Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Award of Grants under the Clean Technology Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and equity of the award of funding under the Clean Technology Program in the context of the program objectives and the Commonwealth’s grants administration framework.

Summary

Introduction

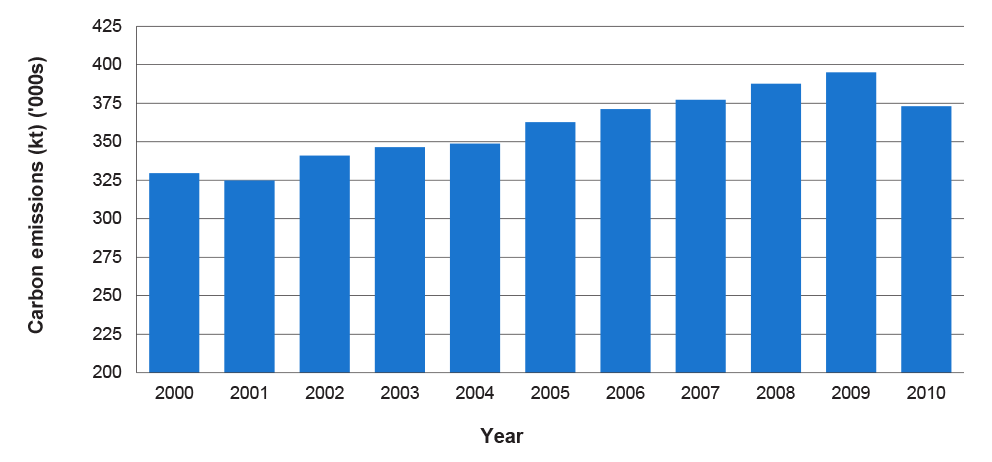

1. Over recent years, successive Australian governments have adopted various policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions. On 10 July 2011, the then Government released its Securing a Clean Energy Future Plan (the Clean Energy Future Plan). The Clean Energy Future Plan included placing a price on carbon emissions1 and setting a new long-term target to reduce carbon pollution by 80 per cent by 2050 compared with year 2000 levels. This was in addition to an existing commitment to reduce carbon pollution by five per cent from 2000 levels by 2020.

2. As part of the Clean Energy Future Plan, the then Government committed to providing transitional assistance for manufacturing businesses to adjust to the carbon price. This assistance was to be delivered through the $1.2 billion Clean Technology Program, which comprised the:

- Clean Technology Investment Program (CTIP)—which was allocated $800 million between 2011–12 and 2017–18 to assist manufacturers to invest in energy-efficient capital equipment and low-emissions technologies, processes and products;

- Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Program (CTFFIP)—which was allocated $200 million between 2011–12 and 2016–17 to help manufacturers in the food and foundries industries to invest in energy-efficient capital equipment and low-emission technologies, processes and products; and

- Clean Technology Innovation Program—which was allocated $200 million between 2012–13 and 2016–17 to support research and development, proof-of-concept and early stage commercialisation activities that lead to the development of new clean technologies and associated services, including low emission and energy efficient solutions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

3. The then Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (DIISRTE, now the Department of Industry (the department)) was responsible for the design and implementation of the Clean Technology Program. Specifically, the Manufacturing Policy Branch of the department was responsible for program design, while the AusIndustry Division was responsible for program implementation.

4. The CTIP and CTFFIP (the programs), which are the focus of this audit2, had similar objectives3 and reflected a policy articulated in the Clean Energy Future Plan that:

for many Australian manufacturers, improvements in energy efficiency will be the most effective way that carbon cost impacts can be managed to ensure long-term competitiveness. While a carbon price will provide incentives for these manufacturers to reduce energy consumption, the Government will also help manufacturing businesses identify and implement technologies that will improve energy efficiency and reduce their exposure to changing electricity prices.4

5. The objective of the programs was supported by the four merit criteria listed in the program guidelines, which are set out in Table S.1. As illustrated by this table, the extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity5 (merit criterion one) had a higher weighting compared to the other criteria. As a result, the criteria weightings reflected that the main objective of the programs was to reduce the carbon emissions intensity of manufacturers. Further, in this respect, and consistent with the Clean Energy Future Plan, the extent to which a project maintained and improved the competitiveness of the applicant’s business was of significantly less importance.

Table S.1: Merit criteria for the programs

|

|

Merit criterion |

Score for applications seeking grant funds: |

|

|

up to $1.5 million (%) |

over $1.5 million (%) |

||

|

1 |

The extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity, including through improvements in energy efficiency arising, from the project. |

70 (70.0) |

70 (58.3) |

|

2 |

The capacity and capability of the applicant to undertake the project. |

15 (15.0) |

15 (12.5) |

|

3 |

The extent to which the project maintains and improves the competitiveness of the applicant’s business. |

15 (15.0) |

15 (12.5) |

|

4 |

The contribution of the proposed project to a competitive, low carbon, Australian manufacturing industry and the benefits to the broader Australian economy. |

N/A |

20 (16.7) |

|

Total score |

100 (100) |

120 (100) |

|

Source: CTIP and CTFFIP program guidelines.

6. A feature of the programs, when compared with many grant programs, was that they operated through a continuous application and assessment process, rather than discrete funding rounds. In this respect, the program guidelines set out that a staged assessment and approval process would be employed, including:

- an initial assessment of the eligibility and completeness of applications by the department;

- merit assessment of eligible applications by Innovation Australia (IA)6; and

- a funding recommendation from IA to the decision-maker.7

7. The programs opened to applications in February 2012 and closed in October 2013.8 A total of 1171 applications seeking $773.5 million were received by the department. The amount sought in these applications ranged from $25 000, which was the minimum amount of funding available under the programs, to $20.8 million.

8. Grants were awarded to manufacturers in a range of industry segments and for different types of emissions reduction measures. However, there were instances where the successful applicant chose not to: execute the funding agreement; or proceed with the project despite having an executed funding agreement in place. In this respect, a total of:

- 603 projects were awarded $314.9 million under the programs, with funding distributed equally between the programs; and

- funding agreements were signed in respect to 569 projects for $295.9 million in funding, with funding distributed equally between the programs. Of these agreements, 16 were later terminated. The remaining 553 projects had an executed funding agreement in place as at 2 October 2014 involving $265.2 million in funding. Of this amount, 54 per cent of funds related to the CTIP and 46 per cent of funds related to the CTFFIP.9

Audit objective, scope and criteria

9. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and equity of the award of funding under the Clean Technology Program in the context of the program objectives and the Commonwealth’s grants administration framework.

10. In June 2013, the Auditor-General received a request from Senator Simon Birmingham, Liberal Senator for South Australia, then Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for the Murray-Darling Basin and then Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for the Environment to undertake an audit of the Clean Technology Investment Program. The Senator raised a number of concerns about the process for awarding grants under the programs and, in relation to the Clean Technology Investment Program, the distribution of funding in electoral terms. A potential audit of the Clean Technology Program was included in ANAO’s Audit Work Plan for 2013–14 as the resources to undertake an audit were not available at the time of the Senator’s request. Audit resources became available later in 2013, with this audit commencing in November 2013. This audit also examined the specific matters raised by the Senator.

11. The scope of the audit included the design of the programs, as well as the assessment and decision-making processes in respect to the 1171 applications that were received. The audit scope was focused on the application and assessment processes up to the point at which funding was awarded and a funding agreement signed, and also included analyses of the distribution of funding (including in electorate terms) and the announcement and reporting of grant funding. The scope did not include the administration of the Clean Technology Innovation Program (see paragraph 2).10

12. The audit criteria reflected relevant policy and legislative requirements for the expenditure of public money and the grants administration framework, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (which have now been replaced by the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines). The criteria also drew upon ANAO’s Administration of Grants Better Practice Guide.

Overall conclusion

13. The Clean Technology Investment Program and the Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Program were well received by industry, with 1171 applications made seeking over $773 million in Australian Government funding.11 By the time the programs were closed, after some 18 months of operation, 603 projects had been awarded nearly $315 million in grant funding.12 This result was achieved due to a range of factors, particularly the strong demand for funding and the significant level of assistance provided to applicants by the department’s AusIndustry Division. In this latter respect:

- a high proportion of applications (84 per cent) proceeded through the eligibility checking stage to merit assessment;

- a similarly high proportion of applications (74 per cent) that proceeded to merit assessment were recommended and approved for funding; and

- expenditure proceeded more quickly than originally budgeted, such that $160 million in program funding was brought forward to 2014–15.

14. The significant amount of grant funding provided to industry over the relatively short period of time the programs were in operation was consistent with AusIndustry’s culture of assisting businesses to access programs it administers. However, the approach that was taken to assessing applications was not sufficiently focussed on maximising program objectives and treating applicants equitably. As a result, it was common for funding to be approved for projects that did not have high expectations as to the extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity they would deliver.13 Further, a number of the approaches employed to maximise the assistance to industry did not sit comfortably with the operation of a competitive grants program under the Australian Government’s grants administration framework. Specifically:

- some incomplete applications were permitted to proceed to the departmental merit assessment;

- some applications were ‘reframed’14 to improve their assessed merit in terms of published criteria.15 The published program material, and internal program documentation, did not clearly establish the circumstances in which reframing assistance would be provided to applicants by the department, and the extent of this assistance. Further, applicants were not required to re-submit reframed applications;

- the assessment and selection method employed was inconsistent with the approach approved by the then Government, which had referred to a competitive grants program. In particular, applications were not ranked in terms of the extent to which they had been assessed as meeting the published merit criteria; and

- the program guidelines stated that applications would be assessed by IA, but 41 per cent of applications were assessed by a committee of departmental officers operating under IA delegation. This helped to expedite the processing of grant applications16, but meant that specialist knowledge was not used to assess a large number of applications.

15. A key message from a number of ANAO audits of grant programs over the years, which has also been included in both the 2010 and 2013 versions of ANAO’s Grants Administration Better Practice Guide, is that selecting the best grant applications promotes optimal outcomes. In this respect, it was originally expected that projects that delivered a significant reduction in carbon emissions intensity would be funded under the programs. However, the assessment of applications against the primary merit criterion was not solely focused on the extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity. Instead, so as to ensure that large manufacturers would not be penalised for making small percentage improvements, the department’s scoring against the emissions intensity reduction criterion also incorporated an assessment of the amount of grant funding requested per tonne of carbon abated.17 As a result, while the design of the programs intended that only those projects which delivered a significant reduction in carbon emissions intensity would be funded, projects offering relatively low emissions intensity reductions were also successful.18

16. More broadly, the department did not set a performance target for the programs in terms of the amount of carbon savings, with the indicator it established19 relatively low in comparison to the then Government’s target to reduce carbon emissions by five per cent from year 2000 levels.20 The department has advised ANAO that it has estimated that the nearly 200 projects that have been completed will abate over 1730 kilotonnes of carbon, a figure slightly above what was expected when funding was recommended and approved. However, the use of grants to fund emissions reduction measures by businesses was a relatively expensive means of reducing carbon emissions in comparison to the carbon price, which the department cited as a reference point for assessing value for money.21 Departmental figures indicate a cost per tonne of more than $5422 for the savings expected across all contracted projects, of which the Australian Government is contributing $18 per tonne with industry to contribute the remainder. Grant funds per tonne of carbon abated ranged from $1.52 to $140.27 for individual projects.23

17. Against this background, the ANAO has made four recommendations that are designed to:

- improve aspects of grant program design and governance arrangements;

- promote equitable access to grant funding opportunities that operate through continuous application and assessment processes;

- improve the merit scoring approaches adopted for competitive, merits-based grant programs; and

- adopt a stronger outcomes orientation when advising decision-makers on which grant applications should be approved for funding.

18. An important message from this audit is that there would be benefit in the department reconsidering the balance that it strikes between AusIndustry assisting business to access funding opportunities, and better practice grants administration principles and practices. In particular, there are risks to be understood and managed when those responsible for assessing applications competing for funding are also able to suggest, or make, changes to an application so as to improve its chances of success.

Key findings by chapter

Program Design (Chapter 2)

19. The design of the programs was challenging for the department given the diversity of projects, and the broad range of technologies of varying complexity eligible to be funded. In this context, design of the programs was informed by extensive stakeholder consultation, with the department responsive to the feedback that it received.

20. To provide a sound overall foundation for implementing the programs, a range of program documentation was developed by the department. However:

- a probity plan was not developed; and

- the programs were not designed to guard against the approval of funding for projects that were largely complete at the time of application or had been committed to prior to receiving any Australian Government funding.

21. In addition, the department developed two sets of guidelines, Ministerially approved program guidelines and ‘customer guidelines’ (which were more comprehensive than the program guidelines). The use of separate, but related program guidelines and customer guidelines made it easier for the department to make changes over time to the assessment of applications. However, having a consolidated set of guidelines is generally regarded as better practice because it provides prospective applicants with a single reference point for key information, including the assessment and selection process, and reduces the risk of inconsistencies between documents. In this respect, a key element of the implementation of the programs involved the use of two indicators to assess applications against the first merit criterion. The existence of two indicators was not identified in the program guidelines, and the second indicator that was used in the assessment of applications24 was not identified until the fifth version of the customer guidelines, promulgated in December 2012.25

22. More broadly, the assessment and selection method identified in the program guidelines was inconsistent with the approach approved by the then Government, which referred to a competitive grants program. In this regard, the assessment and selection process that was implemented reflected elements of a merit-based, non-competitive program. In particular, the programs were not implemented in a way that applications competed for the available funding by being ranked in order of merit. Rather, projects were approved for funding so long as:

- the application had been assessed as eligible and as having some merit (rather than being rated highly against each merit criterion as was required by the program guidelines)26; and

- sufficient program funding remained available.

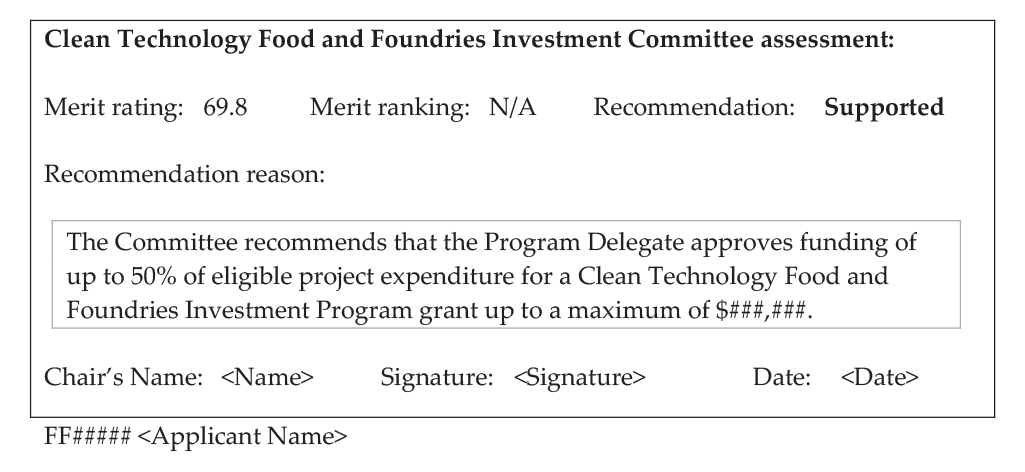

23. In addition, the department did not develop a sufficiently structured process for assessing applications against the merit criteria, with the assessment of applications involving a range of factors that the department and/or IA considered pertinent. In this respect, one IA committee chair advised ANAO that the committee took into account a range of objective and subjective matters that were not reflected in the records of the assessment process. Further, while the department provided committee members with an assessment template to facilitate the assessment of applications by IA, any completed templates were not retained by the department. In these circumstances, the basis for funding recommendations made by IA to the program delegate was not evident.27

24. As an outcomes orientation is one of the key principles for grants administration included in the CGGs, it is important for agencies to develop an evaluation strategy during the design phase of the granting activity and appropriate performance indicators. The department did not, however, develop an evaluation strategy prior to the closure of the programs. In addition, performance reporting has aggregated the number of projects with an expected reduction in carbon emissions intensity of at least five per cent. This approach:

- does not reflect actual outcomes achieved by the funded projects; and

- was not consistent with the desired outcome set out in the Clean Energy Future Plan.

Access to Funding (Chapter 3)

25. The program was well received by the manufacturing industry, with the department receiving 1171 applications for funding. In total, 159 applications were not processed due to the closure of the programs in October 2013. The remaining 1012 applications proceeded to the eligibility checking stage with relatively few applications (61 or six per cent) assessed by the department as not meeting the eligibility requirements. The department retained documentation to support the majority of eligibility assessments, and affected applicants were provided with advice as to the reasons their application had been assessed as ineligible.

26. The process that was established by the department for assessing applications against the eligibility and merit criteria was focussed on helping applicants access funding under the programs. In particular, the department:

- permitted some incomplete applications to proceed to departmental merit assessment; and

- proposed changes to applications that it considered were not likely to receive funding in their original state.

27. In this latter respect, rather than requiring affected applicants to resubmit a reframed application, it was common for departmental assessors to reframe the project activities, expenditure and/or underlying assumptions for some applications to improve the application’s assessed merit in terms of the published criteria. In these cases, the departmental assessors often made changes to the project or the information in the application28 by:

- adjusting the project, or claims made in the application, themselves and seeking agreement from the applicant to the changes; or

- advising the applicant to exclude components of their project that were not considered competitive.

28. The approach adopted for the programs went well beyond clarifying information included in applications and seeking to address any minor information missing from applications. More broadly, combining advisory and assessment roles is an approach not well suited to maintaining an objective assessment of competing applications. In this context, where government decides that an advisory role should be performed in addition to the assessment of applications, it is preferable that a clear separation be maintained between the roles so as to maintain the objectivity of the assessment stage. There are also challenges that arise in treating applicants equitably due to the risk that the level of assistance provided to applicants will vary.29

Reduction in Emissions (Chapter 4)

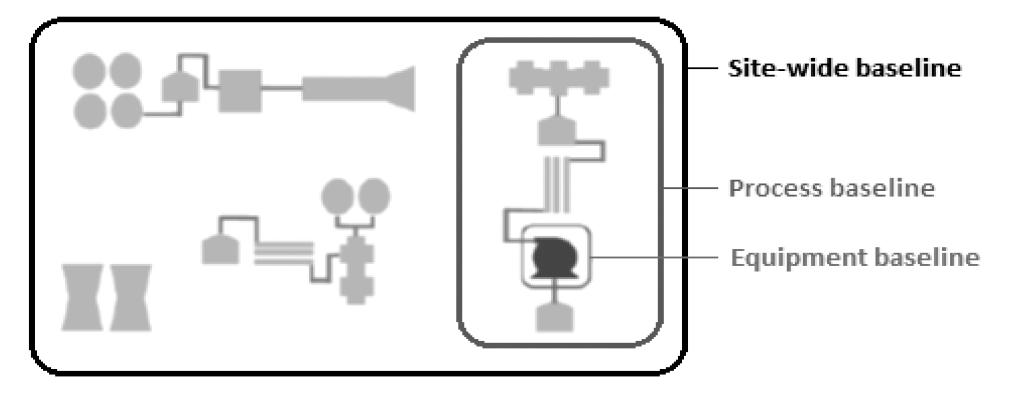

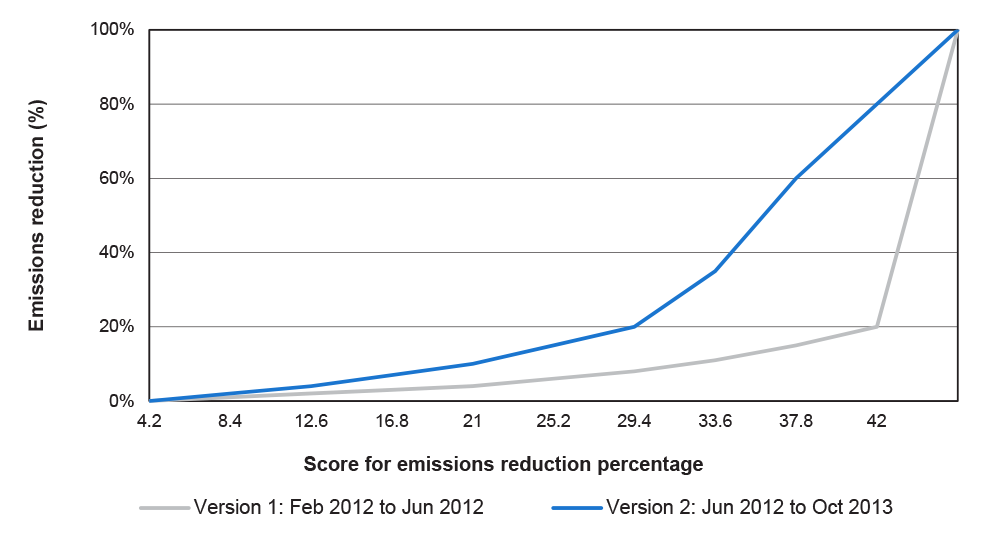

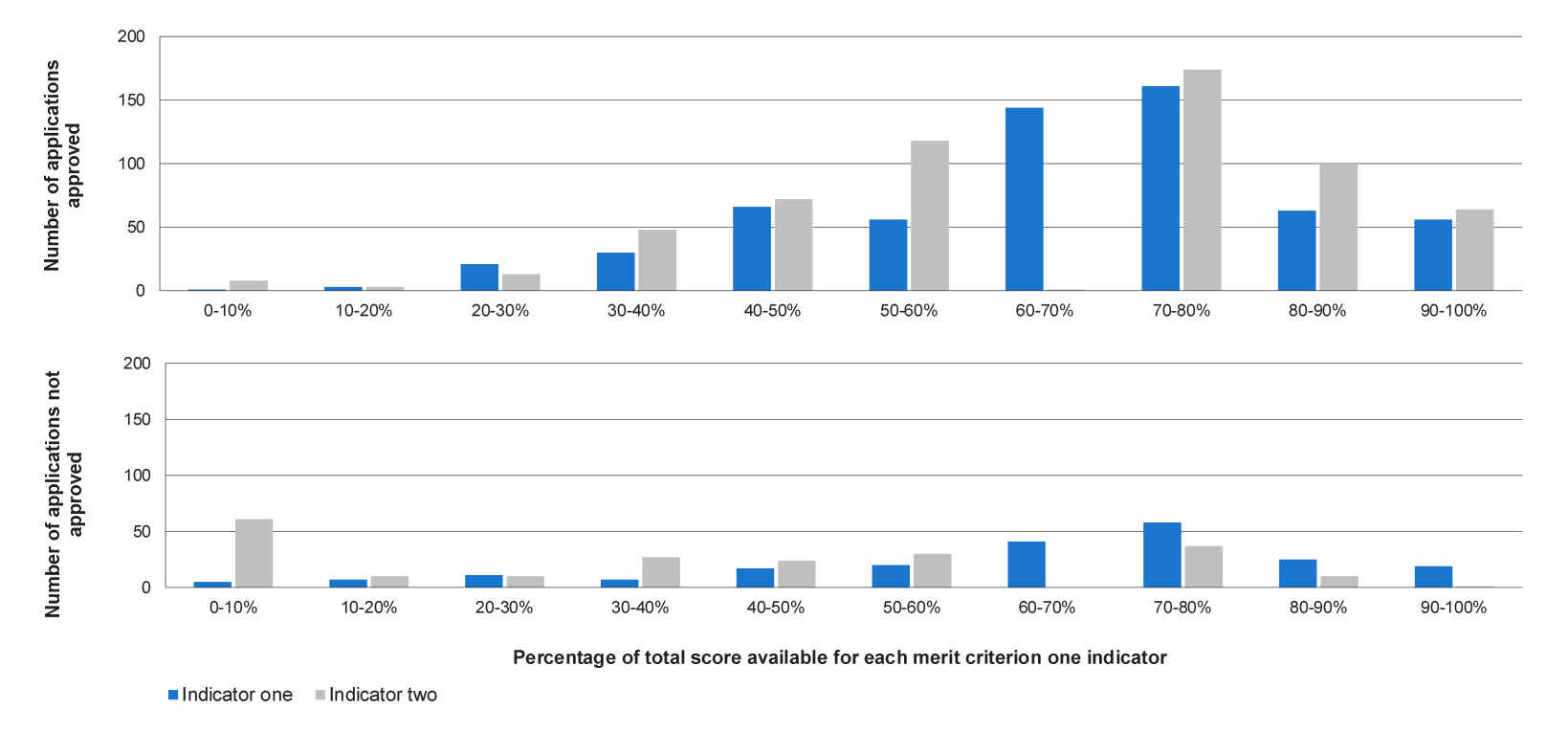

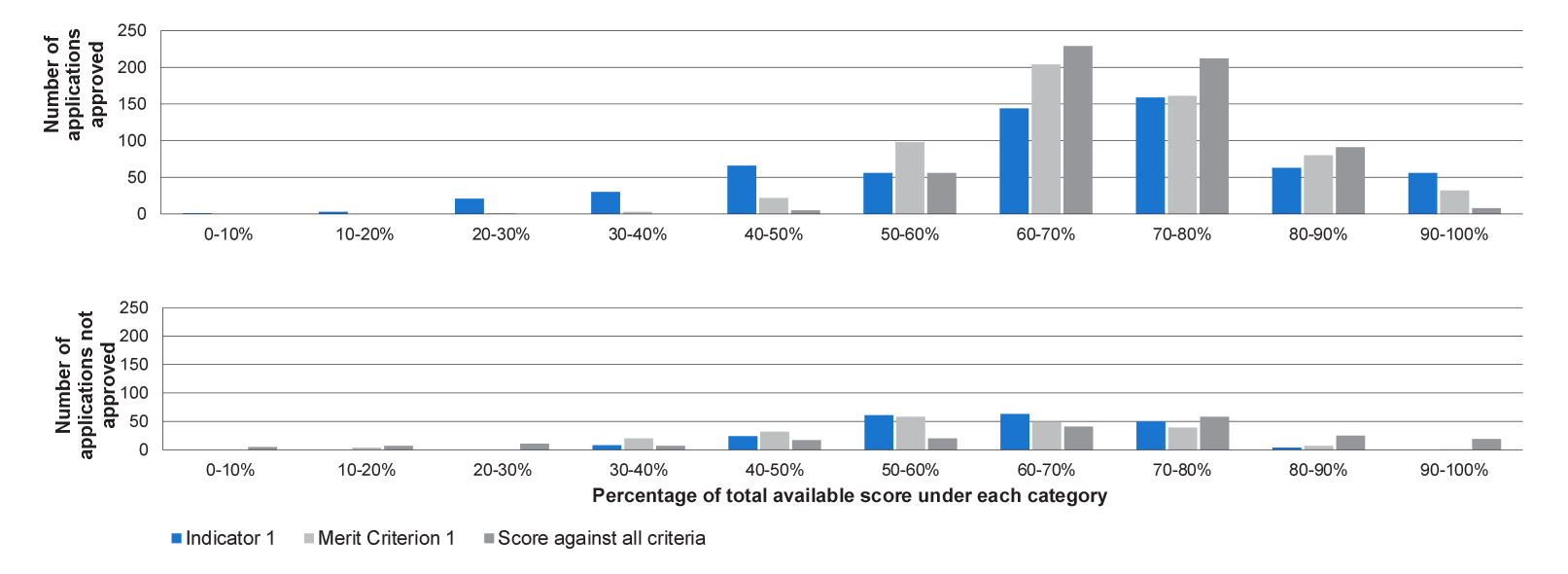

29. Consistent with the program objective, the extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity associated with projects was the most highly weighted of the merit criteria. There were two indicators used to assess eligible applications against this criterion (see Table S.2). A Carbon and Energy Savings Calculator was developed to calculate results for the two indicators for individual projects and a carbon scoring tool was developed to promote consistent scoring against both indicators for this criterion.

Table S.2: Merit criterion one indicators

|

Indicator |

Performance indicator used in scoring as detailed in the procedures manual |

Weighting |

Maximum score for indicators |

|

Indicator one |

Predicted reduction in carbon emissions intensity (%) following project implementation |

60% |

42 |

|

Indicator two |

Total carbon savings over the life of the conservation measure |

40% |

28 |

|

Total |

|

100% |

70 |

Source: CTIP and CTFFIP customer guidelines and program procedures manual.

30. The first indicator was consistent with the published criterion. However, the percentage reduction calculated was highly dependent on the project boundary30, with a smaller boundary resulting in a higher percentage reduction being calculated. This led to inconsistencies in the way that the reduction in carbon emissions intensity was measured and meant that applicants with projects that delivered the same amount of carbon savings could be scored differently depending on the project boundary selected.31 Further, one of the approaches adopted during the assessment of applications to improve the chances of an application being approved for funding was to adjust the project boundary being used for emissions intensity reduction calculation purposes (but without the project itself actually changing) so as to increase the assessment score to a level at which the project could be recommended for funding.

31. Departmental records outlined that the second indicator for the first merit criterion was intended to ensure that large manufacturers would not be penalised for making small percentage improvements, as these small improvements could still yield large carbon savings. However, the assessment approach for the second indicator involved the department calculating the grant funding requested per tonne of carbon abated whereas the customer guidelines had identified this indicator as relating to total carbon savings over the life of the conservation measure. The department advised ANAO that this was seen as a way to compare and consistently score total carbon savings over the life of the project. However:

- ANAO’s analysis indicates that such an approach was inconsistent with the first merit criterion, which related to the extent of any reduction in carbon emissions intensity with the second indicator used in the assessment, instead, relating to an application’s cost-effectiveness or ‘value for money’32; and

- by reducing the requested grant amount33, applicants or assessors could improve the score achieved against the indicator, without any change to the carbon savings expected to be achieved over the life of the conservation measure.34

32. The existence of the value for money indicator was not identified in the program guidelines and was not identified until the fifth version of the customer guidelines, which were promulgated in December 2012. The inclusion of this indicator had a significant effect in that, had the merit criterion score solely related to each application’s assessed performance in terms of the predicted percentage reduction in carbon emissions intensity, 57 successful applications may not have been awarded a total of $30.6 million in grant funding.

33. A more appropriate and transparent approach, consistent with a range of other Australian Government funded grant programs audited by ANAO, would have been for a separate project cost-effectiveness criterion to have been included in the published program guidelines.

Advice to the Program Delegate and Funding Decisions (Chapter 5)

34. The program delegate within the department was responsible for making all funding decisions under the programs. Of the 849 applications that were assessed against the merit criteria35, 35 were not considered by the program delegate due to the closure of the programs.

35. The grants administration framework has a particular focus on the establishment of transparent and accountable grant decision‐making processes. In this context, the program delegate accepted all recommendations that were received in terms of those applications that should be awarded funding, and those that should be rejected. However, there were a number of shortcomings in the advice provided to the delegate to inform funding decisions. Specifically:

- the records that supported the IA assessment did not demonstrate that each application was assessed against each of the merit criteria;

- the advice provided to the delegate did not demonstrate that the recommended applications rated highly against each of the merit criteria; and

- the advice to the delegate did not clearly identify the expected outcomes from funding each recommended project.36

Reporting and Funding Distribution (Chapter 6)

36. The department’s website reporting of grants made under the programs was largely consistent with the reporting requirements of the CGGs and associated guidance. Further, the application, assessment and decision-making processes for the programs guarded against the award of funding being politicised. ANAO analysis of the distribution of funding awarded under the programs did not identify any political bias. Of note in this respect was that, although the total value of grants to electorates held by the then Government was greater, the approval rate for grants to electorates held by then Opposition was slightly higher.

Summary of entity response

37. The proposed audit report was provided to the department and extracts were provided to the former chairs of the Clean Technology Investment Committee and the Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Committee. The department provided formal comments on the proposed report and these are summarised below, with the full response included at Appendix 1:

The Clean Technology Investment Programs were delivered as part of the former government’s Clean Energy Future Plan. The Programs were designed to deliver on two goals of carbon abatement and maintaining the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector by improving energy efficiency through replacement of capital stock. This required innovative program design particularly in regard to the technically complex requirements for estimating and assessing carbon abatement. These methodologies were developed in consultation with key stakeholders including the former Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency.

Demand for the Programs were high with 1171 applications received and 603 projects awarded grants. The Programs accommodated a wide variety of projects, ranging from a $50,000 solar panel installation in a small winery to a $70 million dual site consolidation for concrete manufacture. Carbon abatement varied significantly depending on the nature of the emissions reduction measures with supported projects estimated to deliver between 0.5 kilotonnes and 1000 kilotonnes of carbon savings.

The department notes the report acknowledges that the application, assessment and decision-making processes for the programs guarded against the award of funding being politicised and that there was no evidence of political bias in the distribution of funding.

The department acknowledges the contribution the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) makes to enhancing administration around granting programs through the observations in the report, particularly in relation to administrative transparency. This will assist the department to strengthen its existing grants management frameworks.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.82 |

To improve the design of, and governance arrangements for, future grant programs, ANAO recommends that the Department of Industry: (a) develops a single set of program guidelines that is approved in accordance with the grant program approval requirements; (b) includes, as an eligibility criterion, a requirement that excludes projects that are largely complete, or would otherwise proceed, without Australian Government funding, in circumstances where government intends not to fund such projects; (c) ensures that the basis for recommendations to the program delegate is appropriately documented, with documentation retained by the department; and (d) develops performance indicators that align with broader government policy outcomes. Department of Industry’s response: Agreed in-principle part (a). Agreed parts (b), (c) and (d). |

|

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.48 |

To promote equitable access to grant funding and objective assessment of competing grant applications, ANAO recommends that, where government decides that advisory assistance should be provided, the Department of Industry separate the provision of this assistance from the task of assessing applications. Department of Industry’s response: Agreed. |

|

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 4.42 |

In the administration of competitive, merit-based grants programs, ANAO recommends that the Department of Industry design, publicise and implement merit assessment scoring approaches that promote a clear alignment between the published program objective, the merit criteria, the weighting for those criteria and any scoring indicators. Department of Industry’s response: Agreed. |

|

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 5.28 |

To promote a stronger outcomes orientation in the administration of future grant programs, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Industry: (a) clearly identifies, in advice provided to decision-makers, the extent to which assessed projects are expected to deliver outcomes that are consistent with the overall program objective and related performance targets; and (b) include, as a requirement in respective funding agreements, the expected outcomes that informed decisions to award funding. Department of Industry’s response: Agreed part (a). Agreed in-principle part (b). |

|

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Clean Technology Program and sets out the audit objective, scope and criteria.

Background

1.1 Over recent years, successive Australian governments have adopted various policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions. On 10 July 2011, the former government released its Securing a Clean Energy Future Plan (the Clean Energy Future Plan). An element of the Clean Energy Future Plan provided transitional assistance for manufacturing businesses37 to adjust to the carbon price through the $1.2 billion Clean Technology Program, comprising:

- Clean Technology Investment Program (CTIP)—which was allocated $800 million between 2011–12 and 2017–18 to assist manufacturers to invest in energy-efficient capital equipment and low-emissions technologies, processes and products;

- Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Program (CTFFIP)—which was allocated $200 million between 2011–12 and 2016–17 to help manufacturers in the food and foundries industries to invest in energy-efficient capital equipment and low-emission technologies, processes and products; and

- Clean Technology Innovation Program—which was allocated $200 million between 2012–13 and 2016–17 to support research and development, proof-of-concept and early stage commercialisation activities that lead to the development of new clean technologies and associated services, including low emission and energy efficient solutions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

1.2 The CTIP and the CTFFIP (the programs), which are the focus of this audit38, reflected a policy articulated in the Clean Energy Future Plan that recognised:

for many Australian manufacturers, improvements in energy efficiency will be the most effective way that carbon cost impacts can be managed to ensure long-term competitiveness. While a carbon price will provide incentives for these manufacturers to reduce energy consumption, the Government will also help manufacturing businesses identify and implement technologies that will improve energy efficiency and reduce their exposure to changing electricity prices.39

1.3 The then Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (DIISRTE, now the Department of Industry (the department)) was responsible for the design and implementation of the programs. Specifically, the Manufacturing Policy Branch of the department was responsible for program design, while the AusIndustry Division (AusIndustry) was responsible for implementation. Innovation Australia (IA) was also engaged, as a subject specialist, to assess grant applications..

Program funding

1.4 The programs opened to applications in February 2012 and closed in October 2013. A total of 1171 applications were received seeking $773.5 million.40

1.5 The maximum amount of funding available for each project depended on total project expenditure, business turnover and the likelihood of the manufacturer being liable to pay the carbon price, as shown in Table 1.1. The minimum amount of funding available was dependant on the type of project. Specifically, a minimum of:

- $25 000 was available for: changes to the energy sources of existing or replacement plant or processes; or replacement of, or modification to, existing plant, equipment and processes; and

- $1.5 million was available for the replacement of, or modification to, established manufacturing production facilities for new products which offered significant energy or carbon savings during their in-service life.

Table 1.1: Assistance available under the programs

|

Grant funding sought |

Proportion of eligible expenditure that can be funded (%) |

Conditions relating to the proportion of eligible expenditure funded |

|

Less than $500 000 |

50 |

In the financial year prior to lodging the application, the applicant had turnover of less than $100 million |

|

Between $500 000 and $10 million |

33 |

Nil |

|

Greater than $10 million |

25 |

Nil |

|

Unlimited |

50 |

In the year prior to lodging the application, the applicant had covered emissions from facility operations of 25 000 tonnes or more but less than 100 000 tonnes1 |

Source: CTIP and CTFFIP program guidelines.

Note 1: ‘Covered emissions’ was defined in the Clean Energy Act 2011 (Cth). This Act was repealed in July 2014. The Clean Energy Regulator defines ‘covered emissions’ as scope one emissions, which are the emissions released by the combustion of coal, gasoline or other fuels as part of a facility’s operations. Manufacturers may also produce scope two emissions, which are generated outside of a facility’s operations. For example, when a manufacturer uses electricity that has been purchased from an electricity provider, the emissions generated are scope two emissions.

Overview of the assessment process

1.6 After an application was submitted, the department assessed it against the eligibility criteria, which related to the type of business, activities undertaken, type of project, and project expenditure. If assessed as eligible, the department then assessed the application against the merit criteria and provided that assessment, along with relevant information from the application, to one of three committees that were given delegated authority by IA to assess applications.

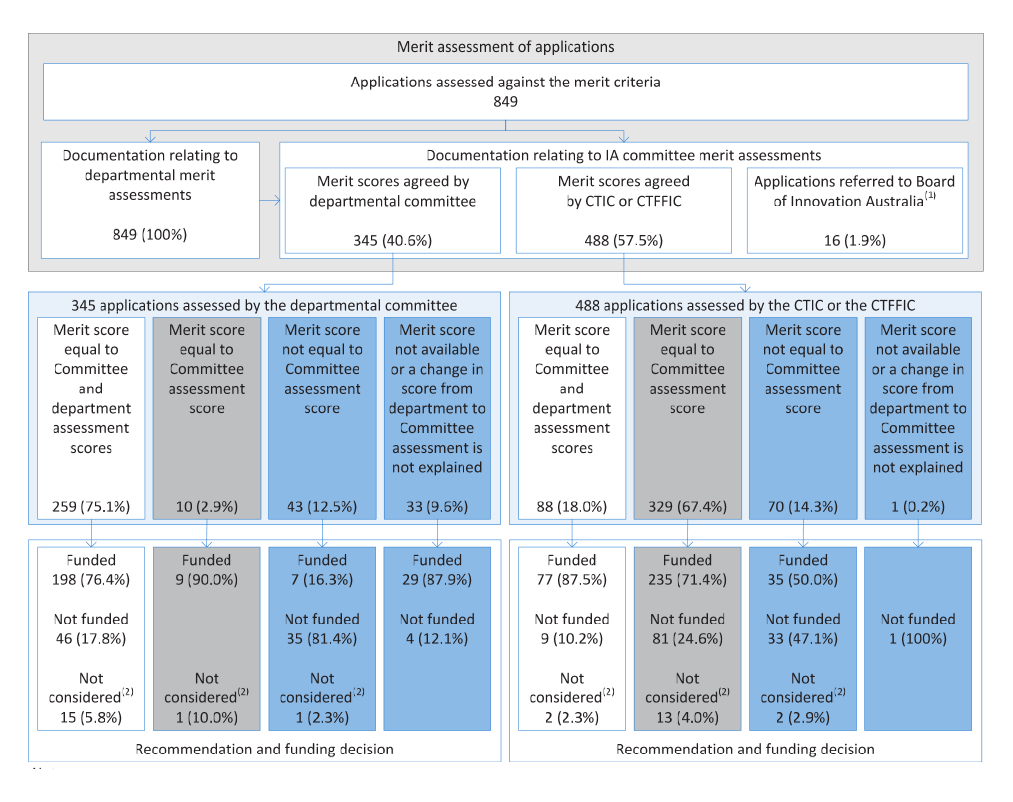

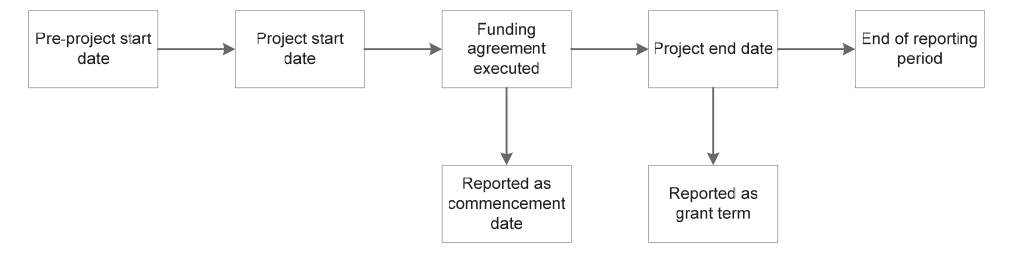

1.7 The IA committees undertook the final merit assessment and provided a funding recommendation to the program delegate. Once a recommendation was provided, the delegate, who was a senior employee of the department, confirmed that funding was available before deciding whether to approve, or not approve, an application.41 The process followed was dependent on the value of the grant sought, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Grant assessment process

Source: ANAO analysis.

Projects funded under the programs

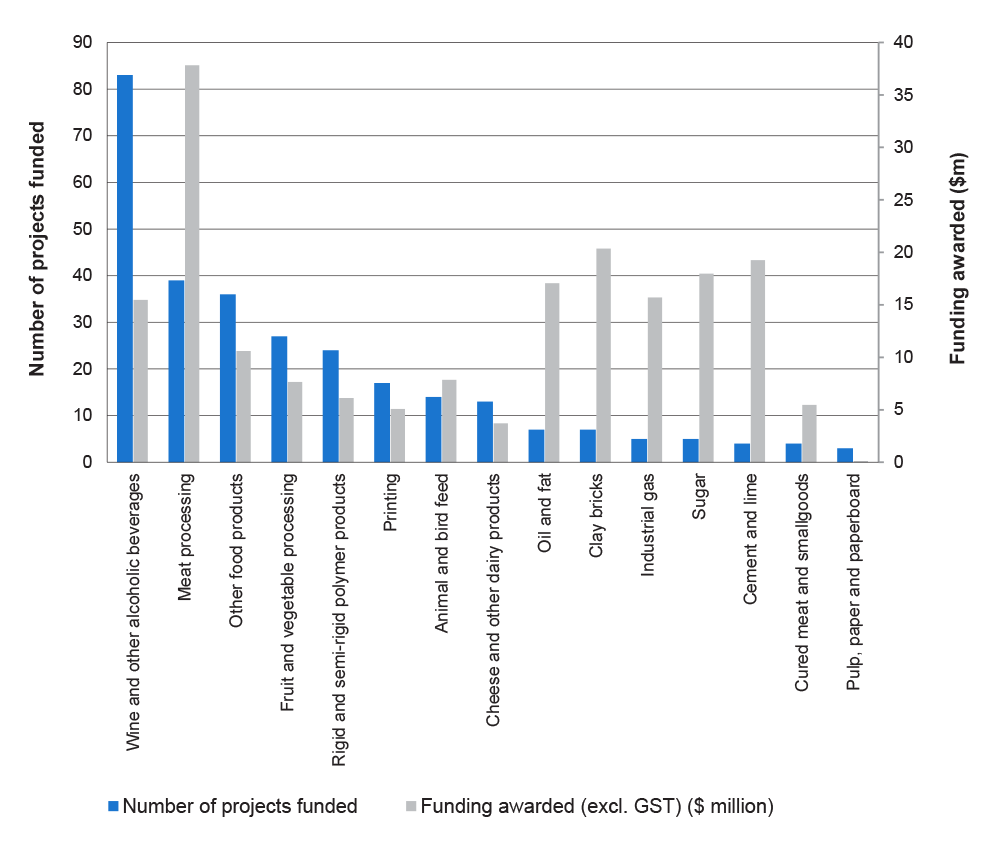

1.8 A total of 603 projects were awarded $314.9 million under the programs.42 Grants were awarded to manufacturers in a range of industry segments and for different types of emissions reduction measures. As shown in Figure 1.2, the wine industry received the highest number of grants, but the meat processing industry received more than double the amount of funding.

Figure 1.2: Top ten industries funded under the programs

Source: ANAO analysis.

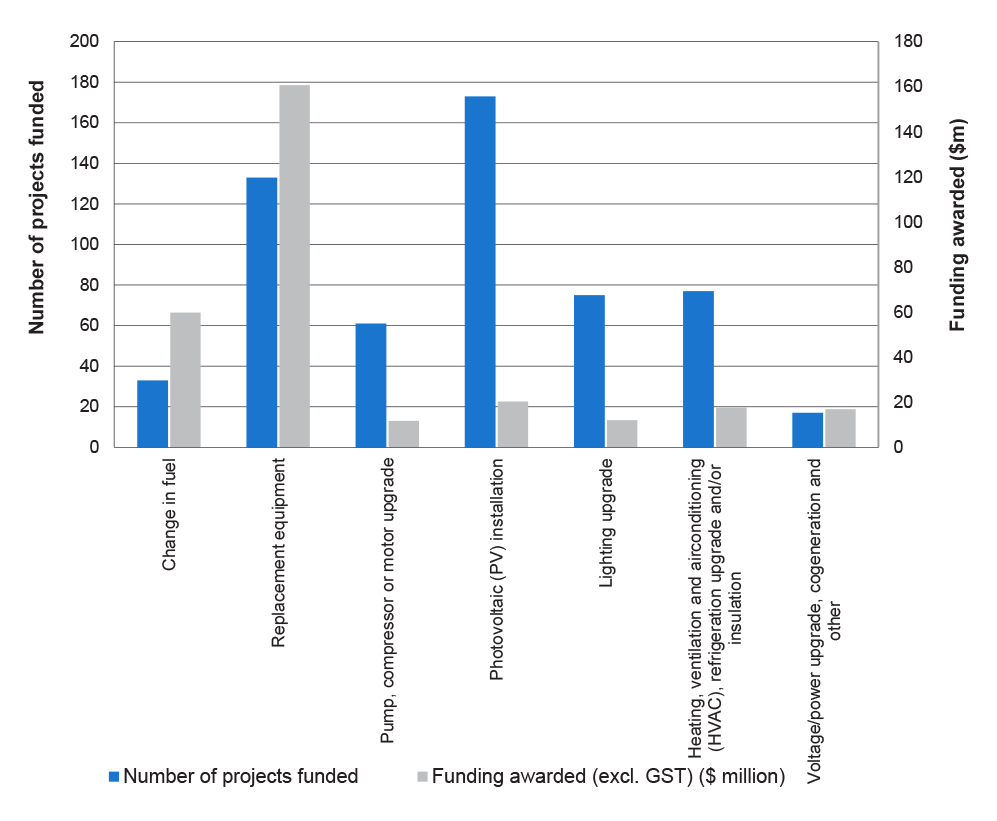

1.9 The emissions reduction measures funded under the programs are shown in Figure 1.3. The most common measures funded included photovoltaic (PV) system installation and equipment replacement. However, funding awarded for PV system installation projects ($20.3 million GST exclusive) was significantly less than that awarded to equipment replacement project ($160.7 million GST exclusive).

Figure 1.3: Types of projects funded under the programs

Source: ANAO analysis.

Closure of the programs

1.10 On 28 August 2013, the then Opposition announced its intention to discontinue funding for the programs as part of its commitment to deliver savings by abolishing the core elements of the Clean Energy Future Plan. The programs were closed to new applications on 22 October 2013. Details of the closure of the programs were published on the AusIndustry website on 11 November 2013 and AusIndustry contacted applicants directly with advice on the status of their application the following day. The advice was tailored to the status of each application, for example, applicants:

- who had received a letter of offer, but did not have an executed funding agreement were advised that program arrangements were still being determined; and

- whose application was not fully considered prior to the date of program closure were advised that their application was unsuccessful.

1.11 The final program arrangements were decided by the incoming Government following a review of all granting activities. As a result of this process, it was decided to progress with the 106 grant offers that had been made before program closure.43

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.12 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and equity of the award of funding under the Clean Technology Program in the context of the program objectives and the Commonwealth’s grants administration framework.

1.13 In June 2013, the Auditor-General received a request from Senator Simon Birmingham, Liberal Senator for South Australia, then Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for the Murray-Darling Basin and then Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for the Environment to undertake an audit of the Clean Technology Investment Program. The Senator raised a number of concerns about the process for awarding grants under the programs and, in relation to the Clean Technology Investment Program, the distribution of funding in electoral terms. A potential audit of the Clean Technology Program was included in ANAO’s Audit Work Plan for 2013–14 as the resources to undertake an audit were not available at the time of the Senator’s request. Audit resources became available later in 2013, with this audit commencing in November 2013. This audit also examined the specific matters raised by the Senator.

Audit criteria

1.14 To form a conclusion against this audit objective, ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the assessment process promoted open, transparent and equitable access to funding and led to those projects most likely to contribute to the cost-effective achievement of the program objective being consistently and transparently recommended for funding approval;

- departmental assessments and advice from Innovation Australia informed the funding decisions that were taken;

- the expected outcomes and distribution of funding were consistent with the objective of the programs and the program guidelines; and

- the announcement and reporting of grants awarded under the programs was adequate, accurate and transparent.

Audit scope and methodology

1.15 The scope of the audit included the design of the programs as well as the assessment and decision-making processes in respect to the 1171 applications that were received. The audit scope was focused on the application and assessment processes up to the point at which funding is awarded and a funding agreement signed, and also included analysis of the distribution of funding (including in electorate terms) and the announcement and reporting of grant funding.

1.16 The scope did not include the administration of the Clean Technology Innovation Program (see paragraph 1.2). The audit scope also did not include the management of grant agreements with successful applicants (and, therefore, did not examine the department’s measurement and verification regime for completed projects) or the evaluation of program outcomes (apart from any steps taken by the department to plan and prepare for program evaluation).

1.17 The audit examined departmental records on the design, implementation and administration of the programs, including:

- application and eligibility assessment records for 1012 applications44; and

- assessment records for the 849 applications that were assessed by the IA committees against the merit criteria.45

1.18 ANAO also interviewed officials from the department and discussed the implementation of the programs with the chairs of the Clean Technology Investment Committee (CTIC) and the Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Committee (CTFFIC).

1.19 The audit has referenced the grants framework that was in place at the time that the programs operated (in particular, the Finance Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) and the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs)). The framework changed after the programs had closed, with implementation of the grants-related elements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) taking effect from 1 July 2014. In this respect, unless stated otherwise, similar arrangements exist under the current framework (PGPA Act and the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs)).

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to ANAO of $754 000.

Report structure

1.21 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Structure of the report

|

Chapter title |

Chapter overview |

|

2. Program Design |

Examines the design of the programs, including the key roles and responsibilities for managing the programs as well as the department’s approach to evaluating the outcomes of the projects funded in relation to reduced carbon emissions. |

|

3. Access to Funding |

Analyses the approach to assessing applications, including the reframing of applications throughout the merit assessment process. |

|

4. Reduction in Emissions |

In the context of the program objective, examines the assessment of the extent to which applications would reduce carbon emissions intensity. |

|

5. Advice to the Program Delegate and Funding Decisions |

Outlines the advice provided to the decision maker by the department and Innovation Australia, as well as the funding decisions that have been taken. |

|

6. Reporting and Funding Distribution |

Examines compliance with relevant grant reporting obligations and analyses the distribution of funding. |

2. Program Design

This chapter examines the design of the programs, including the key roles and responsibilities for managing the programs as well as the department’s approach to evaluating the outcomes of the projects funded in relation to reduced carbon emissions.

Introduction

2.1 From the time that the programs were announced in July 2011, the department was responsible for the design and implementation of the programs. Accordingly, ANAO examined the extent to which the department designed an appropriate framework for administering the programs through the:

- program guidelines and other documentation;

- objective of the programs;

- program governance arrangements; and

- key program documentation.

Program guidelines

2.2 A key obligation under the CGGs was for all grant programs to have program guidelines in place. Program guidelines play a central role in the conduct of effective, efficient and accountable grants administration, by articulating the policy intent of a program and the supporting administrative arrangements for making funding decisions.46 Reflecting their importance, the program guidelines represent one of the policy requirements that proposed grants must be consistent with in order to be approved for funding.47

2.3 The CGGs indicated that, where appropriate, consulting stakeholders on grant arrangements could help achieve more efficient and effective grants administration. In this context, the department facilitated an extensive stakeholder consultation process that was used to inform program design. This process involved:

- consultations with key industry groups between August 2011 and September 2011;

- a discussion paper that was released in September 2011;

- 14 targeted public consultations that were attended by 439 representatives from business, government and industry groups between October 2011 and December 2011; and

- 94 written submissions, received between October 2011 and December 2011, in response to the discussion paper.

2.4 The department was responsive to the feedback provided during the consultation period. For example, the programs were originally designed to provide a grant of up to 25 per cent of eligible costs, but after feedback was received that manufacturers would have difficulty financing investments at a maximum government grant contribution of 25 per cent, the tiered funding ratios presented in Table 1.1 on page 35 were adopted.

2.5 After the public consultation period had concluded, the department finalised the program guidelines. At that time, the requirements of the grant framework relating to the approval of program guidelines were dependent on a risk assessment by the department. Both programs were rated as ‘medium risk’ and the program guidelines and risk assessments were reviewed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the then Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance). Final approval of the guidelines was given by the then Prime Minister in January 2012.

Customer guidelines

2.6 The CGGs described program guidelines as being a ‘single reference source’ for policy guidance, administrative procedures, appraisal criteria, monitoring requirements, evaluation strategies and standard forms.48 In a previous ANAO audit49, instances where agencies were producing more than one document that outlined important aspects of the grant selection process were observed. In this regard, ANAO identified that:

- the better approach is for a single program guidelines document to be prepared (and approved) that represents the reference source for guidance on the grant selection process, including the relevant threshold and assessment criteria, and how they will be applied in the selection process; but

- where more than one document is produced and each outlines important aspects of the grant selection process, it is important that agencies recognise that, collectively, all such documents constitute the program guidelines for the purposes of the CGGs. Accordingly, these documents should collectively be subject to the grant program approval requirements and made available to stakeholders.

2.7 The program guidelines provided an overview of the programs, as required by the CGGs. However, a separate document (referred to by the department as the customer guidelines) was also prepared. The department’s intent in providing customer guidelines was to give prospective applicants a more comprehensive reference point for application development and the assessment and selection process. Despite this intention, the customer guidelines did not provide potential applicants with an accurate overview of the assessment process in relation to the:

- opportunity for applicants to provide additional information after application submission;

- department assisting applicants to reframe applications to exclude proposed capital investment activities that were not considered to provide a relative contribution to carbon savings that was commensurate with the share of project costs; or

- approach used to assess applications against the merit criteria, with specific reference to the indicators used to assess merit criterion one and a range of undocumented factors considered important by the IA committees in arriving at funding recommendations.50

2.8 The customer guidelines were not subject to the approval process outlined in the CGGs on advice taken from Finance. This situation made it easier for the department to make changes over time, particularly in relation to the assessment approach. However, as previously outlined by ANAO, the approach of having two separate sets of guidelines for a program, with important detail not included in the guidelines subject to the grants administration framework approval processes was not consistent with better practice.

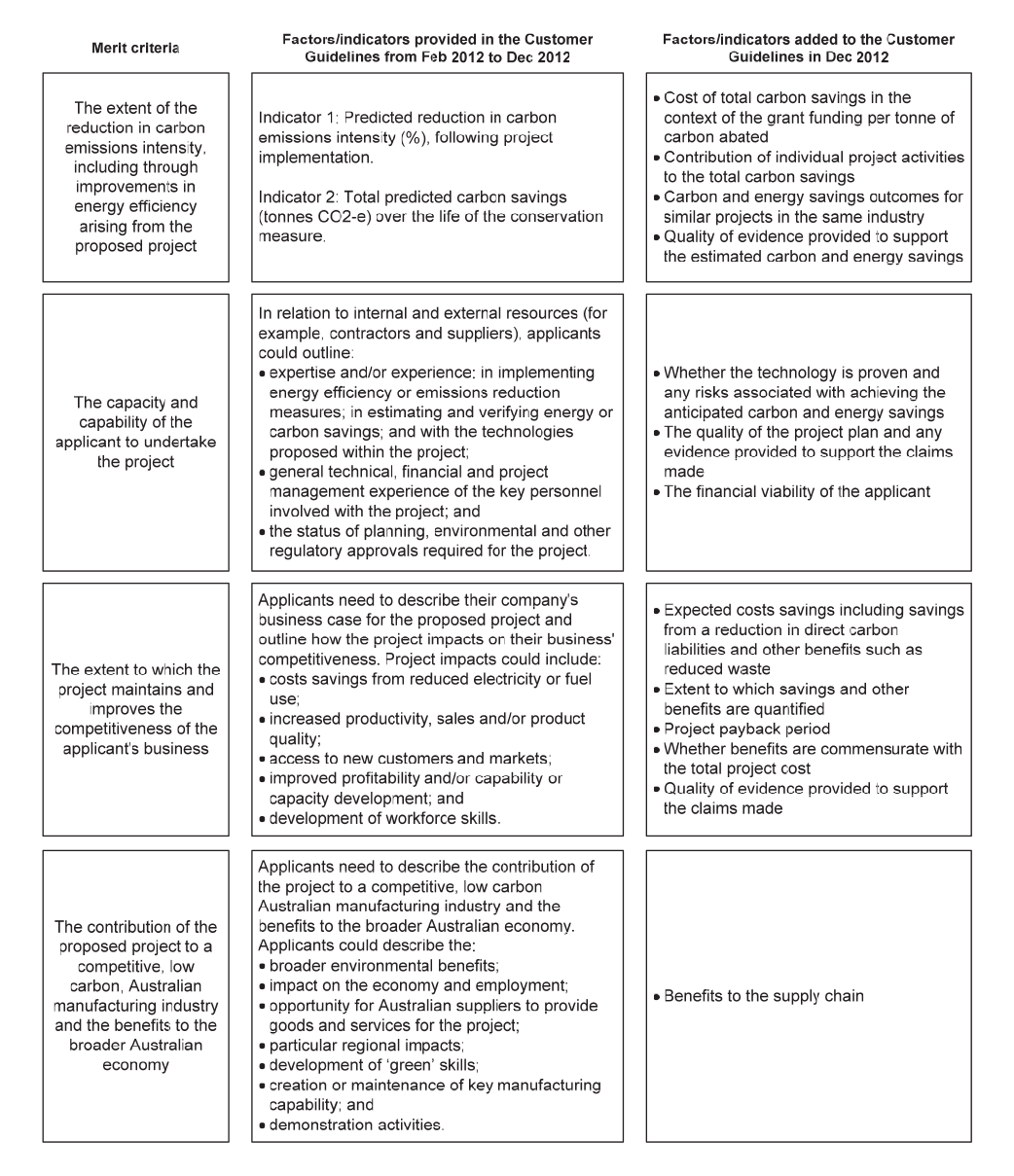

2.9 For example, the program guidelines outlined the merit criteria for the programs, but the customer guidelines provided further details regarding the implementation of those criteria (see Figure 2.1). Of particular significance was that the program guidelines did not identify that two indicators were being used to assess applications against the first (and most heavily weighted) merit criterion, or the relative weighting applied to those two indicators.51

Other program documentation

2.10 To assist applicants, the department also repeated some of the information in the program and customer guidelines in the electronic application form (a ‘smartform’) and in a series of fact sheets.52 In addition to the published program documentation, the department developed a procedures manual that:

- described the roles and responsibilities of departmental officials when processing and assessing applications;

- included a framework for allocating merit scores to applications; and

- provided a template for the departmental assessment.

Figure 2.1: Information on merit assessment published in the customer guidelines

Source: ANAO analysis of customer guidelines.

2.11 The primary purpose of the departmental assessment was to present the relevant IA committee with a report that included:

- an assessment of: the application against each of the merit criteria in the form of a score, with the scores summed to give the overall merit score; and the quality of the evidence supporting the application;

- options to reframe the project to exclude any ineligible activities53 or eligible activities that the department considered did not provide value for money;

- additional commentary to highlight information that had the potential to significantly impact the final decision, but was not easily identifiable in the application; and

• an assessment recommendation.

Probity plan

2.12 The CGGs also outlined that an important requirement in grant administration is ensuring probity and transparency, such that decisions relating to the granting activity are impartial, appropriately documented and publicly defensible. In this respect, the department did not develop a probity plan or engage a probity advisor.54

Objective of the programs

2.13 Program objectives that are clearly linked to the outcomes set by government were required by the CGGs. As such, it was important that the objective of the programs was consistent with the outcome set in the Clean Energy Future Plan, which was to reduce carbon pollution and assist manufacturers to reduce their exposure to rising energy costs.55

2.14 The objective of the programs, as stated in the program guidelines, was:

To assist Australian [manufacturing] businesses to invest in energy efficient capital equipment and low emissions technologies, processes and products in order to maintain the competitiveness of Australian manufacturing businesses in a carbon constrained economy.

2.15 In practice, the objective of the programs was implemented through the assessment of applications against the merit criteria, using the weightings in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Merit criteria and weightings

|

Merit criteria |

Score for applications seeking grant funds: |

|

|

up to $1.5 million (%) |

over $1.5 million (%) |

|

|

The extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity, including through improvements in energy efficiency arising, from the project. |

70 (70.0) |

70 (58.3) |

|

The capacity and capability of the applicant to undertake the project. |

15 (15.0) |

15 (12.5) |

|

The extent to which the project maintains and improves the competitiveness of the applicant’s business. |

15 (15.0) |

15 (12.5) |

|

The contribution of the proposed project to a competitive, low carbon, Australian manufacturing industry and the benefits to the broader Australian economy. |

N/A |

20 (16.7) |

|

Total score |

100 (100) |

120 (100) |

Source: CTIP guidelines and CTFFIP guidelines.

2.16 As illustrated in Table 2.1, the extent of the reduction in carbon emissions intensity (merit criterion one) had a higher weighting compared to the other criteria. As a result, the criteria weightings reflected that the main objective of the programs was to reduce the carbon emissions intensity of manufacturers and that the competitive position of businesses was of significantly less importance.56 Accordingly, the objective that was implied by the weighting of the merit criteria was consistent with the outcomes set out in the Clean Energy Future Plan.

Value with public money and additionality

2.17 As noted in ANAO’s Grants Administration Better Practice Guide, value with public money should be considered at two levels:

- in the context of grant allocation, the extent to which a population of projects maximises the achievement of specified objectives within the available funding; and

- in the context of selecting individual projects for funding, selected applications should be eligible, have met the selection criteria, involve reasonable cost and have a risk profile that is acceptable to the Commonwealth.57

2.18 With regard to the value of individual projects, there were four merit criteria for the programs, but none specifically addressed the reasonableness of project costs (as shown in Table 2.1). However, the assessment of applications against merit criterion one included consideration of the grant funds per tonne of carbon abated. This indicator provided a measure of the fiscal cost of abatement58 and was used as a basis for identifying and promoting changes to projects that the department considered were ‘unlikely to represent value for money’.59 In June 2014, the department advised ANAO that the cost of abatement measure was ‘simply a tool that allowed us to compare and consistently score total carbon savings over the life of the project’. Despite this advice:

- the department’s customer guidelines released in August 2013 (near the time of program closure) stated that ‘total carbon savings in the context of value for money (grant dollars for each tonne of carbon abated)’ was a factor considered in the assessment of merit criterion one; and

- both IA committee chairs advised ANAO that value for money was considered during committee deliberations.

2.19 Value with public money is also promoted by considering the extent to which the funding being sought by an applicant will result in an outcome that is additional to those that are likely to occur regardless of whether the application is successful. This is referred to as ‘additionality’. There was no criterion or provision in the program guidelines that prevented projects that were being implemented without funding assistance from being assessed as eligible or meritorious. This reflected that the programs were administered as ‘transitional adjustment assistance’ for the carbon price. In this regard, the program manager noted in May 2012 that:

Some applicants are likely to choose to order and/or part pay for plant and equipment with significant supply lead times prior to making an application or the project start date. There is no additionality requirement in the Program and it is consistent with the policy intent of the Program to allow applicants to claim remaining costs for these plant items that are paid within the project period.

It is recognised that there may be risks associated with meeting the Australian National Audit Office Granting Guidelines value for money test for funding project activities for an ERM [emissions reduction measure] that is largely complete at [the] time of application. An extreme example would be a project to put a roof on an otherwise completed replacement manufacturing facility.

This risk is mitigated by the requirement for the project to rate highly against all program merit criteria.

2.20 However, ANAO analysis was that:

- the lack of an additionality criterion was inconsistent with the policy because the implementation arrangements in the policy proposal stated that funding would not be provided for projects that were intended to be undertaken privately in the absence of the programs;

- none of the program merit criteria specifically required consideration of additionality, nor was information that would inform the consideration of additionality sought in application forms; and

- it was not until December 2012 that benchmarks were set to reflect the score required for applications to be considered to rate highly against all program merit criteria.60

2.21 The risk of funding projects that would have proceeded without government funding was not addressed in practice, as highlighted by the examples in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Projects largely complete at the time of application submission61

|

Case study |

Relevant extract from committee discussion |

Merit score |

Program delegate decision |

Grant amount ($) |

|

1 |

The company was going to do this anyway and had planned to do this two years ago, and this program came along and provided opportunity to get free money. |

89.7/120 |

Supported |

9 500 000 |

|

2 |

Project was 85% complete at the time of application. |

101.9/120 |

Supported |

9 100 000 |

|

3 |

Project was partially complete and is part of a $45 million project. It was not clear what benefits could be attributed to program funding. |

78.4/100 |

Supported |

800 000 |

|

3 |

The company had a legal undertaking to do this project regardless of whether the Commonwealth provides funding. |

72.0/100 |

Supported |

66 897 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

2.22 As part of an internal review of the programs in November 2013, the department identified that:

A consequence of no need-for-funding requirements is that some approved projects would have already been implemented without grant funding. In fact, some approved projects had already undergone internal final approvals and were already underway at the time of application.

2.23 Although in some cases there were significant periods of time between the date of lodgement of an application, decision and execution of a funding agreement, there were also:

- 25 funding agreements with grants totalling $6.5 million that were executed on or after the project end date listed in the funding agreement; and

- a further 109 funding agreements with grants totalling $38.5 million executed within three months of the project end date listed in the funding agreement.62

Assessment and selection process

2.24 An important consideration in the design of any grants program is the process by which potential grant recipients will be able to access grants. At the time that the assessment and selection processes for the programs were determined, the CGGs outlined that:

Unless specifically agreed otherwise, competitive, merit based selection processes should be used, based upon clearly defined selection criteria.63

2.25 While guidance on a competitive selection process was not provided in the 2009 version of the CGGs, the following guidance was available to the department in the ANAO’s 2010 Grants Administration Better Practice Guide64:

An appropriately conducted competitive, merit-based grant selection process involves all eligible, compliant applications being assessed in the same manner against the same criteria, and then being ranked in priority order for receipt of the available funding based upon the outcome of those assessments.65

2.26 In December 2011, Finance advised the department to provide a clear statement of the selection process in the proposed program guidelines, advising the department that:

It notes in the guidelines that the program is a competitive merit (page 2) based grants program. However, it also states that applications can be lodged at any time. It needs to be clearer what type of merit selection process will be used. For example, will applications be assessed against the selection criteria, or will applications be ranked against other applicants’ applications. During the seven year period, will there be points in which all applications will be ranked, or will applications be assessed on a case-by-case basis, with recommendations going to the delegate on an ad-hoc basis. It would be useful if more information be [sic] included so potential recipients can see more clearly how the merit selection process will operate.

2.27 The process that the department implemented involved applications being individually assessed against the merit criteria, with funding decisions made on an ongoing basis. In the context of guidance available at that time concerning grant selection processes, this approach was not consistent with the policy proposal and program guidelines, which referred to a ‘competitive grants program’. In this respect, the department advised ANAO in June 2014 that:

[The 2009 version of the CGGs] do not provide any additional guidance in relation to competitive selection processes.

On the basis of those Guidelines the program was correctly described as a competitive granting program in the [policy proposal] and the selection process of individual assessment against the merit criteria is consistent with that description.

2.28 Notwithstanding the above advice, the programs were launched at a time when the department’s Customer Service Charter clearly stated that a competitive grants program was one in which applicants compete for program funding as follows:

AusIndustry offers both entitlement and competitive grant programs.

For grants-based products, customers compete for limited funds, based on the merits of their application.

For entitlement programs, such as the R&D Tax Concession, customers make claims in accordance with pre-determined criteria.66 [ANAO emphasis]

2.29 Further, the department advised ANAO in June 2014 that:

Innovation Australia may also choose to rank applications considered at a particular meeting. Ranking would be undertaken where it is necessary to restrict approvals in accordance with available funding. This has not been required to date. [ANAO emphasis]

2.30 This is inconsistent with the advice that the department provided to the then Minister for Industry and Innovation in February 2012 that:

Innovation Australia’s newly formed Clean Technology Investment Committee requires appointment of a Chair and members to assess and merit rank applications submitted under both the Clean Technology Investment Program and the Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Program. [ANAO emphasis]

2.31 The reasons for the department’s decision not to rank applications may relate to the difficulty in establishing the relative merits of applications for projects that involve substantively different activities. In this regard, the department separately advised ANAO in June 2014 that:

There is significant variation in project size, complexity, activity and outcomes depending on the nature of the emission reductions measures to be undertaken and industry sector. The value of projects considered to date ranges from $50 000 to $70 million. Projects can encompass activities ranging from replacement of lighting fixtures, modifying an existing manufacturing process, installing a co-generation plant, covering anaerobic lagoons or replacing an entire manufacturing site. Reductions in emissions intensity will vary significantly depending on the nature of the emissions reduction measures included in the project. Given the significant variation between projects, applications are assessed individually against the program merit criteria rather than against other projects within a funding round.

2.32 However, these factors were not documented at the time that the assessment and selection process was decided upon.

2.33 A program in which applications were individually assessed against merit criteria would more accurately be described as a merit-based, non-competitive program (which is the definition adopted by the CGRGs, as well as in ANAO’s Grants Administration Better Practice Guide). However, the process used also exhibited some of the characteristics of a demand-driven program as 74 per cent of the applications that were considered by the program delegate were approved.67 Following advice from ANAO in June 2013 (prior to the commencement of the audit), the department acknowledged that the programs were not competitive grants programs, in the context of the 2013 CGGs, by updating the program guidelines to reflect that applications would be individually assessed against the merit criteria. The department advised ANAO in October 2014 that ‘despite this reclassification, there was no change to the assessment process’.

2.34 Given that there was no change to the assessment process or the definition of a competitive grants program that was provided in the ANAO’s 2010 Grants Administration Better Practice Guide, the department did not obtain agreement, from the then Government, to change the assessment and selection process from a competitive grants program (as identified in the policy proposal) to an open, non-competitive or a demand-driven grants program.

Program governance arrangements

2.35 Key roles and responsibilities in the administration of the programs were set out in program governance documentation and the program guidelines. Responsibility for the program’s design and delivery was shared between the manufacturing policy area of the department and AusIndustry. The manufacturing policy area was responsible for designing the programs and providing ongoing policy advice, while the day-to-day management and delivery of the programs was carried out by AusIndustry. Oversight was managed through monthly reports from AusIndustry to the department’s executive group. These reports provided a financial management summary and summarised key issues, risks and opportunities relating to the program.

Role of the program delegate

2.36 On 1 February 2012, the then Minister for Industry and Innovation appointed the departmental official who was acting in the role of General Manager, Clean Technology Investment Branch, AusIndustry as the program delegate to:

- take all necessary decisions and carry out all necessary functions in relation to the administration of the programs;

- authorise employees of the department to take decisions and to carry out functions as are specified in the program guidelines; and

- award funding to applicants under the programs, subsequent to a merit assessment and recommendation from IA.

2.37 The program manager was responsible for the day-to-day operations of the programs including overseeing the delivery network, but the delegate attended the majority of IA committee meetings. In this regard, the department advised ANAO in September 2014 that:

Neither the program delegate or program manager were members of the Clean Technology Investment Committee or Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Committee. They could elect to attend meetings, and often did, as observers to provide advice to the committee on the program rules if asked, and to gain insight into the factors considered by the committee(s) in recommending a grant application for approval.

2.38 However, as outlined in ANAO’s Grants Administration Better Practice Guide, irrespective of whether the approver is a Minister or an official, it is prudent for the approver to remain at arm’s length from the assessment process. This separation avoids the potential for perceptions to arise that the approver has influenced the funding recommendations subsequently put forward for the approver’s consideration.

Role of Innovation Australia

2.39 It is relatively common for an advisory committee to be used to provide advice and/or recommendations to grant program decision‐makers. Where a program relates to a specific area, such committees are able to bring relevant knowledge, experience and judgement to bear in formulating, or assisting to formulate, funding recommendations. In this context, it is important that the basis on which an advisory committee is to be involved in an assessment and selection process is clearly defined, and that the committee’s deliberations and recommendations are appropriately documented.

2.40 Against this background, the role of Innovation Australia (IA) was to:

- undertake a merit assessment of each eligible application;

- provide a recommendation to the program delegate (or to the Cabinet of the Australian Government, where relevant); and

- provide more general advice to the program delegate in relation to the programs and the development of the customer guidelines.

2.41 To carry out this role, an IA committee was created and, on 22 March 2012, it received delegated authority from the Board of IA to make funding recommendations to the program delegate up to a maximum of $5 million.68 All of the members of the IA committee had skills in manufacturing or engineering and business administration, but only three members had experience in clean technology and two members had experience in energy and carbon efficiency.

2.42 In October 2012, the IA committee was separated into three committees due to the significant workload associated with the programs. The responsibilities of these committees in assessing, and making recommendations on, applications were as follows:

- departmental committee—low-risk grants under $300 000. This committee consisted of members from the program management area and manufacturing policy area of the department and also included managers from AusIndustry’s State Office Network and officers with responsibility for the delivery of the programs;

- CTIC—general investment applications up to a maximum value of $5 million. This committee consisted of six members who had experience in manufacturing or engineering and business administration, two members who had experience in clean technology and one member who had experience in clean energy and carbon efficiency; and

- CTFFIC—food and foundries applications up to a maximum value of $5 million. This committee consisted of five members who had experience in manufacturing or engineering and business administration, two members who had experience in energy and carbon efficiency and one member who had experience in clean technology.

2.43 While the members of the IA committees were not employees of the department, the functions they were responsible for performing carried specific record keeping obligations. In this context and as outlined in the CGGs and ANAO’s Grants Administration Better Practice Guide, where the advice provided by a committee directly informs a decision about expenditure—for example, where the committee assesses applicants against particular criteria, and/or recommends supporting particular projects or distributing funds to particular applicants—committee members are officials of the relevant agency.69 Importantly, where advice and recommendations received from a panel are intended to be relied upon by a decision‐maker in forming a view on the merits of providing grant funding, the assessment of applications and funding recommendations of the panel should be formulated in a manner that is consistent with the program guidelines. This provides a sound basis for the departmental decision-maker concluding that a recommendation to approve funding is consistent with the program guidelines as a policy of the Commonwealth (as was required by FMA Regulation 9).70

Assessment of applications by the departmental committee

2.44 The creation of the departmental committee assisted with the management of the workloads for the CTIC and the CTFFIC. This arrangement, however, meant that a number of merit assessments were undertaken by the department rather than IA, as described in the program and customer guidelines, such that specialist knowledge was not brought to bear in the assessment of applications.

2.45 As shown in Figure 2.3 on page 63, 345 applications (41 per cent) were assessed by the departmental committee. In 75 per cent of these assessments, the departmental committee agreed with the score provided by the departmental assessor. By way of comparison, the CTIC and the CTFFIC agreed with the score allocated by the departmental assessor in 18 per cent of cases. Given that IA had a role in providing specialist knowledge in the assessment of applications, the use of a different arrangement did not allow for the specialist knowledge that was available to be applied. As a consequence, the transparency of the assessment process was reduced for applicants and the knowledge applied differed across applications.

Documentation retained to support recommendations

2.46 The procedures manual set out the role of departmental officials in assisting the IA committees with the final merit assessment. This included compiling an ‘application deck’, which included the departmental assessment report, the submitted application and other relevant supporting documentation. The application deck was intended to provide committee members with ‘the core documents needed to review and assess the application’ and was only to include information ‘that is necessary and sufficient for the committee to make an informed decision’.

2.47 While the department developed a scoring framework to be used in the departmental assessment that was presented to the IA committees, the evidence provided by the department did not reflect that the IA committees used the same framework in scoring applications against the merit criteria. In this respect, the program management area of the department advised IA committee members, in April 2012, that ‘committee members may wish to score on some other basis’. In October 2014, the department confirmed this in advice to ANAO that:

The purpose of the Carbon Scoring tool is to ensure that AusIndustry Customer Service Managers take a uniform approach to scoring against this criterion. Committee Members may wish to score on some other basis.

2.48 With regard to IA committee deliberations one of the IA committee chairs advised ANAO in September 2014 that:

The assessment was complex because there were many inputs that the committee considered, with the final scores as presented by the CSM [Customer Service Manager] being only some of them. Other critical issues that had different bearings on various applications included:

- the type and age of existing vs new equipment, the suppliers, the amount of data provided on estimated performance of the new equipment; depreciation rates etc

- the assessment of the validity of all the assumptions throughout the application

- the business profile of the applicant, its industry, competitors, the applicant’s financial history and robustness of their future cashflow (in addition to the necessary citing of the Accountants Declaration)