Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Delivery of Health Services in Onshore Immigration Detention

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s administration of health services in onshore immigration detention.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Under the Migration Act 1958 (the Act), a person who is not an Australian citizen and does not hold a valid visa is an unlawful non-citizen. The Act requires unlawful non-citizens to be detained until they are removed from Australia, granted a visa or removed to a regional processing country. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) administers the Act and the Government’s policy in relation to immigration detention.

2. Immigration detention in Australia occurs in held facilities and community detention, and is collectively known as ‘onshore’ detention. The total onshore detainee population reduced significantly over the period from July 2014 to May 2016—from 6730 to 2228 detainees. As at 31 May 2016, there were 1570 detainees in held detention and 658 in community detention. With the exception of Christmas Island Detention Centre (located in the Indian Ocean 2600 kilometres north-west of Perth) and Yongah Hill Detention Centre (located 100 kilometres east of Perth), all detention facilities are located in capital cities.

3. The department is responsible for providing a range of services to people in immigration detention, including health care. A specialist provider of medical services, International Health and Medical Services (IHMS), has been contracted by the department to deliver health services in held and community detention under several contracts since 2004. The current contract is valued at $438 million over the five year period from December 2014 to December 2019.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s administration of health services in onshore immigration detention.1 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Was a robust contract in place to support the effective and efficient delivery of health services?

- Were effective arrangements established to monitor health service provision and manage the contractor’s performance?

- Was health service delivery and contractor performance appropriately monitored?

Conclusion

5. The department’s administration of health services in onshore immigration detention has been improved by the strengthening of contractual arrangements with the selected provider of health services. The current contract, which was developed by the department based on a strategic analysis of shortcomings that had arisen under earlier contracts, includes: mechanisms to control the risk of over-servicing and uncontrolled cost escalation; clearly defined deliverables; and a performance monitoring regime containing provisions for the application of penalties and incentives. However, to be able to give assurance that contract objectives are being achieved, there is further scope for the department to improve its administration of health service delivery, primarily through strengthening arrangements for monitoring:

- the quality of the health services that are being delivered; and

- key areas of health service delivery risk (such as services to detainees with mental health conditions).

Supporting findings

Developing the contractual framework

6. The approach developed by the department to coordinate and deliver health services and detainee/facility services in onshore detention incorporated learnings from previous contracts and was appropriate to guide the design of the new detention services contracts. The department developed a common contractual approach aimed at achieving efficiencies and encouraging greater coordination of service delivery. Work was also undertaken by the department to determine the strategic directions that the new contracts should adopt, which included a focus on controlling the cost of services and the risk of over-servicing, and on monitoring outcomes rather than processes. The performance monitoring regime established under the contracts was designed to support the achievement of program outcomes, primarily through the use of financial incentives and abatements to drive contractor performance.

7. The deliverables expected from the health service provider were clearly defined in the contract, but there were weaknesses in the department’s approach to the assessment of risks to the achievement of contractual objectives. The contract presents a balanced mix of outcome-based expectations (such as delivering health services that are responsive to a detainee’s changing medical needs) and more prescriptive requirements (such as a focus on mental health and health screenings throughout the time detainees spend in detention). Several supporting policy documents, referenced in the contract, further define the expected health outcomes. The department’s consideration of risks to the achievement of contractual objectives was, however, primarily focused on addressing risks that arose under the previous contract. A broader analysis of the key risks to achieving the objectives of the health service contract, including those related to the new service delivery model proposed by the contractor, would have better informed the department’s design of the contract and of the performance monitoring arrangements.

8. The 17 performance measures developed by the department to monitor the provision of health services in onshore detention target important aspects of contractor performance and are aligned with the deliverables specified under the contract. However, as at March 2016, only nine of the 17 measures had an appropriate methodology in place to assess contractor performance. The remaining measures were not being effectively monitored by the department, with methodologies that were partially or not implemented. In particular, the key measure to assess the quality of primary health care was yet to be monitored 15 months after the contract was signed. The limited focus on measuring the quality of service delivery and significant delays in finalising measurement and verification activities undermines the assurance that the department obtains in relation to the achievement of contractual objectives.

Monitoring delivery of health services

9. Notwithstanding the weaknesses in the performance measurement framework established under the contract, the department has been applying the risk ratings, incentives and abatements established under the contract to drive service delivery and continuous improvement. The application of the penalty and incentive regime under the new contract has resulted in the contractor being abated over $300 000 in the first six months of operation (approximately two per cent of the contractor service fee value).

10. There are aspects of the delivery of health services in detention where existing monitoring arrangements do not provide a sufficient level of assurance to the department that services are being delivered as intended. These aspects relate most notably to community detention, mental health care, medication management and timely and clinically appropriate access to health services. Specifically, performance information was either not collected, or did not target those areas of greatest risk.

11. The department’s arrangements to support health services in detention are primarily focused on the monitoring of, and response to, issues as they occur. There is insufficient analysis of the information that the department collects, for instance in relation to incident reports and complaints, to inform a more proactive management of issues. The management of key administrative processes that support the delivery of health services and the contractual partnership with the provider should also be more timely. In particular, the finalisation of the policy and procedures manual and the delivery of facility acceptance certificates remained outstanding as at March 2016—12 months after they were scheduled for completion. The department has recognised that there is scope to improve its management of clinical issues relating to the delivery of health services in onshore detention. A centralised health structure, including clinically trained staff, has been established within the department to improve clinical oversight of the health service delivery.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 3.39 |

That the Department of Immigration and Border Protection strengthen its performance monitoring framework and monitoring practices, based on an assessment of the risks to the effective delivery of health services in onshore detention. Department of Immigration and Border Protection response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.46 |

That the Department of Immigration and Border Protection analyses health service delivery related complaint and incident reports data and uses this information to inform management and operational decision-making. Department of Immigration and Border Protection response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

12. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

The Department recognises and appreciates the efforts of the Australian National Audit Office staff who conducted the audit. This audit provides timely assurance over our administration of health services in onshore immigration detention.

The Department agrees with the recommendations of the report and has work underway to continue to improve our administration of these services.

13. International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) was provided with an extract of the proposed report. IHMS’s full response is at Appendix 1.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Immigration detention is a key element of Australia’s migration system. Under the Migration Act 1958 (the Act), a person who is not an Australian citizen and does not hold a valid visa is an unlawful non-citizen. The Act requires unlawful non-citizens to be detained until they are removed from Australia, granted a visa or removed to a regional processing country.

1.2 The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) administers the Act and the Government’s policy in relation to immigration detention, including the administration of a network of onshore immigration detention centres. Following the integration of DIBP and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service from 1 July 2015, the Australian Border Force (ABF) is now responsible for the department’s operational functions, including visa compliance, detention, removals and support for regional processing arrangements. The department’s administration of immigration detention is delivered under Program 1.3–Onshore Compliance and Detention and Program 1.4–Illegal Maritime Arrival Offshore Management, which collectively have estimated expenses of $2.6 billion in 2016–17.2

1.3 Detention occurs in held facilities and community detention. Immigration detention in Australia is collectively known as ‘onshore’ detention, and is administered by the department’s Detention Services Group. The delivery of services in offshore detention centres (at Regional Processing Centres in the Republic of Nauru and in Manus Province, Papua New Guinea) is also administered by the Detention Services Group, but under separate contracts to onshore detention. The examination of the delivery of services in the offshore detention system was not within the scope of this audit.3

Onshore detention

1.4 A person can be an unlawful non-citizen due to:

- arriving in Australia without a valid visa—including Illegal Maritime Arrivals, illegal airport or seaport arrivals, and illegal foreign fishers4;

- overstaying a visa—for example, overstaying a tourist or student visa, or being identified and detained as part of an Australian Border Force compliance operation; or

- having a visa cancelled—including those visas cancelled for failure to meet the Act’s character test. These detainees are commonly known as ‘501s’, a reference to the provision of the Act that empowers the cancellation of a visa.

1.5 The total onshore detainee population reduced significantly over the period from July 2014 to May 2016—from 6730 to 2228 detainees. As at 31 May 2016, there were 1570 detainees in held detention and 658 in community detention.

1.6 Over the same period, the profile of the onshore population in detention changed substantially, with the representation of Illegal Maritime Arrivals falling from 91 per cent (6093 detainees) to 53 per cent (1171 detainees), and detainees held under the 501 character provision increasing from two per cent (106 detainees) to 26 per cent (578 detainees).5 The population of detainees in onshore detention by detainee category (since July 2014) is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Detainee numbers by category in onshore held detention, July 2014 to May 2016

Note: The ‘Others’ category includes visa overstayers, illegal foreign fishers, non-immigration cleared air and sea arrivals, stowaways and ship deserters.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental reports.

1.7 With the exception of Christmas Island detention centre (located in the Indian Ocean 2600 kilometres north-west of Perth) and Yongah Hill detention centre (located 100 kilometres east of Perth), all detention facilities are located in capital cities. Figure 1.2 shows the locations of Australian detention facilities.

Figure 1.2: Immigration detention facilities, May 2016

Note 1: The number of detainees as at 31 May 2016 is indicated between brackets.

Note 2: Immigration detention centres provide accommodation for medium and high risk detainees. Immigration residential housing provides a more domestic detention environment where detainees are able to cook their own food and control many aspects of their household. Immigration transit accommodation provides hostel-style accommodation that includes food services as well as self-catering for snacks. Alternative places of detention are used for minimum risk detainees, in particular families, children and detainees in need of medical treatment.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Health service delivery in immigration detention

1.8 The department has a duty of care to prevent any reasonably foreseeable harm to detainees6 and is responsible for providing a range of services to detainees, including:

- general services, such as meals, education, recreation and religious activities. These services are delivered by the contracted provider of detainee and facility services7;

- care arrangements for unaccompanied minors—delivered by the Australian Red Cross and the contracted provider of detention services; and

- health care.

1.9 Health care services—to detainees located in both held and community detention—are delivered and facilitated by International Health and Medical Services (IHMS), a subsidiary of International SOS.8 IHMS has delivered health services in immigration detention under previous contracts since 2004, with the department and IHMS entering into the most recent contract on 11 December 2014. IHMS was selected to deliver health care services in held and community detention following a tender process that commenced in April 2014. The current contract is valued at $438 million over the five-year contract period from 11 December 2014 to 10 December 2019. The contract includes options to extend the term of the contract to 2023.

1.10 The manner in which health care services are delivered in detention under the current contractual arrangements is outlined below.

|

Box 1: The delivery of health services in onshore immigration detention |

|

Held detention Primary health care, including nurse and general practitioner consultations, is provided at clinics located within the detention facilities. Most detainees receive prescribed medication at set medication distribution times. Mental health, dental and optical consultations are also to be provided within detention facilities. Access to external specialists, hospitals and other allied health services, is facilitated by IHMS referral arrangements. Detainee access to health services in facilities is structured according to set procedures. Detainees are required to submit a written request to see a nurse or doctor. Consultation hours are generally from 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday. Outside of these hours, IHMS operates a telephone nursing service that detention centre officers can access on a detainee’s behalf. Emergency services attend detention facilities outside consultation hours when necessary. Community detention Detainees living in the community are assigned a medical practice and pharmacy in their local area by IHMS. They are required to arrange their own appointments. IHMS operates a cashless health care card system for community detainees to obtain medical services and medication. IHMS also manages referrals to secondary and tertiary health care providers. |

Audit approach

1.11 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s administration of health services in onshore immigration detention.

1.12 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Was a robust contract in place to support the effective and efficient delivery of health services?

- Were effective arrangements established to monitor health service provision and manage the contractor’s performance?

- Was health service delivery and contractor performance appropriately monitored?

1.13 The scope of the audit included an examination of the provision of health services in held detention facilities in Australia, as well as services made available under the community detention program. Given the relatively early stage of implementation of the new contract, the ANAO’s examination was necessarily limited to reviewing establishment activity. The audit did not examine the procurement process for the delivery of health services. Further, the audit did not include an examination of the delivery of health care services in Regional Processing Centres, as these services are delivered under separate contractual arrangements. Where offshore detainees are brought to Australia for a temporary purpose, the administration of health services to these detainees whilst in Australia was examined as part of the audit.

1.14 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed relevant department and IHMS files and documentation, including policies and procedures, correspondence, performance reports and complaints;

- collected and analysed administrative data relating to the delivery of health services;

- visited a selection of detention facilities;

- interviewed key departmental and IHMS personnel and key external stakeholders; and

- interviewed detainees in held and community detention.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $567 000.

2. Developing the contractual framework

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the processes established by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection to develop the contract for the provision of health services to detainees subject to onshore detention.

Conclusion

The contract for the delivery of health services in onshore detention was developed by the department, based on a strategic analysis of shortcomings that had arisen under earlier contracts. The contract contains mechanisms to control the risk of over-servicing and uncontrolled cost escalation, clearly defined deliverables, and a high level performance monitoring framework for onshore immigration detention contracts.

When designing the performance framework to govern the delivery of health services, the department focused on addressing the key risks that were realised under the former contract, primarily the risk of uncontrolled cost escalation. A broader analysis of the key risks to achieving the objectives of the health service contract, including those related to the new service delivery model proposed by the contractor, would have better informed the department’s design of the contract and of the performance monitoring arrangements.

Did the department develop an appropriate approach to coordinate and deliver onshore detention services?

The approach developed by the department to coordinate and deliver health services and detainee/facility services in onshore detention incorporated learnings from previous contracts and was appropriate to guide the design of the new detention services contracts. The department developed a common contractual approach aimed at achieving efficiencies and encouraging greater coordination of service delivery. Work was also undertaken by the department to determine the strategic directions that the new contracts should adopt, which included a focus on controlling the cost of services and the risk of over-servicing, and on monitoring outcomes rather than processes. The performance monitoring regime established under the contracts was designed to support the achievement of program outcomes, primarily through the use of financial incentives and abatements to drive contractor performance.

2.1 As outlined earlier, International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) has delivered health services in immigration detention since 2004. Over the course of the previous contract (2009–14), a range of changes occurred in the immigration environment, in particular the rapid growth in the number of people in detention and consequent increase in the number of detention facilities. These changes required health services to be adapted and scaled up or down at very short notice. The contract, assessed by the department as prescriptive and lacking flexibility, did not adequately allow for these necessary adjustments. The resulting situation was one where: services delivered did not always match contract specifications; variations to the contracts were formalised sometime after the changes had been implemented; and the department incurred significant additional costs not envisioned at the time that the original contract was endorsed. Performance monitoring was also assessed by the department as being ineffective (for instance, the system of incentives and abatements was not implemented until the final 11 months of the contract period).

2.2 In December 2013, when planning for the re-tendering of the health service contract, the Government indicated, through a letter from the Prime Minister to the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, its expectation that the total costs and the cost per detainee would be lower in the new contract. In this context, the department developed the following strategic directions to guide the formation of new contracts for health services and for facilities and detainee services:

- an alignment between the two contracts—aimed at better utilising the department’s corporate knowledge, identifying internal process efficiencies, and fostering productive relationships between all service providers;

- a focus on fixed pricing—the new contracts required the service provider to determine a fixed fee to cover all services and activities necessary to meet the health care needs of detainees. Any additional service requests would only be used in exceptional circumstances. This approach was aimed at reducing the risk of ‘over-servicing’;

- a risk-based performance management framework—focused on service delivery and risk management rather than contract compliance; and

- a collaborative approach between service providers and the department—where the department would share its risk by: focusing on outcomes, not processes; understanding commercial complexities; and building mutual trust through sound governance.

2.3 The department’s approach to the delivery of health services and detainee and facility services in onshore detention was also informed by the department’s Risk Management Framework, and by two departmental publications called ‘Lessons Learnt’ relating to better practice in procurement (dated August 2012) and in contract management (dated February 2013). A Joint Service Delivery Assurance Framework was also developed to underpin the new detention services contracts (discussed later in Paragraph 2.5).

2.4 Guided by the identified strategic directions, the department developed the contracts for both service providers (health services and detainee and facility services) during the course of 2014. The contracts included provisions aimed at protecting the interests of the Commonwealth and also offering protections to the service providers, including:

- transition in and out arrangements, which outlined the activities required to occur during the first and last six months of the contract. These provisions were designed to prevent any reduction in service delivery standards or continuity of care for detainees;

- payment arrangements conditional on the provision by the providers of correct and detailed invoices, adjusted monthly to reflect the performance of the providers;

- mechanisms to drive efficiency, including: financial abatements and action plans in the event of performance failures; incentives; and innovation bonuses9 (aimed at driving continuous improvement, innovation and cost savings for the department);

- an efficiency dividend of 2.25 per cent and a fixed premium of 0.75 per cent, reducing the health service fee by three per cent annually;

- requirements for program management and administration services, which were designed to support the effective delivery of services;

- a provision to develop a governance framework outlining the respective roles and responsibilities, which was designed to provide an agreed structure for communication and knowledge sharing on issues, policies and decisions at key levels10; and

- dispute resolution mechanisms, including a provision to refer any dispute that remained unresolved after several levels of escalation to an agreed expert.

Establishment of a performance management regime

2.5 To support the management and assessment of the performance of the service providers, the development of a performance management regime was a key aspect of contract development. The development of a Joint Service Delivery Assurance Framework, which informed the design of the regime, was commenced by the department in 2013. The key objectives of the framework were:

- a balanced approach to performance management, using both incentives and abatements to drive performance and assure program outcomes;

- a reduction in the administrative burden for both the department and service providers;

- the fulfilment of the department’s responsibilities to government by aligning service delivery with the relevant Portfolio Budget Statements outcome; and

- assurance that the needs of detainees were met.

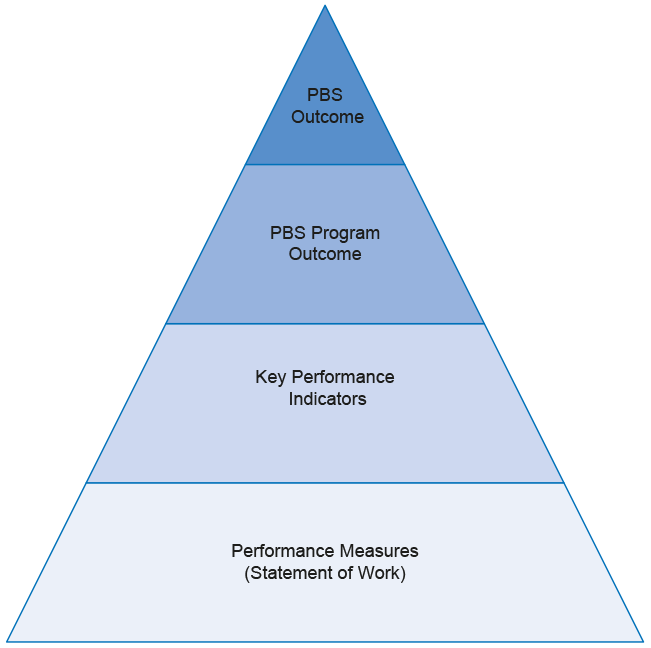

2.6 The contracts for the delivery of services in detention included a performance management model that provided a clear alignment between the department’s program objective at the highest level (as stated in the 2013–14 Portfolio Budget Statements), the key performance indicators (KPIs); and the performance measures. The model is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Performance management model for onshore immigration detention services

Source: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Request for tender for the provision of onshore immigration detention services, RFT 04/14, Performance management framework, p. 2.

2.7 The KPIs that were developed for inclusion in the two contracts (health services and facilities and detainee services) were designed to align with the department’s key deliverables and to cover the full scope of services to be delivered at each detention facility across all service providers (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: KPIs for the contracts to deliver health services, and detainee and facility services in onshore immigration detention

|

Indicator |

Description |

|

KPI 1: Welfare |

The cultural, spiritual, social, mental, physical and emotional wellbeing of each detainee, and the broader detainee cohort, is maintained and positively influenced by the immigration detention service provider involvement where practical. |

|

KPI 2: Health, Medical and Counselling |

Detainees are given timely access to health, medical and counselling services that are provided to accepted professional and community standards. |

|

KPI 3: Security |

The safety and good order of the facility, its people and its operations are maintained while ensuring the integrity of immigration detention at all times. |

|

KPI 4: Facilities and Assets Management |

The facility is made a safe, clean, hygienic and presentable environment by proactive work undertaken by the immigration detention service provider in the management, cleaning and maintenance of assets and facility amenities. |

|

KPI 5: Transport and Escort (including Transfer and Removal) |

The operation of each facility and the broader immigration detention network (including community detention) are supported by effective, efficient and economical transport arrangements and appropriate escort services. |

|

KPI 6: Administration, Support and Logistics |

The efficient, effective and economical operation of each facility and the broader immigration detention network is maintained and supported through well designed administrative process, support staff and logistical arrangements. |

|

KPI 7: Relationships and Collaboration |

The immigration detention service provider takes a collaborative and integrated approach to the provision of services, will be effective in managing complex stakeholder and governance issues, and builds long term relationships with the department and other service providers. The immigration detention service provider drives continuous improvements in service delivery for the benefit of detainees and the department. |

Source: Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

2.8 Under the established Joint Service Delivery Assurance Framework, the contractor was responsible for reporting performance against measures established under the contract in accordance with established reporting deadlines. The department’s role was to review the accuracy of the provider’s reports and conduct a limited number of additional reviews and audits on targeted activities (the operation of the monitoring framework relating to health service delivery is examined later in this chapter).

2.9 On the basis of the approach established, the department completed the procurement and contracting process for the delivery of detainee and facility services in August 2014.11 A similar approach was subsequently adopted by the department to select the contractor for the delivery of health services. An important part of the work required to finalise the health service contract, examined later in this chapter, involved tailoring the core contractual framework to the specific objectives and requirements of health service delivery, including by:

- establishing a statement of the contract deliverables (the Statement of Work); and

- developing performance measures, against which the performance of the contractor would be assessed over the life of the contract.

Did the health service contract establish clear deliverables informed by an assessment of the risks to achieving contractual objectives?

The deliverables expected from the health service provider were clearly defined in the contract, but there were weaknesses in the department’s approach to the assessment of risks to the achievement of contractual objectives. The contract presents a balanced mix of outcome-based expectations (such as delivering health services that are responsive to a detainee’s changing medical needs) and more prescriptive requirements (such as a focus on mental health and health screenings throughout the time detainees spend in detention). Several supporting policy documents, referenced in the contract, further define the expected health outcomes. The department’s consideration of risks to the achievement of contractual objectives was, however, primarily focused on addressing risks that arose under the previous contract. A broader analysis of the key risks to achieving the objectives of the health service contract, including those related to the new service delivery model proposed by the contractor, would have better informed the department’s design of the contract and of the performance monitoring arrangements.

Defining contractual deliverables

2.10 With the endorsement of the current contract, the department has moved away from a prescriptive description of expected deliverables that focused on inputs and processes, towards framing the deliverables in terms of results and outcomes. A focus on results and outcomes better allows for operational flexibility and innovation.12 Accordingly, the key focus of the contractual objectives is the provision of a standard of care broadly comparable with that available within the Australian community, as outlined in Box 2.

|

Box 2: Objectives of the health service contract |

|

Source: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Immigration detention health services contract, Clause 10.1, executed 10 December 2014.

2.11 In addition to stating the broad objectives underpinning the delivery of health services, the contract includes a detailed Statement of Work that further defines the deliverables expected from the contractor. In particular, it identifies certain health conditions that require specific attention. Given the particular and well-documented risks of mental health conditions arising in the detention environment, the contract requires the provider to ‘maintain a health care model which is capable of providing appropriate mental health clinical care to detainees’.13 The contract also specifies the range of services required that are unique to the detention context (mostly, vaccinations; health screenings; and health assessment at entry into, exit from and movement within the detention network, aimed at identifying and managing public and mental health issues).

2.12 The contract is supported by several companion policy documents that aim to define health care in detention, including:

- Detention Services Manual, specifically Chapter 6: Detention Health;

- Standards for Health Services in Australian Immigration Detention Centres, developed by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners in 200714; and

- Detention Health Framework, A policy framework for health care for people in immigration detention, developed by the then Department of Immigration and Citizenship in 2007.

Assessing risk

2.13 The department was attuned to those risks that were realised under the previous contract, primarily uncontrolled cost escalation. As discussed earlier, a key characteristic of the new contract was the adoption of a fixed-pricing model. Under this model, the service provider is to be paid a fixed fee that is to cover the services and activities necessary to meet the objectives of the contract. More precisely, the amount payable by the department for the provision of health services as defined in the contract consists of fixed fees and pass-through costs (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Contract pricing model

|

Element |

Description |

|

Fixed-fees |

Consisting of:

|

|

Pass-through costs |

Including items such as:

|

Source: Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Immigration Detention Health Services Contract, Schedule 6 Health services fee.

2.14 The department considered that the advantage of this pricing model was that it provides additional protections against the provider delivering services that are not necessary (risk of over-servicing). Under the fixed-price model, the contractor would not be paid for doing so. The department expects to realise considerable savings through the use of this model, as it shares with the provider the risk of escalating and uncontrolled costs. The contractor has estimated that the model will deliver savings of around 30 per cent over the life of the contract.

2.15 The department did not undertake a structured assessment of the risks to the achievement of the objectives set for the new health service delivery contract, in particular those relating to the model proposed to reduce the overall cost of the contract. While the management of cost was a clear focus, other risks, for example the risk of under-servicing by the contractor—that is where the provider prioritises commercial profitability over the delivery of services of adequate quantity and quality—received less focus. This was despite issues relating to under-servicing arising under the previous contract. In September 2015, the department concurrently conducted an internal review and commissioned a consulting firm to conduct a separate review into alleged improper conduct by the contractor relating to the provision of health services in immigration detention under the previous contract. It also focused on the inadequacy of the department’s contract management practices.15 Based on the findings of these reviews, the department concluded that some allegations were partially verified. In particular, it found that the allegation that the contractor at the time (IHMS) was ‘failing to deliver health services to an accepted standard, which could impact on the health outcomes of detainees’, was partially verified. The department concluded that:

The level of ‘comfort’ around the provision of healthcare, or what constitutes ‘appropriate’ are ambiguous terms. From both a reputational risk perspective, and to satisfy its duty of care, the department should be assured that the provision of care, including adequate vaccinations rates are in line with Australian community expectations. It is recommended that [going forward] the Detention Health Services Branch include rigorous compliance monitoring as part of the broader performance management of the Immigration Detention Health Services Contract.16

2.16 Given the issues that arose in relation to the provision of care under the previous contract (due in part to the lack of sufficient rigour in compliance monitoring practices by the department) the appropriateness of the proposed service delivery model should have received more attention during the design of the pricing model, performance measures and compliance arrangements. This issue will require careful regular and ongoing monitoring and management by the department over the life of the current contract.

Has the department established appropriate arrangements to monitor progress against established performance measures?

The 17 performance measures developed by the department to monitor the provision of health services in onshore detention target important aspects of contractor performance and are aligned with the deliverables specified under the contract. However, as at March 2016, only nine of the 17 measures had an appropriate methodology in place to assess contractor performance. The remaining measures were not being effectively monitored by the department, with methodologies that were partially or not implemented. In particular, the key measure to assess the quality of primary health care was yet to be monitored 15 months after the contract was signed. The limited focus on measuring the quality of service delivery and significant delays in finalising measurement and verification activities undermines the assurance that the department obtains in relation to the achievement of contractual objectives.

2.17 The initial seven high level KPIs developed by the department were designed to cover both health services, and detainee and facility services, and address the general goals of service delivery in detention more broadly (outlined earlier in Table 2.1). One of these KPIs—KPI 2: Health, Medical and Counselling—is directly relevant to the key objective of the health service delivery contract. The department subsequently developed 17 specific performance measures in late 2014 to be used to assess the performance of the contractor in achieving the department’s expected health objectives.

2.18 The development of specific performance measures by the department was important, as these were to be used to frame the data that was to be collected and used to monitor performance over the life of the health service contract. They were also to provide the basis for determining abatements and incentives, and authorising payments. To effectively underpin oversight of contractor performance, these measures should target the key risks to meeting the outcomes of the contract, and effectively support the timely and accurate monitoring of the quality of service delivery.

Appropriateness of performance measures

2.19 The ANAO reviewed the 17 performance measures and examined the underpinning methodologies developed by the department to assess progress against each measure (see Table 2.3). The measures targeted important aspects of contractor performance and were aligned with the deliverables specified under the contract. The ANAO’s analysis indicated that, by March 2016 (15 months after the contract commenced), the department’s progress in bedding down a robust performance monitoring framework has been limited. In addition to delayed implementation for a number of the measures, the measures developed by the department were not balanced. Specifically, the measures were heavily weighted towards administrative aspects of service delivery (16 of 17 measures)—with a strong focus on timeliness.

Table 2.3: Analysis of the health service contract’s performance measures, as at March 2016

|

Measure |

ANAO analysis |

Status |

|

1A. Timely provision of health care |

Timely provision of health care is an important element of quality health care. The methodology was established to measure one element of timeliness: whether an appointment was provided within the timeframe that the triage nurse decided was appropriate. As at March 2016, performance results were reported by the contractor and a sample of transactions were verified by the department. |

The measure is established |

|

1B. Coverage availability |

Monitoring contractor presence on site to deliver services is an important indicator of health care delivery. The measure monitors the minimum clinical presence, for which the contractor is paid a fixed fee (one doctor and one nurse, present from 9 am to 5 pm, Monday to Friday). As at March 2016, performance results were reported by the contractor and verified by departmental staff through on-site observations. |

The measure is established |

|

2A. Maintenance of health care records |

The maintenance of health care records is an important requirement on the contractor, as keeping up-to-date and accurate patient records is required under the RACGP Standards, which are referenced in the contract. The methodology established to inform performance against this measure assesses a sample of health care records against the RACGP Standards. As at March 2016, performance results were reported by the contractor only. Departmental verification activities, scheduled to start from July 2015, had not commenced. |

The measure is partially established |

|

2B. Quality integrated primary health care(a) |

This measure was designed to assess a critical focus of quality health care—whether quality care is provided in accordance with industry practice. As at March 2016, the measure was not monitored. Its assessment relied on a tool (the Departmental Medical Audit Tool) that was being developed by the department (see paragraph 2.22). |

The measure is under development |

|

3. Timeliness and completeness of health induction assessments(b) |

A measure focused on induction assessments is appropriate given the importance of assessing the health status of detainees entering or moving within the detention network as soon as possible. The methodology established for this measure is designed to assess whether health inductions are conducted in a timely manner and whether the key components of the induction are completed, based on contractor’s self-reporting and departmental sample verification. As at March 2016, reporting by the contractor had not commenced, because the department had not consistently followed the agreed protocol to request a health induction assessment. The department had reviewed a sample of assessments for timeliness, not completeness. |

The measure is partially established |

|

4. Timeliness of mental health screening |

The measure is relevant, given the prevalence of mental health issues in detention. The methodology established to assess performance against this measure considers the timeliness of the initial mental health screening consultation at 6, 12 and 18 months spent in detention. As at March 2016, performance was reported by the contractor and verified, on a sample basis, by the department. |

The measure is established |

|

5A. Timely identification and comprehensive treatment of detainees with active tuberculosis |

A measure focused on the treatment of tuberculosis is appropriate given the risk to the individual and the community of undetected active tuberculosis. The methodology is designed to assess whether detainees presenting clinical indications of tuberculosis have been identified and placed under the relevant care plan within 24 hours. As at March 2016, the contractor reported on the timely placement of detainees on a care plan. The contractor also provided a weekly report to the department, containing details of identified tuberculosis cases and treatments. The timely identification of cases relies on the Departmental Medical Audit Tool, which was not operational. |

The measure is partially established |

|

5B. Timely identification and comprehensive treatment of detainees with serious communicable diseases (other than active tuberculosis)(c) |

As with tuberculosis, the measure is appropriate given the risk to the individual and the community of undetected serious communicable diseases. The methodology is designed to assess whether detainees presenting clinical indications of serious communicable diseases (other than tuberculosis) have been identified and placed under the relevant care plan within 72 hours. It also aims to assess whether, in case of confirmed cases, the contractor has taken appropriate and timely action. As at March 2016, the contractor reported on the timely placement of detainees on a relevant care plan. The other aspects of the measures rely on the Departmental Medical Audit Tool, which was not operational. |

The measure is partially established |

|

6. Timely conduct of vaccination program |

A measure focused on vaccination is appropriate and in line with the Australian National Immunisation Program. The methodology assesses that detainees who agree to be immunised are vaccinated in accordance with the Australian Immunisation Handbook schedule. As at March 2016, performance was reported by the contractor. Planned departmental verifications, using the Departmental Medical Audit Tool, had not commenced. |

The measure is partially established |

|

7. Timely management and maintenance of detainees with chronic diseases(d) |

A measure focused on chronic diseases is appropriate given that cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and asthma are the three most prevalent chronic diseases in detention.(e) The methodology assesses that detainees with these chronic diseases are placed on the relevant care plan in a timely manner, and that the plans are appropriately maintained. As at March 2016, performance was reported by the contractor. Planned departmental verifications, using the Departmental Medical Audit Tool, had not commenced. |

The measure is partially established |

|

8. Effective provision of pharmaceuticals |

Ensuring that detainees are provided with clinically appropriate medication is a key aspect of quality health care. The methodology established for this measure assesses certain aspects of medication administration: whether a risk assessment was conducted for detainees on self-administered medication; and whether errors have occurred in the administration of medication, based on the submission of an incident report to the department. As at March 2016, the contractor reported on the timely provision of risk assessments, and on the number of incident reports related to medication administration. The department verified the timeliness of a sample of the risk assessments. The department also reviews incident reports. |

The measure is established |

|

9. Timely conduct of fitness to travel assessments(f) |

The measure is appropriate as fitness to travel assessments are a requirement for detainees travelling by air. Issues relating to the timely conduct of the assessments also have the potential to impact on detainees and on the department’s operational activities. The methodology established for this measure is designed to monitor whether fitness to travel assessments are conducted within 48 hours of the contractor receiving a request from the department. As at March 2016, contractor performance results were incomplete as the department had not consistently followed the agreed protocol to request an assessment. |

The measure is partially established |

|

10. Maintenance of clinician records |

A measure focused on record-keeping is appropriate as it informs the monitoring of three key areas of clinical staff accreditation: a police check and Working with Children Check (where applicable); Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency professional registration; and accreditation in basic or advanced life support. As at March 2016, the methodology established for this measure combined self-reporting with sample verification by the department. The department conducted a sample-based review of the contractor’s compliance in November 2015. |

The measure is established |

|

11. Timely completion of incident reports |

This measure monitors whether the department is informed of all critical, major and minor incidents in a timely manner. As at March 2016, compliance with timeliness requirements was reported by the contractor and reviewed, on a sample basis, by the department. The department also reviewed a sample of incident reports for completeness. |

The measure is established |

|

12. Complaints Management System |

The monitoring of complaints provides important information on the delivery of health services. As at March 2016, compliance with timeliness requirements was reported by the contractor and reviewed, on a sample basis, by the department. The department also reviewed a sample of complaints to assess the completeness of responses. |

The measure is established |

|

13. Timely and accurate reporting |

A measure focused on reporting is appropriate as it underpins effective contract management. As at March 2016, the methodology established for this measure was designed to monitor whether the contractor had provided accurate reports within agreed timeframes. The department was monitoring the timeliness and accuracy of contractor reporting. |

The measure is established |

|

14. Preventative health services |

A measure focused on preventative health services is appropriate as effective delivery of these services underpins the efficient delivery of health care. As at March 2016, the methodology established for this measure was designed to monitor the health prevention activity sessions delivered under an approved monthly plan (with a minimum attendance of one detainee). The department was appropriately monitoring the delivery of relevant sessions. |

The measure is established |

Note a: Integrated primary health care includes nurse and general practitioner consultations, dental and optical services, medication supply and administration, and referral to allied health and specialist services as required.

Note b: Health induction assessments occur when a person enters detention, and are designed to identify any health conditions that could pose a threat to public health. They also establish whether a detainee has any health conditions, including mental health conditions, which require treatment or the development of an ongoing health treatment plan.

Note c: Other serious communicable diseases include hepatitis B and C, HIV and syphilis.

Note d: Chronic diseases included in the measure are asthma, diabetes and hypertension.

Note e: IHMS, Health data set April-June 2015, p.22.

Note f: Fitness to travel assessments must occur prior to a detainee traveling, including when being removed from Australia. The purpose of the assessment is to certify that a person is fit to be moved from their current place of detention, including, if applicable, whether they meet airline criteria for travel.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

2.20 As indicated by the ANAO’s analysis, of the 17 measures developed by the department for inclusion in the contract, nine had appropriate methodologies established to inform an assessment of performance as at March 2016. Specifically, the measures were relevant, the assessment methodology was aligned to the intent of the measure, and the monitoring arrangements were operational. The department’s approach to monitoring performance against the remaining measures was not sufficiently robust. The planned methodologies were partially or not implemented, because the department: had not finalised the tools required to assess the measures; or had not consistently followed the protocol agreed upon with the contractor to request the health services. In particular, the quality of health service delivery was not being effectively monitored. Further, for a number of measures, the planned activities to verify the contractor’s reported performance had yet to be implemented. As a consequence, the department is not well placed to effectively monitor the delivery of health services.

Assessing quality

2.21 The contract includes one measure that is directed at assessing the quality of service delivery—Measure 2B: Quality integrated primary health care. The department plans to audit the contractor’s performance against this measure using departmental medical officers to examine a sample of detainee health care records (five per cent of all clinical records relating to a specific health event) and make clinically-based judgements as to the quality and appropriateness of the health care provided. However, the tool being developed by the department to undertake these audits—the Departmental Medical Audit Tool—was yet to be finalised by the department as at March 2016.

2.22 The draft version of the tool, which was reviewed by the ANAO, comprised:

- a large spreadsheet containing 25 modules, such as ‘GP consultation’, ‘triage’ or ‘women’s health’. Each module included approximately 10 criteria, which totalled to over 250 criteria to be assessed;

- an approach to reviewing the quality of health care based on episodic health events rather than continuity of patient care. For example, the tool was designed to select a patient to review the quality of nurse consultations received by that patient in isolation from previous or latter medical interventions to treat the specific and any related conditions;

- an approach centred on the review of the electronic heath care records, with no face-to-face discussion with the contractor’s clinicians; and

- a level of duplication in the information verified (for instance, the detainee identifiers are verified for each module).

2.23 The delayed finalisation of the auditing tool has compromised the department’s ability to assess the quality of health care delivery and undermined its ability to determine whether contractual obligations are being fully met.

Use of self-reporting

2.24 The performance measurement framework is primarily based on contractor self-reporting, where the contractor reports its performance against the measures in a Monthly Performance Report (using a spreadsheet developed by the contractor and approved by the department). When balanced with risk-based verifications by the department, this approach is designed to support efficiencies and to place the responsibility of meeting performance expectations on the contractor.

2.25 Prior to approving the final version of the contractor’s spreadsheet in July 2015, the department conducted a limited range of validations to ensure that the wording of performance measures and of the associated methodologies was reflected accurately in the spreadsheet. The department did not validate the data capture method or the data treatment within the spreadsheet. Given the reliance that is placed on the spreadsheet, there would be merit in the department reviewing the data capture and treatment methods.

2.26 The contractor’s Monthly Performance Report is to be reviewed by the department using the following four approaches:

- the audit of supporting documentation (for instance, a sample of medical request forms are collected to verify Measure 1A: Timely provision of primary health care), observations from on-site departmental staff, and the review of incident and complaint reports;

- a program of reviews targeting specific issues, to be determined by the department;

- the proposed Departmental Medical Audit Tool (discussed earlier), which is to be applied quarterly; and

- a proposed Health Service Provider Records Review Tool (which aims to determine, on a monthly basis, whether relevant fields of the contractor’s electronic health care record system are completed accurately—this tool is designed to assess performance against Measure 2A).

2.27 Of these four approaches:

- only the first approach (audits of supporting documentation) had been operational from the commencement of the performance regime under the contract (July 2015);

- one targeted review had been conducted in November 2015 (review of clinician records); and

- both the Departmental Medical Audit Tool and the Health Service Provider Records Review Tool remained under development as at March 2016.17

2.28 There is considerable scope for the department to strengthen its risk-based monitoring arrangements under the health service delivery contract. When coupled with strengthened monitoring of the quality of the health service delivery, the department will be better placed to determine the extent to which contractual objectives are being achieved.

3. Monitoring delivery of health services

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the arrangements established by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection to gain assurance that health services in onshore immigration detention are being delivered in accordance with the objectives of the contract.

Conclusion

The performance monitoring framework established under the new health service contract has been operating since July 2015, including the application of financial penalties for failures to meet performance measures and incentives for exceeding performance expectations in accordance with contractual requirements. There are, however, shortcomings in monitoring and oversight arrangements, including:

- the lack of effective monitoring of key identified health service delivery risks (such as services to detainees with mental health conditions); and

- the limited analysis of operational data, which has restricted the department’s ability to identify emerging trends and respond to issues at a systemic level.

The department has recognised that there is scope to improve its oversight of health service delivery in onshore detention settings. The recent establishment of a health-focused division including clinically trained staff, as well as proposed activities to improve the governance framework for health service delivery, better position the department to provide effective contractual oversight.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations designed to increase the level of assurance that the department obtains in relation to the delivery of health services in accordance with the objectives of the contract.

Has the department established effective performance management practices?

Notwithstanding the weaknesses in the performance measurement framework established under the contract, the department has been applying the risk ratings, incentives and abatements established under the contract to drive service delivery and continuous improvement. The application of the penalty and incentive regime under the new contract has resulted in the contractor being abated over $300 000 in the first six months of operation (approximately two per cent of the contractor service fee value).

Performance measurement activity

3.1 The department’s primary means of assessing the contractor’s performance is against the 17 performance measures established in the contract, notwithstanding the weaknesses outlined in Chapter 2. Each measure is assigned a risk rating based on the likelihood and consequences of a performance failure. To manage poor performance, failure against a performance measure in a given month results in the accumulation of abatement points, the number of which is dependent on the scale of the failure and the risk rating assigned to the performance measure. The number of abatement points accumulated in a given month results in a deduction in the performance fee payable to the contractor in that month, where one abatement point equals approximately $1.18

3.2 To encourage high performance, incentive credit points are also awarded where monthly performance against a particular performance measure exceeds the contract’s benchmark expectations. Incentive credit points offset abatement points and reduce the amount that the contractor would otherwise be penalised. For example, where the contractor’s performance in a month results in 1000 abatement points and 400 incentive credit points, the abatement amount would be approximately $600.

3.3 The performance measurement system also comprises additional mechanisms to assist the department to evaluate the contractor’s performance against contractual obligations (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Key elements of the performance measurement system

|

Mechanism |

Function |

|

Action plans |

In the event of a performance failure, the contractor is required to develop and implement an action plan that must: identify the causes of the failure; detail risk mitigation strategies; outline the remedial action to be taken; and include a timeline for implementation. |

|

Performance improvement notices |

Performance improvement notices can be issued to the contractor by the department in circumstances where there has been consistent failure of a performance measure over a six-month period and where the contractor has repeatedly failed to perform its services in a manner consistent with the KPIs. |

|

Withholding points |

Where the contract defines performance failures as low, minor or medium risk, abatement points are withheld for up to three months. The points are extinguished when the contractor delivers an action plan. The points are applied if the contractor fails to supply an action plan. |

|

Excusable performance failure |

Excusable performance failures may occur where events beyond the control of the contractor (such as unforeseen surges in detainee numbers or force majeure events) cause a performance failure. In these instances, abatement points are not to be applied. |

|

Innovation bonus |

In order to drive continuous improvement, the contractor is encouraged to implement new or changed procedures that lead to cost savings. Where such an innovation leads to a cost saving for the department, 30 per cent of the saving is to be shared with the contractor. |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

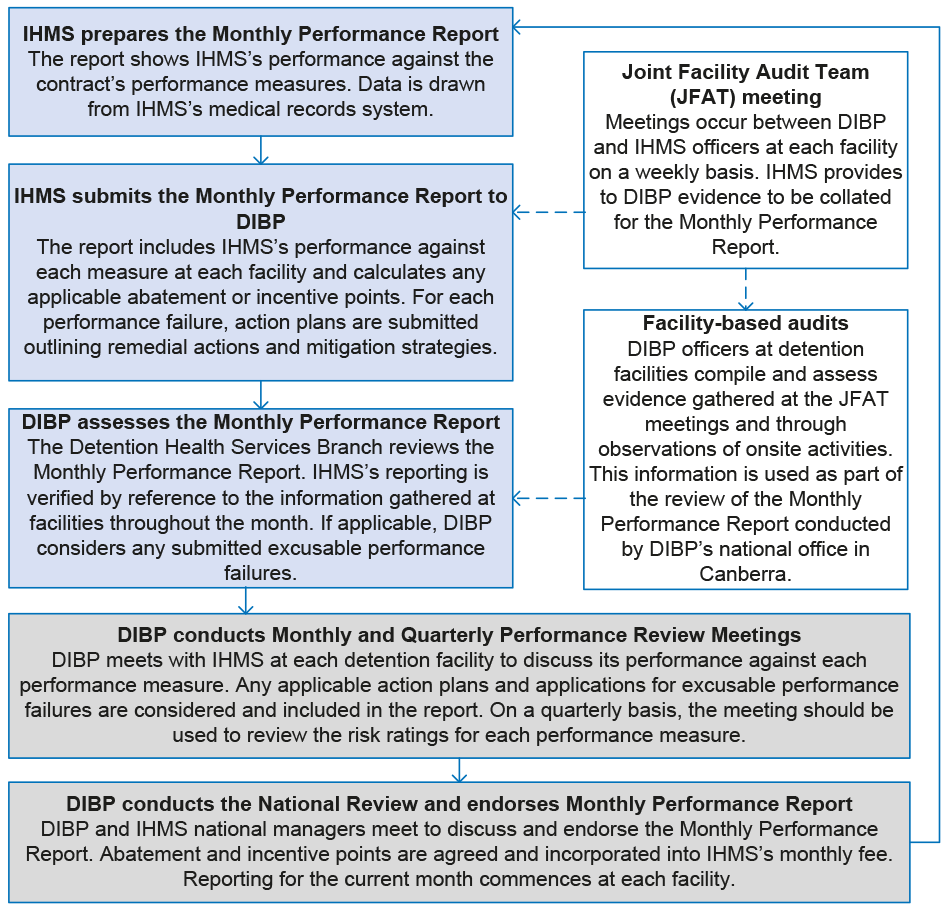

3.4 The Monthly Performance Report, together with action plans (in case of performance failures) and excusable performance failures submissions (if applicable), are to be received by the department within 10 business days of the end of each month. The department has five business days in which to raise any issues with the contractor relating to the report and request any clarifications, if needed, before endorsing the report. The endorsement of the report triggers the payment of the fixed fee. The department’s verification of Monthly Performance Reports is to be based on a series of processes, outlined in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Monthly performance reporting process

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Results after six months of operation

3.5 The monitoring under the performance measurement framework (‘business-as-usual’ operation) commenced in July 2015. In the first six operating months of the abatement and incentive regime, all but one of the reported performance measures experienced an instance of failure resulting in abated or withheld points. Table 3.2 outlines the abatement, withholding and incentive points accrued for each performance measure in the analysed period.

Table 3.2: Instances of performance failures, July to December 2015

|

Performance measure |

Abatement points accrued |

Withholding points held |

Incentive points earned |

|

|

1A |

Timely provision of health care |

3650 |

2775 |

1896 |

|

1B |

Coverage availability |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2A |

Maintenance of health care records |

1296 |

0 |

0 |

|

2B |

Quality integrated health care(a) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

3 |

Timeliness of health induction assessments(a) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

4 |

Timeliness of mental health screening |

250 |

13 900 |

9188 |

|

5A |

Identification and treatment of active tuberculosis |

50 000 |

0 |

0 |

|

5B |

Identification and treatment of serious communicable diseases (other than active tuberculosis) |

32 000 |

0 |

0 |

|

6 |

Timely conduct of vaccination program |

0 |

176 |

0 |

|

7 |

Management and maintenance of chronic disease |

1000 |

7000 |

0 |

|

8 |

Effective provision of pharmaceuticals |

4853 |

0 |

0 |

|

9 |

Timely conduct of fitness to travel assessments |

400 |

2600 |

2263 |

|

10 |

Maintenance of clinician records |

50 |

1300 |

0 |

|

11 |

Timely completion of incident reports |

183 510 |

0 |

0 |

|

12 |

Complaints management system |

575 |

4925 |

0 |

|

13 |

Timely and accurate reporting |

2625 |

0 |

0 |

|

14 |

Preventative health services |

0 |

0 |

1164 |

|

|

Total |

280 209 |

32 676 |

14 511 |

Note a: Performance Measure 2B and 3 were not operational in the period reviewed. Accordingly, the results for these measures are shown as N/A.

Source: ANAO analysis of Monthly Performance Reports.

3.6 Abatement and withholding points were applied in relation to most performance measures. Table 3.2 shows, however, that much of the accrual of abatement points is attributable to a small number of significant failures, with 265 510 of the 280 209 abatement points in the period (95 per cent) attributable to failures of measure 11 (Timely completion of incident reports) primarily, 5A (Identification and treatment of active tuberculosis) and 5B (Identification and treatment of serious communicable diseases (other than active tuberculosis). This is in part indicative of the high risk rating assigned to the measures, meaning that abatement points are applied immediately and cannot be withheld and credited back in the following month if the performance expectation is subsequently met or exceeded. Where the risk rating and abatement threshold is lower, performance failures do not necessarily result in large abatements. For example, Performance Measure 1A was failed at facilities on 15 per cent of occasions, yet improved performance in subsequent months meant that 1250 abatement points were re-credited. Good performance against this measure at some facilities (earning 1896 incentive points) resulted in further mitigation of poor performance.

3.7 To encourage a remedial response from the contractor in the event of performance failures, abatement points, offset by incentive points, result in the reduction in the fee payable in a given month. As presented in Table 3.3, between July and December 2015, the contractor incurred 149 performance failures, leading to over $300 000 in abatement (approximately two per cent of the value of the contractor service fee for the same period).

Table 3.3: Abatement values, July to December 2015

|

Month |

Performance failures |

Abatement value(a) |

|

July |

40 |

$132 521 |

|

August |

41 |

$95 245 |

|

September |

18 |

$40 597 |

|

October |

24 |

$6975 |

|

November |

12 |

$6471 |

|

December |

14 |

$26 797 |

|

Total |

149 |

$308 606 |

Note a: The abatement value and the number of abatement points do not directly equate. This occurs because the final abatement figure includes points withheld in previous months being applied to the current month, and the deduction of incentive points.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

3.8 While the financial value of abatements decreased by 80 per cent between July and December 2015, the number of individual failures in the same period did not reduce as sharply. This occurred because the abatement value attached to a performance failure is dependent on the extent of the failure; the corresponding risk rating; and whether a multiplier factor is applied.19 There is potential, therefore, for a large number of failures to produce a small abatement value, and conversely for a small number of high-risk failures to produce a large abatement value. It is appropriate to address the greatest risks by assigning to those risks the heaviest abatement. While decreasing abatement value is an indicator of an overall improvement in performance, the number of individual failures with a lower risk rating may remain at similar levels.

3.9 The contract includes a provision for the quarterly review of risk ratings, which should take into account historic performance failures, effectiveness of risk mitigation strategies (action plans) and the department’s own observations. This review process is designed to ensure that risk ratings remain appropriate and, if not, to modify the ratings to reflect the change in risk profile. As at March 2016, these reviews had not been conducted. The department advised that it is working to enhance the current risk rating process, in consultation with the contractor.

Action plans, excusable performance failures and the innovation bonus

3.10 The completion of action plans following a performance failure provides an opportunity for the contractor to identify the cause of failures and for the department to assess and endorse the proposed remedial action. In the period July to December 2015, the contractor submitted 45 action plans in response to its performance failures in that period.20 The remedial actions proposed included: further staff education; process improvements and reviews; increased monitoring of timeframes; and increased quality control from senior staff. The department approved 44 of the 45 action plans submitted, and advised the ANAO that on-site departmental officers were responsible for following up the plans’ implementation.21

3.11 Three applications for excusable performance failures were made by the contractor in the period from July to December 2015, all of which were approved by the department. The excused failures occurred at three detention facilities and related to a range of performance measures:

- an IT failure at one site (requiring all medical notes to be hand written for three days);

- a failure by another service provider (resulting in complaint acknowledgement letters not being delivered to detainees within the contractual timeframes); and

- a detainee population increase at one site (resulting in the actual number of detainees in the reporting month being 58 per cent higher than that predicted by the department, causing the failure of three performance measures).

3.12 In addition to the abatement and incentive scheme, the performance framework encourages continuous improved performance from the contractor through the availability of an innovation bonus (outlined earlier in Table 3.1). In the period from July to December 2015, the contractor did not seek an innovation bonus. As performance of the contract and the performance framework achieves greater maturity, the innovation bonus scheme has the potential to play a greater role in improving the quality and efficiency of health service delivery.

Is the department effectively monitoring whether health services are being provided in accordance with contractual requirements?

There are aspects of the delivery of health services in detention where existing monitoring arrangements do not provide a sufficient level of assurance to the department that services are being delivered as intended. These aspects relate most notably to community detention, mental health care, medication management and timely and clinically appropriate access to health services. Specifically, performance information was either not collected, or did not target those areas of greatest risk.

Monitoring health service delivery in community detention

3.13 As at May 2016, there were 658 people in community detention across Australia. Primary considerations when determining community detention placements are safety and health status. Those detainees that are considered for community detention are generally families with children, unaccompanied minors and people who have specialist health or physical needs that are difficult to meet in immigration detention facilities. Community detainees live in rented accommodation and receive an allowance for daily living costs. While detainees are not permitted to enter into paid employment, they can engage in volunteering activities. Children are able to attend school in their local area. The department engages community service organisations to support detainees with their administrative and welfare needs, including access to health care.

3.14 All health care costs of community detainees are funded by the department. Detainees access health services through medical practices located in the community. Referrals for other services must be provided through the public health system, apart from exceptions which are pre-approved by the department.

3.15 The health service contractor’s role in relation to delivery of health care to people in community detention consists primarily of:

- developing and maintaining a network of doctors, pharmacists and other health care providers that detainees must use when accessing healthcare;

- issuing health care cards that allow detainees cashless access to health services; and

- managing referrals to secondary and tertiary health care providers.

3.16 The contractor is paid a daily rate to deliver services to people in community detention, with all other costs (such as pharmaceuticals, general practice and specialist services) being passed-through to the department.

3.17 A key element in the contractor’s responsibilities to ensure continuity of care between held and community detention is the preparation of a health discharge assessment for detainees leaving a detention facility. Once an assessment has been prepared, detainees are to be provided with a ‘health discharge summary package’ that is to include a summary of the detainee’s health status (in English and, if necessary, in the detainee’s preferred language) and a 28-day supply of prescribed medication. Once in community detention, detainees are expected to take their health discharge summary to their first medical consultation. Continuity of care is also supported by the requirement for doctors in the community to provide all detainee clinical notes to the contractor. These clinical notes must be attached to the detainee’s electronic health care record that is maintained by the contractor.

3.18 The performance measures established under the contract, as outlined in Chapter 2, primarily relate to the delivery of health services in held detention. These measures are not well suited to measure the contractor’s performance in delivering health care in community settings. Performance measures monitoring the delivery of community detention health services, for example continuity of care between held and community detention, have not been developed.