Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administering the Character Requirements of the Australian Citizenship Act 2007

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIAC’s administration of the character requirements of the Citizenship Act.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s (DIAC’s) purpose is to build Australia’s future through the well-managed entry and settlement of people. To achieve its purpose, in 2010–11, DIAC had a budget of $2.2 billion and 7284 full time staff located in Australia and overseas.[1]

2. The concept of Australian citizenship was introduced in 1949 and is viewed as a privilege and the desirable culmination of a person’s migration journey. A person may become an Australian citizen automatically or by application. Generally, persons born in Australia to one or more parents who are Australian citizens or permanent residents acquire citizenship automatically. Persons born outside Australia can apply for citizenship in four ways—by descent, adoption, resumption or conferral. Since 1949, over four million people have successfully applied for and become citizens. In 2009–10, 139 167 applications for citizenship were decided and 131 371 applicants acquired citizenship.

3. DIAC is responsible for administering Australian citizenship in accordance with the Australian Citizenship Act 2007 (Citizenship Act), the Australian Citizenship (Transitionals and Consequentials) Act 2007 and the Australian Citizenship Regulations 2007. The Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACIs) support the Citizenship Act and outline DIAC’s policy as it relates to citizenship. To become a citizen by application, applicants must meet eligibility criteria, as outlined in the Citizenship Act, including requirements relating to the applicant’s character.

The good character requirements

4. The Citizenship Act requires that applicants for citizenship satisfy the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (Minister) that they are of good character at the time of a decision on their application. Good character has not been defined, but the ACIs outline the factors that should be considered when assessing character, including:

- type, seriousness and recurrence of criminal behaviour, in Australia and overseas, and the penalty conferred;

- involvement in crimes against humanity;

- length of time between last offence and application for citizenship;

- employment status, community involvement and reputation in the community; and

- stability of family life.

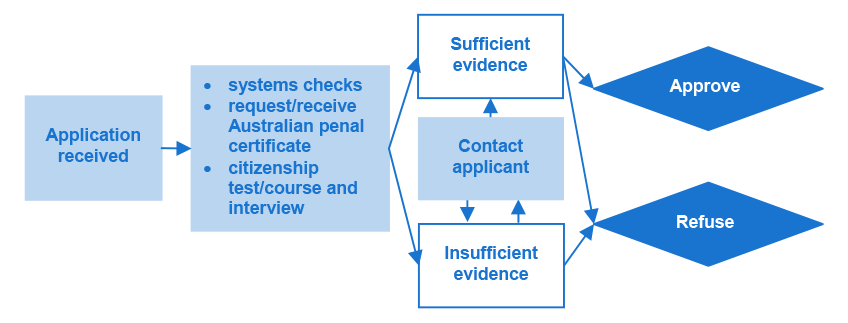

5. Case officers in DIAC’s state, territory, regional and area offices (STOs) have been delegated the authority to assess and decide citizenship applications, including those from applicants of potential character concern. Figure 1 illustrates the key steps in the path from DIAC receiving a citizenship application to its decision whether to approve or refuse citizenship.

Figure S.1: Key steps—citizenship application to approval/refusal

Source: ANAO representation.

6. In the vast majority of cases, DIAC approves the application because the applicant meets the eligibility criteria and the Minister is satisfied that they are of good character. However, in a small number of cases, the Minister was not satisfied that the applicant was of good character and citizenship was refused on the grounds that the person did not meet the good character requirements. Of the 2.5 per cent (3443) of applicants refused citizenship in 2009–10, seven per cent (242) of applicants were refused citizenship on character grounds.

Audit objective and scope

7. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIAC’s administration of the character requirements of the Citizenship Act. Particular emphasis was given to the following areas, as they related to the character requirements:

- policies, guidance and training for staff to support the administration of the character requirements;

- processes to identify clients of character concern, administer cases and make decisions; and

- management arrangements supporting citizenship processing.

8. Concurrent with this audit, the ANAO audited the effectiveness of DIAC’s administration of the character requirements of the Migration Act 1958 (Migration Act). The migration audit (ANAO Audit Report No.55 2010–11, Administering the Character Requirements of the Migration Act 1958) has been tabled as a compendium report to this audit.

Overall conclusion

9. DIAC encourages and facilitates people becoming citizens, enabling them to fully participate in all aspects of Australian life. However, DIAC must balance this objective with the need to maintain the integrity of the Citizenship Act and gain reasonable assurance that applicants granted Australian citizenship meet the eligibility requirements.

10. To be approved for citizenship, the applicant must satisfy the Minister that they are of good character. Of the approximately 140 000 applications DIAC finalises each year, only a small proportion (242 applicants in 2009–10) are refused citizenship on character grounds. While the number of applicants refused citizenship on character grounds was relatively small, it is important that DIAC effectively administer the good character requirements to increase the likelihood that those approved citizenship are of good character and to reduce the risk that persons of significant character concern are granted citizenship.

11. Overall, DIAC has established an appropriate framework for administering the character requirements of the Citizenship Act and to conclude that an applicant is of good character. This framework includes clear roles and responsibilities that are understood by all stakeholders, comprehensive training for decision-makers about the character requirements and sound processes for recording citizenship decisions. DIAC also has satisfactory processes for identifying applicants of potential character concern.

12. However, there are aspects of the implementation of this framework that reduce its effectiveness. These include:

- variability in the application of processes for decision-making by DIAC case officers;

- the term ‘good character’ is not defined, for administrative purposes, in DIAC’s policy and guidance materials; and

- limited interaction between the areas within DIAC that administer the character requirements of the Migration Act and the Citizenship Act in relation to the processing and referral of cases concerning the same client.

13. The variability in the application of processes for decision-making is the result of a number of factors. Citizenship decision-making is decentralised, with most decisions, including character decisions, being made by around 150 junior officers in DIAC’s state and territory offices. Such administrative arrangements place a premium on guidance and training for staff along with effective arrangements to oversee the quality of decision-making. However, the guidance available to decision makers is general and, in some cases, out of date. While citizenship training is comprehensive, it is not mandatory for all decision-makers and attendance has been variable. Input or review of decision making by senior officers also varies, but is generally minimal.

14. The Citizenship Act and relevant guidance do not define ‘good character’. This allows decision-makers considerable discretion when applying the character requirements. In practice, DIAC has focused on criminal convictions when interpreting the character requirements. Other factors that might be relevant to a person’s character, such as general conduct and associations with criminal individuals or groups, are not often considered when identifying applicants of potential character concern. This is, primarily, because reliable evidence to support a decision on these grounds is generally more difficult to obtain and may be less definitive.

15. The separate character requirements of the Migration Act and the Citizenship Act intersect at certain key points. However, there is no policy or protocol to facilitate interaction between the areas within DIAC that administer the character requirements of the Migration Act and the Citizenship Act. This lack of communication and coordination has resulted in uncertainty about how to process persons who have applied for citizenship and who are also being considered for visa cancellation under the Migration Act, and persons refused citizenship on serious character grounds not being referred for character consideration under the Migration Act.

16. DIAC’s administration of the character requirements would be strengthened if the department determined, for administrative purposes, the standards of behaviour it considers acceptable for applicants to meet the good character requirements of the Citizenship Act. Reviewing the guidance materials, mandating the citizenship training program for all decision-makers and implementing a national assessment and decision review process would also contribute to greater consistency in citizenship decision-making. Also, developing a protocol for administering the character requirements of the Migration Act and Citizenship Act would establish a basis for enhanced cooperation between the relevant areas within DIAC and facilitate the more effective processing of DIAC’s visa and citizenship clients. To this end, the ANAO has made three recommendations aimed at improving the effectiveness of DIAC’s administration of the character requirements of the Citizenship Act.

Key findings

Policy, guidance and training

17. Citizenship decision-making, including consideration of an applicant’s character, is decentralised. Case officers in DIAC’s STOs receive, process and decide citizenship applications. In 2009–10, the 187 delegated citizenship decision makers located in STOs made 91 per cent of citizenship decisions. Appropriately, most citizenship decisions are straightforward and are made by junior case officers (usually at the APS 4 level). However, even complex cases that require judgement and discretion, such as those involving character issues, were made by junior case officers with little or no input or review by team leaders or supervisors. DIAC’s guidance does not provide direction to case officers about when to escalate or discuss a case with senior officers and approaches differed between STOs.

18. The Citizenship Act provides the legislative framework for Australian citizenship and includes requirements regarding a citizenship applicant’s character, but it is not prescriptive. The ACIs support the Citizenship Act and outline DIAC’s policy as it relates to the process for granting citizenship. The ACIs are, in turn, supplemented by a Citizenship Processing Manual and Citizenship Helpdesk.

19. The ACIs, which provide high-level policy guidance, are open to interpretation and case officers are unclear about some of the fundamental concepts, including character. Also, despite being a fundamental concept in the Citizenship Act, the ACIs do not define what constitutes ‘good character’ or the behaviour that may indicate that an applicant is or is not of good character.

20. Until it was reissued in May 2011, the Citizenship Processing Manual, which provides operational and systems instructions for processing applications, was out of-date and not endorsed by DIAC’s national office (NatO). The Citizenship Helpdesk provides operational and policy advice to staff. However, very few enquiries relate to the character requirements (less than 0.5 per cent in 2009–10) and case officers did not consider that the Helpdesk provided useful additional advice when processing complex cases requiring the exercise of discretion. The ACIs are also supplemented by an average of two emails a week containing ad hoc policy and operational advice, which is not always disseminated to all case officers.

21. The quality of, and approach to, inducting new officers into citizenship teams varied between and with STOs. By contrast, citizenship training includes sessions on good character and other topics relevant to character, and is provided by NatO officers. In addition, two-thirds of the 24 case officers interviewed by the ANAO expressed positive opinions about the training. However, attendance is not mandatory and 25 per cent of delegated decision makers in STOs have not completed the course, including 21 per cent of junior case officers.

Identifying applicants of character concern

22. To mitigate the risk that persons of character concern are granted citizenship, DIAC seeks to gather a range of information to inform the assessment of these applicants’ character. DIAC employs various approaches to gather that evidence. Applicants are asked to answer questions on the citizenship application form that address character issues. It is not certain, however, that applicants who are not of good character will willingly declare the information. For example, 31 per cent of 104 cases examined by the ANAO that involved applicants with Australian criminal histories, did not declare those histories on their application forms and 24 (73 per cent) of these applicants were refused citizenship. For this reason, DIAC accesses other sources of evidence.

23. DIAC checks departmental information systems, such as the Movement Alert List, to ascertain if the applicant is the subject of an alert. However, an alert will only be raised if the applicant has been previously entered on the system. Finally, DIAC sources Australian and overseas penal certificates (OPCs), where appropriate. The effectiveness of OPCs as a reliable source of character evidence is limited by several factors, including DIAC’s reliance on applicants volunteering information about their overseas travel and aliases, inconsistent approaches across the STOs when administering the OPC requirements, and the questionable reliability of OPCs from some countries.

24. The sources of evidence citizenship case officers collect to identify applicants of character concern focus primarily on criminal activity. They are not likely to uncover evidence of general conduct or association that may also be relevant to a consideration of character. When describing the behaviours that constitute good character, DIAC will need to clarify expectations about the standards of behaviour that are acceptable, including whether the term is expected to include general conduct and associations. The department will also need to provide appropriate guidance to its staff implementing this definition.

Processing and deciding character cases

25. If DIAC has evidence suggesting that a person is not of good character, the case officer contacts the applicant to discuss the character concerns and requests additional information if necessary. Applicants were generally contacted regarding their application and given the opportunity to address any character concerns. However, DIAC’s interaction with applicants varied, between and within STOs, in terms of:

- response periods granted to applicants to provide requested information—one STO granted a response period of 35 days while other STOs generally allowed 28 days;

- the number of times applicants were contacted—applicants refused on character grounds received an average of three requests for information, with 30 per cent of these applicants receiving three or more written follow-up requests for information; and

- the type of information requested from applicants—one STO requires written details about the applicant’s travel outside Australia, while other STOs rely on verbal confirmation of overseas travel.

26. There was also variation in STO’s approaches to reviewing case officers’ work prior to finalising an assessment. Two STOs limit the review of work to that of underperforming case officers, while in another STO supervisors review a sample of all their team members’ work.

27. DIAC has not established a protocol for interaction between citizenship areas and the DIAC’s National Character Consideration Centre (NCCC), which processes visa application and holder character cases under the Migration Act. As a result, staff in these areas are uncertain about the appropriate approach to adopt when processing character cases from the same client. Case officers were unclear about which areas should be processing a client first and practice varied significantly between the STOs.

Making character decisions

28. The Citizenship Act and the ACIs provide non prescriptive, high-level guidance which allows case officers considerable discretion when interpreting the character requirements. When case officers were asked by the ANAO to respond to a number of questions about character cases, they often arrived at different decisions, despite being provided with the same information about an applicant’s character.

29. Under the Citizenship Act, applicants under the age of 18 at the time they lodge their application are not required to meet the good character requirements. Prior to August 2008, the ACIs and materials provided to potential applicants incorrectly stated that the good character requirement applied to applicants 16 years and over. Between May 2007 and May 2008, four applicants under the age of 18 were refused citizenship on character grounds and DIAC had decided that these applicants would not be advised of the incorrect decision made in their cases, nor would their cases be reopened.

30. Decisions to approve or refuse citizenship were recorded in the appropriate DIAC system and, if refused, documented in a decision record. Applicants were advised of the decision in writing. However, there were inconsistencies, within and between STOs, in the way in which applicants were advised of decisions and the format and content of decision records. DIAC is drafting a decision record template for refusals on character grounds that will require case officers to assess applicants against all the eligibility criteria and record that assessment in the decision record. The ANAO noted that case officers do not generally write decision records for approvals, even in cases where the decision was finely balanced and judgement has been exercised.

31. While many applicants refused citizenship on character grounds would not necessitate subsequent consideration by the NCCC for potential cancellation of their visa, a small proportion of citizenship refusal cases do. For example, applicants with serious criminal records and those suspected or found guilty of involvement in crimes against humanity may warrant referral. However, applicants refused citizenship on character grounds, even those refused as a result of serious character concerns, are not routinely referred to the NCCC. For example, the ANAO’s sample of 300 citizenship applications included one applicant with serious driving offences and another with drug offences, both resulting in substantial periods of imprisonment. Neither of these applicants for citizenship were referred to the NCCC for consideration against the character requirements of the Migration Act.

Management arrangements to support citizenship processing

32. DIAC’s suite of planning documents refers to citizenship at the program level and do not specifically identify the character requirements. DIAC’s Strategic Risk Profile 2010–11 mentions citizenship as an element in two risks, which relate to fraud and stakeholder management. The Strategic Risk Profile does not include risks relevant to the character requirements. DIAC’s key performance indicators and external performance reporting also focus on the citizenship program as a whole; no reference is made to the character requirements of the Citizenship Act.

33. To assist it to manage the citizenship caseload, DIAC has developed an internally reported citizenship service delivery standard. The standard focuses on timeliness of processing—80 per cent of citizenship conferral applications decided within 60 days of lodgement. Between 9 November 2007, when a new standard was introduced, and 30 June 2010, 80.3 per cent of applications were decided within 60 days of lodgement. DIAC’s analysis of the citizenship caseload, which is reported internally, focuses on quantitative measures, such as the number of applications received, number of applicants awaiting appointments and citizenship tests, and age of cases. The indicators, standard and data analysis do not measure or report on whether the Australian citizenship program is being delivered effectively in line with Australia’s citizenship law and government policies.

DIAC’s response

34. DIAC provided the following summary response.

35. The Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the ANAO performance audit Administering the Character Requirements of the Australian Citizenship Act 2007 and agrees with the recommendations made in the report. The ANAO report acknowledges that DIAC has in place an appropriate framework for administering the character requirements of the Citizenship Act.

Footnotes

[1] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Portfolio Budget Statements 2010–11, Immigration and Citizenship Portfolio, Budget Related Paper No.1.13, Commonwealth of Australia, May 2010, pp.6, 13, 21, 30, 39, 46, 64 and 72.