Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The ATO's Administration of Debt Collection-Micro-business

The objective of the audit is to assess the effectiveness of the ATO's administration of debt collection. Micro-business debt is a particular focus of attention. The three key areas examined are:

- strategies–especially the ATO's initiatives trialled in 2006;

- infrastructure–the IT systems, people, policy and processes and risk management framework supporting the collection of debt; and

- management and governance–planning, monitoring and reporting mechanisms and liaison with stakeholders.

The ANAO focused on the work of the campaigns area within the Debt Line, which has collection responsibility for 90 per cent of collectable debt cases and responsibility for other key, centralised functions such as reporting, quality assurance review, consistency and best practice, and the debt collection initiatives.

Summary

Background and context (Chapter 1)

Dimensions of tax debt

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is the Australian Government's principal revenue collection agency, collecting net tax of $232.6 billion in 2005–06. In the same period, the ATO received an appropriation of $2.459 billion for departmental outputs and as at 30 June 2006, it employed 21 511 staff.

Under the self assessment system of taxation in Australia, taxpayers are expected to lodge correct tax returns and statements by the due date, and to pay their taxation liabilities as and when they fall due for payment. A taxation debt arises when a liability falls due for payment and it remains unpaid. Debt collection is a category of compliance action undertaken by the ATO.

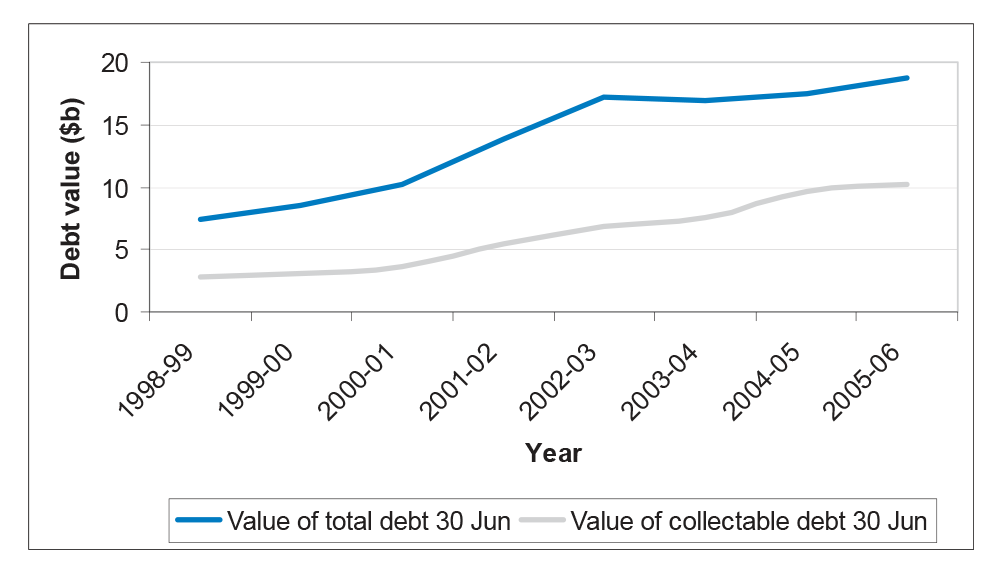

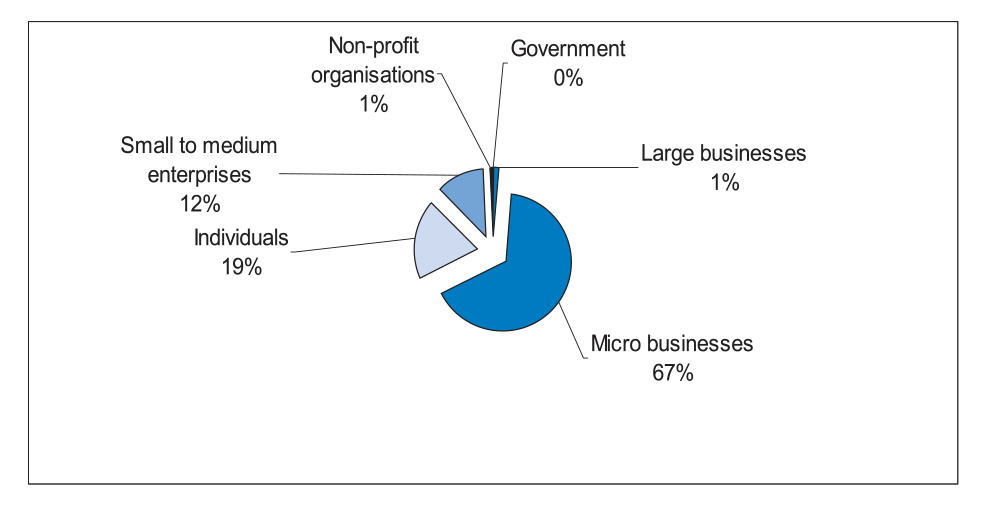

Taxation debt is a significant and growing problem in Australia and micro-business1 debt is a particular compliance management problem for the ATO. As at 30 June 2006, total taxation debt was approximately $18.78 billion, of which over half, approximately $10.23 billion, is debt that the ATO classifies as ‘collectable' (that is, the debt is due and is not impeded as a result of dispute or the entity being insolvent). Collectable debt as a percentage of revenue collections has risen over the course of the last 10 years, and particularly following the implementation of A New Tax System in 2000–01. Collectable debt as a percentage of revenue collections was 2.7 per cent in 1995–96, 3.7 per cent in 2002–03 with the implementation and bedding down of A New Tax System and 4.4 per cent in 2005–06. Micro-businesses account for more than two-thirds of the value of all collectable debt. As at 30 June 2006 micro-business collectable debt totalled $6.8 billion.

The ATO's direct expenditures on debt collection processes have risen substantially over time, from $80 million in 2001–02 to $138 million in 2005–06.2 The number of full time equivalent staff engaged in the debt process rose from 1 574 to 2 246, over the same period.

Figure 1 illustrates the steadily increasing value of collectable debt over time.

Figure 1 Trends in total debt and collectable debt

Source: ATO, Commissioner of Taxation Annual Reports, various years

Figure 2, which depicts collectable debt by market segment, shows the particular significance of micro-business debt within the larger context of total collectable debt, representing the segment with the largest share of collectable debt outstanding and accounting for approximately 67 per cent of the total value of debt outstanding at 30 June 2006.

Figure 2 Collectable debt by market segment - percentage value at 30 June 2006

Source: ATO

The ATO's position in collecting debt

The ATO's position as a tax debt collector differs from that of commercial organisations collecting customers' debts on goods and services purchased. The ATO's particular position affects the ATO's strategy and operations regarding debt collection.

Unlike private sector creditors, the ATO cannot withhold supply on the basis of poor credit risk or payment history. The ATO must continue to engage taxpayers even if they have a poor tax payment history, knowing that these taxpayers will continue to be active in the tax system and will be required to lodge returns and statements and meet future payment obligations.

Because the ATO does not have the ability to predetermine a credit rating system for individual businesses or more broadly, industry sectors, that will incur tax liabilities, its debt exposure is potentially more susceptible to underlying economic conditions than commercial organisations. Private sector creditors are able to balance the ‘risk versus reward' equation or to take security over a debt in the event of economic downturn or individual misfortune.

In undertaking its tax debt collection activities, the ATO must necessarily balance the objectives of revenue collection, compliance and community interests. Community compliance underpins the integrity and sustainability of the tax system. This means that ATO debt collection activities must not only be effective in collecting debt, they must also be perceived by taxpayers to be effective and equitable, in order to maintain community confidence and the sustainability of the system.

Audit objective

The objective of the audit is to assess the effectiveness of the ATO's administration of debt collection. Micro-business debt is a particular focus of attention. The three key areas examined are:

- strategies–especially the ATO's initiatives trialled in 2006;

- infrastructure–the IT systems, people, policy and processes and risk management framework supporting the collection of debt; and

- management and governance–planning, monitoring and reporting mechanisms and liaison with stakeholders. The ANAO focused on the work of the campaigns area within the Debt Line, which has collection responsibility for 90 per cent of collectable debt cases and responsibility for other key, centralised functions such as reporting, quality assurance review, consistency and best practice, and the debt collection initiatives.

ANAO conclusion

The tax debt problem in Australia is significant, and growing. As mentioned in paragraph 3, total taxation debt at 30 June 2006 was $18.78 billion, of which approximately $10.23 billion is debt that the ATO classifies as ‘collectable'. Indicative of the trend over the medium term, there has been a 186 per cent increase in the value of collectable debt and a 116 per cent increase in case numbers between 30 June 2001 and 30 June 2006. Although tax debt trends have been influenced by the introduction and maturing of A New Tax System, as one point of comparison, total debt of the corporate and household sectors increased by 63.3 per cent over the same period.3 ATO collectable tax debt as a percentage of revenue collections has increased from 3.74 per cent in 2002–03 to 4.4 per cent in 2005–06.

The effective administration of tax debt is important due to its impact on Australian Government revenue, for equity reasons and for community confidence in the tax system.

The administration of debt collection is a substantial and challenging task for the ATO. It is substantial for the large volumes of transactions and the flow of new debt cases that the ATO must process and with regard to the debt on hand, the large number of cases and their significant values. It is challenging for its dynamic social and commercial context and its quite intractable nature, given human behaviour. The ATO's administrative task is also challenging in that effective administration requires the ATO to recognise individual debtor circumstances and both immediate and wider compliance impacts.

The ATO's experience is that the nature of the debt collection administrative task requires continual change and innovation to stimulate positive changes in taxpayers' payment compliance. Key elements of good debt collection administrative practice are education; early intervention; resolute debt collection action involving agreement on a suitable repayment scheme or, if necessary, firmer collection measures recognising individual circumstances and wider compliance impacts; understanding the cost of collection; and understanding the effect of treatments.

There will always be a level of debt that will be uneconomical to pursue. Good debt administrative practice, based on a sound understanding of the cost of collection, means that such debts should be removed from the pool of cases that are the subject of active collection attention, until changed circumstances mean that collection action could become viable again.

The administrative task requires the ATO to understand the debt context and have a cohesive strategy to deal with the debt issue. It also requires effective treatments, relevant administrative tools in IT systems, as well as people and processes to monitor and respond to debts on an ongoing basis as required. The ATO's administration is well-supported in relation to some of these elements, and innovations via the initiatives in 2006 are promising, but the ATO's capacity for effective administration can be improved in certain key areas.

Whilst the ATO continues to improve its strategies and processes, tax debt, and particularly micro–business tax debt, is still a significant financial drain on the community that distorts business competitiveness. Further improvements are required to strategy, administrative processes and supporting systems and governance processes relating to performance assessment. ATO debt administration would be enhanced by the ATO having continuing regard to using facilitative, incentive and punitive measures to secure payment compliance.

Although Australia enjoys a relatively good position in terms of some OECD debt benchmarks, the ATO has only recently been able to slow the rate of growth in collectable debt in Australia; collectable debt is still rising, albeit at a slower rate. Collectable debt represented 3.74 per cent of revenue collections in 2002–03, 3.79 per cent in 2003–04, 4.47 per cent in 2004–05 and 4.40 per cent of revenue collections in 2005–06 as noted above.

The ATO advises that its ability to manage cases efficiently and effectively and to undertake beneficial analytical work is constrained due to current systems limitations, although the ATO plans to address these issues as part of the Change Program. Aspects of debt management and governance also require improvement, most specifically planning, monitoring and reporting at the operational level.

The ANAO recognises the positive steps the ATO has taken or that it plans for administering debt collection, in terms of innovation in its strategy, its infrastructure and governance frameworks. However the size and continued growth of collectable debt, despite substantial increases in ATO resource allocations, and the absence of some key tools necessary for effective administration inhibit the ATO's administration of debt collection.

Moreover the unique circumstances pertaining to the nature of tax debt and it susceptibility to general economic conditions suggest that the traditional approaches and most recent initiatives undertaken by the ATO may not necessarily reduce the aggregate amount of collectable tax debt going forward.

The May 2007 Budget announced that the Government will provide the ATO with additional funding of $125 million over four years from 2007–08 to improve the administration of debt collection.

Debt collection, particularly in relation to micro-business debt, requires continued, focussed attention by the ATO, to secure payment compliance, maintain community confidence and promote the sustainability of the tax system. However the ANAO considers that to reduce the level of collectable tax debt over the long term, it may be necessary for the ATO to expand its debtor research and analysis and, if necessary, to use its findings to provide further advice to government for targeted changes to the administrative design of the tax system.

ATO strategies (Chapter 2)

The ATO has debt collection objectives and strategies

The ATO's debt collection objectives are to optimise debt collections, maintain taxpayer compliance and maintain the overall integrity of the tax system.

The ATO's debt collection task is affected directly and indirectly by the design features and compliance measures of the tax system. The Debt Line has a key responsibility with regard to tax debt collection and other parts of the ATO have complementary roles in streamlining tax administration and encouraging and enforcing compliance.

The ATO's overall debt collection operational strategy is to deal with specific areas of perceived risk, such as large debt and debt associated with tax schemes, with specialised resources. It seeks to deal with the remainder using collective resources deployed via campaigns, including early intervention strategies, to address large pockets of debt and to target debt early when it is most likely to be recoverable.

The ATO's strategies and approaches were informed by its analysis in the late 1990s of international best practice in debt collection.4 However the ATO needed to largely re-define its strategies and re-adapt its approaches in 2000, especially in relation to micro-business debt, given the changes to the structure of the tax system.

The ATO's approaches have changed

The ATO's approaches to debt collection (organisationally and procedurally) have changed over time. At the time of the ANAO's previous audit on ATO debt collection,5 debt was managed in the various lines dealing with particular types of taxpayers or types of taxes. The implicit administrative notion was that particular types of tax debts required specialised treatments. The ATO now has a more centralised approach to tax debt collection in that one line, the Debt Line, is primarily responsible for tax debt collection. The implicit administrative notion is to apply appropriate approaches to debt collection across debt types.

The tax design elements of A New Tax System6 in mid 2000, among other things, broadened the indirect tax base, thereby increasing significantly the number of business entities making tax payments, compared to the previous tax regime. The new tax system and the ATO's strategy to phase in compliance management associated with the changes, caused the ATO to moderate elements of its debt collection strategies. Over time, the ATO's general compliance posture emphasising education and assistance for taxpayers at the introduction of A New Tax System changed to one of encouraging compliance. The ATO's changed (firmer) debt collection posture was demonstrated in measures such as the Small Business Debt Assistance Initiative in mid 2004. This initiative involved the ATO offering concessional payment arrangements in certain circumstances provided the debtors agreed to make payments of their debt by direct debit of their bank accounts in favour of the ATO and also maintained current obligations. The ATO took firmer action on taxpayers who did not respond, or who defaulted on their payment agreement.

The administrative load of the Small Business Debt Assistance Initiative and the unexpected, significant growth in collectable debt in 2004–05 highlighted the need for the ATO to make fundamental changes to its debt collection practices to allow it to work on debt more quickly. Along with organisational responses in the latter part of 2005, the ATO:

- modelled its operational approach on a conceptual framework well-understood in the collection industry, that emphasised early action and differentiated debt treatments7; and

- trialled initiatives in 2006 to test new and innovative ways of contacting and engaging with taxpayers who have a debt with the ATO.

Key initiatives were the referral of some debt cases to a private sector agency to collect, after-hours contact of debtors who had ignored previous ATO attempts to engage them and dialler technology to streamline processes for staff undertaking phone campaign work and thereby increase productivity via increased case throughput. The results of the trials have been broadly positive, in terms of providing reassurance about processes, community reactions and debt collections. The ATO has advised of its intention to apply these initiatives more comprehensively as part of its suite of debt collection treatments, recognising that the full implementation of these initiatives will present managerial challenges. However, the ATO cannot calculate the cost of each of its debt collection treatments in assessing the overall cost effectiveness of each type of treatment. The wider adoption of the initiatives would be usefully supported by the ATO collecting information to assess the costs of its debt collection treatments and the extent to which debt collection objectives are achieved.

Given the breadth of the ATO's debt collection activity and the evolution of the ATO's approaches to debt collection, including measures more closely reflecting private sector approaches, there is merit in the ATO formulating a cohesive statement of its overriding strategy. This should outline its debt collection objectives, and how its activities and initiatives and evolving directions fit within this overall strategy. Such a statement (with detail appropriate to the internal or external audience) would be of benefit to taxpayers and staff, and could enhance community awareness of, and confidence in, the ATO's administration of debt collection.

The ATO complements its debt collection activities with measures to prevent or pre-empt debt problems. A major focus, particularly for micro-business, has been measures to promote good record keeping and sound cash flow management. The latter issue is mentioned by the ATO and industry, and in the previous audit report on ATO debt collection,8 as a factor related to debt problems for micro-business. The ATO's intended research on debtor issues and behaviours and compliance management measures would usefully support and inform debt prevention and pre-emptive measures. The ATO proposes to undertake research into why businesses fall into, and remain in, debt and to reinvigorate its consideration of incentive and punitive measures to encourage tax debt compliance.

The comprehensive application of the ATO's debt collection strategies operationally requires the ATO to know the cost of its collection treatments, the effect of its treatments and the extent to which the various treatments contribute to ATO debt collection objectives. At this stage, the ATO does not have such an administrative model with these elements. Such a model would be useful to inform debt collection strategies and initiatives, including making administrative decisions about how, and for how long, it should pursue aged debts.

Infrastructure (Chapter 3)

The case management system has severe limitations but improvements are planned via the Change Program

The ATO uses the Receivables Management System to manage overdue debt cases. The case processing functions of this IT system and the system controls are broadly appropriate, but limitations detrimentally affect the efficient and effective administration of debt collection. The system has limitations regarding: easy access to debtor information; providing reports on the time to finalise cases; the age of debt; the value of particular types of debt; and the effect of the ATO's particular debt treatments on a debtor's case.

The ATO has advised that changes to be introduced as part of the ATO's Change Program will provide a firm foundation to address these issues. The Change Program may also enable call technology efficiencies with the application of tools and management processes to facilitate the conduct of targeted campaigns.

Adequate policy and process support

The ATO supplements high-level policy statements with detailed procedural statements and scripting for case officers dealing with debtors. The Debt Line applies a three tier quality assurance process designed to obtain quality and consistency in administration. One of the key roles of the Line's Debt Collection Best Practice Unit is to obtain consistency of collection practice.

Data matching and tracing of debtors are important aspects of the ATO process

The ATO undertakes data matching using ATO and external sources to establish a debtor's financial position. This provides the context for the ATO in dealing with the taxpayer, including possible debt treatment options such as activating a garnishee or, in some instances, negotiating a payment arrangement.

The ability to trace and contact a debtor is fundamental to the ATO being able to collect a tax debt. As at 30 June 2006, the ATO had over 71 500 micro-business segment collectable debt cases that were untraceable and its debt initiatives highlighted a significant number of cases without a useable phone number. The ATO is seeking to find better ways to maintain current contact details and find alternative means by which to trace debtors, including possibly outsourcing tracing to the private sector. Such ATO debtor tracing activities are worthwhile, and would benefit from liaison with other Commonwealth agencies, such as the Child Support Agency and Centrelink. The Child Support Agency, for instance, considers that it has good quality location data on its clients, all of whom should be ATO clients. Subject to ensuring proper data matching procedural requirements are met, including those relating to privacy issues, the Child Support Agency could possibly assist the ATO by providing contact details for clients of mutual interest.

ATO debt administration would benefit from having a clearer basis for non-pursuit of aged debts

The age profile of much of the ATO's micro-business segment collectable debt presents significant challenges for the ATO, because the older the debt, the more difficult it is to collect. Approximately 43 per cent of the value of micro-business segment activity statement and income tax collectable debt is greater than one year old and approximately 26 per cent is greater than two years old (the latter being called ‘aged debt').

The ATO's efforts to assess and manage its aged debt require an understanding of the costs of debt collection treatments to be able to determine the point at which costs would exceed the return to the ATO. The ATO does not yet have this information. The ATO's debt collection administration would be improved by it having a comprehensive non-pursuit decision model that recognises the cost of treatments, and the opportunity cost of continuing collection action on a debt that has limited chance of being collected. In establishing such a model, the ATO would need to make judgements having regard to the need to treat all taxpayers equitably (compliant taxpayers and tax debtors) while recognising individual circumstances, and regard to community perceptions as to the ATO's compliance stance.

People and staff processes are broadly appropriate

The ANAO found that external perceptions of the professionalism and ability of debt collection staff are generally positive and the mix of staff training is appropriate. Staff productivity is an important issue for the ATO to meet its debt collection performance objectives given its resources (for example diminished resources in 2006–07 compared to the previous year). The ATO is implementing strategies to improve productivity with the dialler call technology to expedite call connection processes.

Risk management approach and quality review processes are appropriate

The ATO has appropriate risk management processes, with a regular certificate of evidence review process to provide the ATO with assurance on the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of key controls in relation to systems operations and access, management and fraud controls.

Quality case handling is considered to be an administrative priority in the Debt Line, but this priority has implications for front-line productivity. The dialler technology permits a somewhat more streamlined approach to the processes supporting quality case handling compared to established case procedures. In deciding on the possible wider adoption of dialler technology, the ATO will have the opportunity to consider how the costs and benefits of the dialler case handling approach compare with current processes which have a relative emphasis on more detailed procedural requirements.

Management and governance (Chapter 4)

Corporate planning frameworks are well developed but debt operational plans require formalisation

Debt matters feature in the very high level ATO internal plans, but transparency and public awareness would be enhanced by the ATO making its planned debt collection aims and activities known publicly. There is also scope, as a basis to assess activity against the plan, to include performance targets in the ATO's internal plans referring to debt collection.

The Debt Line does not have an operational plan for 2005–06, but at the time of audit fieldwork was in the process of drafting one for 2006–07. An effective operational plan would reflect higher level strategic priorities and risks and could set out planned activities, including relationships with other relevant parts of the ATO.

The Debt Line has a robust approach to planning at the project level as evident in the documentation and review processes for its discrete innovation projects.

Review measures need development

The ATO has an appropriate range of debt monitoring mechanisms across the hierarchy of the ATO and within the Debt Line. However, the operation of these mechanisms is compromised by the lack of relevant, target-driven performance measures, based on reliable data on debt cases, duration of cases (ie case processing time) and cost of treatments.

The ATO's main performance measures are the movement in collectable debt balances over time and the movement in the ratio of collectable debt to total collections. These are highly aggregated measures and historically the ATO has not set a target for these measures. In 2006, the ATO set a measurable target in relation to the movement of collectable debt balances. The goal was to slow the growth of collectable debt in 2005–06, stop the growth in debt in 2006–07 and then reduce the level of debt. The ATO achieved its goal in 2005–06, with growth of 27.7 per cent in 2004–05 slowing to growth of 6.4 per cent in 2005–06.

The ANAO advanced for ATO consideration a number of possible measures that might improve the ATO's performance monitoring and management capacity. A selection of possible measures is listed at Appendix 5 of the audit report.

The ATO agrees that it needs to expand its current performance indicators and has undertaken to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness measures, with a view to implementing those which can be extracted from the existing case actioning and accounting systems.

The ATO's ability to develop and use additional efficiency and effectiveness review measures to enhance its performance monitoring is constrained by the limitations of its current case actioning and accounting systems. The ATO indicated that it intends to incorporate relevant efficiency and effectiveness measures progressively as systems permit. Data required for some of the ANAO's suggested effectiveness measures, such as that comparing the value of total debt collected to total debt raised, would not be available from existing ATO systems until the changes in the accounting system proposed under Release 3 of the Change Program (after December 2008).

Australia's comparative collectable debt performance is in the upper range compared to other OECD countries

The ATO ranks well compared to overseas tax jurisdictions in terms of collectable debt as a proportion of total collections, ranking fourth out of the 15 countries providing responses on this matter in an OECD survey in 2004.9 This is a positive indicator of ATO performance relative to other revenue agencies' performance.10

Performance reporting could be improved

Reflecting the weaknesses in ATO planning and monitoring of debt collection, the ATO's performance reporting is underdeveloped in key areas. There is considerable scope for the ATO to devise more relevant efficiency and effectiveness measures as its systems capacities improve, and to reflect performance against plan, using relevant performance information in internal and external reporting.

External relationships are productive but could be further developed

The ATO's contact with other Commonwealth agencies with debt collection responsibilities, such as Centrelink, is quite limited in relation to debt collection matters. Further development of relationships with agencies with significant debt collection responsibilities, and from this the sharing of experiences and possible improvements, could assist the ATO. A periodic meeting between relevant government agencies could cost effectively help the ATO to obtain and share knowledge in a variety of fields. These could enhance debt collection processes by improving data sources for debtor tracing, expediting progress in areas such as performance assessment, and fostering insights across government with coordinated research on debtor behaviour and the wider debt context in industry.

The ANAO found that most representatives of industry and professional bodies consulted had had exposure to broad debt collection issues and some had attended briefings by senior ATO executives on the ATO's evolving debt strategy. The ANAO found that the parties' degree of awareness differed, although there was a strong awareness generally of the financial significance of ATO outstanding debts and the challenges these represent for compliance and community confidence in the tax system.

Stakeholders offered suggestions to improve debt collection administration. These include measures to improve mutual understanding between business and the ATO on debt issues via the ATO's small business consultative forums and to improve approaches to debt administration including information measures to help prevent debt as well as measures to facilitate payments. These suggestions echo some of the comments by the debt collection practitioners with industry expertise who the ANAO engaged to review the ATO's debt collection approaches.

The ATO may also be able to make debt collection administrative improvements by drawing on the insights and experience of other business (especially micro-business) credit providers, such as banks. Strengthening the relationships between the ATO and such bodies with focussed consultations, from time to time, could help the ATO to obtain and share knowledge on debt collection practices and challenges.

Future directions

The direction and effectiveness of the ATO's debt collection efforts could be enhanced by the ATO better understanding what causes taxpayers to fall into debt and remain in debt and more broadly to understand debt collection and the debt context from a cross agency perspective. There may be benefit in the ATO extending its planned research on debt behaviours and communication strategies to take a wider view of the nature of, and appropriate government responses to, micro-business debt.

Part of this research could be to appreciate better the relevant contextual issues for the industry and the micro-business in its lifecycle of activity and related debt matters. In the longer term, this research and analysis could provide the ATO with a basis for advising government on targeted changes to the administrative design of the tax system if necessary.

The analytics and risk modelling work that the ATO is starting to undertake offers the ATO the opportunity to obtain a better view of potential risk features of taxpayers, and debtors in particular, and to make efficiency and effectiveness gains. As emphasised in the debt collection industry practitioners' assessments of ATO debt collection practices, such analytics and risk modelling are crucial to the ATO improving debt collection administration.

Despite continued strong growth in Government revenue over time,11 the message of the importance of taxpayers meeting their payment obligations is one that must continue to be advanced by the ATO. Active promotion of this message requires on-going and vigorous attempts by the ATO to reduce significantly collectable debt, particularly in priority areas such as micro-business. This is required, not only because debt represents significant revenue at risk, but because payment compliance is a keystone of an equitable and sustainable tax system. Payment compliance and tax system sustainability both rely on community engagement and support for the tax system.

Recommendations

The ANAO has made six recommendations aimed at improving the ATO's administration of debt collection, particularly for the micro-business segment. While identifying areas requiring remedial attention, these recommendations broadly support the strategic directions and initiatives that the ATO is currently applying.

Summary of the ATO's response

The Tax Office welcomes this review and agrees with the six recommendations and is already making progress to address them.

The report is supportive of the Tax Office's overall directions and will assist in achieving its aim to reduce debt.

Debt collection is a significant and challenging area for all tax administrations. The Tax Office ranks well when compared with other OECD member revenue authorities in regards to debt compliance/collection effectiveness.

While there has been an increase in resources in the debt collection area following the introduction of A New Tax System, the cost of collections has remained relatively stable.

The Tax Office has made considerable improvements in the last eighteen months and achieved a slowing of collectable debt growth in 2005–06. The Tax Office anticipates continued improvement in 2006–07. These results flow from new and innovative approaches that have been put in place including:

- modelling operations on a framework well-understood in the collection industry, that emphasises early action and differentiated treatments; and

- a number of pilot activities such as dialler technology and external referral that is acknowledged in the report.

At the same time, the Tax Office has been investing in the design and review activities necessary to ensure new systems and processes are delivered under the Change Program.

In the May 2007 Budget, the Government announced additional funding of $125.7 million over four years from 2007–08 which will allow the Tax Office to further implement the new approaches on a wider scale. This will ensure that the level of collectable tax debt is manageable over the longer term.

In undertaking its tax debt collection activities, the Tax Office must balance the objectives of revenue collection, optimising voluntary compliance and maintaining community confidence.

As the report correctly acknowledges, the Tax Office's position as a tax debt collector differs from that of commercial organisations collecting customers' debts. Unlike private sector creditors, the Tax Office cannot readily avoid additional liabilities being established on the basis of poor credit risk or payment history.

The Tax Office is committed to supporting taxpayers who want to do the right thing. Notwithstanding this, there are instances where it needs to take firm but fair action, to ensure a level playing field for both businesses and individuals alike.

When contacting taxpayers about their outstanding tax debt, the Tax Office is committed to:

- understanding the taxpayer's situation and individual circumstances;

- being fair and equitable in the application of the law, processes and policy;

- considering each case on its merits and assisting the taxpayer to move on; and

- assisting those taxpayers who are attempting to engage with the Tax Office and do the right thing.

Contacting taxpayers early in the collection cycle enables the taxpayer to better manage the debt before it begins to escalate. This also improves the prospects for the ongoing viability of the taxpayer's business.

The Tax Office is committed to continually improving the administration of the tax system, including its performance in respect of debt collection.

The ATO's full response is reproduced at Appendix 1 of the audit report.

Footnotes

1 The ATO defines micro-businesses as those businesses with an annual turnover of less than $2 million.

2 The ATO's estimated direct expenditure on debt collection processes in 2006–07 is $128.3 million. The May 2007 Budget announced that the Government will provide the ATO with additional funding of $125 million over four years from 2007–08, to enable the ATO to reduce the stock of taxation debt and outstanding superannuation guarantee charge owed by employers. The measures are expected to result in additional revenue of $140 million over four years. See Commonwealth of Australia, Budget Paper No.2 Budget Measures 2007–08. The Commissioner of Taxation's online update of 28 May 2007 Collecting taxpayer debt and outstanding employee superannuation entitlements outlines key areas in which this additional funding will be spent. See Commissioner's online updates <www. ato.gov.au/ corporate/ content viewed 28/05/2007>.

3 See Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian System of National Accounts 2005–06, Feature Article Household Sector Balance Sheet—A National Accounts' Perspective, Cat 5204.0, Table 2: Household Sector Liabilities and Australian System of National Accounts 2005–06, Cat 5204.0 Tables 30 and 38 for corporations' liabilities.

4 These principles suggest that:

- low risk debts are best dealt with by low cost, automated actions;

- medium risk debts are best dealt with by direct personal contact via ATO telephone contact; and

- debts representing a higher risk to the revenue require more direct action by a debt officer, or legal intervention.

5 ANAO Audit Report No.23 1999–2000, The Management of Tax Debt Collection, pp. 35-36.

6 A New Tax System involved, for example, the abolition of sales tax and a range of other taxes and requirement for business registration, the lodgement of activity statements and relevant payments, particularly Goods and Services Tax.

7 The approach, called the ‘V' curve, referring to the V pattern of debt collections over time as collection and then recovery actions are undertaken, is illustrated at Appendix 3.

8 ANAO Audit Report No.23 1999–2000, The Management of Tax Debt Collection, pp. 32 and 89.

9 Report on the Survey of Country Practices in Debt Collection and Overdue Returns Enforcement, Forum on Tax Administration, Centre for Tax Policy and Administration, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) March 2006.

10 However Australia ranks 13th out of 24 countries providing responses in the same OECD 2004 survey, in terms of total gross debt (including disputed debt) as a proportion of net collections. This implies Australia has a much higher incidence of disputed debt, compared to other OECD respondents in the survey.

11 See Budget Paper No 1 2005–06, Statement 13 Historical Australian Government Data, pp. 13-9 for trend information on Government revenues.