Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Critical Infrastructure Protection Policy

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on whether the Department of Home Affairs (the department), as policy and regulatory lead for critical infrastructure protection coordination, has an effective approach to protecting Australia’s assets of national significance and supporting asset owners and operators to improve their resilience to attacks.

- The potential for an attack that degrades or disables a critical infrastructure asset has been identified by industry and governments in Australia and abroad.

Key facts

- Overseas terrorist attacks in 2001 and 2002 prompted formal government and industry engagement on critical infrastructure asset threat preparedness and response in Australia.

- The department estimates that the 168 assets registered as being critical infrastructure will increase ten-fold as a result of legislative changes in 2021.

What did we find?

- The department’s administration and regulation of critical infrastructure protection policy was partly effective.

- The department had partly effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy.

- Improvements are required on integrated risk management, development of stakeholder engagement strategy, and performance measurement.

- The department’s administration of compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements is partly effective.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made seven recommendations to the department aimed at: the use of risk management to inform decision-making; establishing an engagement strategy; having appropriate performance measurement; improving the department’s existing framework to manage compliance; and support and review the effective use of all available regulatory tools.

- The department agreed to all seven recommendations.

11

sectors covered by the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018, expanded from four in 2021.

28 of 36

measures of control effectiveness indicators did not align with enterprise level critical infrastructure risk reporting.

15 of 22

policy and procedural documents to support critical infrastructure related compliance activities were not finalised and approved.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Ensuring the security and resilience of Australia’s critical infrastructure is a responsibility shared by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments, infrastructure owners and operators.

2. The Department of Home Affairs (the department) is the lead Australian Government agency responsible for the administration of critical infrastructure policy and regulation. The Critical Infrastructure Centre was established in 2017 to coordinate the management of risks to Australia’s critical infrastructure and deliver more coordinated national security assessments to inform foreign investment decisions in significant and complex cases.

3. In 2018, legislative coverage of critical infrastructure security was expanded from being considered primarily under the Foreign Investment and Takeovers Act 1975, to include regulation under:

- the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SoCI Act); and

- amendments to Part 14 of the Telecommunications Act 1997, or Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms (TSSR).

4. On 2 December 2021, the SoCI Act was amended to increase its coverage from four to 22 asset classes, across 11 sectors. These amendments also introduced mandatory cyber incident reporting and a regime to respond to cyber incidents, the ‘government assistance powers’. Additional amendments to the SoCI Act commenced on 2 April 2022 including:

- a requirement for critical infrastructure assets to adopt and maintain a risk management program; and

- providing the government with the power to declare certain critical infrastructure assets as Systems of National Significance to which Enhanced Cyber Security Obligations may apply.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The potential for an attack that degrades or disables a critical infrastructure asset has been identified by industry and governments in Australia and abroad. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on whether the department, as policy and regulatory lead for critical infrastructure protection coordination, has an effective approach to protecting Australia’s assets of national significance, and supporting asset owners and operators to improve their resilience to attacks.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s administration and regulation of critical infrastructure protection policy. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high‐level criteria were applied.

- Has the department established effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy? (Chapter 2)

- Does the department effectively administer compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements? (Chapter 3)

Conclusion

7. The department’s administration and regulation of critical infrastructure protection policy was partly effective.

8. The department has partly effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy. Implementation of critical infrastructure related risk assessments and reporting was not captured in risk documentation. The effectiveness of the department’s stakeholder coordination arrangements is reduced by not having an engagement strategy and providing limited support to other critical infrastructure regulators. The department’s performance framework as it related to critical infrastructure was not adequate, with performance statements, regulatory performance assessment, and use of internal measures to inform policy and regulation requiring improvement.

9. The department’s administration of compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements is partly effective. The department’s compliance framework does not reflect existing responsibilities or compliance requirements. Compliance activities are not supported by approved procedures or systems controls. The department has not established a risk‐based decision framework for achieving compliance outcomes or demonstrating its impact on asset security or resilience. The department does not have a process of effectively reviewing its use of regulation tools, impact on industry or to inform continuous improvement.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

10. The department identified key critical infrastructure risks and had appropriate governance arrangements to assess and assign responsibility for these risks. The department’s critical infrastructure risk management does not represent an integrated approach to risk management between its enterprise and operational, legislative and policy functions. Implementation of critical infrastructure related risk assessments and reporting was not captured in risk documentation, which reduces its use to inform business planning, legislative reform, and policy decisions. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.23)

11. While the department undertakes coordination activities with key stakeholders, including through some long-established forums, it does not have a documented stakeholder engagement strategy to identify the engagement purpose, means by which engagement occurs or scenarios are managed, or the basis for there being more established information-sharing arrangements with some key stakeholders than with others. (See paragraphs 2.26 to 2.35)

12. The department’s performance framework requires improvement. Critical infrastructure related content in the department’s 2020–21 performance statements is not adequate. The department did not assess its critical infrastructure functions against the Regulator Performance Framework. The department has established internal performance reporting but could improve its use of measures in the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy to inform policy development and regulation. (See paragraphs 2.38 to 2.51)

Compliance activities

13. The department has established a compliance framework comprised of the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy, Compliance Strategy and Administrative Guidelines. This framework would be enhanced by updating documents in the framework to align with and clarify the department’s existing responsibilities and regulatory posture. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.7)

14. The majority of policy and procedural documents (15 of 22) to support possible critical infrastructure related compliance activities were drafted, but not finalised and approved, or included in the department’s policy and procedural repository. A lack of procedures, or procedures that remain in draft, increases the risk of inconsistency in administration and decision-making. The department does not have an established process to ensure that appropriately trained officials are engaged in investigations under critical infrastructure regulations. Classified network and critical infrastructure-related system security controls do not meet the requirements to mitigate the risk of unauthorised access. (See paragraphs 3.10 to 3.20)

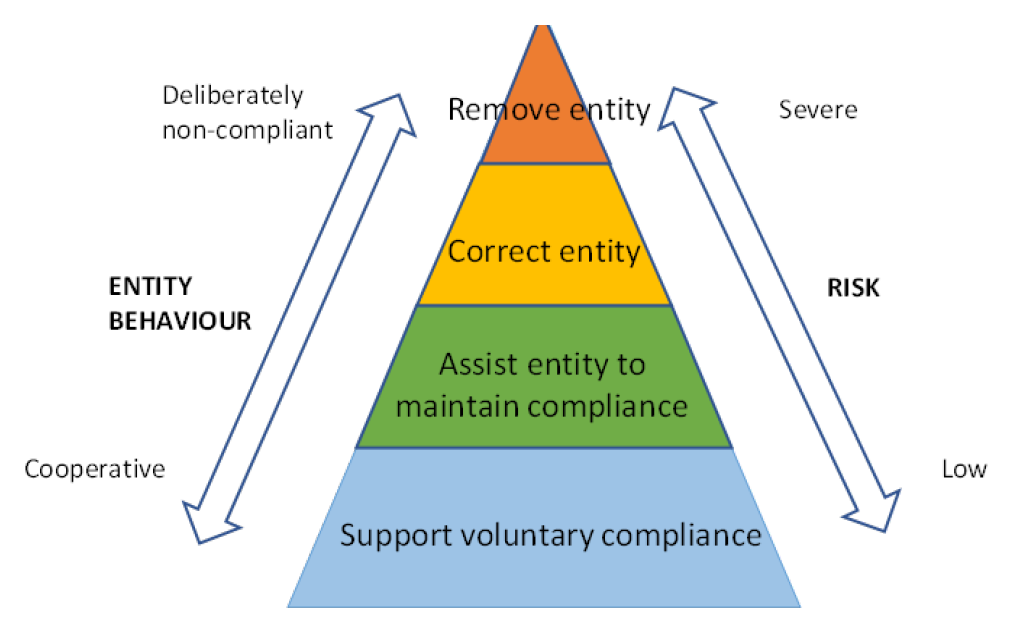

15. The department’s use of regulatory tools is not always consistent with legislative and procedural requirements, and approved procedures or decision records do not exist for all compliance activities and outcomes. Use of regulatory tools was consistent with the department’s documented regulatory posture. Decisions on whether to escalate to higher tiers of the regulatory compliance model were not supported by approved procedures, processes, or documented analysis of the administrative or financial burden associated with an escalation of compliance activity. (See paragraphs 3.23 to 3.29)

16. The department does not have an established process to obtain assurance of regulatory compliance. This limited the department’s capacity to demonstrate that it has a proportionate and effective approach to resolving non-compliance, or has improved the security or resilience of critical infrastructure assets. (See paragraphs 3.30 to 3.44)

17. The department has not established a process to effectively review regulatory tool use, impacts on industry, or lessons learned to inform continuous improvement. (See paragraphs 3.45 to 3.46)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.24

The Department of Home Affairs ensures that implementation of critical infrastructure related risk assessments and reporting is appropriate to inform policy and regulatory decisions.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.36

The Department of Home Affairs establish an engagement strategy to document how it will coordinate with stakeholders with shared responsibility for critical infrastructure security and resilience.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.52

The Department of Home Affairs ensure performance measurement:

- in its corporate plan is adequate and measurable;

- aligns with the Regulator Performance Guide; and

- is used to inform policy and regulatory improvements.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.8

The Department of Home Affairs revise or replace the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy with documentation that reflects current policy, regulatory responsibilities and posture, and outlines its application by the department in relation to other critical infrastructure asset sector policy leads and regulators.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.21

The Department of Home Affairs support effective use of the full suite of available critical infrastructure related regulatory tools by having in place procedures that:

- are finalised, approved and lodged on the internal policy and procedural repository;

- ensure that trained officials are appropriately engaged in investigations; and

- align with the Protective Security Policy Framework and Information Security Manual requirements.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.39

The Department of Home Affairs approve, apply and monitor consistent use of policies, procedures and processes to:

- trigger, triage and manage escalated use of critical infrastructure compliance powers, including by making better use of its information gathering, and investigatory powers where national security concerns have been identified; and

- revise its risk approach and implement processes that enable effective assessment, prioritisation and management of non-compliance risks.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.47

The Department of Home Affairs evaluate, monitor, and report on:

- the extent to which regulatory tools are used to effectively improve security and resilience of critical infrastructure assets to risks; and

- implementation of actionable items in strategies, reviews and lessons learned for which it is responsible and how they contribute to intended outcomes.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

18. The department’s summary response is provided below and its full response is included at Appendix 1. At Appendix 2, there is a summary of improvements that were observed by the ANAO during the course of the audit.

The Department of Home Affairs (the Department) accepts all of the ANAO’s recommendations. Implementation of the 2021 and 2022 amendments to the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 will be informed by ANAO’s audit recommendations. The creation of the Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre in the Department will bring together a coordinated all hazards approach to the protection of Australia’s critical infrastructure. This will be undertaken both by direct regulatory responsibilities and in partnership with both industry, other Commonwealth regulators, as well as, state and territory governments.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

Program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian society and its economy are supported by a network of interconnected infrastructure assets across a broad range of industry sectors. The Australian Government defines critical infrastructure as:

those physical facilities, supply chains, information technologies and communication networks which, if destroyed, degraded or rendered unavailable for an extended period, would significantly1 impact the social or economic wellbeing of the nation or affect Australia’s ability to conduct national defence and ensure national security.2

1.2 Threats such as natural disasters, pandemics, sabotage, and espionage have the potential to significantly disrupt critical infrastructure. Secure and resilient infrastructure ensures continuous access to services that are essential for everyday life, such as food, water, health, energy, communications, transport, and banking. A disruption to any of these critical infrastructure sectors could have serious implications for business, government, and the community.

1.3 The Commonwealth, state and territory governments have different responsibilities for critical infrastructure depending on the sector or nature of the threats being mitigated. Responses to a threat can involve the asset owner and operator, technical and operational lead for that jurisdiction, and emergency services or law enforcement. Coordination among entities is therefore required to prepare and respond to critical infrastructure threats.

1.4 The Department of Home Affairs (the department) is the lead Australian Government agency responsible for the administration of critical infrastructure policy and regulation.

Critical infrastructure policy and regulation

Regulatory options

1.5 Governments may approach regulation through either legislative or non-legislative models. Non-legislative models involve achieving regulatory ends through non-legislative means, such as guidelines on market participants3, and can include light touch or principles-based regulation4, self-regulation5 and quasi-regulation.6 Legislated approaches involve either co-regulation7 or explicit government regulation, which is used where ‘there is a high perceived risk or public interest and achieving compliance is seen as critically important’.8

1.6 Australian Government regulators are empowered by, and subject to, a range of legal and other requirements including the following.

- Legislation that establishes the regulatory powers of an entity, and underpinning policies and relevant directions.

- The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 along with delegated legislation such as the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014, the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, and the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy.

- The Australian Government Regulator Performance Framework — introduced in October 2014 — to encourage regulators to achieve their objectives while minimising their impact on regulated entities. On 1 July 2021, the Regulator Performance Guide9 replaced the 2014 Framework and included a transition year for regulators to assess their approach to complying with its requirements.

1.7 The Australian Government’s critical infrastructure regime is comprised of a combination of light touch, co-regulation and explicit government regulation.

Overview of the Australian Government critical infrastructure regime

1.8 Terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001, and Indonesia in 2002, were the catalyst for formal engagement between the Commonwealth, state and territory governments, and industry on how to prepare for and respond to threats against critical infrastructure assets. In 2003, the Australian Government established a Trusted Information Sharing Network as the primary engagement mechanism for business and government information sharing, and resilience building initiatives on critical infrastructure.

1.9 Prior to the introduction of critical infrastructure focussed policy and legislation in 201810, national security threats to assets were primarily assessed under the Foreign Investment and Takeovers Act 1975 (FATA). Under the FATA, certain proposed foreign investments, including those related to critical infrastructure assets require approval from the Treasurer. Conditions may be imposed, existing conditions may be varied, or a divestment from an approved investment may be required where a national security risk emerges.

1.10 The Treasury remains the lead entity for assessments under the FATA. The department provides national security advice to support decisions made under the FATA, and may impose and enforce conditions on approved applications. In 2020–21, the department received 943 applications for review from the Treasury, an increase from the 640 received during 2019–20.

Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy

1.11 The Australian Government Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy was released in May 2015.11 The strategy comprises a policy statement and plan, and sets out the Australian Government’s policy position that:

- critical infrastructure is essential to Australia’s economic and social prosperity;

- resilient critical infrastructure plays an essential role in supporting broader community and disaster resilience;

- businesses and governments have a shared responsibility for the resilience of critical infrastructure, requiring strong partnerships; and

- all states and territories have their own critical infrastructure programs that best fit the operating environments and arrangements in each jurisdiction.

1.12 The policy statement sets out an approach based on non-regulatory business–government partnerships, mature risk management, and effective information sharing. The policy statement required the strategy to be reviewed in 2020.

1.13 The Critical Infrastructure Centre was established in 2017 to coordinate the management of risks to Australia’s critical infrastructure and deliver more coordinated national security assessments to inform foreign investment decisions in significant and complex cases. In December 2017, critical infrastructure policy, regulatory and strategy functions were transferred to the department and the Critical Infrastructure Centre became a division within the department.

Critical infrastructure legislation

1.14 In 2018, legislative coverage of the security of critical infrastructure expanded from the FATA to include:

- the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SoCI Act), which commenced on 11 July 2018; and

- the amendments to Part 14 of the Telecommunications Act 1997, or Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms (TSSR), which commenced on 18 September 2018.

1.15 The legislation in paragraph 1.14 enables the government to obtain information to undertake risk assessments in relation to critical infrastructure, and gives government the power to issue directions to address national security risks if necessary.

Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018

1.16 The SoCI Act was introduced to ‘strengthen the Government’s capacity to manage the national security risks of espionage, sabotage and coercion arising from foreign involvement in Australia’s critical infrastructure’.12 The SoCI Act defines a critical infrastructure asset13, and what assets can14, and must not be prescribed as being ‘critical’.15 The SoCI Act has three measures to manage national security risks related to critical infrastructure.

- The Register of Critical Infrastructure Assets (the Register), provides the government visibility of who owns and controls the assets.16

- The information gathering power, provides the ability to obtain more detailed information from owners and operators of assets in certain circumstances.

- The Ministerial directions powers, provide the ability to intervene and issue directions in cases where there are significant national security concerns that cannot be addressed through other means.

1.17 In 2020, the Australian Government approved changes to the critical infrastructure regulatory regime on the basis that the SoCI Act did not enable it to impose requirements on entities to protect their assets, and an over-reliance on the FATA to manage risks arising from foreign ownership. In 2020, the department sought public contributions on the design of ‘an enhanced regulatory framework, building on existing requirements under the SoCI Act’.17

1.18 In December 2020, the Australian Government introduced a Bill that included amendments to the SoCI Act. These amendments would enact the regulatory framework that was the subject of public consultation. The Bill proposed mandatory incident reporting, an expanded application of the register of critical infrastructure sectors and assets, powers to obtain ownership, operational and risk management information, and powers to respond to serious cyber incidents. The amendments to the SoCI Act were described when they were introduced, as being ‘underpinned by enhancements to Government’s existing education, communication and engagement activities, under a refreshed Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy’.18

1.19 In December 2020, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) commenced an inquiry into the Bill that would amend the SoCI Act, as well as a statutory review into the Act.19 In September 2021 the PJCIS published an Advisory Report on the concurrent reviews of the Bill and statutory review of the SoCI Act and made 14 recommendations. Among the recommendations was that the Bill be split in two so that government assistance20 and an expanded definition of critical infrastructure sectors and assets could be legislated in the shortest time possible.

1.20 An additional $42.4 million over two years from 2021–2221 was included in the 2021–22 Budget for ‘Protecting Critical Infrastructure and Systems of National Significance’.

- In September 2021, the Critical Infrastructure Centre was re-branded as the Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre.

- In December 2021, amendments to the SoCI Act expanded the asset classes covered from four to 22 across 11 sectors to include: communications, financial services and markets, data storage and processing, defence industry, higher education and research, energy, food and grocery, health care and medical, space technology, transport, and water and sewerage.22 The department estimated that it would have ten times the number of assets on its Register under the SoCI Act as a result of this change.

- Also in December 2021, the Australian Government commenced consultations on further amendments to the SoCI Act.23

- In March 2022, the PJCIS published an Advisory Report on the proposed further amendments to the SoCI Act and made 11 recommendations.24

1.21 In March 2022, the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure Protection) Act 2022 was passed by the Parliament. Details of changes to Australian Government critical infrastructure legislation are in Appendix 3.

Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms

1.22 The TSSR established a regulatory framework ‘to better manage the national security risks of espionage, sabotage and foreign interference to Australia’s telecommunications networks and facilities’.25 The purpose of the TSSR is to:

- introduce a comprehensive risk-based regulatory framework to better manage national security risks of espionage, sabotage and foreign interference to Australia’s telecommunications networks and facilities; and

- better protect networks, and the confidential information stored on and carried across them, from unauthorised interference and access.

1.23 The aim of the TSSR is to encourage early engagement on proposed changes to networks and services that could give rise to national security risks, and to facilitate collaboration on the management of those risks. Key elements of the TSSR include:

- a security obligation that requires all carriers, carriage service providers and carriage service intermediaries to do their best to protect networks and facilities from unauthorised access or interference26;

- a notification obligation that requires carriers and nominated carriage service providers to notify the Australian Government of planned changes to their networks and services that are likely to have a material adverse effect on their capacity to comply with the security obligation;

- that the Secretary of the department can obtain information and documents for the purpose of assessing carriers and carriage service providers compliance with their security obligations; and

- that the Minister for Home Affairs can direct a carrier, carriage service provider or carriage service intermediary to:

- not use or supply carriage services if the Minister considers the use or supply prejudicial to national security; and

- do, or not do, a specified thing that is reasonably necessary to protect networks and facilities from national security risks.

1.24 In September 2020, the PJCIS commenced a statutory review of the operation of the TSSR.27 The PJCIS published its report on the statutory review in February 2022 and made six recommendations.28

1.25 Figure 1.1 illustrates the sectors covered by Australian Government critical infrastructure policy and legislation.

Figure 1.1: Australian Government critical infrastructure policy and legislation sector coverage

Note: Sectors illustrated in the figure as being relevant to particular legislation may not represent all asset classes within them. For example, while the transport sector consists of public transport, aviation, maritime ports, freight infrastructure, and freight services, only specific maritime ports were captured under the 2018 SoCI Act and may be subject to an expanded number of transport asset types under the register following 2021 amendments to the SoCI Act.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

Critical infrastructure security and resilience roles

1.26 The Commonwealth, state and territory governments, and industry, have a shared responsibility to ensure the security and resilience of critical infrastructure, and to prevent, prepare, respond to, and recover from all hazards. Each participant has different roles as shown in Table 1.1. Further detail of the entities involved, and key policies and legislation is in Appendix 3.

Table 1.1: Critical infrastructure roles

|

Role |

Commonwealth |

States and territories |

Industry |

|

Policy lead |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Service provider |

✔a |

✔b |

✔ |

|

Operational lead |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Regulator |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Owner/Operator |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Key: ✔ = role exists. ✘ = role does not exist.

Note a: For example, weather forecasting and cyber protection advisory notice provision.

Note b: For example, managing threats to life and property, preparing, and responding to emergencies, ensuring law and order, and delivery services such as health care and water.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

1.27 The department, as the lead agency for ensuring the protection of critical infrastructure, must coordinate, complement, and support the programs and activities of all these participants. When the Critical Infrastructure Centre and SoCI Act were established, it was recognised that the Australian Government would have limited powers to implement risk management strategies, and monitor and enforce compliance, and should first leverage existing state and territory regimes to conduct these activities.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.28 The potential for an attack29 that degrades or disables a critical infrastructure asset has been identified by industry and governments in Australia and abroad. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on whether the department, as policy and regulatory lead for critical infrastructure protection coordination, has an effective approach to protecting Australia’s assets of national significance, and supporting asset owners and operators to improve their resilience to attacks.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.29 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s administration and regulation of critical infrastructure protection policy. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Has the department established effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy?

- Does the department effectively administer compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements?

Audit methodology

1.30 The following actions were done to address the audit objective.

- The audit team examined departmental documentation with a focus on:

- risk inputs, including systems and review of risk ratings and products;

- processes, procedures, guidance and documentation developed to support, or as a result of, compliance activities;

- departmental data used to inform reporting on compliance activities; and

- arrangements with partner agencies.

- The audit team undertook system mapping and control testing over key systems, including a review of departmental assurance over the quality and integrity of inputs from other entities.

- The audit team undertook case studies into instances of non-compliance involving the use of enforcement activities.

- The audit team conducted meetings with relevant departmental staff and stakeholders.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $349,000.

1.32 The team members for this audit were Glen Ewers, Rebecca Helgeby, Jessica Kanikula, Edwin Apoderado, Ji Young Kim, and Alex Wilkinson.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Home Affairs has effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy, including risk identification and management, stakeholder engagement and an appropriate performance framework.

Conclusion

The department has partly effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy. Implementation of critical infrastructure related risk assessments and reporting was not captured in risk documentation. The effectiveness of the department’s stakeholder coordination arrangements is reduced by not having an engagement strategy and providing limited support to other critical infrastructure regulators. The department’s performance framework as it related to critical infrastructure was not adequate, with performance statements, regulatory performance assessment, and use of internal measures to inform policy and regulation requiring improvement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at the use of risk management to inform decision-making, establishing an engagement strategy, and having appropriate performance measurement.

2.1 Critical infrastructure policy, regulatory and strategy functions have been the responsibility of the Department of Home Affairs (the department) since December 2017. The Australian Government’s Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy30 outlines how the department will support asset owners and operators to effectively manage reasonably foreseeable and unforeseeable risks to the continuity of their operations.

2.2 Implementation of the government’s critical infrastructure policy objectives requires effective governance arrangements that reflect the risk environment, and the importance of coordination between the different levels of government and asset owners. To assess the extent to which the department had effective governance arrangements to administer critical infrastructure protection policy, the ANAO examined the material components of the department’s critical infrastructure related governance arrangements, which comprise its risk identification and management processes, stakeholder engagement coordination, and performance framework.

Are risks to critical infrastructure assets identified and managed effectively?

The department identified key critical infrastructure risks and had appropriate governance arrangements to assess and assign responsibility for these risks. The department’s critical infrastructure risk management does not represent an integrated approach to risk management between its enterprise and operational, legislative and policy functions. Implementation of critical infrastructure related risk assessments and reporting was not captured in risk documentation, which reduces its use to inform business planning, legislative reform, and policy decisions.

2.3 Regulators with clear and comprehensive processes to assess risk are positioned to allocate their resources towards those areas of greatest impact. The department’s enterprise risk management framework aims to fully integrate risk management in planning and decision-making activities. Critical infrastructure risk is addressed by the department through:

- enterprise level risks;

- business area annual planning;

- informing draft legislation to address national security risks associated with Australia’s critical infrastructure; and

- critical infrastructure protection coordination in the:

- provision of advice to the Treasury on foreign investment an acquisition applications; and

- engagement with the critical infrastructure industry and government stakeholders to support and understand asset resilience and incident response.

Enterprise level

Assessment and reporting alignment

2.4 In 2020–21, the department identified and assessed three enterprise level risks that addressed critical infrastructure.31 The main enterprise risk is ‘critical infrastructure’, which is ‘[a]n attack on critical infrastructure [that] significantly disrupts national operations, causing damage to the economy, public safety, and national security.’32 The other two enterprise risks address cyber and disasters.

2.5 Enterprise risk governance arrangements include reporting to the following internal governance forums:

- annual updates and a dashboard of all enterprise risks to the Executive Committee;

- quarterly updates and a dashboard, and three detailed reviews to the Enterprise Operations Committee and the Risk Committee; and

- enterprise risk update as a standing item for the department Audit and Risk Committee.

2.6 In 2020–21, reporting on enterprise risks and controls provided the accountable authority with visibility of critical infrastructure enterprise risks, and was consistent with the arrangements outlined above in paragraph 2.5.

2.7 Updates to the department’s Audit and Risk Committee on enterprise level risks included information on risk ratings, threats, consequences, related risks, the effectiveness of controls, and collaboration with key stakeholders. Each enterprise risk is assigned a risk owner. Controls for each risk are rated according to their effectiveness at mitigating the risk after the control has been applied. These ‘control effectiveness ratings’ are also included in quarterly reporting, and represent the last assessed performance of the control. Figure 2.1 illustrates key components of the department’s enterprise level risk management framework and how it has been applied to its critical infrastructure risk.

Figure 2.1: The department’s enterprise risk management framework and critical infrastructure strategic risk management in 2020–21

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.8 In November 2021, the Executive Committee requested that quarter four reporting be reviewed to ensure it presents an accurate and realistic picture, and the outcomes of the review are reported to the Secretary. Subsequently, revisions made to the critical infrastructure enterprise risk report took the number of ineffective control ratings for the enterprise level critical infrastructure risk from one to seven of the eleven ratings33, and the critical infrastructure risk was rated as ineffective.34

2.9 While the department had identified the risk to critical infrastructure at the enterprise level, supporting documentation did not effectively address the risk.

- Controls did not align with activities or risk ratings listed against them.35

- There was no reporting against the 36 measures of control effectiveness in each quarter, or for the reporting period.

- Most of the 11 control effectiveness ratings were inconsistent with the rating matrix in the Strategic and Enterprise Risk Management Plan and Reporting Handbook and not substantiated by reporting against each control.

2.10 Risk information submitted to governance bodies is dependent on the quality and maintenance of information included in risk reporting. Inconsistent and unsubstantiated content in risk reports reduces the department’s effectiveness in informing critical infrastructure related policy, or regulatory decisions.

Shared risk

2.11 The Commonwealth, state and territory governments, and industry have a shared responsibility to address the risks to critical infrastructure.36 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy requires the department to implement arrangements to understand and contribute to the management of shared risks.37 The department’s risk management framework considers shared risks to include:

- ensuring visibility of risk through proactive information exchange;

- designing, deploying, and monitoring and reporting effectiveness of controls and risk treatments; and

- establishing mechanisms to share the burden of risk when it is realised.

2.12 The department’s processes for addressing the shared risk relating to critical infrastructure did not include a number of aspects of its risk framework. Internal reporting for quarter four 2020–21 addressing the critical infrastructure enterprise level risk:

- identified only two operational stakeholders as external shared risk owners;

- contained no reference to state or territory governments, or other operational and regulatory bodies; and

- referred to the department having limited visibility of information held by one of the shared risk owners as a basis for assessing the overall risk rating for the critical infrastructure enterprise level risk as ineffective.

2.13 Engagement in different fora and with specific stakeholders to achieve departmental objectives is referred to in enterprise level critical infrastructure related risk assessments. Critical infrastructure related risk reporting also refers to activities that assess or manage shared risks. Reporting that relates to critical infrastructure regulatory or policy responsibilities is limited to legislative and policy reform, and foreign investment and acquisition assessments, and excludes:

- other Australian Government regulatory bodies in critical infrastructure sectors;

- state and territory government agencies with critical infrastructure policy, operational or regulatory responsibilities; and

- critical infrastructure asset owners and operators.

Business planning

2.14 Management of risk at the operational level should effectively integrate with the enterprise level risk framework. The Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC) of the department is responsible for the administration and regulation of critical infrastructure policy. The 2020–21 and 2021–22 business plans for the CISC38 included:

- key risks that aligned with enterprise level critical infrastructure strategic risk documentation; and

- controls that aligned with the enterprise level critical infrastructure risk.

2.15 Management meetings were used to progress business plan outputs and did not consider the impact activities were having on mitigating identified risks.

Advice on the legislative framework

2.16 The department’s risk framework should inform its policy advice related to critical infrastructure regulation. The Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SoCI Act) is designed to manage national security risks arising from foreign involvement in Australia’s critical infrastructure. It initially covered the electricity, gas, water, and ports sectors on the basis that the degradation or disruption of assets in these sectors was most likely to have a negative impact on the Australian economy or security.

2.17 The department is also required under the Telecommunications Security Sector Reforms (TSSR) to assess national security risks to critical telecommunications infrastructure arising from proposed changes notified by providers (use of these powers is discussed further in chapter 3, paragraphs 3.23 to 3.29). The department has provided advice and reported on the use of regulatory powers under the SoCI Act and TSSR. The assessed risks and advice did not result in adjustments to critical infrastructure risk assessment at the enterprise level, in business planning or in any other risk assessment.

Policy lead activities

2.18 The department has adopted a risk-based approach to prioritising compliance activities and allocating resources under both the SoCI Act and the TSSR (see paragraphs 3.31 and 3.32). Activities conducted under the compliance model did not result in adjustments to enterprise or business plan risk assessments and ratings based on the outcome of these activities. Outcomes of these activities were not integrated into the enterprise level critical infrastructure strategic risk summary reporting, or its supporting documentation.

2.19 Under the Foreign Investment and Takeovers Act 1975 (FATA) arrangements, the department is required to support the management of risk to critical assets. The department provides advice on foreign investment and acquisition applications. Departmental advice is based on the application of a risk assessment procedure, which supports the consistent assessment of the threat, vulnerability, and consequences of what was proposed in the applications, to the continued operation of critical infrastructure assets and services.

2.20 A review of a sample of FATA assessments by the ANAO found that the department was consistent with its procedural requirements. The department also provided advice, through the Foreign Investment Strategic Analysis Team, on national security risks associated with applications.

2.21 Advice provided by the department on critical infrastructure risks included in individual foreign investment assessments was not used to inform adjustments to overall assessments of related enterprise risks or the effectiveness of controls. For example, reporting provided to the governance forums outlined above in paragraph 2.5 on the critical infrastructure enterprise risk, did not reflect intelligence gained from individual foreign investment assessments, or trends that would inform the management of potential national security concerns.

2.22 The 2015 Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy includes two core policy objectives that relate to the department’s role in overseeing industry risk management. These are for critical infrastructure owners and operators to be effective in managing:

- reasonably foreseeable risks to the continuity of their operations, through a mature, risk-based approach; and

- unforeseen risks to the continuity of their operations through an organisational resilience approach.39

2.23 The department provides the Organisational Resilience Health Check on its website40 as a tool for industry to self-assess organisational resilience capability. Responses are confidential and are not recorded by the department. The tool is not referred to in any enterprise risk documentation as a means by which threat preparedness or responsiveness could be improved. Use of the health check is not monitored by the business area responsible for critical infrastructure.

Recommendation no.1

2.24 The Department of Home Affairs ensures that implementation of critical infrastructure related risk assessments and reporting is appropriate to inform policy and regulatory decisions.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.25 The department agrees to recommendation 1 of the report. The establishment of the Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC) on 1 September 2021 has brought together the critical infrastructure regulatory and security risk assessment functions of the department. The CISC continues to enhance its risk assessment framework to support regulatory and policy decisions with a view to capabilities to all 11 critical infrastructure sectors — following passage of the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Act 2021.

Have effective coordination arrangements with key stakeholders been established?

While the department undertakes coordination activities with key stakeholders, including through some long-established forums, it does not have a documented stakeholder engagement strategy to identify the engagement purpose, means by which engagement occurs or scenarios are managed, or the basis for there being more established information-sharing arrangements with some key stakeholders than with others.

2.26 The department’s management of critical infrastructure protection relies on coordination with other Commonwealth entities, state and territory governments, asset owners and operators (see paragraph 1.26). The 2015 Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy includes the following Australian Government policy positions:

- businesses and governments have a shared responsibility for the resilience of our critical infrastructure, requiring strong partnerships; and

- all states and territories have their own critical infrastructure programs that best fit the operating environments and arrangements in each jurisdiction.

2.27 The department has stated that the update41 to the 2015 Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy will:

- bring disparate work across government together. This helps create a consistent approach to improving critical infrastructure security and resilience. It will give holistic support to owners and operators across the threat spectrum; and

- provide a framework for how we work with state and territory governments and industry.42

Engagement approach

2.28 The department does not have an engagement strategy in place for critical infrastructure that identifies the purpose and means for engagement, relevant stakeholders, or distinguishes when the department is undertaking a policy or regulatory role. Sector specific strategies were developed for four sectors to inform engagement on legislative reforms. These strategies were discontinued before the reform engagement had concluded and replaced with an engagement approach that was not industry specific. The sector specific strategies did not relate to the department’s engagement on its legislated regulatory functions.

2.29 The department participates in key forums to engage with government and industry stakeholders listed in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Summary descriptions of key critical infrastructure-related engagement

|

Forum |

Summary description |

|

Critical Infrastructure Advisory Council (CIAC) |

The CIAC is responsible for leadership and setting the strategic direction for the Trusted Information Sharing Network (TISN). Participants include select TISN members (sector chairs), states and territories and Australian Government representatives and meetings are used to discuss critical infrastructure issues. CIAC meeting frequency has been inconsistent, and since 2017 has ranged from meetings occurring 18 months apart to being held monthly. |

|

TISN sector groups |

Established in 2003, the TISN comprises eight sector-based groups that cover the following critical infrastructure sectors: water services; energy; banking and finance; food and grocery; communications; health; transport; and Commonwealth. Meeting frequency has been inconsistent for each sector group. One sector group had not met for two years and had a Terms of Reference dated 2013, while others met on a monthly basis. |

|

All Hazards Community of Interest |

These meetings are co-chaired by Emergency Management Australia and the CISC on a weekly basis, and cover common and shared hazards, such as bushfires and weather events. The meetings are open to all TISN members and provide a forum for government and industry to exchange information and discuss pressing critical infrastructure issues. |

|

Taskforce meetings |

Meetings are held as required, to discuss specific threats that warrant a coordinated response. For example, the Supermarket Taskforce, whose members include representatives from states and territories, senior government executives and industry sector members, met to discuss challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the Bushfire Taskforce met in response to threats from bushfires in the summer of 2019–20. While these meetings were not specifically about critical infrastructure assets, they did include items related to them. |

|

Legislative and policy reform meetings |

In 2020–21, the department completed public and targeted stakeholder consultation on the development of amendments to the SoCI Act, the next Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy, and an updated TISN. On the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Bill 2020 (SoCI Bill), consultation included the release of discussion papers and an exposure draft, workshops and bilateral meetings. ‘These consultation processes were intended to guide the development of the framework proposed in the SoCI Bill, essentially being the first step in the co-design process at the foundation of the regulation’. |

|

Bilateral engagement |

Official level bilateral engagement occurred between the department and stakeholders with policy, operational or regulatory responsibilities in critical infrastructure sectors. |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.30 The engagements listed in Table 2.1 focussed on sharing information on issues such as cyber, natural hazard forecasting, and supply chain updates. The meetings did not provide a strategic approach to ensuring critical infrastructure policy outcomes were met, or provide a platform for the sharing of better practice, setting sector expectations, or distributing information to assist other Australian Government, state or territory critical infrastructure regulators to pursue possible instances of non-compliance under their regulatory powers. While components of existing policy and forum terms of reference covered some aspects of the department’s critical infrastructure related responsibilities, they did not represent an engagement strategy that comprehensively covers:

- when engagement is in a policy or regulatory capacity;

- how the department will support other regulatory bodies and industry to improve critical infrastructure resilience and security; or

- information sharing arrangements with relevant regulatory bodies.

2.31 The CIAC and seven of eight TISN sector groups have terms of reference that align with the matters covered in meetings held since 2017. In 2021, a TISN online platform was established, and membership reset to align with the expanded sectors covered under the SoCI Act. The TISN was described as still being a forum for the department to engage in a non-regulatory capacity with:

stakeholders from across the critical infrastructure community, including critical infrastructure owners and operators, supply chain entities, peak bodies, industry specialists and all levels of government who are responding to the increasingly interconnected and interdependent nature of Australia’s critical infrastructure.43

2.32 In addition to the forums listed in Table 2.1, the department engages on an as needed basis with other regulators, particularly with the:

- Treasury to provide advice on the national security implications of applications made under the FATA; and

- Australian Communications and Media Authority about the issuing of carrier licences that requires approval from the Communications Access Coordinator (CAC)44 under the TSSR.

Information sharing

2.33 Effective communication arrangements ensure agencies receive information they need to undertake their functions. It also enables agencies to coordinate with, and benefit from, activities undertaken by other agencies. The SoCI Act allows the department to share information that it has obtained with relevant entities responsible for the regulation, or oversight of critical infrastructure assets.45

2.34 Regulatory and non-regulatory arrangements apply to the collection of information by the department relating to critical infrastructure. Under the SoCI Act, asset owners have an obligation to report specific information to the department’s Register of Critical Infrastructure Assets. Under the TSSR, entities that are carriers and nominated carriage service providers may advise of changes with potential security risks.46

2.35 Other Commonwealth, state and territory regulators obtain critical infrastructure asset information under their respective functions (see Appendix 4). The department does not use arrangements in Table 2.1 to obtain or share threat prevention and preparedness related information with these regulators.47 While the department informed the ANAO it shares information with states and territories, and other Australian Government regulatory bodies, the ANAO did not identify a consistent or risk-based approach. Consequently, more established information-sharing arrangements exist with some key stakeholders48 and not others.49

Recommendation no.2

2.36 The Department of Home Affairs establish an engagement strategy to document how it will coordinate with stakeholders with shared responsibility for critical infrastructure security and resilience.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.37 The department agrees to recommendation 2 of the report. As noted by the ANAO, the department produced sector-specific engagement strategies in 2021 and will do so in 2022 focused on the legislative reforms and how best to support sectors through the reforms journey. Following the passage of both tranches of the reforms, the CISC has released “Protecting Australia Together” which outlines CISC functions, mission and approach to provide an understanding to industry on the way our work will enable all facets of the critical infrastructure community to remain secure and resilient, for the benefit of all. “Protecting Australia Together” will be supported by the release of Stakeholder Communication and Engagement Strategy which documents, in a specific and tangible way, how CISC will coordinate the shared responsibility for critical infrastructure security and resilience with all 11 critical infrastructure sectors. The department agrees that there is an ongoing need to ensure clarity of responsibility and accountability for ensuring steps are taken to maintain security of Australia’s critical infrastructure. The portfolio is aligned with the requirements under the Regulator Performance Guide, which came into effect from 1 July 2021. To date, the Portfolio has been provided Ministerial Statements of Expectations for all its regulatory functions, including the CISC, and is progressing a corresponding Statements of Intents. This will demonstrate the strong commitment to meeting stakeholder expectations while delivering the Government’s policy priorities and supporting the regulatory reform agenda. An integral part of this will be clear articulation of how the Portfolio regulators will engage with industry and continue to strive for continuous improvement. Both the Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intents will be publicly available in due course. Refer also to the response to recommendation 4, as the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy will contribute towards achieving this recommendation.

Has an effective performance framework been established?

The department’s performance framework requires improvement. Critical infrastructure related content in the department’s 2020–21 performance statements is not adequate. The department did not assess its critical infrastructure functions against the Regulator Performance Framework. The department has established internal performance reporting but could improve its use of measures in the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy to inform policy development and regulation.

2.38 A key element of regulatory governance is the establishment of an appropriate performance framework that provides information about whether the regulator is achieving its intended results. This should include external performance measures to provide information about the achievement of its purpose to the Parliament and other stakeholders, and internal performance measures to inform officials about the efficiency, effectiveness, economy and ethics of their regulatory and policy approach.

Performance framework

Performance measure adequacy

2.39 Under the Commonwealth Performance Framework, an entity must report on how its performance in achieving its purposes and key activities will be measured and assessed.50 To provide accountability to the Parliament and the public, the results against these measures are required to be provided in annual performance statements.51

2.40 In 2020–21 and 2021–22, the performance measure relating to critical infrastructure contained in department’s Portfolio Budget Statements and corporate plan were broadly consistent.

- The department’s 2020–21 and 2021–22 Portfolio Budget Statements each included a single program, purpose and performance measure, with one target that relates to its critical infrastructure responsibilities.

- The department’s 2020–21 and 2021–22 corporate plans each included three purposes, with critical infrastructure responsibilities falling under purpose 1 on national security.52 The 2020–21 corporate plan also stated that ‘ownership of critical infrastructure must continue to be managed and resilience will need to be enhanced to ensure it cannot be compromised by natural hazards, organised criminals, or foreign actors’.53

- The 2020–21 and 2021–22 corporate plans each include one key activity, one composite measure and four targets that related to the department’s critical infrastructure responsibilities.

2.41 The ANAO assessed the department’s 2020–21 critical infrastructure performance measure against the requirements of the Commonwealth Performance Framework and accompanying guidance.54 The ANAO did not assess the appropriateness of the department’s entity-wide set of performance measures, and reviewed only the measure directly relating to the critical infrastructure program.

2.42 Section 16EA of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires an entity’s performance measures, in the context of the entity’s purposes or key activities, to:

- relate directly to one or more of those purposes or key activities;

- use sources of information and methodologies that are reliable and verifiable;

- provide an unbiased basis for the measurement and assessment of the entity’s performance;

- where reasonably practicable, comprise a mix of qualitative and quantitative measures;

- include measures of the entity’s outputs, efficiency and effectiveness if those things are appropriate measures of the entity’s performance; and

- provide a basis for an assessment of the entity’s performance over time.55

2.43 Table 2.2 below, details the ANAO’s assessment of the department’s performance measure.

Table 2.2: Assessment of the department’s external critical infrastructure related performance statement measure

|

Performance measure |

Relateda |

Measurableb |

|

Effective policy development, coordination and industry regulation safeguards Australia’s critical infrastructure against sabotage, espionage and coercion. |

◆ |

■ |

Key: ◆ = Fully meets the requirements of section 16EA of the PGPA Rule. ■ = Does not meet the requirements of section 16EA of the PGPA Rule.

Note a: Related refers to the requirement of subsection 16EA(a) of the PGPA Rule, as amended. In applying the related criterion, the ANAO assessed whether the entity’s performance measure relate directly to one or more of the entity’s purposes or key activities.

Note b: In applying the ‘measurable’ criterion, the ANAO assessed whether the entity’s performance measure was:

- reliable and verifiable — use sources of information and methodologies that are reliable and verifiable; and

- free from bias — provide an unbiased basis for the measurement and assessment of the entity’s performance.

Source: ANAO analysis based on Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide No.131.

2.44 The department’s critical infrastructure related performance measure is not adequate. The measure:

- relates directly to the department’s purposes56;

- is not measurable on the basis that targets are not supported by a verifiable method57 (see Table 2.3), are not free from bias, and do not include details about how performance against them contribute to achieving the purpose58; and

- has targets that relate to outputs.59

Table 2.3: Department and ANAO performance target assessments

|

Target and entity assessment |

Methodology |

ANAO summary assessment |

|

1.1.3.1: Engage with 100 per cent of entities on the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 register in relation to security and resilience. This metric was assessed as met by the department in 2020–21. |

Assessment of the proportion of entities on the SoCI Act register that the Department provides security and resilience advice through ongoing compliance activities, bilateral engagements and participation in relevant industry fora. ‘Engagement’ is defined as any form of communication with registered entities. For example phone, email, face-to-face meeting. |

An internal review noted that 42 per cent of the progress against this metric was due to an advisory email sent to entities being considered as engagement. Likewise, in 2020–21, contact with entities to request they notify the department of any changes was treated as engagement against this target. |

|

1.1.3.2: 100 per cent of notifications received under the Telecommunications Sector Security (TSS) reforms to the Telecommunications Act 1997 are responded to within statutory timeframes This metric was assessed as met by the department in 2020–21. |

Assessment of the number and percentage of notifications responded to within statutory timeframes of 30 calendar days for notifications and 60 calendar days for notification exemption requests. |

The methodology does not specify:

|

|

1.1.3.3: 100 per cent of Foreign Investment Review Board cases referred are responded to within agreed timeframes. This metric was assessed as partially met by the department in 2020–21. |

Assessment of cases referred to the Department that are responded to within timeframes agreed with Treasury. |

In 2020–21, performance against the department’s target of 100 per cent of Foreign Investment Review Board cases referred to it being responded to within agreed timeframes included counting the 60 per cent of responses when an extension to the original agreed standard response timeframe was sought by the department. |

|

1.1.3.4: Deliver an enhanced framework to protect critical infrastructure and systems of national significance. This metric was assessed as partially met by the department in 2020–21. |

Demonstrated progress in delivering legislative amendments, a new Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy and an enhanced Trusted Information Sharing Network. |

At the time of 2020–21 reporting against the target a new strategy and enhanced network had not been delivered, and legislative amendments had not been enacted. |

Source: ANAO analysis based on Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide No.131.

Regulatory performance framework self-assessment

2.45 The Regulator Performance Framework, released in October 2014, requires Australian Government regulators to publish annual self-assessments of their performance against six performance indicators. The Regulatory Performance Framework notes that ‘for a small number of regulators, issues concerning national security and operational details to achieve regulatory objectives may require published report(s) to be less detailed.’ The department advised the ANAO that it had interpreted this as meaning that the appropriate minister could decide to exempt certain regulatory functions from reporting on national security grounds.

2.46 A ministerial decision approved reporting content, and noted that some functions were excluded on national security grounds, though it did not list critical infrastructure functions as exempt. Rather, the Minister for Home Affairs was advised by the department that ‘exemptions on national security grounds would cover a range of departmental functions’. Although the exemption was only for public reporting of assessments against the framework, the department did not complete any self-assessment of its critical infrastructure related regulatory responsibilities for internal use.

2.47 In July 2021, the Regulator Performance Guide superseded the 2014 Framework. In October 2021, the department advised the ANAO that ‘from 2020–21 it will report directly against the Regulator Performance Framework’. The 2020–2160 report for the department did not refer to critical infrastructure related regulatory functions. Annual reporting on the use of powers under the SoCI Act and TSSR does not include performance measurement information.

Legislative reform

2.48 Reform of critical infrastructure related legislation has provided the department with an opportunity to review its performance internally and through external processes. These reforms have allowed the department to review its performance by drawing on external feedback sources in the form of parliamentary activity and stakeholder consultations. Reforms to the SoCI Act in 2021 were developed after consultation processes that are summarised in Appendix 3. The department used content from submissions by its stakeholders to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS)61, and its own consultations to analyse the policy issues associated with the proposed legislative reforms. Submissions to the PJCIS by the department referred to a number of changes made to the Bill following receipt of stakeholder feedback ‘to ensure that the Bill appropriately meets the needs of both Government and owners and operators of critical infrastructure’.62

2.49 In its advisory report on the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure) Bill 2020 and statutory review of the SoCI Act 2018, the PJCIS recognised these processes and their intent, as well as negative feedback on the lack of action or acknowledgement of input submitted as part of consultations, or sufficient promotion of the opportunity to engage the department on the reforms.63 Notwithstanding a diversity of views on whether engagement provided genuine opportunity to influence legislative reforms, the department provided policy advice to the government on regulatory changes after undertaking consultative processes.

Internal performance information

2.50 Internal monitoring of performance using well-defined measures can be a valuable source of information for a regulator on the effectiveness of its strategies and areas for improvement. The department has established reporting to internal governance bodies on the performance against its business plan and the implementation of government objectives. Measures are well defined and provide updates on the extent to which activities have been implemented or further action is required.

2.51 Performance measures are also included in the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy plan. An internal assessment of progress against activities in the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy did not provide assurance of the progress made, had few references to outputs delivered by activities, and did not assess progress against outcomes.

Recommendation no.3

2.52 The Department of Home Affairs ensure performance measurement:

- in its corporate plan is adequate and measurable;

- aligns with the Regulator Performance Guide; and

- is used to inform policy and regulatory improvements.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.53 The department agrees to recommendation 3 of the report and acknowledges the areas for improvement identified within its 2020–21 Performance Framework, specifically as they relate to Critical Infrastructure activities. As an immediate initiative, CISC has amended its critical infrastructure performance metrics for 2022–23 to align with the improvements identified by the ANAO. The department continues to mature its framework and performance reporting process to align to best practice principles and welcomes the commentary that its internal measures are well defined and provide updates on the extent to which activities have been implemented. The department notes that recommendation (3b), regarding alignment to the May 2021 Regulator Performance Guide, did not apply to the financial years assessed as part of the Audit. In addition, the Department notes it is not required to measure regulator performance through the Corporate Plan and Annual Report (under the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) until the 2022–23 financial year.

3. Compliance activities

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Home Affairs effectively administered its compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements.

Conclusion

The department’s administration of compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements is partly effective. The department’s compliance framework does not reflect existing responsibilities or compliance requirements. Compliance activities are not supported by approved procedures or systems controls. The department has not established a risk-based decision framework for achieving compliance outcomes or demonstrating its impact on asset security or resilience. The department does not have a process of effectively reviewing its use of regulatory tools, impact on industry or to inform continuous improvement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at improving the department’s existing framework to manage compliance, support and review the effective use of all available regulatory tools.

3.1 Effective critical infrastructure regulation is important because a disruption ‘could have serious implications for business, governments and the community, impacting supply security and service continuity’.64 To assess whether the Department of Home Affairs (the department) effectively administered compliance activities consistent with critical infrastructure protection requirements, the ANAO examined: the department’s compliance framework; compliance procedures; and compliance activities.

Has an effective framework been established to manage compliance with critical infrastructure requirements?

The department has established a compliance framework comprised of the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy, Compliance Strategy and Administrative Guidelines. This framework would be enhanced by updating documents in the framework to align with, and clarify, the department’s existing responsibilities and regulatory posture.

3.2 A compliance framework is a set of plans, policies, or procedures that set the approach taken to manage compliance. Establishing and implementing appropriate plans supports regulators to achieve desired regulatory outcomes. The framework for the department’s compliance approach is summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Summary of critical infrastructure compliance framework

|

Document |

Summary of compliance issues covered |

|

Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy |

Includes a plan and a policy statement. The policy statement states the ‘Australian Government takes a non-regulatory approach to critical infrastructure resilience, favouring a productive business-government partnership’a |

|

Critical Infrastructure Centre Compliance Strategy |

Outlines the department’s approach to compliance under both the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SoCI Act) and Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms (TSSR). It states that the Centre’s ‘vision for Australia’s critical infrastructure is one of voluntary compliance by owners and operators, with the Centre as an industry resource, whereby industry and government work cooperatively to jointly manage security risks.’b |

|

TSSR Administrative Guidelines |

Designed to help entities covered under the TSSR to understand and comply with requirements. The Administrative Guidelines state that ‘enforcement mechanisms are intended as a last resort to address non-cooperative conduct rather than to penalise action and decisions taken in good faith’c |

Note a: Australian Government, Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy: Policy Statement [Internet], Department of Home Affairs, 2015, available from https://www.cisc.gov.au/help-and-support-subsite/Files/critical_infrastructure_resilience_strategy_policy_statement.pdf [accessed 5 January 2022].

Note b: Australian Government, Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy: Plan [Internet], Department of Home Affairs, 2015, available from https://www.cisc.gov.au/help-and-support-subsite/Files/critical_infrastructure_resilience_strategy_plan.pdf [accessed 5 January 2022].

Note c: Department of Home Affairs, Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms (TSSR) Administrative Guidelines [Internet], Department of Home Affairs, 2015, available from www.cisc.gov.au/help-and-support-subsite/Files/tss_administrative_guidelines.pdf [accessed on 5 January 2022].

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.3 The department’s compliance framework outlined in Table 3.1 does not reflect its current compliance requirements. The Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy, which guides the work of the Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre, has not been updated since 2015, despite including a review point in 2020, and plans by the department to update it since at least 2019. Consequently, the Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy does not:

- reflect machinery of government changes in 2017 that moved responsibility for critical infrastructure protection coordination to the department;

- delineate the department’s policy and regulatory responsibilities from those of other Commonwealth, state and territory regulatory bodies, or set out how these responsibilities will be applied; or

- align with current powers to regulate critical infrastructure, or the increased scale and sophistication of threats that have been used as the basis for legislative changes but not reflected in the compliance framework.

3.4 Figure 3.1 illustrates the compliance model included in the compliance strategy, with the following tools listed under each of the four tiers in the model.