Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Digital Transformation Agency’s Procurement of ICT-Related Services

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit was conducted to provide: increased transparency over the Digital Transformation Agency’s (DTA’s) procurement framework; assurance that the DTA’s procurement of ICT-related services is being conducted effectively; and assurance that the DTA is effectively managing contracts to deliver on intended objectives and achieve value for money.

Key facts

- The DTA is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity and is subject to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

- The ANAO examined nine DTA procurements with published start dates in 2019–20 and 2020–21, with a combined reported value of $54.5 million. Of these: one was an open tender; seven were panel procurements (including four where the DTA approached one supplier off the panel); and one was a limited tender.

What did we find?

- The DTA's procurement of ICT-related services has been ineffective for the nine procurements examined by the ANAO.

- The DTA has established a procurement framework, but its implementation and oversight has been weak.

- For the procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA did not conduct the procurements effectively and its approach fell short of ethical requirements.

- For the procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA has not managed contracts effectively.

What did we recommend?

- There were eight recommendations to the DTA aimed at improving compliance with the CPRs and ensuring officials have a sufficient understanding of procurement requirements.

- There was one recommendation to the Australian Government aimed at improving transparency on the reporting of panel procurements by Australian Government entities.

$122.8m

DTA expenses for procuring goods and services from suppliers in 2019–20 and 2020–21.

4

Number of the DTA’s five highest value procurements in 2019–20 and 2020–21 that involved an approach to only one supplier.

40 times

Increase in contract value (over two years) for one direct-approach procurement examined — from $121,000 to almost $5 million.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) was established in October 2016, absorbing the former Digital Transformation Office, which had been established in March 2015. In April 2021, the DTA moved to the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio and its mandate was updated. In July 2022, the DTA moved to the Finance portfolio. The DTA’s 2021–22 corporate plan describes its priorities as: 1) direction setting — being a trusted advisor on digital and ICT investment decisions and driving strategic whole-of-government digital policy and advice; and 2) implementation oversight — ensuring alignment to digital strategies and priorities and simplifying digital procurement to reduce costs and increase reuse.

2. Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), an entity’s accountable authority has a duty to promote the proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use and management of public resources. Under the PGPA Act, the Finance Minister issues the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) for officials to follow when performing duties in relation to procurement.1 The CPRs govern how entities buy goods and services and are designed to ensure the government and taxpayers get value for money.

3. Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs, which requires ‘the consideration of financial and non-financial costs and benefits associated with procurement’.2 The CPRs state that ‘Officials responsible for a procurement must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome’.

4. After a procurement has been undertaken and a contract awarded, an entity needs to manage the contract. Contract management includes establishing contract management arrangements, managing contract performance, ensuring objectives are met and value for money is achieved, and reporting on contracts and variations.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. Procurement is a core function of the DTA. This audit was conducted to provide: increased transparency over the DTA’s procurement framework; and assurance to the Parliament that the DTA’s procurement of ICT-related services is being conducted effectively and that the DTA is effectively managing contracts to deliver on intended objectives and achieve value for money.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the DTA’s procurement of ICT-related services.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Has the DTA established a sound procurement framework?

- Has the DTA conducted procurements effectively?

- Has the DTA managed contracts effectively?

8. The audit scope did not include the establishment of whole of Australian Government arrangements, which are set up for Commonwealth entities to use when procuring certain goods or services. These are either coordinated or cooperative procurements, some of which are mandatory for use, and generally result in overarching contracts or panel arrangements. The audit scope also did not include the establishment of ICT-related panels, such as the Digital Marketplace panel, which was the subject of an ANAO audit in 2020.3

9. The ANAO examined a sample of nine procurements for ICT-related services undertaken by the DTA with a published start date between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2021. The nine procurements were selected for review on the basis of value, risk, relevance and type of procurement and included seven of the DTA’s nine highest value procurements over this period (excluding whole-of-government procurements). As most of the DTA’s ICT-related services are procured through the Digital Marketplace panel, seven of the procurements selected for examination were undertaken through this panel (which was established through an open tender). In addition, the ANAO selected one procurement that was conducted as an open tender and one that was conducted as a limited tender. The selected procurements range in value from $127,334 to $28.1 million.

10. The period within the audit scope includes the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pace of the Australian Government’s response to the pandemic increased the risks involved in procurements, particularly where procurements were undertaken on shortened timeframes or transferred from one entity to another.

Conclusion

11. The DTA’s procurement of ICT-related services has been ineffective for the nine ICT-related procurements examined by the ANAO.

12. The DTA has established a procurement framework, but its implementation and oversight has been weak. The DTA has Accountable Authority Instructions and procurement policies and guidance that align with relevant aspects of the finance law. However, the DTA has not been following its internal policies and procedures, and there are weaknesses in its governance, oversight and probity arrangements for procurements.

13. For the nine ICT-related procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA did not conduct the procurements effectively and its approach fell short of ethical requirements.4 None of these procurements fully complied with the CPRs. The DTA did not conduct approach to market or tender evaluation processes effectively, and it did not consistently provide sound advice to decision-makers. The DTA’s frequent direct sourcing of suppliers using panel arrangements does not support the intent of the CPRs including the achievement of value for money.

14. For procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA has not managed contracts effectively. The DTA has not established effective contract management arrangements. While its contracts include performance expectations, the DTA has not effectively monitored performance against these expectations. The DTA has not effectively managed contracts to deliver against the objectives of the procurements and to achieve value for money. Its management of one of the examined procurements fell particularly short of ethical requirements, with the DTA changing the scope and substantially increasing the value of the contract through 10 variations.

Supporting findings

Procurement framework

15. The DTA has established a procurement framework that aligns with the CPRs and the PGPA Act. This framework includes Accountable Authority Instructions with clear guidance on the duties of officials when conducting a procurement, and policies and guidance on key aspects of procurement. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.7)

16. The DTA has established governance and oversight arrangements for procurements, but there are weaknesses in these arrangements. The DTA’s Executive Board has had limited oversight of procurement risks. While the DTA has sound guidance on risk and fraud management, this guidance has not been systematically applied for procurements examined in this audit. Completion rates for fraud awareness and procurement training are low, and a 2019 internal audit found issues with procurement that have not been addressed. (See paragraphs 2.8 to 2.48)

17. For procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA has not followed its internal probity guidelines, including requirements for declaring activity-specific conflicts of interest. The DTA’s policies and practices regarding receiving gifts and benefits did not meet whole-of-government requirements. (See paragraphs 2.49 to 2.78)

Procurement activity

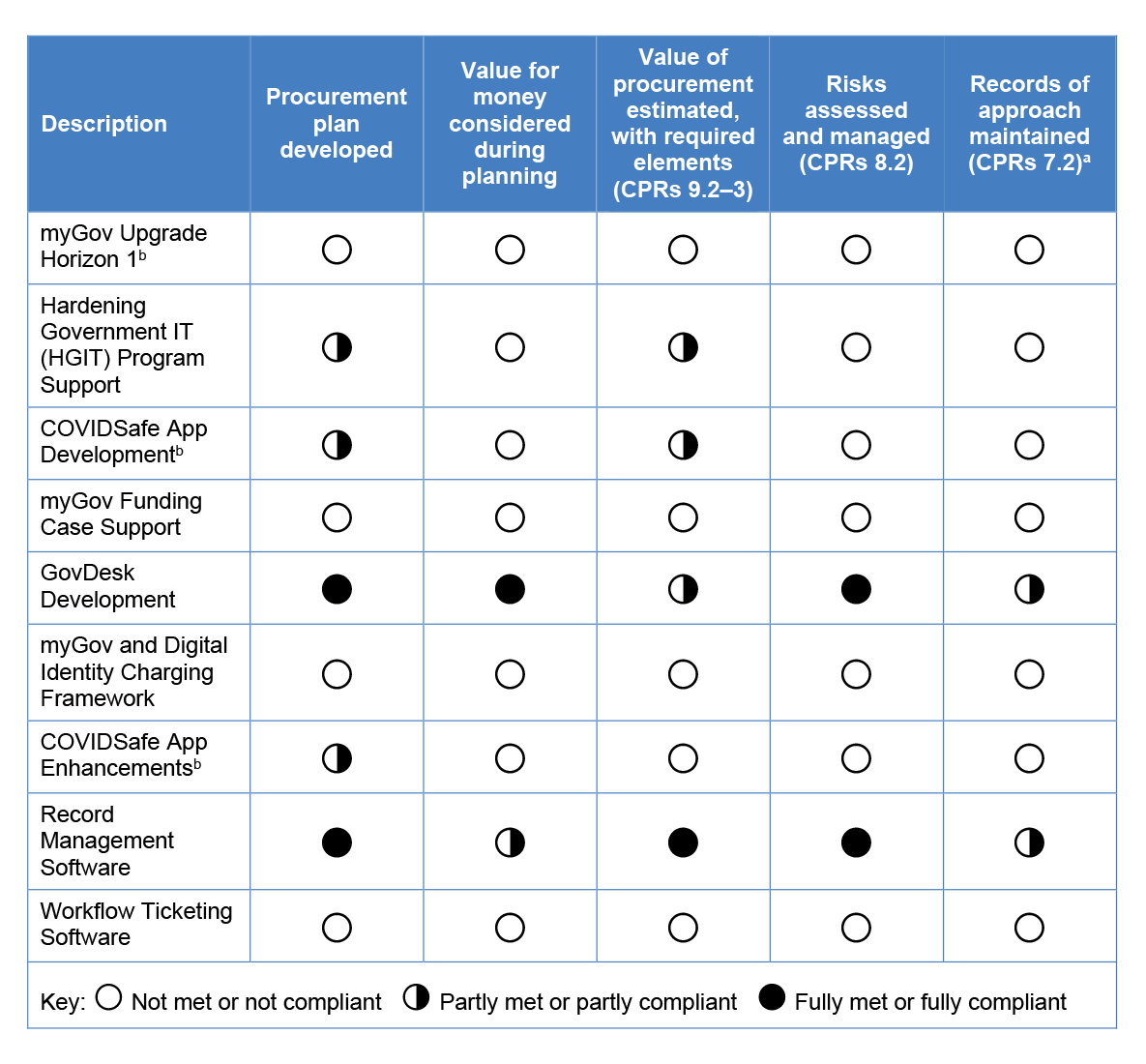

18. The DTA did not conduct approach to market processes effectively for procurements examined by the ANAO. Procurements did not comply with CPR requirements to: estimate the value of the procurement prior to determining the procurement approach; assess risks to the procurement; and maintain appropriate records of the approach to market. Further, the DTA’s frequent direct sourcing of suppliers using panel arrangements such as the Digital Marketplace does not support the intent of the CPRs. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.44)

19. For procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA did not conduct tender evaluation processes effectively. Evaluation plans were not consistently prepared, and evaluations did not consistently use fit-for-purpose evaluation criteria. None of the examined procurements fully complied with CPR requirements to: consider value for money; notify unsuccessful tenderers of the outcomes of procurements; and maintain appropriate records of the approach to market. (See paragraphs 3.46 to 3.65)

20. The DTA did not consistently provide sound advice to decision-makers. Advice generally did not include whether selected tenderers would achieve value for money or how risks were considered. Advice usually included information on the whole-of-life value and total contract amount, the method used to request quotes from suppliers, scoring from evaluations and the rationale for the recommended supplier. (See paragraphs 3.66 to 3.76)

Contract management

21. The DTA has not established effective contract management arrangements for the procurements examined by the ANAO. None of the nine procurements had a contract management plan. The DTA did not consistently report contract variations to AusTender within 42 days or with the correct value. All nine procurements had issues with the timeliness of payments, and there were weaknesses in the DTA’s internal payment controls that led to duplicate payments being made. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.24)

22. Contracts for procurements examined by the ANAO generally included performance expectations, but the DTA has not been effectively monitoring performance against these expectations. The DTA has not been consistently documenting its performance monitoring activities or its verification of services delivered. (See paragraphs 4.25 to 4.31)

23. For the procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA has not managed contracts effectively to deliver against the objectives of the procurements and to achieve value for money. Value for money was not adequately considered for contract variations relating to the procurements. The DTA varied seven of the nine procurements examined by the ANAO. In one case, a directly sourced contract was ‘leveraged’ multiple times, increasing in value by 40 times with substantial changes to scope. Varying a contract in this way is not consistent with ethical requirements. (See paragraphs 4.32 to 4.42)

Recommendations

24. This report makes nine recommendations: one directed to the Australian Government; and eight directed to the Digital Transformation Agency.

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.31

The Digital Transformation Agency implement a system of risk management that ensures procurement risks are being monitored, managed and escalated appropriately.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.45

The Digital Transformation Agency:

- implement a strategy to ensure all officials complete its fraud awareness and mandatory procurement and finance training; and

- strengthen its processes to ensure that potential fraud and probity breaches are investigated in accordance with its policies and that appropriate follow-up action is taken.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.68

The Digital Transformation Agency:

- establish an internal control to ensure that officials directly involved in procurements make activity-specific declarations of interest; and

- maintain a register of declared interests.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.33

The Digital Transformation Agency align its approach to market processes with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, with a focus on:

- estimating the expected value of a procurement before a decision on the procurement method is made;

- establishing processes to identify, analyse, allocate and treat risk; and

- maintaining a level of documentation commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.44

The Australian Government implement reporting requirements for procurements from standing offers, such as panels, to provide transparency on whether an opportunity was open to all suppliers and, if not, how many suppliers were approached.

Department of Finance response: Noted.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.65

The Digital Transformation Agency improve its tender evaluation processes to:

- align them with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules; and

- incorporate evaluation criteria to better enable the proper identification, assessment and comparison of submissions on a fair and transparent basis.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.76

The Digital Transformation Agency improve its procurement processes to ensure decision-makers are provided complete advice, including information on risk and how value for money would be achieved.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.24

The Digital Transformation Agency:

- improve its training and management of internal payment controls; and

- conduct an internal compliance review or audit within the next 12 months to verify the effectiveness of its payment controls.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 4.42

The Digital Transformation Agency strengthen its internal guidance and controls to ensure officials do not vary contracts to avoid competition or obligations and ethical requirements under the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

Digital Transformation Agency

The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) welcomes this review and agrees with the ANAO’s focus on providing increased transparency over the DTA’s internal procurement framework with a view to ensuring contracts are managed effectively and value for money is achieved.

While the audit report identifies shortfalls in relation to internal procurement processes, controls and education, each of the sampled procurements still achieved their intended outcomes and supported critical delivery requirements in an unprecedented pandemic environment.

The DTA has established a procurement framework that aligns with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). It has been designed for and remains committed to achieving value for money in ways that are efficient, effective, economical and ethical.

To further strengthen the framework internally and how the agency conducts its procurements, the DTA accepts all identified opportunities for improvement and agrees with each of the eight recommendations (1-4, 6-9) as proposed in the Report.

DTA is already actively working to address all recommendations and has introduced additional controls that will assist in driving the required uplift and strengthening of its procurement processes, overarching contract management, probity, and conflicts of interest posture.

Department of Finance

Finance notes [Recommendation 5]. Finance will consider options for entities to report on how many suppliers have been approached from a standing offer arrangement, and options to enhance functionality for reporting contract notices from standing offers in future updates to AusTender.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages that have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance

Procurement

Contract management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Procurement is the process of acquiring goods and services. Procurement of goods and services is integral to the conduct of Australian Government activity and a core function of the Commonwealth public sector.

1.2 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), an entity’s accountable authority has a duty to promote the proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use and management of public resources. Under the PGPA Act, the Finance Minister issues the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) for officials to follow when performing duties in relation to procurement.5 The CPRs govern how entities buy goods and services and are designed to ensure the government and taxpayers get value for money. The CPRs state:

[Procurement] begins when a need has been identified and a decision has been made on the procurement requirement. Procurement continues through the processes of risk assessment, seeking and evaluating alternative solutions, and the awarding and reporting of a contract.6

1.3 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs, which requires ‘the consideration of financial and non-financial costs and benefits associated with procurement’.7 The CPRs state that ‘Officials responsible for a procurement must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome’ and that procurements should:

- encourage competition and be non-discriminatory;

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth;

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision making;

- encourage appropriate engagement with risk; and

- be commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.8

1.4 The CPRs are supported by tools such as the AusTender reporting system, guidance material and templates developed and maintained by the Department of Finance (Finance).

Procurement methods

1.5 There are two main procurement methods: open tender and limited tender.

- Open tender involves publishing an open approach to market and inviting submissions. This includes multi-stage procurements, provided the first stage (such as setting up a panel) is an open approach to market.9 Open tender is the default for all procurements valued above the relevant threshold.10

- Limited tender involves an entity approaching one or more potential suppliers to make submissions. These can be undertaken for any procurement under the relevant threshold where it represents value for money. For procurements above the relevant threshold, limited tender can only be used where it is specifically allowed by the CPRs, and the reasons for the limited tender must be reported on AusTender.

1.6 A standing offer arrangement, such as a panel arrangement, can be established through an open tender or limited tender process. Panel arrangements are a way to procure goods or services regularly acquired by entities. In a panel arrangement, suppliers have been appointed to supply goods or services for a set period of time under agreed terms and conditions. Once a panel has been established, an entity may approach one or more suppliers to seek a quote for a particular procurement. Finance’s guidance on panel procurements states:

Wherever possible, you should approach more than one supplier on a Panel for a quote. Even though value for money has been demonstrated for the supplier to be on a panel, you will still need to demonstrate value for money when engaging from a Panel, and competition is one of the easier ways to demonstrate this.11

Contract management

1.7 After a procurement has been undertaken and a contract awarded, an entity needs to manage the contract. Finance states that ‘good contract management is an essential component in achieving value for money’ and defines contract management as:

all the activities undertaken by an entity, after the contract has been signed or commenced, to manage the performance of the contract (including any corrective action) and to achieve the agreed outcomes.12

1.8 Finance’s guidance on contract management states: ‘When managing contracts, officials operate in a complex environment of legislation and Commonwealth policy’. This includes but is not limited to: the PGPA Act; the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014; the CPRs; Accountable Authority Instructions; and resource management guides (RMGs) (such as RMG 400 Commitment of Relevant Money, RMG 411 Grants, Procurements and Other Financial Arrangements and RMG 417 Supplier Pay On-Time or Pay Interest Policy).13

1.9 Contract management includes establishing contract management arrangements, managing contract performance, ensuring objectives are met and value for money is achieved, and reporting on contracts and variations.

Digital Transformation Agency

1.10 The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) was established in October 2016, absorbing the former Digital Transformation Office, which had been established in March 2015. In April 2021, the DTA moved to the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio and its mandate was updated. In July 2022, the DTA moved to the Finance portfolio. The DTA’s purpose and priorities have changed over this period — from a focus on delivering ICT-related programs in 2019–20 to a focus on providing ICT investment advice and oversight in 2021–22 (as shown in Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: DTA purpose and priorities, 2019–20 to 2021–22

|

|

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

|

Purpose |

We lead digital transformation in government to make services simple, smart and user-focused. |

Simple, clear and fast public services. |

Provide strategic and policy leadership and investment advice and oversight to drive government digital transformation that delivers benefits to all Australians. |

|

Priorities |

Deliver whole-of-government strategies, policies and advice to support the Government’s digital and ICT agenda. Design, deliver and support common, government-wide platforms and services that enable digital transformation. Deliver a program of digital and ICT capability improvement, including sourcing, to enhance capability and skills across the Australian Public Service (APS). Drive collaboration and partnerships to enable and accelerate he digital transformation of government services. |

Lead whole-of-government digital and ICT strategies, policies and advice that enable modern, efficient and joined-up services. Coordinate and drive common platforms, technologies and services that enhance user experiences by making government simple, clear and fast. Build the digital profession to enhance digital and ICT skills and capabilities across the APS. Collaborate and partner, both nationally and internationally, to accelerate the digital transformation of government services. |

Direction setting: We are a trusted advisor on digital and ICT investment decisions; We drive strategic whole-of-government digital policy and advice. Implementation oversight: We ensure alignment to digital strategies and priorities; We simplify digital procurement to reduce costs and increase reuse. |

Source: ANAO analysis of DTA Corporate Plans for 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22.

DTA’s procurement activities

1.11 The DTA spends most of its budget through procurement. In 2020–21, the DTA’s expenses were $119.9 million, of which $77.6 million (65 per cent) was used for procuring goods and services from suppliers, as shown in Table 1.2. The profile of the DTA’s procurement activities has changed since DTA’s mandate changed in 2021–22, with the DTA moving away from the direct delivery of ICT projects.

Table 1.2: DTA expenses, including expenses for procuring goods and services from suppliers, 2019–20 and 2020–21

|

Expenses |

2019–20 $’000 |

2020–21 $’000 |

|

Suppliers (procuring goods and services) |

45,158 |

77,613 |

|

Employee benefits |

32,262 |

36,645 |

|

Othera |

4,941 |

5,622 |

|

Total expenses |

82,361 |

119,880 |

Note a: Depreciation and amortisation, impairment loss on financial instruments, write-down and impairment of other assets and finance costs.

Source: ANAO analysis of DTA Annual Reports for 2019–20 and 2020–21.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.12 Procurement is a core function of the DTA. This audit was conducted to provide: increased transparency over the DTA’s procurement framework; and assurance to the Parliament that the DTA’s procurement of ICT-related services is being conducted effectively and that the DTA is effectively managing contracts to deliver on intended objectives and achieve value for money.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.13 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the DTA’s procurement of ICT-related services.

1.14 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Has the DTA established a sound procurement framework?

- Has the DTA conducted procurements effectively?

- Has the DTA managed contracts effectively?

1.15 The audit scope did not include the establishment of whole of Australian Government arrangements that are set up for Commonwealth entities to use when procuring certain goods or services. These are either coordinated or cooperative procurements, some of which are mandatory for use, and generally result in overarching contracts or panel arrangements. The audit scope also did not include the establishment of ICT-related panels, which was the subject of an ANAO audit in 2020.14

Procurements examined in this audit

1.16 The ANAO examined a sample of nine procurements for ICT-related services undertaken by the DTA with a published start date between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2021. The nine procurements were selected based on value, risk, relevance and type of procurement and included seven of the nine highest value procurements (excluding whole-of-government procurements). As most of the DTA’s ICT-related services are procured through the Digital Marketplace panel, seven of the procurements selected for examination were undertaken through this panel (which was established through an open tender).15 In addition, the ANAO selected one procurement that was conducted as an open tender and one that was conducted as a limited tender. The selected procurements range in value from $127,334 to $28.1 million — with a total value of $54.5 million, as shown in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Nine procurements examined during this audit, by value

|

Procurement |

Description |

Method |

Start date |

Value as at July 2022 |

|

myGov Upgrade Horizon 1a (CN3678817) |

Enhancements to the myGov portal, intended to make it easier to access government services and information. Direct approach. Contract awarded to Deloitte Consulting Pty Ltd Australia (Deloitte). |

Digital Marketplace Panel (Open Tender)

|

23 Mar 20 |

$28,130,966 |

|

Hardening Government IT (HGIT) Program Support (CN3743099) |

Support for the delivery of the HGIT program, intended to improve cyber security. Initial approach to 16 suppliers. Second direct approach. Contract awarded to CyberCX Pty Ltd (CyberCX). |

4 Jan 21 |

$8,515,313 |

|

|

COVIDSafe App Developmenta (CN3669719) |

Development of the COVIDSafe App, a COVID-19 contact tracing app. Direct approach. Contract awarded to Delv Pty Ltd (Delv). |

30 Mar 20 |

$6,069,929 |

|

|

myGov Funding Case Support (CN3698013) |

Drafting of funding case documentation for myGov Horizon 2 stream. Direct approach. Contract awarded to Nous Group Australia (Nous Group). |

25 May 20 |

$4,942,080 |

|

|

GovDesk Development (CN3628140) |

Development of a secure cloud-based desktop environment (GovDesk). 17 suppliers approached. Contract awarded to Oobe Pty Ltd (Oobe). |

4 Sep 19 |

$2,327,863 |

|

|

myGov and Digital Identity Charging Framework (CN3781425) |

Development of a Digital Identity Charging Framework and a pricing review for MyGov. Four suppliers approached. Contract awarded to ConceptSix Pty Ltd (ConceptSix). |

7 Jun 21 |

$2,281,077 |

|

|

COVIDSafe App Enhancementsa (CN3716937) |

Support for the development and enhancement of the COVIDSafe App. Nine suppliers approached. Contract awarded to Shine Solutions Group Trust (Shine Solutions Group). |

|

10 Aug 20 |

$1,440,892 |

|

Record Management Software (CN3752974) |

Record Management Software. Approach to the open market. Contract awarded to Recordpoint Software APAC Pty Ltd (Recordpoint). |

Open Tender |

2 Mar 21 |

$522,000 |

|

Workflow Ticketing Software (CN3717154) |

Workflow Ticketing Software for the DTA. Direct approach. Contract awarded to Zendesk Pty Ltd (Zendesk). |

Limited Tender |

14 Sep 20 |

$127,334 |

|

Total |

$54,357,454 |

|||

Note a: This procurement related to the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: ANAO analysis of DTA and AusTender data.

1.17 The period within the audit scope includes the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pace of the Australian Government’s response to the pandemic increased the risks involved in procurements, particularly where procurements were undertaken on shortened timeframes or transferred from one entity to another. Three of the nine procurements in the ANAO’s sample relate to the Australian Government’s response to the pandemic: myGov Upgrade Horizon 1; COVIDSafe App Development; and COVIDSafe App Enhancements. Paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs states that the CPRs do not apply to the extent that an official applies measures determined by their accountable authority to be necessary for the protection of human health. The DTA did not set aside the CPRs under paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs for any of the nine procurements.

1.18 As shown in Table 1.4, the value of the procurements in the ANAO’s sample represents approximately 44 per cent of the DTA’s procurement expenses during 2019–20 and 2020–21 (not including procurements through the ICT Coordinated Procurement Special Account16, which were out of the audit scope).

Table 1.4: Value of procurements in the ANAO sample as a percentage of total DTA procurement expenses

|

DTA Expenses |

2019–20 $’000 |

2020–21 $’000 |

Total for 2019–20 and 2020–21 $’000 |

Value and % of ANAO sampled procurements $’000 |

|

Suppliers (procuring goods and services) |

45,158 |

77,613 |

122,771 |

54,357 (44%) |

Source: ANAO analysis of DTA Annual Reports for 2019–20 and 2020–21 and AusTender data.

Audit methodology

1.19 To address the audit criteria and achieve the audit objective, the audit team:

- examined relevant DTA and AusTender documentation;

- conducted meetings with DTA senior officials and officials involved in the procurement framework and procurement activities; and

- discussed elements of the audit relating to Australian Government procurement policy and guidelines with the Department of Finance.

1.20 In addition to a draft audit report being provided to the DTA, extracts of the draft audit report were provided to: the Department of Finance; ConceptSix; CyberCX; Delv; and Nous Group. Formal responses were provided to the ANAO by the DTA, the Department of Finance and CyberCX (see Appendix A).

1.21 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $442,000.

1.22 The team members for this audit were Jennifer Eddie, Elizabeth Robinson, Sam Jones, Graeme Corbett, Grace Sixsmith, Christine Chalmers and Daniel Whyte.

2. Procurement framework

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) has established a sound procurement framework.

Conclusion

The DTA has established a procurement framework, but its implementation and oversight has been weak. The DTA has Accountable Authority Instructions and procurement policies and guidance that align with relevant aspects of the finance law. However, the DTA has not been following its internal policies and procedures, and there are weaknesses in its governance, oversight and probity arrangements for procurements.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: strengthening the DTA’s management of procurement risks and probity issues; strengthening its processes for investigating potential fraud and probity breaches and increasing fraud awareness and procurement training; and improving its processes for declaring interests.

The ANAO also identified three opportunities for improvement, which relate to: strengthening probity guidelines; providing training on identifying and avoiding conflicts of interest; and publishing a register of gifts and benefits received by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO).

2.1 This chapter examines whether the DTA has established a sound procurement framework. A procurement framework includes procurement instructions, policies and guidance and is supported by governance, oversight and probity arrangements. A sound framework helps ensure that: procurements are undertaken effectively, ethically and in compliance with relevant rules and legislation; entities properly use and manage public resources; and procurements achieve their objectives and value for money outcomes.

Has the DTA established a procurement framework that aligns with the CPRs and the PGPA Act?

The DTA has established a procurement framework that aligns with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). This framework includes Accountable Authority Instructions with clear guidance on the duties of officials when conducting a procurement, and policies and guidance on key aspects of procurement.

Accountable Authority Instructions

2.2 Section 20A of the PGPA Act states: ‘the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity may, by written instrument, give instructions to an official of the entity about any matter relating to the finance law’. The Department of Finance (Finance) provides further guidance in its Resource Management Guide (RMG) 206 on Accountable Authority Instructions.17

2.3 The DTA has established Accountable Authority Instructions that align with the requirements of section 20A of the PGPA Act and with RMG 206. Two versions of the Accountable Authority Instructions were in place during the period examined by the audit – one was approved by the CEO in September 2018 and the second in May 2021. Both versions of the instructions stated the key duties and responsibilities of officials under the PGPA Act, including:

- requirements for entering into commitments of relevant money (section 23); and

- the general duties of officials (sections 25 to 29), such as the duties: of care and diligence; to act honestly, in good faith and for a proper purpose; in relation to use of position; in relation to use of information; and to disclose interests.

2.4 The May 2021 version of the Accountable Authority Instructions included clearer references to requirements under the PGPA Act relating to:

- the proper use and management of public resources (section 15); and

- establishing appropriate systems of risk management and internal control (section 16).

2.5 Both versions of the Accountable Authority Instructions stated that all officials undertaking a procurement must: comply with the CPRs, PGPA Act and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule); treat all potential suppliers to government equitably; act ethically throughout a procurement; and not seek to obtain benefit from supplier practices that may be dishonest, unethical or unsafe.

Procurement policies and guidance

2.6 The DTA has established other procurement policies and guidance to assist staff with understanding their duties and procurement processes, such as:

- finance policies on simple and medium procurement, panel procurement and limited tender procurement;

- PGPA Act operational guidelines;

- intranet pages on procurement processes, delegations, risk management and contract management;

- a Probity Guideline and Declaration of Interest Policy; and

- a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan.

2.7 These policies and guidance were largely appropriate and available to staff on the DTA intranet.18 The application of the DTA’s procurement policies and instructions are discussed, where relevant, throughout this report.

Has the DTA established sound governance and oversight arrangements for procurements?

The DTA has established governance and oversight arrangements for procurements, but there are weaknesses in these arrangements. The DTA’s Executive Board has had limited oversight of procurement risks. While the DTA has sound guidance on risk and fraud management, this guidance has not been systematically applied for procurements examined in this audit. Completion rates for fraud awareness and procurement training are low, and a 2019 internal audit found issues with procurement that have not been addressed.

2.8 In its Annual Report 2020–21, the DTA described its governance framework as including (in addition to policies and instructions and corporate and business planning): governance committees (Executive Board and Audit Committee); risk and fraud management; and internal audit and assurance activities.

Executive Board

2.9 The Executive Board is the DTA’s primary governance forum. It meets monthly and comprises the senior leadership team. According to its terms of reference, the Executive Board is to determine strategic direction, manage overall performance, and provide advice on the administration and operations of the DTA, including, but not limited to, the:

- development and implementation of systems, processes, and internal controls for the management of the DTA’s risks;

- consideration of investment proposals;

- prioritisation and allocation of resources; and

- changes to scope, schedule and budget for internal mandates.

2.10 The Executive Board receives updates on DTA programs and projects on an ad hoc basis, which includes those undertaken through contracts with suppliers.

2.11 In 2020–21, the Executive Board did not consider procurements or provide advice on managing procurement risk. The DTA’s 2020–21 Corporate Plan stated that the DTA actively manages risks at its Executive Board meetings. However, risk management was not included as an agenda item for any of the Executive Board meetings in 2020–21.

2.12 From September 2021 the Board added a standing agenda item on ‘DTA governance and oversight’, which was intended to include discussions on ‘strategy, people and risk management’.

- At the September 2021 meeting, under this item, the Executive Board: discussed the development of strategic and organisational risk management processes; decided to run a risk management session to identify significant strategic and organisational risks; and agreed to include regular risk management updates in future meetings. This discussion resulted in the following action item: ‘The Board undertake a strategic and organisational risk assessment process and report back against it on a regular basis’.

- At the next meeting in October 2021 there was a ‘nil’ report under the new agenda item on governance and oversight. The meeting papers recommended that the risk management action item be closed, with the update: ‘A strategic and operational risk assessment was performed and included in the final version of the Corporate Plan published end of August 2021’.19

2.13 The standing agenda item on governance and oversight remained on the agenda, but there was no evidence that risk management was discussed at the five meetings between November 2021 and March 2022. At the April 2022 meeting, there was an additional agenda item on the ‘DTA Strategic Risk Assessment Review’, and a paper was provided that outlined five strategic risks with related controls and treatments. This was the first evidence of substantive consideration of risk by the DTA’s Executive Board during the period examined by this audit. None of the five strategic risks outlined in the paper related to procurement of ICT-related services.

Audit Committee

2.14 Section 17 of the PGPA Rule states that an accountable authority ‘must, by written charter, determine the functions of the audit committee for the entity’ and these functions must include reviewing the appropriateness of the entity’s: financial and performance reporting; system of risk oversight and management; and system of internal control.

2.15 The DTA’s Audit Committee Charter includes the functions required under the PGPA Rule, and states that the audit committee will meet at least four times each year. The audit committee met: five times in 2019–2020; and five times in 2020–21.21

2.16 The Audit Committee Charter indicates that the committee will review and provide advice on the appropriateness of the DTA’s: risk management framework; articulation of key roles and responsibilities relating to risk management; and approach to managing the entity’s key risks, including those associated with projects and program implementation.

2.17 In August 2019, the audit committee reviewed a one-page report on the DTA’s governance, risk and controls, which noted that the following items were ‘in place’ but not yet ‘mature’: first line monitoring and controls; business planning; staff training; control framework; Risk Policy and Framework; and Enterprise Risk Management Plan.

2.18 The June 2021 audit committee papers included a template for branch-level business plans, which included a section on risk. In June 2022, the DTA provided the ANAO with drafts of branch-level business plans that included risks, but as at June 2022, none of the plans for the 2021–22 financial year had been finalised or approved.

2.19 In November 2021, the DTA’s CEO presented his first executive briefing to the audit committee. He discussed risks facing the DTA, such as high staff turnover22, and stated that the DTA needed to revise its strategic risk assessment and corporate planning.

2.20 At the March 2022 audit committee meeting, there was an agenda item on ‘Risk Management’ and the committee was provided with a copy of the 2018 Risk Management Policy23 and a draft strategic risk assessment (with a note that it was under review by the Executive Board). There was no evidence in the Audit Committee papers that the Audit Committee considered or provided advice on risks relating to the procurement of ICT-related services during the period examined by this audit.

Risk management

2.21 Accountable authorities are required under section 16 of the PGPA Act to establish and maintain an appropriate system of risk oversight and management for the entity.

2.22 In 2018 the DTA engaged KPMG Australia to develop a risk management policy, risk management process and enterprise risk report. In 2021–22, the risk management policy and enterprise risk report documents were no longer in use. Elements of the risk management process were still in use.

2.23 As noted at paragraph 2.17, the DTA assessed the status of its governance, risk and controls in 2019 and rated the following items as ‘in place’ but not yet mature:

- Risk Policy and Framework — ‘Developed. Work is required to embed this in product teams’; and

- Enterprise Risk Management Plan — ‘Enterprise risk assessment is complete. Executive Board have asked for this to be included as a standard item’.24

2.24 In its 2019–20 and 2020–21 annual reports, the DTA stated:

We take a risk-based approach to treating sources of risk that may negatively affect our ability to deliver DTA priorities, while remaining open to positive risks and opportunities that support our objectives. Many of our delivery approaches, such as agile and iterative development, help to contain risk and respond quickly to changes in the surrounding environment or to feedback.

2.25 The DTA’s 2021–22 Corporate Plan (published in August 2021) identified five strategic risks — that the DTA would be unable to: provide advice, insights and assurance on whole-of-government digital and ICT investments; lead whole-of-government strategies and policies to drive the government’s agenda; deliver on its funded priorities; enlist the support of its stakeholders to achieve shared outcomes; or attract, retain and develop its people.

2.26 The DTA’s 2021–22 Corporate Plan describes the DTA’s system of risk oversight and management as follows:

We manage risk in line with our Enterprise Risk Framework, the AS/NZS 31000:2018 Risk management – Guidelines, as well as the Commonwealth Risk Management Guidelines. We have efficient and effective controls in place to anticipate and manage risk and drive organisational performance. We actively manage risks continually across our organisation with oversight provided at our Executive Board meetings. We encourage staff to engage with risk appropriately.

2.27 The DTA defines its risk management framework as ‘all policies, procedures and governance structures directly or indirectly guiding our behaviour and actions when managing risk’.

2.28 The DTA had the following risk policies and guidance in place and accessible to staff on the DTA intranet:

- ‘Managing risk’ — an intranet page on identifying, reporting and escalating risk;

- ‘Risk management process’ — an intranet page about the process; and

- a template for a risk and control register, with a risk matrix and guidance on ‘how to conduct a risk assessment’ and ‘how to approach the risk register’.

2.29 Although the DTA has established guidance on risk management, this guidance is not being applied systemically. The DTA had prepared risk assessments for only two of the nine procurements examined for this audit, and neither risk assessment was consistent with DTA guidance on how to assess and rate risks.

2.30 In 2021–22, no enterprise risk plan or framework was available to staff on the DTA intranet. In March 2022, the DTA advised the ANAO that it did not currently have central or business level risk registers. In June 2022, the DTA provided the ANAO with a copy of a risk register that it stated had been in use in 2019. All of the risks listed had due dates in 2019 and there was no evidence that the register had been updated since that time. Having a central risk register or registers by division or branch that are accessible to staff would enable the DTA to better manage, and assign responsibility for, key risks.

Recommendation no.1

2.31 The Digital Transformation Agency implement a system of risk management that ensures procurement risks are being monitored, managed and escalated appropriately.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Fraud management

2.32 Section 10 of the PGPA Rule states that an accountable authority must take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity, including by:

- conducting fraud risk assessments regularly and when there is a substantial change in the structure, functions or activities of the entity;

- developing and implementing a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks as soon as practicable after conducting a risk assessment;

- having an appropriate mechanism for preventing fraud, including by ensuring that officials of the entity are made aware of what constitutes fraud, and the risk of fraud is taken into account in planning and conducting the activities of the entity; and

- having an appropriate mechanism for detecting incidents of fraud or suspected fraud, investigating or otherwise dealing with incidents of fraud or suspected fraud, and recording and reporting incidents of fraud or suspected fraud.

2.33 In its annual reports for 2019–20 and 2020–21, the DTA’s CEO certified that:

in accordance with sections 10 and 17AG of the PGPA Rule, the Digital Transformation Agency has prepared a fraud risk assessment and a fraud control plan, and has in place appropriate fraud prevention, detection, investigation and reporting mechanisms and has taken all reasonable measures to appropriately deal with fraud related to our agency.

2.34 The DTA has a section on fraud control in its Accountable Authority Instructions and has established a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. The plan outlines the DTA’s approach to fraud control, which includes (but is not limited to):

- maintaining an effective system of internal controls to protect public money, information and property;

- ensuring all DTA officials are aware of their obligations in relation to fraud through fraud awareness training;

- conducting periodic fraud risk assessment reviews;

- establishing formal procedures for reporting and investigating allegations of dishonest and/or fraudulent behaviour; and

- investigating fraud in accordance with the Australian Government Investigations Standards.

2.35 The plan includes an assessment of key risks related to assets, decisions, finance processes, and human resources, such as that:

- invoices are inappropriately paid to the wrong accounts or in the wrong amounts;

- purchases are made without appropriate approval, probity and purpose;

- contracts are awarded inappropriately or not managed according to requirements; and

- DTA employees use their position and trusted access to commit fraud.

2.36 The Fraud and Corruption Control Plan assigns responsibility for fraud control and outlines key fraud control strategies and mechanisms for reporting and investigating fraud. The plan also states that: ‘The DTA is committed to the investigation of all reports and suspicions of fraudulent activity’.

2.37 The DTA reported ‘no instances of fraud were identified during the year’ in its annual reports for 2019–20 and 2020–21.

2.38 There was an incident of potential fraud in 2020–21, which was examined after probity concerns were raised. The examination was conducted by McGrathNicol — the firm contracted to manage the DTA’s internal audit program.

2.39 As mentioned at paragraph 2.34, the DTA Fraud and Corruption Control Plan states that the DTA’s approach to fraud control includes investigating potential fraud in accordance with the Australian Government Investigations Standards. This was not done in this instance. The McGrathNicol report does not mention the Australian Government Investigations Standards and notes that it was an ‘initial assessment’ and not a fraud investigation. The report includes the disclaimer:

This report has been prepared in accordance with the scope agreed with the DTA as set out in our engagement letter dated 10 June 2021.25 […] We have not carried out a statutory audit and accordingly, an audit opinion has not been provided. The scope of our work is different from a statutory audit and it cannot be relied upon to provide the same level of assurance as a statutory audit. Our conclusions are based solely on the information provided to us by the DTA, and we have not sought to verify any of this information.

2.40 The examination found: ‘based on available information, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate an act of fraud or corruption’; but ‘the evidence does substantiate […] a potential breach of probity guidelines, in particular the perception […] that the procurement process was not open, fair or transparent’. This incident is discussed further in Case Study 1.

|

Case study 1. Procurement for MyGov and Digital Identity Charging Framework |

|

In January 2021, a DTA senior executive met with a senior executive at ConceptSix, a consulting firm, to discuss a potential tender for a project related to the Digital Identity Charging Framework for myGov. In February 2021, the ConceptSix senior executive was engaged as a contractor following an approach to ConceptSix on the Digital Marketplace. ConceptSix was to provide strategic advice on the development of a Digital Identity Charging Framework, and to oversee a team of contractors from an external provider until 30 June 2021 (with an extension option of up to six months). On 4 May 2021, the DTA published additional opportunities on the Digital Marketplace to hire six new contractors for the same project. These labour hire procurements involved an approach to four suppliers, which included ConceptSix. The opportunities were on the Digital Marketplace for three days, and there is evidence that ConceptSix had knowledge of the procurements before the opportunities were published. In total, 20 applications were received for the six positions, with four suppliers submitting candidates. One of the two members of the evaluation panel had worked previously with two of the successful ConceptSix candidates. However, neither panel member completed an activity-specific declaration of interest form, and there is no record of the potential probity issue of the panel member’s prior relationship with the ConceptSix candidates (as required by the DTA probity guidelines). Both Senior Executive Service (SES) officers involved in the procurement had completed the DTA’s standard SES declaration of interest form for the relevant period, but neither had completed an activity-specific declaration. Of the six successful candidates, five were from ConceptSix (the sixth candidate was from a different supplier and was contracted separately). When the contract with ConceptSix was drawn up, it included the five successful candidates from ConceptSix along with the ConceptSix senior executive who had been engaged in February 2021. The ConceptSix senior executive stopped charging under his original contract in mid-June 2021 and started charging under the new ConceptSix contract from 14 June 2021, with no rate change. The contract with ConceptSix was for six months from 7 June 2021, with an option to extend by one further period of up to six months. On 10 June 2021, following concerns raised by the DTA procurement team over conflicts of interest and the above-market rates being paid, the DTA engaged McGrathNicol to examine whether there had been collusion or other activity related to the procurement that would constitute an act of fraud or corruption as defined by the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework. On 8 July 2021, McGrathNicol provided the final report to DTA. The conclusions of the report were based solely on information provided by the DTA; no interviews were conducted. The examination found: ‘based on available information, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate an act of fraud or corruption’; but ‘the evidence does substantiate […] a potential breach of probity guidelines, in particular the perception […] that the procurement process was not open, fair or transparent’. Further, it found the perception of a probity issue was exacerbated by the remuneration paid to the successful candidates, which was in excess of standard rates, and by the short time the opportunity was on the market (three days). The report recommended the DTA use a professional shortlisting service whenever an actual conflict could occur. The report also recommended that: DTA should consider whether further investigation should be conducted into whether there has been a breach of the DTA Probity Guideline. Further investigation would require interviews to be conducted with relevant DTA staff and [the supplier’s] contractors. On 2 August 2021, a senior DTA official emailed the acting DTA CEO to inform him of the report findings and suggest that the acting CEO consider: terminating the provider’s contract; providing training or performance management for the staff involved; and providing further direction to business areas to change practices in the future, with a note that ‘we recently held a discussion of a similar nature […] in relation to a different matter’. On 11 August 2021, the acting CEO forwarded the report to another DTA senior official with the note ‘please read and lets [sic] discuss’. On 30 August, the senior official responded ‘Just closing this out from our discussion a few weeks back. We agreed that it would be beneficial to provide some procurement refresh training. If you’re still agreeable, we’ll proceed on that basis.’ The acting CEO responded the same day, stating ‘Agreed. Additionally the senior execs involved need to be made aware of the perception that this issue can create.’ Further correspondence indicates that the acting CEO and senior official had ‘discussed the outcomes of the report and […] agreed that there is a need to provide refresher training to the officials involved (and the broader division) regarding probity protocols, and procurement’ and that the senior official had spoken with the senior official involved in the procurement. In April 2022, the DTA advised the ANAO on what actions the DTA had undertaken since the finalisation of the report, stating that the DTA had ‘engaged a third-party training provider to provide Probity and Fraud training to all of the SES in the agency’. The DTA did not take appropriate action following this report:

|

Fraud incident register

2.41 The Fraud and Corruption Control Plan states that:

the Fraud Control Officer will maintain a Fraud Incident Register. The Fraud Incident Register records a summary of reported fraud incidents, regardless of their outcome, and is used as a basis for providing quarterly reports to the Audit Committee.

2.42 There is no evidence that the DTA maintains a fraud incident register, but there is evidence of reporting on fraud to the audit committee. The June 2021 audit committee papers mention that there had been an instance of possible fraud (the instance discussed in Case Study 1) and that an investigation was underway. The September 2021 audit committee papers included an annual fraud control minute with the statement:

There was one instance of potential fraud reported in 2020–21. The instance was related to procurement and was identified by the central procurement team in Corporate Branch. A preliminary investigation by McGrathNicol determined that there was no evidence of fraud, and a report was prepared for the CEO.

Fraud awareness and procurement training

2.43 The PGPA Rule requires that entities have ‘an appropriate mechanism for preventing fraud, including by ensuring that: officials of the entity are made aware of what constitutes fraud’. One way to help ensure that staff are aware of what constitutes fraud, and how to prevent and deal with it, is for staff to complete fraud awareness training.

2.44 The DTA has voluntary fraud awareness training and mandatory procurement and finance training, but there have been low levels of completion. In 2020–21, from a total of approximately 350 personnel (250 DTA officials and 100 contractors):

- 95 people (27 per cent) had completed fraud awareness training; and

- 66 people (19 per cent) had completed mandatory procurement and finance training.

Recommendation no.2

2.45 The Digital Transformation Agency:

- implement a strategy to ensure all officials complete its fraud awareness and mandatory procurement and finance training; and

- strengthen its processes to ensure that potential fraud and probity breaches are investigated in accordance with its policies and that appropriate follow-up action is taken.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Internal audit and assurance activities

2.46 The DTA completed 11 internal audits between 2019 and 2021. The DTA tracks audit recommendations and reports on these to the audit committee. The 2021–22 Internal Audit Program identified two breaches of the PGPA Act where instances of expenditure exceeded the approved section 23(3) purchase order. They were for labour hire, under $5,000 and considered low risk. It also identified 112 instances where contracts and variations were reported late to AusTender, in breach of paragraph 7.18 of the CPRs.

2.47 The DTA conducted an internal audit on procurement in August 2019, which found that:

Although the DTA has developed a sound foundation for its procurement framework, this framework requires significant enhancement before it will provide adequate assurance that all DTA procurements are conducted in compliance with the CPRs and the Commonwealth Procurement Framework more broadly. Specifically, the internal audit found that:

- the DTA procurement framework is heavily reliant on the expertise of the DTA’s Procurement Team resulting in a business continuity risk; [… and]

- the DTA could improve its probity controls in place to provide increased assurance that its complex or high-risk procurements are conducted in a manner that is fair, equitable and defensible.

2.48 The internal audit made recommendations related to: improving procurement guidance and training; documenting key elements of procurements (such as risk assessments, evaluations and interest declarations); and demonstrating compliance with the CPRs. The audit committee closed out these recommendations in November 2019. However, as discussed throughout this report, the ANAO found that there are ongoing issues related to these recommendations, such as poor documentation, not completing risk assessments and conflict of interest declarations, and not demonstrating compliance with the CPRs.

Has the DTA effectively managed probity for procurements, including identifying and managing conflicts of interest?

For procurements examined by the ANAO, the DTA has not followed its internal probity guidelines, including requirements for declaring activity-specific conflicts of interest. The DTA’s policies and practices regarding receiving gifts and benefits did not meet whole-of-government requirements.

2.49 Probity is the evidence of ethical behaviour, and can be defined as complete and confirmed integrity, uprightness and honesty in a particular process.26 It provides a level of assurance to delegates, suppliers and the Australian Government that a procurement was conducted in a manner that is fair, equitable and defensible.27 The CPRs state that officials undertaking a procurement must act ethically throughout the procurement, which includes recognising and dealing with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest.28

Probity guideline and probity advisors

2.50 The DTA has established a DTA Probity Guideline, which was approved by its Chief Finance Officer in July 2020. It outlines probity principles, such as: fairness and impartiality; consistency and transparency of process; security and confidentiality; identification and resolution of actual or perceived conflicts of interest; compliance with legislative obligations and government policies as they apply to competitive tendering and contracting; and accountability.

2.51 The DTA Probity Guideline outlines that: ‘all DTA Officers and DTA Affiliates29 participating in a procurement will be required to agree to, and satisfy the principles and protocols set out in this Probity Guideline before undertaking any procurement-related activities’. This involves completing and signing a ‘Declaration of Acknowledgement and Agreement to the DTA Probity Guideline’. No officials signed declarations related to probity for any of the nine procurements examined in this audit.

2.52 The DTA Probity Guideline mentions the use of procurement and evaluation plans, but it does not mention probity plans. None of the nine procurements examined by the ANAO had a probity plan.

2.53 The guideline indicates that ‘the requirement for a probity advisor is dependent on the risk and value of a procurement. An advisor is required where the procurement risk is significant or high, or the procurement is high in value.’

2.54 Higher value procurements did not have a probity advisor, and the DTA did not make risk-based decisions on whether to appoint a probity advisor. As the DTA did not assess the risk for seven of the procurements examined, the ANAO could not assess whether these procurements should have had a probity advisor according to DTA policy. The Record Management Software procurement, which was the only procurement in the ANAO sample that had a probity advisor, had been assessed for risk, but it was assessed as low risk. There was no evidence of any advice given by the probity advisor for the Record Management Software procurement, and the evaluation report for the procurement stated: ‘There were no deviations from the approved procurement plan or [evaluation plan] during the course of the [request for tender] process’.

2.55 There was one instance in 2020–21 where the DTA commissioned an examination into potential fraud after probity concerns were raised for the myGov and Digital Identify Charging Framework procurement. As discussed in Case Study 1, the DTA did not follow through on the report’s recommendation to conduct an investigation into the potential breach of the DTA Probity Guideline. Further, no remedial actions were taken in relation to the contract, and the contract was varied twice after the fraud examination was completed, without the approving delegate being informed of the potential probity breach.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.56 There is an opportunity for improvement for the Digital Transformation Agency to update the DTA Probity Guideline to provide guidance to staff on how contracts with identified probity issues should be managed. |

Conflicts of Interest

2.57 Effective management of conflicts of interest should be a central component of an entity’s integrity framework. Poor practice, or the perception of poor practice, in the management of conflicts of interest undermines trust and confidence in an entity’s activities. The Australian Public Service (APS) Code of Conduct, which is set out in section 13 of the Public Service Act 1999, requires that APS employees take reasonable steps to avoid any real or apparent conflict of interest. Where conflicts cannot be avoided, the APS Code of Conduct, PGPA Act, and PGPA Rule require that employees must disclose details of any material personal interest. Finance guidance on ethics and probity in procurement states that:

Persons involved in the tender process, including contractors […] should make a written declaration of any actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interests prior to taking part in the process. These persons should also have an ongoing obligation to disclose any conflicts that arise through until the completion of the tender process.30

2.58 The CPRs state officials undertaking procurement must recognise and deal with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest.

Activity-specific interest declarations

2.59 According to the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) guide APS Values and Code of Conduct in Practice, entities may choose to require written declarations of interest of employees at particular risk of conflict of interest, such as those involved in procurement.

2.60 The DTA Accountable Authority Instructions state that all DTA officials ‘must disclose material personal interests in line with Commonwealth and DTA policy and operational guidelines’. The DTA Probity Guideline states that:

Any DTA Officers and DTA Affiliates with an actual, potential or perceived conflict of interest should declare that interest as soon as that conflict is known [and]

DTA Officers and DTA Affiliates must ensure their conduct does not give rise to a perception that would allow for the erosion of industry and community confidence in the way in which DTA conducts Procurement. Where DTA Officers and DTA Affiliates are concerned that a perceived or real conflict may exist, they should document all details immediately and raise the matter with the Responsible Person.

2.61 The DTA Probity Guideline further states that all DTA officers and contractors (‘DTA Affiliates’) involved in an open tender procurement must complete and sign a declaration of interests and disclosure statement (the guideline does not discuss limited tender procurements). The declaration template is provided as an appendix to the guideline — with one for APS employees and one for contractors. The DTA’s Declaration of Interest Policy also outlines that ‘procurement employees must complete the Declaration of Interest form’.

2.62 Of the nine procurements examined by the ANAO:

- for eight procurements, there was no evidence of activity-specific declarations being completed by any of the officials or contractors involved in the procurement; and

- for the Record Management Software procurement, a declaration of interest form had been completed for one of the five members of the evaluation panel, which included the statement that the official did not have any actual or perceived conflict of interest.

2.63 The ANAO spoke with the DTA procurement team and with the DTA officials involved in all of the examined procurements. The officials indicated that completing activity-based declarations of interest has not been part of general business practice at the DTA.

Senior Executive Service interest declarations

2.64 According to the APSC guide APS Values and Code of Conduct in Practice, ‘Agency heads and Senior Executive Service (SES) employees are subject to a specific regime that requires them to submit, at least annually, a written declaration of their own and their immediate family’s financial and other material personal interests’.

2.65 The DTA’s Declaration of Interest Policy states that ‘senior executives must complete the Declaration of Interest form on engagement. Forms are to be revised whenever personal circumstances change’.

2.66 Records of general interest declarations were maintained for all the senior executives involved in the nine procurements examined. However, there were three instances where a declaration for a particular year was not on file, with the DTA explaining for these instances:

- for a 2019 declaration — ‘this may be due to the fact that [the SES officer’s] SES acting had recently commenced, and acting arrangements are expected to be temporary’;

- for a 2019 declaration — ‘the missing form may not have been shared with HR’; and

- for a 2021 declaration — ‘there is no record of a declaration of interest for [this SES officer] for 2021. […] the missing form may not have been shared with HR’.

2.67 The DTA Accountable Authority Instructions state that the Human Resources Director ‘must maintain a register of all material personal interests that relates to the affairs of the DTA in accordance with these instructions’. In April 2022, the DTA advised the ANAO that it does not maintain a register of declared personal interests. In June 2022, the DTA provided the ANAO with a declaration of interest register that included details on 15 SES declarations made in the first quarter of 2021–22. The DTA provided no evidence that a declaration of interest register had been in place in 2019–20 or 2020–21.

Recommendation no.3

2.68 The Digital Transformation Agency:

- establish an internal control to ensure that officials directly involved in procurements make activity-specific declarations of interest; and

- maintain a register of declared interests.

Digital Transformation Agency response: Agreed.

Receiving gifts and benefits

2.69 The CPRs state that procurement officials must act ethically throughout a procurement, including ‘by not accepting inappropriate gifts or hospitality’ (paragraph 6.6). Finance guidance states that: ‘officials must not accept hospitality, gifts or benefits from any potential suppliers’.31 The APS Code of Conduct states that: ‘An APS employee must not improperly use inside information or the employee’s duties, status, power or authority: to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit or an advantage for the employee or any other person’.32

2.70 The DTA established a policy for receiving gifts and benefits in June 2021. According to this policy, all gifts received that exceed $200 and all ‘consequential gifts’ received must be recorded on the gift register and published on the DTA’s website.33 The DTA policy states that before accepting a gift, DTA employees must consider (among other things) ‘any perceived conflict of interest and public perception of receiving the gift’ and ‘the relationship the DTA has with the person, company or organisation offering the gift, for example, if there is a contractual relationship’.

2.71 The DTA’s 2021 gift and benefit policy did not fully align with APSC guidance (which came into effect in 2019), with the DTA guidance requiring gifts over $200 to be reported and the APSC guidance requiring gifts over $100 to be reported. The DTA advised the ANAO in June 2022 that it had updated its policy to align with the APSC guidance in response to the ANAO’s findings.

2.72 The DTA has established a gifts and benefits register. There were nine entries on the register for 2019–20; five entries for inconsequential gifts under $50 for 2020–21; and one entry for an inconsequential gift for 2021–22.

2.73 One of the entries for 2019–20 was a gift from a supplier to a DTA senior official for a $200 ticket to an Institute of Public Administration Australia event in November 2019. The register entry gives the following reason for the gift: ‘tickets were sold out and [the supplier] offered a seat at their table’. The DTA reported 14 contracts awarded to this supplier in 2019–20 and 2020–21, with a total value of $4.5 million. One of these contracts was awarded (directly, without competition) after the SES-level gift recipient suggested this supplier for a particular set of work in March 2020. Accepting a gift or hospitality from a potential or current supplier does not align with Finance guidance or the DTA’s gifts and benefits policy.34 Further, the senior official’s accepting of a gift from a supplier could have been perceived as a conflict of interest, particularly as the official was in a position to make procurement decisions that involved this supplier.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.74 There is an opportunity for improvement for the Digital Transformation Agency to provide training for senior executives on how to identify and avoid actual or perceived conflicts of interest. |

2.75 In 2019, the APSC issued guidance on gifts and benefits, including that agency heads must:

- publish a register of gifts and benefits they accept that are valued at over $100 on their departmental or agency website on a quarterly basis;

- provide a link to the agency head gifts and benefits register to the APSC for publication on the APSC’s website;

- collect and store the relevant information, and manage their register, in accordance with their agency’s procedures;

- update the register within 31 days of receiving a gift or benefit; and

- publish a ‘nil’ declaration on the gifts and benefits register where agency heads have not accepted any gifts during the reporting period.

2.76 As at 11 May 2022, no gifts and benefits register had been published to the DTA website, and there was no link to a DTA gifts and benefits register on the APSC website. In response to this finding, in June 2022, the DTA published a gifts and benefits register to its website for the first three quarters of 2021–22.35

2.77 The DTA had not recorded a declaration (nil or otherwise) for the position of CEO on the DTA gifts and benefits register for the past three financial years, and the DTA had not published any record of whether or not the CEO had received gifts and benefits over the past three financial years on the DTA website.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.78 There is an opportunity for improvement for the Digital Transformation Agency to:

|

3. Procurement activity

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) has conducted procurements effectively, including an assessment of compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

Conclusion