Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Management of Physical Security

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of physical security arrangements in selected Australian Government agencies, including whether applicable Australian Government requirements are being met.

Summary

Introduction

1. Effective protective security can help maintain the operating environment necessary for the confident and secure conduct of government business, the delivery of government services and the achievement of policy outcomes. Well‑designed protective security arrangements can support Australian Government agencies to manage risks and threats that could result in: harm to their staff or to members of the public; the compromise or loss of official information or assets; or not achieving the Government’s policy objectives.1

Protective Security Policy Framework

2. Protective security in Australian Government agencies is governed by the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), which adopts a principles‑based approach2 to protective security. Under the PSPF, relevant agencies3 are required to establish appropriate protective security arrangements to mitigate threats or attacks against people, information or assets based on an assessment of their particular security risks and threats.

3. The PSPF considers physical security to be a combination of physical and procedural measures that should provide a safe and secure environment for the agency’s employees, contracted service providers, members of the public, and agency resources. According to the PSPF, an agency’s physical security program should aim to:

- Deter—measures implemented which adversaries perceive as too difficult, or needing special tools and training to defeat.

- Detect—measures implemented to determine if an unauthorised action is occurring or has occurred.

- Delay—measures implemented to:

– impede an adversary during an attack, or

– slow the progress of a detrimental event to allow a response before agency information or physical assets are compromised.

- Respond—measures taken once an agency is aware of an attack or event to prevent, resist or mitigate the attack or event.

- Recover—measures taken to restore operations to normal (as far as possible) following an incident.4

4. An agency’s protective security policies, plans and procedures—which typically comprise a mix of governance, personnel security, information security, and physical security components—should be integrated into the agency’s day‑to‑day operations and management activities.

5. In 2013, agencies were required to undertake a self‑assessment of, and to report on, their compliance with the PSPF’s 33 mandatory requirements.5 These arrangements were introduced following a two year implementation period intended to allow sufficient time for agencies to adopt the new protective security (including physical security) requirements.

Selected agencies in this audit

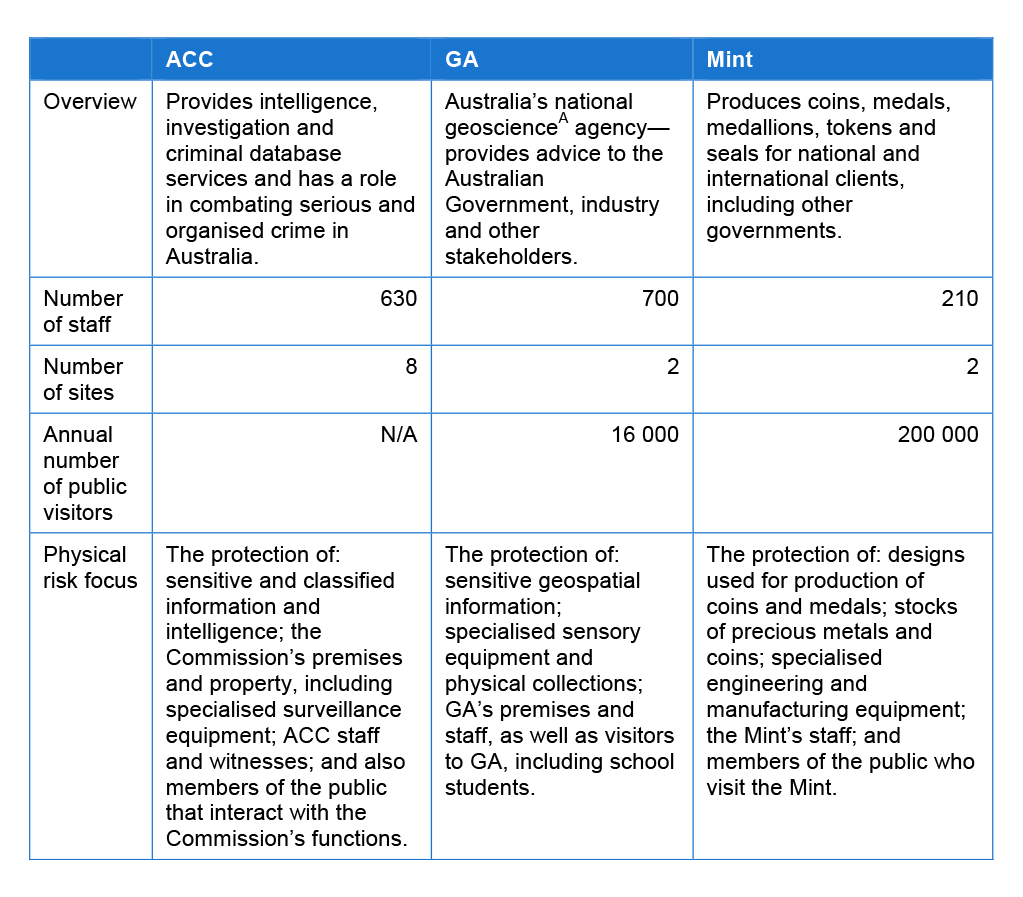

6. Three agencies were selected by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) to be included in this performance audit: the Australian Crime Commission (ACC); Geoscience Australia (GA); and the Royal Australian Mint (Mint). The selected agencies each face a range of physical security risks arising from their organisational objectives and operations, and the characteristics and sensitivity of the information and assets in their care. Further information on these agencies’ physical security risk context and operating environment is provided in Table S.1.

Table S.1: Overview of the agencies in this audit

Source: Based on information at the selected agencies.

Note A: Any sciences relating to the earth.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

7. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of physical security arrangements in selected Australian Government agencies, including whether applicable Australian Government requirements are being met.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high‑level criteria:

- appropriate protective security governance arrangements are in place, including clear roles and responsibilities and sound arrangements for training, communication, incident management and reporting;

- a sound physical security risk assessment was undertaken and suitable management practices were established; and

- a physical security policy and an agency security plan have been developed and implemented, and are supported by relevant procedures.

9. The audit assessed the selected agencies’ management of physical security against: the seven mandatory PSPF requirements for physical security; and nine of the 13 mandatory PSPF governance6 requirements. Appendix 3 provides details of the 16 PSPF mandatory requirements addressed in this audit. The audit did not assess the selected agencies against the PSPF mandatory requirements relating to information security and personnel security, or the information and communications technology (ICT) security requirements contained in the Information Security Manual.7 A forthcoming ANAO performance audit will examine the application of ICT security requirements relating to cyber‑security by seven Australian Government agencies.8

10. Further, the Attorney‑General’s Department’s (AGD) policy and coordination role was not examined in this audit. However, where the ANAO identified matters that may affect implementation of the physical security requirements at a whole‑of‑government level, they are discussed in this report.

11. The audit did, however, examine whether the selected agencies had implemented a number of recommendations made in earlier ANAO across‑agency performance audits that addressed matters relevant to the management of physical security, namely: Audit Report No.23 2002–03, Physical Security Arrangements in Commonwealth Agencies; and Audit Report No.25 2009–10, Security Awareness and Training.9

Overall conclusion

12. The protection of sensitive information, agency resources and staff is an ongoing responsibility of Australian Government agencies. Under the mandatory requirements set out in the PSPF, agencies must provide and maintain a safe working environment for their staff, contractors, and members of the public and limit the potential for compromise of the confidentiality, integrity and availability of official information and assets.10 Agencies are expected to manage foreseeable security risks, having regard to their business context and operations, within available resources.

13. The agencies selected for this audit—the Australian Crime Commission (ACC), Geoscience Australia (GA), and the Royal Australian Mint (Mint)—each experience a range of physical security risks, threats and challenges in the conduct of their business activities, reflecting their particular mix of functions, assets and information holdings.

14. Overall, the physical security arrangements adopted by each of the selected agencies were generally effective, and for the most part, the agencies had met, or partially met, the applicable PSPF requirements. Key physical security controls and procedures tested by the ANAO in each agency were largely aligned with the agencies’ identified risks and specific business needs, and were generally operating as intended. Nonetheless, there were areas where improvements were warranted; most notably, there was scope to better align security risk management activities with the PSPF’s requirements, including identifying and managing risks to the public, and further integrating security risks with other organisational risk activities. There were also opportunities to improve the ongoing effectiveness of physical security management by adopting a more structured approach to security assurance and monitoring arrangements; a process which benefits from senior leadership oversight.

15. Observations on the key areas of the audit’s focus are discussed in the following paragraphs. The key areas relate to: governance; security risk management; security controls and procedures; compliance with selected PSPF mandatory requirements; and the implementation of relevant recommendations made in previous ANAO performance audits.

16. Each agency established appropriate governance arrangements to oversee the management of physical security, including appointing appropriately skilled and experienced staff to key security roles. In addition, the Mint had established appropriate security assurance and monitoring arrangements—providing a sound basis for assessing the ongoing effectiveness of its policies and control measures relative to its evolving risk environment.

17. The Mint was the only agency that had consistently implemented the full range of security risk management processes, as part of the risk‑based approach to physical security required by the PSPF. The approach adopted by the Mint included consideration of risks relating to the duty of care owed to members of the public. At the ACC and GA, opportunities were identified to: bring the conduct of security risk assessments into line with the requirements of the PSPF; improve linkages between their security risk activities and other agency risk management activities; and better demonstrate how their security policies and underlying procedures aligned with their assessed security risks.

18. Key controls identified by agencies in their security‑related policies and procedures that were examined by the ANAO were generally operating as intended. Further, the ANAO did not identify any significant gaps in the security control environment for any of the three agencies. The three agencies had also established processes to promote an effective security risk culture, including raising awareness of security issues through the implementation of training and other information and communication measures.

19. The ANAO’s assessment of the agencies’ compliance with the PSPF mandatory requirements relevant to this audit was broadly consistent with the agencies’ self‑assessments.11 Overall, the level of compliance assessed for the agencies reflects a level of maturity with the risk‑based approach required under the PSPF that might be expected at this relatively early stage of the PSPF’s application.

20. The ACC and Mint had taken appropriate steps to address past ANAO audit recommendations relating to physical security. However, GA was assessed as having not implemented one of the recommendations and only partially implemented a number of the recommendations.

21. This audit has highlighted some key lessons for senior leaders as agencies continue to work towards implementation of the physical security requirements and standards prescribed by the PSPF. Agency security is a shared responsibility, which requires security awareness and accountability at all levels. A strong internal security culture is enhanced by integrating the assessment and ongoing management of security risks into an agency’s governance and enterprise‑wide risk management arrangements. Periodic executive review of an agency’s physical security risks and posture, including by boards of management, can provide added oversight and assurance that risks have been managed appropriately.

22. The ANAO has made two recommendations directed at strengthening the design and application of physical security assurance and monitoring activities, and security risk management practices. It is important that all Australian Government agencies actively monitor their protective security risks—and the effectiveness of controls designed to mitigate those risks—in light of their changing operational contexts and the constrained resourcing environment facing agencies. The recommendations have broad applicability to other Australian Government agencies.

Key findings by chapter

Governance Arrangements (Chapter 2)

23. Protective security governance, as set out in the PSPF12, involves both conformance—how an agency uses protective security arrangements to ensure it meets its obligations and Government expectations—and performance—how an agency uses protective security arrangements to contribute to its overall performance.

24. Sound arrangements for the delivery and oversight of physical security activities were in place at each of the selected agencies. Specifically, each of the agencies had clearly identified the key security roles and responsibilities required by the PSPF.13 At each agency, the personnel appointed to these roles possessed an appropriate level of knowledge, skills and experience14, enabling them to fulfil their duties. Importantly, all agencies had established forums to oversee and support the management of physical security. The Mint and GA had established dedicated security committees, while the ACC had a broader‑focused operational management committee where security related matters could be raised.

25. To assist in monitoring both the performance and conformance aspects of the PSPF, agencies should establish a security assurance strategy outlining their approach to managing protective security. An assurance strategy is an important means to guide approaches to monitoring the ongoing effectiveness of agencies’ security policies and control measures relative to an evolving risk environment. The Mint had defined a security assurance strategy, outlining its approach to the oversight and monitoring of security requirements. At an operational level, however, all agencies had processes and procedures to identify and resolve day‑to‑day physical security incidents.

26. Each of the audited agencies submitted their first self‑assessment compliance report against the PSPF’s mandatory requirements to the AGD in September 2013, as required.15 In doing so, the ACC and GA adopted a three‑level rating system—’compliant’, ‘partially compliant’ or ‘non‑compliant’. However, this approach was inconsistent with the reporting guidance in the PSPF.16 Specifically, the guidance proposes that the status of each mandatory requirement be reported as ‘fully compliant’, ‘non‑compliant’ or ‘not applicable’. In cases of non‑compliance, the guidance suggests that further details—such as mitigation measures and residual risks—should also be supplied.

27. The ANAO observed that the binary (fully compliant or non‑compliant) approach proposed by the AGD does not adequately reflect circumstances where agencies may have met most aspects of a particular requirement, but have outstanding actions (at the time of preparing their report) to demonstrate full compliance. Further, it does not capture agencies’ progress as they work towards an improved level of compliance. In the course of this audit, AGD advised that it plans to develop additional guidance material for agencies’ self‑assessment and reporting, and are also investigating the potential of using a ‘maturity level model’ for PSPF reporting.

28. The PSPF reinforces the importance of having strong communication channels within an agency—including alignment between protective security and work health and safety and giving consideration to security issues during the design or modification of facilities.17 The PSPF also suggests agencies share information or collaborate with other agencies in relation to security management. The Mint had structured arrangements in place to support ongoing communication and collaboration between the security team and key internal stakeholders—including ‘health and safety’ staff—and other government agencies. Equivalent arrangements in the ACC and GA were mostly informal and the agencies were unable to demonstrate that these arrangements were consistently applied.

Risk Management (Chapter 3)

29. Under the PSPF, agencies are required to adopt a risk‑based approach to managing protective security, including physical security.18 While each of the agencies had formal enterprise‑wide risk management policies and procedures, the Mint had also clearly defined its approach to, and methodology for, the management of security risks.

30. Each agency had recently conducted an assessment of security risks and associated treatment options. The Mint was the only agency that had consistently implemented the full range of security‑specific risk management practices required by the PSPF19, being the: identification of critical assets; assessment of business impact levels; assessment of risks to the public; identification of site‑specific risks and development of associated plans; and assessment for heightened threat levels. The ACC and GA had established some of these measures but not all, or had not applied them on a consistent basis.

31. Further, the Mint demonstrated that it had an integrated approach to aligning security risk management activities with other organisational risk activities, such as fraud control planning. An integrated approach facilitates internal understanding and assessment of the interdependencies between security risks and other risks.

32. The PSPF provides that agencies should develop protective security policies and plans to meet business needs commensurate with the nature and assessment of identified risks.20 The Mint was able to demonstrate that its security policies and plans had been updated and aligned to the outcomes of their most recent security risk assessment. Both the ACC and GA advised that they were in the process of doing so—having finalised their protective security risk assessments in January 2013 and June 2012 respectively.

Control Activities (Chapter 4)

33. To effectively manage their physical security risks and threats, agencies will typically have in place a range of measures, processes or controls. Staff are more likely to understand the nature and purpose of these controls, including their responsibilities for the day‑to‑day operation of these measures, where agencies have appropriately tailored procedural documentation, and well‑designed security awareness and training mechanisms.

34. The ANAO’s examination of a selection of the procedures and controls implemented to manage key physical security risks at each of the audited agencies, found that the controls were generally operating as intended. Importantly, the observed controls generally aligned with each agency’s security policies, plans and procedural documentation.

35. Providing staff and contractors with security awareness training tailored to the agency’s operating circumstances and risks reinforces understanding of security‑related responsibilities, and also supports promotion and maintenance of a security‑aware culture.21 The agencies had each established suitable security training and awareness programs using a range of communication methods and delivery channels. In each agency, the components of awareness and training programs that were examined during the audit were mandatory for all staff and incorporated content that was well‑designed and informative. Notably, the content of each component of the security awareness training programs examined by the ANAO was consistent with the nature of each agency’s security context. At GA and the Mint, service providers were also required to complete the security awareness training. Overall, completion rates of the security awareness training at the three agencies were generally high.22 The agencies advised that they had taken steps to address the issue of some staff not completing the training.

Summary of agency responses

36. The proposed audit report was provided to each of the audited agencies, and an extract of the proposed report was provided to AGD. Each agency’s formal response to the proposed report is included at Appendix 1.

37. In addition, AGD provided the following summary comments:

The Attorney‑General’s Department (AGD) has protective security policy responsibility for the Australian Government as detailed in the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF). AGD supports the two recommendations which will strengthen the risk management approach to protective security within agencies, while providing assurance that the measures implemented remain effective.

An agency’s PSPF compliance report requires qualification where compliance with the mandatory requirement is not met. The primary focus of this qualification is to identify the residual risks the agency is exposed to, and how the agency plans to mitigate those risks and achieve compliance with the mandatory requirement over time. AGD considers that reporting ‘partial compliance’, as a degree of non‑compliance with a mandatory requirement, is unnecessary as this distinction can be made as a part of the agency’s qualification.

Recommendations

The recommendations are based on the findings from fieldwork at the selected agencies, but are likely to be relevant to other Australian Government agencies. Therefore, all agencies are encouraged to assess the benefits of implementing the recommendations in light of their own circumstances.

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.15 |

To strengthen security assurance and monitoring arrangements, the ANAO recommends that agencies implement a security assurance strategy that outlines their approach to monitoring:

ACC’s response: Agree. AGD’s response: Supported. GA’s response: Accepted. Mint’s response: Agree. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.25 |

To assist agencies to adopt and maintain an effective approach to the management of physical security risks, the ANAO recommends that agencies, in the context of their discrete operating circumstances:

ACC’s response: Agree. AGD’s response: Supported. GA’s response: Accepted. Mint’s response: Agree. |

Footnotes

[1] Based on Attorney‑General’s Department, Overarching protective security policy statement, located at: <http://www.protectivesecurity.gov.au/pspf/Pages/Overarching‑protective‑security‑policy‑statement.aspx> [Date accessed: 30 April 2014].

[2] The protective security principles are shown in Appendix 2. The earlier Protective Security Manual (PSM) adopted a more compliance‑based approach.

[3] The PSPF applies to all Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) agencies, and to those Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) bodies that have received a Ministerial Direction. This arrangement is currently being reviewed following the passage of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), which, at the time of preparation of this report, is planned to take effect on 1 July 2014 and replace the FMA and CAC Acts. The PGPA Act removes the distinction between FMA Act agencies and CAC Act bodies, and introduces two broad categories of Australian Government entities (non‑corporate and corporate Commonwealth entities) and the category of Commonwealth companies. Under section 21 of the PGPA Act, non‑corporate Commonwealth entities must be governed in a way that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Australian Government, including the PSPF, whereas corporate Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies do not have to apply Australian Government policies, including the PSPF, unless the Finance Minister issues a Government Policy Order under sections 22 or 93 of the Act.

[4] Attorney‑General’s Department, Physical security management protocol, July 2011, p.1, available at: <http://www.protectivesecurity.gov.au/physicalsecurity/Documents/PHYSEC%20Protocol%20‑%20V1.4%20‑%20as%20approved%2018%20July%202011%20‑%20amended%20July%202013.pdf>. [Date accessed: 23 August 2013].

[5] Agencies were required to report their compliance with the PSPF’s mandatory requirements to their portfolio Minister, the Secretary of the Attorney‑General’s Department and the Auditor‑General.

[6] The term ‘governance’ is used in the PSPF to describe the group of mandatory requirements designed to help ensure that agencies have the foundation elements necessary to meet the Government’s protective security policy standards and expectations. The four governance requirements not addressed in the audit were GOV 9, GOV 10, GOV 11 and GOV 13 as they relate, respectively, to: providing guidance to employees and contractors on certain sections from the Crimes Act 1914, the Criminal Code 1995, the Freedom of Information Act 1982 and the Privacy Act 1988; compliance with multilateral or bilateral agreements; business continuity management; and fraud control.

[7] The Information Security Manual (ISM) produced by the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) is the standard which governs the security of government ICT systems. The ISM is available from <http://www.asd.gov.au/infosec/ism/index.htm>. [Date accessed: 19 May 2014].

[8] ANAO, Audit Report No.50 2013–14, Cyber Attacks: Securing Agencies’ ICT Systems.

[9] See Table 1.1 for a listing of the previous ANAO recommendations examined in this audit.

[10] Attorney‑General’s Department, Protective Security Policy Framework, June 2013, p.2, available at: <http://www.protectivesecurity.gov.au/pspf/Documents/Protective%20Security%20Policy%20Framework%20‑%20amended%20June%202013.pdf>. [Date accessed: 23 August 2013].

[11] The ANAO downgraded the agencies’ self‑assessment ratings in 14 instances—in one case at GA the ANAO considered the agency’s self‑assessment rating of ‘compliant’ to be ‘non‑compliant’, in 12 cases (nine at the ACC and three at GA) the ANAO considered ratings of ‘compliant’ to be ‘partially compliant’ and in one case at GA, the ANAO considered a rating of ‘partially compliant’ to be ‘non‑compliant’. The ANAO also upgraded one self‑assessment rating at GA—from ‘partially compliant’ to ‘compliant’—to reflect improvements made by GA since September 2013.

[12]AGD, PSPF, op. cit., p. 3.

[13] PSPF mandatory requirement GOV 2.

[14] PSPF mandatory requirement GOV 3.

[15] PSPF mandatory requirement GOV 7.

[16] AGD, Protective Security Governance Guidelines: Compliance Reporting, March 2012, pp. 10–11.

[17] PSPF mandatory requirements PHYSEC 3 and PHYSEC 4.

[18] PSPF mandatory requirement GOV 6.

[19] PSPF mandatory requirements GOV 6, PHYSEC 5 and PHYSEC 7.

[20] PSPF mandatory requirements GOV 4, GOV 5 and PHYSEC 1.

[21] PSPF mandatory requirement GOV 1.

[22] Completion rates of security awareness training at the Mint, GA and at the ACC were 98 per cent, 96 per cent and 87 per cent respectively.