and the provision of legal aid. Efficiency is achieved through the provision of information, advice, legal assistance, dispute resolution, and representation for matters that would otherwise be self-representing. Costs to the justice system are also avoided because cases are diverted from court rather than needing a hearing or decision by the court.12

1.6 The Australian Government funds various legal assistance services using different funding arrangements to assist Australians whose relative disadvantage would otherwise prevent access to justice to equitable treatment before the law.13 Services funded by the Australian Government are: legal aid commissions in each state and territory; community legal centres, family violence prevention legal services and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services. A wide range of activities have been undertaken across these legal assistance services, including: information and referral; discrete task assistance; dispute resolution; legal representation; community legal education; and policy and law reform.

National Partnership Agreement on Legal Assistance Services

1.7 Broad direction for the provision of legal assistance services is provided by the National Partnership Agreement on Legal Assistance Services (NPA) which was signed by the Australian Government and state and territory governments in June 2010. The objective of the NPA is to provide ‘a national system of legal assistance that is integrated, efficient and cost-effective, and focused on providing services to disadvantaged Australians in accordance with access to justice principles of accessibility, appropriateness, equity, efficiency and effectiveness’.14

1.8 The NPA promotes a collaborative and ‘holistic’ approach to providing services for disadvantaged Australians.15 These services consider characteristics and needs of client groups and how they will access services. Familiarity and trust, flexibility, timeliness, confidentiality and consistency have been identified as key components of effective service delivery for individuals with complex legal needs. While the NPA provides a policy framework for all types of legal assistance services, it specifically only funds state and territories for the provision of legal aid commissions. Separate funding arrangements are in place for community legal centres, family violence prevention legal services and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services. From July 2015, a new national framework for all Australian Government funded legal assistance services is expected to be in place.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services

1.9 Indigenous Australians experience a range of barriers to accessing the justice system. In many cases, legal assistance services provided by the private sector are outside the financial capacity of many Indigenous Australians, may not be delivered in a culturally sensitive way or may not be delivered in regional and remote areas. Issues such as anxiety, lack of familiarity, fear of detention, and reluctance to use mainstream legal assistance services are also considered to affect access to justice for Indigenous Australians.

1.10 The Australian Government has funded legal assistance services for Indigenous Australians since 1971. Service providers are Indigenous-controlled, community based, not-for-profit organisations. Currently, there are eight service providers that generally operate based on state jurisdictions, except in the Northern Territory where two service providers operate, and the Australian Capital Territory which is serviced by the New South Wales service provider. As at December 2014 there were 80 service provider outlets in operation nationally. The majority of service outlets (88 per cent in 2012–13) were located in regional and remote areas. In order to provide legal assistance in areas where outlets are not easily accessible, most providers have adopted an outreach service delivery model. This enables some services to be provided at circuit courts and ‘bush courts’.16

Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme

1.11 Service providers receive funding through the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme17 (ILAP) which is administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD). The objective of the program is to:

deliver culturally sensitive, responsive, respectful, accessible, equitable and effective legal assistance and related services to Indigenous Australians so that they can fully exercise their legal rights as Australian citizens …18

1.12 ILAP has been administered by AGD since 2004. Prior to this, the program had been administered by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services respectively, using grant funding arrangements.

1.13 In 2004, AGD conducted a competitive tender process for the continued provision of legal assistance services. The intention of this tender process was to improve the quality and efficiency of service delivery by ILAP service providers.19 As a result of the tender, 25 organisations, each of which had an individual grant agreement with AGD, were replaced by nine state or zone-wide service provider organisations operating under contracts with AGD. Another tender process in 2007–08 resulted in the further rationalisation of providers, from nine to eight, nationally. In 2011 the Government reverted to funding service providers through grant funding agreements but maintained the overall number of providers at eight. These new funding agreements were initially scheduled to run from 1 July 2011 until 30 June 2014 but were extended in 2013 to 30 June 2015.

1.14 As providers of legal services, service providers must comply with various rules and regulations governing the legal profession and practice in each state and territory. However, one service provider is not a registered legal service provider, being responsible for the delivery of other Indigenous programs in addition to ILAP. Under the relevant state’s legislation the organisation is unable to deliver legal services to third parties, and therefore outsources its legal services.

1.15 In 2013–14, approximately 84 per cent of all legal assistance matters addressed through ILAP related to (mostly state and territory based) criminal law matters. Further, in the same year, over 90 per cent of casework and duty matters were in criminal law.20 Although service providers have sought to broaden the focus of the law types they service, the primary focus of the program remains on those Indigenous people at risk of being detained in custody, reflecting concerns regarding the high Indigenous imprisonment rates.

Structure of ILAP

1.16 Between 2011 and 2013, ILAP consisted of four funding sub-programs:

- Indigenous Legal Assistance—the core activity of providing legal services to Indigenous people;

- Indigenous Test Cases (discontinued in 2012);

- Law Reform, Research and Policy Development; and

- Program Support and Development.

1.17 In late 2013, the Government announced a reduction of $43.1 million over four years across all Indigenous and non-Indigenous legal assistance programs, refocussing program activity away from policy reform and advocacy activities towards ‘front line’ legal services. Of the $43.1 million reduction in funding, $13.4 million of funding was removed from ILAP policy reform and advocacy activities over four years (2014–17). AGD advised the ANAO that while the Australian Government recognises service providers may choose to undertake such activities on their own account, these activities will not be funded by the Australian Government.

1.18 How an Indigenous person accesses legal services provided through ILAP will depend on an individual’s legal needs and circumstances. An individual’s legal need may involve a civil, criminal and/or family law matter and require legal assistance ranging from legal information and initial advice, one-off representation at a court or tribunal, known as duty lawyer assistance, or ongoing legal assistance and representation in the form of casework services. The approach to service delivery under ILAP is that when an Indigenous person has a legal problem they can seek to access legal services directly at a provider’s office or outlet. In circumstances where an Indigenous person has been arrested or is being detained, providers maintain an after hours telephone numbers that Indigenous people are able to contact. Access to duty lawyer services is provided at some courts, including some remote area courts, where duty lawyers are available to assist Indigenous people that have to appear before court on a particular day or have been detained for criminal offences.

1.19 In 2013–14, AGD distributed $74.9 million amongst the eight service providers—each of which has a grant funding agreement with AGD until July 2015. Funding levels for each provider are determined by a FAM which considers a range of demographic and social risk factors in estimating the likely level of need for legal assistance services in the areas covered by each ATSILS. During 2013–14, AGD reported that ILAP providers gave 90 103 advices, provided 29 436 duty lawyer services and conducted 86 949 cases.21 Australian Government funding arrangements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal assistance providers along with legal aid commissions, community legal centres and family violence prevention legal services expire on 30 June 2015. From July 2015, a new national strategic framework for all Australian Government funded legal assistance services is expected to be in place and will provide high level policy direction and set out shared national objectives and outcomes. Once agreed by the Commonwealth, state and territory ministers, the framework is expected to inform future funding agreements with service providers, including providers of Indigenous legal assistance.

Audit objective

1.20 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme.

Scope

1.21 This audit examined the AGD’s management of ILAP under current (2011–2015) funding arrangements. In some areas, to provide context and establish trends, the audit considered AGD’s management over a longer period. The audit did not include examination of the governance or performance of individual service providers.

Criteria

1.22 To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- program management arrangements support the achievement of program objectives;

- funding arrangements support the achievement of program objectives; and

- performance monitoring and reporting arrangements support program performance.

Audit approach

1.23 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- examined program-related information, including: key program management documentation, such as program guidelines and standard operating procedures; transactional and compliance documentation; and performance monitoring and reporting documentation;

- analysed available performance data on service delivery;

- interviewed relevant AGD program officers and managers; and

- conducted site visits and interviews with managers and staff from ILAP service providers, their peak representative body, and visited legal offices from which services are delivered.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost of $468,405.

Report structure

Table 1.1: Structure of report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Chapter 2 Program Management Arrangements |

This chapter examines the program management arrangements established by Attorney-General’s Department to support the delivery of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme. |

|

Chapter 3 Managing Service Delivery |

This chapter examines the design and management of the service delivery arrangements the Attorney-General’s Department has in place to administer funding. |

|

Chapter 4 Program Performance Monitoring and Reporting |

This chapter examines the performance monitoring and reporting arrangements that Attorney-General’s Department has established to manage and report on the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme. |

2. Program Management Arrangements

This chapter examines the program management arrangements established by Attorney-General’s Department to support the delivery of the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme.

Introduction

2.1 Sound program management arrangements underpin the effective delivery of programs. Such arrangements include developing and communicating clear objectives for a program, aligning funded activities and allocations to program objectives and managing risks to the achievement of program objectives. The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) has been administering the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme (ILAP)22 since 2004. Over this time, AGD has established supporting frameworks to implement and deliver the program. In this context the ANAO examined:

- ILAP’s program objectives;

- program funding allocations and distribution; and

- ILAP risk management.

ILAP program objectives

2.2 Clear program objectives are important to enable prioritisation of funded activities, development of consistent and targeted performance measurement arrangements and support clear reporting to Parliament and other stakeholders on the outcomes expected from funding. Reflecting the provision of legal assistance services as an ongoing, demand driven service, the objectives of ILAP are described in the ILAP program guidelines as being to: ‘…deliver culturally sensitive, responsive, respectful, accessible, equitable and effective legal assistance and related services to Indigenous Australians so that they can fully exercise their legal rights as Australian citizens.’23 The guidelines further state that priority will be given to investing in Indigenous communities with the highest need.

2.3 The objective of ILAP is framed within the principles of the Australian Government’s strategic access to justice framework and also the National Partnership Agreement on Legal Assistance Services (NPA). The access to justice principles are: accessibility, appropriateness, equity, efficiency and effectiveness. Under the access to justice framework, Indigenous people are generally recognised as a disadvantaged group requiring specifically targeted or specialised services.24 As a result, cultural appropriateness of services is a relevant consideration for accessibility, along with physical distribution of service outlets in relation to the target population.

2.4 The objective of the NPA is to achieve a ‘national system of legal assistance that is integrated, efficient and cost-effective, and focused on providing services for disadvantaged Australians in accordance with the access to justice principles of accessibility, appropriateness, equity, efficiency and effectiveness’.25 While ILAP is not directly funded through the NPA, it is expected to contribute, along with three other types of legal assistance services,26 to the NPA’s objective. The NPA does not include specific performance requirements or deliverables for ILAP, but at a broad level there is a close alignment between the objectives of ILAP and the NPA, and the effective operation of ILAP could be reasonably expected to contribute to the broader national objectives. The NPA expires on 1 July 2015 (having been extended by one year from the original expiry). As noted in paragraph 1.19, from July 2015, a new national strategic framework for all Australian Government funded legal assistance services is expected to be in place which will provide shared national objectives and outcomes. AGD advised that the objectives of future ILAP funding agreements will reflect the intention of the national strategic framework, as agreed between the Australian Government, states and territories.

2.5 ILAP’s objective clearly indicates its nature as an ongoing service and the nature of its target group. However, the key concepts of accessibility, equity and effectiveness have not been defined by AGD at an operational level in either the providers’ funding agreements or the program guidelines. The high level principles act as a framework within which service providers operate, but do not serve to guide the priorities of service providers or to prioritise the collection of data to assess and report on the performance of providers individually or ILAP as a program.

2.6 The communication to the Parliament of priorities and the results expected from public funding is an important consideration for Australian Government entities and occurs through the publication of Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS).27 In the Attorney-General’s PBS, ILAP is part of the Indigenous Law and Justice (ILJ) program. Until September 2013, AGD administered several activities under the ILJ program, however, these other programs were subsequently transferred to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C). Accordingly, in 2014–15 ILAP comprised 99 per cent of the funding for the ILJ program.28

2.7 The ILJ program is one of eight programs intended to contribute to the broader outcome of a ‘just and secure society through the maintenance and improvement of Australia’s law and justice framework and its national security and emergency management system’.29 AGD has adopted generic objectives for all eight programs with the intention that their objectives will contribute to:

- protecting and promoting the rule of law; and

- building a safe, secure and resilient Australia.30

2.8 This generic approach provides limited insight into the specific results the Australian Government is seeking to achieve through the ILJ program, although the provision of services to support access to justice is identified as the main deliverable for the ILJ program. The key performance indicators (KPI) established for the ILJ to assess performance of the program are ‘improved access to justice for Indigenous people’ and ‘effective administration of the access to justice programmes for Indigenous people’.31

2.9 There are two aspects to the KPIs which could be improved. Firstly, no baseline information has been established to assess whether any improvements have occurred (discussed further in chapter 4). Secondly, the qualitative indicator does not fully align with the main activity funded through the program. While ILAP contributes to the provision of access to justice, its objectives reflect that it focuses on the ongoing provision of a demand-driven service to eligible clients, rather than on change-focussed interventions designed to improve access.

2.10 AGD advised that the indicators were not amended when other ILJ programs were transferred to PM&C in 2013 and that those other programs were designed to improve access. AGD further advised that, in the future, ILAP will be funded under the Justice Services Program, which will more closely reflect the objectives of ILAP.32

Program funding allocations and distribution

2.11 As noted in paragraph 1.10, there are eight ILAP service providers across Australia generally covering each state jurisdiction, although there are two providers serving the Northern Territory and a single provider operating across New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). As at December 2014, there were 80 service provider outlets located in metropolitan, regional, remote and very remote areas, supplemented by outreach services. In 2012–13 88 per cent of outlets were located in regional or remote areas.

2.12 The funding agreements between AGD and each provider do not include details on the numbers of outlets or their locations. While AGD is kept informed of office locations and resource allocations, AGD does not play an ongoing role in assessing demand within or between jurisdictions, or advising where offices should be located. Service providers are considered to be best placed to determine the locations and numbers of outlets and although AGD endorses these as proposed by the provider, no adjustments to funding are made when a provider chooses to close or move an outlet. Due to difficulties in attracting staff and increasing operating costs, some service providers have been forced to close some outlets. The ANAO was advised that during 2011 the Western Australian provider closed three offices (reducing the number of offices from 18 to 15) while the Queensland service has since closed six offices (reducing the number of offices from 27 to 21).

2.13 The numbers of outlets maintained by providers as at September 2014 are shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Provider outlets by jurisdiction, as at September 2014

|

Organisation |

State |

No. of offices |

Indigenous population served |

Indigenous population as a % of total population |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (QLD) |

QLD |

21 |

188 954 |

4.2% |

|

Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service |

NT |

2 |

68 850 |

29.8% |

|

North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency |

NT |

3 |

||

|

Aboriginal Legal Services of Western Australia |

WA |

15 |

88 270 |

3.8% |

|

Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement |

SA |

5 |

37 408 |

2.3% |

|

Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre |

TAS |

3 |

24 165 |

4.7% |

|

Victorian Aboriginal Legal Services |

VIC |

8 |

47 333 |

0.9% |

|

Aboriginal Legal Services |

NSW |

23 |

208 476 |

2.5% |

|

ACT |

6 160 |

1.7% |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011; and ANAO analysis of provider information.

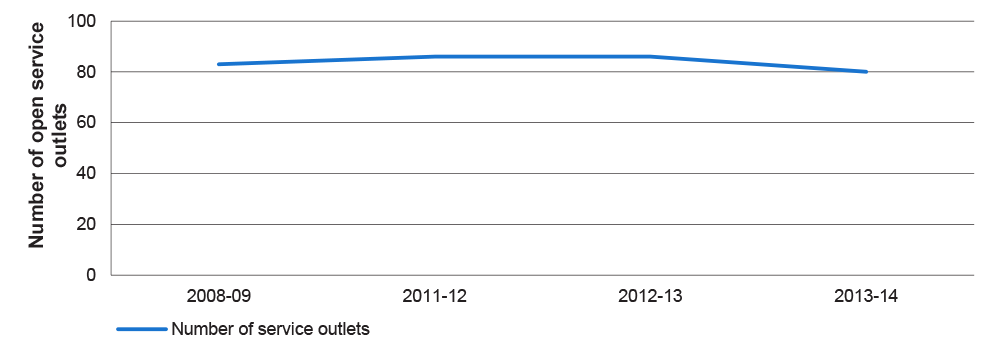

2.14 The trend in the number of outlets since 2008 is shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Number of provider outlets

Source: ANAO analysis

2.15 In late 2013, the Government announced a reduction of $43.1 million over four years across all Indigenous and non-Indigenous legal assistance programs. Of the $43.1 million reduction in funding, $13.4 million of funding was removed from ILAP policy reform and advocacy activities over four years. Even though these reductions were intended by the Australian Government to be confined to policy activities rather than front line services, during interviews with the ANAO, service providers felt that the planned $13.4 million funding reduction would significantly affect their ability to deliver services and force further office closures.

Assessing and servicing communities with greatest need

2.16 The ILAP program guidelines note that a priority for ILAP is to ‘invest in an efficient, effective and ethical manner in Australian Indigenous communities with the highest need.’33 Although this is a stated priority, it has not been given practical effect by AGD, which has adopted only a broad definition of Indigenous community and equates the community to the (mainly) jurisdictional boundaries of service provider areas.

2.17 Legal assistance services, by their nature, are targeted at disadvantaged clients and Indigenous people have been identified generally as a disadvantaged group.34 Studies undertaken on Indigenous offending have found that a relationship exists between socioeconomic disadvantage and contact with the justice system.35 However, not all communities are the same and significant differences in conditions can be experienced, for example, between urban areas and very remote areas. Until June 2014, when the Review of the National Partnership Agreement (NPA) on Legal Assistance Services report was released, no analysis or assessment had been undertaken by AGD to identify specific Indigenous communities of highest need. Further, AGD advised the ANAO that the department does not undertake work to determine areas of highest need as it considers that service providers are best placed to determine this.

2.18 The ANAO analysed data relating to relative disadvantage collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in the 2011 census to assess the alignment between disadvantaged areas and the locations of service provider outlets. Disadvantaged communities are classified by the ABS based on the relevant Local Government Area (LGA). The most disadvantaged LGAs with a high proportion of Indigenous residence, (Indigenous population greater than 50 per cent), are presented in Table 2.2. A full list of the most disadvantaged LGAs by state and Indigenous population is provided in Appendix 2.

Table 2.2: Number and location of most disadvantaged LGAs

|

State |

No. of disadvantaged LGAs |

Total Indigenous population of disadvantaged LGAs |

|

Northern Territory |

9 |

44 419 |

|

Queensland |

17 |

24 581 |

|

Western Australia |

5 |

9 952 |

|

South Australia |

2 |

2 438 |

|

New South Wales |

1 |

1 253 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011, Canberra.

Note: The Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and Tasmania do not have any disadvantaged LGAs with an Indigenous population of greater than 50 per cent.

2.19 There are significant variations across Australia in the distribution of disadvantaged Indigenous populations. As demonstrated in Figure 2.2, the most disadvantaged LGAs are located predominantly in remote and very remote areas of Australia, mostly in the north and west of the continent. There are relatively few service provider outlets located within these areas. The Northern Territory has the greatest number of Indigenous residents living in highly disadvantaged areas with a total of 44 419 people.36 This comprises over 64 per cent of the Northern Territory’s total Indigenous population yet is serviced by only five outlets. Highly disadvantaged areas with high Indigenous populations in South Australia have no outlets, relying entirely on outreach services. In contrast, the ACT, Victoria and Tasmania have much smaller Indigenous populations and do not have any LGAs where more than 50 per cent of the population is Indigenous. However, when considered against the general distribution of disadvantaged areas (and not considering the levels of Indigenous population), in most cases ILAP outlets are located in areas of each state that are relatively more disadvantaged than other areas.37

Figure 2.2: Disadvantaged Local Government Areas where over 50 per cent of the population is Indigenous

Source: ANAO.

Note: Map not to scale.

2.20 As noted in paragraph 2.17, under the Australian Government’s National Indigenous Law and Justice framework, Indigenous people are generally considered a disadvantaged population in relation to legal services. On this basis, it would be expected that service delivery patterns generally follow population patterns. The number of services delivered by ILAP providers in metropolitan, regional and remote areas, compared to the proportion of Indigenous people living in those areas, is shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Indigenous population compared to the proportion of legal services delivered

|

Area |

Indigenous population |

Proportion of services delivered |

|

Metropolitan |

34.8 % |

30.9 % |

|

Regional |

43.8 % |

41.6 % |

|

Remote |

21.3 % |

26.9 % |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: Due to the rounding of figures, totals may not add up to 100 per cent.

2.21 As outlined in Table 2.3, the proportion of services delivered is generally aligned with the Indigenous population located in each of the geographic areas. However, while the number of Indigenous people living in remote areas is only 21.3 per cent, almost 27 per cent of services are delivered to those people, indicating high demand and also that few other legal assistance service options are likely to exist to service remote Indigenous communities. By contrast, the share of services relative to population is lower for urban areas with 71.1 per cent of matters delivered in metropolitan and regional areas, where 78.6 per cent of Indigenous people are located. Service providers and stakeholders further informed ANAO that some very remote communities do not have any access to legal services. As a consequence, while Indigenous people residing in remote communities are still required to attend court for sentencing, many do not have access to legal representation which may result in higher imprisonment rates and associated adverse outcomes.

Types of legal services

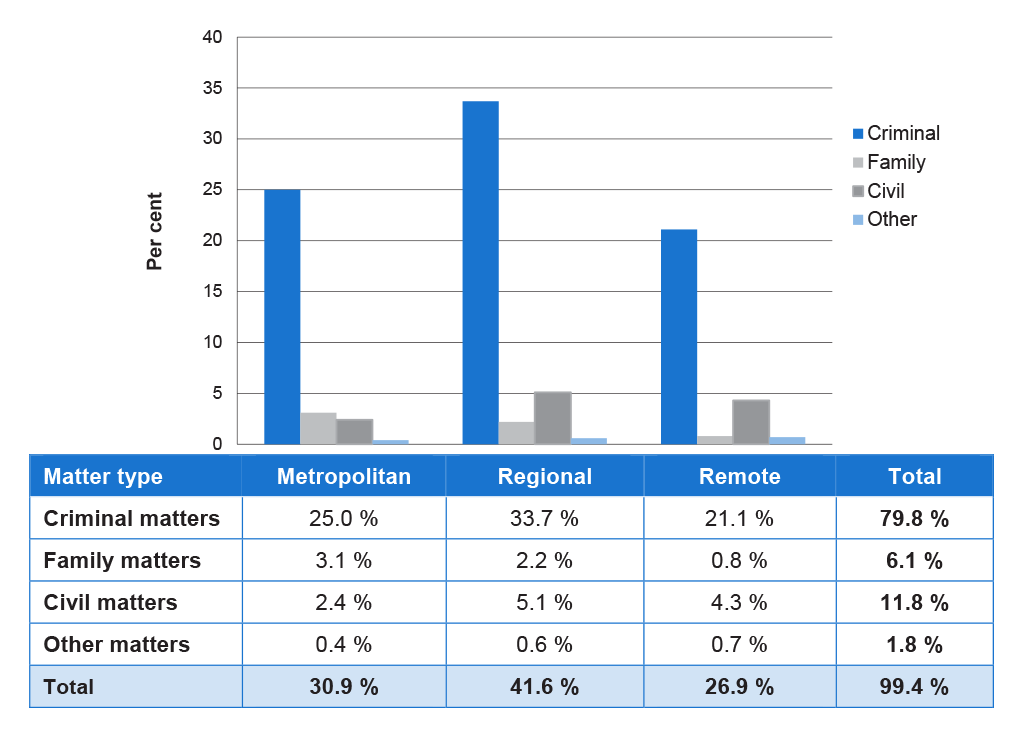

2.22 In response to the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC), ILAP has over time tended to focus primarily on providing criminal law services to Indigenous people. For many reasons, including long-standing disadvantage and ongoing discrimination, Indigenous people experience much higher rates of adverse contact with the justice system and are imprisoned at significantly higher rates than other Australians. In 2013, the ABS reported that Indigenous prisoners comprised just over one quarter (27 per cent) of Australia’s total prisoner population. In this context, 80 per cent of all legal services delivered by ILAP providers relate to criminal law. The comparison between the amount of criminal case work and that undertaken in the family and civil law areas is shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: ILAP 2013–14 case work services by law type—metropolitan, regional and remote areas (percentage)

Source: ANAO, based on AGD data.

Note: Due to the rounding of figures, totals may not add up to 100 per cent.

Availability of family and civil legal services

2.23 Although the focus of ILAP is on the provision of criminal legal services, the objective of the program: to ‘deliver legal assistance and related services to Indigenous Australians so that they can fully exercise their rights as Australian citizens’ has a broader focus than criminal law alone. Of the eight ILAP service providers interviewed by ANAO, seven advised that there was a significant unmet need for family and civil legal services. This observation is also supported by the views expressed by related industry stakeholders interviewed by the ANAO.38 Service providers further advised that unmet demand is particularly acute in remote or very remote areas, with high Indigenous populations. While providers are aware of this unmet demand, they advised that they are unable to increase the family and civil services delivered because of funding constraints associated with ILAP’s focus on criminal law.

2.24 Service providers particularly expressed concern about the increasing incidence of children being removed from their homes while parents were, in many cases, unaware of their legal rights or unable to obtain legal assistance. One industry stakeholder described the lack of family legal services available to help Indigenous families and children in one jurisdiction as ‘dire and acute’. In Queensland, service provider satellite outlets39, servicing many of the most disadvantaged LGAs, are resourced to provide criminal legal services only, which results in those communities having no immediate access to any family or civil legal services.

2.25 In 2011, the James Cook University commenced a national research study of the civil and family law needs of Indigenous people called the the Indigenous Legal Needs Project (the project). The project aims to identify and analyse the legal needs of Indigenous communities in non-criminal legal areas. As of June 2014, the project had delivered two reports: the NT Report (November 2012) and the Victorian Report (November 2013). Both reports identified significant gaps in Indigenous access to justice with respect to civil and family law. The reports specify housing and tenancy as the major areas of unmet demand with other priority areas being: child protection; discrimination; neighbourhood issues; social security; victim’s compensation; wills; credit and debt; and consumer issues.40 Similar observations have also been made by the Productivity Commission, which found that unmet need remains widespread, particularly in more remote locations41 and the Review of the National Partnership Agreement on Legal Assistance Services which found that the amount of legal assistance available to those in remote communities is not adequate to meet residents’ needs.42

Program funding allocations

2.26 In most grant programs service providers request an amount of funding required to deliver specified outcomes, which is then subject to negotiation with the funding department. This differs in ILAP, where funding is determined by the department using a Funding Allocation Model, which takes into account conditions particular to each service area.

Table 2.4: Funding allocations to service providers, 2012–15

|

Indigenous Legal Service Provider |

State |

$ Millions |

|||

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

Total |

||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services Queensland Ltd. |

QLD |

$ 15.4 |

$ 17.2 |

$ 17.4 |

$ 50.0 |

|

Aboriginal Legal Services NSW/ACT Ltd. |

NSW |

$ 16.3 |

$ 18.3 |

$ 18.5 |

$ 53.1 |

|

Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service Cooperative Ltd. |

VIC |

$ 3.7 |

$ 4.2 |

$ 4.3 |

$ 12.2 |

|

Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Inc. |

TAS |

$ 1.9 |

$ 2.1 |

$ 2.1 |

$ 6.1 |

|

Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia Inc. |

WA |

$ 11.8 |

$ 13.2 |

$ 13.4 |

$ 38.4 |

|

Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service Inc. |

NT (South) |

$ 4.1 |

$ 4.6 |

$ 4.7 |

$ 13.4 |

|

North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd. |

NT (North) |

$ 7.1 |

$ 8.0 |

$ 8.1 |

$ 23.2 |

|

Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement Inc. |

SA |

$ 4.3 |

$ 4.8 |

$ 4.9 |

$ 14.0 |

|

Totals |

$ 64.6 |

$ 72.3 |

$ 73.4 |

$ 210.3 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of AGD information. Figures are rounded.

Funding Allocation Model

2.27 In order to allocate funds consistently and take account of circumstances specific to the different service provider areas, AGD has developed a mechanism to allocate funding—the Funding Allocation Model (FAM). AGD commissioned the development of the FAM in 2006 with the completed mechanism being first implemented in 2008.43 The FAM has been updated twice since then, once in 2009 and again in 2013 to incorporate up-to-date census data into the mechanism. As of December 2014, AGD was working toward the development of a new FAM to support proposed reforms to Indigenous legal assistance funding arrangements expected to be implemented from 1 July 2015.

Application of the FAM

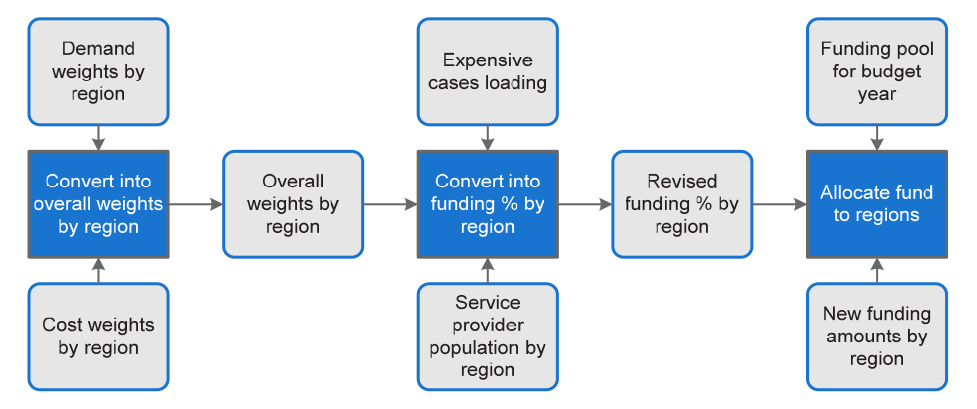

2.28 The FAM applies a weighting to take into account a range of mainly demographic factors—particularly the age and gender distribution of Indigenous communities. These factors attract the highest weightings in the FAM. The FAM also includes ‘special purpose’ weightings for residents removed from their families as children, and for prison locations. The FAM also has the capacity to incorporate additional weighting factors as empirical data becomes available to accurately support them. The process involved in allocating funds using the FAM is shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: Process used to determine funding allocations

Source: ANAO.

2.29 The use of the applied weightings results in the calculation of a per-capita amount specific to each jurisdiction. These amounts are then multiplied by the Indigenous population of a jurisdiction to arrive at the final funding allocation. Figure 2.5 demonstrates the resources allocated to each of the eight service providers compared to their respective Indigenous populations.

Figure 2.5: Funding allocation compared to Indigenous population

Source: ANAO, based on AGD updated funding allocation mechanism data.

Integrity of the FAM

2.30 To consider the integrity of the FAM, the ANAO conducted testing on the 2013 model. The FAM has been built using a Microsoft Excel workbook which is made up of 15 separate sheets. Analysis of the FAM found that while the spreadsheets did allocate funding in accordance with the intended methodology, some weaknesses were identified, as outlined in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Identified FAM weaknesses

|

Weakness |

Details |

|

Cell references are inaccurate and contain incomplete data ranges |

Some formulas were not maintained correctly. Data ranges used to develop the formulas were incomplete with some of the data groups being left out, while other formulas had been lost and replaced with hardcoded numbers. |

|

Formula logic and design |

Updating of one spreadsheet has resulted in one column attempting to process and merge two factors, when only designed to process and calculate one factor. This has resulted in calculation difficulties and an approach that is inconsistent with other factors contained within the spreadsheets, increasing the complexity of the mechanism and reducing its robustness. |

|

Lack of documentation |

A lack of system documentation was available on the FAM’s design and use. While a ‘user guide’ was available for one of the sheets, it provided very limited information and was not applicable to the remaining spreadsheets. The lack of design and data flow documentation reduces the transparency of the model and increases the difficulty of conducting accurate maintenance and modification to the spreadsheets. |

|

Design vulnerabilities |

There is little evidence of version control, change history or security and protection features incorporated into the spreadsheets. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the FAM.

2.31 While none of the issues identified in the current FAM were found to have a substantial impact on its results, they do highlight common areas of vulnerability that should be addressed by AGD when revising the mechanism. AGD advised that it is revising the FAM as a part of reforms to legal assistance services proposed to commence from 1 July 2015. Issues under consideration include Indigenous population levels, socioeconomic status and geographical remoteness. The revised funding model is to inform the allocation of ILAP funding from 1 July 2015.

Availability of funding

2.32 Service providers informed the ANAO that the funding received under ILAP is currently inadequate, in their view, to allow service providers to meet demand, or to provide the level of services needed—particularly in remote and very remote areas. The level of funding currently received was considered to have not kept pace with rising delivery costs, nor to reflect policy and legislative changes that increase demand, or the cost of delivery over the funding period. Over recent years some state and territory governments have introduced new legislation aimed at improving behaviours relating to child welfare, anti-social behaviour, and housing, among others. Such legislation is often designed around reducing tolerance to, and taking a tougher stance on, crime and anti-social behaviour. The implementation of these policies often has an impact on Indigenous Australians, significantly increasing the number of people who require legal assistance.

ILAP risk management

2.33 Actively managing risks is an important part of program administration, enabling managers to identify and treat potential threats to program outcomes. Risk management involves the identification, analysis, treatment and allocations of risks, both in relation to the overall design of a program and, where relevant, administration of individual funding agreements. The ANAO examined AGD’s approach to managing risk at both these levels to understand the extent to which ILAP risks have been identified, and how they are incorporated into the ongoing program implementation and decision-making.

Program level risk management

2.34 To manage identified risks well, regular monitoring and treatment of risks should occur throughout the entire funding period. AGD developed the ILAP program risk assessment at the beginning of the funding term in 2011. However, no evidence was available to indicate that the risk assessment had been actively implemented or reviewed since that time, or how it has influenced decision making. From analysis of the risks listed in the ILAP risk assessment, the ANAO observed that over 50 per cent of the risks identified had been realised, yet AGD had not applied remedial action to address the consequences. Risks realised related primarily to:

- changes in state and territory policy directions resulting in increased demand for legal services;

- available funding not meeting demand;

- high demand for services impacting adversely on the quality of services delivered by ILAP service providers;

- performance data submitted by ILAP service providers being inconsistent or inaccurate; and

- change in government policy which could impact on resourcing available to administer the program.

2.35 AGD’s current approach to program level risk management is reactive and, for the most part, has seen AGD absorb risk consequences as they occur. While the ANAO recognises that some risks identified in the ILAP risk assessment are beyond the control of AGD44, others were foreseeable and a more active approach could improve AGD’s ability to deal with and remedy risks as they are realised, reducing the impact of program risk on AGD, Indigenous clients and service providers.

Project level risk management

2.36 AGD undertakes risk assessments for each service provider and adjusts its reporting requirements and payment frequency according to the level of assessed risk. Low risk providers receive funding on a six-monthly basis, with medium risk providers paid quarterly and high risk providers paid monthly. This framework is the main tool through which AGD gives effect to its risk management approach to ILAP at the project level. Where risks are assessed as higher, the service provider’s reporting requirements increase, and the provider receives less autonomy with respect to its forward funding horizon. While such an approach could provide a basis for effective project level risk management, as outlined below, AGD has not established systems to support its consistent application, thus undermining its usefulness.

2.37 AGD uses a risk assessment spreadsheet to assess and allocate risk ratings. The risk assessment spreadsheet is partly aligned with the funding agreement reporting requirements and partly reflects other information available to AGD. Overall the spreadsheet is limited to guiding an assessment of whether a service provider has fulfilled its administrative and reporting obligations. The accuracy and quality of the information contained within the reports submitted is not verified by AGD. Consequently, the approach provides only a limited degree of assurance to AGD, reflecting a reporting compliance checklist, rather than providing the basis for managing risks.

ANAO review of risk assessments completed by AGD—January to June 2014

2.38 The ANAO examined each risk assessment undertaken by AGD for the eight service providers for the period January to June 2014. For these assessments, AGD had used different versions of the risk assessment tool, leading to inconsistent approaches to calculating risks for providers, and the instructions for calculating risks were not accurate or aligned to the data included in the spreadsheet. Generally, AGD’s risk assessments did not identify risks specific to each provider; did not include analysis, evaluation or rating of risks; or provide a framework to treat risks as they arise. Of the eight assessments examined, none of the providers had been assigned a rating using the spreadsheet. In two cases the risk ratings assigned by the risk ratings template differed to the formal risk rating that AGD assigned to each of the providers, as shown in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6: Comparison of risk ratings given to providers by AGD

|

Provider |

AGD risk rating* |

Formal risk rating applied by AGD |

|

Western Australia |

Low |

Low |

|

Northern Territory (North) |

Low |

Low |

|

Northern Territory (South) |

Low |

Medium |

|

South Australia |

Low |

Low |

|

New South Wales |

Low |

Low |

|

Queensland |

Low |

Low |

|

Tasmania |

Low |

Medium |

|

Victoria |

Low |

Low |

Source: ANAO analysis of service provider risk assessment January to June 2014.

Note: * This risk rating was calculated by ANAO using AGD’s risk assessment sheets.

2.39 AGD informed the ANAO that when the department considers it necessary to monitor a particular provider more closely, other indicators can be used from time to time to force a risk rating higher, thus triggering more frequent reporting and payment cycles under the funding agreement.45 Overall, the assignment of risk ratings largely occurs reactively and in response to problems as they arise, rather than as a result of a forward-looking and consistently applied project risk management framework. AGD acknowledged the limitations of the current risk assessment tool and advised that the current risk framework, including the spreadsheet, was being reviewed to ensure a more rigorous approach, with a greater focus on performance and not just compliance.

Conclusion

2.40 An important factor in the successful delivery of programs is establishing the objectives to be achieved, funding appropriate activities to achieve those objectives, and managing risks to the achievement of the objectives. ILAP objectives are clearly stated in the program guidelines and focus on the provision of legal assistance services that are accessible, culturally appropriate, equitable, efficient and effective. The program’s funding strategy of using Indigenous organisations to provide these services, using local outlets, is reasonably well aligned with the program’s objectives, and service usage is generally consistent with the distribution of the Indigenous population. Providing services in regional and remote areas to disadvantaged communities has inherent challenges and is costly, and the closure during 2014 of a number of regional outlets is likely to have affected access in those areas.

2.41 AGD is kept informed of office locations and resource allocations made by service providers but does not play an ongoing role in assessing demand within or between jurisdictions, or advising where offices should be located. Service providers are considered to be best placed to determine the locations and numbers of outlets and although AGD endorses these as proposed by the provider, no adjustments to funding are made when a provider chooses to close or move an outlet. The priority of ILAP is to deliver services to Indigenous communities with the highest need. However, to date, AGD has not undertaken any significant work to determine which areas of the community are considered to be ‘high need’ or which communities are experiencing access barriers. In this respect, funding allocations at a broad level are derived from assessing a combination of population, risk and cost factors and, while these generally reflect broader population distribution, the relationship to levels of disadvantage at the local government area was less consistent.

2.42 Under AGD’s management framework, low risk providers receive funding on a six-monthly basis, with medium risk providers paid quarterly and high risk providers paid monthly. This framework is the main tool through which AGD gives effect to its risk management approach to ILAP at the project level. While such an approach could provide a basis for effective project level risk management AGD has not established systems to support its consistent application, thus undermining its usefulness.

3. Managing Service Delivery

This chapter examines the design and management of the service delivery arrangements the Attorney-General’s Department has in place to administer funding for the Indigenous Legal Assistance Programme.

Introduction

3.1 Grant funding is a common means for governments to deliver services and pursue policy objectives. It is important that approved grants are administered in a way that promotes cost-effective and accountable achievement of the objectives. In this respect, the grant agreement (or funding agreement) provides a key framework for the administration of grants and the mechanism for identifying the outcomes expected to result from the grant, the terms and conditions to be complied with, reporting and requirements and the basis for payments. Effective grants administration also encompasses the implementation of an appropriate monitoring regime to ensure that grant recipients are meeting agreed conditions and that performance meets expectations. The ANAO examined the grant management arrangements put in place by AGD for ILAP.

Managing service delivery

3.2 AGD has developed and implemented arrangements to manage and monitor the delivery of Indigenous legal services by the eight legal service provider organisations. The primary tools enabling AGD to manage and monitor the service delivery are the ILAP Program Guidelines 2014 (ILAP guidelines) and a funding agreement with each of the service providers.

Program guidelines and funding agreements

3.3 Under the then Commonwealth Grants Guidelines (CGGs) ‘Agencies must develop grant guidelines for new grant programs, and make them publicly available (including on agency websites) where eligible persons and/or entities are able to apply for a grant under a program’.46 The ILAP guidelines, originally released in 2011, were developed in consultation with the then Department of Finance and Deregulation and approved by the then Attorney-General. Prior to their approval, AGD sought further advice from the Australian Government Solicitor that the ILAP guidelines and funding agreements complied with the CGGs.

3.4 The guidelines provide stakeholders with general information on ILAP including: purpose, objectives, priorities, structure, eligibility, performance measures and compliance, the application process and complaints mechanisms. In July 2014, updated ILAP guidelines were released covering the 2014–15 extension of the funding agreement.47 Under a typical grant program, guidelines would play an important role during funding rounds by communicating the program objectives and requirements to potential stakeholders and eligible organisations. However, as AGD currently administers the program using a direct sourcing arrangement—rather than conducting funding rounds, the ILAP guidelines do not play such an integral role in communicating the details of the program, and facilitating access to grants, as they would in other grants programs.

Funding Agreements

3.5 A funding agreement should clearly set out the services to be delivered and the expected level of quality of those services. The funding agreements currently in place for ILAP do not show a strong performance orientation or specifically identify objectives or expected targets. General statements are included in the agreements that providers are to deliver legal assistance services that are of high quality, culturally sensitive, equitable and accessible although these important features are not defined in the agreement, which affects the ability of the service provider and AGD to objectively assess whether services in fact meet those expectations. Further, the stated approach to performance assessment is simply to measure performance against the service providers’ compliance with the terms and conditions of the funding agreement rather than against the achievement of any specific objectives. AGD advised that as a part of the proposed future arrangements for legal assistance, all current ILAP documentation including funding agreements, program guidelines and policy documents, such as the Service Delivery Directions are being reviewed.

3.6 The types of legal assistance services to be delivered are specified in the funding agreements but there is no information on the expected numbers of services to be provided, the number of outlets or the location of service outlets. Standards for the delivery of these services are also not included in the agreements. These matters are covered to some extent in other documents such as the Service Plan that is prepared annually by each service provider. Some guidance is also given in supporting documents including the Service Delivery Directions and Service Standards. Overall, the funding agreements are largely compliance focussed and give limited information on expected performance. In the absence of such information, AGD is not well positioned to objectively assess the effectiveness of providers in relation to the program’s objective.

Operational guidance

3.7 AGD has developed a suite of operational guidance documents which include:

- Service Delivery Directions;

- Service Standards;

- Reporting Requirements; and

- Data Protocol.

Service Delivery Directions

3.8 The Service Delivery Directions (SDDs) outline the activities that providers are required to comply with, including:

- areas of practice—types of legal assistance and related services able to be provided to clients;

- eligibility—who is eligible to receive assistance, including how the means test should be applied and priority clients; and

- how providers should co-operate with other legal service providers.

3.9 Of the eight service providers interviewed by the ANAO, all advised that the SDDs are flexible enough to generally allow the delivery of services as necessary. However, minor services relating to wills, funerals, and personal tax or billing issues were not included in the SDDs, but were matters that clients often sought assistance with.