Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Capital Gains Tax for Individual and Small Business Taxpayers

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of capital gains tax for individual and small business taxpayers.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is the Government’s principal revenue collection agency. In 2013–14, the ATO processed 16.5 million tax returns and collected $321.7 billion in net tax—mostly in income tax from individuals ($163.6 billion) and companies ($67.3 billion).1 Income tax revenue is derived from a number of sources such as wages and salaries, investment income (interest and dividends), and business income. One component of income tax collected by the ATO is capital gains tax (CGT).

2. Australia introduced a CGT system in 1985. It was intended to include capital gains as assessable income, reduce tax avoidance practices and promote appropriate capital investment in Australia.2 Unless specifically excluded, CGT applies to all assets acquired on or after 20 September 1985 and applies to Australian residents’ assets anywhere in the world. Foreign residents can also be subject to CGT in accordance with the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997.3 The most common way to make a capital gain is through the sale of tangible assets such as real property4 or shares. CGT can also apply to intangible assets such as business goodwill and intellectual property. Some common assets that are exempt from CGT include: major personal assets, particularly a taxpayer’s private (main) residence and motor vehicle; and most personal use assets, such as furniture.

3. The ATO collects substantial revenue from CGT, in total and from key categories of taxpayers—individuals, companies and superannuation funds. CGT revenue is, however, volatile and influenced by domestic and international economic conditions, such as the global financial crisis, and local factors such as natural disasters. These types of events can affect people’s financial behaviour and influence real property and stock markets, which are common sources of capital gains and losses. CGT receipts for 2013–14 were reported as $7.2 billion.5

4. The latest available tax statistics (2010–11 to 2012–13) show that most CGT was paid by individuals (58 per cent), with companies contributing around 37 per cent of the estimated total tax payable on capital gains.6 Of CGT paid by companies, most was paid by small business (over 45 per cent in 2011–12), with 36 per cent from large and international businesses in the same year and the remainder from medium-sized businesses (18 per cent).7

5. While the ATO considers that most taxpayers meet their CGT obligations, it has rated the risk of non-compliance with CGT requirements as ‘high’8 for the individual taxpayer and small business market segments. This rating is largely due to the complex law design of CGT, the one-off nature of capital events and an absence of reliable data about those events. The ATO undertakes a range of activities designed to assist people to understand and comply with their taxation obligations, including providing educational material and conducting active compliance work through audits, reviews9 and correspondence.10

Administration of capital gains tax

6. The ATO’s Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line manages the tax and superannuation systems for taxpayers from the small business11, individuals and employers markets. At the beginning of 2014–15, it had 2077 full-time equivalent staff located around Australia, addressing a range of taxation matters affecting those market segments, including CGT.

Previous performance audit

7. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examined the ATO’s administration of CGT compliance in the individuals market segment eight years ago.12 The focus of the audit was the ATO’s administration of compliance by individuals with respect to the two most common CGT events: real property and share disposals. This audit concluded that the ATO’s administration of CGT for that market was effective overall. The audit made seven recommendations aimed at improving the ATO’s administration of CGT for individuals in the areas of: CGT project planning; data management and risk assessment; and compliance planning. The ATO agreed to all recommendations.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of capital gains tax for individual and small business taxpayers.

9. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- management arrangements support the effective administration of CGT for individual and small business taxpayers;

- compliance risks are assessed and a coherent strategy is in place to promote compliance with CGT requirements; and

- compliance activities are appropriate and effective.

10. The ANAO focused on CGT activities undertaken in the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line.13 The audit also includes a review of the implementation status of the seven recommendations from the 2006–07 ANAO audit report.

Overall conclusion

11. Australian taxpayers have been required to include net capital gains14 as part of their assessable income since 1985 when the capital gains tax (CGT) system was introduced. In 2013–14, CGT receipts were around $7.2 billion15, which represented some 2.2 per cent of the $321.7 billion total net tax collected by the ATO.16 Based on the latest ATO estimates, in 2011–12, some 63 per cent of CGT was paid by individual taxpayers, with small business comprising around 14 per cent in that year.

12. The arrangements put in place by the ATO to administer CGT reflect its general approach to taxation administration. The ATO has provided a range of targeted marketing, communication and education activities explaining CGT requirements and encouraging compliance by individual and small business taxpayers, which are the focus of this audit. The ATO has also implemented sound management arrangements and suitable risk management processes to administer CGT for these taxpayers. Nevertheless, CGT presents particular compliance challenges for taxpayers intending to fulfil their tax obligations and administrative challenges for the ATO—essentially related to the one-off nature of capital events, extensive record keeping requirements for taxpayers and reliance on third-party data by the ATO, particularly for compliance activity with individual taxpayers. As a result, CGT has been classified as a high compliance risk for the ATO, requiring effective approaches to risk mitigation and active management oversight to monitor performance.

13. While the ATO’s general approach to the administration of CGT is sound, there has been a heavy reliance on taxpayers’ voluntary disclosures of CGT liabilities in their annual tax returns. Insufficient attention has been given to addressing the limited effectiveness of compliance activities for individual and small business taxpayers that have not met their CGT obligations. As a consequence, there has been a considerable reduction in the revenue raised from specific CGT compliance activities directed at individual and small business taxpayers in recent years. This aspect of CGT administration requires closer consideration by the ATO.

14. In relation to compliance activities, the ATO has programs for CGT that take into account the different elements of the individual and small business taxpayer market segments. CGT compliance activities for individual taxpayers are primarily conducted through correspondence (letters that draw on third-party data), while reviews and audits are conducted for small business taxpayers.17 These active compliance programs raised some $546 million in liabilities from 2011–12 to 2013–1418, of which around 30 per cent ($149 million) has been collected. Further, the liabilities raised and cash collected from these targeted CGT compliance activities are relatively small amounts in comparison to the voluntary disclosure of capital gains. The latest available ATO data indicates that in 2011–12 the estimated total tax payable on capital gains made by individual and small business taxpayers was around $4.3 billion, with around $150 million in liabilities raised and only $46 million (31 per cent) in cash collected from compliance activities conducted in that year.

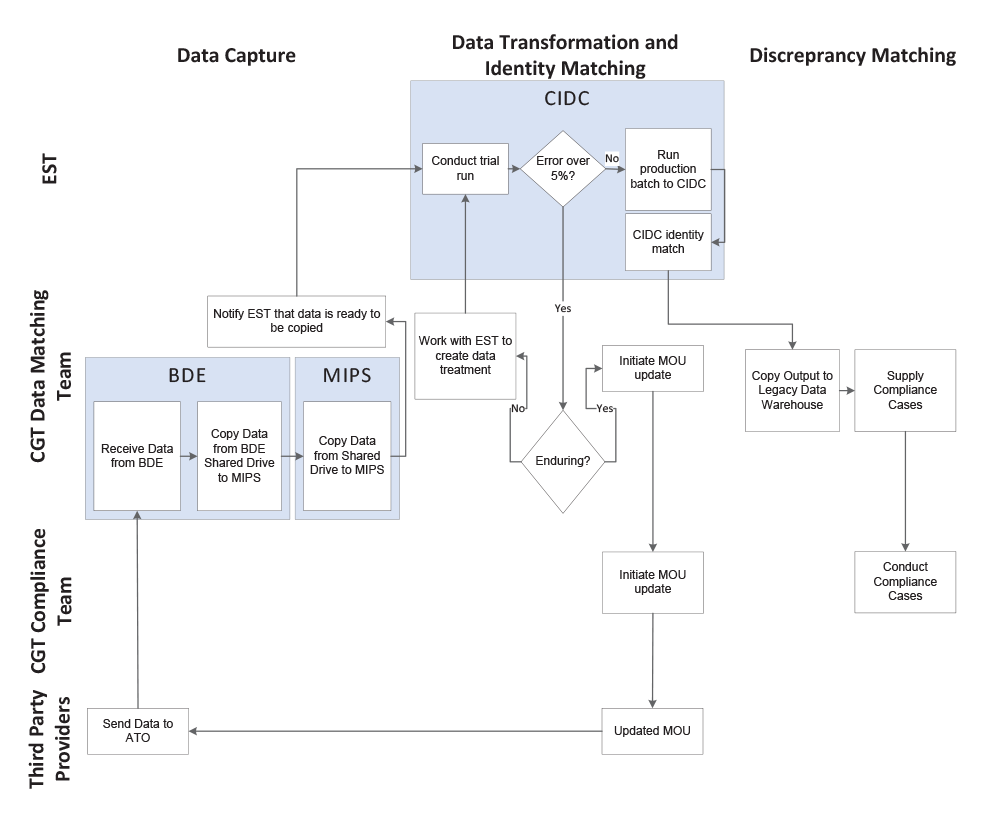

15. To support the CGT compliance letter strategy for individual taxpayers, the ATO obtains extensive data from third-parties in relation to real property and share transactions.19 Although the ATO has implemented extensive data cleansing and filtering processes, problems in matching this data to taxpayer declarations20 limits the number of CGT cases the ATO reviews and the accuracy of the potential non-compliance that is identified. As a consequence, the active compliance programs for individual taxpayers have had a heavy emphasis on real property and a limited focus on shares and other types of assets. To achieve a more balanced coverage across asset types, there would be merit in the ATO reassessing its capacity to target compliance activities for individual taxpayers across all asset types.

16. Despite the known problems with third-party data, the ATO sends letters to thousands of individual taxpayers each year, questioning the accuracy of their declarations of CGT. The outcome of this correspondence can be that the taxpayer contacts the ATO and clarifies their situation to the satisfaction of the ATO, or the ATO amends their assessment. The ANAO’s sample of 322 letters sent to individual taxpayers21 found that most did not result in further action by the ATO (59 per cent) and that many (almost half) of the amended assessments were subsequently reversed. This largely reflects a lack of accuracy of information in these letters, which impacts on the taxpayer’s experience and the ATO’s prospects of securing appropriate revenue. On this basis, the ATO would benefit from evaluating the effectiveness of its CGT bulk letter compliance strategy for individual taxpayers.

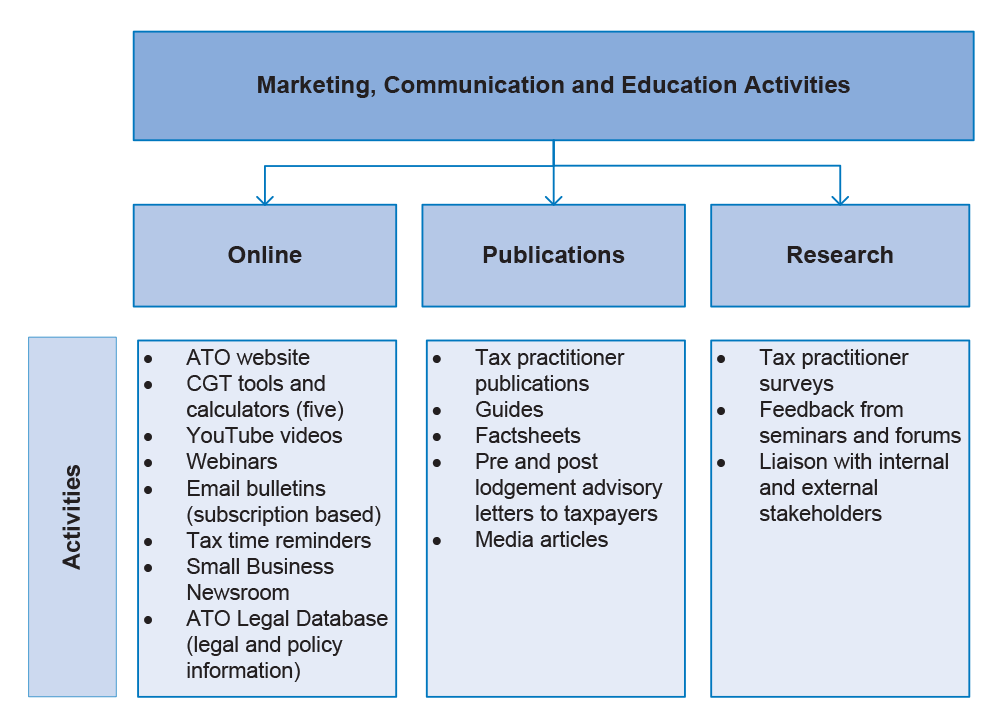

17. As mentioned previously, there has also been a significant reduction in revenue from specific CGT compliance activities for small business taxpayers—from $59.0 million to $30.3 million from 2011–12 to 2013–14. In 2014–15, the ATO expects to raise only $13.1 million from 32 specific CGT small business cases, and to incorporate CGT into the broader small business compliance program. To gain assurance that its CGT compliance strategies for individual and small business taxpayers are targeted effectively across the major categories of CGT events and, in the light of recent changes to CGT administrative arrangements22, it is important for the ATO to evaluate its strategies and activities.

18. To support the ATO’s administration of CGT, the ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the effectiveness of CGT compliance strategies and activities for individual and small business taxpayers.

Key findings by chapter

Management Arrangements (Chapter 2)

19. The management arrangements in place in the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers (SB/IT) Business and Service Line (BSL) are appropriate to support the administration of CGT for individual and small business taxpayers. Two separate business units within the BSL undertake compliance activity for CGT: Data Matching Compliance Strategies (DMCS) for individual taxpayers; and Small Business Compliance (SBC) for small business taxpayers. High-level planning for SB/IT aligns with the ATO’s corporate direction and more detailed planning is undertaken by these two business units. While performance monitoring and reporting activities for CGT in the BSL are suitable, CGT activities are not among the headline topics routinely monitored and reported to senior management, even though there has been a high risk rating in both the individuals and small business market segments for CGT.23

20. Despite significant decreases in revenue targets for CGT compliance activities involving individual and small business taxpayers in the last three years (of 44 per cent and 80 per cent respectively)24, the revenue achieved for DMCS and SBC has been variable and neither market segment exceeded 85 per cent of its original target in a single year. The ATO identified a range of factors that contributed to these trends, including changes in the composition of revenue targets at the team level and the reallocation of staff and work to other areas in the ATO. In this regard, the ATO advised that SB/IT staff reductions have been offset by advancements in technology and improved work practices, which support BSL revenue commitments; however, the benefits from these advancements and work practices have not been demonstrated or quantified.

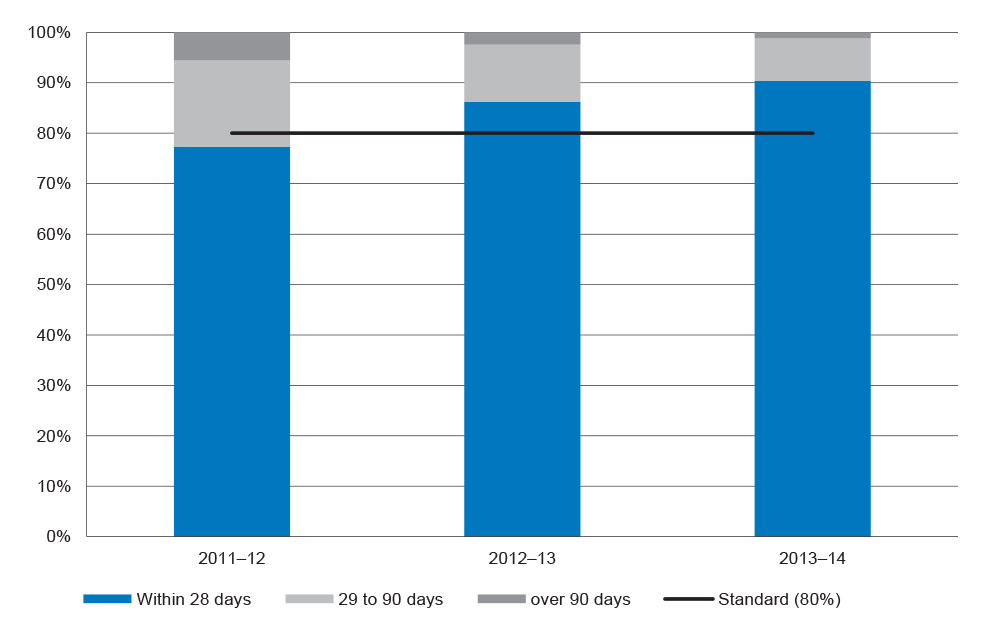

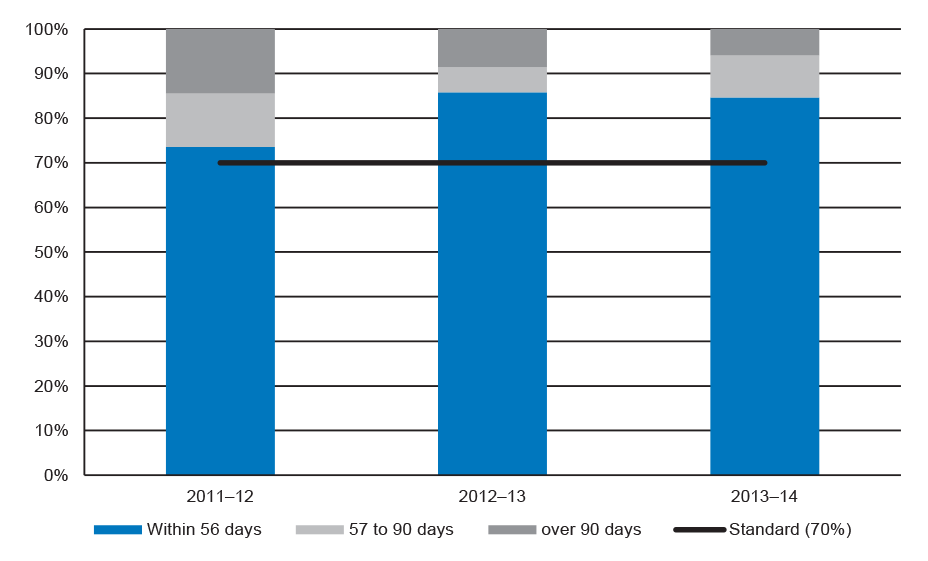

21. Going forward, there is considerable uncertainty about CGT compliance activity and the potential revenue from individual and small business taxpayers. The number of CGT specific review and audit cases in 2014–15 has reduced considerably in SBC and the benefits of incorporating CGT cases into the broader small business compliance program are yet to be confirmed. There is also uncertainty about the timing and impact on CGT compliance activity outcomes for individual taxpayers in relation to the implementation of the 2013–14 Budget measure.25 Given these developments, and the volatility of CGT revenue, the ATO needs to closely monitor the effectiveness of its administration and fine tune its approach in the light of experience to date.

Managing Compliance Risks (Chapter 3)

22. Risk planning for CGT takes account of ATO-wide market risks that are identified in annual planning processes and endorsed and monitored at a senior executive level. While these processes have been sound, the nature of the CGT system—including very little change over time in the identified risk events26 and participants—means that, without changes in legislative design, the CGT risk is likely to continue to be rated as high for the individuals and small business taxpayer market segments.

23. The management of CGT risk by SB/IT from 2010 to 2014 was appropriate and in accordance with the ATO’s corporate risk management process for compliance risks, which requires the preparation of a risk assessment, risk treatment plan and risk review. Both SBC and DMCS prepared these documents, and SBC also prepared target selection rationales and treatment evaluations, to guide operational activities for CGT compliance.

24. In conducting these risk processes, DMCS and SBC, for the most part, appropriately identified and assessed compliance risks for individual and small business taxpayers, respectively. While SBC is addressing emerging risks involving obtaining essential valuations for compliance cases and staffing changes that impact on the type of audit activity, these issues were not included in existing risk assessments. As significant organisational changes can also affect the administration of CGT, it is important that they are considered in annual risk reviews in the small business market sector.

Selecting Cases for Compliance Activity (Chapter 4)

25. Data matching activities for CGT enable the ATO to apply computer assisted data matching processes to third-party data to identify individual taxpayers outside the tax system, non-lodgers or discrepancies in taxpayer information, to identify potential non-compliance. As previously discussed, the ATO obtains third-party data from state and territory governments, the Australian Stock Exchange and selected share trading registries in relation to real property and share transactions to use for CGT data matching activities for individual taxpayers. This high degree of automation for case selection in DMCS generates thousands of potential cases each year (6153 CGT cases were finalised in 2013–14 from approximately 17 million new records received).

26. In contrast, SBC generally sources cases by analysing data held in ATO databases, such as in relation to: small business assets, income and liabilities; information on CGT schedules; and whether a small business concession was claimed. Considerably fewer potential cases are selected by SBC from such data analysis (406 CGT cases were finalised in 2013–14). The different arrangements in place for selecting taxpayer cases for CGT compliance action are generally appropriate for the different market segments.

27. The ANAO assessed the IT control framework for CGT data matching for individuals, including its design and the operation of matching rules, which support the selection of compliance cases. The main elements in the control framework are data capture, identity matching and discrepancy matching.27 The control framework supporting data matching for individual taxpayer compliance cases is mature and effective for CGT purposes.

28. Since the ANAO’s 2006–07 audit of CGT28, the ATO has concluded negotiations with all state and territory governments for the acquisition of real property data. This enabled the ATO to achieve national coverage for its CGT case selection and compliance activities for individual taxpayers. However, despite ongoing work with third-party data providers to improve the quality of the real property data received by the ATO, there have been no significant improvements in the ATO’s data matching processes or outcomes for CGT in the individual taxpayers market segment in recent years. The ATO is relying on legislation being passed by the Parliament implementing a 2013–14 Budget measure for third-party data, which is intended to substantially improve the data used to identify non-compliance with CGT obligations by individual taxpayers.29 There is currently a two-year deferral for the introduction of the legislative elements of this Budget measure, from 1 July 2014 to 1 July 2016.

Encouraging Voluntary Compliance (Chapter 5)

29. The ATO seeks to foster willing participation among taxpayers in the tax system as well as deal with non-compliance through compliance activities that seek to verify information or enforce tax law.30 It employs a variety of delivery channels to assist individual and small business taxpayers to understand and voluntarily comply with their CGT obligations including providing information and tools on the ATO website, email bulletins, and electronic and paper publications. There would be benefit in the ATO evaluating its communication strategies for CGT to gain assurance that communication activities are supporting individual taxpayers and their tax professionals to voluntarily comply with CGT obligations.

30. In the last three years (2011–12 to 2013–14), the ATO also finalised almost 4000 interpretive assistance products. These products are designed to help taxpayers by providing the Commissioner of Taxation’s opinion about the application of taxation laws. Private rulings (3126) primarily covered matters relating to: deceased estates; small business concessions; main residence exemptions; shares; subdivisions; and trusts. The ATO has improved its timeliness in finalising CGT private rulings in the last three years, which have a potential financial impact for both taxpayers and the ATO.

Conducting Compliance Activities (Chapter 6)

31. In the last three years, SBC finalised approximately 1400 CGT review and audit cases for small businesses, raised $143.5 million in liabilities and collected $33.6 million (23 per cent) in cash.31 SBC intends to undertake only 32 CGT cases in 2014–15, with a target of $13.1 million in liabilities raised, which is a significant decrease in the number of planned cases and potential liabilities compared to recent years.32 SBC advised that CGT work in 2014–15 will be included as a component of the other compliance cases it conducts with selected small businesses.

32. The ANAO analysed 95 small business cases for CGT that were finalised in the last two years (2012–13 to 2013–14) (approximately seven per cent of the cases finalised). The ANAO found that 26 cases (27 per cent) in the sample had liabilities raised, totalling $13.6 million—ranging from $5.8 million for a single case to a negative liability (an amendment in the taxpayer’s favour) of approximately $229 000. Most of the 95 cases were finalised by SBC within the expected cycle time (60 cases or 63 per cent), although these cases represented less than four per cent of the total liabilities raised. Conversely, 18 cases took in excess of 50 days beyond the cycle time to be finalised, but accounted for approximately 96 per cent ($13 million) of the total liabilities raised of $13.6 million. These findings highlight the importance of the ATO placing sufficient emphasis on liabilities raised from longer audits when balancing timeliness and financial outcomes in finalising small business CGT compliance cases.

33. For individual taxpayers, DMCS conducts its compliance cases through a series of bulk letter mailouts. Including a two-year pilot (in 2009–10 and 2010–11), approximately 27 000 cases have been finalised in the last five years using this approach, raising approximately $409 million in liabilities. The ANAO examined a sample of 322 CGT cases finalised by DMCS in 2012–13 and 2013–14. Around 40 per cent of those cases where letters were sent to taxpayers resulted in either an amended income tax assessment, the lodgement of a tax return or default assessment for taxpayers who had not previously lodged a tax return. However, almost half of those cases with an amended income tax assessment had an administrative reversal33 that substantially reduced the initial liability raised.

34. As previously discussed, in the last two years, DMCS CGT letters have resulted in the ATO contacting thousands of individual taxpayers with advice about the possibility of amending assessments because of the inaccurate self-assessment of CGT. While recognising that the ATO has recently strengthened processes to manually check the accuracy of the information contained in these letters, the results of the ANAO’s analysis of cases reviewed for 2012–13 and 2013–14 revealed a high proportion of letters (191 of the 322 letters sent or 59 per cent), that did not result in further action by the ATO. To better target letters at non-compliant taxpayers, the ATO should evaluate the use of bulk mailouts for CGT compliance and identify ways to increase their effectiveness. An evaluation of CGT compliance strategies across all relevant market sectors (using the ATO’s Compliance Effectiveness Methodology34) would extend the benefits of the recommended evaluations of CGT effectiveness focusing on individual and small business taxpayers.

35. In the last three years, the objection rate for CGT compliance cases for individual and small business taxpayers was low (2031 finalised objections, or 7.3 per cent of finalised compliances cases), and over half of those objections were allowed in full or in part each year in the taxpayer’s favour. Each year, from 2011–12 to 2013–14, SB/IT’s timeliness performance for finalising CGT objections exceeded the ATO‘s corporate standard of 70 per cent of objections being finalised in 56 calendar days of receiving the necessary information.35

Summary of entity response

36. The ATO’s formal response is included at Appendix 1.

The ATO welcomes this review and the finding that the ATO’s compliance approach toward the administration of CGT for small businesses and individuals is generally effective.

In relation to your finding that CGT revenue targets have not been met in recent years, we would note the impact of The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) on asset values. Many of the potential gains that relate to assets that were disposed of were not able to be realised following the GFC in both the individual and small business markets. We appreciate that you have recognised the volatile nature of CGT revenue due to market forces.

The ATO also would like to highlight that significant improvements have been made to our processes for CGT in the individual market segment. Using a variety of new data matching techniques, such as cross matching against other data sources and reviewing prior year results, strike rates have improved over the three year period from 47% to 70%. This has also resulted in better targeted and reduced volumes of letters issuing to the community.

The ATO agrees with the one recommendation made in the report and recognises the audit highlights opportunities to further improve the effectiveness of our CGT compliance strategies.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 6.42 |

To determine the effectiveness of its capital gains tax (CGT) compliance strategies and activities, the ANAO recommends that the ATO:

ATO response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides background information about the administration of capital gains tax, and explains the audit approach and structure of the report.

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is the Government’s principal revenue collection agency. The ATO’s roles and objectives are to effectively and fairly administer the taxation system, regulate aspects of the superannuation system, and support the delivery of government benefits to the community. In 2013–14, the ATO had an operating budget of $3.6 billion and approximately 23 600 staff. During the period, the ATO processed 16.5 million tax return lodgements and collected $230.9 billion in income tax from individuals ($163.6 billion) and companies ($67.3 billion).36

1.2 Income tax revenue is derived from a number of sources such as wages and salaries, investment income (interest and dividends), and business income. One component of the total income tax collected by the ATO is capital gains tax (CGT).37

Capital gains tax

1.3 The ATO explains CGT as follows:

A capital gain or capital loss is the difference between what it cost you to get an asset and what you received when you disposed of it. You pay tax on your capital gains.38

1.4 There are a number of transactions or events that may result in a capital gain or capital loss.39 While 53 CGT events are listed in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997), the most common way to make a capital gain or loss is through the sale of assets such as real property40 or shares, although CGT can also apply to intangible assets such as business goodwill and intellectual property.41 Some assets are also exempt from CGT, including:

- major personal assets, particularly a private (main) residence and motor vehicle, and most personal use assets, such as furniture; and

- depreciating assets used solely for taxable purposes, for example, business equipment or fittings in a rental property.

1.5 In addition to the exemptions and rollovers for CGT, four types of small business42 CGT concessions are available to provide relief from the CGT system, subject to entities meeting specific conditions. The concessions are the:

- 15-year exemption—provides a total exemption for a capital gain on a CGT asset if an asset has been continuously owned by an individual in business who is 55 years old or older and is retiring or permanently incapacitated;

- 50 per cent active asset reduction—provides a 50 per cent reduction of a capital gain if the taxpayer is a small business and the ‘active asset’ test can be met. A CGT asset is an active asset if it is owned by the individual and connected to carrying on a business;

- retirement exemption—can exempt a capital gain on a CGT asset up to a lifetime limit of $500 000; and

- rollover—allows a taxpayer to defer all or part of a capital gain on a business asset for a minimum of two years.

Introduction of CGT

1.6 When the Hawke Government introduced the CGT in 1985, a similar type of the tax existed in many countries including Great Britain, the United States, Japan and Switzerland. The CGT system was intended to: include capital gains as assessable income; reduce tax avoidance practices; and promote appropriate capital investment in Australia.43

1.7 Unless specifically excluded, CGT applies to all assets acquired on or after 20 September 1985. CGT also applies to Australian residents’ assets anywhere in the world.44 In addition, foreign residents can be subject to CGT, in accordance with the ITAA 1997 (Division 855).

Revenue from CGT

1.8 The ATO collects substantial revenue from CGT, in total and from key categories of taxpayers—individuals, companies and superannuation funds. CGT revenue is, however, volatile and influenced by domestic and international economic conditions, such as the global financial crisis, and local factors such as natural disasters. These events can affect people’s financial behaviour and influence the real property and stock markets.

1.9 The latest available tax statistics (2010–11 to 2012–13) show that most CGT was paid by individuals (58 per cent) during this period, with companies contributing around 37 per cent of the estimated total tax payable on capital gains (Table 1.1).45 Of CGT paid by companies, most was paid by small business (over 45 per cent in 2011–12), with 36 per cent from large and international businesses in the same year, and the remainder from medium-sized businesses (18 per cent).46

Table 1.1: Entity type and net capital gains, 2010–11 to 2012–13

|

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

|

Individual taxpayers |

|||

|

Number of individual taxpayers |

13 275 055 |

13 182 415 |

12 776 080 |

|

Number with taxable net capital gains |

465 340 |

354 580 |

389 415 |

|

Net capital gains ($ million) |

11 874 |

9 107 |

9 327 |

|

Estimated tax payable on gains ($ million) |

3 910 |

3 024 |

3 127 |

|

Companies |

|||

|

Number of companies |

870 550 |

879 175 |

854 790 |

|

Number with taxable net capital gains |

9 765 |

8 465 |

8 770 |

|

Net capital gains ($ million) |

7 194 |

6 292 |

10 506 |

|

Estimated tax payable on gains ($ million) |

1 835 |

1 713 |

2 838 |

|

Superannuation funds |

|||

|

Number of funds |

424 905 |

448 015 |

451 625 |

|

Number with taxable net capital gains |

52 585 |

42 905 |

52 070 |

|

Net capital gains ($ million) |

2 188 |

1 481 |

1 703 |

|

Estimated tax payable on gains ($ million) |

360 |

243 |

260 |

|

Total number with net capital gains |

668 460 |

510 530 |

576 175 |

|

Total net capital gains ($ million) |

24 282 |

19 320 |

23 869 |

|

Estimated tax payable on gains ($ million) |

6 106 |

4 980 |

6 226 |

Source: ATO, Taxation Statistics 2012–13, Table 2: Capital gains tax—Net capital gains subject to tax, by entity type, 1989–90 to 2012–13 income years.

Note: Totals are as presented in the source table, with some totals not equalling the sum of the components due to rounding.

1.10 In 2012–13, the estimated tax payable on net capital gains47 ($6.2 billion) represented two per cent of the total net tax collected by the ATO ($311.7 billion) in that year.48 In the 2015–16 Federal Budget, CGT receipts for 2013–14 were reported as $7.2 billion49 (some 2.2 per cent of the $321.7 billion total net tax collected by the ATO).50

ATO administration of CGT

1.11 Responsibility for the administration of CGT rests with the Second Commissioner for Compliance, and the tax is administered in the Compliance Group. Within this group, the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers (SB/IT) Business and Service Line (BSL) manages the tax and superannuation systems for taxpayers from the small business, individuals and employers markets. CGT is one component of these activities.51 At the beginning of 2014–15, SB/IT had 2077 full-time equivalent staff located around Australia, and received a budget allocation of $173.1 million.

Compliance activities

1.12 The ATO undertakes a range of activities designed to assist people to understand and comply with their taxation obligations, including providing educational material and conducting active compliance work. Compliance activities—audits, reviews52 and correspondence53—are to be undertaken in a way that is consistent with the principles in the ATO’s Taxpayers’ Charter for client service. In 2013–14, the ATO undertook CGT compliance activity in all major market segments, including the individuals and small business markets.54

1.13 The generic behavioural drivers for taxpayer non-compliance range from lack of understanding through to calculated tax minimisation and deliberate tax avoidance. While the ATO considers that most taxpayers meet their CGT obligations, it has rated the risk of non-compliance with CGT requirements as ‘high’55 for the individual taxpayer and small business market segments. This rating is largely due to complex law design, the one-off nature of capital events and an absence of reliable data about those events.

Legislative design

1.14 For several years, the ATO has identified a number of problems with the current design of the CGT system and considers that these inherent weaknesses undermine the system’s effectiveness. They include:

- increasing legislative complexity, as well as interactions with other tax law;

- the absence of comprehensive, matchable third-party reporting to alert the ATO of potential CGT liability;

- inadequate CGT data being captured on tax returns to enable assessments of the risk of non-compliance; and

- the absence of a CGT withholding regime.56

1.15 The ATO considers that the substantial volume of guidance material produced for taxpayers about CGT reflects the growing legislative complexity of the CGT system. This view is supported by coverage of CGT in the Australian Master Tax Guide (June 2014)—a tax reference manual designed for practitioners, businesses, other organisations and students. The latest edition of the guide is over 2000 pages and contains almost 200 pages (10 per cent) dedicated to general and special CGT matters.

Recent Budget measure for third-party data

1.16 In November 2013, the Government announced its intention to proceed with, amend or not proceed with, a large number of announced but unlegislated taxation and superannuation measures, including a number relating to CGT. A CGT measure that is proceeding, and that will affect individual and small business taxpayers, is the 2013–14 Budget measure for Tax compliance—improving compliance through third-party reporting and data matching. This measure is designed to improve compliance and increase taxation revenue by expanding the ATO’s ability to match the data provided by third-parties, in relation to for example the sale of real property, shares and units in managed funds. Subsequently, the Government announced in May 2014 that there would be a two-year deferral of the legislative elements of the measure from 1 July 2014 to 1 July 2016, following feedback from stakeholder consultations. The ATO considers that its ability to detect and treat the risks associated with CGT will be improved through these measures.57

1.17 Another aim of the 2013–14 Budget measure for third-party reporting and data matching is to assist the ATO to improve the pre-filling of tax returns, which would make it simpler for taxpayers who want to comply with their CGT obligations and prompt those who need encouragement to do so.58

ATO reforms

1.18 In recent years, the ATO has commenced an organisation-wide change program. The Reinventing the ATO program is supported by a vision for 2020 that the ATO will be: ‘a leading taxation and superannuation administration known for our contemporary service, expertise and integrity’.59 One of the key concepts underpinning the Reinventing the ATO program is designing a taxation system for the majority of taxpayers who do the right thing. The ATO intends to reward taxpayers’ openness, transparency and willingness to participate in the taxation system by requiring less effort to comply (referred to by the ATO as a ‘no touch’ or ‘light touch’ approach) and increasing taxpayers’ certainty about the status of their taxation matters.

Tax discussion paper—Re:think

1.19 As part of its 2014–15 Budget strategy and priorities, the Government announced the development of a White Paper on the reform of Australia’s tax system, which is designed to provide a longer-term approach to tax reform.60 One of the key issues for the White Paper is the competitiveness of Australia’s tax system, particularly corporate tax and new domestic and foreign investment. A task force was established in the Department of the Treasury (the Treasury) to support the development process. The Treasury and the ATO jointly undertake activities to improve the ongoing design of tax and superannuation laws. As part of the process for developing the White Paper, a tax discussion paper—Re:think—was published in March 2015 that includes references to CGT.61 The future White Paper could include a discussion of the CGT system and the potential for reforms that would simplify the system.

Previous ANAO audit

1.20 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examined the ATO’s administration of CGT eight years ago—Audit Report No.16 2006–07 Administration of Capital Gains Tax in the Individuals Market Segment. The focus of the audit was the ATO’s administration of compliance by individuals with respect to the two most common CGT events: real property and share disposals. The audit concluded that the ATO’s administration of CGT for that market was effective. The audit made seven recommendations aimed at improving the ATO’s administration of CGT for individuals in the areas of: CGT project planning; data management and risk assessment; and compliance planning. The ATO agreed to all recommendations (see Appendix 2).

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Audit objective

1.21 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of capital gains tax for individual and small business taxpayers.

Audit criteria and scope

1.22 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- management arrangements support the effective administration of CGT for individual and small business taxpayers;

- compliance risks are assessed and a coherent strategy is in place to promote compliance with CGT requirements; and

- compliance activities are appropriate and effective.

1.23 The ANAO focussed on CGT work undertaken in the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line.62 The audit also includes a review of the implementation status of the seven recommendations from the 2006–07 ANAO audit report.

Methodology

1.24 In conducting the audit, the ANAO reviewed relevant documentation and interviewed key staff at a number of ATO offices. The ANAO consulted a range of stakeholders, including taxpayer representatives and tax professional bodies, providers of third-party data and staff from the Treasury.

1.25 The ANAO analysed the data matching activities that support the ATO’s CGT risk assessments and compliance work and sampled 472 CGT compliance cases in the individual and small business markets.

1.26 The audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost of approximately $547 000.

Structure of the report

1.27 Table 1.2 outlines the structure of the remaining five chapters.

Table 1.2: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

||

|

2 |

Management Arrangements |

Examines the management arrangements supporting the administration of capital gains tax for individual and small business taxpayers, including performance monitoring and reporting on revenue. |

|

|

3 |

Managing Compliance Risks |

Examines the ATO’s identification and management of capital gains tax compliance risks for individual and small business taxpayers. |

|

|

4 |

Selecting Cases for Compliance Activity |

Examines the ATO’s case selection processes for capital gains tax compliance activity in relation to individual and small business taxpayers. |

|

|

5 |

Encouraging Voluntary Compliance |

Examines the ATO’s activities to promote voluntary compliance with capital gains tax obligations by individual and small business taxpayers. |

|

|

6 |

Conducting Compliance Activities |

Examines the ATO’s activities to address non-compliance by individual and small business taxpayers that do not comply with their capital gains tax obligations. |

|

2. Management Arrangements

This chapter examines the management arrangements supporting the administration of capital gains tax for individual and small business taxpayers, including performance monitoring and reporting on revenue.

Introduction

2.1 As previously noted, the Second Commissioner for the Compliance Group has overall responsibility for the administration of CGT. Within the Group a number of operational BSLs have responsibility for discrete market segments, particularly: Public Groups and International (PG&I); Private Groups and High Wealth Individuals (PGH); and Small Business and Individual Taxpayers (SB/IT).

2.2 While other BSLs in the group have a business interest in CGT, the ANAO primarily focussed on examining the management arrangements in SB/IT for CGT, including:

- its organisational structure;

- planning arrangements;

- performance monitoring and reporting; and

- complaint handling and taxpayer feedback.

Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line organisational structure

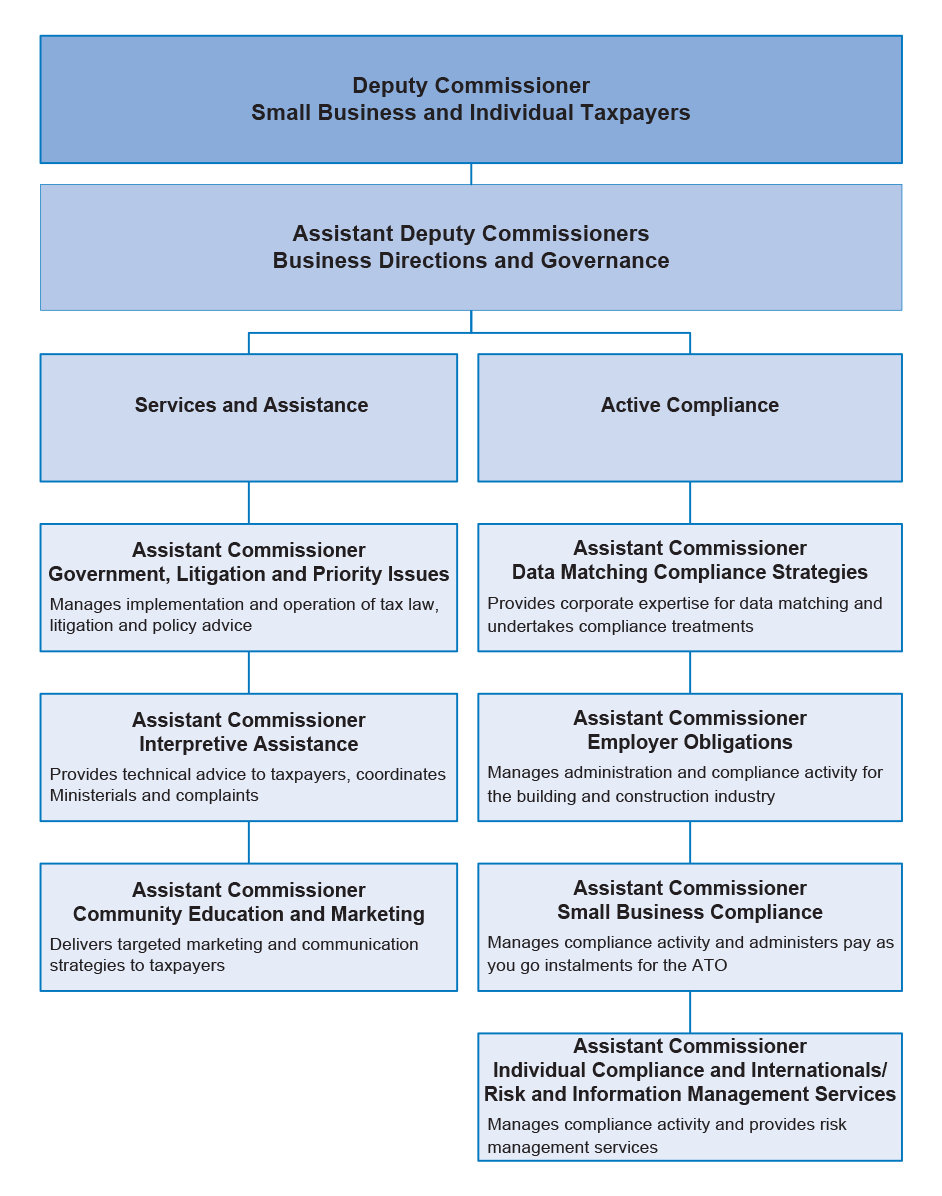

2.3 At the beginning of 2014–15, SB/IT had 2077 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff located across Australia and the BSL received a budget allocation of $173.1 million. An overview of SB/IT’s organisation structure is provided in Figure 2.1 and outlines the seven administrative streams, which are each managed by an Assistant Commissioner. An annual SB/IT Line Plan is developed to support the delivery of ATO corporate activities and programs and is underpinned by further detailed plans at the stream and local team level.

Figure 2.1: Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line organisational structure

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

2.4 Two streams undertake compliance activity for CGT—Data Matching Compliance Strategies (DMCS) and Small Business Compliance (SBC). In 2014, DMCS had an average FTE staffing level of 350 officers and a total actual budget of $29.9 million. SBC had an average FTE staffing level of 126 officers and a total actual budget of $13.5 million. These organisational arrangements clearly outline responsibilities for CGT compliance strategies and activities, and also support broader administrative arrangements for the tax, such as providing interpretative assistance and risk management services.

Planning arrangements

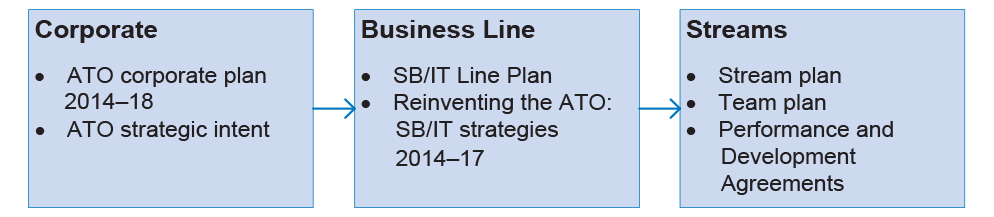

2.5 In 2014–15, business planning, performance monitoring and reporting are linked activities in SB/IT. Figure 2.2 identifies the main documents required to support the top down planning process for SB/IT. In particular, the ATO corporate plan 2014–18 includes the ATO’s priorities for 2014–15 and sets out its future plans.63 The SB/IT Line Plan identifies the key priorities, and high-level strategies and activities for the BSL that contribute to achieving the priorities in the corporate plan.64

Figure 2.2: Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line planning framework 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

2.6 Overall, the planning framework for SB/IT aligns with the ATO’s corporate direction. The endorsed August 2014 SB/IT Line Plan provided more detailed planning at the individual stream level, including for CGT activity, but did not include final details of the financial allocations or enterprise risks.

2.7 The 2014–15 individual team plan for DMCS outlines the team’s: roles and responsibilities; focus for the year; staffing level; and deliverables, including the number of compliance cases and revenue expected to be achieved by the team.65 In SBC, the compliance plan for all work to be undertaken by the stream in 2014–15 identifies CGT activity and specifies: the type of product to be undertaken (audit); the channel (by correspondence); the case management system to be used for the audits; and the number of cases and revenue target.66

Previous ANAO audit planning recommendation

2.8 The 2006–07 ANAO audit examined the planning process for a four-year CGT project that commenced in July 2004 and focused on capital gains arising from real property and share disposals in the individuals market segment. The ANAO recommended that CGT project planning be improved at the operational level, including by preparing an annual delivery plan and linking relevant planning documents from across the operational streams.67 The ATO agreed with the recommendation and advised that it was completed in October 2007 (see Appendix 2 for details of Recommendation No.1). The CGT project has been replaced by business-as-usual administration for CGT and is supported by adequate corporate and SB/IT planning processes.

Performance monitoring and reporting

2.9 Performance monitoring and reporting systems, when aligned with the entity’s outcomes and programs structure, provide information that is appropriate for internal performance management needs and external reporting requirements.68 Furthermore, once budgets and revenue targets are established, regular monitoring of actual performance against approved budgets and targets is important to ensure that actual expenditure and revenue targets are in line with budget estimates.

Internal monitoring and reporting

2.10 The internal monitoring and reporting framework for SB/IT in 2014–15 is comprehensive, with reporting from the individual BSL stream level through to corporate reporting, including external reporting in the ATO’s annual report (see paragraph 2.25).

2.11 The SB/IT Line Plan 2014–15 contains a range of high-level performance measures for the major activities identified in the plan. While more performance measures are contained in the DMCS and SBC stream plans, those plans are also at a high-level.

2.12 The SB/IT reporting framework includes key monthly stream and line reports—known as Heartbeat reports—that are used to monitor progress within the BSL during the year against performance measures in the Line Plan.69 The Heartbeat reports also outline the progress being made towards achieving annual revenue targets and enable the SB/IT executive to monitor performance across the BSL.

2.13 In addition, the BSL produces regular monthly and quarterly reports that are aggregated and considered by the Compliance Group and the ATO’s executive management team. The focus of these reports is performance across key BSL activities, for example, interpretative assistance. The reports are by exception and highlight underperformance during the year and indicate the likely end of year result. Given the aggregation process, senior management external to the SB/IT BSL would not routinely have visibility of CGT activities, unless there was a key performance issue.

SB/IT executive meetings and committees

2.14 In addition to reporting by stream, the coordination and monitoring of work outcomes is supported by SB/IT executive teleconferences, briefing advice from teams and monthly meetings. At a higher organisational level, CGT is discussed at meetings of the Income Tax Steering Committee. Membership of this senior management committee is drawn from all three Groups in the ATO and it is responsible for contributing to the strategic direction of income tax administration (including pay as you go withholding and instalments, CGT and fringe benefits tax). In July 2014, representatives from SB/IT were present when the committee discussed the 2014 CGT Health of the System Assessment (HOTSA).70

2.15 Prior to June 2013, the ATO had convened for many years a National Tax Liaison Group Losses and CGT Sub-committee that acted as a consultative forum and was attended by ATO officials and tax practitioners.71 At its final meeting, the sub-committee considered items such as the small business CGT retirement exemption and a CGT and losses compliance report.72 The 2014 CGT HOTSA refers to the closure of the sub-committee and the: ‘potential loss of forum to discuss CGT specific issues unless deemed a “big tax” issue facing Australia’.73

Revenue targets

2.16 The Treasury is responsible for preparing the Government’s taxation revenue forecasts, while the ATO is the Government’s principal revenue collection entity. According to a recent Treasury review74, the methodology it uses for revenue forecasting is similar to comparable official agencies overseas. The ATO contributes to revenue forecasting as a reviewer of the Treasury’s revenue forecasts and by undertaking business liaison with entities to supplement the modelling used for forecasting. It is important therefore that the ATO’s own revenue collection targets for compliance activities are appropriate, including achieving a balance across the full range of compliance risks and delivering a reasonable return on investment.

2.17 Compliance Group BSLs directly contribute to achieving the ATO’s overall revenue target each year from active compliance cases.75 In SB/IT, annual revenue targets for each stream are set by the SB/IT executive and the respective Assistant Commissioners determine the revenue targets for DMCS and SBC.76 In both streams, CGT is one component of the work undertaken and there are a range of factors taken into account when allocating team budgets and staffing. These factors include a requirement to effectively manage ongoing risks in the CGT system within the respective market segments, and to efficiently resource compliance case teams to achieve revenue targets.77 Therefore, while the maintenance of a compliance program for CGT is essential, the ATO advised that the setting of CGT revenue targets is discretionary and judgement is informed by past experience and performance outcomes from finalised cases.

2.18 Table 2.1 shows the revenue targets and total revenue achieved for 2012–13 and 2013–14, and the 2014–15 target and revenue collected to date from compliance activities in SB/IT.

Table 2.1: Capital gains tax revenue from compliance activities for individual and small business taxpayers, 2012–13 to 2014–15

|

|

2012–13 |

|

2014–15 |

||||

|

Taxpayer |

Individual |

Small business |

Individual |

Small business |

Individual |

Small business |

|

|

Original revenue target ($ million) |

250.0 |

65.0 |

133.0 |

50.0 |

140.0 |

13.1 |

|

|

Total revenue ($ million) |

203.9 |

54.2 |

104.7 |

30.3 |

138.01 |

18.31 |

|

|

Proportion of revenue target met |

82% |

83% |

79% |

61% |

NA2 |

NA2 |

|

Source: Internal data provided by the ATO.

Note 1: Revenue as at the end of May 2015.

Note 2: NA is not applicable, as the year had not been completed.

2.19 The ATO advised that a number of factors had contributed to the decrease in revenue targets for individual taxpayers in 2012–13 and 2013–14. These included:

- The same team is responsible for CGT and partnerships, trusts and units compliance case activity and reports against a single (aggregated) target. At the team level, the revenue target has been redistributed during the period away from predominantly CGT revenue to a more equal allocation between the two areas. This redistribution reflects the ATO’s increased understanding of the size of the partnerships, trusts and units risk and the need to ensure adequate coverage of both risks.78

- The introduction of a designated CGT case selection team and manual profiling process (see Chapter 4), to improve the selection of compliance cases, affected the CGT component of the team’s work as efforts were made to improve the outcomes from CGT compliance activity.

2.20 As outlined in Table 2.1, the original CGT revenue targets in DMCS and SBC were not met for the last two years and the total revenue achieved ranged from 61 per cent to 83 per cent of the target.79 The ATO advised that, at the end of May 2015, the revenue achieved to date for the 2014–15 financial year from individual taxpayers was $138 million (99 per cent of the target80) and for small businesses, $18.3 million (140 per cent of the target). As discussed in Chapter 6, final revenue amounts for compliance activity are subject to the outcome of taxpayer objections to tax assessments and/or debt management processes that can spread payments across income years.

2.21 The ATO advised that a number of factors contributed to the reduction in CGT revenue targets for small businesses and the total revenue collected for the same two-year period:

- until recently, the revenue from compliance activity for CGT small business concessions was considered quite high by SBC. The separation of that work between SBC and the Wealthy Australians program in PGH resulted in a gradual decline in CGT revenue.81 Accordingly, SBC changed its focus in 2014–15 to treat an expanded range of risks in the small business market and also included CGT as a component of its comprehensive audit program for small businesses; and

- a reduction in the overall number of compliance staff in SBC from 2012–13 to 2014–15, and change in the profile of operational staff—a 61 per cent increase in Australian Public Service (APS) level 4 staff, and a 32 per cent decrease in APS5 and APS6 staff—reduced the number of CGT-specific compliance cases able to be completed in each financial year. Most CGT small business concession work was undertaken by APS5 and APS6 senior level staff.

2.22 The 2006–07 ANAO audit found that, for the ATO’s annual Compliance Programs from 2002–03 to 2005–06, the ATO consistently met or exceeded its CGT coverage commitments for the individuals market.82 By comparison, in the three most recent years shown in Table 2.1, there has been a significant reduction in the revenue targets for CGT compliance activity. These reductions are partially explained by BSL and stream reorganisations of work functions to accommodate changes in risk in the individual and small business market segments. In this regard, the ATO advised that SB/IT staff reductions have been offset by advancements in technology and improved work practices, which support BSL revenue commitments. However, benefits from these advancements and work practices are yet to be demonstrated or quantified. DMCS is also anticipating that the implementation of the 2013–14 Budget measure designed to improve third-party data matching will positively impact on its CGT operations. In the future, the ATO expects further changes in resourcing and skilling to affect its approach to compliance work as the Reinventing the ATO program is implemented.

Previous ANAO audit recommendation for revenue targets

2.23 When examining CGT active compliance planning in the individual taxpayer market segment, the previous ANAO audit identified a range of issues around targets for liabilities and the application of cash collection rates.83 The ANAO recommended that, to inform future compliance planning, the ATO determine and document its methodology for setting the CGT project liabilities and cash collection targets, and consistently apply the cash collection rate to liabilities raised. The ATO agreed with the recommendation and advised that it was implemented in October 2007 with the preparation of: various plans setting out a process to estimate project liabilities; and a cash collection methodology developed by the ATO’s Revenue Analysis Branch (see Appendix 2 for details of Recommendation No.7).

2.24 The ATO’s current Active Compliance Collection Rate Method 2013–14 is used to determine collection rates on active compliance work undertaken by the ATO and to inform individual BSL planning, which includes details of CGT compliance activities in SB/IT.84 The methodology is documented and routinely applied to compliance activities, which provides a greater degree of certainty for SB/IT when setting revenue targets as to how cash collection amounts will be calculated. Notwithstanding this methodology, the prime focus in SB/IT in monitoring and managing revenue from CGT compliance activities has been on liabilities raised, with much less attention given to cash collected.

External reporting

Portfolio Budget Statements and annual report

2.25 The ATO’s program objectives, deliverables and key performance indicators are published annually in the Treasury’s Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS). The PBS does not make any reference to CGT, which forms part of income tax. Correspondingly, the ATO’s annual report for 2013–14 makes only limited references to CGT matters.85

Taxation statistics for CGT

2.26 While there is limited reporting on CGT in its annual reports, the ATO produces yearly taxation statistics on its website. An annual publication, Taxation statistics, summarises statistical information from taxpayers, primarily from income tax returns and including CGT schedules.86 The schedules contain information about the value of capital gains and losses from CGT assets and events and CGT concessions for small businesses.

2.27 There are also a number of CGT specific data sets87 available on the ATO’s website and the data is also available from the Australian Government’s data.gov.au website. The main purpose of that website is to encourage public access to and reuse of government data by providing it in useful formats under open licences.88 The ATO makes available CGT data that is public, timely and accessible.

Complaint handling and taxpayer feedback

2.28 The management of complaints and other feedback should form part of the monitoring and reporting of an entity’s performance and can be used to make improvements in service delivery for the community. The ATO has established procedures for the management of complaints and other feedback. While a centralised team oversees complaints management, the resolution of complaints is devolved to BSLs.89 Table 2.2 shows the CGT related complaints and other feedback received by the DMCS and SBC streams for individual and small business taxpayers from 2011–12 to 2013–14.

Table 2.2: Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line capital gains tax related complaints and other feedback, 2011–12 to 2013–14

|

Type of receipt recorded |

Individuals |

Small business |

|

Complaints |

47 |

5 |

|

Compliments |

0 |

0 |

|

Feedback |

0 |

0 |

|

Queries to members of parliament1 |

8 |

0 |

|

Ministerials |

17 |

0 |

|

Total receipts |

72 |

5 |

Source: ATO.

Note 1: Each BSL has a direct phone number for federal members of parliament to contact the ATO with constituent enquiries or issues.

2.29 For the three-year period shown in Table 2.2, a total of 52 complaints relating to CGT were received from individual and small business taxpayers and 25 inquiries from individual taxpayers. By comparison, in 2013–14, the ATO received approximately 23 900 complaints in one year.90 The ANAO examined the records for approximately one third of the total feedback cases (28) and found that the most frequent topics raised by taxpayers were main residence exemptions (13) and other property related matters (eight). Only two inquiries related to share transactions.91 Overall, SB/IT recorded a comparatively low number of complaints about CGT, and most complaints were from individual taxpayers, who are contacted in much greater numbers each year by DMCS compared to SBC contact with small businesses (see Chapter 6).

Conclusion

2.30 Appropriate management arrangements are in place in the SB/IT BSL to support the administration of CGT for individual and small business taxpayers. In 2014–15, the high-level planning framework for SB/IT aligns with the ATO’s corporate direction and supports the more detailed planning for CGT that occurs at the stream and team levels. Business planning and performance monitoring and reporting are linked activities in SB/IT and are supported by a number of corporate and BSL reports, although routine CGT activities are not monitored and reported to senior management.

2.31 In DMCS and SBC, there were significant decreases in the specific revenue targets for CGT for individual taxpayers (in the last two years) and small business taxpayers (in the last three years), which related in part to changes in the composition of revenue targets at the team level and the reallocation of staff and work to other areas of the ATO. While a level of compliance activity was maintained, neither market segment exceeded 85 per cent of its original revenue target in a single year.

2.32 There is considerable uncertainty about future CGT compliance activity for individual and small business taxpayers as: revenue targets continue to fluctuate for both market segments; the number of CGT specific review and audit cases in 2014–15 reduced considerably in SBC and the benefits of incorporating CGT cases into the broader small business compliance program are yet to be confirmed; and uncertainty remains about the timing and impact on CGT compliance activity outcomes for individual taxpayers in relation to the implementation of the 2013–14 Budget measure.

3. Managing Compliance Risks

This chapter examines the ATO’s identification and management of capital gains tax compliance risks for individual and small business taxpayers.

Introduction

3.1 Central to the ATO’s conduct of compliance activities is the identification and management of risk. A sound analysis of the likelihood and consequences of risks enables risk managers to make informed decisions about risk mitigation strategies. It also enables the ATO to direct resources towards those taxpayers who do not comply with their CGT obligations.

3.2 The ATO has an Enterprise Risk Management Framework to support the broad management of risk across all taxpayer groups and market segments. There are also specific processes in SB/IT for managing CGT compliance risks for individual and small business taxpayers.

3.3 To assess the ATO’s management of CGT compliance risks for individual and small business taxpayers, the ANAO examined:

- the coverage of these risks within the ATO’s corporate risk planning arrangements;

- DMCS’ and SBC’s risk management processes; and

- the implementation of the previous ANAO audit recommendations relating to CGT compliance risks in the individuals market segment.

Corporate risk planning

3.4 The ATO’s risk management policy sets out the responsibilities of staff in relation to risk management and includes guidelines to support the policy’s application.92 The ATO manages risk at three levels; enterprise, operational, and tactical.

Enterprise Risk Manager

3.5 The ATO uses an Enterprise Risk Management Framework93 to support its management of risk. A fundamental component of this framework is an ATO-wide risk register—the Enterprise Risk Manager (ERM). The ERM records enterprise and operating level risks as soon as practicable after they are identified and assessed (risk rated). The ERM also has the capacity to store supporting documentation such as risk assessments, treatment plans and reviews.

3.6 In 2014–15, the ATO identified seven separate CGT risks in the ERM.94 Since June 2014, the CGT enterprise risk owner (based in PG&I) has been overseeing a review aimed at consolidating those risks into a single CGT risk description and risk assessment in the ERM.95 The ATO has been moving towards a more holistic approach to CGT aimed at reducing the existing potential for duplication of effort in risk management by individual BSLs.96

3.7 In SB/IT, CGT is identified for both individual and small business taxpayers as an operational level risk that is ongoing, whereby there is a continual risk of taxpayers failing to understand and meet their CGT obligations. The CGT risk has been rated as ‘high’ for both markets, which is a combination of the consequence rating (risk to revenue and reputation, and impact on voluntary compliance) and the likelihood rating (either the frequency of issues in the risk population or probability of the risk occurring).

3.8 The high risk rating is based on a number of factors (such as taxpayers’ lack of understanding of their obligations, including the need to retain detailed records, and complexity of the law), and indicates the need for ongoing compliance activity for the CGT risk. The rating is also consistent with the findings from this audit. While the audit identifies factors presently beyond the ATO’s control (such as the usefulness of third-party data for CGT compliance activities with individual taxpayers), it also raises issues about factors within its control (such as improving the effectiveness of CGT compliance activities for individual taxpayers and the scale of specific CGT active compliance for small business taxpayers).

Health of the System Assessment

3.9 The Health of the System Assessment (HOTSA) update is part of the ATO’s formal annual planning process. The HOTSA is designed to support the review of significant or emerging risks, and provides an annual checkpoint for the risk management cycle. In assessing the risks of taxpayers not complying with the CGT system as part of the HOTSA process, the ATO draws on a range of information sources, including: stakeholder surveys; results from compliance activity; and internal research, data and trend analysis based on data from income tax returns and third-party external data providers.

3.10 The HOTSA summary of key issues for CGT comprises 12 elements, with accompanying ratings. In July 2014, the HOTSA identified eight of these system elements as being green (basically sound), and four as amber (not fully healthy). The challenges involved with improving third-party data and reporting are identified throughout the HOTSA, including for effective and sustainable design.

3.11 The green ratings in the HOTSA, for CGT outcomes97 have the potential to give rise to a level of complacency among the ATO’s senior executive about the operation of the CGT system that is not supported by the ongoing presence of a high risk rating in the individuals and small business market segments. Given the nature of corporate reporting in the ATO (discussed in paragraph 2.13), senior management would not routinely have visibility of the CGT activities conducted in the SB/IT BSL. A business-as-usual approach over time could also have contributed to the relatively slow improvements to data matching arrangements (discussed in Chapter 4) and a lack of recent evaluations of the effectiveness of voluntary compliance activities for individual taxpayers (discussed in Chapter 5).98

3.12 The 2014 HOTSA outlined areas of the CGT system that remain of concern (an amber rating) to the ATO. These include: effective and sustainable design; the cost to operate the system; and ATO internal capability. The ATO describes the design of the CGT system as mechanical, rather than principal-based legislation, owing to the 53 different CGT events specified in the legislation. This can lead to a fragmented approach to legislative change over time that increases the challenges for the ATO to effectively administer CGT.99 One way the ATO is responding to the challenges for sustainable design is by identifying opportunities to improve legislative design, including through involvement with the Treasury in the development of a Tax White Paper.

3.13 The cost to operate the CGT system, particularly for taxpayers, is of concern to the ATO. For taxpayers, the requirements for complying with CGT can add substantially to the cost of managing their tax affairs. Record keeping can be more extensive for CGT purposes due to both the extent and length of time records are required to be retained for CGT events.100 In 2014–15, the ATO’s focus on voluntary compliance activities is intended to support taxpayers by engaging earlier and informing them about their CGT obligations prior to their lodging an income tax return. The ATO expects these activities to reduce costs for taxpayers.

Internal capability gaps: skills and compliance staff reductions

3.14 Lack of knowledge about specific CGT compliance issues was identified in the 2014 HOTSA for those staff undertaking CGT compliance activity in SB/IT, PGH and PG&I. The ATO advised that it intends to address this capability gap through targeted CGT courses and e-learning modules as well as clearly identifying training needs in team members’ performance development agreements.

3.15 While it is common for skills to be learned in the workplace, CGT training is compulsory for technical staff in SB/IT and PGH with e-learning being the most common delivery mechanism. The ATO’s records show that from March 2011 to September 2014, 626 CGT e-learning courses were completed or accessed by SB/IT staff working with individual taxpayers and small businesses, including external staff (contractors). SBC compliance staff reported: receiving training on-the-job and on site, including visits from trainers; and having access to local technical advice. Those same staff expected to undertake CGT refresher courses in the future. Other SB/IT staff, also involved in administering CGT, identified that mentoring arrangements and e-learning courses were available to support team members.

3.16 At the beginning of 2014–15, SB/IT was subject to a number of structural changes affecting its administration of CGT, particularly a transfer of functions and workforce from SB/IT to PGH, to consolidate management of the Wealthy Australians program from 1 July 2014. The ATO advised that: ‘overall the reduction in staff has been offset by advancements in technology and work practices which have allowed SB/IT to deliver on its revenue commitments to government’.

3.17 While there has been an impact in 2014–15 on work roles and a reduction in the SBC compliance staffing numbers of 17 per cent (from 101 FTE in 2013–14 to 84 FTE in 2014–15), it was too early for this audit to determine the extent of any skills or experience gap in the administration of CGT. However, with less specialist knowledge available in the stream, and a significant reduction in staffing numbers, considerable improvements in staff capability and business processes will be needed to ensure that CGT active compliance interventions are effective. Accordingly, it will be important for the ATO to provide training and support for staff conducting small business CGT compliance activities.

Managing CGT risks within the Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line

3.18 The implementation of CGT risk management in DMCS and SBC is the responsibility of the risk owner (Assistant Commissioner) and the risk managers are responsible for monitoring activities at the operational level.

3.19 As previously noted, the processes for managing CGT compliance risks in SB/IT are supported by a series of documents retained in the ATO’s Enterprise Risk Manager system. To help ensure consistency, these documents are to be completed by BSLs using corporate templates. The minimum set of documents required to support the ATO’s risk management process are a:

- risk assessment—detailed information about the risk, including its drivers, the risk event itself, the consequences and likelihood of the risk and how the level of risk was determined;

- risk treatment plan—detailed information about treatments that can be put in place to reduce the consequence and likelihood of the risk; and

- risk review—evaluates the current status of a risk and whether existing controls and/or treatments are appropriate.

3.20 As part of the risk treatment plan, BSL’s can also complete additional supporting documentation such as a:

- target selection rationale—describes the method and reason for selecting the target population; and

- treatment evaluation—reports the effectiveness of the treatment strategy in relation to the desired outcomes and compliance behaviours.

3.21 Table 3.1 outlines the SB/IT documentation that supports the risk management process for CGT from 2010 to 2014. DMCS prepared the minimum required set of risk documents over the period, while SBC prepared target selection rationales and treatment evaluations, in addition to the standard documents.

Table 3.1: Small Business and Individual Taxpayers Business and Service Line risk documentation for managing capital gains tax risks, 2010 to 2014

|

Risk process documents |

DMSC: Individuals |

SBC: Small business |

|

Risk assessment |

September 2012 |

|

|

Risk treatment plan |

September 2012 |

|

|

Target selection rationale1 |

No documentation |

|

|

Treatment evaluation1 |

No documentation |

|

|

Risk review |

February 2014 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

Note 1: Preparation of these documents is optional.

3.22 The following sections discuss DMCS’ and SBC’s differing approach to risk management and the impact on managing CGT risk in their respective markets.

Risk assessment

3.23 The DMCS and SBC risk assessments for CGT contain similar characteristics for individual and small business taxpayers. Appendix 3 sets out the common features of both risk analyses, including identifying risk events101, risk participants (such as individuals and companies outside the tax system) and risk drivers.102 Overall, the existing risk assessments are consistently documented. Modifications to risk assessments can be informed by analysis from ATO intelligence sources and the results from activities to address non-compliance by taxpayers, such as the results from corresponding with taxpayers and reviews and audits.

New potential risk: small business valuations

3.24 In January 2014, the Government announced that the Australian Valuation Office would cease to provide services by 30 June 2014.103 The ATO considered that this posed a risk that it would be unable to continue the scale of compliance activity involving small business concessions as valuation advice would be more expensive or less readily available.

3.25 The ATO is now using an internal tool (a customised spreadsheet) developed by SBC to assess maximum net asset valuations, as part of treating the small business concessions risk.104 The ATO’s assessments of CGT risks for small business did not however capture the change in organisational structure or reduced capacity to obtain valuations for concessions work.105

Risk treatment and target selection

3.26 The ATO’s target selection rationale documents describe the method and reason for selecting a population that will be subject to the treatment of an identified risk. Therefore, there should be a close alignment between the risk treatment plan and the target selection rationale.

3.27 The 2012 risk treatment plan for individual taxpayers with CGT obligations is consistent with the risk assessment completed at the same time. The target group in the treatment plan is individual taxpayers that have had a capital gains event. More specific target selection rationales were not documented, and the target group is a large, undifferentiated population—all individuals that have had a capital gains event. Instead of focusing on a risk treatment plan, pilot documentation is to be prepared in DMCS when a new risk or data source is identified.106 In light of the strong focus of CGT compliance activity for individual taxpayers on real property transactions (as discussed in Chapter 4), developing targeted selection rationales may assist DCMS to achieve a more balanced coverage of asset types, including shares and other financial transactions that trigger a capital event.

3.28 In contrast, detailed risk treatment plans and target selection rationales107 have been developed (listed in Table 3.1) to address CGT risks for the small business market. The documentation is consistent with the risk assessments, and the target selection rationales include details of the criteria to be used for selecting taxpayer cases for compliance activity that are broadly consistent with the case selection process used for small businesses.108

Treatment evaluation and risk review

3.29 It is important that the risk management process includes an evaluation of how effectively the subsequent compliance activities have met those intended outcomes.

DMCS: individual taxpayer evaluations

3.30 The approach to treatment evaluation differs between the two streams. In DMCS, the absence of risk treatment plans and target selection rationales does not support a formal evaluation process. Instead, the CGT data matching program for individuals is an ongoing program of work and monitoring and evaluation activities are conducted as follows:

- feedback about taxpayer contact, data issues and the general progress of the compliance work program is provided by case identification, selection and actioning teams on a fortnightly basis to the risk manager109; and

- the potential for changes to existing business rules and requirements for matching data are reviewed as the data sets that support compliance activity are refreshed by third-party providers, either three or six monthly depending on the data provider.110

SBC: small business evaluations