Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of Smart Centres' Centrelink Telephone Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the Department of Human Services’ management of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services.

Summary

Introduction

1. In 2013–14 the Department of Human Services (Human Services) delivered $159.2 billion payments to customers and providers.1 The department delivers these payments and related services on behalf of the Australian Government through a variety of channels2 including telephone, on-line, digital applications and face-to-face through some 400 service centres located across Australia. While there has recently been strong growth in digital channels and the department is actively encouraging the use of these self-service channels, demand for telephone services remains strong. In 2013–14, the department handled 59.5 million telephone calls about Centrelink, Child Support and Medicare services.3 The majority of calls, 43.1 million annually or more than 800 000 per week, related to Centrelink services.

2. Human Services manages over 50 Centrelink-related telephony lines, each with its own ‘1800’ or ‘13’ telephone number.4 Each of the main payment types such as the aged pension and employment services has its own line, and calls are managed and distributed nationally through a virtual network. Previously referred to as call centres, the department now provides telephone services through a network of 29 Smart Centres, with some $338 million expended on Centrelink telephone services in 2013–14.

3. The department’s shift to Smart Centres began in 2012–13 and is still being implemented. Previously, telephony and processing work were undertaken separately and were arranged by payment type. Smart Centres are intended to blend telephony and processing work and reorganise work around the complexity and frequency of customer transactions rather than by payment type, so as to improve customer service and allow staff to be deployed more flexibly.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

4. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) management of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services.

5. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Human Services offers customers effective telephone services in relation to a range of quality indicators, for example, wait times and the accuracy of the information provided;

- Centrelink call services in Smart Centres are managed efficiently; and

- Human Services effectively monitors and reports on the performance of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services.

6. The audit scope did not include an examination of Smart Centres’ processing services other than the processing that is done as part of the telephone service; or Smart Centres’ Medicare and Child Support telephone services.

Overall conclusion

7. Telephone services provided by the Department of Human Services (Human Services) through Smart Centres5 are an integral part of the Australian Government’s delivery arrangements for welfare services and income support provided through the Centrelink program. In 2013–14, the department handled 43.1 million telephone calls for Centrelink services—an average of around 800 000 calls per week—at a cost of some $338 million. The large volume of calls handled by the department is unique in comparison with other Australian call centres in either the public or private sectors.6 Many of the calls made by Centrelink customers are technically complex—relating, for instance, to the application of various income and asset tests—and may also involve support for customers with complex needs.7 Since 2012–13, the department’s key performance indicator (target KPI) for all telephone services to customers has been an average speed of answer of less than or equal to 16 minutes.8

8. The department faces the challenge of managing significant call volumes for Centrelink services while also transitioning to revised service delivery arrangements, through Smart Centres and self-service options. Smart Centres are undergoing a major reorganisation of work focused on achieving efficiencies and improved customer service by deploying staff more flexibly, introducing new technology and using a different system for distributing telephone calls. The department also has a long term strategy to move most customer transactions from a personal service basis (conducted by telephone or face-to-face) to a self-managed basis (conducted mainly over the internet) so as to focus customer service staff and telephone support on more complex services and customers most in need. However, while this transition is underway (for instance, mobile app transactions increased from 8.6 million in 2012–13 to 36.1 million in 2013–14), it will take time for customer behaviour to change and to realise expected benefits. In the interim the telephone remains a significant channel for customers seeking access to Centrelink services and assistance with online service channels, as digital services can vary in their ease-of-use and reliability.

9. Overall, the Department of Human Services is making progress in its transition to revised delivery arrangements for Centrelink services through its Smart Centre and self-service initiatives, while continuing to face challenges in managing a significant volume of telephone calls from Centrelink customers. The department is pursuing a number of useful reforms under its transformation program for Smart Centres—including the reorganisation of work, the introduction of new telephony technology and a digital strategy9—with the aim of improving overall efficiency and customer outcomes, including call wait times. Human Services has also established a soundly-based quality assurance framework for Centrelink telephone services, which should be extended to all relevant staff to improve the overall level of assurance. While Human Services’ data indicates that the department has met its overall target for all customer telephone services in the last two years10, the more detailed results for Centrelink telephone services show an increase in average speed of answer from well under 16 minutes in 2012–13 to over 16 minutes in 2013–14.11 From a customer perspective, the 16 minute average speed of answer target for Centrelink telephone services is much higher than targets recently set for other telephony services provided by the department12 as well as those set by other large Australian call centres. Further, the current target does not provide a clear indication of the wait times Centrelink telephone customers can generally expect, due to the distribution of actual wait times around the ‘average’. Centrelink customers also continue to experience high levels of call blocking13 and call abandonment14, which can further impact on the customer experience.

10. When customers call a Smart Centre to access Centrelink services they can have a variety of experiences. Of the 56.8 million calls made to Centrelink 1800 or 13 telephone numbers in 2013–14, 43.1 million calls were able to enter the network while 13.7 million calls were unable to enter the network, that is, the calls were blocked and the callers heard the ‘busy’ signal. Of the 43 million calls in 2013–14 that were able to enter the network, around 45 per cent were answered by a Service Officer (SO) and around a quarter were resolved in the Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system.15 The ANAO estimates that the remaining calls, around 30 per cent, were abandoned; that is the customer hung-up without resolving the reason for their call. The 45 per cent of calls that resulted in access to a SO waited for an average of 16 minutes and 53 seconds prior to talking to a SO and callers who abandoned their call after entering the queue to talk to a SO waited an average of 9 minutes and 42 seconds before hanging up. Reflecting these access issues, call wait times have been the largest single cause of complaint regarding Centrelink services in each of the past three years, with customer satisfaction with Centrelink telephone services falling to 66.6 per cent in 2013–14 from 70.4 per cent in 2012–13.16

11. Further, from the customer perspective, the department’s target KPI relating to average speed of answer does not clearly indicate what service standard customers can expect, due to the distribution of actual wait times around the ‘average’. In 2013–14, for example, for the top 10 Centrelink telephone lines17, 36 per cent of customers waited less than 10 minutes while some 30 per cent waited for more than 30 minutes.18 Other large customer service organisations, such as the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), express their call metric in a way that provides customers with more helpful information in this regard. By way of example, the target for the ATO’s general enquiry line is 80 per cent of calls answered within five minutes19, meaning that ATO customers can expect that most times their call will be answered within five minutes.

12. The department’s overall target for all customer telephone services—average speed of answer within 16 minutes—has been agreed with government. From 2014–15, the department will report separately on the performance of the Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support programs. While separate reporting is a positive development, there is no documented rationale as to why the revised targets set for average speed of answer for Medicare and Child Support services are significantly lower than the target for Centrelink services. Similarly, there is no clear reason why the department’s quality assurance mechanism for telephone calls—Quality Call Listening (QCL)—is not applied to all staff handling calls, including staff with less experience who may therefore be at greater risk of making errors. To improve the level of assurance provided by QCL, the department should apply the framework to all relevant staff.20

13. It is a matter for the Government and the department to set service standards taking into account the resources available, systems capability and longer term strategies to shift customers to self-service. In this context, appropriate regard should be given to relevant industry benchmarks and the customer experience. The ongoing target for average speed of answer for Centrelink telephone services is very much at the upper end of the range of organisations and benchmarks examined. One consequence of high average wait times is that around 30 per cent of calls are abandoned by customers before the reason for the call is addressed. As mentioned, customer satisfaction with Centrelink telephone services is falling and ‘access to call centres’ is the largest cause of customer complaints about Centrelink services. Community stakeholders interviewed by the ANAO for this audit also drew attention to problems for customers relating to lengthy call wait times.21 Against this background, the department should review performance measures for Centrelink telephone services to clarify the service standards that customers can expect and to better reflect customers’ feedback and experience.

14. In a resource constrained environment, it is necessary to make choices about the allocation of limited resources. The department is pursuing a transformation program for service delivery, with a focus on realising efficiencies by transitioning customers to self-service where possible, and reserving telephone services for more complex cases and those customers most in need. Nonetheless, while this transition is underway, in the short to medium term the telephone remains a key access channel for Centrelink services and a way of providing assistance to those experiencing difficulties using digital channels, as evidenced by the very large volume of calls handled. Consistent with international trends, Centrelink customers are often using Smart Centres as a ‘help desk’ when accessing digital channels22 and while it is not known, at this stage, whether this trend is likely to be transitional or ongoing, there is a need to appropriately manage the telephony channel so as to provide a reasonable customer experience while also developing a viable pathway to the planned state.

15. The ANAO has made three recommendations focusing on: the implementation of a channel strategy to help deliver improved services across all customer service channels and a more coordinated approach to the management of call wait times; the application of the department’s quality assurance mechanisms to all relevant staff in Smart Centres; and the review of target KPIs to better reflect the customer experience and to clarify the service standards that customers can expect.

Key findings by chapter

Managing Customer Wait Times (Chapter 2)

16. Wait times for Centrelink telephone services have increased significantly in recent years from an average of 3 minutes and 5 seconds in 2010–11 to an average of 16 minutes and 53 seconds in 2013–14. Key factors underlying the increase include: reductions in the number of staff answering telephones; the performance and reliability of other customer service channels; and the more limited use of call blocking from late in 2011. While Human Services wishes to reduce the demand for telephone services by encouraging customers to use self-service channels, difficulties with using digital channels can lead to customers making telephone calls to seek assistance with online transactions. Comparisons with other large customer service organisations that deliver telephone services indicate that the department’s average wait times for Centrelink telephone services are very much at the upper end of contemporary service delivery standards.23 Average wait times for Centrelink telephone services are also significantly above the separate targets recently set for the department’s Medicare and Child Support telephone services.24 Further, Centrelink customers continue to experience call blocking and call abandonment.

17. Customer satisfaction with Centrelink telephone services is falling, ‘access to call centres’ is the largest cause of customer complaints about Centrelink services, and community stakeholders interviewed by the ANAO, as well as a 2014 Commonwealth Ombudsman’s report, drew attention to problems for customers relating to lengthy call wait times. For instance, Indigenous people in remote communities who may share the one telephone available in an Indigenous Agent’s premises sometimes take more than one day to access telephone services. In these circumstances, people may need to queue to use the telephone and may miss out if others’ calls are lengthy, as the Agent’s premises may only be open for a limited time each day.

18. In 2011–12, when call wait times began to increase significantly, the department responded by establishing a Call Improvement Taskforce (CIT). While the CIT did not operate within an overarching channel strategy it did have a useful five point strategy, providing a coordinating framework for its activities. Since the CIT was wound-up in 2013, the department has pursued a range of initiatives to reduce wait times, and recently advised that work was underway to scope the development of a channel strategy, consistent with sound practice25, to help coordinate these initiatives within the context of the department’s transformation program for service delivery.26

Managing Quality and Efficiency (Chapter 3)

19. A sound quality control framework can help provide assurance that Smart Centres deliver consistently high quality Centrelink telephone services. Further, the more efficiently such services can be delivered, within available resourcing, the greater the potential for improving productivity and/or reducing costs.

20. The department has two quality assurance frameworks in place to measure the accuracy and quality of its Centrelink telephony services: Quality On Line (QOL) and Quality Call Listening (QCL), both of which are underpinned by ‘check the checkers’ processes. The QOL framework is soundly-based and results for Smart Centres have been good with the target correctness rate of 95 per cent generally being met.

21. While the department has a well-established QCL framework for measuring and monitoring the quality of SOs’ customer interactions, which formally applies to all staff answering telephones, there are a number of gaps in the QCL framework’s implementation. Intermittent and Irregular employees (IIEs)—who will generally have relatively lower levels of experience and may therefore be at greater risk of making errors—are not currently included in QCL processes in Smart Centres.

22. The number of calls per SO required to be monitored in the QCL framework falls within the range of other call centres examined by the ANAO. However, the implementation of the required four calls per experienced SO and eight calls per new SO is low. Participation rates in calibration exercises for QCL evaluators are also relatively low. To maintain the integrity of the Quality Call Listening (QCL) process, the department should review the potential impact of these gaps in the implementation of QCL.

23. A number of measures have been used at various times to help the department assess the efficiency of Centrelink telephone services, including Average Handle Time27 and First Call/Contact Resolution.28 In recent years, the department’s Average Handle Time for Centrelink telephone services and First Contact Resolution have been broadly within the range experienced by other call centres. For instance, in 2013–14 the Average Handle Time for Centrelink telephone services was 8 minutes and 20 seconds compared to 9 minutes and 32 seconds for the ‘education and government’ sector of a global survey of call centres.29 However, the department’s performance against both Average Handle Time and First Contact Resolution declined in 2013–14 relative to the previous year.30 While transitional issues associated with the implementation of Smart Centres appear to have contributed to these declines in performance, continued analysis by the department of its performance against these key efficiency measures would help confirm the factors behind these trends. Analysis would also assist in evaluating delivery of the expected benefits from Smart Centres, new technology capabilities, and structural changes to the department’s telephony workforce.

Performance Measurement, Monitoring and Reporting (Chapter 4)

24. The department internally monitors the performance of Smart Centres against a range of useful, albeit traditional call centre metrics. A number of internal targets have also been established. While these metrics are an aid to assessing performance information at an operational level, they provide a more limited basis for assessing customer outcomes and the success or otherwise of the Smart Centre concept. There would be value in examining existing metrics and their fitness for purpose in the Smart Centre environment. In particular, the department could usefully focus on:

- First Call/Contact resolution—as improving resolution rates is a key goal of the Smart Centre concept;

- the IVR system—to assess its effectiveness in resolving calls without having to speak to a SO; and

- the interpretation of Average Handle Time—which has changed following the blending of telephony and processing work.

25. Human Services currently uses the average speed of answer as the single KPI for its public reporting on telephony services.31 This target KPI is both relevant and reliable for its intended purpose, as it addresses a significant aspect of the department’s telephone services and can be quantified and tracked over time. However, it is not complete as it does not provide insight into the range of customer telephony experiences, including the service levels that most customers can expect and the incidences of call blocking and abandoned calls.

Summary of entity response

The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Human Services. The department’s summary response to the audit report is provided below. The formal departmental response is included at Appendix 1.

The Department of Human Services agrees with ANAO recommendations 1 and 2 and agrees with qualifications to recommendation 3. The department considers that implementation of recommendations 1 and 2 will further assist in the management of Centrelink telephony services.

The department has already commenced documenting its channel strategy to reflect the work already in place. Additionally, the department is developing a new Quality Call Framework which will enhance the informal and formal mechanisms already in place.

The department currently meets its agreement with Government through its Key Performance Indicator (KPI) for telephony which is answering calls with an average speed of answer of 16 minutes. The KPIs that the department has across all its services and channels are dictated by the funding available for the department to meet its obligations. The department has estimated that to reduce the KPI to an average speed of answer of 5 minutes, it would need an additional 1000 staff at a cost of over $100 million each and every year. The transformation of the department’s services over the past three years has been profound. In accordance with the Government’s agenda on digital services, customers now have a greater range of ways to do their business with the department. For some customers, the predominant method of contact with the department is now online. This trend will increase as the department builds more online capability and the Welfare Payments Infrastructure Transformation (WPIT) programme will shape the future of delivery for the department for the next decade.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.45 |

To help deliver improved services across all customer channels and a more coordinated approach to the management of call wait times, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Human Services establish a pathway and timetable for the implementation of a coordinated channel strategy. Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.14 |

To maintain the integrity of the Quality Call Listening (QCL) process and improve the level of assurance on the quality and accuracy of Centrelink telephone services, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Human Services applies the QCL framework to all staff answering telephone calls, and reviews the potential impact of gaps in the implementation of QCL. Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 4.26 |

To clarify the service standards that customers can expect and to better reflect customer experience, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Human Services review Key Performance Indicators for the Centrelink telephony channel, in the context of the implementation of a coordinated channel strategy. Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed, with qualifications. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides background information on the Department of Human Services’ Centrelink telephone services. This chapter also outlines the audit approach including its objective, scope and methodology.

Background

1.1 The Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) Centrelink program delivers a range of government payments and related services to Australians.32 In 2013–14 the department processed 3.7 million Centrelink program claims and paid over $108 billion to individual customers for Centrelink related transactions on behalf of the Australian Government.

1.2 One of the most common ways that customers contact Human Services is via the telephone. In 2013–14 around 43 million calls were handled by the department relating to the Centrelink program. Human Services manages over 50 Centrelink-related telephony lines, each with its own 1800 or 13 telephone number.33 Each of the main payment types has its own line. There are also a number of ‘boutique’ lines for smaller groups of clients, for example, a line for agents34 and a number of lines used for disaster relief such as that established for the Queensland floods in 2010–11.

1.3 Table 1.1 sets out the ten telephone lines which accounted for over 70 per cent of answered calls in 2013–14. The telephone line which had the most answered calls was the Families and Parenting line followed by the Employment Services line.

Table 1.1: Top ten telephone lines in 2013–14

|

Telephone Line |

Total answered calls 2013–14 |

|

Families and Parenting |

6 614 051 |

|

Employment services |

3 102 514 |

|

Disability, Sickness and Carers |

1 929 791 |

|

Youth and Students |

1 280 408 |

|

Older Australians |

1 335 538 |

|

Participation Solutionsa |

1 419 366 |

|

Income Management - BasicsCard After Hours |

645 926 |

|

Income Management - BasicsCard Enquiries |

349 960 |

|

Tip off line - Centrelink |

52 664 |

|

Indigenous |

307 440 |

|

Total of top 10 telephone lines |

17 037 658 |

Source: Department of Human Services data.

Note:

a Participation Solutions is a telephone line that interacts with customers who receive activity tested payments who have not met their activity obligations.

1.4 Calls are managed and distributed nationally through a virtual network. Customers are asked to identify the reason for their call and the call is then distributed to staff located across Australia according to ‘skill tags’35 which identify staff with the required skills. Generally telephone lines are open from 8am to 5pm, Monday to Friday (except public holidays). Some lines, including the Families and Parenting line and the BasicsCard, are open for longer.36 The emergency lines (to handle disaster recovery), which operate from the Geelong Smart Centre, are generally open 24 hours, 7 days per week.37 Some telephone enquiry lines are prioritised differently. For example, callers using emergency lines receive priority.38 Calls to the tip-off line, where people can report possible fraud, also receive a higher priority.

Smart Centres

1.5 Previously referred to as call centres, the department now provides telephone services through Smart Centres. Human Services operates 29 Smart Centres that provide Centrelink services. All of these centres also provide Medicare Public services and nine of these locations provide multi-lingual services. In 2013–14 a total of 56.8 million calls were made to Centrelink 1800 or 13 numbers—the processing of these calls is illustrated in Figure 2.1 in Chapter 2.

1.6 The shift to Smart Centres, which began in 2012–13 and is still being implemented, is changing the way work is organised in a number of ways. Previously, telephony and processing work were undertaken separately and both telephony and processing work were arranged by ‘customer segment’ and payment type. Staff specialised in one or more of these customer segments, which included Older Australians, Disabilities, Carers, and Families. In the call centre environment, there was some flexibility to move staff to cope with peaks in telephony workloads in particular customer segments but very limited flexibility to deploy staff across telephony and processing work.39

1.7 One of the key objectives behind the move to Smart Centres is a desire to blend telephony and processing work. The new arrangements involve staff being cross-trained in both types of work and being used flexibly depending on work priorities and their skills. For instance, Service Officers (SOs) taking calls will also perform some limited processing work while the customer is on the telephone, to assist in achieving more timely outcomes for customers. Therefore the distinction between call and processing is becoming increasingly blurred as the implementation of Smart Centres proceeds.

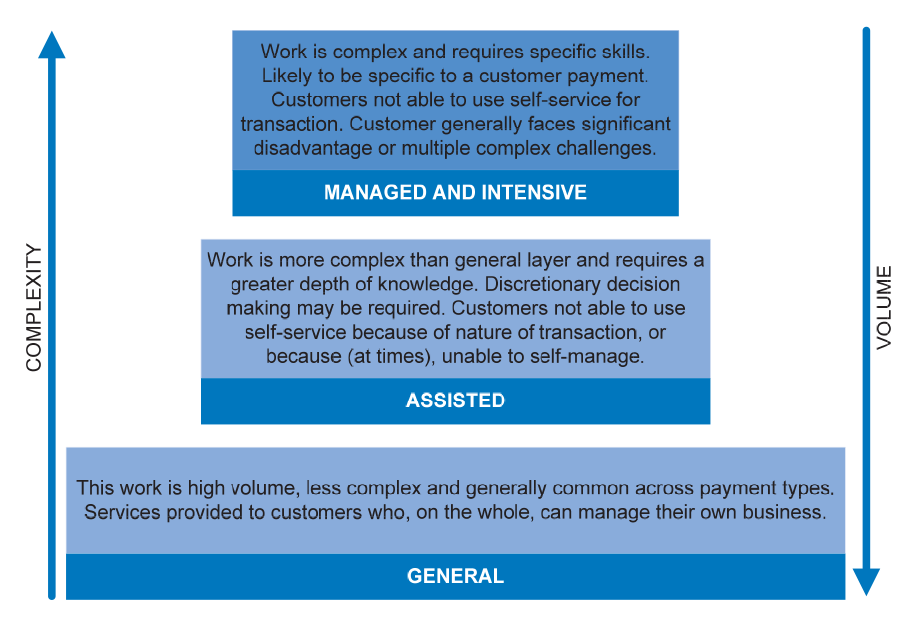

1.8 Another key objective is moving away from work organised around payment types and customer segments to organising work around the complexity and frequency of customer transactions. Customer transactions and enquiries have now been categorised into a ‘Skills Pyramid’, with lower complexity

and/or high frequency transactions/enquiries making up the ‘general’ base layer of the pyramid. Higher complexity and less frequent transactions are found further up the pyramid in the ‘assisted’ and ‘managed and intensive’ layers.40

Service delivery transformation

1.9 The Department of Human Services’ Strategic Plan 2012–16 outlines a high level strategy to transform service delivery:

- when appropriate, move transactions from a personal service basis (face-to-face or telephone) to self-managed mechanisms; and

- customer service staff are to focus on more complex services and helping those most in need rather than dealing with simple transactions. 41

1.10 Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services are being managed in the context of this high level strategy and within a dynamic service delivery environment of changing technology, customer expectations and preferences, and the pursuit of efficiencies in service delivery. Human Services’ customers can access services through an increasing variety of channels42 and performance in one channel increasingly affects other channels.43 More recently available channels include the trialling of virtual face-to-face services through video conferencing, online transactional services, and a growing range of mobile apps which allow customers to view and update their personal information, fulfil their reporting obligations, apply for advance payments and read their online letters at a time and place that suits them.44

1.11 Table 1.2 presents data on Centrelink self-managed transactions from 2011–12 to 2013–14. Consistent with the strategy for service delivery transformation, there has been growth in online transactions and very strong recent growth in mobile apps. However, the number of telephone self-service transactions have remained largely unchanged over this same period.

Table 1.2: Transactions for digital and online services 2011–12 to 2013–14

|

Channel |

2011–12 (million) |

2012–13 (million) |

2013–14 (million) |

|

Online services transactions |

48.0 |

58.1 |

59.7 |

|

Telephone self-service transactions |

5.8 |

5.8 |

5.5 |

|

Express plus mobile apps transactions |

na |

8.6 |

36.1 |

Source: Department of Human Services, Annual Report 2013–14, p. 110.

Funding

1.12 Table 1.2 summarises expenditure on Centrelink Telephony Services from 2010–11 to 2013–14. In 2013–2014 the department directed $337.9 million to providing Centrelink telephony services.

Table 1.3: Expenditure on Telephony services between 2010–11 and 2013–14

|

|

Actual expenditure |

Budgeted expenditure |

||

|

|

$ million |

% Change from previous yeara |

$ million |

% Change from previous year |

|

2010–11 |

$324.6 |

0.2 |

$298.8 |

-7.5 |

|

2011–12 |

$286.1 |

-11.9 |

$299.9 |

0.4 |

|

2012–13 |

$348.4 |

21.8 |

$328.9 |

9.7 |

|

2013–14 |

$337.9 |

-3.0 |

$334.7 |

1.8 |

Source: Human Services data.

Note a: The largest component of total expenditure on Centrelink telephony is the staffing costs of the SOs answering telephones. However, since the introduction of Smart Centres from 2012 a proportion of SOs’ time has been spent on processing work thus making an accurate comparison of total expenditure on Centrelink telephony between years difficult.

1.13 From 2003–2004 to 2011–12, there was supplementary budget funding for Centrelink call centres to improve technology in call centres and to ‘ensure Centrelink is able to meet the demand arising from customers making increased use of call centres’.45 The additional funding ranged from $15.4m in 2003–04 to approximately $50–60m from 2006–2007 onwards. In the 2012–13 Budget, the supplementary funding (of just over $50m per annum) was rolled into ongoing base funding. The 2013–14 Budget provided an additional $30million ($10m in 2012–13, $20m in 2013–14), on top of the increase in base funding from the previous Budget, to ‘allow additional staff to be employed to act as a ‘surge capacity’ in call centres’.46

Recent reviews

1.14 The ANAO reported on the administration of the Australian Taxation Office’s contact centres in November 2014.47 Where pertinent, the ANAO has drawn on that performance audit to provide an Australian public sector context.

1.15 In 2014, the Commonwealth Ombudsman conducted an investigation into access and service delivery complaints about Centrelink services, including Centrelink telephone services.48 The Ombudsman’s report is discussed at times in this audit report.49

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.16 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) management of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the audit examined the management of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services against the following high-level criteria:

- Human Services offers customers effective telephone services in relation to a range of quality indicators, for example, wait times and the accuracy of the information provided;

- Centrelink call services in Smart Centres are managed efficiently; and

- Human Services effectively monitors and reports on the performance of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services.

Audit scope

1.18 The audit scope did not include:

- Smart Centres’ processing services other than the processing that is done as part of the telephone service; and

- Smart Centres’ Medicare and Child Support telephone services.

Audit methodology

1.19 The audit methodology included:

- an examination of the department’s files and documentation relating to the management of Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services;

- interviews with Human Services managers and staff involved in the management of Smart Centres, both in Canberra and in the call network;

- interviews with the department’s managers involved in the coordination and governance arrangements for Smart Centres and Human Services proposed channel strategy;

- interviews with external stakeholders including the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office and peak bodies such as People With Disability Australia and the Welfare Rights Network;

- comparisons with other large service delivery organisations; and

- site visits to a number of Smart Centres.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $459 000.

Structure of the report

1.21 The structure of the audit report is shown in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Structure of the Audit Report

|

Chapter |

Description |

|

1. Introduction |

This chapter provides background information on the Department of Human Services’ Centrelink telephone services. This chapter also outlines the audit approach including its objective, scope and methodology. |

|

2. Managing Customer Wait Times |

This chapter examines the customer experience of Centrelink telephone services and the associated wait times, levels of customer satisfaction and complaints, and the range of departmental strategies and initiatives to improve call wait times. |

|

3. Managing Quality and Efficiency |

This chapter examines the quality assurance mechanisms used by Human Services in relation to Centrelink telephone services. It also examines cost and efficiency metrics for Centrelink telephone services and compares performance with other contact centres. |

|

4. Performance Measurement, Monitoring and Reporting |

This chapter examines internal and external performance measurement, monitoring and reporting for the department’s Smart Centres’ Centrelink telephone services. |

Source: ANAO.

2. Managing Customer Wait Times

This chapter examines the customer experience of Centrelink telephone services and the associated wait times, levels of customer satisfaction and complaints, and the range of departmental strategies and initiatives to improve call wait times.

Introduction

2.1 The Department of Human Services’ Smart Centres are an integral component of the Australian Government’s delivery arrangements for Centrelink services. The operation of Centrelink telephone services can directly influence customer experiences of Commonwealth service provision, and wait times in particular can have a negative impact on individuals. In April 2014, the Treasurer, the Hon Joe Hockey MP, commented that the extended wait times for Centrelink telephone services are ‘… hugely expensive and undermine productivity. It undermines the capacity of people to get on with their own lives.’50 The department has acknowledged that highly vulnerable, elderly, Indigenous and disabled income support customers use the call channel as their primary means of accessing the department, and that it needs to improve its performance in this area.51 Further, the department has made a commitment in its Service Charter to its customer: ‘Easy access to services: We will give you quick and easy access to the right services’.52

2.2 In this chapter, the ANAO examines:

- the customer experience of Centrelink telephone services;

- data relating to call demand and wait times including variations in wait time across different Centrelink telephone lines;

- levels of customer satisfaction and complaints relating to Centrelink call services; and

- departmental strategies to improve call wait times.

The Customer experience of Centrelink telephone services

2.3 Figure 2.1 shows the variety of experiences customers can have when calling the various 1800 and 13 numbers for Centrelink services.

2.4 Figure 2.1 indicates that of the 56.8 million calls made to Centrelink 1800 or 13 telephone numbers in 2013–14, 43.1 million calls were able to enter the network while 13.7 million calls were unable to enter the network, that is, the calls were blocked and the callers heard the ‘busy’ signal. While this is a large number of blocked calls, and likely to have caused frustration and inconvenience for customers, it should be noted that customers whose calls were blocked do not necessarily miss out on accessing Centrelink services as they could have: made multiple calls until they were able to enter the network; rung back at a later time; or used another channel to access Centrelink services (such as online services).53

Figure 2.1: Pathway of calls through Centrelink Telephony Services in 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ documentation, based on 2013–14 data.

Notes to Figure 2.1:

a The number of blocked calls, 13.7 million, does not necessarily represent the number of customers who received the ‘engaged’ or ‘busy’ signal. The number of customers is lower because customers will often make multiple calls attempting to enter the network.

b In 2013–14, 12.1 per cent of answered calls used the place-in-queue option which allowed them to be called back rather than waiting on the line.

c This is a maximum figure, based on the assumption that no transferred calls go back into the IVR system, that is, they are all transferred into a queue to talk to a SO.

d The total number of calls entering the queue is equal to the total number of abandoned calls plus the total number of answered calls. Transferred calls are a subset of answered calls. If it is assumed that all transferred calls return to a queue rather than to the IVR system, there would be 25.3 million calls entering a queue for the first time with a further 3.3 million calls re-entering the queue.

2.5 Figure 2.1 also indicates that of the 43.1 million calls that were able to enter the network, 20.8 million calls—some 45 per cent of the calls that entered the network—were answered by a SO. Of the remaining 55 per cent of calls:

- 17.8 million calls (around 41 per cent of calls entering the network) end in the Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system54 either because:

- the customer’s enquiry was answered by the IVR message (no data available);

- the customer chose an IVR option that transferred them into a self-service application, for example, to report their latest fortnightly income. In 2013–14, 5.5 million transactions were completed in IVR self-service—comprising roughly one-third of calls that end in the IVR system; or

- the customer abandoned the call for a variety of reasons including that, after being advised by the IVR system of the estimated wait time, they decided it would take too long to access services (no data available);

- 7.8 million calls were abandoned after they had entered a queue to speak to a SO, after waiting an average of 9 minutes and 42 seconds in the queue. As indicated above, data on the number of calls that are abandoned in the IVR system is not available, therefore the proportion of total calls abandoned cannot be precisely calculated. An estimate made by the ANAO55 suggests that around 30 per cent of calls that enter the network are abandoned either in the IVR system or after the customer has entered the queue to talk to a SO.

2.6 In summary, around 45 per cent of calls made by customers that are able to enter the network are answered by a SO, an estimated 30 per cent of calls are abandoned, and the remainder are resolved in the IVR system either because the recorded messaging answers their query or the customer utilised IVR self-service options.

Demand for Centrelink telephone calls

Table 2.1: Telephone calls to Centrelink 2009–10 to 2013–14

|

|

Calls entering network |

Calls answered by SOs |

Blocked calls |

|||

|

|

million |

Change on previous year (%) |

million |

Change on previous year (%) |

million |

Change on previous year (%) |

|

2009–10 |

32.7 |

na |

27.7 |

na |

na |

na |

|

2010–11 |

37.0 |

13.2 |

28.8 |

4.0 |

39.9 |

na |

|

2011–12a |

44.2 |

19.5 |

22.3 |

-22.6 |

33.2 |

-16.8 |

|

2012–13 |

42.0 |

-5.0 |

20.1 |

-9.9 |

32.5 |

-2.1 |

|

2013–14 |

43.1 |

2.6 |

20.8 |

3.5 |

13.7 |

-57.9 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental data.

Notes:

a The annual data from 2011–12 onwards (unshaded) is affected by the department’s decision in late 2011 to make less use of call blocking to manage demand. Therefore comparisons with earlier years (shaded) need to take account of the different use of call blocking. See paragraph 2.8 for more detail.

na Not available.

2.7 Table 2.1 indicates that based on the number of calls entering the network, demand for Centrelink phone services has stabilised in the past two years after strong growth in the preceding years. Calls entering the network grew very strongly over the three years to 2011–12, and then stabilised at around 42 to 43 million in 2012–13 and 2013–14. Calls answered by SOs have also stabilised in 2012–13 and 2013–14 at around 20 million calls, down from a high of 28.8 million calls in 2010–11.

2.8 Table 2.1 also indicates that the number of blocked calls was very large until relatively recently, falling from 39.9 million in 2010–11 to 13.7 million in 2013–14. The department has advised that in the past, the then separate Centrelink used call blocking as an operational strategy to prevent wait times becoming too long. While call blocking provides a reasonably clear message to ‘try again’ at another time and can save a customer’s time in waiting for their call to be answered, there are disadvantages in the use of call blocking as customers may need to call again repeatedly or have to ring back at a time that is less convenient. The department further advised that since late 2011, it has made more limited use of the engaged signal to manage demand so that: it could more accurately gauge total demand; more callers could access telephone self-service; and callers could have the option of being advised of estimated wait times via the IVR system and then make the decision to wait or call back another time. The department indicated that this change of operational strategy in relation to call blocking was a major factor in the increase in average wait times at that time.56 Human Services advised the ANAO that currently it only blocks calls when the telephony system would otherwise become overloaded or at the end of a day when it is clear that calls will not be answered within the remaining business hours for that day. This approach more than halved the number of blocked calls in 2013–14 (13.7 million) compared to 2012–13 (32.5 million).57

Call wait times and abandoned calls

2.9 Table 2.2 presents data relating to call wait times, abandoned calls, and staffing from 2009–10 to 2013–14.

Table 2.2: Metrics relating to call wait times, staffing levels, and abandoned calls (2009–10 to 2013–14)

|

|

Answered Calls |

Average speed of answer (mins:secs) |

Frontline staff answering calls |

Abandoned Calls |

||

|

|

Millions |

Actual |

Targeta |

FTE SOsb |

% change on previous year |

% of callsc |

|

2009–10 |

27.6 |

1:29 |

na |

3891 |

na |

na |

|

2010–11 |

28.8 |

3:05 |

na |

3678 |

-5.5 |

na |

|

2011–12d |

22.3 |

11:45 |

16:00 |

2978 |

-19.0 |

16.3 |

|

2012–13 |

20.1 |

12:05 |

16:00 |

2990 |

0.4 |

15.2 |

|

2013–14 |

20.8 |

16:53 |

16:00 |

2743 |

-8.3 |

18.0 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services data.

Notes:

a The KPI used by the then Centrelink in relation to customer wait times in 2009–10 and 2010–11 was the percentage of calls answered within 2 minutes and 30 seconds. The target was 70 per cent. The target of 16 minutes for average speed of answer used by Human Services since 2012–13 is for all telephony services, not just Centrelink telephone services.

b The number of SOs on a Full-Time Equivalent basis paid out of the telephony budget. However, since the introduction of Smart Centres a proportion of SOs’ time is spent on processing work thus making an accurate comparison of FTE staff answering calls between years difficult. The department adjusted the FTE staffing numbers downwards in 2012–13 and 2013–14 for the intensive commencement training undertaken by IIEs as these staff were not available to answer phones. The data for 2013–14 has also been adjusted downwards for the department’s estimate of the processing work undertaken by telephone staff (10 per cent of ongoing staff and all weekend hours for IIE staff).

c The number of abandoned calls (calls where the caller hangs up after they have entered the queue to talk to a SO) as a percentage of the calls that enter the network. This data does not include calls abandoned in the IVR system.

d The annual data from 2011–12 onwards (unshaded) is affected by the department’s decision to make less use of call blocking since late 2011 to manage demand. Therefore comparisons with earlier years (shaded) need to take into account the different use of call blocking. See paragraph 2.8 for more detail.

na Not available.

2.10 Table 2.2 indicates that the average speed of answer—a metric that Human Services uses to measure call wait times58—deteriorated significantly from three minutes and five seconds in 2010–11 to 11 minutes and 45 seconds in 2011–12. As indicated earlier the department advised that the more limited use of call blocking was a significant factor in the increase in call wait times. The number of full-time equivalent SOs also fell by 19 per cent in 2011–12. The reduction in frontline staff answering calls in 2011–12 coincided with a threefold increase in call wait times. The number of SOs again fell significantly by 8.3 per cent in 2013–14, coinciding with an increase in average speed of answer from 12 minutes and 5 seconds to 16 minutes and 53 seconds. The data indicates that staff reductions have impacted on call wait times.

2.11 Table 2.2 also shows that the rate of abandoned calls, once a caller has gone through the IVR system and entered the queue to talk to a SO, was similar in 2011–12 and 2012–13, at around 15 to 16 per cent of all calls that entered the network—but increased to 18 per cent in 2013–14 as average waiting times increased by more than 30 per cent. As discussed in paragraph 2.4 and in the box below, ANAO analysis indicates that in 2013–14 around 30 per cent of calls made to access Centrelink services were abandoned when account is taken of calls abandoned in the IVR system.59

|

Cost to customers of abandoned calls |

|

The ANAO estimates that in 2013–14, just under one third of customers (nearly 14 million calls) who were able to enter the Centrelink telephone network hung up before the reason for their call was resolved. Around 6 million of these calls were estimated to be abandoned in the Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system, often when callers were advised by an IVR message of the estimated wait times to talk to a Service Officer (SO). Generally, the calls that were abandoned in the IVR, while causing some inconvenience, did not take up significant amounts of the customer’s time. However, more than half of the calls that were abandoned occurred after the customer had invested time waiting to speak to a SO. In 2013–14, 7.8 million calls were in this category and the average time that customers spent waiting before they abandoned the call was 9 minutes and 42 seconds. These abandoned calls represent a lost investment of time and effort by the customer. While customers make the decision to abandon their calls, the longer that they spend waiting to talk to a SO, the more likely it is that events will intervene, for example, the doorbell rings, dependents need care, another call comes through on the line, mobile phones run out of battery or signal, or workplace tasks (for those customers who are employed, such as a significant proportion of those receiving family or childcare payments) require attention. The ANAO estimates that in 2013–14, the time lost by customers prior to abandoning their calls, after going through the IVR system, cumulatively totalled some 143 person-years.a |

Note a: The ANAO based its estimate of time lost in person-years on the average time customers waited on the phone prior to abandoning the call after entering a queue to talk to a SO. The estimate did not include the time taken to navigate the IVR system and did not including any calls abandoned within the IVR system. See Appendix 3 for more details on the methodology.

2.12 The target KPI used by the department in its public reporting of telephony services—average speed of answer of less than or equal to 16 minutes—gives limited information on the variability in the wait times experienced by customers. Table 2.3 presents data on answered calls by time intervals for the ten telephone lines that accounted for around 70 per cent of answered telephone calls in both 2012–13 and 2013–14.

Table 2.3: Answered calls by telephone line and time interval

|

Telephone Line |

Less than 10 mins % |

10 to 20 mins % |

20 to 30 mins % |

More than 30 mins % |

||||

|

|

2012 –13 |

2013 –14 |

2012 –13 |

2013 –14 |

2012 –13 |

2013 –14 |

2012 –13 |

2013 –14 |

|

Disability, Sickness and Carers |

37 |

26 |

27 |

17 |

22 |

24 |

14 |

34 |

|

Employment services |

42 |

18 |

23 |

18 |

21 |

19 |

15 |

45 |

|

Families and Parenting |

41 |

48 |

23 |

19 |

20 |

16 |

16 |

17 |

|

Indigenous |

46 |

27 |

19 |

15 |

26 |

26 |

10 |

33 |

|

Older Australians |

39 |

29 |

28 |

19 |

22 |

24 |

12 |

29 |

|

Youth and Students |

33 |

18 |

21 |

10 |

24 |

14 |

22 |

58 |

|

Income Management- BasicsCard After Hours |

97 |

92 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Income Management- BasicsCard Enquiries |

90 |

88 |

9 |

9 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tip off line - Centrelink |

99 |

99 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Participation Solutions |

42 |

15 |

21 |

15 |

15 |

18 |

23 |

52 |

|

Total of top 10 telephone lines |

42 |

36 |

22 |

16 |

20 |

17 |

15 |

30 |

Source: Department of Human Services data.

2.13 The 2013–14 data indicates that just over one third of calls (36 per cent) were answered within 10 minutes, with around half of all calls answered within 20 minutes. Thirty per cent of callers waited over 30 minutes. This data is a significant deterioration from the previous year when only 15 per cent of callers waited more than 30 minutes. Callers on different lines also had different experiences, for example, in 2013–14 over half of customers calling the Participation Solutions line waited over 30 minutes whereas nearly all calls on the Income Management and Tip-off lines were answered within 20 minutes. The department advised that for certain telephone lines, such as ‘Youth and Students’, decisions have been taken to distribute resources to allow relatively longer wait times on these telephone lines to act as an incentive for this cohort to move to self-service using other channels such as apps and online.

Comparison of call wait time targets

2.14 To gain some perspective on the department’s approach to measuring its performance on call wait times, the ANAO reviewed the timeliness performance measures used by a selection of large government and non-government service delivery organisations. While there was variation in the targets adopted by organisations, a typical target for response times was a majority of calls answered within two or three minutes.

2.15 Since 2012–13, Human Services has used an average speed of answer of less than or equal to 16 minutes as the single KPI for external reporting purposes for all telephony services including Medicare and Child Support services. The department advised that it developed this KPI based on internal information and modelling, including consideration of the department’s funding and projected resourcing. However, departmental documentation about the decision to establish this KPI was not available to the ANAO. From 2014–15 the department will report Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support telephony performance separately against the KPI of average speed of answer. From the separate 2014–15 targets listed in Table 2.4, it can be seen that targets for Medicare and Child Support customers are significantly lower than the 16 minute target for Centrelink phone services, at 7 minutes and 3 minutes respectively. There is no documented rationale as to why these targets differ.

Table 2.4: Timeliness performance measures of a selection of organisations

|

Organisation |

Performance Measure |

|

Department of Human Services |

|

|

Average speed of answer ≤ 16 minutes |

|

Average speed of answer ≤ three minutes |

|

|

|

Average speed of answer ≤ seven minutes |

|

Average speed of answer ≤ two minutes |

|

Average speed of answer ≤ 30 seconds |

|

Australian Taxation Office |

|

|

80 per cent of calls answered within five minutes |

|

90 per cent per cent of calls answered within two minutes |

|

Department of Immigration and Border Protection |

85 per cent of calls answered ≤ 10 minutes |

|

Government of Canada—Canada Revenue Agency |

Calls answered ≤ two minutes |

|

Qantas |

Calls answered ≤ three minutes |

|

United Kingdom Government—Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs |

Focuses on measuring the percentage of successful calls |

|

United States Government—Inland Revenue Service |

Average speed of answer performance measure in 2013 ≤ 15 minutes |

|

Westpac Banking Group |

Various measures. Up to 90 per cent ≤ 90 seconds. Westpac advised that it is planning to reduce this to up to 90 per cent ≤ 60 seconds |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.16 A global benchmarking report60 of contact centres indicates that the overall average speed of answer in 2013 for the 817 organisations included in the report was 30 seconds; and for the Education and Government sub-sector, the overall actual achievement was 49 seconds in the same year. These comparisons suggest that both the actual wait time for Centrelink telephone services and the department’s relevant performance target (less than or equal to 16 minutes) are very much at the high end compared to a number of other government and private sector organisations that deliver services via the telephone including for the Medicare and Child Support telephone services provided by Human Services.

Customer satisfaction and complaints

2.17 Lengthy call wait times and call blocking impact on customer satisfaction and are a major source of complaints. The global benchmarking report on contact centres noted above observes that customer satisfaction and complaints are the top indicators of the operational performance of telephone services.61

Customer satisfaction

2.18 Human Services measures customer satisfaction of telephony services provided by Smart Centres on a regular basis.62 The overall satisfaction rate with Centrelink telephony services was 70.4 per cent in 2012–13 and dropped to 66.6 per cent in 2013–14. This result is significantly below the average customer satisfaction rate for 2013 in the global benchmarking report of call centres of 79.2 per cent.63

Complaints

2.19 Table 2.5 presents data on complaints to Human Services about Centrelink services from 2009–10 to 2013–14.

Table 2.5: Complaints (per cent of total complaints about Centrelink services) (2009–10 to 2013–14)

|

Reason for complaint about Centrelink services |

2009–10 (%) |

2010–11 (%) |

2011–12 (%) |

2012–13 (%) |

2013–14 (%) |

|

Staff knowledge and practice |

28.6 |

26.2 |

21.6 |

19.4 |

17.8 |

|

Access to call centre |

14.3 |

19.9 |

26.4 |

23.2 |

23.5 |

|

Access to call centre – wait time |

0.2 |

0.8 |

16.0 |

14.2 |

18.8 |

|

Access to call centre – call busy |

13.6 |

18.5 |

9.7 |

8.5 |

4.0 |

|

Decision making |

13.2 |

12.4 |

11.6 |

12.3 |

15.8 |

|

Staff attitude |

13.8 |

12.3 |

11.2 |

11.5 |

10.0 |

|

Disagree with internal policy/procedure |

6.5 |

6.5 |

5.2 |

3.9 |

5.3 |

|

IVR |

3.0 |

2.4 |

4.1 |

5.9 |

5.1 |

|

Online services |

2.4 |

3.3 |

2.2 |

4.6 |

6.5 |

Source: Data provided by Human Services.

2.20 The department’s complaints data indicates that the largest single cause of complaint regarding Centrelink services over the past three years has been ‘access to the call centre’. In 2013–14, this category comprised 23.5 per cent of complaints, of which 18.8 per cent concerned wait times and four per cent related to the use of the busy signal or call blocking. The impact of the reduced use made by the department of call blocking since late in 2011 can be seen in the data in Table 2.5—since 2011–12, complaints about hearing the ‘call busy’ signal reduced while complaints about call wait times increased.

2.21 In 2014, the Commonwealth Ombudsman conducted an investigation into access and service delivery complaints about Centrelink services, including Centrelink telephone services.64 Typical complaints reported included:

- waits of up to one hour in telephone queues;

- wait times far in excess of the estimated wait times customers were told via a recorded message at the start of their call;

- costs of call wait times when using mobile telephones;

- calls transferred between telephone lines compounding wait times; and

- customers being told to call another number once the initial call was answered after a considerable wait time.

2.22 A number of community stakeholders interviewed for this audit65 also drew attention to problems relating to lengthy call wait times; for instance: people with a disability often access telephone services with the assistance of a carer and in these circumstances both the person with the disability and the carer experience lengthy wait times; and Indigenous people in remote communities who may share the one telephone available in the Indigenous Agent’s premises sometimes take more than one day to access telephone services. In these circumstances, people may need to queue to use the telephone and may miss out if others’ calls are lengthy as the Agent’s premises may only be open for a limited time each day.

Call Improvement Taskforce

2.23 In July 2012, the department established a Call Improvement Taskforce (CIT) in the context of significant increases in call wait times for Centrelink telephone services. The establishment of the CIT followed a review which recommended ‘a prioritised action plan for improvements and investment within the telephony processing channel’.66

2.24 The CIT operated under two phases. The first phase, from July to November 2012, focused on identifying, implementing and monitoring short term projects that could result in ‘quick wins’ in terms of reducing call wait times. The second phase, from December 2012 to June 2013, focused on the ongoing monitoring of a small number of projects from phase one, along with the implementation of further short term improvement opportunities, combined with analysis of issues requiring more in-depth study or more complex implementation arrangements.

2.25 In both phases the membership of the CIT involved the department’s senior leadership and was chaired at the Associate Secretary level, with representatives at the Deputy Secretary, General Manager (SES Band Two) and National Manager levels (SES Band One) from a range of relevant areas. In both phases the CIT met regularly: in phase one, the CIT met twice a month; moving to around monthly in phase two. A Senior Responsible Officer at the SES Band Two level was made responsible for implementing Taskforce outcomes and to oversee both phases of the CIT.67

2.26 The CIT developed a five point strategy which covered:

- reducing the need for customers to call, for example, improving the quality of letters—unclear letters generate telephone calls;

- increasing the use of self-service, for example, online services and mobile apps;

- improving call centre technology, for example, the introduction of

place-in-queue call back (see paragraph 2.30); - increasing the efficiency of the call network, for example, better balancing the rostering of employees and call demand; and

- adjusting resources to cope with demand, for example, use of Smart Centres to flexibly utilise staff across telephony and processing work to assist in dealing with periods of peak demand.

2.27 While the CIT did not operate under the framework of an overall channel strategy68, the five point strategy covered the key factors that impacted on call wait times including the inter-relationships between channels. The five point strategy was used to organise the initiatives that were implemented under the CIT.69

2.28 Overall, the CIT had effective processes for monitoring and reporting on initiatives.70 The framework for reporting progress on each initiative and stream included an overall status report using a traffic light reporting system and a benefits realisation component.71 The reporting on each initiative contained an estimate of one or more of the following issues:

- potential reduction on call wait times (expressed as minutes of calls);

- projected reduction in call volume (as minutes of calls);

- diversion of staff to telephones (in full-time equivalent staff numbers); and

- other measures such as number of claims to be completed.

Management of call wait times after the Call Improvement Taskforce

2.29 At the end of June 2013, the CIT ceased operating and the initiatives that were ongoing or incomplete were transferred to a line area within the department for management on a ‘business as usual’ basis. Central monitoring and reporting of these initiatives as a package of inter-related measures no longer occurred. The department has since pursued a range of initiatives to manage call wait times in the context of its service delivery transformation strategy to transfer, where possible, customers to self-service channels. These measures are outlined in the following paragraphs.

Place–in–Queue call back

2.30 Human Services began trials of place-in–queue call back technology on a number of its telephone lines in 2012 to reduce the impact on customers of long call wait times. Access to place-in-queue call back has been progressively expanded over subsequent years. Place-in-queue allows customers to choose to be called back instead of staying on the line waiting for their call to be answered.72 Place-in-queue is automatically offered to eligible customers when the estimated wait time in a queue is more than five minutes. It is available on nine Centrelink telephone lines although, for two of those lines, it is only offered to customers calling from mobile telephones.73 In 2013–14, 12.1 per cent of answered calls used the place-in-queue option.

Smart Centres

2.31 The shift from a traditional call centre to the Smart Centre concept is a key initiative in the department’s efforts to reduce call wait times. In the previous call centre environment, there was limited flexibility to move staff to cope with peaks in workload for particular customer segments/payment types or between telephony and processing. This lack of flexibility contributed to longer wait times in peak times; customers were also transferred between SOs if their call dealt with issues crossing payment types.

Blending telephony and processing work

2.32 One of the key components of the Smart Centre concept is to blend telephony and processing work to increase flexibility in the deployment of staff. This approach involves staff being cross-trained in both types of work and being used flexibly depending on work priorities and their skills. Enabling technology, once fully functional74, will allow call and processing work to be prioritised and managed centrally, with workflows distributed across all work stations in Smart Centres. SOs taking calls also perform some limited processing work while the customer is on the telephone to assist in achieving more timely outcomes for customers. Therefore, as previously mentioned, the distinction between telephone work and processing work is becoming increasingly blurred.

2.33 During the ANAO’s site visits for the audit, it was clear that the blending of telephony and processing work was still in the transitional stage. While telephony staff were commonly undertaking processing tasks during the call, and were being offered overtime to complete processing work on the weekends, it was less common that processing staff were undertaking telephony work. The ICT equipment to allow work to be blended across all telephony and processing staff was not yet in place at all workstations. However, many of the SOs and managers interviewed by the ANAO in Smart Centres were positive about the benefits already achieved from blending, including the opportunity for more varied work for staff and more First Contact Resolution75 for customers.

|

Case Study – Benefits of blending telephony and processing: handling Mobility Allowance enquiries |

|

Mobility Allowance is a payment for eligible Australians in the labour market who cannot use public transport without substantial assistance because of their disability, injury or illness. Customer enquiries about Mobility Allowance were previously managed via telephony staff, and a separate team of processing staff were responsible for completing Mobility Allowance reviews. In 2013, Human Services initiated a trial which would enable the blending of the telephony and processing aspects of Mobility Allowance work into one team. A number of positive outcomes resulted from the trial. By blending telephony and processing work, Human Services reported an increase in First Contact Resolution for customers as SOs were skilled to perform all tasks for the program rather than having to ‘hand-off’ work. Human Services reported receiving positive responses from a customer survey conducted as part of a review of the trial and also identified a significant reduction in the backlog of Mobility Allowance processing work. The blending of processing and telephony work for mobility allowance has now become business as usual. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services documentation.

Skills Pyramid

2.34 Another key component of Smart Centres is moving away from work organised around payment types and customer segments to work being organised around the complexity and frequency of customer transactions. Customer transactions and enquiries have been categorised into a ‘Skills Pyramid’. Lower complexity and/or high frequency transactions/enquiries make up the ‘general’ base layer of the pyramid while higher complexity and less frequent transactions are found further up the pyramid in the ‘assisted’ and ‘managed and intensive’ layers. Figure 2.2 illustrates the Skills Pyramid.

Figure 2.2: Skills pyramid

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ documentation.

2.35 It is intended that all SOs are to be trained in handling calls involving transactions and queries in the ‘general layer’ of the pyramid, while calls categorised as being in the ‘assisted’ or ‘managed and intensive’ layers would be dealt with by a subset of SOs with skill tags indicating more specialised skills.76

2.36 In recent years, the department has increasingly employed Intermittent and Irregular employees 77 (IIEs). At June 2014, 902 full-time equivalent IIEs were employed comprising 26 per cent of the front-line staff providing Centrelink telephone services. The IIE workforce, employed at the APS 3 classification, has assisted with the implementation of the Skills Pyramid as they are trained, and undertake work, in the ‘general’ layer. The ongoing workforce, generally at the APS 4 classification, while also able to complete transactions in the ‘general’ layer, focuses on the more complex work in the ‘intensive’ and ‘assisted’ layers of the pyramid.

2.37 ANAO visits to Smart Centres during the audit indicated that the Skills Pyramid was still in the implementation phase. The ANAO observed that many IIE staff were in the process of being trained in transactions in the ‘general’ layer (putting considerable strain on training and technical support resources) while some ongoing staff were still only skill tagged in their traditional specialist area based on customer segment/payment type. A majority of Smart Centre managers interviewed were of the view that the Skills Pyramid had the potential to organise call distribution more efficiently and therefore to assist in reducing call wait times. Some ongoing staff interviewed by the ANAO, however, pointed to problems that can arise if IIE staff do not have a broad contextual understanding of the interrelationships between various payments and allowances.78 Ongoing staff also commented on their experience of receiving high rates of transfers of calls from IIE staff, who did not have the skills or delegations necessary to complete certain calls.

|

Case Study – Benefits of Skills Pyramid: Indigenous Australian and Income Management Telephony |

|

The introduction of the Skills Pyramid and the general layer has led to improvements in the telephony performance for the Indigenous Australian, Income Management and BasicsCard business lines. Staff servicing the Indigenous Australian telephone line need to maintain a broad range of skills as calls to this line can be about any Centrelink payment or service including Income Management and the BasicsCard (even though these services have their own separate telephone lines). The expansion of Income Management led to increased Income Management and BasicsCard calls on both the Indigenous Australian telephone line and the specialist Income Management and BasicsCard lines—resulting in longer wait times and higher rates of abandoned calls. Human Services was able to direct simple queries about the BasicsCard to staff answering calls in the General layer of the Skills Pyramid. This recent development enabled staff servicing the Indigenous Australian and Income Management and BasicsCard lines to focus on more complex work. Human Services advised that initial results from this change showed an improvement in telephony performance for the Indigenous Australian and Income Management and BasicsCard telephone lines including a decrease in the average speed of answer. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services documentation.

Managed Telecommunications Services

2.38 In October 2012, the department entered into a five year contract with Telstra for telephony services—the Managed Telecommunications Services Contract (the MTS). The department advised the Senate at that time that the MTS had the potential to reduce call wait times by, amongst other things, improving capacity to distribute workloads, enabling the use of speech analytics to assist in analysing why customers call, and better queue management at the national level.79

2.39 The MTS is yet to deliver these benefits for Centrelink calls due, in large part, to the department’s higher priority to migrate Medicare and Child Support programs to the new telecommunications platform. However, the department advised that this migration work and many of the other capabilities enabled by the MTS will become available over the course of 2015. Several of these capabilities have significant potential to assist in reducing call wait times or alleviating the impact of wait times on customers. These capabilities include: a new workforce management system (which will replace the existing tool for forecasting call demand and matching rostering of staff); call recording and speech analytics (this can assist in investigating the factors driving call demand); voice biometrics which aims to reduce the effort for customers to authenticate when they call the department; an enhanced call back facility where the customer may request a call back for a specified time; the capacity to deliver any call to any appropriately skilled staff member anywhere across the department; and a more sophisticated IVR system which, for example, could provide a ‘progress of claim’ self-service option. 80

Digital Strategy

2.40 A key plank in the department’s approach to reducing call wait times is to shift customers from telephone services to self-service digital channels. Both online transactions and the use of mobile apps have increased strongly over the past three years (see Table 1.2 in Chapter 1). However, the growth in digital transactions has not reduced the demand for call services as anticipated. The department’s experience is consistent with wider international trends, and a recent global benchmarking report observed that ‘the emergence of multichannel customer management is fuelling growth within the contact centre industry, not curtailing it’. 81 Part of the explanation for this trend is the unreliability and difficulty of using some digital applications. International experience indicates that some 40 per cent of calls to contact centres are now made because of a failed self-service interaction; a noteworthy trend given the expectations of improved service delivery and efficiencies offered by self-service channels.82 In effect, customers are using Smart Centres as a ‘help desk’ for digital channels, and at this stage it is not known whether this trend is likely to be transitional or ongoing.

2.41 The department is currently developing a draft digital strategy. The draft strategy acknowledges the linkages with other channels and the need to align overall strategy with the Smart Centres operating model. There is a focus in the draft strategy on improving the reliability and ease of use of digital transactions and expanding the range of transactions that can be completed digitally. Improvements in digital service channels can be expected to assist in reducing call demand, call wait times and related costs for customers and the department.

A coordinated channel strategy

2.42 In April 2006, the Australian Government Information Management Office (AGIMO) released the guide Delivering Australian Government Services: Managing Multiple Channels. The guide emphasised the importance of entities establishing a channel strategy to manage service delivery to their clients through the most appropriate channels. A channel strategy is a ‘set of business driven choices aimed at delivering services to customers efficiently and effectively using the most appropriate mix of channels for the customer and the agency’.83 AGIMO identified the following benefits of a channel strategy: