Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Trade Measurement Compliance Activities

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Trade measurement is an area of Australian Government administration that directly impacts on everyday life.

- The audit is part of the ANAO’s coverage of regulatory activities.

- The National Measurement Institute, a division within the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) with more than 350 staff, is responsible for trade measurement compliance.

Key facts

- Australia’s trade measurement transactions are estimated to be worth more than $750 billion each year.

- Trade measurement compliance activities include conducting trader audits, testing measuring instruments, and conducting enforcement activities where non-compliance is identified (such as issuing warning letters or infringement notices).

What did we find?

- DISR’s administration of trade measurement compliance is partly effective.

- Sound governance arrangements were not fully in place to support trade measurement compliance activities. The approach is not adequately risk-based.

- The department’s approach to trade measurement compliance has been partly effective. Compliance monitoring approaches are appropriate. The level of compliance monitoring activity has fallen. Action in response to non-compliance has not been timely or demonstrably effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were six recommendations to DISR aimed at strengthening its governance arrangements and improving its approach to compliance activities.

- The department agreed to five recommendations and partially agreed to one.

3131

trader audits conducted in 2021–22.

29%

of 2021–22 trader audits identified non-compliance.

56

warning letters or infringement notices issued in 2021–22.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Trade measurement refers to all transactions in which the price of the commodities or goods is based on measurement of quantity or quality. The primary purpose of Australia’s trade measurement system is to ensure that the pricing of traded goods is based on accurate measurement. Trade measurement covers both business-to-business transactions and business-to-consumer transactions. Australia’s trade measurement transactions are estimated to be worth more than $750 billion each year.

2. The Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR), through the National Measurement Institute (NMI), administers Australia’s trade measurement laws. It is responsible for ensuring that businesses and individuals comply with the rules and regulations so that there is accurate and reliable measurement in trade. As part of this responsibility, DISR, through its NMI function, undertakes trade measurement compliance activities that include:

- conducting trader audits;

- testing measuring instruments in use for trade;

- testing pre-packaged goods;

- monitoring trading practices through trial purchases; and

- conducting enforcement activities where non-compliance has been identified.

3. DISR reported that in 2021–22 the NMI had:

- conducted 3131 trader audits (compared to 7600 in 2019–20 and 4842 in 2020–21);

- tested 7118 measuring instruments (compared to 13,588 in 2019–20 and 14,049 in 2020–21); and

- inspected 17,360 lines of packaged goods (compared to 78,290 in 2019–20 and 25,990 in 2020–21).

4. DISR reports the NMI as having more than 350 staff, of which 76 are estimated by DISR to work in trade measurement.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The activities of the department, through its NMI function of trade measurement, impact on everyday life. The department has regulatory responsibility to ensure that the pricing of traded goods, based on quantity or quality, is based on accurate measurement. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of DISR’s administration of trade measurement.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to examine whether compliance with trade measurement in Australia is being effectively administered.

7. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Have sound governance arrangements been established to support trade measurement compliance activities?

- Is there an effective approach to trade measurement compliance activities?

Conclusion

8. DISR’s administration of trade measurement compliance is partly effective.

9. Sound governance arrangements were not fully in place to support trade measurement compliance activities. A wide range of policy and procedural documents have been developed. However, there are gaps, overlaps and inconsistencies in those documents and they have not been updated in a timely manner. Evidence that appropriate appointment processes of officers under the relevant legislation are not consistently implemented exposes the department to a risk that actions taken in compliance activities are invalid. The annual targeting of compliance activities to particular industry sectors is not demonstrably risk-based, and the risk-based approach to selecting individual traders within targeted industries requires improvement.

10. The department’s approach to trade measurement compliance has been partly effective. The department has appropriate approaches to monitor the level of compliance, however the level of monitoring activity (particularly trader audits) has declined significantly over the last five years, with no evidence that this was driven by a changed risk environment or risk assessment. Nearly a third of all trader audits conducted between 2019–20 and 2021–22 identified non-compliance. Action in response to identified non-compliance, including follow-up audits and enforcement actions, has not been timely or demonstrably effective. DISR’s monitoring and reporting arrangements did not extend to the effectiveness of its regulatory approach, with its regulatory reporting more generally declining after 2019–20 such that it has not complied with its obligations.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

11. While DISR has many documents that cover a range of processes, there are gaps in the policies and procedures in place to support departmental officers in the administration of trade measurement compliance activities. Documents often overlapped and were not updated in a timely, consistent and transparent manner. Of the 60 officers that have undertaken trader audits in the period examined by the ANAO, 58 per cent had not been appointed in writing (as required by the National Measurement Act 1960) prior to undertaking their first audit, or there was no record of them having ever been appointed in writing. This impacted 1399 (eight per cent) of the 16,590 trader audits undertaken in the three-year period to 30 June 2022 examined by the ANAO. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.24)

12. The regulatory approach is not fully and appropriately informed by an assessment of compliance risk. DISR identified the need for a more sophisticated risk framework for legal metrology in December 2015. While progress has been made, trader audit activities are not yet being effectively and demonstrably targeted to market sectors and traders at higher risk of regulatory non-compliance. There is not a strong relationship between industry-level risk assessments and the department’s targeting of compliance activities and development of the annual National Compliance Plans. While DISR has introduced a risk-based approach for selecting individual traders for audit within those sectors being targeted, the approach should be improved. (See paragraphs 2.29 to 2.60)

Compliance activities

13. A key component of monitoring industry compliance is the conduct of trader audits, with DISR reporting that 32,792 audits were conducted over the five years to 2021–22. The department’s data overstates the number of trader audits it undertakes. There has been a downward trend in the number of trader audits planned to be conducted each year. The actual number of audits conducted has also fallen short of the target in each of the five years examined by the ANAO. In 2021–22, the department conducted 3131 audits which was less than half the target of 8000 audits which itself was significantly below the target of 11,500 audits for 2017–18. The department identifies in its National Compliance Plan particular industries to be targeted for compliance activity however the shortfall in performance against targets is as evident for the targeted programs as it is for the overall program of trader audits (59 per cent of planned audits under the targeted programs were not conducted in 2021–22).

14. There has been a similar declining trend across DISR’s other trade measurement inspection activities. There was a decrease of 52 per cent in the number of measuring instruments inspected between 2017–18 and 2021–22. There was a decrease of 76 per cent in the number of pre-packaged article lines inspected over the same period.

15. In comparison, the department has consistently exceeded the number of Tobacco Plain Packaging information visits undertaken by trade measurement inspectors on behalf of the Department of Health and Aged Care (the department receives separate funding from the Department of Health and Aged Care for this work). The evidence is that the department is prioritising this work it undertakes on behalf of another department over its own responsibility for trade measurement compliance. Further, the scope of this work has extended beyond the intended purpose of checking plain packaging to include examining whether traders are conducting illegal activities through the sale of illicit tobacco, with the related risks to the officers undertaking this work not adequately addressed by the department. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.32)

16. Action in response to identified non-compliance has not been timely or effective. Documented procedures are in place to respond to non-compliance via a follow-up trade measurement compliance audit or to commence enforcement action. Fewer follow-up audits are being undertaken and delays in the conduct of follow-up audits are common. Where follow-up audits have been undertaken the trend has been for increasing rates of continuing non-compliance to be found. Continuing non-compliance is not consistently followed by enforcement action. Where escalated enforcement action is being taken it is most often through warning letters and infringement notices (with associated fines) but those actions have also not been timely. (See paragraphs 3.33 to 3.51)

17. The regulatory approach is not being regularly reviewed and updated reflecting that the department is not complying with Australian Government requirements for regulatory performance reporting, including by not having in place an appropriate Regulator Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intent. DISR has not established performance indicators against which to review or to demonstrate the effectiveness of its regulatory approach to trade measurement. DISR reports its outputs, such as the number of trader audits conducted, although advice from the department to the ANAO as part of this audit indicates that the department is overstating the number of audits it undertakes. DISR ceased externally reporting against output targets, and ceased its regulator performance reporting for legal metrology, after 2019–20. DISR has not issued a Regulator Statement of Intent for its National Measurement Institute despite this being a requirement. (See paragraphs 3.52 to 3.80)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.12

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources implement stronger controls that ensure persons undertaking monitoring and compliance activities have been appointed in accordance with the relevant legislation, and that appropriate records are made and retained of all appointments.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.25

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources improve its record keeping processes to ensure that trade measurement business information and records are accurate, fit-for-purpose and are appropriately stored within departmental systems.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.61

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources put in place an improved approach to assessing the risk of legal metrology regulatory non-compliance at the industry and trader levels, and a transparent process that reflects the assessment of risk for selecting industries for targeting under its annual National Compliance Plans.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.27

In its activities related to the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 and the Tobacco Plain Packaging Regulations 2011, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources ensures that:

- appropriate priority is given to its responsibilities under the National Measurement Act 1960;

- its directions to officers are limited to the undertaking of education and investigation activities to promote compliance with the provisions of the legislation; and

- it is complying with its duties and obligations to those officers under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Partially Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.44

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources strengthen its approach to conducting follow-up audits where an initial trader audit identifies non-compliance such that follow-up activities are conducted in a timely manner, regulatory action taken where there is continuing non-compliance and appropriate records made and retained.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.81

As regulator of Australia’s legal metrology system, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources:

- apply Resource Management Guide 128: Regulator Performance; and

- establish indicators of, and report on, the effectiveness of its regulatory approach.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

18. The proposed audit report was provided to DISR and an extract was provided to the Department of Health and Aged Care. The letters of response that were received for inclusion in the audit report are at Appendix 1. Entities’ summary responses are provided below. The improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are at Appendix 2.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources (the department) acknowledges the audit report and welcomes the findings as an opportunity to improve.

The unique and critical functions of the National Measurement Institute (NMI) are central to unlocking innovation and leading advancements in science and technology. NMI received $63.9 million in the 2023-24 budget to sustain its core measurement capabilities and modernise Australia’s measurement laws. Updating legislation to be more principles-based will help new technologies get to market faster while retaining consumer and business protections.

The department’s commitment to continuous improvement responds to an environment of rapid technological change and increasing costs of administering trade measurement law. NMI is developing options for Government to achieve ongoing financial sustainability and meet rising demand from industry.

The department notes that the scope of the audit coincided with the impacts of the COVID 19 pandemic. Compliance activities were undertaken in a way that protected the health and safety of trade measurement inspectors and supported the Government’s response to COVID 19.

The department commits to continuing and completing a range of improvements already under way, including to Trade Measurement Inspector appointments and activities, document management, risk and accountability frameworks and reporting responsibilities.

Department of Health and Aged Care

The Department of Health and Aged Care (the Department) acknowledges the findings available in the extract of the report provided and notes the recommendation directed at the Department of Industry, Science and Resources in respect of activities related to the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011.

Since December 2012, all tobacco products in Australia were required to be sold in plain packaging and feature graphic health warnings. The continued monitoring and enforcement of plain packaging requirements is an essential component of Australia’s comprehensive approach to tobacco control.

The inspection scheme undertaken by the National Measurement Institute achieves a high-quantity, low-time investment balance, to ensure that retailers of tobacco products receive the greatest possible exposure to compliance activities and information. Where suspected illicit tobacco products are identified through compliance activities undertaken by the National Measurement Institute, the Department refers information to the relevant law enforcement agencies.

On 30 November 2022 the Australian Government announced significant tobacco control reforms with the aim of consolidating and modernising existing tobacco control legislation, including the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011. The Department notes the audit will inform consideration of future compliance activities, including under the proposed Public Health (Tobacco and Other Products) Bill 2023.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Measurement is integral to any well-functioning and productive economy, and plays a critical role in domestic law and international treaties for trade, commerce and consumer protection. Following a decision of the Council of Australian Governments to transfer trade measurement responsibilities from the states and territories, national trade measurement commenced on 1 July 2010. Trade measurement refers to all transactions in which the price of the commodities or goods is based on measurement of quantity or quality. The primary purpose of Australia’s trade measurement system is to ensure that the pricing of traded goods is based on accurate measurement. Trade measurement covers both business-to-business transactions and business-to-consumer transactions. Australia’s trade measurement transactions are estimated to be worth more than $750 billion each year.

1.2 The Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR), through the National Measurement Institute (NMI)1, administers Australia’s trade measurement laws. It is responsible for ensuring that businesses and individuals comply with the rules and regulations so that there is accurate and reliable measurement in trade. As part of this responsibility, DISR, through its NMI function, undertakes trade measurement compliance activities that include:

- conducting trader audits;

- testing measuring instruments in use for trade;

- testing pre-packaged goods;

- monitoring trading practices through trial purchases; and

- conducting enforcement activities where non-compliance has been identified.

1.3 DISR reported that in 2021–22 the NMI had:

- conducted 3131 trader audits (compared to 7600 in 2019–20 and 4842 in 2020–21);

- tested 7118 measuring instruments (compared to 13,588 in 2019–20 and 14,049 in 2020–21); and

- inspected 17,360 lines of packaged goods (compared to 78,290 in 2019–20 and 25,990 in 2020–21).2

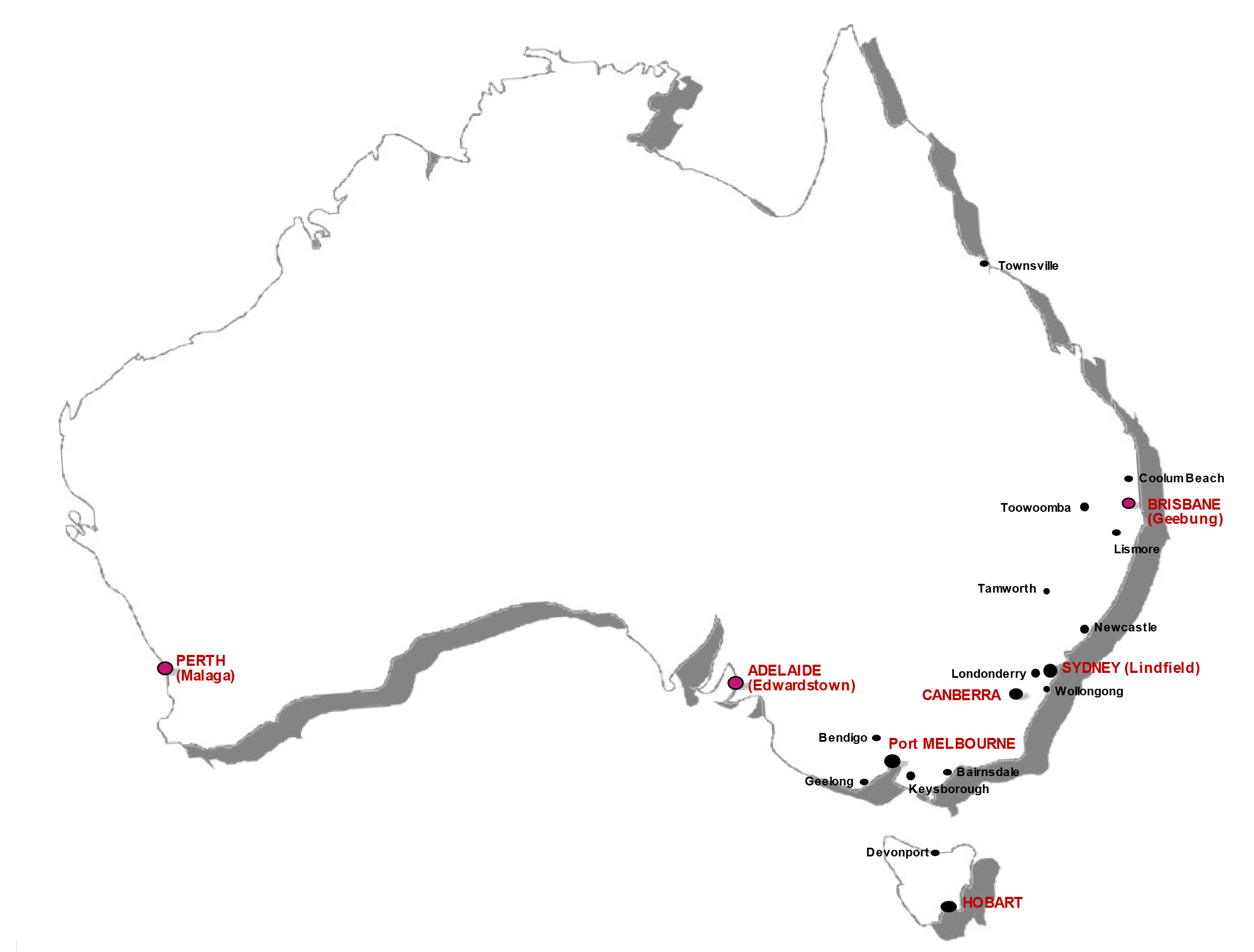

1.4 DISR reports the NMI as having more than 350 staff, of which 76 are estimated by DISR to work in trade measurement.3 The NMI has offices located around Australia with its head office located in Sydney (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: National Measurement Institute office and laboratory locations

Note: The red dots identify Measurement Standards laboratory locations.

Source: Department of Industry, Science and Resources.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.5 The activities of the department, through its NMI function of trade measurement, impact on everyday life. The department has regulatory responsibility to ensure that the pricing of traded goods, based on quantity or quality, is based on accurate measurement. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of DISR’s administration of trade measurement.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.6 The objective of the audit was to examine whether compliance with trade measurement in Australia is being effectively administered.

1.7 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Have sound governance arrangements been established to support trade measurement compliance activities?

- Is there an effective approach to trade measurement compliance activities?

1.8 The scope of the audit covered the period from 1 July 2019 until 30 June 2022. In relation to examining the adoption of a risk-based approach to regulation, the audit focussed on the two programs where DISR has documented approach to assessing compliance risk, being the concentrated national audit and compliance confidence programs. Concentrated national audit programs focus on targeted industry sectors over a specific time period to assess compliance with trade measurement legislation. Under the compliance confidence programs, DISR targets a selection of traders and industry groups found to be non-compliant in previous years.

Audit methodology

1.9 The audit methodology included:

- reviewing and analysing relevant departmental records;

- reviewing and analysing relevant data in the Trade Measurement Activity Recording System (TMARS) relating to trade measurement compliance activities4;

- collecting and reviewing email accounts;

- examination of a sample of trader audits and enforcement actions;

- meetings with key staff; and

- observing the conduct of trade measurement compliance activities by departmental officers in four states and territories, and site visits to two NMI offices.

1.10 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $458,000.

1.11 The team members for this audit were Tiffany Tang, Nicole McNee, Tracey Bremner and Brian Boyd.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) had established sound governance arrangements to support the administration of trade measurement compliance activities, particularly of its trader audits.

Conclusion

Sound governance arrangements were not fully in place to support trade measurement compliance activities. A wide range of policy and procedural documents have been developed. However, there are gaps, overlaps and inconsistencies in those documents and they have not been updated in a timely manner. Evidence that appropriate appointment processes of officers under the relevant legislation are not consistently implemented exposes the department to a risk that actions taken in compliance activities are invalid. The annual targeting of compliance activities to particular industry sectors is not demonstrably risk-based, and the risk-based approach to selecting individual traders within targeted industries requires improvement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made three recommendations to DISR to improve: the appointment process for persons undertaking trader audits; its record keeping processes; and the approach to assessing compliance risk and selecting higher-risk industries for targeted activities.

2.1 Procedures and guidance are important to ensure the delivery of policy, including regulation, is consistent with achieving intended outcomes. The ANAO examined whether DISR had appropriate policies, procedures and guidance in place to support the administration of trade measurement compliance activities.

2.2 Best practice regulators take a risk-based approach to compliance activities and are informed by data, evidence and intelligence. Regulators that assess the risk of non-compliance are better positioned to focus limited resources on areas of greatest impact.5 The ANAO examined DISR’s approach to assessing the risk of regulatory non-compliance and the extent to which the results informed the targeting of its trader audit activities.

Are appropriate policies, procedures and guidance in place?

While DISR has many documents that cover a range of processes, there are gaps in the policies and procedures in place to support departmental officers in the administration of trade measurement compliance activities. Documents often overlapped and were not updated in a timely, consistent and transparent manner. Of the 60 officers that have undertaken trader audits in the period examined by the ANAO, 58 per cent had not been appointed in writing (as required by the National Measurement Act 1960) prior to undertaking their first audit, or there was no record of them having ever been appointed in writing. This impacted 1399 (eight per cent) of the 16,590 trader audits undertaken in the three-year period to 30 June 2022 examined by the ANAO.

2.3 The primary objective of trade measurement compliance activities is to assess whether traders are complying with their obligations under trade measurement laws.6 DISR officers who are appointed as trade measurement inspectors are responsible for conducting trader audits to monitor trader compliance.7 Inspectors may undertake different activities during a trader audit including:

- testing measuring instruments;

- checking pre-packaged articles8;

- checking trading practices9; and

- conducting ‘secret shopper’ trial purchases.

2.4 Trader audits may be conducted as part of a trade measurement compliance program, or in response to a complaint or enquiry from a consumer.10

Appointment of trade measurement inspectors

2.5 Under section 18MA of the National Measurement Act 1960, the Secretary may by instrument in writing, appoint a person as a trade measurement inspector if that person has the prescribed qualifications, knowledge or experience and falls under one of the following categories:

- an APS employee in the department;

- an employee (whether or not an APS employee) of a Commonwealth authority;

- the holder of an office established by or under a law of the Commonwealth.

2.6 The people eligible to be appointed as trade measurement inspectors are limited to Commonwealth employees due to the search and entry powers conferred upon them. A person that has not been appointed by written instrument as a trade measurement inspector is unable to legally undertake monitoring and enforcement activities under the legislation, such as to enter and search business premises, inspect business vehicles, seize certain things, require answers to questions and issue non-compliance notices.11

2.7 The Secretary of DISR signed an instrument in May 2017 delegating functions and powers under the National Measurement Act 1960, including the power to appoint trade measurement inspectors. In a report of October 2019, a legal firm engaged by DISR recommended that this instrument be amended to rectify a number of identified risks. The instrument had not been amended as at June 2023, notwithstanding the legal advice or that the holder of the position of Secretary had changed twice since 2017 (in February 2020 and again in August 2022). The Australian Government Solicitor advises that ‘it is clearly good administrative practice to provide new office-holders with the opportunity to reconsider arrangements for delegated decision-making and issue new instruments of delegation’.12

2.8 A further shortcoming in the department’s approach was that all copies of the legal advice were marked ‘draft’. Not finalising draft legal advice13 is not a sound reason for entities to not action the advice.14

2.9 As at 31 December 2022, DISR did not have a policy or procedure in place relating to the appointment of trade measurement inspectors.15 The ANAO observed that written instruments of appointment for trade measurement inspectors were not appropriately filed within DISR’s systems for all relevant individuals. Between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2022, a total of 16,590 trader audits were recorded as having been completed by 60 individual inspectors in TMARS.16 Of those 60 individuals:

- 40 (67 per cent) had instruments of appointment filed within DISR’s systems17;

- 12 were appropriately appointed as a trade measurement inspector under an instrument prior to completing their first trader audit; and

- 28 were appointed after already having completed their first trader audit (the maximum time taken between the first trader audit being completed and the instrument being signed was 5.8 years, with the average being 9.8 months);

- 13 (22 per cent) had scans of the hard copy instruments of appointment subsequently filed within DISR’s systems after the ANAO requested further information (all inspectors had been appropriately appointed prior to completing their first trader audit)18; and

- seven (12 per cent) did not have evidence of a valid appointment.

2.10 In aggregate, 1399 of the 16,590 trader audits undertaken between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2022 were conducted by a person that either had not yet been appointed (67 audits)19 or there is no record of them having ever been appointed (1332 audits). Of those 1399 trader audits, 456 or 33 per cent resulted in a ‘Failed’ audit result. In June 2023, DISR advised the ANAO that it ‘considers it cannot take valid enforcement actions where the audit was conducted by a person not appointed, or not yet appointed, under the legislation.’

2.11 In December 2022, DISR moved to having a single instrument of appointment in the form of a Schedule that lists all departmental staff appointed as trade measurement inspectors, rather than having separate certificates issued to each individual as the appointment instrument. The new instrument does not of itself mean that persons undertaking monitoring and compliance activities have been appointed before undertaking this work. For example, based on TMARS data the ANAO identified seven audits conducted after the new instrument was introduced which had an unappointed officer listed as the ‘Inspector’ within TMARS, and no appointed officer listed as assisting. In July 2023, DISR provided the ANAO with records that indicated TMARS had not recorded that four of those seven audits had been conducted under the supervision of a person that had been appointed.

Recommendation no.1

2.12 The Department of Industry, Science and Resources implement stronger controls that ensure persons undertaking monitoring and compliance activities have been appointed in accordance with the relevant legislation, and that appropriate records are made and retained of all appointments.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

2.13 In February 2023, the department introduced stronger controls including a centralised process and instrument to appoint and record the appointment of Trade Measurement Inspectors. The department will continue to utilise these controls to ensure that appropriate records are kept of all Trade Measurement Inspector appointments.

2.14 The department will implement a new policy outlining when and how persons, who are not appointed as a Trade Measurement Inspector, can support trade measurement compliance activities. The department will also update guidance on what constitutes a trader audit.

Policies and procedures

2.15 In response to the ANAO’s request for an inventory of the National Measurement Institute’s (NMI) documents, DISR provided in June and July 2022 three spreadsheets that comprised the document lists. The document lists were separated into: documents directly related to trade measurement activities; and other overarching documents related to the legal metrology framework.20 In total, there were 184 documents listed as being in effect and 263 with a status of ‘Potential’.21

2.16 DISR’s internal records management policy requires that the NMI use Content Manager (the department’s record keeping system) to store and access documents and digital information.22 Of the 184 current documents, 77 were identified by DISR as being ‘directly related to trade measurement activities’. These 77 documents were filed across five different folders/containers within Content Manager. The effective dates of the documents spanned over a period of more than 10 years, with the oldest document having been last revised in February 2012 and the newest document being approved in June 2022.23

2.17 The ANAO’s examination of DISR’s policies and procedures identified instances where documents were confusing and incomplete (see Appendix 3 for further details and examples). The ANAO also identified gaps in the available guidance material and some areas where the documents could be improved.

- There is an absence of TMARS-specific guidance which outlines how inspectors are to record information related to trader audits within TMARS and the level of detail required (see paragraphs 3.41–3.42 and 3.74–3.76 for further details on the inconsistencies observed by the ANAO in how information is input into TMARS and the level of detail recorded against trader audits).

- There is no policy or guidance relating to the management of hard copy inspector notebooks and non-compliance notices by DISR officers (see paragraph 3.43 for further details on missing notebooks and notices). In June 2023, DISR advised the ANAO that:

As of 20 April 2023, several actions were taken to improve guidance and processes for management of hardcopy inspector notebooks including: all inspector notebooks being recorded in TMARs as an asset, LMB Procedure 8.18 ‘Updating asset details in TMARS’ has been updated to include guidance regarding inspector notebook management and a new Inspector Handbook known as Draft LMB Procedure ‘Inspection and investigation’ is in draft format and will include guidance relating to storage of inspector notebooks.

- The ANAO’s analysis was that the process of recording all issued notebooks in TMARS as an asset was completed on 21 June 2023. LMB Procedure 8.18 (approved on 10 February 2023) does not include reference to inspector notebooks24 and does not include guidance regarding the management or storage of those notebooks by inspectors. Further, draft LMB Procedure – Inspection and Investigation does not include any reference to the storage of inspector notebooks.

2.18 The ANAO also observed that existing policies and procedures were not being updated in a timely manner (see Table A.1 in Appendix 3 for examples). It is important to maintain the currency of all supporting documentation, including metadata, to enable robust data management and analysis. This will also ensure the implementation of legislative or policy/procedural changes is consistent with achieving intended outcomes. To obtain an indication on the currency of the 77 policies and procedures related to trade measurement activities, the ANAO examined the time lapsed since the documents were last approved/reviewed, as at 30 June 2022. For this analysis, the ANAO did not include: 12 documents that were plans for specific programs undertaken in 2021–22 and one document which did not have an approved/reviewed/effective date. Of the remaining 64 documents, 17 (27 per cent) had been approved or reviewed more than five years ago (see Figure 2.1).25

Figure 2.1: Time lapsed since documents last approved/reviewed as at 30 June 2022

Note: This analysis did not include 13 documents: 12 were plans for specific programs undertaken in 2021–22 and one did not have an approved/reviewed/effective date.

In July 2022, DISR advised the ANAO that one of the documents in the ‘8 to 9 years’ category had been made obsolete.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

Internal audit findings

2.19 At a cost of $64,000, Nous Group was contracted to conduct an internal audit of the NMI’s trade measurement regulatory performance. The report was completed in April 2018. It found that:

LMB has many policies and procedures that cover a range of processes, including policies on enforcement actions and investigation procedures. However, many are scattered across LMB’s IT infrastructure and most have not been reviewed for a while. A few stakeholders observed that some policies and procedures were not used, and others were out of date. One stakeholder considered that some staff don’t know where to find relevant documents.

This issue was identified a year ago, and a project was initiated to gather them in one directory and review them periodically. This project will make every instruction, policy, and procedure available in one location sorted by Branch. There will also be an ongoing review process for policies and procedures so that they are all updated on a regular basis, based on consultation with the original author of the document.

2.20 Two related internal audit recommendations were that the NMI:

1. Consolidate policies and procedures following the review.

2. Make a designated person or team responsible for updating policies and procedures in line with performance insights.

2.21 Following an internal review in 2019 of the LMB structure, the NMI commenced the LMB Structure Pilot in March 2020 which transferred responsibility to the Policy Unit for ‘Facilitating the development and maintenance of non-technical documentation on behalf of LMB’. In February 2023, the NMI provided the following information about the LMB document management project:

- The Policy Unit began a stocktake of documents currently used or identify for use within LMB. These documents were found in various states of approval and locations. As of 3 February 2023 nearly 1700 documents have been identified in the LMB Document Register.26

- The stocktake identified the potential need for the review or creation of 300 - 350 critical LMB documents (policies, plans and procedures).

- On 1 October 2020 LMB introduced a new document management system for critical LMB documents not covered by other quality systems. The laboratory and training functions within LMB are already subject to separate quality systems that include their critical documents.

- As of 3 February 2023, 67% (40/61) of the old LMB documents have been updated, merged or archived. In the same period 142 new LMB documents were approved and another 57 are currently under development.

- The new document management system outlines the responsibility of the (currently 13) document owners. The Policy Unit meets with the document owners approximately every 6 weeks and have provided weekly updates to the LMB General Manager.

Managing and maintaining records

2.22 Many of the documents relating to the administration of trade measurement activities were not created and/or maintained within Content Manager but in network drives.27 For example, in respect of records relating to investigations and compliance, as at 28 September 2022, 3025 records were saved across 422 sub-folders within the NTM Group shared drive. There was no equivalent or similarly titled container/folder within Content Manager. The closest was a container/folder called ‘Compliance enforcement’ with four records saved in one sub-folder.

2.23 There were also instances where records relating to trade measurement compliance activities (including changes/updates to procedures and processes, decisions on enforcement actions and reporting on program progress) were not maintained in DISR’s record management system (Content Manager), but were only available in officer email accounts or business systems (such as TMARS). Due in part to the insufficiencies of the files, the ANAO obtained extracts of 106 email accounts to inform this audit.

2.24 Paragraphs 3 and 4 of Appendix 3 provide further details on DISR’s management of Commonwealth records.

Recommendation no.2

2.25 The Department of Industry, Science and Resources improve its record keeping processes to ensure that trade measurement business information and records are accurate, fit-for-purpose and are appropriately stored within departmental systems.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

2.26 The department had commenced a review, prior to the audit, of its policies and procedures, with a focus on completion of higher priority documentation, to be completed by the end of 2023.

2.27 However, the department commits to regular reviews to ensure trade measurement business information and records are accurate, fit-for-purpose and are appropriately stored within departmental systems. The department will undertake refresher training for Legal Metrology Branch staff in the use of the department’s record keeping and store in place systems.

2.28 The department acknowledges gaps in procedures associated with Trade Measurement Inspector practices and the use of the departmental record keeping system. The department will develop guidance materials outlining Trade Measurement Inspector practices and use of the departmental record keeping system.

Is the regulatory approach informed by an assessment of compliance risk?

The regulatory approach is not fully and appropriately informed by an assessment of compliance risk. DISR identified the need for a more sophisticated risk framework for legal metrology in December 2015. While progress has been made, trader audit activities are not yet being effectively and demonstrably targeted to market sectors and traders at higher risk of regulatory non-compliance. There is not a strong relationship between industry-level risk assessments and the department’s targeting of compliance activities and development of the annual National Compliance Plans. While DISR has introduced a risk-based approach for selecting individual traders for audit within those sectors being targeted, the approach should be improved.

2.29 DISR has documented that its administration of legal metrology regulatory compliance will be informed by an assessment of compliance risk. Its published National Compliance Policy and annual National Compliance Plans, for example, state that:

- ‘We use a risk-based approach when … targeting compliance activities’; and

- ‘We measure risk in terms of the harm and likelihood of regulatory non-compliance.’

Internal audit findings and responses

2.30 An internal audit of the NMI’s legal metrology activities was completed in December 2015 by NERA Economic Consulting at a cost of $267,106. The ‘overarching findings’ included that:

while the NMI has a risk framework for legal metrology, it is unsophisticated. It does not articulate the risks of non-compliance (i.e. what harm or detriment is being experienced, by whom) and does not appear to be proportionate to risk. The NMI currently focuses its compliance activities on ensuring the accuracy of measurement rather than focusing on minimising harm. The current risk framework has also been ineffectual in directing the compliance and enforcement activities to areas of high non-compliance and delivering a nationally consistent approach to legal metrology …

[the internal audit] anticipates that introducing a risk-based approach to regulation will require a significant program of change within the Legal Metrology Branch that will impact every facet of its operations and will require a strong change agent to drive these reforms.

2.31 Three related internal audit recommendations were that the NMI:

- publish a strategic plan to communicate how it intends to deliver on the Government’s objectives and report on its performance on a regular basis; [and]

- reform its compliance and enforcement policy to align with the principles of a risk-based approach to regulation; [then]

- reset its approach to targeted inspections, its enforcement thresholds, and its education/communication activities to reflect a risk-based approach to regulation.

2.32 DISR recorded that implementation of the above three recommendations was ‘Complete’ by the milestone date of 30 June 2017, with a delivery confidence of ‘High’, based largely on the provision of three documents. The ANAO’s analysis is that these documents did not implement the internal audit recommendations, as follows.

- 2017–18 National Compliance Plan — Plans are produced annually. The ANAO compared the 2017–18 plan with two that preceded the 2015 internal audit report. It did not differ from the previous plans in a manner that would implement the recommendations or address the related findings.

- 2017 National Compliance Policy — The three-page 2017 policy replaced an 11-page 2011 policy. The 2017 policy did not differ in a manner that would implement the recommendations or address the related findings.

- 2017 Non-Compliance and Enforcement Protocol — The six-page 2017 document replaced a 14-page 2014 document and was not applicable to the ‘targeted inspections’ or ‘education/communication activities’ components of the recommendation.

2.33 DISR also recorded against one of the above recommendations that ‘NMI has changed its approach to inspections and now uses data from [TMARS] to inform risk-based targeting’. The ANAO’s analysis of this assertion is that it has not yet been effectively and demonstrably delivered, for the reasons set out in the remainder of this Chapter.

2.34 A methodology and proposed data sets for assessing compliance risk at the industry-level were outlined in a Trade Measurement Risk Based Monitoring Program Evaluation Principles (‘risk principles’) document dated February 2017. While DISR did not reference this document when tracking implementation of the December 2015 recommendations, it had the following related purpose.

The [internal audit of December 2015] considered NMI’s focus on regulating for accuracy rather than regulating to prevent harm or negative impact is not a best practice approach to regulation. This document details a strategy for identifying future risk based monitoring programs focussed on minimising harm rather than regulating for measurement accuracy …

The purpose of this document is to provide a three stage strategy to implement by July 2018 a sophisticated risk based framework for trade measurement monitoring (inspection) programs with a primary focus on minimising harm.

2.35 The risk principles document explained that an industry risk assessment ‘should be undertaken for the previous 1, 2 and 5 calendar years, to identify the ten industries with the greatest potential risk or harm to the Australian community’. The explanation did not extend beyond this to the development of the annual National Compliance Plans, and the methodology did not extend to assessing risk at the trader-level.

2.36 An internal audit completed by KPMG in May 2020 recommended that NMI ‘Formalise and document the methodology used for the collation of Annual Program Plans, including the considerations staff should use in the selection of traders’. For context, the internal audit report outlined:

It is important that the department has documented a defendable approach to support the integrity of the selection process for both annual programs and traders …

[The] selection of programs and traders may not have been targeting the areas of highest risk as the methodology for compiling the annual planning and trader selection has not been clearly defined, which may have resulted in staff undertaking inspections of low risk programs and traders.

2.37 NMI was advised that ‘To close this recommendation, Internal Audit will need to see the methodology that has been produced during the development of the 2021/22 Annual Program Plans — this should include consideration staff need to use in the selection of traders’. The due date to provide the methodology was originally 31 March 2021, which was then extended to 30 June 2021. The recommendation was closed on the basis of NMI providing a risk principles document dated 30 June 2021.

2.38 The risk principles document of June 2021 was largely identical to the risk principles document of February 2017. The methodology was not, therefore, ‘produced during the development of the 2021/22 Annual Program Plans’ and it did not include ‘considerations staff need to use in the selection of traders’. The minor differences in the wording of the June 2021 version included that: the three stage strategy was written in the past tense; the target implementation date of ‘July 2018’ for Stage 3 was deleted; and the words ‘Stage 3’ were deleted from the heading ‘Future Data Sets to be considered for use in Stage 3’. The 10 data sets listed under that heading were not yet in active use as at 31 March 2023 (see paragraph 2.43).

Assessing compliance risk at the industry-level

2.39 In response to ANAO requests for its industry-level risk assessments and methodology, DISR provided in August 2022 (and again in October 2022) a copy of the risk principles document dated June 2021 and three spreadsheets produced in November 2021 that comprised the ‘industry risk assessment 1, 3 and 5 years’. The difference between the spreadsheets was the time span of the data used, being 1 July 2016–4 November 2021, 1 July 2018–4 November 2021 and 1 July 2020–4 November 2021.

2.40 There were 43 market sectors (or trader types) listed in the spreadsheets, which were a sub-set of the 59 sectors listed in TMARS. DISR did not document why it chose to leave some of the sectors out of the risk assessment, such as the ‘Manufacturer – Food’ sector for which more trader audits were completed during 1 July 2018–4 November 2021 than 70 per cent of the sectors in the spreadsheets.

2.41 The spreadsheets ranked the 43 market sectors in order of relative risk according to a numerical ‘risk factor’ calculated for each. The lower the rank, the higher the potential harm and likelihood of regulatory non-compliance.

2.42 The ANAO identified shortcomings with the basis on which the risk factor was calculated. These reduced the reliability of the rankings and the extent to which risk was being measured in terms of the harm of regulatory non-compliance, and not just the likelihood. The December 2015 internal audit had found that NMI’s risk framework did not focus on minimising harm (see paragraph 2.30).

2.43 The risk principles document stated that the calculation of the risk factor for each sector would be based on ‘a minimum of 12 different data sets’. The spreadsheets presented 19 different data sets, however 12 of these had no impact on the ranking of sectors. For example, 10 of the data sets had no impact because a risk rating of ‘1’ (minor) was hard-keyed against every sector. That is, there was no data in the 10 data sets. These 10 data sets were indicators of the relative level of harm that may result from non-compliance and required data external to TMARS to populate.

2.44 One of the seven data sets that did impact the ranking of sectors sought to measure the harm or detriment of regulatory non-compliance through the ‘projected annual community detriment based on initial visits’. In reference to this measure, the risk principles document had stated: ‘At present the available community detriment data is insufficient to reliably use this data as part of the total risk evaluation’. The data set was unreliable because the population of traders in TMARS may not represent the population in the community and because the financial detriment data in TMARS contained errors.28 For example, following a Major Supermarkets Audit conducted in 2020 under which 195 non-compliance notices were issued, DISR identified that ‘In the majority of instances of non-compliance (customer detriment), no financial detriment estimation was recorded, and in the cases where a figure was included there was no consistency in the way the figure was determined’. Failure to complete the financial detriment fields in TMARS was the most frequent error picked up in the data quality reports until May 2021, at which time the fields were removed from the data quality script which meant that the errors were no longer reported. The fields still appear in the department’s Data Quality Management Processes document (last updated 27 May 2022) as though they are captured in the reporting.

2.45 Additional information on the risk assessment spreadsheets and their key shortcomings is in Appendix 4 (paragraphs 2–3 and Table A.3).

2.46 In June 2023, DISR advised the ANAO that:

Data driven risk-assessment processes are a key component used when selecting target trader sectors. However, DISR also uses additional qualitative, anecdotal and workforce information to inform the selection of target trader sectors. These additional factors include stakeholder feedback, trade measurement inspector feedback, consumer sentiment (e.g. cost of living pressures), consideration of broader government priorities (e.g. consumer protection or regulatory burden) and operational constraints ensuring the efficient use of a finite inspector workforce. DISR acknowledges that the current published and internal information does not articulate that the data-driven risk assessment processes is supplemented by other information.

Targeting compliance activities at the industry-level

2.47 The use of assessed risk is most relevant to the targeting of trader audit activities under the ‘concentrated national audit’ and ‘compliance confidence’ programs.29 It was not evident to the ANAO from the records examined how DISR used the risk assessments as a ‘key component’ when selecting industries for targeting through these programs. DISR advised the ANAO in June 2023 that:

Industries targeted under the compliance confidence program are determined with reference to the previous year’s targeted industries and not the “Industry risk assessment spreadsheet”. The compliance confidence program focuses on industries or trader types that have previously been non-compliant or subject to an enforcement action to determine if there is a long-term change in compliance levels through the intervention of DISR compliance activities. …

Each year DISR refresh their 1, 3 and 5 year risk assessments that are used to determine industries to target for the forward financial year. The 1 July–4 Nov 2021 ranking would only have been used to help determine target industries for the 2022–23 financial year.

Concentrated national audit program

2.48 The ANAO requested copies of the ‘1, 3 and 5 year risk assessments’ that DISR used to determine industries to target through its concentrated national audit program in each of 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22. DISR was unable to provide a set of ‘1, 3 and 5 year risk assessments’ for any of these years, which was contrary to DISR’s assertions of June 2023 and to the process outlined in its risk principles documents of February 2017 and June 2021 (see paragraph 2.35).

2.49 DISR was able to provide the ANAO six spreadsheets in June 2023:

- two spreadsheets covering the same unspecified period for its 2019–20 planning;

- one spreadsheet covering one unspecified period for its 2020–21 planning; and

- three spreadsheets covering two specified periods (being 1 July 2016–30 June 2020 and 1 July 2017–30 June 2020) for its 2021–22 planning.

2.50 The ANAO examined the extent to which DISR’s selection of industries, or trader types, for targeting was consistent with the results of its industry risk assessments. For the purpose of this analysis, the ANAO considered the four National Compliance Plans from 2019–20 and used the nine industry risk assessments provided by DISR (being the three spreadsheets provided in 2022 and the six spreadsheets subsequently provided in June 2023).

2.51 The ANAO’s analysis indicated there was a weak alignment between a trader type’s assessed risk and its selection for targeting under the concentrated national audit program. Of note:

- DISR had assessed three-quarters of the trader types it selected for the program as having an above average risk.

- The one-quarter DISR selected with a below average risk included ‘licensed premises’, ‘poultry retail’ and ‘smallgoods’.

- Those DISR did not select for targeting in any of the four years under any program, despite rating them as comparatively high risk, included ‘mining and resources’, ‘recycling’ and ‘small business – food’ (which had the highest risk rating in seven of the nine spreadsheets examined).

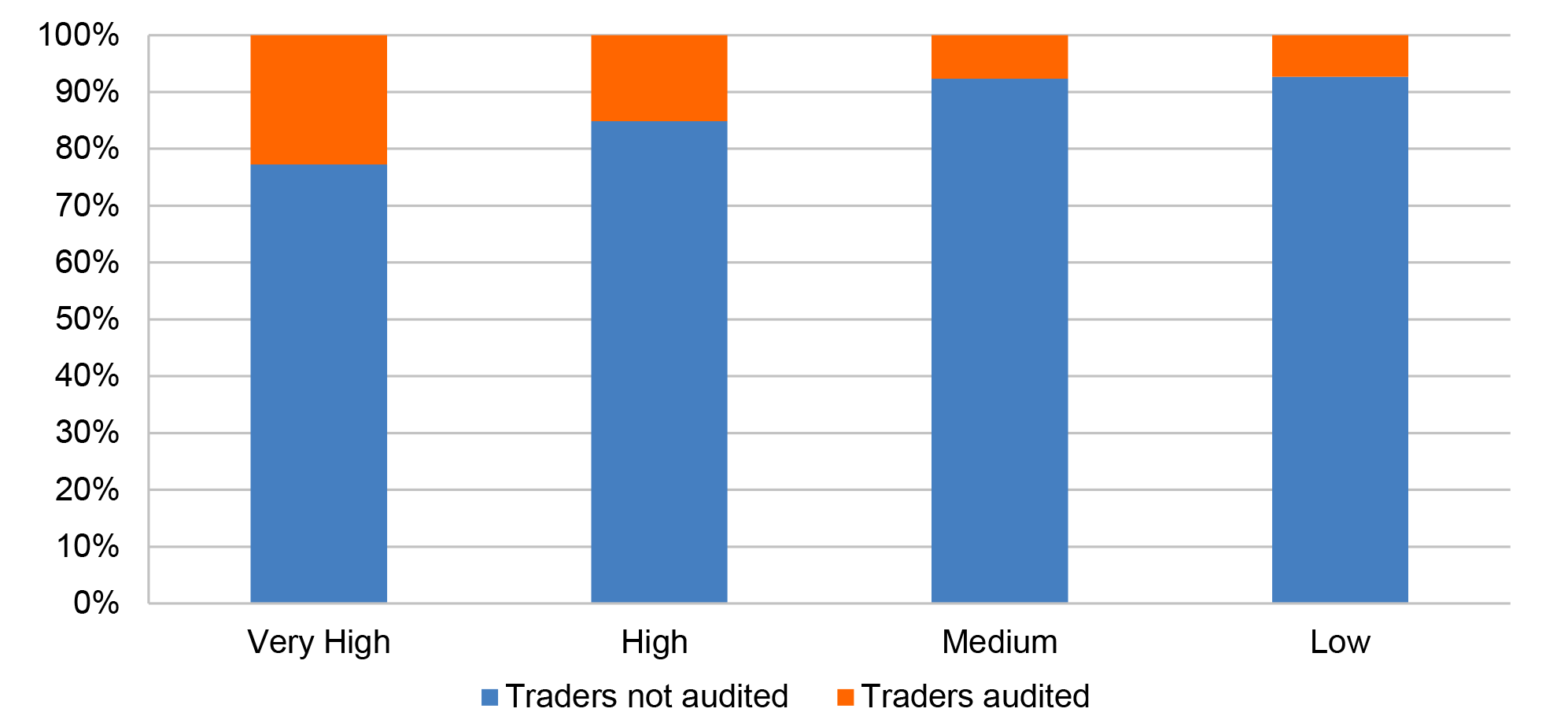

2.52 The ANAO’s analysis covered both the risk rankings and the risk factors assigned by DISR. The analysis of the risk rankings included identifying the number of trader types assigned to each of the 43 possible ranks in each of the nine spreadsheets (DISR ranked trader types in declining order of risk from one to 43, assigning those with the same risk to the same rank). The number of trader types at each ranking that DISR selected for its concentrated national audit programs, compared with those it chose not to select for either its concentrated national audit or compliance confidence programs, is presented in Figure 2.2.30

Figure 2.2: Risk ranking of trader types selected for targeting under the concentrated national audit program

Source: ANAO analysis of nine risk assessments provided by DISR and four National Compliance Plans from 2019–20.

2.53 In July 2022, DISR briefed the Minister for Industry and Science on its National Compliance Plan for 2022–23 and listed the three sectors chosen for its national concentrated audit program: fruit and vegetable retailers; meat, fish and poultry retailers; and delicatessens and smallgoods retailers. The Minister asked, ‘why are these three being targeted?’ and DISR responded in August 2022 as follows.

NMI takes a risk-based approach to selecting market segments for targeted compliance activities. In relation to historical compliance data, the three target market segments above have been subject to previous audit programs undertaken between 2017 and 2021.

- Previous compliance programs found high instances of non-compliance during initial and follow up audits, including significant non-compliance (significant non-compliance is when there is a detriment to a customer such as a shortfall in the product advertised).

- High numbers of enforcement actions were issued to the three market segments following previous audit programs.

2.54 DISR’s advice to the Minister was not supported by the departmental data, nor was the basis on which the market segments were selected otherwise evident from the records. Delicatessen and smallgoods retailers had not been targeted between 2017 and 2021. Further, the data DISR extracted to inform its response to the Minister contained no enforcement actions for poultry, delicatessen or smallgoods retailers. In terms of risk, DISR had ranked smallgoods retailers at a relatively low 37th out of the 43 sectors it assessed. DISR advised the ANAO in June 2023:

DISR acknowledges the information provided to the Minister implied high instances of non-compliance actions for poultry, delicatessen and smallgoods retailers which was incorrect. DISR will work with the Minister’s office to clarify the advice provided.

2.55 In August 2023, DISR advised the ANAO that ‘The Acting Head of Division, National Measurement Institute has raised this issue with the Minister’s Office’, and provided evidence to the ANAO that it had done so.

Compliance confidence program

2.56 The ANAO examined the extent to which DISR’s selection of industries, or trader types, for targeting through its compliance confidence program in each of the three years from 2020–21 had an above average level of non-compliance and enforcement actions the previous year. (The 2019–20 National Compliance Plan had not specified industries for this program type.)

2.57 The ANAO’s analysis indicated a moderate alignment. Of the trader types DISR selected for the compliance confidence program, three-quarters had above average non-compliance and most had an above average number of warning letters and/or infringement notices issued.

Taking a risk-based approach at the trader-level

2.58 DISR introduced the use of trader-level risk assessments to inform trader selection in its 2022–23 ‘Tare It’ program.31 The program consisted of three one-week national concentrated audits, with each audit focussing on a different retail sector. The first concentrated audit was undertaken the week commencing 17 October 2022 and focussed on fruit and vegetable retailers.

2.59 DISR provided the ANAO with the trader-level risk assessment spreadsheet produced for the fruit and vegetable retail sector and outlined the assessment methodology in an email. The spreadsheet listed 2152 traders and calculated a numerical risk factor for each, drawing on 10 data sets. Each trader had been manually assigned a risk category on a four-point qualitative scale according to their relative risk factor. Trade measurement inspectors were provided a list of traders for their region and advised that ‘inspections should prioritise traders with the highest risk category (Very High to Low)’.32

2.60 A challenge with the approach is factoring in the assessment and selection of new traders for inspection. The spreadsheet was populated with the traders and trader audit data from TMARS. If a trader had not been visited previously, so was a ‘new trader’, then it was assessed as having a ‘Very High’ risk against two of the data sets. The impact was largely offset by it also being assessed as having a ‘Minor’ risk against the other eight data sets in the spreadsheet. The result was that all new traders were assigned the risk category ‘Medium’, which was the second lowest priority for inspection. This result is at odds with inspector guidance for other compliance programs that included ‘new traders’ in the list of priorities for trader selection. Further, TMARS does not contain a complete list of all traders within a given sector nationally.

Recommendation no.3

2.61 The Department of Industry, Science and Resources put in place an improved approach to assessing the risk of legal metrology regulatory non-compliance at the industry and trader levels, and a transparent process that reflects the assessment of risk for selecting industries for targeting under its annual National Compliance Plans.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources response: Agreed.

2.62 The department will continue to improve its processes as updates to regulator guidance, introduction of new analytical tools, and additional data sources technologies become available to refine the assessment of non-compliance risk at the industry and trader levels. The department will include information in its publications indicating how trade measurement compliance targets were selected.

3. Compliance activities

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) had implemented an effective approach to trade measurement compliance activities, particularly of its trader audits.

Conclusion

The department’s approach to trade measurement compliance has been partly effective. The department has appropriate approaches to monitor the level of compliance, however the level of monitoring activity (particularly trader audits) has declined significantly over the last five years, with no evidence that this was driven by a changed risk environment or risk assessment. Nearly a third of all trader audits conducted between 2019–20 and 2021–22 identified non-compliance. Action in response to identified non-compliance, including follow-up audits and enforcement actions, has not been timely or demonstrably effective. DISR’s monitoring and reporting arrangements did not extend to the effectiveness of its regulatory approach, with its regulatory reporting more generally declining after 2019–20 such that it has not complied with its obligations.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made three recommendations to DISR to: improve its approach to undertaking Tobacco Plain Packaging activities; strengthen its approach to conducting follow-up audits; and to meet its regulator performance reporting requirements and to monitor and report on the effectiveness of its regulatory approach. There is also an opportunity to improve the accuracy and consistency of its data.

3.1 Regulators have a responsibility to give confidence to Parliament, the Government and the community that regulated entities are complying with their statutory obligations and that appropriate enforcement action is taken when a regulated entity fails to meet its obligations. To assess whether there is an effective approach to trade measurement compliance activities, the ANAO examined whether:

- industry compliance is appropriately monitored;

- identified non-compliance is acted upon; and

- the regulatory approach is regularly reviewed and, where appropriate, updated.

Is industry compliance appropriately monitored?

A key component of monitoring industry compliance is the conduct of trader audits, with DISR reporting that 32,792 audits were conducted over the five years to 2021–22. The department’s data overstates the number of trader audits it undertakes.a There has been a downward trend in the number of trader audits planned to be conducted each year. The actual number of audits conducted has also fallen short of the target in each of the five years examined by the ANAO. In 2021–22, the department conducted 3131 audits which was less than half the target of 8000 audits which itself was significantly below the target of 11,500 audits for 2017–18. The department identifies in its National Compliance Plan particular industries to be targeted for compliance activity however the shortfall in performance against targets is as evident for the targeted programs as it is for the overall program of trader audits (59 per cent of planned audits under the targeted programs were not conducted in 2021–22).

There has been a similar declining trend across DISR’s other trade measurement inspection activities. There was a decrease of 52 per cent in the number of measuring instruments inspected between 2017–18 and 2021–22. There was a decrease of 76 per cent in the number of pre-packaged article lines inspected over the same period.

In comparison, the department has consistently exceeded the number of Tobacco Plain Packaging information visits undertaken by trade measurement inspectors on behalf of the Department of Health and Aged Care (the department receives separate funding from the Department of Health and Aged Care for this work). The evidence is that the department is prioritising this work it undertakes on behalf of another department over its own responsibility for trade measurement compliance. Further, the scope of this work has extended beyond the intended purpose of checking plain packaging to include examining whether traders are conducting illegal activities through the sale of illicit tobacco, with the related risks to the officers undertaking this work not adequately addressed by the department.

Note a: In June 2023, DISR’s advice to the ANAO in relation to the appointment of trade measurement inspectors was that ‘a trader audit involves a Trade Measurement Inspector exercising their powers under the National Measurement Act 1960 and is conventionally associated with physically visiting the trader’. The department also advised the ANAO that its database (that records the conduct of trader audits) includes inspection types that ‘did not exercise regulatory powers, such as desktop or online research of traders or a new trader program that did not involve site visits’. See further information at paragraph 3.6.

3.2 DISR’s trade measurement compliance activities are directed towards assessing whether traders are complying with their obligations under trade measurement laws. Compliance activities include trader audits which may be conducted as part of a trade measurement compliance program.

Performance against targets

3.3 Each year DISR publishes a National Compliance Plan on its website. The plan outlines the compliance programs and the compliance targets for the year ahead in relation to its inspection activities, including the number of trader audits to be completed.

3.4 As shown in Figure 3.1, the reduction that has occurred in the level of trader audit activity reflects both a plan to conduct fewer audits as well as a failure to deliver the planned number of audits.

- The largest reduction in the number of planned audits occurred between 2017–18 and 2018–19, when the department reduced its target by more than 30 per cent from 11,500 to 8000. The target was increased to 10,000 for each of 2019–20 and 2020–21 before being reduced again to 8000 for 2021–22.

- There has been an overall decline in the total number of trader audits conducted from 2017–18 to 2021–22 (a decrease of 67 per cent). The performance target has not been met once over the five-year period with 39 per cent of the target being achieved in 2021–22. In aggregate across the five years, the department conducted 32,792 (69 per cent) of the 47,500 audits it planned to conduct meaning there were 14,708 fewer audits than the department had identified as required to provide an appropriate level of compliance monitoring.

Figure 3.1: Target vs actual trader audits and proportion of non-compliance

Note: Where non-compliance is identified during a trader audit, a follow-up audit may be subsequently conducted to check whether the non-compliance has been corrected.

Source: ANAO analysis of DISR’s National Compliance Plans and National Compliance Reports.

3.5 The reduction in trader audit activity does not reflect improving levels of compliance. Across the five-year period, the level of non-compliance identified varied between 31 per cent and 35 per cent of the traders subject to an initial audit, and between 18 per cent and 27 per cent of follow-up audits also found non-compliance.

3.6 The ANAO’s analysis of the extent of trader audit activity is based on DISR’s National Compliance Reports and records of audits in the Trade Measurement Activity Recording System (TMARS).33 In June 2023, the department advised the ANAO that ‘a trader audit involves a Trade Measurement Inspector exercising their powers under the National Measurement Act 1960 and is conventionally associated with physically visiting the trader’. The department also advised the ANAO that TMARS includes records of inspection types that ‘did not exercise regulatory powers, such as desktop or online research of traders or a new trader program that did not involve site visits’. Nonetheless, in its public reporting on its compliance activities, the department includes those inspection types as a trader audit. The ANAO also observed instances where those inspection types were recorded as having identified non-compliance and enforcement action taken in the form of non-compliance notices.34 While TMARS includes fields to record trader audit information such as ‘Audit Type’ and ‘Program’, there is no separate field that identifies which inspection types should or should not be counted for reporting purposes.35

3.7 There has also been a declining trend across DISR’s other trade measurement inspection activities. As shown in Figure 3.2, the department reduced its target for the number of measuring instruments to be tested by 23 per cent from 13,000 in 2017–18 to 10,000 in 2018–19 (despite the target having been achieved in 2017–18). This target of 10,000 was maintained for three years, and exceeded in each of those years, before being increased to 15,000 in 2021–22. DISR achieved 47 per cent of its target in 2021–22. Overall, there has been a decrease of 52 per cent in the number of measuring instruments tested between 2017–18 and 2021–22.

Figure 3.2: Target vs actual measuring instruments tested

Source: ANAO analysis of DISR’s National Compliance Plans and National Compliance Reports.

3.8 As shown in Figure 3.3, for pre-packaged article lines the largest reduction in the planned number of lines to be tested occurred between 2017–18 and 2018–19, when the department reduced its target by 29 per cent from 85,000 to 60,000. The target was increased to 70,000 from 2019–20 to 2021–22. There has been an overall decrease of 76 per cent in the number of pre-packaged article lines tested over the five years examined, with DISR achieving 37 per cent of its target in 2020–21 and 25 per cent in 2021–22.

Figure 3.3: Target vs actual pre-packaged article lines tested

Source: ANAO analysis of DISR’s National Compliance Plans and National Compliance Reports.

3.9 While DISR includes targets on the number of ‘secret shopper’ trial purchases to be conducted each year in its National Compliance Plans, it does not report on the total number achieved in its National Compliance Reports (see further detail of the shortcomings of DISR’s external reporting at paragraphs 3.68–3.72).36

Resourcing

3.10 The performance targets for each inspection activity and compliance program are set by DISR based on the number of trade measurement inspectors available and an estimate of how many audits those inspectors can undertake.

3.11 The number of staff conducting trade measurement compliance activities, including trader audits, fluctuates throughout the year and some staff may have duties outside of trade measurement.37

3.12 DISR provided the ANAO with data on the staffing profile of the Legal Metrology Branch (LMB) within the National Measurement Institute (NMI) from 2017–18 to 2021–22. As shown in Table 3.1, while the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff allocated to trade measurement compliance activities has declined by 24 per cent from 2017–18 to 2021–22, the number of audits conducted per FTE has decreased at a greater rate (57 per cent over the five-year period). DISR advised the ANAO that the reduction in staffing levels was not driven by a lack of available resources, but the inability to attract and retain staff.38

Table 3.1: Ratio of staff to audits conducted each year

|

Year |

Full-time equivalent (FTE) staff |

Trader audits conducted |

Trader audits per FTE |

|

2017–18 |

75 |

9633 |

129 |

|

2018–19 |

76 |

7586 |

100 |

|

2019–20 |

69 |

7600 |

110 |

|

2020–21 |

63 |

4842 |

76 |

|

2021–22 |

57 |

3131 |

55 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

3.13 In June 2023, DISR advised the ANAO that:

Table 3.1 currently details all staff assigned to Trade Measurement Services, which includes staff who undertake supporting duties and would not be solely tasked to field based activities. These staff include Regional Managers, Assistant Regional Managers, Trainers and Assessors. Additionally, some staff have been seconded from time to time to support other Legal Metrology Branch (LMB) operations or surge requests.39

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

3.14 DISR reported that compliance activities were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with trade measurement field audit activity largely suspended in mid-March 2020. At odds with the three stage return to the field for trade measurement inspectors that commenced in June 2020, with all jurisdictions (except for Victoria) commencing stage 3 field activities in November 202040, DISR continued to report that ‘trade measurement field audit activity was suspended or restricted for significant periods in many parts of the country’ during 2020–21 and 2021–22.

Monitoring compliance of targeted industries

3.15 The ANAO examined the extent to which the audits conducted aligned with the compliance programs as set out in the National Compliance Plans and whether the audits focussed on those industries identified as being higher-risk.

3.16 As shown in Table 3.2, DISR did not meet the target number of trader audits under its concentrated national audit and compliance confidence programs41, with 41 per cent achieved in 2021–22. In aggregate, the audits under these targeted programs represented 27 per cent of planned audits and constituted 33 per cent of actual trader audits conducted over the three-year period.42 That is, the shortfall in audits conducted under the targeted programs was broadly similar to the shortfall across the overall audit program.

Table 3.2: Target vs actual audits conducted under targeted programs

|

Year |

Target |

Actual |

Percentage of target achieved |

|

2019–20 |

3050 |

2575 |

84% |

|

2020–21 |

2300 |

1751 |

76% |

|

2021–22 |

2090 |

857 |

41% |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

Monitoring compliance at the trader-level

3.17 DISR introduced the use of trader-level risk assessments to inform trader selection in its 2022–23 ‘Tare It’ program (see paragraphs 2.58–2.60 for further details on DISR’s trader-level risk assessments).43 The first concentrated audit was undertaken the week commencing 17 October 2022 and focussed on fruit and vegetable retailers. The program plan stated that the national target was for 500 trader audits to be conducted during that week. Based on TMARS data, this target was not met with 358 trader audits (72 per cent) being completed.

3.18 Trade measurement inspectors were provided a list of traders for their region and advised that ‘inspections should prioritise traders with the highest risk category (Very High to Low)’. No other advice was provided to inspectors as to what proportion of traders should be selected for audit under the different risk categories.