Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Mitigating Insider Threats through Personnel Security

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s personnel security arrangements for mitigating insider threats.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) outlines a suite of requirements and recommendations to assist Australian Government entities to protect their people, information and assets. Personnel security, a component of the PSPF, aims to provide a level of assurance as to the eligibility and suitability of individuals accessing government resources, through measures such as conducting employment screening and security vetting, managing the ongoing suitability of personnel and taking appropriate actions when personnel leave. In 2014, the Attorney-General announced reforms to the PSPF to mitigate insider threats by requiring more active management of personnel risks and greater information sharing between entities. At the time of the audit, further PSPF reforms were being considered by the Government.

2. The Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) was established within the Department of Defence (Defence) from October 2010 to centrally administer security vetting on behalf of most government entities (with the exception of five exempt intelligence and law enforcement entities). Centralised vetting was expected to result in: a single security clearance for each employee or contractor, recognised across government entities; a more efficient and cost-effective vetting service; and cost savings of $5.3 million per year. ANAO Audit Report No.45 of 2014–15 Central Administration of Security Vetting concluded that the performance of centralised vetting had been mixed and expectations of improved efficiency and cost-effectiveness had not been realised.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The ANAO chose to undertake this audit because effective personnel security arrangements underpin the protection of the Australian Government’s people, information and assets, and the previous audit had identified deficiencies in AGSVA’s performance. In addition, the 2014 personnel security reforms occurred after fieldwork for the previous audit had been completed, so there was an opportunity to review the implementation of these reforms by AGSVA and other government entities.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s personnel security arrangements for mitigating insider threats. To form a conclusion on the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Does AGSVA provide effective security vetting services?

- Are selected entities complying with personnel security requirements?

5. The entities assessed for criterion two were the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority (ARPANSA), Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) and Digital Transformation Agency (DTA).1

Conclusion

6. The effectiveness of the Australian Government’s personnel security arrangements for mitigating insider threats is reduced by: AGSVA not implementing the Government’s policy direction to share information with client entities on identified personnel security risks; and all audited entities, including AGSVA, not complying with certain mandatory PSPF controls.

7. AGSVA’s security vetting services do not effectively mitigate the Government’s exposure to insider threats. AGSVA collects and analyses information regarding personnel security risks, but does not communicate risk information to entities outside the Department of Defence or use clearance maintenance requirements to minimise risk. Since the previous ANAO audit, AGSVA’s average timeframe for completing Positive Vetting (PV) clearances has increased significantly. AGSVA has a program in place to remediate its PV timeframes, and it has established a comprehensive internal quality framework. AGSVA plans to realise many process improvements through procuring a new information and communications technology (ICT) system, which is expected to be fully operational in 2023.

8. Selected entities’ compliance with PSPF personnel security requirements was mixed. While most entities had policies and procedures in place for personnel security, some entities were only partially compliant with the PSPF requirements to ensure personnel have appropriate clearances. None of the entities had fully implemented the PSPF requirements introduced in 2014 relating to managing ongoing suitability. In addition, entities did not always notify AGSVA when clearance holders leave the entity.

Supporting findings

Effectiveness of AGSVA’s security vetting services

9. AGSVA’s clearances do not provide sufficient assurance to entities about personnel security risks. A significant proportion of vetting assessments in 2015–16 and 2016–17 resulted in potential security concerns being identified, but the majority (99.88 per cent) of vetting decisions were to grant a clearance without additional risk mitigation. On rare occasions AGSVA minimised risk by denying the requested clearance level and granting a lower level, or avoided risk by denying a clearance. In some cases identified concerns, which were accepted by AGSVA on behalf of sponsoring entities, should have been communicated to entities or managed through clearance maintenance requirements.

10. AGSVA does not provide information about identified security concerns to sponsoring entities outside Defence due to a concern that disclosure would breach the Privacy Act 1988. The PSPF was revised in 2014 to require AGSVA to update its informed consent form to allow such disclosure to occur. Defence and AGD gave a commitment to Government in October 2016 that AGSVA would start sharing risk information in 2017–18. AGSVA updated its consent form in February 2017, but its revised form does not explicitly obtain informed consent to share information with entities. Consequently, AGSVA has not met the intent of the Government’s 2014 policy reform.

11. AGSVA’s information systems do not meet its business needs, which has resulted in inefficient processes and data quality and integrity issues. Defence is in the scoping and approval stages of a project to develop a replacement ICT system, which is expected to be fully operational in 2023. The audit included additional work on information security, which is the subject of a report prepared under section 37(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997.

12. AGSVA has recently commenced an organisational renewal project to address identified inefficiencies in its business processes, although it plans to realise many business process improvements through its new ICT system. Since the previous ANAO audit, timeframes for PV clearances have deteriorated significantly; for other levels, the percentage of cases completed within benchmark timeframes has improved.

13. AGSVA has implemented a comprehensive quality audit program for its contractors through its quality management system. It has also introduced periodic internal peer reviews for vetting decisions. It has not instituted a program of independent quality assurance of vetting delegates’ decisions.

Entity compliance with personnel security requirements

14. AGD, ARPANSA, ASIC and Home Affairs had plans, policies and procedures in place for personnel security. In some cases, these documents had not been updated to reflect 2014 revisions to PSPF personnel security requirements. DTA had not finalised any of these documents. There was limited evidence of entities undertaking personnel security risk assessments to inform their plans, policies and procedures.

15. AGD, ASIC, Home Affairs and DTA did not have adequate controls and quality assurance mechanisms for ensuring their personnel have appropriate clearances. For each of these entities, a small number of current personnel were identified who did not hold required clearances. Employment screening processes varied across the selected entities. AGD, ASIC and Home Affairs had higher denial rates than AGSVA and made greater use of aftercare.

16. All entities used the temporary access or eligibility waiver provisions of the PSPF to mitigate business impacts resulting from the timeframes to obtain, and eligibility requirements for, security clearances. AGD and Home Affairs used temporary access provisions appropriately to mitigate delays in onboarding personnel. AGD, ARPANSA, ASIC and DTA had not fully complied with PSPF controls for eligibility waivers.

17. AGD, ARPANSA, ASIC and Home Affairs had accessible policies and procedures for managing ongoing suitability, including change of circumstances and contact reporting, and mandatory security awareness training that covered personnel security requirements. DTA had not established these arrangements, as required under the PSPF. None of the entities had implemented the PSPF requirement to conduct an annual health check for clearance holders and their managers.

18. All entities were partially compliant with the PSPF requirement to inform AGSVA when security cleared personnel leave the entity. AGD, ARPANSA and DTA had not updated their employment screening forms to obtain informed consent from personnel to share sensitive information with AGSVA.

19. All entities had reported their compliance with the PSPF personnel security requirements for 2016–17 to relevant parties. The ANAO’s assessment of compliance differed from each entity’s self-reported compliance level.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.24

The Department of Defence, in consultation with the Attorney-General’s Department, establish operational guidelines for, and make appropriate risk-based use of, clearance maintenance requirements.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

Department of Defence’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.37

The Department of Defence implement the Protective Security Policy Framework requirement to obtain explicit informed consent from clearance subjects to share sensitive personal information with sponsoring entities.

Department of Defence’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 2.47

The Attorney-General’s Department and the Department of Defence establish a framework to facilitate the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency providing sponsoring entities with specific information on security concerns and mitigating factors identified through the vetting process.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

Department of Defence’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 3.6

The Attorney-General’s Department and the Digital Transformation Agency conduct a personnel security risk assessment that considers whether changes are needed to their protective security practices.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 3.9

The Digital Transformation Agency take immediate action to comply with the Protective Security Policy Framework governance requirements.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 3.37

The Attorney-General’s Department, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Department of Home Affairs and the Digital Transformation Agency implement quality assurance mechanisms to reconcile their personnel records with AGSVA’s clearance holder records, and commence clearance processes for any personnel who do not hold a required clearance.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s response: Agreed.

Department of Home Affairs’ response: Agreed.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.7

Paragraph 3.47

The Attorney-General’s Department, the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Digital Transformation Agency review their policies and procedures for eligibility waivers to ensure they are compliant with Protective Security Policy Framework mandatory controls.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority’s response: Agreed.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s response: Agreed.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.8

Paragraph 3.55

The Attorney-General’s Department, the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Department of Home Affairs and the Digital Transformation Agency implement the Protective Security Policy Framework requirement to undertake an annual health check for clearance holders and their managers.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority’s response: Agreed.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s response: Agreed.

Department of Home Affairs’ response: Agreed.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

20. Summary responses from five entities are provided below. Full responses from all entities are provided at Appendix 1.

Attorney-General’s Department

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the proposed audit report on Mitigating Insider Threats through Personnel Security. I welcome the report and I am grateful for the recommendations made to better manage personnel security risks both across Australian Government, and within the Attorney-General’s Department.

The timing of this report is helpful noting given the department is currently reforming the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) for application from 1 July 2018. A revised PSPF will provide a clearer and more accessible framework, specify requirements that are proportional to risks, integrate more coherently with other frameworks, and improve the Commonwealth’s approach to managing security risk. This report will continue to inform these reforms.

Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Authority

ARPANSA welcomed the ANAO audit on our personnel security program and supporting systems. The audit provided a great opportunity for our agency to measure the effectiveness of one element of our protective security program, that being the personnel security component. Importantly, the audit highlighted that, for the most part, ARPANSA has an effective and robust program ensuring the appropriate level of protection for our people, information and assets. The audit identified areas where further efforts can be directed to ensure the agency is proactive in the way we manage eligibility and ongoing suitability of employees and contractors.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission

ASIC welcomes the ANAO’s audit into personnel security arrangements. ASIC understands that personnel security is an important function, delivering a level of assurance about the credentials and integrity of our workforce and identifying our vulnerability to a range of insider threats. Throughout the conduct of the audit, ASIC continued to improve its processes and has since implemented procedures to rectify issues identified by the ANAO. ASIC welcomes the findings in the report and considers they provide useful recommendations for improvement in our current practices and reducing the threat from a malicious insider, through enhancements to our personnel security programs.

ASIC concurs with the three recommendations and has updated its Organisational Suitability Assessment to complement the Vetting assessment conducted by the AGSVA. Reforms to our personnel security management aim to achieve compliance with the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF). Our key reforms include better identification of security requirements, record keeping and quality assurance, as well as aftercare programs and annual health checks. ASIC confirms that it will implement the recommendations.

ASIC is enhancing its security policies to ensure that they better comply with the PSPF and address the current security threat environment.

Department of Defence

Defence notes the Audit Report on Mitigating Insider Threats through Personnel Security (the Report) and the reform efforts already underway to mitigate the malicious insider threat. The Report draws attention to the various aspects of personnel security reform efforts already in development, led by the Attorney General’s Department, in close consultation with Defence. Additionally, Defence notes that the Report highlights the internal reform efforts the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) have undertaken and the improvement in AGSVA’s performance over the last two years. AGSVA is still undertaking a significant reform program with many of the issues flagged in the Report planned for implementation in the next year.

The Report highlights mechanisms for information sharing that will guide agencies to develop clearance maintenance requirements, which are being actively considered and developed by the Attorney General’s Department (AGD), as the Commonwealth protective security policy lead. The AGD have overall responsibility for setting the policy parameters, and AGSVA as the main service delivery agency for security vetting.

AGSVA is implementing a program to strengthen security controls within the existing eVetting System, ahead of the delivery of the new system being implemented. AGSVA is working with cross-government and industry partners to ensure that the eVetting System and the systems with which it interfaces meet contemporary security standards.

Department of Home Affairs

Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the ANAO’s audit report on Mitigating Insider Threats through Personnel Security.

The Department of Home Affairs responds on the basis that the redactions noted in the report are not relevant to the Department. The report’s recommendations appear to be an accurate reflection regarding areas for improvement in Home Affairs.

Digital Transformation Agency

The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) agrees with the ANAO’s findings and recommendations and will take immediate steps to ensure that all are implemented by 31 July 2018.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Governance and risk management

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

The trusted insider threat

1.1 On 2 September 2014, the Attorney-General announced changes to the Australian Government’s protective security policy to address the threat posed by trusted insiders, stating:

The trusted insider can access—on an unprecedented scale today—massive amounts of sensitive information through our networked computers and copy and transfer it with ease. That is why the two largest breaches of Western intelligence information have occurred only recently.2

1.2 The two breaches referred to in the speech were the large-scale leaks of classified information by Edward Snowden in June 2013 and Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning in July 2013; individuals who had been engaged in positions of trust within the United States Government and held security clearances. The Attorney-General noted that these breaches had undermined international efforts to combat terrorism and organised crime, had a detrimental impact on Australia’s diplomatic relations, and potentially led to the loss of lives, highlighting the importance of taking action to mitigate insider threats.

The Protective Security Policy Framework

1.3 The Australian Government’s Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) outlines a suite of requirements, controls and recommendations to assist Commonwealth entities to protect their people, information and assets. Personnel security—one of the four components of the PSPF3—aims to provide a level of assurance as to the eligibility and suitability of individuals accessing Australian Government resources. Key personnel security measures include:

- Employment screening—checks, usually undertaken prior to commencement, to establish an individual’s identity and assess their suitability to access government resources;

- Security vetting—checks undertaken to assess the suitability of an individual to hold a security clearance allowing access to classified information;

- Managing ongoing suitability—ensuring individuals with access to government resources continue to meet suitability standards and comply with security measures such as the Contact Reporting Scheme; and

- Separation actions—ensuring individuals’ access to resources is withdrawn upon separation and they are aware of their ongoing obligations to protect information.

1.4 The policy changes announced by the Attorney-General in September 2014 were primarily revisions to the PSPF personnel security requirements to promote greater information sharing between entities about personnel security risk, and encourage entities to more actively monitor and manage the ongoing suitability of their personnel. The rationale for these changes was the recognition that several recent malicious insider incidents could have been prevented through more effective information sharing or more active monitoring of personnel demonstrating behaviours of concern.

The Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA)

1.5 The Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA) was established within the Department of Defence (Defence) from 1 October 2010 to centrally administer security clearances for most Australian Government entities.4 Centralised vetting was expected to result in: a single security clearance for each employee or contractor, recognised across government entities; greater consistency in vetting practice; more efficient vetting processes; and cost savings of $5.3 million per year.

1.6 AGSVA is a branch within the Defence Security and Vetting Service Division. As at July 2017, AGSVA had a staffing profile of 270 full-time equivalent positions, with most staff based in Canberra, Brisbane and Adelaide, and a smaller number of vetting staff based in regional offices across Australia. AGSVA also relies on an external workforce of more than 350 contractors through its Industry Vetting Panel and other contracting arrangements. In 2016–17 AGSVA had an operating budget of $50 million.

1.7 As at September 2017, AGSVA had 443,172 active security clearances recorded in its Personnel Security Assessment Management System (PSAMS2) database, of which 295,103 were at current clearance levels (see Table 1.1) and 148,069 were at previous clearance levels that were in use until 2010 (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.1: Active security clearances, current clearance levels, as at September 2017

|

Clearance level |

Classification level of accessible resources |

No. of active clearances |

|

Baseline |

Up to and including PROTECTED |

114,101 |

|

Negative Vetting Level 1 (NV1) |

Up to and including SECRET |

132,037 |

|

Negative Vetting Level 2 (NV2) |

Up to and including TOP SECRET |

39,258 |

|

Positive Vetting (PV) |

Up to and including TOP SECRET, including certain caveated, compartmented and codeword information |

9,707 |

|

Total |

295,103 |

|

Source: AGD, Australian Government Personnel Security Protocol, version 2.1, Canberra, April 2015, pp. 16–17, and ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

Table 1.2: Active security clearances, previous clearance levels, as at September 2017

|

Previous clearance level |

Current equivalent clearance level |

No. of active clearances |

|

Restricted and Entrya |

No equivalent (lower than Baseline) |

41,168 |

|

Protected |

Baseline |

28,102 |

|

Highly Protected |

No equivalent (between Baseline and NV1) |

7,570 |

|

Confidential |

No equivalent (between Baseline and NV1) |

38,154 |

|

Secret |

NV1 |

28,176 |

|

Top Secret Negative Vetting |

NV2 |

2,050 |

|

Top Secret Positive Vetting |

PV |

2,849 |

|

Total |

148,069 |

|

Note a: Restricted and Entry level clearances were entity specific levels and not recognised as whole-of-government clearance levels.

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

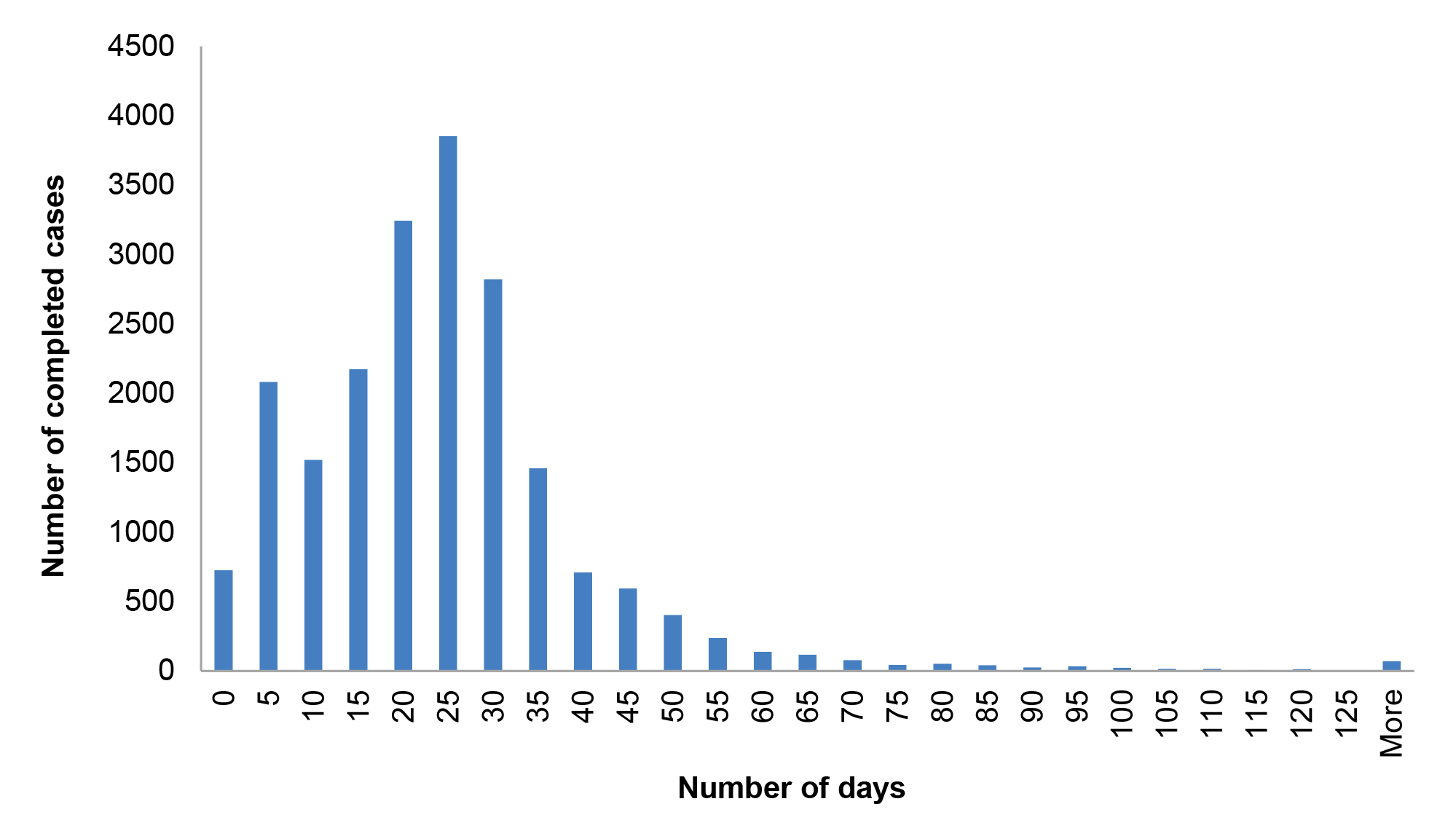

1.8 AGSVA processes a large number of clearance applications each year. Over the past six financial years, AGSVA has made an average of 39,000 vetting decisions each year, with a majority (83 per cent) of decisions at the Baseline and NV1 clearance levels (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Security vetting decisionsa by clearance level, 2011–12 to 2016–17

Note a: The ANAO has defined vetting decision as initial and upgrade cases granted or denied and revalidation cases continued or revoked; excludes reviews for cause, cancellations and other administrative outcomes.

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA’s reported vetting statistics, 2011–12 to 2016–17.

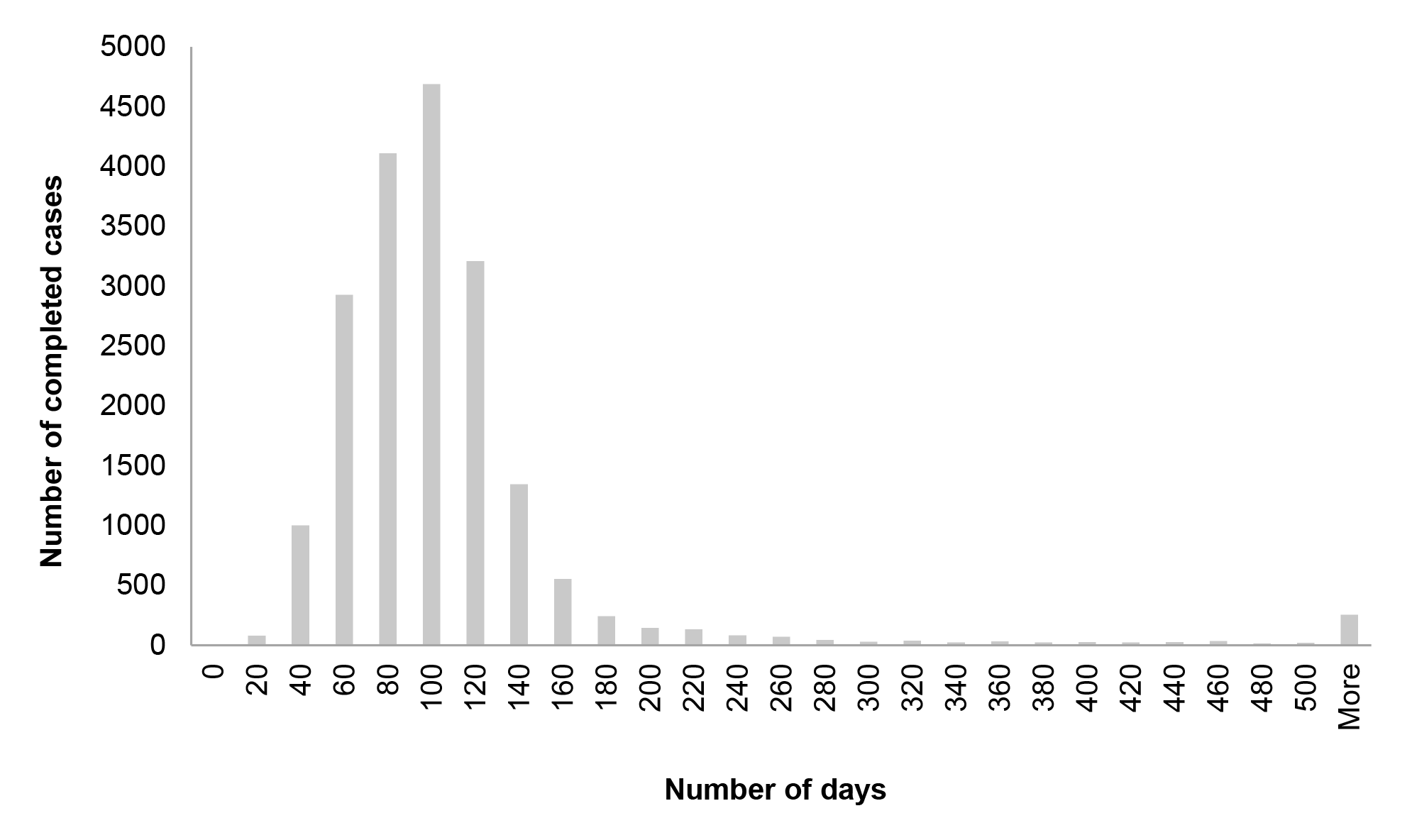

1.9 AGSVA groups clearance sponsors into three categories: Defence; Defence industry service providers; and other entities.5 The proportion of all security vetting cases finalised in 2016–17 was broadly equivalent across these sponsor types, ranging from 30 per cent for Defence industry service providers to 38 per cent for Defence (see Figure 1.2). However, proportions varied markedly by clearance level: 45 per cent of Baseline clearances finalised in 2016–17 were for other entities; whereas 87 per cent of PV clearances were for Defence.

Figure 1.2: Percentage of vetting decisionsa by sponsor type, 2016–17

Note a: Includes initial and upgrade cases granted or denied and revalidation cases continued or revoked; excludes reviews for cause, cancellations and other administrative outcomes.

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

1.10 The services AGSVA delivers, and the responsibilities of clearance holders and the entities that sponsor clearances, are defined in a Service Level Charter. AGSVA is oversighted by a Governance Board, comprised of senior representatives from selected sponsoring entities, which considers issues relating to the governance of the Charter. AGSVA also maintains formal agreements with relevant partner agencies, such as the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), which undertakes security assessments for all NV1, NV2 and PV level clearances and Baseline clearances on request.

Entity responsibilities for personnel security

1.11 Under the PSPF, primary responsibility for protective security rests with portfolio ministers and agency heads. While AGSVA provides security vetting services to government entities, agency heads are ultimately responsible for managing the security risks posed by their personnel. The PSPF’s ‘Protective security principles’ include the principle that:

Agency Heads are to ensure that employees and contractors entrusted with their entity’s information and assets, or who enter their entity’s premises:

- are eligible to have access

- have had their identity established

- are suitable to have access, and

- are willing to comply with the Government’s policies, standards, protocols and guidelines that safeguard that entity’s resources (people, information and assets) from harm.6

1.12 To meet the intent of this principle, entities must comply with a series of 36 mandatory requirements (the fourteen requirements most relevant to personnel security are outlined at Appendix 2). In addition, entities must adopt mandatory controls, and should adopt better practice recommendations, as outlined in a suite of PSPF personnel security policy documents. At the time of conducting this audit, these documents were:

- ‘Australian Government Personnel Security Core Policy’ (web page, updated June 2016)7;

- Australian Government Personnel Security Protocol (April 2015);

- Personnel security guidelines—Agency personnel security responsibilities (April 2015);

- Personnel security guidelines—Vetting practices (June 2016);

- Identifying and managing people of security concern—Integrating security, integrity, fraud control and human resources (January 2015); and

- Managing the insider threat to your business—A personnel security handbook (March 2016).

Current PSPF reforms

1.13 During 2016, AGD led a whole-of-government review of the PSPF in response to the Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation (August 2015) (Belcher Review). Recommendations from the Belcher Review relating to security vetting are outlined in Box 1. Recommendation 21.7 reinforced the need for greater information sharing between AGSVA and entities, which (as noted in paragraph 1.4 above) was one of the intended outcomes of the changes to the PSPF announced in September 2014.

1.14 In October 2016, the Government agreed to a suite of measures to strengthen personnel security to mitigate insider threats, to be implemented between 2016–17 and 2018–19, including: developing a framework for assessing ongoing suitability; streamlining and strengthening the vetting process through better use of existing government data holdings; and authorising entities that can meet the required standard to issue Baseline clearances to their own personnel (addressing Recommendation 21.5 of the Belcher Review).

1.15 At the time of conducting this audit, AGD was working with Defence and other relevant entities to implement reforms to the PSPF stemming from its review, with a target date of 1 July 2018 for changes to the PSPF to come into effect.

|

Belcher Review recommendations relating to security vetting |

|

21.5 To reduce the regulatory burden on staff and improve security outcomes, AGD work with Defence and other relevant entities to develop and cost options for reform to personnel security policy which would:

21.6 AGD work with the APSC to coordinate work across entities to identify and resolve potential privacy impediments arising from consent requirements for employment screening or security vetting processes. 21.7 Defence provide entities with greater visibility of information about security clearance holders identified through centralised security vetting processes to enable those risks to be proactively managed in entities. |

Source: Barbara Belcher, Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation—Report to the Secretaries Committee on Transformation, volume 1, Canberra, August 2015, p. 40.

Previous ANAO report

1.16 The ANAO previously reviewed the performance of AGSVA in ANAO Audit Report No.45 of 2014–15 Central Administration of Security Vetting, tabled in Parliament in June 2015. The ANAO concluded that the performance of centralised vetting had been mixed and expectations of improved efficiency and cost-effectiveness had not been realised. The ANAO found AGSVA had consistently failed to meet its clearance processing benchmark timeframes, had accumulated a backlog of over 13,000 clearances overdue for revalidation, and had inadequacies with its quality assurance processes, information systems and performance framework. The audit report recommended that Defence:

- implement a targeted audit program to assess Industry Vetting Panel contractors’ operations;

- introduce a program of internal peer review supplemented by periodic independent quality assurance of delegate decisions; and

- develop a clear pathway to achieve agreed timeframes for processing and revalidating security clearances.8

1.17 In addition, the audit outlined a number of suggestions to improve the effectiveness of AGSVA’s operations, including that AGSVA:

- investigate the underlying causes of increasing numbers of clearance subjects cancelling clearances during the vetting process (which peaked at 34 per cent in 2015–16);

- strengthen its controls for managing sensitive personal information captured as part of the vetting process (including details of personnel medical and criminal records);

- improve the quality of its performance measurement and reporting; and

- consider how best to provide feedback to client entities on security concerns identified during vetting, to facilitate those entities’ monitoring of affected personnel.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 The ANAO chose to undertake this audit because effective personnel security arrangements underpin the protection of the Australian Government’s people, information and assets, and the previous audit had identified deficiencies in AGSVA’s performance. In addition, the 2014 personnel security reforms occurred after fieldwork for the previous audit had been completed, so there was an opportunity to review the implementation of these reforms by AGSVA and other government entities.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s personnel security arrangements for mitigating insider threats.

1.20 To form a conclusion on the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Does AGSVA provide efficient and effective security vetting services?

- Are selected entities complying with personnel security requirements?

1.21 The audit involved following up on recommendations and suggestions from the ANAO’s previous performance audit of AGSVA (ANAO Audit Report No.45 of 2014–15). It also examined selected entities’ compliance with PSPF personnel security requirements, with a focus on measures undertaken to mitigate insider threats and communication between AGSVA and client entities on personnel security matters. The assessment of AGSVA focussed on progress since the previous performance audit was tabled in Parliament in June 2015. The assessment of selected entities focussed on compliance during 2015–16 and 2016–17.

1.22 Examination of vetting practices within intelligence and law enforcement agencies exempt from using AGSVA’s vetting services was out of scope. In addition, the audit did not consider in detail the PSPF reforms being developed by AGD for implementation in 2018. However, where relevant to audit findings, reference has been made within this report to current implementation progress.

Characteristics of selected entities

1.23 In conducting the audit, the ANAO examined the performance of five selected entities in complying with PSPF personnel security requirements: AGD; Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA); Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC); Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs)9; and Digital Transformation Agency (DTA). These entities were selected to provide coverage of a variety of entity functions, locations and sizes.

Table 1.3: Characteristics of selected entities, as at 30 June 2017

|

Characteristic |

AGD |

ARPANSA |

ASIC |

Home Affairs |

DTA |

|

Functiona |

Policy |

Specialist |

Regulatory |

Larger Operational |

Smaller operational |

|

Personnel locations |

All states and territories and overseas |

NSW and Victoria |

All states and territories |

All states and territories and overseas |

ACT and NSW |

|

Ongoing employees |

1,719 |

128 |

1,648 |

13,124 |

164 |

|

Non-ongoing employees |

424 |

19 |

226 |

675 |

34 |

|

Total employees |

2,143 |

147 |

1,874 |

13,799 |

198 |

Note a: Function descriptions as per Australian Public Service Commission classifications.

Source: Australian Public Service Commission (APSC), Australian Public Service Statistical Bulletin 2016–17, September 2017, data tables, Excel workbook, available from: <http://www.apsc.gov.au/about-the-apsc/parliamentary/aps-statistical-bulletin/statisticalbulletin 16-17> [accessed 17 October 2017].

Audit methodology

1.24 The major audit tasks included:

- extracting and analysing data from AGSVA’s security vetting system, entity human resources information management systems and other relevant databases;

- reviewing entity documentation such as policies, plans, reviews, briefs, procedures, performance reporting, assurance reports, registers and risk assessments; and

- interviewing staff within AGSVA and Defence, in security, human resources and information technology roles within selected entities, and from other relevant entities such as the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation.

1.25 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $494,000.

1.26 Team members for this audit were Daniel Whyte, Benjamin Siddans, Alice Bloomfield and Deborah Jackson.

2. Effectiveness of AGSVA’s security vetting services

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency’s (AGSVA’s) security vetting services are effective.

Conclusion

AGSVA’s security vetting services do not effectively mitigate the Government’s exposure to insider threats. AGSVA collects and analyses information regarding personnel security risks, but does not communicate risk information to entities outside the Department of Defence or use clearance maintenance requirements to minimise risk. Since the previous ANAO audit, AGSVA’s average timeframe for completing Positive Vetting (PV) clearances has increased significantly. AGSVA has a program in place to remediate its PV timeframes, and it has established a comprehensive internal quality framework. AGSVA plans to realise many process improvements through procuring a new information and communications technology (ICT) system, which is expected to be fully operational in 2023.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at making greater risk-based use of clearance maintenance requirements, finishing updates to clearance holder consent requirements, providing risk information to sponsoring entities, and remediating ICT control weaknesses.

Do AGSVA’s security clearances provide sufficient assurance about personnel security risks?

AGSVA’s clearances do not provide sufficient assurance to entities about personnel security risks. A significant proportion of vetting assessments in 2015–16 and 2016–17 resulted in potential security concerns being identified, but the majority (99.88 per cent) of vetting decisions were to grant a clearance without additional risk mitigation. On rare occasions AGSVA minimised risk by denying the requested clearance level and granting a lower level, or avoided risk by denying a clearance. In some cases identified concerns, which were accepted by AGSVA on behalf of sponsoring entities, should have been communicated to entities or managed through clearance maintenance requirements.

2.1 The purpose of a security clearance is to provide a level of assurance to entities that an individual (the clearance holder) is suitable to access security classified information.10 Standards for security vetting are specified by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) in the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) policy document: Personnel security guidelines—vetting practices (the vetting guidelines).11 The vetting guidelines specify the minimum personnel security checks required for Baseline, NV1, NV2 and PV clearances, and outline adjudicative guidelines for vetting officers and delegates for assessing common risk factor areas that may impact on an individual’s suitability to hold a clearance (see Table 2.1 for an overview of factor areas, potential security concerns and mitigating factors).

Table 2.1: Risk factor areas for assessing suitability to hold a security clearance

|

Factor area |

Example security concerns |

Example mitigating factors |

|

External loyalties, influences and associations |

Foreign citizenship, contact with foreign nationals, or substantial financial interests or employment in foreign countries. Involvement in, or association with persons or groups involved in, espionage, terrorism or politically motivated violence. |

Reasons for multiple citizenships are not a security concern. Clearance subject was unaware of unlawful aims of an individual or organisation and severed ties upon learning of these. |

|

Personal relationships and conduct |

Untrustworthy, unreliable or dishonest conduct. Conduct or contacts that create vulnerability to exploitation, such as high risk or criminal sexual behaviour. |

Conduct occurred prior to or during adolescence and there is no evidence of subsequent similar conduct. |

|

Financial considerations |

Inability to live within one’s means, satisfy debts or meet financial obligations. |

Initiated good-faith efforts to repay overdue creditors and otherwise resolve debts. |

|

Alcohol and drug usage |

Excessive alcohol consumption, use of illegal drugs or misuse of prescription drugs. |

Making satisfactory progress in treatment program and no history of relapse. |

|

Criminal history and conduct |

A criminal offence, multiple lesser offences, or association with criminals. |

So much time has elapsed that it is unlikely to recur. |

|

Security attitudes and violations |

Deliberate or negligent non-compliance with security requirements, such as unauthorised use of ICT systems. |

Security violations were due to improper or inadequate training. |

|

Mental health disorders |

Certain emotional, mental and personality conditions that may impair judgement, reliability or trustworthiness, or failure to follow treatment advice related to a condition. |

Condition is readily controllable with treatment, and clearance subject has demonstrated ongoing and consistent compliance with treatment plan. |

Source: AGD, Personnel security guidelines—vetting practices, version 1.3, June 2016, section 5.2.

2.2 The vetting guidelines do not specify graduated risk tolerance thresholds for different clearance levels; rather, they outline potentially disqualifying security concerns and mitigating factors that apply to all levels. Higher clearance levels represent increasing levels of assurance that clearance subjects are suitable, based on longer assessment periods (from five years for Baseline to 10 years or from 16 years of age, whichever is greater, for PV) and more rigorous and intrusive testing (see Appendix 3 for the checks required for each clearance level).

2.3 Since AGSVA conducts security vetting services for more than 150 Australian Government entities (as well as state and territory entities), it is not required to provide clearances tailored to specific entity risks. For example, a law enforcement entity may have a lower tolerance for criminal associations or drug usage than other entities, but AGSVA does not consider this distinction when deciding whether to grant or deny a clearance. A clearance granted by AGSVA, which is transferable between entities, provides generic assurance that a clearance holder is suitable to access classified material, with entities expected to undertake employment screening to address entity-specific risks (discussed in Chapter 3).

AGSVA’s vetting decisions

2.4 A security vetting assessment (or clearance case) can result in several possible outcomes:

- grant—grant of a new clearance, or continuation or upgrade of an existing clearance;

- deny and grant lower level—denial of the requested clearance level and grant or continuation of a lower clearance level;

- deny—denial of a new clearance, or revocation of an existing clearance;

- cancel—cancellation of a clearance request (for example, if the clearance subject ceases employment); or

- other—other administrative outcomes such as rejecting an incomplete clearance case or downgrading a clearance level due to a change in an entity’s requirements.

2.5 The ANAO examined the outcomes of clearance cases completed in 2015–16 and 2016–17 (see Table 2.2). Excluding administrative outcomes (cancel and other), 99.88 per cent of vetting decisions were to grant, 0.06 per cent were to deny and grant a lower level, and 0.06 per cent were to deny a clearance.12

Table 2.2: Clearance case outcomes by clearance level, 2015–16 to 2016–17a

|

Clearance case outcome |

Baseline |

NV1 |

NV2 |

PV |

All levels |

|

Grant |

38,713 (70.35%) |

36,658 (69.04%) |

11,493 (63.68%) |

2,407 (31.30%) |

89,271 (66.69%) |

|

Deny and grant lower level |

4 (0.01%) |

14 (0.03%) |

16 (0.09%) |

21 (0.27%) |

55 (0.04%) |

|

Deny |

9 (0.02%) |

26 (0.05%) |

12 (0.07%) |

6 (0.08%) |

53 (0.04%) |

|

Cancel |

13,423 (24.39%) |

14,410 (27.14%) |

6,064 (33.60%) |

4,371 (56.85%) |

38,268 (28.59%) |

|

Other |

2,877 (5.23%) |

1,986 (3.74%) |

463 (2.57%) |

884 (11.50%) |

6,210 (4.64%) |

Note a: Includes initial, upgrade and revalidation cases; excludes reviews for cause.

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

2.6 In addition to clearance cases, AGSVA conducts a small number of reviews for cause, which involve reassessing the suitability of an existing clearance holder due to an identified security concern.13 AGSVA completed 46 reviews for cause during 2015–16 and 2016–17, resulting in an additional 22 grant, eight deny and grant lower level, and 16 deny decisions (not included in the results in Table 2.2).

Management of identified security concerns

2.7 Personnel security risk is a spectrum in which many clearance subjects demonstrate some behaviours or qualities of concern, and judgement is required to determine if the risk is acceptable. The vetting guidelines provide high level statements about potential security concerns and mitigating factors, so vetting decisions are heavily reliant on the professional judgement of vetting officers and delegates.14

2.8 Vetting officers frequently identify potential security concerns during their assessment of a clearance subject, with approximately 43 per cent of all vetting assessments undertaken during 2015–16 and 2016–17 identifying concerns against one or more of the seven factor areas (see Table 2.1 above for descriptions of these factor areas). For clearances granted over this period, the extent to which concerns were identified varied by clearance level (as shown in Table 2.3 below). Since higher clearance levels involve more rigorous checks and cover a longer period of a clearance subject’s life, the rigour of the process may contribute to the identification of more security risk factors (both by increasing the chance a concern will be detected and by discouraging clearance subjects from concealing information from the vetting officer).

Table 2.3: Identified clearance holder risks for granted clearances, 2015–16 to 2016–17

|

Clearance level |

Percentage cases with potential concerns identified for factor areas |

One or more factors areas |

||||||

|

|

External loyalties |

Relation-ships & conduct |

Financial |

Alcohol & drugs |

Criminal history |

Security attitudes |

Mental health |

|

|

Baseline |

24.46% |

0.50% |

0.33% |

6.83% |

4.71% |

0.12% |

0.72% |

32.64% |

|

NV1 |

30.64% |

1.80% |

5.61% |

12.71% |

8.18% |

0.53% |

3.75% |

47.69% |

|

NV2 |

37.57% |

11.71% |

11.28% |

27.78% |

12.94% |

2.65% |

16.26% |

65.95% |

|

PV |

44.68% |

36.70% |

15.37% |

45.63% |

18.09% |

12.47% |

43.97% |

87.41% |

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

2.9 To arrive at a vetting decision, AGSVA vetting officers and delegates consider the identified security concerns and mitigating factors and assess the level of residual risk associated with a clearance subject. In broad terms, AGSVA has four options for managing residual risks:

- avoid the risk, by denying the subject a clearance;

- reduce the risk, by modifying controls or implementing further controls, such as granting a clearance with maintenance requirements or granting a lower level clearance;

- share the risk, by granting a clearance and sharing information about identified security concerns and mitigating factors with a sponsoring entity’s security office; or

- accept the risk, on behalf of a sponsoring entity, by granting a clearance without sharing risk information or implementing clearance maintenance requirements.15

2.10 Out of the 89,379 vetting decisions made by AGSVA during 2015–16 and 2016–17 (excluding reviews for cause):

- 53 (0.06 per cent) involved avoiding risk through denying a clearance;

- 55 (0.06 per cent) involved reducing risk through denying the requested level and granting a lower level; and

- two (0.002 per cent) involved reducing risk through granting a clearance with maintenance requirements.

2.11 As discussed later in this chapter (paragraphs 2.30–2.46, pages 34–37), AGSVA does not share risk information with sponsoring entities outside of Defence due to its interpretation of privacy requirements. In the overwhelming majority of cases, AGSVA’s approach to managing personnel security risks identified through its vetting process was to accept residual risks on behalf of sponsoring entities.

2.12 AGSVA advised the ANAO that reasons for its relatively low denial rate include:

- rigorous recruitment processes conducted by public sector entities and the Australian Defence Force, which can include pre-employment checks (such as psychological and organisational suitability assessments for Defence intelligence agencies) that exclude personnel on the basis of identified security concerns (discussed in Chapter 3)16;

- clearance subjects not complying with the vetting process to avoid security concerns being identified, leading to the cancellation of the clearance; and

- the procedural fairness process, which involves providing an individual who AGSVA is proposing to deny a clearance with an opportunity to respond to identified security concerns, uncovering additional mitigating factors that lead to a grant decision.

2.13 AGSVA’s denial rate is also a reflection of its risk appetite—that is, the thresholds it employs for denying a clearance at different clearance levels reflect the levels of residual risk it determines are acceptable. In 2017, AGSVA commenced work to document and standardise its risk tolerance thresholds through the development of a vetting decision risk model, based on work undertaken by AGSVA’s psychologists on a structured professional judgement instrument for assessing psychological risk factors. AGSVA informed the ANAO that it plans to start using the risk model in 2018 and subsequently integrate it into its new ICT system, which it anticipates will be fully operational in 2023.

2.14 While development of this model should help AGSVA to codify its risk appetite and aid consistent decision making, there is also scope for AGSVA to make greater use of other risk treatment options that involve collaborating with sponsoring entities to manage personnel security risks.

Resolving doubt in favour of national interest

2.15 The vetting guidelines state, ‘Any doubt concerning the clearance subject’s suitability must be resolved in favour of the national interest’.17 However, an internal review of AGSVA, finalised in March 2016, found: ‘The clearance process is over-weighted towards protecting risk to AGSVA through incorrect denial compared with risk to national security’.18 This finding was based on the observation that, until October 2017, AGSVA’s vetting processes required any case that an initial delegate decided should be a denial to pass through two additional stages of consideration (see Figure 2.1 below).

Figure 2.1: Denial decision pathway

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA procedural documentation.

2.16 First, a potential denial case progressed to the complex vetting team, where another vetting officer reassessed the case. If the complex vetting officer agreed it should be a denial, it proceeded to procedural fairness, providing the clearance subject with an opportunity to respond to any identified security concerns. After receiving a procedural fairness response, and further consideration by a complex vetting officer and delegate, a final decision to deny or downgrade a clearance was made by the Assistant Secretary Vetting.19

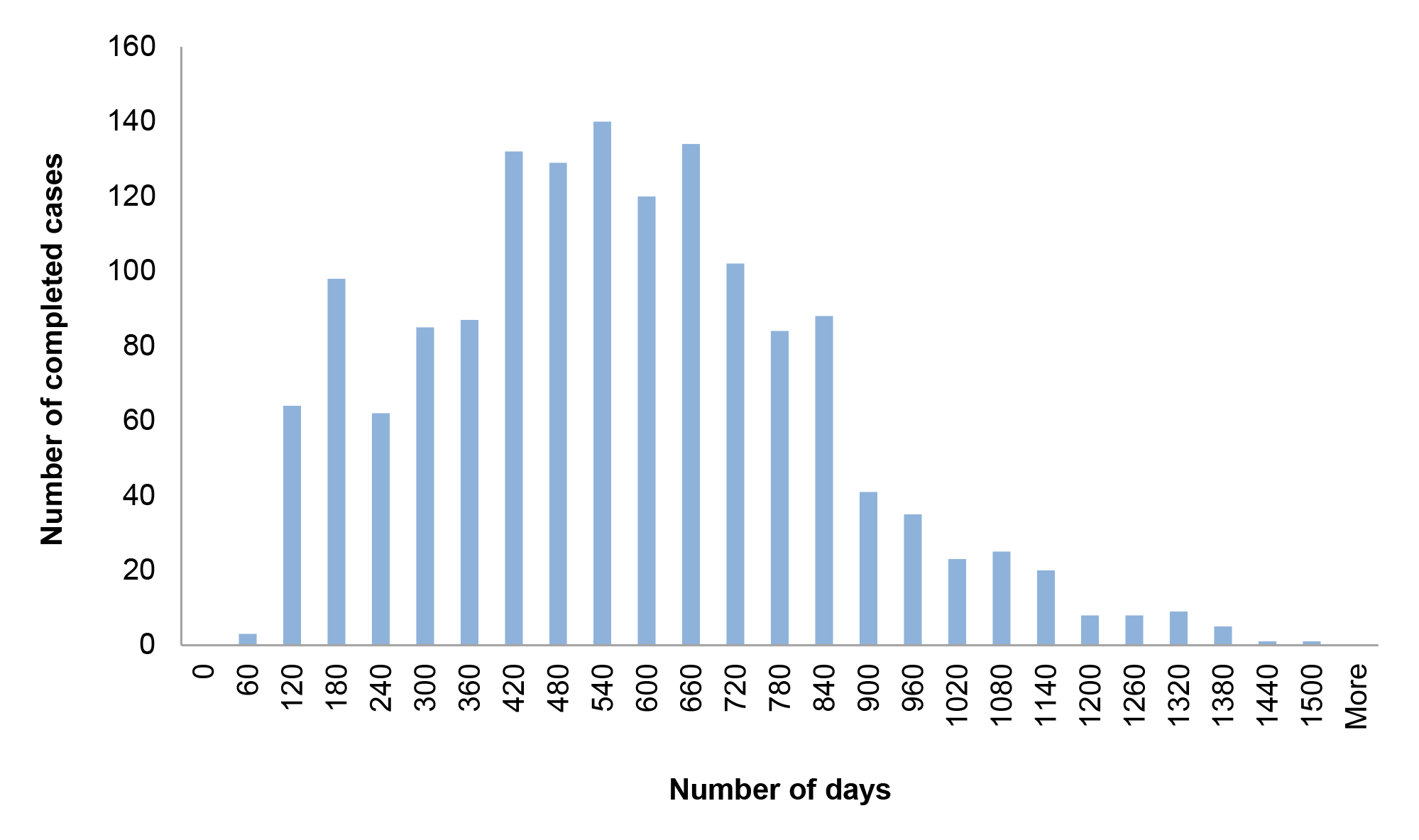

2.17 These additional consideration stages greatly increased the time taken to finalise complex vetting decisions (as shown in Table 2.4). Further, at each additional round of consideration a delegate may grant a clearance, increasing the likelihood that an initial deny decision would be overturned. Of the 431 complex cases completed during 2015–16 and 2016–17, 23 per cent were cancelled prior to a final vetting decision, 53 per cent resulted in a grant, 12 per cent in a denial and grant of a lower level clearance, and 12 per cent in a denial.

Table 2.4: Case durations for complex and non-complex cases, 2015–16 to 2016–17

|

Clearance level |

Case type |

Number of cases |

Average case duration (days) |

Benchmark timeframes |

|

Baseline |

Non-complex |

41,842 |

27.4 |

One month (~30 days) |

|

Complex |

37 |

144.8 |

||

|

NV1 |

Non-complex |

39,780 |

123.1 |

Four months (~120 days) |

|

Complex |

81 |

640.1 |

||

|

NV2 |

Non-complex |

12,305 |

186.9 |

Six months (~180 days) |

|

Complex |

56 |

697.2 |

||

|

PV |

Non-complex |

3,407 |

512.6 |

Six months (~180 days) |

|

Complex |

158 |

792.6 |

||

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

2.18 AGSVA abolished its complex vetting team in October 2017, based on a recommendation of the March 2016 internal review. Going forward, cases subject to a denial decision will proceed directly to the procedural fairness stage.

Use of clearance maintenance requirements

2.19 The extent to which AGSVA can provide assurance to sponsoring entities regarding personnel security risks is limited by the binary nature of AGSVA’s vetting decisions, which generally avoid risk by denying a clearance or accept risk on behalf of a sponsoring entity by granting a clearance.

2.20 The vetting guidelines state that clearances may be granted subject to clearance maintenance requirements (or aftercare), which are specific requirements that a clearance holder must comply with to retain their clearance (such as random drug testing, ongoing treatment for identified mental health issues, or regular reporting).20 Under the PSPF guidelines, AGSVA is responsible for identifying maintenance requirements and consulting with sponsoring entities and clearance subjects to gain their agreement to any requirements applied. Once implemented, the sponsoring entity and clearance subject are responsible for managing compliance with maintenance requirements and reporting on compliance to AGSVA.21

2.21 In 2015–16 and 2016–17, 280 of the 431 complex cases resulted in the grant of a clearance (230 at the requested level, and 50 at a lower level). In all of these cases, the original vetting officer and delegate determined that the clearance should be denied—indicating there was a degree of doubt regarding the level of residual risk. As noted in paragraph 2.10, AGSVA only applied clearance maintenance requirements on two occasions over that period; in both cases for clearances sponsored by Defence. Case study 1 provides an example of a complex vetting case AGSVA completed for an external entity where clearance maintenance requirements were not imposed but could have been considered. This case study also shows that AGSVA’s risk tolerance decisions do not take into account entity employment suitability considerations.

|

Case study 1. Multiple security concerns identified but not communicated to entity |

|

In 2016, a law enforcement entity requested an upgrade of a clearance subject’s existing Protected clearance to a NV2 clearance. AGSVA’s vetting assessment identified security concerns in five of seven factor areas, three of which were still considered to be a concern after mitigating factors had been identified:

The vetting officer recommended the clearance upgrade be denied, which was supported by the delegate. Following quality assurance review of the case, the complex vetting team delegate determined that the initial recommendation required reconsideration and an NV2 clearance was granted. The complex vetting officer considered that:

Although the clearance subject was employed by a law enforcement entity with a stated ‘zero tolerance’ policy for personnel using illegal drugs, no information from the case was disclosed to the sponsoring entity, and no clearance maintenance conditions were applied. |

2.22 AGSVA informed the ANAO that AGD leads Commonwealth protective security policy and is responsible for setting policy parameters for when and how clearance maintenance requirements should be used and where accountabilities for their implementation lies. As noted in paragraph 2.20 above, PSPF policy documents currently articulate these parameters at a high level. AGD advised the ANAO that, under the proposed 2018 revisions to the PSPF, clearance maintenance conditions will continue to be a shared responsibility of AGSVA, the sponsoring entity and clearance subject.

2.23 Greater use of clearance maintenance requirements would increase the level of assurance provided by AGSVA’s security clearances by enabling collaboration between AGSVA and sponsoring entities about managing residual personnel security risks. As part of its current project to develop a vetting decision risk model, AGSVA should establish operational guidelines for appropriate, risk-based use of clearance maintenance conditions. AGD could assist AGSVA in operationalising this aspect of security vetting policy, by providing input to the development of these guidelines.

Recommendation no.1

2.24 The Department of Defence, in consultation with the Attorney-General’s Department, establish operational guidelines for, and make appropriate risk-based use of, clearance maintenance requirements.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

2.25 The department acknowledges the importance of the effective use of clearance maintenance requirements to allow entities to engage with and manage risks associated with their security cleared personnel’s access to Australian Government resources. The department commits to providing Defence with information and support to enable AGSVA to make greater use of clearance maintenance requirements. The department will also use existing stakeholder forums to discuss and support the use of clearance maintenance. The department will continue to consult with Defence on the development of a framework to assess the ongoing suitability of security clearance holders, including operational guidelines for sponsoring agencies.

Department of Defence’s response: Agreed.

Cancellation of clearances

2.26 ANAO Audit Report No.45 of 2014–15 suggested that a greater understanding of the reasons for cancellations would assist AGSVA in identifying opportunities for efficiency.22 Table 2.2 above shows that approximately 28 per cent of clearance cases completed during 2015–16 and 2016–17 ended in cancellation.

2.27 The March 2016 internal review of AGSVA speculated that clearances cancelled during the assessment process may be the result of a deterrent effect, stating:

While no data on the reasons for people cancelling their applications is collected, some of the applicants who cancel out of the process could be doing so because they have found another position while they were waiting for a clearance. For other applicants, the self-cancellation rate could indicate inappropriate applicants dropping out of the system.

2.28 AGSVA’s internal analysis of clearance cases cancelled during 2016–17 indicates that 55.6 per cent of cancellations were due to the clearance subject failing to submit a vetting pack or to comply with a request for further information. AGSVA informed the ANAO that some unsuitable individuals may withdraw from the process when they understand the nature of the information being collected.

2.29 As noted in paragraph 2.16 above, around 23 per cent of complex cases were cancelled prior to a final vetting decision, which is lower than the overall cancellation rate. In addition, cancelled complex cases represented only 0.3 per cent of all clearance cancellations. Analysis by the ANAO identified that the majority of cancellations occur prior to AGSVA completing its initial vetting assessment, as shown in Table 2.5. Consequently, there is no clear evidence that clearance subjects cancel their application after becoming aware of a potentially adverse vetting assessment.

Table 2.5: Stages at which cancellations occur, 2015–16 to 2016–17

|

|

Baseline |

NV1 |

NV2 |

PV |

|

Cases cancelled prior to completing factor assessment, with no vetting officer recommendation recorded |

13,339 (99.4%) |

13,950 (96.8%) |

5,921 (97.6%) |

4,283 (97.9%) |

|

Cases cancelled after completing factor assessment |

82 (0.6%) |

464 (3.2%) |

146 (2.4%) |

90 (2.1%) |

|

Total cancellation cases |

13,421 |

14,414 |

6,067 |

4,373 |

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

Does AGSVA share relevant information with client entities?

AGSVA does not provide information about identified security concerns to sponsoring entities outside Defence due to a concern that disclosure would breach the Privacy Act 1988. The PSPF was revised in 2014 to require AGSVA to update its informed consent form to allow such disclosure to occur. Defence and AGD gave a commitment to Government in October 2016 that AGSVA would start sharing risk information in 2017–18. AGSVA updated its consent form in February 2017, but its revised form does not explicitly obtain informed consent to share information with entities. Consequently, AGSVA has not met the intent of the Government’s 2014 policy reform.

2.30 As noted in paragraph 1.4, PSPF policy reforms announced by the Attorney-General in September 2014 were designed to promote greater information sharing and collaboration on personnel risk management between AGSVA and entities. AGD’s revised personnel security policy documents, released in September and November 2014, outlined the following mandatory controls:

Vetting agencies are to advise sponsoring agencies of any information provided as part of the vetting process or ongoing clearance maintenance that may impact on a person’s suitability to access Australian Government resources or where risk mitigation measures are required.23

Vetting agencies are to obtain written informed consent from all clearances subjects to share information with other agencies for the purposes of assessing their ongoing suitability.24

2.31 AGD included a sample informed consent form and privacy notice as an annex to the vetting guidelines, which vetting agencies could use to obtain clearances subjects’ written informed consent to share personal information, including sensitive information, with sponsoring entities.25 AGD obtained advice that appropriate informed consent would allow AGSVA to share such information with entities under the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act).

2.32 ANAO Audit Report No.45 of 2014–15 noted entities’ concerns about AGSVA’s level of communication regarding personnel security risks. The audit included a suggestion that AGSVA consider how best to provide feedback to entities on specific security concerns identified during vetting.26

2.33 In addition, the Belcher Review recommended that AGSVA provide entities with greater visibility of information on clearance holders to enable them to proactively manage security risks (see Recommendation 21.7 in Box 1 on page 21). The review noted that the Canadian Government’s centralised security vetting model allows entities to make the decision on whether or not to grant a clearance based on recommendations from a centralised vetting provider, and information on personnel security risks is provided to entities.27

Revisions to AGSVA’s consent form

2.34 AGSVA commenced work on developing a revised informed consent form for its security clearance application pack in late 2014. In February 2017, after a protracted internal debate about the content of the form and subsequent delays in incorporating it into its clearance pack, AGSVA commenced using a revised form, ‘SVA 021: Security Clearance Informed Consent and Official Secrecy Acknowledgement’. In informing entity security advisors of the change, AGSVA stated the revisions to the form allowed it to meet the PSPF mandatory control to obtain informed consent from personnel.

2.35 Unlike the sample informed consent form and privacy notice included in the vetting guidelines, AGSVA’s form did not explicitly state that it would share sensitive personal information with sponsoring entities for the purpose of assessing their ongoing suitability. Earlier drafts of the form included an explicit statement that AGSVA would share personal information with entities, but the final version of the SVA 021 form did not.

2.36 After publishing its revised form in February 2017, AGSVA came to the view that the form does not provide fully informed consent to share sensitive personal information with entities. As at February 2018, AGSVA had not initiated a project to update the SVA 021 consent form. More than three years after the PSPF was revised to require AGSVA to gain informed consent from clearance subjects, AGSVA has not met the intent of this reform and is non-compliant with the PSPF mandatory control.

Recommendation no.2

2.37 The Department of Defence implement the Protective Security Policy Framework requirement to obtain explicit informed consent from clearance subjects to share sensitive personal information with sponsoring entities.

Department of Defence’s response: Agreed.

Current information sharing arrangements

2.38 As noted in paragraph 2.5, 99.88 per cent of vetting decisions made by AGSVA resulted in the grant of a clearance. The only information that is routinely shared with entities is that a clearance has been granted at a particular level. Information on potential security concerns and associated mitigating factors identified through the vetting process is not shared with entities.28

2.39 In recent years, AGSVA has used a mechanism called ‘risk advisory notices’ (RANs) to share limited risk information with entities in the following situations:

- Provisional access requests—where entities seek to provide individuals with provisional access to classified material prior to clearance being granted, AGSVA can undertake a preliminary review and provide a RAN outlining any generic factor areas in which potential security concerns have been identified (for example, ‘Alcohol and drug usage’);

- Direct request—occasionally entities have requested advice to support an organisational suitability assessment, and AGSVA has made a case-by-case decision on whether to provide a RAN;

- Change of circumstances—when a change of circumstances form submitted by an entity or clearance subject has initiated a review of their clearance, AGSVA has occasionally provided a RAN to the sponsoring entity (although in such cases AGSVA noted that the entity is usually already aware of the issue).

2.40 The ANAO examined AGSVA’s records of requests to share information from personal security files received during 2015–16 and 2016–17 for any requests received from sponsoring entities.29 In four instances, each involving Home Affairs, AGSVA released information on the basis of informed consent that the entity had obtained from the clearance subject. In one other instance, involving a different entity, information was not released.

2.41 Over that same period, AGSVA granted 89,271 clearances, 38,925 of which involved identified potential security concerns that were accepted by AGSVA on the basis of mitigating factors. Case study 1 (page 31) provides an example in which AGSVA accepted personnel security risks on behalf of a sponsoring entity without communicating the nature of the risks to the entity.

2.42 In August 2017, AGSVA advised its whole-of-government oversight forum that:

[RANs] may be seen as pre-empting the assessment process and may result in sanctions that significantly disadvantage the clearance subject and/or expose either AGSVA or the sponsoring agency to appeal or litigation… Additional work and legal advice is required to fully understand the legal and policy constraints of RANs.

2.43 In October 2016, AGD and Defence gave a joint undertaking to Government that AGD would identify solutions to allow AGSVA to share information with entities in 2016–17 and AGSVA would implement information sharing within the vetting process in 2017–18.

2.44 Planning documents for Defence’s ‘ICT2270 Vetting Transformation’ project (discussed in the next section) indicate it intends to integrate the capability to share risk information with external entities within this new system. The new ICT system is not expected to be fully operational until 2023.

2.45 When AGSVA updates its informed consent form, in line with Recommendation no.2 (paragraph 2.37), at the same time it should revise its business processes to enable it to routinely provide sponsoring entities with risk information about clearance subjects, during the vetting process (for provisional access requests), at the point of granting a clearance, and when an entity sponsors an existing clearance. This will allow entities to consider, in light of their individual risk tolerances, whether identified security concerns warrant further treatments (such as requiring individuals to provide regular updates to the security office on matters of concern).30

2.46 As AGD is responsible for security vetting policy and Defence is responsible for whole-of-government vetting operations, they should work together to develop operational policies and guidelines that specify:

- what level of risk information should be shared and in what form;

- who within entities it should be shared with (for example, an entity’s security advisor or security executive); and

- any caveats or restrictions that should be placed on entities’ use of risk information.

Recommendation no.3

2.47 The Attorney-General’s Department and the Department of Defence establish a framework to facilitate the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency providing sponsoring entities with specific information on security concerns and mitigating factors identified through the vetting process.

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed.

2.48 The department acknowledges the importance of communicating risk information to sponsoring entities and other vetting agencies as part of the initial process of security vetting and to support the ongoing assessment of personnel’s suitability to hold a security clearance. Sharing security relevant information within an entity and between entities is essential to appropriately safeguard Australian government resources and can help prevent and detect a range of threats, including the trusted insider threat.

2.49 The department, in consultation with Defence and a number of other departments and agencies, is developing a range of resources to support risk information sharing such as clearance suitability risk factor guidelines and a fact sheet on information sharing to address misconceptions about perceived limitations to information sharing, as well as specific mechanisms such as templates and guidance to support Defence, and other vetting agencies, in sharing risk information with sponsoring entities.

Department of Defence’s response: Agreed.

Does AGSVA have appropriate systems to support its vetting services?

AGSVA’s information systems do not meet its business needs, which has resulted in inefficient processes and data quality and integrity issues. Defence is in the scoping and approval stages of a project to develop a replacement ICT system, which is expected to be fully operational in 2023. The audit included additional work on information security, which is the subject of a report prepared under section 37(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997.

2.50 AGSVA’s vetting services are supported by the eVetting system31, which from an end-user perspective consists of three primary components:

- the Personnel Security Assessment Management System (PSAMS2)—which acts as a vetting case management system;

- ePack 2—which allows clearance subjects to complete and submit security vetting packs through an online portal; and

- Security Officer Dashboard—an online dashboard that allows security officers in entities to look up limited information about clearance subjects.

2.51 ANAO Audit Report No.45 of 2014–15 identified shortcomings in AGSVA’s ICT systems relating to the security of clearance records, data quality and the ability of the systems to support AGSVA’s business processes.

Security of clearance records

2.52 At the time of the ANAO’s previous audit, Defence had conducted two reviews of AGSVA’s information security.32 The reviews had identified that Defence was not compliant with all of the requirements of the Australian Government Information Security Manual and found deficiencies in the controls framework surrounding AGSVA’s clearance records which could lead to unauthorised access and loss of information.33

2.53 The ANAO conducted further work in this area. In accordance with section 37(1)(a) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (Cth) (the Act), the Auditor-General determined to omit particular information relating to this matter, including an additional recommendation to Defence, from this public report. The reason for this is that the Auditor-General is of the view that such information would be contrary to the public interest in that it would prejudice the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth, as per section 37(2)(a) of the Act.

2.54 In accordance with section 37(5)(b) of the Act, a report including the omitted information and additional recommendation has been prepared and a copy provided to the Prime Minister, the Attorney-General, the Minister for Defence, the Minister for Finance and the Minister for Home Affairs.

Data quality

2.55 The ANAO’s previous audit of AGSVA identified data quality issues with clearance records held in the eVetting system, such as the presence of duplicate records and date-related anomalies.34 Anomalies of this nature continue to be present within the eVetting system.35

2.56 AGSVA is heavily reliant on manual review by staff to detect data quality issues in new clearance requests submitted by sponsoring entities, such as incorrect dates of birth, duplicate records and missing information. AGSVA does not require clearance holders to verify their personal information, and relies on change of circumstances reports from clearance holders and sponsoring entities to ensure its biographical records are up to date (discussed in more detail in Chapter 3).

2.57 The ANAO did not systematically verify the quality of AGSVA’s clearance data holdings, but was able to identify obvious errors and discrepancies in the biographical data of clearance holders. Examples of these issues are shown in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6: PSAMS2 data quality issues

|

Measure |

Number of cases, as at 11 September 2017 |

Number of cases with decisions made between 1 January 2017 and 11 September 2017 |

|

Clearance holder aged over 100 |

5 |

1 |

|

Clearance holder aged under 10 |

65 |

1 |

|

Clearance holder date of birth in the future |

3 |

0 |

|

No recorded location of birth |

89,282 |

3,774 |

|

Active primary clearances with revalidation dates more than five years in the past |

194 |

57 |

|

Probable duplicate clearance subject recordsa |

2,238 |

N/A |

Note a: The ANAO considered a clearance subject record to be a probable duplicate if first name, family name, year of birth, birth location and primary sponsoring entity were identical to at least one another record.

Source: ANAO analysis of AGSVA clearance data.

2.58 AGSVA should take a more proactive approach to identifying, preventing and resolving anomalous data. In late 2017, AGSVA commenced a pilot project with a single sponsoring entity to validate clearance subject data, with an aim of initiating a project in 2018 to further validate clearance holdings in advance of transferring information to its new ICT system.

Supporting AGSVA’s business processes