Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Upgrade of the Orion Maritime Patrol Aircraft Fleet

The audit objective was to examine the adequacy of Defence's and DMO's management of the nearly completed elements of Project Air 5276. The ANAO identified a number of causes for time delays and cost escalation in those elements. Those causes are outlined in the overall audit conclusions, to assist in the achievement of improvements in future planning and management of capital equipment acquisitions.

Summary

Background

1. Australia's Air Force operates 19 Orion maritime patrol aircraft, which entered service in 1978 and 1984–1986. The refurbishment of the Orion fleet was approved in late 1992 with a contract signed in January 1995. Project Air 5276 is a multiphased project aimed at upgrading the aircraft's combat systems to ensure its military effectiveness, and extending the aircraft's life through to its planned withdrawal from service in 2015.

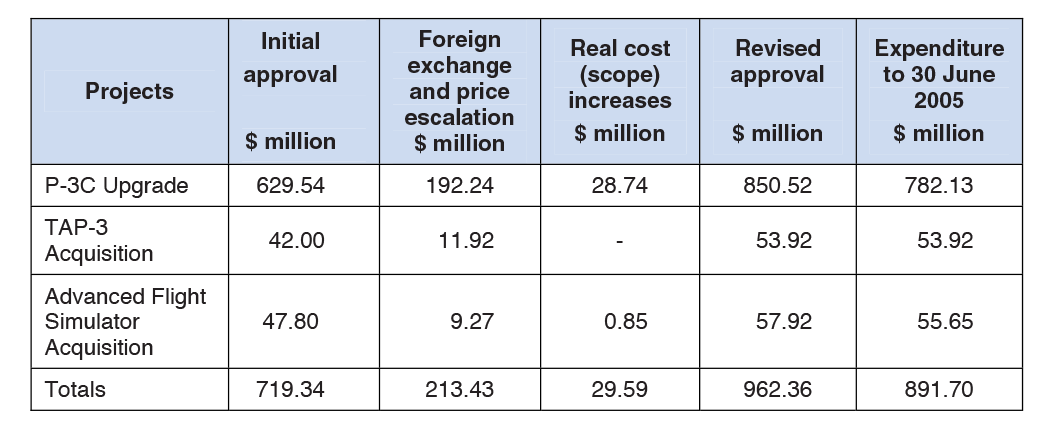

2. The major elements of Project Air 5276 nearing project completion in 2004–2005 (see Table 1) included:1

- an Upgrade Project for 18 2 aircraft (from the P-3C to the AP-3C configuration), including the acquisition of associated support;

- the purchase, under the United States (US) Foreign Military Sales (FMS)3 system, of three second-hand Orion aircraft and their modification to a training and utility (that is, passenger and cargo transport) aircraft (designated TAP-3 – Training Australian P-3) and acquisition of a fourth aircraft to become a source of spare parts; and

- the contract for an acquisition of an Advanced Flight Simulator (AFS) was signed in July 1998.

Table 1: Major Orion upgrade and life extension projects

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

3. Subsequent elements of Project Air 5276 provide for electronic warfare self-protection measures and the upgrade or replacement of the aircraft's Infra-red Detection System; the communications suite and data links; Electronic Support Measures; and other systems4 that may become obsolete during the remaining in-service life of the aircraft. These Project elements are estimated to cost in excess of $550 million.

4. The performance objectives of the main element of Project 5276, the P-3C Upgrade Project, were to:

- contribute to the life extension to 2015 of the aircraft fleet, largely through a significant reduction in the weight of the operational aircraft;

- shift the centre of gravity of the aircraft forward (for greater operational safety and flexibility); and

- enhance the aircraft's military capabilities.

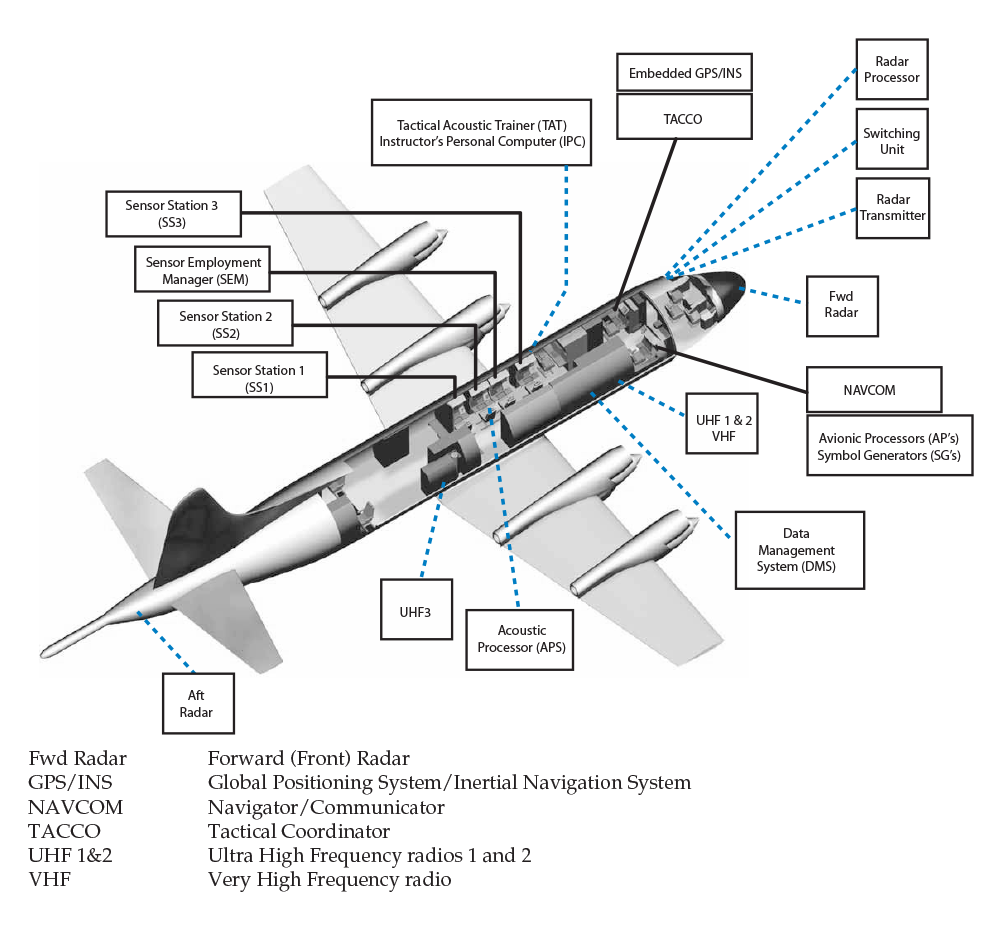

5. The Upgrade Project replaced five major sub-systems on the aircraft, namely the radar, acoustics, navigation, communications, and data management system (DMS – the aircraft's central computer). The Upgrade Project also included the acquisition of operational support systems, comprising an Operational Mission Simulator (OMS) for the training of operational crews, a Systems Engineering Laboratory (for software maintenance and development, technical research and modification development) and a Mission Replay and Analysis Module (for pre- and post-flight mission support).

6. Figure 1 shows the subsystems which have been replaced in the Upgrade Project. The major activity in the Project was to develop, modify and reuse software, involving more than three million source lines of code. This activity posed the greatest technical, schedule and cost risks to the Project.

Figure 1: Subsystems replaced in the Orion Upgrade Project

Source: Department of Defence.

7. To provide on-site technical support for the Upgrade Project, some 140 Australian industry personnel were required at 13 Contractor and subcontractor sites. This included over 60 positions in three overseas countries.

Audit approach

8. This audit was undertaken towards the conclusion of the major approved elements of Project Air 5276, when more than 90 per cent of estimated project costs were expended. The elements of the Project examined in the audit were initiated in the early 1990s, predating the recent reforms in the Defence capability development and acquisition framework. These reforms led to the 'two pass' capital equipment definition, analysis and approval process outlined in the 2005 Defence Capability Development Manual. 5

9. The audit objective was to examine the adequacy of Defence's and DMO's management of the nearly completed elements of Project Air 5276. The ANAO identified a number of causes for time delays and cost escalation in those elements. Those causes are outlined in the overall audit conclusions, to assist in the achievement of improvements in future planning and management of capital equipment acquisitions.

Overall audit conclusions

10. The Orion Upgrade Project met its performance objectives. The modified aircraft have achieved, and in a number of roles exceeded, the expected operational performance. The capability enhancements allow the aircraft to cover a given surveillance area in greater detail and in a third less time.

11. The ANAO found that the long delays in the Project (some four years in the delivery of the upgraded aircraft) meant that equipment met contractual requirements but some equipment was already obsolete at the time of installation in the aircraft. Defence, the Contractor and subcontractors underestimated the unique features of the design and production work to be undertaken, and the complications involved in integrating a range of different new systems, both with each other and with the retained aircraft systems. These complexities were made more difficult to manage in the absence of a fully developed software testing facility, which had been a pivotal part in the Project's planning. Nevertheless, the Upgrade Project has met its performance objectives and the upgraded aircraft have played a significant part in Australian border protection and coalition 6 operations.

12. In the purchase and modification of three second-hand Orion (TAP-3) aircraft, the ANAO found that, in Defence's decision making on the method of procurement, insufficient attention was paid to the financial and technical constraints in contractual commitments under the US Foreign Military Sales system. These constraints were insufficiently considered as an integral part of a comprehensive sourcing analysis before Defence decided on a method of procurement. The delays in the delivery of refurbished aircraft ranged from 9 to 25 months.

13. The acquisition of the Advanced Flight Simulator highlights the importance of having at hand appropriately skilled personnel to ensure that projects can be started and progressed in a timely manner. Against planned timelines, the delivery of an essential training capability was over two years late, and the tactical training capability was three years late. The ANAO found that the current inability to use the AFS for a number of high risk and high airframe fatigue-inducing training sequences means that the AP-3C Orions have to be used for that training, resulting in higher risks and costs, including the consumption of airframe fatigue life. The Air Force expects to be able to keep the Orions operating until their planned withdrawal from service, and Defence is undertaking further work with the Contractor to increase the AFS's capabilities.

Key findings

Upgrade of the Orions (Chapter 2)

14. The ANAO found that the 18 modified aircraft have met all of the Project's performance objectives. The Air Force element operating the aircraft, No. 92 Wing based at Edinburgh, South Australia, has substantially met its military preparedness requirements. The capabilities of the upgraded Orion aircraft have played a significant part in Australian border protection and coalition operations.

15. The main delays of several years against the planned timetable occurred in the acceptance of the prototype aircraft, the aircraft design, and the Systems Engineering Laboratory. Defence, the Contractor and subcontractors underestimated the unique features and complexity of the design and production work required, particularly the complications involved in integrating different new systems, both with each other and with the retained aircraft systems.

16. Deliveries of the upgraded Orion aircraft were some four years late. Acceptance of the first aircraft was 51 months behind the contracted schedule. Delivery and acceptance of upgraded aircraft accelerated after Air Force's acceptance into service of the first aircraft in July 2002. By September 2003, the 10th aircraft was accepted, and in December 2004, the final (18th) aircraft was accepted.

17. All but one of the last twelve aircraft were completed in about 230 days compared to an average of 610 days for the first four aircraft produced at the Contractor's Australian production site. The delays in delivery were primarily due to:

- inability to fully test interactions of modified equipment and software before installation on the aircraft because of a lack of complete simulation fidelity;

- greater than expected software development effort, and integration problems related to the DMS;

- difficulties arising in contractor/subcontractor relationships;

- underestimation of the extent of integration effort required of the Contractor;

- technical difficulties related to radar performance in some conditions; and

- engineering changes for equipment such as satellite communications, on-line Harpoon missiles and a structural data recorder. They were to meet requirements external to the Project Office and added to project scope, cost and schedule.

18. The protracted delays in delivery of the modified Orion aircraft have meant that Air Force had to operate fewer, and less capable, operational aircraft during the period of delivery delays. Furthermore, the delays resulted in some subsystems on the aircraft becoming obsolete before their installation in the aircraft. High cost items at risk of obsolescence in the future include the DMS, radar, and the OMS. 7

19. The Contract for the Upgrade of the Orions placed the performance risk on the Contractor. However, there were no specific penalties for delays. As a result, protection for Defence against delivery delays was limited. When Defence's persuasive efforts to minimise delays in deliveries failed, the provisions of the Contract largely restricted Defence's ability to exert pressure to delaying payments to the Contractor until relevant milestones were met. Nevertheless, Defence was able to conclude a Deed of Settlement with the Contractor, to receive goods and services in kind to the value of $5 million.

20. To monitor and control risks to safety, fitness for service and environmental compliance, Defence has put in place a technical regulatory framework as the basis for managing technical integrity in the acquisition and maintenance of equipment. The ANAO found that in the Orion Upgrade, the Project Office developed a series of plans and procedures that helped ensure that the requirements of the Defence technical regulatory framework were met.

Acquisition and Refurbishment of Second-hand aircraft (Chapter 3)

21. Project Air 5276 included the acquisition of three Orion training aircraft, designated as TAP-3s. Their main purpose (primary mission) was to reduce the training burden from the main Orion fleet, thus extending the service life of that fleet. The three TAP-3's only achieved about 300 dedicated flying training hours a year against a target of more than 1,200 hours. Also, the full fleet of three aircraft was only used from February 1999 to November 2003.

22. Air Force mainly flew the TAP-3s as utility aircraft. In carrying out that role, the aircraft helped to ensure that No. 92 Wing's Orion pilots maintained flying currency on the aircraft. There are no cost comparisons available to determine whether the use of the TAP-3s for the utility aircraft role was cost-effective. Defence considers that the availability of the TAP-3 aircraft provided operational flexibility which was significant but difficult to cost.

23. During their in-service period, the TAP-3 aircraft usually flew about 1 050 hours a year (750 hours in the transport role, 300 hours on pilot and crew training). On transport (including logistic resupply and repair) flights, the TAP-3 aircraft provided a considerable amount of continuation flying training 8 to the Orion pilots. This was flying training that would not have been available at the time because of low numbers of available P-3C aircraft and the low fidelity of the flight simulator in service at the time. Defence considers that without the TAP-3 flights, No. 92 Wing would not have been able to maintain currency of all of its assigned pilots, and that the TAP-3 aircraft were valuable by providing options for additional operational tasking on a day to day basis, particularly when the C-130 transport fleet was very busy.

24. Defence chose the FMS route for this element of the Project because FMS was considered to offer advantages on cost, schedule and risk. From contract signature (February 1994) to completion of this element (December 1998), contract costs rose from $US 31 million to $US 37.79 million, and total costs of the TAP-3 acquisition from an estimate of $A 42 million to $A 53.92 million. 9

25. Delays in the delivery of the three refurbished TAP-3 aircraft were 9, 19 and 25 months, respectively. This schedule slippage was estimated by Air Force to cost about $US 5 200 per working day in project management and engineering overheads. Cost escalation and delivery delays were due in part to an underestimation of the cost and delivery time implications of the differences in Air Force's servicing requirements and standards compared to US Navy aircraft servicing practices at the time. There was inadequate consideration by Defence of the implications of signing a ‘cost-plus' agreement, which provided less than full visibility and auditability on some technical and financial aspects.

26. The ANAO found that the main factors contributing to the problems experienced in the acquisition of the second-hand Orion aircraft included:

- worse than expected condition of the aircraft purchased;

- FMS cost recoupment policy;

- limitations on Air Force's ability to ensure that the charges made in the FMS case were correct;

- US Navy servicing work not meeting Air Force's technical standards and limitations on Air Force's ability to ensure that these standards were achieved; and

- Defence and US Navy failed to recognise the unique features of the Australian requirements for modification and servicing and the associated cost implications.

Acquisition of the Advanced Flight Simulator (Chapter 4)

27. Due to difficulties in finding staff with the relevant skills for the Flight Simulator Project Office, preparation of the Request for Tender (RFT) slipped from the planned release of July 1996 to May 1997. Defence's RFT documentation requested that tenderers for the AFS meet a 22 months delivery schedule. That is just four months more than the typical timeline for a commercial (production line) simulator which does not require extensive development and flight data collection work.

28. In an attempt to shorten the delivery time for the simulator, Defence assumed responsibility for the provision of flight data to the simulator manufacturer. Air Force undertook flying to collect the flight data, in conjunction with data collection for a separate program to collect fatigue test data. The instrumentation for the fatigue test data collection corrupted the flight data collected for the simulator. Defence agreed to pay the simulator manufacturer $1.04 million for the extra work required to be done as a consequence of the faulty flight data, and extended, by 10 months, the delivery schedule for the AFS to provide an essential training capability.

29. The delivery of a more advanced, tactical training capability by the AFS was three years late. Defence applied liquidated damages for late delivery, as provided in the contract. The amount of $1.15 million was offset against moneys owed by Defence to the Contractor for the achievement of milestones in the Project.

Lessons learnt

30. The major lessons learnt from the Orion life extension and upgrade Projects include:

- In the P-3C Upgrade Project, the Contract provided limited protection for Defence against delivery delays. When Defence's persuasive efforts to minimise delays failed, Defence's ability to exert pressure was largely restricted to delaying payments to the Contractor until milestones were met. In future acquisitions, contractors should be given greater incentives to adhere to schedules, and cogent penalties for delivery delays.

- Defence and contractors underestimated the unique features of the design and production work to be undertaken, and the complications involved in integrating a range of different new systems, both with each other and with the systems retained on the aircraft. These complexities were made more difficult to manage in the absence of a fully developed software testing facility, which had been a pivotal part in the Project's planning. The recent reforms in Defence capability development and acquisition provide revised processes which are aimed to produce more detailed and accurate data on cost, schedule and capability than was provided in previous Defence processes.

- Greater awareness of the risks involved in acquiring second-hand equipment under the FMS route, and of the need to fully establish the condition of the equipment, would have highlighted the requirement for a more thorough investigation of alternative acquisition options to mitigate those risks.

- The delays in the delivery of the aircraft simulator due to skills shortages, and the risks incurred to try to make up for those delays, highlight the importance of having at hand appropriately skilled personnel to ensure that projects can be started and progressed in a timely manner.

- Taking into account its experience with the AP-3C simulator, Defence, in the ‘Wedgetail' Early Warning and Control Aircraft Project, which has an approved cost of $3.46 billion, placed full responsibility on the Contractor for the flight trainer to meet simulator fidelity requirements.

Agency response

31. The Department of Defence provided a response on behalf of DMO and Defence. An extract from the response stated that:

The report acknowledges the important fact that the subject project was initiated in the early 1990s when a different acquisition process existed. Project Air 5276 2A, 2B and 3 were developed collectively, but separately, and managed under different directorates and by different project offices.

Since that time, including through the use of lessons learnt from these project phases, Defence has significantly improved its capability development, procurement, and project management processes and skills. Throughout the Air 5276 Phase 2 and 3 life-cycles, which are not yet complete, Defence believes contemporary best practice of the time was employed and capability value for money was maximised. While some capability and support outcomes are still being addressed, the overall capability outcomes from this series of complex integration project phases have showcased the ADF AP-3C weapon system as one of the most capable maritime patrol and response capabilities in the world.

32. The Defence response also agreed to the lessons learnt. It noted that the merits of penalties for contractor delays have to be weighed against the schedule risk premium which a contractor could be expected to add when bidding. The full Defence response is at Appendix 1 of the Report.

Footnotes

1 Phase 1 of the Project was a Project Definition Study.

2 One of the 19 aircraft is used for development purposes and was not included in the Upgrade Project.

3 A Letter of Offer and Acceptance for $US 30.93 million was signed in February 1994. The FMS is a major component of the activities under the US Government Security Assistance Program authorised by the US Foreign Assistance Act and the Arms Export Control Act.

4 These include the radar, operational mission simulator, the acoustics and data management.

5 The ‘two pass' process aims to generate significantly more detailed and accurate data on cost, schedule and capability issues than had occurred in previous Defence capability development processes. See chapter 1, paras. 1.9-11.

6 AP-3C aircraft participated in international military operations in the Middle East Area of Operations.

7 Defence's Project Air 5276 Phase 9 addresses AP-3C obsolescence issues relating to the radar, the OMS, the acoustics and the DMS.

8 Continuation training refers to the number of flying hours required by pilots to maintain currency on an aircraft type, over a period of time.

9 Net exchange rate gains amounted to $1.55 million, and price increases to $13.47 million.

10 Standard financial terms and conditions for FMS are set by the US Government. They are outlined in para. 3.19.