Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Use and Administration of Wage Subsidies

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Wage subsidies have been a long-standing part of employment programs in Australia. They aim to increase employment opportunities for job seekers by providing a financial incentive to employers, primarily by contributing to the initial costs of hiring a new employee.

- This audit was an opportunity to examine the effectiveness of the administration of wage subsidies, and the extent to which DESE monitored and evaluated if wage subsidies improved employment opportunities for employment program participants, by assisting job seekers into work and meeting employer needs.

Key facts

- In 2020–21 wage subsidies were available to employers of up to $6,500, or up to $10,000, depending on the job seeker cohort. In 2020–21, a wage subsidy placement had to average at least 20 hours of work per week over a 26-week period, and can be casual, part-time or full-time.

What did we find?

- The Department of Education, Skills and Employment’s (DESE) administration of wage subsidies is largely effective.

- DESE’s contractual framework, program guidelines, systems, and compliance program support the assessment, processing and payment of wage subsidies.

- The monitoring, reporting and evaluation of wage subsidies have been largely effective in ensuring policy objectives are being achieved.

What did we recommend?

- One recommendation was made to DESE related to performance measurement and reporting.

- DESE agreed to the recommendation.

$1,006.4m

Total expenditure on wage subsidies from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2021

258,306

Total wage subsidy placements from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2021

50%

Average percentage of participants for whom a 26 week employment outcome was payable in a wage subsidies placement between 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2021

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Wage subsidies are a discretionary financial incentive to encourage employers to hire eligible job seekers by contributing to the initial costs of hiring a new employee. Wage subsidies can help overcome employers’ reluctance to hire certain groups by compensating employers for real or perceived lower levels of productivity, can increase employment opportunities for disadvantaged job seekers, and lower the reliance on income support. Wage subsidies also contribute to the broader employment program objectives to promote stronger workforce participation and help job seekers move from welfare to work.

2. Wage subsidies in various forms have formed part of Australian Government employment programs since 1976. The current wage subsidies were introduced progressively, beginning with the introduction of the Restart wage subsidy in 2014–15, and the implementation of the jobactive employment program in 2015–16.

3. Wage subsidies are offered under a number of employment programs that includes: jobactive; Transition to Work; Youth Jobs PaTH; ParentsNext; Disability Employments Services; and the Community Development Program.

4. In 2020–21, the wage subsidy amount (either up to $6,500 or up to $10,000) depended on which employment services cohort a job seeker was categorised under: aged between 15–24 years; aged between 25–29 years; 50 years of age and over; Indigenous; Parents; and Long-Term Unemployed.

5. To receive a wage subsidy in 2020–21, an eligible employer must offer an employment placement to an eligible job seeker and the placement must average at least 20 hours of work per week over the 26-week wage subsidy period, with an expectation that the employment will extend beyond the 26-week period; and the employment can be casual, part-time or full-time.

6. Wage subsidies are the responsibility of the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) and are administered through contracted employment services providers.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. Job seekers who have been unemployed for a long time generally experience greater difficulty finding subsequent work, as their paid work prospects decline.1 This audit is an opportunity to examine the effectiveness of the administration of wage subsidies, and the extent to which DESE monitored and evaluated if wage subsidies improved employment opportunities for employment program participants, by assisting job seekers into work and meeting employer needs. This audit also has the potential to inform any changes to wage subsidies that could be considered as part of DESE’s reforms to employment programs, currently in the development and piloting phase and due for implementation in July 2022.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the DESE’s arrangements in administering wage subsidies linked to employment programs.

9. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following criteria were applied:

- Are wage subsidies assessed, processed and paid in accordance with program requirements and contractual obligations?

- Is the application and use of wage subsidies effectively monitored, evaluated and reported to ensure policy objectives are being achieved?

Conclusion

10. DESE’s administration of wage subsidies is largely effective.

11. DESE’s contractual framework, program guidelines, systems, and compliance program largely supports the assessment, processing and payment of wage subsidies in accordance with program guidelines. Guidelines and supporting documentation are clear and updated at regular intervals. System controls support the accurate processing and management of wage subsidies. There is a largely effective compliance program in place, based on risk. However, the results of the Rolling Random Sample (RRS) for wage subsidies is consistently below the overall compliance target.

12. The monitoring, reporting and evaluation of wage subsidies have been largely effective in ensuring policy objectives are being achieved. Evaluation and funding arrangements are appropriate, however monitoring and performance reporting could be improved as reporting is focused on participation outputs rather than the impact of wage subsidies on improving employment outcomes. The final evaluation report is outstanding and could more clearly feed into policy development.

Supporting findings

Guidance, systems and compliance

13. DESE has an appropriate contractual framework and clear wage subsidy guidelines that are regularly updated. Changes to the wage subsidy guidelines are communicated to providers and to DESE regional contract and account managers to support the correct administration of wage subsidies. DESE regional contract and account managers have access to a range of additional guidance and are supported by the national office in resolving provider queries.

14. The system used to manage employment programs, the Employment Services System (ESSWeb), supports the accurate processing and management of wage subsidies. ESSWeb contains reliable system controls that maximise automated completion of key processes and minimise manual interventions.

15. DESE has a largely effective compliance program for employment programs, including wage subsidies, based on risk. However, the results of the RRS for wage subsidies consistently do not meet the overall 95 per cent compliance target. DESE should document, and seek endorsement of, the methodology for the RRS.

Performance, evaluation and funding arrangements

16. DESE’s reporting on wage subsidies is focused on outputs. A more effective method of measuring wage subsidy performance was developed as part of the jobactive evaluation, however this method is not being used for ongoing monitoring and performance reporting. Wage subsidy performance contributes to DESE Corporate Plan employment outcomes performance measures and to jobactive provider performance ratings, but it is not possible to quantify the extent of that contribution.

17. DESE developed an evaluation strategy for jobactive when the program was designed, and there was suitable coverage of wage subsidies in the draft jobactive evaluation report. There is some evidence that evaluation findings and related recommendations have informed policy changes to wage subsidies, although the final evaluation report has not been released and is overdue.

18. The funding arrangements for wage subsidies have been monitored and adjusted over time in line with the policy changes and program requirements, and were partly informed by lessons learned or evaluation findings.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.27

Under the New Employment Services Model, DESE develops methods to improve the monitoring and reporting of wage subsidy impact against the employment program policy objective.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment response: Agreed.

Summary of the Department of Education, Skills and Employment’s response

19. DESE’s summary response is provided below and its full response is included at Appendix 1.

The Department of Education, Skills and Employment welcomes this report. The report recognises the significant program of work the Department has in place to assure the effective administration of wage subsidies and found this to be largely effective.

As highlighted in the report, the Department’s contractual framework, program guidelines, systems and compliance program largely support the assessment, processing, and payment of wage subsidies in accordance with program guidelines and contractual obligations. The report also finds that the monitoring, reporting and evaluation of wage subsidies have been largely effective in ensuring policy objectives are being achieved.

The Department acknowledges that enhancements to monitoring can be considered in future arrangements for employment programs, to more effectively assess wage subsidy performance against policy objectives. The recommendation to improve monitoring and reporting of wage subsidy impact supports the Department’s ongoing effort to enhance performance measures and reporting on wage subsidies.

20. Appendix 2 sets out improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of the audit.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Wage subsidies are a discretionary financial incentive to encourage employers to hire eligible job seekers by contributing to the initial costs of hiring a new employee. Wage subsidies can help overcome employers’ reluctance to hire certain groups by compensating employers for real or perceived lower levels of productivity2, can increase employment opportunities for disadvantaged job seekers, and lower their reliance on income support. Wage subsidies also contribute to the broader employment program objectives to promote stronger workforce participation and help job seekers move from welfare to work.3

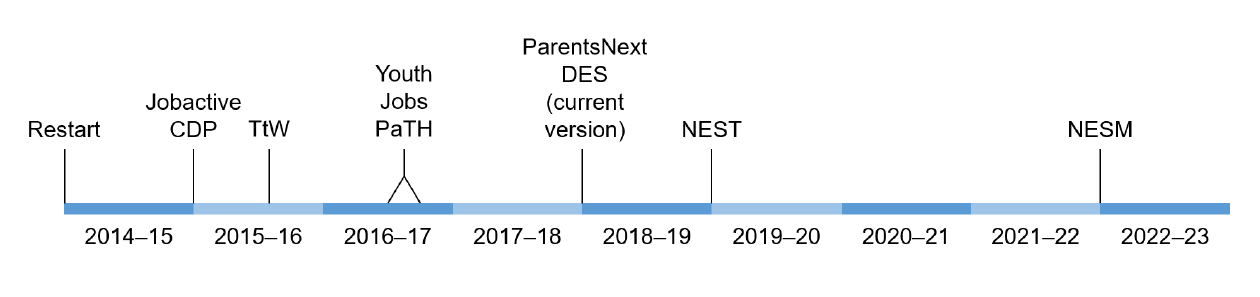

1.2 Wage subsidies in various forms have formed part of Australian Government employment programs since 1976.4 The current wage subsidies were introduced progressively, beginning with the introduction of the Restart wage subsidy in 2014–15, and the implementation of the jobactive employment program in 2015–16. Figure 1.1 provides a timeline of the introduction of the employment programs associated with wage subsidies.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of employment programs

Note: Program names are set out in full in Table 1.1, with the exception of NEST that is the New Employment Services Trial, and NESM that is the New Employment Services Model.

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.3 In 2020–21 and 2021–22 the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) administered wage subsidies under a number of employment programs that includes the programs set out in Table 1.15:

Table 1.1: Employment programs that offer wage subsidies

|

Program |

Description |

|

jobactive |

The mainstream employment service for people on income support or eligible volunteers, that connects job seekers with employers through a network of employment services providers. |

|

Transition to Work (TtW) |

This program provides pre-employment assistance to young people aged 15–24 who have disengaged from work and study and are at risk of long-term welfare dependency. |

|

Youth Jobs PaTH (Prepare-Trail-Hire) |

Supports young people in receipt of an activity-tested income support payment to move into employment. It has three elements: Employability Skills Training (15–24 years of age); voluntary internships (17–24 years of age); and a Youth Bonus Wage Subsidy to support employment of young people (15–24 years of age). |

|

ParentsNext |

A pre-employment program to support parents and carers in receipt of the Parenting Payment to find work before their youngest child reaches school age. |

|

Disability Employment Services (DES) |

This program provides pre-employment assistance and ongoing support to people with a disability, injury or illness. DES is administered by the Department of Social Services. |

|

Community Development Program (CDP) |

The employment program for Indigenous job seekers in remote Australia, administered by the National Indigenous Australians Agency. |

Source: DESE Employment Programs.

Wage subsidy types and eligibility

1.4 A range of wage subsidies are available to eligible employers hiring eligible job seekers/participants.6 In 2020–21, the wage subsidy payment amount depended on which employment services cohort a participant was categorised under. The employment services cohorts are targeted at specific groups of job seekers, as set out in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Wage subsidy cohort types, employment program and eligibility 2020–21

|

Subsidy cohort |

Employment program and eligibility |

Wage subsidy funding amount |

|

Indigenous Australians |

jobactive, TtW or ParentsNext Immediate eligibility for a wage subsidy once commenced in jobactive, TtW, ParentsNext, New Employment Services Trial (NEST) and Online Employment Services (OES) Have Mutual Obligation Requirements at the time the wage subsidy placement commenceda |

Up to $10,000 |

|

50 years of age and over |

Restart Received any Services Australia or Department of Veterans’ Affairs income support payment or pension (including Age Pension or Austudy) for the past six months Registered with a jobactive, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, DES or CDPb, NEST, OES or the Volunteer Online Employment Services Trial (VOEST) provider at the time the wage subsidy agreement is created |

Up to $10,000 |

|

15 to 24 years of age |

Youth Bonus Have received employment services from jobactive, ParentsNext Intensive Streamc, TtW, NEST, OES, DES or CDPb continuously for the past six months Registered with a jobactive, TtW, ParentsNext Intensive Streamc, NEST or OES provider at the time the wage subsidy agreement is created Have Mutual Obligation Requirementsc at the time the wage subsidy placement commenced |

Up to $6,500 (Stream A)d Up to $10,000 (Streams B & C)d |

|

25 to 29 years of age |

Youth Have received employment services from jobactive, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, TtW, NEST, OES, DES or CDPb continuously for the past six months Registered with a jobactive, TtW, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, NEST or OES provider at the time the wage subsidy agreement is created Have Mutual Obligation Requirements at the time the wage subsidy placement commenced |

Up to $6,500 |

|

Parents |

Parents receiving Parenting Payment or principal carers receiving an income support payment Have received employment services from jobactive, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, TtW, NEST, OES, DES or CDPb continuously for the past six months Registered with a jobactive, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, NEST or OES provider at the time the wage subsidy agreement is created Have Mutual Obligation Requirements at the time the wage subsidy placement commenced |

Up to $6,500 |

|

Long Term Unemployed (LTU) |

Have received employment services from jobactive, NEST, OES, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, DES or CDPb continuously for the past 12 months Registered with a jobactive, ParentsNext Intensive Stream, NEST or OES provider at the time the wage subsidy agreement is created Have Mutual Obligation Requirements at the time the wage subsidy placement commenced |

Up to $6,500 |

Note a: Mutual obligation requirements are tasks or activities that job seekers must undertake in order to receive income support through JobSeeker, Youth Allowance, Parenting Payment or Special Benefit.

Note b: The DES program is administered by the Department of Social Services, and CDP is administered by the National Indigenous Australians Agency.

Note c: Prior to 1 July 2021, only ParentsNext Intensive stream participants were eligible for wage subsidies. From 1 July 2021, the two streams of ParentsNext (Intensive and Targeted) were combined and all ParentsNext participants became eligible for wage subsidies if they met the relevant eligibility criteria.

Note d: A Youth Bonus Wage Subsidy of up to $6,500 could be paid for a participant in Stream A (the most job-ready participants). A subsidy of up to $10,000 could be paid for a participant in Stream B (some barriers to employment) or Stream C (multiple and complex barriers to employment), a Transition to Work participant in receipt of an income support payment, or a participant in ParentsNext.

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.5 As shown in Table 1.2, in 2020–21 wage subsidies provided a higher level of funding support to job seekers identified by DESE as having greater barriers to employment. In the 2021–22 DESE Portfolio Budget Statements, employment services programs were delivered under the outcome to foster a productive and competitive labour market through policies and programs that assist job seekers into work and meet employer needs.7

1.6 Under policy changes announced in the 2021–22 Budget, the jobactive, TtW and ParentsNext program cohorts are able to access a wage subsidy of up to $10,000 from 1 July 2021.8 The aim is to increase the incentives for employers to hire disadvantaged job seekers, streamline the administration of wage subsidies and simplify arrangements for employers.

Administration of wage subsidies

1.7 To receive a wage subsidy in 2020–21, an eligible employer must offer an employment placement9 to a job seeker who has been a participant in one of the employment programs in Table 1.1 above. The placement must average at least 20 hours of work per week over a 26-week wage subsidy period, with an expectation that the employment will extend beyond the 26-week period; and can be casual, part-time or full-time. The wage subsidy paid to the employer cannot be more than 100 per cent of the participant’s wage. Based on the July 2021 national minimum wage rate of $20.33 per hour10, the wage for an average of at least 20 hours of work per week over a 26-week wage subsidy period is $406.66 per week, and $10,571.60 in the 26-week period.

1.8 Employment services providers11 are not required to offer a wage subsidy even if all eligibility criteria are satisfied. Whether a subsidy is offered depends on the needs and preferences of the participant and the employer, and whether the provider considers that a wage subsidy would be an effective incentive.

1.9 The employer enters into a wage subsidy head agreement with an employment services provider, with a schedule agreement attached for each participant being offered a wage subsidised placement. The provider then makes instalment payments to the employer at agreed intervals (fortnightly, monthly, quarterly, or at the end of the wage subsidy period for the total amount), after the employer has provided documentary evidence that the participant was employed in line with the wage subsidy agreement conditions and the claim does not exceed 100 per cent of the participant’s wages.

1.10 Providers manage the administration (including payment) of wage subsidies using the Employment Services System (ESSWeb), DESE’s system for managing employment programs. Providers make wage subsidy payments to employers from the provider’s funds and then claim reimbursement from DESE after making wage subsidy payments to employers.

1.11 Any employer is eligible to receive a wage subsidy if they are a legal entity with a valid ABN unless they:

- have been suspended or excluded from receiving wage subsidies;

- are the provider’s own organisation; or

- are an Australian, state or territory government entity.

1.12 An employer cannot receive a wage subsidy for a participant who has previously been employed by that employer, if they are a family member of the employer, or if they displace an existing employee, and a participant can only attract one wage subsidy at any given time.

1.13 DESE’s Incentives and Investments Branch is responsible for wage subsidies operational policy, supported by the Assurance Coordination Branch, the Economics and Employment Services Reporting Branch, and the Employment Research and Evaluation Branch that are respectively responsible for compliance, performance reporting and evaluation. Account and contract managers in DESE’s state and territory offices are responsible for liaising with employment services providers, including in respect of wage subsidies.

1.14 From April 2020, job seekers were referred to Online Employment Services (OES), an online employment services webpage introduced in response to the increase in demand for employment services resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, and can seek additional support from the Digital Services Contact Centre (DSCC). The OES and DSCC, in some form, will continue to operate under the New Employment Services Model (NESM) when it is introduced on 1 July 2022.

Changes to wage subsidies from 1 July 2022

1.15 Following the NEST that commenced from 1 July 2019 in Adelaide South in South Australia, and the Mid North Coast in New South Wales, NESM is being developed and is due to commence on 1 July 2022.

1.16 In the NESM, wage subsidies will only be available to participants who have been registered with an Enhanced Services12 provider for six months. Indigenous job seekers in Enhanced Services (and job seekers who have been in Digital Services for 12 months or more who have moved to Enhanced Services) will have immediate access to a wage subsidy upon commencement in Enhanced Services. The aim is to target wage subsidies to the most disadvantaged job seeker cohort. Additionally, the minimum average hours a participant needs to work will be reduced from 20 hours per week to 15 hours per week, and the duration of the wage subsidy placement will be negotiable between providers and employers to allow the maximum amount offered to be up to $10,000, and the length of the wage subsidy agreement to vary.

Wage subsidies use and expenditure

1.17 Figure 1.2 sets out the number of DESE administered employment program annual placements made with a wage subsidy since 2014–15, broken down by program.

Figure 1.2: Wage subsidy placements by year and program

Source: DESE wage subsidy program dashboard.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 Job seekers who have been unemployed for a long time generally experience greater difficulty finding subsequent work, as their paid work prospects decline.13 This audit is an opportunity to examine the effectiveness of the administration of wage subsidies, and the extent to which DESE monitored and evaluated if wage subsidies improved employment opportunities for employment program participants, by assisting job seekers into work and meeting employer needs. This audit also has the potential to inform any changes to wage subsidies that could be considered as part of the DESE’s reforms to employment programs, currently in the development and piloting phase and due for implementation in July 2022.

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DESE’s arrangements in administering wage subsidies linked to employment programs.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following criteria were applied:

- Are wage subsidies assessed, processed and paid in accordance with program requirements and contractual obligations?

- Is the application and use of wage subsidies effectively monitored, evaluated and reported to ensure policy objectives are being achieved?

1.21 The focus of the audit was on wage subsidies available in 2020–21 and 2021–22, across the employment programs and associated cohorts set out in Table 1.1 and Table 1.2. The administration of wage subsidies for all employment programs were not examined under the audit sub-criteria as the associated eligibility criteria, wage subsidy payment amounts, and the required length of employment were largely consistent across the employment programs and cohorts, regardless of which cohort or program the wage subsidy is applied under.

1.22 The performance of the employment programs that wage subsidies are attached to — jobactive, Youth Job PaTH, Transition to Work, Disability Employment Services, ParentsNext and the Community Development Programme — is not in scope for the audit.

Audit methodology

1.23 The audit involved:

- reviewing the policies, procedural guidelines and processes used to administer wage subsidies across employment programs;

- analysing service provider performance information and any participant outcome information relating to wage subsidies;

- reviewing system controls;

- reviewing compliance and assurance activities;

- examining documentation provided for the budget process; and

- discussions with key staff.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $295,000.

1.25 The team members for this audit were Renina Boyd, Evan Lee, Sonya Carter and Peta Martyn.

2. Guidelines, systems and compliance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) assessed, processed and paid wage subsidies in accordance with program requirements and contractual obligations.

Conclusion

DESE’s contractual framework, program guidelines, systems, and compliance program largely supports the assessment, processing and payment of wage subsidies in accordance with program guidelines. Guidelines and supporting documentation are clear and updated at regular intervals. System controls support the accurate processing and management of wage subsidies. There is a largely effective compliance program in place, based on risk. However, the results of the Rolling Random Sample (RRS) for wage subsidies is consistently below the overall compliance target.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO suggested that DESE documents the approved methodology for the RRS; and reflects in the next Wage Subsidies Assurance Workbook that the Wage Subsidies Risk Monitoring (WSRM) application is used as a research tool and is not a discrete assurance activity.

2.1 Effective administration of wage subsidies ensures that the correct amounts of wage subsidy funding are paid to eligible employers only, and the use of wage subsidies helps to contribute to improved employment outcomes for disadvantaged employment program participants. To determine whether wage subsidies are assessed, processed and paid in accordance with contractual obligations and program guidelines, the ANAO examined:

- contractual frameworks and program guidelines;

- the IT system and supporting processes; and

- the compliance program.

Has DESE established appropriate contractual frameworks and guidance to support the correct administration of wage subsidies?

DESE has an appropriate contractual framework and clear wage subsidy guidelines that are regularly updated. Changes to the wage subsidy guidelines are communicated to providers and to DESE regional contract and account managers to support the correct administration of wage subsidies. DESE regional contract and account managers have access to a range of additional guidance and are supported by the national office in resolving provider queries.

2.2 Developing clear and comprehensive program guidelines that are consistent with the policy objectives assists in accurate administration of the program and quality decision-making. Guidelines should be reviewed regularly to ensure they address program implementation and delivery issues, remain relevant, and reflect feedback from users of the guidance. Clear alignment between policy, guidance, contractual frameworks and administrative systems, facilitates compliance with policy and process requirements.

Wage Subsidies Guideline

2.3 The principal guideline relating to the administration of wage subsidies is the Managing Wage Subsidies Guideline. The structure of the Guideline is set out in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: Structure of the Managing Wage Subsidies Guideline

|

Section |

Comments |

|

Wage Subsidy Agreement Eligibility Requirements |

Includes requirements for employers and placements |

|

Offering Wage Subsidies |

States that wage subsidies are used at the discretion of providers |

|

Using Employment Fund Credits for Wage Subsidies |

Sets out requirements in relation to the use of the Employment Fund General Account |

|

Negotiation of Wage Subsidy Agreements |

States that providers must enter into a head agreement with each employer and a schedule agreement for each participant Sets out ‘system steps’ required to create an agreement in ESSWeb |

|

Payments to Wage Subsidy Employers |

Sets out requirements in respect of change of business ownership, payments for early terminations and concurrent funding from other wage subsidy programs (e.g. state government programs) |

|

Claims for Reimbursement |

Sets out requirements for reimbursement claims, including time requirements, override requests, managing Employment Fund credits for ended wage subsidy agreements and recovery of reimbursement claims |

|

Managing Wage Subsidy Agreements for Participants |

Discusses support for participants on wage subsidies and managing agreements on behalf of another provider |

|

Summary of Documentary Evidence |

Summary of documentary evidence requirements |

|

Table 1 — Wage Subsidy Types and Participant Eligibility |

Sets out wage subsidy types and eligibility requirements for participants |

Source: ANAO analysis of Managing Wage Subsidies Guideline, version 5.0, May 2021.

2.4 The most recent version of the Guideline, version 5.0, was published on 27 May 2021 and came into effect on 1 July 2021. The Guideline can be accessed by providers on the online Provider Portal, a key channel of communication with employment services providers. The Guideline is also available on DESE’s website.

2.5 The Guideline is clear in setting out the wage subsidy requirements. It is logically structured and provides assistance to providers. For instance, ‘system steps’ are highlighted throughout the Guideline to provide end-to-end guidance on using DESE’s IT system, the Employment Services System (ESSWeb), to manage wage subsidies. A sample wage subsidy agreement and schedule are available on the provider portal for providers to use as a reference.

2.6 The Guideline has been regularly updated since its introduction in January 2017, with 10 versions over a four and a half year period. Changes to the Guideline relate to policy changes, or to clarify requirements and improve readability. A version history of the Guideline is set out in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Version history of Managing Wage Subsidies Guideline

|

Version |

Publication date |

Effective date |

Key changes from previous version |

|

1.0 |

Not stated |

1 January 2017 |

Not applicable — initial version |

|

2.0 |

19 June 2017 |

1 July 2017 |

Substantial restructuring, rewording and reformatting ‘System steps’ introduced to clarify how to navigate ESSWeb |

|

2.1 |

25 July 2017 |

25 July 2017 |

Minor changes to formatting and eligibility requirements |

|

2.2 |

7 December 2017 |

1 January 2018 |

Policy update: Indigenous participants are eligible for $10,000 wage subsidy |

|

2.3 |

31 May 2018 |

1 July 2018 |

Documentary evidence requirements highlighted throughout text Some restructuring and rewording |

|

3.0 |

7 December 2018 |

2 January 2019 |

Policy update: Abolition of the separate Employment Fund Wage Subsidy Account — wage subsidies are to be reimbursed from the Employment Fund General Account Policy update: Changes to reflect the introduction of the Australian Apprentice Wage Subsidy |

|

3.1 |

8 February 2019 |

4 March 2019 |

Policy update: Paid work trials are limited to two weeks Adds documentary evidence requirements for verifying approved leave |

|

3.2 |

30 May 2019 |

1 July 2019 |

Minor changes to formatting |

|

4.0 |

12 November 2019a |

2 October 2019a |

Policy update: Removal of the kickstart paymentb Policy update: Employers are prohibited from receiving a wage subsidy in respect of a participant that they have previously employed (this prohibition previously applied only if the participant was previously employed within the last six months) |

|

5.0 |

27 May 2021 |

1 July 2021 |

Policy update: All wage subsidies increased up to $10,000 Policy update: References to ParentsNext Intensive stream removed to reflect merging of ParentsNext streams Clarification of approved leave requirements New section on recovery of reimbursement claims Wage subsidy types and participant eligibility presented in a table (as opposed to a list) Additional clarity, restructuring and streamlining changes throughout Guideline to improve readability. |

Note a: Version 4.0 of the Guidelines was published after it came into force. DESE advised that clearance and publication of Version 4.0 was managed in tandem with the clearance for the Managing Wage Subsidies for the Online Employment Services Trial (OEST) Employer Guideline, due to the similarity in content of both documents. The finalisation of the OEST Guideline was delayed, resulting in delayed publication of version 4.0 of the Guidelines.

Note b: The kickstart payment was introduced in January 2017 to provide an additional incentive for employers, allowing up to 40 per cent of the total wage subsidy to be paid to employers four weeks after a participant commenced in an eligible placement.

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.7 DESE communicates changes to the Guideline to providers by placing news items on the Provider Portal. DESE’s contract and account managers, who are responsible for providing support to the employment service providers in their regions, are informed of Guideline changes through emails and information from program areas through a central coordination point in the DESE National Office.

2.8 In response to the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, DESE issued advice to providers on 12 and 15 May 2020 that in specific circumstances, the department would consider waiving wage subsidy requirements relating to approved leave and pre-existing employment for wage subsidy agreements that were active at the onset of COVID-19.14 COVID-19 waivers were communicated to providers on the Provider Portal.

Contractual framework

2.9 The contractual requirements between DESE and providers for the employment services programs is set out in the following documents:

- Community Development Program Head Agreement;

- Disability Employment Services Grant Agreement;

- jobactive Deed 2015–2022;

- ParentsNext Deed 2018–2024; and

- Transition to Work Deed 2016–2022.

2.10 The contractual documents set out: definitions and interpretations; requirements for financial matters; performance; information management and deed administration; requirements for service delivery; and payments to providers.

2.11 Wage subsidy requirements are not specified in detail in the contractual documents as they refer providers to the Managing Wage Subsidy Guideline. For example, clause 89 of the jobactive Deed states that providers must ‘offer, manage, deal with enquiries and report on Wage Subsidies in accordance with any Guidelines’, and the requirements set out in the Deed are ‘Subject to any contrary provision specified in any Guidelines’. The other deeds contain similar wording except for the Community Development Program (CDP) Head Agreement that does not refer to wage subsidies.

Support for DESE staff, employment services providers and employers

Resources for departmental staff

2.12 DESE’s Incentives and Investments Branch is responsible for operational wage subsidies policy matters and the Labour Market Policy Branch is responsible for strategic wage subsidies policy. Operational responsibility for managing and supporting providers is assigned to contract managers, regional account coordinators and account managers, who are located in DESE’s state and territory offices.

2.13 Contract managers, regional account coordinators and account managers are responsible for monitoring and communicating with providers at the local level. Account managers oversee contract managers and regional account coordinators, and are responsible for communicating with providers at the organisational level. Contract and account management responsibilities are set out in DESE’s documentation. DESE contract managers, regional account coordinators and account managers can use state office handbooks or online resources on the Provider Portal to support the administration of wage subsidies. These resources include the Managing Wage Subsidies Guideline, relevant contracts and information on performance and assurance.

Resources for providers

Question Manager form

2.14 Providers can receive support from DESE through the Question Manager form in ESSWeb and through the Wage Subsidies mailbox. Question Manager is described by DESE as its preferred mechanism for lodging and resolving policy and operation questions. Providers can lodge questions through the Question Manager form to be answered by a departmental officer.

2.15 Questions and responses on Question Manager are recorded and DESE staff and providers can search through past questions to establish whether a similar question has already been asked and answered. DESE advised that for privacy reasons, a provider can only access questions asked by that provider.

2.16 Forty-three questions relating to wage subsidies were lodged and resolved in Question Manager from the introduction of the current version of Question Manager in November 2020, to 5 May 2021.

2.17 DESE aims to respond to questions lodged in Question Manager within 10 business days. Of the 43 questions that had a status of resolved and closed, 38 received responses within this timeframe (88 per cent), and 40 questions received responses which were clear and directly addressed the question. Two responses were not directly relevant to the question asked. One response gave an inaccurate explanation of program requirements.15

Wage Subsidies mailbox

2.18 When DESE staff receive queries from providers which they are unable to respond to, they can use the Wage Subsidies mailbox to escalate the matter to the Wage Subsidies Team in DESE’s Incentives and Investment Branch. DESE advised that the Wage Subsidy Team may, at its discretion, communicate directly with providers via the mailbox but the preference is to liaise with providers through DESE contract and account managers.

2.19 DESE responded via the mailbox to 203 inquiries in the six months from 1 October 2020 to 31 March 2021. From a selection of 12 responses examined by the ANAO, in all cases the Wage Subsidy Team was able to resolve queries through the mailbox.

2.20 DESE aims to respond to mailbox inquiries within 10 business days. DESE advised that more complex queries that require investigation may take longer to resolve. Of the 12 responses examined, four that were lodged in March 2021 did not have a timestamp of resolution, and for the remaining eight, six were provided within 10 business days. The two remaining queries took 19 and 42 days to resolve.

Resources for employers

2.21 Providers have the primary responsibility to provide guidance and support to employers regarding wage subsidies. DESE also provides resources for employers on its website, including a wage subsidies ‘how to guide’ that is available to employers and other members of the public. The guide explains how employers can use the jobactive website to manage a wage subsidy agreement.

Do DESE’s systems support accurate processing and management of wage subsidies?

The system used to manage employment programs, the Employment Services System (ESSWeb), supports the accurate processing and management of wage subsidies. ESSWeb contains reliable system controls that maximise automated completion of key processes and minimise manual interventions.

2.22 IT systems that embed automatic validation controls and transparent processes can help to ensure effective management of payments.

Wage subsidy process

2.23 The key steps in processing a wage subsidy are set out below and the full process is depicted at Appendix 3:

- provider determines that a wage subsidy is suitable for the eligible participant and eligible employer;

- provider establishes a wage subsidy agreement and schedule with the employer (within 84 days of the employment placement commencing) and negotiates a payment schedule;

- employer provides payroll evidence and invoices to the provider to receive wage subsidy payments, and as per the payment schedule, provider pays employer;

- provider claims reimbursement of wage subsidy payments from DESE (within 56 days of the end of the wage subsidy period); and

- DESE reimburses the provider for the amount paid to the employer.

System for administering wage subsidies

2.24 ESSWeb is the IT system used by DESE to administer employment programs, including wage subsidies.

2.25 ESSWeb went live on 1 July 2015, following the introduction of the Restart program on 1 July 2014 and in preparation for the introduction of jobactive. Employment service providers access ESSWeb through the Employment and Community Services Network (ECSN), a departmental portal which provides access to other applications such as the DESE internet page, provider portal, performance dashboard and learning centre.

2.26 To create a wage subsidy schedule agreement in ESSWeb, a provider must match an eligible participant to an eligible vacancy with an employer. A wage subsidy schedule agreement must then be attached by the provider to a head agreement with the employer. Providers cannot attach a wage subsidy schedule agreement in ESSWeb without first confirming that they have signed the head agreement with the employer, which can be completed electronically in ESSWeb, or completed offline and then recorded in ESSWeb.

2.27 ESSWeb automatically assesses eligibility and determines other requirements such as the agreement end date. If ESSWeb assesses that eligibility criteria are not met, the provider may request a manual override from DESE.16

2.28 After making payments to employers, providers claim reimbursement from DESE through ESSWeb which has system controls that prevent providers claiming reimbursement unless a valid wage subsidy agreement exists. ESSWeb system controls also disallow any claim for reimbursement in excess of the remaining balance of the wage subsidy. Other key controls include data matching to ensure providers meet the criteria for each claim. Job Seeker Identification numbers, employment vacancy identifiers and referral identifiers are automatically matched by ESSWeb, and ABNs are validated with Australian Taxation Office records.

2.29 A key requirement of the Managing Wage Subsidy Guideline is that the employer and provider are to keep records of the payslip and wage subsidy payment remittance respectively. In ESSWeb it is optional to upload documentary evidence, with providers required to retain the evidence offline. Adherence to this requirement is checked in the RRS and other assurance activities (discussed from paragraph 2.57 below), or requests for providers to supply copies to DESE.

2.30 If any of the records in the sample of transactions examined in the RRS do not have documentary evidence of payment remittance attached, DESE follows up with the provider to request that it be made available within one working day. Where documentary evidence cannot be provided, DESE takes steps to recover the payment.

2.31 The option of uploading documentary evidence in ESSWeb raises the risk of fraud or poor practice of not retaining the required documentary evidence. In RRS cycle 16 (discussed further from paragraph 2.64) from the 316 transactions examined, 11 transactions (three per cent) were found to have insufficient or no evidence to support payment to the employer by the provider. DESE advised that the high compliance rates found through RRS indicate there is limited evidence to support the introduction of a mandatory documentary evidence requirement for providers.

2.32 When claims for reimbursement are made on ESSWeb, this then updates HUB (DESE’s SAP financial system) in real time. HUB processes payments each morning and batch updates ESS each night. ESSWeb to HUB reconciliations are performed automatically once a month.

2.33 There are minimal manual interventions required in standard ESSWeb wage subsidy processing, which lowers the risk of error. However, DESE account managers can make manual adjustments in exceptional circumstances, for example, special claims where a provider submits a wage subsidy reimbursement over the 56 day time limit, or to apply a workaround while a new policy and accompanying process is being embedded. If exceptional circumstances are deemed to have occurred, a DESE officer will process these claims in ESSWeb. DESE advised that special claims represent less than one per cent of total wage subsidy transactions, representing 2,787 (around one per cent) from a total of 321,578 claims from 2019 to 2021.

Is there an effective program of compliance, based on risk?

DESE has a largely effective compliance program for employment programs, including wage subsidies, based on risk. However, the results of the RRS for wage subsidies consistently do not meet the overall 95 per cent compliance target. DESE should document, and seek endorsement of, the methodology for the RRS.

2.34 A compliance strategy should be linked to the entity’s risk management and fraud control frameworks and be used to support and guide the conduct and allocation of resources, and outcomes from the assurance activities should be adequately monitored and reported.17

Assurance planning

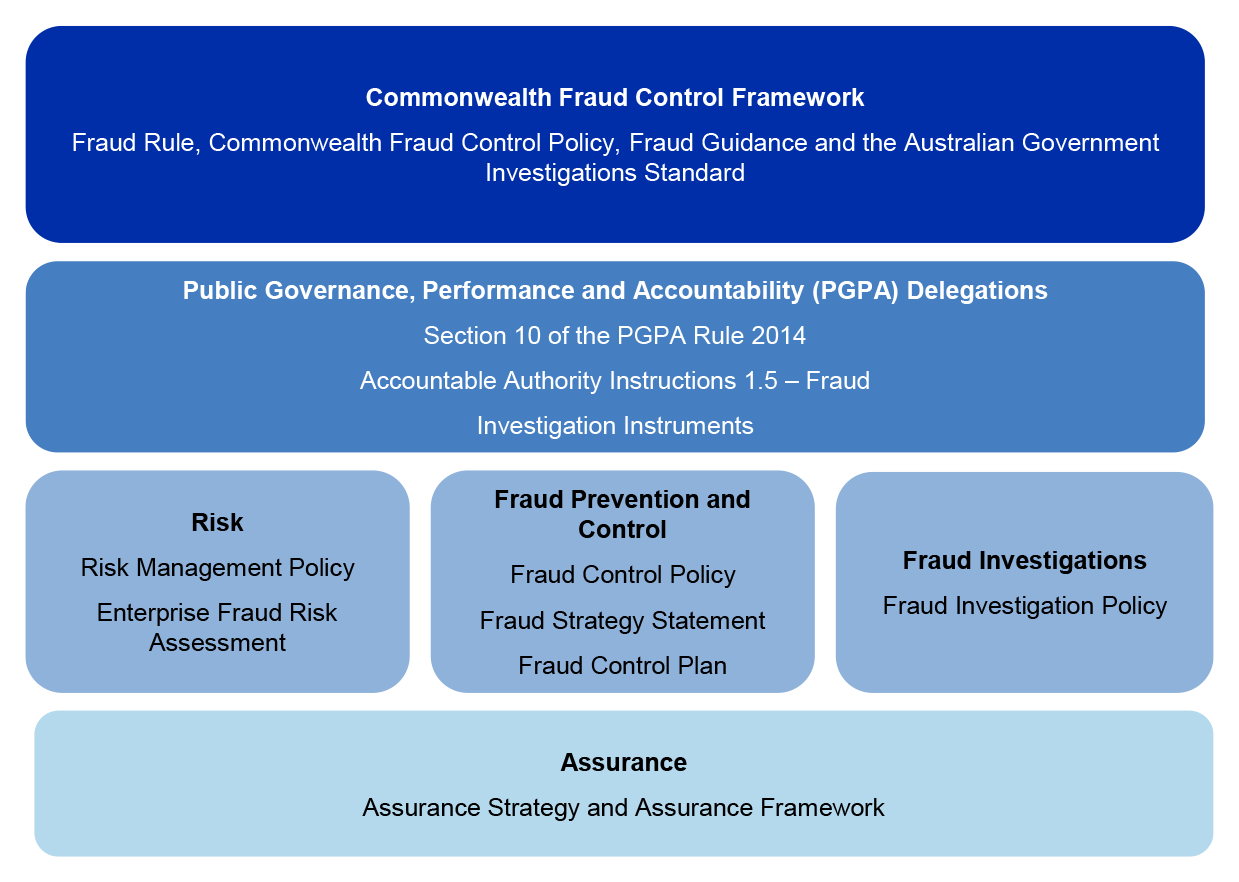

2.35 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires Commonwealth entities to establish and maintain an appropriate system of risk oversight and management.18 The assurance and compliance activities for employment programs are informed at a high level by DESE’s enterprise risk, fraud and assurance frameworks as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: DESE assurance operating environment

Source: DESE Assurance Strategy and Framework.

DESE Assurance Strategy and Assurance Framework

2.36 The DESE Assurance Strategy and Assurance Framework supports the department’s activities across the education, training and employment streams. It describes the purpose of assurance and outlines how assurance activities should be assigned and undertaken across the department. The strategy provides the principles and guidance that underpin the assurance activities, and the Framework operationalises the strategy by setting out a range of assurance activities. The DESE Assurance Strategy and Framework was updated in February 2021 and replaced the previous program-specific Employment Services Assurance Strategy 2018 and the Employment Services Assurance Framework 2019.

2.37 The strategy provides the overarching guidance to enable DESE to deliver assurance activities at an operational level, and describes how it interacts with DESE’s other governance frameworks including the Risk Management Framework and Strategy (discussed further from paragraph 2.48 below).

2.38 The strategy provides guidance on DESE’s risk-based approach to assurance and its purpose is to assure the department that its activities (policies and programs) are operating effectively. The assurance planning model includes four phases:

- Phase 1: Information gathering and analysis;

- Phase 2: Risk identification and control analysis;

- Phase 3: Plan assurance activities; and

- Phase 4: Monitoring and reporting.

2.39 The Framework outlines the assurance environment, the purpose of assurance, and the design and delivery of assurance activities, as well as the three lines of defence: business and support control processes and systems; management assurance; and independent assurance.

2.40 Assurance planning is how DESE develops program assurance plans for employment services programs.19 The process involves the following:

- Assurance Coordination Branch generates the assurance planning workbook and sends it to the program area for input;

- assurance activity recommendations are prepared for consultation with the program area;

- an assurance plan is prepared for approval by the program area SES Band 1 and Assurance Coordination Branch SES Band 1, and noted by the Program Integrity Sub-Committee for Employment Services (PISCES);

- the final plan is published on the DESE provider portal; and

- assurance activities are undertaken by the program area or Assurance Coordination Branch.

2.41 The DESE Assurance Strategy and Framework states that assurance activities should align with the program area’s risk plan and be reviewed annually unless DESE determines otherwise.

Wage subsidies assurance planning

2.42 The most recent assurance planning process for wage subsidies commenced in 2020 and was documented in the 2020–21 Assurance Planning Workbook and the 2020–21 Assurance Plan: Wage Subsidies. The assurance planning process was then deferred in 2020 due to the COVID-19 impacts and the 2020–21 Workbook and Plan was not endorsed by PISCES. However, DESE advised that with the deferral of assurance planning, program areas were notified that they were covered by their 2019–20 assurance plans, which were noted by PISCES, until the recommencement of planning in 2020–21.

Assurance Planning Workbook for wage subsidies

2.43 The draft 2020–21 Workbook was prepared as part of the partially completed assurance planning process described at paragraph 2.42 above. The draft Workbook sets out: program information such as wage subsidies budget; eligibility and roles and responsibilities; wage subsidies risk profile; previous assurance activities undertaken and any outstanding recommendations; and assurance activities for 2020–21 including the underlying risk assessment and rationale to support them.

2.44 The content of the draft 2020–21 Workbook is not materially different from that of the 2019–20 Workbook except that it: discusses the 2019–20 bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic; contains greater detail on IT systems; and identifies actions against recommendations arising from the earlier review of assurance activities. The purpose of the 2020–21 Workbook is to inform the Assurance Plan, discussed below.

Assurance Plan: Wage Subsidies

2.45 The draft 2020–21 Assurance Plan: Wage Subsidies is a two-page document which provides an overview of 2020–21 program assurance activities for wage subsidies, covering:

- wage subsidy risks from the Incentives and Investment Branch Risk Plan (discussed further from paragraph 2.53 below) and emerging assurance risks;

- the assurance approach for wage subsidies, including assurance drivers (such as payment recovery, policy development);

- ongoing monitoring activities for 2020–21; and

- assurance activities for 2020–21.

2.46 The previously approved 2019–20 Assurance Plan: Wage Subsidies was prepared using a template from the former Employment Services Assurance Framework. As the 2020–21 Assurance Plan was not endorsed by PISCES, the Incentives and Investments Branch continued to operate under the 2019–20 Plan. The draft 2020–21 Assurance Plan differs from the 2019–20 Plan in that it no longer provides targets for the level of compliance, and it combines both recommended improvements and scheduled activities into one section.

2.47 The assurance activities that were undertaken in accordance with the 2019–20 and 2020–21 Assurance Plans are set out in Table 2.3 below.

Table 2.3: Wage subsidies assurance activities

|

Activities |

Action taken at June 2021 |

|

2019–20 |

|

|

Rolling Random Sample Cycles 14, 15 and 16. |

Wage subsidies were included in Cycles 14, 15 and 16 of the Rolling Random Sample (discussed further from paragraph 2.57). |

|

Broader sample of kickstart payments made to employers after employment terminated. |

The kickstart Targeted Assurance Activity was finalised in February 2021 and found that from the sample of 410 payments, 94 per cent were not valid due to providers making the payment after the participant had left employment, with a total of $1,179,516 to be recovered. DESE advised that the debts were recovered through future payment offsets. |

|

Quality Assurance Framework results. |

The Wage Subsidies — Quality Assurance Framework (QAF) Analysis report contains analysis from the Round 2 QAF audits conducted between September 2017 and May 2018 and was provided to the Wage Subsidies Team to contribute to the assurance activity in the 2019–20 plan. Additional analysis was conducted of 42 providers against the two relevant areasa of the Quality Assurance Framework. The audit found that provider compliance was high overall, with three non-conformances and nine opportunities for improvement. |

|

Analyse identified labour hire company’s use of Wage Subsidies and ongoing employment. |

This targeted assurance activity reviewed the use of wage subsidies by labour hire companies’, testing if the payment and placement integrity of a sample of 342 wage subsidy agreements. The activity was finalised in April 2020 and found that around 90 per cent satisfied or mostly satisfied requirements, five per cent partially met requirements, and five per cent did not meet requirements. |

|

Consider refinements to the data analytics application to ensure capturing correct data. |

In March 2020, DESE undertook refinements to the data analytics application for wage subsidies risk alerts and risk indicators. |

|

Risk Plan update and consultation on risks relating to new employment services trial and its impact on Wage Subsidies. |

The Incentives and Investments Branch Risk Plan was updated in 2020–21 and risks associated with the New Employment Services Trial are covered in the plan. |

|

Analysing Wage Subsidy Agreements with possible pre-existing employment. |

This assurance activity was not undertaken. However, previous employment with an employer was one of the risks included in the data analytics application enhancements undertaken in March 2020. |

|

Data analysis to examine Return to Services following conclusion of a wage subsidy. |

As above. |

|

DES Restart Wage Subsidies targeted assurance activity. |

This assurance activity (finalised in August 2019) assessed 197 Restart wage subsidy payments against the guideline requirements and found 92 per cent of those payments satisfied or mostly satisfied requirements. The remaining eight per cent of payments, with a total value of $40,692, were not compliant with Guideline requirements. |

|

2020–21 |

|

|

COVID-19 Payment Integrity Assurance Activity. |

The purpose of this assurance activity was to provide oversight of the payment integrity and compliance activity across employment programs during national COVID-19 restrictions from 20 March to 31 July 2020. The results were being still being finalised as at September 2021. |

|

Rolling Random Sample Cycles. |

Wage subsidies were included in Cycle 17 of the Rolling Random Sample. |

|

Wage Subsidies and concurrent funding Assurance Activity. |

The Wage Subsidies Team undertook assurance activities in conjunction with the DESE Skills and Training Group and the Australian Taxation Office, data matching with concurrent claims against apprenticeship wage subsidies and the Job Maker Hiring Credit respectively. |

|

Consider the establishment of a monitoring activity schedule for the Wage Subsidies Risk Monitoring Application. |

To be reconsidered in the 2021–22 wage subsidy assurance plan. |

Note a: The two areas of the Quality Assurance Framework which have direct relevance to wage subsidies are: providers have various strategies in place to promote a wide range of employment opportunities; and claims processes used by providers are systematic and align with the guidelines.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Risk planning and management

2.48 DESE’s Risk Management Framework and Policy, last updated in 2020, consists of two parts: the Risk Management Framework and the Risk Management Policy.

2.49 The Framework describes DESE’s approach to risk management, types of risks, roles and responsibilities relating to risk management, the elements which comprise the Framework, risk reporting, review requirements and lists the performance indicators relevant to evaluating the effectiveness of the Framework.

2.50 The Risk Management Policy sets out DESE’s Risk Management Process and provides the risk matrix, risk appetite and tolerance; a mandate that Risk Management Plans be approved annually and reviewed semi-annually at the division level; and discusses shared risk. It also discusses a number of specific risks such as staff fatigue, climate risk, and foreign influence and foreign interference.

2.51 The Risk Management Guidelines, a corporate document dating from 2020, provides non-binding guidance on the application of the Risk Management Framework and Policy. It defines risk and risk management and the elements of DESE’s Risk Management Process: establishing context; identifying risks; analysing risks; evaluating risks; and treating risks.

Incentives and Investments Branch Risk Plan

2.52 Wage subsidy-related risks are included in the Incentives and Investments Branch Risk Plan (updated in 2020) and in the Employment Services Payment Integrity Risk Plan (updated 2021).

2.53 The Incentives and Investments Branch risk plan identifies 11 risk events, six of which are relevant to wage subsidies:

- programs are not delivered in accordance with guidelines;

- budget allocation is exceeded and/or budget is not managed in an ethical, effective or efficient wage;

- fraudulent use of Commonwealth resources under programs managed by the Branch;

- personal information is not handled in accordance with the Privacy Act 1988 or the Australian Privacy Principles;

- procurement activities (including contracts, consultancies and any expenditure of Commonwealth monies) are inadequate to meet desired outcomes; and

- development of new policy proposal does not meet the standards outlined in the Department of Finance requirements/or is not successful.

Payment Integrity Risk Plan

2.54 The Payment Integrity Risk Plan, administered by DESE’s Assurance Coordination Branch, outlines risks relating to payments made under DESE’s employment services programs and sets out the associated risk treatments.

2.55 There is one risk related to wage subsidies in the Payment Integrity Risk Plan: ‘Risk R00740 – Entity incorrectly or inappropriately claims payments – Wage Subsidies’, which has a risk rating of ‘medium’. The Plan identifies 11 possible causes for the risk event and five treatments. The treatments include assurance activities such as the RRS, use of data analytics, targeted assurance and administrative reviews (discussed further from paragraph 2.56 below).

Assurance and compliance activities

2.56 Under the assurance plan, DESE conducts assurance and compliance activities to ensure that the administration of wage subsidies by employment services providers is compliant with the program requirements. The 2019–20 Wage Subsidies Assurance Workbook identifies the following assurance activities for wage subsidies:

- the RRS;

- data monitoring;

- targeted assurance activities;

- Employment Services Risk Alerts and detailed/administrative reviews; and

- Employment Services Tip-Off Line, complaints and Ombudsman inquiries.

Rolling Random Sample (RRS)

2.57 The RRS is an assurance activity for payments made as part of DESE’s employment programs, including wage subsidy payments. The RRS is a post-payment check where the accuracy of payment processing and the adequacy of documentary evidence supplied by providers are examined.

2.58 The RRS is conducted three times (or ‘cycles’) each year – September to March; March to June; and July to September. Cycles are conducted over two weeks by assessors drawn from staff from DESE’s national office and state and territory offices.

2.59 Assessors assure wage subsidy payments through the RRS by assessing a sample of provider claims for the reimbursement of wage subsidy payments and examining documentary evidence for each sampled claim to assess whether it meets program requirements. A sub-sample of assessments is then quality assured by separate quality assurance assessors.

RRS sampling methodology

2.60 DESE provided the ANAO with a document that was prepared for the audit describing the RRS sampling methodology. DESE advised that it uses a stratified random sampling methodology and aims to sample enough claims through the RRS to estimate the level of compliance to an accuracy of ±10 per cent with 95 per cent confidence level, and the sample size is calculated using a standard formula for random sampling.20 However, DESE was unable to provide evidence that the RRS methodology was documented or endorsed. DESE further advised that the internal reporting to governance groups and management on the RSS results was incorrect in respect to the value of claims related to the payments examined, and the subsequent amount identified for recovery. This was due to the sampling methodology and reporting approach applied, and that some values were extracted from an incorrect source. DESE intended to correct the reporting from Cycle 18, including updating prior cycle results.

2.61 Considering that clearly describing the method of measurement and assessment of compliance increases the transparency and confidence in the robustness of assurance activities, DESE should document and seek endorsement of the methodology for the RRS. The ANAO’s performance audit of Jobactive — integrity of payments to employment service providers further examines whether DESE has effectively implemented its framework to manage and monitor payments to employment service providers.

2.62 Nevertheless, DESE’s methodology has been periodically informed by statistical methodology advice from an actuarial firm. For example, DESE sought actuarial advice for Cycle 16 of the RRS in 2019–20, because the period covered by the cycle was interrupted by COVID-19 and DESE had to vary its methodology. The sample for Cycle 16 was expanded to include claims between September 2019 and September 2020, excluding the period of 20 March 2020 to 31 July 2020. A payment integrity assurance activity covering the COVID-19 period between March and July 2020 was conducted in Cycle 17, with the sample size also based on advice from an actuarial firm.

RRS assessment and quality assurance process

2.63 RRS wage subsidy assessors use a workbook in Microsoft Excel to assess provider claims for the reimbursement of wage subsidy payments. The workbook is populated with the details of a wage subsidy placement, which are then checked against information and evidence provided by employers through the jobactive website and by providers in ESSWeb. Evidence reviewed includes wage subsidy head agreements, evidence of wages paid and hours worked (such as payslips), and evidence of the payment of a wage subsidy to the employer. If an assessor requires additional evidence to complete the assessment, DESE will email the provider to ask that the additional evidence be uploaded within one day.

2.64 DESE advised that the outcome of an assessment is calculated automatically by a formula in the workbook and depends on which deficiencies, if any, have been identified. The outcomes of all finalised assessments are automatically uploaded into the Wage Subsidies Risk Management (WSRM) application, discussed further from paragraph 2.71.

RRS outcomes and recoveries

2.65 Table 2.4 sets out the assessment outcomes for wage subsidy claims sampled by the RRS since July 2017. In each cycle, requirements were assessed to have been fully or mostly satisfied for around 90 per cent of payments. While there is no compliance target for wage subsidies, DESE advised that the overall compliance target for the RRS was 95 per cent.21

Table 2.4: Assessment outcomes for wage subsidy claims 2017–2020

|

|

|

|

Outcomea |

|||

|

RRS cycle |

Agreements reviewed |

Value of wage subsidy claims sampled |

Satisfied (% of total) |

Mostly satisfied (% of total) |

Partially met (% of total) |

Not met (% of total) |

|

Cycle 9 (July to September 2017) |

200 |

$1,458,106 |

190 (95) |

10 (5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Cycle 10 (September 2017 to March 2018) |

501 |

$3,181,272 |

430 (86) |

4 (1) |

45 (9) |

22 (4) |

|

Cycle 11 (April to June 2018) |

503 |

$3,569,549 |

464 (92) |

4 (1) |

18 (4) |

17 (3) |

|

Cycle 12 (July to September 2018) |

370 |

$2,498,326 |

325 (88) |

10 (3) |

19 (5) |

16 (4) |

|

Cycle 13 (September 2018 to March 2019) |

281 |

$1,901,506 |

260 (93) |

0 (0) |

12 (4) |

9 (3) |

|

Cycle 14 (March to June 2019) |

207b |

$1,417,935 |

194 (93) |

1 (0) |

7 (3) |

6 (3) |

|

Cycle 15 (July to September 2019) |

261 |

$1,860,195 |

236 (90) |

1 (0) |

6 (2) |

18 (7) |

|

Cycle 16 (September 2019 to September 2020)a |

375 |

$2,601,591 |

328 (87) |

3 (1) |

19 (5) |

25 (7) |

|

Cycle 17 (September 2020 to March 2021)c |

316 |

$2,089,912 |

283 (89) |

0 (0) |

14 (4) |

19 (6) |

Note a: Total outcome percentages do not all equal 100 due to rounding.

Note b: The difference between the total outcome count (208) and the total number of agreements examined (207) is due to DESE’s incorrect reporting, as discussed at paragraph 2.60.

Note c: The period from March to July 2020, which was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, was included in Cycle 17.

Source: DESE RRS results, Cycles 9–17.

2.66 Table 2.5 below sets out the total recoveries made as a result of the RRS as advised by DESE. Total recoveries average around one and a half per cent of the total claim amount assessed over the nine cycles. Recoveries are lower than the percentage of claims which were found in the RSS to have partially met or did not meet requirements (as set out in Table 2.4), as some RRS findings do not result in a recovery or can result in a partial recovery. For example, a finding that the amount paid to the employer is less than what the employer was eligible for, or a wage subsidy head agreement was provided but was not signed by the provider, do not result in recoveries. Where a finding is that the amount claimed is greater than the amount paid to the employer, this will result in a recovery.

Table 2.5: Wage subsidy financial recoveries from the RRS

|

RRS Cycle |

Agreements Reviewed |

Claims Reviewed |

Total Claim Amount |

Total recoveries

|

Per cent recovered of total claim amount (%) |

|

Cycle 9 (July to September 2017) |

200 |

428 |

$1,458,106 |

$4,714 |

0.3 |

|

Cycle 10 (September 2017 to March 2018) |

501 |

971 |

$3,181,272 |

$29,872 |

0.9 |

|

Cycle 11 (April to June 2018) |

503 |

1,045 |

$3,569,549 |

$37,645 |

1.1 |

|

Cycle 12 (July to September 2018) |

370 |

780 |

$2,498,326 |

$32,448 |

1.3 |

|

Cycle 13 (September 2018 to March 2019) |

281 |

571 |

$1,901,506 |

$23,681 |

1.2 |

|

Cycle 14 (March to June 2019) |

207 |

419 |

$1,417,935 |

$14,545 |

1.0 |

|

Cycle 15 (July to September 2019) |

261 |

536 |

$1,860,195 |

$42,121 |

2.3 |

|

Cycle 16 (September 2019 to September 2020)a |

375 |

697 |

$2,601,591 |

$49,320 |

1.9 |

|

Cycle 17 (September 2020 to March 2021)a |

316 |

591 |

$2,089,912 |

$44,125 |

2.1 |

|

Total |

3,014 |

6,038 |

$20,578,392 |

$278,471 |

1.4 |

Note a: The period from March to July 2020, which was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, was included in Cycle 17.

Source: DESE RRS results cycles 9–17.

2.67 Table 2.5 shows that the wage subsidy recoveries increased in Cycle 15. DESE advised this occurred due to the introduction of TtW and ParentsNext in the sampled wage subsidy claims that were assessed in this cycle for the first time. The assurance activity demonstrated that these employment program providers did not fully understand the requirements for administering wage subsidies under these programs. The higher non-compliance was mainly due to these providers claiming reimbursement from DESE before the employer was paid. DESE further advised that where providers made this error, the Cycle 15 results were used to educate providers on appropriate claiming practices for wage subsidies and no recoveries were actioned. DESE actioned recoveries for deficiencies associated with the incorrect calculation of the eligible wage subsidy payment or the supply of insufficient or inappropriate documentary evidence and this resulted in higher than usual recovery amounts for Cycle 15.

2.68 In addition to financial recoveries, DESE provides written feedback to providers with claims that were assessed as part of the RRS. The feedback sets out the overall results for wage subsidy claims assessed in the relevant RRS cycle, a list of the most common deficiencies, and learnings for providers. The level of compliance has not improved as a result of this activity. The RRS is also used to inform DESE’s approach to targeted assurance activities, although the assurance planning process seeks to anticipate risks before they arise and are detected by the RRS.

Quality assurance of RRS cycles

2.69 DESE quality assures RRS assessments by re-performing a sample of five per cent of randomly selected assessments. In addition, all assessments that identify a deficiency are quality assured and assessments performed by new assessors are targeted for additional quality assurance.

Table 2.6: Quality assurance of the wage subsidy payments in the RRS

|

RRS cycle |

QA completed — no change |

QA updated — result sustained |

QA updated — result amended |

Per cent amended (%) |

Total |

|

Cycle 9 (July to September 2017) |

81 |

133 |

67 |

23.8 |

281 |

|

Cycle 10 (September 2017 to March 2018) |

281 |

8 |

69 |

19.3 |

358 |

|

Cycle 11 (April to June 2018) |

95 |

107 |

37 |

15.5 |

239 |

|

Cycle 12 (July to September 2018) |

46 |

81 |

22 |

14.8 |

149 |

|

Cycle 13 (September 2018 to March 2019) |

52 |

53 |

14 |

11.8 |

119 |

|

Cycle 14 (March to June 2019) |

23 |

41 |

3 |

4.5 |

67 |

|

Cycle 15 (July to September 2019) |

80 |

50 |

13 |

9.1 |

143 |

|

Cycle 16 (September 2019 to September 2020) |

58 |

26 |

18 |

17.6 |

102 |

|

Cycle 17 (September 2020 to March 2021) |

47 |

20 |

11 |

14.1 |

78 |

Note: ‘No change’ means the original assessment was upheld, ‘result sustained’ means the original assessment was upheld but the QA assessor may have made minor corrections that did not change the original assessment outcome, and ‘result amended’ means the original assessment was modified as a result of the QA.

Source: DESE RRS quality assurance results.

2.70 Table 2.6 sets out the quality assurance results for cycles nine to 17 as advised by DESE. The percentage of results amended ranges over the cycles from 4.5 to 23.8 per cent of all quality assurance wage subsidy cases completed.

2.71 Quality assurance results are used to inform feedback to assessors and are tracked through the WSRM application (discussed below). DESE also advised that RRS assessors, including quality assurance assessors, meet daily during the cycle to discuss any issues arising out of quality assurance that need to be addressed by assessors.

Data monitoring

2.72 DESE uses a business intelligence and data analytics tool which brings together data from a range of sources across DESE. The dedicated WSRM application displays a monthly updated dashboard of wage subsidies-related risk indicators.

2.73 The WSRM application provides a centralised snapshot of the total number of wage subsidy agreements that have been risk-flagged, and the number of agreements and employers or providers associated with each risk. The app also identifies individual wage subsidy agreements that have been risk-flagged. Users can explore the characteristics of risk-flagged agreements and the associated employers, providers and participants.

2.74 In 2019, an internal audit reviewed the wage subsidies data analytics by examining wage subsidies risk management plans, assessing if the WSRM application supports the identification and analysis of wage subsidies risks, and verifying the accuracy of WSRM application reporting. Prior to the internal audit, DESE monitored 17 risk indicators and 19 sub-indicators. The internal audit tested a subset of the indicators representing 13 risk indicators and 13 sub-indicators and found that one indicator and seven sub-indicators were unsatisfactory, and that three indicators and two sub-indicators required improvement, and should be reviewed by the wage subsidies team. The three internal audit recommendations were addressed in April 2020 and closed in May 2020.

2.75 In May 2020 DESE made the following additional changes to the WSRM application:

- the application was ‘redefined into three discrete sections’: risk alerts which might need to be immediately reviewed and actioned22, risk indicators to be used for ‘broader program management’, and contextual information which DESE assessed to provide useful information about program operations but did not in themselves indicate any actual risk;

- one indicator was maintained;

- two sub-indicators became indicators;

- two indicators and two sub-indicators relating to kickstart were removed due to the cessation of kickstart;

- two indicators and four sub-indicators were removed because DESE advised there was no evidence those risks were occurring.

- one indicator and five sub-indicators were reclassified as risk alerts; and

- three indicators and six sub-indicators were reclassified as contextual indicators.23

2.76 DESE advised that the WSRM application is not used to proactively identify risks and is primarily a research tool that complements other assurance activities. DESE should clarify in the Wage Subsidies Assurance Workbook when it is next updated that the WSRM application is used as a research tool and is not a discrete assurance activity and therefore cannot be relied upon as such in program assurance.

Targeted assurance activities

2.77 Targeted assurance activities are identified in DESE’s Assurance Planning Workbook for wage subsidies and involve detailed investigation of identified or suspected non-compliance. Remedial actions resulting from a targeted assurance activity may include provider feedback, restricting the number of wage subsidies an employer can access and the recovery of reimbursements via an offset against a provider’s future payments.