Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Regulation of Charities by the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- To determine whether the Commonwealth’s charity regulator, the ACNC, is regulating registered charities effectively.

- The public, business and governments provide significant funding and other support to charities to help them deliver their charitable purposes.

Key facts

- The ACNC has registered over 17,000 charities since it was established in December 2012.

- Registration with the ACNC is necessary to gain access to certain Commonwealth tax concessions.

- The Charities Act 2013 sets out the legal definition of a charity.

- The online Charity Register provides details on registered charities.

- The ACNC’s formal enforcement powers do not automatically apply to all registered charities.

What did we find?

- The ACNC has been largely effective in delivering its regulatory responsibilities for registered charities.

- The ACNC has focussed on providing education and guidance to support charities’ ongoing compliance obligations.

- The ACNC has taken a ‘light touch’ approach to assessing whether charities meet required governance standards.

- The ACNC has made relatively limited use of its stronger regulatory powers to address identified non-compliance.

- The ACNC has established a number of initiatives to reduce the red tape burden on registered charities.

What did we recommend?

- We made four recommendations and suggested other areas for improvement.

- The ACNC agreed to implement all four recommendations.

57,600

charities were registered with the ACNC as of 3 February 2020.

77

charities have had their registration revoked as a result of the ACNC’s compliance activities (up to 30 June 2019).

$142.7 billion

was the total revenue reported by registered charities in 2017.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) is the principal regulator of charities at the Commonwealth level.1 The ACNC was established in December 2012 under the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Act 2012 (ACNC Act). Its establishment followed a series of reviews and inquiries into the not-for-profit (NFP) sector since the mid-1990s.

2. The benefits expected from establishing a national regulator and reforming the regulatory framework for the NFP sector are reflected in the three objects of the ACNC Act, which are to:

- maintain, protect and enhance public trust and confidence in the Australian NFP sector;

- support and sustain a robust, vibrant, independent and innovative Australian NFP sector; and

- promote the reduction of unnecessary regulatory obligations on the Australian NFP sector.

3. The ACNC Act provides for the ACNC to regulate registered charities only (some 57,600 as of 3 February 2020), not the wider NFP sector.

4. The ACNC’s regulatory activities include: registering charities; maintaining a public register of charities; providing advice and assistance to charities; undertaking monitoring, compliance and enforcement activities; and working with Commonwealth entities and other jurisdictions to reduce the regulatory burden on charities.

5. The ACNC Commissioner is responsible for administering the ACNC Act, and is supported by staff made available by the Commissioner of Taxation (who is the accountable authority of the ACNC). The ACNC is funded from the ATO’s departmental appropriations, and had a budget of $16.2 million in 2018–19. As at 30 June 2019, the ACNC had 95 full-time equivalent staff.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. In Australia, governments, business and the public provide significant funding and other support to charities to help them deliver their charitable purposes. This audit was undertaken to provide assurance on whether the ACNC is regulating registered charities effectively, including for the benefit of recipients, donors and the wider community.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the ACNC’s regulation of charities. The three high-level criteria were:

- Has the ACNC been effective in registering charities and maintaining the Charity Register?

- Has the ACNC been effective in supporting charities to meet their ongoing compliance obligations?

- Has the ACNC been effective in strengthening the sector and reducing the regulatory burden on charities?

Conclusion

8. The ACNC has been largely effective in delivering its regulatory responsibilities for registered charities.

9. The ACNC has been largely effective in registering charities and partially effective in maintaining the Charity Register. The ACNC has processed applications in a timely manner, but should better document assessment processes under its ‘light touch’ approach to registration. The ACNC has commenced a project to improve the usefulness of the information on the Charity Register, and should conduct additional checks on the integrity of that information.

10. The ACNC has been largely effective in supporting charities to meet their ongoing compliance obligations, particularly by providing guidance and monitoring charities’ compliance. It has been less effective in addressing non-compliance. Improvements to the ACNC’s compliance processes and measurement of outcomes would better support the objective of maintaining, protecting and enhancing public trust and confidence in the charities sector.

11. Within its remit and authority, the ACNC has been largely effective in promoting the reduction of unnecessary regulatory obligations on registered charities, but was less able to demonstrate its effectiveness in supporting and sustaining a robust, vibrant, independent and innovative not-for-profit sector.

Supporting findings

Registering charities and maintaining the Charity Register

12. The ACNC’s registration processes have been designed on the basis of largely negative assurance — that is, to rely on information and assertions provided by an applicant of compliance with registration requirements, including the five Governance Standards, unless there is evidence to the contrary. The ACNC supports this approach by making a range of guidance material available to potential applicants. Some of the procedural checks that the ACNC requires on applicants’ information and assertions were not well-documented. The ACNC should verify whether its ‘light touch’ approach to registration is appropriate.

13. The ACNC processed the vast majority of registration applications received in 2017–18 and 2018–19 well within its published service standard of 15 business days. Applications that took longer than 15 business days were not characterised by any particular complexity.

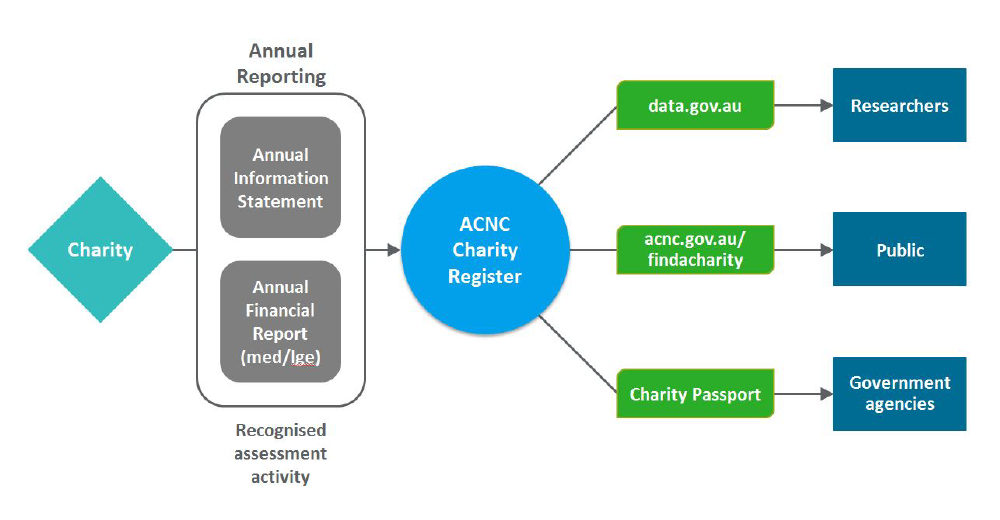

14. The ACNC has been partially effective in maintaining the Charity Register. While business-as-usual processes are in place to maintain important aspects of the Register, the ACNC has identified a number of outstanding data integrity and quality assurance issues that impact on the reliability and completeness of some information. A project to make the Register a more valuable resource for users is also underway — known as the ‘Charity Marketplace’.

Supporting ongoing compliance by charities

15. Consistent with the main focus of its Regulatory Approach Statement, the ACNC has been largely effective in assisting charities to understand and meet their ongoing compliance obligations. The ACNC has well-established arrangements for providing guidance and support to charities. It also has regular processes for prompting and encouraging charity compliance, although in 2018–19 the number of registered charities that lodged their Annual Information Statement on time (70 per cent) fell short of the ACNC’s performance target (75 per cent).

16. The ACNC has been largely effective in monitoring charities’ compliance in accordance with its stated regulatory approach, but less effective in undertaking risk-based compliance and enforcement activities. The ACNC relies mainly on external parties to identify compliance concerns, and is improving its arrangements for allocating available resources to identified compliance priorities. Complexity in determining whether charities are ‘federally regulated entities’ has limited the ACNC’s use of enforcement powers and reporting of enforcement results for deterrence purposes.

17. Current performance information does not provide a clear indication on whether the ACNC has been effective in maintaining, protecting and enhancing public trust and confidence in the charities sector. The ACNC has discontinued its most direct means of measuring public trust and confidence — a biennial survey.

Strengthening the sector and reducing the regulatory burden on charities

18. In late 2018, the ACNC initiated a project to interpret the intent of the second object of the ACNC Act. The ACNC has undertaken a number of activities focussed on promoting good governance practices and providing data to the sector, which may have assisted in supporting and sustaining a robust, vibrant, independent and innovative sector.

19. The ACNC has been active in promoting the reduction of unnecessary regulatory obligations on the charities sector. A number of specific initiatives have been introduced, especially to harmonise or streamline charities’ reporting arrangements — including through a data exchange tool called the ‘Charity Passport’. Further and ongoing benefits to charities requires the participation of other Commonwealth entities and jurisdictions.

20. The ACNC has not produced complete and relevant performance information to indicate the extent to which it has been effective in supporting and sustaining a robust, vibrant, independent and innovative not-for-profit sector. Performance information on the objective of promoting the reduction of unnecessary regulatory obligations on charities is more relevant and complete — and is largely positive.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.30

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission strengthens its processes for assessing applications for charity registration by:

- Ensuring that the application form seeks appropriate information on which to assess compliance with legislative requirements.

- Revising its risk management framework for registration applications to identify whether additional documentation or evidence should be sought from applicants on a risk basis.

- Ensuring that all required procedural checks are clearly documented and able to be evidenced in its case management system or records.

- Amending its main decision-making form to make explicit reference to whether all legislative requirements for registration have been met.

- Verifying whether its ‘light touch’ approach to registration is appropriate.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office response: Noted.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.58

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission investigates feasible and cost-effective approaches to improving the integrity of the information on the Charity Register, including, as appropriate, automating as many of the outstanding data integrity tasks as possible through its existing processes and systems.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office response: Noted.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.56

To better support the objective of maintaining public trust and confidence in the charities sector, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission enhances its compliance framework and operational practices by:

- Using its processes for monitoring the annual information provided by charities to support its assessment that charities are complying with the Governance Standards.

- Adopting a more proactive approach to identifying charity compliance risk, including drawing more extensively on data collected annually from charities.

- Better aligning available resources to identified risks, such that higher risk cases are investigated or otherwise resolved in a timely way.

- Ensuring that available regulatory powers are used to address identified non-compliance, including by determining more consistently whether the enforcement powers apply in relevant cases.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office response: Noted.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 3.75

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission amends its current set of performance indicators relating to the first object of the ACNC Act, with a focus on more directly measuring the impact of its regulatory activities on levels of public trust and confidence in the charities sector.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office response: Noted.

Summary of entity responses

21. The ACNC’s and ATO’s summary responses are provided below, while their full responses are reproduced at Appendix 1.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission

The ACNC welcomes the audit report, which identifies that the ACNC is largely effective in delivering its regulatory responsibilities for registered charities. To a significant extent, this reflects our own assessment of areas that require improvement and, in many instances, are already underway.

It is timely that seven years after the establishment of the ACNC, we review our approach to regulation to verify whether it remains fit-for-purpose. The audit recommendations will assist the ACNC to focus this work and ensure our settings with regards to risk, entitlement to ongoing charity registration, data management, and unnecessary regulatory burden are appropriate. They will also assist us in ensuring that resources are allocated to their best effect to deliver effective and efficient regulation that demonstrably supports public trust and confidence in the charities sector.

The ACNC agrees with the four recommendations contained in the report. We will undertake to complete a review and address the recommendations during 2020–2021 with a view to complete implementation of the recommendations in 2021–22.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO welcomes this review and considers the report supportive of our overall approach to providing the government and the community with assurance that charities are operating for purpose and correctly accessing Commonwealth tax concessions.

The review recognises the important role the ACNC has in registering and regulating charities. The report makes recommendations for a robust registration process and an enhanced compliance framework that monitors adherence to governance standards and identifies risk. In addition, the report recommends investigating approaches to improving the integrity of data on the charity register. These processes provide the ATO with greater assurance that charities are correctly accessing concessions and operating for purpose.

The ATO notes the four recommendations contained in the report.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission

1.1 The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) is the principal regulator of charities at the Commonwealth level.

1.2 The ACNC was established in December 2012 under the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Act 2012 (ACNC Act). Its establishment followed a series of reviews and inquiries into the not-for-profit (NFP) sector since the mid-1990s.2 The explanatory material for the proposed legislation stated that:

A consistent theme that emerged from these reviews is that the regulation of the NFP sector would be significantly improved by establishing a national regulator and harmonising and simplifying regulatory and taxation arrangements.3

1.3 The benefits expected from establishing a national regulator and reforming the regulatory framework for the NFP sector are reflected in the three objects of the ACNC Act (Box 1). These objects also represent the ACNC’s corporate priorities.

|

Box 1: Objects of the ACNC Act |

|

Source: ANAO, based on subsection 15-5(1) of the ACNC Act.

1.4 The ACNC Act provides for the ACNC to regulate registered charities only, not the wider NFP sector.

1.5 Prior to the ACNC being established, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) was the de facto regulator of charities in the Commonwealth and continues to retain some regulatory responsibilities.4

ACNC’s governance arrangements

1.6 The ACNC Commissioner is an independent statutory office holder appointed to administer the ACNC Act. The staff assisting the ACNC Commissioner are made available by the Commissioner of Taxation. For the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and related instruments, the Commissioner of Taxation is the accountable authority of the ACNC.5

1.7 The function of the ACNC Advisory Board6 is, at the request of the ACNC Commissioner, to provide advice and make recommendations in relation to the Commissioner’s functions. Advisory Board members are appointed by the responsible minister — currently the Assistant Minister for Finance, Charities and Electoral Matters.

Regulatory activities

1.8 Regulatory activities undertaken by the ACNC include:

- registering new charities and revoking a charity’s registration, either as a result of ACNC compliance and enforcement action or in response to a charity’s request;

- maintaining a public register of charities7, which includes financial and other information collected from charities;

- providing advice and assistance to charities and the general public, including through guidance material on its website, a contact centre and other channels such as social media;

- monitoring charities for compliance with their obligations under the ACNC Act and undertaking compliance and enforcement activities; and

- working with Commonwealth entities and other jurisdictions to reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens on charities.

1.9 The ACNC has set out its intended regulatory approach in a published Regulatory Approach Statement.8

Resourcing

1.10 As of 30 June 2019, the ACNC had 95 full-time equivalent staff, the largest number being in its Registration team (22 staff), followed by the Compliance team (16 staff) and the Advice Services team (14 staff). The remaining staff work in: Information Technology (11 staff); Reporting and Red Tape Reduction (six staff); the Executive (six staff); Education and Public Affairs (six staff); Deductible Gift Recipient Reform (five staff); Corporate Services (five staff); and Legal and Policy (four staff).

1.11 The ACNC is funded from the ATO’s departmental appropriations. In 2018–19 the ACNC’s budget was $16.2 million. Funding received by the ACNC is administered in a Special Account.9

Registered charities

1.12 As of 3 February 2020, there were 57,600 registered charities. All registered charities are required to be NFP entities, but the vast majority of NFP entities — estimated to be some 600,000 organisations — are not registered charities.10

1.13 Each year the ACNC publishes an Australian Charities Report, providing information on the activities and attributes of registered charities.11 Selected facts and figures from the most recent report (2017) are provided in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Facts and figures on registered charities (2017)

Notes: The ACNC’s 2017 Annual Charities Report, and associated data cube, is based on data reported by registered charities that submitted a 2017 Annual Information Statement.

The ACNC categorises charity size on the basis of total annual revenue. Extra small is revenue under $50,000; Small is revenue of $50,000 or more but less than $250,000; Medium is revenue of $250,000 or more but under $1 million; Large is revenue of $1 million or more but less than $10 million; Very large is revenue of $10 million or more but less than $100 million; and Extra large is revenue of $100 million or more.

Source: ANAO, based on the Australian Charities Report 2017 data cube, available at: https://www.acnc.gov.au/charitydata [accessed 15 August 2019].

1.14 The charities registered with the ACNC include long-established and well-known organisations as well as many small organisations with limited profiles.

1.15 The legal definition of ‘charity’ and ‘charitable purpose’ is set out in the Charities Act 2013 (Charities Act) for the purposes of all Commonwealth legislation (Box 2). Prior to the introduction of the Charities Act on 1 January 2014, the legal meaning of a charity was based largely on over 400 years of common law.

|

Box 2: Legal definition of ‘charity’ and ‘charitable purpose’ |

|

Charity means an entity:

Charitable purpose means any of the following:

|

Note a: Disqualifying purposes refers to the purpose of engaging in, or promoting, activities that are unlawful or contrary to public policy; or the purpose of promoting or opposing a political party or a candidate for political office.

Source: ANAO, based on sections 5 and 12 of the Charities Act.

1.16 In addition to the 12 charitable purposes listed in the Charities Act, the ACNC Act includes two other charity categories12 — a ‘Health Promotion Charity’ and a ‘Public Benevolent Institution’.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 In Australia, governments, business and the public provide significant funding and other support to charities to help them deliver their charitable purposes. This audit was undertaken to provide assurance on whether the ACNC is regulating registered charities effectively, including for the benefit of recipients, donors and the wider community.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the ACNC’s regulation of charities.

1.19 In assessing this objective, the following three high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the ACNC been effective in registering charities and maintaining the Charity Register?

- Has the ACNC been effective in supporting charities to meet their ongoing compliance obligations?

- Has the ACNC been effective in strengthening the sector and reducing the regulatory burden on charities?

1.20 The scope of the audit was limited to the regulatory activities of the ACNC in respect to registered charities. The audit did not include an examination of the ATO’s processes for determining and granting Commonwealth tax concessions for registered charities.

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit included the following methods for gathering and assessing sufficient and appropriate audit evidence:

- review and analysis of documentation held by the ACNC;

- analysis of data from the ACNC’s case management system and on the Charity Register;

- interviews with ACNC staff and the ACNC Commissioner; and

- discussions with representatives from interested parties and with the ACNC Advisory Board.

1.22 In addition, submissions were received from members of the public via the ANAO’s website.

1.23 The audit also had regard to the 2018 external review of the ACNC’s legislation.13 A number of the findings and recommendations in the review panel’s report relate to aspects of the ACNC’s operations examined during this performance audit. The Government provided a response to the review on 6 March 2020.14

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $430,000.

1.25 The team members for this audit were Amanda Reynolds and Andrew Morris.

2. Registering charities and maintaining the Charity Register

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission’s (ACNC’s) arrangements for registering charities, including timeliness, and for maintaining the Charity Register.

Conclusion

The ACNC has been largely effective in registering charities and partially effective in maintaining the Charity Register. The ACNC has processed applications in a timely manner, but should better document assessment processes under its ‘light touch’ approach to registration. The ACNC has commenced a project to improve the usefulness of the information on the Charity Register, and should conduct additional checks on the integrity of that information.

Areas for improvement

This chapter makes two recommendations directed at the ACNC, to strengthen its processes for assessing applications for charity registration (paragraph 2.30), and to improve the integrity of information on the Charity Register (paragraph 2.58). The chapter also suggests that the ACNC conducts an evaluation of the ‘Charity Marketplace’ initiative (paragraph 2.67).

2.1 Under the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission Act 2012 (ACNC Act), the ACNC Commissioner’s responsibilities include registering charities and maintaining a public register, known as the Charity Register.

2.2 To determine whether the ACNC has been effective in meeting these responsibilities, this chapter examines whether:

- the ACNC’s registration processes provide assurance that successful applicants have met specified legislative requirements;

- the ACNC has met its published service standard relating to the timeliness of processing applications for registration; and

- the ACNC has implemented arrangements to maintain the integrity of the information on the Charity Register.

Do the ACNC’s registration processes provide assurance that registered charities meet legislative requirements, including the Governance Standards?

The ACNC’s registration processes have been designed on the basis of largely negative assurance — that is, to rely on information and assertions provided by an applicant of compliance with registration requirements, including the five Governance Standards, unless there is evidence to the contrary. The ACNC supports this approach by making a range of guidance material available to potential applicants. Some of the procedural checks that the ACNC requires on applicants’ information and assertions were not well-documented. The ACNC should verify whether its ‘light touch’ approach to registration is appropriate.

2.3 Registration with the ACNC is a prerequisite for accessing certain Commonwealth tax concessions15 — eligibility for which is determined by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) — but is otherwise voluntary.16 Registration also signals to the public that charities have been independently assessed as meeting relevant eligibility requirements and standards of governance.

2.4 In the past five years, the ACNC has typically received between 200–350 applications for charity registration per month, with a fairly consistent pattern across the years (Figure 2.1).17

Figure 2.1: Applications for charity registration, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s data.

2.5 As well as registering charities, the ACNC refuses some charity registrations — for instance, 230 applications for registration were refused in 2018–19; and a sizable number of applicants also withdraw their applications — 1338 in 2018–19.

2.6 The legislative requirements for registration are set out in the ACNC Act and the Charities Act 2013 (Charities Act). The ACNC Act includes conditions of registration that an applicant:

- is a not-for-profit entity;18

- is in compliance with the Governance Standards and External Conduct Standards19;

- has an Australian Business Number (ABN); and

- is not covered by a decision in writing made by an Australian government agency (including a judicial officer) under an Australian law that provides for entities to be characterised on the basis of them engaging in, or supporting, terrorist or other criminal activities.

2.7 The Charities Act specifies the elements that must be satisfied in order to meet the legal definition of a charity (Box 2 in Chapter 1).

2.8 The ACNC seeks to address these legislative requirements over the four stages of its registration process — initial review, risk assessment, analysis and decision.

Assessing compliance with the Governance Standards

2.9 The Governance Standards (Box 3)20 were introduced to provide the public with confidence that registered entities: manage their affairs openly, accountably and transparently; use their resources, including contributions and donations, effectively and efficiently; minimise the risk of mismanagement and misappropriation; and pursue their purposes.

|

Box 3: Outline of the Governance Standards |

|

Standard 1: Purposes and not-for-profit nature Charities must be not-for-profit and work towards their charitable purpose. They must be able to demonstrate this and provide information about their purposes to the public. Standard 2: Accountability to members Charities that have members must take reasonable steps to be accountable to their members and provide them with adequate opportunity to raise concerns about how the charity is governed. Standard 3: Compliance with Australian laws Charities must not commit a serious offence (such as fraud) under any Australian law or breach a law that may result in a penalty of 60 penalty units (equivalent to $12,600 as at December 2018) or more. Standard 4: Suitability of Responsible Personsa Charities must take reasonable steps to: be satisfied that its Responsible Persons (such as board or committee members or trustees) are not disqualified from managing a corporation under the Corporations Act 2001 or disqualified from being a Responsible Person of a registered charity by the ACNC Commissioner; and remove any Responsible Person who does not meet these requirements. Standard 5: Duties of Responsible Persons Charities must take reasonable steps to make sure that Responsible Persons are subject to, understand, and carry out the duties set out under this Standard, which are to: act with reasonable care and diligence; act honestly in the best interests of the charity and for its purposes; not misuse the position of Responsible Person; not misuse information obtained in performing duties; disclose any actual or perceived conflict of interest; ensure that the charity’s financial affairs are managed responsibly; and not allow a charity to operate while insolvent. |

Note: Further details on the Governance Standards are provided in ACNC Regulation 2013, available at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2019C00634 [accessed 17 September 2019].

Note a: The ACNC Act and ACNC Regulation 2013 refer to ‘Responsible Entities’.

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s webpage, available at: https://www.acnc.gov.au/for-charities/manage-your-charity/governance-hub/governance-standards [accessed 17 September 2019].

2.10 The ACNC relies to a large extent on information and assertions provided by applicants to determine whether the Governance Standards are met. Its regulatory approach is set out in an internal ‘work instruction’ on new registrations, which states that:

When considering applications for registration and compliance with the Governance Standards, our approach mirrors our regulatory approach. This means that unless there is evidence to the contrary or information that the applicant is at greater risk of not adhering to the Governance Standards, we generally rely on the information that the applicant provides in response to governance questions in the Registration application to determine that there is no evidence that the applicant is not complying with the Governance Standards.

2.11 This approach can be characterised as a negative rather than positive form of assurance.21

2.12 In February 2016, the ACNC considered other options for addressing the Governance Standards, including requiring ACNC registration staff to query compliance with the applicant during the registration process. The ACNC considered that this option was not practical as it would substantially slow down the processing of applications and transfer the onus of assessing compliance from the charity to the ACNC. Further, the ACNC considered that the ‘proper enquiry’ of charity compliance would be extensive and the outcomes subjective, based on the type of charity. In the end, the ACNC Commissioner favoured what was described as a ‘light touch’ approach, which puts the responsibility on applicants to self-assess compliance and encourages applicants to seek further information from the ACNC’s website.

2.13 The ACNC’s website provides a range of guidance material for the benefit of potential applicants. This includes: a step-by-step guide to eligibility; a registration application checklist; and various policy statements by the ACNC Commissioner, including on how the ACNC interprets the law on eligibility for registration. As well, the website advises that: ‘Charities do not need to submit anything to the ACNC to show they meet the [Governance] Standards, but must have evidence of meeting the Standards that they can provide if requested.’22

2.14 The ACNC advised that the approach described in its internal work instruction is underpinned by three principles:

- the requirement on applicants to declare that they comply with all of the Governance Standards from either the date of requested registration or the date the Standards came into effect on 1 July 2013 (whichever is later);23

- the requirement on applicants to declare that the information provided in the registration application form is true, correct, and complete — having been advised that giving false and misleading information is a serious offence; and

- alignment with the ACNC’s Regulatory Approach Statement, and the underlying principles from the ACNC Act of: regulatory necessity; reflecting risk; and proportionate regulation.24

2.15 The ACNC also advised the specific checks required to be undertaken during the registration process against each of the five Governance Standards (which are listed in Table 2.1). These checks were not set out as comprehensively in the ACNC’s existing policies and procedures.25

Checks undertaken by the ACNC

2.16 As outlined in Table 2.1, analysis of the ACNC’s registration processes and testing on a selection of 20 successful registration applications from 2018–19 showed that the ACNC largely followed the regulatory approach described above — that is, the ACNC relied mainly on the information and assertions provided by applicants.

2.17 A key focus of the ACNC’s assessment was to ensure that an applicant’s ‘governing document’26 contained appropriate content to satisfy various requirements in the ACNC Act and Charities Act, including that the entity will operate on a ‘not-for-profit’ basis and will pursue charitable purposes.

2.18 Some of the checks that the ACNC advised it undertakes on new registrations were not able to be clearly evidenced in its case management system or records, especially in relation to Governance Standard 2 (Accountability to members). For instance, the ACNC recorded no evidence that an applicant’s governing document included sufficient provisions to support accountability to members.

2.19 The ACNC’s main decision-making document for the registration process (called the ‘Reason for Decision’ form) did not include any reference to whether the Governance Standards had been met. A general statement is included on the ACNC’s case management system at the decision stage of the registration process that ‘Governance standards appear satisfied’.

2.20 The ACNC has developed a risk assessment framework for registration applications (using a risk rating scale of 1–6), which identifies if an application requires technical sign off by a more senior ACNC staff member.27 The risk assessment process does not explicitly require additional documentation or evidence to be obtained from those applications requiring technical sign off.

Table 2.1: ACNC’s approach to assessing compliance with the Governance Standards

|

Governance Standard |

ACNC’s approach to assessing compliance with the Governance Standards |

|

Standard 1: Purposes and not-for-profit nature |

|

|

Standard 2: Accountability to members |

|

|

Standard 3: Compliance with Australian laws |

|

|

Standard 4: Suitability of Responsible Persons |

|

|

Standard 5: Duties of Responsible Persons |

|

Note a: A ‘not-for-profit’ clause, which restricts private profit or gain, as well as a ‘dissolution’ or ‘winding up’ clause to indicate how the assets and income of the charity will be distributed if the entity is dissolved.

Note b: The report on the 2018 external review of ACNC’s legislation recommended that Governance Standard 3 be repealed. The Government did not support this recommendation.

Note c: Basic Religious Charities are not required to comply with the Governance Standards.

Source: ANAO, based on analysis of the ACNC’s processes and examination of a selection of 20 successful registration applications from 2018–19.

Managing risks

2.21 Having regard to a risk managed approach, it is important for the ACNC to verify, over time, whether its ‘light touch’ approach to registration is appropriate. Relevant considerations include whether the ACNC:

- receives sufficient feedback from its subsequent regulatory activities to determine whether the approach taken during the registration process reduces the residual risk to an acceptable level; and

- has sufficient capacity and skills to identify and manage any risk of non-compliance that is not addressed through the registration process.

2.22 Since compliance with the five Governance Standards is a condition of registration, and registration is a prerequisite for accessing certain Commonwealth tax concessions, it is recommended that the ACNC strengthens aspects of its processes for assessing applications for charity registration (Recommendation no.1, paragraph 2.30).

2.23 The ACNC should also ensure that any improvements in its approach to assessing and evidencing compliance with the Governance Standards are reflected, as appropriate, in its approach to assessing and evidencing compliance with the External Conduct Standards.

Assessing compliance with the Charity Act requirements

2.24 As outlined in Table 2.2, the ACNC’s approach to determining whether applicants meet the legal definition of a charity is similar to its approach in assessing compliance with the Governance Standards. The ACNC relies mainly on the information provided by applicants in their application form and governing document, seeking more information where required. As well, the ACNC undertakes legal analysis and uses legal precedents to assess and support compliance with elements of the Charity Act requirements.

2.25 As with the Governance Standards, some of the procedural checks that the ACNC required to be undertaken to assess whether applicants meet the legal definition of a charity were not clearly evidenced in its case management system or records.

Table 2.2: Assessing the legal definition of a charity

|

Charity Act requirement |

ACNC’s approach to assessing compliance |

|

The entity is a not-for-profit entity |

|

|

All of the entity’s purposes are:

|

|

|

None of the entity’s purposes are disqualifying purposesb |

|

|

The entity is not an individual, a political party or a government entity |

|

Note a: The ACNC uses a rating scale of 1–6. Applications rated 4–6 cover a range of risk factors including whether the charity has vulnerable beneficiaries, operates overseas, or has applied for particular charity subtypes.

Note b: Disqualifying purposes refers to the purpose of engaging in, or promoting, activities that are unlawful or contrary to public policy; or the purpose of promoting or opposing a political party or a candidate for political office.

Note c: The ACNC’s website notes that the Interpretation Statement is highly technical, as the law is very complex in this area.

Source: ANAO, based on analysis of the ACNC’s processes and examination of a selection of 20 successful registration applications from 2018–19.

Other registration requirements

2.26 The ACNC addresses the legislative condition for registered charities to have an ABN by requiring applicants to provide their ABN on the registration application form. All 20 registration cases examined included an ABN.

2.27 Based on the registration cases examined, there was limited evidence of how the ACNC addressed the legislative condition that an applicant is not covered by a decision in writing made by an Australian government agency (including a judicial officer) under an Australian law that provides for entities to be characterised on the basis of them engaging in, or supporting, terrorist or other criminal activities. The ACNC’s Reason for Decision form included a ‘Yes/No’ statement to answer this question; in all of the 20 registration cases examined the recorded answer was ‘No’. No evidence was identified on the ACNC’s case management system to demonstrate what checks were undertaken to support this statement.

2.28 The ACNC advised that it assesses this legislative condition by checking various Australian Government databases, including checking the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s database referred to above (see Table 2.1). The ACNC further advised that if an issue is identified through these checks, or subsequently, the relevant details would be recorded on its case management system. If no issue is identified, no specific information is recorded.28

2.29 From the registration cases examined, evidence was not consistently found that registration staff had complied with the procedural requirement to declare that they had no conflict of interest before taking on a registration case. The ACNC’s case management system defaults the conflict of interest question to ‘No’. In two cases, a note was entered on the case management system to indicate that the ACNC staff member had actively considered this question.

Recommendation no.1

2.30 The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission strengthens its processes for assessing applications for charity registration by:

- Ensuring that the application form seeks appropriate information on which to assess compliance with legislative requirements.

- Revising its risk management framework for registration applications to identify whether additional documentation or evidence should be sought from applicants on a risk basis.

- Ensuring that all required procedural checks are clearly documented and able to be evidenced in its case management system or records.

- Amending its main decision-making form to make explicit reference to whether all legislative requirements for registration have been met.

- Verifying whether its ‘light touch’ approach to registration is appropriate.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission response: Agreed.

2.31 The ACNC is committed to ensuring that its process for assessing applications for charity registration are appropriate and evidenced and that they balance risk, unnecessary regulatory burden and resources within the legislative framework.

Australian Taxation Office response: Noted.

2.32 A robust registration process provides the ATO with a greater level of certainty that newly registered charities are operating for purpose and meeting their obligations with respect to special conditions.

2.33 Charities applying for endorsement for tax concessions are required to meet special conditions for income tax exemption.

Has the ACNC processed registration applications in a timely manner?

The ACNC processed the vast majority of registration applications received in 2017–18 and 2018–19 well within its published service standard of 15 business days. Applications that took longer than 15 business days were not characterised by any particular complexity.

2.34 The timeframe in which the ACNC seeks to process applications for registration is set out in its published service standards.29

2.35 The ACNC’s current service standard for registering a charity is to finalise 90 per cent of applications within 15 business days providing the ACNC has received all the necessary information to progress the application.

2.36 The 15-day timeframe has been in place since December 2012, and originated from a joint commitment between the ACNC and the ATO to determine charitable status and tax concessions within 28 days. The ACNC advised that the timeframe reflects its ‘business-as-usual workload and resourcing.’30 The 15-day timeframe is not specifically linked to any external demands on applicants — noting that a charity can operate without being registered with the ACNC. Also, a charity’s effective date of registration can be (and often is) backdated, allowing successful applicants to seek available tax concessions through the ATO for this earlier period.

2.37 The ACNC’s Annual Reports for 2017–18 and 2018–19 state that the ACNC had met and exceeded its timeliness standard in both years — achieving a result of 98 per cent and 96 per cent respectively. In 2017–18 some 2627 new applications were registered and 2556 in 2018–19.

2.38 Analysis of the ACNC’s data shows that around half of all registration applications were finalised within two business days in both years once the ACNC deemed that all the relevant information had been received; and more than 90 per cent of applications across these two years were finalised within 10 business days (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Timeliness of the ACNC’s registration processes once final information had been received, 2017–18 and 2018–19

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s 2017–18 and 2018–19 registration data.

2.39 Analysis of the ACNC’s registration data for 2017–18 and 2018–19 showed that a sizable majority of registrations exceeded 15 business days when measured by the date of submission of an application to the date of decision (rather than from the date that final information was received to the date of decision).31 The average elapsed time for the cases exceeding 15 days was 39 business days for 2017–18 and 47 business days for 2018–19, with the longest cases taking 185 days and 341 days respectively. These timeframes take into account the time taken by applicants to respond to further ACNC information requests.

2.40 In both years, the number of applications that were not processed by the ACNC within the 15-day service standard was relatively low — 53 in 2017–18 and 95 in 2018–19. The average time to complete these cases (from the time of receiving final information) was 22 and 23 business days respectively. Most of these cases were not characterised by any particular complexity. For 2018–19 only six of the 95 cases involved a refusal of registration, which the ACNC indicated could be a reason why the timeframe was not met; and for 2017–18, the cases that took longer to process were not indicative of the ACNC’s highest risk categories for registration cases.32

Stakeholder feedback on timeliness

2.41 The ACNC uses a registration survey to gain feedback on various aspects of its registration process, including timeliness. Eighty-two per cent of respondents (as of 20 November 2019) considered that the process was timely, with six per cent indicating that it was not timely, and the balance being neutral on this question.

Has the ACNC been effective in maintaining the Charity Register?

The ACNC has been partially effective in maintaining the Charity Register. While business-as-usual processes are in place to maintain important aspects of the Register, the ACNC has identified a number of outstanding data integrity and quality assurance issues that impact on the reliability and completeness of some information. A project to make the Register a more valuable resource for users is also underway — known as the ‘Charity Marketplace’.

2.42 The Charity Register provides information on registered and formerly registered charities and is publically and freely available on the ACNC’s website.33

2.43 As outlined in the explanatory material for the ACNC Act, the requirement to establish a public register was intended to increase transparency, enabling registered charities to demonstrate appropriate levels of accountability and governance, and to promote confidence in the sector and inform choices by donors and philanthropists.

2.44 The ACNC Act and ACNC Regulation 2013 set out requirements on the type of information to be provided on, withheld, or removed from, the Charity Register. Most of the information for each registered charity is presented under four main sections — Overview; Financials and documents; People; and History (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Overview of the type of information provided on the Charity Register

|

Overview |

Financials and documents |

People |

History |

|

Basic details about the charity, including contact details, who the charity helps, what it does and where it operates. |

Annual Information Statements and Annual Financial Reports provided by the charity, the charity’s governing document (for example, a constitution) and a graphical representation of the charity’s total income and expenses. |

The names of the charity’s Responsible Persons (for example, the members of its board, committee or trustees) and the name of any other charities the Responsible Persons may be involved with. |

A list of the charity’s ‘subtype’ history and registration status history, as well as any enforcement action undertaken by the ACNC on the charity. |

Source: ANAO, based on the content of the ACNC’s Charity Register (October 2019).

2.45 The Charity Register includes a link to the Australian Business Register (maintained by the ATO), which allows users to find out if donations to the charity are tax deductible.34 The Australian Business Register also lists the type and date of any tax concessions granted to the charity by the ATO.

Business-as-usual processes

2.46 The ACNC runs a number of processes that feed information onto the Charity Register and support the reliability and completeness of the published information. These include:

- adding charities to the Register through its ongoing registration processes, including the charity’s effective registration date and registration history;

- removing charities from the Register through its compliance activities, ‘double-defaulter’ process35, and voluntary requests from charities;

- recording enforcement actions applied to a charity, where the ACNC has used enforcement powers under the ACNC Act; and

- monitoring the submission of Annual Information Statements and Annual Financial Reports from charities, which supply much of the information on the Register, as well as checking and correcting aspects of the information provided.

2.47 Registered charities have an obligation to notify the ACNC of changes to their circumstances including any non-compliance with requirements of the ACNC Act, as well as simple matters such as updating their name or address.36 The majority of data updates to the Charity Register are completed by charities through the Charity Portal.37 For instance, charities are able to update the details of ‘Responsible Persons’ and to upload a (revised) governing document.

Outstanding data integrity issues and tasks

2.48 The ACNC has identified a range of issues impacting on the integrity of the Charity Register, which it has yet to address. In total, 17 ‘un-resourced’ activities were listed in an internal memorandum, examples of which are provided in Box 4.

|

Box 4: Examples of outstanding tasks impacting on the integrity of the Charity Register |

|

Note a: The ACNC advised that, due to technical limitations with its previous system (iMIS), the decision to withhold individual data elements meant that in some cases additional data associated with the charity was also withheld. The ACNC’s new system (Dynamics) has the functionality to withhold specific data elements.

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s records.

2.49 The tasks were identified by the ACNC during a planning exercise in January 2019, with advice provided to the ACNC Commissioner in September 2019. The advice emphasised the likely impact on public trust and confidence if the general public and donors cannot rely on the accuracy of the Charity Register.

2.50 The ACNC’s initial response (in September 2019) was to raise the un-resourced data integrity work with the ATO, to explore the prospect of obtaining staff from the ATO. In January 2020, the ATO agreed to provide resources to the ACNC to assist with the outstanding data integrity work. The broader question included in the ACNC’s advice to the ACNC Commissioner was how these tasks could be undertaken on an ongoing basis — for example, by automating as many of the checks as possible.

2.51 This audit’s examination of the Charity Register data also identified a range of apparent anomalies, including cases where:

- the registration date is before the recorded ABN date;

- the registration date is before the organisation establishment date; and

- the ABN indicates that the charity is a government entity.

2.52 These type of anomalies reinforce the need for the additional data integrity checks identified by the ACNC.

Quality assurance

2.53 The ACNC is also aware of an ongoing task to quality assure the charity records provided by the ATO that remain on the Charity Register.

2.54 Since it commenced operations in December 2012, the ACNC has registered 17,660 charities (as of 30 June 2019). The remaining charities were not registered by the ACNC. The records for these charities were provided by the ATO. In September 2012, the ATO transferred around 57,000 records to the initial version of the Charity Register. The dataset comprised the ATO’s records where the entity had both an active ABN and active charity tax concession status.

2.55 The ACNC advised that much of the data provided by the ATO was out-of-date and incomplete.38 In the first few years of operation especially, the ACNC undertook a number of processes to ‘clean up’ the original Charity Register data, and has progressively implemented other measures to support the integrity of the Register. These have included the requirement for all registered charities to provide an Annual Information Statement, and through the introduction of the ACNC’s ‘double defaulter’ process in January 2015, which helps remove inactive charities from the Charity Register.39 All registered charities have a ‘duty to notify’ the ACNC of various matters including their contact details.

2.56 While over 15,000 charities have been removed from the Charity Register since the ACNC was established40, including charities that were originally provided by the ATO, the ACNC has not fully addressed the risks that remain with the ATO data. The ACNC advised that it was not resourced to provide assurance that all of the charities registered on the basis of the ATO’s data remain entitled to registration. This cohort of charities has not been subject to any specific registration review by the ACNC or been specifically targeted through the ACNC’s compliance activities.

2.57 As part of the Australian Government’s Deductible Gift Recipient reforms41 (where all non-government entities with Deductible Gift Recipient status will be automatically registered as charities with the ACNC) additional funding of $2.7 million is being provided to the ACNC and the ATO from 1 July 2020 to review Deductible Gift Recipient eligibility and entities’ ongoing entitlement to Commonwealth tax concessions. This process provides an opportunity for the ACNC to progressively review some of the data provided by the ATO. In January 2020, the ACNC advised that it expects to review two per cent of charities a year from 1 July 2020 (equating to approximately 500 charities a year).

Recommendation no.2

2.58 The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission investigates feasible and cost-effective approaches to improving the integrity of the information on the Charity Register, including, as appropriate, automating as many of the outstanding data integrity tasks as possible through its existing processes and systems.

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission response: Agreed.

2.59 The ACNC takes a continuous improvement approach to managing data integrity, which includes looking for opportunities to introduce automation wherever possible.

Australian Taxation Office response: Noted.

2.60 The ATO relies on the ACNC providing an assurance that charities on the ACNC register remain entitled to registration. The integrity of the register is essential to the ATO’s Not-for-profit Centre’s ability to provide assurance that registered charities are correctly accessing tax concessions.

Project to improve the value of the Charity Register

2.61 The ACNC’s current focus is on redesigning aspects of the Charity Register to better present data to inform donor decision-making. This initiative is known as the ‘Charity Marketplace’.

2.62 From 1 July 2020, the ACNC will start collecting information from registered charities at a ‘program’ level rather than the current general description of their activities. Specifically, charities will be required in their Annual Information Statement to:

- provide the name of at least one program (and up to 10 programs);

- classify the type of program (using a taxonomy designed to classify charity sector initiatives and organisations by subject and population); and

- state the location of the program(s).42

2.63 The ACNC’s goal is to provide a ‘common language’ that can be used by charities and donors. The collection of this information will replace questions in the Annual Information Statement about activities, beneficiaries and operating location.

2.64 According to the ACNC, the expected benefit of the Charity Marketplace is to allow users to more easily find charities that deliver the kinds of programs that they are interested in supporting, enabling more informed giving; and to encourage more people to use the Charity Register. The ACNC Commissioner’s assessment is that some of the information currently collected from charities and reported on the Charity Register is not particularly useful to users, especially donors.

2.65 Under the ACNC Act, the ACNC is only permitted to mandatorily collect information from charities that relates to a ‘recognised assessment activity’, which involves assessment of a registered charity’s: entitlement to registration; compliance with the ACNC Act and regulations; and compliance with any taxation law. The ACNC can request that charities provide information that is not covered by these activities, but cannot mandate the provision of that information.

2.66 The ACNC Commissioner foreshadowed the development of the Charity Marketplace initiative in Corporate Plans and discussed it with stakeholders including at public fora. As well, a limited number of stakeholders were consulted during the design process for the initiative.

2.67 The ACNC intends to assess the success of the Charity Marketplace principally through the number of ‘hits’ on the ACNC’s webpages, which would indicate use of the program data and related search functions. It is suggested that a wider evaluation of the initiative within two years of its launch would also be beneficial, including to inform any further decisions on how to maximise the usefulness of the Charity Register to external users.

3. Supporting ongoing compliance by charities

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission’s (ACNC’s) arrangements for supporting charities to meet their ongoing compliance obligations.

Conclusion

The ACNC has been largely effective in supporting charities to meet their ongoing compliance obligations, particularly by providing guidance and monitoring charities’ compliance. It has been less effective in addressing non-compliance. Improvements to the ACNC’s compliance processes and measurement of outcomes would better support the objective of maintaining, protecting and enhancing public trust and confidence in the charities sector.

Areas for improvement

This chapter makes two recommendations — one aimed at improving the ACNC’s compliance arrangements (paragraph 3.56); the other at better measuring public trust and confidence in the charities sector (paragraph 3.75).

3.1 Once registered, charities have a range of ongoing obligations, including to: be in compliance with the Governance Standards and (where required) the External Conduct Standards; report information annually; notify the ACNC of certain changes (such as to their governing document or Responsible Persons); and keep appropriate records.

3.2 In determining whether the ACNC has been effective in supporting ongoing compliance by charities, this chapter examines whether the ACNC’s regulatory arrangements for assisting charities, and for monitoring compliance and undertaking risk-based compliance and enforcement activities, are well-aligned to the ACNC’s stated regulatory approach — as principally articulated in its published Regulatory Approach Statement.43

3.3 This chapter also examines whether the ACNC has established suitable arrangements to measure and report on its effectiveness in meeting the first of its three corporate objectives: to maintain, protect and enhance public trust and confidence in the not-for-profit sector.

Has the ACNC been effective in assisting charities to understand and meet their ongoing compliance obligations?

Consistent with the main focus of its Regulatory Approach Statement, the ACNC has been largely effective in assisting charities to understand and meet their ongoing compliance obligations. The ACNC has well-established arrangements for providing guidance and support to charities. It also has regular processes for prompting and encouraging charity compliance, although in 2018–19 the number of registered charities that lodged their Annual Information Statement on time (70 per cent) fell short of the ACNC’s performance target (75 per cent).

3.4 The ACNC Act provides a clear role for the ACNC Commissioner, in furthering the objects of the Act, to assist charities in complying with and understanding the Act by providing them with guidance and education.44

3.5 The importance of this approach is reflected in the ACNC’s Regulatory Approach Statement, which states that:

- much of the ACNC’s work involves preventing problems by providing information, support and guidance to help charities stay on track; and

- where possible, the ACNC will work collaboratively with charities to address concerns.

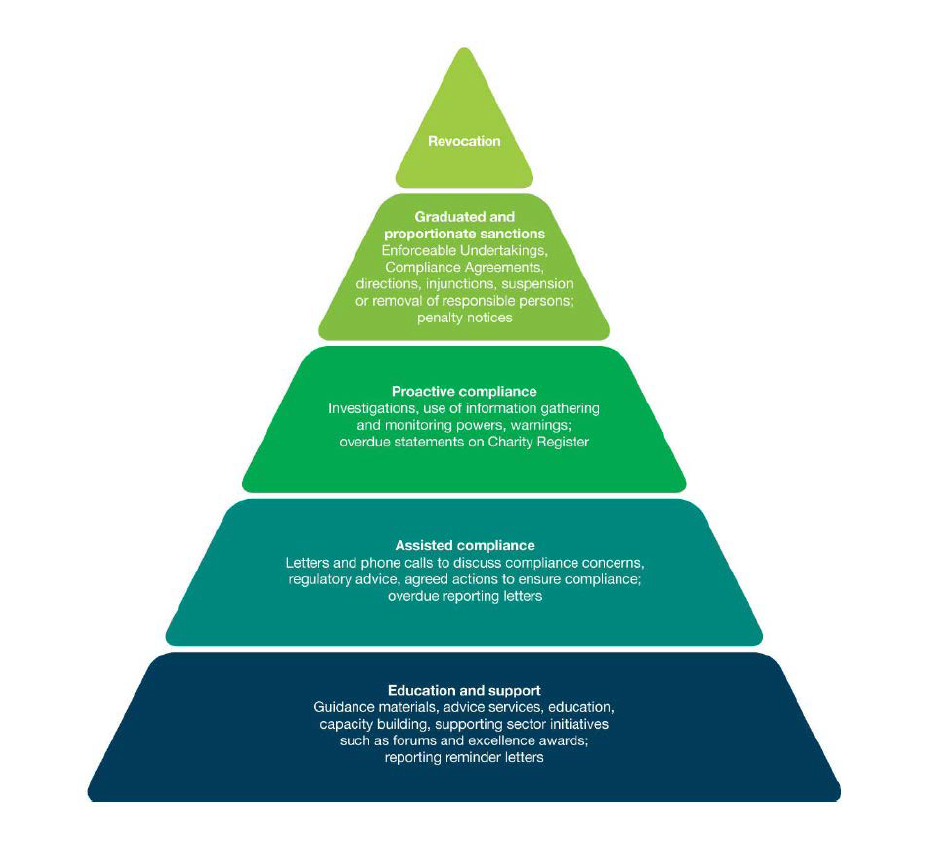

3.6 The provision of ‘Education and support’ comprises the bottom layer of the ACNC’s regulatory pyramid of support and compliance (Figure 3.1) — that is, the main actions the ACNC seeks to take, at least initially, to support and promote charity compliance.

Figure 3.1: The ACNC’s regulatory pyramid of support and compliance

Source: Reproduced from the ACNC’s Regulatory Approach Statement (December 2018), available at: https://www.acnc.gov.au/raise-concern/regulating-charities/regulatory-approach-statement [accessed 22 October 2019].

Providing education and support

3.7 Various parts of the ACNC assist in providing education and support to registered charities and to broader stakeholders — in particular, the Advice Services team and the Education and Public Affairs team.

3.8 Key means through which the ACNC provides support include:

- a dedicated contact centre, which operates from 9:00am to 5:00pm, Monday to Friday, and is the first point of contact for many charities and members of the public;

- a public website, which provides information, guidance and other material to users, including on the Governance Standards and the External Conduct Standards; and

- engagement with the charities sector through a variety of channels including: podcasts; webinars; newsletters; social media accounts; and presentation or attendance at sector meetings and fora.

3.9 The ACNC’s website includes a section on ‘Guidance and Tools’, under which a substantial number of documents are available including factsheets, guides, Commissioner’s Interpretation Statements, templates for charities, and reports released by the ACNC (including the annual Australian Charities Report).

3.10 The large volume of material on the ACNC’s website can make it difficult to locate relevant documents. A recent initiative by the ACNC to improve accessibility was to establish a ‘Governance Hub’ within the website, which brings together a range of guidance and material on governance matters. This includes: specific material for small charities; a guide for charity board members; and a self-evaluation tool to assist charities to assess whether they are meeting their obligations as a registered charity. There would be benefit in extending this approach to other parts of the website, to help make other material easier to locate and use.

3.11 The ACNC’s 2018–19 Annual Report noted that the ACNC did not meet its service standards relating to general telephone enquiries, general correspondence or responding on time when charities lodge a form to update their details. In particular, the average response time for telephone calls to its contact centre was reported to be seven minutes, which was above the target response time of four minutes. The ACNC stated that the standard was not met due to the transition to a new IT system, which initially caused a significant increase in demand to assist customers to access the new Charity Portal.

Feedback mechanisms

3.12 The ACNC’s practice is to consult with stakeholders when developing significant new pieces of guidance. This includes members of its two main consultative groups: the Professional User Group (PUG)45 and the Sector User Group (SUG)46 and with relevant regulators and other entities. Members of the PUG and SUG have typically met with the ACNC three times per year (sometimes in combined meetings), but the ACNC does not keep formal records of these meetings.

3.13 Examples of consultation include: the recently-released External Conduct Standards; refinements to the 2017 Annual Information Statement form; and guidance on the website such as on ‘Gifts and Honorariums’ and registration requirements (the Step-by-Step guide).

3.14 Other mechanisms used by the ACNC to assess the value of its guidance material include:

- analysis of enquiry data to the contact centre (Advice Services), which has resulted in the preparation of new guidance material for charities; and

- an online survey made available to applicants for registration, which includes a question on whether applicants made use of the guidance material on the ACNC’s website.47

3.15 Following a review of its consultation mechanisms in 2019, the ACNC Commissioner decided to make a series of changes from 2020. This includes: changing the name of the two main consultative groups to the Advisor Forum (previously PUG) and the Sector Forum (previously SUG); reducing the number of consultation meetings to two per year; producing high-level minutes of the meetings, which will be sent to participants and published on the ACNC’s website; trialling facilitated small group sessions; and surveying small charities to better understand their consultation needs.

Supporting charities to meet their annual reporting obligations

3.16 The annual reporting obligations on registered charities is a key mechanism to support public trust and confidence in the sector.48 The ACNC uses various means to promote and support charities’ timely compliance with the requirement to provide Annual Information Statements and (as applicable) Annual Financial Reports.

3.17 For 2017–18, the ACNC’s performance target was that 80 per cent of registered charities lodge their Annual Information Statement on time — typically within six months after the end of the charity’s applicable reporting period.49 From 2018–19 to 2022–23 the ‘on time’ target has been reduced to 75 per cent of registered charities. The ACNC advised that the target was reduced in anticipation of a lower on time response rate until charities became familiar with the new Charity Portal (through which Annual Information Statements are generally prepared and sent). The ACNC’s intention is to leave the target at 75 per cent until it can realistically achieve a higher rate.

3.18 The ACNC’s website includes a range of material to assist charities to meet their annual reporting obligations. This includes an ‘Annual Information Statement hub’ with links to a guide and checklist, and a means to navigate the new 2018 Annual Information Statement form. As well, the ACNC’s standard practice is to send two reminder letters to charities before their Annual Information Statement is due and a ‘late filer’ notice if the charity fails to submit on time. The ACNC has also issued penalty notices to selected charities (typically large charities) that have failed to lodge an Annual Information Statement (although no penalties were issued in 2018–19).50 The ACNC advised that continued non-compliance by a charity following receipt of a penalty notice and failure to submit the subsequent Annual Information Statement would result in the charity’s registration being revoked (through the ACNC’s double-defaulter process).

3.19 For 2017–18, the ACNC reported that 72 per cent of registered charities had lodged their Annual Information Statement on time. For 2018–19, 70 per cent of charities lodged on time, below the ACNC’s 75 per cent target. For charities that are more than six months overdue51, the ACNC activates a ‘red flag’ on the charity’s entry in the Charity Register to signal that charity reporting is not up to date.52

Has the ACNC been effective in monitoring charities and undertaking risk-based compliance and enforcement activities?

The ACNC has been largely effective in monitoring charities’ compliance in accordance with its stated regulatory approach, but less effective in undertaking risk-based compliance and enforcement activities. The ACNC relies mainly on external parties to identify compliance concerns, and is improving its arrangements for allocating available resources to identified compliance priorities. Complexity in determining whether charities are ‘federally regulated entities’ has limited the ACNC’s use of enforcement powers and reporting of enforcement results for deterrence purposes.

3.20 The ACNC’s Regulatory Approach Statement articulates the ACNC’s intended approach to identifying and managing compliance risks for registered charities. This includes statements that the ACNC:

- monitors compliance by: assessing information provided by charities in their Annual Information Statements and Annual Financial Reports53; assessing concerns received from the community and other government entities; and undertaking data-matching and intelligence projects;

- uses a risk-based approach to allocate its compliance resources when addressing concerns about charities and is not resourced to investigate every regulatory concern brought to its attention; and

- will take action proportionate to the problem it is seeking to address, and will not hesitate to use its powers when charities do not act lawfully and reasonably — noting that revocation of registration may be appropriate in certain circumstances.54

Monitoring registered charities

3.21 The ACNC has undertaken the three main forms of monitoring referred to in its Regulatory Approach Statement.

3.22 The ACNC’s main focus in assessing the annual information provided by charities is to improve the accuracy of the information on the Charity Register. The Annual Information Statements and Annual Financial Reports required to be provided by (relevant55) charities are automatically uploaded to the Charity Register when submitted through the online Charity Portal. The ACNC does not seek to examine all of these reports or all of the information in these reports. Its practice has been to examine selected information in selected reports, focussing on the quality and completeness of the financial information and on specific matters such as whether the charity has correctly identified itself as a Basic Religious Charity (Box 5).56

|

Box 5: Data integrity checks undertaken by the ACNC on charities’ 2017 Annual Information Statements |

|

The ACNC’s data integrity strategy for the 2017 Annual Information Statements outlined three levels of checking, which correspond to performance criteria in the ACNC’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan.

|

Note a: The Level 1 checks are system-generated checks based on the Annual Information Statements submitted by charities.

Note b: Such as: an income statement; a balance sheet; a signed audit or review report; and a Responsible Person’s declaration and signature.

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s internal data integrity strategy for the 2017 Annual Information Statement.

3.23 The ACNC reported that as a result of its data integrity checks on charities’ 2017 Annual Information Statements, it contacted 747 charities that made errors; and in turn corrected significant aggregate errors on the Charity Register to charities’ reported revenue, assets and number of full-time employees.

3.24 To help promote and assist compliance, the ACNC prepares a data integrity strategy for monitoring the quality of charities’ reporting and publishes a report on the type of errors found during the annual reporting cycle.

3.25 In reviewing charities’ information, many of the errors identified by the ACNC (through its desk-based reviews) relate to inconsistencies between the financial information provided by charities in their Annual Information Statements and in their Annual Financial Reports.57 The ACNC sends a letter asking the charity to correct the information and to re-submit the relevant report(s).

3.26 Charities are not required in their Annual Information Statements to declare (re-confirm) that they remain in compliance with the Governance Standards; nor are charities required, as a matter of course, to provide documentation to evidence their compliance with the Standards. Charities are required to answer some questions that relate to aspects of the Governance Standards, including whether the charity had any ‘related party transactions’58 and whether the charity has documented policies or processes about related party transactions. These particular questions are aimed at identifying any private benefits, and potential breaches of Governance Standard 1 (Purposes and not-for-profit nature) and Governance Standard 5 (Duties of Responsible Persons).

3.27 The Annual Information Statement is a key means to provide transparency on the activities of registered charities; and the ACNC is able to collect information via these Statements that support its assessment of an entity’s ongoing compliance obligations. In this context, the ACNC should make greater use of this annual reporting process to monitor whether charities are complying with the Governance Standards. This approach could be informed by a structured assessment such as a cost-benefit analysis, to balance the expected compliance benefits against any increase in regulatory burden on charities.

Concerns received about charities

3.28 In 2018–19, the ACNC received59 the highest ever number of concerns about charities — with 154460 of those concerns assessed to be ‘in-jurisdiction’61 (Figure 3.2) relating to 659 charities. More than 500 of the concerns received in 2018–19 related to two charities.

Figure 3.2: Number of charity concerns received by the ACNC

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s published data.

3.29 Of the 1544 concerns, 667 were provided by members of the public, with other major sources including: other government entities; media reports; and past and present charity employees. The ACNC’s categorisation of the concerns received shows that private benefit and criminal or improper purposes feature the most often (Figure 3.3).62

Figure 3.3: ACNC’s categorisation of the main risk concerns received about charities

Note: This figure shows the top four categories only, which equated to 1240 concerns. The remaining 10 categories comprised 304 concerns.

Source: ANAO, based on the ACNC’s data.

Data-matching and intelligence projects

3.30 In recent years, the ACNC has undertaken five main initiatives in relation to its stated approach of undertaking data-matching and intelligence projects to identify areas of risk. The projects are summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Data-matching and intelligence projects undertaken by the ACNC

|

Initiative |

Description |

|

Closely-held charities (2017) |

Investigate charities that sent or received money from tax havens. This project was part of a joint risk assessmenta between the ACNC and the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) in 2017 on money laundering and terrorism financing in Australia’s NFP organisation sector. |

|

Terrorism financing (2017) |

Investigate charities with potential terrorism financing risks or organised crime links. This project arose out of the joint risk assessment between the ACNC and AUSTRAC. |

|

Disqualifying purpose (2018) |