Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Design and Implementation of the Community Development Programme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the transition of the Remote Jobs and Communities Programme to the Community Development Programme, including whether the Community Development Programme is well designed and administered effectively and efficiently.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Community Development Programme (CDP) is an Australian Government employment and community development program designed to support jobseekers and reduce welfare dependency in remote Australia. The CDP commenced on 1 July 2015, replacing the Remote Jobs and Communities Program (RJCP).1 The key objectives of the CDP are increasing: workforce participation and improving job opportunities; sustainable work transitions; and employability in remote communities.

2. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) is responsible for the overall design and administration of the CDP; however some aspects of the CDP are administered by other Australian Government entities. Of the 33 000 jobseekers in the CDP, more than 80 per cent of these jobseekers identify as Indigenous. Currently, 40 third-party providers deliver employment services to CDP jobseekers, of which 65 per cent are Indigenous organisations. Total expenditure is estimated to be $1.6 billion over four years from 2014–15 to 2017–18.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the transition of the Remote Jobs and Communities Program to the Community Development Programme including whether the Community Development Programme was well designed and administered effectively and efficiently. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Sound analysis and advice informed the design of the Community Development Programme and transition from the Remote Jobs and Communities Program.

- The Community Development Programme was effectively and efficiently administered.

- Performance was appropriately monitored and outcomes were measured, reviewed and reported to the Minister.

Conclusion

4. The transition from the RJCP to the CDP was largely effective. The CDP was supported by stakeholder consultation, as well as risk management and evaluation frameworks. In addition, PM&C has strengthened its approach to monitoring and responding to compliance issues impacting on provider payments. There would be scope to review the incentives created by the revised provider payment structure.

5. The implementation of the CDP was supported by an external review of Indigenous Training and Employment, stakeholder engagement, and an effective communication strategy. However, the design of the CDP was not informed entirely by sound analysis of the RJCP.

6. The timeframes in which the RJCP was transitioned to the CDP impacted on the ability of providers to understand the changes prior to implementation. In addition, PM&C did not have arrangements in place to ensure funding commitments made by providers from their RJCP Participation Accounts met program requirements. Finally, aspects of the revised provider payment structure may reduce provider incentives to transition jobseekers into ongoing employment.

7. PM&C has established appropriate governance, key program frameworks and guidance material to assist in the administration and delivery of the CDP. PM&C has also strengthened its approach to compliance and fraud prevention in light of identified program risks.

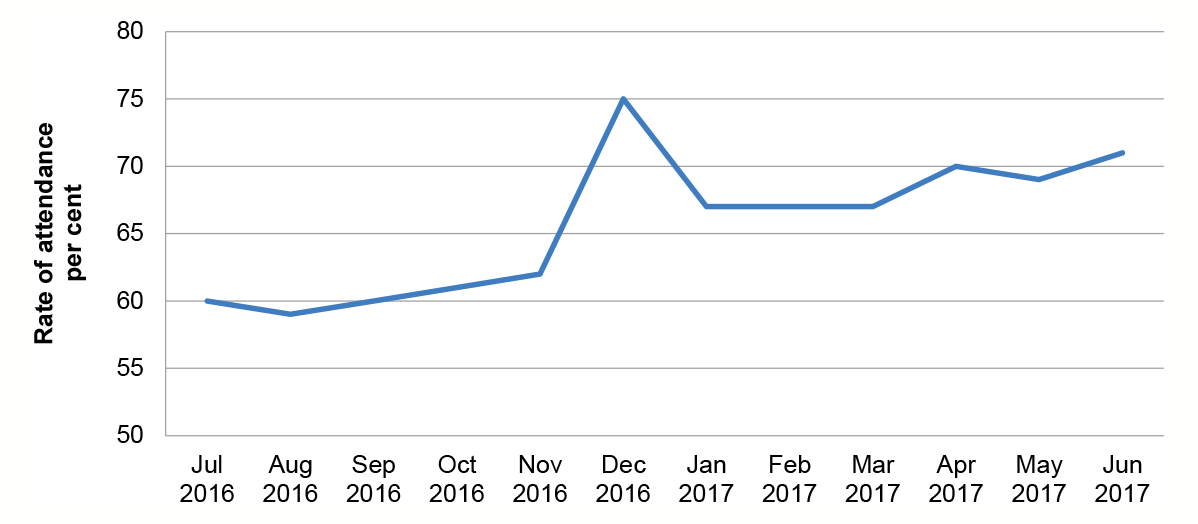

8. PM&C has established transparent performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for CDP providers. These performance indicators are measurable and linked to the CDP’s policy objectives, and have shown improvements in terms of 13 and 26 week employment outcomes; as well as aggregate hours of attendance by participants.

9. PM&C established complementary policies—the Employer Incentive Fund and the Indigenous Enterprise Development fund—aimed at addressing gaps in regional labour markets. However, these programs were significantly undersubscribed. In addition, there is scope to improve the targeting of funding to remote areas by monitoring the number of businesses created to better integrate the CDP Funding Arrangements with related policies.

10. PM&C has developed and implemented a program evaluation strategy for the CDP; however the timing of the review was not aligned to the Government’s consideration of further funding in the 2017–18 Budget.

Supporting findings

Design and transition

11. PM&C’s design of the CDP was supported by an analysis of the Review of Indigenous Training and Employment (the Forrest Review) and consultation across Government. In addition, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs consulted with employers, community councils, the Indigenous Advisory Council and representative bodies on the design of the CDP.

12. However, changes introduced as part of the CDP were not informed entirely by a sound evidence base. In particular, the review of the CDP’s predecessor program, the RJCP, was based on incomplete analysis of the data. In addition, there would be scope for PM&C to consider the incentives created by the revised provider payment structure, and its alignment with the underlying policy objectives of the program changes.

13. PM&C developed a suitable phased transition and implementation plan, and communication strategy, to support the transition to the CDP. Due to the short implementation timeframes, many of the risks identified by PM&C materialised. In particular, the timeframes reduced the opportunity for providers to understand the substantial changes prior to implementation. While providers were authorised to access their Participation Accounts to facilitate the transition to the CDP, PM&C did not have arrangements in place to appropriately ensure commitments from the Participation Accounts met the program requirements. Four months following the introduction of the CDP, only 37 per cent of regions were on track to meet performance targets.

Administration of the Community Development Programme

14. PM&C has established appropriate governance frameworks and guidance material to assist the administration and delivery of the CDP. There are appropriate administrative arrangements in place between the relevant Australian Government entities responsible for delivering the CDP.

15. It is too early to assess whether the CDP is administered efficiently. The CDP is administered by entities at a higher unit cost than the RJCP and the broader jobactive employment services program.

16. PM&C has developed a fit-for-purpose risk management strategy to support the administration of the CDP. In late 2016, PM&C integrated its approach to risk management across the broader Indigenous Affairs Group grants program, which included the CDP. PM&C also established provider risk plans and assessments. However, some key program risks were either not identified in the program level risk plan, or were not fully addressed by mitigation strategies.

17. PM&C has developed a suitable compliance framework for both jobseekers and providers under the CDP. Given the inherent risks associated with issuing payments based on provider-reported data, PM&C has now strengthened its approach to identifying and pursuing suspected instances of non-compliance by providers.

18. PM&C has implemented suitable arrangements to support the administration of provider funding under the CDP. There would be scope to adopt a more transparent and systematic approach to making ancillary payments.

19. PM&C consults with key stakeholders on potential changes to the CDP. The level of engagement between CDP providers, and employers and communities, varied across the 60 regions in which the CDP was implemented.

Monitoring and reporting on CDP performance and outcomes

20. PM&C has established transparent and effective arrangements for measuring the performance of the CDP. Appropriate tailored approaches have been developed to suit delivery across the regional network.

21. PM&C regularly monitors and reports to its Minister on provider performance. While the basis of performance assessment and reporting is set out in provider agreements, there would be scope for greater transparency on the calculation of the Regional Employment Targets.

22. PM&C administers the Employer Incentive Fund to stimulate employment; however, only a small proportion of eligible employers have received the incentive payment. Similarly, there was minimal use of the Indigenous Enterprise Development funds to support the establishment of Indigenous business in CDP regions, resulting in a substantial underspend of allocated funding.

23. PM&C’s evaluation strategy was developed late, some seven months after the CDP commenced and an overview of the evaluation strategy was not agreed by the Minister for Indigenous Affairs until 7 April 2016. This reduced the scope to collect data that was capable of informing an evaluation of the CDP’s impacts.

24. The evaluation strategy was not peer reviewed by a reference group. Evaluation strategy milestones were not consistent with Government timeframes for considering ongoing funding of the CDP.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.27

The ANAO recommends the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet review the Community Development Programme provider payment structure, particularly the incentives it creates and its alignment with the underlying policy objectives of the program changes.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

25. The departments of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Employment and Human Services’ summary responses to the proposed report are provided below, with full responses at Appendix 1.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

The Department welcomes the audit’s overall conclusions and findings. The Department is pleased that the ANAO found that the transition from the Remote Jobs and Communities Programme to the Community Development Programme (CDP) was largely effective and supported by stakeholder consultation, risk management and evaluation frameworks. The Department appreciates the audit’s acknowledgement that we have established appropriate governance, key program frameworks and guidance material to assist in the administration and delivery of the CDP.

The Department is taking steps to consider and address the areas of potential improvement raised by the ANAO, in particular strengthening guidance on ancillary payments and ensuring the provider payment model aligns with the program’s core objectives of assisting job seekers into long-term employment. This includes through the department’s ongoing programme implementation and design work, supported by a continual focus on provider performance, which is lifting job seeker outcomes. The Department is also committed to improving evaluation efforts and building the evidence base for Indigenous policies and programmes.

The Government has also announced its intent to consult on a new remote employment and participation model, which will better tailor welfare arrangements. These audit findings will also inform this consultation process.

Department of Employment

The Department acknowledges the audit’s conclusions and findings. The Department notes the report’s observation that the changes to the Job Seeker Compliance Framework announced in the 2017−18 Budget will not apply to the Community Development Programme.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) notes this report and that the ANAO has concluded that the administrative arrangements in place between the department and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet are appropriate.

Key learnings for all Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Commonwealth entities in designing and implementing policy.

Policy design

Implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 As part of the Australian Government’s mutual obligation requirements2 for receipt of certain income support payments3, jobseekers must fulfil a range of requirements, such as looking for work and participating in activities that will improve their employment prospects and reduce reliance on income support payments. In 2016–17, the Government committed in excess of $2 billion to fund employment services in Australia to support jobseekers into employment.

1.2 In May 2017, the unemployment rate in remote regions4 of Australia was 6.6 per cent compared to the national average of 5.5 per cent, with a corresponding youth unemployment rate (15–24 years old) of 18.6 per cent compared to the national average of 12.7 per cent. The unemployment rate was also higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in remote areas compared to those in non-remote areas.5

What is the Community Development Programme?

1.3 The Community Development Programme (CDP) is an Australian Government employment and community development service designed to reduce welfare dependency in remote Australia, by improving labour markets, increasing workforce participation, increasing skills and facilitating sustainable work transitions for jobseekers.

1.4 To participate in the CDP, a jobseeker must be on income support, live in a designated remote region and meet certain criteria, as shown in Table 1.1. Those eligible for the CDP who have mutual obligation requirements as part of their income support payment (for example, Newstart Allowance or Youth Allowance) are required to participate in the CDP.

Table 1.1: Eligibility for the Community Development Programme

|

Individual circumstances |

Additional information |

|

Fully eligible |

|

|

Newstart Allowance |

Are subject to mutual obligation requirements. |

|

Youth Allowance (Other) |

|

|

Disability Support Pension |

Can be subject to mutual obligation requirements. Jobseekers not subject to mutual obligation requirements may be registered to participate. |

|

Parenting Payment |

|

|

Other Income Support payments |

|

|

Partial Capacity to Work and not on income support |

Identified as having a disability and a partial capacity to work via an Employment Services Assessment. |

|

Young person (aged 15–21) and not on income support |

Not employed for more than 15 hours a week or in full-time education. |

|

Pre-release prisoners |

Approved day or partial release prisoners referred by their correctional institution to engage in paid work through a work-release program. |

|

Restricted eligibility |

|

|

Vulnerable young persons (aged 15-21) and are full-time students |

Eligible to participate only if they presented to a CDP provider in crisis and had at least one serious non-vocational barrier. |

Source: ANAO analysis based on the departments of Human Services and PM&C documentation.

1.5 Those jobseekers aged between 18 and 49 years, who are receiving the full rate of income support, are not exempt from mutual obligation requirements, and are not otherwise disqualified by illness, injury or disability, are required to participate in Work for the Dole activities.6

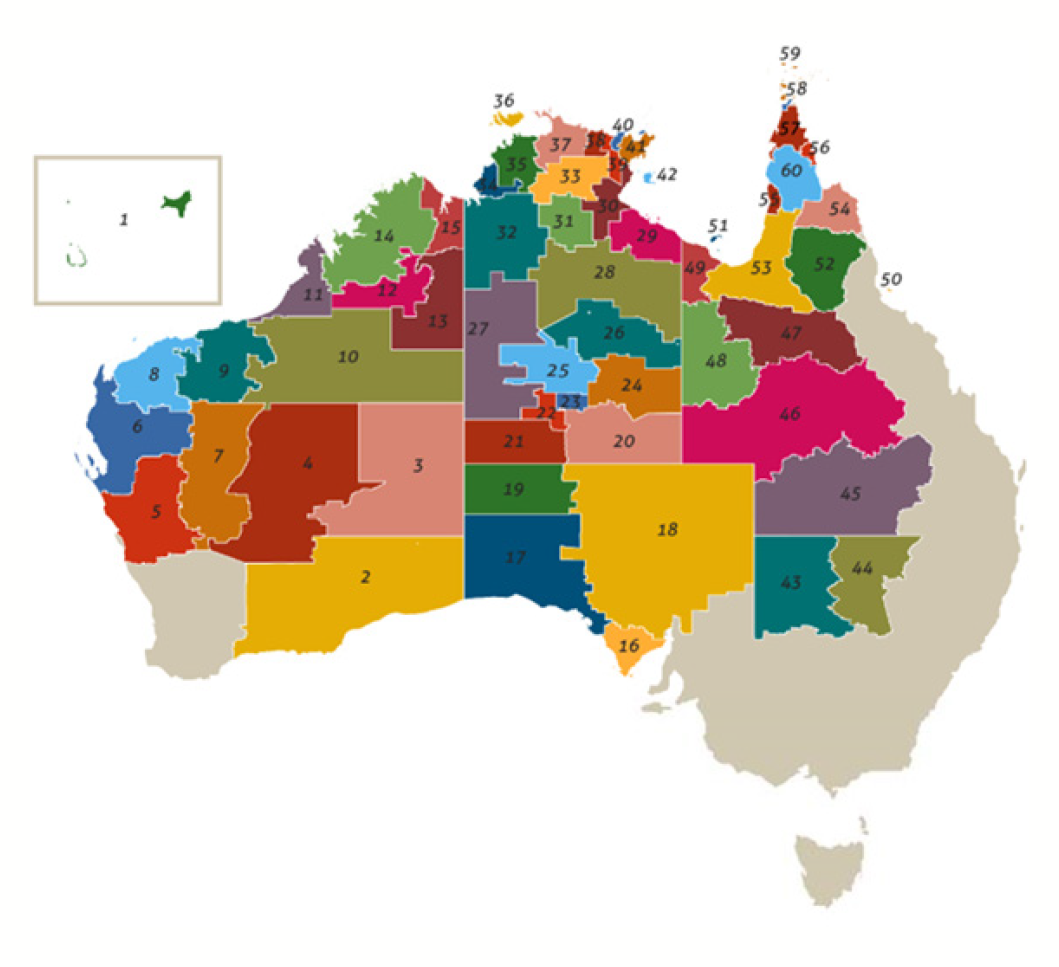

1.6 Participation in the CDP is not specific to Indigenous peoples; however, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people comprise more than 80 per cent of the CDP caseload. The CDP is delivered across 60 designated remote regions7 to more than 1000 communities in Australia, as shown in Figure 1.1. Eligible jobseekers outside these regions are serviced by jobactive (administered by the Department of Employment) or Disability Employment Services (administered by the Department of Social Services).8

Figure 1.1: Overview map of the 60 Community Development Programme regionsa

Note a: See Appendix 2 for supporting information on the regions.

Source: PM&C information.

1.7 CDP employment services in these remote regions are delivered by third-party providers (providers). There is generally one provider per region9 with some organisations providing services for multiple CDP regions. As at April 2017, PM&C reported that, of the 40 CDP providers, 65 per cent were Indigenous organisations.

1.8 CDP providers deliver two types of services on behalf of the Government.

- Basic Services: including integrated case management and supporting jobseekers to find and keep a job.

- Remote Employment Services: including establishing and administering Work for the Dole—work-like activities, which jobseekers must participate in five days a week, depending on their assessed capacity. These work-like activities were to reflect local employment opportunities or be relevant to community aspirations and needs.

1.9 The total number of jobseekers on the remote employment services caseload fluctuates over the course of the year. As at 22 May 2017, there were 33 152 jobseekers in the total CDP caseload, consisting of 17 569 Work for the Dole jobseekers and 15 583 Basic Service jobseekers.

2015 changes to remote employment services

1.10 The CDP commenced on 1 July 2015, replacing the Remote Jobs and Communities Program (RJCP).10 The introduction of the CDP saw a range of changes aimed at increasing workforce participation, providing employment pathways to long term employment outcomes, and reducing administrative burden for providers.

1.11 Table 1.2 outlines the key differences between the RJCP and the CDP.

Table 1.2: Key differences between the Remote Jobs and Communities Program and the Community Development Programme

|

Program element |

Remote Jobs and Communities Program |

Community Development Programme |

|

Participation activities |

Provider discretion for jobseekers to participate in work-like and community participation activities and training for jobseekers to fulfil their mutual obligation requirements. |

For those required to participate in Work for the Dole—Work for the Dole Activities. |

|

Participation requirements |

Based on capacity assessment, jobseekers between 15 to 65 years participate—up to 50 hours per fortnight—in an activity. Grandfathered Community Development and Employment Projects (CDEP) participants participate for sufficient hours to earn or be paid the applicable CDEP Wage Rate.a |

Continuous Work for the Dole (up to 25 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, with leave provisions of up to six weeks per year and exemptions for cultural business) for all adults 18 to 49 years of age—not in work or study, up to their full activity tested capacity to work. |

|

Payment modelb |

More than a dozen different provider payments including for: delivery of activities; education outcomes; job placements; and employment outcomes. Providers also had access to a Participation Account for selected ancillary payments to assist jobseekers, for example, to purchase clothing, equipment and for training. |

Payment model structured in three payment categories: Basic Services; delivery of Work for the Dole activities; and achieving employment outcomes. Employers could receive an Employer Incentive Payment. Payments linked to jobseeker engagement and providers’ efforts to follow up with the jobseeker. |

|

Additional funding |

Community Development Fund ($237.5 million over five years) projects to support social and economic participation for jobseekers including participation in work-like activities and job opportunities. |

Annual grants of up to $25 million for Indigenous Enterprise Development remote projects to establish enterprises that benefit communities and create opportunities for jobseekers to satisfy their mutual obligation requirements in a business environment. |

Note a: Under CDEP, participants received a payment (expressed as a fortnightly rate) for participating in Remote Employment and Participation Activities. The CDEP Wage Rate at 1 July 2013 was $217.71 (GST exclusive) per week for a CDEP Youth Participant and $287.57 (GST exclusive) for all other CDEP Scheme Participants.

Note b: See Appendix 3 for further detail on the CDP and the RJCP payment models.

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C documentation.

Administrative arrangements

Roles and responsibilities

1.12 PM&C is responsible for the overall administration of the CDP, including policy advice, and program design and management. A number of other Australian Government entities administer relevant legislation and aspects of CDP delivery.

1.13 Table 1.3 outlines the relevant responsibilities of each of the entities in regards to the CDP.

Table 1.3: Australian Government entities’ responsibilities for the Community Development Programme

|

Function |

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

Department of Human Services |

Department of Employment |

Department of Social Services |

|

Legislation |

n/a |

n/a |

Social Security (Administration) Act 1999—in so far as it relates to activity test requirements and compliance obligations for participation payment recipients. |

Social Security (Administration) Act 1999—in so far as it relates to capacity assessments and income support payments. |

|

Policy |

Community Development Programme. Employment Services Assessment (policy responsibility shared between the departments of Social Services, the Prime Minister & Cabinet and Employment). |

n/a |

Job Seeker Compliance Framework. Employment Services Assessment (policy responsibility shared between the departments of Social Services, the Prime Minister & Cabinet and Employment). |

Income support payments. Job Capacity Assessments. Employment Services Assessment (policy responsibility shared between the departments of Social Services, the Prime Minister & Cabinet and Employment). |

|

Operations |

Provider contract management and monitoring. Guidance material. |

Jobseeker income support delivery. |

Assess financial viability of Community Development Programme providers, as per the Memorandum of Understanding with the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet. |

n/a |

|

Systems (IT) |

n/a |

Customer First/ Process Direct (system for administering income support). |

Employment Services System (system for Community Development Programme providers’ case management and reporting) |

n/a |

|

Paymentsa |

Providers’ payments (for example, Work for the Dole payments, employment outcome payments, and ancillary payments). |

Jobseekers’ income support payments. |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Compliance action |

Provider compliance action. |

Jobseeker compliance decisions.b |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Support tools for case management |

Monitor provider use of tools (e.g. Job Seeker Classification Instrument) and links to other programs.c |

Employment Services Assessment (delivery). Job Capacity Assessments (delivery). Job Seeker Classification Instrument (delivery). |

Job Seeker Classification Instrument (policy owner). |

Employment Services Assessment (policy owner). |

|

Data ownership |

Related to the administration of the Community Development Programme (primarily as it relates to employment services delivered by service providers). |

n/a |

Verifying and releasing data related to the Job Seeker Compliance Framework. |

Income support payments/recipient circumstances. |

|

Feedback, review and appeal |

n/a |

Jobseeker review and appeal. |

Complaints (National Customer Service Line). |

n/a |

|

Reporting |

Community Development Programme outcomes and performance, including evaluation. |

n/a |

n/a |

Income support. |

Note a: See Appendix 3 for further detail on the CDP payment model.

Note b: CDP providers report jobseeker non-compliance to the Department of Human Services (which triggers initial payment suspension and jobseeker contact), Human Services investigates non-compliance and decides whether the non-compliance applied, with any penalties applied as prescribed by legislation.

Note c: For example, the Skills Education and Employment Programme and the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

Source: ANAO.

Funding

1.14 In the 2015 changes to remote employment services, the Government redirected existing RJCP funding of $1.5 billion over four years from 2014–15 and provided an additional $94.9 million in funding for the CDP.11 Table 1.4 sets out total funding allocations for all relevant entities for the CDP, 2014–15 to 2017–18.

Table 1.4: Community Development Programme funding allocations for the period 2014–15 to 2017–18

|

Entity |

2014–15 ($million) |

2015–16 ($million) |

2016–17 ($million) |

2017–18 ($million) |

Total ($million) |

|

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

278.2 |

347.4 |

406.1 |

385.9 |

1417.6 |

|

Department of Employment |

3.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

3.2 |

|

Department of Social Services |

16.8 |

64.3 |

63.5 |

39.8 |

184.3 |

|

Department of Human Services |

1.0 |

0.7 |

-1.0 |

-2.5 |

-1.7 |

|

Total |

299.2 |

412.4 |

468.6 |

423.2 |

1603.4 |

Note: Total may differ due to rounding.

Source: PM&C data.

1.15 No separate departmental funding was appropriated for the CDP for the departments of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Human Services. The Department of Employment was allocated up to $3.2 million in departmental funding to deliver IT systems.

Audit approach

1.16 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the transition of the Remote Jobs and Communities Program to the Community Development Programme including whether the Community Development Programme was well designed and administered effectively and efficiently.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Sound analysis and advice informed the design of the Community Development Programme and transition from the Remote Jobs and Communities Program.

- The Community Development Programme was effectively and efficiently administered.

- Performance was appropriately monitored and outcomes were measured, reviewed and reported to the Minister.

Audit methodology

1.18 The audit methodology included:

- the examination and analysis of documentation relating to the design and implementation and risk management arrangements for the Community Development Programme;

- interviews with key officials in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Department of Employment, and the Department of Human Services; and

- interviews with, and surveys of, key external stakeholders including: Community Development Programme providers; relevant regional and remote employers; state and territory Government entities responsible for delivering related Indigenous programs; community organisations; and peak bodies such as Jobs Australia.

1.19 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $547 000.

1.20 The team members for this audit were Sandra Dandie, Megan Beven, Barbara Das, Shickam Saouna, Donna Burton and Andrew Rodrigues.

2. Design and transition

Areas examined

This chapter examines the policy design, stakeholder consultation and communication strategy that informed the transition from the RJCP to the CDP.

Conclusion

The implementation of the CDP was supported by an external review of Indigenous Training and Employment, stakeholder engagement, and an effective communication strategy. However, the design of the CDP was not informed entirely by sound analysis of the RJCP.

The timeframes in which the RJCP was transitioned to the CDP impacted on the ability of providers to understand the changes prior to implementation. In addition, PM&C did not have arrangements in place to ensure funding commitments made by providers from their RJCP Participation Accounts met program requirements. Finally, aspects of the revised provider payment structure may reduce provider incentives to transition jobseekers into ongoing employment.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO recommended PM&C review the CDP payment structure to ensure it aligns with the underlying policy objectives of the program changes.

Was the design of the Community Development Programme informed by sound analysis, advice and consultation?

PM&C’s design of the CDP was supported by an analysis of the Review of Indigenous Training and Employment (the Forrest Review) and consultation across Government. In addition, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs consulted with employers, community councils, the Indigenous Advisory Council and representative bodies on the design of the CDP.

However, changes introduced as part of the CDP were not informed entirely by a sound evidence base. In particular, the review of the CDP’s predecessor program, the RJCP, was based on incomplete analysis of the data. In addition, there would be scope for PM&C to consider the incentives created by the revised provider payment structure, and its alignment with the underlying policy objectives of the program changes.

2.1 Implementation of the Remote Jobs and Communities Program (RJCP) commenced on 1 July 2013, with the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations as the responsible entity. Following the September 2013 Machinery-of-Government changes, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) assumed policy and program responsibility for a range of the Australian Government’s Indigenous initiatives, including the RJCP and its successor, the Community Development Programme (CDP). A timeline of these key events is set out in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Timeline of key milestones and events in the establishment and implementation of the Remote Jobs and Communities Program and the Community Development Programme from 2013 to 2018

Source: ANAO analysis.

Decision to change the Remote Jobs and Communities Program

2.2 Between November 2013 and December 2014, the Government decided on changes to the RJCP. Broadly, these changes were aimed at:

- addressing a number of emerging design and implementation issues with the RJCP model12;

- aligning remote employment services with broader welfare reforms and changes to the mainstream employment services; and

- ensuring people in remote communities were ‘engaged in training that leads to real jobs or participating in activities that benefit their communities’.

2.3 The Government’s decision to change the RJCP occurred in the context of broader changes to the mainstream employment services model, jobseeker mutual obligations requirements, and the Review of Indigenous Training and Employment (the Forrest Review).13 The changes introduced through the CDP would ultimately form part of the Government’s response to the Forrest Review.14

2.4 PM&C’s advice to Government supported the decision to change the RJCP based on the program’s performance outcomes. In particular, PM&C’s advice noted that, under the RJCP model, only around a third of remote jobseekers were engaged in any form of Structured Activities.15

2.5 Under the RJCP, participants could meet their mutual obligation requirements by participating in one or more ‘employment and participation activities’16, consistent with their individual participation plan (which was required to be developed for each jobseeker). Structured Activities were only one type of activity jobseekers could be engaged in and, as such, PM&C’s analysis did not take into account those jobseekers engaged in other agreed employment and participation activities, such as accredited training or Remote Youth Leadership and Development Corps activities.17

2.6 As at December 2014, if all RJCP agreed activities were taken into consideration, around 65 per cent of RJCP jobseekers were participating in RJCP agreed activities.

2.7 Additionally, in October 2014, PM&C also advised Government that under the RJCP there had been a significant reduction (90 per cent) in jobseekers achieving employment that lasted more than 26 weeks since the commencement of the RJCP compared to the previous year’s employment outcomes under the Job Services Australia model in remote areas. PM&C was unable to provide evidence to the ANAO to support this advice.

Consultation on changes to the remote employment services model

2.8 The decision to change the RJCP and the subsequent design of the CDP was informed by consultation and submissions received from relevant stakeholders, including communities, employers, Indigenous leaders and community organisations; and Government departments and agencies, as part of the Review of Indigenous Training and Employment (the Forrest Review).

2.9 The Minister for Indigenous Affairs (Minister), supported by PM&C, convened several roundtable meetings with selected employers and community councils in September 2014 to discuss the findings of the Forrest Review, including aspects relevant to the design of the CDP. In October 2014, the Minister also consulted with the Indigenous Advisory Council members18 on the merits of the CDP, as well as Jobs Australia19 and a selection of trusted providers. In April 2015, PM&C consulted Jobs Australia on elements of the CDP design.

Design of the Community Development Programme

2.10 The changes to remote employment services took effect from 1 July 2015, and formed the basis of the CDP. Key changes included20:

- all adults between 18 and 49 years of age, not in work or study, would undertake a routine of full-time Work for the Dole activity—up to 25 hours across a five day week, 52 weeks a year (‘Continuous’ Work for the Dole);

- a greater emphasis on ‘work-like activities’ that provided a service to community and full-time work experience for jobseekers;

- the establishment of new enterprises in remote communities through the provision of grants under the existing Indigenous Advancement Strategy;

- changes to incentives for providers and employers;

- simplified processes for providers aimed at reducing administrative burden; and

- a requirement for providers to immediately notify the Department of Human Services of jobseeker non-compliance to better support remedial action.

‘Continuous’ Work for the Dole

2.11 The inclusion of ‘continuous’ Work for the Dole in the design of the CDP was consistent with Government policy21 and the introduction of Work for the Dole in mainstream employment services. Under jobactive, the mainstream employment service, jobseekers were required to participate in Work for the Dole, or another approved activity, for six months each year.22

2.12 In its advice to Government, PM&C proposed that Work for the Dole participation requirements should vary from the mainstream income support payment participation requirements. PM&C noted that implementing Work for the Dole for only six months of each year would not work in remote communities which often had virtually non-existent labour markets and where there was a need to establish social norms. Consequently, PM&C advised that ‘only a comprehensive full time Work for the Dole program applied to all jobseekers will work in remote regions’. ‘Continuous’ Work for the Dole activities was also considered a key factor in reducing the ‘high level of idleness in communities’.

2.13 The Government agreed that the ‘continuous’ Work for the Dole component of the CDP would be implemented as a trial until 30 June 2018, with the outcome of the evaluation of the CDP’s effectiveness to inform further advice to Government in late 2016.

Work-like activities

2.14 As part of the CDP’s ‘continuous’ Work for the Dole component, providers were expected to deliver a mix of ‘work-like’ activities that set a daily routine for jobseekers across a five day, Monday to Friday week. Providers could either deliver the activities themselves or through a hosted placement with an employer.23

- The CDP guidelines provided greater flexibility in what constituted a Work for the Dole activity, to drive creativity and allow providers to design activities that best met community wants and needs.24

- Around 16 per cent of Work for the Dole jobseekers were expected to be in hosted placements. Host organisations would receive a payment for the costs of hosting a jobseeker, with PM&C recommending providers split the Work for the Dole service payment25 50-50 with the host organisation. This arrangement was intended to maintain the incentives for providers to move jobseekers into hosted places.26

2.15 PM&C advised the Government that an additional $96 million over the forward estimates was required to ensure the quality of the work-like activities to be delivered, based on PM&C’s estimates of the likely caseload.27 The additional funding was sourced through the new National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing.28 This was agreed to by Government on the basis that the CDP could be used to support remote housing delivery.29

Indigenous Enterprise Development

2.16 In December 2014, the Government announced $25 million in funding to support the establishment of local enterprises, and in so doing help build remote labour markets.30 The funding would be limited to one to two years, with enterprises required to have a plan in place to become commercially sustainable. In addition, jobseeker placements would be limited to 12–24 months to ensure the placement represented a path to ongoing employment and to reduce the displacement of existing jobs.

2.17 In early 2015, PM&C engaged a private consultancy firm to support the initial design of the operation of the remote intermediate labour markets. This design work ultimately formed the basis of the Indigenous Enterprise Development (IED). Funding decisions under the IED were covered by the Indigenous Advancement Strategy guidelines31 and assessed on the extent to which applicants would ‘… provide employment and hosted placement opportunities for the CDP jobseekers’.

CDP payment model

2.18 The transition to the CDP saw significant changes to provider payments, with greater emphasis placed on employment outcomes.32 Additionally, the provider Participation Account33 that had existed under the RJCP, would cease to operate under the CDP.

2.19 From 1 July 2015, payments to providers to deliver the CDP included the:

- Basic Services payment—payable for delivering Basic Services to jobseekers not required to participate in Work for the Dole activities.

- Work for the Dole payment—payable for delivering both Basic Services and Work for the Dole activities.

- Employment Outcome payment—payable where a jobseeker was still employed after 13 and 26 consecutive weeks (with an allowable break34) of employment and designed to encourage providers to support jobseekers into employment and ensure they stayed in employment.

- Employer Incentive Fund payment—a payment passed onto employers from providers if a jobseeker achieved a 26 week employment outcome.

2.20 CDP funding agreements also provided for two other payments:

- The ancillary payments—the purpose of these payments were not specified in the Funding Agreement or other guidance; and

- Funding to strengthen organisational governance—payable to providers who became incorporated (where required) under the Funding Agreement.

2.21 The CDP payment model was designed to strengthen incentives for providers to place jobseekers into work; however concerns were raised prior to its implementation that ‘there is little, if any incentive (at a financial risk for them) for a provider to place a Work for the Dole participant into a job’.

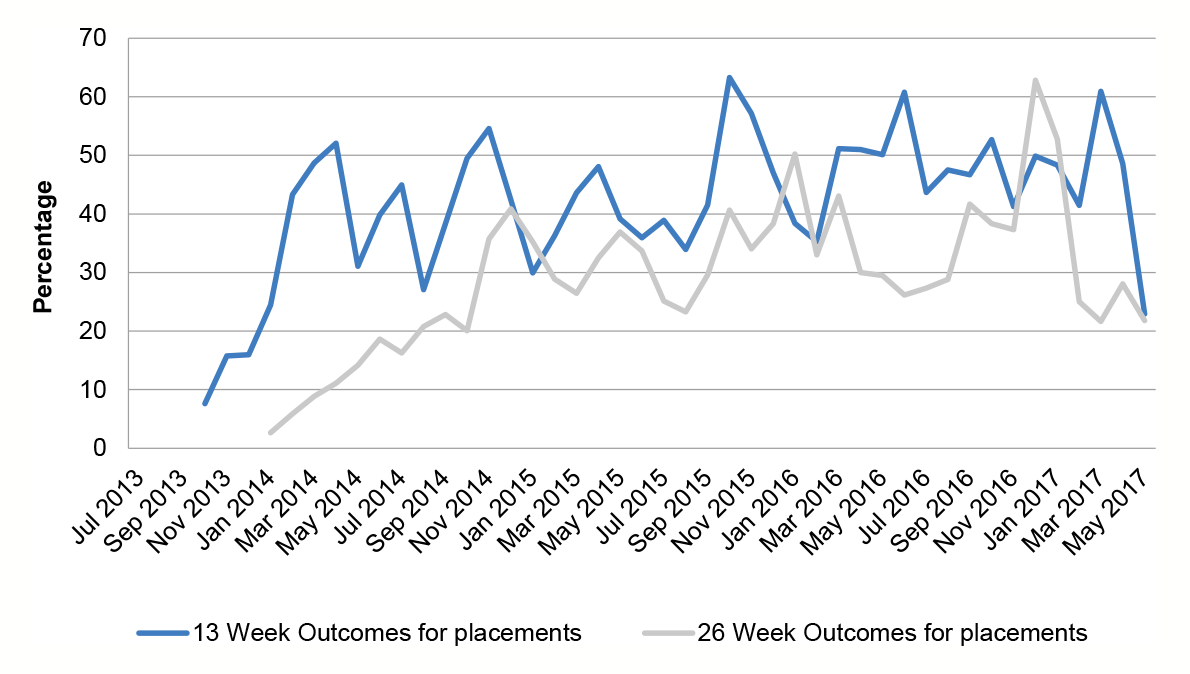

2.22 Pursuant to the changes introduced to the payment model in transitioning from the RJCP to the CDP, the Employment Outcome payment providers received for a full-time jobseeker increased from $6325 to $7500 (GST exclusive).35 ANAO analysis showed that although the financial incentive had increased overall, there was a lower probability a provider would receive that payment as:

- under the CDP, Employment Outcome payments were weighted towards 26 weeks, compared to the RJCP where the providers received a proportion of the payment at more regular intervals (as shown in Table 2.1);

- under the CDP, there was an increased risk to the provider given that the jobseeker may not have achieved a 13 or 26 week outcome payment, with only 40 per cent of job placements achieving 26 week outcomes (as shown in Table 2.2).

2.23 Given the more stringent timing requirements, and inherent uncertainty in achieving the 13 and 26 week employment outcomes, the revised payment system may dilute the incentives for providers to place jobseekers in work, as opposed to continuing their engagement in ‘work-like activities’ pursuant to Work for the Dole arrangements.

Table 2.1: Comparison of the Remote Jobs and Communities Program and the Community Development Programme Employment Outcome Payments

|

Payment interval |

Remote Jobs and Communities Program |

Community Development Programme |

||

|

|

Amount ($) |

Proportion of total payment (%) |

Amount ($) |

Proportion of total payment (%) |

|

Job placement |

550 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

|

7 week |

825 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

|

13 week |

2 475 |

39 |

2 250 |

30 |

|

26 week |

2 475 |

39 |

5 250 |

70 |

|

Total |

6 325 |

100 |

7 500 |

100 |

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C documentation.

Table 2.2: Community Development Programme job placements, and employment outcomes at 13 weeks and 26 weeks, 1 July 2015 to 30 April 2017

|

|

Outcomes |

Proportion of job placements which achieved an outcome (%) |

|

Job placements |

12 226 |

n/a |

|

13-week employment outcomes |

6 544 |

54 |

|

26-week employment outcomes |

4 915 |

40 |

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C data.

2.24 Additionally, the timeframe within which an employment outcome could be achieved was reduced. For example, under the RJCP model a 26 week outcome would be achieved when a jobseeker had been employed for 26 weeks over a maximum of 52 consecutive weeks, whereas under the CDP, a 26 week employment outcome had to be achieved within 26 consecutive weeks (with an allowable break).

2.25 There were further concerns raised by other Government entities on:

- the timing of 13 and 26 week outcome payments not accounting for the seasonal and casual work available in remote labour markets; and

- the financial viability of CDP providers, as the 26 week outcome payments for the CDP were lower than those for the most highly disadvantaged jobseekers under the mainstream Employment Services 2015 model with no additional fees for providers, including ‘… to pay for interventions that address non-vocational and vocational barriers or to help jobseekers into work’.36

2.26 To reduce red-tape for providers, the CDP payment model was streamlined into three main payment categories from approximately seven different payment categories available under the RJCP.

Recommendation no.1

2.27 The ANAO recommends the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet review the Community Development Programme provider payment structure, particularly the incentives it creates and its alignment with the underlying policy objectives of the program changes.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s response: Agreed.

2.28 I agree with this recommendation. The CDP provider payment model, in tandem with provider performance management, has been effective in significantly improving employment outcomes for job seekers and encouraging job seeker attendance in work-like, skills building activities. However, having been in operation for over two years, there is now scope to consider whether the incentives still appropriately encourage providers to best support job seekers. The Department will consider, as part of the Government’s consultation on a new model for remote Australia, whether the current provider payment model is best supporting the programme to deliver on its dual objectives of employment outcomes and greater community participation.

Did the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet have a suitable strategy in place to underpin the transition of the Remote Jobs and Communities Program to the Community Development Programme?

PM&C developed a suitable phased transition and implementation plan, and communication strategy, to support the transition to the CDP. Due to the short implementation timeframes, many of the risks identified by PM&C materialised. In particular, the timeframes reduced the opportunity for providers to understand the substantial changes prior to implementation. While providers were authorised to access their Participation Accounts to facilitate the transition to the CDP, PM&C did not have arrangements in place to appropriately ensure commitments from the Participation Accounts met the program requirements. Four months following the introduction of the CDP, only 37 per cent of regions were on track to meet performance targets.

Transition arrangements

2.29 The transition from the RJCP to the CDP was considered a significant task, with six months between the announcement of the changes and the commencement of the new funding agreement on 1 July 2015, including a new payment model. In December 2014, the Government agreed to a four-stage process to transition from the RJCP to the CDP to be implemented over 18 months, as shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Transition from the Remote Jobs and Communities Program to the Community Development Programme

|

Phase |

Date |

Description |

|

One |

November 2014 to December 2014 |

|

|

Two |

January 2015 to June 2015 |

|

|

Three |

July 2015 to December 2015 |

|

|

Four |

January 2016 to July 2016 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C documentation.

2.30 The implementation risk management plan identified ten key risks to the transition process, six of which were rated as ‘high’.

Governance Arrangements

2.31 PM&C proposed that the transition process would be supported by an internal Implementation Taskforce; an interdepartmental RJCP Reform Sponsors Group; and subsequently a Reform Implementation Programme Board. A range of cross-agency working groups, supported by Project Boards, were also proposed.

2.32 The Reform Implementation Programme Board held its first meeting in late May 2015, some five months after the Minister’s announcement and only one month before the commencement of major program changes (such as continuous Work for the Dole in selected regions).

2.33 PM&C implemented the transition according to the overall implementation timeframe agreed by Government. The short timeframe between the announcement of the changes and the commencement of the new Funding Agreement on 1 July 2015 (including the new payment model) contained a number of inherent risks. PM&C established risk mitigation strategies to address these; however, several key risks, specifically those related to transitioning providers from the RJCP to the CDP, eventuated. Subsequently, a number of providers did not have the capacity to meet the requirements of the new Funding Agreements, impacting on the transition to the CDP and the extent to which providers were able to meet their CDP performance targets.

Provider transition

The development and expansion of structured activities

2.34 From December 2014, as agreed by Government, PM&C reviewed RJCP activities and jobseeker characteristics, and mapped Work for the Dole needs and potential activities for each region, informed by existing activities and provider Community Action Plans.

2.35 To facilitate the transition to the CDP, PM&C was to assist providers in each region phased for transition, to develop and establish Work for the Dole activities, and to monitor the Structured Activities being developed and offered to jobseekers. Providers in these regions were allocated placement targets for each month from April to July 2015, with the aim of 100 per cent of eligible jobseekers in these regions placed in Structured Activities (Work for the Dole activities) by 1 July 2015.

2.36 As at 1 July 2015, 45 per cent of Work for the Dole eligible jobseekers had been placed in Work for the Dole activities.37

Use of the Participation Account and other funding to support the transition

2.37 In the lead up to the implementation of the new CDP arrangements, from late March 2015 PM&C encouraged providers to make use of the (RJCP) Participation Account, to support the development of structured activities and increase participation rates.38

2.38 There was only a gradual increase in the rate of funding commitments from the Participation Account for most of the six months leading up to 1 July 2015. As at 13 May 2015, a large proportion (55 per cent) of projects were still in development or awaiting approval39—some dating back to September 2014.

2.39 After the Participation Account closed, PM&C advised the Minister that between 22 and 23 June 2015, providers had entered into the Account’s IT System more than $13 million in funding commitments. In particular, PM&C noted that at this time there had been a significant increase in withdrawals under $20 000 (which did not require prior PM&C approval). PM&C subsequently reduced the available notional balance in the Participation Account to ‘ensure appropriate expenditure and avoid overspending’ of the account.40

2.40 The total Participation Account funds paid to providers in 2014–15 was $152.6 million. As outlined in Table 2.4, in June 2015 alone, there were 415 advance payment expenditure transactions from the Participation Account across 38 CDP regions worth more than 20 per cent of the total funds expended in 2014–15 (>$30 million).

Table 2.4: Participation Account commitments of advance payment transactions in June 2015

|

|

Value of transactions ($) |

Number of transactions |

|

Transactions >$20 000a |

28 840 041 |

285 |

|

Transactions ≤$20 000b |

1 946 204 |

130 |

|

Total |

30 786 245 |

415 |

Note a: Transactions >$20 000 required prior approval from PM&C.

Note b: Transactions ≤$20 000 did not require prior approval from PM&C.

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C data.

2.41 PM&C’s review of expenditure from the Participation Accounts indicated that 30 per cent of commitments/claims in 2014–15 did not meet evidentiary requirements and were not payable.41

2.42 As part of its annual audit of financial statements, the ANAO identified weaknesses in PM&C’s management, reporting and pre-approval processes for Participation Account expenditure, resulting in the program area having to undertake a significant project to re-baseline and reconcile total expenditure of the Participation Account over the life of the former RJCP.42

2.43 Based on a direct selection process, on 11 May 2015 the Minister approved the awarding of a $19.5 million grant under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy to Indigenous Business Australia (IBA), to be managed through the Indigenous Economic Development Trust. The funding was sourced from the Participation Account and aimed to assist providers prepare for the implementation of continuous Work for the Dole under the CDP. The provision of funds through the grant was to address the risk that providers would have limited time to cost and purchase the services and equipment required from 1 July 2015 or would make ‘hasty and poor quality decisions’. Additionally, as the assets would be owned by Government, the risk of providers holding onto assets when contracts were cancelled (as occurred with CDEP providers with the onset of the RJCP) would be avoided.

2.44 In advising Government, PM&C expected the majority of this grant to IBA would be expended before 1 July 2015 given RJCP providers ‘will be required to deliver structured activities by then’. However, there was very limited time available for providers to identify services and equipment they would need to implement Work for the Dole, with IBA signing the agreement on 3 June 2015.43

Exiting and new providers

2.45 In the transition to the CDP, three providers across four regions (out of 41 providers across 60 regions) exited the program. Two of these providers requested that their funding agreements be terminated. The third provider’s funding agreement was not extended by PM&C due to serious performance and financial issues—including investigations for fraud. However, this same provider was then sub-contracted by the incoming provider to deliver activities within select communities in the region.44

2.46 PM&C replaced exiting providers through a register of interest process. Organisations were selected based on factors including: past performance in other regions; capacity for timely commencement of service delivery; and ability to establish meaningful community connections.

2.47 PM&C identified and monitored a number of significant risks associated with three of the four incoming providers. These included: prior poor performance; financial viability concerns; capacity to scale-up to provide region-wide services; investigations into board members for allegations of inappropriate accounting; and inability to recruit appropriate staff. To mitigate these risks PM&C offered shorter funding agreements to two of the incoming providers and advised government they would provide intensive business capability support and performance monitoring (for further discussion on risk, see paragraphs 3.18 to 3.24).

2.48 As the existing providers had access to the Participation Account, PM&C also provided start-up funding, totalling $1.8 million, to three of the four incoming providers.

Funding agreement Deed of Variations

2.49 The transition to the CDP was reflected in a variation of the existing RJCP funding agreements between PM&C and each provider. The draft agreements were made available to providers on 30 April 2014, with formal offers made to providers from 28 May 2015. Providers were expected to return the signed agreements to PM&C by 12 June 2015.45 PM&C executed the agreements between 16 and 29 June 2015.

2.50 The funding agreements incorporated the Programme Management Framework (PMF) for the CDP which established PM&C’s approach to the management of compliance, performance and assurance under the CDP. The PMF was discussed with providers in early June 2015 and came into effect from 1 July 2015.

2.51 Providers subsequently raised concerns that they did ‘… not believe they [had] enough information about the change to implement the changes by 1 July 2015’. Associated risks were also raised in PM&C’s advice to the Minister in June 2015.46

Implementation of the new Funding Agreement

2.52 PM&C contracted PricewaterhouseCoopers Indigenous Consulting (PIC) to work with providers ahead of the implementation of the CDP to help them understand the new funding agreement; to consider their operations and financial viability; and the financial implications of the changes, using PM&C’s Financial Modelling Tool.47

2.53 This provider support project was undertaken between 12 May and 30 June 2015, with PIC engaging with 32 of the (then) 41 providers. PIC noted that timing of their contract was difficult as it coincided with providers anxiously considering and signing the new funding agreements, communicating the changes to community and participants and trying to increase their delivery. PIC further noted that ‘… the project was too short to meaningfully evaluate the impact of using the financial modelling tool with providers’ and indicated that ‘… providers were struggling with being able to provide even basic financial information’.48 In September 2015, following advice from PM&C, the Minister approved the provision of funding for PIC to deliver additional provider capability support given the findings from PIC’s pre-implementation work.

2.54 During the start-up period, for the first six months following implementation of the CDP, providers received a minimum Work for the Dole monthly payment for 75 per cent of their Work for the Dole jobseeker caseload. In November 2015, four months after the CDP had commenced, only 22 regions (37 per cent) were assessed by PM&C to be on track to be able to maintain their funding level of 75 per cent monthly Work for the Dole payments from 1 January 2016 when outcomes-based payments began. PM&C advised the Minister that regions with jobseeker activity attendance below 37.5 per cent, particularly the bottom 10 performing providers/regions, were the focus of enhanced compliance action, with PM&C preparing Breach Notices for providers in three of the regions.49

Communication on the transition

2.55 The agreed implementation plan for the CDP included a communication and stakeholder engagement strategy. Dates for the release of key communication material were also included in PM&C’s implementation timeline and a stakeholder engagement calendar.

Communication with providers

2.56 To support providers during the transition to the CDP, PM&C made guidance material available through a number of channels.50 The more detailed information on the transition was available from March 2015.51 In submissions to this audit, a number of stakeholders noted there was inadequate time allowed for the provision of key guidance material and the implementation of the CDP. This impacted on providers’ understanding of the new requirements, particularly among smaller or less experienced providers.

Communication with jobseekers, communities and other stakeholders

2.57 As part of the agreed implementation plan, PM&C also proposed conducting a number of community consultations, and visiting a number of communities in conjunction with providers to discuss the changes. PM&C also developed flipcharts for jobseekers on the changes and ran a number of advertisements on community radio in English and Indigenous languages in May 2015.

2.58 The Minister visited a number of communities, providers and met with key stakeholders, including the Indigenous Advisory Council, in the lead up to the changes. Bilateral discussions were also held with relevant state and territory governments between March and April 2015 on opportunities to improve Government services to remote communities and create useful activities for jobseekers.

3. Administration of the Community Development Programme

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness and efficiency of the administration of the CDP; including payments, risk management and compliance arrangements.

Conclusion

PM&C has established appropriate governance, key program frameworks and guidance material to assist in the administration and delivery of the CDP. PM&C has also strengthened its approach to compliance and fraud prevention in light of identified program risks.

Areas for improvement

There would be scope for PM&C to provide greater guidance and transparency around ancillary payments to providers.

Has an appropriate governance framework been established with well-defined administrative policies, procedures and guidance in place?

PM&C has established appropriate governance frameworks and guidance material to assist the administration and delivery of the CDP. There are appropriate administrative arrangements in place between the relevant Australian Government entities responsible for delivering the CDP.

Community Development Programme frameworks and guidance

3.1 The administration and delivery of the Community Development Programme (CDP) was governed by a number of key program frameworks and guidance material, as outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Community Development Programme frameworks and guidance

|

Framework or guidance material |

Function |

|

Funding Agreement including Remote Activity Conditionsa |

Outlined the agreed terms and conditions of the funding assistance to providers, including: roles and responsibilities; program activities; and performance information; and information specific to the delivery of remote services. |

|

Programme Management Framework |

Outlined the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet’s (PM&C’s) approach to the management of compliance, performance and assurance under the Funding Agreement and all relevant guidelines, at both the program and provider level. |

|

CDP Guidelines Handbook |

Outlined program details to support the Funding Agreement and Remote Activity Conditions, for example, information on: services; payments; marketing and promotion; compliance; and performance. |

|

Provider Performance Review guides |

Outlined details on the Provider Performance Review process; the collection of performance information and determination of performance ratings against the key performance indicators. |

Note a: Two Remote Activity Conditions (RACs) existed under the Funding Agreement: RAC1 outlined the categories of remote services and associated payments; and RAC2 outlined the Remote Youth Leadership and Development Corps, phased out from 1 July 2015.

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C documentation.

3.2 This guidance addressed important aspects of the delivery and administration of the CDP, and provided information relevant for PM&C staff and CDP providers. PM&C is currently updating the CDP Guidelines Handbook.

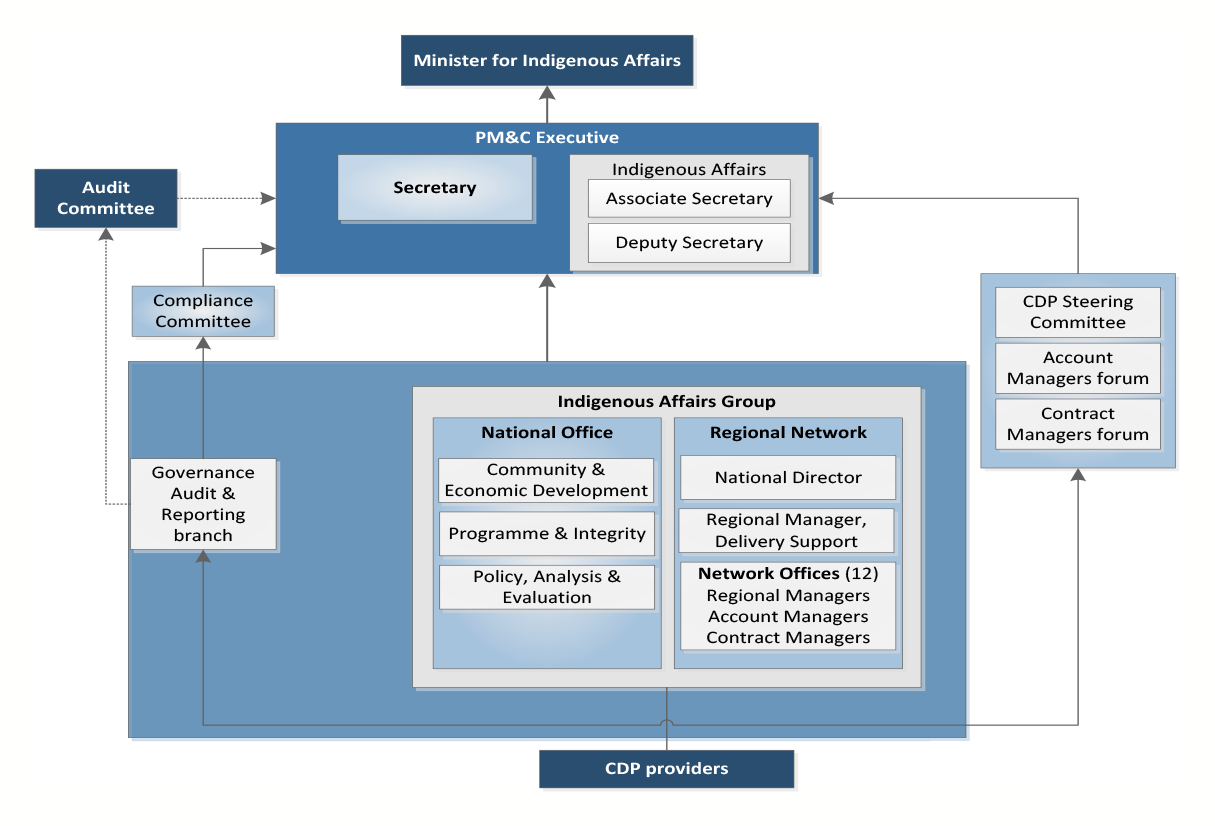

Governance arrangements

3.3 The CDP was managed within PM&C’s Indigenous Affairs Group (IAG). While CDP policy and other high-level program management functions were managed within the IAG national office, responsibility for day-to-day operations, management of providers, and identification of emerging issues affecting the CDP, was dispersed across the IAG regional network.52 The overall structure of governance for the CDP, as at May 2017, is outlined in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s internal governance structure for the Community Development Programme

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C documentation.

3.4 PM&C’s governing committee structure for the CDP changed over the two years following the implementation of the CDP. From July 2015 to July 2016, early implementation oversight was primarily the responsibility of the CDP Implementation Steering Group53, Remote Jobs and Communities Program (RJCP) Implementation Taskforce54, and to a lesser extent, the Programme Board.

3.5 From July 2016, it was intended that the CDP Implementation Steering Group would take on a more strategic role. In addition, two supporting fora were established—the CDP Account Managers forum and the CDP Contract Managers55 forum.56 While these governance fora offered a useful vehicle for raising issues and progressing strategies for managing individual providers, strategic direction and decision making was not a focus. The CDP Implementation Steering Group had only met twice since amending its terms of reference in July 2016 and the only substantive outcomes were the endorsement of PM&C’s Provider Performance Review (PPR) 2 outcomes in September 2016 and discussion of new budget announcements affecting the CDP in May 2017.

3.6 In addition, PM&C’s governance framework did not provide sufficient links between the CDP programme area and PM&C’s broader governance area, particularly in relation to management of fraud and serious non-compliance matters.

Cross-entity governance

3.7 Delivery of the CDP was supported by a Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) between each of PM&C, the Department of Employment (Employment) and the Department of Human Services (Human Services), as well as a cross-entity MoU management committee.

Is the Community Development Programme administered efficiently?

It is too early to assess whether the CDP is administered efficiently. The CDP is administered by entities at a higher unit cost than the RJCP and the broader jobactive employment services program.

3.8 As noted in Chapter 2, a key objective for the CDP was to broaden the availability and quality of structured activities for jobseekers. To support this objective, the Government agreed to an additional $94.9 million in funding, in addition to funding previously allocated under the RJCP, to ensure providers were sufficiently resourced to deliver Work for the Dole activities in remote communities that were work-like.

3.9 The estimated unit cost (per jobseeker) of delivering employment services in CDP regions was around double the estimated cost for delivery under the RJCP, as shown in Table 3.2

Table 3.2: Comparison the Remote Jobs and Communities Program and the Community Development Programme estimated cost per jobseeker

|

Program |

Total funding allocation ($million) |

Estimated total jobseeker caseload |

Estimated cost per jobseeker ($) |

|

Remote Jobs and Communities Program |

745.6a |

147 031b |

5 071 |

|

Community Development Programme |

1603.4c |

152 799d |

10 494 |

Note a: As per the funding allocated, from 2012–13 to 2015–16, to the RJCP in the 2012–13 Budget Paper No.2.

Note b: ANAO estimated jobseeker caseload for the RJCP from 2012–13 to 2015–16.

Note c: As per the final agreed costings for the CDP with the Department of Finance (2014–15 to 2017–18).

Note d: ANAO estimated jobseeker caseload for the CDP from 2014–15 to 2017–18.

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C data.

3.10 The ANAO calculated the estimated cost per jobseeker in the CDP (estimated 40 000 jobseeker caseload) in 2016–17 was around five times the estimated cost per jobseeker in jobactive (estimated 750 000 jobseeker caseload). These outcomes may partly reflect dis-economies of scale in sparsely populated areas as well as the inherent challenges associated with delivering services in remote locations.

3.11 The CDP formed part of the broader Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) with CDP expenditure estimated to be around 29 per cent ($1.4 billion in administered funds) of the IAS funding allocation ($4.9 billion)57 over four years to 2017–18.58 CDP expenditure primarily funded Work for the Dole, employment outcome, ancillary and the Employer Incentive Fund payments to providers.

3.12 Provider payments varied based on the accuracy of their reporting, jobseeker attendance at Work for the Dole activities, employment outcomes and overall caseload. ANAO analysis showed that in 2016–17, provider payments ranged from $2 950 to $31 419 per jobseeker (see Appendix 3 for detail on the payments made to providers). Providers reported that the ratio of jobseekers to staff employed to deliver the CDP (including operational/compliance staff) varied from eight to 117 jobseekers, with an average of 28 jobseekers for each provider staff member.

3.13 For 2015–16, the ANAO analysis showed that PM&C had a budget underspend for the CDP of just over $50 million, primarily due to fluctuations in the total number of jobseekers in the CDP and lower jobseeker attendance in Work for the Dole activities. Given this, there would be merit in PM&C reviewing the factors underpinning the wide variation in provider payments, and the resulting underspend, including on whether provider resources have been put to optimal use and whether there is scope to improve on the efficiency with which providers deliver the CDP.

3.14 At the time of the audit, the CDP had been implemented for around 24 months and the ANAO considered this period of time to be too short to assess broader efficiency, taking into account policy outcomes.

Departmental

3.15 PM&C advised the ANAO that PM&C’s average staffing level (ASL) to administer the CDP was 106—comprising of 56 ASL in the regional network and 50 ASL in the national office. As noted at paragraph 1.15, the Department of Employment was allocated $3.2 million in departmental funding for delivery of IT services. The Department of Human Services delivered its CDP functions from existing resources.

Are fit-for-purpose risk management plans in place?

PM&C has developed a fit-for-purpose risk management strategy to support the administration of the CDP. In late 2016, PM&C integrated its approach to risk management across the broader Indigenous Affairs Group grants program, which included the CDP. PM&C also established provider risk plans and assessments. However, some key program risks were either not identified in the program level risk plan, or were not fully addressed by mitigation strategies.

3.16 PM&C’s entity-wide approach for managing risk and compliance was supplemented by specific measures to support the operation of the CDP, namely:

- a program level risk management plan (formally owned by the CDP Steering Group);

- provider risk plans; and

- program fraud risk assessment (and corresponding specification of controls/treatments).

3.17 These mechanisms were supported by a centralised monitoring and compliance area which oversaw CDP provider compliance and performance.

Program level risk management plans

3.18 The CDP program level risk plan59 was approved by the Programme Board in December 2015.60 The risk plan included ten significant risks, including: fraud and other misappropriation of funds; gaps in support for providers; budget and ICT infrastructure constraints; data quality; and occupational health and safety risks to jobseekers.

3.19 Some of the specified controls and treatments did not fully address the identified risks. For example:

- while individual risk profiles were prepared for each CDP provider, this did not always translate to increased monitoring or support for that provider;

- the risk plan did not adequately account for functions being carried out by other entities—for example, the challenges for Human Services in re-engaging jobseekers located in remote areas; and

- while PM&C prepared risk profiles for individual providers to inform monitoring and support requirements, the allocation of staff to oversee these risks was not aligned with the risk profiles but determined by Regional Managers in response to local community priorities; as well as the competing needs of other programs.

Provider risk

3.20 Provider Risk Plans were a core element of PM&C’s risk framework. PM&C’s Account Managers were responsible for preparing risk plans for each provider, and each region, which were typically updated every six months following the review of provider performance. The Provider Risk Plans were intended to reflect local monitoring results as well as performance and compliance information held by PM&C.

3.21 The 2016 Provider Risk Plans assessed providers against five risk categories. Table 3.3 outlines these risk categories and the overall results for 2016. While the typical assessed rating for providers across all categories was ‘moderate’, a significant proportion of providers were rated as presenting a ‘high’ or ‘very high’ risk against each category.

Table 3.3: Provider risk assessment and results, 2016a

|

Risk category |

Risk description |

Most common rating for 2016b |

Proportion of providers assessed as ‘high’ or ‘very high’ risk |

|

Fraud |

The provider is vulnerable to intentional practices designed to appropriate funds or performance that is not warranted. |

Moderate |

20% |

|

Financial viability |

The provider is financially vulnerable and not capable of withstanding downturns in income, or other financial factors. |

Moderate |

37% |

|

Service delivery and performance |

The provider does not deliver activities and services effectively, including coverage, diversity, and meeting participants, community or employer demand. |

Moderate |

42% |

|

Governance and compliance |

The provider has an inadequate governance framework, strategic direction or operational proficiency. The provider is at risk of not complying with regulations and provisions of the CDP Funding Agreement including claims for payment and other financial and contractual compliance. |

Moderate |

10% |

|

Relationships |

Effective relationships are not developed and maintained with internal and external stakeholders which impact on outcomes and delivery of services. |

Moderate |

20% |

Note a: As at May 2017, the results of the 2016 provider risk assessments were the most recent results available.

Note b: The available risk ratings were: low, minor, moderate, high and very high.

Source: PM&C guidance and ANAO analysis.

3.22 Assessments of provider financial viability, based on providers’ annual financial statements, were undertaken by Employment on behalf of PM&C. All incoming providers underwent a financial viability assessment, with ongoing annual assessments for existing providers.

3.23 In late 2016, PM&C began work to ensure CDP provider risk assessments were fed through the broader IAG Grant Applicant Risk Profile (GARP) assessments conducted.61 GARPs considered provider delivery against other PM&C programs and funding agreements. This integration was particularly important given many CDP providers were also delivering other PM&C service delivery agreements by grant (for example, the Remote Schools and Attendance Strategy).

Program fraud risk

3.24 PM&C’s Fraud Risk Plan for the CDP (in addition to the broader departmental Fraud Control Plan and Fraud Risk Register) specifically targeted the risk of providers claiming funding for services not delivered. Although the plan identified specific controls and treatment actions, PM&C’s IAG carried out its non-compliance functions independently from PM&C’s serious non-compliance and fraud teams. Integration between PM&C’s CDP operations area and its fraud and serious non-compliance area is discussed further at 3.42.

Has a suitable compliance framework been implemented?

PM&C has developed a suitable compliance framework for both jobseekers and providers under the CDP. Given the inherent risks associated with issuing payments based on provider-reported data, PM&C has now strengthened its approach to identifying and pursuing suspected instances of non-compliance by providers.

Jobseeker compliance framework

3.25 The Social Security Act 199162 requires jobseekers receiving activity-tested income support payments to satisfy mutual obligation requirements (MORs). The level and exact nature of a jobseeker’s MORs vary according to their: income support type; age; work capacity; level of education completed; and carer responsibilities. Under the CDP, providers set activities through which jobseekers met their MORs.63 64

3.26 The Job Seeker Compliance Framework (JSCF), administered by the Department of Employment65, was intended to assist providers to quickly re-engage non-compliant jobseekers. Under the JSCF, providers were required to take compliance action and lodge compliance reports where a jobseeker failed to meet the MORs under the CDP. 66 The type of action taken depended on the nature of the jobseeker’s non-compliance.67

3.27 While providers were responsible for initiating compliance action, Human Services was responsible for administering the Social Security Act 1991, including any prescribed penalties.68 Human Services’ determination was in some cases informed by a Comprehensive Compliance Assessment which sought to identify any barriers to compliance for the jobseeker.69

3.28 In 2015–16, around 146 700 financial penalties were applied to CDP jobseekers (with the majority of these penalties related to non-attendance at activities) compared to around 35 500 in the RJCP in 2014–15. This reflects that under the CDP, unlike the RJCP, providers were required to consistently enter jobseeker attendance data and, where required, initiate action under the JSCF. Provider payments were dependent on the accurate reporting of jobseeker attendance and re-engagement.

3.29 Moreover, based on a snapshot of Participation Reports in January 2017 for both jobactive and the CDP, 54 per cent of all non-compliance reports across the two programs that triggered Human Services’ investigation and decision making process were CDP generated, despite the CDP comprising around 5 per cent of the jobactive caseload.

3.30 Providers centralised compliance teams in regional centres, engaged external contractors or used third-party organisations to assist with the compliance process due to reported complexity of the JSCF and the difficulty in employing local staff with relevant skills and experience.

CDP jobseeker and provider contact with Human Services

3.31 Jobseekers who received payment suspensions due to non-compliance were required to contact Human Services to discuss the reasons and arrange reconnection. Human Services indicated that jobseekers (and providers) calling from remote locations were given priority through the use of the Participation Solution Team (PST) phone number (1300 306 325). However, Human Services general enquiries phone number (132 850), referenced in the JSCF, was not prioritised by Human Services according to remote post codes.