Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2013-14 Major Projects Report

The report objective is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of 30 selected Major Projects, as reflected in the Statement by the Chief Executive Officer Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO), and the Project Data Summary Sheets prepared by the DMO, in accordance with the Guidelines endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.

Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

Abbreviations

|

ADF |

Australian Defence Force |

|

ANAO |

Australian National Audit Office |

|

ASAE |

Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements |

|

CEO DMO |

Chief Executive Officer, Defence Materiel Organisation |

|

CFO DMO |

Chief Finance Officer, Defence Materiel Organisation |

|

DCP |

Defence Capability Plan |

|

DMO |

Defence Materiel Organisation |

|

FMR |

Final Materiel Release |

|

FMS |

Foreign Military Sales |

|

FOC |

Final Operational Capability |

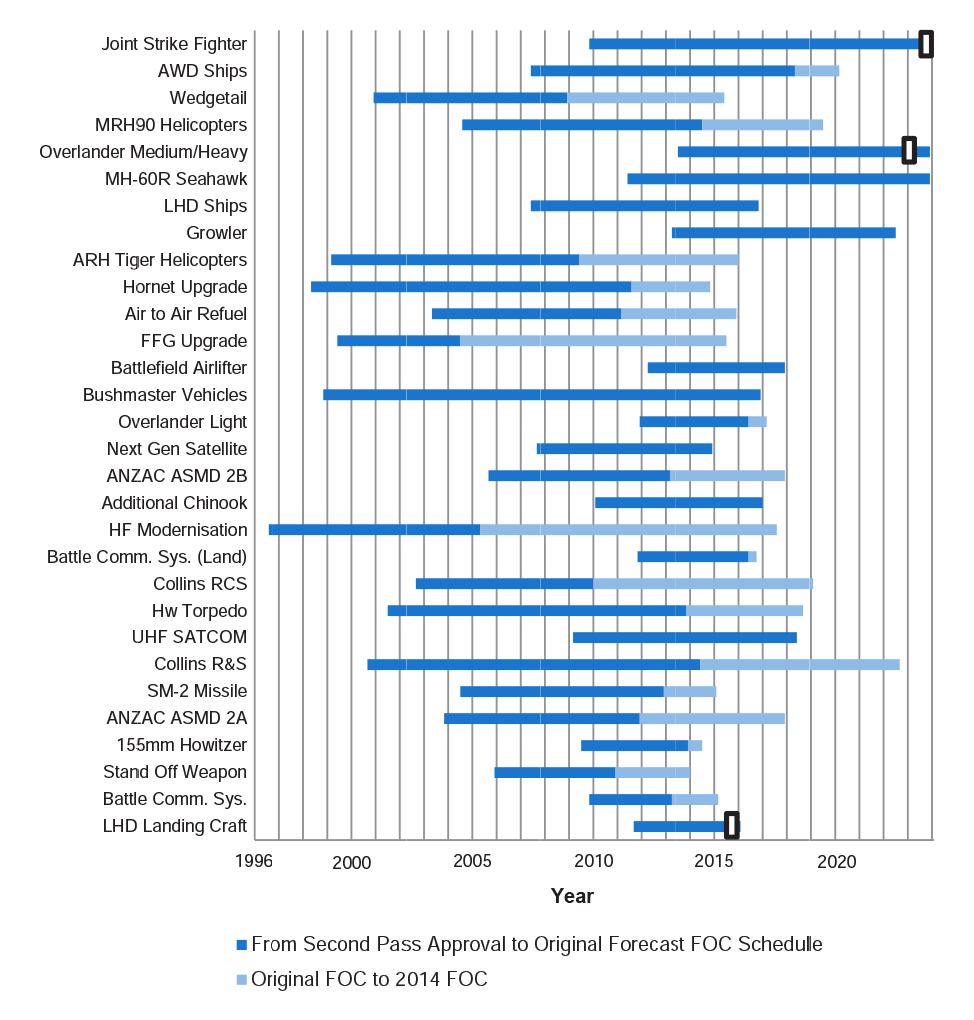

|

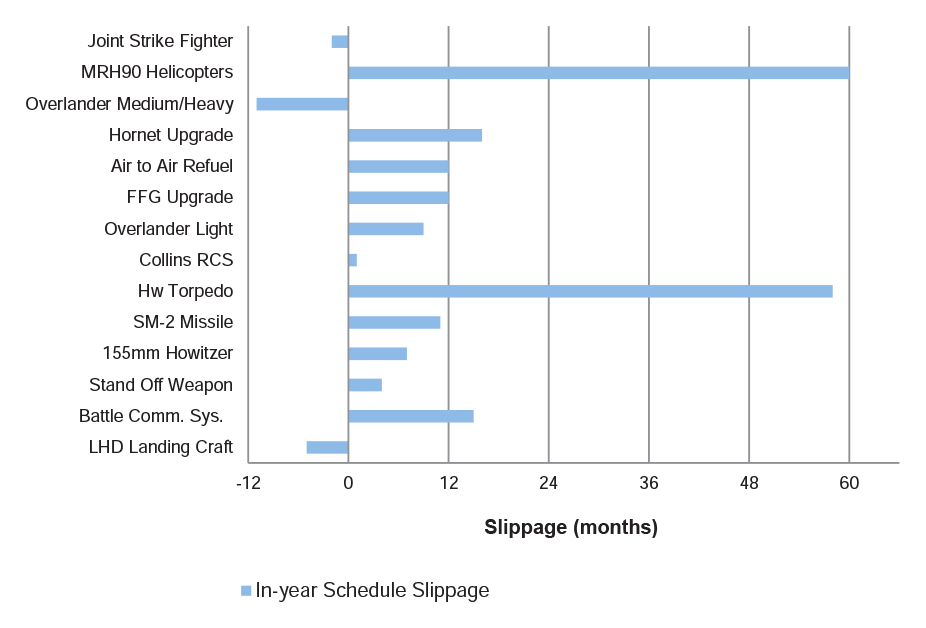

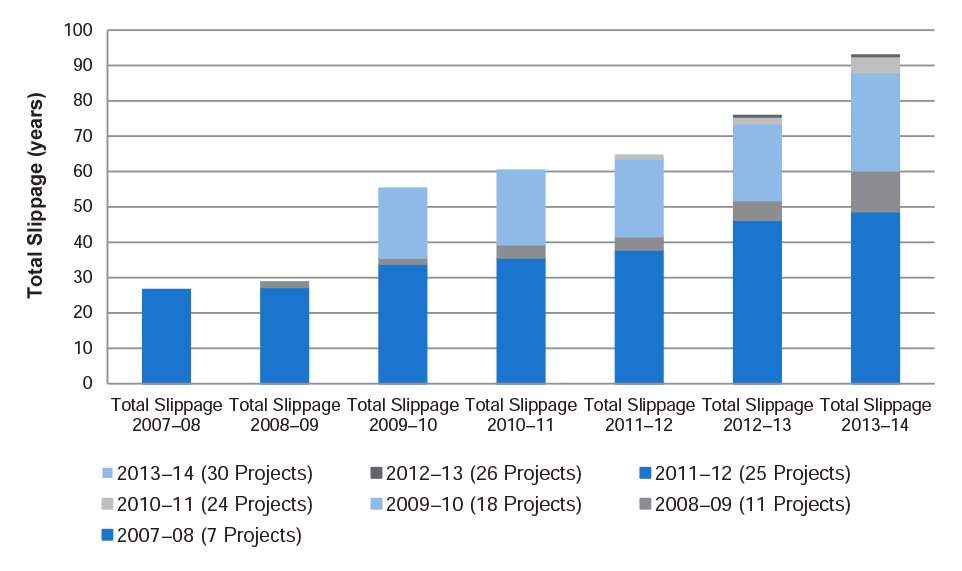

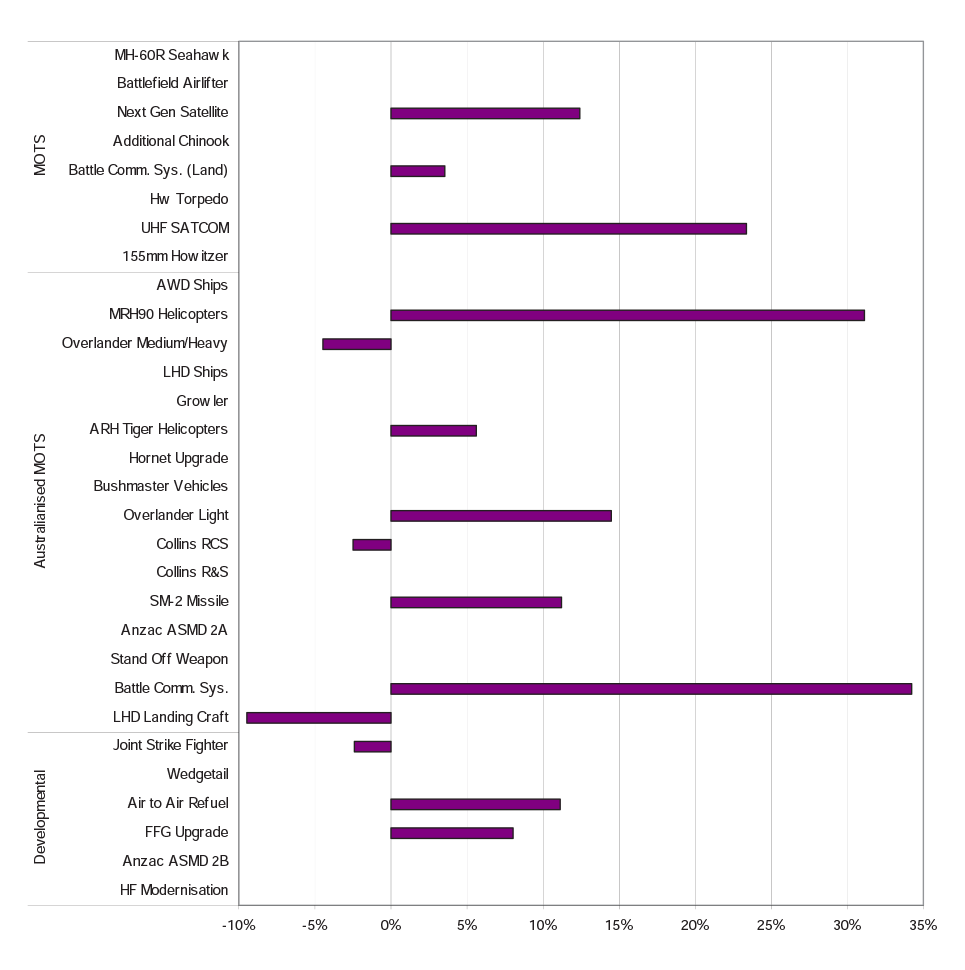

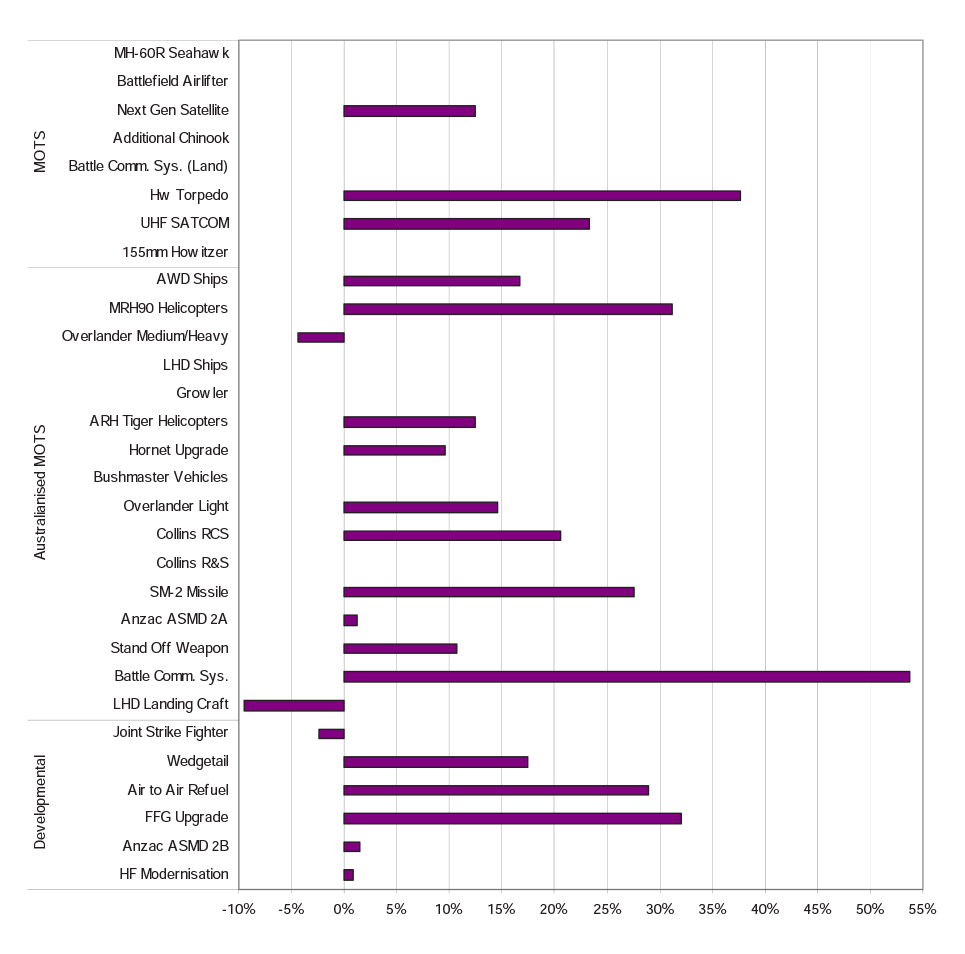

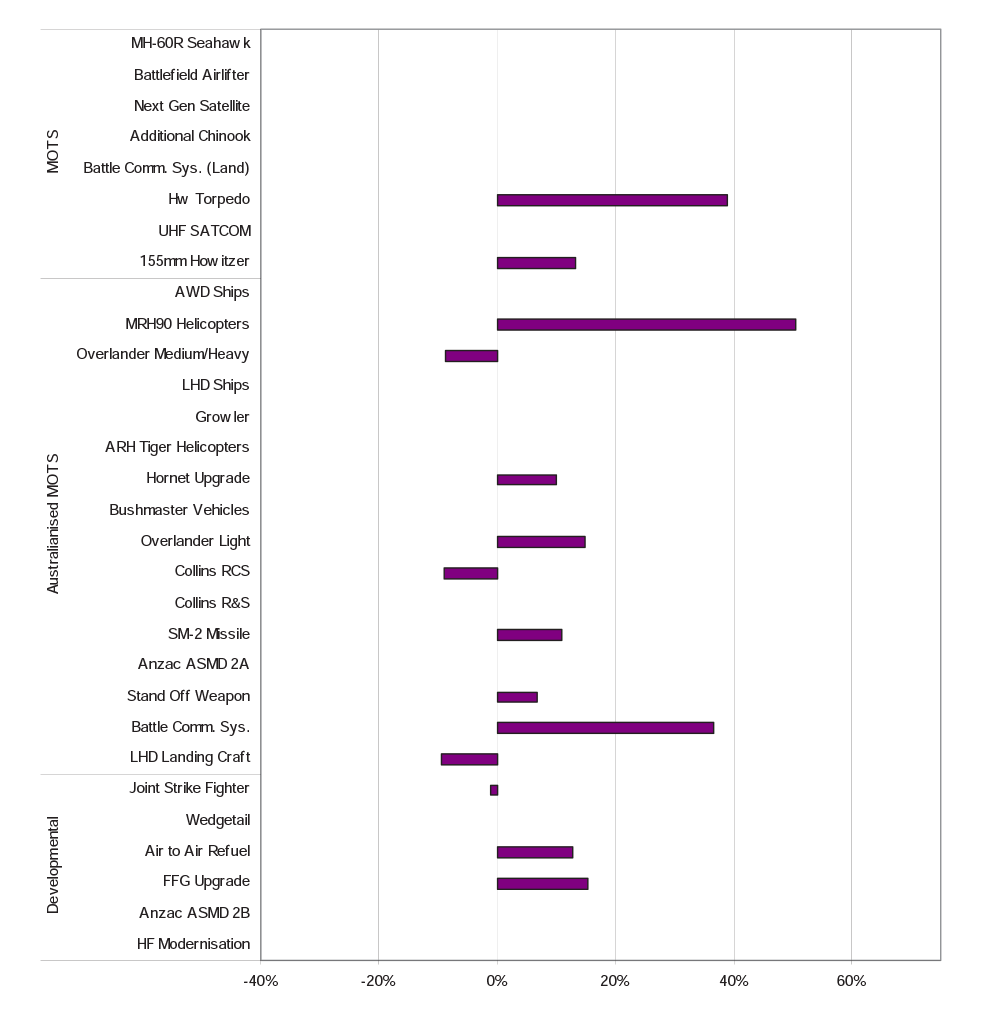

IMR |

Initial Materiel Release |

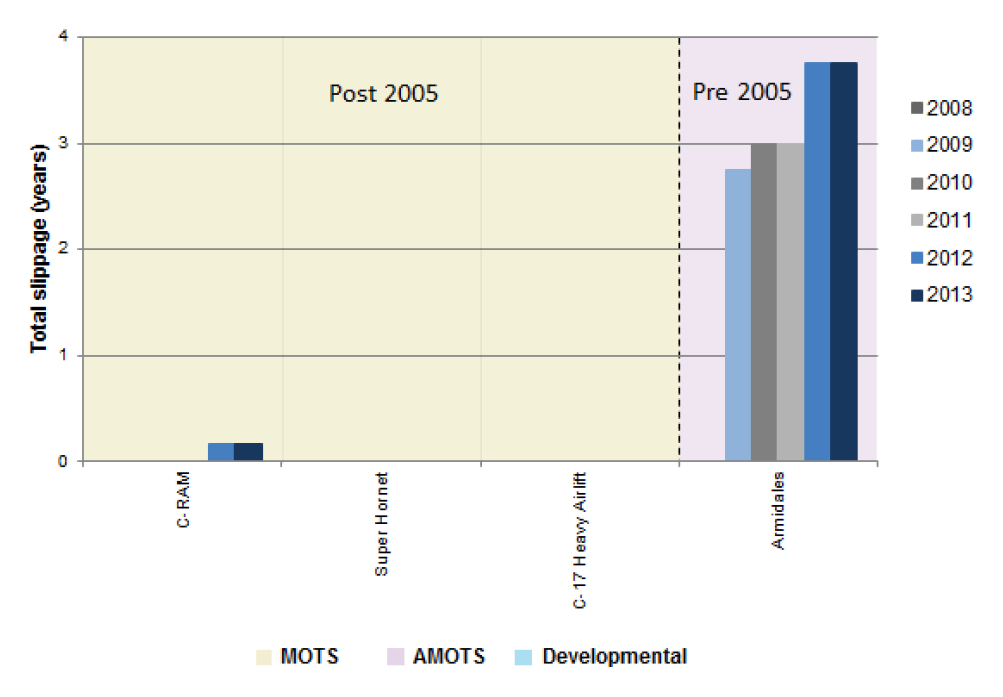

|

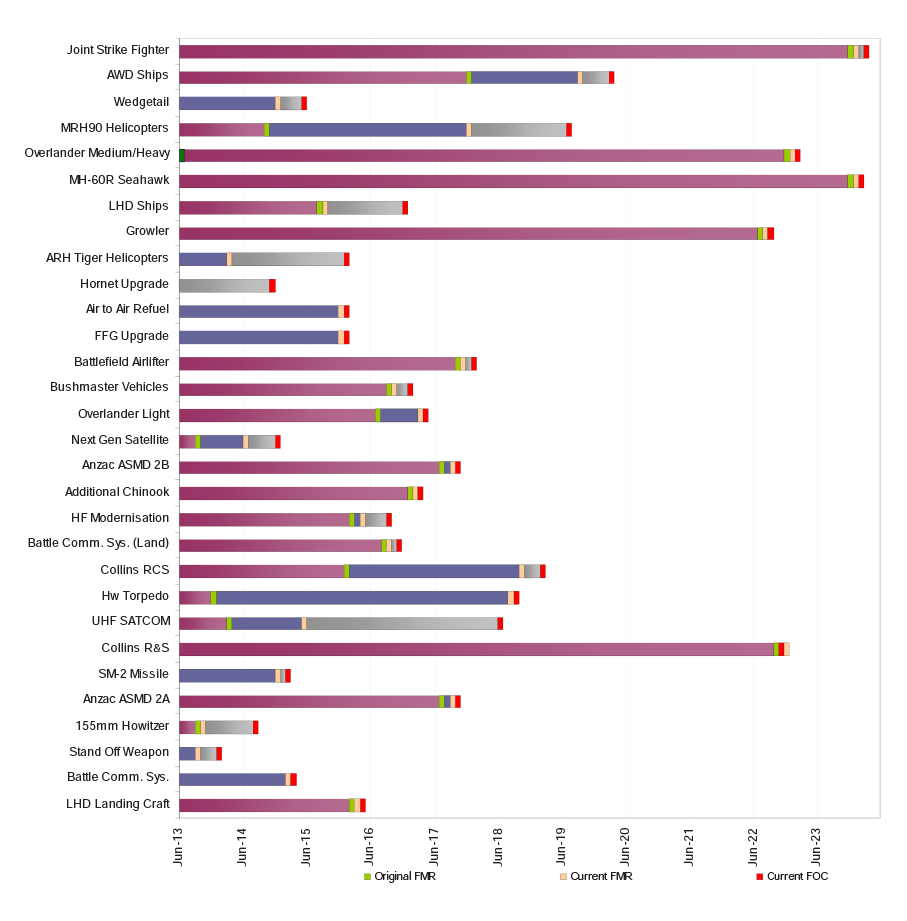

IOC |

Initial Operational Capability |

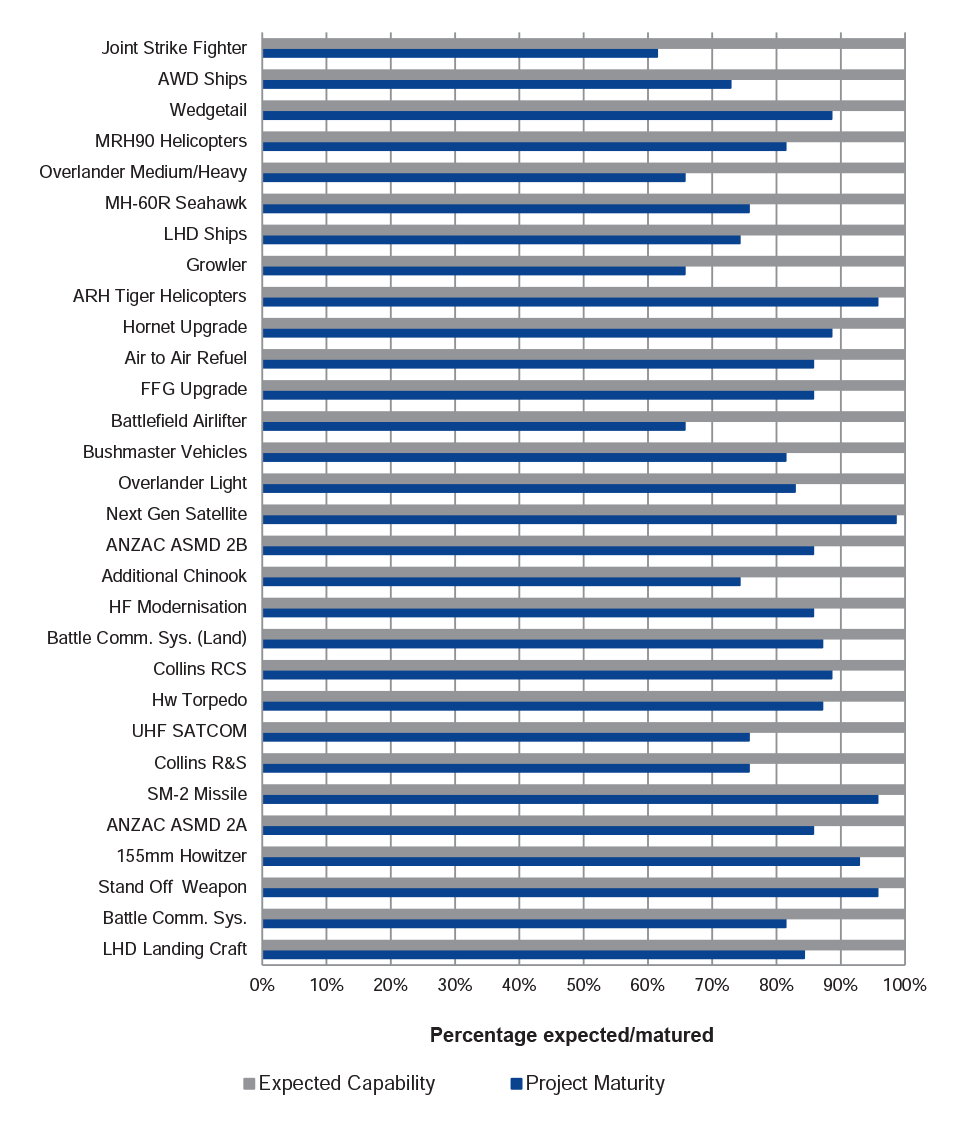

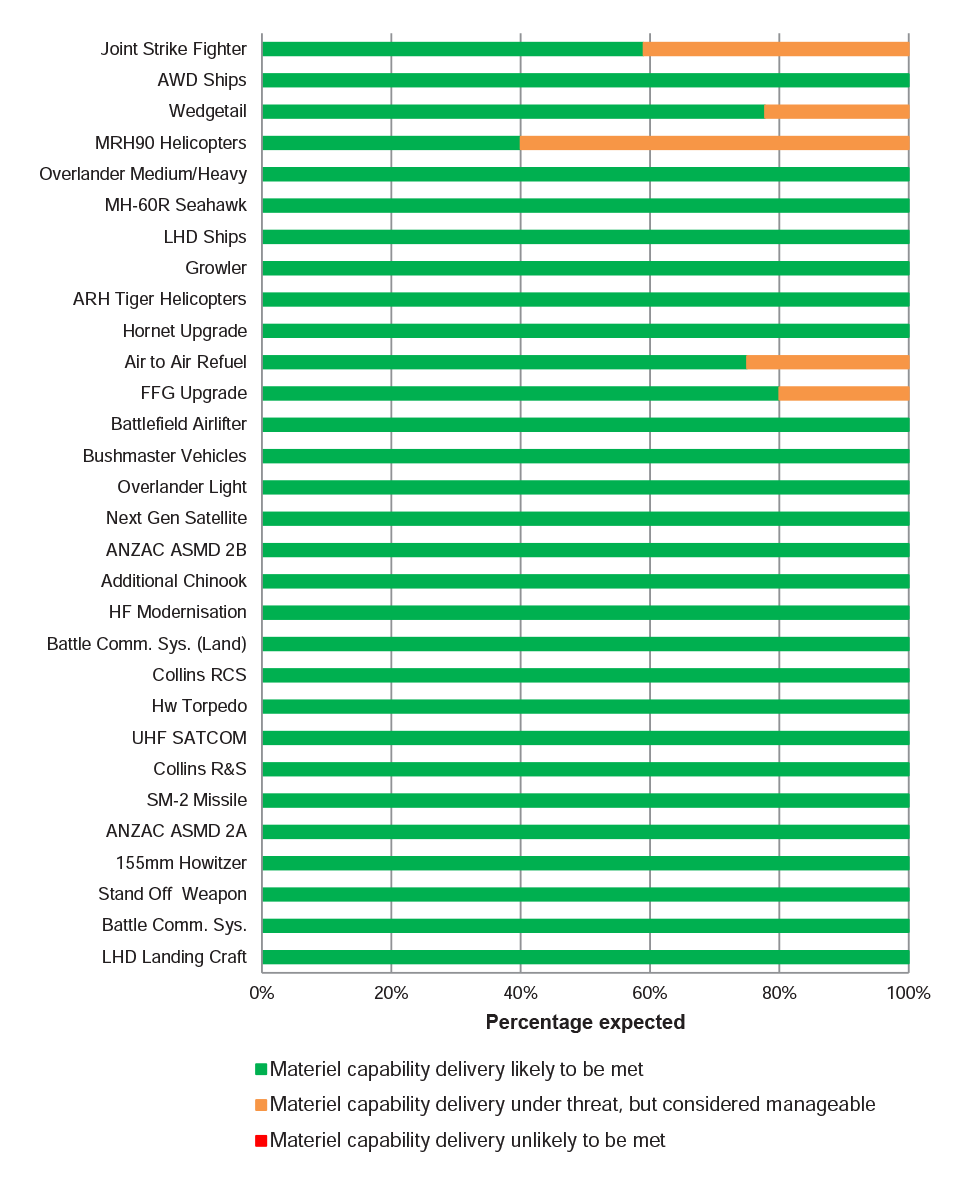

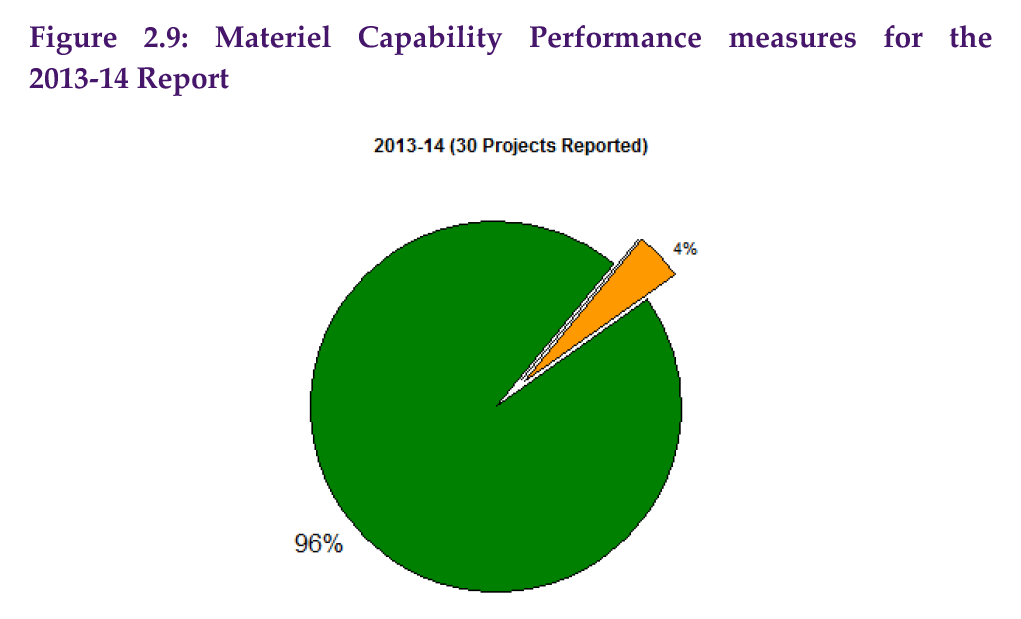

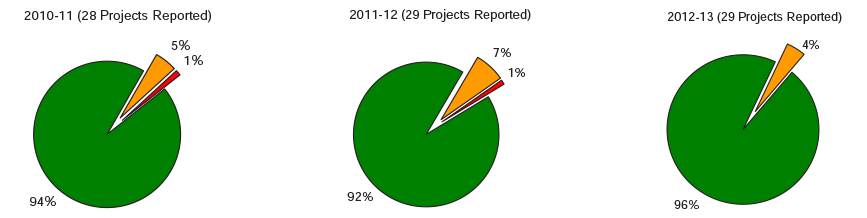

|

JCPAA |

Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit |

|

JPD |

Joint Project Directive |

|

MAA |

Materiel Acquisition Agreement |

|

Major Projects |

Major Defence equipment acquisition projects |

|

MOTS |

Military-Off-The-Shelf |

|

MOU |

Memorandum Of Understanding |

|

MPR |

Major Projects Report |

|

MRM |

Materiel Release Milestone |

|

MRS |

Monthly Reporting System |

|

PDSS |

Project Data Summary Sheet |

Note: A full list of the Major Projects and their abbreviations are included in Part 1, at page 7, of this report.

Auditor-General’s Foreword

The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) supports the capacity and capability of the Australian Defence Force by undertaking important acquisition and sustainment activities. This important work is the subject of this, the seventh Major Projects Report (MPR), which continues the annual review and analysis by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) on the progress of selected major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects), managed by the DMO.

This report builds on the earlier work by the DMO and the ANAO to improve the transparency of, and accountability for, the status of Major Projects for the benefit of the Parliament, the Government and other stakeholders.

The management of Major Projects is complex and, for this reason, it is a major challenge for the DMO to deliver the required capability on schedule and within budget. Consistent with previous years, schedule slippage remains a key focus for the DMO, particularly for projects regarded as developmental. However, given the ongoing interest in all aspects of the delivery of Major Projects, the ANAO will continue to monitor delivery in terms of cost, schedule and capability.

In such a complex environment, the ongoing support of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) has been important to the development of the MPR, providing guidance and insights from their considerations. Each year the JCPAA endorses the Guidelines for the review, and provides direction and recommendations to assist the development of future MPRs.

As previously, this year’s review continued the strong working relationship between the ANAO and the DMO. Other key stakeholders within the Department of Defence, and in particular the Capability Managers, and industry stakeholders, also provided valuable input to assist with the review.

Ian McPhee

8 December 2014

Summary

Introduction

1. Major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects) remain the subject of considerable parliamentary and public interest, in view of their high cost and impact on the economy, contribution to national security and the challenges involved in completing them within budget, on time and to the required level of capability.

2. The proposed 20151 Defence White Paper is expected to consider the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF’s) priorities for future capability investment for the Commonwealth. These considerations will concern the acquisition of new submarines and frigates, as well as the replacement of the land vehicle fleet, and are foreshadowed to involve some of the most significant investment decisions in the Commonwealth’s history.2 In addition, the Government has commissioned the Defence First Principles Review which is aimed at delivering ‘a more commercially astute and focused materiel acquisition and sustainment capability’.3 The findings of this review are expected to inform the development of the White Paper.

3. The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) provides support to ADF operations through the acquisition and sustainment of ADF capabilities4 and expended some $4.1 billion on major and minor capital acquisition projects in 2013–14.5

4. However, acquisitions by the DMO alone do not generate new capability for the ADF until they have been successfully introduced into service. The overarching responsibility for the introduction into service of Major Projects, for example, provision of personnel, training and command, normally resides within other areas of the Australian Defence organisation.6 However, while the DMO’s acquisition role is only part of the introduction into service of new capability, it is a significant one.

The 2013–14 Major Projects Report

5. This seventh Major Projects Report (MPR) covers 30 of the DMO’s Major Projects and is the first report covering this many projects (2012–13 and 2011–12: 29, and 2010–11: 28). This report builds on the earlier work to improve the transparency of, and accountability for, the status of Major Projects, and is supported by the commitment of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), ‘…to maximise transparency and accountability in the Defence acquisition process for major projects managed by DMO.’7

6. The Australian National Audit Office‘s (ANAO’s) review of Major Projects in the MPR is completed in conjunction with the regular program of performance and financial statement audits conducted within the Defence portfolio. While by its nature, the report is not as in depth as a performance audit, it provides an opportunity to analyse data across a consistent range of projects over time. The benefits of this analysis have been noted by a variety of stakeholders, including Ministers, Parliamentary Committee members, industry and the media.

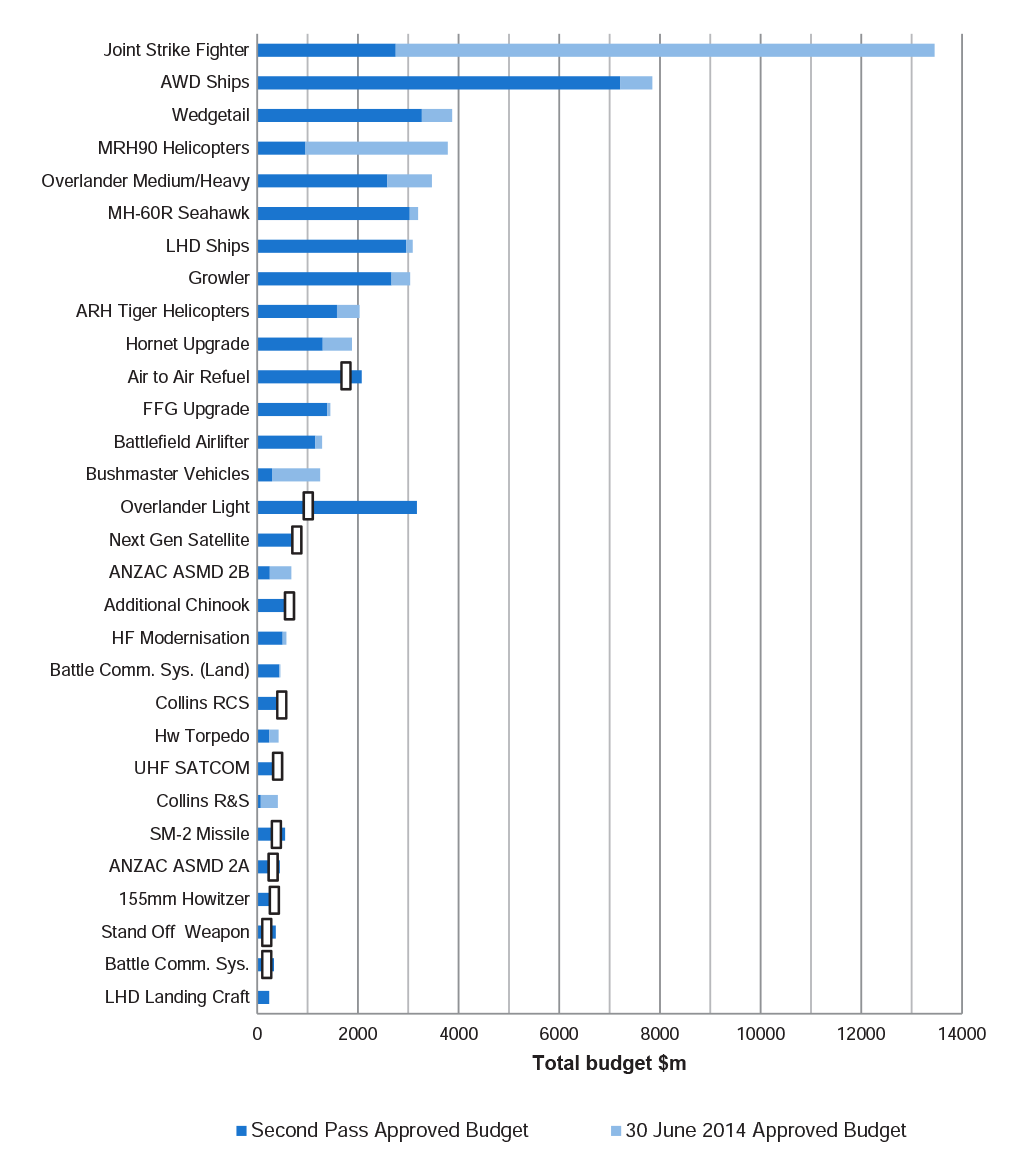

The 2013–14 Major Projects

7. Projects included in the MPR are selected based on criteria included in the 2013–14 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the JCPAA. These criteria provide a selection of the most significant Major Projects managed by the DMO, on behalf of the ADF. The total approved budget for the Major Projects included in the 2013–14 MPR is approximately $59.4 billion, covering nearly 63 per cent of the budget within the Approved Major Capital Investment Program of $94.7 billion.8

8. The projects and their approved budgets are listed in Table 1, below.

Table 1: MPR projects and approved budgets at 30 June 2014

|

Project Number (Defence Capability Plan) |

Project Name (on DMO advice) |

DMO Abbreviation (on DMO advice) |

Approved Budget $m |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability |

Joint Strike Fighter |

13 455.5 |

|

SEA 4000 Phase 3 |

Air Warfare Destroyer Build |

AWD Ships |

7 847.9 |

|

AIR 5077 Phase 3 |

Airborne Early Warning and Control Aircraft |

Wedgetail |

3 873.1 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6 |

Multi-Role Helicopter |

MRH90 Helicopters |

3 785.1 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3B |

Medium Heavy Capability, Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers |

Overlander Medium/Heavy 1 |

3 469.0 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 8 |

Future Naval Aviation Combat System Helicopter |

MH-60R Seahawk |

3 196.9 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 4A/4B |

Amphibious Ships (LHD) |

LHD Ships |

3 089.4 |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 3 |

EA-18G Growler Airborne Electronic Attack Capability |

Growler 1 |

3 036.6 |

|

AIR 87 Phase 2 |

Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter |

ARH Tiger Helicopters |

2 033.0 |

|

AIR 5376 Phase 2 |

F/A-18 Hornet Upgrade |

Hornet Upgrade |

1 881.3 |

|

AIR 5402 |

Air to Air Refuelling Capability |

Air to Air Refuel |

1 821.4 |

|

SEA 1390 Phase 2.1 |

Guided Missile Frigate Upgrade Implementation |

FFG Upgrade |

1 452.6 |

|

AIR 8000 Phase 2 |

Battlefield Airlift – Caribou Replacement |

Battlefield Airlifter 1 |

1 289.5 |

|

LAND 116 Phase 3 |

Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle |

Bushmaster Vehicles |

1 250.4 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3A |

Field Vehicles and Trailers |

Overlander Light |

1 020.5 |

|

JP 2008 Phase 4 |

Next Generation SATCOM Capability |

Next Gen Satellite |

869.3 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2B |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

678.4 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 5C |

Additional Medium Lift Helicopters |

Additional Chinook |

617.2 |

|

JP 2043 Phase 3A |

High Frequency Modernisation |

HF Modernisation |

580.1 |

|

JP 2072 Phase 2A |

Battlespace Communications System |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) |

460.1 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 4A |

Collins Replacement Combat System |

Collins RCS |

450.1 |

|

SEA 1429 Phase 2 |

Replacement Heavyweight Torpedo |

Hw Torpedo |

426.6 |

|

JP 2008 Phase 5A |

Indian Ocean Region UHF SATCOM |

UHF SATCOM |

419.1 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 3 |

Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability |

Collins R&S |

411.7 |

|

SEA 1390 Phase 4B |

SM-1 Missile Replacement |

SM-2 Missile |

407.3 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2A |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

386.9 |

|

LAND 17 Phase 1A |

Artillery Replacement |

155mm Howitzer |

336.1 |

|

AIR 5418 Phase 1 |

Follow On Stand Off Weapon |

Stand Off Weapon |

317.4 |

|

LAND 75 Phase 3.4 |

Battlefield Command Support System |

Battle Comm. Sys. |

314.8 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 3 |

Amphibious Watercraft Replacement |

LHD Landing Craft 1 |

239.9 |

|

Total |

59 417.2 |

||

Source: See the Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3, from page 175, of this report.

Note 1: Overlander Medium/Heavy, Growler, Battlefield Airlifter and LHD Landing Craft are included in the MPR program for the first time in 2013–14.

Report objective and structure

9. The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of selected Major Projects, as reflected in the Statement by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) DMO, and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs), prepared by the DMO. Assurance from the ANAO’s review of the preparation of the PDSSs is conveyed in the Auditor-General’s Independent Review Report, prepared pursuant to the endorsed Guidelines, and included in Part 3 of this report (pp. 165–542) along with the aforementioned Statement by the CEO DMO and PDSSs.

10. Excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review is PDSS data on projects’ budget adequacy, the identification of Risks and Issues, the Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance, and ‘forecasts’ of future dates and the achievement of future outcomes. By its nature, this information relates to future events and depends on circumstances that have not yet occurred or may not occur, or may be impacted by events that have occurred but have not yet been identified. Accordingly, the conclusion of this review does not provide any assurance in relation to this information.

11. The ANAO’s analysis on the three key elements of the PDSSs—cost, schedule and the progress towards delivery of required capability, in particular, longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects over time, are contained in Part 1 (pp. 1–98). The ANAO’s analysis on other elements of the PDSSs, for example, project maturity and elements excluded from the scope of the formal review, are also included in this part, to provide readers with a balanced perspective over all key acquisition elements.

12. Further insights and context by the DMO on issues highlighted during the year are contained in Part 2 (pp. 99–164)—although not included within the scope of the review by the ANAO.

13. Part 4 includes the Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA (pp. 543–572).

14. Figure 1, below, depicts the key parts of this report. To assist in conducting inter-report analysis, the presentation of data remains largely consistent and comparable with the 2012–13 MPR.

Figure 1: Report structure

Refer to paragraphs 9 to 13 in Part 1, at page 8, of this report.

15. For each Major Project, a corresponding PDSS includes detailed information on project performance: the approved budgeted cost and expenditure; schedule progress; the DMO’s assessment of progress toward delivering those aspects of key capabilities for which the DMO is responsible; major risks and issues; maturity scores; and lessons learned. This information has been prepared by the DMO in accordance with the Guidelines as endorsed by the JCPAA. Additionally, as projects appear in the MPR for multiple years, changes to the PDSS from the previous year are depicted in bold purple text.

16. Each PDSS comprises:

- Project Header—including name; capability and acquisition type; approval dates; total approved and in-year budgets; stage; complexity; and image;

- Section 1—Project Summary: including description; current status, including a financial assurance and contingency statement; context, including background, unique features and major risks and issues; and other current sub-projects;

- Section 2—Financial Performance: including the project’s budget and expenditure, as well as variations to the budget; in-year variances between budgeted and actual expenditure; and major contracts in place (in addition to quantities delivered as at 30 June 2014);

- Section 3—Schedule Performance: provides information on the design development; test and evaluation process; and forecasts and achievements against key project milestones including Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR), Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC)9 10;

- Section 4—Project Cost and Schedule Status: represents the project’s cost and schedule status in a graphical format as at 30 June 2014;

- Section 5—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance: provides a summary of the DMO’s assessment of its progress on delivering key capabilities;

- Section 6—Major Risks and Issues: outlines the major risks and issues of the project;

- Section 7—Project Maturity: provides a summary of the project maturity as defined by the DMO and a comparison against the benchmark score;

- Section 8—Lessons Learned: outlines the key lessons that have been learned at the project level (further information on lessons learned by the DMO are included in the DMO’s Appendix 3); and

- Section 9—Project Line Management: details current project management responsibilities within the DMO.

17. Consistent with the Guidelines, information of a classified nature has been excluded from the PDSSs.

The role of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit

18. Influential in establishing the MPR, the JCPAA has taken an active role in the development and review of the MPR program. Each year, the Committee considers the draft Guidelines, incorporating the selection of projects for review, and provides the Committee’s views in relation to the Guidelines’ content and development, prior to their endorsement. Following endorsement by the Committee, the Guidelines provide the basis for the DMO’s preparation of the PDSSs and the criteria for the ANAO’s review.11

19. The main change to the 2013–14 Guidelines was the inclusion of a statement within each PDSS in relation to whether a project has, or has not, applied contingency funds during the year. The DMO applies contingency to known and emergent risks as a part of standard risk management processes12, however, the application of contingency does not necessarily result in expenditure, unless risks materialise and require action to be taken. Although the amount of contingency funds applied, or whether the applied contingency funds were expended does not have to be disclosed, this amendment will provide readers with the opportunity to identify, at a minimum, projects that have had contingency funds applied during the financial year.

20. Subsequent to the tabling of the MPR in Parliament each year, the JCPAA considers the inclusion of the report in its schedule of review. In March 2014, the JCPAA held a public hearing into the results of the 2012–13 review and in May 2014 the Committee published Report 442, Review of the 2012–13 Defence Materiel Organisation Major Projects Report. The JCPAA’s recommendations are set out below13:

Recommendation 1

The Committee recommends that starting from the 2013–14 Major Projects Report, the Defence Materiel Organisation and the Australian National Audit Office publish expanded information on each Major Project’s budget estimates and actual expenditure during the financial year. Additional details for each Major Project could include:

- Comparison of variation citing specific dollar amounts;

- Percentage of variance; and

- Overall totals and averages, where calculable.

Additionally, ANAO should analyse DMO’s reasons and explanations for projects’ in-year budget variance.

Recommendation 2

The Committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office and Defence Materiel Organisation consult as necessary and amend Section 2.2 of the PDSSs, in time for submission of the draft 2014–15 MPR Guidelines to the JCPAA, to ensure that the following are reported:

- each Major Project’s 1 July budget estimates, as published in the Portfolio Budget Statements;

- mid-year estimates, as published in the Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements;

- if necessary, any more subsequent estimates since the mid-year estimates; and

- 30 June actual expenditure; along with

- explanations of variance between each of the above.

Recommendation 3

The Committee recommends that Defence and the Defence Materiel Organisation take the necessary actions to ensure there is improved line of sight between the Major Projects Report and the Portfolio Budget Statements and Portfolio Budget Estimates Statements. For example, by improving the consistency of project names and groupings between the documents.

Recommendation 4

The Committee recommends that the Defence Materiel Organisation prepares a suitable and separate methodology for reporting sustainment activity and expenditure, and that this methodology be reported to the Committee within six months of the tabling of this report.

Recommendation 5

That starting from the 2013–14 Major Projects Report, ANAO publish a similar version of Figure 8 (on page 64 of the 2012–13 MPR), relating to Major Project total slippage post Second Pass Approval and acquisition type by approval date.

Recommendation 6

That the Australian National Audit Office and Defence Materiel Organisation consult as necessary to ensure that statements or graphs relating to capability in the PDSSs, particularly Section 1.2 and 5.1, be appropriately qualified in the 2013–14 Major Projects Report, by noting that:

- The graphs in Section 5.1 do not necessarily represent capability achieved; and

- The capability assessments and forecasts in the PDSSs are not subject to ANAO’s assurance audit.

Recommendation 7

To improve the robustness of capability performance information, that the Australian National Audit Office and Defence Materiel Organisation consult as necessary and propose amendments to Section 5.1 and 1.2 in the 2014–15 MPR Guidelines, to:

- Apply a more objective method to assessing capability performance; and

- Distinguish capability achieved from capability yet to be achieved, capability unlikely to be achieved, and capability exceeded.

ANAO and DMO should provide a specific proposal to the Committee preferably by the end of August 2014 in line with submission of the 2014–15 MPR Guidelines.

Recommendation 8

That DMO maintain the ability to publish project maturity scores in future Major Projects Reports until these are no longer required by the guidelines endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.

Recommendation 9

That all future Major Projects Reports, including the 2013–14 Major Project Report, include information on recently exited Major Projects, at a level similar to Tables 2.1 to 2.3 on pages 114 to 116 of the 2012–13 Major Project Report.

Recommendation 10

The Australian National Audit Office and Defence Materiel Organisation consult as necessary to propose amendments to the 2014–15 MPR Guidelines to make provision for information on exited Major Projects.

21. The Committee’s recommendations contribute to the development of the MPR each year and the formal response by the Department of Defence to the above-mentioned recommendations was provided to the Committee in late November 2014, for its consideration. However, while at the time of preparing this report the Committee’s views on the Department’s response was not known, the ANAO and the DMO’s actioning of recommendations in the 2013–14 MPR is summarised below:

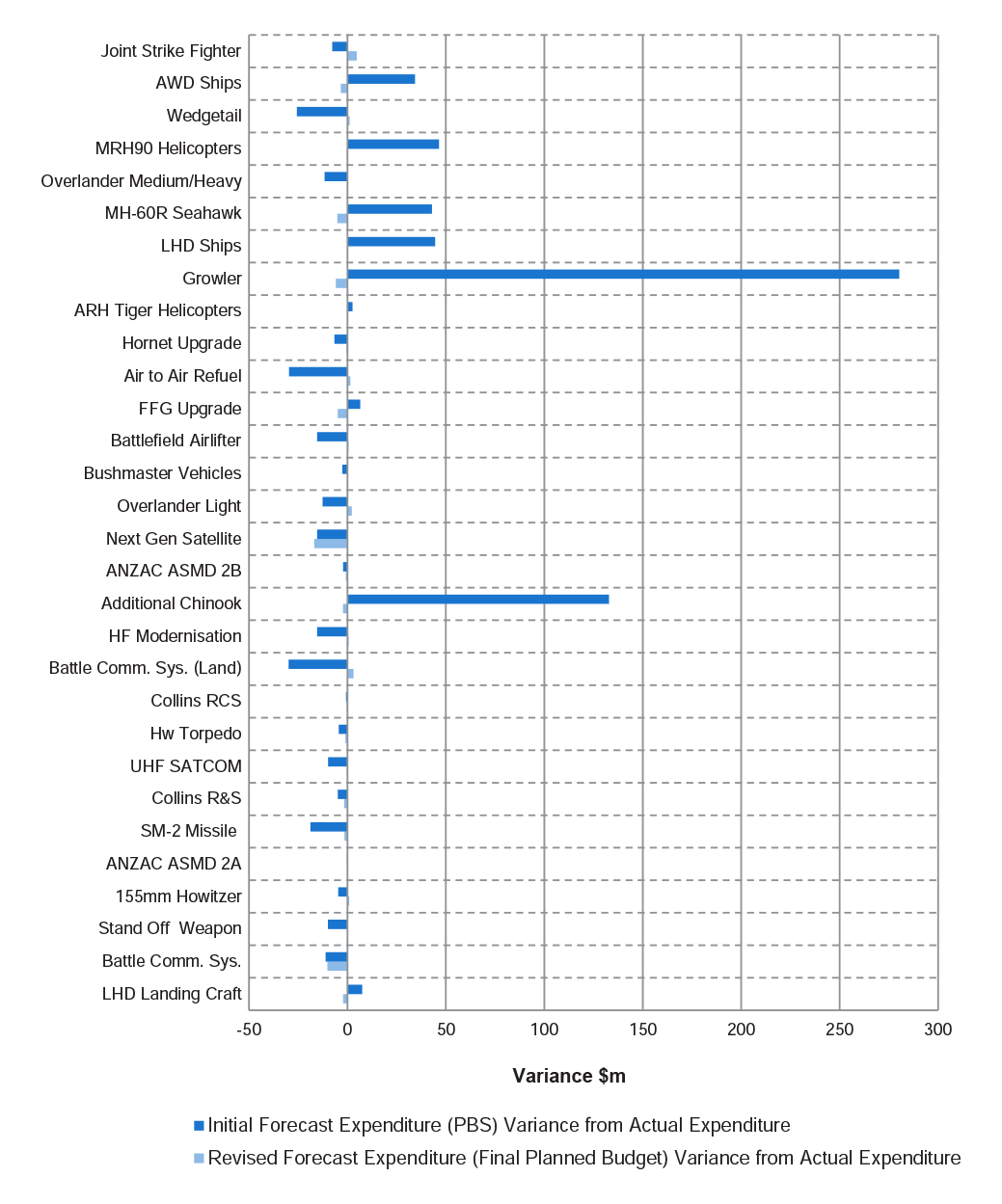

- Recommendation 1—Actioned: In-year budget to actual variance analysis is included in the 2013–14 MPR at paragraphs 2.29 to 2.31 in Part 1, and Table 2.2 and paragraph 2.10 in Part 2;

- Recommendation 2—Actioned: A revised Section 2.2 is included in the 2014–15 MPR Guidelines, which were endorsed in September 2014;

- Recommendation 3—Actioned: Improved consistency of project names is addressed at Table 1 in Part 1 and throughout the MPR;

- Recommendation 4—See further explanation at paragraphs 22 and 23, below;

- Recommendation 5—Actioned: A longitudinal representation of total slippage post Second Pass Approval and acquisition type by approval date is included at Figures 8 and 9 in Part 1;

- Recommendation 6—Actioned: Statements and graphs relating to capability are appropriately caveated in Sections 1.2 and 5.1 of each PDSS in Part 3;

- Recommendation 7—Actioned (partially): High level enhancements to the clarity of capability performance information is outlined at paragraph 2.65 in Part 1 and included in the 2014–15 MPR Guidelines;

- Recommendation 8—Actioned: Project maturity score analysis is included at paragraphs 2.12 to 2.14 in Part 1, and the PDSSs in Part 3;

- Recommendation 9—Actioned: The DMO has included information on recently exited Major Projects at Table 1.3 in Part 2; and

- Recommendation 10—Actioned: Information on exited Major Projects will be included within the MPR from 2014–15.

22. While Defence sustainment projects are generally outside of the scope of the MPR, the Collins R&S project (which is defined as a sustainment project by the DMO) has been included in the MPR at the request of the JCPAA since 2009–10. In addition, while ARH Tiger Helicopters and Collins RCS have been transferred to ‘sustainment’, they will be included within the 2014–15 MPR following the endorsement of the 2014–15 Guidelines.

23. In September 2014 the JCPAA also requested that the ANAO develop an options paper on sustainment reporting, and review other international works in this area. The ANAO will consult with the DMO in preparing a response to the JCPAA on this issue. The options developed will need to recognise that assessments in relation to readiness and availability of major Defence capabilities are classified.

24. Additionally, a performance audit to examine the contribution made by Materiel Sustainment Agreements to the effective sustainment of specialist military equipment, is expected to be tabled in 2015.

Overall outcomes

25. This seventh MPR continues the review of seven of the nine DMO Major Projects which were initially introduced in the 2007–08 MPR and has continued to introduce new projects up to the originally agreed maximum of 30 projects for review.14 The MPR maintains the transparency and accountability for performance relating to cost, schedule and progress towards delivering the key capabilities of Major Projects, and provides opportunities for further longitudinal and other analysis into the future.

The 2013–14 Major Projects review (Chapter 1)

26. Under section 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997, the ANAO has reviewed the PDSS data as contained in this volume as a priority assurance review and presents the Auditor-General’s Independent Review Report, at page 167.

27. As noted in paragraph 19, at page 11, the 2013–14 Guidelines required the introduction of a ‘contingency statement’ in Section 1.2 Current Status (Cost Performance) within each PDSS. Project offices are now required to indicate whether they have had contingency funds applied during the year, as well as disclosing which risks were mitigated by the application of those contingency funds. The six projects which applied contingency funds in 2013–14 were Joint Strike Fighter15, AWD Ships16, MRH90 Helicopters17, LHD Ships, FFG Upgrade and Additional Chinook.

28. Additionally, the ANAO continued to assess the progress of the DMO in addressing previously raised issues in relation to the administration of Major Projects. In 2013–14 issues were again noted within the following areas of project management, including:

- continued concerns of project offices in relation to price indexation and budget allocations, and inconsistency in the recording and application of contingency funds, (Section 1 of the PDSS);

- inconsistency in the application of the project maturity framework18, reducing its level of reliability of the maturity assessment, (Section 7 of the PDSS);

- inconsistency in the recording and reporting of major risks and issues by project offices, and in the terminology and reporting within the mandated Predict! and Excel risk management systems19, (Section 6 of the PDSS); and

- inconsistency in the application of the capability assessment framework20, (Section 5 of the PDSS).

29. The Auditor-General’s Independent Review Report takes into account the overall governance of Major Projects, the results of our examination of the DMO’s project management and reporting arrangements, and the results of our substantive procedures to gain assurance in relation to key information reported in PDSSs. In 2013–14, the results of the ANAO’s priority assurance review of the 30 PDSSs was that nothing has come to the attention of the ANAO that causes us to believe that the information and data in the PDSSs, within the scope of our review, has not been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with the Guidelines.

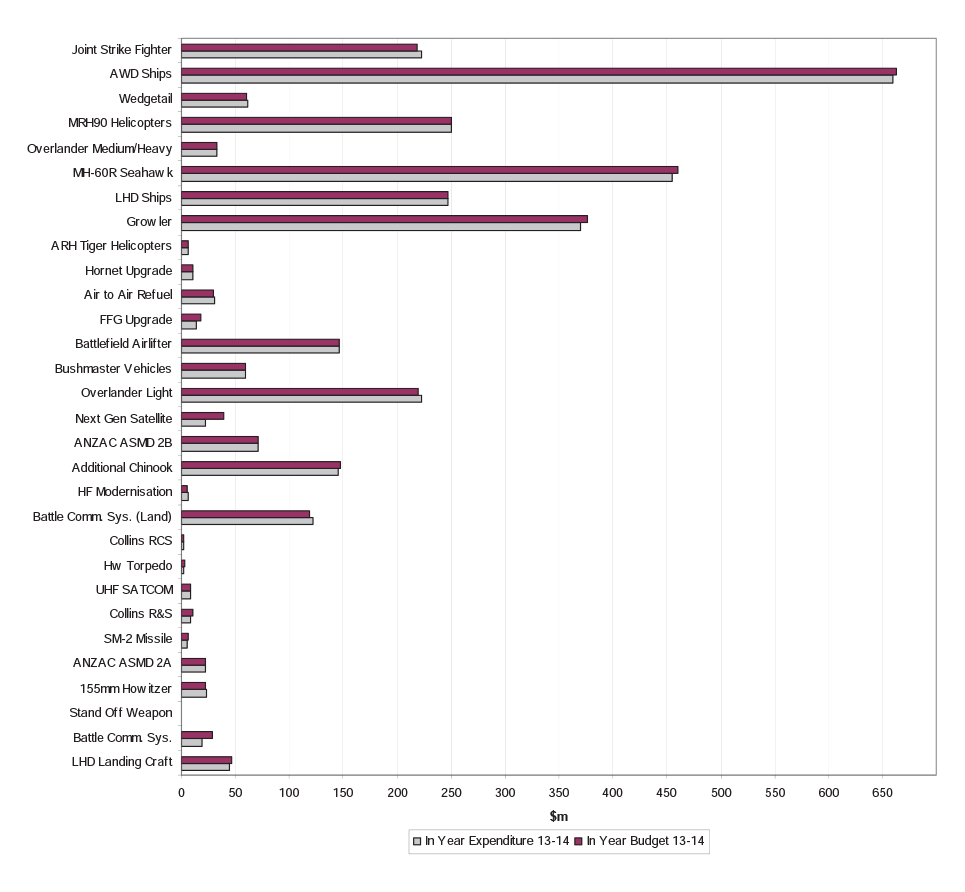

Analysis of projects’ performance (Chapter 2)

30. The data reviewed in the PDSSs covers the three major dimensions of project performance: cost, schedule, and progress towards delivering the planned capability.

31. Table 2, below, provides summary data on the DMO approved budget, schedule performance and progress toward delivering capabilities for the Major Projects covered in this report, and compares data against that reported in previous MPR editions.

Table 2: Summary longitudinal analysis

|

|

2011–12 MPR |

2012–13 MPR |

2013–14 MPR |

|

Number of Projects |

29 |

29 |

30 |

|

Total Approved Budget |

$47.3 billion |

$44.3 billion |

$59.4 billion |

|

Total Budget Variation since Second Pass Approval |

$5.9 billion |

$6.5 billion |

$16.8 billion |

|

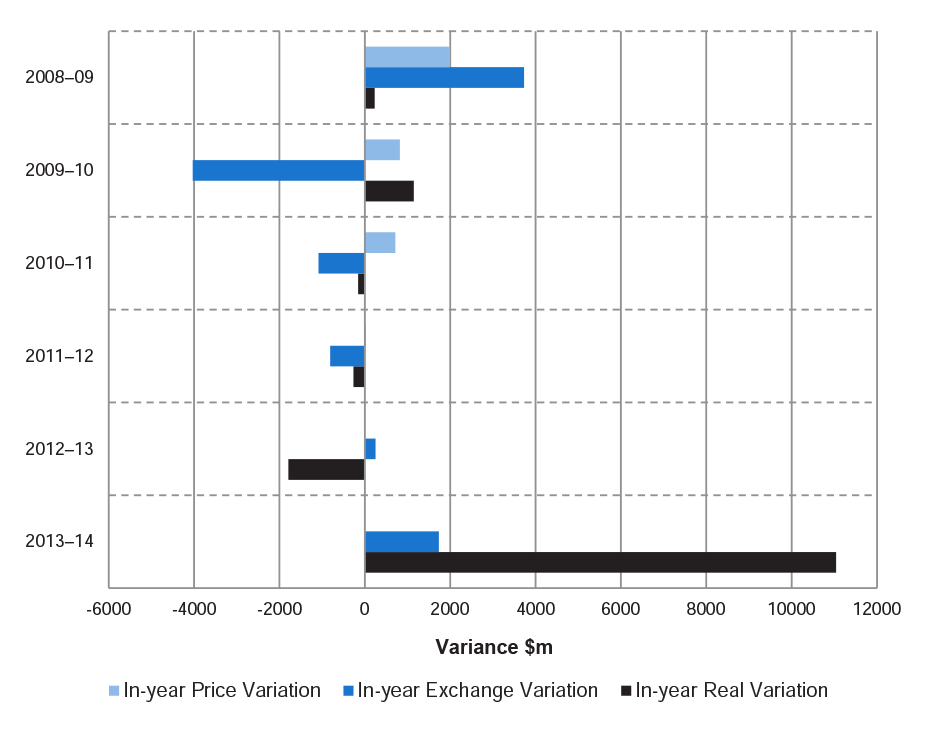

In-year Approved Budget Variation |

-$1.1 billion (-2.4 per cent) |

-$1.5 billion (-3.4 per cent) |

$12.8 billion (21.5 per cent) |

|

Total Schedule Slippage 1, 2 |

822 months (30 per cent) |

957 months (36 per cent) |

1 115 months (36 per cent) |

|

Average Schedule Slippage per Project |

30 months |

35 months |

38 months |

|

In-year Schedule Slippage 3 |

99 months (4 per cent) |

147 months (5 per cent) |

205 months (7 per cent) |

|

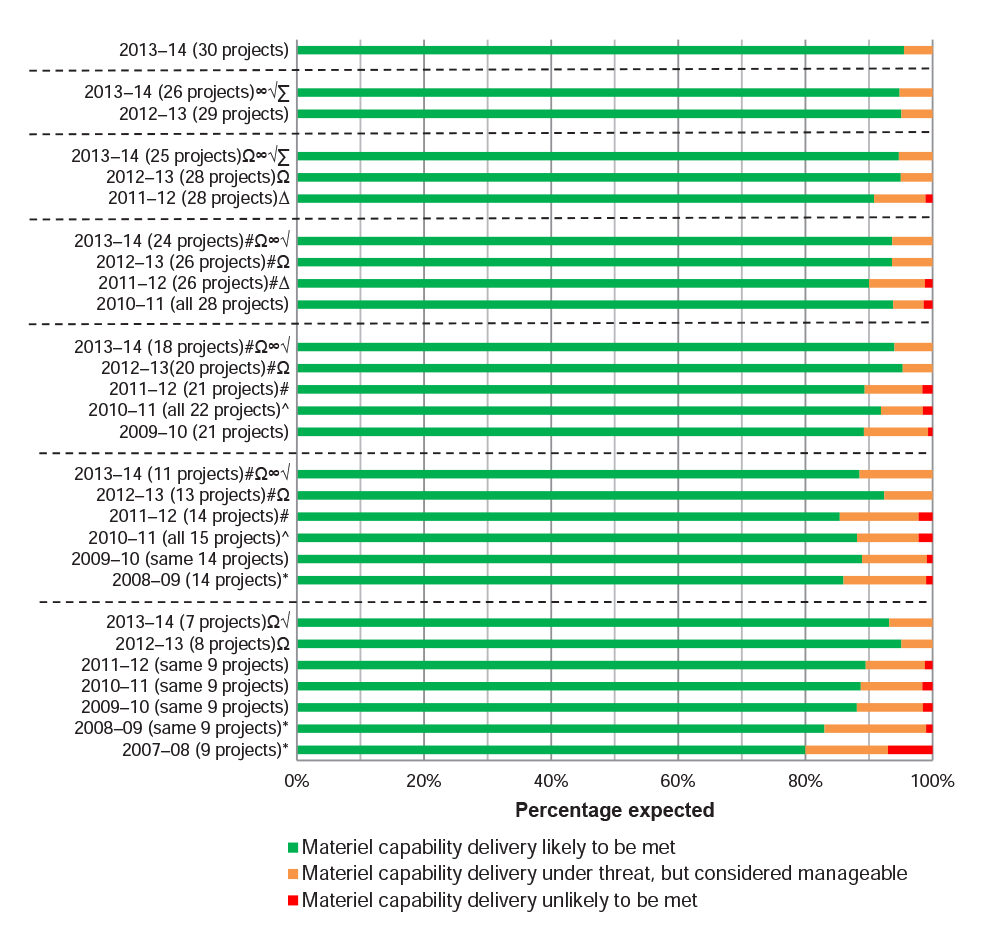

Expected Capability 4 |

|||

|

91 per cent |

95 per cent |

96 per cent |

|

8 per cent |

5 per cent |

4 per cent |

|

1 per cent |

0 per cent |

0 per cent |

Refer to paragraphs 31 to 45 in Part 1, at pages 17 to 22, of this report.

Note 1: The data for the 30 Major Projects in the 2013–14 MPR compares the data from projects in the 2012–13 MPR and 2011–12 MPR. A comparison of the data across years should be interpreted in this context, i.e. once a project is removed from the MPR, data is removed from the total slippage calculation for all years, but remains within in-year calculations where relevant.

Note 2: Slippage refers to the difference between the original government approved date and the current forecast date. These figures exclude schedule reductions over the life of the project.

Note 3: Based on the 27 projects from the 2010–11 MPR, 29 projects from the 2011–12 MPR and 26 projects from the 2012–13 MPR respectively.

Note 4: The grey section of the table is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s priority assurance review. See further explanation in paragraph 10, at page 8, of this report.

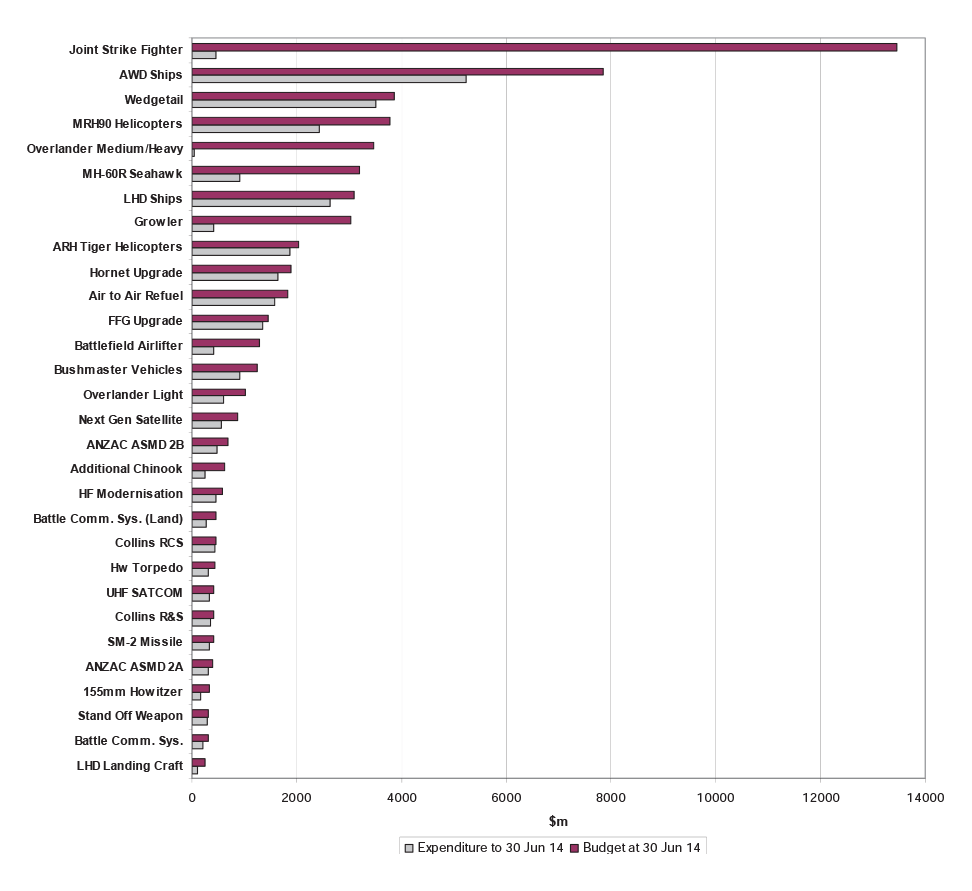

Cost

32. Within the review period, all projects continued to operate within the total approved budget of $59.4 billion.21

33. The total budget for Major Projects included in this MPR has increased by $16.8 billion (37.9 per cent) since Second Pass Approval. Refer to Table 3, below.

Table 3: Budget variation over $500 million post Second Pass Approval by Variation type

|

Project |

Variation |

Explanation |

Year |

Amount $b |

|

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

Scope increase |

58 additional aircraft |

2013–14 |

10.5 |

|

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

Scope increase/budget transfers |

34 additional aircraft |

2005–06 |

2.4 |

|

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

Scope increase/budget transfers |

General program supplementation |

2013–14 |

0.7 |

|

|

Bushmaster Vehicles |

Scope increase |

715 additional vehicles |

Various |

0.8 |

|

|

Other |

Scope increase/budget transfers (net) |

Other scope changes and transfers |

Various |

(2.3) |

|

|

|

Sub-total |

|

12.1 |

||

|

Price Indexation – materials and labour (net) |

|

6.1 |

|||

|

Exchange Variation – foreign exchange (net) |

|

(1.4) |

|||

|

|

Total |

|

|

16.8 |

|

Source: The ANAO’s analysis of the 2013–14 PDSSs. Refer to paragraph 33, above.

Note: For the breakdown of in-year variation, refer to Table 7, at page 54, of this report.

34. Overlander Vehicles, provided with Second Pass Approval in August 2007, was separated into two phases, Phase 3A Lightweight and Light Capability and Phase 3B Medium and Heavy Capability, in December 2011. Phase 3A was reapproved for Second Pass at that time; however Phase 3B did not receive Second Pass Approval until July 2013 and was reflected as a scope decrease of $2.2 billion in the 2012–13 MPR. This timing difference has now been readjusted in this report.

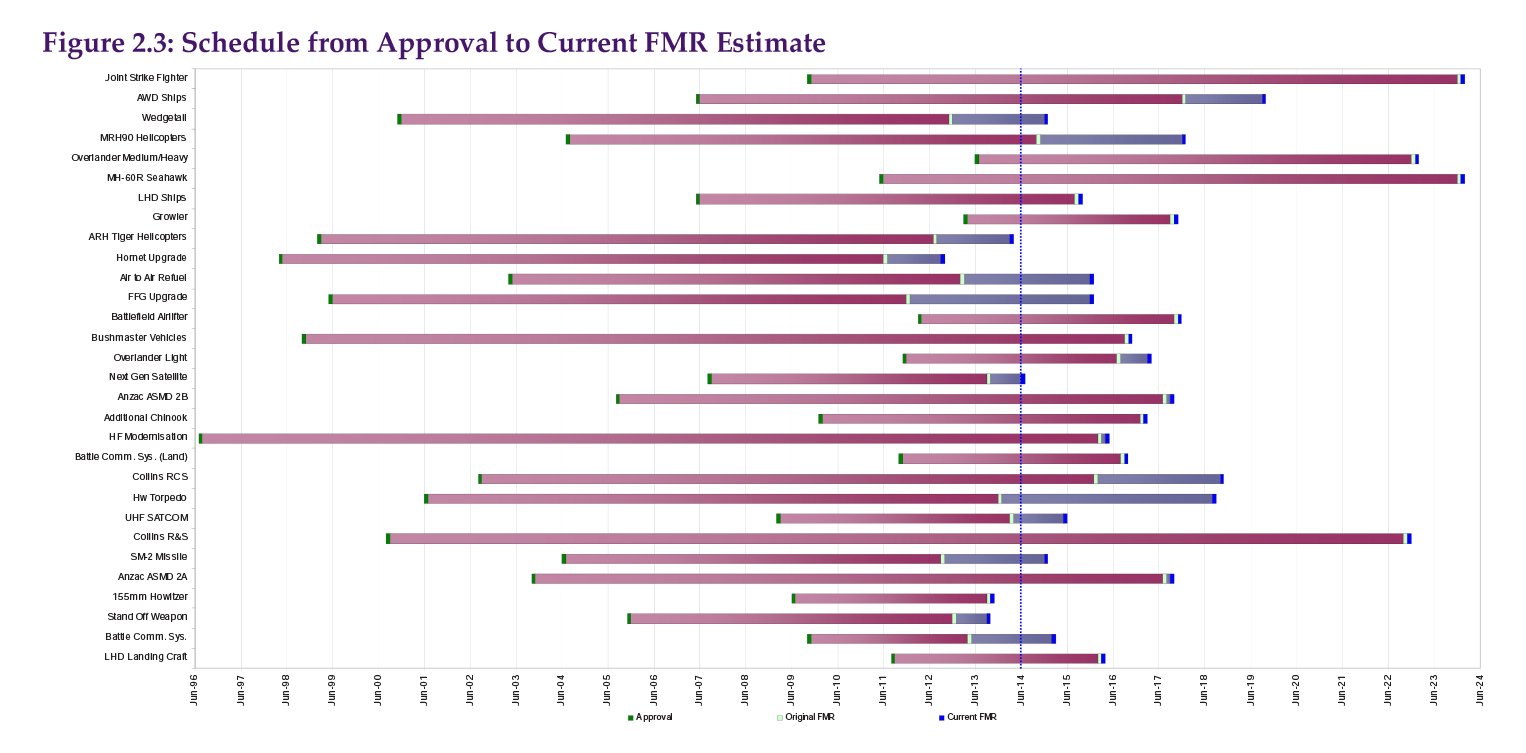

Schedule

35. Maintaining Major Projects on schedule remains an ongoing challenge for the DMO22; in turn affecting when the capability is made available for operational release and deployment by the ADF.

36. In the 2013–14 MPR, the total schedule slippage for the 30 Major Projects as at 30 June 2014 is 1 115 months (2012–13: 957 months) when compared to the initial schedule first approved by government. This represents a 36 per cent (2012–13: 36 per cent) increase on the originally approved schedule. Refer to Table 4, below.

Table 4: Schedule slippage from original planned FOC

|

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

0 |

0 |

Next Gen Satellite |

0 |

0 |

|

AWD Ships |

0 |

22 |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

0 |

57 |

|

Wedgetail |

0 |

78 |

Additional Chinook |

0 |

0 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

60 |

60 |

HF Modernisation |

0 |

147 |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

0 |

0 |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) |

0 |

4 |

|

MH-60R Seahawk |

0 |

0 |

Collins RCS |

1 |

109 |

|

LHD Ships |

0 |

0 |

Hw Torpedo |

58 |

58 |

|

Growler |

0 |

0 |

UHF SATCOM |

0 |

0 |

|

ARH Tiger Helicopters |

0 |

79 |

Collins R&S |

0 |

99 |

|

Hornet Upgrade |

16 |

39 |

SM-2 Missile |

11 |

26 |

|

Air to Air Refuel |

12 |

57 |

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

0 |

72 |

|

FFG Upgrade |

12 |

132 |

155mm Howitzer |

7 |

7 |

|

Battlefield Airlifter |

0 |

0 |

Stand Off Weapon |

4 |

37 |

|

Bushmaster Vehicles |

0 |

0 |

Battle Comm. Sys. |

15 |

23 |

|

Overlander Light |

9 |

9 |

LHD Landing Craft |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

|

|

|

205 |

1 115 |

Source: The ANAO’s analysis of the 2013–14 PDSSs. Refer to paragraph 36, above.

37. While it should be noted that platform availability contributes to the slippage within the ‘Collins’ projects, the other most significant slippage delays relate to those projects with the most developmental content.

38. Disaggregation according to a project’s Second Pass Approval shows that 80 per cent (2012–13: 87 per cent) of the total schedule slippage across the Major Projects covered in the 2013–14 MPR is made up of projects approved prior to the DMO’s demerger from the Department of Defence, in July 2005. This is a positive indicator of the benefits that the DMO, as a specialist acquisition and sustainment organisation, is able to bring to complex Defence procurement. It also demonstrates the impact on schedule performance during the transition to higher levels of Military-Off-The-Shelf (MOTS) acquisitions following the Defence Procurement Review 2003 (Kinnaird Review).23

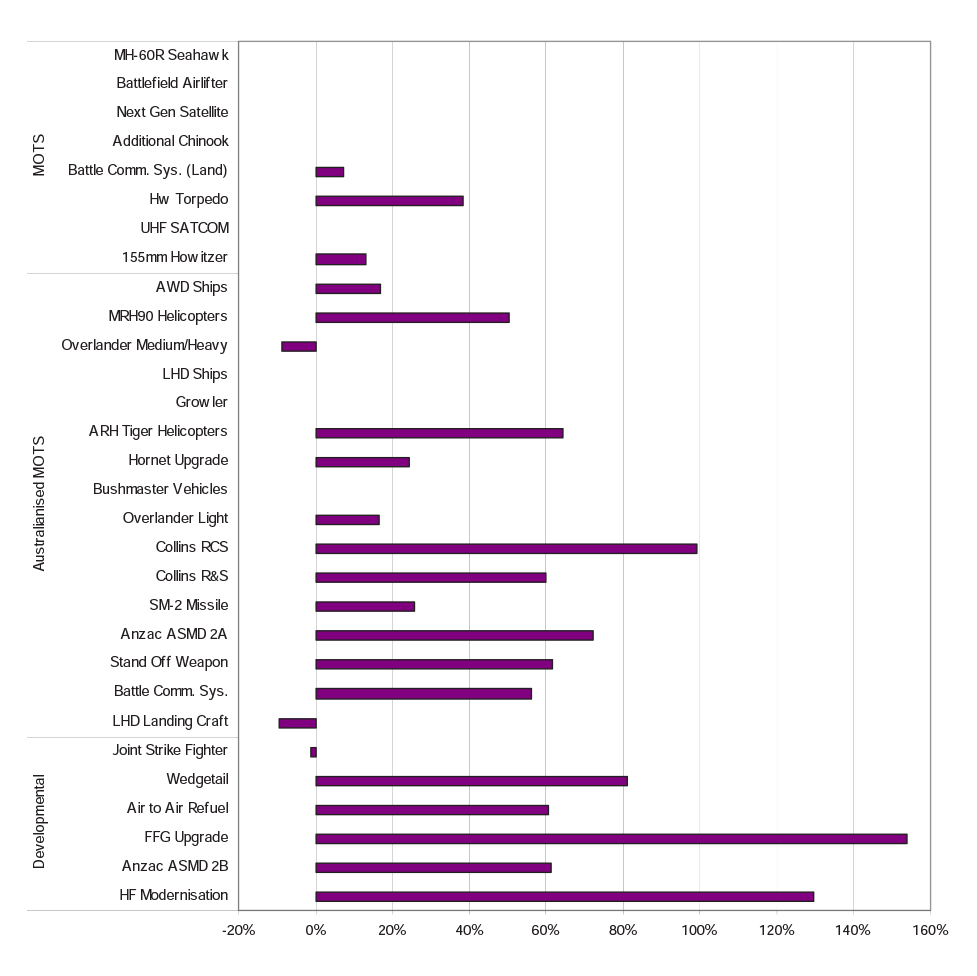

39. Additional ANAO analysis (refer to Figure 8, at page 62) presents project slippage as reported in each of the seven MPRs against the DMO classification of projects as MOTS, Australianised MOTS or developmental.24 These classifications are a general indicator of the difficulty associated with the procurement process. This figure highlights, prima facie, that the more developmental in nature a project is, the more likely it will result in project slippage, as well as demonstrating the advantages of selecting MOTS acquisitions.25 For the first time, Figure 9 (at page 63) begins the analysis of completed projects which have been removed from the MPR.

40. The reasons for schedule slippage vary but primarily reflect the underestimation of both the scope and complexity of work, particularly for Australianised MOTS and developmental projects (see paragraphs 2.29 to 2.31 in Part 2).

Capability

41. The third major aspect of project performance examined by this report is progress towards the delivery of capability required by government and specified by the ADF. Assessment of expected capability delivery by the DMO is outside the scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, but is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of the three major components of project performance.

42. The DMO expects that the 30 projects in this year’s MPR will deliver all of their key capability requirements, recognising that some elements of the capability required may be under threat, but considered manageable (assessed as either green or amber). This is consistent with the 2012–13 assessment, and represents five project offices currently having challenges (2012–13: six).

43. This year, as reported by the DMO, the delivery of four per cent (2012–13: five per cent) of the key capabilities is considered to be under threat but is considered manageable. The projects considered to have some elements under threat, but considered manageable are: Joint Strike Fighter, Wedgetail, MRH90 Helicopters, Air to Air Refuel and FFG Upgrade. Further details are outlined at paragraph 2.77, at page 78. Refer also to Table 5, below.

Table 5: Longitudinal Expected Capability Delivery

|

Expected Capability |

2011–12 MPR |

% |

2012–13 MPR |

% |

2013–14 MPR |

% |

|

High Confidence (Green) |

|

91 |

|

95 |

|

96 |

|

Under Threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

|

8 |

|

5 |

|

4 |

|

Unlikely (Red) |

|

1 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

Total |

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

100 |

Source: The ANAO’s analysis of the PDSSs in published MPRs.

Note 1: All projects had some component/s with high confidence of delivery.

Note 2: Removal of the moving target capability from the project scope in 2010–11, combined with resolution of fuze production issues and successful completion of Operational Test and Evaluation in 2012–13, has led to this project achieving its remaining scope.

Note 3: The Course Correcting Fuze has been cleared for production in the United States and is no longer considered ‘under threat’ of delivery.

44. As shown in Table 5, above, the majority of projects for which the DMO’s expected capability delivery is below 100 per cent, are developmental or Australianised MOTS (AMOTS). The only exception is 155mm Howitzer, which was awaiting clearance of the Course Correcting Fuze for production, which has since occurred.26

45. In addition, the DMO has continued the practice of including declassified information on settlement actions for projects in the interests of providing greater transparency to readers of this report. In 2013–14, a renegotiation with Airbus Defence and Space regarding delivery of Air to Air Refuel contracted requirements resulted in the signing of a Deed of Settlement.27 Prior settlements for projects within this report include Wedgetail28, MRH90 Helicopters29 and ARH Tiger Helicopters.30

Developments in acquisition governance (Chapter 3)

46. Consistent with previous years, developments in acquisition governance processes are covered in the ANAO’s review, with general indications of positive impacts from some of the more recent initiatives. As might be anticipated, while some initiatives continue to mature, others require further progress prior to achieving their intended impact. These developments broadly relate to the following key acquisition governance areas.

Gate Review Boards

47. First introduced in 2008, the Gate Review process31 was designed to provide the CEO DMO with assurance that all identified risks for a project are manageable, and that costs and schedule are likely to be under control prior to a project passing various stages of its life cycle. However, while the Gate Review process is continuing to evolve, the DMO intend to review their application within acquisition and expand into sustainment in future years.

Projects of Concern

48. First established in 2008, the Projects of Concern process was implemented to address project issues of concern to the DMO and government, relating to cost, schedule and capability. The process has continued to play an important, although limited role, across the portfolio of MPR projects. The Projects of Concern within the MPR at 30 June 2014 are AWD Ships, MRH90 Helicopters and Air to Air Refuel.

Early Indicators and Warnings

49. In May 2011, the then Government announced the impending implementation of the Early Indicators and Warnings (EI&W) system to identify problems with projects in the formative stages of the life cycle. However, following the June 2013 review by the Defence Capability and Investment Committee, the CEO DMO proposed a new reporting system in December 2013, the Quarterly Project Performance Report, which is expected to replace EI&W. Further analysis of this new system will be undertaken in future MPRs.

Joint Project Directives

50. The introduction of a requirement for Joint Project Directives (JPDs)32 in 2009–10, for all projects approved by government from March 2010 is maturing and expected to have a greater influence over the portfolio of MPR projects in future years. To date only eight MPR projects have completed a JPD.33 It is expected that JPDs will provide a sound basis for ensuring government requirements are delivered and further review of the JPD process will be undertaken in future MPRs.

Business systems rationalisation

51. The DMO’s business systems34 rationalisation is aimed at consolidating processes and systems in order to provide a more manageable system environment. Although progress to date has been limited, the DMO advises it has taken some steps in this area through the development of an Integrated Project Management System which is expected to improve reporting practices across the DMO and will be tested on selected project offices in 2014–15.

Project management and skills development

52. Project management and skills development within the DMO and the Defence Industry is a key challenge for the Government and industry alike. Over the last decade, more than $300 million has been provided by government alone to assist with professionalising DMO staff and up-skilling participants within the Defence Industry. While DMO activities have increased professional competencies held by the DMO staff, the measurement of the impact within industry has been limited. The ANAO will continue to review project management and skills development programs in the 2014–15 MPR.

53. Consistent with previous years, the ANAO’s detailed assessment of these governance initiatives is contained in Chapter 3 of Part 1.

1. The 2013–14 Major Projects Review

Introduction

1.1 This chapter provides an overview of the 2013–14 review scope and approach adopted by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) in consideration of the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) and the subsequent results of the review.

1.2 Previous reviews have highlighted issues which impact on the Defence Materiel Organisation’s (DMO’s) administration of major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects), and their related frameworks. These issues were reconsidered, where appropriate, in order to assess the DMO’s progress in addressing them during 2013–14. Key frameworks considered further in this chapter include:

- the financial framework as it applies to the management of project budgets and expenditure, in an out-turned budget environment;

- the project maturity framework and systems in place to support the provision of maturity data in the PDSS;

- the enterprise risk management framework as it applies to major risk and issue data and its maturity; and

- the capability assessment framework, as it relates to the DMO’s evaluation of the probability of delivering required capabilities.

1.3 This chapter also makes reference to areas of focus raised by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) for consideration in the development of this and future Major Projects Reports (MPRs). As noted in paragraph 20, at page 11, the JCPAA examined the 2012–13 MPR in March 2014, publishing Report 442, Review of the 2012–13 Defence Materiel Organisation Major Projects Report in May.

1.4 Chapter 2 of Part 1 provides consideration of the DMO’s project performance, based on the information provided in the PDSSs.

1.5 Chapter 3 of Part 1 includes developments in the DMO’s acquisition governance arrangements, which were also taken into consideration during the review process.

Review scope and approach

1.6 In 2012 the JCPAA identified the review of the DMO’s PDSSs as a priority assurance review, is that it provides the ANAO full access to the information gathering powers under the Auditor-General Act 1997.

1.7 The ANAO’s review of the individual project PDSSs, which are contained in Part 3, were conducted in accordance with the Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements (ASAE) 3000 Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

1.8 Excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review is PDSS data on projects’ budget adequacy, the identification of Risks and Issues, the Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance, and ‘forecasts’ of future dates and the achievement of future outcomes. By its nature, this information relates to future events and depends on circumstances that have not yet occurred or may not occur, or may be impacted by events that have occurred but have not yet been identified. Accordingly, the conclusion of this review does not provide any assurance in relation to this information.

1.9 While our work is appropriate for the purpose of providing an Independent Review Report in accordance with ASAE 3000, our review of individual PDSSs is not as extensive as individual audits conducted by the ANAO, in terms of the nature and scope of issues covered, and the extent to which evidence is required by the ANAO. Consequently, the level of assurance provided by this review in relation to the 30 Major Projects is less than that provided by our program of audits.

1.10 However, the MPR is well positioned to examine systemic issues and provide longitudinal analysis for the 30 projects reviewed, and may also reflect on, or have implications for, general project management practices in the DMO, or more broadly within other areas of the Australian Defence organisation.

Areas of review focus

1.11 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the individual PDSSs included:

- examination of each PDSS and the documents and information relevant to them;

- a review of relevant processes and procedures used by the DMO in the preparation of the PDSSs;

- an assessment of the systems and controls that support project financial management, risk management, and project status reporting, within the Australian Defence organisation;

- interviews with persons responsible for the preparation of the PDSSs and those responsible for the management of the 30 projects;

- taking account of industry contractor comments provided to the ANAO and the DMO on draft PDSS information;

- assessing the assurance by the DMO managers attesting to the accuracy and completeness of the PDSSs;

- examination of the representations by the Chief Finance Officer (CFO) DMO supporting the project financial assurance and contingency statements, and the independent third-party review of the project financial assurance statements;

- examination of confirmations, provided by the Secretary of the Department of Defence and Chief of the Defence Force, from the Capability Managers, relating to each project’s progress toward Initial Materiel Release (IMR) and Final Materiel Release (FMR), and Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC); and

- examination of the ‘Statement by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) DMO’, including significant events occurring post 30 June, and management representations by the CEO DMO.

1.12 The ANAO’s processes and procedures to provide independent assurance over the PDSSs also focused on reviewing the DMO’s project management and reporting arrangements, and the number and nature of processes in place that contribute to the overall governance of Major Projects within the DMO and the broader Australian Defence organisation. These included:

- the financial framework, particularly as it applies to the project financial assurance and contingency statements and managing project budgets in an out-turned budget environment, (Section 2 of the PDSSs);

- schedule management and test and evaluation processes, (Section 3 of the PDSSs);

- the capability assessment framework, as it relates to the DMO’s evaluation of the likelihood of delivering key capabilities, (Section 5 of the PDSSs);

- ongoing review of the implementation of the enterprise risk management framework and major risk and issue data, (Section 6 of the PDSSs);

- the project maturity framework and reporting and the systems in place to support the provision of this data, (Section 7 of the PDSSs); and

- developments in the areas of acquisition governance including Gate Review Boards, Projects of Concern, Early Indicators and Warnings, Joint Project Directives, business systems rationalisation, and project management and skills development within the Commonwealth and industry, (Chapter 3 in Part 1).

1.13 This review informed the ANAO’s understanding of the systems and processes supporting the PDSSs for the 2013–14 review period, and highlighted issues in those systems and processes that could be beneficially addressed by the DMO in the longer term.

Results of the review

1.14 The following sections outline the results of the ANAO’s review, and which contribute to the overall conclusion in the Auditor-General’s Independent Review Report for 2013–14.

Financial framework

1.15 In 2012–13, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework as it applied to managing project budgets, in an out-turned budget environment, and the project financial assurance statements. The review indicated that all project offices expected to deliver all required capabilities within the allocated budget.

1.16 However, a number of project offices added additional disclosures to their PDSSs, and in particular, AWD Ships, LHD Ships and ANZAC ASMD Phase 2B recognised that available funding for price indexation was a key concern. Prior to 1 July 2010 projects were periodically supplemented for price indexation, whereas the allocation for price indexation is now provided for on an out-turned basis at Second Pass Approval.35 This change in supplementation policy has meant that price indexation has emerged as a risk for some projects, which would generally emerge later in a project’s life cycle.

1.17 As discussed in the 2012–13 MPR, the emergence of indexation risk has, to some extent, changed the nature and use of the contingency budget from dealing only with project risk management to including broader price management. This requires project office finance staff to have a greater understanding of the factors that influence indices and their likely movement over the life of the project.

1.18 A project’s total approved budget comprises:

- the programmed budget, which covers the project’s approved activities; and

- the contingency budget, which is established to provide adequate budget to cover the inherent cost, schedule and technical risks.36

1.19 The DMO’s management of this financial risk is based on a portfolio management approach within the responsibilities of the CFO (refer to paragraph 1.12 in Part 2 of the 2011–12 MPR, where this is explained further).

1.20 In conjunction with the financial assurance statement, introduced in the 2011–12 MPR, the contingency statements were introduced for the first time in this, the 2013–14 MPR. Together, they provide greater transparency of projects’ financial status, following the move to out-turned budgeting in 2010, and highlight the use of contingency funding to mitigate projects risks.

1.21 In 2013–14, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework as it applies to managing project budgets, including contingency, in an out-turned budget environment, and the project financial assurance and contingency statements.

Project financial assurance statement

1.22 The project financial assurance statement was added to the PDSSs in the 2011–12 MPR, to provide readers with a clear articulation of a project’s financial position and to provide transparency in regard to whether there is ‘sufficient remaining budget for the project to be completed.’37

1.23 The 2012–13 project financial assurance statements indicated that all project offices expected to complete within budget. However, AWD Ships, LHD Ships and ANZAC ASMD Phase 2B recognised that available funding for price indexation was a key concern. In the case of AWD Ships, the 2012–13 Statement by the CEO DMO also noted emerging concerns around cost overruns and associated delays in shipbuilding aspects of the AWD Program.38

1.24 In 2013–14, while all projects again continued to operate within their total approved budget, the AWD Ships39, LHD Ships and ANZAC ASMD 2B project offices continued to recognise that available funding may be insufficient as contracted indices escalation may be greater than the approved project budget. In relation to the AWD Ships project, the 2013–14 Statement by the CEO DMO, continues to note concerns in relation to the adequacy of the total project budget, which will be dependent on the results of the AWD Reform Program.40

1.25 In addition, during 2013–14, the DMO continued to support the project financial assurance statements with an independent third-party review, considering factors including: remaining budget, Projects of Concern listing, complexity, diversity across divisions and past history.

1.26 Projects selected for third-party review in support of the financial assurance statement assurance process included:

- detailed review—Overlander Medium/Heavy, MH-60R Seahawk, Growler and Additional Chinook; and

- standard review—Joint Strike Fighter, AWD Ships, MRH90 Helicopters, LHD Ships, Battlefield Airlifter and Next Gen Satellite.

1.27 Observations from the review included that both the AWD Ships and LHD Ships projects have significant contractual exposure to indexation factors and that both project offices have recognised and costed a risk in relation to this matter.

1.28 In conclusion, while for the 2013–14 MPR, the CFO’s representation letter to the CEO DMO on the project financial assurance statements was unqualified, the project financial assurance statement is restricted to the current financial contractual obligations of the DMO for these projects including the result of settlement actions and the receipt of any liquidated damages; and current known risks and estimated future expenditure as at 30 June 2014.

1.29 In contrast, for each of the projects discussed in paragraph 1.24, above, the project offices are acknowledging their continuing concerns in relation to price indexation and allocations provided at Second Pass Approval. The ANAO will continue to assess the outcomes of the financial assurance statements in future MPRs.

Contingency statements

1.30 As noted above, the 2013–14 Guidelines introduced the requirement for a ‘contingency statement’ within each PDSS. PDSSs are now required to include a statement as to whether contingency funds have been applied during the year, as well as disclosing the risks mitigated by the application of those contingency funds. The six projects which had contingency funds applied in 2013–14 were Joint Strike Fighter (increased costs of Stage 1 aircraft), AWD Ships (budget and skill/knowledge risks), MRH90 Helicopters (technical and integration risks), LHD Ships (IT standard operating environment risks), FFG Upgrade (workforce resource risks) and Additional Chinook (workforce and facilities risks).

1.31 The examination of the contingency statements also highlighted that:

- where projects had contingency funds applied, the purpose was within the approved scope of the project;

- the clarity of the relationship between contingency application and identified risks varied. Of the 29 projects that have a formal contingency allocation41, 19 did not explicitly align their contingency log, with their risk log; and

- the method for applying contingency varied, with only seven project offices using the ‘expected costs’ of the risk treatment (as required by the DMO Project Risk Management Manual (PRMM) version 2.4) and the remaining 22 using either a proportionate allocation of the likelihood of the risk eventuating (the method outlined in PRMM version 2.3), or having no application of contingency against risk.42

1.32 Finally, although the ANAO found that all projects offices tracked their contingency budget in some form, the methods of recording the balance of contingency budgets and application of contingency funds differed between projects. For example, project offices varied in whether they maintained a record of reviews of their contingency log, and its adequacy, or included risk identifiers and descriptors for allocations of their contingency budget. All of which are requirements outlined in the PRMM version 2.4.

Project maturity framework

1.33 Project maturity assessments have been a feature within the MPR since its inception in 2007–08. At that time the DMO reflected that they were introduced within the DMO as Project Risks Scores in 2004, and later renamed Project Maturity Scores in 2005.

1.34 The DMO Project Management Manual 2012, defines a maturity score as:

The quantification, in a simple and communicable manner, of the relative maturity of capital investment projects as they progress through the capability development and acquisition life cycle.43

1.35 While the DMO has raised some doubts about the effectiveness of the current framework, the DMO has agreed to retain maturity scores following the recent JCPAA recommendation.44 The Committee viewed the retention of maturity scores as important in relation to providing a measure of capability delivered for each project, until a measure equal to or better than current arrangements is available.

1.36 While the ANAO has previously raised inconsistency in the application of project maturity scores as an issue, during 2013–14, the ANAO noted that project offices were more consistently assigning maturity scores than in previous years. However, while some subjectivity necessarily remains, in the context of a framework that relies upon the application of professional judgement across a diverse range of projects (from Military-Off-The-Shelf (MOTS) to developmental), project life cycles and project managers, with the detailed guidance available to project offices, it is a repeatable process for external review or audit.

1.37 The ANAO has also previously noted that while the 2012 Defence Capability Plan (DCP) recognises different benchmarks for Off-The-Shelf and developmental projects at First Pass and Second Pass Approval, the DMO’s project maturity framework does not.45 The benchmark for all seven attributes is the same for all projects regardless of acquisition type.

1.38 The DMO’s current guidance46 provides a breakdown of the project life cycle gates, what they represent, and the applicable benchmark maturity score.

1.39 Maturity scores are a composite indicator, constructed through the assessment and summation of seven different attributes which cumulatively form a project ‘maturity score’. The attributes are: Schedule, Cost, Requirement, Technical Understanding, Technical Difficulty, Commercial, and Operations and Support, which are assessed on a scale of one to ten.

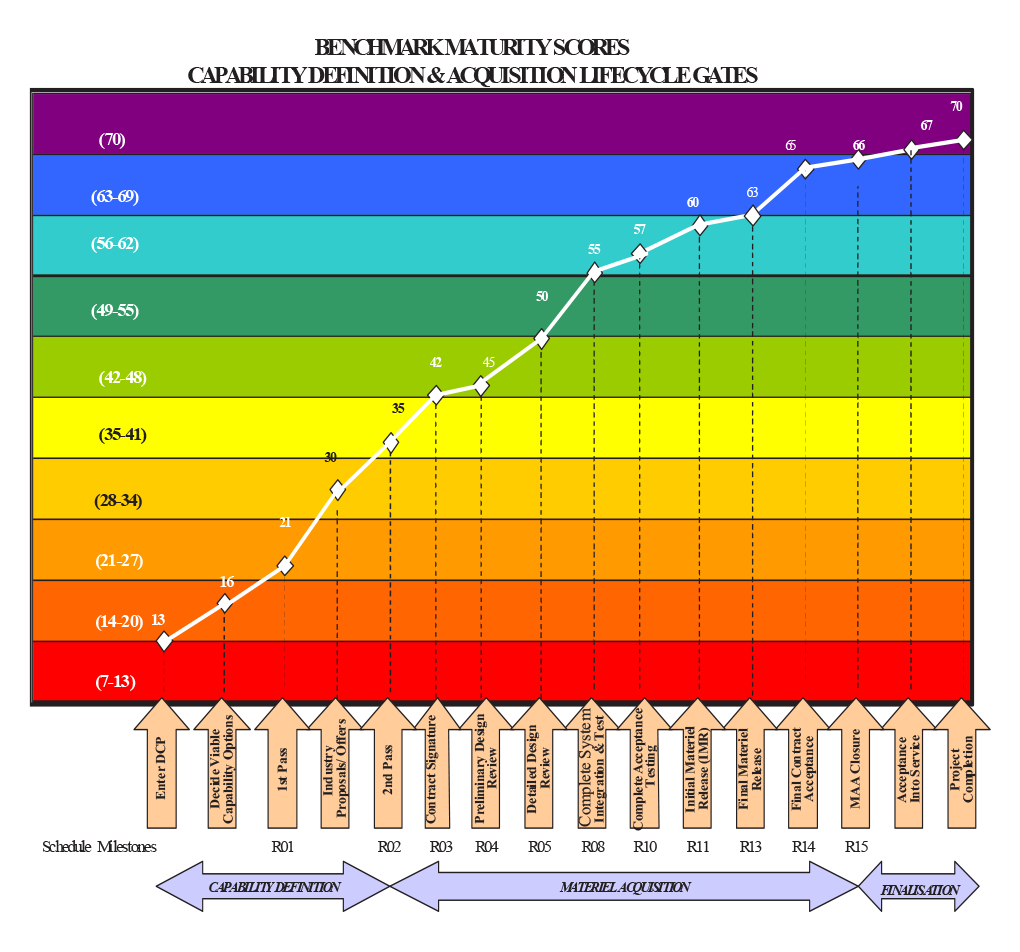

1.40 Comparing the maturity score against its expected life cycle gate benchmark provides internal and external stakeholders with an indication of a project’s progress. This may trigger further management attention or provide confidence that progress, against a predetermined benchmark, is satisfactory. Refer to Table 6, below.

Table 6: Capability Definition and Acquisition Life Cycle Gates

|

Project Life Cycle Gates |

Represents |

Benchmark Maturity Score |

DMO Schedule Milestone |

|

Enter Defence Capability Plan |

The stage at which a project is recommended to Government for inclusion in the Defence Capability Plan |

13 |

|

|

Decide Viable Capability Options |

The stage in the capability definition/ development process when 1st Pass options that will be put to Government are decided by CCDG |

16 |

|

|

1st Pass Approval |

The stage at which 1st Pass options to be put to Cabinet are endorsed by the DCC |

21 |

R01 |

|

Industry Proposals/ Offers |

The stage at which formal responses from industry to an RFP or RFT have been received and evaluated |

30 |

|

|

2nd Pass Approval |

The stage in the capability definition/ development process when 2nd Pass Approval is sought from Cabinet |

35 |

R02 |

|

Contract Signature |

On completion of contract negotiations and on concluding contract signature of a contract that has maximum influence on the project. |

42 |

R03 |

|

Preliminary Design Review(s) |

On completion of System Requirements Reviews and when Preliminary Design Reviews are completed |

45 |

R04 |

|

Detailed Design Review(s) |

On completion of Detailed Design Reviews |

50 |

R05 |

|

Complete System Integration and Test |

On completion of Verification and Validation activities at the system and subsystem levels |

55 |

R08 |

|

Complete Acceptance Testing |

On completion of all contractual acceptance testing and associated testing activities nominated in the TEMP |

57 |

R10 |

|

Initial Materiel Release (IMR) |

Occurs when the materiel components that represents the DMO contribution to Initial Operational Release (IOR) are ready for transition to the Capability Manager |

60 |

R11 |

|

Final Materiel Release (FMR) |

Occurs when all the products and services within the MAA have been transitioned to the Capability Manager. |

63 |

R13 |

|

Final Contract Acceptance |

On Final Acceptance as defined in the contract |

65 |

R14 |

|

MAA Closure |

Occurs when all of the actions necessary to finalise the MAA have been completed, including completion of all financial transactions and records, completion of contracts and transfer of remaining fund. |

66 |

R15 |

|

Acceptance Into Service |

The point at which the Capability Manager accepts the Materiel System, supplies and services for employment in operational service1 |

67 |

|

|

Project Completion |

Project closure is achieved when the project is financially closed, support arrangements have been transitioned and all MAA requirements have been demonstrated and transitioned. |

70 |

|

Source: DMSP (PROJ) 11-0-007, Project Maturity Scores at Life Cycle Gates, September 2010.

Note: Shaded rows are CDG Responsibility; Unshaded rows are DMO Responsibility.

Note: Where multiple elements of a mission system are involved (e.g. 3 surface combatants) this date represents Initial Operational Capability (IOC) of the initial Subset, including its associated operational support, that is, when the Initial Operational Capability is achieved. (DI(G) OPS 45-2 refers).

1.41 The guidance underpinning the attribution of maturity scores would benefit from a review for internal consistency and relationship to the Australian Defence organisation’s contemporary business. For example, allocating approximately 50 per cent of the maturity score at Second Pass Approval, despite acquisition type, is often inconsistent with the proportion of project funds expended, and the remaining work required in order to deliver the project.

1.42 Further, the existing project maturity score model does not always effectively reflect a project’s progress during the often protracted build phase, particularly for developmental projects. During this phase it can be expected that maximum expenditure will occur, and risks realised, some of which will only emerge as test and evaluation activities are pursued through to acceptance into operational service.

1.43 Finally, while the DMO guidance underpinning maturity scores was due for review in September 201247, this review has not yet been finalised. The ANAO will continue to review the framework and attribution of maturity scores in subsequent MPRs.

Enterprise risk management framework

1.44 In the 2012–13 MPR, the ANAO’s review concluded that while the DMO continued to work toward improving the standard of risk management arrangements applying to Major Projects, the inherently uncertain nature of risks and issues meant that PDSS data could not be considered complete because of unknown risks and issues that may emerge in the future. For this reason, under arrangements for the priority assurance review, major risks and issues data in the PDSSs continues to remain out of scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, but is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of how risks and issues are managed.

1.45 In 2013–14 the ANAO again reviewed the developments with risk management at an enterprise and project level, in order to update its understanding of the DMO’s risk management systems and processes.

1.46 The development of the DMO’s enterprise risk management framework (ERMF), was identified in 2008–09, by the ANAO as a challenging but necessary step for the DMO in achieving its goal of improving project management. This was consistent with advice from the DMO that it would take some time before reliance could be placed on the framework.48 The ANAO highlighted particular challenges, such as the gap between project office risk management practices and those preferred practices, as set out in the ERMF.49

1.47 Risk management was also a major focus within the sustainment function of the DMO’s business in the Plan to Reform Support Ship Repair and Management Practices (Rizzo Report). The Rizzo Report stated that ‘Navy and DMO need to improve coordination and integrate their interdependent activities more effectively’50 and as a result, recommended that Navy and the DMO establish an Integrated Risk Management System.51 In response, the Interdependent Mission Management System (IMMS) was developed to provide joint visibility of risks at the enterprise level between the DMO and with Defence Capability Managers, and introduce greater accountability in relation to risk management. In May 2014, the Navy Reform Board endorsed the use of IMMS to manage interdependent risk in Navy more comprehensively.52

1.48 The DMO advised that in the maritime sustainment domain, risk registers have been developed at the division, branch and business unit levels, to reflect the different responsibilities for risk management at each level and show both the internal DMO risks and the interdependent risks with the Capability Manager. These registers are then uploaded via the Predict! risk management system to IMMS, to provide visibility of both internal and interdependent risks.

1.49 A system module relevant to the acquisition function of the business, has been integrated into IMMS, and which will eventually provide for a focus on acquisition activities, as outlined in the Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs).53 The DMO has also advised that it is intended that IMMS will also be used to integrate information captured in the DMO Assurance Management Information System (DAMIS), which is expected to collate, manage and report on all DMO assurance activities.

1.50 The ANAO appreciates that these developments at the corporate level are at a formative stage and will monitor progress further in 2014–15.

1.51 In 2012–13, the ANAO reported inconsistencies in risk management processes applied by project offices. At a project level, risk management guidance is provided by the DMO’s PRMM version 2.4, which was updated during the review period, and discussed earlier in this chapter in the financial framework section.

1.52 In 2013–14, the ANAO examined projects’ risk and issue logs, which are created and maintained utilising the mandated Excel or Predict! software.54 For the majority of project offices, risks and issues logs were maintained appropriately, however, they were often only updated infrequently and not in line with the requirement of PRMM.55 For example, the ANAO noted that some project offices only conduct their risk and issue reviews prior to scheduled Gate Reviews or ANAO site visits in relation to the MPR.

1.53 Other issues the ANAO observed included:

- risk and issue logs were incomplete or an inaccurate representation of project risks and issues;

- risks descriptors within Predict! were inconsistent with PRMM guidance56;

- incorrect application of DMO risk matrix calculations, resulting in inappropriate risk score outcomes; and

- where both Excel and Predict! are used by projects concurrently, inconsistencies existed between risk and issues logs.

1.54 In 2012–13 the ANAO also reported that project offices were no longer able to report their major risks and issues in the Monthly Reporting System, following a corporate review to reduce the reporting burden on project offices.57 Further, a risk health assessment conducted in September 2013 revealed that the DMO Executive does not receive systematic reporting on risks, nor is there a consistent approach for rolling up or aggregating disparate risks across business units.58

1.55 To achieve greater consistency in the approach to risk management and in response to the release of a Commonwealth Risk Management Policy on 1 July 2014, the DMO is developing a single Risk Management Manual, which is expected to be finalised in 2015.59

1.56 The ANAO will continue to review the DMO’s progress on risk management and reporting across the Major Projects in 2014–15.

Capability assessment framework

1.57 The DMO’s evaluation of the probability of delivering key capabilities, as denoted by Materiel Release Milestones (MRMs) and Completion Criteria in MAAs, specify the key elements required for the achievement of materiel release to the Australian Defence Force, and are set out as a ‘traffic light’ pie chart in Section 5.1 of each project’s PDSS. These measures of materiel capability delivery performance primarily focus on the anticipated future attainment of particular technical, regulatory and operational requirements.

1.58 During prior reviews, the ANAO found that the measures of capability delivery performance recorded in the Monthly Reporting System (MRS) did not always align with MAAs, and were inconsistent in terms of the degree of detail represented by each measure with reference to platform value and complexity. For example, the AWD Ships project ($7.9 billion) has four MRMs and Completion Criteria (IMR—Ship 1, MR 2—Ship 2, MR 3—Ship 3 and FMR), whereas the 155mm Howitzer project ($0.3 billion) has 23 MRMs and Completion Criteria.

1.59 In addition, MRMs and Completion Criteria often include schedule and cost factors which need to be excised from the PDSS in order to present data solely focussed on materiel capability delivery performance. The ANAO continued to observe these issues in 2013–14, and noted that there can be lengthy delays in receiving advice in relation to achievement of key milestones such as IOC and FOC, given the complexity of some projects.

1.60 Further, in relation to projects’ progression through each of the key milestones, IMR, IOC, FMR and FOC, the Capability Managers are required to review projects’ achievements against the MRMs and Completion Criteria.60 This underpins the relationship between the DMO and the Capability Managers in relation to the acquisition and delivery of capability, and is encapsulated within the specific details of the MAAs.

1.61 During 2013–14, the ANAO also observed that in relation to the ARH Tiger Helicopters project, the Capability Manager had co-signed the acceptance of achievement of FMR, albeit with significant caveats.61 The significance of the Capability Manager’s caveats has been reflected as a high risk to achievement of project completion and FOC, within the acceptance documentation.

1.62 However, the capability assessment provided within the PDSS indicates an expectation by the DMO of 100 per cent delivery for this project despite the risks as assessed by the Capability Manager.

1.63 Inevitably, the assessment of future capability delivery typically involves making certain assumptions in predicting achievements and consequently involves some subjectivity in approach. Taking into consideration this subjectivity and the inherent uncertainty of future events, this information continues to be excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review. However the ANAO has included the DMO’s capability forecasts in addition to our analysis of projects’ performance in relation to budgeted cost and schedule in Chapter 2 of Part 1.

1.64 Finally, the ANAO’s analysis of capability performance is further detailed in Chapter 2, for all projects in the MPR.

Review conclusion

1.65 The Auditor-General’s Independent Review Report takes into account the overall governance of major projects, the results of our examination of the DMO’s project management and reporting arrangements, and the results of our substantive procedures to gain assurance in relation to key information reported in PDSSs. In 2013–14, the results of the ANAO’s priority assurance review of the 30 PDSSs was that nothing has come to the attention of the ANAO that causes us to believe that the information and data in the PDSSs, within the scope of our review, has not been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with the Guidelines.

2. Analysis of Projects’ Performance

Introduction

2.1 Project performance information is important in the management and delivery of major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects). Such information provides an important focus for management attention to inform decisions to be made about the allocation of resources, to support advice to government on project progress and performance, and to allow for the Parliament and the public to assess the progress of the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) in discharging its responsibilities.

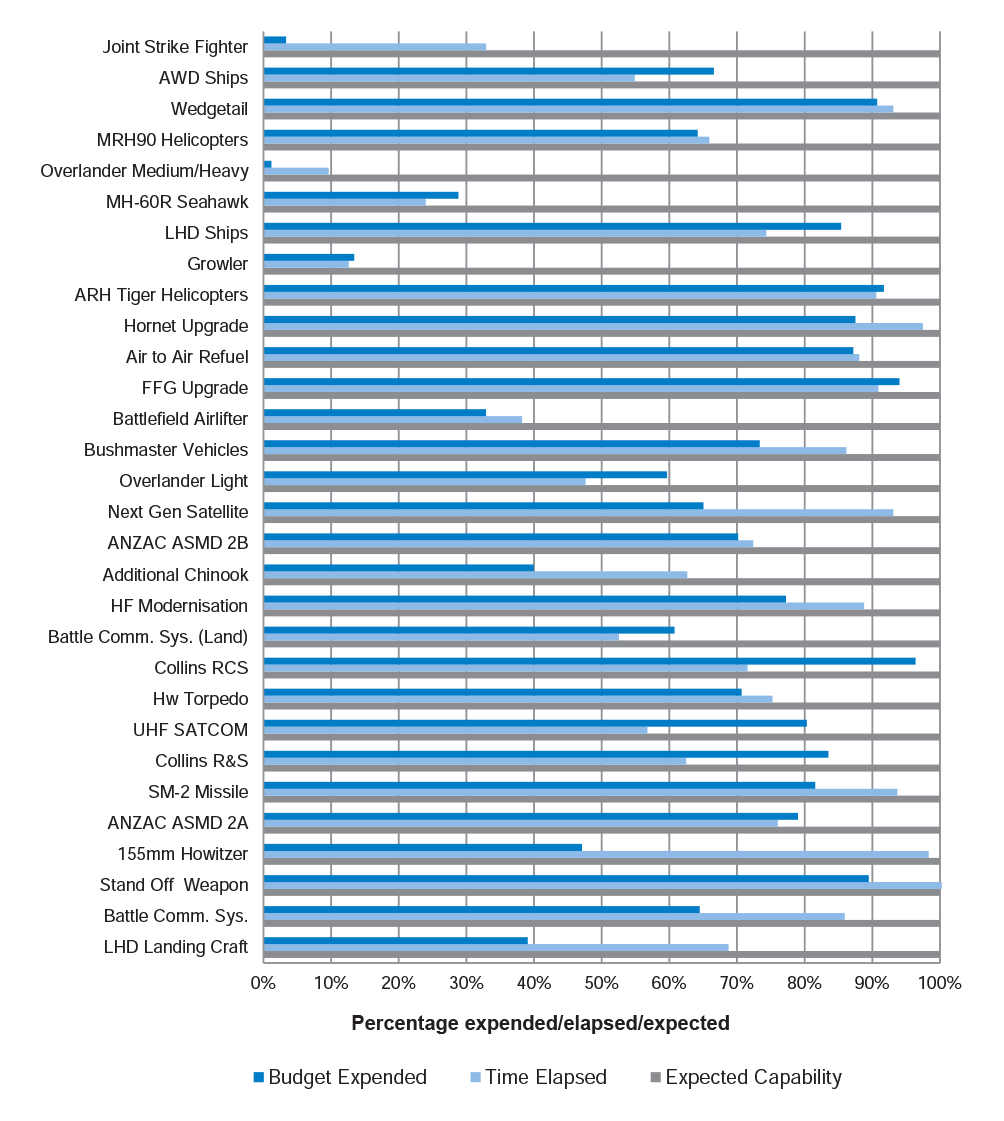

2.2 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has derived three key indicators to analyse the three major dimensions of a project’s progress and performance, utilising data extracted from the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs), and to provide a series of performance information snapshots. These indicators are the:

- percentage of budget expended (Budget Expended)—which measures the total expenditure as a percentage of the total current budget;

- percentage of time elapsed (Time Elapsed)—which measures the percentage of time elapsed from original approval to the forecast Final Operational Capability (FOC)62 63; and

- percentage of key materiel capabilities expected to be delivered (Expected Capability)—which is the DMO’s assessment of the likelihood of delivering the required level of capability.

2.3 These indicators are measured in percentage terms, to enable comparisons between projects of different characteristics, and to provide a portfolio view across project progress and performance.

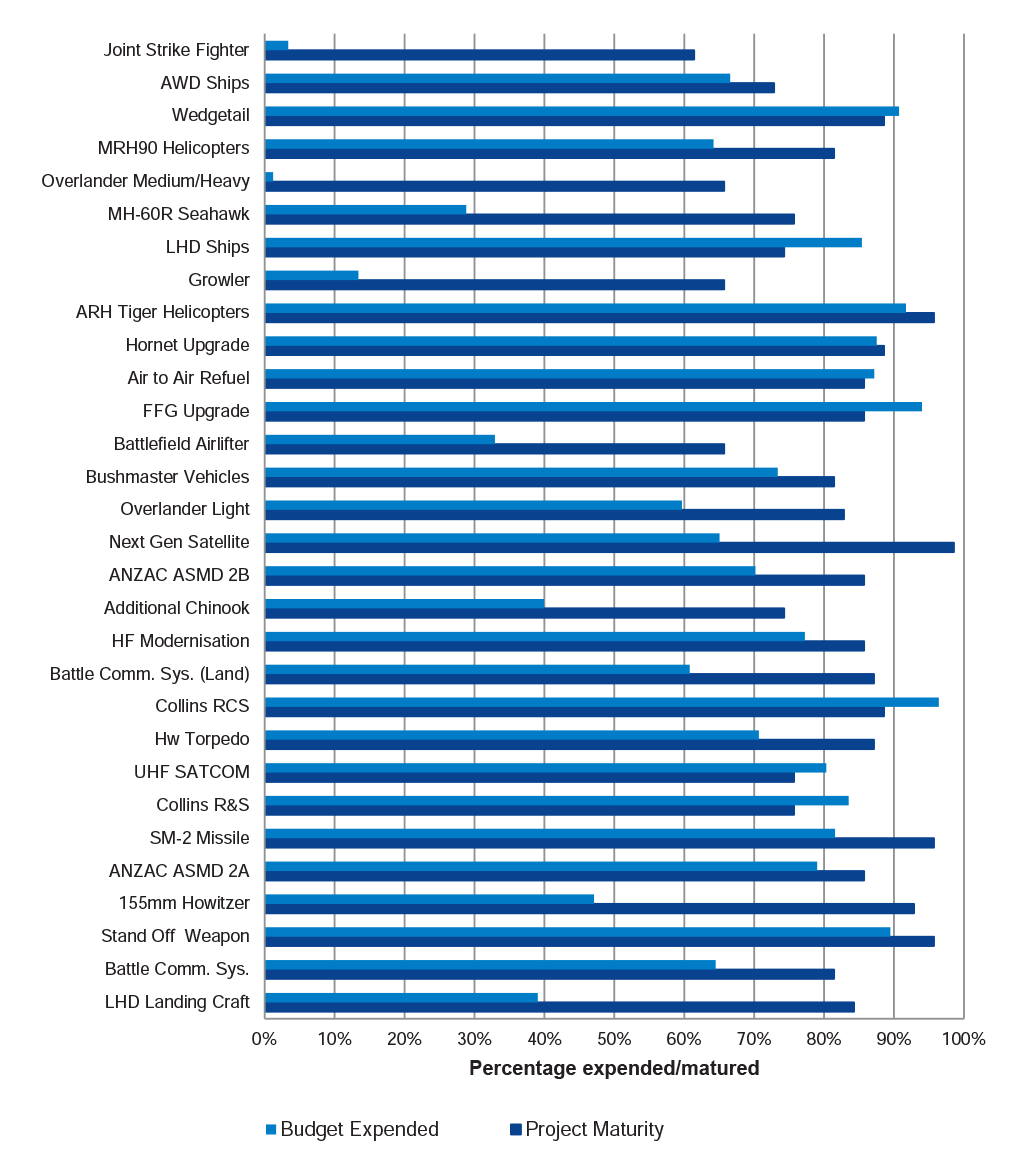

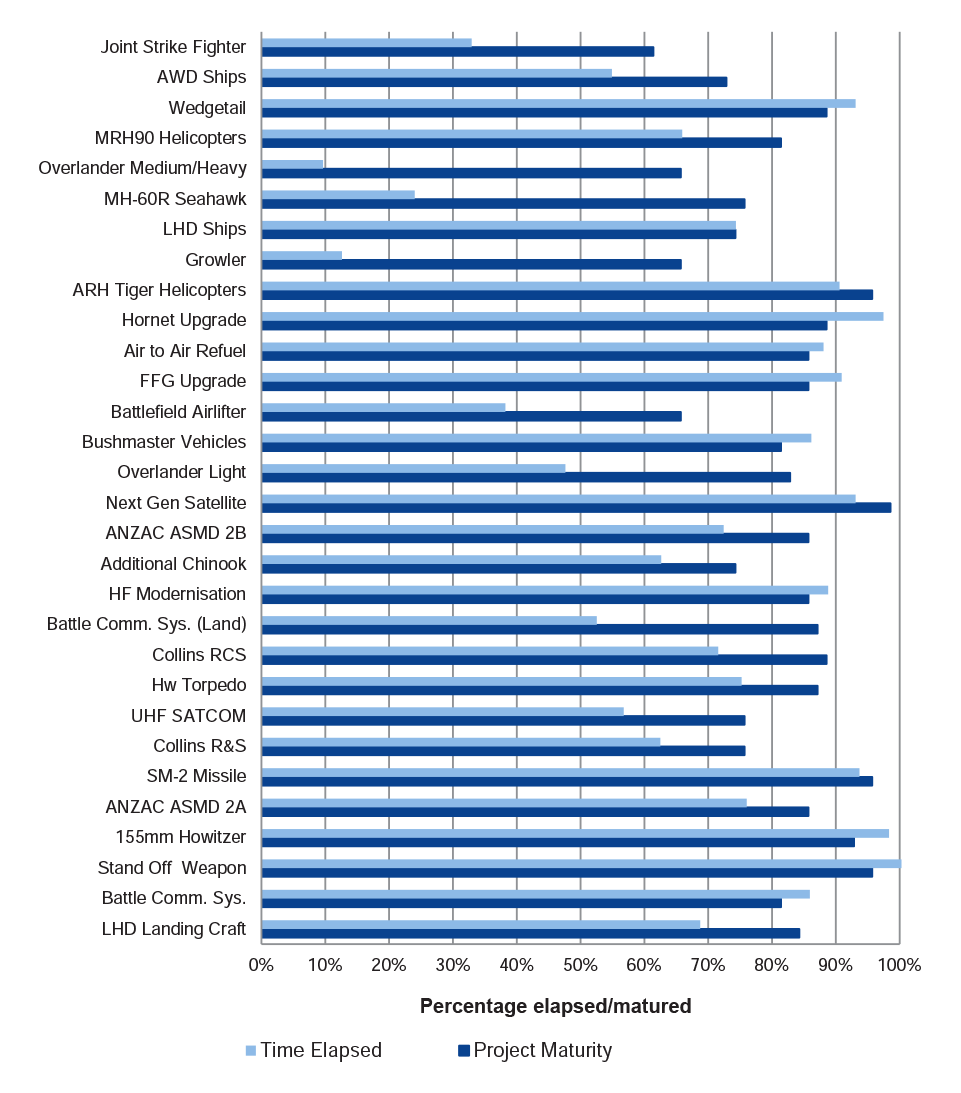

2.4 As in previous Major Projects Reports (MPRs), the ANAO has included an analysis of the key indicators against the DMO’s assessment of project maturity, at defined milestones64, as a percentage of the predefined maximum maturity score of 70 (Project Maturity).

2.5 As explained in the previous chapter, the DMO’s project maturity framework is an assessment methodology used for quantifying, in a practical and communicable manner, project maturity as projects progress through the capability definition and acquisition life cycle. Project maturity comprises a matrix of seven attributes: Schedule, Cost, Requirement, Technical Understanding, Technical Difficulty, Commercial, and Operations and Support, which are each assessed on a scale of one to 10.65 Project maturity is a composite performance indicator available to the DMO, Defence Executive and government for decision making, and to assess the overall status of Major Projects.66

2.6 However, the DMO has advised the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) that although project maturity scores are a helpful tool, they ‘…are ultimately indicative and advisory’67, and that a Materiel Implementation Risk Assessment (MIRA) which ‘…covers similar matters to the maturity scores but provides a narrative description of the risks and their impacts’ is summarised in the Government Approval Submissions instead.68

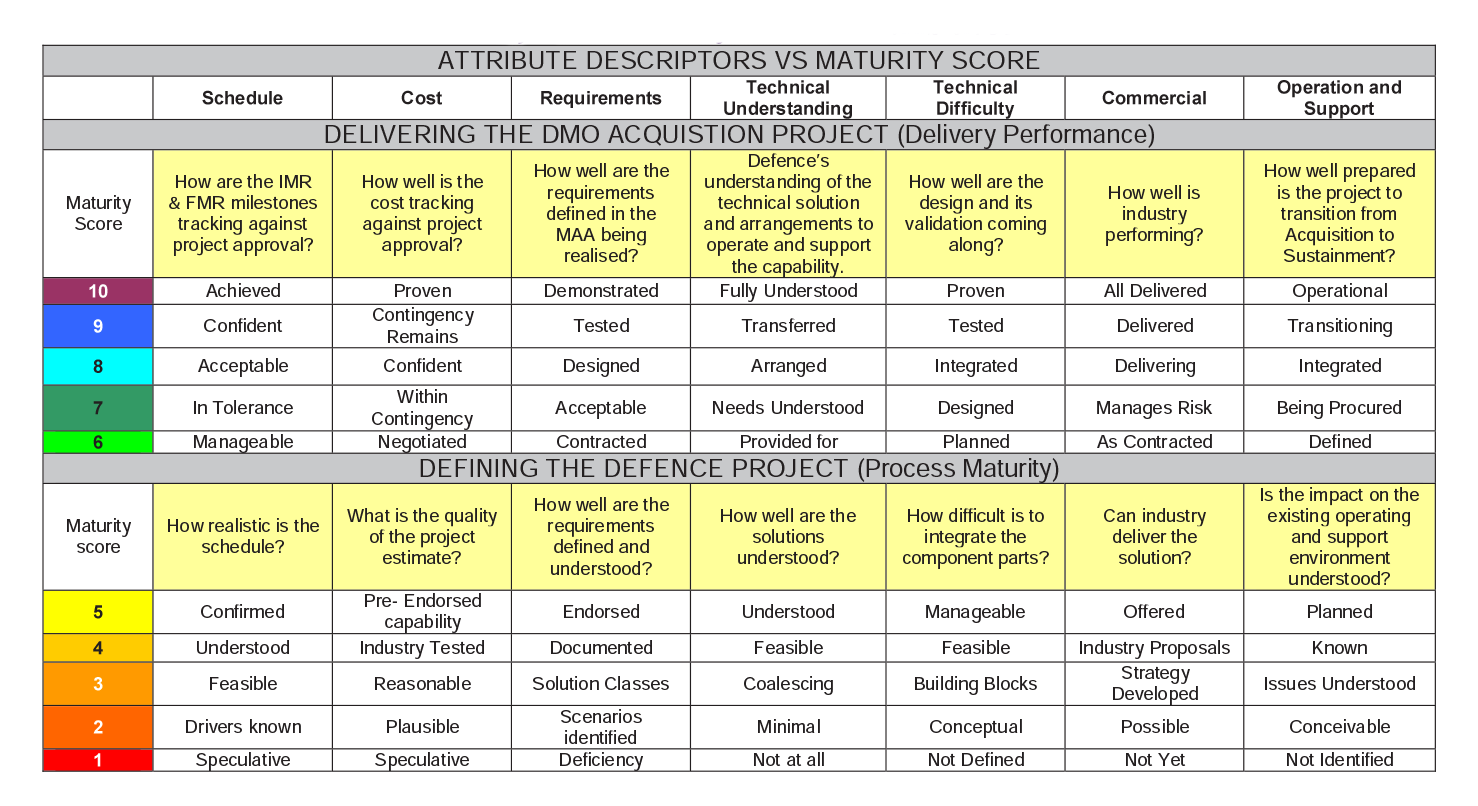

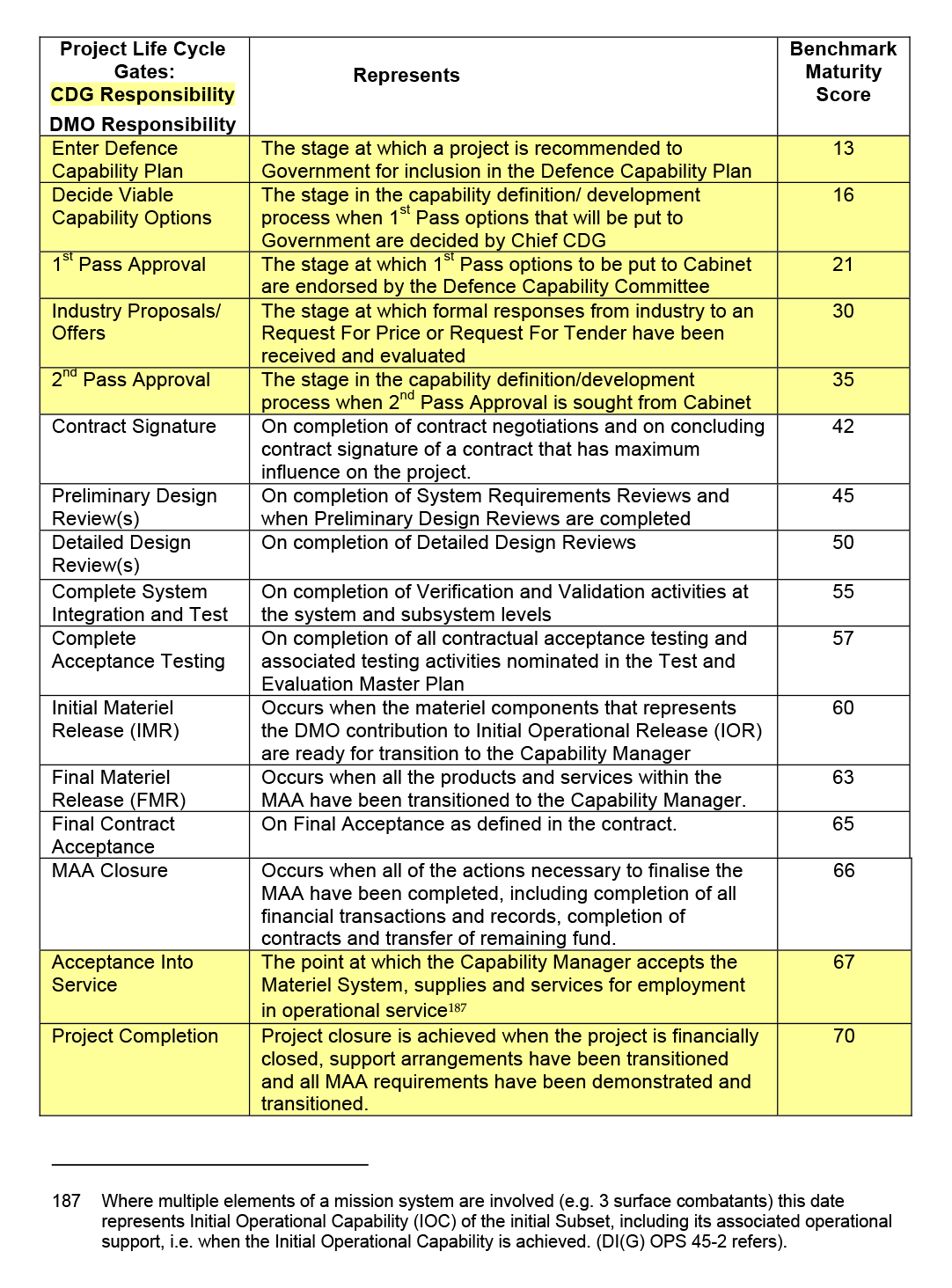

2.7 Nevertheless, the JCPAA has requested that the project maturity scores be maintained for the MPR until they are no longer required by the Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA.69 The DMO has agreed to this request.