Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Early Years Quality Fund

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the establishment, implementation and operation of the Early Years Quality Fund against the requirements of the Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Act 2013 and the Commonwealth grants administration framework.

Summary

Introduction

1. Quality early childhood education and care offers a wide range of benefits to Australian families. The benefits accruing from higher quality care include assisting children in establishing foundations for learning and preparation for subsequent schooling, and assisting parents who wish to remain in or re-enter the workforce. Many parents choose to send their children to formal care provided by a licenced early childhood education and care service—most commonly long day care, or family day care. There are over 6000 long day child care centres nationally run by small and large for-profit and not-for-profit organisations.

2. Significant reforms have occurred since 2009 in the Australian early childhood education and care sector following agreement by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in that year to the National Partnership on the National Quality Agenda for Early Childhood Education and Care. A key element of this agreement was the development of the National Quality Framework (NQF) which replaced the various licensing and quality assurance processes that had previously existed in each state and territory. The NQF also introduced minimum staff to child ratios and worker qualification requirements. In agreeing to the reforms and in establishing a shared vision1 for the sector, COAG recognised that there were significant workforce supply, recruitment and retention issues and that in order to achieve its vision, steps would need to be taken to strengthen the early childhood education and care workforce.

3. Reflecting on the potential impact of the reforms associated with the national quality agenda, the 2011 Productivity Commission report into the Early Childhood Development Workforce noted that the reforms would significantly increase the demand for workers2 and that supply was likely to respond slowly. The Commission suggested that proposed timeframes for reform, which expected full implementation by 1 January 2014, were optimistic. Further, the Commission observed that the reform program was likely to be expensive for both governments and parents, as increased staff numbers, and the higher wages—anticipated in response to the increase in demand—would drive up service costs. At the time the then government was considering its reform directions, the union representing some elements of the workforce, United Voice, was also advocating for a range of improvements in pay and conditions in the sector, and approached the government with a proposal seeking $1.4 billion for a workforce compact3, similar to that provided for the aged care4 sector.

4. To progress reforms and respond to the broader wage pressures then evident, the Australian Government committed $300 million5 (on 19 March 2013) to establish the Early Years Quality Fund (EYQF) with the intended purpose of providing grants to long day care providers in order to supplement wage increases against an agreed wage schedule for child care workers for a period of two years.6 The grants were to be made available to providers on a first-in first-served basis and an advisory board comprising individuals7 from the sector was established to provide advice during the implementation and design phases of the fund.8

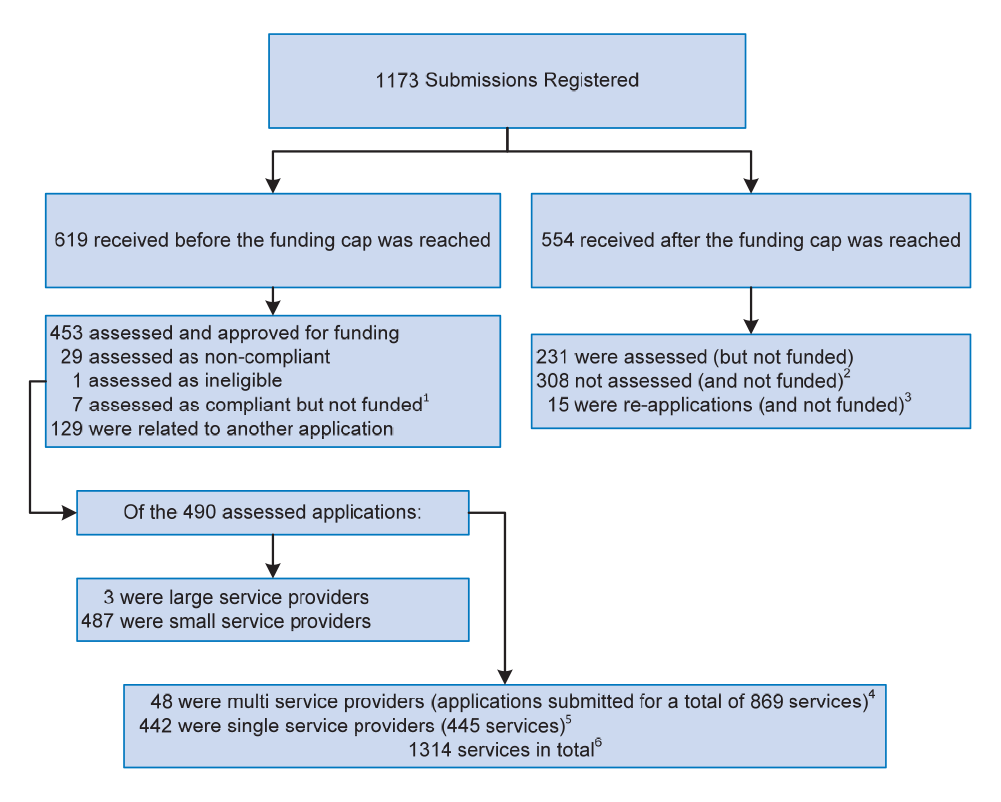

Parliamentary interest and consideration

5. The then government also determined that it would use a Special Account to establish the fund and on 30 May 2013, the Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Bill 2013 (the Bill) was introduced into Parliament. Reflecting the level of public interest in the early childhood education and care sector, the Bill attracted significant stakeholder attention. A large number of submissions to the associated inquiries focused on the wage disparity that was expected to arise, as only a proportion of the early childhood education and care sector would be eligible to receive funding. Concerns were raised with respect to the amount of funds available—$300 million over two years was considered insufficient by stakeholders to provide wage increases for all long day care educators and questions were raised about the impact on wages and resourcing when funding ceased. The proposed first-in first-served approach to awarding grants also drew concern from small providers and sector representative bodies who considered that the approach risked locking out smaller providers from funding as they did not have the resources of larger providers to quickly submit applications to the fund. In his second reading speech to the Bill the then Minister9 acknowledged that the funding would not provide an increase for all child care workers and noted there was more to be done within the sector to attract and retain qualified, respected educators.

6. The Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Act 2013 came into effect on 1 July 2013 with the object of improving quality outcomes for children in early childhood education and care services, by enhancing professionalism in the sector, including through improved attraction and retention of a skilled and professional workforce. The Special Account’s use was restricted to remuneration and other employment related costs and expenses. The account was credited with $135 million on commencement (1 July 2013), with the remaining $165 million to be credited on 1 July 2014. Funding was to be made available to eligible employers in the form of a grant.

Commonwealth grants framework

7. The provision of grants is a means commonly used by the Australian Government to collaborate with third parties in the delivery of services in support of policy objectives. At the time of the design and implementation of the EYQF, the government’s policy requirements and expectations in relation to grants administration were set out in the Commonwealth Grants Guidelines (CGGs)10, which aimed to promote fair and equitable access to grant opportunities.11 The CGGs included several mandatory requirements in relation to decision making by Ministers and reporting, as well as a range of better practice principles to guide government entities in their approach to grants administration. Further, since 2002, the ANAO has also published several editions of its Better Practice Guide on Grants Administration to assist entities in their administration of grants.12

EYQF grants

8. In agreeing to the EYQF, the then government sought to achieve outcomes quickly, setting a date of 1 July 2013 for the disbursement of the grants. This provided a little over three months for the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR, the department) to put in place all the necessary arrangements to implement the program, including conducting the grants assessment process. The government also adopted (as noted in paragraph 4) a demand-driven, first-in first-served approach for the allocation of grants as it considered this would be more likely to meet its timeframes. Under the approach, eligible applications would be processed in the order received and accepted for funding until the funding cap of $300 million was reached. The CGGs allowed for a number of different approaches to awarding grants including through demand-driven processes under which applications that satisfy stated eligibility criteria receive funding, up to the limit of available appropriations.

9. The government had initially decided that the best way to promote equitable access to the EYQF was to require grant applications at the individual service level rather than at the provider level, in recognition of the fact that there was wide divergence in provider types, ranging from single operators or small providers through to large multi-site service providers. Following a recommendation from the EYQF advisory board, the Minister decided that applications should be on a provider basis and that each service included in an application would be assessed individually. The allocation of funding was also influenced by provider size, with small providers (115 services) allocated a pool of $150 million and large providers (16+ services) allocated the remaining $150 million, also following advice from the advisory board.

10. Access to the EYQF was through an email application process using forms provided on the department’s website. To apply for funding, applicants were required to download and complete application forms and lodge them with the department by email in accordance with the EYQF guidelines. Applications opened on Tuesday 23 July 2013. The department registered a total of 1173 submissions from early childhood education and care providers, with a total of 453 applications being approved for funding from the EYQF.13 To receive the proposed funding, successful providers then needed to take steps to meet the conditions in the offer including putting in place or varying enterprise agreements to reflect the agreed EYQF wage schedule. In late August 2013, 44 providers had met the conditions of offer, and funding agreements were progressed for 16 of these providers (15 small and 1 large) prior to the 2013 Federal election. These 16 agreements provided for the payment of grants totalling $137 million.

Review of the Early Years Quality Fund

11. Following the 2013 Federal election, the new government reviewed the EYQF and decided to replace it with a new professional development program for child care educators, using uncommitted funds from the EYQF.14 The new program is directed towards assisting educators in long day care services to meet the qualification requirements under the National Quality Framework (NQF) and improving practice to ensure quality outcomes for children.

12. In light of these developments, funding agreements for the 16 providers were renegotiated with funding levels payable from the EYQF reduced. As at 30 June 2014, ten months after the original funding agreements were signed, a total of $62.5 million had been paid to the 16 providers. Of the $62.5 million, $51.3 million was for wages, $4.9 million for on-costs and $6.3 million for professional development. Conditional funding offers for the remaining applications (made in August 2013) were revoked on 11 October 2013.

Request for review by the Auditor-General

13. The government’s review raised a number of concerns about the manner in which the EYQF had been implemented. Following the release of the review on 10 December 2013, Mr Alex Hawke MP wrote in December 2013 to the Auditor-General requesting that an audit of the EYQF be considered. The Auditor-General agreed that in light of the matters that had been raised, a performance audit would be conducted. The audit commenced in March 2014.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

14. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the establishment, implementation and operation of the EYQF against the requirements of the Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Act 2013 and the Commonwealth grants administration framework.

15. To conclude against the audit objective, the high level criteria included whether the program planning and implementation complied with the legal framework, appropriately considered risks and was consistent with the EYQF policy intent, and the grant selection processes were undertaken in an equitable and transparent way consistent with relevant legislation and the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines.

16. The EYQF was implemented by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and, following the 2013 Federal election, the Department of Education. For ease of reading, this report refers to DEEWR, unless otherwise noted. Under the Administrative Arrangements Order promulgated on 23 December 2014, the Department of Education became the Department of Education and Training, and early childhood programs were transferred to the Department of Social Services (DSS).15 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the Department of Finance were involved in the development of the EYQF and were also included in the audit.

Overall conclusion

17. The Early Years Quality Fund (EYQF) was created to assist in the attraction and retention of skilled and professional child care educators. In particular, the EYQF was intended to allow for increased wage rates for child care workers without these costs flowing on to families. The level of funding available, which was estimated to only cover around 30 per cent of all long day care workers, meant that there would be significant competition for available grants and the program would most likely be oversubscribed. In the event, the $300 million funding cap was reached less than 13 hours after the application process commenced.

18. Successful implementation of policy initiatives requires early, informed and systematic consideration of implementation issues. The design of the EYQF policy contained inherent risks and it was foreseeable that these risks—particularly the funding constraints, the first-in first-served approach and the short timeframes—would affect access to the program and its ultimate success. While decisions on policy are a matter for government, departments are expected to provide frank, comprehensive and timely advice16 to Ministers on both policy design and implementation risks as part of the policy development process. This role was made somewhat more challenging for this program because many of the key elements of the EYQF policy were developed by advisers in the offices of the Prime Minister and Finance Minister in negotiation with the key stakeholder representing child care workers. The elements of the program were then settled through correspondence by key Ministers, rather than through the more conventional Cabinet processes. Advice was given to government at various stages in the design of the policy measure from several different departments. However, the development of the measure had some momentum and the advice provided by departments gained little traction. Nevertheless, there were gaps in departmental advice on a number of significant matters at different times. These included the inherent risk in the use of a demand-driven grants application process and, at later stages, the accuracy of the proposed wage schedule and the potential impact on smaller child care providers of several of the advisory board recommendations.

19. Following the then government’s decision to adopt the EYQF policy, DEEWR became responsible for the implementation of the program. The department was experienced in program implementation and promptly established arrangements to manage the grant process to meet the short timeframes set by the government for the commencement of the program. To some extent the development of key policy elements prior to any significant involvement of the department presented challenges to successful implementation, although in the event, key risks evident in the design of the policy were compounded by inadequacies in the department’s subsequent administration of the EYQF.

20. Facilitating equitable access to the program by applicants was a significant risk to be managed throughout the program’s implementation, given the funds allocated by government were substantially less than required to cover the whole long day care sector. For the estimated 6000 long day care providers that were potential program applicants, accessibility to EYQF grants was also affected by limited consultation and public information about the EYQF grant process. While communication with the sector was initially intended to be managed by the EYQF advisory board, in practice the board’s ability to inform the sector was constrained by delays in its establishment. The board also resolved to amend its charter to emphasise its advisory role rather than its representation role. In this context it considered that it would have a limited role in communicating with the sector, although it agreed to publish post meeting communiques to provide a broad description of the decisions made at board meetings. The department’s own advice to the sector was very limited. Combined with the short timeframes set by the then government—two working days between the guidelines being released and the program applications opening—communication was not conducive to a first-in first-served environment, where applicants needed to be poised to make business decisions and act quickly when applications opened.

21. The department’s system for processing applications needed particular attention to preserve equity of access in the management of the first-in first-served process. The email based system adopted by the department was not fit for purpose and did not fully maintain the first-in order of applications. Complexity and inconsistency within the grant guidelines also presented difficulties; applicants did not always follow the instructions in the guidelines and did not always submit complete applications. After identifying problems with the applications, the department varied the assessment process at several points while it was underway and also repeated a large number of assessments.17

22. Overall, while the department set about to achieve the timeframes expected by the then government, it did not demonstrate a disciplined approach to implementation that satisfied the requirements of the program and the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs). As a result, EYQF processes and procedures were not as well developed as they should have been and there were risks that could have been better managed in the registration, application and approval processes, in the development of funding agreements, and in the management of stakeholder expectations. Further, significant decisions—made during the grant assessment process—were not fully considered or documented, which reduced transparency in relation to key assessment and funding decisions.

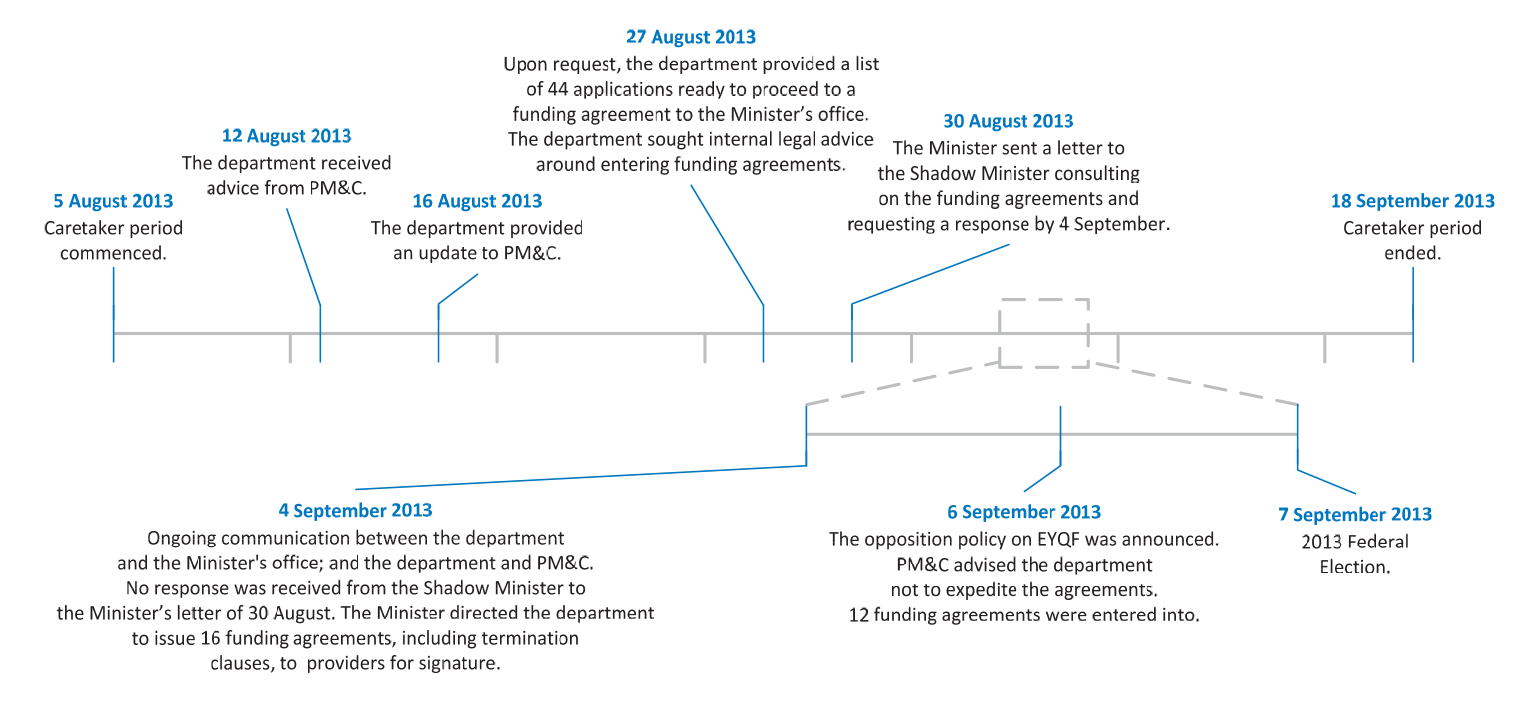

23. At the completion of the grant assessment process, 453 grants (contained within approximately 580 submissions) were approved covering approximately 1309 child care services, and almost 24 000 employees. This represented around 30 per cent of long day care staff and 20 per cent of services. There were approximately 590 submissions not approved for grant funding. Noting that 554 submissions were received from small providers after the funding cap was reached. By close of business 6 September 2013, the day prior to the Federal election, funding agreements had been sent to 1 large provider, Goodstart Early Learning (for $132 million), and 15 small providers (for a total of $5 million) covering 11 710 employees. Subsequently, program changes have resulted in the 16 agreements being either varied or terminated. As at 30 June 2014, $62.5 million had been paid under EYQF.

24. This audit report draws attention to the risks departments face in implementing grant programs, particularly in circumstances where requirements are largely determined by Ministers and their offices, and short timeframes are provided in which to develop and implement arrangements. Nevertheless, departments still have an important role in clearly drawing the attention of Ministers to implementation risks so as to reduce the likelihood of downstream problems affecting service delivery or equity of access to programs. Such advice is particularly important in programs like EYQF where funding was capped and risks of oversubscription were recognised. Key lessons arising from the implementation of the EYQF program include the importance of providing: frank, comprehensive and timely advice to Ministers in relation to implementation risks and opportunities for mitigating these risks where possible; keeping stakeholders informed of developments, including when programs reach full capacity; and ensuring that in demand-driven grant programs, the program guidelines are followed to ensure, as far as possible, equity of access by applicants to available funds. A key step to achieving success in implementing policy on time, budget and to government’s expectations is to give consideration to implementation as a fundamental part of all stages of policy development.18

25. The audit has made one recommendation, observing that the EYQF program has been terminated and replaced with an alternative professional development program for child care educators. That said, the matters discussed in paragraph 24, together with the recommendation, are of relevance to other Commonwealth entities and are intended to inform the design and implementation of future programs.

Key findings by chapter

Chapter 2 – Development of the Early Years Quality Fund

26. Providing well founded policy advice is a core role for the Australian Public Service. A policy initiative is more likely to achieve its intended outcomes when the question of how the policy is to be implemented has been an integral part of the policy design. Where implementation considerations do not receive sufficient and early attention, experience shows that problems are more likely to arise during subsequent delivery of the policy.19 While the EYQF was a product of negotiations with the union representing child care workers, it was preceded by broader considerations around the potential impacts of the National Quality Framework (NQF) reforms. These earlier considerations were informed by the initial development of a child care strategy by DEEWR, but early in 2013 this strategy was overtaken by policy being developed by Ministers’ advisers in the Finance, Treasurer’s and Prime Minister’s Offices and culminated in the child care workforce strategy. The strategy was significant in that it identified the key policy parameters of the EYQF, including the first-in first-served approach to grants, and the need for providers to comply with the NQF and have an enterprise agreement in place.

27. Advice on the policy under negotiation was sought from central agencies (the Departments of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Treasury and Finance) as it developed. Early in the policy development stage, central agencies provided joint advice on the policy to their respective Ministers highlighting key issues—including cost, scope, eligibility and timing—for consideration prior to any decisions being taken. This advice proposed alternative longer term options which aligned more closely with the existing Australian Government support to the sector and which were considered less likely to have a distortionary effect. The briefing was comprehensive in many respects and recommended among other things, that a smaller wage increase be provided to all long day care workers, rather than a large increase to a relatively small sub-set of workers. Although the briefing did not include any advice or caution in relation to the use of a first-in first-served approach, the briefing commented on the implications of restricting the EYQF to a small number of providers.

28. As the department that would have responsibility for implementation of the EYQF, DEEWR’s approach to the provision of advice was variable. After providing initial advice to the then government on options to progress reforms in the child care sector in 2012 and early in 2013, the department’s role was largely limited to contributing to advice being prepared by central agencies until being requested by the Prime Minister’s Office to prepare correspondence for the Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth, seeking policy authority from the Prime Minister for the EYQF. In addition to preparing the draft correspondence, a department would generally be expected to advise its Minister, including in respect of any significant risks to the policy design or implementation, and opportunities to mitigate those risks in the event the government determined to proceed with the proposal. Although the department held concerns around some aspects of the proposal at this time, including the first-in first-served approach to grants, the department elected not to provide the Minister with any accompanying advice on the EYQF proposal as by this stage, the department held the view that the government had largely determined the approach it intended to take.

Chapter 3 – Implementation of the Early Years Quality Fund Program

29. Successful program implementation relies on the identification and management of key risks. Facilitating equitable access to the EYQF by applicants was one significant risk that needed to be managed throughout the program’s implementation. For the estimated 6000 long day care providers that were potential program applicants, accessibility to EYQF grants was reduced by limited consultation and public information about the EYQF grant process. Communication with the sector was initially intended to be managed by the EYQF advisory board. However, the board’s ability to inform the sector was constrained by delays in the establishment of the board and consequent delays in the meeting schedule. At its first meeting in June 2013, the board also resolved to amend its charter to emphasise its advisory role rather than its representation role. In this context it considered that it would have a limited role in communicating with the sector, although it agreed to publish post meeting communiques to provide a broad description of the decisions made at board meetings. The department’s own advice to the sector was very limited. The department was aware that the lack of consultation was a concern for some stakeholders and it should have put in place actions to remedy the situation. The communication approach, combined with the complexity of the guidelines and the short timeframes set by the then government (two working days between the guidelines being released and the program applications opening), was not conducive to a first-in first-served environment, where applicants needed to be poised to make business decisions and act quickly when applications opened.

30. Significant risks to program accessibility also arose in the development of the program guidelines and in particular, errors in the EYQF wage schedule. These errors included the omission of a number of employee classifications set out in the award, which affected the amount of grant funding allocated to some applications. As a result, the department could not confirm the accuracy of the requested, and subsequently approved, funding amounts. Further, although the department was aware of stakeholder concerns with respect to program access for smaller providers (reported during the Parliamentary inquiries), it did not draw to the Minister’s attention the disparity created by the advisory board’s recommendation to split funding equally into two pools for large and small providers. In effect, this decision meant that the smaller providers, which represented 81 per cent of services and 77 per cent of child care places, would have access to only 50 per cent of the funding.

Chapter 4 – Grant Selection Process

31. EYQF grants were to be allocated on a demand-driven, first-in first-served basis. To support equitable access to the EYQF, the department needed to adopt an approach which accurately captured the receipt time of each application and allowed for the efficient processing of applications. The system needed to be designed to manage a large number of potential applications in a short period of time. Potentially, up to 6000 Child Care Benefit approved long day care services could have applied, although ultimately 1173 submissions were received. Following consideration of several options, the department chose to proceed with an email based system, mainly due to timing.

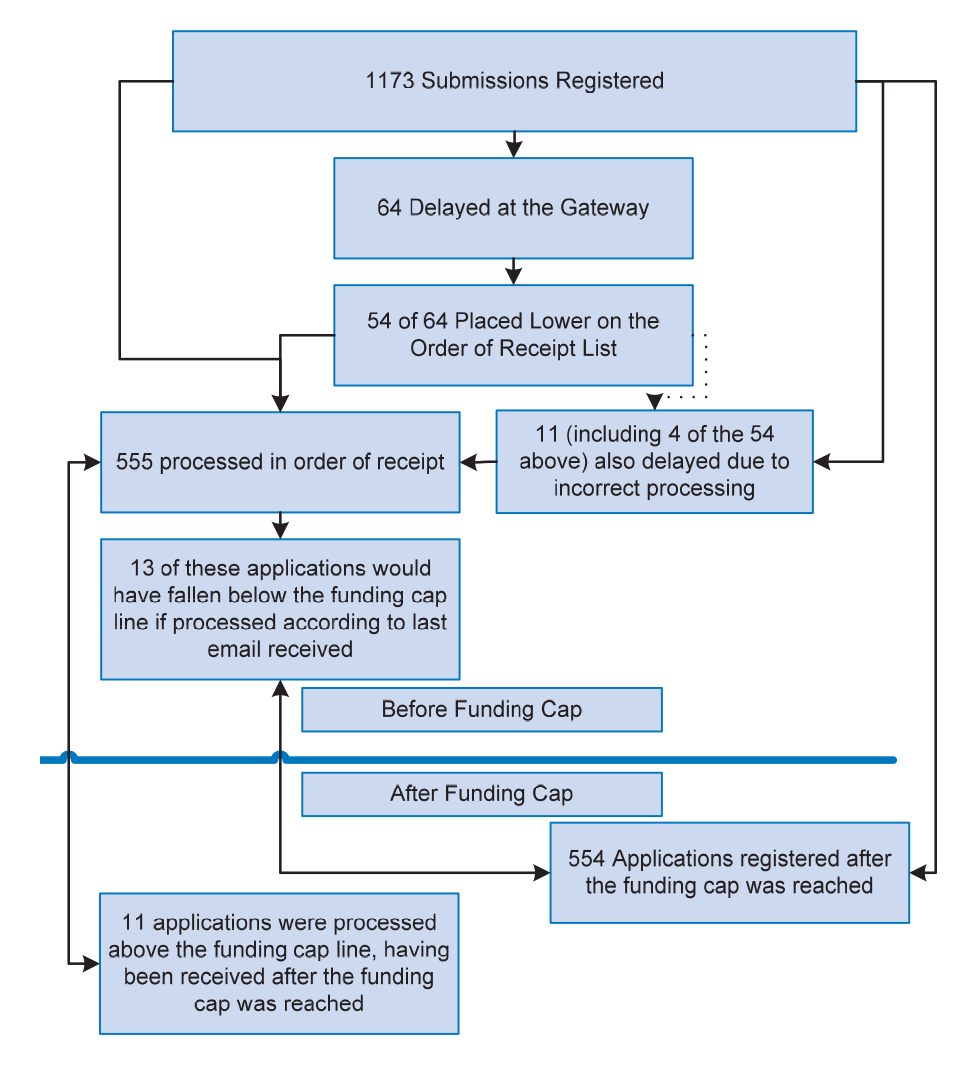

32. It was foreseeable that an email system might result in technical problems. During the application process there were differences between the time recorded at the department’s email gateway and the time of receipt of applications in the EYQF inbox. There were 64 applications delayed at the gateway, with the most significant time difference between an email being received at the gateway and released to the EYQF inbox being nearly two hours, affecting the placement of that application on the time receipt list by 238 places. Other complexities also arose, including the processing of applications sent in more than one email due to email size limits and applicants making amendments to applications and resubmitting either full or part applications (11 resubmitted applications were approved even though they were submitted after other applications had been excluded due to the funding cap being reached) within the time allowed. As a consequence, this affected the delivery of EYQF in accordance with the guidelines to the extent that a number of applications were not processed on a first-in first-served basis.

33. The department’s approach to assessing grants was not uniformly followed or documented. The CGGs in place at the time required that entity staff apply sound processes and conduct granting activities in a manner that provides for the equitable treatment of all applicants. In the course of undertaking the assessments, DEEWR waived elements of the eligibility criteria. Not all of these amendments to the grant criteria were documented and applicants were not advised of the changes. Additionally, assessors did not consistently apply the revised criteria. While there may be instances where it is necessary to waive or amend criteria during a grant process20, in the context of a program with a high risk of over-subscription, greater emphasis should have been placed on adhering to the grants criteria set out in the published guidelines and ensuring that the assessment process was clear, appropriately followed and documented.

34. The pressure on the department to process a large number of applications over a short time period required complete and accurate records to be kept. Assessment records for more than half of the services assessed within the EYQF’s $300 million funding cap were not kept. Other assessment records were inaccurate, inconsistent and overwritten to the extent that no record of the initial assessment in its entirety has been maintained by the department.

Chapter 5 – Finalisation of the Funding Process

35. Successful applicants were advised promptly about the outcome of the EYQF after the funding decisions were made. However, the advice to the majority of unsuccessful applicants and those that were not assessed due to the funding cap being reached, was delayed, as the then Minister’s office had requested that this information not be released. Some unsuccessful and all non-assessed applicants waited upwards of 11 weeks to be advised in writing of the final outcome of the assessment process. Other unsuccessful applicants received letters of advice from the department detailing reasons for the decision around two weeks after the funding decision was made. However, the advice in the letters regarding applications assessed as non-compliant unreasonably raised applicants expectations to the extent these applicants were inappropriately informed to re-apply for funding when none was actually available. Re-submitted applications were received from 15 applicants who acted on this advice.

36. Following the grant assessments, 453 applications were deemed to have been eligible and were offered funding agreements subject to the applicants meeting certain conditions. Ultimately, only 16 funding agreements were finalised before the program was terminated. The finalisation of these agreements occurred one day before the 2013 Federal election during the caretaker period and included one with the largest provider, Goodstart Early Learning which accounted for $132 million. The department’s approach to selecting the funding agreements to be finalised was not recorded but it subsequently advised the ANAO that it focused on finalising these 16 agreements as they were the most advanced at that point. In finalising the agreements the Minister, consistent with the caretaker conventions, corresponded with the relevant Opposition spokesperson21, prior to the agreements being finalised. No response was received and the caretaker Minister directed the department to proceed with issuing the funding agreements requesting the inclusion of termination clauses.

Summary of entity responses

37. The proposed audit report was provided to the (then) Department of Education22 and extracts were provided to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), the Department of Finance, United Voice, the Chair of the advisory board and Goodstart Early Learning. The Department of Education and Training requested and received approval from the ANAO to provide a copy of the draft report to the Department of Social Services as part of the transfer of responsibility for child care programs under the Administrative Arrangements Order promulgated on 23 December 2014.

38. Formal responses were received from the Department of Education and Training, and PM&C. Feedback was also received from the Department of Finance, United Voice, Goodstart Early Learning and the Chair of the advisory board. Summary responses to the audit (where provided) are reproduced below and formal responses are included at Appendix 1.

Department of Education and Training

39. The Department of Education and Training is strongly committed to assisting the early childhood education and care sector attract and retain a skilled and professional workforce.

40. As observed by the ANAO, the EYQF program was terminated in December 2013 and replaced with an alternative professional development programme for child care educators in the long day care sector. At the time of responding, 5 038 long day care services were offered funding under that programme to assist educators up skill qualifications and access professional development activities to assist in meeting the qualifications requirements of the National Quality Framework.

41. The ANAO acknowledges in its report DEEWR’s experience in program implementation and the prompt establishment of arrangements to manage the grant process, further noting the challenges imposed by key elements of the policy being made external to the department and the exceptionally tight implementation timeframes set by government.

42. The audit has identified several areas throughout the implementation process that could have benefitted from further development. The Department is committed to continuous improvement and will incorporate key lessons from these findings to inform the design and implementation of future programmes.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

43. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) considers that the audit report provides a balanced account of the Department’s involvement in the EYQF.

44. PM&C notes the audit report’s conclusions and agrees that while decisions on policy are a matter for government, departments should provide frank, comprehensive and timely advice to Ministers. Further, good Cabinet processes are essential to ensure strategic and coordinated policy solutions to Australia’s national challenges, and to support the implementation of the Government’s priorities.

Recommendation

The EYQF program has been terminated and replaced with an alternative professional development program for child care educators. That said, the key lessons arising from implementing the EYQF—including the importance of departments providing frank, comprehensive and timely advice to Ministers in relation to implementation risks and opportunities to mitigate these risks where possible—together with the recommendation below, are relevant to other Commonwealth entities and are intended to inform the design and implementation of future programs.

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 4.59 |

To enhance the equity, transparency and accountability of future grant programs, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Education and Training:

Department of Education and Training Response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides background information on the Early Years Quality Fund. It also outlines the audit approach including its objective, criteria and methodology.

Background

1.1 Many Australian parents choose to send their children to formal care provided by a licenced early childhood education and care service—most commonly long day care, or family day care. There are recognised benefits which accrue from higher quality child care including assistance to children in establishing foundations for learning and preparation for subsequent schooling, and assistance to parents who wish to remain in or re-enter the workforce. However, the cost of quality child care can affect parental decisions around workforce participation and the Australian Government Assistant Minister for Education has observed that ‘affordable child care is considered the biggest barrier to workforce participation for women, which in turn impacts on everything from the household budget to the national economy.’23

1.2 The long day care sector, which cares for more than 500 000 children each year is diverse, comprised of large and small profit and not-for-profit organisations providing services in more than 6000 centres across Australia. The largest provider of services is Goodstart Early Learning which operates 644 centres nationally, caring for more than 72 500 children. In recognition of the diversity of the sector and the large number of children receiving services, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed in 2009 to significant reforms in the Australian early childhood education and care sector. These reforms set out in the National Quality Framework (NQF), a key component of the National Partnership on the National Quality Agenda for Early Childhood Education and Care, replaced the various licensing and quality assurance processes that had previously existed in each state and territory. The NQF also introduced minimum staff to child ratios and worker qualification requirements. In agreeing to the reforms and in outlining a shared vision24 for the sector, COAG recognised that there were significant supply, recruitment and retention issues that existed and that in order to achieve its vision, steps would need to be taken to strengthen the child care workforce.

1.3 The Productivity Commission in its report Early Childhood Development Workforce, reflected on both the size of the sector and the potential impact of the COAG reforms. The Commission noted that the reforms would significantly increase the demand for workers—about 15 000 more workers were likely to be required than would otherwise be the case—and the average level of workers’ qualifications would need to increase.25 The Commission also suggested that supply was likely to respond slowly to the growing demand, and that the timeframes for reform which expected full implementation by 1 January 2014 were optimistic. The reform program was likely to be expensive for both governments and parents, as increased staff numbers, and the higher wages—anticipated in response to the increase in demand—would drive up child care costs for families.

1.4 At the time the then government was considering reform directions, the trade union representing some elements of the child care workforce, United Voice, was advocating26 for improvements in pay and conditions in the sector and approached the government with a proposal seeking $1.4 billion in 201213, (increasing annually to $2.0 billion per year by 2020–21) for a workforce compact similar in form to the Aged Care Compact.27

The Early Years Quality Fund

1.5 To progress reforms and respond to the broader wage pressures then evident, the Prime Minister, the Hon Julia Gillard MP, announced on 19 March 2013, that the government would provide $314 million28 over five years to boost the quality of early childhood education and support workplace reform. Of this funding, $300 million over two years would be used to establish the Early Years Quality Fund (EYQF) with the intended purpose of providing grants to long day care providers in order to supplement wage increases of $3 per hour for Certificate III qualified educators. Proportionally adjusted wage increases were to be made available for other child care workers and diploma and degree qualified educators. The grants were to be made available to providers on a first-in first-served or demand-driven basis.

1.6 A further $8.2 million over three years was provided for the administration of the fund by the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and the establishment of an advisory board to oversee the fund’s operations. The advisory board comprising individuals from the sector was established to provide advice during the implementation and design phases of the fund.29 The government also provided $6.2 million over four years to establish a Pay Equity Unit in the Fair Work Commission to assist with data and research collection, and provide specialist pay equity information with an initial focus on the early childhood education and care sector.

Parliamentary interest and consideration

1.7 The then government determined it would use a Special Account30 to establish the EYQF and on 30 May 2013, the Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Bill 2013 (the Bill) was introduced to Parliament. The Bill attracted significant stakeholder attention reflecting the level of public interest in the early childhood education and care sector. A large number of submissions31 to the two Parliamentary inquiries which ensued focused on the wage disparity that was expected to arise as only a proportion of the early childhood education and care sector would be eligible to receive EYQF funds. Concerns were raised with respect to the amount of funds allocated—$300 million over two years was considered insufficient to provide wage increases for all long day care educators—and the impact on the workforce when funding ceased. The first-in first-served approach also drew concern from small providers and sector representative bodies who considered that the approach would lock out smaller providers as they did not have the resources of larger providers to apply for funds quickly. The Bill was passed without amendment by both Houses of Parliament on 28 June 2013. In his second reading speech on the matter, the then Minister32 noted there was more to be done within the sector to ‘attract and retain qualified, respected educators who are being remunerated in a way that shows their value to the Australian society and the future of Australian children.’

1.8 The Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Act 2013 came into effect on 1 July 2013, with the object of improving quality outcomes for children in early childhood education and care services, by enhancing professionalism in the sector, including through improved attraction and retention of a skilled and professional workforce. The Special Account’s use was restricted to remuneration and other employment related costs and expenses. The account was credited with $135 million on commencement (1 July 2013), with the remaining $165 million to be credited on 1 July 2014.

1.9 The provision of grants is a means commonly used by the Australian Government to collaborate with third parties in the delivery of services in support of policy objectives. The grants policy framework that was in place at the time that the funding rounds were completed included the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) and the Commonwealth Grants Guidelines (CGGs). The framework changed after the funding round was completed, with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) taking effect from 1 July 2014 and the issuing of the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) to replace the CGGs.

1.10 The CGGs included several mandatory requirements in relation to decision making by Ministers and reporting, as well as a range of better practice principles to guide government entities in their approach to grants administration. These same requirements are reflected in the CGRGs. Since 2002, the ANAO has also published several editions of its Better Practice Guide on Grants Administration to assist entities in their administration of grants.33

Early Years Quality Fund grants

1.11 In agreeing to the EYQF, the then government sought to achieve outcomes quickly, setting a date for the disbursement of the grants of 1 July 2013. As a result, DEEWR had just over three months to put in place all the necessary arrangements to implement the program, including conducting the grants assessment process. As noted in paragraph 1.5, the government also adopted a demand-driven, first-in first-served approach for the allocation of grants as it considered this would be more likely to meet its timeframes. Under the approach, eligible applications would be processed in the order received and accepted for funding until the funding cap of $300 million was reached. The CGGs allowed for a number of different approaches to awarding grants, including through demand-driven processes under which applications that satisfy stated eligibility criteria receive funding, up to the limit of available appropriations.

1.12 Access to the EYQF was through an email application process using forms provided on the department’s website. To apply for funding, applicants were required to download and complete application forms and lodge them with the department by email in accordance with the EYQF guidelines. Applications opened on Tuesday 23 July 2013. The department registered a total of 1173 submissions from early childhood education and care providers, with a total of 453 applications being approved for funding from the EYQF. To receive the proposed funding, successful providers then needed to take steps to meet the conditions in the offer including putting in place or varying enterprise agreements to reflect the agreed EYQF wage schedule. In late August 2013, 44 providers had met the conditions of offer, and funding agreements were progressed for 16 of these prior to the 2013 Federal election. These 16 agreements provided for the payment of grants totalling $137 million.

Review of the Early Years Quality Fund

1.13 On coming into office in September 2013, the new government commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers Australia to conduct a Ministerial review of the EYQF. In response to the review report34, the government replaced the EYQF with a new professional development program for child care educators. The new program is directed towards assisting educators in long day care services to meet the qualification requirements of the NQF and improving practice to ensure quality outcomes for children.

1.14 EYQF funding agreements were renegotiated with funding levels payable to the 16 providers reduced. As at 30 June 2014, ten months after the original funding agreements were signed, a total of $62.5 million was paid to these 16 providers of which $51.3 million was for wages, $4.9 million for on-costs and $6.3 million for professional development. Conditional funding offers for the remaining applications (made in August 2013) were revoked on 11 October 2013.

1.15 The key events in the development of the EYQF are summarised in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Early Years Quality Fund timeline

|

Date |

Action |

|

19 March 2013 |

Letter from the Minister for School Education, Early Childhood & Youth to the Prime Minister seeking authority to establish the EYQF. Letter from the Prime Minister to the Minister granting authority for the EYQF. Department issues FAQ guidance on its website. EYQF details posted by United Voice to its Big Steps Campaign Facebook page. |

|

24 May 2013 |

EYQF advisory board appointed. |

|

30 May 2013 |

EYQF Special Account Bill 2013 introduced to Parliament. |

|

6 June 2013 |

1st advisory board meeting. |

|

14 June 2013 |

2nd advisory board meeting. |

|

17 June 2013 |

Senate Inquiry into the Bill reports. |

|

19 June 2013 |

House of Representatives Inquiry into the Bill reports. 3rd advisory board meeting. |

|

27-28 June 2013 |

4th advisory board meeting. |

|

28 June 2013 |

EYQF Special Account Bill 2013 passed by both Houses of Parliament. |

|

19 July 2013 |

Program guidelines issued on DEEWR website and advice distributed to long day care service providers. |

|

23 July 2013 |

Application process for EYQF opened at 11am AEST. Large provider funding pool cap reached by 1.30pm AEST Small provider funding pool cap reached by 12 midnight AEST.a |

|

27 July 2013 |

List of providers receiving funding finalised for approval. |

|

Early August 2013 |

Conditional offers of funding made for 453 successful applications. |

|

6 September 2013 |

Funding agreements executed with 12 providers (4 others were signed by the Commonwealth and subsequently considered executed). |

|

7 September 2013 |

Federal election. |

|

10 December 2013 |

Review report released. The Long Day Care Professional Development Programme announced. |

Source: ANAO.

Note a: These times represent the point at which the final applications were received to reach the cap.

Request for review by the Auditor-General

1.16 The government’s review raised a number of concerns about the manner in which the EYQF had been implemented. Following the release of the review on 10 December 2013, Mr Alex Hawke MP wrote in December 2013 to the Auditor-General requesting that an audit of the EYQF be considered. The Auditor-General agreed that in light of the matters that had been raised, a performance audit would be conducted. The audit commenced in March 2014.

Audit objective

1.17 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the establishment, implementation and operation of the EYQF against the requirements of the Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Act 2013 and the Commonwealth grants administration framework.

Scope

1.18 The ANAO focused on the key program elements of the EYQF, from the establishment of the fund and the design and conduct of the funding round, and its ongoing operation and management. The main focus of the audit was on the Department of Education and Training (formally DEEWR) and that department’s management of the EYQF. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Department of Finance were also included in the scope of the audit in relation to their roles in the policy development stages.

Criteria

1.19 To conclude against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- program planning and implementation complied with the legal framework, appropriately considered risks and was consistent with the EYQF policy intent; and

- grants administration was undertaken in an equitable and transparent way, consistent with the program objectives and facilitated applications from eligible bodies.

Audit approach

1.20 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed departmental files and program documentation;

- interviewed and/or received written input from departmental staff and relevant stakeholders, including successful and unsuccessful grant applicants and members of the advisory board; and

- examined a sample of 759 grant submissions. This included a detailed examination of the grant assessments for more than 490 distinct applications which were approved for funding, assessed as compliant, as non-compliant or as ineligible.

1.21 The EYQF was implemented by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and, following the 2013 Federal election, the Department of Education. For ease of reading, this report refers to DEEWR, unless otherwise noted. Under the Administrative Arrangements Order promulgated on 23 December 2014, the Department of Education became the Department of Education and Training, and early childhood programs were transferred to the Department of Social Services (DSS).35 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the Department of Finance were involved in the development of the EYQF and were also included in the audit.

1.22 The audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $696 474.

Audit report structure

1.23 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.2 below.

Table 1.2: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Chapter 2 Establishment of the Early Years Quality Fund |

This chapter examines the policy development process and establishment of the $300 million Early Years Quality Fund and the provision of advice to government at various stages. |

|

Chapter 3 Implementation of the Early Years Quality Fund |

This chapter considers the department’s approach to implementing the Early Years Quality Fund with a focus on engagement with the sector and management of key risks to program access. |

|

Chapter 4 Access to the Program and Assessment Outcomes |

This chapter examines the department’s processes for submitting and assessing applications, the recommendation to the delegate and the final funding decision. |

|

Chapter 5 Finalisation of the Early Years Quality Fund |

This chapter examines the advice the department provided to applicants after the funding decision was made, the processes followed in developing the funding agreements during the caretaker period, and subsequent variations to funding agreements. |

Source: ANAO

2. Establishment of the Early Years Quality Fund

This chapter examines the policy development process and establishment of the $300 million Early Years Quality Fund and the provision of advice to government at various stages.

Introduction

2.1 While decisions on policy are a matter for government, and generally decisions are made through a Cabinet process, departments should advise on both policy design and implementation risks as part of the policy development process. Commonwealth entities are expected to provide frank, comprehensive and timely advice36 to Ministers to help ensure that government decisions are appropriately supported and well informed. Successful implementation of policy initiatives requires early, informed and systematic consideration of implementation issues.

2.2 The ANAO examined the development of the EYQF policy with a focus on the advice that was provided to Ministers and the extent to which implementation was considered in policy development.

Initial policy development to support the early childhood workforce

2.3 The EYQF was created to assist in the attraction and retention of skilled and professional child care educators through providing increased wage rates for child care workers without these costs flowing on to families. Although the EYQF policy arose from negotiations between stakeholders and the government, it was preceded by broader policy considerations and departmental advice in relation to issues highlighted in the Productivity Commission’s 2011 report into the Early Childhood Workforce.37 The government considered a number of options in preparing its response to the Productivity Commission report. As part of this consideration DEEWR prepared several new policy proposals in anticipation of a cabinet submission to be based on a broader strategy known as ‘Child Care Next Steps’. One of the proposed options involved a compact with the child care sector to address wage matters in return for restraining fee increases. At that time (late 2012), the department was working on a number of options including assumptions which ranged from $195 million over three years for a one per cent wage increase (or $6 per week for an average full time educator), through to $978 million over three years for a five per cent wage increase, which would equate to $30 per week.

2.4 The Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) requested the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) to provide a summary of processes that would be required for:

- An application to Fair Work Australia for an equal remuneration order—the advice recognised that minimum wage setting was the responsibility of industrial tribunals, which are separate from government;

- A low-paid bargaining authorisation, which would require multiple employers to bargain for a multi-enterprise agreement; and

- A workforce compact between government, union and business representatives.

2.5 PM&C also advised that there were implementation risks and difficulties with each of the options set out at paragraph 2.4. In particular, a workforce compact was identified as a difficult option for the early childhood sector as the Commonwealth provided very little direct funding to employers. Most government funding in the sector is provided directly to families38 through the Child Care Rebate (CCR) and Child Care Benefit (CCB), which cumulatively total around $5 billion per annum.

Developing the child care workforce strategy

2.6 Governments generally have several policy development options open to them on significant issues, including the development of Cabinet submissions for consideration by Cabinet or, less frequently, by correspondence between Ministers and the Prime Minister. The advantage of a Cabinet submission is that it can provide for structured consideration of risks, timelines and resourcing from a range of perspectives, namely those of Cabinet Ministers and their departments. In the case of the EYQF, the government chose not to proceed through a Cabinet process. Instead, the policy was largely developed between the offices of the Finance Minister, Treasurer and the Prime Minister, as well as the offices of the Minister for Education, the Minister for Early Childhood and Child Care, and the Parliamentary Secretary for School Education and Workplace Relations. The policy was subsequently settled through correspondence between the Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth and the Prime Minister.

2.7 Through the early stages of January 2013, DEEWR prepared advice for an anticipated announcement of the Child Care Next Steps strategy. However, later in January 2013, the development of the strategy was overtaken by negotiations between United Voice and Ministers’ advisers. While this development was driven by advisers, staff in each of the Ministers’ offices were in contact with officials in the relevant departments to seek advice or information as required.

2.8 The key aspects of the design of the EYQF were provided in a series of internal papers arising from the negotiations (in February 2013). These papers represented a hybrid approach of options previously considered in the Ministers’ offices to address the United Voice child care campaign and comprised a proposal for a Child Care Workforce Strategy (including Short Term Assistance for Child Care Sector: Expanded Child Care Flexibility Trial). The child care workforce strategy (CCWS) was significant in that it identified the key policy parameters for the EYQF including the provision of grants on a ‘first-in first-served’ basis until the available funding was committed.39

2.9 The strategy also envisaged that around 30 per cent of the long day care sector would be involved in a compact between government and employers through wage supplementation to be delivered through a grant program to eligible providers. The key features of the proposal were:

- establishment of an Early Years Quality Fund of $300 million, over two years, available from 2013–14; and the formation of an EYQF advisory board, consisting of employee and employer representatives to oversee the operation of the fund;

- access to grants was to be restricted to long day care providers who were approved for the purposes of the Child Care Benefit;

- applications were to be subject to a number of conditions including;

- a practical commitment to the implementation of the National Quality Framework (NQF), including a detailed plan to meet the workforce qualification requirements commencing in 2014, and evidence of support for the NQF by a majority of permanent employees;

- approval of an enterprise agreement containing the approved EYQF wage schedule, which set out the hourly wage increase corresponding to each employment classification, with at least a $3 per hour increase from 1 July 2013 for an entry level educator holding Certificate III;

- an agreement to fee restraint, with fee increases limited to actual running cost increases (and no fee increases resulting from the increase in wages arising from the operation of the EYQF); and

- a preparedness to meet specified reporting requirements.

Provision of advice by relevant departments

2.10 Advice on the policy under negotiation was sought from the central agencies, the Departments of Finance, Treasury and PM&C, as it developed. As the entity that would have responsibility for implementation of the EYQF, DEEWR’s involvement in the provision of advice in the initial stages was largely limited to contributing to advice being prepared by central agencies.

2.11 Early in 2013 central agencies provided joint advice to their respective Ministers highlighting key issues—including cost, scope, eligibility and timing—for consideration prior to any decisions being taken. In particular the three central agencies recommended that Ministers note:

(i) the significant fiscal and implementation risks, particularly against the treatment of the SACS40 equal remuneration case and the Budget backdrop; and

(ii) if proceeding with a CCWS, to agree to the proposed Compact providing wage increases to all workers in long day care centres broadly consistent with the increases payable to workers covered by the Aged Care Compact or the SACS decision.

2.12 A key observation in the advice was that providing wage supplementation directly to employers would change the nature of the government’s involvement with the sector. As a result, the brief identified a number of key issues for consideration. A summary of these key issues is below.

The scope and cost of the proposed compact

2.13 The proposal to provide a wage increase to a sub-set of the long day care workforce was considered to risk criticism from the majority of the long day care workforce who would not receive the proposed increase. Employees covered by an enterprise agreement were already likely to be being paid above award rates. This proposal could therefore be seen to benefit 14 500 workers who may already be in receipt of above award rates, while providing no increase to 50 000 workers who were not.

2.14 The (then) proposed $5 per hour41 wage supplementation would represent an increase of approximately 2530 per cent above (then) current hourly rates.42 While the amount of the increase was consistent with the total increase awarded by the Fair Work Commission (FWC) to SACS workers, SACS increases were being phased in over eight years. The proposed increases were also considerably larger than those provided under the Aged Care Workforce Compact of $0.46 per hour, of which the government was funding $0.18 per hour in the first year.

2.15 Central agencies observed that the provision of Commonwealth supplementation for increases in excess of 25 per cent of current wages ahead of any consideration of a wage case by the FWC (which had not been prepared at that time), would raise expectations of continued Commonwealth supplementation for all child care centres after any decision by the FWC. The estimated cost of this would be in the order of $800 to $900 million per annum. In the view of the central agencies, a lower wage rise over a larger number of providers could have assisted with mitigating this risk.

2.16 Restricting the proposed compact to a relatively small number of providers was considered likely to have a significant market distortion effect, with those not eligible for wage assistance likely to experience increased difficulty in attracting and retaining qualified staff. This would put upward pressure on fees for those providers, which would in turn flow through to increased costs for parents.

Timing

2.17 The development of a wage compact between the government, participating child care providers and United Voice was noted to be very challenging to implement and make payments from 1 August 2013. Before negotiations on a compact could commence, the scope of the compact would need to be determined and if it was restricted to a sub-set of long day care providers, they would need to be identified through an application and selection process. For this reason the brief noted that 1 January 2014 may have been a more achievable start date.

Alternative options

2.18 The brief also presented alternative longer-term options for the Minister’s consideration that central agencies felt would more closely align with the Commonwealth’s existing support for child care and be less distortionary to the market. These included:

- Introduction of a loading (approximately 5 per cent) on to the Child Care Benefit to help break the nexus between wage cases and wage supplementation. Providers would be able to increase fees to support wage and training requirements but with an offset to parents targeted at low to medium income earners.

- Increase the level of the Child Care Rebate - Providers would be able to increase fees to support wage and training requirements but without any targeting to parents on low to medium incomes, although it was noted that restriction of Child Care Rebate increases to long day care only would be more difficult to justify and may also introduce market distortions.

Costing assumptions

2.19 The Department of Finance in consultation with DEEWR43 provided the Finance Minister’s office with an indicative costing assessment for the EYQF which set out several additional assumptions, including that the advisory board would need to be established and meet immediately as it would be responsible for the implementation plan. The most significant of the assumptions set out in the Finance costing was that applications would be based on a first-in first-served basis, which was a feature identified in policy papers prepared by ministerial advisers, as noted in paragraph 2.8. Finance has advised that the assumption was made on the basis of the timetable established by the policy, which called for grant payments to be available and commence from 1 July 2013.

Approach to grant allocation

2.20 The CGG’s indicate that the key factors which should be considered when determining the type of granting approach include the objective of the granting activity; the likely number and type of application; the nature of the grants; the value of the grants; and the need for timeliness and cost-effectiveness in the decision-making process while maintaining rigour, equity and accountability.44 Additionally, the CGGs state that competitive, merit-based selection processes should be used to allocate grants, unless specifically agreed otherwise by a Minister, chief executive or delegate. As discussed at paragraph 2.8, the determination of the first-in first-served grant selection process was not well documented in the development of EYQF. In this context, a first-in first-served process was essentially a demand-driven granting activity under the CGGs, where applications that satisfied the stated eligibility criteria received funding, up to the limit of available appropriations and subject to revision, suspension or abolition of the granting activity.45

2.21 There are advantages and disadvantages to both merit-based and demand-driven granting activities. Drawbacks of the latter approach include that it is likely to result in applications being assessed in relative isolation, potentially making it more difficult to ensure there are consistent processes, standards and interpretations of the grant guidelines applied in the decision-making process.46 A merit-based approach offers advantages such as a more transparent and reliable method of selecting successful applicants.

2.22 The nature of the granting activity will affect the content of the program guidelines. While demand-driven granting activities can be an efficient means of providing intended recipients with funding, the potential for oversubscription of the EYQF was very high. Accordingly, an assessment of its implications for the eligibility criteria and how the program would be managed when the available funds were exhausted was desirably required in the policy design phase of the program. Such an assessment could have been used to appropriately inform the government on matters such as whether or not a demand-driven program was the most appropriate or a maximum grant limit should be applied. As a department experienced in implementation, DEEWR was well positioned to consider the risks and benefits of different approaches. In the early policy development stage, the department did contribute advice in relation to the workplace relations aspects of the policy. Although, as the agency that would be responsible for implementation, the department did not and was not requested, to provide advice in relation to the demand-driven nature of the grant activity in briefings prepared by central agencies. There was a further opportunity for DEEWR to address implementation matters, when developing correspondence for the Minister on the EYQF proposal which would form the policy proposal that received authority from the Prime Minister in March 2013. Subsequent to the decision, the department did provide advice on implementation, but in essence this was too late in the piece to result in any change to the government’s approach.

Policy approval and announcement

2.23 Once the agreement had been reached between Ministers around the policy parameters, DEEWR was requested by the Prime Minister’s Office to prepare correspondence for the Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth, seeking policy authority from the Prime Minister for the EYQF. In addition to preparing the draft correspondence, a department would generally be expected to advise its Minister, including in respect of any significant risks to the policy design or implementation, and opportunities to mitigate those risks in the event the government determined to proceed with the proposal. Although the department held concerns around some aspects of the proposal at this time, including around the meaning of the first-in first-served approach to grants, the department elected not to provide the Minister with any accompanying advice on the EYQF proposal.

2.24 The Prime Minister agreed to the package of measures set out in the Minister’s letter on 19 March 201347, thereby providing policy authority for the EYQF. The Prime Minister’s letter also requested an implementation plan be provided (to the Prime Minister) by 8 April 2013, which was to include timeframes for the establishment of the EYQF advisory board, and development of its advice ahead of a 1 July 2013 implementation date and advice on how the EYQF would be accessed by a range of providers.

Additional advice to Ministers

2.25 From an implementation perspective DEEWR regarded the first-in first-served process (which had been agreed by government), as problematic, recognising the challenges associated with this approach. The department provided a brief to the Minister for School Education Early Childhood and Youth in early April 2013 setting out alternative options for implementation, which included:

- moving from first-in first-served to allocate funding by jurisdiction and size of service;

- prioritising applications on the basis of quality of application;

- advice that if on-costs were to be included in the grants, these should be on a sliding scale; and

- a suggestion that grant funding should only be available for qualified early childhood education and care workers who have direct contact with children (i.e. exclude administrative and support staff that might otherwise be covered by the enterprise agreement).

2.26 In comments provided to the department in response to the April 2013 briefing to the Minister for Education, advisers in the Prime Minister’s Office did not accept the alternative options outlined above. The response from the advisers indicated that with respect to prioritising applications on the basis of quality, the department was ‘over thinking’ the process. In relation to the inclusion of on-costs, the Prime Minister’s Office indicated that it had already determined that on-costs were to be included; but that the Education Minister’s office would test a sliding scale and a 13 per cent cap on on-costs with United Voice, and assess the likely response of Goodstart Early Learning.48 In the event, resolving the issues around the payment of on-costs was referred to the advisory board for consideration. The rate of on-costs was finalised along with other changes recommended by the advisory board (see paragraph 3.14) when the guidelines were formally approved.

2.27 In July 2013, one week before opening calls for grants, the department again suggested informally via email to the Minister’s advisers that despite the timeframes implications, conducting a comparative merit-based assessment process would produce a better policy outcome and would be considered by the sector as being more equitable and transparent than a first-in first-served process. There was no direct response to this suggestion.

Inherent risks

2.28 There were inherent risks that derived from the fact that DEEWR did not provide advice on program implementation during the policy development process for EYQF. DEEWR’s key opportunities to influence the development of EYQF policy prior to its agreement were twofold: firstly the input into advice provided by the central agencies; and secondly in preparing correspondence for its Minister, however, the department elected not to provide any implementation advice at either point. Consequently there was little consideration during the early stages of EYQF establishment of how the program would be implemented. Given that the policy was already agreed and timeframes for establishment of the program were tight, the concerns that were later raised by DEEWR, did not gain traction with ministerial advisers and were not accommodated before the program guidelines were released. The development of the program guidelines is discussed in more detail in chapter 3.

Conclusion

2.29 Policy development takes a number of different forms. Some policies can be developed and implemented with long lead times while others must be developed and implemented quickly. A key element of all policy development is the need to give early, informed and systematic consideration of implementation issues. Involvement of implementing entities and the provision of advice by those entities at appropriate stages of the policy development process helps reduce subsequent implementation risks. The advantage of a Cabinet submission is that it can provide for structured consideration of risks, timelines and resourcing from a range of perspectives, namely those of Cabinet Ministers and their departments. However, in this instance, the government elected to manage the proposal through correspondence between Ministers and the Prime Minister.

2.30 Important details around the operation of the grant selection process were decided by government as part of the policy announced on 19 March 2013, including that the grants were to be made available to providers on a demand-driven first-in first-served basis, an advisory board would be appointed, and that payments from the fund would commence with effect from 1 July 2013. It is open to governments to adopt approaches of its choice, and in view of the timeframes of the EYQF, demand-driven granting activities had the potential to be an effective means of distributing funding to child care providers. While DEEWR raised with the Minister (and later with the Minister’s advisers) that a merit-based process could be more appropriate (than first-in first-served), this advice was provided too late to effect a change in the policy design, as the policy decision had already been taken by government.

3. Implementation of the Early Years Quality Fund

This chapter considers the department’s approach to implementing the Early Years Quality Fund with a focus on engagement with the sector and management of key risks to program access.

Introduction

3.1 The implementation of Australian Government policy initiatives is one of the key responsibilities of government entities. In recent years there has been an increasing focus on, and a community expectation of, sound policy implementation and the seamless delivery of government policies.49 Successful implementation requires early, informed and systematic consideration of issues as they arise throughout implementation.

3.2 Following the government’s decision to proceed with the EYQF, DEEWR was responsible for developing and implementing the administrative arrangements for the program. As noted in paragraph 2.28, the design of the EYQF policy contained inherent risks (the funding constraints, the first-in first-served approach and the short timeframes). Implementing the program would require a concerted effort on DEEWR’s part to meet government’s timing expectations and ensure equity of access to the program.50 The EYQF advisory board also had an important role in the program’s implementation, through the provision of advice to the department on how grants would be accessed by a range of providers and direction in the development of the program guidelines.

3.3 As EYQF funding was provided on a first-in first-served basis, it was critical that applicants could easily understand the details of the program, how to apply and how their application would be assessed against other applications. This would avoid potential costs to applicants associated with developing and submitting applications that were not eligible, had little chance of success51 or were received too late—after EYQF funding was fully committed.

3.4 The ANAO examined the department’s approach to planning for EYQF grants focusing on the department’s engagement with stakeholders including the advisory board and the management of key risks to program access which arose in the development of the program guidelines.