Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Australian Electoral Commission's Preparation for and Conduct of the 2007 Federal General Election

During the preparation of the ANAO's Planned Audit Work Program 2006–07, JSCEM suggested that the ANAO consider a possible performance audit into the efficiency and effectiveness of the AEC's management of elections. JSCEM's suggestion was considered in the planning and preparation for this performance audit, which focuses primarily on the AEC's administration of the CEA in the lead-up to and conduct of the 2007 general election.

Summary

Introduction

1. On Sunday 14 October 2007, the then Prime Minister announced that a general election for the House of Representatives and half the Senate would be held 41 days later, on Saturday 24 November 2007. It was the ninth general election conducted by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) since it was established in 1984.

2. The AEC was established as an independent statutory authority as part of far-reaching reforms to the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (CEA). The AEC's formal relationship to executive government is through the Special Minister of State, who is responsible for the CEA under the Administrative Arrangements Order. The AEC's relationship to Parliament is primarily through the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM). The current JSCEM is the most recent in a continuous succession of committees, dating back to 1983, charged with overseeing and scrutinising electoral matters, including the electoral laws, electoral practices and their administration. Among other things, the committees have inquired into the conduct of each general election since 1987.1

3. The Constitution and the CEA set out the processes for calling, conducting and declaring elections to the Parliament. The CEA gives the AEC sole responsibility for the conduct of those elections, prescribes the timing of key events, and sets out the roles and duties of officials during the polling and the counting of ballot papers. Planning and preparation are paramount, as the AEC has no control over the timing of elections. It may be called upon to have the electoral rolls in order and all other preparations in place for the delivery of a general election with as little as 33 days notice.2

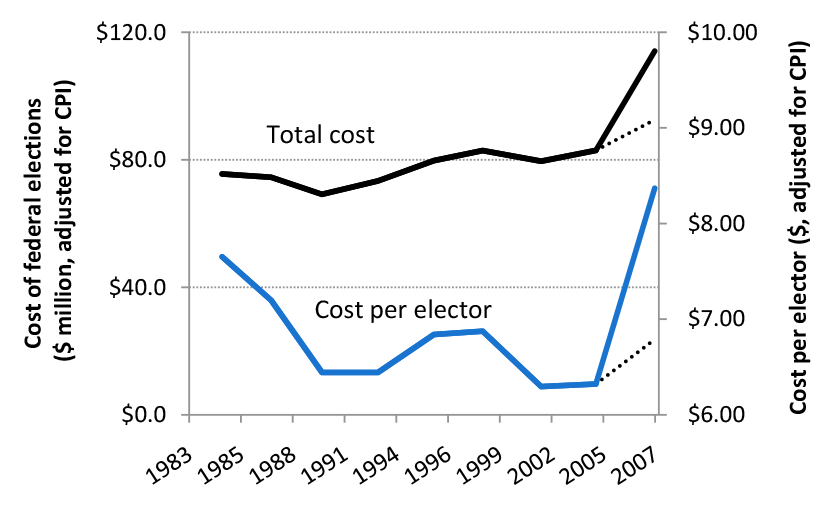

4. The AEC is dependent on annual Budget appropriations for the majority of its funding, including for the delivery of elections. The AEC's Budget appropriations rise in years when there are general elections or referendums, and fall in non-election years. The AEC has estimated the total cost of preparing for and conducting the 2007 general election at $114 million.

Audit objectives and scope

5. During the preparation of the ANAO's Planned Audit Work Program 2006–07, JSCEM suggested that the ANAO consider a possible performance audit into the efficiency and effectiveness of the AEC's management of elections. JSCEM's suggestion was considered in the planning and preparation for this performance audit, which focuses primarily on the AEC's administration of the CEA in the lead-up to and conduct of the 2007 general election. In this way, the audit complements JSCEM's June 2009 report on the 2007 general election, which dealt principally with matters of legislative policy. The audit objectives were to assess the effectiveness of:

- the measures taken by the AEC to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll, particularly during the period prior to the announcement of the 2007 general election; and

- the AEC's planning and preparation for and conduct of the 2007 general election.

6. The scope of the audit work undertaken included an examination of the AEC's preparation of the electoral roll; it also reports on the AEC's progress in implementing relevant recommendations of previous ANAO audits, in 2001 and 2004, of the integrity of the electoral roll. The planning and execution and outcomes of the AEC's data-matching, visits to electors and enrolment advertising were examined, especially over the two years prior to polling day. The audit also examined the AEC's inspection and selection of suitable polling booths, the appointment of temporary staff for polling day, the flow of voters through polling booths and the accuracy of the election-night counting of votes in selected electoral divisions.

Overall conclusion

7. Transparent, timely federal elections conducted with integrity are central to an effective electoral system. Each federal election is a complex logistical event, and the 24 November 2007 general election was the largest to date. Out of an estimated 14.8 million eligible electors, 13.6 million were enrolled to vote, 13.3 million turned out to vote and 12.9 million votes were counted. Accordingly, 87.5 per cent of the eligible population cast a vote that counted in the final result but 12.5 per cent did not.3

8. The challenges faced by the AEC in conducting elections are increased by the uncertain timing and the short period of time between an election being called and polling day (41 days for the 2007 election). These circumstances make more difficult the tasks of mobilising some 70 746 temporary staff in 2007, operating 7723 polling booths, conducting mobile polling at over 200 remote locations and collecting votes at 104 overseas posts.

9. The counting of ballot papers started after the close of polls, and the AEC published progressive tallies on the internet and in the National Tally Room. Before polling day ended, enough House of Representatives ballot papers had been counted for political leaders to announce that the responsibility for the executive government of the Commonwealth would change.

10. Such is the confidence in the AEC's processes and count that a new ministry was sworn in and a change of governing party effected on 3 December 2007, nine days after the election. This was before the AEC had completed its final count of the 12.9 million votes admitted to the count and well before it had officially declared the election results, which occurred between 14 and 21 December 2007 as the results for each state and territory were finalised.4

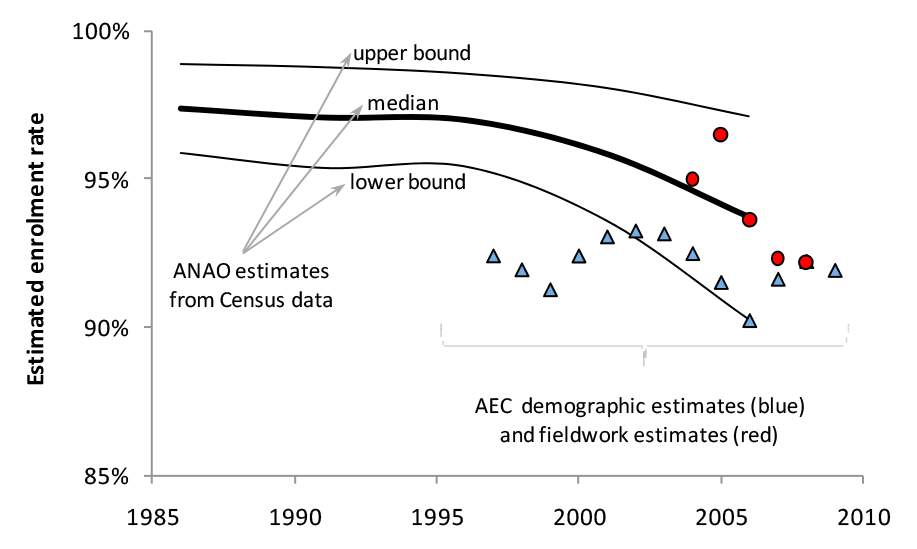

11. The most significant long-term issue facing the AEC remains the state of the electoral roll. Notwithstanding the significant effort made by the AEC to recover and improve the enrolment rate prior to the 2007 federal election, on polling day the enrolment rate was well below the target of 95 per cent of the estimated eligible population. As a result, an estimated 1.1 million eligible electors were missing from the rolls on polling day.

12. After the election, the enrolment rate has deteriorated. By December 2009 it was estimated that just under 1.4 million eligible electors were not enrolled to vote. As illustrated by Figure S 1, the AEC's existing approaches to improving enrolment rates have become less effective (as well as becoming more costly). In addition, the number of enrolment forms being processed by the AEC has been falling since 2001–02 and, for 2008–09, and was at the lowest level since 1996–97. A continuation in this decline would further reduce the completeness of the electoral roll at future federal elections.

Figure S 1 Enrolment as a percentage of the estimated eligible population, 1986–2009

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS Census data and AEC enrolment data.

13. Improving the enrolment rate is one of the greatest challenges facing the AEC. Accordingly, four of the nine audit recommendations are suggestions for improving the accuracy and completeness of the electoral roll through:

- improvements to roll maintenance and a review of funding arrangements;

- re-examining the privacy arrangements for roll information and roll products, together with the AEC assessing the extent to which the broad use of electoral-roll information by non-government entities may be impacting on the willingness of Australians to enrol to vote;

- expanding and enhancing the methodology for undertaking habitation visits as part of the roll-management activities; and

- a program of research into the key demographic characteristics of those that have not enrolled to vote, and the reasons for this, so as to enable better informed and more focused efforts to improve the enrolment rate.

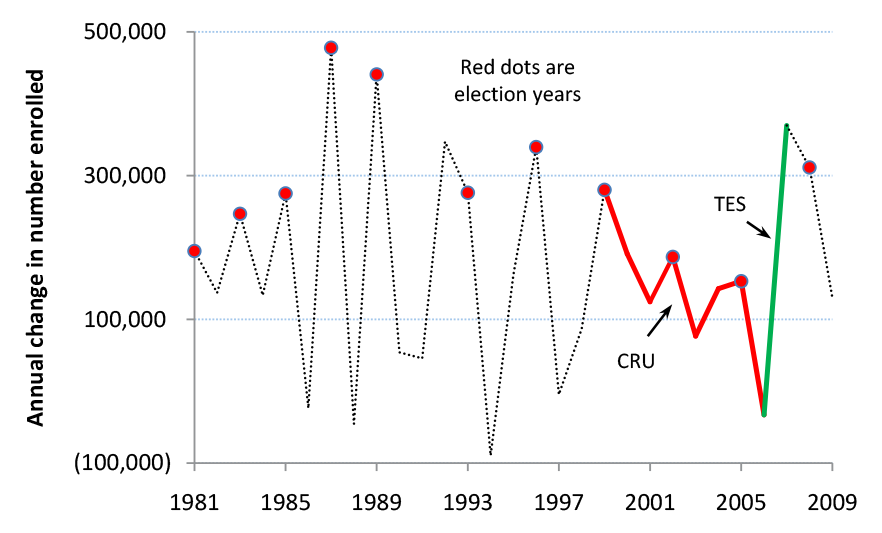

14. The AEC's planning and preparation for the 2007 federal election was effective, but there is evidence that elements of the existing approaches may be reaching their limit in terms of cost-effectiveness. A significant proportion of persons on the electoral roll did not vote. Some polling booths were less than optimal, making voting more onerous for electors and officials alike; and the AEC experienced difficulties in recruiting and training polling-booth staff to a suitable standard. Accordingly:

- two recommendations encourage a more strategic approach to election workforce planning with a particular focuson the selection, recruitment, training and performance evaluation of polling staff; and

- a further recommendation suggests various ways to improve the suitability and accessibility of polling booths.

15. In addition, while the AEC's processes supported the fair and accurate counting of votes, transport and security arrangements for ballot papers completed by electors could be improved and the process by which election-night results are communicated from polling booths would benefit from being made more secure. The AEC also does not report upon its performance in undertaking the 24 key election activities it has identified. Accordingly, the final two recommendations seek to:

- address risks to the integrity of the electoral process from the relatively insecure means currently used for reporting of election-night counts by Officers-in-Charge of polling booths, as well as the transport of completed ballot papers; and

- encourage more transparent and accountable performance reporting by the AEC on its conduct of elections.

16. In addition to the audit recommendations, there are a number of places where this report identifies dated administrative provisions within the CEA that would benefit from review at the next opportunity.5 Consistent with its functions under the CEA, there would be benefit in the AEC providing advice to government on options for improving the administrative provisions of the CEA.

Key findings by chapter

Enrolment and roll management (Chapter 2)

17. Compulsory enrolment and compulsory voting are two of the pillars of Australian democracy. In this respect, the electoral roll provided for under the CEA is the key to voter entitlement at the federal, state, territory and local-government levels.

18. The AEC has in place a centralised roll-management system (RMANS) that is used, amongst other things, to generate the roll that is available for public inspection and the certified lists of electors used at polling booths on polling day. Another key computer system is the AEC's Election Management System (ELMS).

19. The staged redevelopment of the AEC's election-management and electoral-roll systems (ELMS and RMANS) has been underway since mid-2004. However, the project has not proceeded as planned, with the AEC:

- informing the ANAO that the cost estimate had risen from the original $27 million to ‘somewhere between $56 million and $60 million';

- estimating that the redevelopment would be completed by December 2014 if it was to proceed, 42 months after the originally planned completion date of June 2011; and

- in October 2009, placing on hold any further development of the next stages of the systems-redevelopment project until it has a more comprehensive understanding of the implications of the JSCEM report on the 2007 federal election, the Government's second Green Paper on electoral reform6 and this ANAO performance audit.

20. More broadly, the AEC has created a Business Investment Committee and informed the ANAO that it has established a more robust project-management process.

Funding arrangements

21. To provide the electoral roll, the AEC draws on four sources of funding: ordinary annual appropriations, a special appropriation under the CEA, income from Joint Roll Arrangements (JRAs) with the states and territories, and capital appropriations.

22. The JRAs provide a significant source of funding to the AEC. The underlying assumption of the JRAs is that the costs of maintaining the electoral roll should be shared between the AEC and its joint roll partners. However, a robust costing model has not been implemented and there are significant variations between the states and territories as to their rate of contribution per elector.

23. In addition to the funding received through JRAs, the bulk of the funding for maintaining the roll is provided by a combination of ordinary annual and special appropriations. The Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) has informed the ANAO that the same funding outcome for the AEC could be achieved by providing all of the AEC's appropriations for roll management through the annual appropriation Acts.

Privacy

24. The roll is a public document and is available for public inspection which enables participants to verify the openness and accountability of the electoral process and object to the enrolment of any elector. In this context, the question of what personal information should or may be recorded on the electoral roll and included in related products is important to the AEC, as this directly affects the conduct of elections as well as the production of various roll products.

25. Current arrangements are such that electors' details, collected and processed by the AEC, are regularly made available to a wide range of entities. The value of such information, marrying electors' common-law and verifiable identities,7 is illustrated by the wide range of users and uses to which it can be put. An appropriate counterbalance is a coherent framework to ensure that the privacy of individuals is maintained and that improper use is discouraged. However:

- a broad range of data is collected from a variety of sources, including electors, some of it without a clearly evident purpose under the CEA;

- ownership of roll information can be unclear, for instance, when collected and/or provided under the JRAs; and

- the proper uses of the data by third parties are not clearly defined, with the result that the prohibitions on the unlawful disclosure of roll information are difficult to codify and enforce, minimising any intended deterrent effect of the significant penalties that could apply.

Roll review and update (Chapter 3)

26. Maintaining an accurate, complete and trustworthy electoral roll is fundamental to the AEC's administration of electors' entitlement to vote. The AEC's stated target is to ensure that at least 95 per cent of people eligible to vote are on the electoral roll. To measure its performance, the AEC compares recorded enrolments to estimates of the eligible population derived from Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) population statistics.

Roll integrity

27. The AEC conducts Sample Audit Fieldwork (SAF), an annual review of a statistically valid sample of Australian addresses, derived using a methodology provided to the AEC by the ABS. The SAF data, collected in accordance with the approach advised by the ABS, provides statistically sound demographic information on potential electors and an opportunity to estimate the number of resident non-citizens to the level of reliability determined by the sample size. There would be benefits in the AEC expanding and enhancing the sampling methodology for undertaking habitation visits so as to:

- attain more reliable estimates at the state and territory level; and

- assist it to identify the key demographic characteristics of missing electors and resident non-citizens.

Roll completeness

28. Since 1999, the AEC has managed the electoral roll by a process of data-matching referred to as Continuous Roll Update (CRU).8 Where CRU data-matching suggests that an elector has become eligible or has changed their address, a CRU mail-out or field visit can result in enrolment. Otherwise, non-response can lead to the removal of the elector from the roll. Over time, the unit costs of each CRU enrolment have risen by some nine per cent annually and, notwithstanding the addition of new data sources to CRU, the initial success rates of mail-outs and fieldwork have declined. By mid-2005, the AEC was consistently removing more people from the roll than were enrolling or re-enrolling.

29. By late 2006, the AEC was aware that the fall in enrolment after the 2004 general election had been more pronounced than anticipated. Responding to the marked decline in enrolment during 2005–06, the AEC reviewed its CRU operations. Combined with the usual impetus of an impending general election, the AEC made a considerable effort to increase the enrolment rate, with $36 million spent on:

- a large-scale Targeted Enrolment Stimulation (TES) program involving extensive mailing to electors' addresses, supplemented by fieldwork visits and telephone contact;9 and

- an integrated communications strategy including extensive media advertising.

30. The outcome of the communication strategy and TES activities was more complete electoral rolls (see Figure S 2). However, while the enrolment rate rose from 90.2 per cent at June 2006 to 92.3 per cent of eligible electors by polling day on 24 November 2007,10 it remained well below the 95 per cent target. Accordingly, notwithstanding the extra effort and expense, an estimated 1.1 million eligible electors remained missing from the rolls on polling day 2007.

Figure S 2 Annual change in number of eligible electors enrolled, 1981–2009

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC data. The red lines correspond to the period when Continuous Roll Update (CRU) was in operation, the green line to the 2006–07 financial year, during which the bulk of the AEC's Targeted Enrolment Stimulation (TES) activity occurred. The 2007 general election is shown in the data for the 2007–08 financial year.

31. ANAO analysis is that TES activities were the more cost-effective and efficient component of the AEC's 2007 pre-election enrolment activities. However, there was a lower rate of return (in relation to the unit cost per enrolment transaction) on the extra expenditure incurred in 2007 compared to that undertaken prior to the 2004 election.11 In respect of these matters, the AEC:

- informed the ANAO that it faced a far greater challenge in 2007, as there were only three days in which new electors could enrol or nine days in which they could update their existing enrolment details before the close of rolls. The AEC therefore could not rely on the approach taken in 2004 and previous elections, when electors had a full seven days to finalise their enrolment before the close of rolls and most AEC advertising took place after the election was called; and

- has recognised that the strategy of roll stimulation through large-scale advertising funded by the AEC is not sustainable and that it is unable to rely on a peak of enrolment activity in the lead-up to an election announcement to boost enrolment participation.

32. In addition, ANAO analysis is that, while it was an effective and timely innovation for the 2007 election, TES has its limitations, most notably that of self-selection. Specifically, because it relies on data-matching the details of previously identified electors or potential electors, the TES approach is inherently biased toward tracking people who have had prior contact with the AEC. It is less effective at identifying either those who have never enrolled, or those whose personal details have no currency in the electronic data held by the entities with which the AEC conducts its data-matching. In this context, ANAO analysis of available data indicates that a program of research into elector enrolments and enrolment trends would assist the AEC to identify potential electors missing from the roll and the reasons why they may not be enrolling (so as to focus efforts at increasing the number of eligible electors who are enrolled).

Election planning and preparation (Chapter 4)

33. The AEC's 2007 election planning and management aimed to bring together in a timely fashion the staff, polling facilities and polling materials necessary to conduct the election at short notice. As it has no control over the setting of the dates of federal elections and may be called upon to deliver an election in a matter of weeks, the AEC entered into contracts well in advance of the election to print ballot papers and certified lists of electors, produce cardboard polling equipment and transport polling materials across Australia and overseas.

34. The AEC's total operating costs for the 2007 general election were estimated to be some $114 million, $38 million (or 50 per cent) higher than the $76 million cost of the 2004 general election. A significant proportion of the increased costs related to the enrolment-stimulation activities undertaken during 2007.

35. Figure S 3 shows the AEC's operational election expenses in price-adjusted terms. If allowance is made for the additional advertising expenses and the cost of electronic-voting trials (the dotted lines in Figure S 3), the cost of the last seven general elections has been between $6 and $7 per elector, in price-adjusted terms, indicating that the AEC's core election costs have remained fairly stable over that time, while total election costs have slowly grown (in price-adjusted terms) as the number of enrolled electors has grown. The available data also indicate that the AEC has contained costs and achieved efficiencies over the period, partly by containing growth in the number of polling booths as well as by allowing only modest increases in payments to polling staff.

Figure S 3 Cost of administering federal elections 1984–2007, adjusted for movements in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Source: ANAO analysis of AEC Annual Reports and price data from the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Staffing

36. Staffing costs are the largest single component of the election budget, and the costs of polling-booth staff are the majority of overall election staffing costs. One clear strength of the AEC's approach to election staffing is that it has in place sound methods and systems for estimating the likely number of electors who will cast votes at ordinary polling booths. For the immediate future, these votes are likely to remain the overwhelming majority of votes cast on polling day and, applying its current staffing model, the AEC is well-placed to estimate the likely number of polling-booth staff required for a general election. However, other aspects of the AEC's approach to staffing are not as well-developed.

37. Obtaining sufficient suitable staff was one of the main challenges facing Divisional Returning Officers (and the AEC as a whole) in the lead-up to the 2007 federal election. For example, in the last week before polling day, the AEC was still to recruit, appoint and train more than 10 per cent of the final number of polling officials, including 280 Officers-in-Charge of polling booths.12 This meant that a significant number of polling officials were appointed with little time in which they could be trained and for the AEC to be confident that they were competent in the exercise of their assigned duties. The AEC's ability to assess the extent and impact of these issues has been impeded by shortcomings in its implementation of the performance-rating process for polling staff. Against this background, there would be benefit in the AEC:

- undertaking comprehensive research to better understand the nature of its election workforce and develop strategies to better manage recruitment and retention;

- establishing systems to identify former and potential senior polling staff with previous extensive electoral experience, and commencing the engagement process for key staff earlier in the electoral cycle for the purposes of better assessing their competencies and providing sufficient training; and

- improving the implementation of the performance-rating process for polling staff which, among other things, can be used to inform the recruitment processes for future electoral events as well as to identify areas in which employment practices might be improved.

Premises

38. On Saturday 24 November 2007, more than 10 million Australians cast their vote by going to one of 7723 ordinary polling booths, often a school or community hall.

39. Divisional Returning Officers select, inspect and abolish polling booths, with guidance and final approval from the AEC's national and state offices. In general, for the 2007 federal election the AEC sought the same venues for hire as were used in the 2004 election. The exceptions were generally new polling booths created since the previous election, old polling booths that were no longer available, and old polling booths that were closed either because of declining voter numbers or because they were deemed by the AEC to be unsuitable and could be replaced by an alternative venue.

40. At the divisional level, the AEC gathers data on the physical state of polling booths. The AEC's inspection regime and the polling-booth profiles completed by OICs provide a de facto standard for polling booths. However, not all polling booths were inspected by the AEC prior to the 2007 election, notwithstanding that the AEC has reported that inspections of all polling booths had been conducted.13 The AEC received some complaints and, whilst few in number in comparison to the number of polling booths provided, the complaints did identify shortcomings with some polling booths (as well as raising doubts about whether the AEC is able to rely upon advice from third parties about the suitability of the venue without AEC staff inspecting the venue themselves).

41. In the context of the short time-frame between the election being called and polling day, the existing approach of placing the major responsibility for securing polling booths with Divisional Returning Officers provides the AEC with little bargaining power in relation to the rents charged by venues. One result was that the rents paid for polling booths varied widely, an outcome that may persist without a more strategic approach to finding and renting polling premises.

42. In these circumstances, it is noteworthy that there are presently no arrangements in place for the AEC to use premises owned by the Commonwealth for the purposes of an election, and the AEC presently has only one agreement in place at the national level or at the state level to assist it with access to venues—in particular public schools—for election purposes, or to other premises owned by state or local governments.14 In addition to seeking to negotiate such agreements, there would be benefit in the AEC working with:

- the Commonwealth agencies that provide education funding to state and territory governments (including, in some instances, funding for the construction or upgrade of school facilities) to secure better access to those facilities as polling booths; and

- the Commonwealth agencies that provide funding for the construction, upgrade and/or maintenance of community facilities that may be suitable for future use as a polling booth, or are already used as a polling booth, so as to secure improved facilities for the conduct of electoral events.15

Polling day (Chapter 5)

43. For the 2007 election, the AEC provided 7723 static polling booths, 429 pre-poll or early voting centres, and 104 overseas polling booths. The AEC also provided 37 remote mobile-polling teams, 25 prison mobile-polling teams and 444 special-hospital teams for eligible voters. In addition, electronic-voting trials were conducted for blind and sight-impaired electors and for Australian Defence Force personnel serving outside Australia.16

44. In relation to the 24 divisions examined in detail by the ANAO as part of the audit, no problems were recorded or evident for 52 of the 186 polling booths (28 per cent) subject to detailed audit examination. For this proportion, the venue and its facilities were adequate to the task, all polling material and cardboard arrived on time and was able to be set up on the night before polling, polling commenced on time and the flow of voters was steady, without any excessive delay.

45. However, at other polling booths a range of problems of varying degree were encountered. The problems encountered at these 134 polling booths (72 per cent of those subject to detailed examination) can be characterised in general terms as:

- problems in obtaining timely access to premises to set up and commence polling;

- difficulties arising from less than suitable premises for polling;

- queuing by voters during the day; and

- administrative difficulties, including delays in receiving election material.

The count

46. The election-night count of votes in polling booths is of central importance to the democratic process in Australia. It is relied on to such an extent that a change of government can be effected within days of the election on the basis of the very high credence afforded to it (as well as other information such as a concession of defeat on the part of incumbents). ANAO analysis of the count in a sample of five divisions showed that there was a low rate of counting errors. However, the AEC's practice of overwriting election-night counts with the results of the fresh scrutiny prevents the AEC from easily measuring and benchmarking the accuracy of the first counts of votes for all polling booths.

47. One area of the election-night count that would benefit from enhanced controls relates to the reporting from polling booths. On election night, polling-booth staff, once they have counted the votes, are required to telephone the results through to the divisional office. There they are entered into the ELMS system, which transmits them to the Virtual Tally Room and the National Tally Room. There are three measures in place to ensure the authenticity of the results being received in divisional offices. These are: the use of dedicated lines/unlisted numbers; a system control on the range of results; and the caller's statement that he/she is calling from a named polling booth. However:

- there is no electronic or other formal system of caller verification; and

- since most divisional offices will have at most three or four computers able to access ELMS, not all of the staff will be able to enter data directly into the computer system while speaking to polling-booth staff. Therefore some staff will enter results directly, while others receive telephone calls and write down the results for data entry when possible.

Scrutiny

48. All votes counted on election night must be subjected to fresh scrutiny (counted again). Declaration votes, including absent, provisional, postal and pre-poll votes, are first subjected to preliminary scrutiny (to determine their admissibility) and are later counted and then re-counted.17 These processes can take two weeks or more to finalise, as the CEA requires that declaration votes be admitted to preliminary scrutiny up to and including the 13th day after polling day. The criteria for declaring the poll as set out in the CEA18 are such that the ever-increasing volume of declaration votes also increases the likelihood that Divisional Returning Officers will require more time for fresh-scrutiny counting in order to declare the poll.

49. The usual impact of the process of challenge and attrition during the fresh scrutiny is an increase in the total number of informal ballot papers and a corresponding decrease in the total number of formal ballot papers. In a very close count, such as that for the division of McEwen in the 2007 general election, the final result can turn upon the outcome of the scrutiny, as recorded in the Court of Disputed Returns judgment of that case. That judgment was considered in a subsequent review of the AEC's practices. The AEC informed the ANAO that it had accepted the recommendations made in that review, which included:

-

the incorporation in AEC manuals of the Court of Disputed Returns guidance on formality in the McEwen case—Mitchell v Bailey (No. 2);

-

a single comprehensive set of information on formality for decision-makers, with scrutineers receiving, as near as is possible, identical information and advice to that given to polling officials;

-

the close involvement of AEC senior management in the monitoring of close counts and in the decision-making in the case of potential re-counts; and

-

a policy of re-counting all ballot papers in divisions where the margin of votes is less than 100.

Physical security

50. Assessments of the physical security of the election process were conducted by an external agency prior to both the 2004 and 2007 elections. In 2007, the physical-security assessment for the general election focused in particular on the transport of ballot papers from polling booths to divisional offices and the security of the phone-in of election results (in this latter respect, see paragraph 47).

51. The AEC's conduct of the fresh scrutiny, which results in the final tally and declaration of results for both Houses of Parliament, is reliant on the complete return of all ballot papers and declaration votes. Completed ballot papers may be collected and transported to the Divisional Returning Officer by a transport contractor or, more commonly, in the motor vehicle of the Officer-in-Charge of the polling booth. Given the importance of these documents, there would be benefits in the AEC identifying and assessing options that better manage the risks, including those relating to the physical security of the ballot papers.

Performance reporting

52. The AEC has reported that, after the election, it collected and analysed qualitative and quantitative data from all divisional offices on 24 key election activities. However, the AEC has not published the results of this work. By way of comparison, the Electoral Commission of the United Kingdom in March 2009 set out seven performance standards for electoral returning officers in Great Britain and, in October 2009, published the initial performance findings in relation to the conduct of the 4 June 2009 elections, with a full analysis published in January 2010.

AEC response

The AEC welcomes the ANAO's audit and the report's acknowledgements of the robust policies and procedures that the AEC has in place to enable it to deliver transparent, timely and trusted federal elections. In particular, the AEC welcomes the acknowledgements of the extraordinary and complex logistics required to enable the franchise for some 15 million eligible voters.

The audit report focuses on the preparation for and conduct of the 2007 federal election but it reflects both established practices that have successfully delivered nine federal elections since the inception of the AEC in 1984 and the evolution of those practices to meet the shifting expectations of the community in respect of future federal election events.

The report recommends a range of actions that support or strengthen policies in place prior to the 2007 federal election. A number of the recommendations go to the heart of the AEC's commitment to maintaining a comprehensive and accurate electoral roll that enables eligible voters to exercise their franchise while ensuring the appropriate use of the information collected for the compilation of the roll.

The report also encourages a more systematic approach to the significant challenges of coordinating the recruitment and training of polling-place officials. On polling day alone, this involves the deployment of more than 70 000 people to more than 7700 polling places, but it also involves the provision of trained staff to manage a range of other critical polling facilities, including pre-poll centres and postal voting. In preparation for the next federal election, the AEC has extensively revamped its recruitment and training processes.

The AEC's performance in the planning and conduct of federal elections is subject to parliamentary scrutiny via the work of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, and the AEC believes that the development of comprehensive performance standards will enable it to continue to provide detailed support to the Committee's inquiries.

The AEC therefore supports these and other recommendations in this report.

Footnotes

1 From 1983–87, the Joint Select Committee on Electoral Reform undertook the role now performed by the JSCEM.

2 The minimum period between the issue of writs for an election and polling day is prescribed in the CEA. From the date of the issue of writs for an election, ten days must be allowed in which candidates may nominate (CEA sections 156 and 175) and polling must occur between 23 and 31 days after the close of nominations (CEA section 157).

3 The AEC estimates the eligible population using ABS census data and its own enrolment data. On polling day, the estimated eligible population was 14 783 394, compared to 13 645 073 electors enrolled, indicating that there were 1 138 321 potential electors missing from the roll on polling day. Detailed figures are in Table 5.1 of the report.

4 All results were declared by the AEC between 14 and 21 December 2007. This was well within the statutory deadline for the return of the writs for the election on 4 February 2008, 110 days after the writs were issued on 17 October 2007, as provided for by CEA section 159.

5 See paragraphs 2.7, 2.8, 2.16, 2.50, 4.41, 5.18, 5.22, 5.38 and 5.51 of the report.

6 Australian Government, Electoral Reform Green Paper: Strengthening Australia's Democracy, Canberra, September 2009.

7 Verifiable identity refers to documents set out in legislation (such as in the Electoral and Referendum Regulations 1940).

8 Under CRU, the personal information on electors held by the AEC is matched with external data, usually obtained from other Commonwealth, state or territory agencies, from Australia Post and from some utility companies. The prior approach—habitation reviews—had been found to be inefficient to the extent that up to 60 per cent of fieldwork visits resulted in no changes to the roll, although they did confirm enrolment at those addresses.

9 The design of the TES program adopted certain findings of the AEC's 2007 CRU review. These included more sophisticated data-mining and data-matching to identify populations of potential new electors or re-enrolling electors for targeted mailing and fieldwork visits.

10 This compared favourably to an enrolment rate of 91.5 per cent on polling day on 9 October 2004.

11 Including the costs of TES for 2007, the AEC spent $36 million on enrolment activities, promotion and advertising prior to the 2007 election, compared to a little over $10 million prior to the 2004 election.

12 Similarly, 1194 polling staff were appointed on polling day, and another 920 were appointed the day before.

13 AEC, Annual Report 2007–08, p. 146.

14 The sole existing agreement at the time of this audit was with the NSW Department of Education and Training.

15 In this respect, there have been examples where funding agreements have included provisions requiring the funding recipient to make the facility that is being funded with an Australian Government grant available for wider community use. This indicates that it would be possible for the AEC to also be guaranteed access to use the facility (subject to reasonable notice and appropriate fee arrangements) as a polling place.

16 The AEC's evaluations of the trials were considered by the JSCEM, which concluded in March 2009 that, for cost reasons, the trials should not be continued at future elections.

17 Section 4 of the CEA defines a declaration vote as a postal vote, a pre-poll vote, an absent vote or a provisional vote. Preliminary scrutiny involves checking the details of electors (for instance, that they are correctly enrolled) to ensure that they are eligible to lodge their declaration vote. At present, the actual votes are not counted until after polling.

18 Section 284 of the CEA provides, in effect, that election results may be declared on the basis of the two-candidate-preferred count where the two candidates with the highest number of first-preference votes could not be displaced from those positions after the receipt of any declaration votes that may have been delayed.