Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Verifying Identity in the Citizenship Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s identity verification arrangements for applicants in the Citizenship Program.

Summary

Introduction

1. The concept of Australian citizenship has been enshrined in legislation since 1949.1 Citizenship is viewed as a privilege and marks the beginning of a person’s formal membership of the Australian community.2 A person may become an Australian citizen automatically (generally persons born in Australia to one or more parents who are citizens or permanent residents) or by application. Persons can apply for one of four types of citizenship by application: descent; adoption; resumption; and conferral.3 Citizenship by conferral is the largest component.

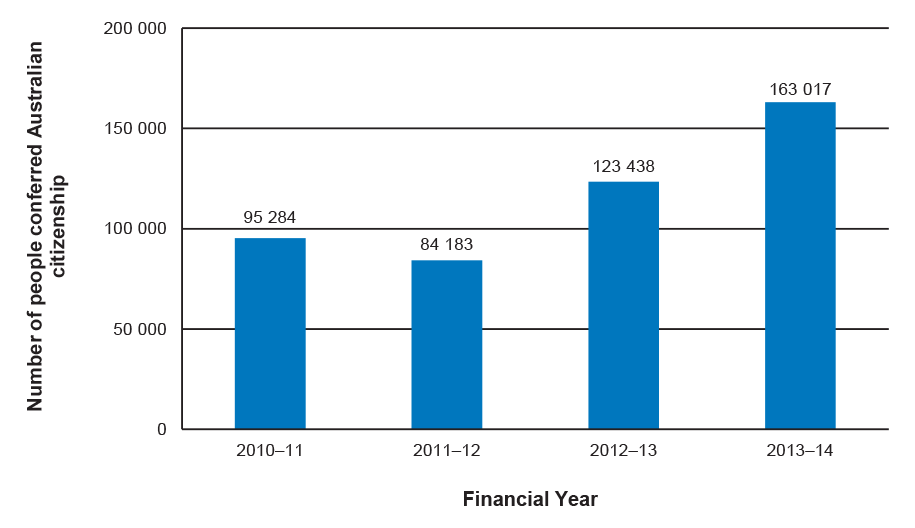

2. In 2013–14, more than 185 000 people applied for citizenship by conferral, representing 90 per cent of the total number who applied for citizenship.4 In the period 2010–11 to 2013–14, the number of approvals for conferral increased by 85 per cent from 85 916 to 158 870. The program’s expansion reflects the effects of large migration programs in recent years, changes to residence requirements, and, in part, the growing number of former irregular maritime arrivals becoming eligible to apply for citizenship. The majority of applications (around 80 per cent) for citizenship are approved.

3. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) is responsible for implementing the Government’s immigration and citizenship policies. DIBP promotes and administers Australian citizenship in accordance with the Australian Citizenship Act 2007 (the Act). The Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACIs) support the Act and outline the department’s policy as it relates to citizenship. In 2014–15, the Citizenship Program had a budget of $65 million.5

4. In general, to successfully apply for citizenship by conferral, a person must fulfil the Act’s ‘general eligibility’ criteria6—that is, the person must be a permanent resident who satisfies the residence requirement and be of ‘good character’.7 In addition to these requirements, an applicant must sit and pass the citizenship test to show, among other things, that they possess a basic knowledge of the English language and have an adequate knowledge of Australia and the responsibilities and privileges associated with Australian citizenship. Most applications for Australian citizenship are processed in DIBP’s State and Territory Offices (STOs), which form the department’s decentralised service delivery network. The majority of applications for citizenship by conferral are approved within a week of the applicant passing the citizenship test.

Verifying the identity of citizenship applicants

5. A key requirement for DIBP in administering Australian citizenship is verifying the identity of the person seeking citizenship. The Act requires that the Minister must not approve a person becoming an Australian citizen unless satisfied of the identity of the person.8 The department seeks to verify the identity of an applicant at three key stages, the:

- citizenship application: the department assesses the application, including determining whether it contains the required identity documents, which must include a photograph of the applicant and a completed identity declaration signed by a designated person.9

- citizenship test: prior to the applicant sitting the citizenship test and being approved for citizenship, DIBP verifies the identity of the applicant through face-to-face contact as well as by sighting/examining the applicant’s original identity documentation. During the test appointment (or shortly thereafter), citizenship officers are also required to request a National Police Check to identify whether the applicant has committed offences against Australian law and/or been imprisoned.

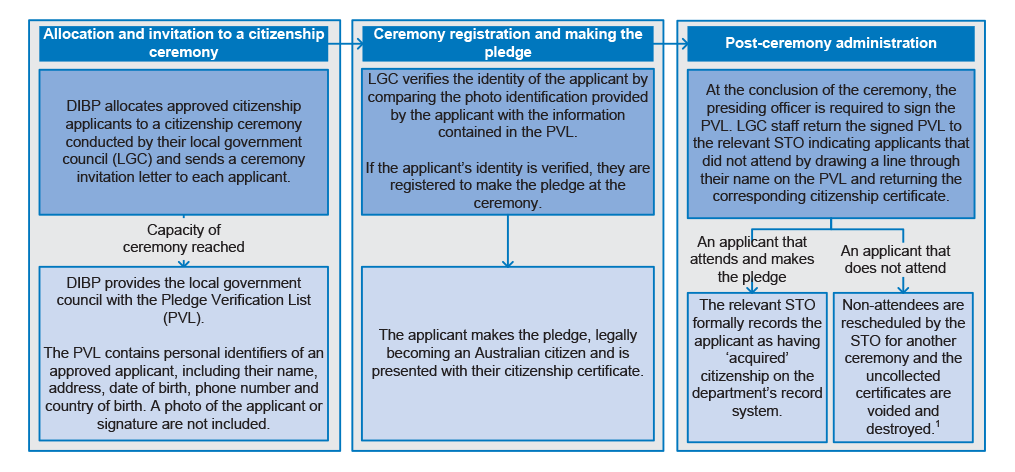

- citizenship ceremony: prior to the applicant taking the pledge of commitment and becoming an Australian citizen, ceremony officers10 examine the identity document/s presented by the applicant and determine whether they are satisfied of the applicant’s identity against the Pledge Verification List (PVL)11 provided by DIBP.

6. After making the pledge of commitment, applicants legally become Australian citizens and receive a commemorative citizenship certificate. The citizenship certificate is commonly used as a primary source document for identification purposes.

Requests for amendments to personal details

7. A person can choose to amend their personal details (for example, their name or date of birth) during the application process and/or after they have acquired citizenship.12 For cases arising during the application process, amendments can be sought under the Freedom of Information Act 198213 and will be processed by DIBP’s Freedom of Information (FOI) area. Citizens may apply to amend their personal details on their citizenship certificate, or to replace a lost certificate, through the ‘evidence’ of Australian citizenship process.14 These applications are administered by the Citizenship Program’s centralised Evidence Processing Unit. All identity related outcomes made by citizenship officers (both pre-citizenship and post-citizenship) are governed by the Act and require the Minister to be satisfied of the person’s identity.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s identity verification arrangements for applicants in the Citizenship Program.

9. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- administrative arrangements have been developed for verifying identity in the Citizenship Program; and

- arrangements have been implemented to effectively verify identity across the three key phases of the Citizenship Program: citizenship applications; the citizenship test; and the citizenship ceremony.

10. The audit covered the citizenship by conferral component, and within that component, focused on the ‘general eligibility criteria’, which includes applicants required to sit the citizenship test. Citizenship ceremonies conducted by local governments and DIBP were within the audit scope, however, the small proportion of ceremonies conducted by community organisations were excluded.

Overall conclusion

11. Citizenship offers persons born outside Australia the opportunity to make an ongoing commitment to Australia and grants privileges such as the right to vote and apply for an Australian passport. In administering the Citizenship Program, DIBP has been faced with an increasing volume of applications, with the number of applications approved for conferral increasing by 85 per cent (85 916 to 158 870) from 2010–11 to 2013–14. Recent cohorts of applicants, such as former irregular maritime arrivals, pose particular challenges because they may have limited or no identity documentation from their country of origin.

12. DIBP has put in place a range of processes that seek to establish and confirm the identity of persons when they apply for Australian citizenship; undertake the citizenship test; and make the pledge of commitment to become a citizen. While these arrangements to support identity verification are broadly sound, there are shortcomings in the implementation of the current administrative processes, including inconsistent practices in identity verification across DIBP’s State and Territory Offices. These shortcomings limit the extent to which the department can be assured that its identity verification obligations for citizenship are being effectively fulfilled. DIBP’s identity verification process would be strengthened by:

- providing decision-makers with clearer guidance on the key elements of identity that are to be considered when assessing citizenship applications;

- developing a risk based quality assurance program, which includes the appropriateness of decisions, so that DIBP can monitor the quality and consistency of citizenship decisions;

- including stronger personal identifiers15, such as the facial image of an applicant, as part of the Pledge Verification List provided to citizenship ceremony officers so that they can better verify an applicant’s identity at the ceremony registration; and

- developing and reporting against performance indicators that assess the quality of DIBP’s decisions.

13. Applicants who have not yet acquired Australian citizenship16 can seek to amend their personal details through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, which are processed by DIBP’s FOI area. Citizenship decision-makers are not currently alerted to changes to an applicant’s details that need to be re-verified prior to conferral. From 2012–13 to 9 April 2015, 42 FOI requests for changes to a citizenship applicant’s personal details were accepted through the FOI process. Formalising arrangements between the department’s FOI area and citizenship decision-makers, would allow the personal identifiers ultimately included on an applicant’s citizenship certificate to be appropriately verified.

14. To further improve DIBP’s arrangements for verifying identity in the Citizenship Program, the ANAO has made five recommendations designed to strengthen and improve the: consistency of identity verification assessments; department’s reporting against the objectives of the Citizenship Program; program’s quality assurance activities; identity verification at citizenship ceremonies; and re-verification processes following amendments to personal identifiers prior to conferring citizenship.

Key findings by chapter

Administrative Arrangements (Chapter 2)

15. The department’s administrative arrangements for delivering the Citizenship Program are decentralised, with national office responsible for program management and operational policy, and the citizenship network, responsible for processing citizenship applications.

16. Until the recent introduction of the Integrity Partnership Agreement—Citizenship Program (IPA)17 in March 2014, DIBP did not have a systematic approach to identifying and mitigating emerging and known risks to the Citizenship Program. IPAs have been implemented across the department and provide the specific program area, such as citizenship, with a risk management structure. However, further refinement is required to the citizenship IPA, so that the risk analysis methodology is tailored to the Citizenship Program, and quantifiable measures are developed to assess the effectiveness of risk treatments.

17. The Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACIs) guide decision-makers in their application of the Act, including the requirement that the Minister must be satisfied of the identity of a person applying for citizenship. While there will always be a need for citizenship officers to exercise their judgement according to the circumstances of each application, the ACIs, as they currently stand, do not provide decision-makers with sufficient guidance on the key elements that are to be considered when verifying the identity of citizenship applicants. Elements to be considered by citizenship officers verifying identity could be further illustrated through, for example, the inclusion of case studies in the ACIs. Furthermore, while the ACIs are available to all staff, advice on policy changes that occur between updates to the ACIs18 are stored in an information mailbox that is only available to management staff. Establishing a central repository for interim policy guidance that all staff across the citizenship network can access would strengthen the consistency of identity verification assessments across STOs.

18. The department informs internal and external stakeholders on its performance in delivering the Citizenship Program. Internal reporting largely focusses on high level, quantitative management information such as citizenship processing statistics, providing some insight into workload management. DIBP’s performance is publicly reported through its annual reports. These reports include key statistics for citizenship application and conferral rates. Results are also reported against the program’s three key performance indicators (KPIs): percentage of refusal decisions overturned through an appeals process; increased awareness of, and interest in Australian citizenship; and percentage of client conferral applications decided within the 60 day service delivery standard. From 2010–11 to 2013–14, the department consistently met the first two KPIs, however, only met the third KPI once in 2011–12.

19. The three KPIs allow DIBP to publicly report on its achievements in the context of quantitative targets. The KPIs do not provide insight into the department’s performance across other key areas of the program, such as the quality of approval decisions. In 2013–14, such decisions represented 83 per cent of the decisions made for citizenship by conferral. Expanding the KPIs to cover the quality of citizenship decisions, and reporting against these would provide assurance that the Citizenship Program is meeting its legislated requirements, including that the Minister must not approve a person becoming an Australian citizen unless satisfied of the identity of the person.

Arrangements for Verifying Identity (Chapter 3)

20. Citizenship officers in the STOs are to verify an applicant’s identity at the initial application and citizenship test appointment stages. However, citizenship officers are not consistently implementing the department’s identity verification processes for these two key stages.

21. For the initial application stage, the ANAO reviewed a sample of 400 paper and electronic applications.19 While 82 per cent of paper applications (126 of 153 applications) were pre-assessed according to the department’s requirements, over half of the electronically lodged applications (61 per cent, or 151 of 247) were processed without the officer sighting or reviewing the supporting identity documentation. At the citizenship test appointment stage, DIBP officers did not follow the key processes for identity verification for 26 per cent of applicants (105 of 400 applications). The most significant inconsistencies were that:

- no identity documents had been scanned and saved to the relevant DIBP database (10 per cent, or 42 of 400 applications); and

- a National Police Check was requested without the officer including all of an applicant’s known aliases (eight per cent, or 31 of 400 applications).

22. DIBP’s quality assurance checking activities20 focus on compliance by decision-makers with key administrative processes. Checks for identity include, for example, whether a facial image of the applicant has been saved into DIBP’s database. The quality assurance checking activities are devolved, and STOs are responsible for checking five per cent of applications decided each month across the different citizenship streams. In both 2012–13 and 2013–14, the department did not achieve the monthly sample rate of five per cent, instead achieving an average monthly sample rate of three per cent during these years. Nevertheless, the majority of process controls tested (82 per cent, or 167 of 204) resulted in a positive outcome, requiring no further attention from management.

23. DIBP’s quality assurance checking does not assess the quality of citizenship decision-making, including whether the identity of citizenship applicants has been properly verified. For example, the checks do not assess whether the evidence provided with an application is sufficient to adequately support a decision on identity. Consequently, DIBP management obtains limited assurance as to the quality and integrity of DIBP’s identification processes for citizenship applicants from the quality assurance checking process. The introduction of a quality assurance program that is risk based and focusses on the appropriateness of decisions made would better position the department to monitor the quality and consistency of citizenship decisions.

Citizenship Ceremonies and Evidence of Australian Citizenship (Chapter 4)

24. DIBP sees the citizenship ceremony stage as the final opportunity to satisfy itself of the identity of an applicant before they become a citizen. As the majority of citizenship ceremonies are conducted by local government councils, DIBP’s administrative arrangements allow for local government officers to verify, on their behalf, the identity of an approved applicant registering at the time of the ceremony. To facilitate this arrangement, DIBP provides local government officers with the: Australian Citizenship Ceremonies Code (Ceremonies Code), which outlines the requirements for the conduct of ceremonies; and Pledge Verification List (PVL), which contains some of an applicant’s personal identifiers such as name and date of birth, so that a cross-check can be undertaken at the time of the ceremony.

25. The Ceremonies Code guides those responsible for verifying the identity of applicants to ‘use their best judgement’ and to correctly identify applicants against the PVL. It does not however explicitly instruct ceremony officers to undertake a face-to-photo comparison of the applicant. Furthermore, the narrow range of personal identifiers in the PVL limits the extent to which officers can conduct a cross-check between the department’s records and the person presenting at the ceremony. Including as part of the PVL, personal identifiers such as the facial images of approved applicants, would strengthen current practices, especially in circumstances where a person has presented without photographic identification.

26. The ANAO observed the registration process at five citizenship ceremonies held from August to October 2014.21 In total, 376 applicants sought registration, with the majority presenting photographic identification in the form of a driver’s licence (78 per cent). Overall, the ANAO observed that the average time taken to verify the identity of applicants was between 10 and 20 seconds. Officers were observed using the applicant’s photo identification primarily to locate the name of the applicant on the PVL and to cross-check the name and address of the photo identification with the information contained in the PVL.

27. DIBP provides for the citizenship network to conduct quality checking activities for ceremonies through formal council liaison programs. STOs do not however maintain a formal liaison program with local government councils and do not attend citizenship ceremonies on a systematic basis for the purposes of quality assurance checking. Consequently, DIBP’s insight into the quality of the identity verification undertaken on its behalf is limited.

28. The centralised Evidence Processing Unit, is responsible for dealing with citizenship matters after a person has acquired citizenship.22 The Unit’s caseload has increased in volume by 39 per cent from 2011–12 (20 340 decisions) to 2013–14 (28 331 decisions) and also grown in complexity, with approximately 10 per cent of applications in 2013–14 requesting both the name and date of birth be changed on a citizenship certificate, compared to 7 per cent in 2012–13. The unit is required to apply the same evidentiary standard as for persons applying for citizenship when deciding whether to accept the amendments sought. However, the department does not conduct routine analysis to identify emerging trends or capture data that shows the risks associated with the increasing caseload.

29. As discussed previously, persons whose applications had been approved (but had not yet acquired citizenship), can request a change to their personal details through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, which are processed by DIBP’s FOI area. This process can result in changes being made to an applicant’s key personal identifiers by DIBP’s FOI area. Currently, there is no mechanism for citizenship decision-makers to be alerted to such changes, and consequently, the approved applicant could receive a citizenship certificate with amended personal identifiers that were not subject to re-verification. To date, DIBP has not monitored or reported on applicants requesting such changes. However, in response to this audit, DIBP sought a special report to be produced which showed that 42 personal identifier amendment requests were accepted through the FOI process from 2012–13 to 9 April 2014–15. The majority (29, or 69 per cent) of these request related to a change of name.

Summary of entity response

30. The proposed report was provided to DIBP and extracts were provided to the Department of Human Services (Human Services) in relation to Human Services’ conduct of citizenship test appointments in regional areas. Summary responses to the audit are provided below and formal responses are included at Appendix 1.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection acknowledges the findings outlined in the proposed audit report on Verifying Identity in the Citizenship Program and agrees with the five recommendations.

As the report noted, in March 2015 the department implemented a significant restructure as part of the portfolio reform process. The restructure effectively brought the programme management and service delivery elements of the citizenship programme under a single management structure, which will provide clearer programme accountabilities and additional support from the newly formed Community Protection Division, in areas such as complex identity assessments and caseload assurance.

As a result, the department is currently refining citizenship policy and business processes to further strengthen assessment of the identity of persons applying for Australian citizenship, undertaking the citizenship test and making the pledge of commitment to become a citizen.

The department has also commenced the development of a risk-based quality assurance framework for the citizenship programme which will include enhanced reviews of identity verification processes and decision-making. The development of key performance indicators to assess the quality of citizenship decisions will be addressed as part of this work.

More broadly, the department is expanding its biometric capability in visa programmes, which will provide a stronger identity platform for identity assessments when clients later apply for Australian citizenship.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes the report and notes that there are no recommendations or major findings for the department.

The department also notes that the report states that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s quality assurance results show a general improvement in this department’s administration of regional test appointments from 2013–14 to 2014–15.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.22 |

To strengthen the consistency of identity verification assessments, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 2.52 |

To more effectively assess and report on the objectives of the Citizenship Program, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection develops and reports against key performance indicators assessing the quality of the department’s citizenship decisions. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 3.59 |

To improve the quality assurance process for the Citizenship Program, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection extends its quality assurance program to include a risk based approach and consideration of the appropriateness of decisions, including whether the identity of the applicant has been properly verified. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 4.21 |

To strengthen the identity verification activities conducted at citizenship ceremonies, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection includes stronger personal identifiers, such as the facial image of approved applicants, in the Pledge Verification List provided to ceremony officers. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 5 Paragraph 4.44 |

To provide greater assurance that the identity of citizenship applicants has been appropriately verified, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection puts in place arrangements to alert citizenship decision-makers when an applicant amends their personal details under Freedom of Information provisions prior to citizenship conferral. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides background information on the Citizenship Program, particularly the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s arrangements for administering the identity requirements of the program. The chapter also outlines the audit objective and approach.

Introduction

1.1 In 2013–14, over 200 000 people applied for Australian citizenship. Citizenship grants privileges such as the right to: vote in elections; apply for positions in the Australian Public Service and Australian Defence Force; seek election to Parliament; and hold an Australian passport.

1.2 The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) is responsible for implementing the Government’s immigration and citizenship policies to support the outcome of a prosperous and inclusive Australia. DIBP promotes and administers Australian citizenship in accordance with the Australian Citizenship Act 2007 (the Act). The Act replaced the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 which came into effect in January 1949, enshrining in legislation the concept of Australian citizenship.23

1.3 The Act introduced changes to key eligibility requirements including: strengthening national security requirements and the department’s powers to collect and store applicants’ personal identifiers; and introducing a citizenship test. The Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACIs) support the Act and outline the department’s policy as it relates to citizenship. In 2014–15, the Citizenship Program had a budget of $65 million.24

Australian Citizenship

1.4 Australian citizenship marks the beginning of a person’s formal membership of the Australian community.25 A person may become an Australian citizen automatically or by application. Generally, persons born in Australia to one or more parents who are Australian citizens or permanent residents acquire citizenship automatically. Persons born outside Australia can acquire citizenship by application. There are four types of citizenship by application:

- descent—for persons born outside Australia and with one or both parents being Australian citizens at the time the person was born;

- adoption—for persons adopted outside Australia, in accordance with the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption or by bilateral arrangements, by at least one Australian citizen;

- resumption—for persons who ceased to be Australian citizens and wish to become citizens again; and

- conferral—for persons who cannot apply under the other three categories and who meet the eligibility criteria.

Citizenship by conferral

1.5 The largest component of the Citizenship Program is citizenship by conferral.26 People who have been lawfully present in Australia for four years and as a permanent resident in the final year may apply for citizenship by conferral.27 Accordingly, citizenship by conferral is the most common pathway by which refugee and humanitarian entrants, skilled and other migrants become citizens. In 2013–14, more than 185 000 applicants applied for citizenship by conferral, representing 90 per cent of the total number of people that applied for Australian citizenship.28 In contrast, approximately 21 000 applications are received per annum for citizenship by descent, and fewer than 450 per annum for citizenship by adoption and citizenship by resumption.

1.6 At the commencement of this audit, responsibility for administering the Citizenship Program and decision-making, was distributed between the Citizenship Branch in DIBP’s national office and the citizenship service delivery network (the citizenship network)—consisting of the Global Manager Citizenship (GM Citizenship)29 and citizenship officers in the State and Territory Offices (STOs).30

1.7 In March 2015, as part of the broader reform process in the Immigration and Border Protection portfolio31, a new organisational and management structure came into effect for a large number of areas across the portfolio, including citizenship. The key changes to the Citizenship Program’s administrative arrangements are that:

- legislative and policy aspects of the program are administered as part of the department’s Policy Group; and

- program management, service delivery, and operational policy are administered together under the Visa and Citizenship Services Group, ending the GM Citizenship role and operational management of the citizenship network.

Processing citizenship applications

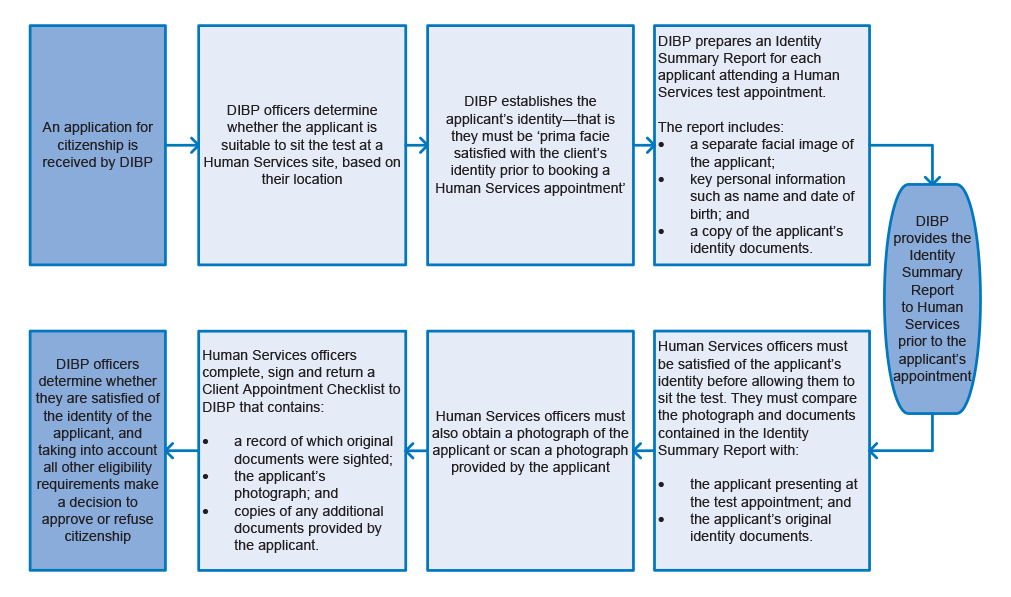

1.8 Most citizenship decisions, including the verification of an applicant’s identity, are not complex. DIBP’s decision-makers in the STOs (generally at the Australian Public Service 4 level) commonly approve the majority of citizenship by conferral applications within a week of the applicant passing the citizenship test. The approval pathway for the more complex citizenship applications can often take months or, in some cases, years for a decision to be made. Figure 1.1 sets out the key steps in the citizenship application process from DIBP’s receipt of the application to an eligible applicant being legally conferred as an Australian citizen at a citizenship ceremony.

Figure 1.1: Key steps in the citizenship process

Source: ANAO analysis of DIBP’s processes.

Note 1: In July 2013, DIBP commenced a formal partnership with the Department of Human Services for citizenship tests to be conducted in regional areas. This is discussed in paragraph 1.11.

Note 2: The Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (the Minister) must not approve a person becoming an Australian citizen at a time when an adverse security assessment, or a qualified security assessment, in respect of that person is in force under the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979. See Australian Citizenship Act 2007 ss. 24(4) and 24(4D).

1.9 The majority of applications for citizenship are approved (around 80 per cent).32 In the period 2010–11 to 2013–14, the number of approvals for conferral increased significantly—from 85 916 to 158 870 (an 85 per cent increase). The increase can in part be attributed to the effects of changes to the residence requirements introduced by the Act33 and the large migration programs in recent years.

1.10 Prior to approval for citizenship, most applicants are required to successfully complete the citizenship test.34 The test was introduced with the Act and is intended to assess an applicant’s knowledge of the English language and the rights and responsibilities associated with Australian citizenship. Citizenship tests are conducted at 11 STOs across Australia. In 2013–14, 121 304 applicants sat the citizenship test and 119 084 (98 per cent) passed.35

1.11 In July 2013, DIBP established a partnership arrangement with the Department of Human Services (Human Services) to conduct citizenship tests in regional areas on behalf of DIBP.36 Under this arrangement, DIBP refers clients in regional areas to Human Services sites (such as Centrelink and Medicare offices) for citizenship test appointments. In 2013–14, Human Services administered 6244 citizenship tests (four per cent of all tests undertaken). As at March 2015, Human Services provides citizenship testing at 33 sites, conducting approximately 300 tests per week.

1.12 As outlined in Figure 1.1, an applicant only legally becomes an Australian citizen on the day they make the pledge of commitment, which is generally at an Australian citizenship ceremony.37 Ceremonies are usually conducted by local governments under the authority of the Minister responsible for citizenship. Figure 1.2 shows the number of applicants that have become Australian citizens from 2010–11 to 2013–14. In line with the trend in approvals, the conferral rate over the four years has also increased significantly, by 71 per cent. It should be noted that in any given year, the number of conferrals reported may differ from the number of approvals, as people can be conferred up to one year following the date their application was approved.

Figure 1.2: Number of conferrals for Australian citizenship, 2010–11 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of DIBP Annual Reports 2010–11 to 2013–14.

Verifying identity in the Citizenship Program

1.13 Once conferred, citizenship can be revoked by the Minister in only limited circumstances, including where an applicant has been convicted of engaging in fraud or false representation in applying for citizenship, or where a person is convicted of a serious criminal offence prior to becoming a citizen.38 DIBP informed the ANAO that in the 66 years in which Australia has offered citizenship, revocation has occurred in only 16 cases. Given the near irrevocable status of citizenship, it is important that DIBP confers citizenship to only those applicants that fully satisfy the requirements established to support the integrity of the Citizenship Program.

1.14 A key aspect of the decision-making process relates to the identity of the person seeking citizenship. The Act requires that the Minister must not approve a person becoming an Australian citizen unless satisfied of the identity of the person.39 To give effect to this requirement, DIBP seeks to verify the identity of applicants at three key stages: on application, when sitting the test and at the citizenship ceremony.

1.15 When determining a person’s identity, DIBP decision-makers are supported by the Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACIs). In addition to being a requirement within the legislation, the ACIs provide that ‘the Australian community expects that decision makers will not approve a person for citizenship if they are not satisfied of the person’s identity’.40

1.16 The majority of citizenship ceremonies are conducted by local governments, with local government staff responsible for registering applicants who present to make the pledge of commitment.41 At citizenship ceremonies, new citizens are presented with an Australian citizenship certificate, which carries significant weight in the community as an identity document.

1.17 At any time after obtaining citizenship, citizens have the right to apply for: amendments to their biographical details as held by DIBP and recorded on their Australian citizenship certificate; or the replacement of a lost or stolen citizenship certificate. Applications of this nature—known as applications for evidence of Australian citizenship—are also governed by the Act and are processed by DIBP’s centralised Evidence Processing Unit. As with applications for citizenship, evidence of Australian citizenship must not be given unless the Minister is satisfied of the person’s identity.

Proposed legislative amendments

1.18 Until recently, the Citizenship Act 2007 and DIBP’s processes have remained largely unamended. However, in 2014, the Australian Citizenship and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2014 (the Bill), proposed substantial changes to the Act.42 The Bill contains a suite of amendments expanding the Minister’s powers to cancel or revoke citizenship, including additional circumstances in which identity assessments can affect the outcome of a citizenship application. Specifically, the proposed amendments include that:

- for applicants required to make the pledge of commitment, the Minister must cancel an approval for citizenship where the Minister ceases to be satisfied of the person’s identity;

- the Minister can revoke citizenship without the person or a third party having been convicted where satisfied that the person obtained approval to become an Australian citizen as a result of fraud or misrepresentation (including fraud or misrepresentation connected with the person’s entry into Australia or with the granting of a visa), and where it would be contrary to the public interest for the person to remain an Australian citizen; and

- where DIBP has refused or cancelled an application on identity grounds, and the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) has decided in favour of the applicant, the Minister can set aside the decision of the AAT. Furthermore, a review by the AAT can no longer be performed for citizenship decisions made personally by the Minister.43

1.19 The Bill, which is currently before the Parliament, emphasises the risk that questions of identity pose to the successful delivery of the Citizenship Program.44 In this context, it is essential that DIBP’s administrative arrangements for verifying identity, support decision-making processes that uphold the integrity of the program, particularly within the parameters set by the Government.

1.20 On 26 May 2015 the Prime Minister and the Minister jointly announced new measures to strengthen Australian citizenship. The Australian Government proposes to amend the Act so dual nationals who engage in terrorism can lose their citizenship. It is proposed that the Minister will be able to exercise these powers in the national interest where a dual citizen participates in serious terrorist-related activities. The department advised that the changes will be consistent with Australia’s international legal obligation not to leave a person stateless and that there will also be safeguards, including judicial review, to balance these powers. Also launched was a ‘national conversation’ to improve understanding of the privileges and responsibilities of Australian citizenship and to seek the public’s views on further possible measures, including the suspension of certain privileges of citizenship for those involved in serious terrorism.45

Recent audits and reviews

1.21 Elements of the Citizenship Program have been the focus of audits and reviews conducted internally by DIBP and externally by the ANAO. While not confined to the Citizenship Program, a recent internal audit Identity Management (June 2014) examined the management of identity across the department’s programs and functions, concluding that there was not a coordinated approach across the department for managing identity policy, risks and initiatives and that the use of identity services was variable across the department. More specific to the Citizenship Program, an internal fraud control audit (Review of Fraud Control in the Citizenship Programme July 2014) identified areas of citizenship’s fraud control arrangements that could be improved, including the program’s quality assurance regime.

1.22 The ANAO’s previous audit of the Citizenship Program46, focused on the Act’s character requirements. Overall, the audit identified that the department had established an appropriate framework for administering the character requirements, but found that:

- there was variability in the application of processes for decision-making; and

- the term ‘good character’ was not defined, for administrative purposes, in policy and guidance materials.

The department agreed to the ANAO’s recommendations to address these matters.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

1.23 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s identity verification arrangements for applicants in the Citizenship Program.

Audit criteria

1.24 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- administrative arrangements have been developed for verifying identity in the Citizenship Program; and

- arrangements have been implemented to effectively verify identity across the three key phases of the Citizenship Program: citizenship applications; the citizenship test; and the citizenship ceremony.

Audit scope and methodology

1.25 The audit covered the citizenship by conferral component, and within that component, focused on the ‘general eligibility criteria’, which includes applicants required to sit the citizenship test. Citizenship ceremonies conducted by local governments and DIBP were also within the audit scope. However the small proportion of ceremonies conducted by community organisations were excluded.

1.26 The ANAO’s methodology included:

- reviewing relevant DIBP documentation and analysing a sample of 400 approved paper and electronic applications47 (from six STOs48) for citizenship by conferral, to test the department’s verification of identity on application and at the citizenship test;

- consulting and observing DIBP staff and local government officials verifying the identity of applicants at five citizenship ceremonies; and

- interviewing key personnel at DIBP’s national office in Canberra, as well as at three STOs: the ACT Regional Office; the Parramatta Regional Office; and the Queensland State Office. Fieldwork also involved observing citizenship test appointments at Human Services sites at Newcastle (New South Wales) and Kawana Waters (Queensland).

1.27 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $416 000.

Report structure

1.28 The structure of this report is outlined below.

|

Chapter |

Chapter overview |

|

Chapter 2: Administrative Arrangements |

Examines DIBP’s administrative arrangements to support accurate and consistent decision-making as it applies to assessing the identity of citizenship applicants. |

|

Chapter 3: Arrangements for Verifying Identity |

Examines DIBP’s processes for verifying an applicant’s identity from the time of applying for Australian citizenship to the department approving the applicant for citizenship. |

|

Chapter 4: Citizenship Ceremonies and Evidence of Australian Citizenship |

Examines DIBP’s arrangements for the verification of the identity of applicants at citizenship ceremonies and elements of DIBP’s administration of applications for evidence of Australian citizenship. |

2. Administrative Arrangements

This chapter examines DIBP’s administrative arrangements to support accurate and consistent decision-making as it applies to assessing the identity of citizenship applicants.

Introduction

2.1 Applicants for Australian citizenship must fulfil the eligibility criteria outlined in the Act to become an Australian citizen. Putting in place appropriate arrangements to administer the Act’s identity requirements and to support decision-making processes is particularly important, as the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (the Minister) must not approve a person becoming an Australian citizen unless satisfied of the identity of the person.49

2.2 The ANAO examined DIBP’s administrative arrangements to support accurate and consistent decision-making as it applies to assessing the identity of citizenship applicants. Particular emphasis was given to the:

- assessment and management of risks in the Citizenship Program;

- guidance and policy documents, primarily the Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACIs), that support decision-makers’ interpretation of, and exercise of powers, for verifying identity under the Act;

- advice and training to support decision-makers’ assessing identity across the citizenship network; and

- performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Citizenship Program.

Assessing and managing risks in the Citizenship Program

2.3 Identifying, assessing and mitigating risk is fundamental for good public sector governance. The Integrity Partnership Agreement—Citizenship Program (IPA), introduced in March 2014, outlines the agreed fraud control, risk review and monitoring activities for the Citizenship Program.50 Prior to the implementation of the IPA, DIBP did not have a systematic approach to identifying, analysing or responding to risks specific to the Citizenship Program.

Integrity Partnership Agreement—Citizenship Program

2.4 The objectives of the IPA include to: detect and respond to significant and serious fraud in the Citizenship Program; and accurately map risks through evidence based analysis and reporting, to support streamlined processing and appropriately target resources. The risks identified for action are that citizenship is acquired by an applicant:

- using a false or stolen identity (or evidence of citizenship is acquired by such means);

- who previously obtained a visa on fraudulent grounds;

- who has made false declarations in their application;

- who does not meet eligibility requirements;

- who is not of good character; and

- who has used an impostor or deception to obtain their citizenship.

2.5 As part of the IPA, the Citizenship Risk Management Group (RMG)51 meets each quarter to discuss the results of the review activities undertaken and ‘provide high level oversight and collaboration in identifying and treating emerging risks’ in the citizenship network. DIBP has also developed and undertaken projects to fulfil the objectives of the IPA and address the risks identified. As at March 2015, the department reported two ongoing projects that specifically relate to identity management in the Citizenship Program:

- Identity Assessment—which involves the development of protocols and the capability for dealing with identity resolution issues, including treatment of complex IMA cases in citizenship processing; and

- Identity Refusal Caseload—which involves analysing citizenship refusals recorded as not meeting identity requirements to determine whether risk profiles can be developed.

2.6 The Citizenship IPA includes a range of measures for its risk treatment and review activities. These measures are summarised in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: IPA—Measures for risk treatment and risk review activities

|

Risk treatment—activity |

Risk treatment—measure |

|

Integrity referral activity |

Better targeted referrals |

|

Utilisation of reference tools |

Number of fraudulent documents confirmed |

|

DNA testing |

Number of relationship fraud instances detected |

|

Visa cancellation |

As per Visa Cancellation Priority Matrix |

|

Approve cancellations - where fraud confirmed post-approval but pre-conferral |

Number of deferrals resulting in cancellation |

|

Risk review—activity |

Risk review—measure |

|

Risk review and monitoring |

Quarterly ‘Risk Review Report’ |

|

Risk rule analysis |

6 monthly |

|

Projects |

Varying - see Project Register |

Source: ANAO representation of the risk treatment and risk review activities from DIBP’s Integrity Partnership Agreement—Citizenship Program.

2.7 The ANAO reviewed the measures set out in Table 2.1 and noted that while they are relevant, they do not include quantifiable measures to assess the effectiveness of the corresponding risk treatments. Consequently, reports provide DIBP management with only limited insights into the effectiveness of the risk treatments developed for the Citizenship Program, and limited assurance that the IPA is achieving its intended outcomes.

2.8 The IPA establishes quarterly reporting requirements. However, as at December 2014, only one Risk Review Report had been formally accepted by the RMG. The Group did not accept the second Risk Review Report (4th Quarter 2013–14), with the Citizenship Policy area (the responsible risk lead for the group) providing extensive feedback on perceived shortcomings in the report.52 The Citizenship Policy area’s key concern regarding the second Risk Review Report was that the risk analysis methodology to detect fraud replicated the approach taken for the migration program and could not produce meaningful reporting for the Citizenship Program without adjustments. For example, in respect of:

- risk treatment activities—the information would be more useful if it were provided by the five citizenship streams (Conferral, Descent, Adoption, Evidence and Resumption) rather than being amalgamated; and

- Freedom of Information requests with both name and date of birth changes—the information reported would be more useful if it indicated the significance of the change. For example, whether it was a minor variation to the spelling of a name or a correction to a recorded date of birth, or whether it was something more substantial.

2.9 The introduction of the IPA is a useful first step in providing DIBP with a more structured approach to managing the risks to the Citizenship Program. However, it will be important that the IPA is tailored to the Citizenship Program. As at March 2015, a 2014–15 IPA had not been developed or implemented. DIBP informed the ANAO that ‘further development is required to ensure that the IPA is sufficiently broad and correctly linked to new stakeholders to support the citizenship program’ and that it will be reviewed in light of the departmental restructure.

Specifying identity verification requirements

2.10 The Act provides the legislative basis for Australian citizenship.53 Supporting the legislated citizenship identity requirements are the ACIs, as well as guidance for staff processing applications, primarily through the Citizenship Procedures Manual.

Australian Citizenship Instructions

2.11 The ACIs are not legally binding, but are designed to guide decision-makers54 in relation to the interpretation of, and the exercise of power under, the Act and the Regulations. The ACIs address each of the Act’s components, providing high level policy guidance as well as allowing citizenship officers flexibility in applying policies, as appropriate, to individual circumstances. In terms of providing guidance for staff who are processing applications for citizenship by conferral, the ACIs briefly cover identity, restating the Act’s requirement that applicants can be refused citizenship on a number of grounds, including where the Minister is not satisfied of the identity of the person. The instructions also broadly state that the Australian community ‘expects’ that approval would not be given to applicants that cannot satisfy the department as to their identity.

2.12 In contrast, for the smaller caseload relating to requests for evidence of citizenship, the ACIs contain specific instructions for decision-makers dealing with identity issues, such as changes of name, and alert decision-makers to potential referral avenues where they are in ‘doubt’ about a person’s identity.55

2.13 It is recognised that there is a limit to the extent to which DIBP policy can prescribe all the elements for verifying identity. Diverse and often complex individual scenarios can arise and there will always be the need for decision-makers to exercise a degree of discretion and judgement. However, the ACIs, as they currently stand, do not provide sufficient guidance in relation to the key elements decision-makers, particularly those processing citizenship by conferral applications, are to consider when verifying the identity of citizenship applicants. Restating the high level requirements of the Act and expectations of the broader community does not provide standalone guidance for citizenship officers assessing the identity of an applicant.

2.14 There would be merit in the department amending the ACIs to clearly outline for all citizenship application types, the key elements that decision-makers should consider to be satisfied of an applicant’s identity. Elements to be considered by citizenship officers verifying identity could be further illustrated through, for example, case studies being included in the policy guidance. Such improvements would support greater consistency across the network and further improve the integrity of the citizenship network’s delivery of citizenship services.

2.15 STOs consulted during the audit also raised the challenges faced regarding a particular aspect of the ACIs—that applicants must apply for citizenship using their current ‘legal name’ and where appropriate, provide official evidence of any name change.56 In the absence of specific guidance in the ACIs, the approach of STOs has been guided by their strict interpretation of ‘legal name’, applying limited discretion for applications involving differences between the ‘legal name’ of the applicant (such as that presented on a birth certificate or passport) and the name presented on other identity documents such as an Australian issued driver’s licence or Medicare card. The ANAO’s observation of this interpretation and approach by one STO visited is discussed in the following case study.

|

Case study: name discrepancies and identity verification processes |

|

A citizenship applicant presented to a STO counter to sit the citizenship test and presented the following identity documentation:

Identity assessment The citizenship officer identified that the applicant’s birth certificate included a middle name that did not appear in the applicant’s passport or driver’s licence, or their application form. The applicant was advised that they could not sit the citizenship test that day and that the inconsistency would need to be addressed before they could be accepted to sit the test. Actions requested of the applicant The citizenship officer advised the applicant to visit the state’s Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages to officially change their name so that either their:

|

2.16 While the STO’s approach focussed on the integrity of an applicant’s name—the most widely used and accepted identifier of an individual—there has been a number of unintended consequences:

- Medicare has received thousands of requests from DIBP clients seeking to include the details of their full name on their Medicare enrolment for the purpose of applying for Australian citizenship; and

- a higher number of applications have been received requiring multiple assessments.

2.17 DIBP’s national office adopts a more holistic interpretation. As a consequence, tensions between the guidance, the STOs’ interpretation and national office’s approach to ‘legal name’ have existed for quite some time. In April 2014, Citizenship Policy sought comments from STOs regarding some possible amendments to the ACIs to deal with ‘small variations’ in applicants’ names.57

2.18 A recent policy advice email (November 2014) acknowledged that there has been ‘some confusion concerning the required identity documents and the extent to which they may “collectively” indicate an applicant’s identity and current legal name’. The advice states that while documents presented by applicants should collectively support their identity, they do ‘not need to all be in the same name’ (as shown in the previous case study) provided that there are clear linkages between names or name changes (supported by official documents). The advice stated that:

There is no higher level of risk associated with processing an application where all documents are not in one name but there is a coherent client story which is supported by appropriate, plausible documentation. Likewise, having a series of documents in the same name does not reduce the risk the client may pose.

2.19 The same policy advice email also identified that the ACIs contain particular inconsistencies in respect of assessing applicants for evidence of Australian citizenship58, referring to three different types of naming requirements: ‘full name’ (which the application form requires); ‘legal name’; and ‘legal identity’. The department advised that it is planning to address this issue in the next update of the ACIs and, in the interim, the matter will be covered in a ‘Citizenship Red Notice’ (emails notifying of an official change of policy or existing policy).59

2.20 Citizenship Red Notices are useful for DIBP to communicate interim policy changes directly to all citizenship staff as they occur.60 However, once sent, Citizenship Red Notices are stored in the Global Manager information mailbox, which is only available to management staff. In the absence of a central repository for interim policy changes that is accessible to all staff, new starters may not be aware of interim policy changes and may not implement the latest advice.

2.21 DIBP advised that it is creating a specific identity policy for citizenship, and accompanying guidance on name change scenarios that applicants may present when applying for citizenship.61 However, there has been little progress in finalising the policy since September 2013. Finalising the citizenship identity policy—consistent with broader departmental identity and naming policies62—will provide a firmer foundation for the implementation of effective and consistent operational practices across the citizenship network.

Recommendation No.1

2.22 To strengthen the consistency of identity verification assessments, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

- clearly outlines in the Australian Citizenship Instructions, the key elements of identity that decision-makers are to consider when assessing citizenship applications; and

- establishes a central repository for interim policy guidance that is accessible to all staff.

DIBP’s response: Agreed.

2.23 The department will amend the Australian Citizenship Instructions to include further policy advice on identity matters as required by the Australian Citizenship Act 2007. Interim policy guidance is centrally stored on the department’s file management system. The department will undertake actions to ensure that relevant staff know where to find this stored advice.

Citizenship Procedures Manual

2.24 The Citizenship Procedures Manual (the manual) represents the primary guidance document underpinning the step-by-step processes decision-makers are to undertake when administering citizenship applications. While the manual focuses on process, it provides some guidance in relation to confirming an applicant’s identity when they present at the citizenship test appointment. The manual contains an extensive list of the ‘physical’ qualities of an applicant’s passport (or other proof of identity documents) that a citizenship officer might consider when assessing whether it may require further checking by expert document examiners to verify its legitimacy.

2.25 Other specific instructions for verifying an applicant’s identity at the test appointment include that the:

- citizenship officer administering the appointment must confirm that the client presenting at the appointment is the same person as depicted in the facial image provided; and

- citizenship officer photographs the client at the appointment.

2.26 The manual also highlights that in cases where the citizenship officer is not satisfied of an applicant’s identity at the test appointment, or the applicant does not provide the required documents, the applicant should not sit the test and the next steps are to be discussed with the applicant.

Supporting decision-makers: advice and training

2.27 The Citizenship Help Desk (the Help Desk) in national office provides advice to officers across the citizenship network on Australian citizenship policy, procedural and case related issues. The Help Desk is the first point of contact for inquiries that require expertise outside the network. In some instances, the Help Desk also refers inquiries from other areas of the program such as Citizenship Policy.

2.28 DIBP reports on the number of inquiries made to the Help Desk with statistics aggregated into high level categories—citizenship test, citizenship eLodgement and totals for all Help Desk inquiries received and completed. The collated data is presented in the monthly Executive Management Report, which provides a high level summary of key administrative and processing outcomes for citizenship management.

2.29 DIBP does not routinely analyse Help Desk statistics and currently reports data in a format that provides limited insight into trends or emerging issues that may require further attention across the citizenship network. The ANAO’s analysis shows that the percentage of identity related inquiries referred from the Help Desk to Citizenship Policy63, while low, has increased threefold from 13 in 2012–13 (one per cent of all queries referred to Citizenship Policy) to 101 in 2013–14 (three per cent). The Help Desk data collected by DIBP does not identify what factors have contributed to this increase, including the influence or trend of any new or emerging identity related risks. There would be benefit in the department periodically analysing its Help Desk statistics to better understand the types of identity issues being raised, and to inform management decisions and policy amendments.

2.30 In addition to the Help Desk, decision-makers can access a number of DIBP resources when processing applications, particularly citizenship cases with complex identity scenarios.64 Decisions in relation to complex cases may be informed by advice and work undertaken by, for example, the:

- Document Examination Unit—which provides forensic document examination to identify genuine, fraudulent and counterfeit documents;

- Identity Resolution Centre—which provides specialist facial image and fingerprint comparisons, and can apply enhanced name searching and data matching tools;

- National Identity Verification and Advice (NIVA)—which provides assistance or advice to citizenship officers on alternative lines of enquiry where identity concerns are being assessed; and

- Identity Integrity—which helps to assess an applicant’s identity using internet and database research, as well as document assessment.

2.31 System alerts also signal to decision-makers instances where the features of a case may match a known high risk caseload, prompting decision-makers to refer the case to expert areas such as Identity Integrity for a ‘full identity assessment’.65

2.32 However, DIBP has not documented the range of expert referral services that are available. The only guidance available to decision-makers is through the citizenship program’s Master Case Escalation Matrix. The case escalation matrix advises decision-makers to contact the Help Desk and for cases specifically involving identity issues, prompts citizenship officers to seek advice from only one of the expert referral areas, NIVA. DIBP informed the ANAO in March 2015 that referral pathways are currently being documented for the new departmental structure.

Citizenship training

2.33 Citizenship officers have access to a range of training courses and materials, largely delivered face-to-face or increasingly through e-learning modules. The Citizenship Branch Training Strategy (2011) underpins the training catalogue for the short to medium term (one to three years) and aims to support the program’s strategic goals.

2.34 While on-the-job training forms a large part of the training delivered to citizenship officers, the principal training course is the Citizenship Training Program (the CTP). The CTP is a comprehensive, three and a half day training course for staff with three to 12 months experience in the citizenship program. Half a day of the CTP is dedicated to identity training and includes content in relation to: the importance of verifying identity; how a decision-maker may satisfy themselves of a person’s identity; document verification and facial recognition; and how to proceed when suspicious of a person’s identity.66

2.35 National office records staff attendance for the CTP, however, STOs are responsible for determining which staff are required to attend and monitoring those that have not yet attended. The department informed the ANAO that the CTP was delivered: three times in 2013, with a total of 55 attending; and twice in 2014, with a total of 39 staff attending.67 There was an 11 month gap between the last CTP offered in 2013 (December) and the first offered in 2014 (November).

2.36 While the CTP provides formal and consistent training across the citizenship network, citizenship decision-makers may have performed their duties for a considerable period prior to attending the CTP. In this context, induction training (along with on-the-job training) delivered when new citizenship staff commence, is important for providing appropriate support to decision-makers across the network. An STO learning and development strategy (in draft since March 2013) identified the need to develop a nationally consistent Citizenship Induction Program. Consequently, in October 2013, DIBP conducted a trial launch to all STOs of an induction program framework and an accompanying induction workbook. While the induction program has not been formally implemented, DIBP informed the ANAO that the induction materials assist managers to determine the training and development needs of new staff and that the program has been used as a resource by managers ‘on an as-needs basis’.

2.37 Currently, DIBP does not formally monitor learning and development across the citizenship network. Given that the aim of the network-wide STO learning and development strategy and complementary induction program is to promote consistency in approach and processes, there would be merit in DIBP considering implementing formal monitoring arrangements.

2.38 To supplement the CTP, DIBP informed the ANAO that refresher training is delivered to STOs on an as-needs basis—where the need for the training has been identified by national office or the relevant STO manager. In 2014, two refresher training half-days were conducted in one STO. Staff from two of the STOs visited by the ANAO highlighted the need for training to be delivered more frequently. As discussed in Chapter 3, the ANAO’s review of a sample of 400 applications for citizenship by conferral highlighted inconsistent identity verification practices across STOs, which could, in part, be addressed through staff training.

2.39 The citizenship program is continually responding to emerging complex issues, particularly in relation to identity. Formally implementing the induction program as well as more frequent and targeted refresher training would better support consistent administration by increasing awareness among decision-makers of changes in policies and practices as well as areas requiring additional attention.

Measuring and reporting performance

2.40 DIBP is responsible for delivering three government outcomes, with one of these relating to citizenship:

Outcome 1 – Support a prosperous and inclusive Australia through managing temporary and permanent migration, entry through Australia’s borders, and Australian citizenship.68

2.41 The 2014–15 Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) set out the program objectives, deliverables and key performance indicators (KPIs) relevant to Outcome 1. Table 2.2 outlines the relevant indicators as well as the program’s objectives and deliverable.

Table 2.2: Citizenship objectives, deliverable and performance indicators 2014–15

|

Program objectives |

Deliverable |

Key performance indicators |

Targets |

|

|

|

< 1% |

|

300 000 visits to Citizenship Wizard |

||

|

80% |

Source: Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2014-15, Budget Related Paper No. 1.11, Immigration and Border Protection Portfolio, pp. 26-30; and Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Citizenship processing time service standards, 13 February 2015, available from <www.immi.gov.au> [accessed 2 June 2015].

Note 1: The Portfolio Budget Statements 2013-14, included a deliverable that was not carried through to 2014–15—Deliver lawful citizenship decisions under Australian citizenship legislation.

Note 2: The Citizenship Wizard is accessed through the DIBP website. Based on a series of questions answered by the user, the Citizenship Wizard suggests the type of citizenship application for which the user might be eligible and provides information about how to apply for Australian citizenship.

Key performance indicators for citizenship

2.42 All three of the department’s KPIs apply quantitative targets to measure performance. Notwithstanding the importance of DIBP informing the Parliament and key stakeholders on its performance against service delivery standards and the percentage of refusal decisions upheld, the current indicators provide limited insight into the department’s overall performance in delivering the citizenship program. Indicators for measuring and reporting on performance in other areas of the program that are integral to the successful delivery of citizenship are not included.

2.43 One of the program objectives is the delivery of the citizenship program within the parameters set by government. The parameters encompass the legislative requirements underpinning the Government’s citizenship policy, including that the Minister must be satisfied of the identity of each applicant prior to conferral of citizenship. The PBS, and Annual Report, do not refer to the identity requirement set by the Act, nor do they include objectives or indicators that specifically relate to these requirements.

2.44 Monitoring and reporting on the quality and consistency of decisions resulting in the conferral of citizenship, including decisions related to identity verification, is central to the integrity of the department’s program delivery. The indicator—percentage of refusal decisions overturned through an appeal process—provides some insight into the quality of the department’s decision-making process for refusing applications. However, refusals account for only a small percentage of citizenship decisions. There is no indicator that reports on the quality of approval decisions. In 2013–14, approval decisions represented the majority of citizenship conferral decisions (83 per cent of conferral applications). As such, there is no analysis of decision-makers’ assessments or reporting to confirm that the correct decision was made. While the department undertakes quality assurance activities69, these quality checks only focus on whether key processes have been followed but do not determine whether the decisions made at key points of the process are fully supported by the information reviewed.70

External reporting

2.45 DIBP reports publicly on its performance in delivering the citizenship program in its annual reports, which include:

- the number of applications for citizenship approved, and the number of people conferred as citizens (see paragraphs 1.9 to 1.12 and Figure 1.2);

- outlining key changes to the Citizenship Program, such as DIBP’s partnership arrangement with the Department of Human Services and amendments to the Act, as well as challenges faced by the increased rate of applications received for citizenship and the corresponding demand for citizenship ceremonies; and

- high level information about budget allocation and expenditure; the number of applications approved for citizenship; and the number of applicants that become Australian citizens.

2.46 The department also reports on its performance in delivering citizenship against the program’s three KPIs (as outlined in Table 2.2). From 2010–11 to 2013–14, DIBP consistently met the targets for two of the three citizenship performance indicators—percentage of refusal decisions overturned through an appeal process, and increased awareness of Australian citizenship.

2.47 However, between 2010–11 and 2013–14, the department only once met the target of 80 per cent of client conferral applications being decided within the 60 day service delivery standard, in 2011–12 (82 per cent).71 In 2012–13, there was a significant decline (63 per cent) in DIBP’s result against the service delivery target. The department’s annual report comments that this result was ‘due to a sustained increase in the number of applications received’, highlighting a 33 per cent increase in applications received from 2011–12 to 2012–13. In 2013–14, DIBP’s performance against the service delivery target was 75 per cent. From 1 July 2014, DIBP’s service standard for processing conferral applications is for 80 per cent to be decided within 80 days.

Internal management reporting

2.48 For internal management reporting, DIBP produces each month three main reports—an Executive Management Report; a Citizenship Applications Report (otherwise referred to as the ‘Yellow Book’); and a Quality Report.72 Table 2.3 outlines the content and purpose of these reports, as well as their frequency.

Table 2.3: Citizenship Program internal management reports

|

Internal management reports |

Content and purpose |

|

Executive Management Report (EMR) |

Provides quantitative statistical reporting covering: application caseload processing, including performance against the service delivery standard; administration of the citizenship test; quality activities; Citizenship Help Desk inquiries; litigation caseload; feedback data; and Citizenship Wizard webpage views. The EMR is disseminated to relevant management staff including the two Deputy Secretaries responsible for delivery of the Citizenship Program. |

|

Citizenship Applications Report (Yellow Book)1 |

Provides quantitative reporting on application processing and workflow statistics for each citizenship application stream and each STO, including age analysis of applications on-hand. The Yellow Book informs the EMR and as well as high level reporting to the Minister and is disseminated to relevant management staff. |

|

Quality Report2 |

Provides a high level snapshot of performance against the citizenship quality activity targets and benchmarks, including whether the network achieved the overall sample rate of five per cent of applications. For quality activities associated with delivery of the citizenship test by the Department of Human Services, DIBP also maintains a spreadsheet with results against the basic administrative checks undertaken weekly. While results are not provided in a formal report, they are however discussed at fortnightly operational meetings. |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIBP internal management reports.

Note 1: A weekly scorecard is also produced for citizenship conferral applications that shows each STOs’ performance against application processing workloads as well as tracking the number of citizenship tests administered and quality activities completed.

Note 2: A more detailed discussion of the Quality Report is provided in the quality assurance section of Chapter 3.

2.49 These reports contain high level, quantitative management information. The data reported in the EMR and Yellow Book largely focuses on citizenship application processing statistics, providing some insight with regard to workload management. While useful, the EMR and Yellow Book do not include analysis of emerging issues or trends that would assist DIBP to better understand processing delays, complex scenarios or emerging issues that may necessitate changes to administrative arrangements or policy.

2.50 The Evidence Processing Unit, responsible for processing applications for evidence of citizenship73, informed the ANAO that there were issues with the reliability of figures presented in the Yellow Book for 2013–14 and 2014–15. Until 21 March 2014, one application outcome ‘Citizenship Evidence Not Issued’ was available through the Integrated Client Service Environment (ICSE) (DIBP’s data storage system) to record both refused and invalid applications for evidence of citizenship. DIBP rectified this limitation by creating two new outcomes (invalid and refused) and conducted remedial work to correct errors in reporting. As at 31 January 2015, DIBP advised that 35 cases were still to be corrected.

2.51 DIBP has a range of quantitative performance indicators and a number of reporting mechanisms, for both external and internal stakeholders, to capture and report on its performance in delivering the Citizenship Program. However, the current performance measures and reporting arrangements do not inform key stakeholders of the department’s performance across key areas of the program, such as the quality of decisions for citizenship conferrals, and the management of risks to the program. Expanding the KPIs to cover the quality of citizenship decisions, and reporting against these would provide the department with greater assurance that the Citizenship Program is meeting its legislated requirements, including that the Minister must not approve a person becoming an Australian citizen unless satisfied of the identity of the person.

Recommendation No.2

2.52 To more effectively assess and report on the objectives of the Citizenship Program, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Immigration and Border Protection develops and reports against key performance indicators assessing the quality of the department’s citizenship decisions.

DIBP’s response: Agreed.

2.53 The department will develop and implement key performance indicators to more effectively assess the quality of citizenship decisions and will identify appropriate means to report on the department’s performance against them.

Conclusion

2.54 DIBP has put in place administrative arrangements to support decision-makers undertaking identity verification activities for the Citizenship Program. However, there is scope to improve key components of the department’s administrative arrangements—managing risks, policy guidance and performance reporting—to promote greater consistency in decision-making and assurance of the reliability of assessment outcomes.

2.55 The recently introduced Integrity Partnership Agreement—Citizenship Program (IPA) provides a starting point for a structured approach to managing risk in the program. However, the IPA needs to be tailored to the requirements of the Citizenship Program and include quantifiable measures to assess the effectiveness of the risk treatments being implemented.