Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Third Follow-up Audit into the Australian Electoral Commission's Preparation for and Conduct of Federal Elections

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the Australian Electoral Commission’s implementation of those recommendations relating to improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll and other matters from Audit Report No.28 2009–10 that have not previously been followed-up by the ANAO.

Summary and recommendations

1. During the conduct of the 2013 federal election, 1370 Western Australian (WA) Senate ballot papers were lost. This resulted in the election of six WA Senators being voided and a new election for WA Senators being held in April 2014. Following the loss of votes, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (the Committee) wrote to the Auditor-General in February 2014 seeking a performance audit focusing on the adequacy of the Australian Electoral Commission’s (AEC) implementation of recommendations arising from earlier Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) audit reports.

2. In response, the Auditor-General decided to conduct three related performance audits covering the recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10. The first two ANAO follow-up audit reports found that the AEC had not adequately and effectively implemented the earlier ANAO recommendations that were being followed-up. The reports concluded that, to protect the integrity of Australia’s electoral system and rebuild confidence in the AEC, it is important that the AEC’s governance arrangements emphasise continuous improvement and provide assurance that the action taken in response to agreed recommendations effectively addresses the matters that led to recommendations being made.

Audit approach

3. The objective of this audit was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of those recommendations relating to improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll and other matters from Audit Report No.28 2009–10 that have not previously been followed-up by the ANAO.

4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO examined the AEC’s progress in implementing recommendations 1, 2, 3, 4, 8(a) and 9 in the five years since Audit Report No.29 2009–10 was tabled.

Overall conclusion

5. The actions taken by the AEC prior to the 2013 election in response to previously agreed ANAO recommendations have not adequately and effectively addressed the matters that led to recommendations being made. The findings of this audit are consistent with the findings of the first two follow-up audits and are in contrast to the advice provided by the AEC to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters’ inquiry in 2014 that all recommendations in Audit Report No.28 2009–10 had been completed by May 2013.1

6. Some useful work had been undertaken in relation to aspects of a number of those recommendations that related to the management of the electoral roll, but there were also some significant gaps in implementation action. In addition, no meaningful action had been taken prior to the 2013 election in relation to those recommendations directed towards more secure reporting of election night counts or the development of comprehensive performance standards for the conduct of elections.

7. Informed by various reviews and inquiries undertaken into the conduct of the 2013 election, the AEC has since commenced an extensive reform programme. The aim of the reform programme is to deliver long-term changes in culture and improvements in the AEC’s policies and procedures. Some changes are expected to be in place prior to the next federal election, but full implementation of measures currently being planned or actioned is not expected until the following federal election. These timeframes reflect the extensive body of reform work that is being undertaken in parallel with the AEC’s normal business-as-usual activities.

8. The ANAO plans to undertake a follow-up audit following the next federal election to examine the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of the ten recommendations made across the three ANAO follow-up audit reports. This action is consistent with the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters’ interest in the AEC’s implementation of audit recommendations, within the context of the AEC’s broader reform programme.

Supporting findings

Figure S.1: The AEC’s implementation of earlier ANAO recommendations

|

In Audit Report No.28 2009-10, the ANAO recommended that the AEC1: |

Findings |

Progress |

|

Develop improved governance arrangements for the management of elector’s personal information (Recommendation 1(a)). |

While significant progress had not been made in improving governance arrangements relating to the management of electors’ personal information, tasks had been undertaken that addressed specific elements of the recommendation. |

Partially implemented |

|

Assess the extent to which the use of electoral roll information by non-government entities adversely impacts on the willingness of Australians to enrol to vote (Recommendation 1(b)). |

Not implemented prior to the 2013 election. Research on the impact of non-government entities’ use of electoral roll information on enrolment was underway at the time of this follow-up audit. |

Partially implemented |

|

Establish a sound basis for costing the maintenance and review of the electoral rolls and the production of state and territory roll products (Recommendation 2). |

AEC has established a basis for costing state and territory roll-related services using historical expenditure, but further work is required to have all state and territory electoral commissions agree to the new national per elector contribution rate for the provision of roll-related services, and to have the relevant agreements updated to reflect both the rate and the work the AEC actually undertakes. |

Partially implemented |

|

Expand and enhance the sampling methodology for undertaking habitation reviews as part of its roll-management activities (Recommendation 3). |

Changes to Sample Audit Fieldwork were inconsistent with the intent of the earlier recommendation. Rather than being expanded to include those locations where issues concerning roll accuracy and completeness are most prevalent, coverage has contracted and continued to focus on the least costly locations to visit. |

Not implemented |

|

Formulate a program of research into elector enrolments and enrolment trends, with a view to identifying potential electors missing from the roll and the reasons why they may not be enrolling (Recommendation 4). |

Some worthwhile research into enrolment has been undertaken, but the AEC would benefit from developing a rolling strategic research programme. |

Implemented |

|

Develop strategies to mitigate the risk to the credibility of election results posed by the current practices for the reporting of polling place election-night counts (Recommendation 8 (a)). |

Not implemented prior to the 2013 election. A process for verifying the credibility of election night results was selected for the Canning By-Election, and future general elections. |

Partially implemented |

|

Develop comprehensive performance standards for the conduct of elections and, following the conduct of each election, report to the Parliament on the extent to which these standards have been met (Recommendation 9). |

Not implemented prior to the 2013 election. An election service delivery plan was prepared for the Canning By-Election, with the AEC advising of its intention to make this plan available on its website and report against the standards in the plan following the election event. |

Partially implemented |

Note 1: The recommendations from Audit Report No.28 have been paraphrased.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.29 |

To provide transparent information on, and drive improvement in, enrolment, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Electoral Commission develop, publish and report against performance targets related to the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.25 |

To provide information on the accuracy of the electoral roll and enable reporting against performance targets, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Electoral Commission implement a more reliable method of estimating the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll. |

Summary of entity response

The proposed audit report was provided to the AEC. The AEC provided formal comments on the proposed report and these are summarised below, with the full response included at Appendix 1:

In response to the Third Follow-up Audit into The Australian Electoral Commission’s Preparation for and Conduct of Federal Elections, the AEC unreservedly accepts the first Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) recommendation (regarding publication of publication of enrolment performance targets); and agrees with qualifications with the second recommendation (regarding estimation of the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll).

Since the original ANAO audit the AEC has made significant progress in addressing the fundamental challenge of enrolment participation via a range of strategies including implementation of new legislative measures such as direct enrolment and update; introduction of a fully digital online enrolment service, and ongoing adjustments to the Roll Management program. Among other outcomes these measures have reduced the number of missing electors in both real and absolute terms from 1.5 million to 1.2 million.

The AEC is committed to ongoing improvement, and the implementation of ANAO recommendations, in relation to both elections and roll management activities, is a fundamental aspect of this process as we prepare for the next federal electoral event.

1. Background

1.1 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is responsible for conducting federal elections and referendums, maintaining the Commonwealth electoral roll and administering political funding and disclosure requirements in accordance with the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The AEC also provides a range of electoral information and education programmes in Australia as well as in support of Australia’s international interests. Its stated outcome is to:

Maintain an impartial and independent electoral system for eligible voters through active electoral roll management, efficient delivery of polling services, and targeted education and public awareness programs.2

1.2 The AEC employed around 780 ongoing staff as at 30 June 2015 and operates through a three tier structure of: a national office in Canberra; state and territory offices; and divisional offices (both standalone and co-located in larger work units) responsible for electoral administration across the 150 divisions. The AEC also has contractual arrangements with all state and territory electoral commissions to provide services (for example, processing enrolment forms and providing roll products) and to share enrolment information.

1.3 In April 2010, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) tabled a performance audit report on the AEC’s preparation for, and conduct of, the 2007 federal election.3 The ANAO made nine recommendations relating to the management of the electoral roll and the conduct of elections, including providing greater physical security over the transport and security of completed ballot papers.

1.4 In this latter respect, 1370 Western Australian (WA) Senate ballot papers were lost in the 2013 federal election. The loss of those ballot papers resulted in the election of six WA Senators being voided and a new election for WA Senators being held in April 2014. The Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (the Committee) subsequently wrote to the Auditor-General in February 2014 seeking a performance audit focusing on the adequacy of the AEC’s implementation of recommendations from the ANAO’s audit reports.

1.5 In response, the Auditor-General decided to conduct three related performance audits covering the recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10. Two of the three audits have been tabled:

- Audit Report No.31 2013–14, which assessed the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of the recommendation relating to physical security over the transport and storage of completed ballot papers4 (tabled in May 2014); and

- Audit Report No.4 2014–15, which assessed the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of the recommendations relating to workforce planning, the suitability and accessibility of polling booths and fresh scrutiny premises and ballot paper transport (tabled in November 2014).

1.6 These audit reports observed that, to protect the integrity of Australia’s electoral system and rebuild confidence in the AEC, it is important that the AEC’s governance arrangements:

- emphasise continuous improvement; and

- provide assurance that the action taken in response to the agreed recommendations effectively addresses the matters that led to recommendations being made.

1.7 The Committee also completed an inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 federal election and related matters in April 2015. Relevant commentary and recommendations arising from this inquiry have been taken into consideration in this third ANAO follow-up audit.

1.8 Figure 1.1 provides a summary of recent electoral events, reviews into the AEC and advice from the AEC to its audit committee and the Committee.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of reviews into, and advice from, the AEC

Note 1: Joint Standing Committee of Electoral Matters (JSCEM).

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.9 In January 2014, the AEC commenced a reform programme comprising the following elements:

- accept the recommendations of the Keelty Report (and subsequently, the reports by the ANAO)5;

- focus on short-term measures to immediately implement those recommendations at upcoming federal electoral events (see the events listed in Figure 1.1 for February 2014 and April 2014); and

- develop a strategy for deeper reform to ensure and demonstrate integrity in all aspects of election and non-election related programmes and services, including a fundamental overhaul of the AEC’s policies and procedures to restore confidence in the electoral process.

1.10 The reform programme aims to deliver long-term changes in the AEC’s culture and improvements in, for example: election planning and preparation; recruitment, training and development of permanent and temporary staff; and procurement processes to enhance compliance and quality assurance. Individual reforms are to be progressively delivered throughout 2015 and 2016, with the groundwork for these reforms involving planning, research, design, consultation and procurement processes.

Audit approach

1.11 The objective of this audit was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the AEC’s implementation of those recommendations relating to improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll and other matters from Audit Report No.28 2009–10 that have not previously been followed-up by the ANAO. In this respect, Audit Report No.28 2009–10 had concluded that the most significant long-term issue facing the AEC remains the state of the electoral roll with the enrolment rate at the time of the 2007 election well below the target of 95 per cent of the estimated eligible population, with an estimated 1.1 million eligible electors missing from the rolls on polling day.

1.12 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO examined whether the AEC had:

- improved governance arrangements relating to electors’ personal information and assessed the extent to which use of electoral roll information by non-government entities may adversely impact on the willingness of Australians to enrol to vote (Recommendation No. 1);

- established a sound basis for costing the maintenance and review of the electoral rolls and other roll products (Recommendation No. 2);

- expanded and enhanced the sampling methodology for undertaking habitation reviews6 as part of its roll review activities (Recommendation No. 3);

- better targeted its efforts to improve the electoral roll through a programme of research into elector enrolments, enrolment trends and electors missing from the roll (Recommendation No. 4);

- developed strategies to mitigate the risk to the credibility of election results posed by the current practices for reporting of election-night counts (Recommendation No. 8(a)); and

- developed and reported on comprehensive performance standards for the conduct of elections (Recommendation No. 9).

1.13 The methodology employed for the audit involved: examining the AEC’s documentation, including relevant procedure manuals, reports, briefing materials and files; and interviewing the AEC’s staff.

1.14 Input was also obtained from the:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) on the advice that it has provided to the AEC in regards to its Sample Audit Fieldwork (SAF) programme;

- Department of Finance on funding arrangements for the AEC and the preparation of the Government’s response to the recommendations made as a result of the Committee’s inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 federal election and related matters; and

- Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) and New South Wales Electoral Commission (NSWEC) on the AEC’s maintenance and review of the electoral roll, provision of electoral roll services and management of the divergence in enrolment records between federal and state and territory electoral rolls.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $402 000.

2. Have research and process changes achieved better enrolment outcomes?

Areas examined

Compulsory enrolment requires every eligible person to participate in elections. In Audit Report No.28 2009–10, the ANAO recommended that the AEC:

- assess the extent to which the use of electoral roll information by non-government entities adversely impacts on the willingness of Australians to enrol to vote (Recommendation No. 1(b)); and

- formulate a research programme into enrolment, with a view to identifying potential electors missing from the roll and the reasons why they may not be enrolling (Recommendation No. 4).

In this follow-up audit, the ANAO considered how research that was undertaken and changes in enrolment processes affected the integrity and completeness of the electoral roll.

Conclusion

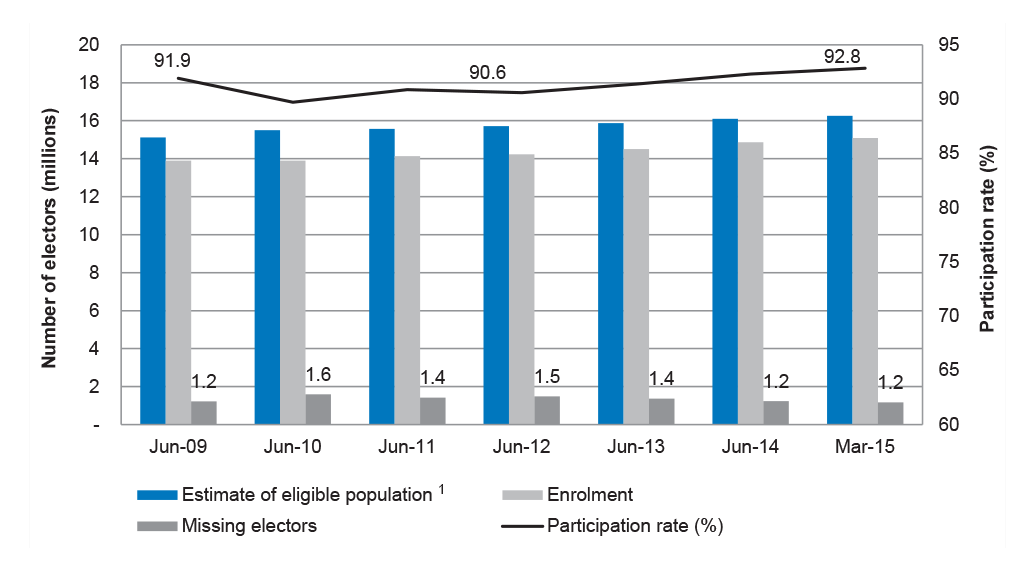

Through the research activities undertaken and the changes in process implemented by the AEC, the enrolment rate has increased from 91.9 per cent in 2009 to 92.8 per cent in 2015. There is, however, room for further improvement. Specifically, the AEC would benefit from:

- developing a rolling strategic research programme that integrates research activities with enrolment stimulation and other public engagement activities to produce better enrolment outcomes; and

- increasing the transparency in relation to roll management activities by reporting on the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll.

Recommendations

The ANAO made one recommendation related to reporting on the accuracy and completeness of the roll.

Has research been undertaken on enrolment?

The AEC has undertaken worthwhile research on enrolment and enrolment trends in response to Recommendation No. 4 in Audit Report No.28 2009–10. The AEC had not, however, taken sufficient action on Recommendation No. 1(b) prior to the 2013 election, with research on the impact of non-government entities’ use of electoral roll information on enrolments currently underway.

While progress has been made by the AEC in relation to the research recommendations, there remains room for improvement. Specifically, the AEC would benefit from developing a rolling strategic research programme that integrates research activities with enrolment stimulation and other public engagement activities to produce better enrolment outcomes.

2.1 At the time of the 2007 election, there were 1.1 million electors estimated to be missing from the electoral roll, the enrolment rate had fallen and the data supporting the AEC’s roll stimulation activities did not distinguish whether enrolment outcomes differed across age groups. As a result, Audit Report No.28 2009–10 concluded that improving the enrolment rate was one of the greatest challenges facing the AEC. The ANAO concluded that, given the trends, the AEC would benefit from a programme of research into the key demographic characteristics of people that had not enrolled to vote and their reasons for not enrolling. Such a programme was expected to result in better informed and more focused efforts to improve the enrolment rate (Recommendation No. 4). The ANAO also recommended (Recommendation No. 1(b)) that AEC obtain a better understanding of the effect of third party use of electoral roll information on the willingness of Australians to enrol to vote.

2.2 An important initiative undertaken by the AEC subsequent to the 2007 election was the establishment in 2010 of the Commissioner’s Advisory Board on Electoral Research.7 The Board is made up of members from various universities, a member each from the Australian Parliamentary Library, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the AEC, and a single member representing all state and territory electoral commissions. Its role is to:

- as required, provide the Electoral Commissioner with expert advice on electoral research, including the strategic value of research;

- contribute to the development and progress of a strategic research framework to better inform and support delivery of electoral services and influence electoral policy reform;

- identify key gaps in electoral research; and

- promote and be an ambassador for high quality electoral research.

2.3 Consistent with its Terms of Reference, the Board provided the AEC with five recommended research areas, in priority order, in June 2011. These research areas were: direct enrolment and update; voter turnout; informal voting; political and civics knowledge; and new and social media. The AEC has undertaken work to address the substance of the Board’s recommendations.

2.4 In August 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that the functions of the Board were on hold. In this regard, the AEC reallocated the funds it had previously assigned for Board-related research in Financial Year 2014–15 to addressing the issues that arose in the 2013 federal election. As a result, while AEC continues to undertake research, the Board has not met since late 2012.

2.5 In addition, the AEC is yet to complete research that will address Recommendation No. 1(b) from Audit Report No.28 2009–10. In June 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that research into the impact of non-government entities’ use of electoral roll information on enrolments had commenced—some five years after agreeing to implement the recommendation. According to the AEC’s reform programme plan, this research was to be completed, with changes implemented, in March 2015. This target was not met and completion of this work is now expected in November 2015.

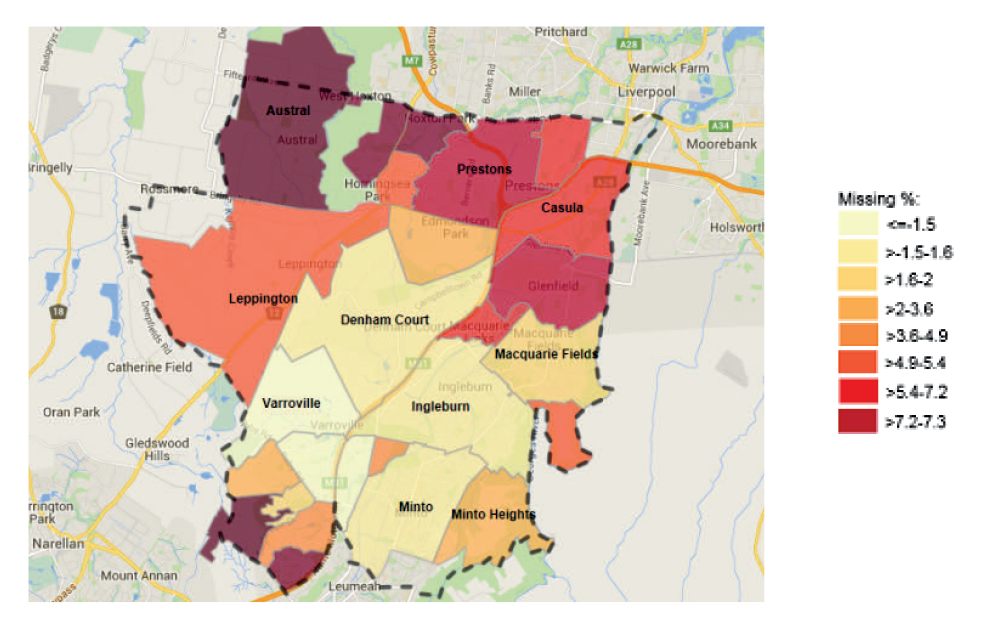

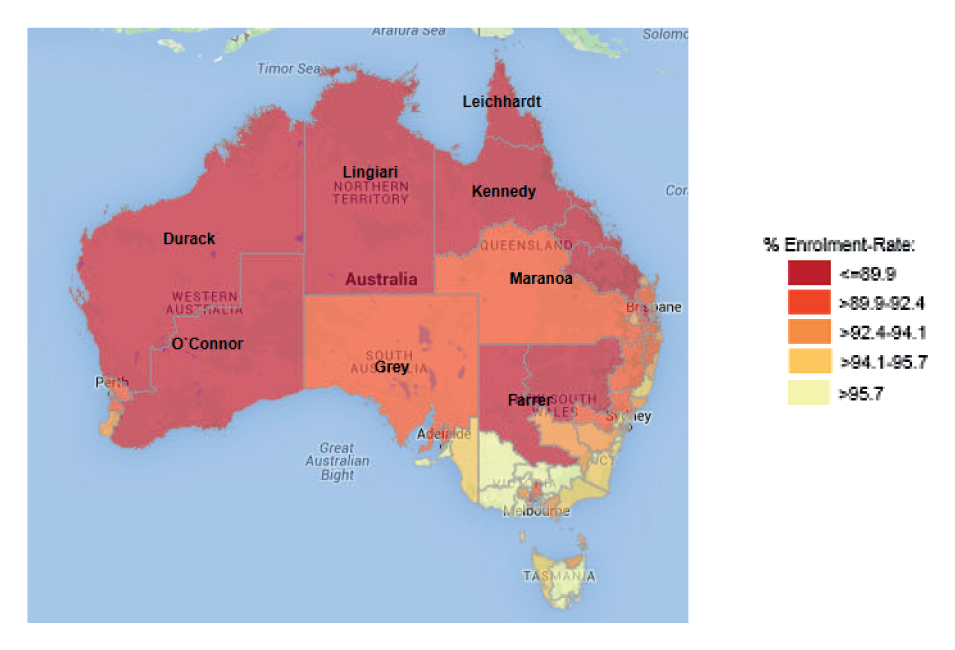

2.6 The AEC has been more active in relation to enrolment research. Specifically, the AEC has undertaken research into enrolment, enrolment trends and missing electors. Since 2010, the AEC has used demographic data to improve its knowledge of the location of missing electors. For example, the AEC used data from the electoral roll and the 2011 Census to develop:

- divisional maps estimating the percentage of the population missing from the roll by suburb in 2010 (see Figure 2.1 for an example); and

- a map of enrolment rates by electorate in 2014 (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.1: Example of the estimated percentage of the population missing from the electoral roll by suburb in the Division of Werriwa, 2010

Source: AEC records.

Figure 2.2: Enrolment rates by electorate, June 2014

Source: AEC records.

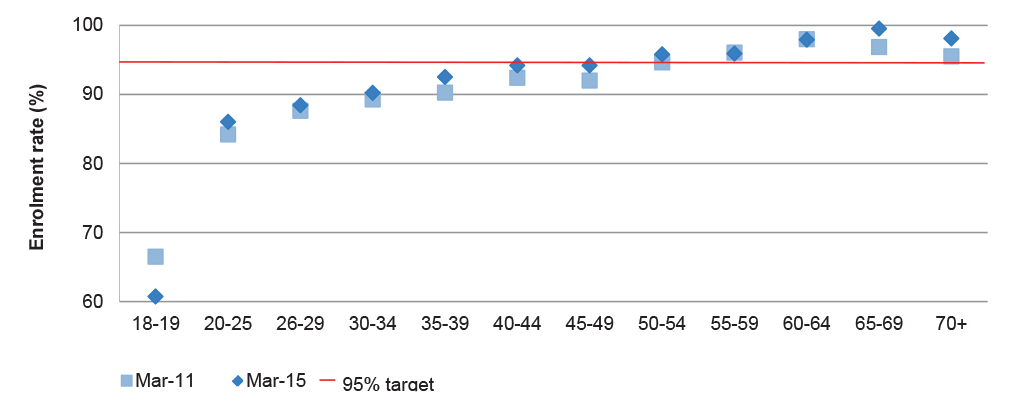

2.7 In addition, the AEC has undertaken analysis to identify groups that have lower than average enrolment rates. For example, in 2014, the AEC identified that:

- 42 per cent of Indigenous persons were not enrolled to vote. In October 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that it does not have definitive data on Indigenous participation (enrolment or voter turnout) and estimates are based on sources that include AEC and ABS data;

- ‘young people have a strong correlation with low enrolment and low turnout’; and

- ‘when further broken down, young males specifically show stronger correlation with low enrolment’.

2.8 This statistical analysis has been used by the AEC to target national public awareness and/or advertising campaigns. However, the AEC has not developed a rolling programme of research into enrolment that:

- focuses on achieving enrolment outcomes;

- is continually refined by the research activities and public awareness activities and/or advertising activities that the AEC has undertaken;

- influences future stimulation and engagement activities; and

- recognises that, where appropriate, trials of innovative enrolment stimulation and public awareness activities in groups that have low enrolment or turnout rates can also be considered to be research activities.

2.9 For example, the Count Me In campaign was a public awareness and advertising campaign that was delivered for the AEC’s Year of Enrolment in 2012 and was primarily targeted at people between the ages of 18 and 39. The campaign included: a postcard; online advertising; a Facebook birthday campaign; and an email to people who agreed to receive emails from the government. The elements of the campaign provided the AEC with an opportunity to evaluate the success of specific activities in achieving an enrolment outcome (a new enrolment or change in enrolment). However, the AEC did not evaluate the success of each campaign in terms of enrolment outcomes. In this respect, the:

- Facebook birthday campaign achieved a click through rate of 0.18%, which was higher than any other medium in the campaign. The average cost per click for this component was $7.16 (total cost of $17 600), but the AEC did not evaluate how many new enrolments resulted from this campaign; and

- email to 50 000 people between the ages of 18-39 who agreed to receive emails from the government achieved a click to open rate of 20.19%. The click to open rate was higher than the average government click to open rate of 8.84%, but the AEC did not measure the number of new enrolments or changes to enrolment that resulted from this email. The cost to open rate for this component was $1.38 (total cost of $22 000).

2.10 These two elements of the campaign were comparatively less expensive than other elements, such as the postcard campaign, which cost $39 per transaction.

2.11 Enrolment stimulation activities using online channels, in particular, provide the AEC with a significant amount of data that could be used to refine future research, enrolment stimulation and public awareness activities. In this respect, the AEC has an opportunity to integrate past, current and future research activities and stimulation and engagement activities to produce better outcomes.

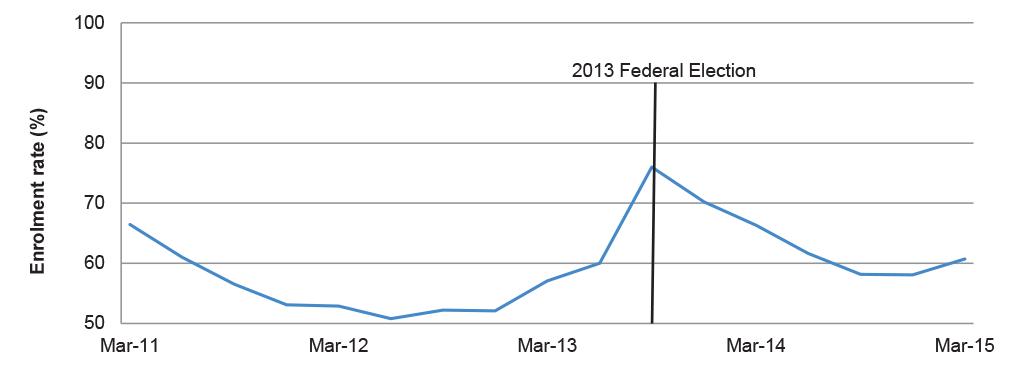

2.12 Against this background, enrolment rates for all age groups, except for the 18 to 19 year age group, have been maintained or improved between 2011 and 2015 (see Figure 2.3). Changes in the enrolment rate for the 18 to 19 year age group have reflected the electoral cycle, as shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.3: Estimated enrolment rates by age group, 2011 to 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

Figure 2.4: Estimated enrolment rates for the 18–19 year age group, 2011 to 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

How has enrolment and update changed since 2010?

Until 2012, enrolment transactions were made via hard-copy forms that were mailed to the AEC by the claimant. The AEC has since:

introduced direct enrolment and update enabling the Electoral Commissioner to:

enrol a person if satisfied that the person is entitled to enrolment, has lived at an address for at least one month and the person is not enrolled; and

update an elector’s enrolled address following the receipt and analysis of reliable and current data sources from outside the AEC that indicate an elector has moved residential address.

launched an online service that allows electors’ to complete and submit enrolment applications via its website.

Direct enrolment and update

2.13 Since the introduction of direct enrolment and update in late 2012, the AEC has compared the electoral roll to recent changes (for example, a change of residential address) evident in the:

- Department of Human Services’ Centrelink data; and

- National Exchange of Vehicle and Driver Information System’s licensing data.

2.14 By comparing these datasets, the AEC can identify eligible electors that are not enrolled or current electors that have moved, but have not updated their residential address.8 In both cases, the AEC writes to the elector to inform them of its intention to create or update an enrolment record. The recipient of the letter has 28 days to advise the AEC if the details are incorrect. If no response is received, the intended enrolment or change to enrolment will be actioned.

2.15 In 2013–14, 816 217 transactions (24.5 per cent of total transactions) were processed using direct enrolment and update. Further, in the 2013 federal election, the AEC’s data indicates that the turnout rate9 for electors whose most recent enrolment was processed via direct enrolment and update was:

- 90 per cent (440 058 votes) for changes to enrolment;

- 66 per cent (43 540 votes) for new enrolments; and

- 62 per cent (33 850 votes) for re-enrolments.

2.16 The overall turnout rate, for the 2013 federal election, was 94 per cent.

Online enrolment service

2.17 In addition to direct enrolment and update, the AEC has attempted to make it easier for people to enrol to vote and maintain their enrolment details by improving its online service. Since 2010, the AEC has provided electors with the option of updating enrolment records via its website. In June 2013, this option was extended to new enrolments.10

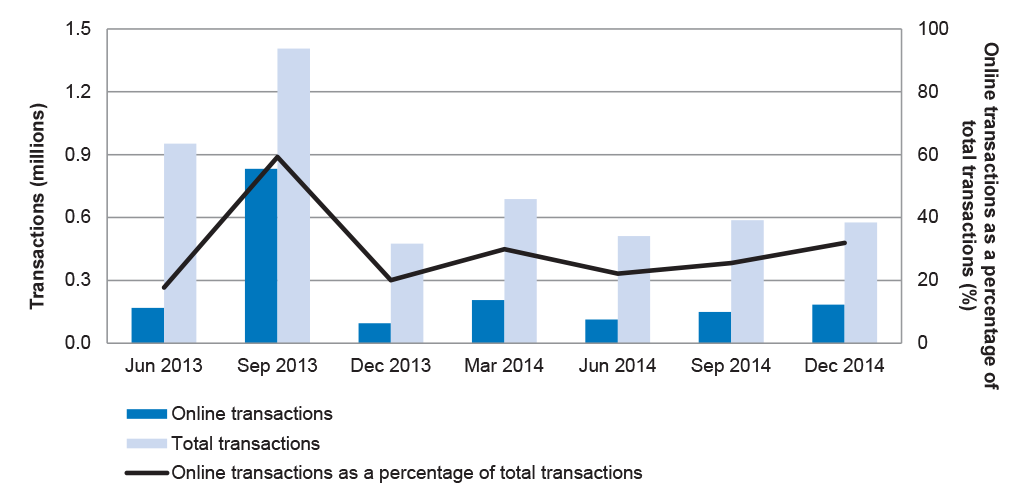

2.18 While use of the online enrolment service has fluctuated on a quarterly basis, at least 20 per cent of enrolment transactions have been processed each quarter through the online channel since September 2013 (see Figure 2.5). In Financial Year 2013–14, for example, 1.2 million enrolment transactions (40 per cent of transactions) were processed via the online enrolment services. The number of transactions in 2013–14 was related to increased transaction activity prior to the 2013 federal election, with 0.8 million transactions processed in the September 2013 quarter alone.

Figure 2.5: Online enrolment transactions by quarter, June 2013 to December 2014

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

What are the key changes in enrolment and enrolment trends since 2010?

The trend of a decline in the number of enrolment transactions per year has reversed since Audit Report No.28 2009–10 tabled. Over the same period, the enrolment rate has increased from 91.9 per cent in 2009 to 92.8 per cent in 2015 and the estimated number of eligible citizens missing from the electoral roll has remained at approximately 1.2 million.

Since the introduction of direct enrolment and update in 2012, there has also been increasing divergence between federal and state electoral rolls.

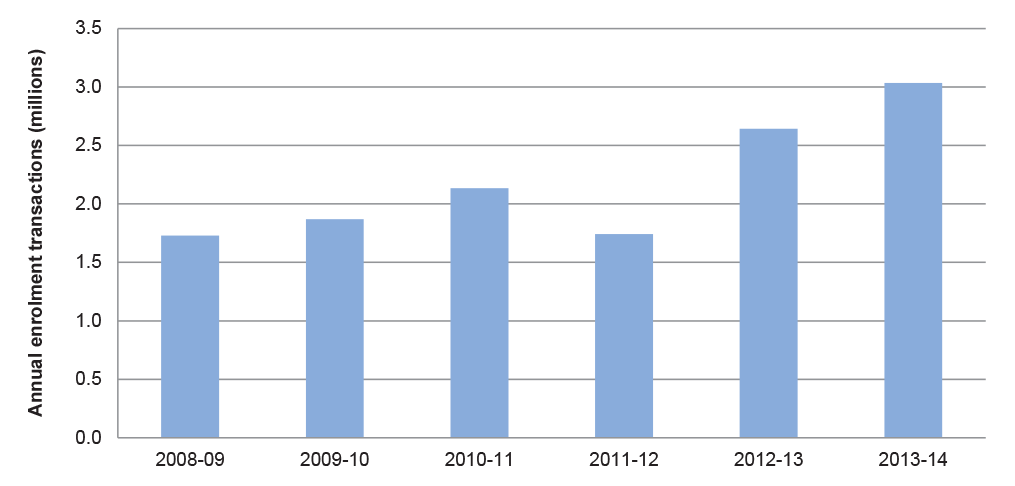

2.19 Audit Report No.28 2009–10 reported a declining trend in the number of enrolment transactions per year. Specifically, the number of enrolment forms processed in 2008–09 had fallen to the lowest level since 1996–97, when 1.2 million enrolment forms were processed. Since 2008–09, this trend has reversed (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6: Enrolment transactions, 2008–09 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

2.20 The significant increase in the number of enrolment transactions has translated to an improvement in the enrolment rate. Specifically, the AEC’s data indicates that between June 2012 (prior to the introduction of direct enrolment and update) and March 2015:

- the estimated eligible population increased by 543 414 people; and

- an additional 859 462 eligible electors were enrolled.

2.21 As shown in Figure 2.7, these changes have resulted in:

- an increase in the estimated enrolment rate, from 90.6 per cent in 2012 to 92.8 per cent in 2015; and

- a reduction in the estimated number of eligible electors missing from the electoral roll, from 9.4 per cent (1.5 million people) in 2012 to 7.2 per cent (1.2 million people) in 2015.

2.22 While AEC’s actions have resulted in a reduction in the number of eligible electors missing from the roll between 2012 and 2015, Audit Report No.28 2009-10 reported that, in 2007, 1.2 million electors were missing from the roll. In this respect, the number of missing electors has not substantially changed since 2007.

Figure 2.7: Enrolment, enrolment rate and the number of missing electors, 2009–2014

Note 1: The eligible population estimate is based on relevant Census data and adjusted for new citizens, as well as the estimated number of people likely to be eligible or ineligible based on being British Subjects, being of an unsound mind, or being located overseas.

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

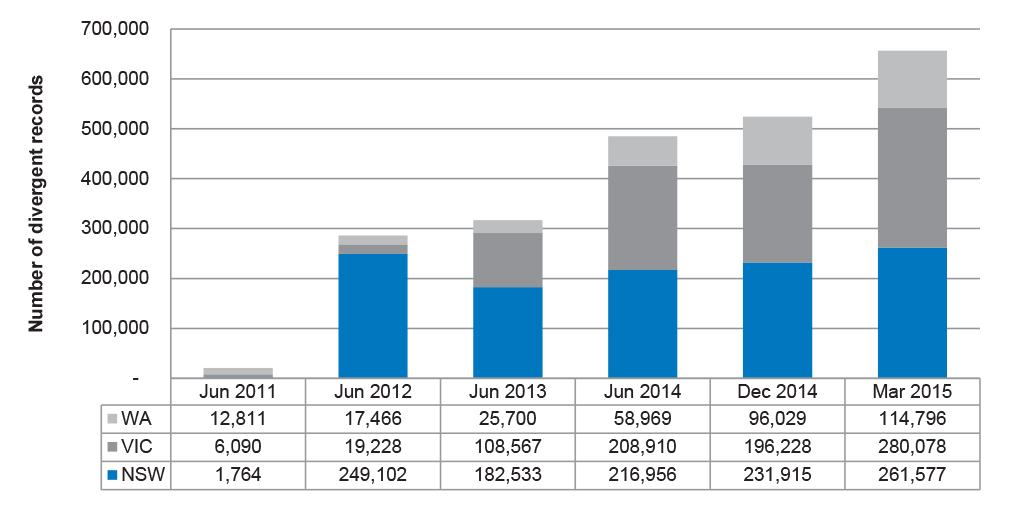

2.23 The introduction of direct enrolment and update by the AEC, NSWEC and VEC between 2010 and 2014 has resulted in an increasing divergence between the various rolls. This divergence has occurred primarily because each entity adds to, and updates, its respective electoral rolls using slightly different approaches. For example, the AEC updates the federal roll using Centrelink and driver licensing data ten times a year, the NSWEC updates the state roll using NSW Roads and Transport registration and licensing data on a weekly basis and the VEC updates the state roll using VicRoads licensing data on a weekly basis. As a result, divergence between the elector information on the federal roll and on the NSW, WA11 and Victorian state rolls has increased, as shown in Figure 2.8.

Figure 2.8: Roll divergence, 2011–2014

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

2.24 The records updated by the NSWEC and the VEC through direct enrolment and update are not currently used by the AEC as an input to its direct enrolment and update. This is because of:

- business rules (for example, the NSWEC and the VEC update the state rolls weekly, while the AEC updates the federal roll 10 times in a calendar year); and

- the AEC’s concerns about the reliability of some data sources used by the NSWEC and the VEC. In August 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that it received numerous complaints when state direct enrolment and update data was used to update the federal electoral roll. These complaints ranged from statements concerning ineligibility to the sourcing of data from vehicle registrations (as opposed to driver’s licence data) and resulted in a high amount of ‘return to sender’ mail. Following a risk assessment, the Electoral Commissioner decided to stop using state direct enrolment and update data as a source for federal direct enrolment and update.

2.25 The increasing number of divergent enrolment records is an emerging area of concern to the AEC, in addition to the estimated 1.2 million missing electors. In August 2015, the AEC advised ANAO that roll divergence is monitored on a quarterly basis and that considerable work is currently underway. This work is scheduled to be completed in September 2015 and includes a comparison of the rolls with external data sources, a review of enrolment business rules and the identification of potential actions to reduce divergence.

What information is provided to the public on the state of the electoral roll?

The transparency of the AEC’s reporting on the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll has reduced over time. The primary indicator for 2015–16 is a qualitative assessment of roll accuracy, which is based on a number of internally published standards that reflect the completeness of the electoral roll and timeliness of enrolment transaction processing. As a result, the current set of internal performance standards does not provide a clear basis to report on whether the AEC has a ‘high level of confidence in accuracy of the electoral roll’.

2.26 Informing the Parliament and the public about enrolment trends, including divergence, can assist in informing debate about beneficial changes such as seeking greater alignment in processes across Australian jurisdictions. However, in recent years, the AEC has reduced its reporting of performance information, as shown in Table 2.1. Specifically, the objective key performance indicators (KPIs) used in the AEC’s 2013–14 Portfolio Budget Statements are now reflected in a single, subjective indicator—‘High level of confidence in accuracy of the electoral roll’. The new indicator is no longer specific or measureable and has a more limited focus on accuracy, rather than completeness and accuracy.

Table 2.1: Comparison of Portfolio Budget Statements indicators, 2013–14 to 2015–16

|

KPI |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

1 |

95% of eligible people on the electoral roll |

Towards 95% of eligible people on the electoral roll |

Not reported |

|

2 |

99.5% of enrolment transaction correctly processed and 99 per cent are processed within three business days |

99.5% of enrolment transactions are processed correctly |

Not reported |

|

3 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

High level of confidence in accuracy of the electoral roll |

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC’s Portfolio Budget Statements.

2.27 Reporting against the AEC’s 2015–16 Portfolio Budget Statements indicator is now supported by internal performance standards, which include:

- progressing the enrolment rate towards 95 per cent of eligible persons;

- 99.5 per cent, or greater, of enrolment transactions are to be processed correctly;

- 95 per cent, or greater, of enrolment transactions are to be processed within five business days, with 99.5 per cent, or greater of enrolment transactions to be processed within 30 business days;

- roll products are to achieve 98 per cent accuracy or greater; and

- roll products are to be delivered on-time at a rate of 98 per cent or greater.

2.28 While the internal performance standards reflect on the completeness of the electoral roll and the timeliness of enrolment transaction processing, the standards are not publicly reported and do not reflect on the accuracy of existing enrolment records. As a consequence, the current set of internal performance standards does not provide a basis for the AEC to report on the ‘level of confidence in accuracy of the electoral roll’. This is contrary to the new Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 arrangements, which require Commonwealth entities to set out, and report against, performance measures that provide meaningful information about what has been achieved.

Recommendation No.1

2.29 To provide transparent information on, and drive improvement in, enrolment, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Electoral Commission develop, publish and report against performance targets related to the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll.

Entity response: Agreed.

2.30 As noted in the report, the AEC has in the past reported on a range of measures as reflected in the Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS). With the advent of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, AEC PBS measures have changed, however the AEC continues to use a range of performance standards to measure the accuracy and completeness of the electoral Roll. Achievements against these performance standards continue to be published in the AEC’s Annual Report. Leveraging the Electoral Integrity Framework, the AEC will further develop these performance standards and publish achievements against these standards on a regular basis alongside a more comprehensive suite of data about the electoral Roll on the AEC website.

3. Were changes in roll management consistent with recommendations?

Areas examined

The AEC’s roll management activities include the processing of enrolment forms, roll review activities and the provision of services to other jurisdictions. In relation to roll management, the ANAO recommended, in Audit Report No.28 2009–10, that the AEC:

- improve governance arrangements relating to electors’ personal information (Recommendation No. 1(a));

- establish a sound basis for costing the maintenance and review of electoral rolls and other roll products (Recommendation No. 2); and

- expand and enhance the sampling methodology for undertaking habitation reviewsA as part of its roll review activities (Recommendation No. 3).

Conclusion

The recommendations related to roll management are at various stages of implementation. Since the earlier audit was tabled, the AEC:

- has addressed specific elements of the recommendation related to information governance arrangements, but has not developed a coherent information management framework;

- has established a basis for costing state and territory roll-related services using historical expenditure, but further work is required to have all state and territory electoral commissions agree to the new national per elector contribution rate for the provision of roll-related services, and to have the relevant agreements updated to reflect both the rate and the work the AEC actually undertakes; and

- continues to exclude rural and remote areas from its Sample Audit Fieldwork and there has been a decrease in the reliability of results. This reduces the level of assurance that is provided on the state of the roll.

Recommendations

The ANAO made one recommendation related to improving the information available relating to the accuracy of the electoral roll.

Note A: Habitation reviews involve the AEC door-knocking residences to check the accuracy of enrolment data for the inhabitants as well as to identify any inhabitants that aren’t on the roll but should be. Sample Audit Fieldwork is now conducted by the AEC in place of habitation reviews.

Have governance arrangements protecting personal information improved?

While significant progress had not been made in improving governance arrangements relating to electors’ personal information, tasks had been undertaken that addressed specific elements of the recommendation.

3.1 At the time of Audit Report No.28 2009–10, electors’ details collected and processed by the AEC were regularly made available to a wide range of third parties. This was occurring without a coherent framework to ensure that the privacy of individuals was maintained and that improper use was discouraged. Recommendation No. 1(a) from that audit report was aimed at addressing this situation. Although the AEC has previously reported that the ANAO recommendation had been implemented, in the course of this follow-up audit the AEC advised the ANAO that a coherent framework had not been developed in response to this recommendation.

Management of personal information

3.2 Third parties that are able to receive the personal information of electors are specified under legislation and include: political parties; state and territory electoral commissions; medical researchers; providers of health screening programs; and persons or organisations undertaking identity verification or reporting for activities such as anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing.12 The Electoral Commissioner may also provide the roll (or extracts) to prescribed Commonwealth entities and other persons or organisations he or she deems appropriate.

3.3 The AEC advised the ANAO, in February 2015, that it has conducted a review of the data provided to third-parties under the Electoral Act. Specifically, the AEC had reviewed, and developed a policy to support, the distribution of electoral roll information to medical researchers. A similar review has not been conducted for distribution of roll information to other third parties.

3.4 Information on the electoral roll can also be inspected at AEC offices.13 Over the last two years, the AEC has sought to limit access to the roll by restricting the purposes for which members of the public can inspect the roll. However, following advice from the Commonwealth Ombudsman that the restriction on access to the roll was contrary to the intention of the Electoral Act, the AEC reversed its decision in March 2015.14

3.5 Consistent with the findings in Audit Report No. 28 2009–10, the AEC continues to address privacy issues by publishing policies on its website, and disclosures in its annual report and on electoral forms.15 The AEC maintains a Privacy Policy on its website16, outlining, in general terms, the circumstances in which the AEC may collect personal information and providing some examples of the kinds of information that may be collected.17 The policy provides only a:

- general explanation for collecting specific pieces of personal information; and

- statement that information will be provided to third parties.

3.6 The policy does not explain why some information, such as an elector’s occupation, relates to electoral enrolment and voting, or which third parties access the information. The identity of third parties with access to the roll is, however, published in the AEC’s annual report, in its online enrolment form and to a lesser extent, on physical enrolment forms.

Use of third party data for roll management purposes

3.7 The AEC’s reliance on third party data for roll management purposes has increased in the period since Audit Report No.28 2009–10 was completed, with the sourcing of new databases18 of personal information for data matching; increasing the need for a sound information management policy. The adoption of direct enrolment and update is the one area in which the AEC has been active in considering information management. As part of the development of direct enrolment and update, the AEC, in consultation with the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, completed a Privacy Impact Assessment in December 2012. This document sets out how the AEC would address each of the then Information Privacy Principles (now known as the Australian Privacy Principles) for the direct enrolment and update. However, it is only one part of the AEC’s data matching activities and data matching is only one aspect of the management of an electors’ personal information.19

Has a sound basis for costing state and territory roll-related services been established?

In June 2015, the AEC adopted a national per elector contribution rate for the provision roll-related services to state and territory electoral commissions. This change was made in response to identified weaknesses in the previous cost sharing arrangements. The national contribution rate was: based on a per elector rate calculated from the AEC’s historical cost of providing state and territory roll-related services; and discounted, for some jurisdictions, in recognition of their investment in enrolment systems.

While the AEC has now established a basis for costing state and territory roll-related services, further work is required to have all state and territory electoral commissions agree to the new national rate, and to have the relevant agreements updated to reflect both the rate and the work the AEC actually undertakes.

3.8 The AEC has traditionally managed electoral rolls and/or provided roll related services to each state and territory electoral commission for which each jurisdiction has made a financial contribution. This form of co-ordination has assisted in streamlining electoral management, reducing duplication of effort, and fostering cooperation and information sharing between different levels of government. The services provided and funding contributed are underpinned by agreements, called Joint Roll Arrangements20, with each state and territory electoral commission as well as:

- Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) with the electoral commissions in the Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania;

- MOUs and Service Level Agreements with the electoral commissions in Western Australia and Victoria; and

- an Exchange of Information Agreement with the New South Wales Electoral Commission.

3.9 The basis on which the AEC determined the rate of the financial contribution included in Joint Roll Arrangements (or equivalent agreements) was a particular area of focus in Audit Report No.28 2009–10. In that report, the ANAO observed that, from 1995, a per elector contribution rate, indexed to inflation, was established in all Joint Roll Arrangements. However, the contribution rates differed across jurisdictions and the AEC had not clearly documented the basis for their calculation.21 As a result, the ANAO recommended that the AEC establish a sound basis for costing the maintenance and review of the electoral rolls and production of state and territory roll products (Recommendation No. 2).

3.10 Since 2010, the AEC’s capacity to undertake activity-based costing has been considered within the context of a funding review. The AEC also commissioned the development of two costing models. Figure 3.1 provides an overview of the work undertaken. The primary costing model relied on by the AEC is the ‘AEC Costing Model’, which was developed in 2013 and reviewed in 2015.

Figure 3.1: Activities related to Joint Roll Arrangements since 2010

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

3.11 The AEC Costing Model shows significant variations in the cost per elector across jurisdictions. For example, in 2013–14 the calculated per elector rates varied between $0.64 and $1.21. These variations have been further widened through the negotiation processes with state and territory electoral commissions (the per elector rates charged for the same period varied between $0.59 and $1.21), which have incorporated:

- an inconsistent approach to setting per elector rates over time. In 2013–14, for example, a reduction in the contribution rate charged for one state was based on the results of the AEC Service Costing Tool. This tool was not used to set the contribution rate for any other jurisdiction; and

- a history of ‘discounting’ per elector rates in some jurisdictions but not others.

3.12 In June 2015, the Electoral Commissioner approved a uniform national per elector rate of $0.815 to be passed on to all state and territory electoral commissions as a contribution for the ongoing management of the electoral rolls and provision of roll products. Further, while the varying discounts that applied to the contributions will cease, two jurisdictions have been offered discounts in recognition of their investment in enrolment systems. The AEC considers that this investment in enrolment systems has created less reliance on the products and services provided by the AEC. A number of states are yet to agree to the new rate.

3.13 In September 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that there was an error in its calculation of the national per elector rate, and that this was only discovered after the proposed per elector rate of $0.815 had been sent to the state and territory electoral commissions. The AEC further advised the ANAO that, after making an adjustment for inflation for the 2014-15 year (the per elector rate has not been adjusted to reflect expected cost inflation over the term that the new rate is expected to be in place for) the under-recovery would be in the order of $45 000 per year.

3.14 Once the state and territory electoral commissions have agreed to the new rate, there will be a need to update a number of relevant agreements, such as the Joint Roll Arrangements. In this respect, elements of some agreements are not current and refer to activities no longer performed by the AEC (for example, habitation reviews, which were replaced by the AEC’s continuous roll update mail-out programme in 2000 and Sample Audit Fieldwork in 2003). In addition, all Joint Roll Arrangements and a number of supporting MOUs were entered into prior to the introduction of direct enrolment and update in 2012.22 In August 2015, the AEC advised ANAO that it has provided updated draft MOUs to the Electoral Commissions of the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory and Queensland for consideration.

Has the approach to Sample Audit Fieldwork improved?

Changes made to Sample Audit Fieldwork were inconsistent with the intent of the earlier recommendation. Rather than being expanded to include those locations where issues concerning roll accuracy and completeness are most prevalent, coverage has contracted and continued to focus on the least costly locations to visit.

3.15 Roll review activities provide assurance that the federal roll and other roll products are accurate and complete. Recommendations made by the ANAO and the Committee from 2001 onwards have emphasised the importance of undertaking a periodic review of the electoral roll to test its integrity and the effectiveness of roll management activities.23 In response, the AEC developed the Sample Audit Fieldwork programme (SAF) in 2003. SAF involves doorknocking addresses in randomly selected locations throughout Australia to check electoral roll information for those addresses.

3.16 In Audit Report No.28 2009–10, the ANAO identified a number of limitations24 in the SAF sampling methodology and, as a result, recommended that the AEC expand and enhance the sampling methodology for undertaking habitation reviews as part of its roll management activities. Despite agreeing to this recommendation, SAF has only been undertaken twice, as shown in Table 3.1, and the sampling methodology has not been enhanced or expanded.

Table 3.1: Results of SAF events, 2004–15

|

Year |

Participation1 (%) |

Completeness2 (%) |

Accuracy3 (%) |

Reason for not undertaking SAF |

|

|

2010 |

N/A4 |

N/A |

N/A |

Competing priorities (federal election) |

|

|

2011 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Competing priorities (election evaluation and legislative change) |

|

|

2012 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Evaluation of SAF underway |

|

|

2013 |

97.6 |

92.4 |

88.6 |

– |

|

|

2014 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Fieldwork scheduled for Financial Year 2014–15. May 2015 was selected. |

|

|

2015 |

98.7 |

93.8 |

89.2 |

– |

|

Note 1: Enrolment participation: number of eligible electors currently enrolled as a percentage of total number of persons estimated in the sample to be eligible to enrol.

Note 2: Enrolment completeness: number of eligible electors currently on divisional rolls as a percentage of those eligible to be on those rolls.

Note 3: Enrolment accuracy: percentage of current electors enrolled for the address at which they are living: that is, their enrolment details required no amendment.

Note 4: N/A: SAF results were not available for that year as an event did not occur.

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC records.

3.17 The AEC raised concerns relating to the efficiency and effectiveness of conducting the SAF process, advising the ANAO in May 2015 that:

While ideally SAF is to be conducted on an annual basis other factors and their impact must be considered when scheduling SAF. These include federal and state electoral events, funding [and] other priorities. The AEC is seeking assistance from ABS in looking at other, more cost effective, methods to conduct an audit of the roll and [Continuous Roll Update] activities such as a combination of fieldwork and household surveys.

3.18 Notwithstanding these concerns, SAF is the primary assurance tool that the AEC uses to measure roll accuracy and completeness. In this context, the AEC engaged with the ABS in 2012, and again in 2015, with a view to expanding and enhancing the SAF sampling methodology. The ABS’ advice was used by the AEC to determine the sample size, based on the level of residual standard error25 (RSE) that the AEC considered appropriate. Specifically, a sample that has a RSE of:

- less than five per cent generates highly reliable results;

- between five per cent and 10 per cent generates reliable results; and

- between 10 per cent and 15 per cent generates results that need to be interpreted with some caution.

3.19 In the advice provided to the AEC, the ABS identified that an increase in the reliability of results at the divisional level would require the AEC to visit at least one million more electors than were visited in 2007 (83 176 electors were visited by the AEC in 2007). Following consideration of this advice, the AEC decided not to expand the sample due to the additional costs. As a result the original methodology (provided by the ABS in 2003) was used to develop the sample for the 2013 event, with the intent of achieving ‘reliable’ results (based on a 7.5 per cent RSE).

3.20 In March 2015, the Electoral Commissioner decided to conduct the 2015 SAF using a 10 per cent RSE (producing results needing to be ‘interpreted with some caution’) at the state and territory level, with the exception of the Northern Territory (10 per cent RSE at the divisional level). A significant factor in this decision was cost, with the AEC estimating the total cost of the 2015 event to be $420 000 or $8.72 per elector.26

3.21 In August 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that its approach to the SAF methodology was to obtain the most reliable results given the available budget and the need to maintain other roll management activities, rather than seeking to obtain a given level of reliability. In this respect, the funding currently allocated for SAF ($347 445 was spent in 2015) is not at a level that supports a sample size large enough to obtain reliable assurance that the electoral roll is accurate and complete, SAF’s fundamental purpose.

3.22 Other limitations of the SAF sampling methodology used for the 2013 and 2015 SAF events included:

- sampling from a limited population: the ABS advice provided to the AEC assumed the sample would be selected from all the electors on the roll. However, the AEC excluded areas not covered by its Continuous Roll Update programme because fieldwork in remote areas was ‘problematic’ due to unreliable transport, mail delivery and communications.27 As a result, the AEC obtained no assurance that the roll in sparsely populated areas was accurate; and

- lower than expected response rates: the ABS advice provided to the AEC was premised on a 100 per cent response rate. Of the 60 569 addresses sampled in the 2013 SAF, residents at 12 690 addresses (18 per cent of sampled addresses) could not be contacted or refused to provide information, resulting in an 82 per cent response rate. A lower than expected response rate reduces the reliability of the results.

3.23 Moreover, assumptions underpinning the sampling approach also relied on dated information. Specifically, between 2004 and 2013, relatively fewer Victorian electorates were sampled because, in 2003, the ABS assumed that the Victorian electoral roll was more accurate and complete than the electoral rolls in other states.28 This assumption was retained notwithstanding that in the period after 2004 SAF results were available for a range of divisions to confirm or challenge this assumption and inform the sampling approach. A change in sampling methodology in 2015 has resulted in an increase to the number of Victorian electors sampled.

3.24 Other characteristics of the sample in 2015 included:

- the majority of electors sampled being based in VIC, NT, WA and ACT, which is inconsistent with the four states that have the lowest enrolment rates (NT, WA, QLD and NSW); and

- fewer electors in NSW compared to ACT even though NSW has the largest number of electors and second highest rate of divergent records in 2015.

Recommendation No.2

3.25 To provide information on the accuracy of the electoral roll and enable reporting against performance targets, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Electoral Commission implement a more reliable method of estimating the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll.

Entity response: Agreed with qualification.

3.26 The AEC will continue to evolve the existing means of estimating the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll including the approach to Sample Audit Fieldwork, the use of the Electoral Integrity Framework, and the use of population statistics provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Further, the AEC will consider other mechanisms to estimate the accuracy and completeness of the electoral Roll. Mechanisms will be adjusted as appropriate, taking into account appropriate resource allocation between achieving an accurate and complete electoral Roll, and measuring these dimensions of Roll integrity.

4. Have the remaining election-related recommendations been implemented?

Areas examined

Most of the recommendations included in Audit Report No.28 2009–10 could be categorised as relating to improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll, enhanced workforce planning and greater security of the transport and storage of completed ballot papers. In addition, the ANAO made recommendations relating to the:

- development of strategies to mitigate the risk to the credibility of election results posed by the current practices for reporting of election-night counts (Recommendation No. 8(a)); and

- adoption of comprehensive performance standards for the conduct of elections (Recommendation No. 9).

Conclusion

Despite agreeing to both recommendations in 2010, the AEC only commenced implementation of these recommendations in 2015. By August 2015, the AEC had developed, for the by-election for the electorate of Canning in September 2015:

- a unique password for each polling place to verify the credibility of the results provided by Officers-in-Charge to divisions on polling night; and

- an election service plan. The AEC published an election service plan on its website prior to the by-election and has advised that it intends to report against the performance standards in the plan.

Has the AEC strengthened the process for reporting election night counts?

The AEC had not undertaken any action on this recommendation prior to the 2013 election. A process for verifying the credibility of election night results was selected for the Canning By-Election, and future general elections.

4.1 ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10 highlighted practices for the reporting of election-night counts by Officers-in-Charge. This involved polling-booth staff, on election night, telephoning the results of the count through to the divisional office. From there, results were entered into the Election Management System and then transmitted to the Virtual Tally Room and National Tally Room.

4.2 Three measures were used to provide assurance as to the authenticity of the results received by divisional offices, the:

- use of dedicated lines/unlisted phone numbers;

- a warning triggered by the Election Management System where count results were outside of an expected range29; and

- caller’s statement that he/she is calling from a particular polling booth.

4.3 The ANAO identified a number of concerns relating to these measures, including the absence of an electronic or formal system of caller verification and limitations on the ability of staff at divisional offices to enter data directly into the Election Management System while receiving the results from polling place staff. Similar concerns had been raised, but were not addressed by the AEC, in security risk reviews commissioned by the AEC prior to the 2004 and 2007 elections. These findings informed the ANAO’s recommendation that the AEC develop strategies to mitigate the risk to the credibility of election results posed by the practices for reporting of election-night counts by Officers-in-Charge (Recommendation 8(a)). The AEC agreed to this recommendation, stating:

The AEC’s risk-assessment practices acknowledge a range of known and theoretical threats to the integrity of the election results and the Commission regularly reviews its mitigation strategies in the context of the prevailing threat environment.30

4.4 Notwithstanding agreeing to the ANAO recommendation, and reporting to the Committee that the recommendation had been ‘closed’, the AEC did not implement any changes in practices or procedures relating to the reporting of election night counts for either the 2010 or 2013 federal elections. In April 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that this decision was made on the basis that existing processes provided adequate mitigation against the possibility of persons attempting to fraudulently phone in results on election night. Following a review of its implementation of ANAO’s earlier recommendations, the AEC:

- included the risk associated with election night counts, in particular, the ‘possibility of tampering with election results on the night’ in its Federal Election Events Risk Register (Risk Register dated May 2015); and

- developed a stand-alone Credibility of election night results: 2014–15 Risk Management Plan (Risk Management Plan) in February 2015.

4.5 Together, these documents recognised that tampering with election night results may occur as a result of a member of the public, who is not a polling place Officer-in-Charge, contacting a divisional office and providing incorrect election night results in a ‘deliberate attempt to cause mischief or mislead public’. As a result, there may be ‘loss of the public’s trust in the AECs (sic) processes and integrity … political backlash from parties/candidates involved and media coverage … lack of confidence in the results could see requests for re-counts’.

4.6 Despite inclusion of the risk in the Federal Election Events Risk Register in May 2015, the AEC did not change the way that the risk to election night results was mitigated at that time. In June 2015, the AEC advised the ANAO that it is implementing a solution whereby a unique password is allocated for each static polling place and Pre-Poll Voting Centre for the purpose of verifying the credibility of the source information at the time of transmission of results from Officers-in-Charge to divisions on polling night. In August 2015, the AEC further advised the ANAO that this change would be in place for the by-election for the electorate of Canning in September 2015.

Has the AEC reported on its performance in an election event?

The AEC had not undertaken any action on this recommendation prior to the 2013 election. An election service delivery plan was subsequently prepared for the Canning By-Election, with the AEC advising of its intention to make this plan available on its website and report against the standards in the plan following the election event.

4.7 Audit Report No.28 2009–10 outlined that the AEC ‘does not publish or report upon election performance standards for its staff and for its operations in support of elections’.31 The AEC agreed to Recommendation No.9 in the report, which involved the development and reporting against comprehensive standards for the conduct of elections, stating that the:

AEC will develop comprehensive performance standards to enhance the information that it reports to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters in that Committee’s normal review of the conduct and performance of a federal election.32

4.8 With reference to the ANAO’s recommendation, however, the Committee noted, in its inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 federal election that:

[o]f particular interest is the lack of clearly developed national Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and standards that would allow the AEC and the Parliament to measure performance against national programme directions for the conduct of elections, as well as against legislative, policy and procedural requirements. The AEC has acknowledged this lack, but development has not progressed further.

… the [AEC’s] response to the ANAO’s recommendation … concerning the development of comprehensive performance measures for the conduct of elections is insufficient. The AEC’s response has been to develop internal tools, reviewed internally. These do not create the comprehensive, overarching performance standard framework that would allow for adequate visibility of and reporting on election conduct.33

4.9 In regard to current performance reporting practices, the following election management indicators published in the AEC’s 2013–14 Annual Report provide limited insights into the AEC’s management of elections:

Federal election events (including by-elections and referendums) successfully delivered as required within the reporting period. AEC election practices and management are in accordance with relevant legislation. All election tasks carried out in accordance with legislated timeframes.

High level of election preparedness maintained and key milestones set.34

4.10 Under the AEC’s reform programme, the AEC developed a set of performance standards in 2015 that it intends to apply to federal election events. It is the AEC’s intention to communicate these standards to the public in an election service delivery plan, which will be available on the AEC’s website. In August 2015, the AEC published an election service plan on its website for the Canning By-election in September 2015.35 The AEC advised the ANAO that it intends to report against the standards listed in the plan.

Appendices

Appendices

Please refer to the attached PDF of the report for the Appendices:

- Appendix 1: Response from the Australian Electoral Commission

Footnotes

1 AEC submission 20.4 to the Committee in May 2014.

2 Department of Finance, Portfolio Budget Statements, available from <www.finance.gov.au> [accessed 20 July 2015].

3 ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10, The Australian Electoral Commission’s Preparation for and Conduct of the 2007 Federal Election, 21 April 2010.

4 The follow-up of the AEC’s implementation of that recommendation was prioritised as it was an area of particular interest to the Committee.

5 In early November 2013, the AEC commissioned Mr Mick Keelty AO APM to undertake an inquiry into the circumstances of the missing ballot papers identified during the recount of Senate votes in WA. Audit Report No.4 2014–15 examined the AEC’s compliance with new policies and procedures introduced to address the recommendations made in the Keelty Report.

6 Habitation reviews are a comprehensive check of the electoral roll, under which the AEC hired casual staff to visit the majority of habitations in Australia. Where it was impractical for field workers to conduct doorknocks of residential addresses, the review was undertaken by mail.

7 Prior to the creation of the Board, the AEC’s research programme was less structured and more reactive to events and requirements as they occurred in the electoral sphere. Research was conducted on the basis of national and international trends in electoral issues, or at the request or prompting of institutions such as the JCSEM.

8 The AEC compares Centrelink and driver licensing data with the electoral roll to identify citizens that may need to be added to the roll or have their details updated. To confirm the identity and eligibility of prospective electors, the AEC also refers to identity data from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, and Births, Deaths and Marriages registries.

9 The number of enrolled electors who voted in the election compared to the number of enrolled electors.

10 In relation to enrolment forms, the AEC provided citizens with the option of lodging enrolment forms, that can be signed electronically (including by a witness), through its website.

11 Divergence exists between the federal and Western Australian rolls due to the inability of the Western Australian Electoral Commission to recognise Commonwealth direct enrolments under state electoral legislation.

12 For example, Regulation 7 of the Electoral and Referendum Regulations 1940 prescribes Betfair Pty Limited as an organisations that ‘verifies, or contributes to the verification of, the identity of persons for the purposes of the Financial Transaction Reports Act 1988‘ and, therefore, may receive the roll (or an extract) upon request.

13 Section 90A of the Electoral Act requires that: the federal roll be available during ordinary office hours at AEC divisional offices; and the roll for each state and territory be available at each capital city office of the AEC during ordinary business hours.

14 Following the receipt of a compliant, the Commonwealth Ombudsman reviewed the restrictions that the AEC had placed on the public accessing the electoral roll to find lost family members.

15 ANAO, Audit Report No.28 2009–10, The Australian Electoral Commission’s Preparation for and Conduct of the 2007 Federal General Election, p. 53.

16 AEC, Privacy Policy [Internet], available from <www.aec.gov.au> [accessed 10 July 2015].

17 This includes references to basic identity details (such as a name, address and date of birth, age and gender), information on personal circumstances (such as marital status and occupation) and government identifiers.

18 For example, the AEC has sourced data from the Australian Taxation Office to support the process of identifying, and sending letters to, potential electors and existing electors with enrolment records that are not up-to-date (part of the Continuous Roll Update mail-out process).

19 As was noted in Audit Report No.28 2009–10, governance arrangements would relate to the collection, processing, data-matching, distribution and management of electors’ personal information (Recommendation No. 1(a)).

20 In addition to Joint Roll Arrangements, the AEC has entered into equivalent agreements including: Joint Enrolment Procedures with the NSW Electoral Commission, Joint Electoral Enrolment Procedures with the Victorian Electoral Commission and Joint Enrolment Process with the Western Australian Electoral Commission.

21 The exception to this rule is the AEC’s Service Level Agreement with the Victorian Electoral Commission, which established a fixed annual charge (indexed to inflation) rather than a per elector contribution rate.

22 Direct enrolment and update is only referred to in MOUs with South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia.

23 ANAO Audit Report No.42 2001–02 Integrity of the Electoral Roll. ANAO Audit Report No.39 2003–04 Integrity of the Electoral Roll–Follow-up Audit. Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, The Integrity of the Electoral Roll: Review of ANAO Report No.42 2001–02, November 2002.

24 Audit Report No.28 2009–10, paragraphs 3.30 to 3.31.

25 Sampling error is caused by the inability to examine all population units. One measure of sampling error is the standard error. It is a measure of the precision with which a sample statistic by chance approximates the average results of all possible samples. The RSE of a sample survey estimate is the ratio of the standard error to the value of the sample estimate. This ratio is often expressed as a percentage. It provides a convenient description of the size of the sampling errors present in a survey estimate. The RSE is particularly useful in comparing the accuracy of two different sample estimates (the estimate with the smaller RSE is more accurate).

26 This estimate does not include permanent staff working on SAF activities.

27 The 2013 SAF report noted that ‘SAF samples only those areas covered by the mail review program’ and that while SAF is used as a measure of ‘accuracy’ it reflects the accuracy of those areas covered by the mail review program.

28 A pilot study, conducted by the AEC in 2003, reviewed enrolment records in Lowe in NSW, Moreton in Queensland and Jaga Jaga in Victoria. The results of the pilot study indicated that, in 2003, enrolment records in the Victorian electorate were more accurate when compared to results from the other states.

29 Data entry of election night results into the Election Management System is validated against expected number of votes taken and a variance of +/- 20 per cent results in a warning from the system.

30 ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10, paragraph 5.102.

31 ANAO Audit Report No.28 2009–10, paragraph 5.103.

32 ibid, paragraph 5.108.

33 Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Parliament of Australia, The 2013 Federal Election: Report on the conduct of the 2013 election and matters related thereto (2015), p. 63-64.

34 AEC, Annual Report 2013–14, p. 47.

35 AEC, Canning by-election Service Plan [Internet], available from <www.aec.gov.au> [accessed 31 August 2015].