Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Torres Strait Regional Authority — Service Delivery

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Torres Strait Regional Authority’s administration of its program and service delivery functions.

Summary

Introduction

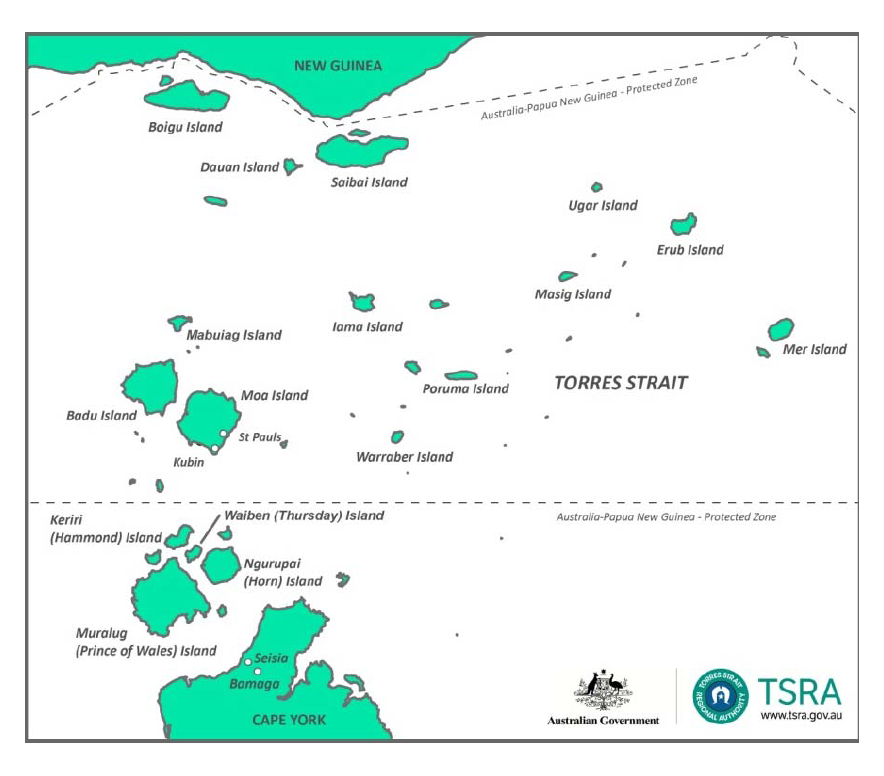

1. The Torres Strait region stretches 150 km from Cape York Peninsula in Queensland to the Australia/Papua New Guinea border. The region covers approximately 42 000 kms² and at its northernmost point is approximately 4 kms from Papua New Guinea and 74 kms from Indonesia. In 2011, there were estimated to be 6990 Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people in the region, equating to 78.8 per cent of the population.1 The population is spread across 18 island communities, and two Torres Strait Islander communities of the Northern Peninsula area of Cape York (Bamaga and Seisia).2

2. The people of the Torres Strait live in an area that is remote from the rest of Australia and in communities that are physically separated from one another. Travel between the island communities is by boat or barge, light plane or helicopter, which provides additional challenges for the effective delivery of government services.3 A map of the Torres Strait Region is shown in Figure S.1.

3. The Torres Strait Treaty defines the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea and establishes the Torres Strait Protected Zone. The protected zone provides for shared fishing rights and for traditional inhabitants to travel across the border without a passport. The region is also a special quarantine zone, which restricts the southward movement of plant and animal products and soil. A number of Australian government agencies are involved in the complex border arrangements to manage health and biosecurity risks, such as exotic pests and diseases being transmitted to the region and onto mainland Australia, as well as increasing demand on local services, in particular health services. More recently, asylum seekers have entered Australia through the Torres Strait region. Other Australian and state government agencies operate to deliver services to residents of the region which increases the importance of having effective arrangements in place to coordinate service delivery and obtain community perspectives on service performance.

Figure S.1: Torres Strait region

Source: Torres Strait Regional Authority.4

The TSRA and its functions

4. A Commonwealth statutory authority, the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) was established on 1 July 19945 to provide greater autonomy to the Torres Strait and to achieve a better quality of life for the people living in the region.6 The key functions of the TSRA are outlined in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth)(ATSI Act). These include to:

- recognise and maintain the special and unique Ailan Kastom7 of Torres Strait Islanders living in the Torres Strait Area;

- formulate and implement programs for Torres Strait Islanders, and Aboriginal persons, living in the Torres Strait area;

- monitor the effectiveness of programs for Torres Strait Islanders, and Aboriginal persons, living in the Torres Strait area, including programs conducted by other bodies;

- develop policy proposals to meet national, state and regional needs and priorities of Torres Strait Islanders, and Aboriginal persons, living in the Torres Strait area;

- assist, advise and cooperate with Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal communities, organisations and individuals at national, state, territory and regional levels; and

- advise the Minister on: matters relating to Torres Strait Islander affairs, and Aboriginal affairs, in the Torres Strait area, including the administration of legislation; and the coordination of the activities of other Commonwealth bodies that affect Torres Strait Islanders, or Aboriginal persons, living in the Torres Strait area.8

5. In 2008, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to six national targets to address the disadvantage faced by Indigenous Australians. Known as the Closing the Gap targets, these are set out in the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA) and include: reducing the life expectancy gap within a generation; halving mortality rates between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous children under five within a decade; halving the gap in reading, writing and numeracy achievement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students within a decade; and halving the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous Australians within a decade. In addition, a key principle of COAG’s approach to implementing NIRA is collaboration between and within government at all levels and their agencies to effectively coordinate programs and services. The TSRA has aligned its planning approaches to reflect the broader goals of NIRA.

6. Against this background, reducing the level of disadvantage experienced in the Torres Strait is a key focus of the TSRA. As described in the 2013–14 Portfolio Budget Statements for the Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs portfolio, the Australian Government’s agreed outcome for the TSRA is:

Progress towards closing the gap for Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people living in the Torres Strait Region through development planning, coordination, sustainable resource management and preservation and promotion of Indigenous culture.9

7. The TSRA is also required by its enabling legislation to formulate a Torres Strait Development Plan from to time to time, which is to cover a period of at least three years and not more than five years.10 The development plan covering the period 2009 to 2013 is aligned to the Closing the Gap targets and associated building blocks.11The development plan describes the following TSRA programs, which are the means to implement the plan:

- economic development;

- culture, art and heritage;

- native title;

- environmental management;

- governance and leadership;

- healthy communities; and

- safe communities.

The TSRA is currently preparing a new development plan for the period 2014‑18.

Legislative and administrative arrangements for the TSRA

8. The TSRA is governed by the ATSI Act12 and has a board made up of 20 elected members. The Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal community in the region directly elects board members for a term of four years.13 The TSRA’s administration is headed by a Chief Executive Officer (CEO). In June 2013, the TSRA had 137 staff employed under the Public Service Act 1999 (Cth) (PS Act), to carry out its functions.

9. As a result of administrative changes made following the 2013 Federal election, the TSRA was transferred from the Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs portfolio to the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) portfolio. In 2012–13, TSRA’s direct appropriation from government was $45.7 million. In 2013–14, the appropriation to the TSRA is $49.6 million.14

Service delivery in the Torres Strait region

10. A range of Australian and state government agencies deliver the majority of services to the residents of the region. For example, the Queensland State Government is responsible for the delivery of local services, including health, housing and education and the Australian government services include income support payments, Medicare and family assistance. The TSRA seeks to liaise and coordinate with these agencies to assist in better targeting service delivery and identifying service delivery gaps. The TSRA has direct responsibility for delivering its own services such as environmental planning, administering fish licensing revenue, the Gab Titui Cultural Centre, leadership and arts development as well as the provision of home and business loans. In addition, the TSRA receives grant funding to deliver activities, such as the Indigenous ranger program funded through the Australian Government Working on Country Program.

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Torres Strait Regional Authority’s administration of its program and service delivery functions.

12. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO’s high-level criteria included assessing the TSRA’s arrangements to identify service delivery needs, coordinate and deliver services as well as the arrangements to monitor and report on performance.

Overall conclusion

13. The remoteness of the Torres Strait region and the dispersed nature of its population across 20 small, mostly island-based, communities provides challenges for the effective delivery of government services. The TSRA’s functions include formulating and implementing programs for the Indigenous people of the region, but as a small agency it does not deliver all the services required to meet the region’s needs and other agencies have an important role to play in service delivery. To fulfil its task to improve the wellbeing of the Indigenous people of the region, effective coordination and monitoring of services delivered by other government agencies is a key aspect of the TSRA’s operations. There are limitations on the extent to which the TSRA can achieve outcomes on its own and to be successful in achieving the full range of its responsibilities, the TSRA relies on the cooperation of other agencies.

14. Overall, the TSRA has effective management arrangements in place for delivering and monitoring its own programs, with the TSRA’s service delivery approach aligned to identified needs and the Australian Government’s broader policies to address Indigenous disadvantage. However, a structured coordination and monitoring role in relation to programs delivered by other government agencies is not yet in place. The TSRA, working with the Queensland Government, has successfully delivered some of the foundation elements of the proposed integrated service delivery framework, such as the mapping of available services and service gaps. The framework and associated action plans, including accountability and monitoring arrangements, however, have not been endorsed by the respective governments.

15. The TSRA formulated the Torres Strait Development Plan 2009–2013 aligning it with both the regional plan (a community-based, joint planning exercise) and the Closing the Gap in Indigenous disadvantage targets contained in the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA) . The TSRA formally consults with communities in the region. However, as a service delivery agency, the TSRA has not developed formal approaches to assess the satisfaction levels of the communities it services or formalised its client feedback and complaints process. The information gained from documenting and analysing feedback would provide useful qualitative performance information to assist in improving service delivery to the communities.

16. The TSRA provides detailed information on its activities in its annual report to Parliament. The annual report uses the same key performance indicators (KPIs) developed for the Torres Strait Development Plan and also presents data on various aspects of Indigenous disadvantage. However, the development plan KPIs are focussed on measuring the delivery of aspects of TSRA’s programs, rather than achievement of outcomes. Moreover, the data presented on Indigenous disadvantage does not closely align with the NIRA targets and the absence of trend data either in the annual report or the development plan does not facilitate the assessment of progress over time. Overall, the TSRA does not have a strong measurement basis to assess the impact of the its activities on reducing disadvantage in the region.

17. The ANAO has made two recommendations—one aimed at strengthening the TSRA’s coordination and monitoring role in the region and the other for the TSRA to undertake client satisfaction surveys and implement a formal feedback and complaints process.

Key findings by chapter

Arrangements to Support Coordination and Service Delivery (Chapter 2)

18. In line with the Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) emphasis on better coordination for Indigenous services, the TSRA has tried various approaches to coordinate services in the Torres Strait region, including through strategic partnerships, memoranda of understanding, funding agreements and formal and informal networks. As at December 2013, arrangements to monitor services delivered by other agencies do not exist. Effective coordination arrangements between the Australian, Queensland and local governments providing services in the region would provide the basis for structured monitoring arrangements and would better enable the TSRA to fulfill this function under the Act. With this aim in mind, the TSRA has worked since 2009 to develop the Integrated Service Delivery Project (ISD).

19. The ISD framework and action plans were scheduled to be finalised and implemented in July 2010. The framework and action plan are high-level agreements designed for sign off by the Australian, Queensland and local governments. However, delays have repeatedly stalled the agreement process. In this context, the ISD was not ready at the original target date of July 2010 as it was recognised that service mapping needed to be undertaken to underpin the ISD Action Plan. Consultations with communities during the 2008 regional planning exercise formed the background to the identification of service gaps, however, further work was needed to validate the service gaps and map available services. Service mapping was subsequently finalised in 2012, with the publication of community booklets, which listed the available services and provided a progress report on service gaps. While there has been active engagement and collaboration, particularly with the three local councils and the Queensland State Government in the service mapping exercise, the ISD framework and action plans are yet to be signed.

20. The TSRA engages in community consultation on a face-to-face basis and seeks feedback from communities. However, it does not periodically seek feedback to gauge satisfaction levels. In addition, the TSRA advised that it responds to complaints and suggestions, but does not have an internal process to capture complaints information, undertake analysis of the feedback and complaints received or monitor its own responsiveness. By measuring the level of satisfaction in these periodic surveys, the TSRA could assess whether its goal of improving the wellbeing of the communities is perceived as being achieved. A formal feedback and complaints process would enable the TSRA to demonstrate that it is addressing the key elements necessary for effective service delivery by understanding what the agency does well and identify where improvements could be made. Results of client surveys and analysis of feedback and complaints also provide useful qualitative performance information to inform service delivery.

Development and Implementation of Services (Chapter 3)

21. The ATSI Act requires the TSRA to formulate a Torres Strait Development Plan. The TSRA has consistently met this requirement and has produced development plans since 1994. The TSRA has aligned the current Torres Strait Development Plan 2009–2013 (development plan) with the Torres Strait & Northern Peninsula Area Regional Plan—Planning for our future: 2009 to 2029 (regional plan) and also the Closing the Gap building blocks. Although the development plan demonstrates strong linkages to the regional plan and the building blocks, and describes activities undertaken by the TSRA, it could be improved by including information on the prevailing level of disadvantage experienced in the region and the projected achievements of the TSRA to improve the wellbeing of the Indigenous residents of the region over of the life of the plan.

Performance Measurement and Reporting (Chapter 4)

22. The TSRA reviews its performance against the development plan annually in line with legislative requirements, with more regular monitoring on its activities at internal forums and to the TSRA board. However, no formal evaluation is undertaken against the cumulative achievement of the TSRA over the four-year time span of the development plan. Such evaluation work would assist the TSRA to determine whether programs have been successful in meeting their objectives and to inform development of subsequent plans.

23. The TSRA’s key performance indicators (KPIs) described in the Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and the annual report to Parliament are a subset of the development plan KPIs. While these are generally appropriate for the TSRA’s board and administration to monitor TSRA’s program activity, the Outcomes and Programs Framework, which guides reporting to Parliament, has a more strategic outcome focus. Using the same KPIs provides a clear connection between the development plan, the PBS and the annual report, however, a consequence is that the TSRA’s KPIs do not focus on measuring progress against closing the gap in the region, which is the TSRA’s agreed outcome.

24. To provide an indication of progress toward closing the gap in the region, the TSRA included various statistical data in its 2011–12 and 2012–13 annual reports. This reporting used recent census data for the Torres Strait region from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), such as population, employment, education, income and housing data. While this data provides some reflection on aspects of Indigenous disadvantage in the region, it does not align with any of the agreed Closing the Gap targets. Sourcing alternative data where possible, and including additional narrative information, would assist in presenting a clearer picture of progress made toward closing the gap in the Torres Strait region. Moreover, the TSRA only reports the most recent data available and does not conduct trend analysis across years. Trend analysis would assist in providing an assessment of achievement over time.

Summary of agency response

25. The Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) considers the audit report from the ANAO to be a balanced report. The report provides for two recommendations, and acknowledges that the TSRA has effective management arrangements in place for delivering and monitoring its own programs, with the TSRA's service delivery aligned to identified needs and the Australian Government's broader policies to address indigenous disadvantage. The report also provides the opportunity for the TSRA to strengthen its position as the leading Commonwealth Agency in the Torres Strait Region on Indigenous matters.

26. The TSRA agrees with recommendation one and will build on its existing informal arrangements with relevant service delivery agencies in the Torres Strait region and establish suitable formal arrangements.

27. The TSRA agrees with recommendation two, and will adopt the ANAO's recommendation to undertake periodic client satisfaction surveys and implement a feedback and complaints process. In addition, the TSRA will continue to engage with the Communities in the Torres Strait region to seek feedback on satisfaction levels with its services.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.31 |

To assist the coordination and monitoring of services in the absence of an integrated service delivery framework, the ANAO recommends that the TSRA establishes suitable formal arrangements with relevant service delivery agencies to share appropriate program information. TSRA’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 2.39 |

To improve its client service delivery, the ANAO recommends that the TSRA undertakes periodic client satisfaction surveys to gauge the level of satisfaction with TSRA’s services, and implements a feedback and complaints process. TSRA’s response: Agreed. |

Footnotes

[1] Statistics based on figures for regional profiles published by the Queensland Government Statistician. Total population for the region is estimated to be 8751.

[2] The communities at Seisia and Bamaga are made up of Saibai Islanders who were relocated from their island after severe flooding in the 1950s.

[3] Seisia and Bamaga on Cape York are accessible by road for part of the year. Two communities, Ugar and Dauan, do not have airports which restricts the type of air travel to helicopters.

[4] The map is not to scale.

[5] The predecessor to the TSRA was the Torres Strait Regional Council, a representative council, which was part of the then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) arrangements. The TSRA was separated from ATSIC in 1994 and continued under the same legislation until the abolition of ATSIC in 2004. In 2005, the TSRA was reestablished under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth).

[6] Torres Strait Regional Authority, Annual Report to Parliament 1994–95, TSRA, Canberra, 1995, p. 16.

[7] Ailan Kastom is defined in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Act 2005 (Cth) as the body of customs, traditions, observances and beliefs of some or all of the Torres Strait Islanders living in the Torres Strait area, and includes any such customs, traditions, observances and beliefs relating to particular persons, areas, objects or relationships.

[8] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth) s 142A.

[9] Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Portfolio, Portfolio Budget Statements 2012–13, Budget Related Paper No. 1.7, Canberra, 2012, p. 299.

[10] The TSRA have established a four year period for its development plans to align with the period of tenure for TSRA board members.

[11] To achieve the Closing the Gap targets, COAG identified seven action areas or ‘building blocks’, which are linked to the targets. The seven action areas are: early childhood, schooling, health, economic participation, healthy homes, safe communities and governance and leadership.

[12] The TSRA is also subject to the requirements of the Commonwealth Companies and Authorities Act 1997, which is to be replaced by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 on 1 July 2014.

[13] Under the previous arrangements, councilors elected in the local government elections were automatically appointed to the TSRA board. Commencing in 2012, the Indigenous community directly elected board members. The elections were undertaken by the Australian Electoral Commission.

[14] Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Portfolio, Portfolio Budget Statements 2012–13, Budget Related Paper No. 1.7, Canberra, 2012, p. 297 and Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Portfolio, Portfolio Budget Statements 2013–14, Budget Related Paper No. 1.6, Canberra, 2013 p. 285.