Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Climate Change Programs

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of specific climate change programs by the departments of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and Resources, Energy and Tourism. In undertaking this audit, particular emphasis was given to the implementation of good administrative practice and the extent to which the program objectives were being met. The audit followed four lines of inquiry:

- development of program objectives and assessment of program risks;

- assessment and approval of competitive grant applications;

- assessment and approval of rebate applications; and

- measurement and reporting of program outcomes.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Government has indicated that climate change, caused by the emission of anthropogenic greenhouse gases, is an important issue that has the potential to cause significant damage to our environment, industries, people and infrastructure. The Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE) has stated that some degree of change to our climate will be unavoidable because of the level of gases already accumulated in the atmosphere. As a consequence, there will be a greater likelihood of more frequent and more extreme weather events including heat waves, storms, cyclones and bushfires; a continued decline in rainfall in southern Australia; and higher temperatures leading to decreases in water supplies.1

Australian Government response to climate change

2. In response to the challenge posed by climate change, successive governments have used grant and rebate programs as a vehicle for reducing national emissions and to stimulate more renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, geo-thermal and hydro technologies. Investment in research and development and the commercialisation of other new technologies, such as carbon capture and storage, has also been a feature of the policies of the present and previous governments.

3. The current Australian Government has prioritised actions on climate change and has committed more than $15 billion towards climate change initiatives. The Government's actions on climate change fall under three main categories, referred to as the Three Pillars Strategy. These are:

- reducing emissions;

- adapting to unavoidable climate change; and

- helping to shape a global solution.

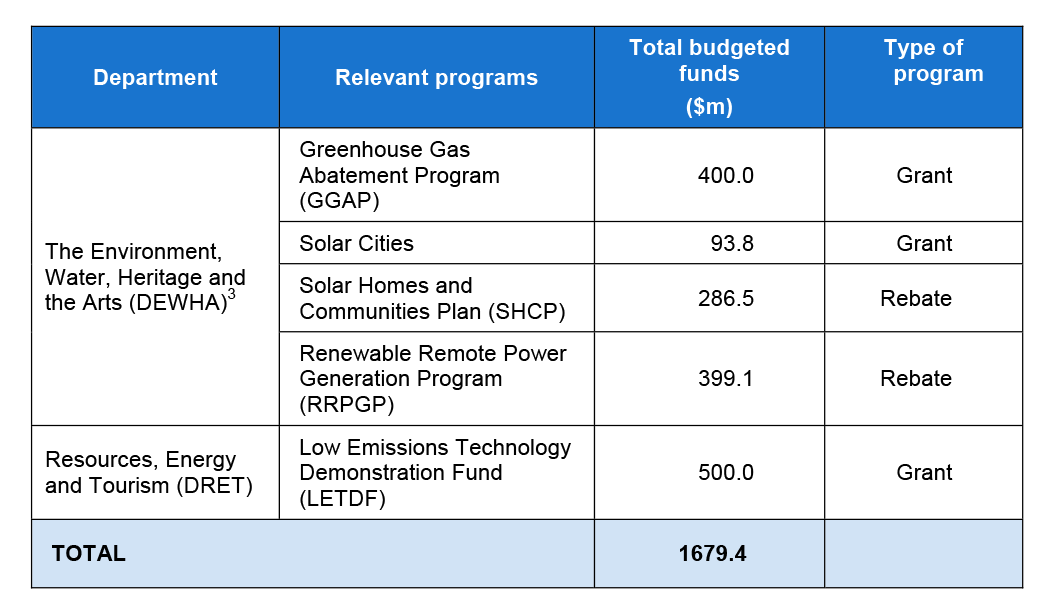

4. The ANAO examined a sample of three grant programs and two rebate schemes, valued at $1.7 billion, which were designed to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and to promote or demonstrate renewable energy technologies. These programs were chosen as they were significant, high profile measures from the suite of 62 Australian Government climate change programs in place at the time. Table S 1 outlines the five climate change mitigation and industry development programs examined as part of this audit, the funds appropriated and the agencies that were responsible for administering the programs.2

Table S 1 Climate change mitigation and industry support programs examined as part of the audit

Source: Budget funds based on Annual Reports from DEWHA and DRET.

5. Applications for these programs have closed and future funding rounds are not anticipated. Apart from SHCP and RRPGP, no funding has been allocated in the forward estimates to cover additional funding commitments. Ongoing funding commitments will be progressively met under existing contractual arrangements specified in the deeds of agreement for each program. This is likely to extend the Commonwealth's financial commitment to up to 2020.

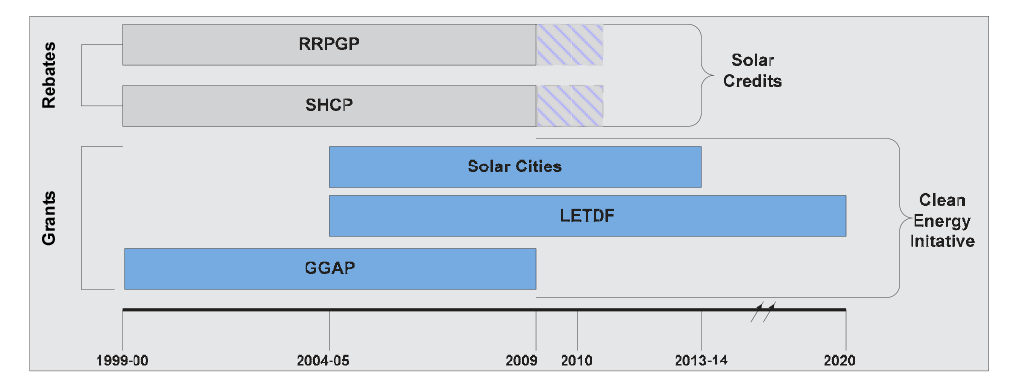

6. SHCP, Solar Cities and RRPGP are now being administered by DCCEE and LETDF by DRET.4 SHCP and RRPGP have been replaced by the Solar Credits initiative, which is also being administered by DCCEE. In addition, a $3.9 billion Energy Efficient Homes Package announced in the 2009 10 Budget provides incentives for households to improve their energy efficiency through installing insulation and solar hot water systems. These programs have some similarities with the SHCP in that demand forecasting is critical to the effective management of appropriations. Assistance for renewable energy and clean coal technology will now be provided through the Clean Energy Initiative, which was announced in the May 2009 Budget. Figure S 1 sets out the timeline of rebate and grant programs examined and their transition to new program initiatives.

Figure S 1 Timeline of rebate and grant programs

Source: ANAO based on data from DEWHA and DRET.

7. The findings from this audit have been designed to assist in the implementation of these and future programs as well as convey lessons that may have application to other grant programs in the departments concerned.

Projects funded under grant programs

8. Funding under the competitive grant programs has been for projects such as large scale demonstration projects supporting new technologies to reduce GHG emissions. Grants have ranged from $1 million to $100 million and recipients have tended to be large private, industrial or resource companies, or consortia of governments, industry and community organisations. The following are examples of projects and the programs under which they are funded:

- reductions in emissions of synthetic GHG gases from refrigeration systems in supermarkets (GGAP);

- retro-fitting a set of new technologies to an existing coal-fired power station in Queensland to trial carbon capture and storage (LETDF); and

- Adelaide Solar City (Solar Cities program) to establish and trial innovative technologies and practices, including the concentrated uptake of solar power, energy efficiency and smart metering technologies.

Rebate schemes

9. The SHCP provided rebates of up to $8 000 dollars ($8 per watt up to one kilowatt)5 to homeowners for the installation of solar photovoltaic systems on their principal place of residence, and rebates to community organisations that installed photovoltaic power systems for educational purposes.

10. Funding for RRPGP provided financial support to increase the use of renewable generation in remote parts of Australia that relied on fossil fuel for electricity supply. The program has three main components: Renewable Energy Water Pumping Rebates, Residential and Medium-scale projects and Major projects. Since the start of the program in 2000, over 6 500 small rebates have been paid with the installation of more than 9400 kilowatts of photovoltaic, wind and micro-hydro generation under the Renewable Energy Water Pumping and Residential Medium-scale projects. For major projects, over $52 million has been approved for 31 projects, of which 20 have been completed.6

Previous audit

ANAO Audit Report No.34 2003–04, The Administration of Major Programs

11. Audit Report No.34 2003–04, examined a sample of Australian Government programs, valued at almost $900 million, administered by the then Australian Greenhouse Office (AGO). The report identified administrative weaknesses in the seven programs examined. The absence of quantifiable objectives and targets made it difficult to measure results against program objectives. In addition, the lack of a comprehensive risk assessment exposed some programs to risks that could have been better identified and treated in the early stages. The audit commented that substantial risks remained—particularly in terms of the timely achievement of program objectives. The need for a more consistent and transparent approach to assessing and selecting projects was also highlighted.

Audit objectives and scope

Objective

12. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of specific climate change programs by the departments of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and Resources, Energy and Tourism. In undertaking this audit, particular emphasis was given to the implementation of good administrative practice and the extent to which the program objectives were being met. The audit followed four lines of inquiry:

- development of program objectives and assessment of program risks;

- assessment and approval of competitive grant applications;

- assessment and approval of rebate applications; and

- measurement and reporting of program outcomes.

13. The coordination of Australian, State and Territory climate change programs and the measuring and integrity of reporting of Australia's GHG emissions are examined in Audit Report No 27. Coordination and Reporting of Australia's Climate Change Measures, tabled in conjunction with this report.

Audit scope

14. The audit scope included four programs managed by DEWHA. In March 2010, responsibility for these programs was transferred to DCCEE. These programs included two competitive grant programs and two rebate schemes. One competitive grant program was managed through DRET. The audit focused on the administration of the programs for the following periods:

- round three projects for GGAP (the first two rounds were considered in the 2003–04 audit);

- LETDF and Solar Cities from 2004–05 to 2009; and

- SHCP and RRPGP from 2007–08 (following the review and restructuring of the programs in 2007) to 2009.

Overall conclusion

15. The grant and rebate programs reviewed were designed to reduce GHG emissions and/or support the renewable energy industry. At a total value of $1.7 billion over the life of the programs, successive Australian Governments have invested significant resources in climate change initiatives. Funding under competitive grant programs has been for innovative and high risk projects such as large scale demonstration projects supporting new technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Grants ranged from $1 million to $100 million. In contrast, rebate schemes provided lower value, but a higher volume of assistance to support renewable technologies.

16. Each program had different administrative issues and challenges and the effectiveness of some of these programs was constrained by weaknesses in program implementation and design. The overriding message for the effective management and success of future climate change programs is that greater consideration needs to be given to:

- setting clear and measurable objectives;

- assessing and implementing appropriate risk mitigation strategies;

- applying a rigorous merit based assessment of applications for competitive grants; and

- effective measuring and reporting on performance.

17. The objectives of the five climate change programs were generally broad, with three of the five programs, (Solar Cities, SHCP and RRPGP), having multiple objectives. These three programs had very little specificity in terms of how much was intended to be achieved over the life of the program, making it difficult to target resources and set administrative priorities.

18. The control and management of risks could have been substantially improved. The nature of the programs examined, involving large grants and new or unproven technology, meant that they were inherently high risk. However, where programs had undertaken risk assessments, the treatment options or controls did not always mitigate the risks identified, and many of these risks materialised throughout the course of the programs.

19. The assessment and selection of climate change projects under the LETDF and Solar Cities programs was transparent, with criteria used to assess all proposals. Generally, there was a high degree of rigour and technical expertise applied to the assessment process. However, the assessment and selection process for projects under GGAP was inadequate. Recommended (and subsequently approved) projects for the third funding round failed to meet the Government's guidelines and eligibility criteria, as no recommended project met the specified greenhouse gas abatement threshold. The rigour of the cost–benefit and technical analysis could have also been substantially improved and particularly the advice provided to the then Minister for the Environment.

20. Program achievements against objectives varied for the grant programs and rebate schemes. The high risk, large value grant programs have achieved minimal results to date. Actual achievements for GGAP, the longest running program, were substantially less than originally planned with only 30 per cent of planned emissions abatement being achieved. This underperformance was because of delays in finalising funding agreements and the termination of nine out of the twenty-three approved projects. LETDF and Solar Cities are not sufficiently advanced for any meaningful comments on overall program results to be made to date.

21. For the two rebate schemes, SHCP and RRPGP, demand outstripped available funds–particularly for SHCP. As a consequence, the SHCP has substantially contributed to growth in the up-take of renewable energy in Australia. However, in terms of abatement, this has come at a high unit cost ($447/tonne/CO2e) and at a significant cost to the budget estimated to be $1.053 billion. The abatement achieved by the RRPGP program is also very expensive especially when compared to a possible emissions trading scheme market carbon price closer to $20–$30/tonne/CO2e.

22. Across the five programs examined, performance reporting could have been substantially better in terms of accuracy and consistency. If Parliament is to make informed judgements about what these, (and any future climate change programs) have achieved, reporting by agencies will need to more closely adhere to the annual reporting guidelines. In particular, reporting actual performance in relation to performance targets; and providing narrative discussion and analysis of performance.

23. To be effective, future programs will need to implement the key components of grant administration as outlined in the 2009 Commonwealth Grant Guidelines, particularly in terms of program planning and design and achieving value for public money. This audit has made one recommendation aimed at improving grant administration in DEWHA and could also be taken into account by DCCEE in terms of the ongoing administration of relevant programs. It has also identified a number of lessons that may have application to other grant programs in the departments concerned.

Key findings by chapter

Setting program objectives and assessing program risks (Chapter 2)

Assessing program objectives and program design

24. The objectives of the five climate change programs were directly or indirectly designed to reduce GHG emissions, and/or promote or demonstrate renewable energy technologies. They were generally broad, with three of the five programs, Solar Cities, SHCP and RRPGP having multiple objectives with very little specificity in terms of what was intended to be achieved over the life of the programs. The lack of concise, outcome-orientated objectives made it more difficult to target resources and set administrative priorities because of the uncertainty in relation to the ultimate outcome being sought by government.

25. There were marked differences in the origins of the five programs. Three of the five programs examined (GGAP, SHCP and RRPGP), were introduced in 1999–2000 as part of the then Government's Measures for a Better Environment Package. There was no formal new policy consideration or scrutiny by relevant departments and there was minimal consultation with stakeholders. This increased the risks to the effective delivery of the program and made it difficult for the department to determine whether or not the objectives could be realistically achieved within the envisaged timeframes. In contrast, the origins of the LETDF and Solar Cities programs were in the 2004 Energy White Paper. There was a comprehensive process of policy papers, extensive stakeholder consultation and informal submissions from industry and other groups. It provided a sound foundation for implementing new policy programs.

Assessment and management of program risks

26. Identifying and assessing risks is particularly important for programs involving inherently high risk innovative technologies and high levels of project expenditure. Risk assessments can assist in managing adverse impacts and should be undertaken at the design stage or early in the life of the program, which can assist departments in their capacity to meet program outcomes. Of the five programs examined, only one program, Solar Cities, undertook a risk assessment in the early stages of the program's design and continued to monitor and revise the risk assessment as the program was implemented. Solar Cities risk assessment was included in the 2005 program implementation plan and was imbedded in the program's planning documents and has been updated at multiple stages of the program's implementation. LETDF did not have a risk management plan at the inception of the program in 2004–05. However, a risk assessment was completed in June 2006 and updated annually.

27. As noted in Audit Report No.34 2003 04, Administration of Major Programs, there was no evidence that a comprehensive risk assessment was conducted by the then Australian Greenhouse Office, at the design stage of the GGAP, SHCP (previously PVRP) and RRPGP programs. In subsequent revisions to these programs, DEWHA had undertaken a timely assessment of risk early in the life of the revised programs. However, the treatment of risks during the life of the programs could have been improved. For GGAP, SHCP and RRPGP, the risks identified in the assessment phase materialised during the implementation of the program and constrained program effectiveness. For example with GGAP and RRPGP (major projects), a rigorous assessment process was not followed and for SHCP the unanticipated surge in demand materialised during the implementation of the program from 2007–08.

28. Risk management could also have been strengthened for the measures relating to renewable energy and carbon capture and storage in the 2009–10 Budget. The Clean Energy Initiative supersedes the LETDF and provides funding to support the construction and demonstration of large-scale integrated carbon capture and storage projects ($2.4 billion over nine years) and large-scale solar power stations ($1.5 billion over six years). There was no documentation to support how the Clean Energy Initiative was considered, particularly in terms of agencies' advice on the costs and benefits of the proposal, and the management of risks associated with implementing the program.

29. Consideration of the COAG complementarity principles was a requirement from Ministers for all relevant programs following the Wilkins Review. The principles were designed to guide the direction of government policy (Australian and State Government) and to better integrate Commonwealth, State and Territory climate change program delivery. While the COAG complementarity principles were not explicitly considered in the Clean Energy Initiative's design, documentation from DRET indicates that the principles were subsequently incorporated into the department's risk management planning. The department has recently completed risk management plans for the major constituent programs for the initiative.

Assessment and approval of competitive grants (Chapter 3)

30. The assessment and approval of project proposals is critical to the effective delivery of the Government's climate change initiatives. An effective assessment and selection process is one that is fair, equitable and transparent, and is likely to assist in selecting those projects that best represent value for money in the context of the objectives and outcomes of the programs.

31. The three competitive grant programs (GGAP, LETDF and Solar Cities) reviewed as part of this audit, included a total of 281 applications and 36 approved projects. Total funding for approved projects across the three programs was $550 million. All programs had a sound framework for assessing applications that included published eligibility and merit criteria and assessment and advice by independent technical experts. The quality of applications for LETDF and Solar Cities was higher overall than GGAP. This reflected the preparatory work by departments with stakeholders prior to the rollout of these programs.

32. This audit reviewed the assessment process for the third funding round for GGAP which involved 50 applications. Audit Report No.34 2003–04, noted shortcomings in the assessment of projects for the first two rounds of the GGAP. The third round also had significant shortcomings in the assessment process. In particular, the rigour of the cost benefit and technical analysis could have been substantially improved. None of the shortlisted project proposals recommended by the department could provide the large scale abatement at low cost, and with a high degree of certainty required by the program's guidelines. The three highest ranked (and recommended) projects were technically ineligible as they did not meet the Australian Government's primary criteria for the program. For these three projects, which were subsequently approved by the then Minister, only one project has produced any abatement to date. However, this was less than one third of the threshold specified for the program. The departmental advice to the then Minister for the Environment substantially underestimated the risks and shortcomings of these recommended projects, which should, on the basis of the documentation available at the time, have been apparent at the assessment stage and included in the advice to the Minister.

33. The ANAO reviewed the assessment process for 26 of the 30 applications for LETDF and five expressions of interest and detailed business cases for the Solar Cities program. The assessment processes for both programs, were transparent, with clear criteria used to assess all proposals received. There was also a relatively high degree of rigour and technical expertise applied to the assessment process. However, for LETDF, greater consideration could have been given to the financial viability of proponents, especially in regard to the approved project that was eventually terminated.

34. All three programs (GGAP, LETDF and Solar Cities) had well designed Deeds of Agreement. However, there were substantial delays in negotiating the agreements, subsequent to funding approval. Delays of two years were not uncommon. While there were legitimate reasons for some delays (such as finalising third party funding or development approval for very large projects), it highlights the importance of including careful consideration of implementation timeframes for proposals in advice to Ministers prior to approval. Otherwise, expected program outcomes may be significantly delayed; as has occurred.

Assessment and approval of rebates (Chapter 4)

35. As with the competitive programs, rebate programs need to demonstrate fairness and consistency in the assessment of applications. Rebate programs with fixed appropriations and variable demand can be difficult to manage, particularly where an applicant has an entitlement to a rebate if their application is deemed as eligible. A significant risk for these types of programs is that an unexpected acceleration in demand could exceed the funding limits specified in Budget appropriations.

Solar Homes and Communities Plan

36. The SHCP provided rebates to support the installation of solar photovoltaic systems. The SHCP involved more than 30 000 approved rebates from 2007–08 to 30 June 2009. SHCP had a two stage assessment and approval process. An assessment was made against eligibility and the application was pre-approved, followed by a subsequent rebate payment based on the submission of a valid installation report from an approved installer. In May 2008, an income means test of $100 000 in annual household income was introduced to manage demand. Despite this measure, the number of applications increased from 11 000 in 2007–08 to 121 376 applications in 2008–09. The department established a review process to test compliance with the means test. This was particularly important as no documentation was required to substantiate compliance with the means test. The level of compliance with the means test was found to be 97.6 per cent, giving the department a reasonable level of assurance that the means test was being administered appropriately and that it was largely being met by applicants.

37. More generally, management of the application process for SHCP was challenging for the department, particularly in the period from May 2009. The Government decided to close the program at midnight on 9 June 2009, giving consumers and industry 24 hours notice. Some 4 000 applications arrived in the department on 9 June 2009. At the end of July 2009, approximately 75 000 applications were awaiting pre-approval assessment with some 48 000 applications being received after the cut-off date. The total cost is estimated to be $1.053 billion compared to the original funding for the program of $150 million over five years from 2007–08. An independent analysis commissioned by the department, of a five per cent sample of applications received between 10-30 June 2009, concluded that there was a high degree of eligibility for the applications received on 10 June 2009, with no more than six per cent of applications classed as ineligible.

38. The department managed the substantial difficulties resulting from the surge in the program in a manner that was fair and transparent, and the Minister was briefed on the range of options available at critical points of the process. There is sufficient evidence to indicate that approved applications met the program eligibility criteria. However, the high level of unforseen expenditure put additional pressure on the budget, requiring a substantial increase in administered and departmental resources. This increase eroded the relevance of the department's original Budget forecast and the cap on the number of rebates. It also highlights the critical importance of having an adequate range of controls and strategies in place to manage such large increases in demand. The demand pressures on the department also created delays in payments to approved applicants. In February 2010, the department was still processing rebate installation reports received in November 2009. The department has indicated that additional resources have been allocated to improve the payment schedule.

Renewable Remote Power Generation Program

39. The RRPGP involved rebates to support renewable energy applications in rural and remote areas. From 2007, the rebate scheme involved 1 208 approved rebates valued at $23.1 million and six major projects valued at $11.1 million. RRPGP underwent administrative changes in 2007, with the administration of the industry support and major project sub–programs being managed centrally by DEWHA. The water pumping and residential rebates were to remain with the States and Territories under formal funding agreements with the department, on behalf of the Commonwealth.

40. State and Territory agencies reported against milestones set out in the agreements. An annual report (including an audited financial statement) was required and provided a level of assurance that funds had been spent for their intended purposes. However, there was no formal assurance by the States or Territories that program eligibility guidelines had been met and no information on the number of applications rejected. Given that there were 49 requirements for the residential sub–program alone, there would have been merit in gaining a reasonable level of assurance that the Australian Government's eligibility requirements were being met through the State/Territory approval processes, such as through a certification process. The department has indicated that it is now working with the State/Territory jurisdictions to require them to formally certify that they are acting in compliance with program guidelines.

41. For the RRPGP major projects component, there were no approved guidelines. The proposed guidelines setting out the eligibility criteria to be used to approve funding had been formally rejected by the then Minister for the Environment. Advice from the Minister's Chief of Staff subsequently suggested that the guidelines were satisfactory. While Ministerial approval could reasonably be implied as the guidelines were referenced in briefings, it would have been appropriate for the department to have sought confirmation from, or approval by, the then Minister as the authorised decision maker. The eligibility criteria in the guidelines were also not consistently applied by the department when assessing projects, weakening the integrity of the assessment process. However, payments were made against milestones which gave the Government some control over emerging risks.

Measuring and reporting of progress towards program outcomes (Chapter 5)

42. To determine whether the programs are achieving their intended objectives, agencies need to develop appropriate key performance indicators and monitor the progress of projects. The ANAO examined the extent to which the programs had achieved what was originally intended by the Government.

Measuring against key performance indicators

43. All five programs examined had either key performance indicators or milestones in place that were relevant to the objectives of the program. However, for some programs there was no means of measuring all aspects of the objectives. Two of the five programs, GGAP and LETDF had clear performance targets in place from the start of the programs, whereas the other three programs, Solar Cities, SHCP and RRPGP did not have targets for the life of the programs. Those agencies that had a small number of focused indicators, tended to be better placed to measure and report against these. Measuring performance for Solar Cities (12 indicators) and RRPGP (six indicators), became more complex and problematic with substantial measurement gaps noted, particularly with RRPGP. The lack of a national program database meant that there was no way that RRPGP and to a lesser extent, Solar Cities, could capture and measure program achievements at a national level. With RRPGP, the database took seven years to complete, and was only operational four weeks before the program was terminated by the Government.

44. Overall, the actual achievement of the five programs has been variable. For the programs designed to achieve substantial abatement, such as GGAP, the current revised estimate of achievements fell well short, with 15.5 Mt CO2e estimated over the Kyoto period, compared to the 51.5 Mt CO2e expected. Nine of the 23 approved projects (valued at $44 million) were terminated for reasons such as failure to meet contractual obligations and operational difficulties with project implementation. In some cases, projects were supporting technologies that were not yet commercial or proponents were reliant on approval or agreement by third parties that did not materialise. By linking payments with project milestones, funds actually expended by the Australian Government for terminated projects totalled $1.8 million or 4.1 per cent of the committed funds for these projects.

45. LETDF and Solar Cities are not sufficiently advanced to provide any meaningful data on whether the programs, as a whole, have been delivering against anticipated outcomes. While both programs were intended to have substantial results available in the longer term, delays in finalising funding agreements (and one terminated project for LETDF), will impact on the timing of anticipated outcomes. All three competitive grant programs have been characterised by significant program under spends. GGAP spent only 40 per cent of its original budget allocation over a ten year period. LETDF spent less than five per cent of its budget over a five year period while Solar Cities spent nearly 26 per cent of its original budget allocation over the same period.

46. The rebate schemes, SHCP and RRPGP, have been successful in supporting the photovoltaic (PV) industry. SHCP alone, has supported the installation of over 49 000 PV systems to July 2009. The retail side of the industry has been growing strongly with 1 200 accredited installers in 2009 compared to just 210 in 2006. However, the achievement of these outcomes has come at a relatively high unit cost of abatement ($447/tCO2e) and at a significant cost to the Budget estimated to be $1.053 billion. Total installed capacity of PV in Australia in 2008 was still relatively small; accounting for just 0.2 per cent of total installed electricity capacity.

47. The quality inspections introduced by the department in 2005 were an important quality control mechanism to manage risks as well as providing a level of assurance for the quality of work undertaken by the accredited installers. However, in 2009 the surge in rebates for SHCP and the increased number of installers reduced the number of inspections from the 5 per cent of installed systems to 0.25 per cent. This substantially reduced the level of assurance available to the department and introduced the risk of sub-standard installation at a critical period of record numbers of installations.

48. Performance reporting has been inconsistent and sometimes vague or inaccurate. There is scope for improvements to be made to assist the Government and Parliament in making informed judgments as to the actual achievements resulting from program expenditure.

Summary of agency responses

49. The following comments constitute each agency's summary response to the audit. The full responses are at Appendix 1.

Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency

50. Energy efficiency programs previously delivered by the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) were transferred by Administrative Arrangements Order to the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE) on Monday 8 March 2010. As such, work areas responsible for administering the audited programs have also transferred to DCCEE.

51. DCCEE and DEWHA jointly thank the ANAO for this audit report. Issues raised by the audit are relevant to best practice program administration across agencies and the audit report's conclusions and recommendations have been noted by both agencies.

52. We agree in principle with Recommendation 1, noting that the audited programs have transferred from DEWHA to DCCEE. Across the full suite of programs we administer, both departments are committed to achieving consistent and improved practice in the areas of: identifying and managing risk; assessing and selecting projects; and monitoring of program performance and reporting. Following the changes in responsibilities which accompanied the Machinery of Government changes, both departments are actively examining the best organisational mechanism to achieve this outcome, including a Grants Policy Unit or similar entity.

53. In this light, we welcome the ANAO's audit report as an opportunity to further advance our capacity to deliver timely, effective and efficient programs which help achieve the Government's outcomes.

Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism

54. The Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET) welcomes the ANAO's audit, in particular the recognition of the sound program processes and robust stakeholder consultation undertaken in relation to the administration of the Low Emissions Technology Demonstration Fund.

55. The Department would also like to thank the ANAO for the professional manner in which it carried out the audit and for its open, communicative approach to our staff and management.

Footnotes

1 Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency; Adapting to Climate Change [Internet] Canberra, January 2010, available from <http://www.climatechange.gov.au/en/government/adapt> [accessed 19 March 2010].

2 The management of LETDF was transferred from the Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research to the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism from 1 July 2008. Prior to November 2007, the program was administered by the then Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources.

3 The programs administered by DEWHA were transferred to DCCEE in March 2010.

4 Funding for GGAP has been fully expensed.

5 The original rebate was revised from $2.50 per peak watt in September 2000 to $5.50 per watt. This was then revised down to $4 per watt in May 2003. In May 2007, the rebate was doubled to $8 per watt.

6 Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Annual Report 2008-09.