Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Offshore Processing Centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea: Procurement of Garrison Support and Welfare Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) had appropriately managed the procurement of garrison support and welfare services at offshore processing centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island); and whether the processes adopted met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) including consideration and achievement of value for money.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In 2012 the Australian Government established offshore processing centres1 in the Republic of Nauru (Nauru) and Papua New Guinea (PNG) with the agreement of the Nauruan and PNG Governments.2 Under the agreements, the Australian Government was to bear all costs associated with the construction and operation of the centres. Transfers of asylum seekers to Nauru commenced on 14 September 2012 and to PNG on Manus Island3 on 21 November 2012.4

2. To underpin operations at the centres, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP or the department)5 entered into contracts for the delivery of garrison support and/or welfare services with a number of providers. Garrison support includes security, cleaning and catering services. Welfare services include individualised care to maintain health and wellbeing such as recreational and educational activities.

3. The department has undertaken a series of procurements relating to the garrison support and welfare services functions. The department applied limited tender procurement methods to acquire the services initially in 2012 and then again in late 2013. In 2015–2016, the department conducted an open tender procurement process for the services (for a single contract across both islands).

4. In October 2015, Transfield6 became the sole provider of all garrison support and welfare services to asylum seekers at the offshore processing centres7 in Nauru and on Manus Island. In February 2016 these arrangements were extended through to 28 February 2017 and in August 2016 the contract with Transfield was further extended until 31 October 2017. The contracts for garrison support and welfare services are set out in Table 1.1. The total combined contract value as at the end of March 2016, as reported on AusTender, was $3 045 million.

5. The Australian Government is a significant purchaser of goods and services and has in place resource management legislation and related policies that establish a framework for Government procurement and contracting. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) establish procurement principles that apply to all Australian Government procurement processes. The CPRs combine both Australia’s international obligations8 and good practice, and enable Government entities to design processes that are robust, transparent and instil confidence in the Australian Government’s procurement activities. The CPRs are issued under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)9 and articulate the requirements for officials performing duties in relation to procurement.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) had appropriately managed the procurement of garrison support and welfare services at offshore processing centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island); and whether the processes adopted met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) including consideration and achievement of value for money.

7. The audit examined procurements conducted since 2012, when the arrangements were first put into place, through to the open tender process which commenced in 2015. The ANAO reviewed DIBP and service provider records; and interviewed relevant DIBP officials (past and present) and stakeholders including service providers, tenderers and Government officials from Nauru and Papua New Guinea. The audit team also visited Manus Island and Nauru during August and September 2015. Due to shortcomings in DIBP’s record keeping system, DIBP was not able to provide the ANAO with assurance that it provided all departmental records relevant to the audit.10

Conclusion

8. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s (DIBP) management of procurement activity for garrison support and welfare services at the offshore processing centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island) has fallen well short of effective procurement practice. This audit has identified serious and persistent deficiencies in the three phases of procurement activity undertaken since 2012 to: establish the centres; consolidate contracts; and achieve savings through an open tender process.

9. Of most concern is the department’s management of processes for contract consolidation and the open tender. The Australian Government intended that these procurement processes would rein in the growing expense associated with managing the centres. In both cases, the approach adopted by the department did not facilitate such an outcome. The department used approaches which reduced competitive pressure and significantly increased the price of the services without Government authority to do so. The open tender process was cancelled by the department on 29 July 2016 and consequently had no outcome.

10. The conduct and outcomes of the tender processes reviewed highlight procurement skill and capability gaps amongst departmental personnel at all levels. Procurement is core business for Commonwealth entities and the deficiencies have resulted in higher than necessary expense for taxpayers and significant reputational risks for the Australian Government and DIBP. The audit’s two recommendations are intended to address:

- the significant skill and capability gaps identified amongst personnel at all levels in the department, including within the central procurement and budget units; and

- persistent shortcomings in the planning and conduct of the procurements, including in relation to record keeping, consistency and fairness in the treatment of suppliers, and the assessment of value for money.

Supporting findings

Establishing the offshore processing centres in 2012

11. For each of the procurements involved in this establishment phase, the department adopted limited tender arrangements. The department relied on the conditions for limited tender in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, relating to urgent and unforeseen circumstances.11 Given the circumstances which existed—the department was expected to establish operations for the offshore processing centres in Nauru and on Manus Island immediately—the use of limited tender was justified. However, there was limited specification of the type of services to be delivered, and no estimation of the expected value of individual procurements, as required by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

12. The department was unable to demonstrate the achievement of value for money in three of the four procurement processes.

- In engaging Transfield the department set aside an earlier approach to Serco.12 The department did not require Transfield to provide a proposal specifying services to be delivered and a price. As a result it was very difficult for the department to demonstrate that it had conducted a robust value for money assessment which considered the financial and non-financial benefits of the proposal. Transfield was instead assessed on its ability to respond in a short timeframe.

- The Salvation Army13 was also assessed as providing value for money on the basis of availability, without any specification of the services to be delivered or price.

- The department could not make available any records of how Save the Children14 was assessed as providing value for money.

- G4S15 was engaged following a limited tender procurement that involved a request for expressions of interest from five potential suppliers. This approach introduced competition in an otherwise limited tender procurement.

13. Contracts with service providers took between 16 and 43 weeks to negotiate, and the department relied on letters of intent or heads of agreement pending contract signature. Service requirements and prices were not settled until contracts were entered into. The approach adopted by the department introduced additional risk for the Commonwealth.

14. The department was not able to provide the ANAO with evidence that it implemented mechanisms to manage probity risk. The ANAO’s review, based on available evidence, of the conduct of these initial procurements indicates that suppliers were not always treated fairly or equally. In particular, Serco’s proposal was set aside without an opportunity to negotiate. The available records indicate that the department did not seek probity advice on this proposed course of action or document its decision-making. There are no available records of specific conflict of interest declarations having been made by departmental officers responsible for the initial procurements.

15. The department’s central procurement unit had limited effective oversight of the initial limited tender procurements. Available records indicate that program areas with responsibility for conducting the initial procurements obtained the necessary approvals to conduct limited tender procurements from the Chief Financial Officer, but not prior to commencing the procurement process as required by DIBP’s financial delegations.

Consolidation of contracts in Nauru and on Manus Island in 2013–14

16. The department again relied on paragraph 10.3(b) of the CPRs16 to conduct a limited tender, on the basis of urgent and unforeseen circumstances, to engage Transfield in Nauru and on Manus Island as part of a contract consolidation process. At the time, consolidation was considered an interim measure pending an open tender process in 2014. The available record does not indicate that urgent or unforeseen circumstances existed but suggests that the department first selected the provider and then commenced a process to determine the exact nature, scope and price of the services to be delivered.

- The department decided not to continue with the existing provider (G4S), but did not clearly document its reasons.

- Advice prepared by the department’s Central Procurement Unit was not consistent with the CPRs and the Department of Finance (Finance) guidance on key issues. In seeking advice from Finance, the Unit made written statements implying underperformance by service providers which was not supported by the evidence. The department subsequently referenced Finance’s support in briefings for its Minister.

17. DIBP’s approach to engaging Transfield through limited tender procurement removed competition from the outset. The services to be provided and related costs were not agreed with Transfield prior to G4S and The Salvation Army being advised that they would exit from service delivery on Manus Island. The proposed costs submitted by Transfield were higher than the department had anticipated and exceeded those charged by G4S and The Salvation Army for service provision on Manus Island.

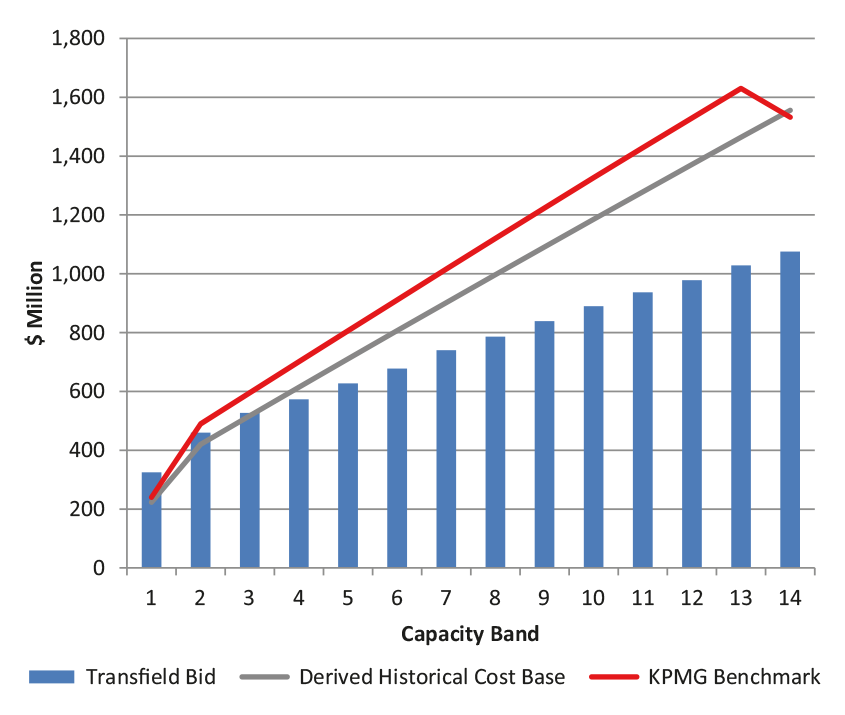

18. Ministers expected the consolidation of contracts to achieve innovation and savings. Savings were not realised and the basis which the department relied upon to demonstrate savings was unreliable. In particular:

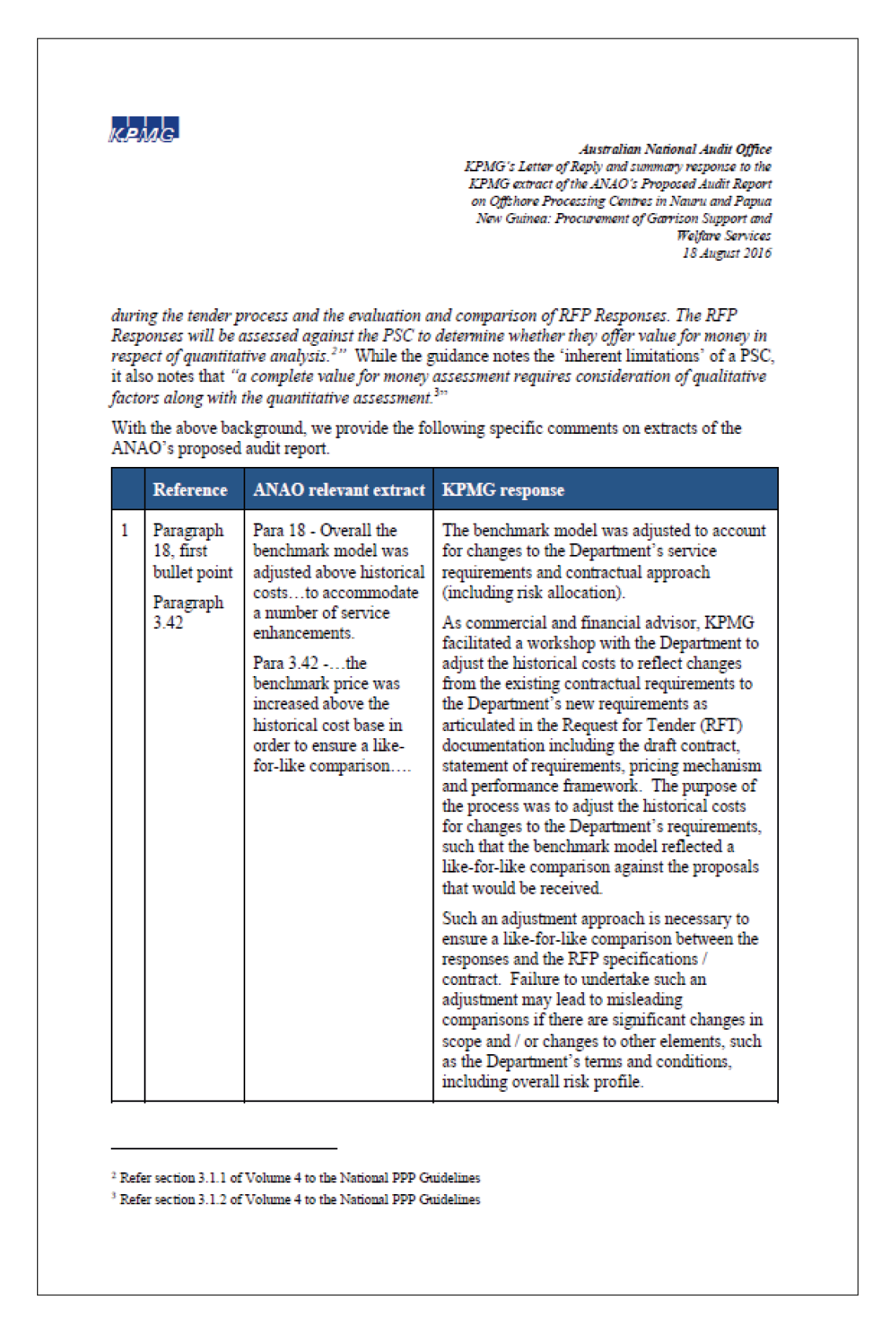

- The department applied a benchmark model to demonstrate the achievement of value for money. Overall the benchmark was adjusted above historical costs to account for changes to the department’s service requirements and contractual approach, upwards to $372 million, to accommodate a number of service enhancements. The Government had directed the department to reduce per-head costs. The department had no authority to increase the funding value of the contract above historic costs.17

- Separate benchmarks were developed for Nauru and Manus Island, but the department determined ‘value for money’ and claimed savings (against the benchmarks) on a combined basis. This allowed the department to demonstrate ‘savings’ by offsetting higher costs for Manus Island against lower costs for Nauru. While Transfield’s bid for Nauru was lower than historical costs, the bid for Manus Island exceeded historical costs by between $200 million and $300 million.

19. While the department based the negotiated contract price on a high capacity scenario, there was a steady drop off in new asylum seeker arrivals from a high of 1 647 in August 2013 to zero in March 2014. On this basis it was increasingly unlikely that the high capacity levels would eventuate. The resulting contract was volume driven, with significant economies of scale expected at high capacity levels. This contract exposed the Commonwealth to the risk of locking-in a high price for services delivered at lower capacity levels.

20. There is no available record of specific conflict of interest declarations having been made by departmental officers who were responsible for the procurement. There is also no available documentation to indicate whether the department performed due diligence checks on the successful tenderer (Transfield) or its subcontractors as part of the contract consolidation.

21. The Prime Minister had requested that per head costs be lower as a result of retendering the contracts, but the department did not calculate a per person cost. Finance advised the ANAO that under the consolidated contract, the per person per annum cost of holding a person in the offshore processing centres in Nauru and on Manus Island, was estimated at $573 111, at the time of the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2015-16.18 Prior to consolidation Finance estimated the cost at $201 000.

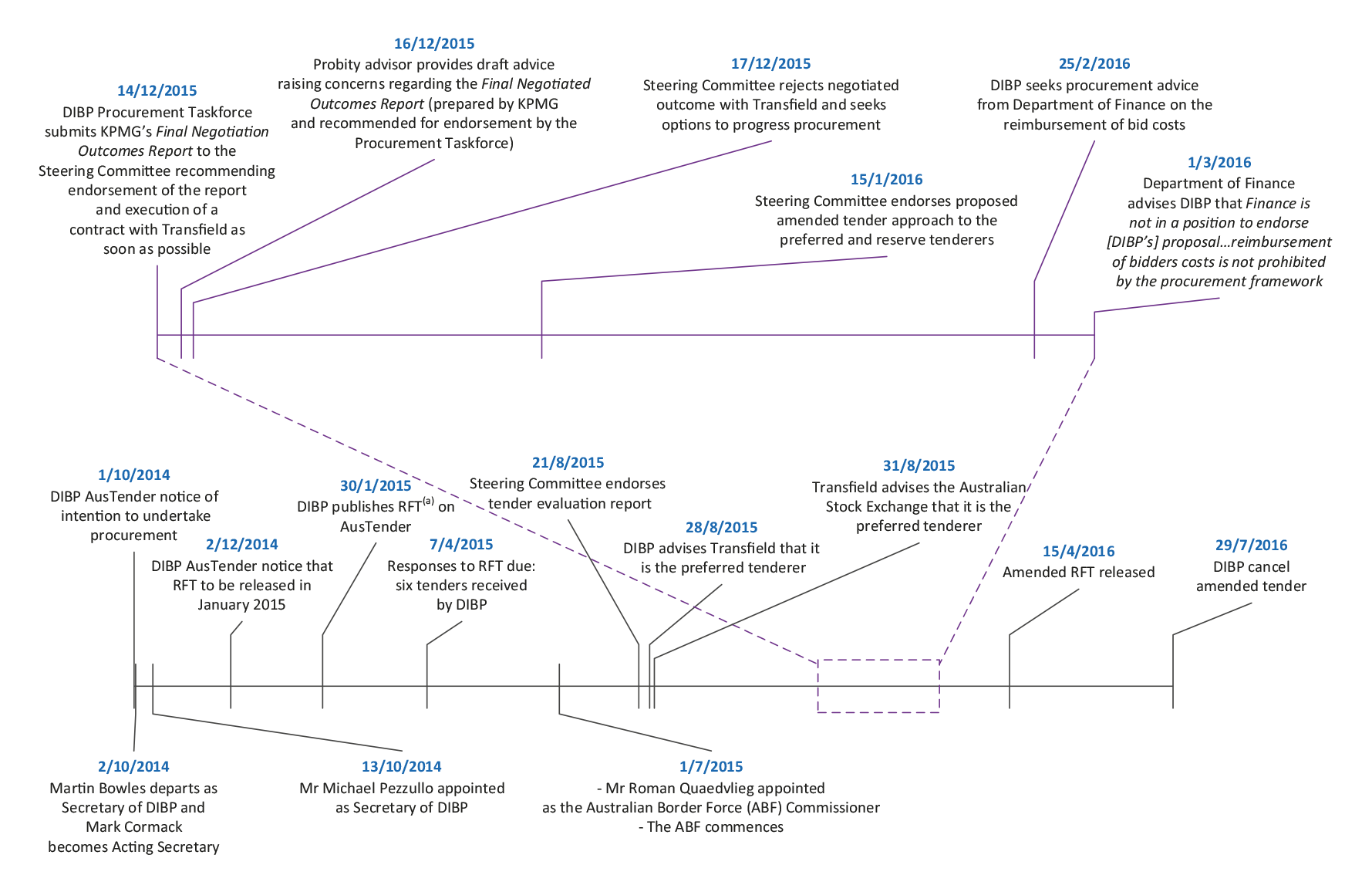

Open Tender Process from 2014 to 2016

22. While aspects of the department’s open tender planning addressed the requirements of the CPRs, insufficient consideration was given to:

- The use of benchmarking to determine overall value for money. The department’s approach involved comparing only the preferred tenderer’s negotiated final costs with a benchmark, and was incompatible with the CPRs. The CPRs require each eligible19 tenderer’s financial and nonfinancial benefit to be compared on a like for like basis with other eligible tenders.

- The scope of services set out in the statement of requirement. In particular, whether the department had policy authority to expand the services or increase the value of the contract beyond the contracts which were in place. The value of expanded services was estimated by an external adviser (KPMG) at between $594 million to $835 million above historical costs. The Government had not provided policy authority to expand the services or increase the funding value of the contract to accommodate service enhancements or adjustments.

23. The department’s tender evaluation processes were not sufficiently robust to meet a range of applicable CPR requirements. In particular:

- the department was unable to demonstrate that the original tender documents lodged through AusTender were used by evaluation team members for the tender evaluation;

- individual assessor records were incomplete and there were missing documents in relation to various aspects of the process;

- using compact disks rather than TRIM20 files did not provide sufficient control over the security of the tender documentation and the commercial material contained within those documents; and

- there were significant unquantified pricing risks related to most of the tender bids, which the department did not clarify prior to selecting a preferred tenderer and forming an opinion on value for money of the preferred and reserve tenderers.

24. The assessment of value for money focused on provider claims and referee reports and did not take into account the department’s own contract management experience with suppliers.

25. The department determined to only enter into negotiations with the preferred tenderer (Transfield). During the course of negotiations the department amended its requirements and accepted enhancements and adjustments to services which flowed through to a $1.1 billion increase in Transfield’s overall price. The department did not seek clarification or repricing from any other tenderers and instead set out to determine value for money by comparing the negotiated price with a benchmark. The benchmark was the cost of services provided in Nauru and on Manus Island, which had been procured via a non-competitive limited tender process in 2013–14. The approach adopted was not consistent with an open tender which requires that eligible tender bids are compared on a like for like basis.

26. The delegate had determined to finalise the procurement process and sign the contract. There are no available records to demonstrate that the delegate: considered if sufficient funds were available to enter into the commitment; considered if additional policy authority was required to accommodate the service enhancements negotiated; or questioned the increased cost of the bid.

27. A steering committee and independent probity adviser were key oversight mechanisms for the open tender process. Both were consulted after the negotiation team had reached agreement on a final negotiated outcome with Transfield and prior to the anticipated contract signing. The probity adviser identified that the department’s negotiation report appeared to include substantial modifications to the statement of requirement from that released to the market and that Transfield appeared to have been permitted to make material changes to its original tender, including significant overall price increases. The probity adviser considered that these developments raised significant probity and process risks, including the risk that the department was not in a position to determine whether the changes continued to represent best overall value for money compared with other tenderers.

28. After considering this advice the steering committee decided it was unable to determine whether the final negotiated outcome with Transfield demonstrated best value for money. The effective operation of these oversight mechanisms contributed to the department initiating an amended tender process. The Minister was advised of the amended tender process prior to it commencing, and that approvals for funding would need to be reassessed. The amended process only involved the preferred and reserve tenderers and was in effect a limited tender process. On 29 July 2016, in the course of this audit, the department cancelled the initial and amended request for tender. DIBP extended its contract with Transfield until 31 October 2017 and the department advised the ANAO on 29 August 2016 that it was conducting market testing to determine its next steps.

Recommendations

29. Procurement is core business for Commonwealth entities and deficiencies in capability, process and advice can result in higher than necessary expense for taxpayers and significant reputational risks for the Australian Government and responsible entities. The audit recommendations are intended to address significant weaknesses in the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s (DIBP) administration of procurement.

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 4.64 |

That the Department of Immigration and Border Protection address, as a priority:

Department of Immigration and Border Protection response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.65 |

That the Department of Immigration and Border Protection take practical steps to ensure adherence to the requirements of the resource management framework when undertaking procurements, including:

Department of Immigration and Border Protection response: Agreed |

Summary of entity responses

30. The proposed audit report was provided to the department and extracts were provided to:

- Other Australian Government entities—the Department of Defence, Department of Finance, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet;

- Non-Government Organisations—Allens Linklaters, Broadspectrum (Australia) Pty Ltd (formerly Transfield Services (Australia) Pty Ltd), G4S, International Organisation for Migration Australia, KPMG, Maddocks, Save the Children; Serco, The Salvation Army, and Wilson Security;

- Former departmental officials—Mr Martin Bowles PSM (former Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection); and Mr Mark Cormack (former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection); and

- Other individuals—The Hon Scott Morrison MP (former Minister for Immigration) and Mr Tony Shepherd AO (former Chair of Transfield and Chair of the National Commission of Audit).

31. Formal responses were received from the department, the Department of Defence, Broadspectrum, KPMG, The Salvation Army and Mr Shepherd. Feedback was received from the Department of Finance, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, G4S Australia, International Organisation for Migration Australia, Maddocks, Save the Children Australia; Serco Asia Pacific, Wilson Security, Mr Bowles and Mr Mark Cormack. Summary responses (where provided) are reproduced below and formal responses are included at Appendix 1.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

The procurement of garrison and welfare services for clients at the RPCs in Nauru and PNG has been undertaken in a highly complex and rapidly evolving environment.

When legislation was passed on 17 August 2012 enabling regional processing—four days after the release of the expert panel’s report—the Department needed to establish the necessary operational requirements immediately. Consistent with expectations, the first asylum seekers arrived in Nauru three weeks later on 14 September 2012. The Department met these requirements in an environment that was high-tempo, at the peak of national interest and complicated through logistics and uncertainties involved with processing in foreign countries. Delegates were required to make decisions on complex and high risk matters within very short timeframes.

The environment remains extremely complex. The Department provides support to the Governments of Nauru and PNG, who have effective control over the RPCs. lt remains open to these Governments at any time to make decisions which effect immediate changes to the administration of the centres. Accordingly, the Department has to adopt a procurement approach that is sufficiently agile to accommodate this environment.

The Department acknowledges that its decision-making processes in this complex and rapidly evolving environment have not been adequately documented at each stage of the procurement process. The absence of appropriate records makes it difficult to adequately demonstrate that the judgements made were appropriate and that due process was applied.

We have analysed our procurement and contracting practices and identified a number of improvements for implementation. These improvements will be progressively introduced as part of a broad reform programme that will provide confidence that all procurement is conducted in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and reflects industry best practice. This programme is detailed in the Department’s full response at the end of this report. Implementation will be monitored closely by the Department’s independently-chaired Audit Committee.

Broadspectrum (Australia) Pty Ltd (formerly Transfield Services Australia Pty Ltd)

The procurement by the Commonwealth of services with respect to the Offshore Processing Centres (OPC’s) involved multiple phases between 2012 and 2015 that evolved and changed over time. It included multiple changes in scope (including resettlement services), introduction of new service requirements and supply chains, transitioning in/out of other service providers and multiple new locations for service delivery. All of these factors are considered relevant to a balanced assessment of the quality of the offering with respect to services provided at the OPCs.

While we have done our utmost to respond in a comprehensive manner to the ANAO’s Draft Report, our ability to do so has been constrained in circumstances where the Draft Report that has been provided to us is heavily redacted, incomplete and where we do not have visibility of the information relied on by the ANAO.

KPMG

KPMG was engaged by the Department to provide:

- Negotiation support for the consolidation of contracts in Nauru and Manus Island in December 2013; and

- Financial, commercial and negotiation advice and project support in regards to the onshore and offshore procurement processes in August 2014.

KPMG notes that a benchmark approach, or its equivalent, is commonly used for the procurement of other long term, high value contracts that involve a complex risk allocation, including complex Public Private Partnership (PPP) procurements. KPMG maintains that the use of a Benchmark model for the procurement of Garrison and Welfare Services provides additional complementary analysis to the comparative value for money assessment.21

KPMG also maintains that it acted openly and transparently at all times, and provided timely disclosure, with regard to its relationships with potential tenderers and the management of potential conflicts of interest in connection with the Garrison and Welfare Services procurement processes. In particular, KPMG notes that its letter issued in July 2015 was not the first time KPMG had brought its role as Transfield’s external auditor and provider of advisory services to the Department’s attention. KPMG had advised the Department of its relationship with Transfield on numerous occasions prior to this.22

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 On 28 June 2012 the Prime Minister and Minister for Immigration and Citizenship announced that an expert panel would provide a report on the best way forward to prevent asylum seekers risking their lives on boat journeys to Australia.23 The expert panel’s report, released on 13 August 2012, included a range of disincentives, including the establishment of offshore processing centres24 in the Republic of Nauru (Nauru) and Papua New Guinea (PNG).

1.2 The centres were subsequently established with the agreement of the Nauruan and PNG Governments.25 Under the agreements, the Australian Government was to bear all costs associated with the construction and operation of the centres. Transfers of asylum seekers to Nauru commenced on 14 September 2012 and to PNG on Manus Island26 on 21 November 2012.27

1.3 To underpin operations at the centres, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP or the department)28 entered into contractual arrangements for the delivery of garrison support and/or welfare services. Garrison support includes security, cleaning and catering services. Welfare services include individualised care to maintain health and well-being such as recreational and educational activities.

Procurement of garrison support and welfare services in Nauru and on Manus Island

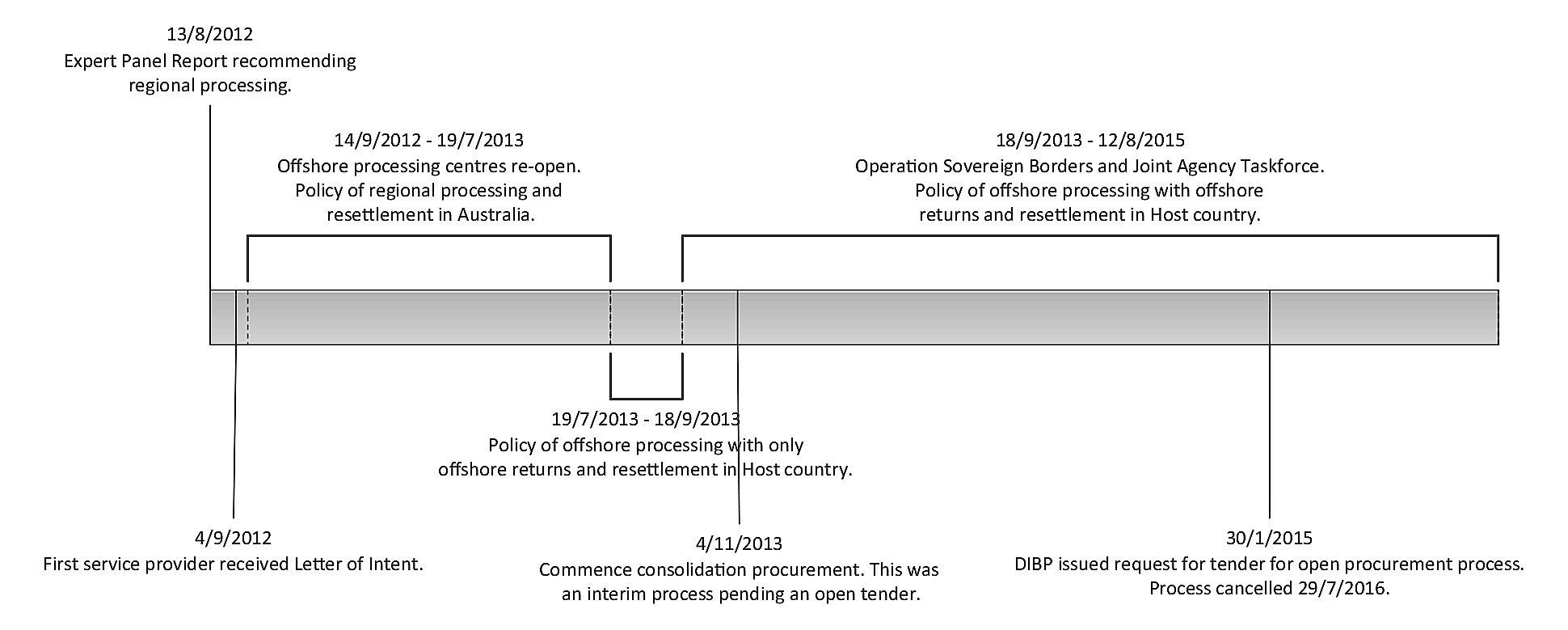

1.4 The department has undertaken a series of procurements relating to the garrison support and welfare services functions. The department applied limited tender procurement methods to acquire the services initially in 2012 and again in 2013–2014 as part of a contract consolidation process. In 2015, the department conducted an open tender procurement process for the services (for a single contract across both islands) which was underway at the time of this audit and was cancelled in July 2016. Figure 1.1 shows a timeline of key policy points and procurement actions.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of key policy points and procurement actions

Source: ANAO analysis of documentation

1.5 In October 2015, Transfield29 became the sole provider of all garrison support and welfare services in Nauru and on Manus Island, and in February 2016 these arrangements were extended to 28 February 2017. They were further extended to October 2017 following the cancellation of DIBP’s open tender process in July 2016. The contracts for garrison support and welfare services are set out in Table 1.1. The total combined contract value as at the end of March 2016, as reported on AusTender, was $3 045 million.

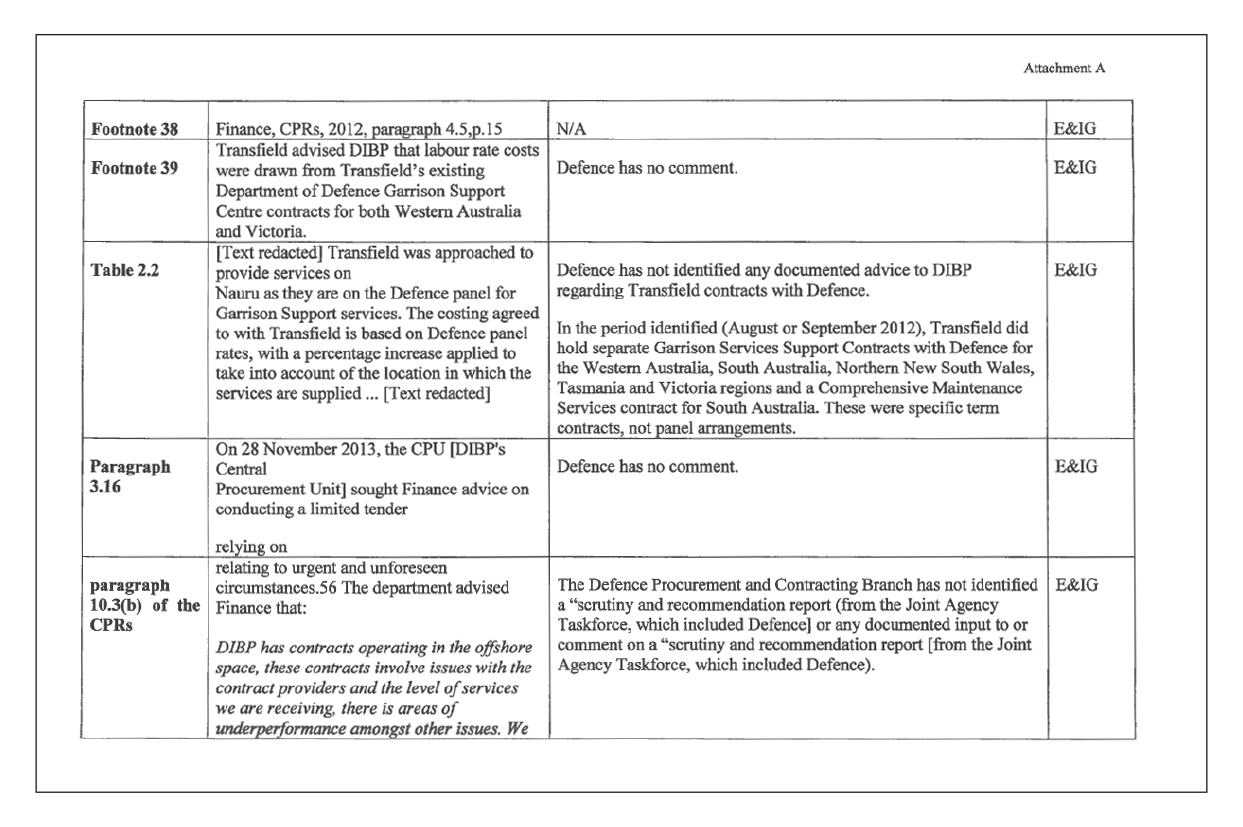

Table 1.1: Garrison support and welfare services contracts since 2012, Nauru and Manus Island

|

Organisation |

Time period |

Services provided |

Total AusTender value ($ millions)a |

|

Transfield Services (Australia) Pty Ltd |

September 2012–March 2014 |

Nauru—Garrison support |

$351 |

|

March 2014–February 2017b |

Nauru and Manus Island— Garrison support and welfare services |

$2190 |

|

|

G4S Australia and New Zealand |

October 2012–March 2014 |

Manus Island—Garrison support |

$245 |

|

Save the Children |

October 2012–June 2013 |

Care and support services |

$8 |

|

August 2013–August 2014 |

Provision of services to minors |

$37 |

|

|

September 2014–October 2015 |

Welfare and education services |

$100 |

|

|

May 2014–January 2015 |

Refugee settlement services |

$15 |

|

|

The Salvation Army |

September 2012–January 2014 |

Welfare support for single men |

$99 |

|

TOTAL |

$3045 |

||

Note a: AusTender is the Australian Government’s procurement information system. Relevant entities must report contracts and amendments on AusTender within 42 days of entering into (or amending) a contract if they are valued at or above the reporting threshold. For each contract reported, the entity must report the total value of the contract (including GST where applicable).

Note b: Extended to October 2017. Contract extension costs are not included in the table.

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender information.

Commonwealth procurement

1.6 The Australian Government is a significant purchaser of goods and services and has in place resource management legislation and related policies that establish the framework for procurement and contracting. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) establish procurement principles that apply to all Australian Government procurement processes. The CPRs combine both Australia’s international obligations30 and good practice, and enable entities to design processes that are robust, transparent and instil confidence in the Australian Government’s procurement activities. The CPRs are issued under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)31 by the Finance Minister and articulate the requirements for officials performing duties in relation to procurement. The CPRs are revised from time-to-time. The CPRs that apply to this audit are the version of July 2012 and the current CPRs issued in July 2014.32 The audit report reflects which version of the CPRs applied in a given context.

1.7 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs and requires the consideration of the financial and non-financial costs and benefits associated with procurement. The CPRs recognise that value for money is enhanced by encouraging competition through open tender processes, while also providing for other procurement methods in defined circumstances.

1.8 The PGPA Act requires entities to promote the proper use and management of public resources.33 Under the CPRs proper use means efficient, effective, economical and ethical use. The CPRs provide that:

6.2 Efficient relates to the achievement of the maximum value for the resources used. In procurement, it includes the selection of a procurement method that is the most appropriate for the procurement activity, given the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

6.3 Effective relates to the extent to which intended outcomes or results are achieved. It concerns the immediate characteristics, especially price, quality and quantity, and the degree to which these contribute to specified outcomes.

6.4 Economical relates to minimising cost. It emphasises the requirement to avoid waste and sharpens the focus on the level of resources that the Commonwealth applies to achieve outcomes.

6.5 Ethical relates to honesty, integrity, probity, diligence, fairness and consistency. Ethical behaviour identifies and manages conflicts of interests, and does not make improper use of an individual’s position.34

1.9 Under the CPRs, officials must also establish processes for the identification, analysis, allocation and treatment of risks when conducting procurements.

1.10 The CPRs describe three methods that officials can use when conducting procurements (see Box 1 below). These are open, prequalified and limited tender. The conditions for limited tender at or above the relevant procurement threshold are set out in Box 2. Regardless of the procurement method chosen, entities must apply the mandatory requirements set out in the two divisions of the CPRs:

- Division 1—rules applying to all procurements regardless of value. Officials must comply with the rules of Division 1 when conducting procurements; and

- Division 2—additional rules that apply to all procurements valued at or above the relevant procurement thresholds (unless exempted under Appendix A of the CPRs, see Box 3 below).

|

Box 1: Procurement methods and thresholds |

|

The following are extracts from the CPRs: Open tender—

Prequalified tender—

Limited tender—

Procurement thresholds

|

|

Source: Finance, CPRs, 2014.

|

Box 2: Conditions for limited tender for procurement at or above the relevant procurement threshold |

|

The CPRs outline the following conditions for limited tender:

|

|

Source: Finance, CPRs, 2014.

|

Box 3: Exemptions from Division 2 of the CPRs |

|

The following is an extract from Division 2 of the CPRs:

|

|

Note a: This includes information and advertising services for the development and implementation of information and advertising campaigns.

Source: Finance, CPRs, 2014, Appendix A.

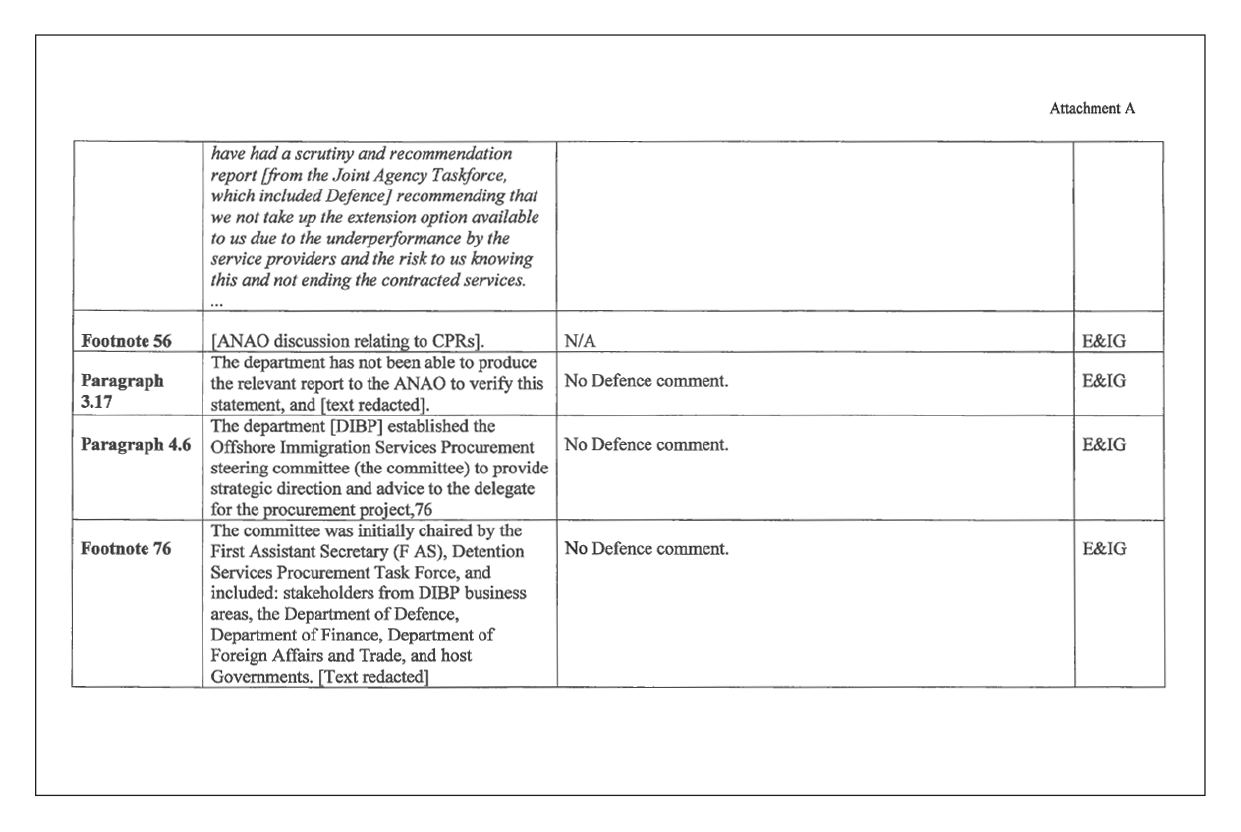

1.11 Typical considerations for procurements at or above the relevant threshold are outlined in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Choosing a procurement method

Note a: Conditions for limited tender for procurement at or above the relevant procurement threshold are presented in Box 2 of this report and the Exemptions from Division 2 of the CPRs are outlined in Box 3 of this report.

Source: ANAO based on Department of Finance guidance.

1.12 The procurement framework emphasises the importance of being accountable and transparent in all procurement activities. Under the CPRs:

Accountability means that officials are responsible for the actions and decisions that they take in relation to procurement and for the resulting outcomes. Transparency involves relevant entities taking steps to enable appropriate scrutiny of their procurement activity.35

Officials must maintain for each procurement a level of documentation commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement. Documentation should provide accurate and concise information on:

a. the requirement for the procurement;

b. the process that was followed;

c. how value for money was considered and achieved;

d. relevant approvals; and

e. relevant decisions and the basis of those decisions.36

1.13 Entities determine their own procurement practices, consistent with the CPRs, through Accountable Authority Instructions37 and, if appropriate, supporting operational guidelines. The purpose of entity central procurement units (CPUs)38 is to provide procurement expertise and advice to entity officials undertaking procurement processes and to assist in ensuring relevant requirements are met. Within DIBP limited tender procurements over the relevant threshold were also required to be agreed by the Chief Financial Officer for amounts above $1 million.

DIBP advisory processes

1.14 The department’s line management has responsibility for procurement matters. DIBP’s central procurement unit provides advice to officers undertaking procurement activities. For the purposes of the garrison and welfare contracts, a policy implementation group was established by the then Secretary to provide day to day advice on strategic matters.39 A Secretaries Committee on Immigration, which included central agency participants, was also formed to provide strategic oversight of the implementation of Government policy in this area.

Audit approach

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.15 The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) had appropriately managed the procurement of garrison support and welfare services at offshore processing centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island); and whether the processes adopted met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) including consideration and achievement of value for money.

1.16 The audit examined procurements conducted since 2012, when the arrangements were first put into place, through to the open tender process which commenced in 2015.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- DIBP adhered to the requirements of the financial management framework when undertaking procurements (including procurement and budget requirements); and

- DIBP applied sound procurement practice.

Audit methodology

1.18 The ANAO reviewed DIBP and service provider records; and interviewed relevant DIBP officials (past and present) and stakeholders including service providers, tenderers and Government officials from Nauru and Papua New Guinea. The audit team also visited Manus Island and Nauru during August and September 2015. Fieldwork was conducted between March 2015 and March 2016.

1.19 Due to shortcomings in DIBP’s record keeping system, the ANAO’s review was based on the available records. In particular, departmental records often took the form of e–mail correspondence. DIBP was not able to provide the ANAO with assurance that it provided all departmental records relevant to the audit. During the period under review in this audit there was a complete turnover of senior departmental personnel responsible for the administration of the procurements.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $1 116 208.

2. Establishing the offshore processing centres in 2012

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s (DIBP) procurement processes and decisions relating to the procurement of garrison support and welfare services when establishing the offshore processing centres. The chapter also examines whether the procurement processes adopted were sound and met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

Conclusion

In deciding to establish the offshore processing centres in 2012, the Australian Government sought to achieve immediate outcomes. Asylum seekers first arrived in Nauru within three weeks of the relevant Government decision, providing very little time to put in place all the necessary contract arrangements for the operation of the centre. The department relied on limited tender approaches provided for in the CPRs, relating to urgent and unforeseen circumstances. Whilst this approach was open to the department and justified in the circumstances, more competition could have been applied to encourage better value for money outcomes for the Commonwealth.

The ANAO has identified issues with each of the four procurement processes undertaken at this time, and limited compliance with the CPRs. In summary:

- there was limited specification of the type of services to be delivered, and no estimation of the maximum value of individual procurements, as required by the CPRs;

- the department’s available records indicated that with the exception of the process undertaken to engage G4S, DIBP did not establish that the procurement outcomes represented value for money;

- the available evidence indicated that potential suppliers were not always treated fairly or equitably—in engaging Transfield to undertake services in Nauru, the department set aside an earlier approach to Serco without an opportunity to negotiate. The department did not require Transfield to provide a proposal which specified the services delivered and costs, prior to offering Transfield the work;

- there was no available evidence of mechanisms to manage probity risks; and

- there was limited documentation around each of the procurement processes, to transparently record the department’s decision-making.

Introduction

2.1 As part of the initial establishment of the offshore processing centres in Nauru and on Manus Island in 2012, the department undertook a series of limited tender procurements for garrison support and welfare services. For each of these procurements the ANAO examined:

- the planning for and use of limited tender;

- value for money;

- contract negotiations;

- probity arrangements; and

- involvement of the central procurement unit (CPU).

In adopting limited tender processes, did the department have regard to the mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules?

For each of the procurements involved in this establishment phase, the department adopted limited tender arrangements. The department relied on the conditions for limited tender in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, relating to urgent and unforeseen circumstances.40 Given the circumstances which existed—the department was expected to establish operations for the offshore processing centres in Nauru and on Manus Island immediately—the use of limited tender was justified. However, there was limited specification of the type of services to be delivered, and no estimation of the expected value of individual procurements, as required by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Planning for the initial procurements and use of limited tender

2.2 In deciding to establish the offshore processing centres in August 2012, the Australian Government sought to achieve immediate outcomes. While no dates were set for the commencement of the arrangements, the Government considered that the effectiveness of the arrangements in deterring boat arrivals would be determined by the speed with which the processing centres could be agreed with Nauru and Papua New Guinea (PNG), and established. The first asylum seekers arrived in Nauru on 14 September 2012, some three weeks after the Australian Government’s decision. In order to procure garrison support and welfare services, the department undertook a series of procurements which resulted in contracts being entered into with Transfield Services, the Salvation Army, G4S and Save the Children.

2.3 The then departmental Secretary, Mr Martin Bowles PSM, advised the ANAO that:

In 2012 and in response to the Report of the Expert Panel on Asylum Seekers, the department worked within an exceptionally tight time period to establish Offshore processing. Planning in this context was exceptionally difficult. The changing nature of the challenges and the dynamic nature of policy development meant that the department often had to develop responses in an agile way to meet urgent requirements. This in and of itself presented significant challenges requiring policy, process, logistics, personnel and service providers to change and evolve in a fluid and often undefinable environment.

Consideration was also given to the operational complexities of service provision in the onshore network (specifically recognising that the network had increased exponentially over the previous 6 months with a significant number of new detention facilities opening). While a single onshore and offshore provider was considered, this was balanced with the risks relating to the service provider’s current and future capability (noting the various pressures that continued to be faced in the onshore environment).

2.4 Department of Finance (Finance) guidance advises officials to ensure that the delegate is aware of the intended approach to market and, depending on the nature, complexity and risk of the procurements, is involved in the planning stages of the procurement.41 The department commenced the procurement processes for the garrison support and welfare services functions within days of the Australian Government’s decision. Reflecting the priority, risks and sensitivities associated with the procurement, senior managers, including the then Secretary of the department, were directly involved in some of the processes.

2.5 Initially the department approached two suppliers (in late August 2012) to conduct all services across both centres. One supplier, Serco (who at the time was the provider of detention services onshore), provided a response. The department also held discussions with a second supplier, the International Organisation for Migration. Subsequently, the department separated the procurement into four processes. Three processes involved the department adopting a sole supplier approach. The fourth process, while also limited tender, involved more than one potential supplier, and so had an element of competition.

2.6 The 2012 Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) provided that an entity must only conduct a procurement at or above the relevant procurement threshold ($80 000) through limited tender in defined circumstances (known as ‘conditions for limited tender’ and listed in Division 2 of the CPRs). One circumstance is where, for reasons of extreme urgency brought about by events unforeseen by the entity, the goods and services could not be obtained in time under open tender or prequalified tender.42 Each of the procurements undertaken in 2012 was valued at above the procurement threshold. DIBP considered that the circumstances and time pressures it faced to commence operations provided justification for the use of limited tender.

2.7 Where an entity relies on a condition for limited tender under Division 2 of the CPRs, it is also required to comply with the rules for all procurements appearing in Division 1 of the CPRs. While the department had by 2012 acquired extensive experience in the operation of onshore detention centres43 through contractual arrangements, there was limited specification of the type of services required to be delivered, and no estimation of the maximum value of individual procurements, as required by the CPRs.

2.8 The 2012 CPRs stated that the expected value of each procurement must be estimated before a decision on the procurement method was made. The expected value was the maximum value (including GST) of the proposed contract, including options, extensions, renewals or other mechanisms that may be executed over the life of the contract.44 The purpose of this requirement was to ensure that the likely Commonwealth financial commitment was properly considered and an appropriate procurement method selected.

2.9 A timeline of key events for the establishment of offshore processing centres in Nauru and on Manus Island is shown at Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Timeline of key events for the establishment of offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG (Manus Island)

Note a: Request for expression of interest (REOI).

Source: ANAO analysis of documentation from DIBP and service providers.

Did the department demonstrate value for money through the procurement and negotiation processes?

The department was unable to demonstrate the achievement of value for money in three of the four procurement processes.

- In engaging Transfield the department set aside an earlier approach to Serco.45 The department did not require Transfield to provide a proposal specifying services to be delivered and a price. As a result it was very difficult for the department to demonstrate that it had conducted a robust value for money assessment which considered the financial and non-financial benefits of the proposal. Transfield was instead assessed on its ability to respond in a short timeframe.

- The Salvation Army46 was also assessed as providing value for money on the basis of availability, without any specification of the services to be delivered or price.

- The department could not make available any records of how Save the Children47 was assessed as providing value for money.

- G4S48 was engaged following a limited tender procurement that involved a request for expressions of interest from five potential suppliers. This approach introduced competition in an otherwise limited tender procurement.

Contracts with service providers took between 16 and 43 weeks to negotiate, and the department relied on letters of intent or heads of agreement pending contract signature. Service requirements and prices were not settled until contracts were entered into. The approach adopted by the department introduced additional risk for the Commonwealth.

Value for money

2.10 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs. The 2012 CPRs provided that delegates must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that the procurement achieved a value for money outcome. Determining value for money requires processes commensurate with the scale and scope of the procurement and a comparative analysis of the relevant costs and benefits throughout the whole procurement cycle (whole of life costing).49

2.11 Under the CPRs a value for money assessment should include consideration of factors such as:

- fitness for purpose of the proposal;

- the potential supplier’s experience and performance history;

- flexibility of the proposal (including innovation and adaptability over the lifecycle of the procurement); and

- whole-of-life costs.50

2.12 The ANAO’s findings in relation to each procurement process are set out below.

Approach to Serco

2.13 The department initially approached Serco verbally (17 August 2012) and then through a request for expression of interest (19 August 2012) for proposals for garrison support services in the centres in Nauru and on Manus Island. The department’s request documentation stated that costs would not be binding, were intended to be indicative only and the information would be used to inform further discussions.

2.14 Serco responded to the request by the department’s deadline, indicating its availability to perform the services required. For each location, Serco’s proposal provided daily pricing options which varied depending on contract duration (three months, six to nine months and 12 months) and the number of asylum seekers. The proposal included pricing assumptions and details of specified additional costs that would need to be reimbursed by the department.51 The proposal also stated that costs were indicative only, and based on the limited information and timeframe available. Costs would be subject to review once an adequate scope was developed, contract terms agreed and time was available to access the facilities for a comprehensive review.

2.15 On 28 August 2012 (six days after submitting its response) Serco was advised that DIBP would not pursue the proposal further. DIBP has not provided the ANAO with evidence of a value for money assessment of Serco’s proposal or why Serco’s proposal was not further considered.

2.16 The then Secretary of the Department Mr Bowles, advised the ANAO that:

a number of internal discussions with the internal Policy Implementation Group were held. To my recollection the discussion to not proceed with the Serco proposal was largely based on the pressures on the onshore network managed by Serco. At the time the Department was exponentially increasing the number of onshore detention centres and increasing onshore detention capabilities. Numbers in onshore detention were increasing and at the height there were approximately 12,000 people in onshore detention centres. Monthly arrivals were continuing to increase, each month seeing a stepped increase on the previous month, these arrivals, aligned to the policy settings at the time were placing the onshore detention network and our service providers under pressure.

2.17 Key events in relation to DIBP’s approach to Serco are listed in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: Key events in relation to DIBP’s approach to Serco

|

Date |

Key events in relation to DIBP’s approach to Serco based on review of available documentation |

|

17 Aug 2012 |

DIBP provided Serco with a verbal brief on services to be delivered. |

|

19 Aug 2012 |

DIBP provided Serco with a written request for an indicative quote for services in Nauru and on Manus Island. |

|

22 Aug 2012 |

Serco provided DIBP with an indicative proposal. |

|

28 Aug 2012 |

DIBP advised Serco that it would not be pursuing the proposal further. |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIBP documentation.

Approach to the International Organisation for Migration

2.18 The department’s records of its approach to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) are limited. They indicate that IOM was approached (or approached the department) verbally in the week ending 17 August 2012. Further discussions were held over the following two weeks. Work at this time included preparing talking points for the Minister to meet with IOM. The department’s records do not indicate whether that meeting occurred. The department has advised the ANAO that it did not provide a request for quote to IOM at the time and did not receive a proposal detailing services to be provided or costs. The department’s records indicate that on 28 August the department provided a draft contract to IOM. The statement of work in this draft contract was incomplete and no fees were included. On 30 August the department determined not to pursue an arrangement with IOM any further.

2.19 The then Secretary of the Department Mr Martin Bowles, advised the ANAO that once negotiations with IOM failed it was decided to focus on Transfield as capacity, capability and timing were critical. Transfield had demonstrated this in their garrison provider work within Defence.

Engagement of Transfield Services

2.20 Available DIBP records indicate that on 24 August 2012 Transfield approached the then Secretary of the department by email to enquire if it could assist in Nauru:

It has been a while since we have spoken. How is it going in the world of the Department of Immigration, I am sure it is very busy to say the least.

Reason for contact is to enquire how Transfield Services can support you in your task in Nauru.

We can leverage DSG capability by mobilising a combination of our HSIP team and our Garrison team. As a trusted and proven partner of the Commonwealth this will give a highly compliant and flexible solution we believe.

We have recently successfully completed a similar exercise at Warmun.

2.21 The then Secretary responded verbally to Transfield and followed up by email on 31 August 2012 about performing garrison support services in Nauru. Later that day the department emailed Transfield a copy of the same request documentation provided to Serco (without deleting the Serco references).

2.22 In commenting on the brevity of the documentation provided, the department’s delegate for the procurement advised Transfield:

I’d be happy to arrange a little more oral briefing this afternoon to put a bit more flesh on the bones, so to speak, of the skimpy paper we forwarded to [Transfield employee]…

2.23 Transfield responded to the department on 3 September 2012 with a two page letter. The letter stated that Transfield understood the scope of the engagement but did not provide details of the services Transfield offered or the associated costs. Subsequently, Transfield provided the department with hourly wage rates for certain categories of workers by email (4 September 2012). There are no available DIBP records to demonstrate that the department attempted to compare the hourly wage rates provided by Transfield with the daily operational rates provided in the Serco proposal.

2.24 On 4 September 2012, the department provided Transfield with a letter of intent advising that it proposed to enter negotiations to agree on an initial Heads of Agreement (HOA) for the provision of interim garrison support services in Nauru. The intention was to finalise the HOA prior to Transfield commencing services on 11 September 2012. The department also advised Transfield that a contract for the provision of garrison support services in Nauru would be finalised as early as possible in October 2012.

2.25 As noted in paragraph 2.10, achieving a value for money outcome requires a comparative analysis of the relevant costs and benefits throughout the whole procurement cycle (whole of life costing), and a process commensurate with the scale and scope of the procurement. Available records indicate that the department solicited limited information from Transfield, making it very difficult for the department to demonstrate that it had conducted: a process commensurate with the value of the procurement; and a robust value for money assessment which considered the relevant financial and non-financial benefits of the proposal. Further, the services to be delivered were not specified by the department and a price was not elicited from Transfield.

2.26 The department acknowledged in its approval documentation that due to the urgency of the situation there was limited scope for value for money assessments to be done on the essential requirements. The department’s value for money assessment was made on the basis that Transfield was able to respond and could deliver the required services in a short period of time. There was also no estimate of the full value of the services Transfield would provide until 1 February 2013 (the date of contract execution), when the department obtained internal approval for the commitment of $184 263 702 for a 12 month period. By this time the department had already approved $31.6 million under a Heads of Agreement. Transfield signed a contract on 1 February 2013 after having delivered services in Nauru for five months.

2.27 In considering value for money the department was also required, under the CPRs, to consider Transfield’s experience and performance history.52 A key reason documented by the department for its selection, was that Transfield was on a Department of Defence panel for garrison support services (see Table 2.2).53 Defence advised the ANAO that it did not have such a panel arrangement in place at that time. Defence further advised that it has no record of a request from DIBP seeking its views in August or September 2012 regarding the performance of its garrison support suppliers. Available DIBP records indicate that it had regard to Defence panel rates but it is not clear how this was possible if no Defence panel existed. 54

2.28 The department’s value for money assessment is provided at Table 2.2 below.

Table 2.2: Transfield—value for money assessment

|

Provider, initial expenditure approved and date of approval |

DIBP value for money assessment |

|

Transfield $6.1 million 19 September 2012 |

DIBP approval documentation states: ‘The Department sought proposals from Serco Australia Pty Ltd and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) for the provision of services. Serco’s proposal did not represent value for money. After discussions with IOM, they advised that the organisation would be unable to provide the services within the time frames required by the Department. Given the urgency of the situation there is limited scope for value for money assessments to be done on essential requirements. Transfield was approached to provide services on Nauru as they are on the Defence panel for Garrison Support services. The costing agreed to with Transfield is based on Defence panel rates, with a percentage increase applied to take into account of the location in which the services are supplied… All Service Providers have been able to respond to and can deliver the required services in a short period of time. This is a key element of the value for money assessment.’ |

Source: ANAO presentation of DIBP approval documentation.

2.29 The 2012 CPRs required entities to establish processes for the identification, analysis, allocation and treatment of risk when conducting procurements.55 Available documentation indicates that key risks were not assessed with respect to the Nauru offshore processing centre when establishing the arrangements. This was subsequently highlighted by Mr Keith Hamburger AM—in his 8 November 2013 Review into the 19 July 2013 Incident at the Nauru Regional Processing Centre—as a critical missing element essential to guide decisions relating to infrastructure and operations and to mitigate duty of care risks, particularly in the highly complex offshore processing environment.56

Engagement of The Salvation Army and Save the Children

2.30 The Salvation Army was engaged to provide welfare services at offshore processing centres between 14 September 2012 and 31 January 2014. The department advised that it engaged The Salvation Army after the organisation approached and offered its services. Save the Children was engaged to provide welfare services at the offshore processing centres between 10 October 2012 and 31 October 2015. The department was not able to provide the ANAO with documents relating to how the initial approaches with these organisations occurred.

2.31 The option of adopting limited tender processes for these procurements, on the basis of urgent and unforeseen circumstances, was available to the department under the CPRs. The department did not document why it adopted a sole source approach over alternatives such as a competitive limited tender process, given there were alternative suppliers of welfare services. While a record of the value for money assessment was available for The Salvation Army, no record was available for Save the Children. The department’s value for money assessment for The Salvation Army is provided below at Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: The Salvation Army—value for money assessment

|

Provider, initial expenditure approved and date of approval |

DIBP value for money assessment |

|

The Salvation Army $2.1 million 19 September 2012 |

DIBP approval documentation states: ‘Given the urgency of the situation there is limited scope for value for money assessments to be done on essential requirements. The Salvation Army is a not for profit organisation. They indicated that costings (not finalised at the time) would be based on an actual costs basis (staff and equipment) with a mark-up to cover the corporate and administrative costs incurred Onshore. All Service Providers have been able to respond to and can deliver the required services in a short period of time. This is a key element of the value for money assessment.’ |

Source: ANAO presentation of DIBP approval documentation.

Engagement of G4S

2.32 G4S was engaged to provide garrison support services at Manus Island following a limited tender procurement that involved a request for expressions of interest being sent to five potential suppliers.57

2.33 Potential suppliers were given five days to respond. Sending the request to more than one supplier introduced competition in an otherwise limited tender procurement and provided a firmer basis for the department’s assessment of value for money. DIBP’s tender evaluation documentation indicates that the department compared the responses of the three suppliers who submitted proposals (including G4S and Transfield).58 The department was unable to provide a copy of one proposal from an unsuccessful supplier. The department’s approval documentation reports that Transfield’s bid was found to be four times more expensive than G4S. The remaining supplier’s bid was lower than the other bids but its scope of services was more limited.

2.34 The tender evaluation team recommended the engagement of G4S as the service provider for Manus Island. A summary of the department’s value for money assessment is provided below at Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: G4S—value for money assessment

|

Provider, initial expenditure approved and date of approval |

DIBP value for money assessment |

|

G4S $30 million 12 October 2012 |

DIBP approval documentation states: ‘The Evaluation Team considers G4S to be the preferred supplier as they are considered to be value for money due to, but not limited to: the technical evaluation; the price; and the risk.’ |

Source: ANAO presentation of DIBP approval documentation.

Contract negotiations

2.35 The 2012 CPRs required that unless a relevant entity determines that it is not in the public interest to award a contract59, it must award a contract to the tenderer that the relevant entity has determined:

- satisfies the conditions for participation;

- is fully capable of undertaking the contract; and

- will provide the best value for money, in accordance with the essential requirements and evaluation criteria specified in the approach to market and request documentation.60

2.36 The department entered into contract negotiations after it placed each of the service providers on the ground in Nauru and on Manus Island. In the absence of a contract, providers operated under a letter of intent or heads of agreement. The department’s correspondence to providers confirmed that it intended to agree on a contract ‘as early as possible’. In the event it took up to 43 weeks for contracts to be signed. Table 2.5 shows the duration of contract negotiations after the commencement of service delivery by each provider.

Table 2.5: Duration of contract negotiations after the commencement of services in Nauru and on Manus Island

|

Service provider |

Weeks between commencement of services on site and executed contract |

Date services commenced on sitea |

Arrangement under which services commenced, and date arrangement executed |

|

Transfieldb |

20 |

11 September 2012 |

Letter of Intent, 4 September 2012 |

|

The Salvation Armyb |

20 |

11 September 2012 |

Letter of Intent, 4 September 2012 |

|

Save the Childrenc |

43 |

10 October 2012 |

Heads of Agreement, 17 April 2013 |

|

G4Sc |

16 |

10 October 2012 |

Letter of Intent, 12 October 2012 |

Note a: Services commenced in Nauru on 11 September 2012 and on Manus Island on 10 October 2012. The services providers had commenced preparation and incurred costs prior to these dates.

Note b: Transfield and The Salvation Army commenced services in Nauru.

Note c: Save the Children and G4S commenced services on Manus Island.

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.37 The department entered the arrangements while still negotiating price and the specifics of the services to be delivered. Services and price were not agreed between the parties until contract negotiations ended. In the case of Transfield this was almost five months after it commenced operations. For G4S it was four months after the commencement of operations.

2.38 The department advised the ANAO that letters of intent and heads of agreement offered less legal protection than a contract but were part of its strategy to mitigate scope and cost risk as it allowed the department to tighten performance specifications and costs, based on a period of actual operation. The department also advised that entering into a contract immediately may have locked the Commonwealth into provisions and arrangements which would be difficult to undo or amend. The approach adopted by the department increased risk for the Commonwealth and DIBP was not able to provide the ANAO with records documenting the strategy or any consideration of risks relating to the approach adopted. For example, a risk based approach would have considered why the contract used for onshore services could not have been adapted to suit the offshore environment or the draft contract prepared and provided to IOM for services on Nauru (see paragraph 2.18) could not have been used. At the very least, it would have been prudent to assess the risks arising from the speedy establishment of the centres.

Did the department establish processes to manage probity risks?

The department was not able to provide the ANAO with evidence that it implemented mechanisms to manage probity risk. The ANAO’s review, based on available evidence, of the conduct of these initial procurements indicates that suppliers were not always treated fairly or equally. In particular, Serco’s proposal was set aside without an opportunity to negotiate. The available records indicate that the department did not seek probity advice on this proposed course of action or document its decision-making. There are no available records of specific conflict of interest declarations having been made by departmental officers responsible for the initial procurements.

Probity arrangements

2.39 The 2012 CPRs required that officials undertaking procurement must act ethically throughout the procurement. The CPRs advised that ethical behaviour includes:

- recognising and dealing with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest;

- dealing with potential suppliers, tenderers and suppliers equitably, including by seeking appropriate internal or external advice when probity issues arise, and not accepting inappropriate gifts or hospitality;

- carefully considering the use of public resources; and

- complying with all directions, including relevant entity requirements, in relation to gifts or hospitality, privacy requirements and the security provisions of the Crimes Act 1914.61

2.40 Based on available evidence, the ANAO’s review of the conduct of these initial procurements indicates that suppliers were not always treated fairly or equally. In particular:

- Serco’s proposal, which contained indicative costings, was set aside without evidence of a value for money assessment or the opportunity to negotiate; and

- the department advised Transfield that it proposed to enter into negotiations with them one day after receiving Transfield’s letter and details of hourly wage rates.

2.41 There is no DIBP documentation indicating that the department sought probity advice on its proposed course of action and no documented record of its decision making. In the course of this audit the then Secretary of the department advised the ANAO that he recalled speaking to internal lawyers relating to probity issues.

2.42 The department was not able to provide the ANAO with:

- evidence that it implemented mechanisms to manage probity risk; or

- records of conflict of interest declarations having been made by departmental officers responsible for the initial procurements.

2.43 In the absence of a procurement specific process to manage probity risk, the ANAO requested access to the more general declarations of interest of relevant Senior Executive Service (SES) staff, to establish whether any relevant declarations had been made by them. The department could not provide all of the declarations for relevant senior executives and advised that records for former staff may not have been retained. On request, the then Secretary, Mr Bowles, provided the ANAO with his declaration to cover the period.

Were relevant approvals by the Chief Financial Officer obtained prior to commencing the procurement process?

The department’s central procurement unit had limited effective oversight of the initial limited tender procurements. Available records indicate that program areas with responsibility for conducting the initial procurements obtained the necessary approvals to conduct limited tender procurements from the Chief Financial Officer, but not prior to commencing the procurement process as required by DIBP’s financial delegations.

The central procurement unit

2.44 In 2012 DIBP’s financial delegations required all limited tender procurements over the relevant threshold ($1 million) be approved by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO). Under these arrangements the area within the department with program responsibility conducted the procurements while the CFO (who had responsibility for the central procurement unit) approved the use of limited tender for each relevant procurement.

2.45 For Transfield and the Salvation Army the CFO approved the use of limited tender after the program area had already identified the suppliers and had provided letters of intent allowing services to commence.

2.46 CFO approval for conducting a limited tender to engage service providers on Manus Island was sought prior to going out for a request for quote from potential suppliers but was not provided until after the process was completed. G4S commenced operations in October 2012. In January 2013 the program area sought approval to amend the terms of the limited tender from an initial 12 months to include a provision to extend for a further period of 12 months. The Assistant Secretary, Property, Procurement and Contracts Branch (the CPU) noted ‘I cannot support a 12 month extension option when our reason for limited tender is urgent and unforeseen’, and the CFO approved a limited tender for a period of 12 months with no extension.

2.47 The department has not retained the original limited tender approval documentation for Save the Children. Available documentation indicates that Save the Children commenced providing services in October 2012 and approval for limited tender was obtained on 17 April 2013. Prior to the original Heads of Agreement expiring (on 30 June 2013), the department sought approval (on 24 June 2013) from the Assistant Secretary, Property, Procurement and Contracts Branch (not the CFO) to continue to engage Save the Children for a further seven months via a contract. The basis for this request was under paragraph 10.3(e) of the 2012 CPRs:

for additional deliveries of goods and services by the original supplier or authorised representative that are intended either as replacement parts, extensions or continuing services for existing equipment, software, services or installations, where a change of supplier would compel the agency to procure goods and services that do not meet requirements for compatibility with existing equipment and services.

2.48 On 25 June 2013 the Assistant Secretary approved the request noting that ‘this is an unusual proposal. The services are not of a type usually contemplated under 10.3(e) of the CPRs. However, I consider that this proposal is broadly consistent with the intent of that clause.’

3. Consolidation of contracts in Nauru and on Manus Island in 2013–14

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s (DIBP) procurement processes and decisions relating to the consolidation of contracts for the procurement of garrison support and welfare services in Nauru and on Manus Island in 2013–14. It also examines whether the processes adopted were sound and met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

Conclusion

The department decided to consolidate contracts for the provision of garrison support and welfare services and conducted a limited tender relying on paragraph 10.3(b) of the CPRs– relating to urgent and unforeseen circumstances. The available record does not indicate such circumstances existed. The department first selected the provider and then commenced a process to determine the exact nature, scope and price of the services to be delivered.

The reasons for not continuing with the existing provider (G4S) were not clearly documented. Advice prepared by the department’s Central Procurement Unit was not consistent with the CPRs and the Department of Finance (Finance) guidance on key issues. In seeking advice from Finance, the Unit made written statements implying underperformance by service providers which was not supported by the evidence. The department subsequently referenced Finance’s support in briefings for its Minister.

Engaging Transfield through limited tender procurement placed the department in a position where it removed competition from the process at the outset. When a price was put forward by Transfield it was higher than anticipated and far exceeded that charged by G4S.

The department applied a benchmark model to demonstrate the achievement of value for money. Overall the benchmark was adjusted above historical costs, upwards to $372 million, to accommodate a number of service enhancements. The Government had directed the department to reduce per-head costs. The department had no authority to increase the funding value of the contract above historic costs.62

Separate benchmarks were developed for Nauru and Manus Island, but the department determined ‘value for money’ and claimed savings (against the benchmarks) on a combined basis. While Transfield’s bid for Nauru was lower than historical costs, the bid for Manus Island exceeded historical costs by between $200 million and $300 million.

The intent of the consolidation was to achieve innovation and savings. In estimating savings the department based its calculations on higher capacity levels which were never achieved. The department was aware of the fall in the number of new boat arrivals in early 2014, but continued to use higher than actual levels to determine expected costs. This approach resulted in a risk of the Commonwealth locking-in a premium for service delivery under the contract.

The Prime Minister had requested that per head costs be lower as a result of retendering the contracts, but the department did not calculate a per person cost. Finance advised the ANAO that under the consolidated contract, the per person per annum cost of holding a person in the offshore processing centres in Nauru and on Manus Island at the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2015–16 in December 2015, was $573 111. Prior to consolidation Finance estimated the cost at $201 000.