Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Implementation and Performance of the Cashless Debit Card Trial

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the Department of Social Services’ (Social Services) implementation and evaluation of the Cashless Debit Card trial.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Welfare quarantining, in the form of income management, was first introduced in 2007 as part of the Australian Government’s Northern Territory National Emergency Response.1 The aim of income management is to assist income support recipients to manage their fortnightly payments — such as Newstart/Youth Allowance, parenting or carer payments, and the Disability Support Pension — for essentials like food, rent and bills.2

2. On 1 December 2014, the Government agreed to trial a new approach to income management — the Cashless Debit Card (CDC), in Ceduna and the East Kimberley. The Cashless Debit Card Trial (CDCT or the trial) aimed to: test whether social harm caused by alcohol, gambling and drug misuse can be reduced by placing a portion (up to 80 per cent) of a participant’s income support payment onto a card that cannot be used to buy alcohol or gambling products or to withdraw cash; and inform the development of a lower cost welfare quarantining solution to replace current income management arrangements.

3. On 14 March 2017, the Minister for Human Services and the Minister for Social Services announced the extension of the trial in Ceduna and the East Kimberley for a further 12 months. In addition, funding was allocated as part of the 2017–18 Budget to trial the CDC in two new locations with the Government announcing in September 2017 that the CDC would be delivered to the Goldfields region of Western Australia and also to the Hinkler Electorate (Bundaberg and Hervey Bay Region) in Queensland.3 Subsequently, the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Cashless Debit Card) Act 2018 received royal assent on 20 February 2018. The amendments restricted the expansion of the CDC, with the cashless welfare arrangements continuing to 30 June 2019 in the current trial areas of East Kimberley and Ceduna, with one new trial site in the Goldfields.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Recent ANAO audits have highlighted the need for entities to articulate mechanisms to determine whether an innovation is successful and what can be learned to inform decision making regarding scaling up the implementation of that innovation. The CDCT was selected for audit to identify whether the Department of Social Services (Social Services) was well placed to inform any further roll-out of the CDC with a robust evidence base. Further, the audit aimed to provide assurance that Social Services had established a solid foundation to implement the trial including: consultation and communication with the communities involved; governance arrangements; the management of risks; and robust procurement arrangements.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the Department of Social Services’ implementation and evaluation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial.

6. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Appropriate arrangements were established to support the implementation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial.

- The performance of the Cashless Debit Card Trial was adequately monitored, evaluated and reported on, including to the Minister for Social Services.

Audit methodology

7. The audit methodology included:

- examining and analysing documentation relating to the implementation, risk management, monitoring and evaluation for the Cashless Debit Card Trial; and

- interviews with key officials in the departments of Social Services and Prime Minister and Cabinet and with external stakeholders including Indue Limited (Indue), ORIMA Research (ORIMA), Community Leaders, Local Partners and others in the trial sites.

Conclusion

8. The Department of Social Services largely established appropriate arrangements to implement the Cashless Debit Card Trial, however, its approach to monitoring and evaluation was inadequate. As a consequence, it is difficult to conclude whether there had been a reduction in social harm and whether the card was a lower cost welfare quarantining approach.

9. Social Services established appropriate arrangements for consultation, communicating with communities and for governance of the implementation of CDCT. Social Services was responsive to operational issues as they arose during the trial. However, it did not actively monitor risks identified in risk plans and there were deficiencies in elements of the procurement processes.

10. Arrangements to monitor and evaluate the trial were in place although key activities were not undertaken or fully effective, and the level of unrestricted cash available in the community was not effectively monitored. Social Services established relevant and mostly reliable key performance indicators, but they did not cover some operational aspects of the trial such as efficiency, including cost. There was a lack of robustness in data collection and the department’s evaluation did not make use of all available administrative data to measure the impact of the trial including any change in social harm. Aspects of the proposed wider roll-out of the CDC were informed by learnings from the trial, but the trial was not designed to test the scalability of the CDC and there was no plan in place to undertake further evaluation.

Supporting findings

Implementation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial

11. Social Services conducted an extensive consultation process with industry and stakeholders in the trial sites. A communication strategy was developed and implemented which was largely effective, although Social Services identified areas for improvement in future rollouts.

12. There were appropriate governance arrangements in place with clearly defined roles and responsibilities across key departments and stakeholders for reporting and oversight of the CDCT.

13. Social Services demonstrated an integrated approach to risk management across the department linking enterprise, program and site-specific risk plans. While a CDCT program risk register was developed, the identified risks were not actively managed, some risks were not rated in accordance with the Risk Management Framework, there was inadequate reporting of risks and some key risks were not adequately addressed by the controls or treatments identified. In particular, treatments were inadequate to address evaluation data and methodology risks that were ultimately realised. Social Services managed and effectively addressed operational issues as they arose.

14. Aspects of the procurement process to engage the card provider and evaluator were not robust. The department did not document a value for money assessment for the card provider’s IT build tender or assess all evaluators’ tenders completely and consistently.

15. Social Services effectively established or facilitated arrangements to deliver local support to CDCT communities, although there were delays in the deployment of additional support services. As part of the CDCT, Social Services also trialled Community Panels and reviewed their effectiveness to inform broader implementation.

Performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting

16. A strategy to monitor and analyse the CDCT was developed and approved by the Minister. However, Social Services did not complete all the activities identified in the strategy (including the cost-benefit analysis) and did not undertake a post-implementation review of the CDCT despite its own guidance and its advice to the Minister that it would do a review. There was scope for Social Services to more closely monitor vulnerable participants who may participate in social harm and their access to cash.

17. Key performance indicators (KPIs) developed to measure the performance of the trial were relevant, mostly reliable but not complete because they focused on evaluating only the effectiveness of the trial based on its outcomes and did not include the operational and efficiency aspects of the trial. There was no review of the KPIs during the trial and KPIs have not been established for the extension of the CDC.

18. Social Services developed high level guidance to support its approach to evaluation, but the guidance was not fully operationalised. Social Services did not build evaluation into the CDCT design, nor did they collaborate and coordinate data collection to ensure an adequate baseline to measure the impact of the trial, including any change in social harm.

19. Social Services regularly reported on aspects of the performance of the CDCT to the Minister but the evidence base supporting some of its advice was lacking. Social Services advised the Minister, after the conclusion of the 12 month trial, that ORIMA’s costs were greater than originally contracted and ORIMA did not use all relevant data to measure the impact of the trial, despite this being part of the agreed Evaluation Framework.

20. Social Services undertook a review and reported to the Minister on a number of key lessons learned from the 12 month trial of the CDC. Learnings about the effectiveness of the Community Panels were based on the number of applications received and delays in decision making, rather than from the evaluation findings that noted a delay in the establishment of the Community Panels and a lack of communication with participants. The 12 month trial did not test the scalability of the CDC but tested a limited number of policy parameters identified in the development of the CDC. Many of the findings from the trial were specific to the cohort (predominantly indigenous) and remote location, and there was no plan in place to continue to evaluate the CDC to test its roll-out in other settings.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.20

Social Services should confirm risks are rated according to its Risk Management Framework and ensure mitigation strategies and treatments are appropriate and regularly reviewed.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.31

Social Services should employ appropriate contract management practices to ensure service level agreements and contract requirements are reviewed on a timely basis.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 2.36

Social Services should ensure a consistent and transparent approach when assessing tenders and fully document its decisions.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 3.14

Social Services should undertake a cost-benefit analysis and a post-implementation review of the trial to inform the extension and further roll-out of the CDC.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 3.47

Social Services should fully utilise all available data to measure performance, review its arrangements for monitoring, evaluation and collaboration between its evaluation and line areas, and build evaluation capability within the department to facilitate the effective review of evaluation methodology and the development of performance indicators.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 3.69

Social Services should continue to monitor and evaluate the extension of the Cashless Debit Card in Ceduna, East Kimberley and any future locations to inform design and implementation.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

Summary of the Department of Social Services’ response

21. The Department of Social Services was provided with a copy of the proposed audit report for comment. A summary of the department’s response is below and the full response is at Appendix 1.

The Department of Social Services (the department) welcomes the ANAO’s conclusions and agrees with the six recommendations. The department notes there are a number of areas it needs to focus on including in relation to Risk Management, contract management arrangements and utilising available data to measure performance.

22. An extract of the proposed report was provided to the organisations mentioned in the proposed report: Indue Limited; ORIMA Research; Boston Consulting Group; Maddocks; Clayton Utz; Deloitte Access Economics; and Colmar Brunton.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings and areas for improvement identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Australian Government entities when trialling new initiatives and designing, implementing and evaluating programs.

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Welfare quarantining, in the form of income management, was first introduced in 2007 as part of the Australian Government’s Northern Territory National Emergency Response.4 The aim of income management is to assist income support recipients manage their fortnightly payments — such as Newstart/Youth Allowance, parenting or carer payments, and the Disability Support Pension — for essentials like food, rent and bills.5

1.2 Income management is targeted towards specific groups, ‘based upon their higher risks of social isolation and disengagement, poor financial literacy, and participation in risky behaviours’.6 Subsequent to its introduction in the Northern Territory, income management has been implemented in other locations in Australia, including the East Kimberley (2008) and Ceduna (2014) with more than 25 000 people subject to income management as at 29 December 2017.

The Cashless Debit Card Trial

1.3 On 1 December 2014, the Government agreed to trial a new approach to income management — the Cashless Debit Card (CDC).7 The Cashless Debit Card Trial (CDCT or the trial) aimed to:

- test whether social harm caused by alcohol, gambling and drug misuse can be reduced by placing a portion of a participant’s income support payment onto a card that cannot be used to buy alcohol or gambling products (such as poker machines, but not including lottery tickets), or to withdraw cash; and

- inform the development of a lower cost welfare quarantining solution to replace current income management arrangements.

1.4 The card’s design was informed by existing income management trials and the Forrest Review: Creating Parity8 report which recommended the introduction of a Healthy Welfare Card to support welfare recipients to: manage their income and expenses; save for large purchases; and invest welfare income in a healthy life.9

1.5 The parameters that were tested during the CDCT included: the delivery of welfare quarantining by restricting 80 per cent of income support payments into a commercially provided debit card account; the use of contracted Local Partners; and establishing Community Panels that were authorised to make some administrative decisions.10 The CDCT was co-designed, with input from community leaders and the wider community during its development.

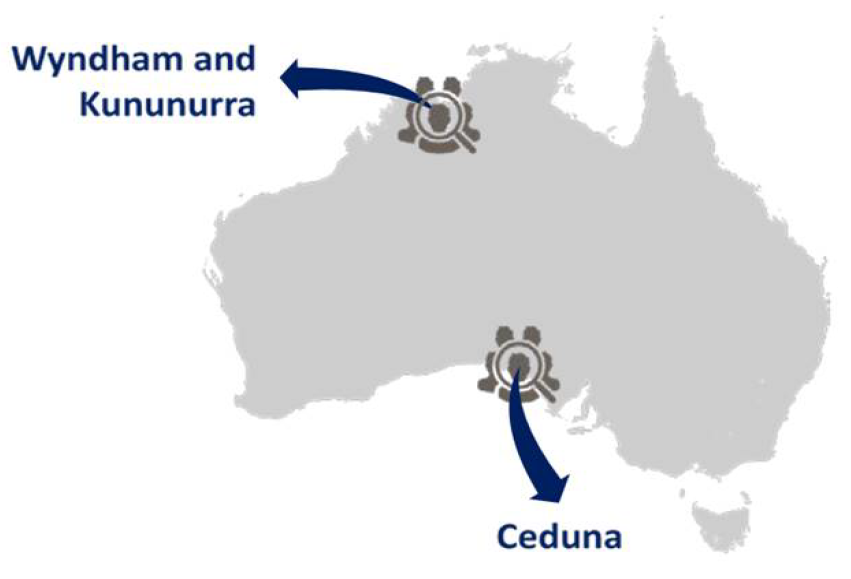

1.6 The CDCT was conducted in two locations (see Figure 1.1) for 12 months, commencing on:

- 15 March 2016 in Ceduna and surrounding areas — Koonibba, Oak Valley, Penong, Scotdesco, Smoky Bay, Thevenard and Yalata — in South Australia; and

- 26 April 2016 in the East Kimberley region — Kununurra and Wyndham — in Western Australia.

Figure 1.1: Cashless Debit Card Trial locations

Source: ORIMA Research documentation.

1.7 The two sites were selected for the CDCT following consultation and support from the identified community leaders. Income management measures had been in place at both sites prior to implementation of the CDCT, with the majority of those on income management in these sites being voluntary participants. Key aspects of the existing income management model and the CDCT model are compared in Appendix 3.

1.8 The trial sites had populations of 4110 and 5139 in Ceduna and the East Kimberley respectively and both were geographically remote.11 Within these populations, there were 783 CDCT participants in Ceduna and 1320 CDCT participants in the East Kimberley as at 31 March 2017. Around 30 per cent of the population in the trial sites identified as Indigenous Australians (compared to fewer than three per cent of the total population) with Indigenous participants making up more than three-quarters of all CDCT participants (77 per cent of participants in Ceduna and 81 per cent of participants in the East Kimberley).

1.9 The CDCT was administered by the Department of Social Services (Social Services) with support from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the Department of Human Services (Human Services). In addition, the Social Services contracted:

- Indue Limited (Indue) to deliver the IT build, Cashless Debit Card, banking services and local support for the CDCT; and

- ORIMA Research (ORIMA) to undertake an evaluation of the CDCT. ORIMA’s Wave 1 Interim Evaluation Report was completed in February 2017 and the Cashless Debit Card Trial Evaluation: Final Evaluation Report (CDCT final evaluation report) was completed in August 2017, and released to the public in March 2017 and September 2017 respectively.

1.10 A timeline of key events in the development and implementation of the CDCT is at Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Timeline of key events

Source: ANAO analysis of Social Services’ documentation.

Cost of the Cashless Debit Card Trial

1.11 The total cost of the 12 month trial including implementation costs was approximately $18.3 million. A breakdown of costs associated with the delivery of the CDCT are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Cost of the Cashless Debit Card Triala

|

|

2015–16 $m |

2016–17 $m |

2017–18 $m |

Total $m |

|

Human Services |

3.427 |

1.273 |

0 |

4.700 |

|

Social Services |

0.825 |

1.785 |

0 |

2.610 |

|

Indue |

5.823 |

3.063 |

0 |

8.886 |

|

Other contractors |

0.907 |

1.049 |

0.149 |

2.105 |

|

Totalb |

10.982 |

7.170 |

0.149 |

18.301 |

Note a: Costs are calculated on an accrual basis, that is, costs are calculated according to when the service was received, not when payment was made.

Note b: CDC related costs excluded from this total are the support services provided to both trial sites of $1.0 million for Ceduna and $1.6 million for the East Kimberley region and $240,000 paid to Boston Consulting Group which was contracted to provide advice on the initial development of the CDCT.

Source: ANAO analysis of Social Services’ documentation.

1.12 On 14 March 2017, the Minister for Human Services and the Minister for Social Services announced the extension of the trial in both sites for a further 12 months. In addition, funding was allocated as part of the 2017–18 Budget to trial the CDC in two new locations with the Government announcing in September 2017 that the CDC would be delivered to the Goldfields region of Western Australia and also to the Hinkler Electorate (Bundaberg and Hervey Bay Region) in Queensland.12 Subsequently, the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Cashless Debit Card) Act 2018 received royal assent on 20 February 2018. The amendments restricted the expansion of the CDC, with the cashless welfare arrangements continuing to 30 June 2019 in the current trial areas of East Kimberley and Ceduna, with one new trial site in the Goldfields.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.13 Recent ANAO audits13 have highlighted the need for entities to articulate mechanisms to determine whether an innovation is successful and what can be learned to inform decision making regarding scaling up the implementation of that innovation. The CDCT was selected for audit to identify whether the Department of Social Services (Social Services) was well placed to inform any further roll-out of the CDC with a robust evidence base. Further, the audit aimed to provide assurance that Social Services had established a solid foundation to implement the trial including: consultation and communication with the communities involved; governance arrangements; the management of risks; and robust procurement arrangements.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.14 The objective of the audit was to assess the Department of Social Services’ implementation and evaluation of the CDCT.

1.15 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Appropriate arrangements were established to support the implementation of the CDCT.

- The performance of the CDCT was adequately monitored, evaluated and reported on, including to the Minister for Social Services.

Audit methodology

1.16 The audit methodology included:

- examining and analysing documentation relating to the implementation, risk management, monitoring and evaluation for the CDCT; and

- interviews with key officials in the departments of Social Services and Prime Minister and Cabinet and with external stakeholders including Indue, ORIMA, Community Leaders, Local Partners14 and others in the trial sites.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $483,000.

1.18 Team members for this audit were Sandra Dandie, Judy Jensen, Michael Jones and Sally Ramsey.

2. Implementation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial

Areas examined

This chapter examined whether Social Services established appropriate arrangements to support the implementation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial (CDCT) including for: consultation and communication; governance; risk management; procurement; and supporting local communities.

Conclusion

Social Services established appropriate arrangements for consultation, communicating with communities and for governance of the implementation of CDCT. Social Services was responsive to operational issues as they arose during the trial. However, it did not actively monitor risks identified in risk plans and there were deficiencies in elements of the procurement processes.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving risk management practices, contract management and procurement processes.

Was there appropriate consultation and an effective communication strategy implemented?

Social Services conducted an extensive consultation process with industry and stakeholders in the trial sites. A communication strategy was developed and implemented which was largely effective, although Social Services identified areas for improvement in future rollouts.

2.1 Social Services began communications planning well in advance of the Cashless Debit Card Trial (CDCT) commencement. Consultations with the banking and retail sectors began in late 2014, and initial implementation plans were developed and approved in January 2015. In December 2015, an Overarching Communication Strategy was prepared by Social Services in consultation with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

2.2 There was considerable consultation and engagement with stakeholders15, including with indigenous community leaders prior to the commencement of the CDCT. Community leaders in the Ceduna area and East Kimberley supported trialling the Cashless Debit Card (CDC) in their communities and were actively involved in many CDCT decisions, including the decision to set the quarantined portion of a participant’s income support at 80 per cent.

2.3 To support the implementation of the trial, Social Services documented timelines and activities in site specific implementation plans including advertising campaigns, the distribution of communication materials and ‘engaging the community’ activities such as workshops and BBQs in the months leading up to the trial starting.

2.4 The card provider, Indue Limited (Indue), had representatives based in the trial site locations for four weeks at the start of the trial, supplemented by officials from Social Services and PM&C for the trial period. Local Partners16 and Financial Wellbeing and Capability program providers (for example, Centacare in Ceduna and Wunan in the East Kimberley) provided participants with ongoing support, information and assistance, including, for example, to activate and setup their online accounts. Commencement of the CDCT was supported by advertising — print, radio (in language and in English) and social media channels — as well as communications through factsheets, posters, Question & Answer sheets, letters to trial participants, info-graphic posters, and local media engagement.

2.5 Despite these efforts, Social Services acknowledged that communications to participants for future rollouts could be improved. Local Partners advised ANAO that participants required more face-to-face information from knowledgeable staff and support, as many had not attended the public meetings or asked questions and there was some confusion and misinformation among participants.

Were there appropriate governance arrangements in place with clearly defined roles and responsibilities to oversight the Cashless Debit Card Trial?

There were appropriate governance arrangements in place with clearly defined roles and responsibilities across key departments and stakeholders for reporting and oversight of the CDCT.

2.6 Management of the delivery of the CDCT was supported by appropriate governance arrangements that clearly outlined the roles and responsibilities of Australian Government departments — Social Services, PM&C and the Department of Human Services (Human Services). The governance groups, as they evolved, are depicted in Figure 2.1 (on the following page).

2.7 Social Services was responsible for: coordinating governance arrangements for the CDCT and for CDC policy; administration; and delivery of the CDCT. Social Services’ responsibilities involved: implementation oversight; community and stakeholder engagement strategy; CDC Hotline17; trial logistics; risk and issue management; card provider procurement and contract management; and monitoring and evaluation of the trial. Social Services’ state offices were responsible for managing agreements with relevant support services, and supporting engagement and data requests with state governments and other organisations.

2.8 Delivery of the CDCT was supported by PM&C’s National Office and Regional Network Offices in Ceduna and the East Kimberley. In particular, PM&C provided on-the-ground support with community and leader engagement, and managing and providing data on its funded support services.

Figure 2.1: Governance arrangements underpinning delivery of the Cashless Debit Card Trial

Note a: The New Welfare Card (NWC) Steering Committee provided high-level policy and implementation advice for planning and the co-design process. They were responsible for agreeing the rolling brief prior to it being submitted to Ministers, oversighting the risk and issues registers, and monitoring project progress.

Note b: The New Welfare Card Inter-Departmental Committee (NWC IDC) comprised Deputy Secretaries from Social Services, Human Services and PM&C and provided strategic direction, including overseeing risk management arrangements.

Note c: The New Welfare Card Working Group members were executive level staff with the working group providing a forum for information sharing, and discussing risks and issues. The Working Group would escalate issues to the NWC IDC where necessary.

Note d: The Steering Committee provided guidance and oversight; and had a key role in discussing policy, legal aspects, administration, budget, and risk management.

Note e: The Project Board had responsibility for coordinating, disseminating, tasking, tracking and monitoring implementation progress, and guiding cross-departmental issues. This body merged with the Steering Committee in June 2016 and retained the name, Project Board.

Source: ANAO analysis of Social Services’ documentation, including terms of reference documents.

2.9 Human Services was responsible for providing technological advice and support, including: administration of payments; placing eligible participants onto the trial; exemption processing; applying quarantined percentages; delivery of a customer service centre18; and providing support to participants regarding their payments.

2.10 Social Services built on its existing high level arrangements with PM&C and Human Services regarding interdepartmental relationships and responsibilities to provide decision making and oversight across the CDCT with roles and responsibilities outlined and updated when required. In addition, the following governance arrangements were also established to support the CDCT, including:

- interdepartmental steering committees and boards;

- project meetings held between Social Services and Human Services to monitor trial implementation, issue management and service delivery;

- local governance arrangements (as outlined in Figure 2.1) and the Community Panels; and

- an Evaluation Steering Committee.

2.11 The operation of these governance arrangements is discussed further in this chapter and in Chapter 3.

Were there fit-for-purpose risk management arrangements in place and were they actively managed?

Social Services demonstrated an integrated approach to risk management across the department linking enterprise, program and site-specific risk plans. While a CDCT program risk register was developed, the identified risks were not actively managed, some risks were not rated in accordance with the Risk Management Framework, there was inadequate reporting of risks and some key risks were not adequately addressed by the controls or treatments identified. In particular, treatments were inadequate to address evaluation data and methodology risks that were ultimately realised. Social Services managed and effectively addressed operational issues as they arose.

2.12 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy defines risk as ‘the effect of uncertainty on objectives’ and risk management as the ‘coordinated activities to direct and control an organisation with regard to risk’.19 Social Services’ risk management practices were supported by a centralised area that provided guidance and a framework to support enterprise, group and program level risk plans. Risks were identified and documented in a register for the CDCT from early 2015. In June 2015, the risk register was circulated for feedback to PM&C, Human Services, and the Departments of Finance, Communications and the Treasury, and discussed at the New Welfare Card (NWC) Working Group (previously the NWC Steering Committee). Pre-trial issues and decisions were logged and this formed the basis of the issues register maintained by Social Services, covering policy and operational issues, and incident management.

Risk management

2.13 Responsibility for managing the risk register was not visible as a task within the CDCT team structure.20 Risk registers were updated with additional risks during the trial period, although for the risks previously identified the descriptions, status, controls and treatments were not updated and information was not complete. For example, at the end of the trial the risk of ‘legislation doesn’t pass’, with a treatment of ‘review…August 2015’ had not been updated and was still open — this risk should have been closed in November 2015.21

2.14 All interdepartmental Steering Committees included risk management in their terms of reference. The NWC Steering Committee initially received a summary of risks in a ‘rolling brief’ report. The final rolling brief was presented in February 2015 and there was no systematic reporting of risks to the subsequently formed Project Board to support them to oversee risk management during the trial period.

2.15 Risks were reported internally to the Executive Management Group in the Project Status Reports throughout the entire trial period. However, this reporting was based on risk registers that were incomplete. Some of the risks being reported on were not identified in the risk register and Social Services’ Risk Management Framework for rating risks had not been correctly applied to the risks22 resulting in high risks not being flagged. There were six risks rated as medium risk whereas the risk matrix indicates that they should have been rated high. The risks that were rated as medium, instead of high (as per the ‘Risk Register December 2016–February 2017’ used for the ‘Project Status Report December 2016–February 2017’, which reported there were no high rated risks) were:

- critical incident by a trial participant attributed to the trial;

- circumventions by trial participants;

- legislation not passing;

- Human Services unable to complete the IT build in time;

- trial policy in relation to credit cards leads to: participants with credit card debt being unable to make re-payments; and participants being restricted from getting a credit card from mainstream banking institutions due to the trial restrictions; and

- aged pensioners being harassed for cash.

2.16 Controls did not fully address the identified risks, and treatments were also inadequate. For example, the risk that ‘trial objectives and impacts are not measured through effective evaluation process’ was identified as a risk in the risk register and a separate risk register was drafted for the evaluation of the trial in October 2015.

2.17 The November 2015 version of the evaluation risk register included the risks of ‘Data provided by state governments not sufficient to analyse appropriate variables’ and ‘Method and analytic approach not appropriate for purpose’. Risks were assigned to the Evaluation Unit and/or the Welfare Debit Card Taskforce, but were not updated subsequently. Further, there were errors in applying risk ratings to risks identified in the evaluation risk register, the treatments were not complete (predominately ‘ongoing review’), and there were no further updates or apparent active management of the risks identified. The lack of active management and ineffective treatments contributed to the data and methodology issues encountered with the evaluation process (discussed further in Chapter 3).

2.18 Indue was required to prepare a risk register and provide Social Services with an extract of all risks specific to the CDCT by 15 April 2016 according to the contract, but Indue did not do this during the trial period.23 Social Services was not formally monitoring Indue-related risks, reporting these risks to the Executive, and ensuring post-incident treatments were reflected in its register. For example, additional controls identified after a data incident were not reflected in Social Services’ risk register — including acknowledging additional treatments and the likelihood of reoccurrence, and it was not included in the Project Status Report to the Executive. The incident was appropriately handled by Indue and Social Services and documented as per the incident management process and in the issues register.

Issue management

2.19 Issues24 were regularly reported to the Steering Committees. Responsibility for issue management was clearly assigned within the CDCT team. Issues were documented in the issues register and in the Joint Issues Register (jointly managed with Indue), regularly updated, and effectively managed throughout the trial period.

Recommendation no.1

2.20 Social Services should confirm risks are rated according to its Risk Management Framework and ensure mitigation strategies and treatments are appropriate and regularly reviewed.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

2.21 The department agrees with the recommendation and will improve its application of the Risk Management Framework.

Were procurement processes to engage a card provider and evaluator robust?

Aspects of the procurement process to engage the card provider and evaluator were not robust. The department did not document a value for money assessment for the card provider’s IT build tender or assess all evaluators’ tenders completely and consistently.

Procurement of a card provider

2.22 In early 2015, Social Services discussed the proposed CDC with representatives from the four major banks (Westpac, National Australia Bank, Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited, and Commonwealth Bank) and the BasicsCard provider, Indue. Written submissions provided by the banks indicated that a rules-based approach, including merchant code blocking, (as opposed to a technology based approach25) was possible and there was a mixed response regarding interest in participating in the trial.

2.23 In early March 2015, Social Services undertook an internal desktop review of 18 financial institutions to rate potential card providers for the trial. Only four of these were Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs). Social Services advised the ANAO that the major banks ‘… were not interested in delivering a small scale trial of the nature of the CDC’. The institutions selected for review were rated against nine selection criteria. The criteria included whether the institution was an ADI and had previous experience with delivering welfare quarantining programs.26 Social Services did not contact the institutions to verify information, capabilities or interest in the trial.

2.24 Through this desktop review, Indue was identified as the preferred provider as it was the only institution to meet all the criteria. Subsequently:

- Ministerial approval to directly source Indue27 was sought and granted on 16 March 2015; and

- Social Services and PM&C began consultations with lndue on 19 March 2015.

2.25 To assist it with the procurement process, Social Services contracted: Boston Consulting Group for commercial and technical advice — including providing preliminary estimates of the expected total costs of the IT build and operation, which were consistent with Indue’s initial quote (around five million dollars compared to the final cost of nine million dollars) and analysis to assist with the initial assessment of Indue’s tender; Maddocks as the probity advisor28; and Clayton Utz for legal advice.

2.26 Indue’s tender was evaluated in accordance with departmental procurement processes with the evaluation undertaken by a six member panel comprised of officials from Social Services, PM&C, Human Services and the Department of Finance. It was noted in the Evaluation Report that a value for money assessment (as required by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules) would be conducted prior to finalisation of the contract. Social Services subsequently issued: two contracts, separating the IT build and the Implementation and Operational phases; and a letter of agreement.29

2.27 The approval for the:

- IT build contract with Indue was not supported by a documented value for money assessment, although it referenced the cost modelling work performed by Boston Consulting Group30; and

- Implementation and Operational phase contract31 with Indue did encompass a value for money assessment, including analysis of pricing components and comparisons with industry standards.

Contract management

2.28 Social Services did not develop a Contract Management Plan to assist in the management of the Indue service agreement — as per its departmental contract management guidance and recommended by its legal adviser — until after the trial period ended.

2.29 The contracts with Indue did specify roles and responsibilities including: the IT build and the delivery of local support (including its CDCT specific Customer Service Centre32 and Local Partners); arrangements with merchants33; Indue’s involvement in steering committee meetings, progress reporting requirements, and risk and incident management procedures. In addition, the contract required Indue to regularly provide two reports to Social Services, the:

- Trial Outcomes Monthly Report34 (one for each trial site); and

- Trial Outcomes Service Level Agreements (SLA) report.35 Under the SLA, Indue was required to report against a number of key performance indicators (KPIs) on a weekly, then monthly basis.

2.30 Social Services did not have formal monitoring arrangements for the performance measures in the SLA at the trial commencement. Discussions were held with Indue in November 2016 to verify invoice calculations and SLA measurements relating to assessing contract performance, seven months after the trial commenced in Ceduna. The delays with the payment of invoices were inconsistent with Social Services’ Financial Instructions.36

Recommendation no.2

2.31 Social Services should employ appropriate contract management practices to ensure service level agreements and contract requirements are reviewed on a timely basis.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

2.32 The department agrees with the recommendation and will work to improve its contract management practices.

Procurement of an evaluator

2.33 The Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy, developed 1 December 2015, outlined the monitoring and evaluation objectives, high level approach and the projects that would be collated to create a final consolidated review of the program. The strategy outlined the intention to externally commission the ‘Independent Community Change Evaluation’. Subsequently, Social Services conducted a procurement process to identify an evaluator with expertise in the collection and analysis of primary survey data.

2.34 Social Services developed a procurement plan and identified a scoring approach with non-weighted criteria including: capability and capacity; past performance and current work; risk management; methodology; and financial — to assess and select the successful evaluator. The procurement plan was approved by a Social Services Senior Executive on 13 November 2015 and tenders were sought from five members from the Social Policy Research and Evaluation Panel.37 The evaluation of the tenders and contracting of the evaluator were scheduled to be finalised in December 2015, with the trial due to commence in Ceduna in March 2016.

2.35 Table 2.1 shows Social Services’ scoring of the three tenders it received. Social Services’ evaluation of the tenders was incomplete and not consistent with its own documented procurement evaluation process, method and report, with the assessment of cost/price (for each ‘… cost element’) not finalised for one of the tenders as per Social Services’ evaluation score sheet.38 Further, Social Services applied an inconsistent approach to evaluating the tenders, including by linking Criteria 4 and 5 in scoring the successful tender compared to the unsuccessful tenders.39 Social Services Evaluation Score Sheet template for assessing tenders notes ‘In assessing Capability the nominated referees must be contacted to confirm experience, competence and capability’. Social Services Tender Assessment Rating/Scoring Scale template indicates each score is based on the tender and a response from referees. Referees were not contacted for one of the tenders. The price of the successful tender (ORIMA) was around double the amount of the other tenders. Social Services subsequently negotiated to reduce the final tender price with ORIMA.40

Table 2.1: Scoring of tenders submitted to undertake the evaluation

|

|

Criteria 1 |

Criteria 2 |

Criteria 3 |

Criteria 4 |

Criteria 5 |

|

|

|

Capability and capacity |

Past performance and current work |

Risk management |

Methodology |

Financial |

Total score |

|

ORIMA Research |

8 |

8 |

7 |

8 |

6 (at $922,592) |

37 |

|

Colmar Brunton |

8 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

7 (at $435,677) |

35 |

|

Deloitte Access Economics |

6 |

7 |

6 |

4 |

7 (at $443,658) |

30 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Social Services’ documentation.

Recommendation no.3

2.36 Social Services should ensure a consistent and transparent approach when assessing tenders and fully document its decisions.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

2.37 The department agrees with the recommendation. The department will improve its internal control systems in the form of policy, procedures and guidance material to undertake and document efficient and effective procurement practices that achieve value for money.

Were arrangements in place to provide local support?

Social Services effectively established or facilitated arrangements to deliver local support to CDCT communities, although there were delays in the deployment of additional support services. As part of the CDCT, Social Services also trialled Community Panels and reviewed their effectiveness to inform broader implementation.

2.38 To provide local support in CDCT communities, Social Services put in place arrangements including Local Partners, additional support services, and Community Panels.

Local Partners

2.39 Local Partners41 provided general support, including facilitating initial card set up, account balance checking, bill payments, temporary and replacement cards and assisting participants to address issues as they arose. Local Partners were also tasked with providing information to participants on: the Community Panels; and the application process to reduce the proportion of their restricted funds below 80 per cent.

2.40 Local Partners provided on-the-ground support. There were two Local Partners in Ceduna and one each in Yalata, Oak Valley, Scotdesco and Koonibba. In the East Kimberley there were two Local Partners in Kununurra and one in Wyndham. Australia Post42 also provided some card services. All Local Partners, except one in Ceduna, were contracted for the commencement of each trial site and received training from Indue in the days following the commencement of the trial. Local Partners were supported by Social Services and Indue and provided with reference materials such as the Local Partner Training Manual and the Local Partner Administration Manual. Local Partners worked closely with Indue and the call centres to support trial participants over the trial period.

2.41 Local Partners advised the ANAO that as the trial progressed, fewer resources were needed for general CDC information and acute issue management as more participants became familiar with the CDC and were able to use the self-help kiosks to perform their account balance enquiries and funds transfers without assistance. One common issue encountered by Local Partners was participants not remembering the personal identification number (PIN) for their card and not having a mobile phone to which a new PIN could be securely sent. Local Partners advised the ANAO that they initially allowed their personal mobiles to be used by participants. As this was a security concern, Indue encouraged participants to use the Indue online web-portal (accessed via self-help kiosks) to reset their PIN, if they could remember their password, or use temporary cards which have a preset PIN.

Additional support services

2.42 In September/October 2015, Social Services and PM&C undertook a gap analysis of support services and, in conjunction with the local leaders, identified areas where additional support services would be needed to assist CDCT participants. For the:

- Ceduna region — additional funding of $1 million was announced in October 2015 to provide: drug and alcohol counsellors; a new 24/7 mobile outreach team; and support to access rehabilitation services; and

- East Kimberley — additional funding of $1.3 million was announced in November 2015 and the final funding amount was $1.6 million to provide: drug and alcohol counsellors; improved access to drug and alcohol rehabilitation for adolescents; and support for families facing challenges, for example, low school attendance.

2.43 Not all services were available for the commencement of the trial and there was limited uptake and usage of the services during the trial period. Social Services monitored and reported usage of support services to the Steering Committee. East Kimberley community leaders reported, including to the ANAO, that if there had been ongoing consultation regarding the delivery and focus of support services, then outcomes may have improved.

Community Panels

2.44 As part of the CDCT, Social Services established Community Panels — a forum led by a community leader where members of the community assessed applications from trial participants to vary the 80:20 quarantine ratio. Participants could submit an application to the Community Panel for a reduction in the quarantined portion of their income support payment from 80 per cent down to a legislated floor of 50 per cent.43 The application was assessed against pre-determined criteria and any supporting statement.44 The development and operation of a Community Panel, including when it would be established and whether members were paid, were community-led decisions.

2.45 Social Services, as part of the Project Closure Report process, reviewed the effectiveness of the Community Panels. They determined that the Community Panels were not as effective as envisaged, resulting in lengthy delays in making decisions and that they would not be introduced into new localities. Further discussion of the Community Panels is at paragraphs 3.61 to 3.63.

3. Performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting

Areas examined

This chapter examined whether the performance of the Cashless Debit Card Trial was adequately monitored, evaluated and reported, including: arrangements in place to monitor implementation; the establishment of key performance indicators; the approach and data underpinning the evaluation; the quality and accuracy of information reported to the Minister; and the extent to which the extension and roll-out of the Cashless Debit Card (CDC) was informed by evaluation of the trial.

Conclusion

Arrangements to monitor and evaluate the trial were in place although key activities were not undertaken or fully effective, and the level of unrestricted cash available in the community was not effectively monitored. Social Services established relevant and mostly reliable key performance indicators, but they did not cover some operational aspects of the trial such as efficiency, including cost. There was a lack of robustness in data collection and the department’s evaluation did not make use of all available administrative data to measure the impact of the trial including any change in social harm. Aspects of the proposed wider roll-out of the CDC were informed by learnings from the trial, but the trial was not designed to test the scalability of the CDC and there was no plan in place to undertake further evaluation.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at Social Services undertaking a post-implementation review and a cost-benefit analysis; improving arrangements and capability in monitoring, performance measurement and evaluation; and to continue to evaluate the CDC in current and future locations.

Were appropriate arrangements in place to monitor and analyse the implementation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial?

A strategy to monitor and analyse the CDCT was developed and approved by the Minister. However, Social Services did not complete all the activities identified in the strategy (including the cost-benefit analysis) and did not undertake a post-implementation review of the CDCT despite its own guidance and its advice to the Minister that it would do a review. There was scope for Social Services to more closely monitor vulnerable participants who may participate in social harm and their access to cash.

3.1 Social Services consulted with relevant stakeholders and embedded monitoring arrangements by developing the combined CDCT Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy (the Strategy), dated 1 December 2015. The Strategy was discussed and approved by the Assistant Minister for Social Services on 17 February 2016 and the Minister summarised aspects of the strategy, in letters regarding data sharing, to the South Australian and West Australian Premiers in February and March 2016 respectively (discussed further in paragraph 3.29).

3.2 The Strategy identified the aims of monitoring and evaluation including:

- to ensure that any unintended consequences of the programme are observed in real time and resolved in a timely manner. The trial also will give early and ongoing indicators of the overall impact of the trial on indicators of social harm.

- to assess the implementation of the trial and examine the impacts of cashless welfare delivery, and will do so by answering key evaluation questions and to produce an analysis which explores the social impacts which may be attributed to the trial.45

3.3 Specific projects to achieve the aims outlined in the Strategy included:

- a Monitoring Project — to be undertaken by the Welfare Debit Card Taskforce (later to become a line area in Social Services) with information from the project expected to be provided to the ‘… independent evaluator’; and

- an Evaluation Project — to be externally commissioned to ORIMA by Social Services. This is discussed from paragraph 3.19 onwards.

The Monitoring Project

3.4 The Monitoring Project identified various sub-projects and key activities to be completed. Table 3.1 lists the analysis and data proposed in the Monitoring Project and whether it was completed as planned.

Table 3.1: Comparison of proposed data and actual data used in monitoring the Cashless Debit Card Trial

|

Data source proposed in the Monitoring Project |

Data used in the monitoring of the CDCT? |

|

Data Collection Project — including the use of the Research and Evaluation Database.a |

Yes, although the ANAO found that the Research and Evaluation Database was not used. |

|

Merchant Sales Analysis — to report on changes to alcohol and gambling expenditure in the trial sites based on analysis of merchant sales reports. |

No, Social Services indicated to the ANAO that the data was not available. |

|

Specialised Product Viability Analysis — comprised of: a comprehensive analysis of the electronic functionality of the card; an analysis of the impacts on the local marketplace; relevant comparisons to other products; and a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. |

Partly — the ANAO found that the cost-benefit analysis was not undertaken during the trial period. The cost-benefit analysis was due to be completed in late 2017 (more than six months after the trial concluded). Social Services advised it is an ongoing project. |

|

Activities to monitor the operation of the CDCTb including from the analysis of the following data sources:

|

Yes, however the ANAO found that service provider information was not complete or it was inconsistently reported. Additionally, Social Services’ Data Exchange (DEX)d service provider data was not used as several providers only began reporting through DEX in the six months to June 2016 and there was no benchmark data available for the six month period to December 2015. Reporting was also limited for services that were not fully operational or where there was low take up. |

Note a: The monitoring strategy proposed the use of the Research and Evaluation Database, an amalgamation of Australian Government administrative data including the Department of Human Services’ Income Security Integrated System (ISIS) data and Integrated Employment System (IES) data, and information on demographics, income support payments received, family characteristics, housing information, and other income reported.

Note b: Monitoring card activation rates, community panel applications, external transfers and any issues reported by stakeholders, participants and the public through feedback and tip offs.

Note c: As noted in Chapter 2, Social Services contracted Indue to monitor participant account and merchant transaction information; non-compliance and fraud and regular reporting from Indue.

Note d: Data Exchange (referred to as DEX) is the IT system where performance information on service provision is shared between Social Services and service providers. It is also used by other departments. Department of Social Services, Data Exchange: About, [Internet] DSS, 2018, available from https://dex.dss.gov.au/about/ [accessed March 2018].

Source: ANAO analysis of Social Services’ documentation.

3.5 Social Services acknowledged that some aspects of the Monitoring Project had not been undertaken but advised that monitoring had been thorough.

3.6 Operational monitoring analysis was not shared between the two sections within Social Services that were responsible for monitoring and evaluating the CDCT or shared with its contracted evaluator, ORIMA, despite ORIMA having responsibility for reporting on some output KPIs. To effectively monitor and evaluate activities that the department was responsible for implementing, and which forms the basis for future decisions regarding the commitment of government expenditure, there would be merit in Social Services’ adopting a more coordinated and collaborative approach to sharing information within the department.

Monitoring quarantined income support payments

3.7 As noted in Chapter 1, the trial was to test any change in social harm (habitual abuse and community harm related to alcohol, gambling and drugs) from a reduction in the total amount of cash available in trial sites by quarantining 80 per cent of an income support recipient’s payment into their restricted Indue bank account.46 In addition to 20 per cent of a participant’s income support payment being unrestricted, local leaders in both trial sites agreed that an additional amount (up to $200) could be externally transferred by a participant out of their Indue account to their personal unrestricted account every 28 days. There was no requirement for these external transfers for other expenses to be approved by Social Services.

3.8 Social Services analysed the Indue data relating to trial participants who had made use of the external transfer facility and noted that the limit ‘…is not being misused by the majority of participants’. Social Services reporting indicated participants were receiving around an additional three per cent of funds as unrestricted cash as a result of the facility.

3.9 ANAO analysis showed that over 60 per cent of CDC participants utilised this facility over the trial period and over 40 per cent of participants transferred amounts between $190 and $200 over a period of 28 days at least once over the trial period. Figure 3.1 shows the number of individual participants making transfers by value ranges in both sites, during the trial period.

Figure 3.1: Number of participants making transfers by value in both sites, during the trial period

Source: ANAO analysis of Indue trial participant account data.

3.10 The ANAO analysed the change in the 80:20 ratio for a trial participant if an additional amount of $200 was withdrawn from their unrestricted bank account every 28 days. For a single person on Disability Support who was 22 years or older (with or without children), an additional $200 every 28 days increased their unrestricted income support amount to 32 per cent, with the level of unrestricted cash increasing to 61 per cent of the total payment for a single person, under 18, on Youth Allowance with no children, living with their parents.47

3.11 This facility had the potential to significantly change the restricted portion of income support for participants in trial sites (dependent on the type of income support payment the participant received); and increased cash availability in communities. Further, this situation compromised the ability of the local leaders to improve social outcomes as they had less leverage to reward favourable behaviour (by decreasing participants’ quarantined income support). Social Services did not use available data on indicators of vulnerability and social harm, such as the Research and Evaluation Database, to monitor the proportion of additional cash withdrawn, using the external transfer facility, by vulnerable CDCT participants.48

Post-implementation/Program performance/Program implementation reviews

3.12 Social Services’ guidance advised that ‘line areas contribute and are responsible for ensuring programmes are evaluation ready through the conduct of post-implementation or programme performance reviews and monitoring’.49 Social Services indicated to the Minister in September 2016 (around five months into the CDCT) that it would provide advice on implementation issues as it ’…progresses a Program Implementation Review’.

3.13 An implementation review did not proceed. Social Services advised the ANAO that ‘an additional implementation review, on top of the independent evaluation, would seem duplicative and not value for money’. Social Services further advised that aspects of the agreed review were included in the CDC evaluation. However, this was counter to Social Services’ guidance which states that an implementation review is separate to an evaluation50 and contrary to the CDCT final evaluation report which noted that the CDCT ‘… is primarily an outcomes evaluation and not an implementation review and, as such, its coverage of the implementation process is limited’.51

Recommendation no.4

3.14 Social Services should undertake a cost-benefit analysis and a post-implementation review of the trial to inform the extension and further roll-out of the CDC.

Department of Social Services’ response: Agreed.

3.15 The department agrees with the recommendation and has commenced a cost-benefit analysis and post-implementation review of the initial CDC trial. The department has also initiated a new independent evaluation of the CDC to commence in mid-late 2018.

Were there suitable key performance indicators developed to measure the performance of the Cashless Debit Card Trial?

Key performance indicators (KPIs) developed to measure the performance of the trial were relevant, mostly reliable but not complete because they focused on evaluating only the effectiveness of the trial based on its outcomes and did not include the operational and efficiency aspects of the trial. There was no review of the KPIs during the trial and KPIs have not been established for the extension of the CDC.

3.16 Social Services developed a draft program logic and identified expected outcomes that would result from the implementation of the CDCT52 in its Strategy. Social Services commissioned ORIMA Research (ORIMA) to further refine the program logic and develop key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure the effectiveness of the CDCT. The commissioning of ORIMA on 22 February 2016 (22 days before the trial commenced) allowed little time to develop, test, agree and establish baseline data to measure against the KPIs. The KPIs were developed by ORIMA, in consultation with stakeholders, over the first few months of the trial and provided to Social Services on 26 July 2016, over four months after the trial had commenced. Measures were developed for trial outputs, short-term outcomes and medium term outcomes in consultation with various stakeholders. The ANAO assessed53 the KPIs for their:

- Relevance — KPIs developed for the CDCT were largely relevant. A number of KPIs were not focused enough to specifically measure effectiveness, for instance, KPIs that related to support services. The indicator developed to assess the operational performance of the Community Panels did not take into account feedback from trial applicants.

- Reliability — KPIs developed for the CDCT were mostly reliable. There were issues with measurement and bias; and

- Completeness — KPIs developed for the CDCT were not complete. The output KPIs did not provide a balanced examination of the CDCT. In addition, KPIs relating to the administration and operational aspects of the trial54 and the associated development of metrics were mostly absent and without an implementation review — this left a gap.55

3.17 The KPIs that were developed did not address efficiency aspects of the CDCT, a key aim of the trial, but Social Services did estimate and report on the run (variable) costs of the CDC trial compared to the run costs for delivering income management.56 On 1 March 2017, Social Services provided advice to the Minister on the estimated higher run costs ($3713) for delivering the CDC trial per participant (in two remote locations) compared to the costs ($3280) of delivering income management (in a number of urban, regional and remote locations).57 The Minister was also advised of the estimated costs for the future expansion of the CDC, on the basis of two options — delivery in two remote and two regional locations ($1503) or three remote and one regional location ($1942).58

3.18 There was also a lack of ongoing reporting against KPIs, and as at December 2017, there were no KPIs in place for the extension of the CDCT in the trial sites.59 On this basis, arrangements were not established to effectively measure the wider aim of ‘encouraging socially responsible behaviour’.60

Was the evaluation of the Cashless Debit Card Trial supported by a sound approach and data?

Social Services developed high level guidance to support its approach to evaluation, but the guidance was not fully operationalised. Social Services did not build evaluation into the CDCT design, nor did they collaborate and coordinate data collection to ensure an adequate baseline to measure the impact of the trial, including any change in social harm.

Evaluation project

3.19 The Evaluation Unit in Social Services developed a range of high level guidance in mid-201561, which included advice on types of evaluations and appropriate methodologies to guide its business areas.62 The guidance indicated the role of the Evaluation Unit was to approve ‘…the scope, design, and timeframe for evaluations’, collaborating:

with line areas and Program Office to facilitate “evaluation readiness”–building evaluation into policy design and ensuring collection of appropriate data and performance information to support evaluation.

3.20 Although it had responsibility, the Evaluation Unit did not build evaluation into the policy design for the CDCT and did not determine the evaluation approach and how the evaluation would ‘…be conducted (e.g. in-house, consultancy, peer review) taking into account level of complexity, scale and funding available from program area’.

3.21 Instead, the Welfare Debit Card Taskforce developed Social Services’ Evaluation Project Brief and its proposed methodologies and measurements paper, and consulted with the Evaluation Unit and government stakeholders including the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), in July 2015. The Welfare Debit Card Taskforce also led the development of the Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy and consulted with the Evaluation Unit on 10 September 2015 prior to forwarding a copy of the Strategy to the Evaluation Unit on 22 September 2015.

3.22 In response to the Minister’s commitment to undertake a ‘…thorough evaluation of the impact of the Cashless Debit Card Trial’, the Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy outlined an approach to evaluate the trial using qualitative survey data, administrative income support and state data (South Australia and Western Australia). The Strategy noted that the evaluation would be externally commissioned and would ‘…primarily involve qualitative data collection and assess whether community members, especially individuals on the trial, observes changes in key indicators of community and social harm’ with the Strategy noting that information from Social Services and state governments would inform the final report on measuring the impact of the trial. Alternative evaluation approaches to establish a baseline and measure any changes in social harm were not considered.

Evaluation data and analysis

3.23 Social Services first met with the evaluation consultant, ORIMA, on 25 February 2016, when details of the contract including the evaluation methodology and data were discussed. Social Services noted at the meeting that: ‘Negotiations with WA and SA regarding the sharing of data are not as advanced as anticipated’.

3.24 The ANAO identified data available for the evaluation included: ORIMA survey data; state data on crime, gambling, hospital admissions and public housing, disruptive behaviour and complaints; local area data on service use; Commonwealth income support data; Indue card transaction data; and comparison site data.

3.25 ORIMA indicated to the ANAO that it was unable to collect baseline survey data to evaluate the trial given the evaluation was commissioned three and nine weeks prior to the commencement of the trial in Ceduna and the East Kimberley respectively.

ORIMA survey data

3.26 Primary survey data was collected by ORIMA from trial participants, families of trial participants and non-CDCT community members for the purpose of undertaking quantitative analysis. Interviews and focus groups were also arranged with community leaders, stakeholders and merchants to collect qualitative information. There were two waves of data collected for quantitative analysis and three waves of data collected for qualitative analysis.

3.27 Data collection at Wave 1 was achieved by interviewing every third or fourth person in a range of locations — an intercept survey63, until the target samples size were achieved.64 ORIMA’s method involved re-interviewing Wave 1 survey respondents in the Wave 2 survey, to enable a longitudinal approach to analysis. In practice, interview targets were not met and attrition, such as previous respondents that were not able to be interviewed, was higher than anticipated with only 28 per cent of trial participants responding to the survey in both waves of data collection.65 To address this, ORIMA undertook additional interviews with new respondents. This reduced the evaluator’s ability to compare outcomes for the same participants between waves.

3.28 ORIMA noted that they used the quantitative surveys as their primary data source to measure the impact of the trial, including measuring any change in social harm.66

State and community level administrative data

3.29 The Minister67 wrote to the South Australian and West Australian Premiers, in February and March 2016 respectively, approximately one month prior to the trial commencing in each site, seeking the Premiers’ support including in the provision of relevant data to monitor and evaluate the performance of the trial. The identification and request for specific data items from the states were discussed or sent to the relevant South Australian and West Australian departments one and three months into the 12 month trial, respectively.

3.30 Administrative data received by Social Services from the states for the evaluation included monthly and quarterly statistics on crime and intoxication apprehensions, hospital admissions (identifying those that were alcohol related), school attendance, housing debt, poker machine revenue, child abuse notifications, disruptive housing tenancies, outpatient counselling for substance abusers and homelessness. Community-level information included data on attendance at rehabilitation/sobering-up units and night patrol.

3.31 The ANAO found that limitations in the state data and the department’s approach to using it in the evaluation reduced how effectively the impact of the actual trial on social harm could be isolated and evaluated. For example, state statistics available to measure change in the amount of crime committed or gambling covered a greater geographical area than Ceduna with 60 per cent of the population captured in this data not in the trial area. Further, for some data items: statistics were not collected (e.g. hospital admissions in Kununurra and Wyndham); there was an insufficient time series to be able to measure any changes in the trial areas over time; and there was also a lack of consistency between the data available for the comparison sites (for instance, there is no hospital in Derby) compared to the trial sites. Further discussion on comparison sites is at paragraph 3.39.

Commonwealth and Indue administrative data

3.32 Various Social Services documentation, including the: Strategy, Evaluation Framework and advice drafted for a Social Services’ meeting with the Minister in April 201668, noted that Commonwealth administrative data, including the Research and Evaluation Database, would be analysed to measure the impact of the CDCT.

3.33 Social Services undertook internal analysis of longitudinal Commonwealth administrative data69 in October 2016, designed to ‘…supplement the Evaluation of the CDC Trial — Initial Conditions Report’. The analysis provided some aggregate descriptive statistics on the CDCT participants from 30 June 2015 to 30 June 2016, two and three months into the trial in the East Kimberley and Ceduna respectively.

3.34 Social Services asked ORIMA for assurance that the data and approach ORIMA was using would be sufficiently robust to assess the trial outcomes so that its senior executive could brief the Minister on its 12 month progress report on 15 June 2017. ORIMA, in its response, indicated that it would use participant survey data, qualitative interview/focus group data and state administrative data — highlighting its limitations. Social Services accepted ORIMA’s approach, despite ORIMA identifying that it was not intending to use Commonwealth administrative data in its approved approach to ‘triangulate’ the data sources to estimate the impact of the CDCT.

3.35 ORIMA reported to the ANAO that it linked Commonwealth income support administrative data70 and Indue data to produce CDC account balance and transaction dashboards ‘as part of program implementation feedback’ for Social Services. The linked data was also used to assess output KPIs to confirm that CDCT participants: had timely access to the Income Support Payments deposited into their CDC accounts; were able to successfully activate their CDCs; and could make purchases with their CDCs.

3.36 ORIMA noted in its CDCT final evaluation report that Human Services administrative income support data was used for a:

Comparison of the demographic characteristics of the Wave 1 and Wave 2 CDCT participant response samples against population benchmarks (age, gender and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin71 …

3.37 ORIMA outlined, in the final evaluation report, the administrative data72 it examined to assess performance on the effectiveness of the CDCT.73 This did not include the use of Indue Card and Commonwealth administrative data. ORIMA indicated to the ANAO that Social Services did not mention the potential use of the Research and Evaluation Database and Social Services did not provide ORIMA with this database.74.

3.38 Social Services’ ability to robustly measure the impact of the trial and any change in social harm was reduced because Commonwealth administrative data including the Research and Evaluation Database75 was not used as originally intended and there were limitations in obtaining adequate state data.

Comparison site data

3.39 Social Services initially indicated its intention to use comparison sites in its Strategy, noting that:

The evaluation and monitoring strategy will attempt to isolate and eliminate variables that are beyond the scope of influence of the debit card. Comparison location[s] may be observed directly if they present a reasonable and accurate comparison; however, the main comparison source will be wider statistical trends in the broader geographical locations.

3.40 The Evaluation Framework76 developed by ORIMA and agreed by the CDC Evaluation Steering Committee (discussed at paragraph 3.43) did not include an approach to observe individuals in a comparison location where the card was not implemented, relying on comparing statistical trends in the comparison sites proposed by the relevant states.

3.41 ORIMA reviewed the comparison sites (Coober Pedy and Port August for Ceduna and Derby for the East Kimberley) proposed by the South Australian and Western Australian Governments to determine their suitability on the basis of four Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas scores. The review did not consider whether there was consistent data available in the comparison and trial sites that would allow the same outcome variables to be measured.

3.42 Comparison sites were selected for the trial to compare aggregate outcomes of trial sites to locations where the card was not implemented. However, the comparison locations selected for the trial (Port Augusta and Derby) were known areas where trial participants regularly visited (some merchants were blocked in the sites due to possible circumvention). Due to these arrangements, the data and measurement of outcomes in the comparison sites (crime, gambling, and alcohol related hospital admissions) could have included trial participant behaviour which would introduce bias into the evaluation results.

Cashless Debit Card Trial Evaluation Steering Committee

3.43 The CDCT Evaluation Steering Committee (committee) was established to oversee the evaluation. The Committee membership included subject matter experts, state government, Social Services and PM&C regional and national representatives.

3.44 The committee’s first and only meeting was convened on 31 March 2016, where key issues including the methodology to be able to determine the impact of the trial (attribution) and the selection of comparison sites, was discussed. Further communication was through email with Social Services seeking input to key evaluation deliverables including the Evaluation Framework and subsequent evaluation reports. The committee’s feedback was provided to ORIMA. The most consistent areas of concern were: methodology; robustness of data and its general limitations; the tone; and the need for greater clarity in aspects of the reports.

Cost of the evaluation