Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2018–19 Major Projects Report

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected major projects. The status of the selected major projects is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence. Assurance from the ANAO’s review is conveyed in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General.

Due to the complexity of material and the multiple sources of information for the 2018–19 Major Projects Report, we are unable to represent the entire document in HTML. You can download the full report in PDF or view selected sections in HTML below. PDF files for individual Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSS) are also available for download.

!Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

.

Summary and Review Conclusion

About the Major Projects Report

1. Major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects) continue to be the subject of parliamentary and public interest. This is due to their high cost and contribution to national security, and the challenges involved in completing them within the specified budget and schedule, and to the required capability.

2. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has reviewed 26 of Defence’s Major Projects in this twelfth annual report (2017–18: 26). The Major Projects Report (MPR) reviews overall issues, risks, challenges and complexities affecting Major Projects and also reviews the status of each of the selected Major Projects, in terms of cost, schedule and forecast capability.1 The objective of the report is ‘to improve the accountability and transparency of Defence acquisitions for the benefit of Parliament and other stakeholders.’2

3. The Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) within the Department of Defence (Defence), manages the process of bringing new capabilities into service.3 As at 30 June 2019, Defence was managing 205 active major and minor capital equipment projects worth $132 billion, with an in-year budget of $8.6 billion.4 Defence capitalised some $8.6 billion from these projects in 2018–19.5

4. The February 2016 Defence White Paper established the Australian Government’s priorities for future capability investment for the next 20 years and provided for additional spending of over $29 billion across the next decade. The 2019–20 Defence Portfolio Budget Statements indicated that the Defence budget would grow to approximately $200 billion over the coming decade, for investing in Defence capability.6 The Government commenced its $89 billion investment in Australia’s future shipbuilding industry in April 20177, and on 29 June 2018 announced Second Pass Approval8 of the $35 billion Future Frigate program.9 Further, on 11 February 2019, the Government announced the signing of the Strategic Partnership Agreement10 for the $50 billion Future Submarine program.11

Major Projects selected for review

5. Major Projects are selected for review based on the criteria included in the 2018–19 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).12 They represent a selection of the most significant Major Projects managed by Defence.

6. The total approved budget for the Major Projects included in this report is approximately $64.1 billion, covering 49 per cent of the total budget of active major and minor capital equipment projects of $132 billion.13 The selected projects are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: 2018–19 MPR projects and approved budgets at 30 June 2019 1, 2

|

Project Number (Defence Capability Plan) |

Project Name (on Defence advice) |

Abbreviation (on Defence advice) |

Approved Budget $m |

|

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability 3 |

Joint Strike Fighter |

16,522.6 |

|

|

SEA 4000 Phase 3 |

Air Warfare Destroyer Build 3 |

AWD Ships |

9103.7 |

|

|

AIR 7000 Phase 2B |

Maritime Patrol and Response Aircraft System |

P-8A Poseidon |

5375.7 |

|

|

AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6 |

Multi-Role Helicopter 3 |

MRH90 Helicopters |

3771.1 |

|

|

SEA 1180 Phase 1 |

Offshore Patrol Vessel 3 |

Offshore Patrol Vessel |

3724.3 |

|

|

AIR 5349 Phase 3 |

EA-18G Growler Airborne Electronic Attack Capability |

Growler |

3510.3 |

|

|

LAND 121 Phase 3B |

Medium Heavy Capability, Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers 3 |

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

3399.9 |

|

|

AIR 9000 Phase 8 |

Future Naval Aviation Combat System Helicopter |

MH-60R Seahawk |

3212.5 |

|

|

JP 2048 Phase 4A/4B |

Amphibious Ships (LHD) |

LHD Ships |

3092.2 |

|

|

LAND 121 Phase 4 |

Protected Mobility Vehicle – Light (PMV-L) 3 |

Hawkei |

1979.6 |

|

|

AIR 8000 Phase 2 |

Battlefield Airlift – Caribou Replacement 3 |

Battlefield Airlifter |

1442.1 |

|

|

SEA 1654 Phase 3 |

Maritime Operational Support Capability |

Repl Replenishment Ships |

1070.6 |

|

|

AIR 5431 Phase 3 |

Civil Military Air Management System 3 |

CMATS |

975.8 |

|

|

JP 2072 Phase 2B |

Battlespace Communications System Phase 2B |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B |

942.6 |

|

|

AIR 7403 Phase 3 |

Additional KC-30A Multi-role Tanker Transport |

Additional MRTT |

894.3 |

|

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2B |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

678.7 |

|

|

SEA 1439 Phase 5B2 |

Collins Class Communications and Electronic Warfare Improvement Program |

Collins Comms and EW |

607.8 |

|

|

SEA 3036 Phase 1 |

Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

504.0 |

|

|

JP 9000 Phase 7 |

Helicopter Aircrew Training System |

HATS |

481.6 |

|

|

SEA 1439 Phase 3 |

Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability 4 |

Collins R&S |

445.3 |

|

|

LAND 53 Phase 1BR |

Night Fighting Equipment Replacement |

Night Fighting Equip Repl |

442.6 |

|

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Communications Modernisation |

Maritime Comms |

440.0 |

|

|

JP 2072 Phase 2A |

Battlespace Communications System Phase 2A |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2A |

438.1 |

|

|

SEA 1448 Phase 4B |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl |

428.7 |

|

|

JP 2008 Phase 5A |

Indian Ocean Region UHF SATCOM |

UHF SATCOM |

421.8 |

|

|

JP 2048 Phase 3 |

Amphibious Watercraft Replacement |

LHD Landing Craft |

236.7 |

|

|

Total |

26 |

|

|

64,142.6 |

Note 1: Once a project is selected for review, it remains within the portfolio of projects under review until the JCPAA endorses its removal, normally once it has met the capability requirements of Defence.

Note 2: SEA 1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel, SEA 1439 Phase 5B2 Collins Class Communications and Electronic Warfare Improvement Program, LAND 53 Phase 1BR Night Fighting Equipment Replacement and SEA 1448 Phase 4B ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement are included in the MPR for the first time in 2018–19.

Note 3: These projects have been the subject of individual performance audits. See Table 8 for more information.

Note 4: SEA 1439 Phase 3 Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability is a group of 24 activities primarily sustainment in nature. While not an acquisition project, it has been included at the JCPAA’s request.

Source: The Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 of this report.

7. In September 2019, the JCPAA endorsed project selection for the 2019–20 MPR, including the entry of five new projects.14 The ANAO advised the JCPAA that it proposed to consider the exit of seven projects from the 2018–19 MPR that were expected to reach FOC by the end of 2019 and/or to confirm that only low risk deliverables were remaining.15 Six of these projects are now considered suitable to exit on the basis that they:

- have achieved FOC (SEA 1448 Phase 2B ANZAC ASMD 2B);

- will achieve FOC in December 2019 (JP 2072 Phase 2A Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2A); or

- have provided a pre-FOC risk assessment supporting the timely declaration of FOC (JP 2048 Phase 4A/4B LHD Ships, AIR 7403 Phase 3 Additional MRTT, JP 9000 Phase 7 HATS, and JP 2048 Phase 3 LHD Landing Craft).

8. In the case of one project, AIR 8000 Phase 2 Battlefield Airlifter, the project’s FOC has been delayed and it is not considered to be suitable for exit yet (see paragraph 2.54).

Report objective and scope

9. The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects. The status of the selected Major Projects is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence (see Part 3 of this report) and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence (see Part 3 of this report). Assurance from the ANAO’s review is conveyed in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General (see Part 3 of this report).

10. The following forecast information found in the PDSSs is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review:

- Section 1.2 Current Status—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance and Section 4.1 Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance;

- Section 1.3 Project Context—Major Risks and Issues and Section 5 – Major Risks and Issues; and

- forecast dates where included in each PDSS.

Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information are required to be considered in forming the conclusion.

11. The exclusions to the scope of the review, noted above, are due to a lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence16 in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review. This has been an area of focus of the JCPAA over a number of years17, and it is intended that all components of the PDSSs will eventually be included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

12. Separate to the formal review, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of key elements of the PDSSs — including cost, schedule, progress towards delivery of required capability, project maturity, and risks and issues. Longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects has also been undertaken.

13. Defence provides further insights and context in its commentary and analysis. This commentary and analysis is not included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

Review methodology

14. The ANAO has reviewed the PDSSs prepared by Defence as a priority assurance review under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997. The criteria to conduct the review are provided by the Guidelines approved by the JCPAA, and include whether Defence has procedures in place designed to ensure that project information and data was recorded in a complete and accurate manner, for all 26 projects.

15. The review included an assessment of Defence’s systems and controls, including the governance and oversight in place, to ensure appropriate project management. The ANAO also sought representations and confirmations from Defence senior management and industry in relation to the status of the Major Projects in this report.

Report structure

16. The report is organised into four parts:

- Part 1 comprises the ANAO’s review and analysis (pp. 1–66);

- Part 2 comprises Defence’s commentary, analysis and appendices (not included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General) (pp. 67–122);

- Part 3 incorporates the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, and the PDSSs prepared by Defence as part of the assurance review process (pp. 123–398); and

- Part 4 reproduces the 2018–19 Major Projects Report Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA, which provide the criteria for the compilation of the PDSSs by Defence and the ANAO’s review (pp. 399–426).

Figure 1, below, depicts the four parts of this report.

Figure 1: 2018–19 Report structure

Note: To assist in conducting inter-report analysis, the presentation of data in the PDSSs remains largely consistent and comparable with the 2017–18 MPR.

Project Data Summary Sheets

17. The PDSSs include unclassified information on project performance, prepared by Defence.18 As projects appear in the MPR for multiple years, changes to the PDSS from the previous year are depicted in bold orange text in the PDSS.

18. Each PDSS comprises:

- Project Header: including name; capability and acquisition type; Capability Manager; approval dates; total approved and in-year budgets; stage; complexity; and an image;

- Section 1—Project Summary: including description; current status including financial assurance and contingency statement; and context, including background, uniqueness, major risks and issues, and other current sub-projects;

- Section 2—Financial Performance: including budgets and expenditure; variances; and major contracts in place (in addition to quantities delivered as at 30 June 2019);

- Section 3—Schedule Performance: providing information on design development; test and evaluation; and forecasts and achievements against key project milestones, including Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR)19, Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC)20;

- Section 4—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance: provides a summary of Defence’s assessment of its expected delivery of key capabilities, the extent to which milestones were achieved (particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones), and a description of the constitution of each key milestone;

- Section 5—Major Risks and Issues: outlines the major risks and issues of the project and remedial actions undertaken for each;

- Section 6—Project Maturity: provides a summary of the project’s maturity, as defined by Defence21, and a comparison against the benchmark score;

- Section 7—Lessons Learned: outlines the key lessons that have been learned at the project level (further information on lessons learned by Defence are included in Defence’s Appendix 2 in Part 2 of this report); and

- Section 8—Project Line Management: details current project management responsibilities within Defence.

Overall outcomes

Statement by the Secretary of Defence

19. The Statement by the Secretary of Defence was signed on 10 December 2019. The Acting Secretary’s statement provides her opinion that the PDSSs for the 26 selected projects ‘comply in all material respects with the Guidelines and reflect the status of the projects as at 30 June 2019’.

20. In addition, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence details significant events occurring post 30 June 2019, which materially impact the projects included in the report, and which should be read in conjunction with the individual PDSSs. These include: Joint Strike Fighter, P-8A Poseidon, MRH90 Helicopters, Offshore Patrol Vessel, Growler, LHD Ships, Hawkei, Battlefield Airlifter, Repl Replenishment Ships, CMATS, Additional MRTT, Collins Comms and EW, Night Fighting Equip Repl, Maritime Comms, ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl, UHF SATCOM, and LHD Landing Craft.

21. The 2018–19 MPR Guidelines require Defence to report in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence on projects which have been removed from the MPR which still have outstanding caveats. Defence has not reported any outstanding caveats in the 2018–19 Statement by the Secretary of Defence.

Conclusion by the Auditor-General

22. The Auditor-General has concluded in the Independent Assurance Report for 2018–19 that ‘nothing has come to my attention that causes me to believe that the information in the 26 Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 (PDSSs) and the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, excluding the forecast information, has not been prepared in all material respects in accordance with the 2018–19 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.’

23. Additionally, in 2018–19, a number of observations were made in the course of the ANAO’s review, as summarised below:

- Defence is unable to provide point-in-time data on project personnel numbers and costs. See further explanation in paragraphs 1.53 to 1.55;

- instances of a lack of oversight, non-compliance with corporate guidance and the use of spreadsheets in the management of risks and issues (Section 5 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.56 to 1.6222;

- outdated policy guidance for the project maturity framework (Section 6 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.63 to 1.6723; and

- an increase in the number of MPR projects which have achieved significant milestones with caveats. See further explanation in paragraphs 1.68 to 1.73.

ANAO’s analysis of project performance

24. As discussed, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of key elements of the Defence PDSSs — cost, schedule, progress towards delivery of required capability, project maturity, risks and issues, and longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects. Table 2 provides: summary data on Defence’s progress toward delivering the capabilities for the Major Projects covered in this report; and compares current data against that reported in previous editions of the MPR. This section also contains a summary analysis of the three principal components of project performance: cost, schedule and capability.

Table 2: Summary longitudinal analysis1

|

|

2016–17 MPR |

2017–18 MPR |

2018–19 MPR |

|

Number of Projects |

27 |

26 |

26 |

|

Total Approved Budget at 30 June |

$62.0 billion |

$59.4 billion |

$64.1 billion |

|

Total Approved Budget at final Second Pass Approval |

$53.5 billion |

$50.2 billion |

$53.9 billion |

|

Total Expenditure Against Total Approved Budget |

$32.1 billion (51.7%) |

$32.4 billion (54.5%) |

$36.3 billion (56.6%) |

|

Total In-year Expenditure Against In-year Budget |

$4.1 billion (96.6%) |

$4.6 billion (98.6%) |

$4.8 billion (93.4%) |

|

Total Budget Variation since initial Second Pass Approval 2 |

$22.3 billion (36.0%) |

$23.0 billion (38.7%) |

$24.4 billion (38.0%) |

|

Total Budget Variation since final Second Pass Approval 3 |

$8.5 billion (13.7%) |

$9.2 billion (15.5%) |

$10.2 billion (15.9%) |

|

In-year Approved Budget Variation |

-$1.6 billion (-2.6%) |

-$0.3 billion (-0.5%) |

$1.2 billion (1.9%) |

|

Total Schedule Slippage 4 |

793 months (29%) |

801 months (32%) |

691 months (27%) |

|

Average Schedule Slippage per Project |

30 months |

32 months |

27 months |

|

In-year Schedule Slippage 5 |

149 months (6%) |

104 months (5%) |

108 months (5%) |

|

Total Project Maturity 6 |

1531 / 1890 (81%) |

1484 / 1820 (82%) |

1485 / 1820 (82%) |

|

Total Reported Risks and Issues 7, 8 |

136 |

138 |

138 |

|

Expected Capability (Defence Reporting)

|

98% |

99% |

99% |

|

2% |

1% |

1% |

|

0% 9 |

0% |

0 10 |

Refer to paragraphs 24 to 39 in Part 1 of this report.

Note 1: The data for the 26 Major Projects in the 2018–19 MPR compares the data from projects in the 2017–18 MPR and 2016–17 MPR. The Major Projects included within each MPR are based on entry and exit criteria in the Guidelines, which have been included in Part 4 of this report. The entry and exit of projects should be considered when comparing data across years.

Note 2: Where a project has multiple Second Pass Approvals (see footnote 8), the MPR has historically reported budget variations from the initial Second Pass Approval. The figures in this row are consistent with prior year reporting. See Table 3 for a breakdown of the major components of this variance, and Table 8 for all real variations.

Note 3: In the 2017–18 and 2018–19 PDSSs, where a project has multiple Second Pass Approvals, the budget at Second Pass Approval reported in the Header refers to the total budget as at the final Second Pass Approval. The figures in this row use this methodology.

Note 4: Slippage refers to the difference between the original government approved date and the current forecast date. Slippage can occur due to late delivery, increases in scope or at times can be a deliberate management decision. These figures exclude schedule reductions over the life of the project. However, paragraph 2.43 reports total schedule reductions over the life of the projects.

Note 5: Based on the 25 repeat projects from the 2015–16 MPR plus one new project (CMATS) that had slippage in 2016–17, 23 repeat projects from the 2016–17 MPR, and 22 repeat projects from the 2017–18 MPR respectively.

Note 6: The figures represent the total of the reported maturity scores divided by the total benchmark maturity score, in the PDSSs across all projects.

Note 7: The grey section of the table is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s priority assurance review, due to a lack of systems from which to obtain complete and accurate evidence in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review.

Note 8: The figures represent the combined number of open high and extreme risks and issues reported in the PDSSs across all projects. Risks and issues may be aggregated at a strategic level.

Note 9: Defence advised in this year that Joint Strike Fighter would not deliver one element of capability at FOC (which equated to approximately one per cent). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Note 10: Defence advised in this year that AWD Ships would not deliver one element of capability at FOC (which equated to approximately one per cent). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Cost

25. Cost management is an ongoing process in Defence’s administration of the Major Projects. While all projects reported that they could continue to operate within the total approved budget of $64.1 billion, MRH90 Helicopters, Repl Replenishment Ships, and Battle Comm. Sys (Land) 2B were required to draw upon contingency funds to complete project activities.

26. The approved budget for Major Projects included in this MPR has increased by $24.4 billion (38.0 per cent) since initial Second Pass Approval. Budget variations greater than $500 million are detailed in Table 3, below.24 However, as the MPR predominantly focusses on the approved capital budget for acquisition, the ongoing costs of Project Offices25, training, replacement capability, etc., are not reported here.

Table 3: Budget variation over $500m post initial Second Pass Approval by variation type 1, 2

|

Project |

Variation Type |

Explanation |

Year |

Amount $b |

|||

|

Scope Increases |

14.1 |

||||||

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

|

34 additional aircraft at Phase 4/6 Second Pass Approval |

2005–06 |

2.3

|

|||

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

|

58 additional aircraft at Stage 2 Second Pass Approval |

2013–14 |

10.5

|

|||

|

P-8A Poseidon |

|

Four additional aircraft |

2015–16 |

1.3

|

|||

|

Real Cost and other Increases |

1.8 |

||||||

|

AWD Ships |

|

Real Cost Increase of $1.2b offset by $0.1b transfer for facilities in 2014 |

2013–14 and 2015–16 |

1.1

|

|||

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

|

Project supplementation3 ($684.2m) and additional vehicles, trailers and equipment ($28.0m) at Revised Second Pass Approval |

2013–14 |

0.7

|

|||

|

Other budget movements |

1.3 |

||||||

|

Other |

Scope increase/budget transfers (net) |

Other scope changes and transfers |

Various |

1.3

|

|||

|

Price Indexation – materials and labour (net) (to July 2010) 4

|

2.8 |

||||||

|

Exchange Variation – foreign exchange (net) (to 30 June 2019)

|

4.4 |

||||||

|

Total |

24.4 |

||||||

Note 1: For the variations related to all projects and values refer to Table 8 of this report. For the breakdown of in-year variation, refer to Table 9 of this report.

Note 2: For projects with multiple Second Pass Approvals, this table shows variations from the initial approval.

Note 3: Defence has advised that ‘project supplementation’ is a unique term used to describe the approvals history of this project as follows: ‘The original amount of $2549.2, was the Government decision to split Phase 3 into Phase 3A and 3B. In 2011, Government approved Second Pass approval of Phase 3A and the ‘Interim Pass’ Government approval for Phase 3B. The decision to grant Phase 3B ‘Interim Pass’ was to allow greater bargaining power for Defence while negotiating Phase 3A. Phase 3B was always going to return to Government for formal Second Pass approval, which occurred in July 2013, once contract negotiations were complete.’

Note 4: Prior to 1 July 2010, projects were periodically supplemented for price indexation, whereas the allocation for price indexation is now provided for on an out-turned basis at Second Pass Approval.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2018–19 PDSSs.

Schedule

27. Delivering Major Projects on schedule continues to present challenges for Defence, affecting when the capability is made available for operational release and deployment by the Australian Defence Force, as well as the cost of delivery.

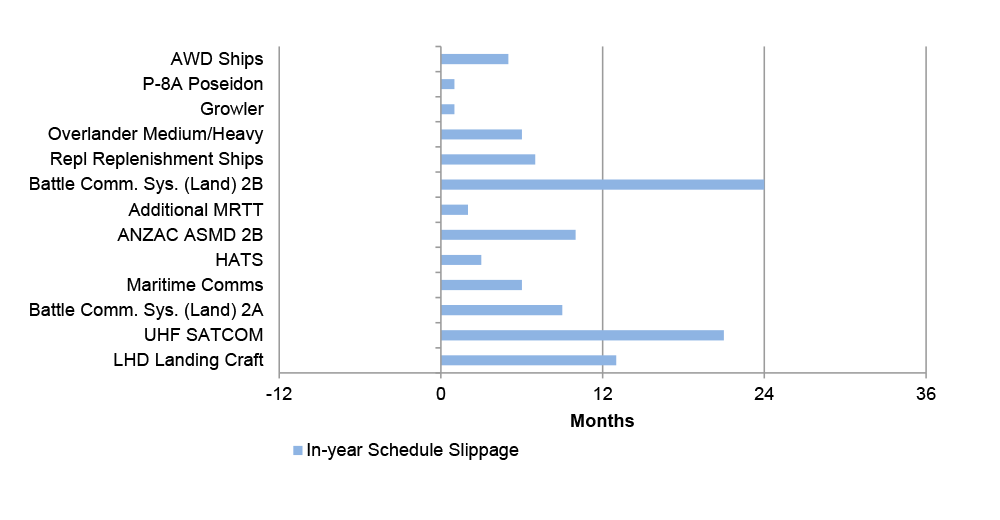

28. The total schedule slippage for the 26 selected Major Projects, as at 30 June 2019, is 691 months when compared to the initial schedule.26 This represents a 27 per cent increase since Second Pass Approval. Across MPR projects that have experienced slippage (21 of 26 projects), the average slippage is 32.9 months (2.7 years). Table 4 below includes details of in-year and total schedule slippage by project. The table shows an increase of 108 months of in-year slippage during 2018–19.

29. The total slippage of 691 months in 2018–19 is 110 months lower than the total in 2017–18 of 801 months. This is due to:

- the removal of completed projects (Collins RCS, Hw Torpedo, ANZAC ASMD 2A and Battle Management System) removing 254 months of slippage from the total reported in 2017–18 (see Table 5);

- the addition of 108 months of in-year slippage described above; and

- the Collins Comms and EW project adding 36 months of slippage to the total of 691 months; the slippage occurred in 2016–17 but the project was reported in the MPR for the first time in 2018–19.

Table 4: Schedule slippage from original planned Final Operational Capability 1

|

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

|

Joint Strike Fighter 2 |

0 |

2 |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B |

24 |

24 |

|

AWD Ships |

5 |

40 |

Additional MRTT |

2 |

23 |

|

P-8A Poseidon |

1 |

29 |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

10 |

77 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

0 |

89 |

Collins Comms and EW |

0 |

36 |

|

Offshore Patrol Vessel |

0 |

0 |

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

0 |

2 |

|

Growler |

1 |

2 |

HATS |

3 |

3 |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

6 |

11 |

Collins R&S |

0 |

112 |

|

MH-60R Seahawk |

0 |

0 |

Night Fighting Equip Repl |

0 |

0 |

|

LHD Ships 2 |

0 |

37 |

Maritime Comms |

6 |

13 |

|

Hawkei 2 |

0 |

0 |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2A |

9 |

39 |

|

Battlefield Airlifter |

0 |

24 |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl |

0 |

0 |

|

Repl Replenishment Ships 2,3 |

7 |

7 |

UHF SATCOM 2 |

21 |

42 |

|

CMATS 2 |

0 |

28 |

LHD Landing Craft |

13 |

51 |

|

Total (months) |

108 |

691 |

|||

|

Total (%) |

5 |

27 |

|||

Note 1: Refer to footnote 25.

Note 2: These projects have been identified by Defence as Projects of Interest (see paragraph 1.23 in Part 1).

Note 3: Slippage for this project is reflective of movement from a forecast of May 2022 in 2017–18, to a forecast of December 2022 in 2018–19. While the forecast of December 2022 remains within the window for FOC achievement approved by Government, the previous forecast of May 2022 was approved by this project’s line management. See paragraph 2.45.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2018–19 PDSSs.

30. Platform availability has contributed to the slippage experienced within some projects. For example, Maritime Comms and Collins R&S have been impacted by changes to docking schedules of the Anzac Class frigates and Collins Class submarines respectively. Significant delays have also been experienced by those projects with the most developmental content: AWD Ships, MRH90 Helicopters, CMATS and Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B. Additionally, delays to operational test and evaluation activities have led to delays to the LHD Ships and LHD Landing Craft projects.

31. Table 5, below, provides details of total schedule slippage by project, for projects which have exited the MPR. Compared to the 691 months total schedule slippage for the current 26 Major Projects, the 22 projects which have exited the MPR have reported accumulated schedule slippage of 953 months, as at their respective exit dates. Table 5 indicates that schedule slippage for projects which have exited the MPR was more pronounced in projects with the most developmental content.

Table 5: Schedule slippage for projects which have exited the MPR 1

|

Project |

Total (months) |

Project |

Total (months) |

|

Wedgetail (Developmental) |

78 |

HF Modernisation (Developmental) |

147 |

|

Super Hornet (MOTS) |

0 |

Armidales (Australianised MOTS) |

45 |

|

Hornet Upgrade (Australianised MOTS) |

39 |

Collins RCS (Australianised MOTS) |

109 |

|

ARH Tiger Helicopters (Australianised MOTS) |

82 |

Hw Torpedo (MOTS) |

63 |

|

C-17 Heavy Airlift (MOTS) |

0 |

SM-2 Missile (Australianised MOTS) |

26 |

|

Air to Air Refuel (Developmental) |

64 |

ANZAC ASMD 2A (Australianised MOTS) |

82 |

|

FFG Upgrade (Developmental) |

132 |

155mm Howitzer (MOTS) |

7 |

|

Bushmaster Vehicles (Australianised MOTS) |

1 |

Stand Off Weapon (Australianised MOTS) |

37 |

|

Overlander Light (Australianised MOTS) |

9 |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Australianised MOTS) |

24 |

|

Next Gen Satellite 2 (MOTS) |

0 |

C-RAM (MOTS) |

2 |

|

Additional Chinook (MOTS) |

6 |

|

|

|

Total |

953 |

||

Note 1: The Hornet Refurb and Battle Management System (BMS) projects are not included in this table as they did not have FOC milestones.

Note 2: Next Gen Satellite shows slippage in Figure 8, which related to the final capability milestones at the time. By the time it reached FOC, a new final capability milestone had been introduced and slippage was reduced.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

32. Additional ANAO analysis (refer to Figure 7, on page 54) has compared project slippage against the Defence classification of projects as Military Off-The-Shelf (MOTS), Australianised MOTS or developmental. These classifications are a general indicator of the difficulty associated with the procurement process.

33. Figure 8 (on page 55) provides analysis of projects either completed, or removed from the MPR review, and shows that a focus on MOTS27 acquisitions has assisted in reducing schedule slippage. Prima facie, the more developmental in nature a project is, the more likely it will result in a greater degree of project slippage. Figure 8 was requested by the JCPAA in May 2014.28

34. Longitudinal analysis indicates that while the reasons for schedule slippage vary, it primarily reflects the underestimation of both the scope and complexity of work, particularly for Australianised MOTS and developmental projects (see paragraphs 2.31 to 2.37).

Capability

35. The third principal component of project performance examined in this report is progress towards the delivery of capability required by government. While the assessment of expected capability delivery by Defence is outside the scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, it is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of the three principal components of project performance.

36. The Defence PDSSs report that 20 projects in this year’s report will deliver all of their key capability requirements. Defence’s assessment indicates that some elements of the capability required may be ‘under threat’, but the risk is assessed as ‘manageable’. The five project offices experiencing challenges with expected capability delivery (2017–18: three) are Joint Strike Fighter, MRH90 Helicopters, Hawkei, Battlefield Airlifter and LHD Landing Craft. One project office (AWD Ships) reports that it is unable to deliver all of the required capability by FOC.

37. Defence’s presentation of capability delivery performance in the PDSSs is a forecast and therefore has an element of uncertainty. In 2015–16, the ANAO developed an additional measure of the status of current capability delivery progress to assist the Parliament — Capability Delivery Progress — which is a tally of the capability delivered as at 30 June 2019, as reported by Defence. Table 6 below provides a worked example of the ANAO’s methodology, utilising the performance information provided in the relevant PDSS.

Table 6: Capability Delivery Progress assessment — Additional MRTT (multi-role tanker transport)

|

Capability elements as per Section 4.2 of the PDSS |

No. of elements approved |

No. of elements delivered at 30 June 2019 |

Comments |

|

Delivery of first aircraft, and delivery of initial spares and support equipment (IMR) |

2 |

2 |

First aircraft and initial spares delivery completed. |

|

Delivery of second aircraft, delivery of remaining spares and support equipment, and delivery of Aircraft Stores Replenishment Vehicle (FMR) |

3 |

2 |

Second aircraft and remaining spares and support equipment delivery completed. Aircraft Stores Replenishment Vehicle yet to be delivered. |

|

Total (number) |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Total (%) |

100 |

80 |

|

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

38. Table 7 below, summarises expected capability delivery as at 30 June 2019 — as reported by Defence and using the ANAO’s Capability Delivery Progress measure.

Table 7: Capability delivery

|

Expected Capability (Defence Reporting) |

2016–17 MPR (%) |

2017–18 MPR (%) |

2018–19 MPR (%) |

Capability Delivery Progress (ANAO Analysis) |

2018–19 MPR (%) |

2018–19 MPR (%) Adjusted 3 |

|

High Confidence (Green) |

98 |

99 |

99 |

Delivered |

67 |

54 |

|

Under Threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Not yet delivered |

33 |

46 |

|

Unlikely (Red) |

0 1 |

0 |

0 2 |

Not delivered at FOC |

0 2 |

0 2 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Total |

100 |

100 |

Note 1: Defence advised in this year that Joint Strike Fighter would not deliver one element of capability at FOC (which equated to approximately one per cent of elements required). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero.

Note 2: Defence advised in this year that AWD Ships would not deliver one element of capability at FOC (which equates to approximately one per cent of elements required). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounds to zero.

Note 3: While the left-hand column reports the total percentage of elements delivered across all 26 Major Projects, the right-hand adjusted column reports the average percentage of elements delivered per project. This adjustment results in an analysis where all projects have equal weight and the percentage is not affected by the numbers of deliverables per project.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

39. In addition to reporting on expected capability delivery, Defence has continued the practice of including in the PDSSs declassified information on settlement actions for projects, including stop payments and liquidated damages. During 2018–19, Hawkei, Pacific Patrol Boat Repl, and UHF SATCOM had negotiated contractual settlements involving stop payments or liquidated damages. Prior settlements for projects within this report related to MRH90 Helicopters, LHD Ships and Maritime Comms.

1. The Major Projects Review

1.1 This chapter provides an overview of the scope and approach adopted by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) for the review of the 26 Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by the Department of Defence (Defence). This chapter also provides the results of the Major Projects Report (MPR) review.

Review scope and approach

1.2 In 2012 the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) identified the review of the PDSSs as a priority assurance review, under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). This provided the ANAO with full access to the information gathering powers under the Act. The ANAO’s review of the individual project PDSSs, which are reproduced in Part 3 of this report, was conducted in accordance with the auditing standards set by the Auditor-General under section 24 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 through its incorporation of the Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements (ASAE) 3000 Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information, issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

1.3 The following forecast information is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review: capability delivery, risks and issues, and forecast dates. These exclusions are due to the lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence29, in a sufficiently timely manner to complete the review. Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information, are required to be considered in forming the conclusion.

1.4 The ANAO’s work is appropriate for the purpose of providing an Independent Assurance Report in accordance with the above auditing standard. However, the review of individual PDSSs is not as extensive as individual performance and financial statement audits conducted by the ANAO, in terms of the nature and scope of issues covered, and the extent to which evidence is required by the ANAO. Consequently, the level of assurance provided by this review, in relation to the 26 major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects), is less than that provided by the ANAO’s program of audits.

1.5 Separately, the ANAO undertakes analysis of key elements of the PDSSs and examines systemic issues and provides longitudinal analysis for the 26 projects reviewed.

1.6 The review was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $2.2 million.30

Review methodology

1.7 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the individual PDSSs included:

- examination and assessment of the governance and oversight in place to ensure appropriate project management;

- an assessment of the systems and controls that support project financial management, risk management and project status reporting, within Defence;

- an examination of each PDSS and the documents and information relevant to them;

- a review of relevant processes and procedures used by Defence in the preparation of the PDSSs;

- discussions with persons responsible for the preparation of the PDSSs and management of the projects;

- analysis of project information, for example, cost and schedule variances;

- taking account of industry contractor comments provided on draft PDSS information;

- assessing the assurance by Defence managers attesting to the accuracy and completeness of the PDSSs;

- examination of the representations by the Chief Finance Officer supporting the project financial assurance and contingency statements;

- examination of confirmations, provided by the Capability Managers, relating to each project’s progress toward Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR), Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC); and

- examination of the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, including significant events occurring post 30 June, and management representations by the Secretary of Defence.

1.8 The ANAO’s review of PDSSs also focused on project management and reporting arrangements contributing to the overall governance of the Major Projects. The ANAO considered:

- developments in acquisition governance (see paragraphs 1.10 to 1.32, below);

- the financial framework, particularly as it applies to the project financial assurance and contingency statements, and Defence’s advice that project financial reporting during 2018–19 would be prepared on the same basis as project approvals and expenditure represented in the Portfolio Budget Statements and the Defence Annual Report (i.e. on a cash basis) (Section 2 of the PDSSs);

- schedule management and test and evaluation processes (Section 3 of the PDSSs);

- capability assessments, including Defence statements of the likelihood of delivering key capabilities, particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones (Section 4 of the PDSSs);

- the ongoing reform process for Defence’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework, and the completeness and accuracy of major risk and issue data (Section 5 of the PDSSs);

- the project maturity framework along with its related reporting and the systems in place to support the consistent and accurate application and the provision of this data (Section 6 of the PDSSs); and

40. the impact of acquisition issues on sustainment to ensure the PDSS is a complete and accurate representation of the acquisition project.

1.9 This review informed the ANAO’s understanding of the systems and processes supporting the PDSSs for the 2018–19 review period. It also highlighted issues in those systems and processes that warrant attention.

Acquisition governance

1.10 Consistent with previous years, the ANAO considered Defence’s acquisition governance processes when planning and conducting review for the 2018–19 MPR. While some of these processes are now established, others continue to mature or require further development to achieve their intended impact.

Defence Independent Assurance Reviews

1.11 The Defence Independent Assurance Review process provides the Defence Senior Executive with assurance that projects and products will deliver approved objectives and are prepared to progress to the next stage of activity. Reviews allow early identification of problem projects and products, facilitating their timely recovery.31, 32

1.12 Formerly called Gate Reviews, Independent Assurance Reviews are intended to be conducted at key acquisition and sustainment ‘gates’ in the Capability Life Cycle.33

1.13 Twenty of the 26 projects included in this report had an Independent Assurance Review conducted during 2018–1934, which formed key corroborative evidence for the ANAO’s review.

Projects of Concern

1.14 The Projects of Concern process is intended to focus the attention of the highest levels of government, Defence and industry on remediating problem projects. The process has continued to play a role across the portfolio of MPR projects.35 As at 30 June 2019, one MPR project, MRH90 Helicopters, was a continuing Project of Concern. The project was placed on the list in November 2011 due to contractor performance relating to significant technical issues preventing the achievement of milestones on schedule.36

1.15 Auditor-General Report No.31 2018–19, Defence’s Management of its Projects of Concern, assessed whether the Department of Defence’s Projects of Concern regime was effective in managing the recovery of underperforming projects. It concluded that, while the regime is an appropriate mechanism for escalating troubled projects to the attention of senior managers and ministers, Defence was not able to demonstrate the effectiveness of its regime in managing recovery of underperforming projects. Moreover, the audit observed that the transparency and rigour of the framework’s application has declined in recent years. The audit recommended that:

- Recommendation no.1: Defence introduce, as part of its formal policy and procedures, a consistent approach to managing entry to, and exit from, its Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern lists. This should reflect Defence’s risk appetite and be made consistent with the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Risk Model and other, Defence-wide, frameworks for managing risk. To aid transparency, the policy and the list should be made public.

- Recommendation no.2: Defence evaluates its Projects of Concern regime.37

Defence has agreed to implement these recommendations. It has advised that the Project Risk Management System (PRMS) being developed as part of the risk reform should provide a consistent approach for entry into and exit from the Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern Lists. Defence advised that it intends for this recommendation to be implemented by March 2020 but notes that this will depend on progress in implementing the CASG Risk reform (see paragraphs 1.56 to 1.62)

1.16 In relation to Recommendation 2, Defence has advised that CASG’s Project Management Branch will analyse Projects of Concern to understand the root cause of project performance. Defence has also advised that lessons will be published, communicated and used to treat systemic issues in project practice and performance, including the training and skilling of project management. The CASG Project Management Branch will assess the contribution of the Projects of Concern regime to managing the recovery of underperforming projects.

1.17 The ANAO will continue to monitor Defence’s implementation of the recommendations and report on progress in the next MPR.

Quarterly Performance Report

1.18 The Defence Quarterly Performance Report (QPR) aims to provide senior stakeholders within government and Defence with insight into the delivery of major capability to the Australian Defence Force.38 The report is provided to the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Defence Industry on a quarterly basis.39

1.19 In July 2019, the ANAO completed an audit on the effectiveness of the QPR in providing senior stakeholders with accurate and timely information on the status and emerging risks and issues. It found the June 2018 QPR, reviewed by the ANAO, to be largely effective, contained mostly accurate information, and was valued by senior stakeholders.40 The ANAO recommended that Defence improve the QPR as a tool for senior leaders by reporting on:

- trend performance data for sustainment products; and

- emerging candidates for the Projects/Products of Concern list and Products/Projects of Interest list that have been recommended by an Independent Assurance Review or which are under active consideration by senior management.41

1.20 In the course of its review for the 2018–19 MPR, the ANAO observed that Defence’s June 2019 QPR reported on both improved and deteriorated performance for both acquisition and sustainment products since the previous QPR.42 This reflects a change in trend reporting consistent with the agreed ANAO recommendation.

1.21 The ANAO also observed as part of its review that Defence’s June 2019 QPR reported the emerging candidates for the Projects/Products of Concern list and Products/Projects of Interest list which had been recommended either by an IAR or which were under active consideration. This change was also consistent with the agreed ANAO recommendation.43

1.22 The ANAO examines QPRs as part of the procedures for its limited assurance review of Defence’s PDSSs.44 For the 2018–19 review, the ANAO examined the five QPRs from September 2018 to September 2019.45

1.23 The June 2019 QPR identified six MPR projects as Projects of Interest46:

- Joint Strike Fighter, noting risks related to affordability and IOC and FOC deliverables47;

- LHD Ships, due to ongoing operational testing, a large number of outstanding requirements, defects and deficiencies, and an immature support system48;

- Hawkei, due to risks to capability and schedule that relate to ongoing reliability issues, design maturity, and production delays caused by the voluntary administration of the engine manufacturer (Steyr Motors)49;

- Repl Replenishment Ships (Maritime Operational Support Capability), due to a change in delivery strategy with the prime contractor, which caused significant schedule changes, and deficiencies in the Integrated Logistics Support system50;

- Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS), noting risks to schedule due to execution of design milestones and poor scope definition, and ongoing contract negotiations51; and

- UHF SATCOM, due to delays in contract negotiation, software development and US Government certification. In the March 2019 QPR, the entire JP2008 program was identified as a Program of Interest, which is inclusive of UHF SATCOM.52

1.24 These ongoing issues for the Joint Strike Fighter, LHD Ships, Hawkei, Repl Replenishment Ships, CMATS, and UHF SATCOM projects align with the results of the ANAO’s review of the PDSSs. Delays to progress have impacted the delivery schedule of Hawkei, Repl Replenishment Ships, and UHF SATCOM during 2018–1953 (see Table 4, on page 15).

Project Directives and Materiel Acquisition Agreements

1.25 Project Directives (previously known as Joint Project Directives) state the terms of government approval, reflecting the approved scope and timeframes for activities, responsibilities and resources allocated, and key risks and issues.54 Project Directives are used to inform internal Defence documentation such as Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs) between Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) and the Service Chiefs.55, 56 Project Directives are a key governance document under the Capability Life Cycle57, intended to ensure that all parties in Defence are informed of Government decisions. The ANAO has previously highlighted the importance of ensuring that Project Directives properly reflect the relevant Government decision, and that MAAs are appropriately aligned with the relevant Project Directive.58

1.26 In some cases Project Directives have been finalised after the MAAs they are intended to inform and, as a result, care is required to ensure that Project Directives properly reflect the relevant government decision, and that MAAs are appropriately aligned with the relevant Project Directive. The mechanism for providing the directive is via the Capability Lifecycle (CLC) Management Tool, which records the Government decision in relation to a project. In some cases, the Joint Force Authority may provide a specific documented directive. For all four new projects entering the 2018–19 MPR, it was not clear whether the projects had their Project Directive signed prior to the MAA. These projects either did not have a specific documented Project Directive, or were unable to access the CLC Management Tool at the time of the ANAO site visits. Project Directives are a requirement of the Interim CLC Manual59, and their production increases the likelihood of complying with government decisions.

1.27 The ANAO requires access to original approval documents to validate the requirements of projects. At this time, validation based on internal Defence documentation is not always possible.

1.28 The ANAO will continue to take Project Directives into account as part of its review. The extent to which they can be relied upon will be dependent on the completeness and accuracy of Project Directives, in relation to recording the detail of government approvals.

1.29 Product Delivery Agreements (PDAs)60 were being developed to replace the existing MAAs and Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs). Defence has advised the ANAO that this initiative has not progressed.

Business systems

1.30 Defence continues to review its business systems with the aim of consolidating processes and systems in order to provide a more manageable system environment. As reported to the JCPAA on 31 March 2017, Defence stated that there was a ‘need to get a single unified system of accountability and reporting inside the organisation’.61 During 2018–19, and at the time of this report, the Monthly Reporting System (MRS), which provides much of the data for the PDSSs, remains in place. Defence has advised that an update to the MRS, which may be a new system, will commence pilot testing in April 2020.

1.31 In October 2018, Defence advised that it had concluded its trial of the Project Performance Review (PPR) in November 2017. At that time, PPR was a spreadsheet; now, the PPR is a bespoke Information Communications Technology (ICT) platform which draws project performance data from Defence systems. It is intended for use by project managers to inform discussions with Project Directors and Branch Heads. PPR has not been developed to replace the MRS.

1.32 In January 2018, Defence initiated a plan to implement the PPR across CASG. Defence has now commenced Phase 2 of PPR Release, and its ICT platform is currently being used by 60 projects. Defence has advised that six MPR projects are using PPR.62 The information in these documents is largely consistent with the projects’ PDSSs. The ANAO observed inconsistencies relating to:

- project approval dates;

- the number of High- or Extreme-rated project risks; and

- project maturity scores.

Results of the review

1.33 The following sections outline the results of the ANAO’s review, which inform the overall conclusion in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General for 2018–19.

Financial framework

1.34 The project financial assurance statements were introduced in the 2011–12 Major Projects Report and have been included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General since 2014–15. The contingency statements were introduced for the first time in the 2013–14 report and these describe the use of contingency funding to mitigate project risks. Together, they are aimed at providing greater transparency over projects’ financial status.

1.35 A project’s total approved budget comprises:

- the allocated budget, which covers the project’s approved activities, as indicated in the MAA; and

- the contingency budget, which is set aside for the eventuality of risks occurring and includes unforeseen work that arises within the delivery of the planned scope of work.63

1.36 In 2018–19, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework as it applied to managing project budgets and expenditure, including: project financial assurance, contingency, the reporting environment, and reporting cost variations and personnel costs.

Project financial assurance statement

1.37 The project financial assurance statement’s objective is to enhance transparency by providing readers with information on each project’s financial position (in relation to delivering project capability) and whether there is ‘sufficient remaining budget for the project to be completed’.64

1.38 In September and November 2018, due to cost pressures, the Joint Strike Fighter project received government approval to transfer project scope of $1.5 billion to other phases of the Joint Strike Fighter program (none of which have been approved by government). There was no corresponding transfer of funds out of the project budget.65 The PDSS states that ‘there is sufficient budget, including contingency, remaining for the project to deliver the revised scope’.

1.39 The Joint Strike Fighter PDSS reports a risk that project capability may be affected by overall funding or programming issues arising from internal cost growth, forecasting accuracy and external budget constraints. The remedial actions to address this risk reported in the PDSS include:

- ‘Conduct ongoing engagement with the F-35 Joint Program Office and major project suppliers to facilitate improved cost data to allow the F-35 project to meet budgeting and programming expectations’ — i.e. clarifying potential cost pressures on the project;

- ‘Proactive management of cost risk identification and engagement with the Capability Manager to prioritize requirements to deliver project capability within the approved project budget’ — i.e. actively identify cost risk and engage with senior leaders; and

- ‘Options may be developed for Capability Manager consideration to achieve project affordability by aligning project expenditure with the Defence Integrated Investment Program capacity in any specific year’ — i.e. consider options for scheduling project expenditure to align with Defence’s available funding.

1.40 The Chief Finance Officer’s representation letter to the Secretary of Defence on the 2018–19 MPR’s project financial assurance statements was unqualified. The project financial assurance statement is restricted to the current financial contractual obligations of Defence for these projects, including the result of settlement actions and the receipt of any liquidated damages, and current known risks and estimated future expenditure as at 30 June 2019.

Contingency statements and contingency management

1.41 The purpose of the project contingency budget is to estimate the inherent cost, schedule and technical uncertainties of projects’ in-scope work.66 Defence policy requires project managers to ensure that all decisions in regards to a project’s contingency budget are included in the project’s contingency budget log to ensure ongoing transparency and traceability.67

1.42 PDSSs are required to include a statement regarding the application of contingency funds during the year, if applicable, as well as disclosing the risks mitigated by the application of those contingency funds. Defence’s Project Risk Management Manual (PRMM version 2.4, page 110)68 requires that contingency be applied for identified risk mitigation activities which have been assessed as being cost effective and representing value for money.

1.43 Contingency provisions for projects are not programmed or funded in cash terms.69 As such, projects are encouraged to meet contingency funding requirements from within their currently programmed cash funding. If this cannot be achieved, a project may then propose to access contingency funding from the relevant capital program (Approved Major Capital Investment Program (AMCIP), Facilities and Infrastructure Program (FIP) and ICT Capital Program). If this cannot be achieved, the contingency call will be presented to the Defence Investment Committee, which if agreed will potentially be met by budget offsets across the whole Integrated Investment Program.70

1.44 Three projects in the MPR had contingency funds applied in 2018–19: MRH90 Helicopters (supportability and performance risks), Repl Replenishment Ships (implementation of capability requirements such as spares and identification of friend or foe, and delivery from Spain to Australia), and Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B (Interface Control Integration).

1.45 In 2017–18, the remaining scope of two projects was transferred into Collins R&S (SEA 1114 Phase 3 and SEA 1439 Phase 5B1). In 2018–19, the associated budgets were transferred to Collins R&S. A contingency allocation was transferred along with the budget of SEA 1439 Phase 5B1. Previous to this, Collins R&S did not have a contingency allocation. As a result, all 26 projects in the 2018–19 MPR now have a contingency allocation.

1.46 The ANAO’s examination of projects’ contingency logs as at 30 June 2019 highlighted that:

- the clarity of the relationship between contingency allocation and identified risks continues to be an issue. Five projects (LHD Ships, Repl Replenishment Ships, CMATS, ANZAC ASMD 2B, and Pacific Patrol Boat Repl) did not explicitly align their contingency log with their risk log, by including risk identification numbers as required by PRMM version 2.4; and

- there were two project offices (CMATS and ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl) that did not meet all the requirements of PRMM version 2.4 in terms of keeping a record of review of contingency logs. However, the ANAO observed that the information required could be located in other documents.

1.47 Non-compliance with PRMM version 2.4 has resulted in inconsistent approaches between projects in the management of contingency logs, with some projects advising that they will not remedy these non-compliances until the outcomes of the risk management reform within CASG are known (see para 1.59).

Reporting environment

1.48 On 4 April 2018, Defence advised project offices that project financial reporting for 2017–18 PDSSs would be prepared on the same basis as project approvals and expenditure represented in the Portfolio Budget Statements and the Defence Annual Report (i.e. on a cash basis).71

1.49 Defence obtains cash expenditure data using a management reporting tool called BORIS. Prior to the 2017–18 MPR, accrual expenditure data was extracted from the Financial Management Information System known as ROMAN. Given the change in the extraction method, the ANAO requested that Defence perform reconciliations of the cash expenditure figures from BORIS to ROMAN for each project.

1.50 In the 2018–19 MPR, Defence continued to report the projects’ financial information on a cash basis and therefore continued to perform these reconciliations. This activity concluded in October 2019 and enabled the ANAO to obtain assurance over the cash expenditure. The Defence Chief Finance Officer has determined that, from the 2020–21 MPR onwards, Defence would report expenditure data on an accrual basis. The 2019–20 MPR should, therefore, be the last year that these reconciliations need to be performed.

Reporting cost variations since Second Pass Approval and personnel costs

1.51 In May 2018, the JCPAA wrote to the Auditor-General to request that the ANAO report back to it ‘on how Defence major project cost variations and the costs of retaining project staff over time might be reported annually in future Major Projects Reports.’72

1.52 A new table was included in the 2017–18 MPR showing all budget variations post initial Second Pass Approval for projects. Refer to Table 8 on page 42.

Project Personnel Numbers and Costs

1.53 In terms of calculating the cost of retaining project staff, Defence advised the ANAO in November 2018 that its current IT systems do not provide a direct mapping of personnel to projects. It noted that personnel often work on multiple projects and sustainment activities at any given time.

1.54 The ANAO observed during fieldwork in 2019 that several MPR projects had staff who worked concurrently on other projects, which included shared corporate staff. Some of these projects did not have systems in place to record accurately the proportion of time these shared staff attributed to the project. Moreover, the ANAO observed that MPR projects used different methods to record personnel data.

1.55 Defence has advised the ANAO that it is not yet in a position to provide the staff cost component of projects and its systems are not capable of calculating the cost of retaining project staff over time. Accordingly, Defence has not provided any data on the costs of project staff for projects in the MPR. The ANAO will continue to monitor Defence’s progress in recording project personnel numbers and costs in future reports.

Enterprise Risk Management Framework

1.56 While major risks and issues data in the PDSSs remains excluded from the formal scope of the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report73, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information are required to be detailed in the report. The following information is included to provide an overall perspective of how risks and issues are managed within Defence and the selected Major Projects.

1.57 Risk management has been a focus of the MPR since its inception. The CASG risk management environment consists of multiple policies and varying implementation mechanisms and documentation. There are multiple group-level (i.e. CASG), sub-group (i.e. Divisional) and project-level risk management documents. The primary focus of the ANAO’s examination of risk management is at the project level, in order to provide assurance over the PDSSs.

1.58 At the Group level, Deputy Secretary CASG issued a directive in May 2017 establishing a CASG Risk Management Reform Program to implement a risk management model that is situated within Defence’s risk management framework. To date, Defence has delivered the first two phases of the reform (establishment of the CASG Risk Management Group Model, and the associated support activities such as training and consultation). The third phase of the reform — which includes the development of risk management policies and toolsets for use by projects — was initially planned to be concluded in June 2019. Defence has advised that it has experienced delays in completing certain deliverables, and that the contract for the completion of the Risk Reform Program has been extended to February 2020. Defence expects that, once the Reform has concluded, implementation will take a number of annual cycles to reach maturity.74

1.59 The ANAO has observed that some projects chose not to review risk and issues management procedures until this stage has been completed, as noted at paragraph 1.47. The ANAO will continue to monitor the implementation of the reform as part of future reviews, but will not be able to consider including risks and issues in the scope of the MPR until the reform is sufficiently progressed.

1.60 In 2018–19, the ANAO again examined project offices’ risk and issue logs at the Group and Service level, which are predominantly created and maintained utilising spreadsheets and/or Predict! software.75 Overall, the issues with risk management that the ANAO observed related to:

- variable compliance with corporate guidance, for example all projects had a Risk Management Plan, however; 10 out of 26 Major Projects did not validate the currency of the Risk Management Plan in line with PRMM version 2.476;

- the visibility of risks and issues when a project is transitioning to sustainment;

- for one project (Joint Strike Fighter), sustainment and acquisition risks are managed together, despite Defence risk management policy for acquisition and sustainment providing inconsistent guidance77;

- the frequency with which risk and issue logs are reviewed to ensure risks and issues are appropriately managed in a timely manner, and accurately reported to senior management;

- risk management logs and supporting documentation of variable quality, particularly where spreadsheets are being used78; and

- lack of quality control resulting in inconsistent approaches in the recording of issues within Predict!

1.61 The ANAO has previously observed that Defence’s use of spreadsheets as a primary form of record for risk management is a high risk approach. Spreadsheets lack formalised change/version control and reporting, thereby increasing the risk of error. This can make spreadsheets unreliable corporate data handling tools as accidental or deliberate changes can be made to formulae and data, without there being a record of when, by whom, and what change was made. As a result, a significant amount of quality assurance is necessary to obtain confidence that spreadsheets are complete and accurate at 30 June, which is not an efficient approach. The ANAO’s review of CASG’s 26 project offices indicates that 15 utilise spreadsheets79 as their primary risk management tool, five utilise Predict!80, one (Maritime Comms) utilises both Microsoft Excel and Predict!, two (Joint Strike Fighter and CMATS) utilise a bespoke SharePoint based tool, one (MH-60R Seahawk) utilises Microsoft Word, one (Night Fighting Equip Repl) utilises the Project Performance Review (see paragraph 1.31), and one (HATS) does not currently manage any risks given the delivery of all primary project elements. Defence has advised that a risk management system will not be mandated until the outcomes of the CASG risk reform are known (see paragraph 1.58).

1.62 The JCPAA recommended in September 2018 that Defence plan and report a methodology to the Committee showing how acquisition projects can transition from the use of spreadsheet risk registers to tools with better version control.81 In response, Defence advised that the Risk Reform Program was developing a revised methodology for managing project risk and intended to commence prioritised transition of projects into the remodelled risk management approach from the first quarter of 2019. However, the ANAO observed in the course of its 2019 site visits that MPR projects had not received project specific guidance. Defence advised the ANAO in October 2019 that it is looking to mandate a standardised ICT tool for the management of risk across projects. The decision on this tool is expected in November 2019. The 2019–20 MPR will report on MPR projects’ use of the mandated tool.

Project maturity framework

1.63 Project Maturity Scores have been a feature of the Major Projects Report since its inception in 2007–08. The DMO Project Management Manual 2012 defined a maturity score as:

The quantification, in a simple and communicable manner, of the relative maturity of capital investment projects as they progress through the capability development and acquisition life cycle.82

1.64 Maturity scores are a composite indicator, cumulatively constructed through the assessment and summation of seven different attributes. The attributes are: Schedule, Cost, Requirement, Technical Understanding, Technical Difficulty, Commercial, and Operations and Support, which are assessed on a scale of one to 10.83 Comparing the maturity score against its expected life cycle gate benchmark provides internal and external stakeholders with a useful indication of a project’s progress.

1.65 The ANAO has previously identified that the policy guidance underpinning the attribution of maturity scores would benefit from a review for internal consistency and the relationship to Defence’s contemporary business. For example, allocating approximately 50 per cent of the maturity score at Second Pass Approval, regardless of acquisition type, is often inconsistent with the proportion of project budget expended, and the remaining work required to deliver the project. Further, the existing project maturity score model does not always reflect a project’s progress during the often protracted build phase, particularly for developmental projects. During this phase it can be expected that maximum expenditure will occur, and that many risks will be realised, some of which will only emerge as test and evaluation activities are pursued through to acceptance into operational service.

1.66 In 201684 and again in 201785, the JCPAA recommended that Defence update the policy on Project Maturity Scores. At the JCPAA hearing held on 23 March 2018, Defence undertook to update the framework by mid-2018 with a two-stage process: first to remediate inconsistencies in the policy and accommodate Interim Capability Life Cycle terminology; then to undertake a more substantial amendment of the policy.86 In September 2018, the JCPAA sought a written update from Defence outlining progress towards updating the policy.87 Also in September 2018, Defence advised the ANAO that the maturity score process was being re-considered within the CASG risk reform context. In December 2018, Defence reported this to the JCPAA in its response to the 2018 recommendation.

1.67 In October 2019, Defence advised the ANAO that a draft Project Maturity Score policy has been developed (renamed the ‘Project Progress Score’) and will be trialled and evaluated in late 2019, for implementation in the 2020–21 MPR. Defence further advised that while the progress score has been decoupled from the risk reform work, it will be informed by existing project risk polices and enhanced by improvements arising out of the risk reform framework. The ANAO was provided the draft Project Progress Score policy in November 2019. The draft indicates that the Project Progress Score will be calculated based on 10 project attributes, leading to a total score out of 100, instead of the seven attributes and total score out of 70 under the current Project Maturity Score policy. The draft policy also notes that ‘The [Project Progress Score] is not designed as an assessment of project risk’.

Caveats and deficiencies

1.68 Defence has not defined the terms ‘caveat’ or ‘deficiency’ to the declaration of significant milestones in its internal policies and procedures. The ANAO has observed use of these terms by Defence to represent exceptions to the achievement of significant milestones declared by Defence such as IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC.

1.69 The 2017–18 MPR noted a ‘reduced trend of Major Projects which had achieved significant milestones with caveats’ and Defence’s advice that it discourages Independent Assurance Reviews recommending caveats at FOC.88 Only one project (Growler) achieved a major milestone with caveats in 2017–18.89

1.70 In 2018–19, Defence declared more milestones with caveats than in 2017–18, as follows:

- P-8A Poseidon — Defence declared two caveats to the achievement of the Operational Capability 2 (OC2) milestone in February 2019, related to deficiencies of spares (Fly Away Kits) and Operational Flight Trainer (pilot simulator) qualification; and

- Growler — Defence declared one caveat to the achievement of the IOC milestone in February 2019, related to in-country aircrew training not yet possible due to delays in delivery of the Mobile Threat Training Emitter System.

1.71 The Chief of Air Force acknowledged achievement of FMR for the Additional MRTT project in October 2019, with an ‘accepted deficiency’ relating to the non-delivery of a minor piece of support equipment.

1.72 In addition, the Chief of Navy declared FOC for the LHD Ships project in November 2019, with seven ‘notable deficiencies’. Key deficiencies referenced in the PDSS relate to technical issues and defects, primarily affecting the propulsion pods, and Integrated Logistic Support. Remediation is underway through the Transition and Remediation Program, and the prime contract has been extended to allow for closure of the outstanding contractual requirements.90

1.73 The ANAO will continue to monitor Defence’s declaration and resolution of caveats (or exceptions) to the achievement of significant Capability Milestones in future reviews. This will include projects which have been removed from the MPR with outstanding caveats which are required to be reported by Defence in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence until their final status is accepted by the Capability Manager.91

2. Analysis of Projects’ Performance

2.1 Performance information is important in the management and delivery of major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects). It informs decisions about the allocation of resources, supports advice to government, and enables stakeholders to assess project progress.

2.2 Project performance has been the subject of many of the reviews of the Department of Defence (Defence), and a consistent area of focus of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) since the first Major Projects Report (MPR). This chapter progresses previous Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) analysis over project performance.

Project performance analysis by the ANAO

2.3 The major dimensions of projects’ performance are:

- Cost performance (pp. 37–49) — this includes the percentage of budget expended (Budget Expended), changes in budget since Second Pass Approval, in-year changes to budget, and in-year expenditure;

- Schedule performance (pp. 50–61) — this includes the percentage of time elapsed (Time Elapsed), total schedule slippage, and in-year changes to schedule; and