Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2022–23 Major Projects Report

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

What is the purpose of the MPR?

The MPR is an annual review of the Department of Defence’s (Defence’s) major defence equipment acquisitions, undertaken at the request of the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). Its purpose is to provide information and assurance to the Parliament on the performance of selected acquisitions at 30 June 2023.

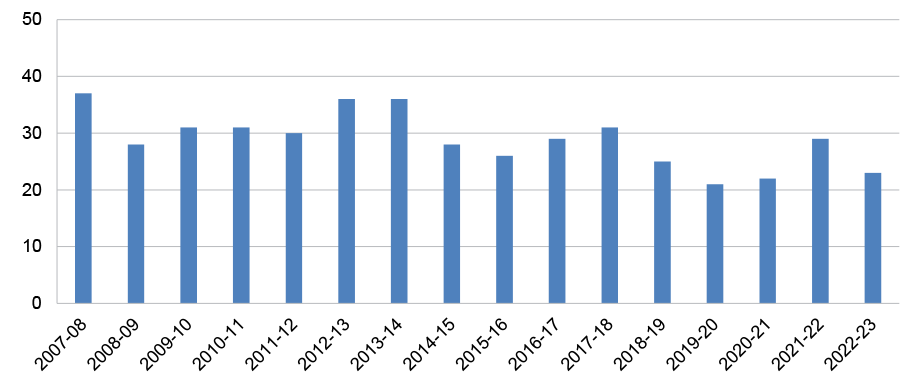

This year, it includes 20 major projects. This is the sixteenth MPR since its commencement in 2007–08.

What did we find?

The ANAO reviewed the Defence information in the 20 Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) and the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, excluding the forecast information, against the requirements of the 2022-23 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines).

Based on the review procedures and the evidence obtained, the Auditor-General concluded that, with two exceptions, nothing came to his attention that caused him to believe that the information reviewed was not prepared in accordance with the Guidelines.

The two exceptions were:

- The LAND 200 Tranche 2 Battlefield Command System PDSS is materially inconsistent with evidence obtained during the course of the review. The material inconsistencies relate to the degree of confidence that materiel capability will be met; and

- Defence removed previously reported lessons learned from all 2022-23 PDSSs. The information disclosed instead does not satisfy the requirements of the Guidelines and is materially inconsistent with evidence obtained by the ANAO.

The Auditor-General also drew attention to disclosures within the Statement by the Secretary of Defence that some information in twelve PDSSs has not been published due to Defence’s assessment that the information would or could reasonably be expected to cause damage to the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth.

What is reviewed?

Defence prepares Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) on selected major defence equipment acquisition projects in accordance with guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA. The PDSSs cover:

- Background and government approvals

- Financial performance

- Schedule performance

- Delivery against agreed scope

- Risks and issues

- Lessons learned by the project

- Management accountability for the project

The ANAO reviews the information in Defence’s PDSSs in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards specified by the Auditor-General under the Auditor-General Act 1997. This year Defence decided that certain information was not for publication in 12 of the 20 PDSSs (60 per cent) on security grounds. The ANAO has reviewed the information not published by Defence.

$58.6bn

was the value of the 20 Defence Major Projects at 30 June 2023.

9 of 20

Defence Major Projects experienced in-year schedule slippage.

91%

was the expected delivery against agreed scope across the Major Projects at 30 June 2023 — with nine projects reporting that some elements of capability/scope delivery were under threat or unlikely to be met.

Due to the complexity of material and the multiple sources of information for the 2022–23 Major Projects Report, we are unable to represent the entire document in HTML. You can download the full report in PDF or view selected sections in HTML below. PDF files for individual Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSS) are also available for download.

!Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

Summary

Background

1. The Department of Defence’s (Defence) Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) manages the process of bringing most new specialist military equipment into service for the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Since October 2022, the Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group (NSSG) has had responsibility for building and sustaining maritime capabilities.1 At 30 June 2023, Defence was managing 609 major and 93 minor acquisition projects, with a total acquisition cost of $190 billion.2 Defence capitalised some $8.5 billion from these projects in 2022–23.3

2. The Major Projects Report (MPR) contains Defence information and commentary on a selection of its major projects (the Major Projects) and assurance and analysis of that information by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO). This report is the sixteenth annual MPR.

3. Major Projects are selected for inclusion in the MPR based on criteria endorsed by the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).4 The projects represent a selection of the most significant major projects managed by CASG and NSSG.

4. The total approved budget for the 20 Major Projects included in this report is approximately $58.6 billion, which is 30.8 per cent of the total $190 billion budget for major and minor acquisition projects.

Selected projects

5. The 20 Major Projects selected for review comprise six SEA projects, eight LAND projects, five AIR projects and one joint (JNT) project. These projects and their government approved budgets at 30 June 2023 are listed in Table 1, below.

Table 1: 2022–23 MPR — selected projects and approved budgets at 30 June 2023

|

Project number (Defence capability plan) |

Project name (on Defence advice) |

Abbreviation (on Defence advice) |

Approved budget ($m) |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability |

Joint Strike Fighter2 |

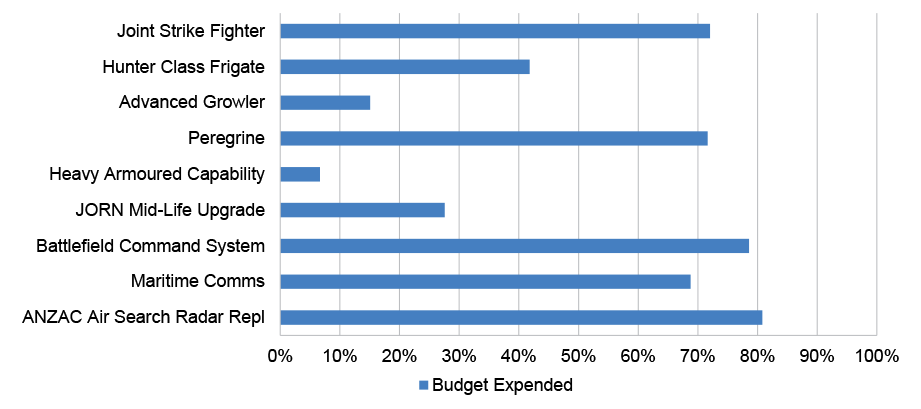

16,424.6 |

|

SEA 5000 Phase 1 |

Hunter Class Frigate Design and Construction |

Hunter Class Frigate2 |

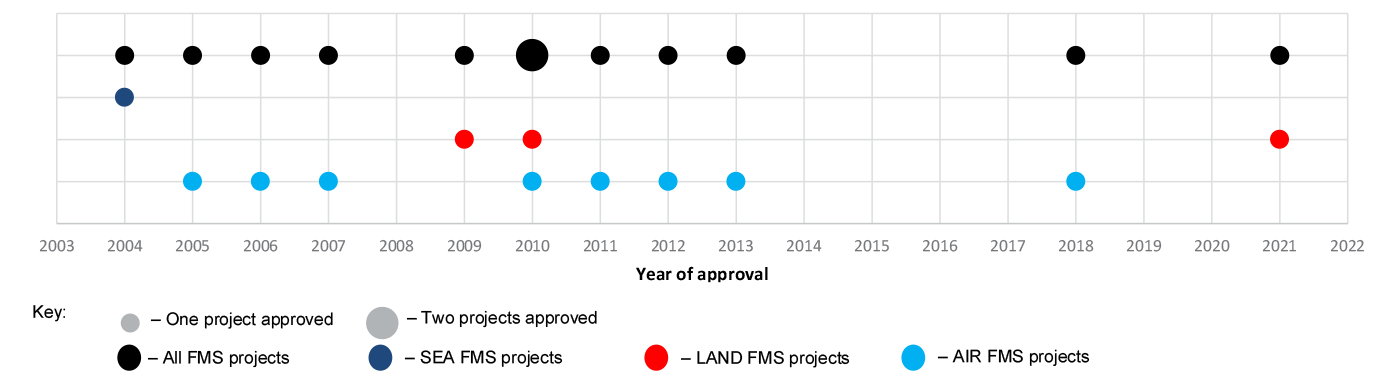

6148.2 |

|

LAND 400 Phase 2 |

Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles |

Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles2 |

5657.3 |

|

SEA 1180 Phase 1 |

Offshore Patrol Vessel |

Offshore Patrol Vessel2 |

3664.1 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6 |

Multi-Role Helicopter |

MRH90 Helicopters2 |

3654.5 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3B |

Medium Heavy Capability, Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers |

Overlander Medium/Heavy2 |

3399.7 |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 6 |

Advanced Growler Development |

Advanced Growler1 |

3200.1 |

|

AIR 7000 Phase 1B |

MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System |

MQ-4C Triton |

2403.7 |

|

AIR 555 Phase 1 |

Airborne Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance and Electronic Warfare (ISREW) Capability |

Peregrine |

2360.2 |

|

LAND907 Phase 2/LAND 8160 Phase 1 |

Main Battle Tank Upgrade, Combat Engineering Vehicles |

Heavy Armoured Capability1 |

2283.0 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 4 |

Protected Mobility Vehicle – Light (PMV-L) |

Hawkei2 |

1971.5 |

|

AIR 2025 Phase 6 |

Jindalee Operational Radar Network |

JORN Mid-Life Upgrade2 |

1288.0 |

|

LAND 19 Phase 7B |

Short Range Ground Based Air Defence |

SRGB Air Defence |

1232.8 |

|

AIR 5431 Phase 3 |

Civil Military Air Management System |

CMATS2 |

1010.0 |

|

LAND 200 Tranche 2 |

Battlefield Command System |

Battlefield Command System2 |

971.4 |

|

JNT 2072 Phase 2B |

Battlespace Communications System Phase 2B |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B |

947.4 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 5B2 |

Collins Class Communications and Electronic Warfare Improvement Program |

Collins Comms and EW2 |

614.2 |

|

SEA 3036 Phase 1 |

Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

502.9 |

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Communications Modernisation |

Maritime Comms2 |

436.4 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 4B |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl 2 |

429.5 |

|

Total: 20 |

|

|

58,599.6 |

Note 1: This is one of two projects included in the MPR for the first time in 2022–23.

Note 2: This is one of 13 projects examined in an ANAO performance audit. See Appendix 1, on p. 102, for more information.

Source: Defence’s Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) in Part 3 of this report.

Rationale for undertaking the review

6. The MPR is prepared at the request of the Parliament. The JCPAA has stated that the objective of the MPR is ‘to improve the accountability and transparency of Defence acquisitions for the benefit of Parliament and other stakeholders.’5 The JCPAA commissions the MPR in the public interest, for the benefit of users of the report inside and outside the Parliament. The MPR informs parliamentary scrutiny and the national conversation on major Defence acquisitions, and is intended to assist users by adopting a consistent reporting format over time and through the inclusion of summary and longitudinal analysis prepared by the ANAO.

7. Defence’s major defence equipment acquisition projects remain the subject of parliamentary and public interest due to their: high cost and contribution to national security in a changing strategic environment; the challenges involved in completing them within the specified budget and schedule, and to the required capability; and their contribution to industrial and employment policy objectives.

Conduct of the review

8. The MPR is prepared by Defence and the ANAO. Defence prepares information for ANAO review in accordance with the 2022–23 Major Projects Report Guidelines (Guidelines) endorsed annually by the JCPAA (included in Part 4 of this report).6 The status of the Major Projects selected for review is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence (included in Part 3 of this report) and a Project Data Summary Sheet (PDSS) prepared by Defence for each of the Major Projects (included in Part 3 of this report).

9. The ANAO has reviewed each of the PDSSs prepared by Defence as a ‘priority assurance review’ under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act), which allows the ANAO full access to the information gathering powers under the Act.

10. The ANAO’s review provides limited assurance7 and was undertaken in accordance with the applicable auditing standards. The ANAO’s review included an assessment of Defence’s systems and controls, including the governance and oversight in place, to ensure appropriate project management. The ANAO also sought representations and confirmation from Defence senior management and industry (through Defence) on the status of the selected Major Projects.

11. The objective of this ANAO assurance engagement and the ANAO review procedures is to allow the Auditor-General to provide independent assurance over the status of the Major Projects selected for review. A summary of the Auditor-General’s conclusion is set out in paragraphs 26 to 29. The full conclusion is found in the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report in Part 3 of this report.

12. Certain forecast information found in the PDSSs is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review, such as Australian Industry Capability (AIC), forecast dates, expected capability/scope delivery performance and future risks.8 Accordingly, the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report does not provide assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information are considered in forming the Auditor-General’s conclusion. These exclusions to the scope of the review are due to a lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and/or accurate evidence in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review.9 This has been an area of focus of the JCPAA over a number of years10 and it is intended that all components of the PDSSs will eventually be included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

13. In addition to the formal assurance review, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of the PDSSs, including longitudinal analysis.11

14. Defence provides additional insights and context in its commentary and analysis contained in Part 2 of the MPR. This commentary and analysis is not included in the scope of the ANAO’s assurance review. Information on significant events occurring post 30 June 2023 is outlined in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence contained in Part 3 of the MPR and is included in the scope of the ANAO’s assurance review.

Treatment of classified information

15. The Guidelines approved by the JCPAA set out the information to be included by Defence in its PDSSs for each MPR project, including forecast dates and capability information. The Guidelines also provide (at paragraph 1.23 of Part 4) that:

Defence is responsible for ensuring information of a classified nature is made available to the ANAO for review, as it relates to the data contained within the PDSSs. Data of a classified nature must be prepared in such a way as to allow for unclassified publication. Defence will confirm to the ANAO the classification of information proposed to be published in the MPR. Defence will provide advice with regards to the aggregated security classification of information contained within the PDSS suite, and suitability for unclassified publication.

2021–22 MPR — not for publication material

16. In the course of preparing the 2021–22 MPR, Defence advised the ANAO of its decision that schedule information for four projects12 was not for publication, and had not been published in the relevant PDSSs. This meant that 19 per cent of the 21 PDSSs in last year’s MPR were affected by the decision to not publish certain information.

17. As required by the Guidelines, the not for publication information was provided to the ANAO for review. The ANAO obtained assurance over the information provided.

18. The Auditor-General included an Emphasis of Matter13, in the Independent Assurance Report, relating to the PDSSs for the four affected projects. This was the first time that information of this type had been excluded from a PDSS. The exclusion of forecast dates and variance information meant that this information was not available to users of the MPR. Further, as a result of non-disclosure by Defence, the ANAO was not in a position to publish a complete analysis of schedule performance for the suite of MPR projects, as in the past.14 The 2021–22 MPR provided a reduced level of transparency and accountability to Parliament and other stakeholders.

2022–23 MPR — not for publication material

19. In the course of preparing the 2022–23 MPR, Defence again advised the ANAO of its decision that certain information relating to forecast dates, capability delivery information and variance information was not for publication, and would not been included in the relevant PDSSs for 12 projects.

20. The Secretary of Defence has stated, in Part 2 of this year’s MPR, that:

In accordance with the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) 2022-23 MPR Guidelines, Defence is responsible for ensuring that the information in the MPR is suitable for unclassified publication. The DSR highlighted that Australia’s strategic circumstances have markedly changed since the MPR was first implemented. Defence has assessed that some details, both in respect of individual projects and in aggregate, would or could reasonably be expected to cause damage to the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth without sanitisation of the data. There are 12 projects in this MPR where some new or updated information has not been published on security grounds.

Defence provided the required information to the ANAO to conduct their assurance and analysis activities.15

21. The Secretary has further stated, in this year’s Statement by the Secretary of Defence, that:

A security classification review of the information contained within the PDSS for release in the 2022-23 MPR has been completed.

The purpose of the security review is to ensure that each individual PDSS reflects data at an ‘unclassified’ level and to confirm the aggregated information is not a risk to national security, and is suitable for public release through tabling in Parliament.

It is assessed that some details, both with respect to independent projects and in the aggregate, would or could reasonably be expected to cause damage to the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth without sanitisation of the data. These details have been removed from the relevant PDSS. This is marked in the PDSS by the terms “NFP” meaning Not for Publication, or “Delayed” meaning delayed from the Original Planned date or the Forecast date in the 2022–23 PDSS.16

22. Table 2 (below) lists the 12 affected PDSSs and the approved budgets for the affected projects. The affected PDSSs represent 60 per cent of all PDSSs. The affected projects represent 63.7 per cent of the aggregate approved budget for the MPR projects as a whole.

Table 2: Defence PDSSs indicating that certain information is not for publication (NFP), and approved budgets for affected projects

|

Project number (Defence capability plan) |

Abbreviated name |

Approved budget ($m) |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

Joint Strike Fighter |

16,424.6 |

|

LAND 400 Phase 2 |

Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles |

5657.3 |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 6 |

Advanced Growler |

3200.1 |

|

AIR 7000 Phase 1B |

MQ-4C Triton |

2403.7 |

|

AIR 555 Phase 1 |

Peregrine |

2360.2 |

|

LAND907 Phase 2/LAND 8160 Phase 1 |

Heavy Armoured Capability |

2283.0 |

|

AIR 2025 Phase 6 |

JORN Mid-Life Upgrade |

1288.0 |

|

LAND 19 Phase 7B |

SRGB Air Defence |

1232.8 |

|

LAND 200 Tranche 2 |

Battlefield Command System |

971.4 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 5B2 |

Collins Comms and EW |

614.2 |

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Comms |

436.4 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 4B |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl |

429.5 |

|

Total projects/approved budget affected by NFP decisions |

12 |

37,301.2 |

|

Percentage of projects/approved budget affected by NFP decisions |

60% |

63.7% |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence’s 2022–23 PDSSs.

23. Table 3 (below) provides information on the sections of the 12 affected PDSSs that have been impacted by Defence’s decision to not publish certain information relating to forecast dates, capability delivery information and variance information.

24. Notably, eight projects did not disclose a Final Operational Capability (FOC) forecast date in the PDSS (2021-22: three), and one project did not have a settled FOC date (2021-22: four). This means that 45 per cent of PDSSs (nine out of 20) do not include FOC dates this year.17

Table 3: Defence PDSSs – sections affected by not for publication (NFP) decisions

|

Project |

Section 3.3 of PDSS |

Other sections of PDSS |

|

AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B New Air Combat Capability (Joint Strike Fighter) |

Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Post-Final Operational Capability. Milestone dates and variance information. |

Sections 1.3, 2.1, 3.2, 5.1 and 5.2 – information relating to capability, weapons delivery and delays of acceptance of final air vehicles. Section 4.2 – Post-Final Operational Capability details. |

|

LAND400 Phase 2 Mounted Combat Reconnaissance Capability (Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles) |

N/A |

Sections 1.3, 5.1 and 5.2 – information relating to Issue 4 and air transport dates. |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 6 Advanced Growler Development (Advanced Growler) |

Initial Materiel Release (IMR). Initial Operational Capability (IOC). Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 1.1 – Jammer type information. Section 2.3B – information relating to weapons quantities. Section 4.2 – IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

|

AIR 7000 Phase 1B MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (MQ-4C Triton) |

N/A |

Section 3.2 – information relating to the delivery date for Test and Evaluation–Acceptance. Section 1.2 and 4.1 – delays in delivery of the initial Misson Control System. |

|

AIR 555 Phase 1 Airbourne Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance and Electronic Warfare (ISREW) Capability (Peregrine) |

Initial Materiel Release (IMR). Initial Operational Capability (IOC). Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 1.2 – information relating to schedule dates. Section 3.2 – information relating to delivery dates for test and evaluation. Section 4.2 – IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

|

LAND 907 Phase 2/ LAND 8160 Phase 1, Main Battle Tank Upgrade, Combat Engineering Vehicle (Heavy Armoured Capability) |

Initial Materiel Release (IMR). Initial Operational Capability (IOC). Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 3.1 – information relating to achievement of Major System/Platform Variants. Section 3.2 – information relating to delivery dates for test and evaluation. Section 4.2 – IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

|

AIR 2025 Phase 6 Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN Mid-Life Upgrade) |

Initial Materiel Release (IMR). Initial Operational Capability (IOC). Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 1.2 – schedule performance modified. Section 3.1– information relating to delivery dates for Design Review Progress. Section 3.2 – information relating to delays in delivery, including variance. Section 4.2 – IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

|

LAND 19 Phase 7B Short Range Ground Based Air Defence (SRGB Air Defence) |

Initial Materiel Release (IMR) and Initial Operational Capability (IOC) reported as ‘delayed’. Milestone dates and variance information not for publication. |

Section 1.2 – schedule performance modified. Section 2.3B – information relating to quantities of equipment purchased from the US government. Section 3.2 – information relating to delivery date for test and evaluation, delays in delivery of Fire Units, and CEA Radars. Section 4.2 – IMR and IOC forecast dates. |

|

LAND 200 Tranche 2 Battlefield Command System |

Initial Materiel Release (IMR). Initial Operational Capability (IOC). Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 3.1 – Information relating to delivery dates for design review including delivery and variance. Section 3.2 – information relating to delivery dates for test and evaluation, and delays in delivery, including variance. Section 4.2 – IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 5B2 Collins Class Communications and Electronic Warfare Improvement Program (Collins Comms and EW) |

Initial Operational Capability (IOC) (Stage 1, 2 and MWES). Final Materiel Release (Stage 1). Milestone dates and variance information. Reasons for delays not for publication. |

Section 1.2 – Delays in delivery, including variance. Section 4.2 – IOC forecast date. |

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 Maritime Communications Modernisation (Maritime Comms) |

Initial Operational Capability (IOC). Materiel Releases (Ships 6 and 7). Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 1.2 and 2.2A – Milestone dates and variance. Section 3.2 – information relating to: delivery dates for test and evaluation; delays in delivery of ships 6, 7 and 8; and variance. Section 4.2 – IOC, FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 4B ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement (ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl.) |

Final Materiel Release (FMR). Final Operational Capability (FOC). Milestone dates and variance information. |

Section 1.2 – schedule performance modified in relation to FMR and FOC delays. Section 3.2 – information relating to delivery dates for test and evaluation, system integration and acceptance, and variance. Section 4.2 – FMR and FOC forecast dates. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence’s 2022–23 PDSSs.

25. Defence’s decision to not disclose forecast dates, capability delivery information and variance information for the 12 projects in Table 3 (above) means that this information is not available to users of the MPR. As with the 2021–22 MPR, the 2022-23 MPR provides a reduced level of transparency and accountability to Parliament and other stakeholders. The Auditor-General has included an Emphasis of Matter, in the Independent Assurance Report (see the next section and Part 3 of this report), relating to the PDSSs for the 12 affected projects.

Overall outcomes

Summary of the Auditor-General’s conclusion

26. The Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report for 2022–23 is found in Part 3 of this report.

27. Based on the review procedures and the evidence obtained, the Auditor-General concluded that, with two exceptions, nothing came to his attention that caused him to believe that the information reviewed was not prepared in accordance with the Guidelines.

28. The two exceptions were:

- The LAND 200 Tranche 2 Battlefield Command System PDSS is materially inconsistent with evidence obtained during the course of the review. The material inconsistencies relate to the degree of confidence that materiel capability will be met; and

- Defence removed previously reported lessons learned from all 2022-23 PDSSs. The information disclosed instead does not satisfy the requirements of the Guidelines and is materially inconsistent with evidence obtained by the ANAO.

29. The Auditor-General also drew attention to disclosures within the Statement by the Secretary of Defence (found in Part 3 of this report) that some information in 12 PDSSs has not been published due to Defence’s assessment that the information would or could reasonably be expected to cause damage to the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth.18

Statement by the Secretary of Defence

30. The Statement by the Secretary of Defence (Statement) was signed on 23 January 2024. The Secretary’s statement provides his opinion that the PDSSs for the 20 major acquisition projects that form part of the MPR ‘comply in all material respects with the Guidelines and reflect the status of the projects, as at 30 June 2023’.

31. The Secretary included commentary on the non-publication of information by Defence in 12 PDSSs (see paragraphs 20 to 21).

32. The Statement also details significant events occurring post 30 June 2023, which materially impact the projects included in the report and should be read in conjunction with the individual PDSSs. The Statement includes information on 13 projects.

- Offshore Patrol Vessel (SEA 1180 Phase 1).

- Collins Class Communications and Electronic Warfare (SEA 1439 Phase 5B).

- Maritime Communications Modernisation (SEA 1442 Phase 4).

- ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement (SEA 1448 Phase 4B).

- Hunter Class Frigate Design and Construction (SEA 5000 Phase 1).

- Short Range Ground Based Air Defence Capability (LAND 19 Phase 7B).

- Medium Heavy Capability Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers (LAND 121 Phase 3B).

- Protected Mobility Vehicles Light (Hawkei) (LAND 121 Phase 4).

- Battlefield Command System (LAND 200 Tranche 2).

- Advanced Growler – Airborne Electronic Attack Upgrade (AIR 5349 Phase 6).

- MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (AIR 7000 Phase 1).

- Multi-Role Helicopter (AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6).

- Battlespace Communications Systems (JOINT 2072 Phase 2B).19

Key observations

33. The ANAO’s review (found in Part 1 of this report) includes Defence’s project management and reporting arrangements contributing to the overall governance of the Major Projects. A summary of observations is provided below.

Non-publication of information by Defence and more limited data and analysis in this year’s MPR

34. As discussed at paragraphs 15 to 25, Defence has decided to not publish certain information in 12 PDSSs (2021–22: four). The not for publication information includes forecast dates, capability delivery information and variance information. The affected PDSSs are set out in Tables 2 and 3 (above).

35. As was the case in the 2021–22 MPR, this year’s report does not provide the same level of information compared to reporting in 2020–21 and prior years, and provides a reduced level of transparency and accountability to Parliament and other stakeholders.

36. However, in contrast to 2021–22, the ANAO is in a position to publish aggregate analysis this year on: total schedule slippage across this year’s projects, average schedule slippage across this year’s projects, and in-year schedule slippage across this year’s projects (see Table 7 at page 22). This results from the increase in the number of PDSSs which have not disclosed FOC forecast dates – from four last year to eight this year. The larger number of projects with information not disclosed this year means that it is not possible to derive the ‘not for publication’ information for individual projects from the aggregate analysis. The impacts on the ANAO’s analysis of schedule performance are discussed further in paragraphs 55 to 65.

37. While this year’s MPR provides the user with more aggregate performance information than in the 2021–22 MPR, it does not provide the same level of information on individual project performance compared to the 2020–21 MPR and prior years.

JCPAA recommendations and requests

38. Chapters 1 and 2 of the MPR report on Defence’s implementation of JCPAA recommendations and requests relating to Defence’s acquisition governance, including: Defence’s measurement of capability performance; implementation of CASG’s Predict! risk management system; reporting on major project cost variations; reporting on staff costs for Major Projects; the criteria for Defence’s Projects of Concern regime; and defining terms relating to a delta or deviation from the achievement of a Major Project milestone.

39. In June 2023 the JCPAA tabled Report 496 Inquiry into the Defence Major Projects Report 2020-21 and 2021-22 and Procurement of Hunter Class Frigates: Interim Report on the 2020-21 and 2021-22 Defence Major Projects Report.20 The committee’s interim report made three recommendations relating to: Defence’s governance of its Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern regime; Defence’s contingency funding and lessons learned policies; and the closure of past JCPAA and Auditor-General recommendations. These recommendations are also reported on in Chapters 1 and 2 of the MPR.

40. In its interim report, the Committee indicated that the current MPR process and format remain appropriate for the 2022–23 and 2023–24 editions, and that ‘the Committee is examining the scope and guidelines of the MPR in the next phase of the inquiry to ensure that it continues to provide appropriate transparency and accountability to the Parliament in relation to Defence’s capability acquisition expenditure and remains fit for purpose into the future’.21

Auditor-General reports

41. SEA 5000 Phase 1 (Hunter Class Frigate Design and Construction) entered the MPR in 2019–20 and appears again in the 2022–23 MPR.

42. Auditor-General Report No. 21 2022–23 Department of Defence’s Procurement of Hunter Class Frigates was tabled in May 2023. This performance audit report included two recommendations to Defence. These were to improve: compliance with record keeping requirements; and advice to government on whole-of-life costs and value for money.

43. On 11 May 2023 the JCPAA broadened the scope of its inquiry into the 2020–21 and 2021– 22 Major Projects Reports to include consideration of the performance audit.22

Defence acquisition governance

44. When reviewing Defence’s PDSSs, the ANAO considered the following items.

- Defence’s use of the Independent Assurance Review (IAR) process to report on the status of acquisition projects. In 2022–23, Defence completed an IAR on 13 of the 20 projects in this report (see paragraphs 1.18 to 1.20).23

- Defence’s approach to entry and exit from the Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern lists (see paragraphs 1.21 to 1.37, and 1.42).

- Defence’s reporting to senior department leadership and government stakeholders on the delivery of capability to the Australian Defence Force (ADF) (see paragraphs 1.38 to 1.47).

- The importance of capturing government decisions in internal Defence documentation and ensuring that Materiel Acquisition Agreements are appropriately aligned with these decisions (see paragraphs 1.48 to 1.49).

- Defence’s implementation of the Smart Buyer Framework to support strategic decision making in the acquisition of major projects. The framework was used at the Second Pass government approval stage for two of the projects in this year’s MPR (see paragraphs 1.50 to 1.53).

- Defence’s implementation of Australian Industry Capability (AIC) expectations in the acquisition of major projects (see paragraphs 1.55 to 1.63).24

- Defence’s implementation of new business systems to report on the status of acquisition projects (see paragraphs 1.64 to 1.65).

- Defence’s use of project contingency funds (see paragraphs 1.74 to 1.80). Two MPR projects expended contingency funds in 2022–23. MRH90 Helicopters used previously approved funds to progress treatment of various supportability and performance risks in support of the transition of the MRH90 Taipan into the 6th Aviation Regiment, and SRGB Air Defence used previously approved funds to cover increased contract costs resulting from delays associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The status of CASG’s Risk Management Reform Program and the establishment of the CASG Risk Management Framework (see paragraphs 1.86 to 1.93).

- Projects that had not fully met the requirements of CASG’s Risk Management Manual Version 1 and Financial Policy (titled Management Of Defence Capability Project Contingency) for contingency allocation (see paragraph 1.75) and risk management (see paragraph 1.91).

- The status of CASG’s Lessons Learned policy. The internal policy was updated in February 2022 and Defence is yet to fully implement it, including the compliance monitoring arrangements (see paragraphs 1.94 to 1.99).

- Defence’s declaration of significant capability milestones with ‘caveats’ or ‘deficiencies’25, and Defence guidance on the use of such terms26 (see paragraphs 1.104 to 1.107).

Project performance analysis

45. In addition to its limited assurance review, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of the Defence PDSSs.

46. As discussed in paragraphs 15 to 25, Defence has decided to not publish certain information in 12 PDSSs (2021–22: four). The not for publication information includes forecast dates, capability delivery information and variance information. The affected PDSSs are set out in Tables 2 and 3 (see pages 7 to 11).

47. In common with the 2021–22 MPR, this year’s edition does not provide the same level of transparency and information for users compared to the 2020–21 MPR and prior years. However, as discussed in paragraphs 34 to 37, in contrast to last year the ANAO is in a position to publish aggregate analysis this year on: total schedule slippage across this year’s projects, average schedule slippage across this year’s projects, and in-year schedule slippage across this year’s projects (see Table 7 at page 22). This results from the increase in the number of PDSSs which have not disclosed a Final Operational Capability (FOC) forecast date – from four last year to eight this year. The larger number of affected projects this year means that it is not possible to derive the ‘not for publication’ information for individual projects from the aggregate analysis.

48. While this year’s MPR provides the user with more aggregate performance information than last year, it does not provide the same level of information on individual project performance compared to reporting in 2020–21 and prior years. There has been a reduction in the level of transparency and accountability over the MPR projects since the 2020–21 MPR.

49. A summary of the ANAO’s cost, schedule and capability/scope analysis is set out below. The detailed analysis is found in Chapter 2.

Cost analysis

50. Cost management is an ongoing process in Defence’s administration of the Major Projects. Defence has reported that all 20 projects in this year’s MPR could continue to operate within the total approved budget of $58.6 billion. The MRH90 Helicopters and SRGB Air Defence projects drew upon contingency funds to complete project activities.

51. The total approved budget for the 20 Major Projects has increased by $22.8 billion (39 per cent) since initial Second Pass Approval by government.

52. Budget variations greater than $0.50 billion are detailed in Table 4 (below).27

53. As the MPR focuses on the approved capital budget for Defence acquisition, the ongoing costs of project offices, training, replacement capability, etc., are not reported here.28

54. Cost information was not affected by Defence’s decision to not publish certain information in 12 PDSSs this year.

Table 4: Budget variations over $0.5 billion — post initial Second Pass approval by variation type 1,2

|

Project |

Variation type |

Explanation |

Year |

Amount ($bn) |

|

|

|

Scope increases |

17.4 |

|||

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

|

34 additional aircraft at Phase 4/6 Second Pass Approval |

2005–06 |

2.6 |

|

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

|

58 additional aircraft at Stage 2 Second Pass Approval |

2013–14 |

10.5 |

|

|

MQ-4C Triton |

|

Approvals including Second Pass Approvals for three additional aircraft and sustainment funding for first 7 years |

2019–20 2020–21 2022–23 |

1.4 |

|

|

Advanced Growler |

|

Second Pass Approval for Tranche 1 acquisition and sustainment of mid-band capability and training range upgrades |

2022–23 |

2.9 |

|

|

|

Real cost increases |

0.7 |

|||

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

|

Project supplementation3 ($684.2m) and additional vehicles, trailers and equipment ($28.0m) at Revised Second Pass Approval |

2013–14 |

0.7 |

|

|

|

Other budget movements |

0.5 |

|||

|

Other |

Scope increase/budget transfers (net) |

Other scope changes and transfers |

Various |

0.5 |

|

|

Price Indexation – materials and labour (net) (to July 2010)4 |

1.0 |

||||

|

Exchange Variation – foreign exchange (net) (to 30 June 2022) |

3.3 |

||||

|

Total |

22.85 |

||||

Note 1: For the variations related to all projects and their value, refer to Table 11 on pages 58 to 59 of this report. For the breakdown of in-year variation, refer to Table 12 on p. 61 of this report.

Note 2: For projects with multiple Second Pass Approvals, this table shows variations from the initial approval.

Note 3: Defence has advised that ‘project supplementation’ is a unique term used to describe the approvals history of this project as follows: ‘The original amount of $2549.2, was the Government decision to split Phase 3 into Phase 3A and 3B. In 2011, Government approved Second Pass approval of Phase 3A and the ‘Interim Pass’ Government approval for Phase 3B. The decision to grant Phase 3B ‘Interim Pass’ was to allow greater bargaining power for Defence while negotiating Phase 3A. Phase 3B was always going to return to Government for formal Second Pass approval, which occurred in July 2013, once contract negotiations were complete.’

Note 4: Before 1 July 2010, projects were periodically supplemented for price indexation, whereas the allocation for price indexation is now provided for on an out-turned basis at Second Pass Approval.

Note 5: Figures do not add precisely due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence’s 2022–23 PDSSs.

Schedule analysis

55. Final Operational Capability (FOC) is the key milestone that forms the basis for the majority of the ANAO’s schedule analysis, including aggregate analysis of total schedule slippage across projects, average schedule slippage across projects, and in-year schedule slippage across projects.

56. This year, nine of the 20 projects (45 per cent) either did not disclose the FOC forecast date in their PDSS (eight projects) or did not have a settled FOC date (one project).29

- Defence has decided to not publish FOC forecast dates in eight PDSSs (Joint Strike Fighter, Advanced Growler, Peregrine, Heavy Armoured Capability, JORN Mid-Life Upgrade, Battlefield Command System, Maritime Comms and ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl).30 This represents 40 per cent of all PDSSs.31

- One of the PDSSs (Hunter Class Frigate Design and Construction) did not include an FOC forecast date. This is because the Hunter Class Frigate project did not have an FOC milestone approved by government at 30 June 2023. This represents five per cent of all PDSSs.

57. In the 2021–22 MPR, seven of the 21 Major Projects (33 per cent) either did not disclose their FOC forecast date in their PDSS (three projects) or did not have a settled FOC date (four projects).

- The ANAO reported last year that any aggregated analysis of the remaining 14 projects (which had included FOC dates in their PDSS) would be incomplete, and the inclusion of incomplete schedule performance analysis would misinform users of the MPR, as the 14 projects that had included FOC dates in their PDSS were not representative of all the Major Projects.

- The ANAO was not in a position last year to publish aggregate analysis on: total schedule slippage across the 21 projects, average schedule slippage across the projects, and in-year schedule slippage across the projects. This was reflected in Table 5 of the 2021–22 MPR, which set out the ANAO’s summary longitudinal analysis.

58. This year, an increased number of projects have not disclosed their FOC forecast date in their PDSS – from four (19 per cent) last year to eight (40 per cent) this year. This means that the ANAO is able to publish information in aggregate as it would not disclose the individual Major Projects which have no reported FOC forecast dates. The ANAO is therefore in a position to publish an analysis of: total schedule slippage across the 20 projects, average schedule slippage across the projects, and in-year schedule slippage across the projects. This is reflected in Table 7 (see page 22) of this year’s MPR, which sets out the ANAO’s summary longitudinal analysis.

59. In summary, at 30 June 2023, aggregate schedule performance was as follows for the 20 Major Projects.

- Total schedule slippage was 453 months32 when compared to the initial schedule (2020–21: 405 months). This represents a 23 per cent increase since Second Pass Approval.

- Average schedule slippage was 25 months (2020–21: 23 months).

- In-year schedule slippage totalled 101 months (2020–21: 73 months). This represents a five per cent increase since Second Pass Approval.

60. As indicated in Table 5 (below), in-year schedule slippage across the 20 Major Projects was five per cent.

- Two per cent of in-year schedule slippage was contributed by seven of the eight projects where FOC forecast dates were not disclosed.33 This represents 40 per cent of in-year schedule slippage.

61. Delivering Major Projects on schedule continues to present challenges for Defence. Schedule slippage can affect when the capability is made available for operational release and deployment by the ADF, as well as the cost of delivery.

62. Table 5 (below) provides details of in-year and total schedule slippage by project, except where Defence has indicated that project information is not for publication (NFP).

Table 5: In-year and total schedule slippage1 from original planned Final Operational Capability milestone

|

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

NFP |

NFP |

Hawkei |

12 |

12 |

|

Hunter Class Frigate2 |

N/A |

N/A |

JORN Upgrade |

NFP |

NFP |

|

Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles |

0 |

0 |

SRGB Air Defence |

0 |

0 |

|

Offshore Patrol Vessel3 |

-2 |

0 |

CMATS |

0 |

57 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

6 |

110 |

Battlefield Command System6 |

NFP |

NFP |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

36 |

36 |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B |

0 |

36 |

|

Advanced Growler4,5 |

0 |

0 |

Collins Comms and EW |

0 |

30 |

|

MQ-4C Triton |

0 |

66 |

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

10 |

12 |

|

Peregrine |

NFP |

NFP |

Maritime Comms |

NFP |

NFP |

|

Heavy Armoured Capability |

NFP |

NFP |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl |

NFP |

NFP |

|

Total (months) |

101 |

453 |

|||

|

Total (per cent) |

5 |

23 |

|||

Note 1: Slippage refers to a delay in the current forecast date compared to the original government approved date of FOC. These figures exclude delays to a project’s schedule that do not result in slippage past the original government approved date, and schedule reductions over the life of the project.

Note 2: This project had no capability milestones approved by government at 30 June 2023.

Note 3: This project experienced a two-month delay in the prior year, which was remediated In-year, with no resulting impact on the FOC milestone.

Note 4: This project’s FOC milestone had not been approved by government at 30 June 2023. The MPR analysis has referred to the current final scheduled operational milestone for this project (Tranche 1 Operational Capability 2). It is anticipated that subsequent government approvals will introduce new operational capability milestones including an FOC milestone.

Note 5: This project has reported its slippage in months but has not reported the Original Planned and Current Plans dates for its final milestone. The non-publication of these dates, while publishing a slippage figure, means that this project is reported on individually in some parts of the ANAO’s analysis and not in other parts.

Note 6: The Battlefield Command System (LAND200 Tranche 2) is excluded from this analysis due to the Auditor-General’s Qualified Conclusion, see paragraphs 2.8–2.9 and the Independent Assurance Report in Part 3 of this report.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2022–23 PDSSs.

63. Past MPRs have reported that the management of platform availability has contributed to slippage in some projects.34

64. Projects with developmental content have also experienced significant delays. These projects are MRH90 Helicopters, MQ-4C Triton, CMATS, and Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B.

65. The MPR includes ANAO analysis relating to each project’s Acquisition Categorisation (ACAT) level as reported by Defence.35 The analysis indicates that there has been an increase in the number of projects at the more complex ACAT I36 and ACAT II37 levels. ACAT I projects carry a higher level of technical risk.

Capability/scope analysis

66. The third principal component of project performance examined in this report is progress towards the delivery of capability as approved by government. While the assessment of expected capability/scope delivery by Defence is outside the scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, it is included in the ANAO analysis to provide further perspective on project performance.

67. The Hunter Class Frigate PDSS does not report quantified capability/scope information as this project did not have approved materiel capability/scope to be delivered at 30 June 2023. This project instead reports narratives describing its current project activities.

68. This year’s Defence PDSSs report as follows.

- Nine projects (45 per cent) report they will deliver all capability/scope requirements. This is indicated in ‘green’ in the traffic light diagram included in each PDSS.

- Five projects (25 per cent) report they have experienced challenges with expected capability/scope delivery (2021–22: seven). These are: Hunter Class Frigate, Offshore Patrol Vessel, Overlander Medium/Heavy, MQ-4C Triton, and Battlefield Command System. Defence’s assessment indicates that some elements of capability/scope to be delivered by these projects may be ‘under threat’, but the risk is assessed as ‘manageable’. This is indicated in ‘amber’ in the PDSS traffic light diagram.

- Six projects (30 per cent) report they are unable to deliver all the required capability/scope by FOC (2021–22: four). These are: Joint Strike Fighter, MRH90 Helicopters, Hawkei, JORN Mid-Life Upgrade, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B and Battlefield Command System. This is indicated in ‘red’ in the PDSS traffic light diagram. Table 15 (pages 78 to 80) outlines the reasons for each project’s ‘red’ assessment.

69. In last year’s MPR the PDSSs also quantified, for the first time, any increase to a project’s materiel capability/scope delivery. This was reported as ‘blue’ in the PDSS traffic light diagram for two projects. This year, ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl reported an increase in project materiel capability/scope delivery. This project will deliver a minor increase in scope relating to training simulators.

70. Table 6 (below) summarises the percentage of capability/scope Defence expects will be delivered by the Major Projects. The assessment is at 30 June 2023, as reported by Defence and analysed by the ANAO.38

Table 6: Capability/scope — delivery

|

Expected capability/scope – percentage (Defence reporting) |

2020–21 MPR (%) |

2021–22 MPR (%) |

2022–23 MPR (%) |

|

High confidence (Green) |

97 |

87 |

94 |

|

Under threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

2 |

10 |

1 |

|

Unlikely or removed from scope (Red) |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

Added to scope (Blue) |

–1 |

02 |

03 |

|

Total |

1004 |

1004 |

1004,5,6 |

Note 1: The Blue reporting metric representing additional capability/scope was not used in these years.

Note 2: Defence advised in this year that Pacific Patrol Boat Repl would deliver an additional element of capability/scope at FOC (which equated to approximately five per cent of project scope). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Note 3: Defence advised in this year that ANZAC Air Search Repl would deliver an additional element of capability/scope at FOC (which equated to approximately 0.1 per cent of project scope). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Note 4: The Hunter Class Frigate and Future Subs projects are excluded from this analysis, as their capability/scope delivery was not quantified in these years (Future Subs was reported in 2020–21 and 2021–22 only).

Note 5: The Battlefield Command System (LAND200 Tranche 2) is excluded from this analysis due to the Auditor-General’s Qualified Conclusion, see paragraphs 2.8–2.9 and the Independent Assurance Report in Part 3 of this report.

Note 6: Figures do not add precisely due to rounding.

Source: Defence PDSSs in Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

71. In addition to reporting on expected capability/scope delivery, Defence has continued the practice of including in the PDSSs information (except for certain projects discussed in Table 3, pages 8 to 11) on contractual remedies for projects, including stop payments and liquidated damages.

72. In 2022–23, Defence enforced stop payments for the Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles and Battlefield Command System projects and received liquidated damages for the MRH90 Helicopters project.

Summary longitudinal analysis

Summary analysis — 2020–21 to 2022–23

73. Table 7 (below) summarises published PDSS data on Defence’s progress toward delivering the capabilities for the Major Projects covered in this year’s report (2022–23). The table compares current data with that reported in the two most recent editions of the MPR (2020–21 and 2021–22).

Table 7: Summary longitudinal analysis 2020–21 to 2022–23

|

|

2020–21 MPR |

2021–22 MPR |

2022–23 MPR |

|

Schedule and cost performance |

|

|

|

|

Number of Projects |

21 |

21 |

20 |

|

Total Approved Budget at 30 June |

$58.0 bn |

$59.0 bn |

$58.6 bn |

|

Total Approved Budget at final Second Pass Approval |

$54.2 bn |

$56.8 bn |

$54.0 bn |

|

Total Expenditure Against Total Approved Budget |

$28.1 bn (48.4%) |

$34.6 bn (58.7%) |

$34.4 bn (58.7%) |

|

Total In-year Expenditure Against In-year Budget |

$6.1 bn (98.4%) |

$5.7 bn (96.2%) |

$4.2 bn (98.0%) |

|

Total Budget Variation since initial Second Pass Approval 2 |

$18.3 bn (31.5%) |

$17.5 bn (29.7%) |

$22.8 bn (39.0%) |

|

Total Budget Variation since final Second Pass Approval 3 |

$3.8 bn (6.7%) |

$2.2 bn (3.9%) |

$4.6 bn (7.8%) |

|

In-year Approved Budget Variation |

-$1.0 bn (-1.7%) |

-$0.7 bn (-1.2%) |

$4.3 bn (7.9%) |

|

Total Schedule Slippage 4, 14 |

405 months (22%) |

●5 |

453 months (23%) |

|

Average Schedule Slippage across Projects 14 |

23 months |

●5 |

25 months |

|

In-year Schedule Slippage 14 |

73 months (4%) |

●5 |

101 months (5%) |

|

Risks, issues, and capability/scope 14 |

|

|

|

|

Total Reported Risks and Issues 6, 7 |

119 |

114 |

88 |

|

Expected Capability/scope (Defence Reporting) 8, 9

|

97% |

87% |

94% |

|

2% |

10% |

1% |

|

1% |

3% |

6% |

|

– 10 |

0% 11 |

0% 12,13 |

Refer to paragraphs 34 to 37 in Part 1 of this report.

Note 1: The Major Projects included in each MPR will differ, based on entry and exit criteria in the Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA, which are in Part 4 of this report. The entry and exit of projects should be considered when comparing data across years.

Note 2: See Table 4 on p. 17 for a breakdown of the major components of this variance and Table 12 on p. 61 for all real variations.

Note 3: Where a project has multiple Second Pass Approvals, the budget at Second Pass Approval reported in the header refers to the total budget in the final Second Pass Approval. The figures in this row use this methodology.

Note 4: Slippage refers to a delay in the current forecast date compared with the original government approved date of FOC. Slippage can occur due to late delivery, increases in scope or at times can be a deliberate management decision.

Note 5: The ANAO was unable to publish this analysis in 2021–22 due to the non-publication by Defence of FOC information in three PDSSs and because four projects did not have approved FOC dates. See paragraph 57.

Note 6: The grey section of the table is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s priority assurance review, due to a lack of Defence systems from which to obtain complete and accurate evidence in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the ANAO’s review.

Note 7: The figures represent the combined number of open ‘high’ and ‘extreme’ risks and issues reported in the PDSSs across all projects. Risks and issues may be aggregated at a strategic level.

Note 8: These figures represent the average predicted capability/scope delivery across the Major Projects. This method reduces the effect of an individual project’s size on the aggregate figure.

Note 9: The Hunter Class Frigate and Future Subs projects are excluded from this analysis, as their capability/scope delivery was not quantified in these years.

Note 10: The Blue reporting metric representing additional scope was not used in this year.

Note 11: Defence advised in this year that Pacific Patrol Boat Repl would deliver an additional element of capability/scope at FOC (which equated to approximately five per cent of project scope). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Note 12: Defence advised in this year that ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl would deliver an additional element of capability/scope at FOC (which equated to approximately 0.1 per cent of project scope). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Note 13: Figures do not add precisely due to rounding.

Note 14: The data pertaining to the Battlefield Command System (LAND200 Tranche 2) is excluded from this analysis due to the Auditor-General’s Qualified Conclusion, see paragraphs 2.8–2.9 and the Independent Assurance Report in Part 3 of this report.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence PDSSs across multiple years

COVID-19 impacts

74. Nine Major Projects reported disruptions to project delivery in 2022–23 caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Three of these projects reported impacts across multiple domains of cost, schedule and capability.

Cost

75. Four projects reported an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on project cost during 2022– 23. SRGB Air Defence expended previously approved contingency funds to manage increased costs associated with milestone delays, and Offshore Patrol Vessel plans to seek contingency funding to cover additional costs attributed to COVID-19. JORN Mid-Life Upgrade reported impacts on supply chain costs for some components. Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B reported an underspend attributed to delays to delivery arising from supply chain issues associated with COVID-19.

Schedule

76. Seven projects reported an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their schedule during 2022–23. These were: Joint Strike Fighter, Hunter Class Frigate, Offshore Patrol Vessel, Overlander Medium/Heavy, Peregrine, Hawkei, and Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B. All seven projects reported delays to project milestones.

Capability/scope

77. The Joint Strike Fighter project reported minor impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Verification and Validation Program. No other projects reported an impact to capability/scope delivery caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. The Major Projects Review

1.1 The Major Projects Report (MPR) contains Department of Defence (Defence) information and commentary on a selection of its major acquisition projects (Major Projects) and independent assurance and analysis of that information by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO). This chapter provides the ANAO’s overview of the scope and approach adopted for its limited assurance review of the 20 Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence for this year’s MPR. The chapter also includes information and commentary on developments in Defence’s acquisition governance processes, based on the ANAO’s review.

Review scope and approach

1.2 In 2012, the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) identified the ANAO’s review of Defence PDSSs as a priority assurance review, under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). This provided the ANAO with full access to the information gathering powers under the Act. The ANAO’s review of the individual PDSSs, which are included in Part 3 of the MPR, was conducted in accordance with the auditing standards set by the Auditor-General under section 24 of the Act through the incorporation of the Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements (ASAE) 3000 Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information, issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

1.3 The following forecast information provided by Defence is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review: Australian Industry Capability (AIC); materiel capability/scope delivery performance; risks and issues; and forecast dates. These exclusions are due to the lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and/or accurate evidence39, in a sufficiently timely manner to complete the review. Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information are required to be considered in forming the Auditor-General’s conclusion.

1.4 The ANAO’s work is appropriate for the purpose of providing an Independent Assurance Report in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards. Review of individual PDSSs is based on a limited assurance approach and is not as extensive as individual performance audits and financial statement audits conducted by the ANAO, in terms of the nature and scope of issues covered, and the extent to which evidence is required by the ANAO. Consequently, the level of assurance provided by this review, in relation to the 20 major Defence equipment acquisition projects, is less than that provided by the ANAO’s program of performance and financial statement audits.

1.5 In addition to the assurance review, the ANAO considers developments in Defence’s acquisition governance processes (information and commentary on governance issues appears in this chapter) and undertakes analysis of Defence’s PDSSs (information and commentary on systemic issues, and in-year and longitudinal analysis for the Major Projects, appears in the next chapter).

1.6 The ANAO’s review was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $1.8 million.

Review methodology

1.7 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the individual Defence PDSSs included:

- evaluation of the governance and oversight in place to ensure appropriate project management;

- assessment of the systems and controls that support project financial management, risk management and project status reporting within Defence;

- examination of each PDSS and the documents and information relevant to them;

- review of relevant processes and procedures used by Defence in the preparation of the PDSSs;

- meetings with personnel responsible for the preparation of the PDSSs and management of the projects;

- analysis of project information, for example, cost, AIC and schedule variances;

- taking account of industry contractor comments provided on draft PDSS information;

- assessment of the assurance by Defence managers attesting to the accuracy and completeness of the PDSSs;

- examination of representations by the Chief Finance Officer supporting the project financial assurance and contingency statements;

- examination of any representations by the Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) supporting the non-disclosure of information for publication after security review;

- examination of confirmations, provided by the Capability Managers, relating to each project’s progress toward Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR), Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC); and

- examination of the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, including significant events occurring post 30 June 2023, and management representations by the Secretary of Defence.

1.8 The ANAO’s review of Defence PDSSs also focused on project management and reporting arrangements contributing to the overall governance of the Major Projects. The ANAO considered:

- developments in acquisition governance (see paragraphs 1.17 to 1.67, below);

- the financial framework, particularly as it applies to the project financial assurance and contingency statements (see Section 2 of the PDSSs);

- schedule management and test and evaluation processes (see Section 3 of the PDSSs);

- materiel capability/scope delivery forecast assessments, including Defence statements of the likelihood of delivering capabilities, particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones (see Section 4 of the PDSSs);

- the Defence Enterprise Risk Management Framework, and the completeness and accuracy of major risks and issues data (see Section 5 of the PDSSs); and

- the impact of acquisition issues on sustainment to ensure the PDSS is a complete and accurate representation of the acquisition project.

1.9 This review activity informed the ANAO’s understanding of the systems and processes supporting the PDSSs for the 2022–23 review period. It also highlighted issues in those systems and processes that warrant attention.

Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs)

Preparation and review processes

1.10 A quality PDSS preparation process by Defence will reduce the risk of untimely and/or inaccurate reporting and will reduce the incidence of multiple reviews for the same project.

1.11 As part of the MPR process, Defence’s PDSS preparers receive guidance on expectations and have multiple opportunities to refine the PDSSs before the ANAO finalises its assurance review. The ANAO and Defence MPR team conduct educative activities, including visits, with Major Project teams before 30 June40 to ensure awareness of the MPR Guidelines and mitigate errors in PDSS preparation. The ANAO also conducts a preliminary assessment of the early iteration of each Defence PDSS (generally prepared before 30 June) and the outcome is provided to Defence. The ANAO’s expectation for the 2022–23 MPR was to base its assurance review on the third post–30 June 2023 version of the PDSS submitted by Defence.41

1.12 This year the ANAO has observed Defence implement a new internal management methodology and quality assurance approach for the MPR. This has involved the creation of standardised PDSS templates, some standardised financial reports and the development of internal guidance materials for projects preparing PDSSs. Nonetheless, the ANAO also observed ongoing quality issues relating to Defence’s preparation of iterations of PDSSs for ANAO review, in the post–30 June period.

1.13 These quality issues included instances where internal project reporting was accurate, however was not accurately reflected in the PDSSs. These issues related to elements of financial data, schedule milestone dates, quantities of materiel, and risks and issues. The ANAO continued to advise Defence of the material errors and quality issues it identified in the PDSSs. This process continued after what was intended to be the ANAO’s third and final review of the PDSSs. While this additional activity provided Defence with a further opportunity to prepare quality PDSSs, a number of unresolved material errors persisted in some PDSSs and this has informed the ANAO assurance review and the Auditor-General’s conclusion (see the Independent Assurance Report found in Part 3 of this report).42

1.14 Further efficiency can be gained through Defence process standardisation, including the development and generation of standard reports from Defence’s Financial Management and Information System (FMIS) and Predict! (the Defence risk management system), and continued engagement and review by Defence leaders.

Defence reporting in PDSSs – lessons learned and non-disclosures

1.15 The MPR Guidelines require Defence PDSSs to include information on project lessons (at the strategic level) that have been learned, and ‘systemic lessons’ where they are applicable to the project. This year Defence reassessed its approach to reporting on Lessons Learned in its PDSSs and has removed all content previously reported in PDSSs.43 The PDSS for each Major Project now reports on a selection of three Project Lessons, and a summary of categories of lessons against the MPR Guidelines. This change is discussed further in paragraphs 1.93 to 1.103. As summarised in paragraphs 27 to 28, the Auditor-General has expressed a qualification of this matter in the Independent Assurance Report (found in Part 3 of this report), on the basis that the information disclosed in 2022-23 does not satisfy the requirements of the Guidelines and is materially inconsistent with evidence obtained by the ANAO.

1.16 Defence also advised the ANAO of its decision that certain information is not for publication and has not been included in the relevant PDSSs for 12 projects. The not for publication information includes forecast dates, capability delivery information and variance information. The affected PDSSs are set out in Tables 2 and 3 at pages 7 to 11. Commentary provided by the Secretary of Defence on this matter is reproduced at paragraphs 20 to 21.

Acquisition governance

1.17 Consistent with previous years, the ANAO considered Defence’s Major Project acquisition governance processes when planning and conducting the review for the 2022–23 MPR. While some of these processes are now established, others continue to mature or require further development to achieve their intended impact.

Defence Independent Assurance Reviews

1.18 The Defence Independent Assurance Review (IAR) process provides the Defence Senior Executive with assurance that projects and products will deliver approved objectives and are prepared to progress to the next stage of activity. These management-initiated reviews consider a project’s status while sufficient time remains for corrective action to be implemented.44

1.19 IARs are intended to commence at project initiation and are conducted through to FOC; for higher-complexity projects, ideally on an annual basis. They are an important input to key acquisition and sustainment decision points or milestones.45

1.20 Thirteen of the 20 Major Projects had an IAR completed during 2022–2346, which formed evidence for the ANAO’s assessment.

Projects of Concern

1.21 The Projects of Concern (POC) process is intended to focus the attention of the highest levels of government, Defence and industry on remediating problem projects.47 There is also a related Projects of Interest (POI) process. At 30 June 2023 two MPR projects, MRH90 Helicopters and Civil Military Air Management System (CMATS), were continuing Projects of Concern.

1.22 The Statement by the Secretary of Defence details significant events occurring post 30 June 2023. The Secretary reported that:

- Offshore Patrol Vessel (SEA 1180 Phase 1) was announced as a POC on 20 October 2023; and

- Protected Mobility Vehicles Light (Hawkei) (LAND 121 Phase 4) was elevated to a POI in July 2023.

MRH90 Helicopters project

1.23 Last year’s MPR reported that the MRH90 Helicopters project was placed on the POC list in November 2011 due to contractor performance relating to significant technical issues preventing the achievement of milestones on schedule.48

1.24 In December 2021, the government announced plans to investigate other aircraft types to immediately replace the MRH90 helicopter fleets. Following this decision, Navy commenced project SEA 9100 Phase 1 Improved Embarked Logistics Support Helicopter Capability to replace its fleet of six MRH90 helicopters with 12 MH-60R (Romeo) Seahawk helicopters for operations on the Navy Amphibious and Afloat Support fleet. An additional helicopter (total 13) will also be acquired to remediate a fleet loss on operations in October 2021, expanding the MH-60R fleet to 36 in total. In May 2022, Navy ceased operation of its MRH90 fleet. In January 2023, the government announced the acquisition of 40 UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters to replace Army’s MRH90 fleet.

1.25 Following an IAR of the project conducted in April 2022, the Deputy Secretary of Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) directed that the project was to remain a POC until project closure.

1.26 In this year’s PDSS, Defence reported that at 30 June 2023, FMR had been delayed to September 2023, nine months later than stated last year, with a total of 110 months slippage over the life of the project. In addition, FOC would not be achieved as the MPRH-90 had not been able to meet the ADF’s capability requirements and was reporting 100 per cent ‘red’ in Section 4.1 of the PDSS, in relation to materiel capability delivery performance.

1.27 In 2023 there were two incidents, in March and July, involving Army MRH90 helicopters, which have resulted in the fleet’s permanent grounding and a subsequent government decision that MRH90 helicopters will not return to flying operations prior to the planned withdrawal date in December 2024.49

1.28 In the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, which details significant events occurring post 30 June 2023, the Secretary reported that: ‘On 29 September 2023, the Government announced that the MRH90 Taipan helicopters will not return to flying operations before their planned withdrawal date of December 2024. On 13 November 2023, Minister for Defence Industry approved removal of the project from Projects of Concern list.’ FOC will not be declared for the MRH90 helicopters.

CMATS project

1.29 The CMATS project was a POC between August 2017 and May 2018 due to protracted negotiations leading to a delay in entering the contract. Following contract signature, CMATS was managed as a POI.

1.30 In last year’s MPR the ANAO reported that in September 2021, the Minister for Defence made a written direction that CMATS return to the POC list. Defence did not update internal reporting, such as the Acquisition and Sustainment Update and its POC list, in response to the Minister’s direction. In September 2022 Defence advised the ANAO that ‘the decision to declare this project a Project of Concern required extensive consultation with Airservices50 and with the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, which needed to occur post the Ministers 25 August 2021 decision.’ The ANAO also observed that Defence guidance stated that ‘entry to … the Projects of Concern list is decided by the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Defence Industry’.51 Defence was unable to provide the ANAO with evidence of any limitation on the Minister’s decision-making authority, or evidence of an updated policy or guidance.

1.31 This matter was subsequently considered by the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), which recommended that Defence update its internal governance to require that decisions for projects to enter the POC or POI list be actioned in a timely manner, taking no more than three months between decision and implementation.52

1.32 This year’s PDSS reports that CMATS has continued to experience schedule delays to its IOC dates and the contractor has been unable to provide authoritative forecast dates for system acceptance milestones. At 30 June 2023 delivery of a schedule remained an outstanding action for the contractor. The FOC date remains at Quarter 1 2028, which is over four years after the original planned date.

1.33 CMATS was publicly announced as a POC by the Minister for Defence Industry on 27 October 2022. It has been monitored by Defence and reported on to the Minister for Defence Industry in that context.

Governance – POC and POI

1.34 The governance of Defence’s POC and POI processes has been considered by the JCPAA on a number of occasions in recent years.

1.35 Most recently, the JCPAA considered acquisition governance issues during its Inquiry into the Defence Major Projects Report 2020–21 and 2021–22 and Procurement of Hunter Class Frigates.53 As discussed in paragraphs 39 and 40 (above), Recommendation 1 of the Committee’s June 2023 interim report for the inquiry was that:

The Committee recommends that the Department of Defence updates internal governance to require decisions for projects to enter the Projects of Interest or Projects of Concern list be actioned in a timely manner, taking no more than three months between decision and implementation.

1.36 The JCPAA also considered POC and POI governance issues in its earlier Report 489 Defence Major Projects Report 2019-20, which was tabled in March 2022. Recommendation 2 of that report was that:

The Committee recommends that the Department of Defence revisit its effort to provide criteria for projects to enter and exit the Projects of Concern and Projects of Interest categories and create processes for their consistent application, enabling these to be reviewed as part of the next MPR, and that the ANAO gives further consideration to these issues in the next MPR.

1.37 The JCPAA followed-up on Recommendation 2 in its June 2023 interim report on the MPR and made the following observations on governance issues.

- In October 2022, the Minister for Defence announced that the government would strengthen the POI process and that in March 2023, Defence had released the ‘Delivery Group Performance Management and Reporting, and Management of Projects of Interest and Concern Policy’ in direct response to this announcement.

- The policy provided guidance on the identification of, and response to, underperformance, through a tiered system of elevation, enabling timely advice to the relevant decision makers, and the prompt remediation planning for projects and products.

- Defence had confirmed that this new policy framework formalised the entry and exit criteria for POC and POI.

- A Defence submission to the inquiry on the implementation of Recommendation 2 stated that Defence considered no further action was required to implement the recommendation due to the revised POI policy.54