Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Enforceable Undertakings

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s administration of enforceable undertakings.

Summary

Introduction

1. Australia’s financial system plays an essential role in supporting the economic prosperity of Australians by, among other things, providing consumers and businesses with banking, investment, superannuation and insurance services. Australia’s financial system has grown strongly in recent years, particularly following the introduction of compulsory superannuation in 1992. Financial assets have grown from around two years’ worth of Australia’s nominal gross domestic product1 in 1997 to more than three times nominal gross domestic product in 2013. At December 2014, financial institutions in Australia controlled assets of around $6 trillion.2

2. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) is Australia’s corporate, financial markets, financial services and consumer credit regulator. It seeks to ensure the markets it regulates are fair and transparent, supported by confident and informed investors and consumers. It has wide-ranging responsibilities that include regulation of around 2.2 million companies and 5000 Australian financial services licensees.3 Together with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority and the Reserve Bank of Australia, ASIC plays a major role in regulating Australia’s financial system.

3. One of ASIC’s most important responsibilities is to ensure that regulated entities4 comply with their legal obligations, including obligations under the Corporations Act 2001. ASIC has developed a range of strategies aimed at encouraging voluntary compliance and addressing non-compliance. These strategies include:

- educating consumers and investors to make informed and appropriate choices when dealing with money and financial products and services;

- providing guidance to regulated entities on how to comply with their obligations; and

- communicating the actions that ASIC takes to inform regulated entities about the standards that it expects and the consequences of failing to meet those standards.5

4. Where there is non-compliance by a regulated entity, ASIC can take enforcement action to deal with and deter the misconduct. This may involve conducting an investigation and: taking criminal action (such as seeking imprisonment); commencing civil proceedings (including seeking civil penalty orders); taking administrative action (such as banning orders and imposing licence conditions); or accepting a negotiated outcome (including an enforceable undertaking, known as an EU). ASIC has adopted a graduated approach to enforcement, with the more severe and less frequently used sanctions being employed for serious misconduct, while responses such as EUs are used for less serious misconduct.

5. An EU is a written undertaking given to ASIC by a company or individual that it will operate in a certain way. EUs can achieve a broad range of outcomes, such as requiring an entity to compensate consumers, improve its compliance processes, cease providing services for a period or indefinitely, or undertake specific education programs. In contrast to other regulatory alternatives, an EU can be a relatively quick remedy where: results are more certain than the outcomes of court proceedings; it has the potential to change the compliance culture of an organisation; and it may achieve an outcome that is comparable to, or better than, that obtained in court. An EU is not an alternative to commencing criminal action, and is generally not used in cases involving deliberate misconduct, fraud, or conduct involving a high level of recklessness.

6. An EU generally arises where ASIC becomes aware of potential misconduct by an entity. Discussions may then commence between ASIC and the entity about how to resolve ASIC’s concerns. If ASIC considers that an EU would provide an effective regulatory outcome in response to the misconduct, it may enter into negotiations with, and accept an EU from, the entity.

7. Between 1 January 2012 and 30 June 2014, ASIC entered into 53 EUs.6 The entities involved included large banks and other financial institutions, large public companies, providers of credit, and individual auditors and liquidators. The EUs related to a wide variety of conduct, including:

- misleading or deceptive conduct by financial institutions;

- failures by company auditors and liquidators to properly carry out their duties and functions;

- poor advice provided by financial advisers; and

- the failure of Australian financial services licensees to monitor and supervise the financial services provided by their representatives.

8. Following acceptance of an EU, ASIC monitors compliance with the undertaking by the entity or individual (promisor), often with input from an independent expert. If the promisor does not comply with the EU, ASIC may enforce the undertaking, generally in the Federal Court of Australia or a State Supreme Court.

9. ASIC has five Commissioners, including the Chairman, Deputy Chairman and three members (the Commission). Reporting to the Commission are 12 stakeholder teams and three enforcement teams organised around the industry segments regulated by ASIC. Each of the teams is headed by one or more Senior Executive Leaders who have responsibility for most regulatory activities undertaken by ASIC, including the decision to accept an EU (except for a major matter which must be approved by ASIC’s Enforcement Committee or the Commission).

Parliamentary interest

10. In June 2014, the Senate Economics References Committee released a report on its inquiry into the performance of ASIC.7 In this report, the Committee recognised the good work that ASIC has done in a challenging environment, but raised a number of concerns about the performance of ASIC, including in relation to its use of EUs. The Committee’s report contained 61 recommendations aimed at enabling ASIC to fulfil its responsibilities more effectively. The report also raised concerns about ASIC’s enforcement decisions, and particularly its use of EUs. In summary, issues raised in submissions and highlighted by the Committee included: the use of EUs as a remedy for misconduct by large entities; the strength of terms included in EUs; the clarity of EUs in describing the alleged misconduct; and the transparency of the monitoring of compliance with EUs. The report included a recommendation that the Auditor-General undertake a performance audit of ASIC’s use of EUs. The Auditor-General agreed to this request.

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s administration of enforceable undertakings.

12. To form a conclusion against this objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) adopted the following high level criteria:

- management arrangements are in place that support the effective, consistent and transparent administration of EUs;

- offers of an EU are administered consistently, transparently and in accordance with ASIC’s policies and procedures; and

- EUs accepted by ASIC are monitored to ensure compliance with those undertakings, action is undertaken where non-compliance is identified and the effectiveness of EUs as a regulatory tool is assessed.

Overall conclusion

13. As one of ASIC’s suite of regulatory responses, enforceable undertakings (EUs) have a valuable role in ASIC’s overall enforcement approach. EUs are particularly useful in addressing less serious misconduct where the promisor is co-operative. A potential benefit of EUs is in driving changes in a promisor’s compliance culture and systems, whereas an administrative penalty (or even a civil sanction) may not lead to behavioural change. Since their introduction in 1998, ASIC has accepted an average of 24 EUs per year, and from January 2012 to June 2014, 53 of ASIC’s 1711 enforcement actions (three per cent) were EUs.

14. In general, ASIC has effectively administered the EUs it has negotiated and accepted. It has sound processes for each major step of the EU process: accepting EUs as the most appropriate regulatory tool; including terms in the undertaking that appropriately address the misconduct; and monitoring adherence to those terms and addressing any identified non-compliance. However, there is considerable scope to improve the record keeping processes supporting EU decisions and compliance monitoring, as documentation was inconsistent, dispersed across multiple systems and not always readily available. In addition, ASIC does not measure or report on the effectiveness of EUs in achieving intended regulatory outcomes, including greater levels of voluntary compliance. Improved performance measurement and reporting would better inform key stakeholders, including Parliament, of the effectiveness of ASIC’s regulation.

15. In relation to entering into EUs, ASIC has accepted offers of EUs consistently, transparently and in accordance with its policies and procedures. For most EUs reviewed by the ANAO (83 per cent)8, there was sufficient documentation to demonstrate that accepting an EU would provide an effective regulatory outcome9 and no instances were identified where promisors were treated differently based on the size of their business.

16. ASIC also had a sound basis for including particular terms in each EU, with the terms generally aligning with the non-compliance at which the EU was directed. However, ASIC could ensure that EUs are clearer about the misconduct that was the subject of ASIC’s concerns. ASIC could also strengthen its capacity to assess compliance with, and the effectiveness of, EUs by more consistently including in the terms of an EU the requirement that the promisor report back to ASIC demonstrating their compliance with EU obligations. This information will better inform ASIC’s monitoring of the promisor’s compliance with the EU and, where necessary, its response to non-compliance.

17. Where the EU required an independent expert to assess the promisor’s compliance with EU obligations, ASIC was generally involved with the review process, and the reports provided by the expert were satisfactory. However, there were inconsistencies in ASIC’s approach to approving the appointment of experts and their terms of reference.10 In February 2015, ASIC released new public guidance that is expected to help improve processes relating to the appointment of independent experts.

18. The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving ASIC’s measurement and reporting of the effectiveness of EUs, and its documentation of key decisions relating to EUs.

Key findings by chapter

Managing Enforceable Undertakings (Chapter 2)

19. A key component of any regulatory regime is a sound compliance and enforcement approach. ASIC follows a structured process to identify and prioritise its strategic compliance risks. Once risks are identified, it has a well-established hierarchy of regulatory responses to non-compliance, including enforcement options. EUs have a clear place in ASIC’s approach, as a response to less serious misconduct, particularly as they can provide flexibility and have the capacity to drive cultural change in a promisor’s business.11

20. To support its decision-making in respect of EUs, ASIC has a range of public guidance (including regulatory guides and information sheets), and internal policies and procedures. ASIC also negotiates outcomes that are not EUs.12 However, the role of these is less clear, as there is no policy, definition or register for these other negotiated outcomes. To provide more certainty to regulated entities, ASIC should consider ways to provide greater clarity around the circumstances in which it accepts and enters into other negotiated outcomes.

21. ASIC’s organisational arrangements for EUs are appropriate. The stakeholder and enforcement teams have clear roles and responsibilities in relation to EUs.13 There are sound procedures for Senior Executive Leaders to provide oversight and direction, and to refer major matters for consideration by ASIC’s Enforcement Committee and where relevant, approval by the Commission. However, internal management reporting is currently limited to reporting on the progress of EU negotiations, and more recently, compliance with undertakings for some EUs. Improving reporting to include the consistency, timeliness and outcomes of EUs would better position senior management in oversighting EUs.

22. There is sufficient guidance, on-the-job training and support for ASIC officers involved in the EU process. However, there is scope for ASIC to consolidate the information relating to EUs to reduce duplication, improve accessibility and facilitate better internal and external oversight of the EU process.14

23. All regulators require a sound performance measurement and reporting framework, and an understanding of the costs of its regulatory activities. ASIC has five KPIs that relate to EUs. However it does not report externally against three of these KPIs, and only reports partially against two KPIs.15 The enhanced Commonwealth performance framework will come into effect on 1 July 2015, and provides the opportunity for ASIC to review its KPIs and develop appropriate performance measures, and to report on the extent to which EUs support ASIC in achieving regulatory outcomes. There would also be benefit in ASIC more systematically collecting information covering the costs of administering EUs, to help allocate its resources effectively and to ensure it is not placing an excessive burden on regulated entities.

Entering into Enforceable Undertakings (Chapter 3)

24. To help ensure that EUs are administered consistently and transparently, it is important that they are entered into in accordance with ASIC’s policies and procedures. ASIC’s internal guidance requires senior management involvement in all EUs, including approving the commencement of negotiations and providing final approval for the EU. For 85 per cent of EUs reviewed by the ANAO, senior management was appropriately involved throughout the process and, for 77 per cent of EUs, there was documented approval for the decision to negotiate an EU. However, the format and content of documentation (including approvals) varied substantially between cases and there is considerable scope to improve ASIC’s documentation to support a more consistent approach to the EU decision-making and approval process.

25. For 44 (83 per cent) of the 53 EUs reviewed, the documentation was sufficient to establish that the decision to accept an EU—on the basis that it would achieve an effective regulatory outcome—was defensible.16 In these cases, the ANAO was able to identify some comparative analysis outlining the benefits of accepting an EU over other regulatory options (such as court action). The most common justifications for entering into an EU included that the EU provided a superior outcome to consumers and investors and/or a more timely and cost effective way to deal with the misconduct. No instances were identified where promisors were treated differently based on the size of their business.

26. Generally, terms included in EUs provided a proportionate regulatory response to the non-compliance identified. The individual terms in the EU and the misconduct at which those terms were directed were also clearly aligned. However, ASIC does not assess the effectiveness of EUs (and terms in EUs) to enable it to have a firmer basis for requiring particular terms in EUs, or to provide assurance that EUs are having the desired regulatory outcome. In addition, to improve its capacity to monitor compliance with EUs (and to assess their effectiveness), ASIC could include reporting requirements in EUs requiring the promisor to provide proof of discharging their obligations. In line with the Senate Economics References Committee’s recommendation, there is also scope for ASIC to ensure that EUs are clearer about the misconduct that was the subject of ASIC’s concerns. This can be achieved by ASIC setting expectations about the required content of EUs through its policies, and through consistent actions in requiring future EUs to include a sufficiently clear statement about the alleged misconduct.

27. When EUs are being finalised, the Chief Legal Office is to provide quality control and assurance. However, while there was evidence of Chief Legal Office involvement for most EUs (91 per cent), an approval was documented in only 41 per cent of cases. Also, while senior executives ultimately sign all EUs, final approvals were only recorded (as required by ASIC guidance) in 53 per cent of cases. Accordingly, there would be merit in ASIC formalising the processes for obtaining approvals for EUs.

28. ASIC’s policy is that it will issue a media release for each EU and, at its discretion, may give advance notice about the media release to a promisor. While media releases were published for 52 of the 53 EUs reviewed, there was inconsistency in ASIC’s handling of requests from promisors for advance copies of media releases. In March 2015, ASIC advised that it will be introducing a new policy that media releases will generally be provided to all promisors that enter into an EU, 24 hours before publication.

Monitoring Compliance with Enforceable Undertakings (Chapter 4)

29. To assess whether EUs achieve intended regulatory outcomes (including greater compliance), it is important that ASIC monitors compliance by promisors with these undertakings.17 In this regard, ASIC’s monitoring of compliance with EUs was adequate for the significant majority of EUs reviewed (83 per cent). In accordance with its risk-based approach, monitoring was generally undertaken consistently, with ASIC having more extensive ongoing involvement with a promisor where the EU was complex or involved ongoing obligations. Where ASIC had information available suggesting non-compliance with an EU, it responded appropriately having regard to the circumstances of the matter.

30. To assist in monitoring a promisor’s compliance with an EU and/or relevant laws following acceptance of an EU, ASIC often requires the appointment of an independent expert to conduct independent reviews of the promisor’s business. However, there were inconsistencies in the process for appointing independent experts under an EU. Of the 30 EUs that required an independent expert to be appointed, 13 did not provide for ASIC to approve the expert

and/or their terms of reference. Further, even where there was a requirement for ASIC to approve the expert, the practices for this varied considerably between EUs, and there was no documented consideration of the appropriateness of an expert for one-third of cases where an approval had been given. In four of the 10 EUs reviewed (40 per cent) where there was documented consideration of the appropriateness of an independent expert, ASIC rejected the initial expert proposed by the promisor. ASIC has recently released new public guidance that requires promisors to obtain ASIC’s approval for the appointment of an expert and their terms of reference. It is expected that this will increase consistency over time.

31. In general, reports produced by independent experts addressed EU requirements, were sufficiently comprehensive and provided meaningful recommendations for promisors to improve their compliance with the legislation and/or the EU. The level of engagement by ASIC with the appointed independent expert reflected a risk-based approach, depending on the nature and complexity of the EU, and the misconduct at which the EU was directed. For 75 per cent of EUs where an independent expert had been appointed, there was evidence of ASIC assessing the reports provided by the expert and in 60 per cent of cases, there was evidence of direct communication by ASIC with the expert. However, while its engagement with experts was effective overall (particularly when a stakeholder team was responsible for monitoring compliance), ASIC should keep records of such engagement and ensure that roles and responsibilities for monitoring are clearly understood.

32. In its report, the Senate Economics References Committee recommended that ASIC consider ways of making the monitoring of ongoing compliance with EUs more transparent. In response, in August 2014 ASIC introduced draft guidance requiring, as a general position, the public reporting of outcomes of EUs (including the publication of summaries of independent expert reports). ASIC is currently entering into EUs consistent with this new policy and anticipates that by doing so, it will effectively address the Senate Economics References Committee’s recommendation. Nevertheless, there remains scope for ASIC to more systematically assess, and report publicly on, the effectiveness of each EU in achieving its desired regulatory outcomes.

Summary of entity response

33. ASIC provided the following summary comment to the audit report:

ASIC welcomes the ANAO audit report on ASIC’s administration of enforceable undertakings and considers it provides useful recommendations for improvements in practices. ASIC also welcomes the findings by the ANAO that enforceable undertakings have a significant role to play in ASIC’s enforcement approach, that in general, ASIC has effectively administered the enforceable undertakings it has negotiated and accepted, and that ASIC has accepted offers of enforceable undertakings consistently, transparently and in accordance with its policies and procedures. The findings that ASIC’s decisions and actions regarding enforceable undertakings are underpinned by a structured compliance and enforcement approach and that the ANAO did not identify any instances where promisers were treated differently based on the size of their business are also welcomed by ASIC.

ASIC agrees with the two recommendations made in the report, aimed at improving ASIC’s measurement and reporting of the effectiveness of enforceable undertakings, and at the documentation of key decisions relating to enforceable undertakings. ASIC confirms the recommendations will be implemented.

ASIC has been working towards the development of performance measures and reporting to comply with enhanced Commonwealth reporting obligations that take effect on 1 July 2015.

34. ASIC’s full response is included at Appendix 1.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.50 |

To assess the effectiveness of enforceable undertakings as an appropriate regulatory tool and their contribution to ASIC achieving its compliance objectives, the ANAO recommends that ASIC:

ASIC response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.62 |

To strengthen decision-making and support the transparency of, and quality assurance over enforceable undertakings, the ANAO recommends that ASIC:

ASIC response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides background information on ASIC and the use of enforceable undertakings as a regulatory tool. It also outlines the audit objective and approach.

Background and context

1.1 Australia’s financial system plays an essential role in supporting the economic prosperity of Australians, by providing consumers and businesses with banking, investment, superannuation and insurance services. Among other things, Australia’s financial system is crucial to enabling businesses to attract capital to expand their businesses, providing the means for consumers to borrow to fund large purchases and allowing individuals to provide for their retirement. In recent years, there has been significant growth in Australia’s financial system, with financial system assets growing from two years’ worth of Australia’s nominal gross domestic product in 1997 to more than three times nominal gross domestic product in 2013.18 At December 2014, financial institutions in Australia controlled assets of around $6 trillion.19

1.2 The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) is Australia’s corporate, financial markets, financial services and consumer credit regulator. It seeks to ensure the markets it regulates are fair and transparent, supported by confident and informed investors and consumers. Together with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority and the Reserve Bank of Australia, ASIC plays a major role in regulating Australia’s financial system. One of ASIC’s most important responsibilities20 is to ensure that regulated entities comply with their legal obligations, including obligations under the Corporations Act 2001.

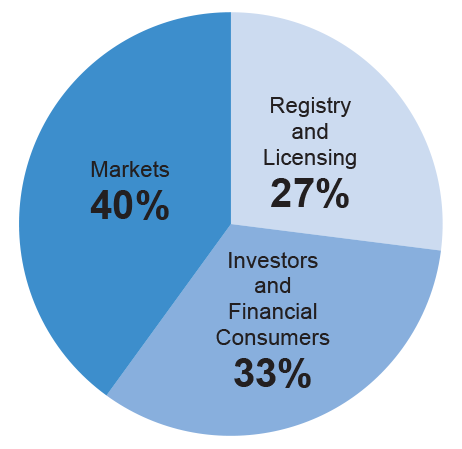

1.3 In 2013–14, ASIC’s operating expenditure was $341 million. As shown in Figure 1.1, 40 per cent of this expenditure was directed towards markets. This strategic priority broadly covers corporate governance21 and market integrity, and involves regulating the 2.2 million registered companies in Australia22 and supervising trading on Australia’s domestic equities, derivatives and futures markets. As at 30 June 2014, there were 40 authorised financial markets and six licensed clearing and settlement facilities. Australia’s largest financial market is the Australian Stock Exchange, one of the largest share markets in the world, with a domestic equities market capitalisation of $1.57 trillion.23

Figure 1.1: ASIC’s resource allocation by strategic priority, 2013–14

Source: ASIC Annual Report 2013–14.

1.4 The other significant area of regulation carried out by ASIC is in relation to investors and financial consumers, to which 33 per cent of ASIC’s resources were directed in 2013–14. In relation to investors and financial consumers, ASIC is responsible for, among other things:

- monitoring financial services businesses to help ensure they operate efficiently, honestly and fairly; and

- ensuring persons who engage in credit activities meet the standards—including their responsibilities to consumers—that are set out in the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009.

1.5 In 2013–14, ASIC oversaw 3391 Australian financial services licensees that provide personal financial advice, 3673 registered managed investment schemes and 5837 Australian credit licensees.24 The considerable resources directed towards investors and other financial consumers reflects the significant role that financial services play in Australia’s economy and its essential contribution to investment, savings and retirement incomes.

1.6 The importance of effective financial regulation in Australia was illustrated by the collapses of Storm Financial and Opes Prime in 2008–09. In the case of Storm Financial, around 3000 of its clients, typically individuals seeking to generate retirement savings and income, suffered combined losses of around $830 million. Many of these clients were required to sell their homes.25 In respect of Opes Prime, a securities lending and stockbroking firm, creditors sold the securities for a small proportion of their initial worth. Consequently, Opes Prime’s clients, many of whom thought the arrangement was a standard loan, suffered losses such as their entire retirement savings and forced sales of family homes, as well as breakdowns in personal relationships and ill health.26 There have also been instances of inappropriate or predatory lending practices, which are often targeted at vulnerable, disadvantaged or low-income consumers.27

1.7 ASIC’s compliance model is based on a ‘detect, understand and respond’ approach.28 Detection occurs through surveillance, reports from the public and whistleblowers, data gathering and matching, and intelligence. ASIC responds to non-compliance, or the risk of non-compliance, by: disrupting harmful behaviour; taking enforcement action; communicating the actions it takes; educating investors and financial consumers; providing guidance to ‘gatekeepers’29; and providing policy advice to Government.

1.8 In conducting its 2013–14 regulatory activities, 35 per cent of ASIC’s resourcing was directed towards enforcement and 20 per cent towards surveillance activities. ASIC’s surveillance activity generally involves monitoring entities to determine whether they are complying with the relevant legislation. ASIC adopts a risk-based approach to surveillance, which may be proactive or reactive. For example, ASIC may proactively target the largest firms in a market through site visits and desk-based reviews, or it may be reactive, in response to breach reports, or reports of misconduct from the public and whistleblowers. Where ASIC identifies misconduct as a result of its surveillance activity, public or statutory reports, or referrals from another regulator, it may take enforcement action. Enforcement is one of the many regulatory tools available to ASIC, and is used to deter misconduct. Enforcement includes: taking criminal action (such as seeking imprisonment); commencing civil proceedings (including seeking civil penalty orders); taking administrative action (such as banning orders and imposing licence conditions); or accepting a negotiated outcome (including an enforceable undertaking).

Enforceable undertakings

1.9 An enforceable undertaking (EU) is a written undertaking, given to ASIC by a regulated entity, that it will operate in a certain way.30 For example, an EU may typically require an entity or an individual (the promisor) to:

- remedy the deficiencies in a company’s compliance systems by taking certain specified action, and having this reviewed by an independent auditor or expert;

- complete additional professional education, or for a set period of time, refrain from performing a significant role in an audit engagement, or be subject to technical supervision on future audit engagements;

- inform the market to correct false or misleading disclosures;

- perform a community service obligation (for example, by funding an education program for consumers of particular financial services); or

- write to investors or parties affected by misconduct, advising them of the existence of the EU, its terms and how a copy of it can be obtained.31

1.10 EUs are used as an alternative to civil court action or administrative actions (such as banning orders, imposing licence conditions, or issuing an infringement notice). In comparison to these, EUs provide a tailored and more certain outcome that can, for example, involve entities making substantial changes to their systems and cultures and, in appropriate cases, making restitution. EUs may be preferred to civil action as the latter is usually lengthier and the outcome is uncertain. Administrative actions such as infringement notices may not lead to cultural or behavioural change, as the entity may see the penalty as simply a cost of doing business. An EU is not an alternative to commencing criminal action, or to be used in cases of deliberate misconduct, fraud, or conduct involving a high level of recklessness.32

1.11 ASIC is able to accept EUs from individuals and corporations and in respect of any area where ASIC has regulatory responsibility.33 ASIC considers EUs are ‘an important component in [its] array of enforcement remedies to influence behaviour and encourage a culture of compliance’. In its view, an EU ‘can sometimes offer a more effective regulatory outcome than could otherwise be achieved through other available enforcement remedies’.34 EUs have been identified as a form of restorative justice, where the objective is to address the harm done (restoration), repair relationships, and reduce recidivism.35

1.12 Where an EU is not complied with, ASIC may apply to a court (generally, the Federal Court of Australia) for relevant orders, including for the promisor to: comply with a term of the undertaking; pay the Commonwealth an amount up to the amount of any financial benefit directly attributable to the breach; or compensate any other person who has suffered loss or damage as a result of the breach. Failure to comply with such an order is a contempt of court.

ASIC’s use of enforceable undertakings

1.13 ASIC’s use of EUs in the context of its other enforcement activities covering the period 1 January 2012 to 30 June 2014 is outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: ASIC enforcement outcomes, 1 January 2012 to 30 June 2014

|

Area of enforcement |

Criminal convictions |

Civil outcomes(1) |

Administrative remedies |

EUs/ negotiated outcomes(2) |

Public warning notices |

Total |

|

Market Integrity |

29 |

4 |

38 |

4 |

0 |

75 |

|

Corporate Governance |

24 |

9 |

11 |

16 |

1 |

61 |

|

Financial services |

40 |

41 |

140 |

77 |

5 |

303 |

|

Small business compliance and deterrence |

1 105(3) |

2 |

165 |

0 |

0 |

1 272 |

|

Total |

1 198 |

56 |

354 |

97 |

6 |

1 711 |

Source: ASIC, Report 383: ASIC enforcement outcomes: July to December 2013 and ASIC, Report 402: ASIC enforcement outcomes: January to June 2014.

Note: ASIC reports outcomes per defendant, rather than per matter.

Note 1: Civil outcomes include declarations, injunctions and civil penalty orders.

Note 2: The figure for EUs also includes other negotiated outcomes. An example of an ‘other negotiated outcome’ is where ASIC negotiated with a home loan lender to have the lender refund early termination fees paid by consumers in breach of the relevant consumer credit law. ASIC’s publicly available enforcement statistics do not separate EUs from other negotiated outcomes.

Note 3: The large number of criminal convictions arising from small business compliance and deterrence activities reflects the high-volume investigative activities of ASIC’s Small Business Compliance and Deterrence team. These activities include: taking action against directors who fail to assist liquidators when their companies fail; investigating and banning directors; and preparing criminal briefs for matters including breaches of director’s duties, managing while disqualified, lodging false documents and failing to lodge financial statements.

1.14 Table 1.1 combines EUs and negotiated outcomes. To determine the number and nature of EUs entered into from 1 January 2012 to 30 June 2014, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examined ASIC’s EUs register, available on its website (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2: Number and nature of enforceable undertakings entered into by ASIC, 1 January 2012 to 30 June 2014

|

|

|

EUs, by entity size |

EUs, by area of enforcement |

|||||

|

Year |

Total EUs |

Large(1) |

Small |

Individual |

Auditors and Liquidators |

Financial Services |

Consumer Credit |

Other(2) |

|

2012 |

18 |

2 |

0 |

16 |

7 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

|

2013 |

25 |

7 |

8 |

10 |

3 |

12 |

8 |

2 |

|

2014(3) |

10 |

1 |

5(4) |

5(4) |

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

|

Total |

53 |

10 |

13 |

31 |

13 |

22 |

13 |

5 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note 1: The Australian Bureau of Statistics definition of a large business is used—that is, one with 200 or more employees.

Note 2: Includes two EUs relating to influencing the Bank Bill Swap Rate, one EU relating to a breach of continuous disclosure obligations, one EU relating to corporate governance and one EU involving market misconduct.

Note 3: These figures are for the half year to June 2014. A further 13 EUs were accepted by ASIC in the period 1 July 2014 to 31 December 2014.

Note 4: The figures for EUs by entity size in 2014 add to 11 (rather than 10) because one EU accepted during the year involved both small companies and individuals associated with those companies.

1.15 From July 1998 (when EUs were introduced) to December 2014, a total of 388 EUs were accepted by ASIC (an average of 24 annually) and from January 2010 to December 2014, 92 EUs were accepted (an average of 18 annually). Table 1.2 shows that in 2013 and the first half of 2014, ASIC entered into more EUs with companies than with individuals. In this period, the EUs also related to comparatively more credit and financial services matters.

Parliamentary and other external scrutiny of ASIC

1.16 In June 2013, the Senate referred the performance of ASIC to the Senate Economics References Committee for inquiry. The terms of reference for the inquiry were:

- ASIC’s enabling legislation, and whether there are any barriers preventing ASIC from fulfilling its legislative responsibilities and obligations;

- the accountability framework to which ASIC is subject, and whether this needs to be strengthened;

- the workings of ASIC’s collaboration and relationships with other regulators and law enforcement bodies;

- ASIC’s complaints management policies and practices;

- the protections afforded by ASIC to corporate and private whistleblowers; and

- any related matters.36

1.17 The Senate Economics References Committee tabled its final report on 26 June 2014. One area of focus for the Committee was the allegations of serious misconduct engaged in by financial advisers at Commonwealth Financial Planning Limited (part of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia Group) between 2006 and 2010. The chair of the Committee stated that ASIC’s slow response to the case and lack of scepticism was hard to explain, and that the agency ‘allowed itself to be lulled into complacency and placed too much trust in an institution that sought to patch over its problems.’ He added that:

The good work that ASIC has done in a challenging environment has been recognised. Even so, there is a need for ASIC to become a far more proactive regulator ready to act promptly but fairly. ASIC also needs to be a harsh critic of its own performance with the drive to identify and implement improvements.37

1.18 The Committee made 61 recommendations generally aimed at enabling ASIC to fulfil its responsibilities and obligations more effectively and to promote greater confidence in the regulator. The Committee also raised concerns about ASIC’s enforcement decisions, and particularly, its use of EUs. Potential issues regarding ASIC’s EU processes and practices raised in submissions and highlighted by the Committee included:

- the extent of ASIC’s reliance on EUs, particularly as a remedy for misconduct by large entities—the Committee quoted submissions that suspected ASIC might have been ‘soft on the big end of town’;

- the clarity of EUs in specifying remedial actions and whether the undertakings placed sufficient conditions on entities whose strategies may be damaging financial consumers and investors;

- the extent of detail included in the EU about the alleged misconduct, such that other market participants may not be aware of the purpose of the undertaking;

- in its approach to negotiating EUs, ASIC may give excessive regard to the burden an undertaking might impose on a company; and

- scope to improve transparency in relation to the monitoring of EUs, such as through making publicly available the reports provided to ASIC by independent experts appointed as a condition of the undertaking.38

1.19 As a consequence of these concerns, the Senate Economics References Committee included in its report a recommendation that the Auditor-General consider conducting a performance audit of ASIC’s use of EUs, including:

- the consistency of ASIC’s approach to EUs across its various stakeholder and enforcement teams39; and

- the arrangements in place for monitoring compliance with EUs that ASIC has accepted.

1.20 The Auditor-General accepted the recommendation and agreed to conduct the audit, which is the subject of this report.

1.21 ASIC has responded to the Committee’s concerns, stating that EUs are not a soft option but a very effective regulatory tool ‘that generally require the person offering the EU to implement significant changes to the way they operate, and to provide substantial compensation, conditions that may be enforced in court’. It also noted that, ‘like all Commonwealth agencies, ASIC is required to act as a model litigant, including trying wherever possible to avoid court proceedings and considering settlements where appropriate’.40

Previous ANAO coverage of ASIC

1.22 The ANAO has undertaken the following two performance audits of ASIC, tabled in 2006 and 2007:

- Audit Report No. 25 2005–06, ASIC’s Implementation of Australian Financial Services Licences; and

- Audit Report No. 18 2006–07, ASIC’s Processes for Receiving and Referring for Investigation Statutory Reports of Suspected Breaches of the Corporations Act 2001.

1.23 An element of ASIC’s registry functions was also included in the cross-agency audit of the Administration of the Australian Business Register, which was tabled in June 2014. None of these reports covered ASIC’s administration of EUs.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.24 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s administration of enforceable undertakings.

1.25 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO has adopted the following high-level criteria:

- management arrangements are in place that support the effective, consistent and transparent administration of EUs;

- offers of EUs are administered consistently, transparently and in accordance with ASIC’s policies and procedures; and

- EUs accepted by ASIC are monitored to ensure compliance with those undertakings, action is undertaken where non-compliance is identified and the effectiveness of EUs as a regulatory tool is assessed.

Audit methodology

1.26 The audit examined ASIC’s use of EUs as a regulatory tool across all stakeholder and enforcement teams involved in administering EUs. The audit examined all 53 EUs that were accepted by ASIC from 1 January 2012 to 30 June 2014.

1.27 The audit methodology included consulting with stakeholder groups and professional advisers with relevant experience and expertise, interviewing ASIC staff41, and examining relevant documentation and systems.

1.28 The audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost of approximately $365 000.

Report structure

1.29 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.3 and reflects the audit criteria in paragraph 1.25.

Table 1.3: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview of chapter |

|

|

2 |

Managing Enforceable Undertakings |

Examines ASIC’s arrangements to support the administration of enforceable undertakings. |

|

3 |

Entering into Enforceable Undertakings |

Examines whether ASIC enters into enforceable undertakings consistently, transparently and in accordance with its own policies and procedures. |

|

4 |

Monitoring Compliance with Enforceable Undertakings |

Examines ASIC’s monitoring of enforceable undertakings, action taken to address non-compliance, and reporting on compliance with the undertakings. |

2. Managing Enforceable Undertakings

This chapter examines ASIC’s arrangements to support the administration of enforceable undertakings.

Introduction

2.1 Sound management and governance arrangements support regulators to meet their legislative and regulatory responsibilities and to be accountable for their decisions, actions and performance.42 Regulators also need a risk-based compliance and enforcement approach that communicates regulatory requirements and how these requirements will be monitored and enforced in a consistent and transparent manner.

2.2 The ANAO examined ASIC’s:

- compliance and enforcement approach;

- management arrangements, including for the oversight and quality control of EUs;

- performance monitoring and reporting processes; and

- guidance and training arrangements that support ASIC officers involved in negotiating and monitoring compliance with EUs.

Compliance and enforcement approach

2.3 Regulators should have a compliance and enforcement approach that is risk-based and proportionate, and that supports consistency, accountability and transparency.43 The approach should also be designed to promote voluntary compliance, and to detect and deal with non‐compliance.

Compliance approach

2.4 ASIC’s compliance approach is set out in its Strategic Framework and is based on a three stage process; detect, understand and respond (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: ASIC’s approach to non-compliance

Source: ANAO, based on ASIC information.

Detecting and understanding misconduct or the risk of misconduct

2.5 ASIC detects misconduct or the risk of misconduct (including potential systemic industry issues) through the four main sources listed in Figure 2.1. ASIC states that it takes a proactive and risk-based approach to detecting and understanding misconduct.44 At the strategic level, this occurs through formal business planning and risk management processes.45 At the operational level, ASIC identifies, analyses and evaluates risks in the regulated population and focuses surveillance activities46 on those areas it considers to be the highest risk. This program sits alongside reactive surveillance work, which arises from reports from whistleblowers, complaints from the public or breach reports.47 A key focus for ASIC is detecting and understanding the drivers of risks to investors, financial consumers, and the sectors and participants that it regulates.

Responding to misconduct or the risk of misconduct

2.6 Where misconduct or the risk of misconduct (such as industry-wide issues or issues relating to the introduction of new regulation) is detected and understood, ASIC has a variety of responses, as outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: ASIC’s responses to misconduct or the risk of misconduct

|

Response |

Explanation |

|

Communication |

ASIC communicates the actions it takes to promote compliance with the law by informing the public about the standards it expects and the consequences of failing to meet those standards. Examples include media releases reporting ASIC’s compliance activities and corporate publications (such as ASIC’s Strategic Outlook). |

|

Education |

ASIC helps investors and financial investors and consumers make appropriate choices when they deal with money and financial products and services through its MoneySmart website and Indigenous Outreach Program. |

|

Enforcement |

ASIC takes a range of actions (including administrative, civil and criminal action) to enforce the law and deal with misconduct that puts investors and fair and efficient markets at risk. |

|

Engaging with industry and stakeholders |

ASIC engages with industry and stakeholders to assist regulated entities to meet their obligations under Australian law, and to detect misconduct, by gathering intelligence and understanding market and consumer behaviour. In 2013–14, ASIC held 1172 meetings with industry groups and other stakeholders. |

|

Policy advice |

ASIC provides policy advice to Government on law reform that might be required to overcome problems that it encounters in administering or enforcing legislation, or as a response to changes in financial markets. |

|

Guidance and other regulatory documents |

ASIC issues regulatory guides and information papers to assist regulated entities in complying with the law. This guidance explains when and how ASIC will exercise specific powers, how it interprets the law and provides practical guidance for entities (such as outlining the process for applying for a licence or giving practical examples about how regulated entities may decide to meet their obligations). |

Source: ANAO analysis of ASIC information.

2.7 ASIC publications emphasise the importance of voluntary compliance. For example, ASIC’s guidance on corporate compliance states: ‘we encourage high levels of voluntary compliance by being up-front about our educative and enforcement strategies and helping companies and officeholders comply with their obligations’.48 Further, Information Sheet 172: Cooperating with ASIC encourages entities to cooperate with ASIC, including by self-reporting misconduct.49 As outlined in Table 2.1, where ASIC identifies misconduct, it may take enforcement action in respect of that conduct.

Enforcement approach

2.8 ASIC’s overall enforcement approach is set out in Information Sheet 151: ASIC’s approach to enforcement, which is available on its website.50 This information sheet covers the range of regulatory tools that ASIC can use to improve confidence in Australia’s financial markets and facilitate fair and efficient markets. These tools include education, engagement and guidance, and using its enforcement powers such as criminal and civil sanctions, administrative remedies and negotiated outcomes, depending on the seriousness and consequences of the misconduct.

2.9 ASIC’s approach to enforcement is similar to the commonly-used ‘regulatory pyramid’ compliance model. The model involves the less frequent use of the most severe sanctions, which form the apex of the pyramid, compared to the persuasion-focused methods of resolution that form the pyramid’s base.51 More severe sanctions, such as imprisonment of individuals involved in the misconduct and high pecuniary penalties, are used where the conduct is more serious and there is an unwillingness of the regulated entity to comply with the law. Where the conduct is less serious and the regulated entity is co-operative, the model identifies more moderate sanctions as being appropriate. ASIC advised that it sees EUs as normally sitting towards the bottom of the compliance pyramid, although this will depend on the content of a particular EU.

2.10 ASIC has processes in place to consider appropriate enforcement action. The decision whether to conduct a formal investigation will depend on ASIC’s initial assessment of the extent of harm or loss, the benefits of pursuing the misconduct and the seriousness of the misconduct. ASIC’s decision-making process is set out in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: ASIC’s approach to enforcement

Source: ASIC Information Sheet 151: ASIC’s approach to enforcement.

Role of enforceable undertakings

2.11 In terms of EUs, the role of these regulatory tools in ASIC’s enforcement approach is outlined in ASIC’s Regulatory Guide 100: Enforceable Undertakings. According to this guide, ASIC views EUs: ‘as an important component in [its] array of enforcement remedies to influence behaviour and encourage a culture of compliance for the benefit of all participants’. Importantly, ASIC considers: ‘that an [EU] can sometimes offer a more effective regulatory outcome than could otherwise be achieved through other available enforcement remedies, namely civil or administrative action’.52

2.12 Before deciding whether to accept an EU, ASIC will have already undertaken a number of compliance actions, including conducting a surveillance activity and/or an initial investigation of the regulated entity. A decision is then taken whether to conduct a formal investigation, based on a consideration of the matter’s strategic significance (including the seriousness of the misconduct, its impact on the market, and the likelihood and consequences of the conduct causing harm to investors and others) and the benefits of pursuing the misconduct.

2.13 If a breach is established and enforcement action is justified, ASIC may consider accepting an EU from among the enforcement tools available (outlined in the following section). This consideration involves an assessment of factors influencing the risk to the community, such as the compliance history of the entity, and whether it is likely to comply with the EU.53 ASIC will also consider the relative uncertainty of an alternative course of action, such as a court, tribunal or disciplinary body action. For example, if an EU leads to a liquidator agreeing not to practice for three years, this may be preferred to Companies Auditors and Liquidators Disciplinary Board proceedings, where an outcome is uncertain and ASIC might have judged the likely outcome as being a ban of between two and four years.54

Alternatives to enforceable undertakings

2.14 As previously discussed, ASIC has a range of tools to achieve its regulatory objectives. The selection of an EU is dependent on a comparison of the regulatory effectiveness of an EU to the other regulatory options available. These other options are outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Regulatory alternatives to enforceable undertakings

|

Type of sanction |

Effectiveness |

Transparency |

Consequences |

|

Administrative action |

|||

|

Licence conditions and cancellations |

Can protect the public by excluding an entity from the industry in a relatively timely manner, or imposing conditions on the way in which they operate. There are a wide-range of conditions that can be imposed. |

The result is public, as details about any licence cancellations or conditions are publicly available through ASIC’s professional registers. |

A licence cancellation will result in exclusion of the entity from the industry. The effect of licence conditions will depend on the conditions that are imposed. |

|

Banning or disqualification order |

Can protect the public by resulting in the exclusion of an entity from the industry in a relatively timely manner. |

The result is public, as the person is placed on a register of banned or disqualified persons. |

The person is banned or disqualified from providing specified services, usually for a period. |

|

Infringement notice |

May not change the entity’s culture (that is, it can be seen as a ‘cost of doing business’). Legislation does not provide infringement notice powers for some types of misconduct. |

The result is public, as details are placed on an infringement notice register and a media release issued. |

Several different regimes have differing levels of penalty. |

|

Court action (civil or criminal action) |

|||

|

Civil action (civil penalties and/or the seeking of injunctions, declarations and compensation orders) |

Quantum of a civil penalty may not provide strong deterrence or result in behavioural change. Can achieve outcomes that result in the remediation of consumers/investors. Publicity of outcome may have strong deterrence impact. |

The result is public as a court imposes a penalty (and ASIC issues a media release). |

Depend on the contravention. Under the Corporations Act 2001, the maximum civil penalty is $200 000 for individuals and $1 million for corporations. Compensation orders are also possible. |

|

Court action (civil or criminal action) (continued) |

|||

|

Criminal action |

Can protect the public by resulting in the imprisonment of a person. Criminal action can have a very strong deterrence impact; however, charges can take a long time to be heard by a court. |

The result is public as a court imposes a penalty (and ASIC issues a media release). |

Depend on the offence. Prison terms of up to 10 years; or fines up to $765 000 for individuals or $7.7 million for companies, or three times the benefit gained. |

|

Companies Auditors and Liquidators Disciplinary Board |

|||

|

Cancellation, suspension or undertaking |

Can protect the public by resulting in the temporary or permanent exclusion of a person from the industry. The Companies Auditors and Liquidators Disciplinary Board can also make other orders (such as requiring a person to undertake education) to reduce the possibility of reoffending. |

Proceedings are in private unless and until an adverse finding is made. |

May cancel registration or suspend for a specified period of time. May also obtain an EU, or admonish or reprimand. |

|

Other negotiated outcomes |

|||

|

Examples include an agreement to:

|

These are highly flexible, and due to the informality, can be achievable in a relatively short timeframe. These undertakings might not be court enforceable. |

Negotiated in private, but normally publicised in a media release. There is currently no formal ASIC policy, definition or public register. |

Vary depending on the terms of the agreement. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ASIC information.

2.15 As indicated in Table 2.2, EUs have a significant role to play in ASIC’s enforcement approach where other regulatory options: are unavailable; would not produce an outcome commensurate with the harm caused; or have other disadvantages. A potential benefit of EUs is in driving changes in an entity’s culture and systems, whereas an administrative penalty, or even a civil sanction, may not lead to behavioural change. Recognising this benefit, the Senate Economics References Committee concluded that EUs may correct behaviour within a particular organisation, but added that these undertakings ‘do not yield the wider and more significant regulatory benefits that are associated with successful court action’.55 While a favourable court decision may have a greater general deterrent effect than an EU, as indicated in Table 2.2, the outcome of court action is uncertain in terms of the sanction56 that a court might impose and the consequential effect on the entity’s business (such as improved compliance processes). During the period 1 January 2012 to 30 June 2014, as outlined in Table 1.1, there were a total of 1711 enforcement outcomes, of which 97 were EUs or other negotiated outcomes.

Other negotiated outcomes

2.16 As mentioned in Chapter 1, ASIC sometimes reaches negotiated outcomes with regulated entities that are not EUs (that is, they are not enforceable by statute, although they may be enforceable as a contract). These types of outcomes are used across a variety of matters. At the lower end, ASIC negotiates outcomes that involve, for example, an exchange of letters leading to the correction of misleading or deceptive conduct. At the higher end, a negotiated outcome may be similar to an EU. While these other negotiated outcomes can be quite significant, ASIC does not have a policy, definition or public register for this type of activity. There can also be less clarity about announcing the terms of the settlement.57

2.17 Based on information provided by ASIC, the ANAO identified that in 2013–14, ASIC finalised at least 113 negotiated outcomes other than an EU.58 However, given that ASIC does not have a policy, clear definitions or public register in relation to negotiated outcomes, these numbers are not exhaustive, and there are likely to be additional outcomes resolved through negotiations by the stakeholder and enforcement teams. To give regulated entities more certainty and to increase transparency, there would be merit in ASIC providing greater clarity around the circumstances in which it accepts and enters into other negotiated outcomes.

Management arrangements for enforceable undertakings

2.18 To help ensure that regulatory decisions (including for the use of EUs) are made consistently, transparently and proportionately, it is important that sound management arrangements are in place. Accordingly, the ANAO examined ASIC’s management arrangements for EUs.

2.19 As previously discussed, ASIC may become aware of a potential enforcement matter in a number of ways, including through reporting of misconduct and breaches. These matters can be referred to the relevant ASIC stakeholder team for further review or directed to an enforcement team to consider undertaking an investigation or initiating enforcement action.59

2.20 Depending on the nature of the EU, staff from the enforcement and stakeholder teams will have varying degrees of involvement. EUs are generally negotiated and finalised by enforcement teams, which will also undertake monitoring if prompt follow-up action is required (for example, a community benefit payment must be made by a certain date). Otherwise, the stakeholder team, which is better placed to have an ongoing relationship with the promisor, monitors the EU. The relevant stakeholder and enforcement teams are expected to liaise with each other as necessary, for example to ensure that an EU contains appropriate terms and that the promises given will take into account the position of those affected by the alleged breaches. In practice, as discussed in paragraphs 4.12 to 4.14, the respective teams generally did consult as required.

Roles of senior executives and executive committees

2.21 According to ASIC guidance, a Senior Executive Leader (SEL)60 must be consulted before ASIC enters into negotiations for a possible EU, and generally approves the EU. As at November 2014, there were 21 SELs (and two Senior Executives), whose roles included considering and approving EUs.61 For the 53 EUs reviewed by the ANAO, all were formally approved and signed by a SEL or a Senior Executive.

2.22 To support SELs, ASIC has an Enforcement Committee that makes decisions about the conduct, strategy and focus of major compliance matters and other significant enforcement actions, which can include EUs.62 Records indicate that the Committee has considered aspects of the administration of EUs, including the current status and whether an EU was being considered for, or had been concluded with, an entity.63 There were also action items and matters carried forward (with due dates and persons responsible), and a record of the Committee’s decisions.

2.23 The Office of the Chief Legal Office (CLO) provides legal, strategic and other input into major compliance cases, and assists enforcement and stakeholder teams. In relation to EUs, the CLO is responsible for the policy and procedures, and is required to provide assurance about drafting clarity, legal certainty, enforceability and compliance with ASIC policies before ASIC accepts each EU. As discussed in Chapter 3, for most of the 53 cases examined by the ANAO, there was evidence of the CLO’s involvement in the EU process.

Internal monitoring and reporting of enforceable undertakings

2.24 Accurate performance reporting should inform ASIC senior managers of the extent to which regulatory objectives are being met and support management decision-making. In the case of EUs, it was expected that senior executives would track these in a systematic way to monitor how long negotiations are taking, what outcomes they are achieving, and if they have been effective in changing behaviours.

Internal monitoring and reporting of EU negotiations

2.25 Prior to acceptance of an EU, each stakeholder and enforcement team reports on the progress of the EU negotiation as part of their regular fortnightly and monthly reports. The reports provide a summary of developments in the cases being addressed by each team, including EUs.64 With respect to EUs, the reports provide an update on the status of negotiations and any problem areas. However, the reports do not document senior management consideration and feedback (if any) regarding the progress of matters or suggested changes of approach. It would be helpful if reporting also focused on matters such as timeliness, obstacles faced or issues that have arisen in negotiations with entities, and shareing better practices where appropriate across teams.

Internal monitoring and reporting of EU compliance

2.26 It is important that there is appropriate oversight and accountability by senior management after an EU has been signed. This requires regular reporting to senior management about compliance with, and outcomes of, EUs.

2.27 In September 2014, the CLO developed a spreadsheet with information on the status of existing EUs, for consideration at Commission meetings. While the spreadsheet provides useful information for the Commission65, it covered only around half of the EUs reviewed as part of the audit, and was limited to EUs involving ongoing positive obligations (undertakings to do or performance a certain act). To improve senior management visibility over the administration of EUs, further work could be undertaken to consider the coverage of EUs in the CLO report.

2.28 Overall, internal reporting on EUs is currently limited to reporting on the progress of EU negotiations, and more recently compliance with undertakings for some EUs. To reflect better practice and support senior management oversight of EUs, there would be merit in ASIC improving internal reporting to provide a greater focus on timeliness of EU negotiations, and consistency in approaches between stakeholder and enforcement teams.

Guidance, systems and training

2.29 As part of the audit, the ANAO examined the guidance, records management systems and training arrangements ASIC has in place to support its staff in entering into and monitoring compliance with EUs.

Guidance

2.30 ASIC has the authority to accept EUs under sections 93AA and 93A of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 and section 322 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (in relation to Commonwealth credit legislation). These provisions are broadly drafted and provide ASIC with discretion to exercise this authority.

2.31 Given the lack of specificity in these Acts, it is important for ASIC to issue guidance on how it exercises its authority, to support consistent decision-making processes and provide transparency about the criteria on which decisions will be based. ASIC uses a range of public and internal guidance documents to explain how it administers EUs. The key public guidance document is Regulatory Guide 100, which was last updated in February 2015 and is available on ASIC’s website.66 The guide sets out: the circumstances in which ASIC will accept EUs; the terms that are acceptable or not acceptable to ASIC; how ASIC will report publicly on the outcomes of an EU; and how ASIC will respond to non-compliance with an EU.

2.32 While ASIC will normally follow the principles set out in a regulatory guide, it will not do so inflexibly or uncritically. In a particular instance, ASIC may form the view that there are relevant considerations that are not set out in its policy, but which it is required by law to take into account in making its decision. For example, ASIC’s policy states that it will not normally accept an EU in which the promisor does not at least acknowledge that ASIC’s views in relation to the misconduct which gave rise to the EU are reasonably held. However, in eight cases, ASIC did not insist on an acknowledgement clause, generally because an EU without such a clause was still viewed as the most effective regulatory outcome in the matter.

2.33 There are a number of public documents that further support ASIC’s EU policy: a policy on public comment, which outlines that it will usually issue a media release or media advisory when it accepts EUs and agreements by people to change their conduct67; and a policy on cooperation, that states that cooperation will be relevant to ASIC’s decision on the type of enforcement action to pursue or remedy to seek.68 Finally, ASIC’s Service Charter provides that ASIC is committed to ‘making consistent decisions, and advising [entities] of [its] decisions in a timely manner’.69

Internal guidance

2.34 In addition to its public guidance, ASIC has a number of internal documents to guide its decision-making in relation to EUs. The most important of these is its Enforcement Manual, which provides detailed guidance to staff on how ASIC exercises its enforcement powers. The manual includes a chapter on EUs that sets out the process by which ASIC will enter into an EU. As previously noted, the CLO is responsible for ASIC’s policy and practice in relation to EUs. It provides and revises internal guidance on EUs and manages a Technical and Procedures Library, which is available to all staff and includes a page dedicated to EUs.

2.35 Overall, these documents contain clearly defined regulatory objectives and comprehensively set out the considerations that are taken into account in deciding whether an EU will be accepted, and if so under what terms.

2.36 Stakeholders and ASIC staff interviewed by the ANAO during the audit raised few concerns about their ability to apply ASIC’s guidance. However, some stakeholders suggested there could be more guidance provided regarding the appointment of, and ASIC’s expectations for, independent experts (discussed in Chapter 4). In relation to independent experts, these concerns have been largely addressed by the publication of a revised Regulatory Guide 100 in February 2015.

Records management systems

2.37 The recording of regulatory actions and the reasons for these actions is important for both transparency and accountability.70 Consistent with these principles, ASIC’s internal Governance Protocol states that: ‘record keeping in relation to all matters, should be comprehensive, orderly and readily accessible’.71

2.38 ASIC officers use a range of disparate systems to track and store their work, including in relation to EUs:

- Search tools—ASCertain (a mainframe system) and the data warehouse search tool (a web-based system) allow ASIC staff to search across the data holdings in ASIC’s mainframe systems and workflow systems to research companies and individuals of interest.

- Registers—ASCOT is a mainframe system that is ASIC’s main registry system. It contains details about registered companies, persons associated with companies (such as directors), as well as professional registration information regarding auditors, liquidators and licensing information (including about Australian financial services licensees and Australian credit licensees).

- Workflow systems—The workflow systems are databases that are used for case management and reporting. The use of the workflow systems is inconsistent across the organisation.

- Document management—The main systems for recording documentation are ASIC’s paper files (centrally tracked through the EPSOM system) and ASIC’s electronic documents and records management system, ECM. In addition, the ANAO identified that ASIC staff also stored files in the workflow systems (referred to above), in staff emails or hard files, and in shared drives.

2.39 It was common for information relevant to an EU to be held in multiple systems (ECM, paper files and a workflow system). In many cases, these systems did not have all of the information relating to the EU and the ANAO had to obtain the documentation from the relevant ASIC officer (from staff emails or hard files). This presents risks for ASIC, as staff responsible for a certain part of the EU process (such as monitoring) may not have sufficient information to effectively carry out their responsibilities, particularly as matters often need to be handed over from stakeholder to enforcement teams, and vice versa. Accordingly, there would be value in consolidating information relating to EUs to reduce duplication, improve accessibility and facilitate better internal and external oversight of the EU process. A key first step would be to reinforce to staff the need to store all documentation relating to an EU in accordance with ASIC policies and procedures.

Staff training

2.40 ASIC mainly regards training in EUs as being acquired through on-the-job experience. Accordingly, it does not provide formal training. A significant proportion of ASIC’s workforce has undertaken legal studies (at least 350 of 1816 total staff, with a higher proportion of legally qualified persons in the enforcement and stakeholder teams), which should better position them to understand and apply the relevant rules and procedures. As previously noted, ASIC also provides guidance that is clear, comprehensive and straightforward to apply.

2.41 Notwithstanding the skill profile of ASIC’s staff and the availability of suitable guidance, the organisation is undergoing significant staff turnover, with staffing levels expected to fall by 209 (or 12 per cent) in 2014–15.72 This level of staff turnover and loss of corporate knowledge presents risks to administration, and there would be merit in ASIC considering whether some level of formal EU training should be provided.

Monitoring and reporting on the performance of enforceable undertakings

2.42 The Australian Government’s performance measurement and reporting framework requires entities to set out their outcome, programs, deliverables, key performance indicators (KPIs) and expenses in their Portfolio Budget Statements and to report against these in the annual report. Specifically:

- deliverables provide information on the goods and/or services produced and/or delivered; and

- KPIs provide information on how effective the program has been in achieving outcomes.

ASIC’s outcome, Program 1.1 Objective and KPIs for 2014–15 are set out in Figure 2.3.73

Figure 2.3: ASIC’s key performance indicators for 2014–15

Source: ANAO, based on ASIC Portfolio Budget Statement 2014–15.

2.43 ASIC states that it delivers on its outcome and program objective through engagement with industry and stakeholders, surveillance, guidance, education, enforcement activities and policy advice. The impact and results of these activities are measured using 10 KPIs across ASIC’s three strategic priorities. The KPIs applicable to EUs are: misconduct is dealt with and deterred; fair and efficient processes are in place for resolution of disputes; product issuers, credit providers and advisers meet required standards; participants in financial markets meet required standards; and issuers (of securities) and their officers meet required standards.

2.44 These KPIs are designed to provide information that would assist in determining how ASIC undertakes its regulatory activities, including through EUs. However, in relation to the first two KPIs, ASIC has only reported in a limited way in its 2013–14 Annual Report74, and did not report against the other three KPIs in relation to EUs. In addition, all five KPIs do not specify performance expectations, or include targets, benchmarks or timeframes for achievements. Nor do they indicate the extent to which ASIC’s efforts have contributed to achieving outcomes.75

2.45 Given that an enhanced Commonwealth performance framework will come into effect on 1 July 2015, there is an opportunity for ASIC to develop more appropriate performance measures and to report on the extent to which EUs support ASIC in achieving regulatory outcomes. A key first step for ASIC is to include targets, benchmarks and/or timeframes in KPIs, and to provide meaningful information to key stakeholders on the effectiveness of EUs in achieving desired regulatory outcomes.

External reporting on EUs

2.46 ASIC reports externally on its enforcement activities through two main publications: its annual report and its half-yearly enforcement outcomes publications. In addition, EUs are published on the EU register on ASIC’s website and through ASIC issuing of a media release with each EU.

2.47 In its 2013–14 Annual Report, ASIC reported that it had achieved 596 enforcement ‘outcomes’,76 including criminal and civil litigation, administrative action and EUs.77 As in previous years, the annual report also referred to specific examples of EUs. ASIC’s enforcement outcomes publications78 report on the number and detail of enforcement outcomes achieved, and provide information on ASIC’s views about certain conduct and the resulting enforcement outcome.

2.48 Neither the annual report nor the enforcement outcomes publications report on post-EU results (for example, the results of independent expert reports or whether promisors have complied with their obligations under an EU). The reports do not provide stakeholders with sufficient information about the outcomes achieved by these activities. ASIC has advised that it will include additional commentary on EUs commencing in its 2014–15 Annual Report. This will address a Senate Economics References Committee recommendation that ASIC include in its annual report additional commentary on: ASIC’s activities related to monitoring compliance with EUs; and how the undertakings have led to improved compliance with the law and encouraged a culture of compliance.79

2.49 To enable a better understanding of the extent to which EUs contribute to ASIC achieving its compliance objectives, it should also develop, and report against, appropriate performance measures that assist management to monitor the effectiveness of EUs in addressing non-compliance. ASIC should also periodically assess the extent to which EUs are contributing to improved levels of voluntary compliance. Possible sources of information for such an assessment include complaints data, community satisfaction surveys and surveys of regulated entities (to identify the effect of EUs on their awareness of, and willingness to comply with, relevant obligations).

Recommendation No.1

2.50 To assess the effectiveness of enforceable undertakings as an appropriate regulatory tool and their contribution to ASIC achieving its compliance objectives, the ANAO recommends that ASIC:

- develops appropriate performance measures to monitor the effectiveness of enforceable undertakings in addressing non-compliance, and regularly reports against these measures; and

- periodically assesses, and reports on, the effectiveness of enforceable undertakings in contributing to improved levels of voluntary compliance.

ASIC response: