Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Effectiveness of the Management of Contractors — Services Australia

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Australian Public Service (APS) workforce strategy highlights the value of ensuring that agencies take a structured approach to the use of non-APS personnel. The approach adopted by the APS has been the subject of ongoing parliamentary interest.

- This is one of a series of three performance audits undertaken to provide independent assurance to Parliament on whether entities have established an effective framework for the management of the contracted element of their workforce.

Key facts

- Services Australia has defined 11 types of contingent workforce (seven types of non-agency personnel, two types of non-APS personnel and two types of secondee). The contingent workforce with the characteristics of a ‘contractor’ include contractors and labour hire.

- The top two contractor activities reported by Services Australia in 2021 were ‘Information Technology’, and ‘Service Delivery’.

What did we find?

- Services Australia has established largely fit-for-purpose policies and processes for the management of contractors and can demonstrate the effectiveness of some but not all aspects of its arrangements. There remains scope to improve the effectiveness of mandatory training arrangements and implementation of aspects of Policy 12 of the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) relating to the eligibility and suitability of personnel.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations aimed at: improving the effectiveness of mandatory training arrangements; aligning the personnel security policy with Supporting Requirement 1(c) of PSPF Policy 12; and obtaining assurance that PSPF Policy 12 has been addressed, particularly where temporary access provisions are used to address the need for rapid recruitment.

34,049

Services Australia’s APS workforce at 30 June 2021 (headcount).

10,012

Services Australia’s contingent workforce at 30 June 2021 (headcount).

4269

Contractor workforce at 30 June 2021 (headcount). Represents 9.7 per cent of the combined APS and contingent workforce.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) has reported that as at 31 December 2021, the Australian Public Service (APS) employed 155,796 people across 97 APS agencies.1 APS employees are employed under the Public Service Act 1999 (the PS Act), which establishes the APS and is the basis of the regulatory framework applying to it.2

2. APS agencies can, and do, utilise a mixed workforce of APS and non-APS personnel to deliver their purposes. Non-APS personnel include contractors and consultants. Department of Finance (Finance) guidance indicates that the difference between a contract for services and a contract for consultancy services ‘generally depends on the nature of the services and the level of direction and control over the work that is performed to develop the output.’3

3. Workforce planning and management is the responsibility of each APS agency head. In the APS Workforce Strategy 2025, the APSC has stated that:

Ensuring agencies take a structured approach to the use of non-APS employees—including considering where work would be best delivered by an APS employee—and knowledge transfer and capability uplift arrangements is a key element of successful mixed workforce models, which are already being used by agencies across the APS.4

4. Additionally, the APSC has published guidance in the form of Guiding principles for agencies when considering the use of SES contractors5 relating to the use of contractors in APS Senior Executive Service (SES) roles.6 Similar guidance has not been issued for entities when considering the use of contractors for non-SES level roles.

5. The engagement and management of non-APS personnel occurs through procurement action by entities and their contract management processes, rather than the PS Act. These decisions must consider:

- the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which establish the whole-of-government procurement framework, including mandatory rules with which officials must comply when performing duties related to procurement;

- the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), which sets out government protective security policy across the following outcomes: security governance, information security, physical security and personnel security7; and

- entity-specific procurement and contract management arrangements which may be contained in Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) made under section 20A of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act, which is the basis of the Australian Government’s finance law) and in entity policies and guidelines.

6. Services Australia has advised the Parliament that as at 30 June 2021, its workforce included 4269 contractors, representing 9.7 per cent of the combined APS and contingent workforce.8 Services Australia’s contractor workforce performs work in most parts of the entity.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. The APS workforce strategy states that the APS will continue to deploy a flexible approach to resourcing that strikes a balance between a core workforce of permanent public servants and the selective use of external expertise. This will mean a continuing mixed workforce approach, where APS employees and non-APS workers are used to deliver outcomes within agencies. In this context, the strategy highlights the value of ensuring that agencies take a structured approach to the use of non-APS workers. The approach adopted by the APS and its agencies has been the subject of ongoing parliamentary interest, with a number of reviews and parliamentary committee inquiries undertaken in recent years.9

8. This audit is one of a series of three performance audits undertaken to provide independent assurance to the Parliament on whether entities have established an effective framework for the management of the contracted element of their workforce. Services Australia was selected as one of the APS agencies in this audit series as it is a large and regular user of non-APS personnel. The other audits in this series review the management of contractors by the Department of Defence and Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Audit objective and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Services Australia’s arrangements for the management of contractors.

10. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has Services Australia established a fit-for-purpose framework for the use of contractors?

- Does Services Australia have fit-for-purpose arrangements for the engagement of contractors?

- Has Services Australia established fit-for-purpose arrangements for the management of contractors?

Conclusion

11. Services Australia has established largely fit-for-purpose policies and processes for the management of contractors and can demonstrate the effectiveness of some but not all aspects of its arrangements. There remains scope to improve the effectiveness of mandatory training arrangements and implementation of aspects of Policy 12 of the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) relating to the eligibility and suitability of personnel.

12. Services Australia has established a fit-for-purpose framework for the use of contractors. At the agency level there is guidance which provides clarity regarding the different personnel types, including contractors. Guidance has been developed to assist the largest users of contractors within the agency — its service delivery and ICT areas — determine whether there is an operational requirement for the use of contractors.

13. Services Australia has established largely fit-for-purpose arrangements for the engagement of contractors. Services Australia has in place a contracting suite that is tailored for the use of contractors and has established centrally managed processes for preparing contracts, including when it engages contractors. Services Australia has established mandatory induction training and systems to monitor and report on the completion of induction training by its entire workforce. The effectiveness of training arrangements is reduced by contractors’ training completion rates and shortcomings in processes to ensure contractors and their managers are aware of mandatory induction training. Services Australia has established policy and processes to support compliance with the majority of core requirements of PSPF Policy 12: Eligibility and suitability of personnel when it engages contractors, the key exception being the requirement to obtain an individual’s agreement to comply with government policies, standards, protocols and guidelines that safeguard resources from harm. By enacting temporary access provisions pending the outcome of pre-engagement eligibility and suitability checks, there is a risk that Services Australia has not met PSPF Policy 12 requirements where there is no assurance process to ensure satisfactory completion of the required checks within a reasonable timeframe.

14. Services Australia has established largely fit-for-purpose arrangements for the management of contractors. Services Australia has clearly documented its requirements and expectations regarding the management and oversight (supervision) of contractors and has established responsibilities for managing completion at the business area level. Arrangements (policy, processes and monitoring) for the management of contractors that support compliance with PSPF Policy 13: Ongoing assessment of personnel and PSPF Policy 14: Separating personnel have been largely established. With regards to PSPF Policy 14, risks have been identified regarding the effectiveness of agency controls for removing separating individuals’ systems access in a timely way.

Supporting findings

Framework for using contractors

15. Services Australia’s guidance provides clarity regarding the different personnel types, including contractors. (See paragraphs 2.3–2.5)

16. In its provision of guidance on determining whether there is an operational requirement for the use of contractors, Services Australia has focused on the largest users of contractors within the agency — its service delivery and ICT areas. Services Australia has developed arrangements to support workforce planning in its service delivery and ICT workforces which include workforce strategies intended to guide decisions on workforce supply, including for the use of contractors. Decisions to use contractors in all parts of Services Australia’s business are guided by the agency’s Average Staffing Level cap and internal budget allocations. (See paragraphs 2.6–2.11)

Arrangements for engaging contractors

17. Services Australia has in place a contracting suite that is tailored for the use of contractors and has established centrally managed processes for preparing contracts, including when it engages contractors. For the nine contracts for the engagement of contractors reviewed by the ANAO (engaging 30 per cent of the contractor personnel engaged by Services Australia as of 31 October 2021) all contracts: stated that the supplier must ensure that its personnel comply with all procedures and guidelines required by Services Australia; and included references to applicable agency policies, procedures and guidelines. There was some variability in the terms and conditions of the contracts selected for review, with five ICT contracts not including performance standards. An internal audit from August 2020 states that Services Australia has accepted the risks associated with a lack of performance indicators in the ICT contracts. (See paragraphs 3.3–3.14)

18. Services Australia has largely fit-for-purpose arrangements for inducting contractors, with the completion of mandatory training by its non-APS personnel recorded through monthly reporting. The effectiveness of the arrangements is limited due to low completion rates for mandatory induction and refresher training for contractors, and shortcomings in processes to ensure that contractors complete training. Monthly training reports examined by the ANAO showed that of the contractors engaged by the agency as at 28 February 2022, 34.7 per cent had completed the mandatory induction modules — with a further 28.3 per cent of contractors deemed ‘induction compliant’ by Services Australia — and 32.2 per cent had completed the 2022 mandatory refresher program. Services Australia advised the ANAO that as at 30 April 2022, 39.3 per cent of contractors had completed the mandatory induction modules — with a further 27.0 per cent of contractors deemed ‘induction compliant’ — and 48.8 per cent of contractors had completed the 2022 mandatory refresher program. (See paragraphs 3.15–3.35)

19. Services Australia has established policies and processes that support compliance with the majority of core requirements of PSPF Policy 12: Eligibility and suitability of personnel when it engages contractors, except for PSPF Policy 12 Supporting Requirement 1(c), which relates to obtaining individuals’ agreement to comply with the government’s policies, standards, protocols and guidelines that safeguard resources from harm. Services Australia has enacted temporary access provisions in its personnel security policy ‘to enable rapid recruitment to meet the high service demand generated by COVID-19’ and to manage the 2022 east coast flood emergency and other priorities. There is scope for Services Australia to strengthen its assurance activities to ensure that the mandatory requirements of PSPF Policy 12 have been met, particularly when personnel have already been granted temporary access to Australian Government resources (people, information and assets). (See paragraphs 3.38–3.60)

Arrangements for managing contractors

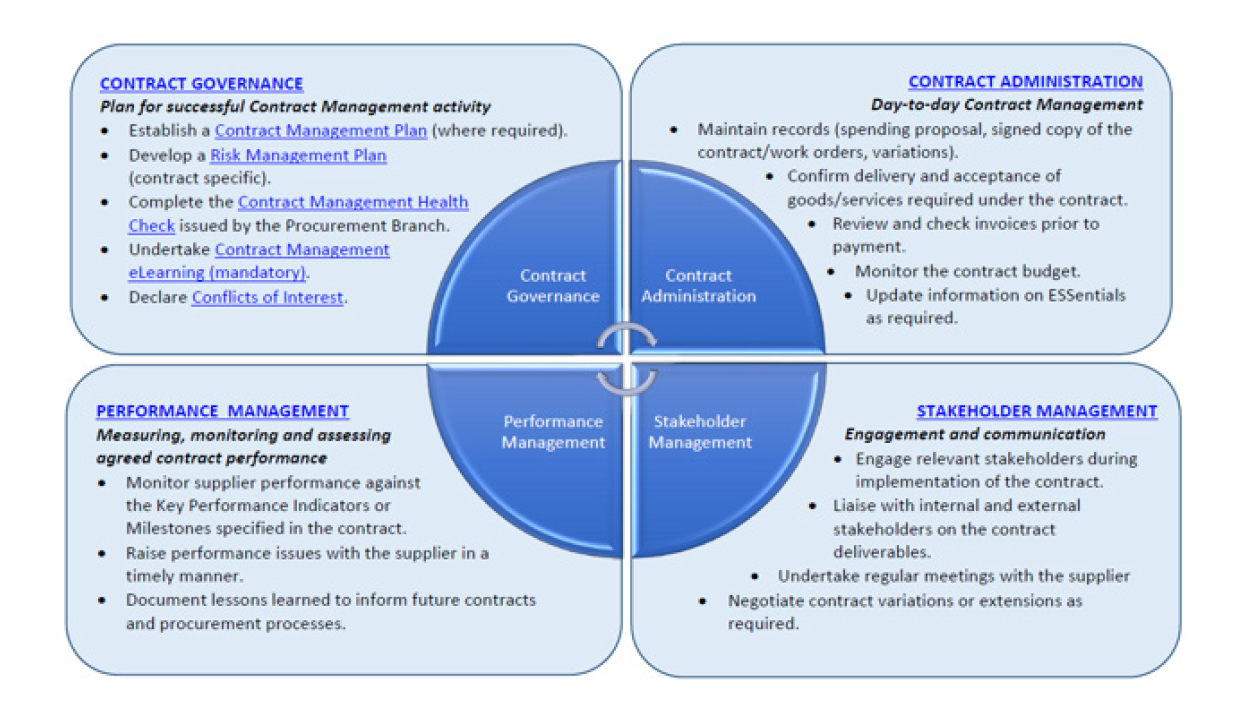

20. Services Australia has clearly documented its requirements and expectations regarding the management and oversight of contractors. Agency requirements and expectations for contract managers are documented in the Accountable Authority Instructions, the Contract Management Framework and in policies, procedures and guidance. Contract managers are required to undertake mandatory training, with training requirements tailored to the overall risk rating of the contract to be managed. Services Australia requires business areas to ensure that appropriate training has been undertaken but has not established arrangements that provide agency-wide assurance that contract managers have completed the mandatory training. (See paragraphs 4.3–4.13)

21. Services Australia has largely established arrangements for the management of contractors that support compliance with PSPF Policy 13: Ongoing assessment of personnel. Services Australia has established policies that support the implementation of PSPF Policy 13 for contractors that address all aspects of the core PSPF requirement. All nine contracts examined by the ANAO included clauses requiring ongoing compliance with Services Australia’s security policies and procedures. In addition, guidance has been established for contract managers around assessing and managing the ongoing suitability of contractors and sharing relevant information of security concern, including forms for reporting security incidents. Where contract periods are greater than three years, Services Australia has no agency-wide assurance that its mandatory requirement for triennial eligibility and suitability checks for contractors is being met. Services Australia has identified opportunities to strengthen arrangements to support compliance with PSPF Policy 13. (See paragraphs 4.14–4.20)

22. Services Australia has established arrangements for the separation of contractors to support compliance with PSPF Policy 14: Separating personnel, including relevant policies and processes, however there is scope for implementation to be more effective. In the nine contracts examined by the ANAO, Services Australia included clauses requiring contractors to comply with Services Australia policies and processes that support compliance with PSPF Policy 14. ANAO testing identified risks in the effectiveness of Services Australia’s ICT controls for removing separating individuals’ systems access in a timely way. Services Australia’s monitoring and reporting on compliance with PSPF Policy 14 has identified that there is further work to be done and identified a range of activities to improve compliance around separating personnel, including strengthening the assurance process for the timely removal of separating individuals’ access to agency systems. (See paragraphs 4.21–4.29)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.35

Services Australia ensure that:

- contractors and managers of contractors are aware of their responsibilities regarding mandatory induction training requirements; and

- contractors complete mandatory induction training.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.45

Services Australia update its personnel security policy to include a requirement to obtain an individual’s agreement to comply with government policies, standards, protocols and guidelines that safeguard resources from harm, as required under Supporting Requirement 1(c) of PSPF Policy 12.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.60

Services Australia strengthen arrangements to obtain assurance that PSPF Policy 12 requirements have been met, particularly to ensure the eligibility and suitability of its personnel who have been granted temporary access to Australian Government resources (people, information and assets).

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

23. Services Australia’s summary response is provided below and its full response is included at Appendix 1. An extract of this report was sent to the APSC. The APSC’s summary response is provided below and its full response is included at Appendix 1.

Services Australia’s summary response

Services Australia (the agency) welcomes this report, and considers that the recommendations will assist in improving our arrangements for the management of contractors. Changes to the agency’s workforce size and composition reflect government priorities, Budget measures, service delivery demands, ongoing efficiencies and natural attrition. In this context, strong agency capability is essential in delivering on government commitments and transforming the organisation. It is positive that the ANAO has found the agency has a fit-for-purpose framework for the use of contractors, particularly in respect to the guidance that is in place for those groups that are the largest users of contractors, service delivery and ICT.

APSC’s summary response

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) acknowledges the extract of the Proposed Audit Report on the ‘Effectiveness of the Management of Contractors’ provided for comment.

The APSC recognises the importance of robust workforce planning through implementation of the APS Workforce Strategy 2025. This includes strengthening APS capability, and the strategic use of mixed models of employment, to ensure agencies achieve their outcomes.

Whilst no recommendations are directed toward the APSC, the Commission will consider any relevant findings following the audit’s completion.

24. At Appendix 2, there is a summary of improvements that were observed by the ANAO during the course of the audit.

Key messages and observations

25. This is one of a series of three performance audits undertaken to provide independent assurance to Parliament on whether entities have established an effective framework for the management of the contracted element of their workforce. As well as Services Australia, the ANAO has examined the effectiveness of the management of contractors by the Department of Defence10 and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.11

26. Chapter 5 of this audit report sets out high-level observations and key messages for all Australian Public Service agencies following the ANAO’s examination of the three selected agencies’ management of contractors. The observations focus on: data availability and transparency issues relating to the contractor workforce; and the application of ethical and personnel security requirements to the contractor workforce.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) has reported that as at 31 December 2021, the Australian Public Service (APS) employed 155,796 people across 97 APS agencies.12 APS employees are employed under the Public Service Act 1999 (the PS Act), which establishes the APS and is the basis of the regulatory framework applying to it.13

1.2 APS agencies can, and do, utilise a mixed workforce of APS and non-APS personnel to deliver their purposes. Non-APS personnel include contractors and consultants. Department of Finance (Finance) guidance indicates that the difference between a contract for services and a contract for consultancy services ‘generally depends on the nature of the services and the level of direction and control over the work that is performed to develop the output.’14

1.3 In summary, Finance’s guidance states that services performed by a contractor are under the supervision of the entity, which specifies how the work is to be undertaken and has control over the final form of any resulting output. The output of a contractor is produced on behalf of the entity and the output is generally regarded as an entity product. In contrast, performance of consultancy services is left largely up to the discretion and professional expertise of the consultant, performance is without the entity’s direct supervision, and the output reflects the independent views or findings of the consultant. While the output of a consultant is produced for the entity, the output may not belong to the entity. Box 1 below sets out the contract characteristics, identified in Finance guidance, that help entities distinguish between contractors and consultants.

|

Box 1: Department of Finance guidance—characteristics of consultancy and non-consultancy contracts |

|

Contractors—characteristics of non-consultancy contracts (only some may apply): Nature of Services:

Direction and Control:

Integration or Organisation Test:

Use of Equipment and Premises:

Remuneration:

Consultants—characteristics of consultancy contracts Nature of Services:

Direction and Control:

Integration or Organisation Test:

Use of Equipment and Premises:

Remuneration:

|

Source: Department of Finance, Contract Characteristics, available from https://www.finance.gov.au/government/procurement/buying-australian-government/contract-characteristics [accessed 20 January 2022].

1.4 Workforce planning and management is the responsibility of each APS agency head. In the APS Workforce Strategy 2025, in respect to the mix between APS and non-APS personnel, the APSC has stated that:

The APS continues to deploy a flexible approach to resourcing that strikes the balance between a core workforce of permanent public servants and the selective use of external expertise. This will mean a continuing mixed workforce approach, where APS employees and non-APS workers collaborate to deliver outcomes within agencies.

A mixed workforce approach will continue to be a feature of APS workforce planning. Non-APS workers, when used effectively in appropriate circumstances, can provide significant benefits to agencies and help them achieve their outcomes. Non-APS workers can also provide access to specialist and in-demand skills to supplement the APS workforce in peak times in business cycles. There will be a need for APS agencies to access skills, capability or capacity differently, including through contractors and consultants, or through external partnerships with academia or industry. There may also be a need to engage with industry to develop skills and capabilities to drive delivery of programs across the service. The use of non-APS employees, including labour hire, contractors and consultants, brings different opportunities and risks for APS agencies to manage. Agencies relying on mixed workforce arrangements need to take an integrated approach to workforce planning that includes and best utilises their non-APS workers. This is particularly important where key deliverables are specifically reliant on this non-APS workforce.

Ensuring agencies take a structured approach to the use of non-APS employees—including considering where work would be best delivered by an APS employee—and knowledge transfer and capability uplift arrangements is a key element of successful mixed workforce models, which are already being used by agencies across the APS.

A professional public service harnesses skills, expertise and capacity from a variety of sources to deliver services as priorities arise. We must focus on understanding and removing barriers to external mobility and encouraging the mobilisation of skills from both across and outside the APS.15

1.5 In addition, the APSC has published guidance relating to the use of contractors in APS Senior Executive Service (SES) roles.16 In its Guiding principles for agencies when considering the use of SES contractors17, the APSC states that:

To meet their business needs, agency heads have the flexibility to engage individuals by the most appropriate means to ensure their agency is best placed to deliver for the Australian public. These guiding principles are designed to assist agencies when considering the appropriateness of using a contractor for a Senior Executive Service (SES) equivalent role and to ensure that appropriate governance arrangements are in place.

…

For the purposes of these principles, an ‘SES contractor’ is an SES-equivalent (e.g. equivalent work value, duties, responsibility, and accountability), contracted by an APS agency via a recruitment agency or third party as an integrated part of the agency’s senior leadership workforce. That is, the agency will have no direct employment relationship under the PS Act with the SES contractor.

1.6 The APSC has stated that the purpose of the principles is ‘to provide APS agencies with considerations when seeking to go beyond the APS employment framework for senior executive capabilities’.18 Box 2 below sets out the considerations identified in the APSC guidance.

|

Box 2: APSC guidance—considerations when using an SES contractor to fill a role |

|

Before using an SES contractor to fill a role, agencies should satisfy themselves that there is a genuine operational requirement for an SES contractor.

Agencies should ensure their systems, infrastructure, contracts and governance are appropriate to manage using SES contractors. This includes ensuring that:

Under subsection 78(8) of the PS Act, if it is proposed that an SES contractor will exercise delegated functions or powers, consent must be sought from the APS Commissioner before any functions or powers are delegated to the SES contractor.

|

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Guiding principles for agencies when considering the use of SES contractors, 14 May 2021, paragraphs 5–7, available from https://www.apsc.gov.au/working-aps/aps-employees-and-managers/senior-executive-service-ses/senior-executive-service-ses/contractors-senior-executive-service [accessed 3 December 2021].

1.7 The APSC guidance states that the APSC will collect data on SES contractors, and that for the purposes of reporting, an SES contractor is a person undertaking SES equivalent work who is not engaged under the PS Act or an agency’s enabling legislation.19 As at 8 March 2022 the APSC had not published data on SES contractors. The APSC advised the ANAO on 3 March 2022 that there were 40 SES contractors in the APS as at 31 October 2021.

1.8 The APSC has not issued guiding principles for the use of non-SES contractors in APS agencies.20

1.9 The APSC and Finance guidance may be supplemented at the entity-level by internal guidance on the different personnel types and how to decide whether there is an operational requirement for the use of non-APS personnel such as contractors.

1.10 The engagement and management of non-APS personnel occurs through procurement action by entities and their contract management processes, rather than the PS Act. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) establish the whole-of-government procurement framework, including mandatory rules with which officials must comply when performing duties related to procurement. Entity-specific procurement and contract management arrangements may also be contained in Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) made under section 20A of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act, which is the basis of the Australian Government’s finance law) and in entity policies and guidelines. Contract managers must implement applicable internal requirements and the CPRs and associated requirements set by the Department of Finance. Non-APS personnel must comply with their contractual obligations and any applicable management, oversight and behavioural requirements.

1.11 Non-APS personnel may be ‘officials’ under section 13 of the PGPA Act, in which case they must comply with the finance law in addition to their contractual obligations and applicable entity requirements.21 The finance law includes the PGPA Act, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule), entity AAIs, and other legal and policy frameworks — including the whole-of-government procurement, grants, advertising and risk management frameworks. All personnel exercising delegated power under the PGPA Act or other legislation must also comply with the requirements attaching to those delegations.

1.12 Entities’ management of their non-APS personnel is subject to the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), which sets out government protective security policy across the following outcomes: security governance, information security, physical security and personnel security.22 The PSPF policies under the ‘personnel security’ outcome outline how to screen and vet personnel and contractors to assess their eligibility and suitability. They also cover how to assess the ongoing suitability of entity personnel to access government resources and how to manage personnel separation.23 Entity compliance with the three personnel security policies under the PSPF ‘ensures its employees and contractors are suitable to access Australian Government resources, and meet an appropriate standard of integrity and honesty’.24 The policies and their core requirements are outlined in Figure 1.1 below.

Figure 1.1: PSPF personnel security policies and core requirements

Source: Protective Policy Security Framework, Personnel security, available from https://www.protectivesecurity.gov.au/policies/personnel-security [accessed 3 December 2021].

1.13 Under the PSPF, all agencies must develop their own protective security policies and processes. Services Australia publishes its security policies and procedures on its intranet.

Reviews and inquiries into the APS’s use of contractors

2015 report of the Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation

1.14 The 2015 Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation (the Belcher Review)25 observed the impact of a number of APS legislative and reporting requirements26, which the review considered to have:

created a recruiting environment where entities tend to engage staff through a particular employment category that may not align with their business needs. For example: … contractors hired individually, or through firms, are excluded from ASL [average staffing level] and headcount reporting. While a valid engagement option, it may present longer term issues regarding organisational capacity and knowledge management, and may be a more expensive option in the longer run.27

1.15 Box 3 below contains an excerpt from a Parliamentary Library research paper on public sector staffing and resourcing, which addresses the ASL concept and related issues.28

|

Box 3: Public sector staffing and resourcing (Staffing, contractors and consultancies)—Parliamentary Library, October 2020—excerpt |

|

When discussing public sector employees, the budget papers use the average staffing level (ASL), a method of counting that adjusts for casual and part-time staff in order to show the average number of full-time equivalent employees. ASL is almost always a lower figure than a headcount of actual employees (the Australian Public Service Commission uses the headcount method).a In the 2015–16 Budget, the Government undertook to maintain the size of the general government sector (GGS), excluding military and reserves, at around or below the 2006–07 ASL of 167,596. Agency Resourcing: Budget paper No. 4: 2020–21 indicates that this objective has been achieved over the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

Note a: ANAO comment: the APSC has stated that ‘ASL counts staff for the time they work. For example, a full-time employee is counted as one ASL, while a part time employee who works three full days per week contributes 0.6 of an ASL. The ASL averages staffing over an annual period. It is not a point in time calculation.’ See Appendix 3 of this audit.

Source: Philip Hamilton, Public sector staffing and resourcing (Staffing, contractors and consultancies), Parliamentary Library Research Publications, October 2020, available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview202021/PublicSectorStaffingResourcing [accessed 27 January 2022].

2019 report of the Independent Review of the APS

1.16 The 2019 Our Public Service, Our Future: Independent Review of the Australian Public Service (the Thodey Review) also considered the non-APS workforce.29 The Thodey Review commented that:

Labour contractors and consultants are increasingly being used to perform work that has previously been core in-house capability, such as program management. Over the past five years, spending on contractors and consultants has significantly increased while spending on APS employee expenses has remained steady.30

1.17 The Thodey Review published data (see Figure 1.2 below) based on submissions to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) Inquiry into Australian Government Contract Reporting – Inquiry based on Auditor-General’s report No. 19 (2017–18).31 The Thodey Review stated that submissions to the JCPAA inquiry ‘revealed that [the] spend on contractors more than doubled across a sample of 24 agencies between 2012–13 and 2016–17.’32

Figure 1.2: Thodey Review — percentage change in spend on employees, labour contractors and consultancy contract notices

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Our Public Service, Our Future: Independent Review of the Australian Public Service, p. 186.

1.18 The Thodey Review further observed that:

The use of labour contractors and consultancy services warrants specific discussion. About a quarter of the submissions [to the review] commented on their use. Most expressed concern about the growing size of the APS’s external workforce and the negative effect on in-house capability. Data on this topic, as is the case with many APS-wide workforce matters, are not gathered or analysed centrally and are often inadequate. For example, the number of contractors and consultants working for the APS is not counted and data on expenditure are inconsistently collected across the service. Data insights that would shed light on whether contractors or consultants met objectives are not routinely aggregated. This makes it difficult to assess the value of external providers relative to in-house employees or to infer the effect on APS capability.33

…

There is clearly benefit in the APS leveraging the best external capability. It is not possible to have expertise in everything in-house and external providers can be the most efficient way of delivering the best advice, services or support. But the use of external capability needs to be strategic and well-informed, meaning that the APS:

- makes decisions on the use of external capability by reference to a whole-of-service workforce strategy that identifies the core capabilities the APS should invest in building in-house – with external capability used to perform non-core or variable work activity;

- manages use of external capability closely, from the contract design stage through to performance of the prescribed tasks; and

- ensures that all arrangements lead to a transfer of knowledge to the APS.

At all stages the APS should be focused on achieving value for money and better outcomes.

The APS needs to find the right balance between retaining and developing core in-house capability and leveraging external capability to ensure a sustainable and efficient operating model for the decades ahead. To do this effectively, two traditionally autonomous parts of agencies — HR and procurement — must work closely together.34

October 2021 second interim report of the Senate Select Committee on Job Security

1.19 In October 2021, the Senate Select Committee on Job Security released its second interim report, Insecurity in publicly-funded jobs.35 The report examined employment arrangements across the public sector. Drawing on the Thodey Review and JCPAA inquiry, the committee stated that:

the utilisation of labour contractors and consultants has increased markedly in recent years. Across a sample of 24 agencies, spending on contractors has more than doubled over the period between 2012–13 and 2016–17. Furthermore, information sourced from AusTender indicated that the total value of consultant contracts across the APS increased from $386 million to $545 million during the same four year period.36

1.20 In common with the Thodey Review37, the committee was critical of data collection relating to the non-APS workforce:

Neither the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC), nor the Department of Finance, was able to confirm how many people engaged through labour hire or other external contracting arrangements are working within the Australian Public Service. This data is not collected, and neither agency provided an explanation for why this is the case.38

1.21 The committee made the following recommendation on this matter:

The committee recommends that the Australian Government requires:

- the Australian Public Service Commission to collect and publish agency and service-wide data on the Government’s utilisation of contractors, consultants, and labour hire workers;

- the Department of Finance to regularly collect and publish service-wide expenditure data on contractors, consultants, and labour hire workers, including the cost differential between direct employment and external employment; and

- labour-hire firms to disclose disaggregated pay rates and employee conditions.39

November 2021 report on the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee Inquiry into the Current Capability of the APS

1.22 In November 2021 the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee reported on its Inquiry into the Current Capability of the Australian Public Service.40 The matter referred to the committee for inquiry and report was as follows41:

The current capability of the Australian Public Service (APS) with particular reference to:

(a) the APS’ digital and data capability, including co-ordination, infrastructure and workforce;

(b) whether APS transformation and modernisation projects initiated since the 2014 Budget have achieved their objectives;

(c) the APS workforce; and

(d) any other related matters.

1.23 The committee drew on data in the Thodey Review42 and JCPAA inquiry43, and in an effort to ascertain the scale of labour hire usage across the APS44, requested staffing profile information from agencies across all portfolios.45 The committee observed that:

The responses received indicated that agencies had differing methods of collecting data, and that many agencies did not collect data that allowed them to disaggregate the numbers of labour hire workers from other contractors.

For example, some agencies advised that their recordkeeping systems did not or could not differentiate between contractors directly procured by the agency (e.g. independent contractors), and workers procured through labour hire firms.46

1.24 The committee made 13 recommendations, including the following recommendations on data collection and reporting:

- the annual employee census conducted by the APSC ahead of the State of the Service report be expanded to include all labour hire staff who have been engaged on behalf of the APS in that calendar year (recommendation 5);

- the APSC collect and publish standardised agency and service-wide data on the Australian Government’s utilisation of contractors, consultants, and labour hire workers (recommendation 6); and

- the Department of Finance regularly collect and publish annually service-wide expenditure data on contractors, consultants, and labour hire workers, including the cost differential between direct employment and external employment for each role (recommendation 8).

Services Australia’s workforce

1.25 Services Australia is an Executive Agency established under subsection 65(1) of the Public Service Act 1999.47 In its 2020–21 annual report, Services Australia states that it:

designs, develops, delivers, coordinates and monitors government services and payments relating to social security, child support, students, families, aged care and health programs. We provide advice to government on the delivery of these services and payments, and collaborate with other agencies, providers and businesses to provide convenient, accessible and efficient services to individuals, families and communities.48

1.26 Among the agency’s key functions are the delivery of Centrelink social security payments and services, the administration of Medicare, and assistance with child support arrangements between separated parents. To deliver its key activities, Services Australia has an approved workforce allocation for APS resources in the Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS). The actual APS workforce is reported in Services Australia’s annual report each year. Table 1.1 below sets out Services Australia’s workforce allocation and utilisation over three years.

Table 1.1: Services Australia’s budgeted and actual APS workforce

|

APS workforce |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|

Budget estimatea |

28,587 |

26,703 |

27,637 |

|

Actualb |

27,529 |

26,682 |

27,896 |

Note a: Budget Estimate data is sourced from Services Australia’s Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS). Services Australia defines these figures as ‘The average number of employees receiving salary/wages (or compensation in lieu of salary/wages) over a financial year, with adjustments for casual and part-time employees to show the full-time equivalent.’

Note b: Actual workforce data is sourced from Services Australia’s annual reports, reported as FTE (over the financial year). This differs from the figures in Table 1.2 which are reported by headcount.

Source: Services Australia Portfolio Budget Statements and annual reports 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21.

1.27 Services Australia’s 2019–23 Strategic Workforce Plan identifies that determining an appropriate workforce mix (including the non-APS workforce) is an important element of maintaining a flexible, capable and connected workforce across the country to deliver its outcomes. In addition to its APS workforce, Services Australia has defined 11 types (cohorts) of contingent workforce. These are: student placement; system access only; contractor; labour hire; consultant; interpreter; service staff; outsourced (staff); APS secondee; non-APS secondee; and partner.

1.28 Box 4 below sets out the workforce definitions used by Services Australia that have the characteristics of a ‘contractor’ discussed in paragraphs 1.2–1.3 and Box 1.

|

Box 4: Definitions of types of workforce resources that have the characteristics of a contractor — Services Australia |

|

Contractor A person is a contractor if:

Excludes persons supplied through a labour-hire company or the labour- hire panel. Labour hire A person is a labour hire worker if:

Service staff A person supplied to the agency pursuant to a contract for services to provide specified services, outcomes or products where the contract does not specify the quantity of labour effort to be delivered. The agency does not direct the performance of the persons supplied under the contract and the agency has limited control over who or how many persons are provided to deliver the services. The services cannot easily be equated to Full Time Equivalent hours (FTE). Outsourced (Staff) A person supplied to the agency under a contract for services, where the contract does specify the quantity of labour effort to be delivered. The agency does not direct the performance of the persons supplied under the contract, and the agency has limited control over who or how many persons are provided to deliver the service. The contract for services focuses on the delivery of defined outcomes, services or products. The contract does not specify the individuals who will perform the services or contain specific terms and conditions in relation to the performance of individual workers. Services Australia advised the ANAO in March 2022 that non-APS consultants are also included in this category for all figures prior to 31 March 2021 due to Human Resource system limitations. |

Source: Services Australia, Contingent workforce resources definitions intranet page, 16 July 2020. Services Australia’s definition of a consultant is ‘A party whose services under the contract meet the Department of Finance’s criteria for a consultancy’.

1.29 This audit has focused on Services Australia’s workforce resources engaged as ‘contractors’ and ‘labour hire’. Service’s Australia’s definitions in Box 4 state that these persons are supplied ‘to do work in and as part of the operations of the agency’.49 In contrast, for ‘service staff’ and ‘outsourced’ staff, Services Australia’s definitions state that the agency does not direct the performance of the persons supplied under the contract and the agency has limited control over who or how many persons are provided to deliver the services. Contractors and labour hire personnel perform work in all parts of the operations of the agency and Services Australia maintains responsibility for performance.50

Contractor numbers in Services Australia

1.30 Table 1.2 below sets out Services Australia’s APS and contingent workforce headcounts over three years. It includes the agency’s contractor workforce headcount as advised to the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee in the context of the committee’s Inquiry into the Current Capability of the APS (discussed in paragraphs 1.22–1.24).

Table 1.2: Services Australia’s workforce headcount

|

Workforce category |

Headcount at 30 June 2019 |

Headcount at 30 June 2020 |

Headcount at 30 June 2021 |

|

APS full-time |

20,209 |

19,976 |

19,466 |

|

APS part-time |

7882 |

7573 |

7466 |

|

APS non-ongoing (including casual employees) |

2503 |

4204 |

7117 |

|

Total APS workforcea |

30,594 |

31,753 |

34,049 |

|

Contractorsb |

5165 |

6993 |

4269 |

|

Consultants |

–c |

110 |

52 |

|

Other contingentd |

4039 |

6144 |

5691 |

|

Total contingent workforcee |

9,204 |

13,247 |

10,012 |

Note a: Services Australia annual reports 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21.

Note b: See definitions in Box 4. The contractor headcount is the number of individuals categorised as ‘labour hire’ or ‘contractor’ in Services Australia’s ‘Contingent Workforce’ report. The ‘Contingent Workforce’ report is extracted from Services Australia’s Human Resource management system. The report identifies individuals that are not engaged by Services Australia as APS employees who have access to Services Australia’s systems.

Note c: As acknowledged in Box 4, non-APS consultants were included in the ‘outsourced staff’ personnel type up to 31 March 2021 and due to the qualifications over these figures, they have not been included in the table.

Note d: Other contingent workforce headcount is the number of individuals categorised as ‘outsourced staff’ or ‘service staff’ in Services Australia’s ‘Contingent Workforce’ report. Services Australia advised the ANAO in June 2022 that ‘Consistent with the definitions in Box 4, outsourced staff and service staff are not reported as headcount, this is because these contracts for this personnel type are a fee-for-service arrangement, whereby they provide for workload seconds and do not translate directly to headcount as this is not specified in the arrangements. The Service Delivery Partners that provide outsourced staff, determine the workforce number required to meet the pre-determined workload.’

Note e: As noted in paragraph 1.27, Services Australia has 11 types (cohorts) of contingent workforce. The contingent workforce figure in this table includes five of these cohorts: contractor, labour hire, consultant, service staff, and outsourced (staff).

Source: Services Australia annual reports 2018–19 and 2019–20 and Services Australia records and advice to ANAO.

1.31 Further information on the characteristics of Services Australia’s 4269 contractor personnel as at 30 June 2021 is at Appendix 4, including the organisational group they worked in and their length of service.

Previous audits and reports

1.32 Agencies’ management of their contracted workforce is considered when necessary in the conduct of ANAO audit and assurance work. Examples of ANAO performance audits which have considered the management of a contracted workforce include:

- Auditor-General Report No.2 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Materiel Sustainment51;

- Auditor-General Report No.38 2017–18 Mitigating Insider Threats through Personnel Security52;

- Auditor-General Report No.28 2018–19 Management of Smart Centre’s Centrelink Telephone Services — Follow-up53;

- Auditor-General Report No.1 2021–22 Defence’s Administration of Enabling Services — Enterprise Resource Planning Program: Tranche 154;

- Auditor-General Report No.4 2021–22 Defence’s Contract Administration — Defence Industry Security Program55; and

- Auditor-General Report No.6 2021–22 Management of the Civil Maritime Surveillance Services Contract.56

1.33 The ANAO has prepared two information reports on procurement activity in the Australian public sector, which have included publicly available information on consultants:

- Auditor-General Report No.19 2017–18 Australian Government Procurement Contract Reporting; and

- Auditor-General Report No.27 2019–20 Australian Government Procurement Contract Reporting Update.

1.34 These information reports presented publicly available data from public sector procurement activity in a number of ways.57 The publicly available data includes entity reporting on contracts relating to consultancies, including consultancy contract value.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.35 The APS workforce strategy states that the APS will continue to deploy a flexible approach to resourcing that strikes a balance between a core workforce of permanent public servants and the selective use of external expertise. This will mean a continuing mixed workforce approach, where APS employees and non-APS workers are used to deliver outcomes within agencies. In this context, the strategy highlights the value of ensuring that agencies take a structured approach to the use of non-APS employees. The approach adopted by the APS and its agencies has been the subject of ongoing parliamentary interest, with a number of reviews and parliamentary committee inquiries undertaken in recent years, discussed above at paragraphs 1.14–1.24.

1.36 This audit is one of a series of three performance audits undertaken to provide independent assurance to the Parliament on whether entities have established an effective framework for the management of the contracted element of their workforce. Services Australia was selected as one of the APS agencies in this audit series as it is a large and regular user of non-APS personnel. The other audits in this series review the management of contractors by the Department of Defence and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.37 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Services Australia’s arrangements for the management of contractors.

1.38 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has Services Australia established a fit-for-purpose framework for the use of contractors?

- Does Services Australia have fit-for-purpose arrangements for the engagement of contractors?

- Has Services Australia established fit-for-purpose arrangements for the management of contractors?

1.39 The audit examined Services Australia’s framework of policies, plans, processes and guidance that apply to its use, engagement and day-to-day management of contractors.

1.40 The audit did not examine:

- the specific procurement arrangements through which particular contractors are engaged, or the assessment of the value-for-money aspect of specific decisions to engage such personnel instead of APS personnel;

- performance management in terms of specific contracted deliverables as this is part of the management of a contract; or

- the vetting process for contractors undertaken by the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA).

Audit methodology

1.41 Audit procedures included discussions with relevant Services Australia personnel and an examination of the following Services Australia documentation.

- Plans, forecasts and management decisions about Services Australia’s workforce use.

- Guidance available to assist officials’ decision making on whether to engage a contractor instead of an APS resource, including the information to be provided to delegates regarding such choices.

- Nine contracts, used to engage 30 per cent of the contractors engaged in the agency as at 31 October 2021.58 These contracts were examined to establish whether they included clauses to require contracted personnel to comply with Services Australia’s policies and procedures, undertake training, and to meet performance standards. The contracts were identified in two stages. Four contracts were identified as bulk labour hire contracts for service delivery personnel, based on management representations from Services Australia. Five contracts were identified as the top five contracts by number of personnel engaged for Service’s Australia’s ICT workforce.

- Mandatory training requirements, procedures and completion reports for induction.

- Policies, procedures and reporting that supports Services Australia’s compliance with PSPF policies 12–14 that relate to the onboarding, ongoing management (including where staff move within the entity) and offboarding of contracted staff.

- Management reports as evidence of the application of Services Australia’s framework for the management of contractors.

1.42 The audit was open to contributions from the public. The ANAO received and considered one submission.

1.43 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $318,474.

1.44 The team members for this audit were Natalie Whiteley, Kim Murray, Hugh Balgarnie and Sally Ramsey.

2. Framework for using contractors

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Services Australia has established a fit-for-purpose framework for the use of contractors.

Conclusion

Services Australia has established a fit-for-purpose framework for the use of contractors. At the agency level there is guidance which provides clarity regarding the different personnel types, including contractors. Guidance has been developed to assist the largest users of contractors within the agency — its service delivery and ICT areas — determine whether there is an operational requirement for the use of contractors.

2.1 As discussed in paragraph 1.4, the APS Workforce Strategy 2025 released by the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC), identifies that an important element of successful mixed workforce models is a ‘structured approach to the use of non-APS employees’, which includes Australian Public Service (APS) agencies ‘considering where work would be best delivered by an APS employee’. The strategy also states that:

The use of non-APS employees, including labour hire, contractors and consultants, brings different opportunities and risks for APS agencies to manage. Agencies relying on mixed workforce arrangements need to take an integrated approach to workforce planning that includes and best utilises their non-APS workers. This is particularly important where key deliverables are specifically reliant on this non-APS workforce.59

2.2 This chapter considers the framework established by Services Australia to guide decisions to use contractors. The ANAO examined whether guidance had been developed and issued by Services Australia, that:

- provided clarity about the different personnel types that are utilised as Services Australia’s external workforce, including the definition of ‘contractor’, so the most appropriate option is selected for a particular role; and

- assisted officials to determine whether there is an operational requirement for the use of contractors to support the efficient and effective use of resources.

Does Services Australia’s guidance provide clarity regarding the different personnel types, including contractors?

Services Australia’s guidance provides clarity regarding the different personnel types, including contractors.

2.3 Services Australia has provided internal guidance regarding the different personnel types. This guidance is accessible on Services Australia’s intranet, on a dedicated webpage, and includes the definitions for the 11 types of contingent workforce resources utilised by the agency. These are: student placement; system access only; contractor; labour hire; consultant; interpreter; service staff; outsourced (staff); APS secondee; non-APS secondee; and partner.

2.4 Services Australia’s ‘Contingent workforce resources definitions’ intranet page defines the ‘contractor’ and ‘labour hire’ personnel types as follows:

Contractor

A person is a contractor if:

- the person has been supplied to the agency by the person’s own company or another company to do work in and as part of the operations of the agency

- the person is supplied to the agency pursuant to a contract

- the contract specifies the person will supply their labour.

Excludes persons supplied through a labour-hire company or the labour- hire panel.

Labour hire

A person is a labour hire worker if:

- the person has been supplied to the agency by a labour hire company, via a labour hire panel, to do work in and as part of the operations of the agency

- the person has been supplied to the agency pursuant to a contract

- the contract specifies the person will supply their labour.

2.5 As noted in paragraph 1.29, this audit has focused on Services Australia’s workforce resources engaged as contractors and labour hire, and refers to these collectively as ‘contractors’.

Does Services Australia provide guidance on determining whether there is an operational requirement for the use of contractors?

In its provision of guidance on determining whether there is an operational requirement for the use of contractors, Services Australia has focused on the largest users of contractors within the agency — its service delivery and ICT areas. Services Australia has developed arrangements to support workforce planning in its service delivery and ICT workforces which include workforce strategies intended to guide decisions on workforce supply, including for the use of contractors. Decisions to use contractors in all parts of Services Australia’s business are guided by the agency’s Average Staffing Level (ASL) cap and internal budget allocations.

2.6 Services Australia’s Strategic Workforce Plan (2019–2023) recognises its non-APS workforce as part of its workforce mix. The workforce plan identifies that determining an appropriate workforce mix (including contractors) is an important element of maintaining a flexible, capable, and connected workforce across the country to deliver its outcomes.

2.7 An October 2021 brief to Services Australia’s Chief Operating Officer states that:

Work is underway to understand the optimal combination of workforce supply types to meet the capacity, capability and affordability requirements of the Agency. This work includes comparing costs of different workforce supply types, identifying and planning for benefits to be realised through transformation initiatives, and our workforce affordability in the short and medium term. Different combinations of supply types impact differently on capacity, capability, and budget60

2.8 To support the delivery of its Strategic Workforce Plan, during 2020 and 2021 Services Australia developed organisational arrangements to support workforce planning for service delivery61 and for elements of its ICT workforces. These areas are the largest users of contractors within the agency. Services Australia has reported that 3716 (87 per cent) of the 4269 contractors it engaged as at 30 June 202162 were engaged in either the Technology Services Group (2289 personnel) or in service delivery (1427 personnel).63

Organisational arrangements to support workforce planning

2.9 The arrangements developed by Services Australia to support workforce planning in its service delivery and ICT workforces include workforce strategies intended to guide decisions on workforce supply, including for the use of contractors. These arrangements are discussed in Box 5 (the service delivery workforce) and Box 6 (the ICT workforce).

|

Box 5: Service Delivery Optimal Workforce Mix (June 2021) |

|

The Service Delivery Optimal Workforce Mix is intended to guide workforce mix decisions, including commercial labour hire arrangements. It is also intended to guide decisions regarding the most effective use of the employee and contractor budgets allocated to the Customer Service Delivery Group and the Payments and Integrity Group. Services Australia’s Enterprise Business and Risk Committee (EBRC)a approved the Service Delivery Optimal Workforce Mix in June 2021, which included five workforce management principles to guide decisions on whether to hire APS or contractor personnel. The five principles are:

The EBRC agreed to form a multi-disciplinary team to further evolve the data and analysis informing the Optimal Workforce Mix. Services Australia provided the following advice to the ANAO in March 2022 in relation to the implementation of the Optimal Workforce Mix:

|

Note a: The committee provides advice to Services Australia’s Executive Committee on matters related to enterprise-wide risks, issues and operations to ensure effective day-to-day running of the agency.

Note b: Services Australia describes Tier 1 functions as basic support and processing, where services are a short single interaction such as self-service advice or processing a simple claim (for example, proof of identify or residential address updates). Services Australia describes Tier 2 functions as mid-level query/claim, where specialised support is provided to customers that need it, and customers receive advice from customer cohort teams. This might include services that require follow up (for example, additional income information) or extended interactions such as a multiple process service (for example, applying for payments and services to help with the cost of raising a child).

Note c: Services Australia advised the ANAO in March 2022 that ‘during emergency responses such as COVID-19 and natural disasters, the agency makes decisions about which core functions can be paused or slowed whilst the associated staff deliver essential services to the Australian community. Staff who undertake data analysis functions have been diverted to critical surge priorities, and workforce mix-related analysis is recommenced as surge requirements are reduced’.

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia documentation.

|

Box 6: Technology and Digital Programmes Group Workforce Strategy (September 2020) |

|

Services Australia’s Technology and Digital Programmes Group Workforce Strategy adopts a ‘Build, Buy, Borrow and Transition’ model, which states that:

In particular, the strategy states that capability should be borrowed when roles are:

The strategy also proposes a shift in the group’s workforce mix from 50/50 APS/contractor to 70/30 APS/contractor. A workforce sub-strategy document developed in November 2020, states that the group expected to achieve the target 70/30 workforce mix by June 2025. Services Australia documents indicate that in late 2020 the agency’s minister accelerated the time line, requiring the group to meet this target by 2022. In January 2022, Services Australia informed the ANAO that the Technology and Digital Programmes Group is implementing the strategy. Services Australia advised the ANAO that the group’s workforce mix as at 28 February 2022 was 54.5 per cent APS and 45.5 per cent contractors (headcount). In March 2022, Services Australia further advised the ANAO that the group (which was restructured in December 2021):

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia documentation.

2.10 In January 2022, Services Australia informed the ANAO that similar work to develop workforce strategies has not been done in the remaining Services Australia groups because of the smaller non-APS footprint in those groups. Services Australia further informed the ANAO that its refresh of Services Australia’s current Strategic Workforce Plan, planned for later in 2022, will consider whether similar approaches could be applied across the agency.

2.11 Services Australia advised the ANAO in November 2021 that decisions to engage contractors are made within the context of the agency’s: Average Staffing Level (ASL) cap; and internal budget allocations to operational areas, that can be used to purchase, among other things, the services of contractors/labour hire.

3. Arrangements for engaging contractors

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Services Australia has fit-for-purpose arrangements for the engagement of contractors.

Conclusion

Services Australia has established largely fit-for-purpose arrangements for the engagement of contractors. Services Australia has in place a contracting suite that is tailored for the use of contractors and has established centrally managed processes for preparing contracts, including when it engages contractors. Services Australia has established mandatory induction training and systems to monitor and report on the completion of induction training by its entire workforce. The effectiveness of training arrangements is reduced by contractors’ training completion rates and shortcomings in processes to ensure contractors and their managers are aware of mandatory induction training. Services Australia has established policy and processes to support compliance with the majority of core requirements of PSPF Policy 12: Eligibility and suitability of personnel when it engages contractors, the key exception being the requirement to obtain an individual’s agreement to comply with government policies, standards, protocols and guidelines that safeguard resources from harm. By enacting temporary access provisions pending the outcome of pre-engagement eligibility and suitability checks, there is a risk that Services Australia has not met PSPF Policy 12 requirements where there is no assurance process to ensure satisfactory completion of the required checks within a reasonable timeframe.

Recommendations

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: improving the effectiveness of mandatory training arrangements; aligning Services Australia’s personnel security policy with Supporting Requirement 1(c) of PSPF Policy 12; and obtaining assurance that PSPF Policy 12 has been addressed, particularly where Services Australia has used temporary access provisions to address the need for rapid recruitment.

3.1 Services Australia’s contracting templates, induction arrangements and arrangements to support compliance with Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) Policy 12: Eligibility and suitability of personnel are the primary mechanisms through which the agency ensures that contractors are obliged to comply with Services Australia’s policies and Commonwealth legislation, understand these obligations, and are suitable to access Services Australia’s information.

3.2 This chapter considers the arrangements established by Services Australia for engaging contractors. To form a view on the fitness-for-purpose of Services Australia’s arrangements for engaging contractors, the ANAO examined a sample of contracts that Services Australia has used to engage contractors. Well-designed contracts and clauses help operationalise requirements and assist officials to consistently apply them at the point of engagement. They also document the expectations placed on contractors and provide a basis for managing non-compliance. Nine contracts (engaging 30 per cent of the contractors engaged in the agency as at 31 October 2021) were reviewed to establish whether they included clauses requiring the contracted personnel to meet performance standards and to comply with Services Australia’s policies and Commonwealth legislation. In addition, the ANAO examined:

- the induction arrangements established to help contractors understand what their responsibilities are and how to meet their obligations when working for Services Australia; and

- the policies and processes in place to ensure that the eligibility and suitability of contractors to access Australian Government resources has been established at engagement as required by PSPF Policy 12: Eligibility and suitability of personnel.64 Monitoring and reporting on compliance with the policy was also examined.

Does Services Australia have a contracting suite that is tailored for the use of contractors?

Services Australia has in place a contracting suite that is tailored for the use of contractors and has established centrally managed processes for preparing contracts, including when it engages contractors. For the nine contracts for the engagement of contractors reviewed by the ANAO (engaging 30 per cent of the contractor personnel engaged by Services Australia as of 31 October 2021) all contracts: stated that the supplier must ensure that its personnel comply with all procedures and guidelines required by Services Australia; and included references to applicable agency policies, procedures and guidelines. There was some variability in the terms and conditions of the contracts selected for review, with the five ICT contracts not including performance standards. An internal audit from August 2020 states that Services Australia has accepted the risks associated with a lack of performance indicators in the ICT contracts.

3.3 The engagement of a contractor is a procurement process and requires the establishment of a contract between Services Australia and the contractor or the contractor’s employer. Services Australia has established centrally managed processes for preparing contracts, including when it engages contractors. Services Australia undertakes the following process for drafting contracts for contractor personnel.

- The relevant business area raises a new request or variation in the relevant online purchasing and procurement system.

- The Procurement Partnering team (non-ICT procurement) or Technology Sourcing Branch (ICT procurement) reviews the request and supporting documentation and creates the work order or variation.

- The work order or variation and supporting documentation is provided to the business area for approval by the delegate.

3.4 Services Australia’s procurement policy is set out in its Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs). The AAIs and procurement, contract and contract management policies and procedures, and contacts for assistance are available on its intranet.

3.5 As discussed in paragraph 1.29, contractors are engaged by Services Australia ‘to do work in and as part of the operations of the agency’, that is, to work in roles usually subject to the Australian Public Service (APS) Code of Conduct and APS Values. Services Australia has set out, in internal policies, the behavioural requirements and expectations that contractors are expected to meet when working with the agency. These policies include: security; privacy; fraud; workplace health and safety; and conduct and behaviour.

3.6 The ANAO chose to examine the largest (by personnel number) contracts that Services Australia uses to engage personnel as contractors in its service delivery workforce65 and ICT workforce, to determine whether the contracts included clauses that require the contracted personnel to comply with Services Australia’s policies and procedures, and to meet performance standards.

3.7 The ANAO chose to examine contracts within Services Australia’s service delivery workforce and ICT workforce because these workforces were the two largest users of contractors within Services Australia, based on the contractor data provided by Services Australia to the ANAO. Collectively they engaged 3716 (87 per cent) of the 4269 contractors engaged by the agency as at 30 June 2021.66

3.8 The ANAO selected nine contracts for review, comprising four service delivery contracts and five ICT contracts (Table 3.1 below).67 The selected contracts covered 1508 (30 per cent) of the 5032 contractor personnel in the agency as at 31 October 2021.

Table 3.1: Nine Services Australia contracts for the engagement of contractors examined by the ANAO

|

Supplier and Services Australia group/workforce |

Contract start |

Contract end |

Contract value ($million)a |

No. of personnel engaged under contract as at 31 October 2021 |

|

Service delivery contracts |

||||

|

Adecco |

12 Dec 2017 |

30 Jun 2022 |

490.78 |

579 |

|

Chandler Macleodb |

11 Dec 2017 |

30 Jun 2022 |

487.96 |

268 |

|

Chandler Macleodb |

27 Nov 2018 |

30 Jun 2022 |

25.00 |

466 |

|

Hays |

27 Nov 2018 |

30 Jun 2022 |

145.00 |

54 |

|

Technology Services Group contracts |

||||

|

Modis (Consulting & Staffing)c |

1 Jul 2021 |

30 Jun 2022 |

15.97 |

42 |

|

Apis Group P/L |

1 Sep 2020 |

30 Aug 2022 |

28.66 |

39 |

|

Modis (Consulting & Staffing)c |

1 Jul 2021 |

31 Mar 2023 |

11.62 |

24 |

|

GoSourcing P/L |

1 Jul 2021 |

30 Jun 2022 |

7.62 |

21 |

|

SYPAQ Systems P/L |

1 Jul 2021 |

30 Jun 2023 |

7.89 |

15 |

|

Total |

1220.50 |

1508 |

||

Note a: Contract value as reported on AusTender at 16 February 2022.

Note b: The two Chandler Macleod contracts cover the provision of contractors for different job profiles.

Note c: The two Modis contracts cover the provision of different specified personnel.

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia documents.

Analysis of selected contracts

3.9 All nine contracts examined by the ANAO included a requirement for the supplier to ensure that its personnel comply with all procedures and guidelines required by Services Australia.

3.10 The four service delivery contracts state that Services Australia will make the listed policies, procedures and guidelines accessible to personnel on the intranet during the contract term, noting that Services Australia may add or amend such policies, procedures and guidelines. Further, these contracts state that it is the responsibility of contractor personnel to keep abreast of changes made to Services Australia’s policies, procedures and guidelines.68

3.11 The five ICT contracts include references to applicable policies, procedures, and guidelines including ‘those policies, procedures, and guidelines published on’ Services Australia’s intranet. These contracts also require the suppliers to ensure that the personnel supplied to Services Australia under the contract comply with these procedures and guidelines, and that the personnel uphold the values and behave in a manner that is consistent with the APS Values and APS Code of Conduct, as applicable to their work in connection with the contract.

3.12 The four services delivery contracts require the Labour Hire Supplier to ensure that their contractor personnel meet Services Australia’s core performance standards69 that apply to APS staff performing these roles, or meet performance standards as defined in the contract. The five ICT contracts do not contain any performance standards or indicators for the work to be performed under the contract. In March 2022, Services Australia advised the ANAO that: