Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Procurement of Garrison Support and Welfare Services

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The ANAO's two previous audit reports into the department's management of offshore garrison support and welfare contracts identified a range of shortcomings and deficiencies.

- Since 2017, the department has entered into contracts totalling in excess of $1 billion; and it is timely to assess whether the department has improved its procurement and performance management processes.

Key facts

- In March 2014, the department contracted Broadspectrum (BRS) for the provision of garrison support and welfare services in both Nauru and PNG. This contract expired on 31 October 2017.

- In preparation for the cessation of the BRS contract, the department commenced processes to procure garrison support and welfare services for both Nauru and Manus Island and subsequently entered into contracts with Canstruct; JDA; NKW; and Paladin.

What did we find?

- The Department of Home Affairs' management of the procurement of garrison support and welfare services for offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG was largely appropriate.

- Procurement activities were conducted largely in accordance with the CPRs.

- Contractor performance reporting and monitoring was partly adequate due to delays in the establishment of the associated contractual frameworks.

- The department has substantially implemented the recommendations of previous ANAO and Parliamentary reports.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made two recommendations to the department of Home Affairs regarding documentation of decisions in limited tender procurements and interim performance reporting while contract negotiations are being finalised.

- The Department agreed to the recommendations.

$7.1 billion

has been the total cost of regional processing arrangements in Nauru and PNG.

72%

decrease in the asylum seeker population in Nauru from 1233 in August 2014 to 345 in October 2017.

49%

decrease in the asylum seeker population in PNG from 1353 in January 2014 to 690 in October 2017.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In 2012, the Australian Government established Regional Processing Centres (RPCs)1 in the Republic of Nauru (Nauru) and Papua New Guinea (PNG). The centres were established through Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) between the Australian Government and the Nauruan2 and PNG governments3 respectively. Under both agreements, the Australian Government was to bear all costs incurred under the MOUs.

2. Since 2012, the Department of Home Affairs4 (the department) has been responsible for the procurement of garrison support and welfare services functions for the RPCs and the establishment and ongoing management of associated contractual arrangements. Garrison support includes security, cleaning and catering services. Welfare services include individualised care to maintain health and well-being, such as recreational and educational activities.

3. In March 2014, the department contracted Broadspectrum (Australia) Pty Ltd5 (BRS) for the provision of garrison support and welfare services in both Nauru and PNG. This contract expired on 31 October 2017. In preparation for the cessation of the BRS contract, the department commenced processes to procure garrison support and welfare services for both Nauru and Manus Island and subsequently entered into four contracts with Canstruct International Pty Ltd; JDA Wokman Ltd; NKW Holdings Ltd; and Paladin.6

4. The department's estimate of the total cost of regional processing arrangements in Nauru and Papua New Guinea, since establishment, is $7085.14 million.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. On 19 February 2019 and 18 March 2019, the Auditor-General received correspondence from the Hon Shayne Neumann MP, Shadow Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, requesting 'an urgent audit into the circumstances surrounding the Department of Home Affairs' procurement of garrison support and welfare services in Papua New Guinea.'7

6. Implementation of the Australian Government's policies on offshore detention of refugees and asylum seekers over the last ten years has cost billions of dollars. The operation of RPCs have been a subject of substantial parliamentary and public interest. The ANAO's two previous audit reports8 into the department's management of offshore garrison support and welfare contracts identified a range of shortcomings and deficiencies. Since the tabling of the audit reports, the department has entered into further contracts totalling in excess of $1 billion; and it is timely to assess whether the department has improved its procurement and performance management processes.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective was to assess whether the Department of Homes Affairs has appropriately managed the procurement of garrison support and welfare services for offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG (Manus Island).

8. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- procurements were conducted in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and value for money principles;

- contractor performance is adequately reported and monitored; and

- the department has implemented recommendations and actions arising from previous Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) and ANAO reports on the procurement of garrison support and welfare services.

Conclusion

9. The Department of Home Affairs' management of the procurement of garrison support and welfare services for offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG was largely appropriate.

10. Procurement activities for the provision of garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island and Nauru were largely undertaken in accordance with the CPRs. The department utilised provisions of the CPRs to allow for an exemption from requirements for the use of open tender procurements on Manus Island and Nauru. The department did not document its reasons for requesting quotations from Paladin, JDA and NKW as required by the CPRs. The department demonstrated the achievement of value for money for the Nauru procurement, but for Manus Island it did not appropriately benchmark costs for similar services, and the effectiveness of negotiations with providers was unclear due to the department's substantial expansion of the services required during the negotiation process. A probity management framework was established but it was not effectively applied in all instances.

11. Contractor performance reporting and monitoring was partly adequate. There were no performance monitoring or reporting requirements for an average of more than eight months during the time that the respective contractors operated under Letters of Intent prior to the signing of contracts. Once established, contracts contained detailed management plans and reporting frameworks which were appropriately applied by the department in most instances to monitor contractor performance. Payments to contractors during the contract negotiation period were not supported by Letters of Intent in all instances.

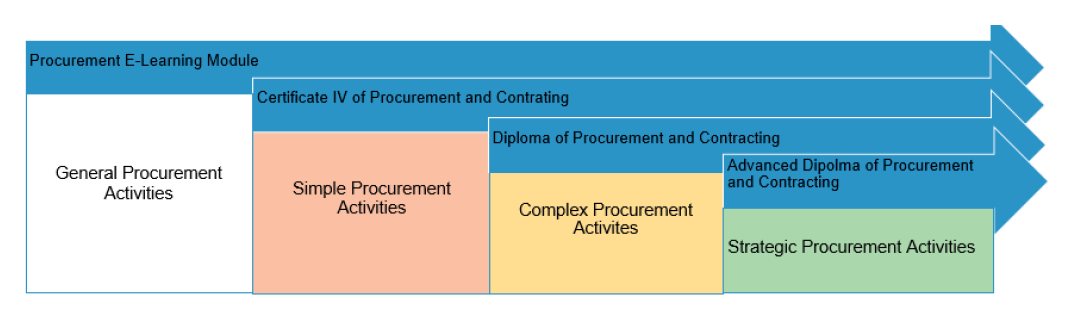

12. The department has substantially implemented the recommendations of Auditor-General Report No. 16 2016–17 and JCPAA Report 465: Commonwealth Procurement by developing training programs to address skill and capability gaps and by implementing a wide range of procurement and contract management guidance and instructional material. The department has significantly improved its record keeping practices and has reported to the JCPAA on its implementation of the ANAO's recommendations.

Supporting findings

13. For Manus Island, the accountable authority of the department took action under paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs on the basis of human health and security to exempt the procurement process from the open competition requirements. The department was aware of 11 providers that could have potentially offered some or all elements of the required garrison support and welfare services but it did not document its reasons for requesting quotations from the three selected providers.

14. The department used paragraph 10.3 of the CPRs to conduct a limited tender for Nauru. However, the department had almost 18 months' notice in May 2016 of BRS' intention not to continue or extend its contract from October 2017. Whilst the Nauruan government imposed a new layer of decision making and approval processes over regional processing service delivery contracts in August 2017, it is not clear why the department could not have secured a replacement supplier using a more competitive procurement method over this period.

15. Risk management plans were established and largely implemented for all four procurements, but planning should have specifically addressed fraud and corruption risks in the given environments.

16. The department developed a probity management framework, but it was not effectively applied in all instances. Key declaration and acknowledgement forms were not completed by all applicable personnel.

17. The department demonstrated the achievement of value for money for the Nauru procurement. Costs under the most recent contract for services, and various scenarios based on population trends and service assumptions, were used to effectively benchmark tenderer costs. Negotiations resulted in the inclusion of additional services with a modified pricing impact.

18. The department did not demonstrate the achievement of value for money for the PNG procurements. Although the department had limited options for comparing tenderer costs, most of the benchmarks it used were not appropriate. Negotiations with NKW achieved significant savings, noting that the initial tendered costs had been assessed as not representing value for money. The effectiveness of negotiation for Paladin was unclear as savings achieved for some items were offset by increases to others, the addition of a mobilisation payment and the department's substantial expansion of the services required during the negotiation process.

19. The department's due diligence inquiries were limited to financial strength assessments of all four tenderers. The financial risk for each was assessed as moderate to high.

20. Once contract management plans and performance management frameworks were established, the four contractors met all associated reporting requirements in a timely manner. However, reporting requirements did not apply while contractors were operating under Letters of Intent. As a result, contractors were not required to submit performance reports for an average of more than eight months after they first began providing services.

21. The department established a largely fit-for-purpose framework for monitoring contractor performance reporting. Contractors completed self-assessments on a monthly basis against agreed performance metrics, which were then validated through a process of review against supporting evidence and third party data. For Nauru, the permanent presence of departmental officials enabled ongoing verification of performance, whilst for Manus Island, site visits were intended to occur monthly but did not occur in all instances. Reports to the delegate contained trend analysis and highlighted any emerging issues and corrective action required. Feedback was provided to each contractor on a monthly basis and included notification of any penalties to be applied for performance failures where applicable under the contract. The department was not able to provide any rationale as to why it did not establish abatement and PIN clauses consistently across the four contracts.

22. Payments to Canstruct and Paladin were made in accordance with the relevant Letters of Intent (LOIs), but the department did not enforce the conditions of payment for Canstruct. Not all payments to JDA were supported by an LOI or applicable agreement. Payments to NKW were made above the LOI approved limit. Other payments were made to NKW outside the LOI without a contract.

23. The department has undertaken a body of work aimed at addressing recommendations arising from the respective previous ANAO reports on procurement and contract management activities for the offshore processing centres. Specifically:

- there is a suite of procurement-focused training programs tailored to workplace requirements;

- a procurement-specific page on the department's intranet contains a wide range of guidance and instructional material; and

- evidence from the fieldwork conducted for this audit indicates the department has significantly improved its record keeping practices and that staff now use the TRIM electronic data and records management system.

24. The department complied with the recommendation of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) by providing the JCPAA with a report in March 2018 on its implementation of the ANAO's recommendations.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.23

The Department of Home Affairs develop policy guidance to ensure that, where a limited tender procurement is undertaken, decisions in relation to the providers to receive requestions for quotation are accurately and concisely documented.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.11

The Department of Home Affairs develop policy guidance to ensure that, where Letters of Intent are issued to contractors pending the finalisation of contracts, interim performance reports are prepared when an assessment of key contract risks and deliverables suggests it would be prudent to do so.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Home Affairs (the Department) welcomes the ANAO's conclusions that the management of the procurement of garrison support and welfare services for offshore Regional Processing Centres (RPCs) in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (PNG) was largely appropriate, and that the Department has substantially implemented the recommendations of previous ANAO and parliamentary reports.

The management of offshore RPCs is highly complex, dynamic and involves working in collaboration with host governments in Nauru and PNG. Unlike onshore procurements, offshore procurement timeframes are impacted by bilateral government considerations, and the sovereignty of the host nation must be respected.

For Nauru, the Department was working with the Government of Nauru on timing and also had to work in line with the requirements of the Government of Nauru and Nauruan legislation. This was reflected in the introduction of the Nauru RPC Corporation Act 2017, which requires the Nauru RPC Corporation and the Nauru Cabinet to approve regional processing service delivery contracts. This requirement impacted the available timeline and the Department was not the sole authority managing the timeline.

For PNG, on 5 July 2017, advice was received from the PNG Government that PNG was not in a position to continue with any contract negotiations for current or new contracts they were undertaking. This provided the Department with limited time to procure services to support the health and welfare of transferees in Manus Island and Port Moresby. The previous provider was due to cease operations on 31 October 2017 and transition-out due to commence on approximately 1 August 2017, the PNG Government was due to have their contractors in place by this time to transition into the new contract. Failure to engage new service providers would have resulted in no services to support the health and welfare of approximately 850 transferees on the closure of the Manus RPC.

In these circumstances, the Department welcomes the ANAO finding that the Department demonstrated the achievement of value for money for the Nauru procurement, that benchmarks used by the Department were appropriate and negotiation processes effective. In relation to the PNG procurements, the Department is of the view that negotiation processes were appropriate, in light of the changed sovereign nation's operating model, the significantly restricted timeframe and the constantly changing operating environment.

The Department is committed to working within the parameters established under the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) to procure services to support activities at our offshore RPCs and we note the ANAO's finding that procurement activities for the provision of garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island and Nauru were largely undertaken in accordance with the CPRs.

As part of the procurement process, a probity management framework was developed for these procurements requiring each departmental officer involved in the procurements to complete a conflict of interest declaration at the outset of the procurement and declare any further real or perceived conflicts of interest that eventuate during the procurement process. From the Department's point of view, it is not unusual practice for a departmental officer to have multiple roles during a procurement process, both over the term of the procurement and concurrently, and we note the ANAO's observation regarding officers' ongoing obligations in terms of declaring real and perceived conflicts of interest.

The Department recognises that performance management is a vital element of successful contract management and notes the ANAO's conclusion that once contract management plans and performance management frameworks were established, contractors met all associated reporting requirements in a timely manner, and the Department established a largely fit-for-purpose framework for monitoring contractor performance.

The Department agrees with the two recommendations made by the ANAO in this report and has undertaken to implement them as a priority.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

25. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 In 2012, the Australian government established Regional Processing Centres (RPCs)9 in the Republic of Nauru (Nauru) and Papua New Guinea (PNG), with the agreement of both the Nauruan and PNG Governments.

1.2 Figure 1.1 shows the location of Manus Island and Nauru respectively.

Figure 1.1: Location of Nauru and Papua New Guinea

Source: Google Maps.

1.3 Initially, the RPC on Nauru was located at a single site. Following a riot and fire at the Nauru site in July 2013, RPC activities there were distributed across three sites.10

1.4 In PNG, the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre (MIRPC) was established in September 2012 at the Lombrum Naval base. Following the closure of the MIRPC in October 2017 (see paragraph 1.10), arrangements on Manus Island were distributed across three sites:

- East Lorengau Refugee Transit Centre (ELRTC)11;

- West Lorengau Haus; and

- Hillside Haus.

Figure 1.2 shows the location of these facilities on Manus Island.

Figure 1.2: Manus Island

Source: UNHCR website.

1.5 The centres were established under Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) between the Australian Government and the Nauruan12 and PNG governments13 respectively. Under both agreements, the Australian Government was to bear all costs incurred under the MOUs.

1.6 Transfers of asylum seekers to Nauru commenced on 14 September 2012 and to Manus Island on 21 November 2012.

1.7 Since 2012, the Department of Home Affairs14 (the department) has been responsible for the procurement of garrison support and welfare services functions for the RPCs and the establishment and ongoing management of associated contractual arrangements. Garrison support includes security, cleaning and catering services. Welfare services includes individualised care to maintain health and well-being, such as recreational and educational activities.

1.8 The department advised that the total cost of regional processing arrangements in Nauru and PNG since establishment are as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Cost of regional processing arrangements by financial year — 2012–13 to 2018–19

|

Financial year |

Nauru ($m) |

PNG (Manus Island) ($m) |

Total ($m) |

|

2012–13 |

282.90 |

75.87 |

358.77 |

|

2013–14 |

684.38 |

622.56 |

1306.94 |

|

2014–15 |

541.09 |

772.11 |

1313.20 |

|

2015–16 |

614.57 |

524.34 |

1138.91 |

|

2016–17 |

538.26 |

452.11 |

990.37 |

|

2017–18 |

521.77 |

515.88 |

1037.65 |

|

2018–19 |

511.63 |

427.67 |

939.30 |

|

Total |

3694.60 |

3390.54 |

7085.14 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

Recent history of contractual arrangements for garrison support and welfare

1.9 In March 2014, the department contracted Broadspectrum (Australia) Pty Ltd15 (BRS) for the provision of garrison support and welfare services in both Nauru and PNG.

1.10 On 26 April 2016, the Supreme Court of PNG ruled that detention of asylum seekers was unconstitutional. On the following day, the PNG Government announced its intention to close the centre.

1.11 In May 2016, BRS advised that it would not participate in any further tenders or contracts to supply garrison support and welfare services to the Australian Government. It agreed to extend its existing contract until the end of October 2017.16

1.12 Between November 2016 and March 2017, the department commenced negotiations with the PNG Government in relation to the new policy arrangements, with the intention of PNG assuming independent management of arrangements for existing asylum seekers from October 2017. To support this transition, the department was assisting the PNG Immigration and Citizenship Authority (ICA)17 to procure associated services (refer paragraph 2.6).

1.13 On 5 July 2017, at a meeting of senior officials, ICA informed the department that, due to the forthcoming general election, the PNG State Solicitor had directed that officials not enter into any service contracts that would continue beyond 31 October 2017 before the formation of an elected government.

1.14 On 31 July 2017, the department obtained approval from the Minister to procure garrison support and welfare services for both Nauru and Manus Island in order to allow the continuation of these services after 31 October 2017. The department subsequently entered into four contracts18 as listed in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Contracts for garrison support and welfare services

|

Service provider |

Services provided |

Contract period |

Contract value ($m) |

|

Canstruct International Pty Ltd (Canstruct) |

Garrison and Welfare Services Nauru (RPC 1, 2, 3) |

28 September 2017 to 30 June 2020 |

1122.0a |

|

JDA Wokman Ltd (JDA) |

Settlement Services (ELRTC, Hillside Haus, West Lorengau Haus) |

4 December 2017 to 30 June 2020 |

77.0 |

|

NKW Holdings Ltd (NKW) |

Site Management Services (Hillside Haus, West Lorengau Haus) |

21 September 2018 to 30 November 2019 |

136.0 |

|

Paladinb |

Garrison Services (ELRTC and additional sites) |

21 September 2017 to 30 November 2019 |

532.0 |

|

Total |

1867.0 |

||

Note a: The figure of $1,122 million is from departmental documentation. The figure recorded on AusTender is $1,116 million, a difference of $6 million.

Note b: Paladin comprises Paladin Solutions PNG Ltd and Paladin Holdings PTE Ltd. Paladin Solutions PNG Ltd initially provided garrison services at the ELRTC, under a Letter of Intent, between September 2017 and February 2018. Paladin Solutions PTE Ltd provided garrison services upon contract execution on 28 February 2018. For the purposes of this audit, the Paladin contracts are considered as one procurement.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

Previous audit reports on offshore processing procurements and contracts

1.15 The ANAO conducted two performance audits in 2016–17 for the procurement and contract management of garrison support and welfare services.19 These audits assessed whether the department had appropriately:

- managed the procurement of garrison support and welfare services at offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG (Manus Island);

- established and managed the contracts for garrison support and welfare services at offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG (Manus Island); and

- met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, including consideration and achievement of value for money (for both procurement and contract management).

1.16 The audits found, respectively, that the department’s management of procurement activity and management of contracts for garrison support and welfare services at the RPCs had ‘fallen well short’ of effective practice.20 The audits made a total of five recommendations.

Other relevant performance audit reports

1.17 Prior to the 2016–17 audits, the ANAO had conducted five audits21 since 2004 that focused on the department’s management of detention centre contracts. Each of these audits identified shortcomings in the department’s contract management and procurement activities of detention services.

Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit

1.18 Auditor-General Report No. 16 2016–17 was one of three ANAO reports22 selected for an inquiry into Commonwealth Procurement by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) in October 2016. In September 2017, the JCPAA published Report 465: Commonwealth Procurement. The JCPAA made two recommendations23, which are discussed further in Chapter 4.

Commonwealth Procurement Framework

1.19 Figure 1.3 summarises the core elements of the Commonwealth procurement framework. Key aspects of the framework which are relevant to this audit are discussed in paragraphs 1.21 to 1.33.

Figure 1.3: The Commonwealth Procurement framework

Source: Commonwealth Procurement Rules 2017, Department of Finance.

Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013

1.20 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) came into force on 1 July 2013. Section 15 of the Act requires entities to promote the proper use24 and management of public resources for which the authority is responsible.

1.21 Under section 23 of the PGPA Act, the accountable authorities of non-corporate Commonwealth entities have power to enter, vary or administer an arrangement, and approve commitments of relevant money, on behalf of the Commonwealth.

Commonwealth Procurement Rules

1.22 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) are issued by the Minister for Finance under subsection 105B(1) of the PGPA Act.

1.23 The CPRs govern how entities buy goods and services. The CPRs state:

Procurement encompasses the whole process of acquiring goods and services. It begins when a need has been identified and a decision has been made on the procurement requirement. Procurement continues through the processes of risk assessment, seeking and evaluating alternative solutions, the awarding of a contract, the delivery of and payment of goods and services and, where relevant, the ongoing management of the contract and consideration of disposal of goods.25

1.24 A core principle of the CPRs is achieving value for money. The CPRs provide that officials must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that a procurement achieves a value for money outcome. Value for money is determined by: encouraging competition and being non-discriminatory; using public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner; facilitating accountable and transparent decision-making; appropriate engagement with risk; and being commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.

1.25 The CPRs consist of two divisions:

- Division 1 — rules applying to all procurements regardless of value. Officials must comply with the rules of Division 1 when conducting procurements; and

- Division 2 — additional rules that apply to all procurements valued at or above the relevant procurement threshold (unless exempted under Appendix A of the CPRs).

The department’s procurement of garrison support and welfare services

1.26 The department conducted procurement activity for the garrison support and welfare services engagements using two key elements of the CPRs.

for the maintenance or restoration of international peace and security, to protect human health, for the protection of essential security interests, or to protect national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value.

- For Nauru, Canstruct was issued with a Request for Quotation (RFQ) under paragraph 10.3, which allows for the conduct of procurement through limited tender in certain circumstances.

- For Manus Island, RFQs were issued for separate services at specific sites to JDA, NKW and Paladin under paragraph 2.6, which allows an accountable authority to apply ‘special measures’ determined to be necessary:

1.27 On 10 August 2017, the Secretary of the department, as the accountable authority, exercised his authority to invoke paragraph 2.6 in relation to the Manus Island procurements ‘for the protection of essential security interests and human health’.

1.28 The provisions of paragraphs 2.6 and 10.3 are set out in full in Appendix 2.

Accountable Authority Instructions

1.29 In addition to the requirements of the CPRs, section 20A of the PGPA Act authorises accountable authorities to give instructions, known as Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs), to assist officials to understand their duties and responsibilities under the PGPA Act. AAIs are legally binding and may contain links to relevant legislative requirements, guidance material, authorisations and other instructions.

1.30 Paragraph 3.81 of the department’s AAIs requires that the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) authorise the use of limited tender for procurement at or above the relevant procurement threshold, as described in paragraph 10.3 of the CPRs.

Other relevant internal documentation

1.31 To meet the department’s undertakings in response to Auditor-General Report No. 16 2016–17, on 12 March 2017, the department mandated additional governance arrangements for high risk, high value procurements. The governance arrangements for procurements allocated high risk, high value status is shown at Appendix 3.

1.32 The key additional governance arrangements for procurements classified as high risk, high value include:

- high risk, high value status is allocated by the CFO, Chief Risk Officer (CRO) and General Counsel (GC)26;

- financial delegation sits at the deputy secretary or deputy commissioner level;

- oversight of the procurement by a steering committee of Senior Executive Service members, including the CFO and CRO;

- written endorsement from the CFO and GC to the delegate at four mandatory gateways27 to provide the delegate with confirmation that each stage of the procurement complies with the department’s AAIs, financial guidelines and legal principle and practice;

- mandatory documentation requirements for all high risk, high value procurements;

- Procurement and Contracts Branch (PCB) coordinates all high risk, high value processes and also reports quarterly to the Capability Planning and Resource Committee; and

- potential audits are identified by the PCB28 in consultation with the relevant business area’.29

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.33 On 19 February 2019 and 18 March 2019, the Auditor-General received correspondence from the Hon Shayne Neumann MP, Shadow Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, requesting ‘an urgent audit into the circumstances surrounding the Department of Home Affairs’ procurement of garrison support and welfare services in Papua New Guinea.’30

1.34 Implementation of the Australian Government’s policies on offshore detention of refugees and asylum seekers over the last ten years has cost billions of dollars. The operation of RPCs have been a subject of substantial parliamentary and public interest. The ANAO’s two previous audit reports into the department’s management of offshore garrison support and welfare contracts identified a range of shortcomings and deficiencies. Since the tabling of the audit reports, the department has entered into further contracts totalling in excess of $1 billion; and it is timely to assess whether the department has improved its procurement and performance management processes.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.35 The audit objective was to assess whether the Department of Homes Affairs has appropriately managed the procurement of garrison support and welfare services for offshore processing centres in Nauru and PNG (Manus Island).

1.36 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- procurements were conducted in accordance with the CPRs and value for money principles;

- contractor performance is adequately reported and monitored; and

- the department has implemented recommendations and actions arising from previous JCPAA and ANAO reports on the procurement of garrison support and welfare services.

1.37 The audit scope for the selected procurements and contracts entered into by the department, and its predecessor agencies, were based on the following:

- procurements involving the provision of garrison support and welfare services at RPCs; and

- procurements which were material31 and have been undertaken following the tabling of the two ANAO performance audit reports in 2016–17.32

1.38 On this basis, four33 procurements were identified and are shown above at Table 1.2.

1.39 Auditor-General Report No. 32 2016–17 identified deficiencies in the department’s contract management practices, particularly around contract reporting and management. Consequently, while this report is principally concerned with the department’s management of the procurement process, it also examines contract reporting and management arrangements for each of the contracts.

1.40 Finally, the report examines whether the department implemented the recommendations from Auditor-General Report No. 16 2016–17 and the JCPAA’s recommendations in Report 465: Commonwealth Procurement.

Audit methodology

1.41 The audit methodology included:

- examination and analysis of departmental records;

- interviews with relevant departmental staff;

- interviews with relevant non-departmental stakeholders; and

- sworn testimony under oath obtained using the powers provided by section 32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997.

1.42 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $900,000.

1.43 The team members for this audit were Julian Mallett, Amanda Ronald, Robyn Clark, Renee Hall, Shane Armstrong, Mary Huang and Paul Bryant.

2. Procurement of garrison support and welfare contracts

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether procurement activity for the provision of garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island and Nauru was conducted in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and value for money principles.

Conclusion

Procurement activities for the provision of garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island and Nauru were largely undertaken in accordance with the CPRs. The department utilised provisions of the CPRs to allow for an exemption from requirements for the use of open tender procurements on Manus Island and Nauru. The department did not document its reasons for requesting quotations from Paladin, JDA and NKW as required by the CPRs. The department demonstrated the achievement of value for money for the Nauru procurement, but for Manus Island it did not appropriately benchmark costs for similar services, and the effectiveness of negotiations with providers was unclear due to the department’s substantial expansion of the services required during the negotiation process. A probity management framework was established but it was not effectively applied in all instances.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation regarding the documentation of decisions on the providers to receive a request for quotation in limited tender processes.

2.1 Paragraph 4.4 of the CPRs states that ‘officials responsible for a procurement must be satisfied, after reasonable enquiries, that the procurement achieves a value for money outcome’. The CPRs state that competition is a key element of the procurement framework and, generally, an open and competitive tender process helps entities to achieve a value for money outcome. However, as noted in Chapter 1, the CPRs recognise that there can be circumstances (such as urgency) which militate against conducting a full open tender process.

2.2 As outlined in Chapter 1, the department used limited tender34 processes to conduct the four procurements for garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island and Nauru. This chapter examines whether the department met the CPR requirements for using this procurement method, together with the identification of potential providers, demonstration of value for money, management of probity and the conduct of due diligence in relation to the Manus Island and Nauru procurements.

Did the department meet the CPR requirements for conducting limited tenders or direct engagement?

For Manus Island, the accountable authority of the department took action under paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs on the basis of human health and security to exempt the procurement process from the open competition requirements. The department was aware of 11 providers that could have potentially offered some or all elements of the required garrison support and welfare services but it did not document its reasons for requesting quotations from the three selected providers.

The department used paragraph 10.3 of the CPRs to conduct a limited tender for Nauru. However, the department had almost 18 months’ notice in May 2016 of BRS’ intention not to continue or extend its contract from October 2017. Whilst the Nauruan government imposed a new layer of decision making and approval processes over regional processing service delivery contracts in August 2017, it is not clear why the department could not have secured a replacement supplier using a more competitive procurement method over this period.

Risk management plans were established and largely implemented for all four procurements, but planning should have specifically addressed fraud and corruption risks in the given environments.

Manus Island

2.3 As outlined at paragraph 1.11, BRS, the incumbent garrison support and welfare services provider, advised in May 2016 that it would not participate in any further tenders or contracts for the supply of garrison support and welfare services to the Australian Government. It agreed to extend its existing contract until 31 October 2017.

2.4 It was agreed between the Australian and PNG governments that the latter would assume independent management of the delivery of services to existing asylum seekers from October 2017.

2.5 To that end, in June 2017 ICA issued ‘Requests for Offer’ (RFOs) to a number of potential service providers inviting them to tender for various aspects of garrison support and welfare services.

- Paladin — an Australian registered company who had been providing security at the East Lorengau Transit Centre (ELRTC) since late 2013, initially under Decmil during the planning/construction phase and then under Wilson Security during the BRS contract.

- TSI — a PNG provider who provided security under Wilson Security during the BRS contract.

- Loda — a PNG provider who provided security under Wilson Security during the BRS contract.

- C5 Crisis Management — an Australian registered provider of security training and consulting services who had previously provided services to ICA.

- Spic-n-span — a PNG provider who provided laundry services under the BRS contract.

2.6 The department was assisting ICA in the procurement process through departmental officers who had been embedded through the Strongim Gavman Program.35 The department also engaged KPMG to provide procurement advice to ICA.

2.7 During the procurement process, an election was called in PNG. The department’s records state that at a meeting on 5 July 2017 between ICA and departmental senior officers, the PNG State Solicitor advised that he had directed PNG officials not to enter into new contracts until after the election.

2.8 On 7 July 2017, the department’s First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division emailed the department’s Deputy Commissioner (Support):

It is proposed that DSD will take over all procurement processes, which were previously the responsibility of PNG ICSA. This will result in the Commonwealth having contracts with potential end dates beyond the 31 October 2017.

It is proposed that Paladin Group Ltd (Paladin) will be engaged to provide Garrison and Security Services and oversight at both sites. They will subcontract services to a number of local providers – including security providers TSI and Loda, Spic-n-span. In effect they will replace BRS.

These services will be the essential services required to promote the self-agency and safety of Residents and ensure the protection of assets for the Department.

2.9 Attached to the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division’s email was ‘a visual of how this would work’ (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Proposed garrison support and welfare contracts — Manus Island

Note: Procurement activity associated with health services is not considered within the definition of ‘garrison support and welfare services’, and was therefore not considered within the scope of this audit.

Source: Department of Home Affairs.

Selection of a procurement method

2.10 On 12 July 2017, the department submitted a brief requesting approval from the Minister to procure garrison support and welfare services for both Nauru and Manus Island in order to allow the continuation of these services after 31 October 2017. Approval was subsequently provided on 31 July 2017.

2.11 On 28 July 2017, the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division emailed the Deputy Commissioner (Support) attaching a document outlining three options for the procurement process, including a brief description of the risks, mitigations and benefits of each option. The document noted that the BRS garrison support and welfare contract would end on 31 October 2017 and that ‘[t]he Department has a limited timeframe to put in place contracts and transition a service provider to support Regional Processing in PNG.’ The procurement options presented in this context were:

- Option 1: Using the provisions of paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs;

- Option 2: The limited tender provisions of paragraph 10.3 of the CPRs; and

- Option 3: The ‘exemption’ provisions of the CPRs relating to procurements outside Australia (known as exemption 8).36

2.12 On 31 July 2017, the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division emailed a number of his staff stating:

I spoke with DCS on this today – she is minded to go for the first option 2.6.

Can we start constructing the approach around 2.6 – and mention the other options (and why we didn’t go with them).

2.13 The email from the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division did not include any explanation of, or reason for, the Deputy Commissioner’s (Support) preference. There was no other document that demonstrated how or why this approach was pursued.

2.14 On 10 August 2017, the Secretary, as the department’s accountable authority, approved the use of the paragraph 2.6 ‘special measures’ provisions of the CPRs. Notwithstanding the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division’s direction that the minute to the Secretary should refer to ‘the other options (and why we didn’t go with them)’, there is no reference to these in the minute, and no reference to why the department chose to use paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs rather than the other options shown at paragraph 2.11.

2.15 Paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs permits accountable authorities to determine ‘special measures’ for reasons including the protection of ‘essential security interests’ and ‘to protect human health’. The minute requesting the Secretary’s approval stated:

The MRPC Procurements will result in contracts that will secure essential services (security and accommodation) and critical infrastructure (minor works, sewerage, water, power) and health care. Without contracted service providers in place providing these services there is a high risk to human health and the maintenance of peace and security at the Manus Regional Processing Centre and other relevant Sites.

In addition, the reasons that were provided to the Secretary to justify the use of paragraph 2.6 were:

The complex operating environment in Papua New Guinea, which requires the engagement of particular service providers with the right service capability, experience and risk appetite, with short lead times.

Procurement processes that are flexible to respond to the changes in either the operating environment, service delivery requirements or the impact of external factors, that allows contracts to be established and implemented quickly.

2.16 The Secretary’s decision to invoke paragraph 2.6 in the terms that he did removed the requirement for the department to comply with the rules relating to encouraging competition (which are contained in Part 5 of the CPRs) and the requirement to comply with Division 2 (which imposes additional requirements). The minute noted that the department would still comply with the rules relating to:

- Value for money (CPRs Part 4);

- Efficient, effective, economical and ethical procurement (CPRs Part 6);

- Accountability and transparency in procurement (CPRs Part 7); and

- Procurement risk (CPRs Part 8).

2.17 While the minute to the Secretary broadly described the procurement process that would be followed, it did not provide information on who were preferred providers and why they were preferred.

Selection of providers for Manus Island

2.18 In addition to the providers referred to in the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division’s proposed model for garrison support and welfare services at Figure 2.1 (Paladin, Loda, TSI, and Spic-n-Span), the department was also aware of other providers. Specifically:

- the 28 July 2017 email (referred to at paragraph 2.10) outlining options for a procurement process also included a diagram which referred to JDA Wokman Ltd (JDA)37 and ‘Host’;

- as noted at paragraph 2.5, one of the companies to which ICA had issued an RFO during its procurement process was C5 Crisis Management; and

- in August 2016 and December 2016, the department had conducted a ‘market sounding’ exercise intended to identify and gauge interest in the provision of garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island and Nauru. As part of this process, Serco, Decmil and Canstruct38 had expressed interest in tendering for the supply of services, albeit with qualification.39

2.19 Another provider which ultimately became part of consideration in the procurement process was NKW Holdings Ltd (NKW). In May 2017, due to the decommissioning of the MIRPC (refer paragraph 1.4), the department was seeking accommodation on Manus Island to supplement the ELRTC. It became aware that NKW held a lease on land which had some existing barracks style accommodation, with the potential for further similar accommodation to be constructed. The department entered into a Letter of Intent on 8 September 2017 to refurbish the existing accommodation40 and to construct new accommodation.41

2.20 There were 11 providers42 of which the department was aware that could offer some or all elements of the required garrison support and welfare services. However, the department issued RFQs to only three potential providers. Paragraph 7.2 of the CPRs states that officials must accurately and concisely document ‘relevant decisions and the basis of those decisions’.43 The department did not document why Paladin, NKW and JDA were the only providers selected to receive RFQs.

2.21 Aside from the department’s expressed preference for a particular contracting model, at the time of issuing the RFQs, the department’s records included information on the following factors which may have influenced the decision as to which companies should be asked to quote:

- the performance, experience and track record of providers;

- the ability of providers to attract, retain and manage a workforce of largely local Manus Island residents; and

- the views of ICA, since novation of the management of contracts to ICA was likely.

2.22 In January 2020, the ANAO took evidence under oath from the First Assistant Secretary, Detention Services Division, under s.32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997, about whether there was ever any pressure brought to bear by the PNG government or officials to appoint one or all of Paladin, NKW or JDA. He replied:

Absolutely not. These were decisions that were made by the Commonwealth and officials in the Commonwealth. The delegations all sit within the Commonwealth, the decision-making, the evaluation, value for money, all of that, which you’ve got all of that documentation, all sat with Commonwealth officers and in the Department. So the PNG Government, either through its ministers, politicians or officials, had no part in our decision-making. It was all within the Commonwealth. Now, the policy context that we were operating in, they had some views around that and we were mindful of that, but they did not get directly involved in any of the procurement processes. It was all done by Commonwealth officials here in Australia.

Recommendation no.1

2.23 The Department of Home Affairs develop policy guidance to ensure that, where a limited tender procurement is undertaken, decisions in relation to the providers to receive requestions for quotation are accurately and concisely documented.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.24 The Department will develop policy guidance and update internal procurement procedures to meet this recommendation with a particular focus on highly sensitive, high value, and/or complex procurements.

Nauru

2.25 As noted at paragraph 2.3, in May 2016, BRS announced that it would not participate in any further tenders or contracts to supply garrison support and welfare services for the Australian Government, but agreed to extend its contract until 31 October 2017.

2.26 Following ‘market soundings’ in August and December 2016 which demonstrated that there was some interest in the market in participating in a procurement process, in January 2017, the department commenced preparations for an open tender process to replace BRS. However, the department stated that this process did not proceed due to concerns that it could prejudice discussions that were underway with the Government of Nauru.

2.27 In February 2017, BRS approached the department with a proposal that it novate its existing contract to Canstruct.44 The department held discussions with BRS and Canstruct in May 2017, but decided against this proposed course of action.

2.28 On 20 June 2017, the department’s Assistant Secretary, Services Management obtained approval from the CFO to conduct a procurement by limited tender to replace BRS using the provisions of paragraph 10.3(a)(i) of the CPRs, which permit a limited tender45 in circumstances where a previous approach to market did not result in a submission that represented value for money.

2.29 The provisions of paragraph 10.3 are shown in Appendix 2. In order to justify using paragraph 10.3(a)(i), the department needed to be able to show that in the earlier response to market, ‘no submissions that represented value for money were received’.

2.30 In 2015, the department had commenced a process for the procurement of garrison support and welfare services in both Manus Island and Nauru, which was cancelled in July 2016 (the 2016 limited tender process).46 The process was cancelled because two participating tenderers (BRS and Serco) withdrew: BRS withdrew after its takeover by Ferrovial; and Serco withdrew because of a disagreement with the department over a number of terms and conditions in the draft contract. On this basis, there were no submissions that represented value for money.47

2.31 On 29 June 2017, a detailed minute to the Deputy Commissioner (Support) outlined the various options (including risks and benefits) and sought agreement to proceed with a limited tender under paragraph 10.3(a)(i) by way of an RFQ to Canstruct. By this time, with only four months to go before BRS ceased providing services, a number of the ‘options’ presented to the Deputy Commissioner (such as conducting an open market procurement) were unrealistic.

2.32 On 1 August 2017, the Nauruan Government certified the Nauru (RPC) Corporation Act 2017. A brief to the Minister on 5 December 2017 stated:

On 1 August 2017, the Department was informed of the Nauru (RPC) Corporation Act 2017 when it was introduced into the Nauruan Parliament. This Act enabled the Corporation to administer, manage and facilitate commercial operations associated with regional processing.

The introduction of the Act meant that the Department could not continue the procurement process for a period of time immediately following this introduction, thereby delaying the process. The Department worked with the Government of Nauru to understand the intent and implications of the legislation. The Government of Nauru subsequently amended the legislation on 14 August 2017.

The amended Act now requires the Department to seek endorsement from the Nauruan Cabinet for any contract for the provision of Garrison and Welfare services at the Regional Processing Centre or Settlement sites in Nauru. The Department has complied with this requirement.

2.33 The department satisfied the requirements of paragraph 10.3(a)(i), however it had adequate time to plan for the procurement of garrison and welfare support services in Nauru in a manner which could have allowed a more competitive approach to the market. Notwithstanding the introduction of the Nauru (RPC) Corporation Act 2017, the department had 14 months between May 2016 — when BRS formally advised the department that it would cease operations on 31 October 2017 — and the certification of this legislation in August 2017, to explore a range of possible procurement options and suppliers.48

Procurement risk

2.34 The CPRs require that when conducting a procurement, entities must establish processes for the identification, analysis, allocation and treatment of risk. The department created a Risk Management Strategy and Plan for each of the four procurements.49 Three of the four plans had a risk assessment template50 which identified risks such as:

- services are not in place by 31 October 2017;

- lack of sufficient funds;

- inability to sign a contract with the service provider; and

- service provider unable to obtain necessary visas to deliver services.

2.35 In February 2019, the department conducted an internal audit of the Paladin procurement process. Among other findings, this audit noted that ‘the nature of the operating environment in PNG heightens the potential for fraud and corruption procurement risks’ and considered that such risks should have been identified and documented. The ANAO agrees that these risks should have been recorded. In responding to the internal audit’s finding, the department stated:

During the procurement process, no issues were identified in relation to fraud, corruption and/or collusion. [Property and Major Contracts Division] followed all procurement processes including conducting a risk assessment in relation to the procurement in compliance with the CPRs. Should issues have been identified, the procurement process would have explicitly addressed these concerns, and mitigations would have been put into place before any arrangement was entered into.

2.36 The purpose of a risk assessment is to anticipate and identify risks before they arise rather than to deal with them once they have.

Did the department ensure that principles of probity were applied?

The department developed a probity management framework but it was not effectively applied in all instances. Key declaration and acknowledgement forms were not completed by all applicable personnel.

2.37 Ethical behaviour is a key CPR principle. The 2017 CPRs stated:

Ethical relates to honesty, integrity, probity, diligence, fairness and consistency. Ethical behaviour identifies and manages conflicts of interests, and does not make improper use of an individual’s position.51

2.38 Department of Finance guidance52 states that external probity specialists should be appointed where justified by the nature of the procurement. The department engaged external probity advisors for all four procurements.53 The engagement of probity advisors was commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of these procurements.

2.39 The Probity Advisors prepared probity plans for delegate approval and prepared and delivered probity briefings to all staff involved in the procurement process. The probity plans for each procurement required all relevant staff to sign a conflict of interest declaration form at the commencement of the procurement, and review and update as necessary at key stages in the process. Staff were also required to acknowledge that they had read and understood the probity requirements by signing a probity acknowledgement form.

2.40 While probity planning was adequate, there were failures in execution. An internal audit report on the three PNG procurements54 conducted in August 2018 found that:

- the register of conflict of interest declaration and probity acknowledgement forms for the three procurements had not been maintained or completed;

- five key staff involved in the procurements had not completed either of the required forms; and

- 38 staff involved with the procurement had not completed a probity acknowledgement form.

2.41 The report recommended that the department update the conflict of interest and probity register to record and validate the completion of all relevant forms for all staff, including addressing any gaps. The department accepted the recommendation.

2.42 The ANAO’s examination of email traffic showed that the Director, Services Procurement engaged with JDA and NKW before and after their RFQs were lodged:

- prior to the lodgement of NKW’s RFQ, the Director, Services Procurement asked NKW whether it required ‘any further assistance with the RFQ response’; and

- the Director, Services Procurement met in Canberra with a representative of JDA after its RFQ was lodged, but before the assessment of the RFQ took place.

2.43 Subsequently, the same officer chaired the pricing assessment and technical evaluation teams for the procurement processes which recommended that JDA and NKW be awarded contracts. There was no evidence that details of these interactions and discussions — including what ‘assistance’ may have been given to NKW — were recorded as required by the Probity Plans for the procurements. To that extent, there may have been a breach of probity.

2.44 KPMG was engaged by the department as Commercial and Financial Advisors for the PNG procurements and also provided assistance to ICA during the conduct of its procurement processes for garrison services. One of the KPMG advisors was a key point of contact between ICA and the department. On 4 July 2017, after the department had preliminary discussions about approaching Paladin, a KPMG employee contacted Paladin on behalf of the department to discuss surge security required at the ELRTC. Along with its active involvement in conducting the procurements, KPMG was also engaged to conduct the department’s financial strength assessments for all four procurements.

2.45 In the period immediately following the establishment of the first letter of intent on 21 September 2017, Paladin commenced a process of engaging required personnel to support the commencement of operations. Departmental records showed that on 5 December 2017, Paladin advised the department that it was encountering difficulties in obtaining visas for workers, but that these difficulties could be resolved ‘via a payment from Paladin’, which it had refused to make. The department advised Paladin on the need to ensure that all activities were conducted in a manner which was consistent with Australian law.

Did the department demonstrate the achievement of value for money in Nauru?

The department demonstrated the achievement of value for money for the Nauru procurement. Costs under the most recent contract for services, and various scenarios based on population trends and service assumptions, were used to effectively benchmark tenderer costs. Negotiations resulted in the inclusion of additional services with a modified pricing impact.

2.46 A core principle of the CPRs is the achievement of value for money.55 Auditor-General Report No. 48 2014–15 Limited Tender Procurement56 noted that it is generally more difficult for entities conducting a limited tender to demonstrate value for money, but identified two activities that entities may undertake to increase the likelihood of achieving value for money in such situations: benchmarking costs for similar services procured previously; and negotiating strongly for discounted pricing or additional services rather than accepting initial quotes provided.57

2.47 This section examines whether the department:

- effectively benchmarked costs for similar services; and/or

- negotiated to receive discounted pricing and/or additional services.

Benchmarking of proposed costs — Nauru

2.48 In July 2017, the department, in consultation with its external financial advisor (KPMG), developed a baseline using actual service costs under the most recent BRS contract (for the period 1 May 2016 to 30 April 2017), adjusted for service differences and inflation.58

2.49 Using this baseline, three pricing benchmarks were then developed to account for different resident and refugee volumes and servicing assumptions (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Benchmarks for Nauru procurement

|

Benchmark model |

Benchmark value ($m) |

Cost based on Canstruct’s RFQ response ($m) |

|

Baseline — BRS actual costs 1 May 2016 to 30 April 2017 |

346.5 |

N/A |

|

Scenario 1a |

318.0 |

258.3 |

|

Scenario 2b |

301.7 |

242.5 |

|

Scenario 3c |

305.0 |

245.7 |

Note: All benchmark estimates excluded pass-through costs, and additional service requests as Canstruct was not required to provide an estimate of these costs in its RFQ response.

Note a: Scenario 1 — assumed April 2017 volumes of residents and refugees and associated cost bands would not change until 31 October 2018; and Level 1 Servicing Requirements for Settlement Support Services.59

Note b: Scenario 2 — as per scenario 1, however with Settlement Support Services delivered in accordance with Level 2 Servicing Requirements.

Note c: Scenario 3 — as per scenario 1, except RPC Additional Family Services cost bands would gradually decline over the contract term. As at April 2017, the bands for RPC refugees was already at the lowest possible band.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

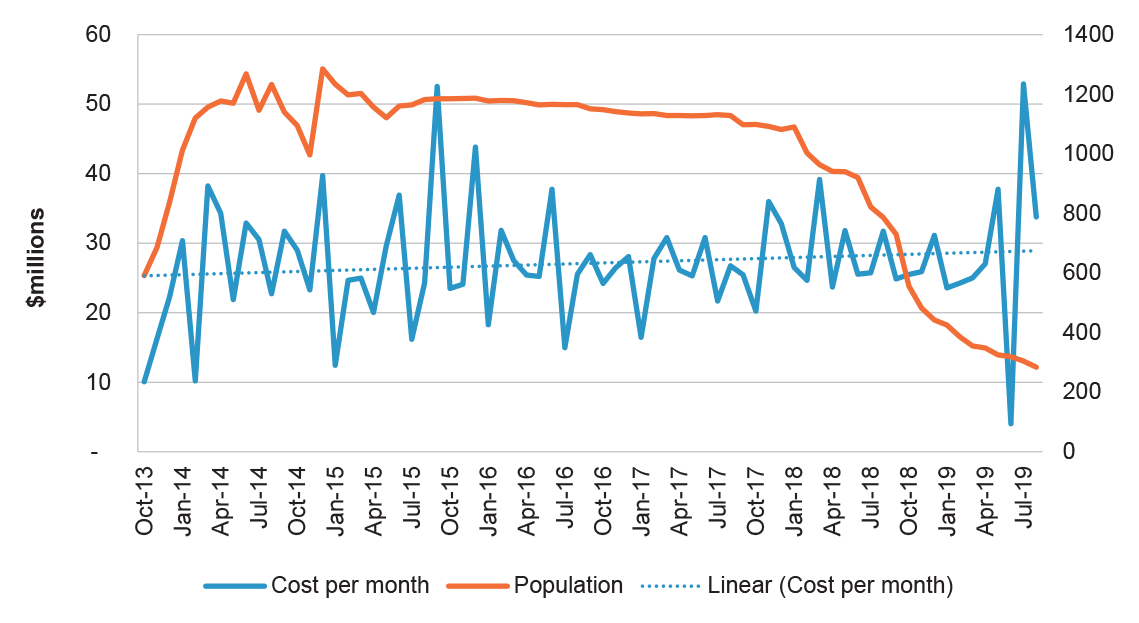

2.50 The three benchmarks used were based on previous trends and anticipated future scenarios. Figure 2.2 illustrates changes in population and service costs on Nauru from 2013 to 2019.

Figure 2.2: Changes in population and service costs on Nauru, 2013 to 2019

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.51 At the point in July 2017 when the department was undertaking its evaluation, the population at the Nauru RPC had decreased since mid-2014, however service costs had fluctuated. Since 2013 the service cost per month had gradually increased (as indicated by the trend line). However, departmental documentation noted:

The contract value is not expected to materially decrease if the number of refugees and non-refugees residing on Nauru declines. This is due to the fact that the fees for the bands between 0–200 and 201–400 are the same, reflecting the fixed cost of keeping baseline services operational on Nauru.60

2.52 The department did not estimate the cost per person. This would have enabled the department to benchmark against the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2015–16 (December 2015) estimate of $573,111 per person per annum. While this estimate was prepared in the context of the budget preparation process, in a situation where there are limited relevant benchmarks, a cost per person could have been a potential indicator of value for money.61

2.53 Noting this, the benchmarks used by the department were appropriate given that BRS’ actual costs in 2016–17 were based on the fee structure from its 2014 bid, which the ANAO had previously found to have been lower than historical costs for similar services at the Nauru RPC62 and the department applied the most recent resident and refugee volumes to develop a series of scenario benchmarks.

Impact of negotiations — Nauru

2.54 Following the assessment of Canstruct’s submission, on 3 October 2017, the delegate agreed and endorsed the report’s conclusion that Canstruct’s RFQ response be considered value for money. Negotiation processes were completed in the same month.

2.55 Table 2.2 summarises departmental contract value estimates at key steps in the procurement process for garrison and welfare services in Nauru.

Table 2.2: Departmental contract value estimates at key steps in the Nauru procurement

|

Source |

Value ($m) |

|

Department’s estimated cost of services |

332.0 |

|

Pre-negotiation cost based on Canstruct’s RFQ responsea |

258.3 |

|

Negotiated outcome |

260.2 |

|

Estimated overall contract value |

385.0 |

|

Actual costs 2018–19 |

301.2 |

Note a: Based on volumes under benchmark model scenario 1 (Table 2.1).

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.56 The basis of the estimated overall contract value ($385 million) was not documented. The department was unable to explain the reason for the difference between the negotiated outcome of $260.2 million and the estimated overall contract value.

2.57 While Canstruct’s bid increased by $1.9 million as a result of negotiations, the department assessed the negotiated outcome as continuing to represent value for money as it: was comparable to the expected cost of services (benchmark scenario 1); and incorporated into the scope of services a range of additional items in relation to transport, school lunches, infant care and asset maintenance with a modified pricing impact.

2.58 Notwithstanding approved contract estimates, the department’s actual expenditure under the contract in 2018–19 was $301.2 million.

Did the department demonstrate the achievement of value for money in PNG?

The department did not demonstrate the achievement of value for money for the PNG procurements. Although the department had limited options for comparing tenderer costs, most of the benchmarks it used were not appropriate. Negotiations with NKW achieved significant savings, noting that the initial tendered costs had been assessed as not representing value for money. The effectiveness of negotiation for Paladin was unclear as savings achieved for some items were offset by increases to others, the addition of a mobilisation payment and the department’s substantial expansion of the services required during the negotiation process.

Benchmarking of proposed costs — PNG

2.59 The department identified four benchmarks, which were used to varying degrees in the JDA, NKW and Paladin procurements respectively, as summarised in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Value for money benchmarks for PNG procurements

|

# |

Benchmark |

JDA |

NKW |

Paladina |

|

1 |

Existing BRS contract rates for garrison support and welfare services on Manus Island |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

2 |

RFT 28/14 open procurement tender responses |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

3 |

Actual cost of settlement support services in Nauru |

Y |

N/A |

N/A |

|

4 |

Paladin’s response to RFQ for garrison services at the ELRTC |

N/A |

Y |

N/A |

Note a: The Paladin pricing assessment team aggregated and averaged benchmarks one and two and applied an adjustment of 7.68 per cent for inflation to provide a single benchmark, referred to as the ‘indicative comparable fee’, and used this to assess Paladin’s RFQ response.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.60 Benchmark #1 was a comparison to the existing contract rates for garrison support and welfare services being provided by BRS. Whilst this was relevant, the 2014 BRS bid on which these contract rates were based exceeded historical costs by between $200 million and $300 million; and ‘…require[d] the Commonwealth to pay a significant premium over and above the historical costs of services’.63

2.61 Benchmark #2 was based on the daily fees quoted by four of the six respondents to the 2015 open market procurement (see paragraph 2.30). Whilst this benchmark was relevant given similarities in the scope of services tendered for, the 2015 procurement process was cancelled by the department on the grounds that it did not result ‘in any submissions that represented value for money.’

2.62 The appropriateness of benchmarks #1 and #2 were further impacted by changes in population and service costs in PNG since 2014 (Figure 2.3). The PNG regional processing population decreased by almost 50 per cent between January 2014 and October 2017, from 1353 to 690.

Figure 2.3: Changes in population and service costs in PNG, 2013 to 2019

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.63 While the population steadily decreased from early-2014 onwards, services costs have fluctuated significantly, peaking in October 2017, and the cost per month has gradually increased over the same period. Benchmark #3 was the actual cost of settlement support services being provided by Connect, a subcontractor to BRS in Nauru. This benchmark was applied only to the analysis of JDA’s pricing given that its scope of services was limited to settlement support, and that it was the incumbent provider for these services on Manus Island. This benchmark was therefore appropriate.

2.64 Benchmark #4 was Paladin’s response to the RFQ for the provision of garrison support and welfare services in August 2017. As NKW was tendering to provide similar services to Paladin at separate sites on Manus Island, this benchmark was applied only to the analysis of NKW’s pricing. This benchmark was therefore appropriate.

2.65 For the procurement of garrison services specifically (Paladin), the department also benchmarked a proposed 40 per cent margin on services against the Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortisation (EBITDA) margins of two similar organisations in the sector.64 Departmental documentation stated that these benchmarks were used as there was ‘no readily available information in respect of the contracts for services in regional processing countries’. However, the available record indicated that the department did not consider the following margin based benchmarks:

- the arrangement used by the department when RPCs were first established65; and

- the profit margin used for the Nauru procurement — the department estimated that Canstruct’s profit margin would be between $33 million and $50 million based on a service industry average profit margin of between 10 per cent and 15 per cent.

2.66 Whilst the department benchmarked against the existing contract rates for garrison support and welfare services being provided by BRS (refer paragraph 2.59), it did not benchmark against BRS’ actual costs for the provision of services on PNG (as it had for Nauru). While the department had changed the statement of requirement to include different sites and services, a comparison to actual costs would have presented a relevant benchmark, particularly given the limited options for comparing tenderer costs.

2.67 The department did not estimate the cost per person. This would have enabled the department to benchmark against the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2015–16 (December 2015) estimate of $573,111 per person per annum.

Impact of negotiations — PNG

2.68 The department conducted negotiations with each of the three tenderers. Table 2.4 compares BRS’ actual costs in 2016–17 for garrison and welfare services in PNG with departmental contract value estimates at key steps in the negotiation process for the three PNG tenderers. It also includes the actual cost of these services for 2018–19.

Table 2.4: Contract value estimates/outcomes at key steps in the PNG procurement

|

Provider |

$ millions |

||||

|

|

2016–17 actual costs |

Department's estimated cost of servicesa |

Pre-negotiation cost based on RFQ response |

Negotiated outcome |

2018–19 actual expenditure |

|

Broadspectrum PNG |

342.3 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

JDA |

N/A |

30.0 |

18.3b |

20.1 |

20.9 |

|

NKWc |

N/A |

86.0 |

120.2 |

66.0 |

102.7 |

|

Paladind |

N/A |

75.0 |

152.0 |

229.5 |

209.1 |

|

PNG total |

342.3 |

191.0 |

290.5 |

315.6 |

332.7 |

Note a: Estimated cost of services from procurement spending proposals.

Note b: JDA had requested that all invoices be paid in PNG Kina (PGK). This would add 10 per cent for PNG goods and services tax to each invoice, increasing the RFQ response to $20.1 million.

Note c: The contract between the department and NKW was executed on 21 September 2018. There was no contract with NKW to provide site management and related services before this.

Note d: The department expanded the scope of services after it issued the RFQ.

Source. ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.69 The department only assessed value for money on an individual procurement basis. It did not evaluate value for money based on the combined estimated contract values. Whilst a number of factors had changed in relation to the nature of services required and in the operational environment since the previous provider (BRS) were engaged66, given BRS was responsible for all three combined services, an examination of the combined estimated contract values would have allowed a level of benchmarking.

JDA

2.70 The department concluded that the cost ‘was reasonable and less than expected’ and JDA’s response represented value for money. In relation to the lower than expected price, the department acknowledged that this may have reflected JDA not fully understanding some contract requirements, such as reporting.

2.71 On 20 December 2017, the delegate’s approval of negotiation outcomes was sought. The delegate directed the department enter into a Letter of Intent with JDA.67

NKW

2.72 The department determined at the tender evaluation stage that NKW’s RFQ response was not value for money. It identified a number of matters for negotiation, including removing out of scope items, and seeking pricing reductions in three priority areas — the profit margin applied to staff rates, the personnel costings (assumed work days and hours), and removal of duplication in the overhead rate.

2.73 As a result of negotiations, the parties agreed to a revised contract value of $65.9 million, representing an overall reduction of $35.8 million (see Table 2.5).68

Table 2.5: Negotiated pricing outcomes — NKW

|

Fee component |

RFQ pricing response ($m) |

Negotiated price ($m) |

Difference ($m) |

|

1. Site management fee — Hillside Haus |

13.2 |

12.5 |

0.7 |

|

2. Site management fee — West Lorengau Haus |

21.4 |

12.2 |

9.2 |

|

3. Overhead Fee |

50.8 |

31.1 |

19.7 |

|

4. Catering |

11.8 |

5.6 |

6.2 |

|

5. Transition-in Fee |

4.5 |

4.5 |

0 |

|

6. Total (excluding PNG Sales tax) |

101.7 |

65.9 |

35.8 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.74 Notwithstanding the discounted pricing achieved by the department, total actual expenditure for site management services was $102.7 million in 2018–19 which was slightly more than NKW’s original pricing response.).

Paladin

2.75 While the department determined at the tender evaluation stage that Paladin’s RFQ response represented value for money, it assessed the response as at the ‘higher end of the range’ when compared against agreed benchmarks (Table 2.3).69 It also identified a number of matters for negotiation, including Paladin’s proposed 40 per cent margin on services70 and its organisational structure.71 It was identified that some concerns would be mitigated by Paladin’s ‘proposed efficiency measures and potential reduction in price following Transition-In (through an appropriate mechanism agreed during negotiations)’.