Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Medicare Electronic Claiming Arrangements

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Medicare electronic claiming arrangements, including an assessment of the extent to which claiming and processing efficiencies for the Government, health professionals and Medicare customers have been achieved.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Electronic claiming for Medicare benefits was first introduced in 1992. Channels to facilitate electronic claiming were progressively introduced for use by medical practitioners, members of the public and private health insurers over the intervening decades. In 2016–17, claims for just over 97 per cent of the approximately $22 billion of Medicare benefits paid were lodged electronically.

2. The Department of Human Services (Human Services or the department) currently administers eight electronic claiming channels: six provider channels for point of service claiming1 and two channels for claiming by patients at their convenience. In addition Human Services provides a number of manual claiming options (in-person, dropbox, post and phone). Most of the electronic claiming channels were introduced ten or more years ago—prior to Medicare’s integration into the Department of Human Services in July 2011.2 The provider channels are:

- Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (1999);

- Medicare Online (2002);

- Electronic Claim Lodgement and Information Processing Service Environment (2004);

- Easyclaim (2007);

- Bulk Bill Webclaim (2015); and

- Patient Claim Webclaim (2016);

3. The additional channels for use by patients are Claiming Medicare Benefits Online (2011) and Express Plus Medicare Mobile App (2013).

4. The department’s administration of claiming channels is focussed on its overarching strategy of achieving as close as possible to 100 per cent electronic claiming.

5. On 19 October 2016, the Government announced it will replace the current systems used by Human Services to deliver health, aged care and related veterans’ payments as they are ‘old, complex and at risk of failure and therefore need to be upgraded’.3 The program of work is being led by the Department of Health and supported by the Departments of Human Services and Veterans’ Affairs, and the Digital Transformation Agency. This decision provides Human Services a further opportunity to consider what if any changes could be made to the current channel service offer.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of Medicare electronic claiming arrangements, including an assessment of the extent to which claiming and processing efficiencies for the Government, health professionals and Medicare customers have been achieved.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Was effective planning undertaken for the implementation and ongoing delivery of Medicare electronic claiming channels?

- Has the implementation and ongoing delivery of Medicare electronic claiming channels been effective?

- Does Human Services monitor and evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness with which it delivers Medicare electronic claiming?

Audit methodology

8. The audit’s methodology included:

- examination of documentation relating to the administration of Medicare electronic claiming channels, including program documentation and performance reports;

- review and analysis of departmental data related to the performance (take-up, costs/savings and timeliness) of the range of electronic channels currently available;

- ANAO analysis of quantitative data from Human Services ICT systems; and

- interviews with relevant departmental staff.

Conclusion

9. The Department of Human Services has been effective in driving the take-up of Medicare electronic claiming, with more than 97 per cent of all claims for Medicare services being lodged electronically. The department’s approach to implementing future Medicare electronic claiming could be improved by clear analysis of the costs of developing and maintaining individual claiming channels and the extent to which planned efficiencies have been realised.

10. The objectives of introducing electronic claiming (to improve convenience and timeliness and reduce costs to Government and the health care sector) have been met through the introduction of a range of individual channels over time to allow claiming by different users. Human Services has mechanisms in place to identify issues and consider whether channels can be improved to meet user needs.

11. The introduction of electronic claiming channels has led to improved access to payments for the community and providers. More than 97 per cent of claims for Medicare services are lodged electronically and a majority of these are paid within one day of lodgement.

12. The ANAO reviewed the available data related to expected savings and costs from implementing electronic claiming channels. These expected savings were only estimated by Human Services in some cases. Where estimates were made either take-up rates or dollar savings have not been achieved.

13. Although the department monitors rates of electronic lodgement and tracks movements between channels by claim type and reductions in manual services, the long term benefits and relative efficiencies from introducing individual channels are largely unknown.

14. Human Services’ monitoring and reporting includes business analytics used to inform channel delivery, and departmental management of risks and issues are supported by a range of plans. The department’s delivery of claiming channels is not supported by either: benchmarking of expected achievements; or a full understanding of the costs and benefits of individual claiming channels. There is a lack of information on whether the development of individual channels has delivered the intended administrative savings; and whether the savings achieved have outweighed the costs of introducing new channels. As such the department has not established a sufficiently strong information base to inform its business decisions.

Supporting findings

Planning and strategy

15. The Department of Human Services has identified the objectives and intended benefits of electronic claiming. The overall intent of introducing electronic claiming has been to increase the convenience to providers and patients, reduce costs to government and medical providers and improve the timeliness of claim processing. These objectives are consistent with Human Services’ Channel Strategy and Digital Transformation Strategy and its current strategy to deliver as close as possible to 100 per cent of electronic claiming at point of service.

16. Electronic claiming channels have been developed to meet the needs of providers, patients and private health insurers, and to reduce manual processing for the department. The available channels allow claiming across the three claiming/billing methods and for the claims to be lodged at the point of service or at a time convenient to the claimant.

17. Human Services engages with peak stakeholder groups and providers to share information about business issues and consider improvements. The department measures channel usage and conducts analysis to identify health practices that continue to lodge manual claims. This data, along with the stakeholder feedback, is used by the department to target strategies to promote electronic claiming.

Implementation

18. The high level of provider and patient take-up of electronic claiming (with 97.1 per cent of claims for services lodged electronically at the point of service) reflects the convenience, accessibility and timeliness of electronic claiming.

19. Efforts undertaken by Human Services to increase electronic patient claiming rates for services provided by general practitioners and specialists have been successful albeit there is scope to improve claiming rates for other practitioners, in particular pathologists, although increasing the number of pathology claims lodged at the point of service may require adjustments to the legislative framework. Patient claims account for less than two per cent of all claimed pathology services but around 20 per cent of all patient claims lodged manually.

20. Given that Human Services has achieved 97.1 per cent electronic claiming at an aggregate level it is expected that savings to the department have been realised overall. The costs associated with introducing and maintaining these electronic claiming channels have not been tracked over time and the expected savings from introducing individual channels have not been realised within anticipated timeframes.

21. Anticipated savings for each channel have been estimated using standard assumptions of the price differential between manual and electronic claiming and projected channel take-up rates. The department has consistently overestimated the take-up rates when introducing new channels and has not followed up to determine whether the cost savings for individual channels have been met.

22. Human Services does not currently track the relative costs of maintaining each claiming channel. There would be benefit in Human Services developing the capability to better understand the costs of each channel, as well as the administrative savings and other benefits that have been realised, to support decisions about future directions for, and investments in, electronic claiming.

23. Electronic claiming allows for increased automation of processing and payment of Medicare benefits and has improved timeliness. Not all electronic claims are able to be processed automatically. Human Services continues to make system enhancements to reduce the amount of manual intervention required.

Monitoring and reporting

24. Human Services has established relevant monitoring and reporting against its objective of attaining as close as possible to 100 per cent electronic claiming at the point of service. These reporting mechanisms inform the department’s electronic claiming strategy. The department also monitors user satisfaction and service availability—information that can be used to highlight areas of improvement.

25. The department’s monitoring and reporting on channel delivery does not cover all relevant aspects of electronic claiming service delivery. The department does not monitor the ongoing administrative costs and benefits of individual channels and therefore has an incomplete understanding of the performance of each channel against their respective business objectives.

26. Risks to the administration of Medicare electronic claiming channels have been managed effectively. The key risks to Medicare payment integrity and system functionality are addressed in a range of plans.

27. The Modernising Health and Aged Care Payments Services Program is in its early stages. Human Services is supporting the lead agency, the Department of Health, to understand the current state of service delivery and technology. Human Services’ principal role comprises remediation activities to allow existing systems to continue to operate reliably and effectively.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 4.19

To better inform its ongoing business decisions, the Department of Human Services should ensure its electronic claiming channel delivery strategy is supported by clear analysis of the costs and benefits of:

- establishing and maintaining electronic claiming channels; and

- maintaining manual Medicare claiming options.

Department of Human Services response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

28. The summary response to the report from Human Services is provided below, with the covering letter included in Appendix 1.

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes the ANAO’s key finding that Medicare electronic claiming arrangements are effective, with more than 97 per cent of all Medicare services now lodged electronically. In line with the recommendation, the department will ensure that future decisions on its electronic claiming channel delivery strategy are supported by clear analysis of the costs and benefits.

Key learnings and opportunities for Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings and areas of good practice identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Commonwealth entities when implementing electronic services.

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Medicare was introduced in 1984 to subsidise a range of medical services for Australian residents and certain categories of visitors. In 2016–17, 24.9 million people were enrolled in Medicare and $22.4 billion was paid in benefits for more than 399 million services. Medicare accounts for one-third of the Commonwealth health budget, with spending expected to increase every year—from $23.7 billion in 2017–18 to $27.9 billion in 2020–21.

1.2 Legislation covering the main elements of the Medicare program is contained in the Health Insurance Act 1973 (the Act). The Act provides that Medicare benefits are paid for clinically relevant services provided in Australia that are consistent with the legislative framework.

1.3 For Medicare benefits to be payable, the relevant professional service must be listed in relevant legislation, including Determinations. The fees for the service are included in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)—a listing of most of the Medicare services that are subsidised by the Australian Government (known as items). The MBS may be updated at any time during the year and currently lists over 5700 items.

1.4 Medical practitioners are able to set their own fees for their services. The Medicare benefit is therefore a subsidy for patients to provide them with financial assistance towards the costs of their medical services in circumstances where the amount of the subsidy is less than the total fee for the service.

1.5 The payment of benefits only occurs after a service has been rendered by a registered medical practitioner (provider) to a patient who is eligible for Medicare benefits. One or a number of services can be submitted together in a ‘claim’. There are three types of claims: patient, bulk bill and simplified billing:

- A health provider can ‘bulk bill’ a patient—this means that the claimant has assigned their right for the Medicare benefit to be paid to the health professional. The health provider can claim the Medicare benefit from the Department of Human Services (Human Services or the department) as full payment for the service and not charge the patient a fee.

- If the health provider charges the patient a fee for the service, the patient can claim the Medicare benefit by:

- paying the account, and then, if the health provider or practice offers electronic claiming, practice staff can lodge the claim electronically with Human Services from the point of service;

- paying the account and then claiming the Medicare benefit from Human Services either by mail, phone, in person at a service centre or by one of the two electronic claiming channels available for use by patients;

- lodging an unpaid account with Human Services and receiving a cheque made payable to the health provider which the patient gives to the provider along with any outstanding balance; or

- Claims for in-hospital services provided to patients can be made through simplified billing arrangements which streamlines the way patients pay their accounts and claim benefits from Human Services and their private health insurer. Simplified billing claims can be lodged by hospitals, billing agents, providers and day surgeries with both the department and private health insurers either electronically or manually.

1.6 In 2016–17, 399 485 575 Medicare services were processed by Human Services. Of these services:

- 78.5 per cent (313 576 052) were claimed through bulk billing;

- 13.3 per cent (52 968 967) were patient claimed; and

- 8.2 per cent (32 940 556) were claimed through simplified billing.

1.7 Appendix 2 illustrates the Medicare bulk bill and patient claim process from the point the patient receives the service, noting the points of patient, provider and Human Services involvement.

1.8 In 1992, the Health Insurance Commission (now Medicare Master Program in Human Services) developed and implemented electronic claiming systems. In addition to a number of manual claiming options (in-person, dropbox, post and phone) Human Services currently offers eight electronic claiming channels (described in Chapter 2). Most of these channels were implemented ten or more years ago.

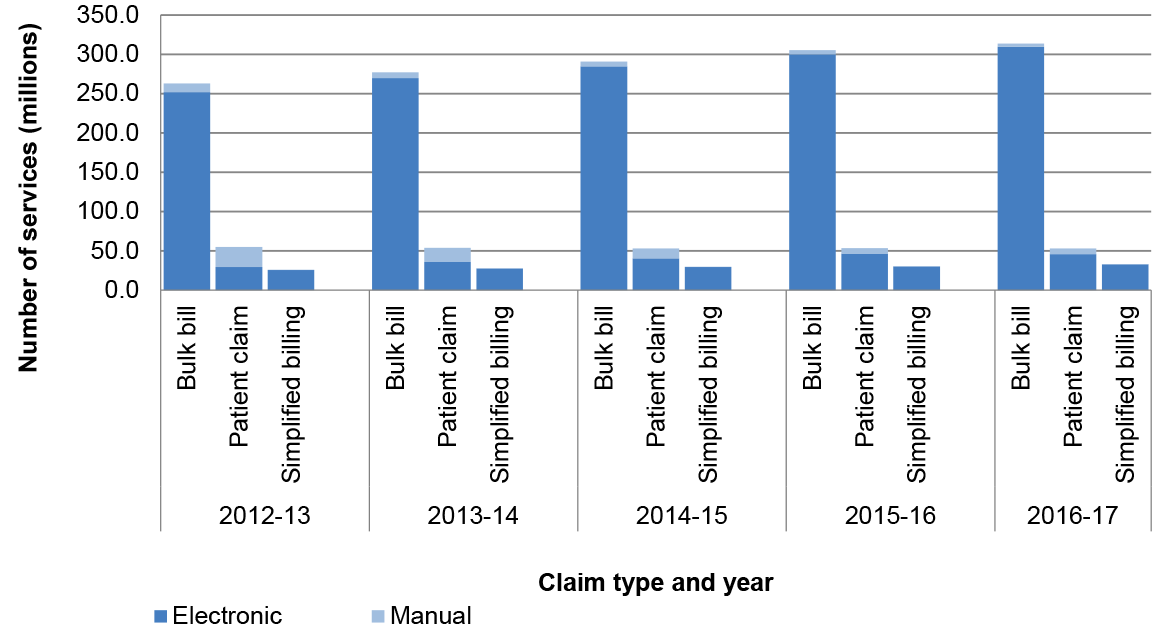

1.9 Figure 1.1 shows that most services are claimed under bulk billing arrangements and that electronic lodgement is the preferred method for all billing types. The figure also shows that the proportion of patient claim services lodged electronically has been more variable and has improved substantially over the last five years (see also Figure 2.1). Although patient claim services account for only around 13 per cent of all services claimed in 2016–17, it is reductions in manual lodgement of these claims that has most contributed to the department’s electronic claiming take-up rate in recent years.

Figure 1.1: Lodgement of claims for Medicare services by claim and transmission type, 2012–13 to 2016–17

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ Annual Reports (2012–13 to 2016–17).

Department of Human Services’ administrative roles and responsibilities

1.10 Human Services administers Medicare payments on behalf of the Department of Health. The Bilateral Head Agreement between the Secretaries of Human Services and the Department of Health sets out the governance framework and requirements for both departments.

1.11 Human Services administers the payment of Medicare benefits by:

- enrolling eligible Australians and visitors for Medicare and registering individuals and families for the Medicare Safety Net4;

- registering health practitioners (for Medicare provider numbers), accredited diagnostic imaging facilities and their equipment and, accredited pathology facilities;

- assessing eligibility for Medicare levy exemptions;

- assessing, approving and paying Medicare benefits (to patients, providers, Private Health Insurers and Billing Agents); and

- conducting patient compliance activities.5

Previous audit coverage

1.12 Previous ANAO audits relating to the administration of the Medicare program have included: audits of the accuracy of Medicare claims processing; the management of Medicare compliance audits; and the management and integrity of Medicare customer data.6

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

Audit objective and criteria

1.13 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of Medicare electronic claiming arrangements, including an assessment of the extent to which claiming and processing efficiencies for the Government, health professionals and Medicare customers have been achieved.

1.14 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Was effective planning undertaken for the implementation and ongoing delivery of Medicare electronic claiming channels?

- Has the implementation and ongoing delivery of Medicare electronic claiming channels been effective?

- Does Human Services monitor and evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness with which it delivers Medicare electronic claiming?

1.15 The scope of the audit included a review of the arrangements in place to manage risks to payment integrity but did not otherwise examine the accuracy of claims processing, compliance arrangements or the integrity of customer data.

Audit methodology

1.16 The audit’s methodology included:

- examination of documentation relating to the administration of Medicare electronic claiming channels, including program documentation and performance reports;

- review and analysis of departmental data related to the performance (take-up, costs/savings and timeliness) of the range of electronic channels currently available;

- ANAO analysis of quantitative data from Human Services’ ICT systems; and

- interviews with relevant departmental staff.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $432 100.

1.18 The team members for this audit were Tracy Cussen, Christine Preston, Hannah Climas, Fei Gao and Andrew Rodrigues.

2. Planning and strategy

Areas examined

This chapter identifies the objectives and anticipated benefits of implementing electronic claiming channels. It identifies the channels currently administered by the Department of Human Services and describes some of the mechanisms the department has in place to inform their understanding of channel user needs and experiences.

Conclusion

The objectives of introducing electronic claiming (to improve convenience and timeliness and reduce costs to Government and the health care sector) have been met through the introduction of a range of individual channels over time to allow claiming by different users. Human Services has mechanisms in place to identify issues and consider whether channels can be improved to meet user needs.

Have the objectives and intended benefits of electronic claiming been identified?

The Department of Human Services has identified the objectives and intended benefits of electronic claiming. The overall intent of introducing electronic claiming has been to increase the convenience to providers and patients, reduce costs to government and medical providers and improve the timeliness of claim processing. These objectives are consistent with Human Services’ Channel Strategy and Digital Transformation Strategy and its current strategy to deliver as close as possible to 100 per cent of electronic claiming at point of service.

Alignment with overarching strategies

2.1 Digital or electronic government service delivery is not a new concept. Since the late 1990s successive governments have made commitments7 to adopt online technologies to deliver services and improve business practices. Digital claiming of Medicare benefits is aligned with these commitments.

2.2 One of the objectives articulated in the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services or the department) Digital Transformation Strategy is to provide services that are ‘available digitally anywhere, anytime’. Key areas of focus under this strategy include: reducing demand on staff-assisted channels; migrating transactions to lower-cost channels; and complete end-to-end digitisation of processes.

Objectives and benefits of electronic claiming

2.3 A 2009 report8 identified that the Government’s overarching objectives in implementing Medicare electronic claiming were to:

- provide increased convenience to medical service providers and customers;

- provide cost savings for government and medical services providers; and

- improve the speed and quality of claims processing.9

2.4 Departmental documents from 2009 identified anticipated benefits from introducing electronic claiming including:

- reducing bulk bill paper claim form storage;

- enabling reconciliation of payments for bulk bill claims;

- improved customer service;

- reducing visits to Medicare offices;

- reducing the number of claims processing staff within Human Services;

- automating claims and payments processing; and

- reducing cheque payments to the public.

2.5 Table 2.1 indicates that most payments are made through Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) and that the department has reduced or ceased less cost effective payment types over time. The department was unable to provide estimated administrative savings from reductions in the number of claims processing staff attributable to the introduction of electronic claiming.

Table 2.1: Medicare services by payment type, 2012–13 to 2016–17

|

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|||||

|

|

Number of services (million) |

% |

Number of services (million) |

% |

Number of services (million) |

% |

Number of services (million) |

% |

Number of services (million) |

% |

|

Cash to claimanta |

1.7 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Cheque to health professionalb |

1.6 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Cheque to claimantc |

3.4 |

1.0 |

3.3 |

0.9 |

3.0 |

0.8 |

2.7 |

0.7 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

|

EFT to claimantc |

34.4 |

10.0 |

36.6 |

10.2 |

35.6 |

9.5 |

35.3 |

9.1 |

38.0 |

9.5 |

|

EFTPOS payment to claimant |

9.3 |

2.7 |

8.6 |

2.4 |

9.8 |

2.6 |

11.0 |

2.8 |

11.6 |

2.9 |

|

EFT to health professional |

261.4 |

76.0 |

276.8 |

77.3 |

290.6 |

77.8 |

305.2 |

78.4 |

313.6 |

78.5 |

|

Pay doctor via claimant cheque |

6.4 |

1.9 |

5.4 |

1.5 |

4.8 |

1.3 |

4.3 |

1.1 |

3.7 |

0.9 |

|

Payment to private health fund or billing agent |

25.8 |

7.5 |

27.5 |

7.7 |

29.6 |

7.9 |

30.5 |

7.8 |

32.9 |

8.2 |

|

Total servicesd |

344.0 |

|

358.3 |

|

373.4 |

|

389.1 |

|

399.5 |

|

Note a: Cash payments were phased out from 1 July 2012.

Note b: Payments by cheque to health professionals for bulk billing services ceased on 1 November 2012.

Note c: From 1 July 2016 payments by credit EFTPOS in service centres or by cheque, with the exception of Pay Doctor Via Claimant Cheques, ceased.

Note d: Totals may differ due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of the Department of Human Services’ Annual Reports (2012–13 to 2016–17).

2.6 In 2014, an internal Claiming and Payment Strategy business case was drafted to support ongoing activities to promote and strengthen electronic claiming. The business case outlined the department’s aim to create efficiencies for Government and reduce red tape for the health sector by:

- making it easier for the Australian public and health professionals to receive Medicare benefits through claiming channels that are efficient and easy to access; and

- creating savings for Government by transforming Medicare’s electronic claiming systems through new technology that provides efficiency and scalability for all claiming into the future.

2.7 In February 2015 this strategy was launched as the Medicare Digital Claiming Strategy10 and remains the current operational electronic claiming strategy. The objective underpinning this strategy is to maximise digital claiming for Medicare benefits at the point of service as this:

requires the least amount of effort for customers as no additional engagement is required with the department for patients to make a Medicare claim [and] involves the lowest processing cost for the department.

2.8 Human Services has focused on increasing electronic patient claiming rates in support of their overall strategy. The number of services claimed by patients annually has remained relatively consistent over the last five years with a decrease of around 2 million claims between 2012–13 and 2016–17. The proportion of patient claimed services lodged electronically has risen substantially over this time—from around 54 per cent of all patient claimed services in 2012–13 (29.6 million services) to 86.4 per cent (45.8 million services) in 2016–17.

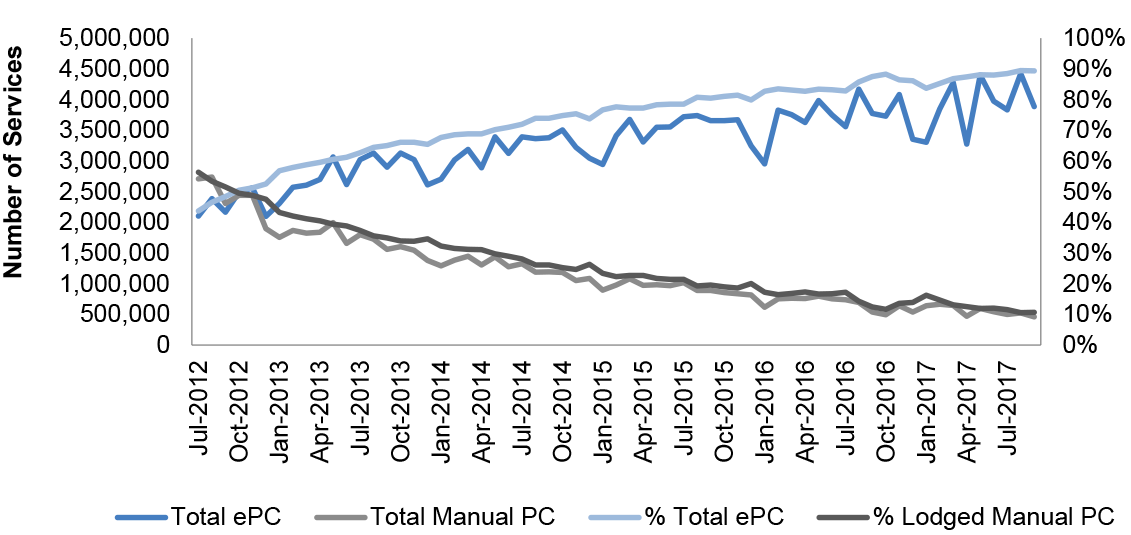

Figure 2.1: Patient claiming by lodgement type—electronic vs manual, 2012–2017

Note: References to PC and ePC in legend refer to Patient Claim and electronic Patient Claim.

Source: Department of Human Services’ administrative data.

Have channels been developed to meet the needs of the community, providers and government?

Electronic claiming channels have been developed to meet the needs of providers, patients and private health insurers, and to reduce manual processing for the department. The available channels allow claiming across the three claiming/billing methods and for the claims to be lodged at the point of service or at a time convenient to the claimant.

Human Services engages with peak stakeholder groups and providers to share information about business issues and consider improvements. The department measures channel usage and conducts analysis to identify health practices that continue to lodge manual claims. This data, along with the stakeholder feedback, is used by the department to target strategies to promote electronic claiming.

Channel coverage

2.9 Human Services’ documentation identifies that channel services were developed to: deliver payments in a timely, accurate and cost effective manner; ensure that intended recipients could easily access services; and provide an appropriate balance between convenience, reliability, security and efficiency in delivering payment services.

2.10 As noted in Chapter 1, the Medicare benefit is a patient benefit. If the provider agrees to accept the Medicare benefit as full payment for the service then the patient benefit becomes a ‘bulk bill’ claim and the health professional will claim the benefit directly from Human Services as full payment for the service. For services that are not bulk billed the patient pays the full fee charged11 for the service, and then claims the Medicate benefit through the practice submitting the claim electronically to Human Services on the patient’s behalf at the point of service or by using a self-service channel at a later time. For this reason claiming channels are required for both health care professionals and patients.

2.11 The channels are available across the three claiming/billing methods: bulk billing, patient claiming and simplified billing. The available channels also allow for the claim to be lodged at the point of service or in the recipient’s own time, depending on the circumstances (see Table 2.2).

Overview of electronic claiming channels

2.12 A number of current and historical drivers have impacted the development of claiming channels. These drivers include:

- the 1995 Private Health Insurance Reforms;

- the 2008 National eHealth Strategy;

- the 2010 Service Delivery Reform agenda;

- medical software vendors development of practice management software systems;

- electronic claiming development in other sectors (tax, private health insurance);

- consumer demand for electronic access;

- ICT investment decisions by health professionals; and

- the increased Government focus on reducing red tape for business.

2.13 Over time, electronic channels have evolved from systems that facilitate the lodgement of bulk billing claims by providers to systems that cater to a range of service settings (for example hospitals and medical practices) and those that allow patients to access claiming using digital channels.

2.14 There are currently eight electronic claiming channels: six of these channels facilitate point of service claiming by providers or patients and the remaining two patient channels facilitate claiming at the patient’s convenience. In addition, Human Services retains manual claiming options (in-person, dropbox, post and phone).

2.15 The Medicare electronic claiming options currently available are listed in Table 2.2. From these channels, collectively, around 388 million of the 399 million services (97.1 per cent) claimed in 2016–17 were lodged electronically. A breakdown of the volume and proportion of services claimed by individual channels is at Table 3.1.

Table 2.2: Current Medicare electronic claiming channels

|

How the claim is lodged |

Electronic claiming channel |

Channels details |

|

By the health professional at the point of service for both bulk bill and patient claims |

Medicare Online (2002) |

Supports claiming from doctor’s practices to Medicare via their practice management systems. There are approximately 300 vendors who have a Notice of Integration for online claiming which means their software is compatible with that used by Human Services. |

|

Medicare Easyclaim (2007) |

Allows practices to lodge claims using a secure EFTPOS network provided by five financial institutions contracted by Human Services. The Government pays the financial institutions 23 cents per successful transaction. |

|

|

Medicare Bulk Bill Webclaim (2015) |

Allows providers to lodge bulk bill claims using the Health Professionals Online Services (HPOS). |

|

|

Medicare Patient Claim Webclaim (2016) |

Allows providers to make claims on behalf of patients using the HPOS. |

|

|

By the patient after receiving an account (paid or unpaid) from the provider |

Claiming Medicare Benefits Online (CMBO) (2011) |

Allows patients to claim 23 of the most common MBS items over the internet. Claimants must register for a Medicare online account through myGov and are required to provide an image of the receipt. These claims are processed manually. |

|

Express Plus Medicare Mobile App (2013) |

Claimants must register for a Medicare online account through myGov and are required to provide an image of the receipt. These claims are processed manually. |

|

|

By hospitals, billing agents and providers for in-patient medical services where there is a Medicare and private health insurer component |

Electronic Claim Lodgement and Information Processing Service Environment, (ECLIPSE) (2004) |

Used for claiming Simplified Billing services. |

|

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) (1999) |

Used for claims lodged via email for claiming services provided in hospitals involving private health insurers paid directly to a provider, usually by EFT. |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ documentation.

2.16 Although there is some overlap in the coverage of the electronic claiming channels (by claimant group and billing type) each was introduced to promote different efficiency objectives or to target different stakeholder groups:

- Medicare Online was introduced in 2002 as part of business improvement initiatives aimed at modernising claiming and payment processing.

- ECLIPSE, introduced in 2004, was developed to streamline the claims process for in-hospital patients covered by both Medicare and a private health fund.

- Easyclaim was introduced in 2007 as an alternative to Medicare Online, which at the time was seen to be a costly and ‘cumbersome’ channel. Easyclaim was designed to provide real time approval of claims and payments using EFTPOS technology.

- CMBO was introduced in 2011 to provide an alternative electronic claiming channel for claimants who could not, or choose not to, use claiming at point of service.

- The Express Plus Medicare Mobile App was introduced in 2013 to use new technologies and was developed in line with the Human Services’ introduction of Mobile App services to support Centrelink programs.

- Bulk Bill Webclaim and Patient Claim Webclaim, introduced in 2015 and 2016 respectively, were implemented, in part, to provide a free electronic claiming option in response to complaints from providers regarding the cost of purchasing practice management software to enable digital online claiming using other channels.

2.17 A 2014 discussion paper prepared within Human Services identified Medicare Online as ‘the gold standard claiming channel for the Department due to its simplicity for both providers and customers and high levels of program integrity for the department’ despite being the oldest claiming channel (aside from SMTP).

2.18 Providers can choose which channel they use, depending on their circumstances. Their choice may be influenced by the requirements established by Human Services to use electronic claiming which differ by channel. For example, use of both Medicare Online and ECLIPSE requires providers to purchase integrated practice management software and to comply with authentication and security requirements.12 For patients to use CMBO they must register for a Medicare online account, including providing bank account details, and link this account with myGov. For providers to use Easyclaim they must have an EFTPOS terminal provided by one of the five financial institutions contracted by Human Services to provide Easyclaim services.

Understanding user needs

2.19 Human Services engages with peak stakeholder groups and providers to support the ongoing management of channels. These forums provide opportunities to share information about business issues and consider improvements and have been effective in identifying barriers to stakeholder take-up of electronic claiming channels.13 The key engagement mechanisms are:

- Stakeholder Consultative Group—with representation from peak provider groups14;

- ECLIPSE Reference Group—with private health insurance industry representatives;

- Financial institutions—those under contract with Human Services to deliver Easyclaim services; and

- Outreach networks—Business Development Officers and Medical Liaison Officers that provide support to practices, providers and Aboriginal Medical Services.

Outreach networks

2.20 Human Services’ Business Development Officers (BDOs)15 undertake activities based on identified business priorities and the strategic direction of the department. To promote electronic claiming their role is broadly focused on educating health professionals about the range of electronic services available and how these services can reduce provider administrative costs and increase the timeliness of payments. The information gathered can then be used by Human Services to identify improvements or business process enhancements required for existing channels16 and in the development of new channels.

2.21 Departmental documentation reviewed by the ANAO indicates that, from 2012 through 2017, BDOs engaged providers, in-person or over the phone, to understand barriers to the take-up of electronic claiming and to discuss a range of business process enhancements. The impact of the strategies employed by BDO’s is discussed further in Chapter 3.

2.22 Human Services has identified that the barriers to stakeholders using electronic claiming are both cultural and system-based. The top five barriers to electronic claiming are:

- lack of knowledge of electronic claiming options;

- knowledge gaps in using practice management software;

- investment and upkeep of practice management software;

- understanding the Medicare Benefit Schedule and complexities associated with claim scenarios/items that can be claimed by channel; and

- patients not registering for a Medicare online account or failing to provide their bank details to the department.

2.23 The actions taken by the department to address these barriers include: educating practice staff and the public about electronic claiming availability and processes; discussing software-related issues with software vendors; making enhancements or amendments to system and business rules to improve functionality (see for example the discussion of the Reduction in Manual Intervention project from paragraph 3.64); and developing web-based claiming channels (Bulk Bill and Patient Claim Webclaim) that do not require investment in practice management software.

2.24 Human Services has also undertaken analysis to identify providers/practices that do not use or under-use electronic claiming. Several targeted strategies have been launched to promote the take-up of electronic claiming by these users. These are described in Chapter 3 from paragraph 3.16.

3. Implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Human Services’ delivery of electronic claiming objectives: improving access; providing savings/reducing costs for the department, practitioners and patients; and improving claim processing and payment timeliness.

Conclusion

The introduction of electronic claiming channels has led to improved access to payments for the community and providers. More than 97 per cent of claims for Medicare services are lodged electronically and a majority of these are paid within one day of lodgement.

The ANAO reviewed the available data related to expected savings and costs from implementing electronic claiming channels. These expected savings were only estimated by Human Services in some cases. Where estimates were made either take-up rates or dollar savings have not been achieved.

Although the department monitors rates of electronic lodgement and tracks movements between channels by claim type and reductions in manual services, the long term benefits and relative efficiencies from introducing individual channels are largely unknown.

Has electronic claiming improved the ease of access to payments for the community and providers?

The high level of provider and patient take-up of electronic claiming (with 97.1 per cent of claims for services lodged electronically at the point of service) reflects the convenience, accessibility and timeliness of electronic claiming.

Efforts undertaken by Human Services to increase electronic patient claiming rates for services provided by general practitioners and specialists have been successful albeit there is scope to improve claiming rates for other practitioners, in particular pathologists, although increasing the number of pathology claims lodged at the point of service may require adjustments to the legislative framework. Patient claims account for less than two per cent of all claimed pathology services but around 20 per cent of all patient claims lodged manually.

3.1 Electronic claiming provides an alternative way to claim Medicare payments to either visiting Medicare offices or posting claim forms. The convenience of lodging electronic claims for both providers and patients is evident. In 2016–17:

- 97.1 per cent of claims for services were lodged at the point of service;

- 2.9 per cent (around 11 million services) of claims were submitted manually; and

- 0.03 per cent of claims were lodged electronically, but not at the point of service.

3.2 Electronic claiming facilitates more timely payment of benefits (discussed further from paragraph 3.55). Medicare Online uses the bank account details provided by the patient to deposit their Medicare rebate into their bank account. Payment is generally received within two to three working days. Around 83 per cent (around 322 million) of all claims for services are lodged through this channel. Medicare Easyclaim provides a more immediate transfer of funds to the customer through the EFTPOS network. Easyclaim was used to lodge around eight per cent (around 32 million) of all claims for services in 2016–17.

Take-up of electronic claiming

3.3 The overall take-up of electronic claiming is high but there are marked differences in the use of each of the channels. Table 3.1 shows the proportion and volume of services lodged from seven of the current electronic claiming channels17 for the previous two financial years. The most widely used channel is Medicare Online which, on a monthly basis, is used by around half of all medical practices and was used to lodge around 83 per cent of all electronic claims in 2016–17 (92 per cent of electronic bulk bill claims and 64 per cent of electronic patient claims). For Simplified Billing claims, Electronic Claim Lodgement and Information Processing Service Environment (ECLIPSE) is the most commonly used channel (85 per cent of electronic claims).

Table 3.1: Volume of services by claiming channel in 2015–16 and 2016–17

|

Channel |

Type of claim |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

||

|

|

|

Proportion of paid services (%) |

Volume of paid services (million) |

Proportion of paid services (%) |

Volume of paid services (million) |

|

Medicare Online |

Bulk Bill or patient |

80 |

312 |

81 |

322.3 |

|

Medicare Easyclaim |

Bulk Bill or patient |

8 |

31.1 |

8 |

31.9 |

|

Bulk Bill Webclaima |

Bulk Bill |

0.07 |

0.27 |

0.21 |

0.82 |

|

Patient Claim Webclaima |

Patient |

n/a |

n/a |

0.01 |

0.04 |

|

ECLIPSE |

Simplified Billing |

6.2 |

24.4 |

7.0 |

28.0 |

|

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) |

Simplified Billing |

1.5 |

6 |

1.2 |

4.8 |

|

Claiming Medicare Benefits Online (CMBO) |

Patient |

0.05 |

0.2 |

0.03 |

0.13 |

Note a: Both Bulk Bill and Patient Claim Webclaim are less established channels having been introduced in June 2015 and August 2016 respectively. See also Table 2.2 for the date each of the channels was introduced.

Source: Department of Human Services’ documentation.

3.4 The point of access to each of the eight available electronic channels differs as do the MBS service item numbers that can be claimed:

- Claims can be made at the point of service through Medicare Online, Easyclaim and the Bulk Bill/Patient Claim Webclaim channels at practices that have electronic claiming capability.

- In-hospital services can be claimed by providers and billing agents through ECLIPSE or SMTP.

- Patients can claim from any location providing access to the internet/wifi using CMBO or the Express Plus Medicare Mobile App.

- Both Easyclaim and CMBO have restrictions on the MBS items that can be claimed from those channels. All other channels accept claims for all MBS items.

3.5 When patient claims are lodged at the point of service, the patient’s claim is lodged by the provider on behalf of the customer, improving convenience to the customer. In 2016–17, 86 per cent of patient claims were lodged at point of service. Additionally, 98.7 per cent of bulk bill claims and 99.5 per cent of simplified billing claims were lodged at point of service.

Take-up by practices and provider type

3.6 Medical practices may lodge claims from multiple channels. In June 2017, 43 066 medical practices lodged claims for 34 625 336 Medicare services. Claims for more than 97 per cent of these services (around 33.8 million) were lodged electronically from 37 529 practices. 21 832 practices provided services (around 843 000) for which claims were lodged manually. Table 3.2 shows the number of practices lodging claims for services in June 2017 by lodgement channel and billing type.

Table 3.2: Medicare services claim transmission as at June 2017

|

|

Bulk billing |

Simplified billing |

Patient claiming |

|

Electronic (SMTP) |

0 |

5770 |

0 |

|

HPOS |

2294 |

0 |

299 |

|

Medicare Online |

19 065 |

0 |

13 917 |

|

Medicare Easyclaim |

10 927 |

0 |

8650 |

|

ECLIPSE |

0 |

7806 |

0 |

|

Claiming Medicare Benefits Online |

0 |

0 |

3377 |

|

Scanned |

1414 |

0 |

0 |

|

Manual |

1204 |

305 |

20 486 |

|

Total practicesa |

31 481 |

8798 |

28 552 |

|

Electronic transmitting sites for Medicare Online and Easyclaim |

|||

|

Total no. of transmitting Medicare Online sites |

22 006 |

||

|

Total no. of transmitting Medicare Easyclaim sites |

15 871 |

||

|

Total no. of transmitting HPOS sites |

2435 |

||

|

Total no. of transmitting Electronic sites (Medicare Online +/or Easyclaim) |

33 493 |

||

Note a: Totals do not sum as practices may use multiple claim transmission methods.

Source: Department of Human Services’ administrative data.

3.7 The proportion of patient claimed and bulk bill services lodged electronically varies by provider type. The data shows that all provider types are most likely to bulk bill electronically. However, as bulk billing is the most common claiming type by volume, the number of manual bulk bill claims remains high and represents more than 35 per cent of all manually lodged claims.

3.8 A majority of patient claim services are also lodged electronically by general practitioners, specialists and other providers, but not by pathologists. Only two per cent of pathology claims are patient claims with almost 93 per cent of these claims lodged manually (see Table 3.3).

3.9 Human Services advised that pathology claims are often more complex than other claims and that while current legislation does not prevent a pathologist from electronically lodging a patient claim18, knowledge of processes and software limitations have been identified by providers as barriers to electronic lodgement during consultations with Human Services Business Development Officers (BDOs). In 2015, Human Services commenced discussions with peak pathology organisations to discuss these barriers. Human Services data indicates that electronically lodged patient claiming by pathologists rose from one per cent in 2013–14 to 5.2 per cent in 2015–16 and 7.2 per cent in 2016–17.

Table 3.3: Medicare services processed by provider type and lodgement method, 2016–17

|

|

Bulk bill |

Patient claim |

||||||

|

|

Electronic |

Manual |

Electronic |

Manual |

||||

|

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

General Practitioner |

136 053 120 |

98.1 |

2 602 428 |

1.9 |

20 748 777 |

95.7 |

927 859 |

4.3 |

|

Specialist |

64 770 549 |

98.8 |

784 347 |

1.2 |

19 958 411 |

85.4 |

3 422 059 |

14.6 |

|

Pathologist |

84 150 884 |

100 |

25 792 |

0.0 |

113 027 |

7.2 |

1 461 225 |

92.8 |

|

All other providersa |

24 546 245 |

97.4 |

642 687 |

2.6 |

4 942 571 |

78 |

1 395 038 |

22 |

|

Total |

309 520 798 |

98.7 |

4 055 254 |

1.3 |

45 762 786 |

86.4 |

7 206 181 |

13.6 |

Note a: All other providers includes optometrists, dentists/orthodontists, other practitioners and new providers (not yet classified with a major speciality by Human Services).

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ administrative data.

3.10 ANAO analysis of jurisdictional data shows some differences in access to bulk bill services by state/territory and nationally by Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Structure classifications.19 In 2016–17, more than 94 per cent of all services and more than 82 per cent of all patient claim services are claimed electronically at the point of service in each state and territory. However there were variations in the proportion of electronic patient claims for services claimed at point of service by state, with New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory having the lowest proportions at 82 per cent of services, and South Australia having the highest proportion at 95 per cent of services.

3.11 Data on claiming by region (see Table 3.4) shows that very remote and remote Australian regions have the highest proportion of point of service claiming, with 96 per cent of patient claims for services claimed at point of service in these areas. Major cities of Australia were the region with the lowest level of point of service, with 85 per cent of patient claims for services being made at point of service. These regional differences are due in part to higher proportions of bulk bill claiming in remote (87 per cent) and very remote areas (94 per cent) compared to other regions. Almost all providers who bulk bill use electronic services which will then be available for the practice to lodge the claim on behalf of the patient.

Table 3.4: Proportion of claims for patient services claimed at point of service by Australian Region in 2016–17

|

Australian region |

Proportion of claims for patient services claimed at point of service (%) |

|

Inner Regional Australia |

92 |

|

Major Cities of Australia |

85 |

|

Outer Regional Australia |

90 |

|

Remote Australia |

96 |

|

Very Remote Australia |

96 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ data.

Human Services’ initiatives to increase take-up of Medicare electronic claiming

3.12 Since 2015, several strategies have been used by Human Services BDOs to achieve as close to 100 per cent electronic claiming at the point of service as possible. Human Services uses analysis of claiming trends by practices and provider types to target practices with high volumes of manual patient claiming.

3.13 Human Services’ data demonstrates increases in electronic patient claiming rates since these strategies commenced. Overall, in December 2014, around 31 per cent of practices lodged 100 per cent of their claims electronically and by May 2017 this proportion had risen to around 45 per cent (see Table 3.5).

Table 3.5: Practices transmitting Medicare services electronically December 2014, May 2016 and May 2017

|

|

December 2014a |

May 2016 |

May 2017 |

|||

|

|

Number of practices |

Proportion of total practices (%) |

Number of practices |

Proportion of total practices (%) |

Number of practices |

Proportion of total practices (%) |

|

‘zero’ electronic practices |

9000 |

23 |

7751 |

18.3 |

6182 |

14.1 |

|

‘some’ electronic practices |

18 000 |

46 |

18 427 |

43.5 |

17 992 |

41.2 |

|

100 per cent electronic practices |

12 000 |

31 |

16 193 |

38.2 |

19 544 |

44.7 |

|

Total practices |

39 000 |

100 |

42 371 |

100 |

43 718 |

100 |

|

Practices transmitting electronically |

30 000 |

77 |

34 620 |

81.7 |

37 536 |

85.9 |

Note a: December 2014 figures are rounded.

Source: Department of Human Services’ administrative data.

3.14 Human Services data also demonstrates improvements for targeted provider types, for example:

- from January to June 2015 targeted practices increased electronic patient claiming by four per cent, while the increase in non-targeted sites was only 1.1 per cent; and

- electronic patient claiming in target sites rose from 44.3 per cent in December 2015 to 68.1 per cent in April 2017.

3.15 Targeting of specialists (by BDOs) led to growth in electronic claiming from around 21 per cent in 2012 to around 85 per cent in 2017 (see Table 3.6).

Table 3.6: Practices transmitting patient claims electronically, March 2012, 2016 and 2017

|

Patient point of service claims |

FYTD ending |

FYTD ending |

FYTD ending |

Increase |

||||

|

|

number |

% |

number |

% |

number |

%

|

number |

% |

|

Totala |

14 859 033 |

34.8 |

32 229 192 |

81.3 |

34 113 693 |

85.9

|

19 254 660 |

51.1 |

|

by General Practitionersb |

10 205 002 |

55.0 |

15 843 739 |

93.8 |

15 674 641 |

95.5 |

5 469 639 |

40.5 |

|

by Specialistsb |

3 712 646 |

21.2 |

13 566 128 |

78.4 |

14 842 231 |

84.7 |

11 129 585 |

63.5 |

Note a: Total includes claims submitted by all providers. Percentage refers to proportion of claims that were patient claims.

Note b: Percentages refer to the proportion of electronic claims submitted by the relevant provider type.

Source: Department of Human Services’ documentation.

3.16 Human Services has developed several new strategies to support engagement by BDOs to increase point of service claiming. Business proposals indicate that these strategies will target different cohorts not covered by previous strategies and are intended to provide education and support to transition to the most appropriate digital channel. These strategies, which commenced in 2017, are:

- Allied Health Engagement Strategy;

- Manual to Digital Bulk Bill transition; and

- Digital Claims Realisation 1 and 2.

3.17 To support these strategies Human Services undertook analysis of claiming trends. That analysis identified that allied health providers submitted 98 357 manual patient claims in November 2016, around 25 per cent of all patient claims for this group and around 13 per cent of the total manual claims for all groups and claiming channels over the timeframe. Further analysis conducted by Human Services identified that dentists/orthodontists submit a majority of their claims manually and have therefore been included as a target group in the Allied Health Engagement Strategy.

3.18 The Manual to Digital Bulk Bill transition strategy focuses on practices that continue to exclusively lodge claims manually. When developing the strategy the department identified that in the month of October 2016, 4561 practices were lodging manual bulk bill claims and of these, 2754 (60 per cent) lodged only manual bulk bill claims.

3.19 Finally, the Digital Claims Realisation strategies (DCRS 1 and 2) will involve BDOs, data analysis, and reporting. DCRS 1 will involve practices that submitted 100 or more manual patient claims in March 2017 and DCRS 2 will engage practices who submitted 50–99 manual patient claims. These sites are primarily comprised of specialists and some general practitioners.

3.20 These strategies are in addition to government and departmental strategies undertaken over the years to promote electronic claiming, including subsidies and the removal of cash and cheque payment services (see Appendix 3).

Have the costs and savings from delivering electronic claiming been realised and tracked over time?

Given that Human Services has achieved 97.1 per cent electronic claiming at an aggregate level it is expected that savings to the department have been realised overall. The costs associated with introducing and maintaining these electronic claiming channels have not been tracked over time and the expected savings from introducing individual channels have not been realised within anticipated timeframes.

Anticipated savings for each channel have been estimated using standard assumptions of the price differential between manual and electronic claiming and projected channel take-up rates. The department has consistently overestimated the take-up rates when introducing new channels and has not followed up to determine whether the cost savings for individual channels have been met.

Human Services does not currently track the relative costs of maintaining each claiming channel. There would be benefit in Human Services developing the capability to better understand the costs of each channel, as well as the administrative savings and other benefits that have been realised, to support decisions about future directions for, and investments in, electronic claiming.

3.21 One of the objectives of introducing electronic claiming is to achieve cost and administrative savings for government (as discussed previously in paragraph 2.3). These savings can be achieved through reductions in manual claims processing, including efficiencies gained from reducing points of contact between the department, providers and patients.

3.22 It is likely that, at an aggregate level, the department has realised administrative savings. Between 2002–03, when Medicare Online was first introduced, and 2016–17, the number of claims for services lodged manually reduced from 98.4 million to 11.4 million. This reduction has occurred alongside an overall increase of 178.1 million services claimed over this time period. The uptake of electronic claiming also occurred against a backdrop of greater access to information technology and communications infrastructure.

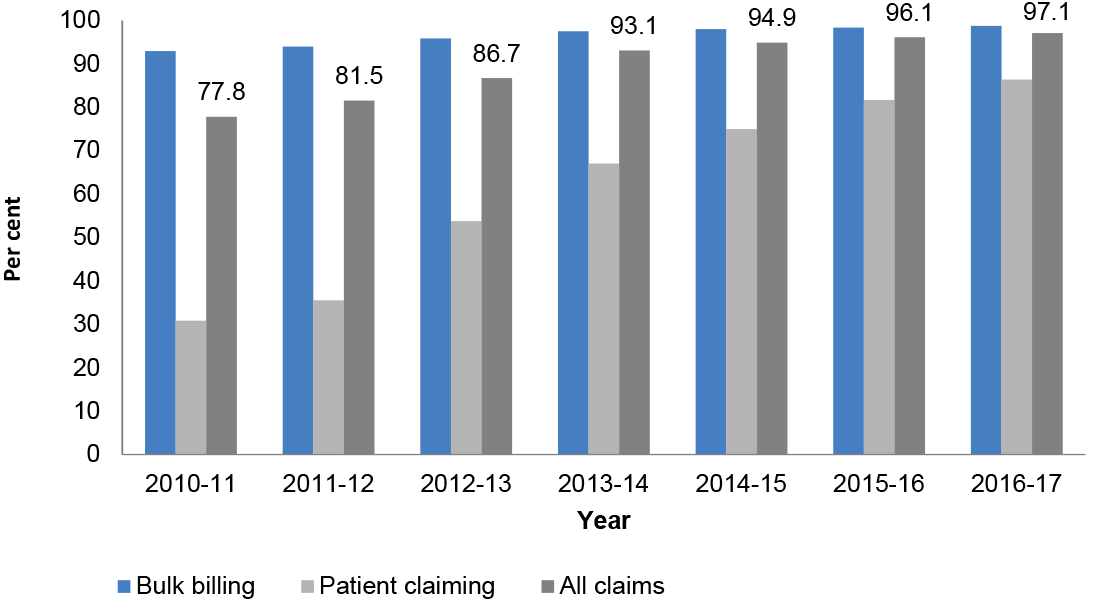

3.23 A review of Medicare electronic claiming undertaken by the department in 2009 stated that the take-up of electronic claiming had, to date, not been sufficient to realise savings and that it was unlikely to achieve a return on the investments until 2010–11 when it expected take-up in the order of 30 per cent for patient claiming and 93 per cent for bulk billing. These take-up rates were achieved within this timeframe as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Percentage of Medicare claims lodged electronically 2010–11 to 2016–17

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ Annual Reports (2010–11 to 2016–17).

3.24 When introducing individual channels Human Services has consistently over-estimated take-up rates, and under-estimated implementation challenges. Some of the increase in take-up of individual channels likely represents a shift between electronic channels in addition to a shift from manual to electronic claim lodgement. These factors have contributed to anticipated savings for individual channels not being achieved in the timeframes originally planned.

Savings and other benefits from individual claiming channels

3.25 For the three oldest current channels: Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) (implemented in 1999), Medicare Online (implemented in 2002); and ECLIPSE (implemented in 2004), Human Services was unable to provide documentation which identified the intended objectives and savings expected from these claiming channels. Human Services also advised that documentation was not developed to support the implementation of the Express Plus Medicare Mobile App in 2013. For those electronic claiming channels for which documentation has been available, the ANAO has assessed whether the expected savings from claiming channels were identified and have been achieved.

Webclaim

3.26 Bulk Bill Webclaim, and Patient Claim Webclaim, implemented in 2015 and 2016 respectively, are Human Services’ two most recently implemented claiming channels. The key objective of the Webclaim channels was to deliver a lower cost option via the existing Health Professional Online Services to those practices for whom implementing a vendor product is not financially viable.

3.27 The sole measure of success for the Bulk Bill Webclaim program was identified in internal documentation to be the delivery of savings which were originally (in February 2014) estimated to be around $22.3 million and later re-forecasted by Human Services to be around $10.8 million in late 2015.

3.28 A separate estimate of the regulatory impact of implementing Bulk Bill Webclaim was undertaken by the department in 2015. The estimated regulatory saving of $16.8 million annually for health providers was based on reductions in compliance costs from moving from paper-based to online claiming. This estimated saving was reported in the Government’s Annual Red Tape Reduction Report 2015.

3.29 Following the implementation of Bulk Bill Webclaim, Human Services internally reported in its project closure report that the project delivered all in-scope items and successfully met its objectives. The closure report highlighted that the implementation of the project had achieved savings however the value of these savings were not quantified. Subsequent information provided by the department identified that a number of factors affected full benefits realisation for the introduction and use of Bulk Bill Webclaim. Human Services advised that these factors included legal concerns expressed by software vendors and delays in system development that impacted the launch of the channel.

3.30 Patient Claim Webclaim was introduced as part of a suite of initiatives that formed the ‘Increasing Digital Health Transactions’ strategy, aimed at increasing the volume of digital claiming. Human Services projected that administrative savings to the department resulting from these initiatives would be $81 million over four years commencing in 2015–16. Internal Human Services documentation did not clearly specify whether these projected savings were expected solely from the implementation of the channel or from other initiatives included in the proposal. The expected savings, whether from the channel or from the suite of initiatives, were to be driven by an overall reduction in the remaining manual patient claim services. These reductions were over-estimated.

3.31 Table 3.7 shows the expected take-up rate and savings projected by Human Services as part of costing the Increasing Digital Health Transactions strategy. The projected savings for the strategy from 2015–16 to 2018–19 was based on a flawed methodology. The projected patient claim service figures were based on 2013–14 data and did not account for the downward trend in manual transactions already occurring. The fact that the projected take-up was for electronic claiming as a whole, rather than for the new channel, also meant that the benefits from introducing Patient Claim Webclaim would be less clearly known. In addition, the savings were calculated by multiplying the expected volume of new electronic claims by $1.61 per claim. This value was used by Human Services as the assumed cost differential between processing manual claims and electronic claims.

Table 3.7: Expected uptake and savings from Patient Claim Webclaim 2015–16 to 2018–19

|

Number |

2015-16 |

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

Total |

|

Projected Manual Patient Claim Services |

17 755 824 |

17 755 824 |

17 755 824 |

17 755 824 |

|

|

Potential uptake of electronic claiming |

7 102 330 |

11 718 844 |

14 559 776 |

17 045 591 |

|

|

Remaining Manual Patient Claim Services |

10 653 494 |

6 036 980 |

3 196 048 |

710 233 |

|

|

Calculated savings |

$11 434 751 |

$18 867 339 |

$23 441 239 |

$27 443 402 |

$81 186 730 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ documentation.

3.32 The Patient Claim Webclaim channel was implemented on August 2016, two months later than initially indicated in the project management plan. In 2016–17, 43 725 claims were made using Patient Claim Webclaim.

3.33 Following the implementation of Patient Claim Webclaim Human Services internally reported in its project closure report that the project delivered all in-scope items and successfully met its objectives. The closure report identified that no direct savings were associated with the introduction of Patient Claim Webclaim.

Claiming Medicare Benefits Online

3.34 The objective of Claiming Medicare Benefits Online (CMBO) was to support the take-up of electronic Medicare claiming by developing and implementing an alternative, home-based, electronic channel for members of the public who either do not have the opportunity, or choose not to, use point of service claiming. The CMBO channel was also intended to reduce the manual channel servicing costs within the portfolio and generate savings of $6.6 million over four years. These savings were calculated based on the estimated take-up of CMBO claiming over the four year period multiplied by the unit price per claim of $1.61.

3.35 While the implementation of CMBO achieved its objective of providing an internet-based Medicare claiming solution, lower than expected take-up rates have resulted in expected savings not being achieved. In addition changes made to the delivery of the channel, to mitigate identified compliance risks (see paragraph 4.28), have led to all claims for this channel now being manually processed, making the channel less efficient that initially intended.

3.36 During its first year of implementation, CMBO exceeded its expected take-up rate by nearly 9000 claims; however, the increase in take-up in subsequent years was far below projections. Table 3.8 shows the expected and actual take-up and savings for Claiming Medicare Benefits Online.

Table 3.8: Projected and actual claim rate and savings for the Claiming Medicare Benefits Online channel, 2011–12 to 2014–15

|

Financial year |

Expected Take-up |

Projected claim rate |

Projected savings |

Actual claim ratea |

Estimated savingsb |

|

2011–12 |

0.2% |

124 228 |

$200 007 |

133 000 |

$214 130 |

|

2012–13 |

0.5% |

424 430 |

$683 332 |

211 200 |

$340 032 |

|

2013–14 |

2.0% |

1 531 249 |

$2 465 310 |

251 500 |

$404 915 |

|

2014–15 |

3.3% |

2 018 546 |

$3 249 859 |

352 400 |

$567 364 |

|

Total |

|

4 098 453 |

$6 598 508 |

948 100 |

$1 526 441 |

Note a: The actual claim rate has been determined using figures reported in Human Services’ Annual Reports.

Note b: The estimated savings have been calculated by multiplying the actual claim rate by the unit price of $1.61 which is the assumed price used by Human Services since 2011.

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ documentation.

3.37 The lower than expected take-up of CMBO was noted in Human Services’ internal project management reporting. Human Services identified that the projected uptake was impacted by limits deliberately placed on the number of eligible items that could be claimed through CMBO. The department noted that remedial action to address CMBO claiming rates would require promotion of the claiming option to the general public. This action was not considered a priority for the department however because it was focused on encouraging point of service claiming. The actual take-up of CMBO as a proportion of total patient claiming at 30 June 2017 was 0.2 per cent, the same as that projected in 2011–12.

3.38 To further strengthen controls to prevent fraud, the automatic payment of claims made using CMBO were ceased and from 31 January 2016 onwards, claims lodged using CMBO were processed manually rather than automatically. This channel has daily and monthly cash limits. Manual intervention allows Human Services to ensure the claiming limit has not been exceeded prior to releasing payment. This move from automatic processing to manual processing for CMBO claims means that the level of ongoing savings initially expected from shifting from manual claiming to electronic claiming through the implementation of the CMBO channel have not been realised.

Easyclaim

3.39 The objective of Easyclaim was to improve doctor and patient convenience by providing faster access to Medicare benefits, reducing paperwork and removing the need for patients to visit Medicare offices to claim benefits. Easyclaim was also intended to improve the administrative efficiency of the Medicare claiming and payment system generating cumulative gross savings of $76.88 million by June 2009 for the department. The savings were estimated based on an expected claiming take-up rate of 70 per cent, equating to an expected 250 million Easyclaim claims being achieved by June 2009. The actual take-up of Easyclaim was much lower than expected. In 2008–09 only six million Medicare claims (five per cent of total claims) were made using the Easyclaim channel. The lower than expected take-up resulted in a shortfall in projected savings for the period from 2006–07 to 2008–09 of $24.7 million. As shown in Table 3, the take-up of Easyclaim has remained significantly lower than the 70 per cent of total claims expected—with Easyclaim claims having plateaued at approximately eight per cent of total claims since 2014–15.

Table 3.9: Volume of Easyclaim claims as a proportion of total Medicare claims between 2007–08 and 2016–17

|

Financial Year |

Volume of Easyclaim claims (millions) |

Easyclaim claims as a percentage of total claims (%) |

|

2007–08 |

1.13 |

0.4 |

|

2008–09 |

6.00 |

2 |

|

2009–10 |

14.90 |

5 |

|

2010–11 |

20.70 |

6 |

|

2011–12 |

24.00 |

7 |

|

2012–13 |

25.00 |

7 |

|

2013–14 |

24.60 |

7 |

|

2014–15 |

29.10 |

8 |

|

2015–16 |

31.10 |

8 |

|

2016–17 |

31.9 |

8 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Human Services’ Annual Reports (2007–08 to 2016–17).

3.40 Since inception a transaction fee of 23 cents has been paid by the government to financial institutions for each successfully delivered Easyclaim transaction, which currently equates to $6.6 million per year. The transaction fee was initially intended as an incentive to attract as many financial institutions as possible to participate in the channel, with the expectation that the Easyclaim channel would eventually replace the Medicare Online channel. The transaction fee was determined on the assumption that if the expected claim take-up was achieved within the first two years, the upfront development and testing costs incurred by acquiring financial institutions would be recovered. The lower than expected take-up of Easyclaim impacted on financial institutions’ ability to recover the cost of their investments.

3.41 Schedule one of the contracts between Human Services and the five financial institutions contracted to deliver Easyclaim services require the institutions to perform certain activities as part of the transmission of a successful transaction. The Human Services’ ICT Service Level Agreement (SLA) for Medicare Easyclaim covers arrangements between the ICT and Business branches for the provision of the Medicare Easyclaim ICT Business Service and sets the standards that financial institutions have to meet (for example, service availability targets and service response time targets). The department advised that ongoing maintenance costs were expected to be borne by the financial institutions.

3.42 Human Services was required, in accordance with the agreement between the department and financial institutions providing Easyclaim services, to review and make a decision on whether to continue or alter the transaction fees paid to financial institutions for the period beyond 1 July 2010 to 2015, and later for the period beyond July 2015. The result from both reviews was a decision to maintain the 23 cent fee.20

3.43 The 2014 Transaction Fee Review of Medicare Easyclaim found that in comparison to other electronic channels, Medicare Easyclaim was expensive and had no real development capacity for more complex claiming processes due to the limitations of the EFTPOS network. The review also identified that the department had planned to conduct an assessment of the Easyclaim channel to consider costs, convenience to users and the flexibility to respond to developments in health policy. The review recommended that both the decision as to whether to make changes to the 23 cent transaction fee and more broadly review Easyclaim should be deferred due to a 2014–15 Budget announcement that the market testing of a commercially integrated health payment system was to commence.

3.44 The proposed market testing of the new health payment system did not negate the need for a review of Human Services’ administration of the Medicare Easyclaim channel. The planned assessment to consider costs, convenience to users, and whether Easyclaim has the flexibility to respond to developments to health policy was still warranted. In any case, the proposed market testing announced as part of the 2014–15 Budget did not eventuate.

3.45 In May 2017, Human Services briefed its Minister on the department’s intention to commission an external review of the financial arrangements for the Easyclaim service. The brief identified that there was significant cost to the department from reconciling held payments lodged through Medicare Online. Payments are held when a provider or patient has failed to provide or update their bank account details. The brief identified that a benefit of Easyclaim over Medicare Online is that there are no held payments. The brief outlined that the review of the financial arrangements for Easyclaim would quantify the benefit of this channel, especially in relation to the issue of reconciling held payments.

3.46 The draft review focused on the Easyclaim financial arrangements and determining the impact of removing or changing the transaction fee. The review did not quantify the benefits of Easyclaim in relation to the issue identified in paragraph 3.45. Rather, it identified that the cost to the department in providing Medicare Online cannot currently be easily quantified as resources to deliver the channel are shared across multiple services, making accurate cost allocation difficult. The review concluded that while the transaction fee may be appropriate in the context of the department’s electronic claiming policy, the department’s alternative electronic claiming channels are provided at a lower cost to the department than Easyclaim and so Easyclaim does not represent the most efficient means by which the department can provide digital payment services in its current format.