Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Australian Defence Force's Mechanisms for Learning from Operational Activities

The objective of the audit is to assess the effectiveness of the ADF’s mechanisms for learning from its military operations and exercises. In particular, the audit focused on the systems and processes the ADF uses for identifying and acting on lessons, and for evaluating performance. The ANAO also examined the manner in which information on lessons is shared within the ADF, with other relevant government agencies, and with international organisations. Reporting to Parliament was also considered.

Summary

Introduction

1. In recent years the Government has directed the ADF to conduct a wide range of operations, often in conjunction with other countries. These have included missions involving large numbers of personnel and equipment deployed to dangerous locations such as Afghanistan; long-term peacekeeping missions involving a smaller number of personnel to enforce peace undertakings; and shorter-term efforts to supervise elections in other countries or provide humanitarian and disaster relief.

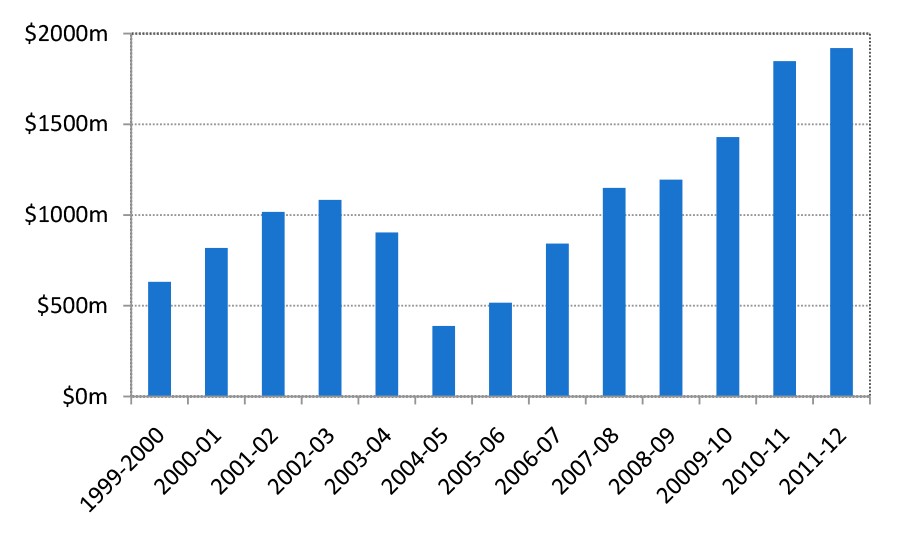

2. Since the 1999 deployment to East Timor, the ADF has been called upon to operate in more theatres and fill more operational roles than at any time since its formation in 1975. Since 1999, the ADF has conducted 117 operational, humanitarian and disaster relief operations, 15 of which are ongoing.[1] Net additional expenditure on major ADF operations has been increasing since 2005–06, and is projected to be as much as $1.9 billion in 2011–12, as shown in Figure S 1.[2] In 2008–09, the ADF was engaged in 18 operations around the world deploying as many as 3500 personnel, with up to 12 000 ADF members in the operational deployment cycle, either preparing, on deployment, or reconstituting following return from deployment.[3]

3. The ADF’s involvement in international operations has fostered international cooperation and assisted the development of inter-Service coordination.[4] Most ADF operations are now ‘joint’, employing elements from two or more Services under one Commander to achieve results that a single Service might not. Currently, ADF operations are planned, mounted, conducted and controlled by Headquarters Joint Operations Command (HQJOC), under the command of the Chief of Joint Operations (CJOPS).[5]

Figure S.1: Net additional expenditure on major ADF operations, 1999–2000 to 2011–12

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence data. Figures for 2010–11 and 2011–12 are Defence estimates.

4. The effectiveness of deployed ADF forces depends, in part, upon the ADF’s ability to learn from experience to improve its operational performance. The ADF considers lessons and evaluation to be important activities supporting the pursuit and maintenance of a ‘knowledge edge’:[6]

Defence needs to be a learning organisation that is adaptable to ensure that it can rapidly identify and investigate issues and disseminate solutions to maintain a knowledge edge to compensate for its small size.[7]

5. A learning organiation uses experience to change its behaviour, deal effectively with change and complexity, and improve its capabilities.[8] From Defence’s perspective:

A learning organisation has systems, mechanisms and processes in place that are used to continuously enhance its capabilities, and those who work with or for it, to achieve sustainable objectives for themselves and the organisation.[9]

6. In the ADF’s view, maintaining a knowledge edge requires it to rapidly identify, analyse and incorporate into practice lessons learnt in the planning, preparation and conduct of operations. It is a significant challenge, particularly when operational tempo is high and the operational environment is complex:

The Knowledge Edge … is not a static and stable phenomenon which can be readily achieved or even understood, but rather one that is dynamic, volatile and elusive in nature.[10]

Defence’s approach to learning from operations and exercises

7. Defence’s two principal mechanisms for learning from operations and exercises are:

- observational lessons that arise from individual tasks and actions (for example changing procedures in response to observations of current enemy tactics or the observations of allied soldiers); and

- evaluations of military operational and exercise performance against objectives (for example assessment of the progress of individual operations against their stated objectives and targets).

8. The ADF’s structures for learning from operations and exercises operate mainly at the Service level and, more recently, within HQJOC. At one end of the learning spectrum, lessons may arise through observation and action at any point in time. The term ‘lessons’ is widely used by the ADF and other military organisations to convey the idea of achieving an improvement in practice by observing activities, noticing a pattern of action or behaviour that detracts from optimum performance, devising and applying a remedy, and then incorporating the remedy into standard practice.[11]

9. At the other end of the learning spectrum, military organisations learn by evaluating their operational performance, through the planned, intentional assessment of the degree to which aims and objectives of operations are met, measured against pre-determined criteria. There can be a degree of overlap in these learning processes, such as when the evaluation of operations leads to the identification of lessons relating to the conduct of operations, including at the tactical level.

10. To date, the ADF’s focus on learning lessons, in common with many other armed forces, has primarily been on the tactical level, at which military activities and tasks are conducted. At the tactical level, lessons can be put straight into practice to protect lives and improve the effectiveness of day-to-day operational tasks, and the ADF’s established ‘lessons learnt’ model reflects this tactical focus. The model comprises the four steps of collecting lessons, analysing them to identify appropriate action, getting approval for a particular course of action, then putting lessons into action.[12] At the time of this audit, Defence had in place a mandated ADF-wide system for recording lessons—the ADF Activity and Analysis Database System (ADFAADS)—as well as separate systems within Army and, more recently, HQJOC.

11. In respect of evaluation, the ADF’s mechanisms for evaluating its operational performance derive, in large part, from the long-standing practice of Commanders’ reporting through Post Operational Reports (PORs—for operations) and Post Activity Reports (PARs—for exercises). In 2003 the ADF sought to enhance its operational evaluation through the development of pre-determined, standardised Australian Joint Essential Tasks (ASJETs), a common set of building-block tasks and activities from which operations and exercises can be planned and evaluated. The ASJETs were introduced to provide the opportunity for greater consistency in planning and evaluation, with the intention of reducing the reliance on the more subjective approach of ‘professional military judgement’.

12. Complementing and building on the introduction of ASJETs, in 2007 the ADF published its inaugural operational evaluation methodology. Operational Evaluation is one of Defence’s key doctrines and is a guide to learning from ADF operations. It sets out Defence’s broad approach to turning observations and known information into improvements to capability and preparedness, and to improved planning and conduct of operations. Notwithstanding that the title of this doctrine refers only to operational evaluation, in fact it encompasses both a ‘lessons learnt’ process (for the kinds of observational lessons referred to in paragraphs 8 and 10), and the methodology for evaluations of military operational and exercise performance against aims and objectives. The ADF’s Operational Evaluation doctrine is well-suited to deriving lessons learnt from the performance of tasks and evaluation of the ADF’s performance against military objectives.

13. More recently, the ADF and other armed forces have turned greater attention to evaluating the effects and impact of operations at the higher level of impacts and outcomes, under what is called the ‘effects-based approach’. The effects-based approach has been trialled by the armed forces of the United States and is in its initial stages of exploration by the ADF. The focus of the approach is on the achievement of ADF outcomes, something that is more difficult to evaluate than lower level, task-based performance.

14. The effects-based approach is consistent with the United Nations’ 2008 Peacekeeping Operations Principles and Guidelines (referred to as the ‘Capstone Doctrine’), which codifies the largely unwritten body of knowledge arising from the 60 or more United Nations peacekeeping operations undertaken since 1948.[13]

Parliamentary scrutiny

15. In August 2008, the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (the Committee) reported on its inquiry into Australia’s involvement in peacekeeping operations. The Committee, recognising that it was difficult to assess the long-term impact of operations on the host population, nonetheless came to the view that Australia should measure the effect of its operational involvement against objective indicators.[14] The origins of this audit are in the Committee’s request to the Auditor-General to:

consider conducting a performance audit on the mechanisms that the ADF has in place for capturing lessons from current and recent peacekeeping operations including:

- the adequacy of its performance indicators;

- whether lessons to be learnt from its evaluation processes are documented and inform the development or refinement of ADF’s doctrine and practices; and

- how these lessons are shared with other relevant agencies engaged in peacekeeping operations and incorporated into the whole-of-government decision making process.[15]

16. In initial audit discussions, Defence informed ANAO that processes employed by the ADF for learning apply equally to peacekeeping operations as to any other ADF operation or training exercise—that is, there is not a specific learning process employed by the ADF for peacekeeping operations.

17. Appreciating the importance of the subject matter and the challenges of evaluating and learning lessons from military operations, the Committee’s request was considered in the context of an audit covering all ADF operational deployments and military exercises.

Audit objectives and scope

18. The objective of the audit is to assess the effectiveness of the ADF’s mechanisms for learning from its military operations and exercises. In particular, the audit focused on the systems and processes the ADF uses for identifying and acting on lessons, and for evaluating performance. The ANAO also examined the manner in which information on lessons is shared within the ADF, with other relevant government agencies, and with international organisations. Reporting to Parliament was also considered.

Overall conclusion

19. The capacity to learn from military operations is an essential requirement for the ADF if it is to achieve a ‘knowledge edge’ to compensate for its size. Lessons learnt from observation and experience can protect lives and improve operational effectiveness. In addition, operational evaluations highlight progress in meeting objectives, informing necessary changes to operations, and providing a degree of accountability for the personnel and materiel resources committed to operations.

20. Defence has structures in place to learn from operations and exercises, and in recent years there have been attempts to improve these as Defence has recognised their importance. However, the application of the ADF’s learning framework is patchy and fragmented. Army pays significant attention to collecting, recording and acting on immediate and short-term lessons. This is not the case for the Navy or the Air Force, neither of which presently captures immediate or short-term lessons. The processes for capturing and acting on lessons from joint operations have been improved within HQJOC and are now better aligned with operational tempo.

21. The key ADF-wide information system provided in 1999 to support lessons and evaluations (ADFAADS) has fallen into disuse. Army was not a heavy user of ADFAADS and has developed its own lessons systems. ADFAADS has been effectively supplanted by fragmented, Service-specific arrangements and there is now no up-to-date central repository for lessons and operational evaluations that can be used by staff that plan operations. At the time of this audit, HQJOC was considering how it might best coordinate existing Service-level lessons agencies in order to assist in the planning and evaluation of operations and exercises.

22. The conduct of in-depth and detailed evaluations of operations has only recently commenced within HQJOC, with limited coverage up until 2009. The ADF’s Operational Evaluation doctrine is well thought-out, but has yet to receive widespread application to operations and major exercises. To date, Defence’s overall approach to learning has placed more emphasis on observational lessons than on operational evaluation.

23. The lesser priority previously given to evaluation was evident during the ADF’s re-alignment of its operational evaluation functions during the formation of HQJOC in 2008. There was a poor transfer of existing knowledge and experience, key functions were overlooked, some important improvements to lessons and evaluation processes stalled, and there was a hiatus in ADF operational evaluations lasting some twelve months.

24. Up until 2009, there had been discrete evaluations of aspects of five out of 117 operations, and of seven major exercises: none assessed progress toward operational outcomes. This greatly restricts the opportunities to measure the performance of the ADF in action and has limited the ADF’s capacity to assess its performance against the objectives set by the Government when it committed the ADF to action. The limited coverage and scope of operational evaluations is likely to continue until the ADF affords it greater priority and assigns resources for evaluation of operations, commensurate with their scale and importance.

25. A recent, more promising development is the ADF’s exploration of the internationally recognised ‘effects-based approach’ to evaluating operations. Aspects of this approach are being trialled in ADF assessments of three ongoing campaigns (East Timor, Afghanistan and the Solomon Islands). The effects-based approach affords greater opportunity for evaluating outcomes, for integrating evaluation with other Australian Government agencies, such as the Australian Federal Police (AFP), and for informing the Parliament and the public of the long-term impacts of operations. At the time of this audit, effects-based approach assessments have focused on the achievement of Defence goals, and did not yet engage the efforts of other government agencies or extend to measuring progress toward government strategic outcomes.

26. Briefings to Parliament on operations by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) are supported by well-established senior committee structures, involving the Service Chiefs and other senior military officers. Defence could improve its reporting to Parliament via its operational Key Performance Indicators by ensuring that these are well-supported by operational evaluations and other relevant data from the ADF’s lessons processes.

27. In view of the fragmented approach that has applied to practices for capturing the experience of operational activities, and the interest in identifying and reporting progress toward operational outcomes, there is a need to consolidate and reinforce the importance of capturing this experience and contribute to the ADF gaining a ‘knowledge edge’. ANAO has made five recommendations to consolidate and improve the focus of the ADF’s mechanisms for lessons and operational evaluation, including where other Australian Government agencies are involved in operations, and in reporting outcomes to Parliament.

Key findings

Learning lessons from observation and experience

28. Many areas of the ADF have made significant changes in recent years in order to improve the way they learn lessons from operations and exercises. Of the Services, Army has the most developed lessons systems, encompassing immediate and short-term lessons from operations, supported by dedicated databases and intranet portals. Army’s lessons systems provide a useful response to the immediate needs of personnel deployed on operations and exercises. By contrast, systems for identifying and recording immediate and short-term lessons are not as well-developed in Navy and Air Force.

29. In response to identified deficiencies in its processes for recording and learning from lessons and evaluations, in 2007 Defence established a Knowledge Management Roadmap and other high level initiatives. However, there was subsequently a lack of progress due, in part, to the partial re-allocation in 2009 of key responsibilities for evaluation to the newly-formed HQJOC. As a result, some key roles and responsibilities were overlooked and adequate staffing was not provided for all evaluation and lessons functions to continue to operate. Since the time of audit fieldwork, Defence has established a new central forum, with representation from different parts of Defence and the Services, to consider and progress joint lessons initiatives (see Appendix 1).

30. The ADF currently has a fragmented approach to capturing, recording and acting on lessons. Coordination and information-sharing between Services is rudimentary and the effectiveness of the current approaches has yet to be assessed by the ADF. It is also not yet clear how joint tactical lessons are to be identified and shared, and HQJOC is still developing an approach to assessing exercises and involving Service-level lessons agencies in its planning for operations. In this respect, the UK Defence Lessons Identified Management System (DLIMS) is an information technology solution that may provide a model for sharing lessons between the Services and with HQJOC.

Recording lessons and evaluations

31. In 1998, the ADF developed and subsequently mandated the use of ADFAADS to provide a source for the ADF to access knowledge gained from past operations and exercises. However, limitations in the design, accessibility and resources allocated to ADFAADS have resulted in declining use of the system since 2006. These factors have detracted from ADFAADS’ usefulness as a tool for monitoring and evaluating the issues raised and lessons learnt from operations, and prevented the analysis of trends.

32. A re-invigorated effort to coordinate and manage the ADF’s operational knowledge is a key pre-requisite for learning from operations and lessons. Given that ADFAADS is no longer being used in the manner or extent intended, attention needs to be given to developing a succession plan for a replacement system including:

- establishing the scope of lessons and/or evaluations (including international and inter-agency lessons and evaluations) to be recorded;

- ranking the relative importance of the issues to be recorded, allowing for the escalation of matters of lasting significance and the rapid processing of lessons;

- ensuring effective links to other systems and other solutions already being adopted by the Services and JOC;

- planning for the capture and migration of relevant ADFAADS data;

- ensuring a high level of useability, to encourage and support its adoption; and

- designing to allow comprehensive search and data-mining to support operational planning and analysis, especially of trends across more than one operation.

33. A hallmark feature of the arrangements put in place by the ADF’s international counterparts is the move toward consolidated systems for collecting and storing lessons and evaluations of operations.[16]

Evaluating operations

34. Thus far, the ADF’s approach to evaluating and learning from operations and exercises, while supported by a useful and flexible methodology in the form of the ADF’s 2007 Operational Evaluation doctrine, has tended to focus on lessons and has made limited progress toward evaluating performance. The doctrine, which provides guidance for its practical application and sets out the responsibilities and the activities involved, provides a clear and flexible guide for the ADF to learn lessons and assess performance. It is well-developed and can be applied at the tactical, operational and strategic levels, and can target different types of operational activities.

35. The doctrine could be improved by including guidance on establishing a hierarchy of analysis. This could extend to placing the highest priority on assessing operations, which would then take precedence over the evaluation of collective training, exercises and other ADF activities. Such an approach would make more effective use of the ADF’s slender evaluation resources. In practice, the use of the doctrine would benefit from the systematic application of predetermined conditions, standards and measures, which the ADF has previously developed under the Australian Joint Essential Tasks (ASJETs) framework.[17] To date, there is little evidence that ASJETs have been fully utilised.

36. While the doctrine and supporting ASJETs are in place, Defence has yet to apply a consistent, systematic ADF-wide approach to undertaking evaluations of operations. No Service has a dedicated mechanism for assessing the performance of its force elements deployed on operations. There has been a lack of consistency in the structures and processes adopted in each of the Services and, at the joint level, limited resourcing, so that staff for operational evaluation are in short supply, resulting in limited coverage of operations to date.

37. The fragmented approach to operational evaluation was exacerbated during the formation of HQJOC, at which time the transfer of knowledge to successor organisations was poorly managed by Defence, and led to the ADF’s operational evaluation functions being greatly diminished for at least a year.[18] Overall, the slender resources currently made available for evaluations are very likely to continue to restrict evaluation activities to a small proportion of ADF operations and exercises.

HQJOC evaluations

38. HQJOC has recently begun to conduct an outcomes-focused approach to operational evaluation that it calls ‘campaign assessments’. The goal is to measure, through subjective and objective means, progress toward Defence-sought outcomes for a campaign, typically an operation sustained over an extended period. Campaign assessments are a markedly improved approach to assessing operations compared to past ADF approaches:

- Campaign assessments are developed based on the Defence-level outputs and outcomes sought, focusing at a higher level than past operational evaluations that tested various operational inputs.

- They incorporate more robust measures of performance and effectiveness, offering a more structured approach to informing decision-makers and allowing for better comparison over time.

39. Like other recent initiatives across the Services, the campaign assessment process is still in its infancy, and Defence is still learning to adapt its approach, based on its experience. To date, assessment has focused on the achievement of Defence goals, and does not yet extend to including the impact of the efforts of other government agencies. The campaign assessment process has similarities to the approach being developed by the AFP, which has adopted an outcome-based approach to evaluating progress and determining success, and seeks to involve additional stakeholders in the evaluation process.

Sharing operational experience with other agencies

40. The ADF’s development of campaign assessments, and exploration of the outcomes-focused effects-based approach to campaign assessment, offers the ADF a framework for working with other entities to assess whole-of-government operational outcomes. ADF operations are planned and conducted within the whole-of-government national crisis management machinery. Defence is invariably involved in responding to crises with national security dimensions, which frequently involve other government and non-government agencies. The ANAO considers that where deployments comprise both the ADF and the AFP, there would be merit in the agencies working together to undertake assessment, based on an agreed framework, of the whole-of-government outcomes, involving other agencies such as AusAID where appropriate.

41. The ADF’s performance in sharing lessons in relation to operational activities within its own organisation is mixed, and its processes for sharing relevant operational lessons with other agencies are not yet regular or systematic. In this regard, the recently established Asia Pacific Civil-Military Centre of Excellence (the Centre) has the potential to provide a forum for identifying potential whole-of-government lessons, as well as assisting in the development of a whole-of-government approach to performance measurement. The Centre has not been established for sufficient time for the ANAO to assess its effectiveness.

Reporting to Parliament

42. Defence has in place structures and processes to ensure that CDF is well placed to provide Parliament with up to date information on the conduct and progress of ADF operations. The principal structures supporting CDF’s role are the Strategic Command Group (SCG) and the Chiefs of Service Committee (COSC). The SCG is a forum for discussion of operations, and COSC provides military advice to assist CDF in discharging his responsibilities in commanding the Defence Force and as principal military adviser to the Government.

43. In addition, Defence’s Annual Report provides information on ADF operational performance. The reported operational Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) provide an overview of the performance of Defence operational activities at the outputs level, though the information provided is general in nature and offers little insight into the conduct of operations and exercises and their impact. Defence’s operational KPIs would benefit from better-specified measures of success, including information on how success was gauged, and be better informed by a structured process that draws upon well formed evaluations.

Agency responses

44. Defence’s response to the report is reproduced below:

Defence appreciates the audit undertaken by the ANAO and advised that progress has been made in developing the lessons and evaluation framework, but does acknowledge that there is scope for improving the way that Defence learns from operations and exercises. There is more work to be done in putting in place consistent methods for identifying, analysing, implementing and validating lessons, and importantly, ensuring that relevant lessons can be effectively shared across the Services. The five recommendations proposed by the ANAO have all been agreed by Defence, and reflect initiatives already being pursued.

The findings of the audit are being used by Defence to further progress improvements in the joint and single service lessons areas, noting there have been significant changes in the management structures and coordination for lessons in the 16 months since the ANAO audit commenced. In particular, implementation of a new governance framework for lessons has led to progress consistent with the ANAO recommendations. Joint Capability Coordination Division now coordinates Joint Lessons and Evaluation across Defence, and employs the Joint Capability Coordination Committee and the Joint Lessons and Evaluation Working Group to drive and facilitate interaction between individual Service lesson agencies. It identifies lessons that are relevant beyond an individual Service, and focuses on delivering capability development requirements for joint lessons and evaluation.

While Defence is not the lead agency for measuring Whole-of-Government performance and progress towards government objectives, it participates in many inter-departmental fora and will work with other agencies to develop a structured approach to measuring Whole-of-Government performance. As identified in the report, Defence must evaluate how well campaign and operation objectives are being met, and Headquarters Joint Operations Command is well progressed in developing Campaign Assessment processes.

Defence is committed to continuously improving both its learning framework, and the evaluation of operational performance.

45. The AFP’s summary response to the report is reproduced below. Their full response is at Appendix 2 of the report.

The AFP welcomes the ANAO audit report on the Australian Defence Force’s Mechanisms for Learning from Operational Activities. The AFP notes there are no specific recommendations for the AFP.

Footnotes

[1] Defence advice to ANAO, June 2011.

[2] Defence operations are funded on a 'no win, no loss' basis, where Defence is supplemented for all operational costs incurred but must return any surplus operational funding.

[3] See Defence Annual Report 2008–09, p. 2, and Department of Defence, Defence: The Official Magazine, Issue 4, 2008–09, p. 12, <www.defence.gov.au/defencemagazine/editions/200809_04/DEFMAG_080904.pdf> [accessed 4 June 2010]. Defence informed ANAO in June 2011 that the number of personnel in the operational deployment cycle during 2009–10 was of the same order as those for 2008–09.

[4] As well as joint operations, ADF operations include single-Service events and combined operations involving the forces of at least one other country, including training exercises to test and validate capability. Operational involvement may extend to other Australian Government agencies. Defence estimates that since 1999 they have conducted approximately 1300 exercises, excluding single-Service exercises.

[5] HQJOC was created in 2004, replacing the Headquarters Australian Theatre, and the separate position of CJOPS was created in 2007 after previously being the responsibility of the Vice Chief of the Defence Force.

[6] Australia's Strategic Policy, Defence 1997, Department of Defence, Canberra.

[7] Chief of the Defence Force, ADDP 7.0: Doctrine and Training, Australian Defence Doctrine Publication, January 2006.

[8] See Senge, P, The Fifth Discipline, 1990, Random House Australia; ‘Peter Senge and the learning organization’, <http://www.infed.org/thinkers/senge.htm> [accessed 18 April 2011]; Malhorta, Y, ‘Organizational Learning and Learning Organizations: An Overview’, <http://www.brint.com/papers/orglrng.htm> [accessed 20 April 2011]; Mitleton-Kelly, E, ‘What are the Characteristics of a Learning Organization?’, <http://www.gemi.org/metricsnavigator/eag/What%20are%20the%20Characteristics%20of%20a%20Learning%20Organization.pdf> [accessed 20 April 2011].

[9] Chief of the Defence Force, op. cit.

[10] Burke, M, Information Superiority, Network Centric Warfare and the Knowledge Edge, DSTO-TR-0997, Defence Science and Technology Organisation, 2000, p. 7.

[11] The Australian Army’s abstract definition of lessons is provided in the Glossary to this report.

[12] The ‘Australian Defence Organisation Lessons Learned Process’ (collect, analyse, decide, implement).

[13] United Nations, Peacekeeping Operations Principles and Guidelines, New York, 2008, p. 8.

[14] Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Australia’s involvement in peacekeeping operations, Canberra, August 2008, pp. 333-339. A previous inquiry conducted by the Committee into Australia’s public diplomacy raised similar issues. The report noted that the focus of the Department of Foreign Affairs was measuring at an activity level rather than on the immediate or long term effects of diplomacy. The Committee recognised that evaluating the effectiveness of public diplomacy is difficult, however it needed to be done, and a range of indicators needed to be established to monitor and assess effectiveness (with surveys measuring attitudes and changes in perceptions one method). See Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Australia’s public diplomacy: building our image, Canberra, August 2007, pp. 170-182.

[15] ibid., p. 339.

[16] The UK Defence Lessons Identified Management System (DLIMS) was developed to become a Defence-wide lessons application, however discrete domains can be established within it that have their own management procedures and access controls, enabling privacy within the overall DLIMS construct.

[17] The ASJETs are held on a Lotus Notes database accessed through ADFAADS, which has not been well maintained (see Chapter 3 for detailed discussion of ADFAADS).

[18] Defence informed ANAO that the departure dates of the four ADFWC staff were staggered over the last year of ADFWC’s operation, although this draw down did impact on the deployment of operational evaluation teams.