Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Test and Evaluation of Major Defence Equipment Acquisitions

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objectives were to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the test and evaluation (T&E) aspects of its major capital equipment acquisition program; and to report on Defence’s progress in implementing T&E recommendations made in the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee’s August 2012 report, Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Defence’s capital equipment acquisition program includes aircraft, maritime vessels and land-based equipment in various stages of engineering development and delivery. In 2013–14 that program consisted of some 180 approved projects with a total value of $79 billion. The 2012 Defence Capability Plan contains an additional 111 projects, or project phases, planned for either First or Second Pass government approval over the four year Forward Estimates period. In 2012, the estimated capital cost of these projects was $153 billion.

2. Each of the above projects rely on test and evaluation (T&E) processes to identify areas of cost, schedule and capability risk to be reduced or eliminated. T&E is a key component of systems engineering and its primary function is to provide feedback to engineers, program managers and capability managers on whether a product or system is achieving its design goals in terms of cost, schedule, function, performance and sustainment. It also enables capability acquisition and sustainment organisations to account for their financial expenditure in terms of the delivery of products or systems that are safe to use, fit for purpose and that meet the requirements approved by government. In July 2001, the then Defence Secretary, Dr Allan Hawke, emphasised the importance of T&E as follows:

T&E is an important tool in our plans for the management of Defence capability to ensure successful achievement and maintenance of operational effectiveness. As Defence moves to consider its governance strategies in a theme of organisational renewal it is timely for us to consider T&E as a key management tool.1

Audit objectives and criteria

3. The audit objectives were to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the T&E aspects of its major capital equipment acquisition program; and to report on Defence’s progress in implementing T&E recommendations made in the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee’s August 2012 report, Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects.

4. To form a conclusion against the objectives, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence’s organisational structures, roles and responsibilities enable the coordinated application of adequate T&E at each stage of the capital equipment project life cycle;

- Defence’s T&E policy and procedures are suitably designed and applied as intended;

- Defence invests in a broad range of training and skills development for T&E personnel to enable the application of necessary T&E expertise throughout the capital equipment project life cycle; and

- the T&E aspects of capital equipment acquisition are transparently reported to inform decision making and management of technical risks that may impact the development and maintenance of the major systems component of the Fundamental Inputs to Capability.

Conclusion

5. Over recent years, Defence has strengthened its enterprise-level management of T&E conducted in support of major capital equipment acquisitions. Defence established a lead authority for T&E (the Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office) to provide advice and consultancy support across Defence, a T&E Principals’ Forum to foster consistency of approach, and has developed an overarching policy on T&E. That said, the conduct of T&E remains distributed across 12 Defence organisations, placing a premium on the effectiveness of Defence’s T&E governance as a means of mitigating the risk of inconsistent conduct of T&E. Defence’s administration of T&E would be further strengthened by introducing arrangements to provide enterprise-level advice to senior responsible leaders on key issues, introducing performance measures and compliance assurance for T&E, and completing reforms to T&E personnel competency and training arrangements. These measures would provide greater assurance over the administration of Defence T&E and would be consistent with reforms underway within Defence, following the recent First Principles Review, to establish a stronger ‘strategic centre.’

6. The case studies examined in this audit highlight the important role played by T&E in managing acquisition risks for major capital equipment. Defence faces challenges in balancing the methodical conduct of T&E for major acquisitions to assure Capability Managers that full contracted capability is delivered, while also seeking to meet delivery schedules and other priorities. In the case of the first Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD), HMAS Canberra, key management decisions were usefully informed by Defence’s T&E, which identified numerous defects and deficiencies for resolution. Defence decided, on balance, to accept HMAS Canberra on the understanding that the deficiencies would be addressed during the ship’s operational phase. In doing so, the Chief of Navy accepted greater risks than would have been the case had System Acceptance been based on more complete objective quality evidence of compliance with contracted specifications, and had Initial Materiel Release been based on less qualified findings by Defence’s regulators concerning compliance with technical, operational and safety management system requirements. As operational T&E is still underway and is not due for completion until the fourth quarter of 2017, it remains to be seen what impact, if any, this elevated risk has on the achievement of Final Operational Capability.

Supporting findings

Key developments in Defence’s test and evaluation management arrangements

7. Defence has 12 organisations that conduct T&E activities. While this approach is beneficial for developing, maintaining and applying specialised T&E expertise, it increases the risk of inconsistent conduct of T&E. This risk places a premium on Defence having effective T&E leadership and governance arrangements.

8. In 2007 Defence established a lead authority for T&E–the Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office–to provide advice and consultancy support on T&E issues and to develop Defence’s overarching policy on T&E. Defence has recently completed and published its overarching T&E policy in the Defence Capability Development Manual (DCDM). This manual expands upon former Defence Instructions concerning Defence T&E policy and completes a longstanding commitment to the Parliament.

9. Defence has more to do to provide a comprehensive and integrated T&E framework to its project offices by ensuring: the DCDM aligns with Navy, Army and Aerospace regulatory management manuals; the DCDM is aligned with new organisational structures arising from the implementation of the First Principles Review2; and that subsidiary T&E policy and procedural guidance manuals used by the various project offices are consistent with the DCDM.

10. Defence’s application of its T&E policy and procedures to the acquisition projects examined in this audit and past performance audits has varied, driven primarily by the relative complexity of Defence projects. Some project offices manage complex developmental T&E with Defence as the prime system integrator, while other offices manage acceptance T&E of mature products that have already undergone acceptance T&E by another jurisdiction.

11. Defence has made slow progress in implementing the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendations relating to T&E personnel competency and training requirements. No whole-of-Defence T&E personnel competency and training needs analysis has been conducted and T&E personnel training and competency requirements management vary significantly between the armed Services and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO, now the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG)). The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at strengthening the enterprise-level management of Defence’s T&E workforce.

Managing preview test and evaluation

12. Defence has implemented the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendation that it mandate a default position of engaging specialist T&E personnel prior to seeking First Pass government approval for acquisition options to proceed into detailed analysis.

13. When implemented well, Defence preview T&E has mitigated acquisition risks, particularly with respect to off-the-shelf (OTS) equipment acquisitions. OTS defence equipment acquisitions are not risk free and acquisition risks still need to be managed through the conduct of preview T&E and operational T&E.

14. The mixed experience with the MRH90 helicopter acquisition and other recent OTS acquisitions, such as Land 121 (medium and heavy vehicle fleet) and Land 125 (F88 Steyr rifle), underscore the importance of OTS equipment being subjected to T&E sufficient to allow the mitigation of cost, schedule and capability risks.

Managing development, acceptance and operational test and evaluation for Defence’s amphibious capability acquisition

15. Initial Materiel Release for LHD 1, HMAS Canberra, was declared in October 2014 with system acceptance test procedures ongoing and many test reports not submitted for Defence’s approval. LHD 1’s report of materiel state provided Navy with an assessment of remaining technical, operational and safety management system risks at the time of the ship’s release by DMO to Navy. Navy decided to accept the risks identified by the T&E, along with remediation plans, and the ship received Initial Operational Release into operational T&E in November 2014. The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at reducing risk in the transition of capability from the acquisition phase to operations.

16. Early operational T&E of HMAS Canberra commenced against a backdrop of significant work required to verify contractual compliance with 451 function and performance specifications, which had not occurred at the time of System Acceptance and Initial Materiel Release. Among those 451 were known defects and deficiencies within the ship’s communications system, radar system, combat management system, sewage system and logistic support system.

17. HMAS Canberra is scheduled to achieve its Initial Operational Capability milestone during the fourth quarter of 2015, at which time it will be able to undertake its humanitarian assistance and disaster relief support role. Both LHDs and their landing craft are scheduled to undergo Final Operational Capability T&E during Exercise Talisman Sabre in 2017, and Defence anticipates declaring Final Operational Capability in the fourth quarter of 2017, some 12 months later than originally scheduled. The MRH90 helicopters to be embarked upon the LHDs are forecast to achieve Final Operational Capability in July 2019, some five years later than originally scheduled.

Future directions for the governance of Defence test and evaluation

18. The establishment of the Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office in 2007 and a T&E Principals’ Forum in 2008, along with the finalisation of an overarching T&E policy in 2015, have provided Defence with a stronger basis for the management of T&E. Notwithstanding these positive developments, this performance audit has highlighted the inherent challenges in Defence’s entity-level management and conduct of T&E, which remains distributed across 12 internal organisations. Scope remains to improve key aspects of Defence’s administration, specifically: assuring consistency in the conduct of T&E and compliance with whole of entity T&E requirements; establishing entity-level performance measures for T&E; and T&E personnel competency management.

19. The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at strengthening enterprise-level governance and advisory arrangements for T&E, in the context of Defence’s implementation of reforms arising from the April 2015 First Principles Review.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.48 |

To strengthen the enterprise-level management of the T&E workforce, the ANAO recommends that Defence:

Department of Defence response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.22 |

To reduce risk and assist the transition of capability from the acquisition phase to operations, the ANAO recommends that prior to System Acceptance, Defence ensures that material deficiencies and defects are identified and documented, and plans for their remediation established. Department of Defence response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 5.14 |

In the context of its implementation of reforms arising from the First Principles Review, the ANAO recommends that Defence introduce arrangements to provide the Vice Chief of the Defence Force and Capability Managers with enterprise-level advice on the coordination, monitoring and evaluation of the adequacy and results of Defence T&E activities. Department of Defence response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

The Department of Defence’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

Defence places a high priority on Test and Evaluation (T&E) to inform decision-making in project acquisitions and risk management during the acceptance into service. Defence develops complex capabilities and T&E is an important practical means to help to mitigate the risk inherent in such endeavours. As such Defence welcomes this audit.

The audit is timely as Defence has published centralised policy on T&E and is undertaking fundamental organisational reform through the First Principles Review (FPR). The ANAO’s three key recommendations are agreed by Defence and will be used to strengthen governance and leadership in T&E, and to ensure Defence decision-making is, wherever possible, based on real and independent test results as early as possible in every project. Defence is committed to addressing the recommendations of the ANAO Report via the FPR reforms of the Defence Capability Life Cycle, which will include improved outcomes for Defence T&E.

Defence notes the ANAO concerns in the report regarding the T&E of the Canberra Class amphibious ship, HMAS Canberra that was the one major case study used in the audit. This amphibious capability is one of the most complex maritime capabilities brought into ADF service. While Defence T&E has matured over the last several years, the new Defence T&E policy and governance framework was not implemented in time to influence the T&E planning in support of acceptance into service of this major capability. Navy made well-considered risk based decisions in accepting the Canberra Class amphibious ship into service, having taken account matters such as the materiel data presented, the overall schedule of the introduction of the capability, and the management of ongoing issues such as defects and safety. The Chief of Navy has undertaken, and continues to undertake, with all Defence stakeholders, a detailed and deliberate assessment of the risks that are present in this new capability.

Defence’s T&E focus remains the timely achievement of capability that is safe, effective and suitable for ADF activities and operations.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian Defence Force (Defence) capability comprises major systems, such as ships, aircraft and land vehicles operated by Defence personnel, and other elements such as supplies and facilities that contribute to the conduct of Defence operations. The acquisition of major systems is subject to Defence’s test and evaluation (T&E) arrangements that seek to provide:

… decision-makers [with] factual information to help assess risks to achieving the desired capability. T&E in Defence is a deliberate and evidentiary process applied … to ensure that a system is fit-for-purpose, safe to use and that Defence personnel have been trained and provisioned with the enduring operating procedures and tactics to be an effective military force. As such T&E contributes to confirming legal obligations are met and documented in areas like fiduciary, environmental compliance and workplace health and safety.3

1.2 Defence’s T&E arrangements cover the following phases:

- Preview T&E–assists analysis and refinement of major equipment acquisition options presented to government for First or Second Pass approval by government.4

- Developmental T&E–assists the design and development of a system during the acquisition phase or during system upgrades. It provides Defence with the information needed to evaluate a product’s progress toward achieving contractually specified function and performance requirements.

- Acceptance T&E–provides Defence with the information needed to verify contractual compliance of equipment offered by contractors for System Acceptance approval by the acquisition authority.5 Acceptance T&E also informs the Initial Materiel Release decision to transition a system from its construction phase to its in-use phase. Defence’s Capability Managers6 rely on acceptance T&E to inform their decision to approve a system’s Initial Operational Release into operational T&E.7

- Operational T&E–provides Defence with the information needed to determine if the acquired equipment is operationally effective and suitable when examined under realistic operating conditions by representative operational personnel. It is used to inform the Capability Manager of a system’s Initial Operational Capability, and to determine when a system has achieved Final Operational Capability.8,9 Defence equipment may undergo follow-on operational T&E once Final Operational Capability has been achieved. This T&E phase reviews a system’s effectiveness and suitability in the context of changing operational requirements.

1.3 Figure 1.1 provides a simplified illustration of Defence’s T&E arrangements, respective capability system life cycle milestones and the authorities responsible for approving milestone achievement.

Figure 1.1: Capability life cycle – T&E phases, acquisition milestones and approval authorities

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence records.

Audits and external reviews of Defence test and evaluation

1.4 The ANAO conducted a performance audit of Defence’s T&E program in 2001–02 which found that there was little evidence of effective corporate initiatives to support the efficient and effective use of Defence’s T&E resources.10 Since that time, aspects of T&E have featured in a number of ANAO audits11, and there has also been ongoing Parliamentary interest in this subject. Most recently, in August 2012, the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee (the 2012 Senate Inquiry) reported on an inquiry into Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects. The report identified several deficiencies in the way T&E was being utilised to support Defence major capital equipment acquisitions and made a range of recommendations. Five of the recommendations, to which the then Government agreed, were directly related to T&E (see Appendix 2).

1.5 The findings of the 2012 Senate Inquiry were broadly consistent with previous audits and reviews, which also raised issues relating to the conduct, oversight and resourcing of Defence T&E (see Table 1.1). In December 2012 and May 2014, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit identified Defence T&E as an audit priority of Parliament in recognition of the ongoing importance of T&E.

Table 1.1: Common themes in previous reviews

|

Theme |

ReviewA,B |

||||

|

2002 ANAO T&E audit |

2003 Senate Inquiry |

2003 Kinnaird Review |

2008 T&E Roadmap |

2012 Senate Inquiry |

|

|

Inconsistent conduct of T&E. |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Inadequate oversight of T&E training. |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Inadequate resources for T&E. |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Poor translation of T&E policy and process into practice. |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Misunderstanding of T&E’s role as an assurance mechanism for the delivery of expected capability. |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

Note A: Ticks indicate whether an issue was raised in a review.

Note B: ANAO Audit Report No. 30 2001-02 Test and Evaluation of Major Defence Equipment Acquisitions, January 2002; Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Commonwealth of Australia, Report on the inquiry into materiel acquisition and management in Defence (2003); Defence Procurement Review (Malcolm Kinnaird AO, chairman), August 2003—‘the Kinnaird Review’; Department of Defence, Defence Test and Evaluation Roadmap, Defence, Canberra, 2008; and Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Commonwealth of Australia, Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects, August 2012.

Source: ANAO analysis of reviewed documents.

Audit approach

1.6 The audit objectives were to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the T&E aspects of its major capital equipment acquisition program; and to report on Defence’s progress in implementing T&E recommendations made in the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee’s August 2012 report, Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects.

1.7 To form a conclusion against the objectives, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence’s organisational structures, roles and responsibilities enable the coordinated application of adequate T&E at each stage of the capital equipment project life cycle;

- Defence’s T&E policy and procedures are suitably designed and applied as intended;

- Defence invests in a broad range of training and skills development for T&E personnel to enable the application of necessary T&E expertise throughout the capital equipment project lifecycle; and

- the T&E aspects of capital equipment acquisition are transparently reported to inform decision making and management of technical risks that may impact the development and maintenance of the major systems component of the Fundamental Inputs to Capability.12

1.8 The audit scope included: Defence’s T&E policy; T&E organisational structures, roles and responsibilities; coordination of T&E between the then Defence Capability Development Group (CDG), the then Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) and the armed Services; the management of T&E personnel competence development; and the implementation of T&E for related major equipment acquisitions. The audit scope also responded to ongoing Parliamentary interest in Defence’s T&E program.

1.9 On 1 April 2015, the Australian Government released the First Principles Review of Defence13, which contained recommendations regarding Defence’s organisational structure, including the establishment of a single end-to-end capability development function. This involved merging the then DMO and some functions of CDG to form a Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG). Consequently, this audit report primarily focuses on Defence’s T&E organisational structures, roles and responsibilities prior to the implementation of First Principles Review recommendations. However, the audit report pays specific attention to the position of T&E in Defence’s future structure.

1.10 The audit method involved analysis of:

- Defence T&E policy and procedures and T&E personnel skills development;

- Defence records relating to the implementation of recommendations made by the 2012 Senate inquiry that relate to T&E;

- project records relating to Defence’s evolving amphibious deployment and sustainment capability; and

- records relating to off-the-shelf equipment acquired through US Foreign Military Sales contracts and direct commercial sales contracts.

1.11 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $544 500.

2. Key developments in Defence’s management arrangements for test and evaluation

Areas examined

This chapter examines key developments within Defence relating to T&E institutional arrangements, T&E policy and processes, and the management of T&E personnel.

Conclusion

Defence has made progress towards its goal of a ‘unified’ approach to T&E, particularly in terms of establishing a lead authority for T&E, and finalising its overarching T&E policy framework. However, ensuring consistency in the conduct and use of T&E remains inherently challenging, as Defence has 12 organisations that conduct T&E—each with their own procedures and reporting accountabilities.

Defence’s progress in establishing T&E personnel competency frameworks has been slow and remains incomplete. No whole-of-Defence training and competency needs analysis for T&E personnel has been conducted, and the competency frameworks in use vary significantly between the armed Services and the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at strengthening the enterprise-level management of Defence’s T&E workforce.

Introduction

2.1 A well-managed T&E program consists of suitably qualified and experienced personnel undertaking T&E in accordance with sound policy and with support from appropriate institutional arrangements. As noted in Chapter 1, since the early-2000s several ANAO audits and external reviews of Defence have identified deficiencies in these aspects of Defence’s T&E program and provided recommendations for improvement.

2.2 In this chapter the ANAO examined key developments in Defence’s:

- institutional arrangements supporting the conduct of T&E;

- T&E policy and procedures; and

- T&E personnel training and competencies.

Does Defence have a unified approach to the conduct of test and evaluation?

Defence has 12 organisations that conduct T&E activities. While this approach is beneficial for developing, maintaining and applying specialised T&E expertise, it increases the risk of inconsistent conduct of T&E. This risk places a premium on Defence having effective T&E leadership and governance arrangements.

In 2007 Defence established a lead authority for T&E–the Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office–to provide advice and consultancy support on T&E issues and to develop Defence’s overarching policy on T&E.

2.3 Defence has recognised, since at least the mid-1990s, the benefits available from a ‘unified’ approach to T&E, which facilitates the effective and efficient use of available T&E resources and avoids unnecessary duplication of effort and resources.14 A key institutional reform was the establishment in 2007 of the Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office (ADTEO) to replace the then ‘Directorate of Trials’ and to lead T&E in Defence. ADTEO is the lead Defence authority for T&E, and is responsible for providing advice and consultancy on T&E issues, and for managing joint and single-Service trials in support of T&E activities. ADTEO is also responsible for the provision of Defence policy on T&E through the Defence Capability Development Manual (DCDM), which provides more detailed authoritative guidance on T&E than the Defence Instructions for T&E that it replaces.

2.4 ADTEO’s establishment was supported by the publication in 2008 of the Defence Test and Evaluation Roadmap, which identified the need for wide-ranging T&E management improvements. These included the need to:

- centralise, through ADTEO, the coordination of all T&E resources, policy and processes to ensure the most efficient and effective application of T&E;

- support existing Defence T&E agencies and other stakeholders in their delivery of T&E by the provision of adequately skilled T&E professionals who are trained and equipped to engage with emerging technologies15 in future capability systems; and

- centralise and coordinate the management of T&E facilities and equipment to ensure projects in the Defence Capability Plan16 can be delivered into service on time.

2.5 During 2012, the Chief of the Defence Force tasked ADTEO with examining Defence T&E policy and practice, and to report its findings to the Defence Chiefs of Service Committee in September 2012. ADTEO’s report recommended seven areas for improvement, including consolidation of T&E policy, management of Army and Navy T&E personnel and consistency between Joint and Service T&E. The Chiefs of Service Committee agreed to six of the seven recommendations.17

Defence’s test and evaluation organisational structure

2.6 Successive Defence reforms in relation to the institutional arrangements supporting T&E have emphasised centralisation, coordination and consolidation of key functions, principally in ADTEO. However, responsibility for developing specific procedures for the conduct of T&E and the conduct itself of T&E remains distributed among 12 organisations within Defence, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Outline of Australian Defence T&E agencies

Notes for Figure 2.1

Note A: Acronyms used in Figure 2.1:

ADTEO: Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office.

RANTEAA: Royal Australian Navy Test, Evaluation, and Acceptance Authority.

LEA: Land Engineering Agency.

ARDU: Aircraft Research and Development Unit.

AMAFTU: Aircraft Maintenance and Flight Trials Unit.

JPEU: Joint Proof and Experimental Unit.

AMTDU: Air Movements Training and Development Unit.

FEG OT&E Cells: Force Element Group Operational T&E Cells.

JEWOSU: Joint Electronic Warfare Operational Support Unit.

ADFTA: ADF Tactical Data Link Authority.

CIOG: Chief Information Officer Group.

I&S: Intelligence and Security Group.

Note B: CIOG and I&S are independently responsible for the conduct of T&E across the capability system life cycle for projects under their purview.

Note C: While the acquisition organisation is primarily responsible for acceptance T&E, Service and Joint T&E organisations may provide support as required.

Note D: Developmental T&E is conducted to assist with the development of a system, product or service. Therefore, for most Defence projects and programs, developmental T&E is undertaken by the contractor developing the system, product or service. The outcomes of this T&E are reviewed by Defence personnel and used in the system design and development process to support verification of technical or other performance criteria and objectives.

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.7 Defence’s 12 T&E organisations include acquisition organisations, single and Joint Service T&E organisations, and specialist T&E organisations.18 Each of these organisations have their own T&E manuals, report their T&E activities independently to their respective Capability Manager and are all required to comply with one or more of Defence’s three technical regulatory management manuals.19 The exception to those arrangements is the Army, which has embedded a significant proportion of its operational T&E staff in ADTEO.

2.8 Defence’s decentralised approach to T&E is beneficial to developing, maintaining and applying specialised T&E expertise. For example, fixed wing flight testing is carried out by the Air Force, embarked rotary wing flight testing in the maritime environment is conducted by the Navy and Army conducts its own rotary wing testing. Where centralised T&E management is practical, it has been undertaken. For example, ADTEO conducts all Early Test planning and CASG conducts acceptance T&E. However, the generally decentralised structure increases the risk of an inconsistent approach to T&E, which makes it ‘difficult to identify gaps to ensure T&E is managed and conducted to an appropriate level’.20 This risk places a premium on the effectiveness of Defence leadership and governance arrangements, particularly as T&E governance needs to extend over 12 T&E organisations. Chapter 5 discusses future directions for Defence’s T&E governance arrangements.

Does Defence have a policy framework to support the consistent conduct of test and evaluation?

Defence has recently completed and published its overarching T&E policy in the Defence Capability Development Manual (DCDM). This manual expands upon former Defence Instructions concerning Defence T&E policy and completes a longstanding commitment to the Parliament.

Defence has more to do to provide a comprehensive and integrated T&E framework to its project offices by ensuring: the DCDM aligns with Navy, Army and Aerospace regulatory management manuals; the DCDM is aligned with new organisational structures arising from the implementation of the First Principles Review1; and that subsidiary T&E policy and procedural guidance manuals used by the various project offices are consistent with the DCDM.

2.9 Each of Defence’s internal T&E organisations (identified in Figure 2.1) conducts T&E in accordance with regulatory manuals, and with a range of project management policy and procedural guidance manuals. The capstone of these documents is Part Three of the DCDM21, which provides centralised policy describing:

- how T&E is to be conducted by Defence;

- the requirements for organisations and individuals conducting T&E;

- what T&E planning is required for major projects, from project initiation to withdrawal from service; and

- how T&E policy compliance is to be assured and non-compliance resolved.

Updating Defence test and evaluation policy and procedures

2.10 In 2003, Defence advised the Parliament22 that a review and redevelopment of Defence T&E policies had been initiated by ADTEO’s predecessor organisation. This followed the tabling of the ANAO’s 2002 audit report, which had recommended that Defence review and update its T&E policy organisation and responsibilities and articulate the way that the policy is to be implemented.23 However, by 2008, the Defence T&E Roadmap (discussed in paragraph 2.4) indicated that ADTEO was still ‘reviewing all policies, procedures and guidance in order to develop a standardised framework which ensures consistency and alignment at all levels’.24 Further, the review had not been completed by the time of the 2012 Senate Committee inquiry into Defence procurement, and the Committee recommended the immediate finalisation of central defence policy on T&E to be implemented by Defence’s Capability Managers. The 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendation was in line with the committee’s recommended shift of full accountability to Capability Managers for all technical assessment of capability procurement and sustainment (independently assessed in conjunction with the then Defence Science and Technology Organisation).25

2.11 In September 2012, Defence decided that ADTEO should consolidate tri-service T&E strategic direction, policy and procedures into the DCDM. In November 2013, the Chiefs of Service Committee and DMO agreed to a revised Part Three of the DCDM, and by December 2014, the revised T&E policy was in use by all Defence T&E agencies and an incomplete version of Part Three of the DCDM26 was published. A completed version of Part Three of the DCDM was published in June 2015, some 12 years after Defence had originally advised Parliament that a review and redevelopment of Defence T&E policy and procedures was underway.

2.12 The DCDM requires specialist T&E personnel to be engaged pre-First Pass, during system development and acceptance for all projects including military off-the-shelf/commercial off-the-shelf acquisitions. This requirement addresses a longstanding Parliamentary interest that Defence’s T&E policy should adopt a ‘cradle to grave’ philosophy.27

2.13 While the publication of Part Three of the DCDM completes a longstanding commitment to the Parliament, it is also important that Defence puts in place a process to ensure that: the DCDM aligns with Navy, Army and Aerospace technical regulatory management manuals; the DCDM is aligned with new organisational structures arising from the implementation of the First Principles Review (see paragraph 1.9); and that subsidiary T&E policy and procedural guidance manuals prepared by the various T&E organisations are consistent with the DCDM. In October 2015 Defence informed the ANAO that:

The process to ensure alignment with Technical Regulatory Framework resides within [the T&E Principals’ Forum28] where each year issues can be raised and policy improvements discussed. In general, an annual update of the T&E policy is planned following the outcomes of the T&E Principles Meeting, held in [April or May] each year, with follow up meetings if required.

2.14 In August 2015, Defence advised the ANAO that it will be aligning its T&E policy with technical regulatory manuals and acquisition project management manuals during the next DCDM update, planned for November 2015. Defence also expects to update the DCDM in 2016, to incorporate First Principles Review outcomes and new Defence Capability Life Cycle processes. In addition, Defence is implementing a newly developed Quality Management System, which is to streamline and standardise the lower level procedures used by Defence’s capability acquisition and sustainment project offices. As these project offices have T&E responsibilities, Defence will need to ensure that their procedures align with T&E policy set out in the DCDM.

Policy changes in response to 2012 Senate Committee inquiry

2.15 The 2012 Senate Committee report included a recommendation that Capability Managers should require their developmental T&E practitioners to be an equal stakeholder with the then Defence Science and Technology Organisation in the pre-First Pass risk analysis and specifically to conduct the pre-contract evaluation so they are aware of risks before committing to a project.29

2.16 In response, Defence included guidance covering preview T&E in the DCDM. ADTEO oversees or conducts preview T&E and provides preview T&E reports to assist First or Second Pass approval submissions to government. Preview T&E may involve Defence Science and Technology Organisation personnel. However, any Defence T&E organisation or delegated staff/units may be tasked by ADTEO to conduct preview T&E. As discussed in Chapter 3, well-conducted preview T&E policy should result in improved pre-First Pass risk analysis and pre-contractual cost and benefit evaluation, resulting in Defence being more aware of acquisition risks and so better inform the First and Second Pass approval process.

2.17 The 2012 Senate Inquiry also recommended improvements in Defence’s Technical Risk Assessment and Technical Risk Certification processes, which contribute to the development of First and Second Pass approval submissions. The committee saw a need for a technical risk reporting structure to be transparent such that the assessments could not be ignored without justification to the key decision-makers (such as the Minister for Defence).30 In conducting this audit, the ANAO observed significant improvements in Defence’s Technical Risk Assessment policy and process manual. The DCDM would be improved if it included a more complete reference to this manual.

Is Defence’s test and evaluation policy framework being applied consistently?

Defence’s application of its T&E policy and procedures to the acquisition projects examined in this audit and past performance audits has varied, driven primarily by the relative complexity of Defence projects. Some project offices manage complex developmental T&E with Defence as the prime system integrator, while other offices manage acceptance T&E of mature products that have already undergone acceptance T&E by another jurisdiction.

2.18 The DCDM includes policy guidance on arrangements to assure compliance with T&E policy and to resolve non-compliance. Also, Defence equipment acquisition personnel are required by Defence’s technical regulatory management instructions and manuals to conduct T&E and/or examine T&E reports. This activity enables these personnel to certify that the products they are accepting on behalf of Defence comply with specified standards and are safe and technically fit for service in their intended role.

2.19 T&E policy and procedural compliance arrangements are described below, along with examples of these arrangements in practice at key phases in the Defence capability life cycle, drawn from the case studies included in subsequent chapters in this report.

Preview test and evaluation policy compliance arrangements

2.20 The Director General T&E31 is responsible for determining compliance with preview T&E policy as each Defence Capability Plan submission progresses through its First and Second Pass approval processes. ADTEO is responsible for reporting to the Chief of CDG any non-conformance with preview T&E policy.

|

Case study 1. Example of preview test and evaluation: Land 121 Phase 3B project |

|

In 2009, ADTEO implemented preview T&E in the LAND 121 Phase 3B project to ensure that prior to acquisition contracts being signed, the vehicles selected for Army complied with specified standards and were technically fit for service in their intended role. This followed the project’s failure in 2007 to conduct adequate T&E during the project’s initial tender process. This failure resulted in Defence abandoning acquisition contract negotiations and undertaking a tender resubmission process. Preview T&E conducted in 2009 enabled Defence to identify those vehicles suitable for inclusion in the tender resubmission process.A |

Note A: The Land 121 Phase 3B acquisition is examined in detail in ANAO Report No. 52 2014-15, Australian Defence Force’s Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Replacement (Land 121 Phase 3B), June 2015.

Developmental and acceptance test and evaluation policy compliance arrangements

2.21 Managing compliance with developmental and acceptance T&E policy is a shared responsibility between the acquisition authority and the applicable Service T&E agency. A project’s T&E Planning Group is required to report to the associated Project Management Stakeholder Groups and Capability Manager Stakeholder Groups if a T&E program is failing to adequately ensure:

- T&E managers and key T&E staff assigned to the acquisition are competent in their respective roles;

- Defence T&E staff assigned to contractors or foreign military programs appropriately report T&E results;

- contractors report T&E results and progress;

- T&E working groups are effective;

- stakeholders, including affected T&E agencies, remain involved in their relevant aspect of the T&E program; or

- T&E Master Plans remain current and suitable.

2.22 If T&E policy non-compliance is not resolved by the appropriate T&E Planning Group, Project Management Stakeholder Group or the Capability Manager Stakeholder Group (once notified), the matter is to be referred to ADTEO, which is then required to investigate and, if necessary, raise the issue at the project’s next Gate Review Board or to the Defence Capability and Investment Committee. This process aligns with the standard tiered approach to issues resolution, whereby resolution is attempted at the lowest level practicable, with unresolved issues elevated to higher organisational levels if they are not resolved promptly.

|

Case study 2. Example of issues resolution processes in operation: Landing Helicopter Dock project |

|

In August 2012, the JP2048 Phase 4A/B Landing Helicopter Dock Project’s (LHD Project) Performance Gate Review Board was made aware that the LHD Project was proactively addressing workforce pressures as a result of 17 vacant positions, including eight considered critical to the completion of test and verification activities. By the time of the August 2013 Performance Gate Review Board, two T&E positions remained vacant, and this risk was being mitigated through temporary transfers of ADTEO personnel to the LHD Project Office. In this example, the T&E policy compliance mechanism functioned in identifying issues for resolution, and then acted to resolve these issues, including by temporarily transferring ADTEO personnel into the LHD Project Office. |

Operational test and evaluation policy compliance arrangements

2.23 Each Capability Manager has operational T&E policy and processes that are to comply with policy set out in the DCDM. The approach taken varies according to the Service to which a project relates. Aerospace and maritime projects use internal test readiness and compliance checking functions provided by each Service32, while land projects rely on ADTEO to provide this function. However, there can be variability with the extent to which Defence’s arrangements to assure compliance with T&E policy are translated into practice. An example of such variability was the processes used to release the first LHD, HMAS Canberra, and the MRH90 helicopters into operational T&E.

|

Case study 3. Example of variability: Amphibious capability seaworthiness and airworthiness board reviews |

|

LHD acceptance was governed by the Navy Regulatory Framework, which involves the Royal Australian Navy Test, Evaluation and Acceptance Authority, and Navy’s technical, operational and safety management system regulators reviewing the ship’s report of material state and Safety Case Report, and making recommendations concerning the LHD’s Initial Operational Release into operational T&E. On the basis of these recommendations, the ship received approval to operate within limitations set by the Chief of Navy. As at October 2015, the first LHD, HMAS Canberra, had not been the subject of Navy’s Seaworthiness Board reviews, the first of which is planned for the fourth quarter of 2016. The MRH90 helicopters, which are to operate from the LHDs, have been introduced into service within a regulatory framework subject to annual review by an independent Airworthiness Board. The Airworthiness Board conducted six Special Flight Permit reviews and three Airworthiness Board reviews for the MRH90. In April 2013 the MRH90 was awarded an Australian Military Type Certificate.A In both instances, operational T&E is continuing within operational limitations set by the Chief of Navy and the Chief of Air Force. |

Note A: See ANAO Audit Report No.52, 2013–14, Multi-Role Helicopter Program, June 2014, pp.170–171.

2.24 The variability highlighted above illustrates that this is an area requiring ongoing management focus if the intent behind the T&E policy is to be assured. As the example below illustrates, there are existing mechanisms that could, if implemented well, provide periodic assurance to Defence that acquisition project offices have adhered to T&E policy.

|

Case study 4. Example of Defence’s technical regulation instructions and management manuals |

|

In addition to the DCDM policy requirements, Defence acquisition and sustainment project offices are subject to technical regulatory instructions and associated management manuals. Under this arrangement, organisations are granted Engineering Authority once they are recognised by the Technical Regulatory Authorities as being competent in assessing the design, manufacture or maintenance of Defence materiel. Defence advised the ANAO that all post-Second Pass approved project offices had been granted Engineering Authority status. Technical Regulatory Authorities may audit materiel to ensure that it is properly certified. These compliance assurance audits review evidence recorded in support of design certificates and confirm that recognised organisations are employing sound processes in their approved engineering and quality management systems. The audits may also examine evidence of policy and process compliance, report on areas of non-compliance and issue ‘Corrective Action Requests’. If non-compliances are not resolved, the regulatory authority may make a recommendation regarding the suitability of the organisation to retain its Engineering Authority. While this process nominally provides assurance to Defence that project offices have been assessed as compliant with T&E policy, Defence advised that, to date, no Corrective Action Requests relating to the conduct of T&E by Engineering Authorities had ever been issued.A This outcome would imply that no substantive deficiencies have ever been found in any audits conducted. The ANAO notes that this positive outcome is hard to reconcile with the significant technical, operational and safety management system deficiencies identified in other high-profile acquisition projects previously audited by the ANAO, and the shortcomings identified by Defence’s regulators in the LHD Project’s report of materiel state (known as the TI 338 report) and Safety Case Report (see Chapter 4). |

Note A: Defence was unable to advise the total number of audits conducted. However, Army and Navy advised that, on average around 8-10 audits and 7-8 audits respectively are conducted annually, while Air Force advised that they have conducted an average of 22 audits of Defence’s AEOs per year over the last five years.

Does Defence have an adequate framework for managing test and evaluation personnel training and competency requirements?

Defence has made slow progress in implementing the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendations relating to T&E personnel competency and training requirements. No whole-of-Defence T&E personnel competency and training needs analysis has been conducted and T&E personnel training and competency requirements management vary significantly between the armed Services and DMO (now CASG).

2.25 Defence’s approach to the training of T&E personnel has been the subject of ongoing concern. In 2001, the ANAO found that Defence’s approach to providing T&E training was decentralised and ad hoc, and not well linked in terms of coordination or information sharing.33 Defence’s 2008 Roadmap also identified substantial ongoing deficiencies in the area of T&E training, and emphasised ADTEO’s role in overseeing T&E training across the entity. The 2012 Senate Inquiry was sufficiently concerned about the issue to suggest that each Capability Manager should ensure adequate skilled resources are available to oversee all T&E activity in line with central policy, as part of all acquisitions, including off-the-shelf equipment, and as part of the Capability Managers’ total responsibility for procurement, both prior to and after Second Pass.34 The committee also recommended that Defence build on the capability already extant in aerospace to identify training and experience requirements for operators and engineers in the land and maritime domains.35 The ANAO assessed Defence’s progress in addressing these recommendations.

Application of policy requirements across Defence

2.26 Under the DCDM, each Defence T&E organisation is responsible for establishing the minimum competencies required of Defence personnel employed in planning, managing or conducting T&E for their respective organisation. While ADTEO is responsible for ensuring that these competencies are specified in the DCDM, it does not make any assessment as to the suitability of specified competencies.

2.27 As at June 2015, 11 of Defence’s 12 T&E organisations (identified in Figure 2.1) had specified the T&E competencies for their personnel and included these in the DCDM, however the Intelligence and Security Group had not. The ANAO also observed substantial variation in the T&E competency frameworks between each of the organisations. For example, the ADTEO competency framework provides a breakdown of required experience and training by position, whereas the Land Engineering Agency framework states more broadly the requirement for personnel conducting system integration and verification to have undertaken training in Systems Engineering.

Assessing and monitoring competency needs and training gaps

2.28 At the time of this audit, no comprehensive, whole-of-Defence T&E personnel competency and training needs analysis had been conducted. An analysis of competency levels (qualifications, training and experience) would assist Defence to improve its T&E personnel training arrangements by providing an enterprise-wide view of the competencies available, employed and required by each armed Service and CASG project offices.

2.29 In discussions with the ANAO, Defence personnel advised that in practice, the tracking and monitoring of T&E qualifications and experience across the entity remains highly decentralised and variable.36 The ANAO sought to draw together the available data on the number of Defence personnel with formal T&E training, the number of positions within each Service requiring T&E qualified personnel, and the number of qualified personnel filling each of those positions. This data was not readily available and there were substantial limitations on the reliability of data that could be provided by Defence. In August 2015, CASG informed the ANAO that:

whilst it is true Defence currently does not hold this workforce data at the enterprise level, it needs to be highlighted that for any business unit operating under technical regulator authority or being NATA [National Association of Testing Authorities] accredited they would hold this workforce data locally.

2.30 Within the limitations of the available data, the ANAO has observed that Defence has made extensive investments in T&E training, with more than 1000 qualified T&E personnel identified across Defence. However, in the absence of an enterprise-wide understanding of the existing T&E workforce and an analysis of training and competency needs, the data does not provide Defence management with the information required to assess whether the number of trained personnel and their competency levels meets the entity’s needs.37

Test and evaluation personnel competency development within the armed Services and the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group

2.31 The 2012 Senate Inquiry recommended that Defence build on the capability already extant in aerospace to identify training and experience requirements for operators and engineers in the land and maritime domains. The inquiry noted that Capability Managers will need to invest in a comparable level of training to enable their personnel to conduct (or at least participate in) developmental testing. The committee stated that the intention of this recommendation was ‘to provide a base of expertise from which Defence can draw on as a smart customer during the [F]irst [P]ass stage and to assist in the acceptance testing of capability.’38

2.32 Implementation of the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendations vary between the Services and CASG. In September 2012, the Chief of the Defence Force directed the Chief of Navy and Chief of Army to review the management and independence of T&E specialists assigned to Maritime and Land projects in order to determine the best method for developing skills and managing career progression. Progress was slow, and in January 2014, the Chief of the Defence Force agreed to grant the Army and Navy a further 12 months to complete their reviews. In November 2014, the Chiefs of Service Committee determined that Army and Navy’s responses—discussed below—were appropriate and acceptable for implementation.

Navy T&E personnel

2.33 As reported above, the 2012 Senate Inquiry commented that Capability Managers will need to invest in a comparable level of training to the Air Force to enable their personnel to conduct (or at least participate in) developmental testing, as occurs in Aerospace projects. However, at present, the Navy’s T&E authorities, the Royal Australian Navy Test, Evaluation and Acceptance Authority, and the Aircraft Maintenance and Flight Trials Unit are predominantly responsible for operational T&E. This limits their ability to conduct (or at least participate in) developmental T&E as envisaged by the Committee, and hence assist in the acceptance testing of Navy capability. In August 2015, Defence advised that little (if any) developmental T&E is conducted within maritime projects, as Defence’s general approach is to procure equipment with a mature design and a high technology readiness level.39,40

2.34 In July 2014, the Deputy Chief of Navy decided that Navy would not establish a specific T&E specialisation, but requested that Head Navy Engineering, Head Navy Capability, and Commodore Warfare41 identify and report the T&E skills necessary for personnel employed in their areas of responsibility. Head Navy Engineering reported that, while he had no defined requirements for T&E specialists:

The lack of a clear and agreed T&E operating model between Navy, CDG, and the DMO in regards to Developmental Testing and Acceptance Testing inhibits the identification of associated training requirements for the Navy Engineering Division, Navy technicians, and Navy Engineer Officers.

2.35 Head Navy Engineering also noted that under the career continuums developed through the Navy’s Rizzo Reform program42, all Navy technicians, Engineer Officers and Naval Engineers will necessarily be exposed to T&E activities, and that a fundamental knowledge of T&E was a requirement at senior ranks. In June 2015, Navy advised the ANAO that Naval Engineer Officers complete an intensive T&E module as part of their training, and a specialist operational T&E course is provided to Navy personnel if they are posted to specified operational T&E positions.

2.36 The improvements to Navy’s management of T&E personnel training and competency requirements described above have helped strengthen Navy’s understanding of its T&E workforce. Nevertheless, further work remains for Navy with respect to completing reforms arising from the Rizzo Reform program and the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendation, such as the formal incorporation of T&E education into the career continuums of Navy civilian engineers and technical sailors.

Army T&E personnel

2.37 In September 2014, Army established a management framework for a newly formed T&E sub-specialisation. The framework includes annual checks of T&E positions and competencies, with the first of these checks conducted on 19 March 2015. At this inaugural meeting Army remained uncertain as to the required makeup of its T&E workforce. It was agreed at the meeting that there remained a need to determine whether T&E experience was essential or desirable for personnel in those T&E positions identified by Army, the number of which had also not been determined. There remains a significant body of work for Army to complete in order to give effect to the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendation.

Air Force T&E personnel

2.38 T&E personnel training and competency management within the Air Force is generally regarded as more mature than in the Navy and Army, reflecting the requirements to demonstrate airworthiness and to meet technical regulatory requirements.43 In late 2012, the Air Force introduced a framework for managing T&E personnel following a review of flight test aircrew management.

Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group T&E personnel

2.39 T&E tasks undertaken by DMO (now CASG) project offices vary considerably. Some project offices manage complex developmental T&E with Defence as the prime system integrator, while others manage acceptance T&E of mature products that have already undergone acceptance T&E by another jurisdiction. As a result, each project office has specific personnel competency requirements–informed by the relevant Acquisition Categories described below–and depends on DMO (now CASG) meeting its needs on a project-by-project basis.

|

Box 1: Defence Acquisition Categories |

|

Acquisition Category I projects are Defence’s most strategically significant major capital equipment acquisitions. They are characterised by very high project and schedule management complexity and very high levels of technical difficulty, operating, support and commercial arrangements. Acquisition Category II projects are major capital equipment acquisitions that are strategically significant to Defence. They are normally characterised by high levels of complexity, such as project and schedule management complexity, and high levels of technical difficulty, operating, support and commercial arrangements. Acquisition Category III projects are major or minor capital equipment acquisitions that have a moderate strategic significance to Defence. They are normally characterised by moderate levels of complexity, such as project and schedule management complexity, and moderate levels of technical difficulty, operating, support and commercial arrangements. Acquisition Category IV projects are major or minor capital equipment acquisitions that have a lower level of strategic significance to Defence. They are normally characterised by low levels of complexity such project and schedule management complexity, and low levels of technical difficulty, operating, support arrangements and commercial arrangements. |

2.40 The DCDM notes that Acquisition Category I and Acquisition Category II project offices should be resourced with substantially better T&E management competency than the prescribed minimum. At the time of the audit, DMO had not reported any non-compliance with these requirements. Despite DMO not reporting any non-compliance with the qualification and experience requirements set out in DMO T&E procedures, an audit of DMO’s engineering and technical workforce management conducted in the first half of 2014 by a management consultancy firm found numerous deficiencies in DMO’s approach. The audit noted that DMO needed to attract, recruit and retain those engineers and technically skilled individuals who are best qualified to deliver DMO and government requirements. However, the audit found that DMO’s workforce management system was neither capable nor robust enough to deliver against these goals.

2.41 The audit recommended that DMO advise the Defence Learning Branch to conduct a skills audit of the DMO Materiel Engineering and Technical workforce and associated positions. Subsequently, in March 2015, DMO completed a whole-of-workforce Skills and Training Census in order to improve understanding of its personnel training requirements.44 As CASG (and the then DMO) does not have a distinct job family for T&E45 it is difficult to draw any direct conclusions about the health of the CASG T&E workforce from the results of the survey. However, the survey did include two questions that can provide some insight, as shown in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: DMO Skills and Training Census

|

Question |

Response |

|

As a manager, managing and conducting Verification and Validation activitiesA inclusive of supplier quality management and calibration is a critical skill for my work area. |

76 per cent |

|

85 per cent |

|

38 per cent |

|

Managing and conducting Verification and Validation activities inclusive of supplier quality management and calibration is a critical skill for my current or previous role. |

66 per cent |

|

78 per cent |

|

74 per cent |

Note A: Verification and validation is, broadly speaking, the term used by DMO for the activities reported throughout this report as test and evaluation.

Note B: Ratings of depth of skill and mitigation strategies are based on managers who rated the skill as critical to their work area. These results are linked to their parent question.

Note C: Ratings of substantial experience and formal qualifications/training are based on all materiel engineering and technical workforce respondents. These results are linked to their parent question.

Source: ANAO analysis, DMO 2015 Skills Census results.

2.42 Table 2.1 indicates that managers generally believe that their team has a good depth of skill for managing and conducting verification and validation activities, but were less confident that robust mitigation strategies were in place to manage skills shortages. Of those personnel indicating that verification and validation was a critical skill for their current or previous role, some three quarters indicated that they had substantial experience, formal qualifications/training or both.

2.43 These results may provide some limited assurance to Defence that, at an entity level, CASG personnel conducting verification and validation activities have the experience and qualifications/training required for their role. However, there remains scope for Defence to gain a greater appreciation of the skills and competency of its personnel at an individual level in order to facilitate the more effective and efficient application of these skills across Defence as a whole.

Joint projects T&E personnel

2.44 In May 2007, the then Chief of the Defence Force set out a vision for a revised joint force operations concept. This concept was developed further in 2011, and requires the individual Services and their enabling Groups to acquire capabilities that can be integrated to provide joint warfighting functions. These functions include: force application; force deployment; force protection; force generation and sustainment; command and control; and information dominance. The 2012 Defence Capability Plan lists 48 projects requiring varying amounts of joint T&E.

2.45 Defence relies on joint operational T&E to determine how well joint force capability development is progressing. As shown in Figure 2.1, Air Force and Navy have established operational T&E agencies and Army has adopted a centralised model, embedding a large proportion of its operational T&E staff in ADTEO. This structure leaves ADTEO responsible for the remainder of the ‘joint’ projects and for projects where the allocated Capability Manager has no recognised operational T&E capability.46

2.46 ADTEO has three personnel dedicated to joint T&E, and at the time of this audit they were assisted by two contractors. This team is required to develop ADTEO’s joint T&E capability and skills base, and to plan and coordinate the conduct of joint T&E for new projects. At the time of this audit, over 20 joint projects were reporting that their operational T&E from previous phases was ‘deficient, disjointed or incomplete’, and so were relying on future phases to remediate past operational T&E gaps and shortfalls.

2.47 Defence recognised in 2012 that ADTEO lacked the personnel, infrastructure and test resources required to implement joint operational T&E at the level required by the joint force operational concept. In 2012, it was assessed as highly unlikely that these deficiencies could be met within the Services and/or Australian Public Service personnel resources given the volume and diversity of capability that required joint operational T&E from 2013 to 2018. Given current resourcing pressures and levels of demand, this assessment has continued relevance, and resourcing issues require ongoing management focus to ensure the successful implementation of joint T&E.

Recommendation No.1

2.48 To strengthen the enterprise-level management of the T&E workforce, the ANAO recommends that Defence:

- identifies the training and competencies of the existing Defence T&E workforce;

- conducts a T&E personnel competency and training needs analysis for the whole entity; and

- monitors the availability of sufficient, appropriately trained T&E personnel in specific competency areas and takes steps to address any gaps identified.

Entity response: Agreed.

2.49 Noting proposed name change from ‘training needs analysis’ to ‘performance needs analysis’ in alignment with the systems approach to Defence learning and the Defence learning manual.

2.50 Defence acknowledges that decentralised T&E organisations are a governance challenge to achieve consistent use of T&E in support of all Defence acquisition projects. Defence agrees with the ANAO that competency of the T&E workforce is key to achieving more consistent use of T&E. Defence agrees to undertake a whole-of-Defence performance-needs-analysis for T&E competencies. Defence’s recent issue of a centralised policy for T&E is a first step that will be followed by better T&E governance to attain compliance and an assured T&E workforce.

3. Managing preview test and evaluation

Areas examined

This chapter examines Defence’s management of preview T&E for major off-the-shelf equipment acquisitions.

Conclusion

Defence’s recently released Defence Capability Development Manual reflects the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendation that Defence mandate a default position of engaging specialist T&E personnel pre-First Pass. When implemented well, Defence preview T&E has mitigated acquisition risks.

Introduction

3.1 As discussed in Chapter 1, preview T&E is used to assist the analysis and refinement of major equipment acquisition options presented to government at First and Second Pass approval.

3.2 Defence has long recognised the risk reduction value of T&E conducted early in the acquisition lifecycle. As noted in the 2008 Defence Test and Evaluation Roadmap:

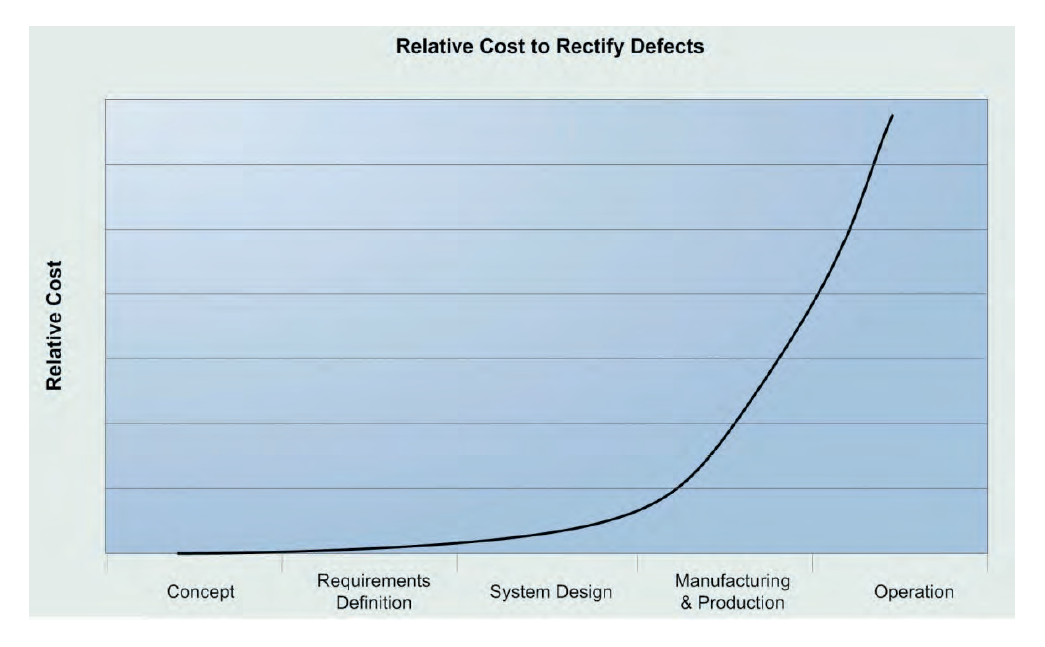

… the cost of correcting defects increases significantly the later in the life cycle that they are identified because of increasing system and sub-system complexity and integration. Because defects found earlier in the life cycle will cost significantly less to resolve than those identified later in the development process, T&E should be applied early in the system life cycle to help control system development costs.47

3.3 Defence has represented these escalating costs in its ‘Life Cycle Cost Escalation Model’ (see Figure 3.1). The figure shows that it may be extremely costly to fix requirements, design or construction defects found during a project’s operational T&E phase. The intent should be to detect and correct defects as early as possible while there remain sufficient financial and schedule resources to achieve the project’s approved outcomes.

Figure 3.1: Life Cycle Cost Escalation Model

Source: Department of Defence, Defence Test and Evaluation Roadmap, Defence, Canberra, 2008, p. 19.

3.4 The further a system’s development has satisfactorily progressed in T&E terms from initial concept and into operations, the lesser the risk of costly defects. It is therefore critical that acquisition options are thoroughly tested and evaluated to determine their risk profile in terms of operational concepts, system design, manufacturing and production, and operations. Defence has previously ranked the risk associated the various acquisition options as follows:

a. modifying extant platforms or combat systems which can be a lower risk, quicker and less costly option;

b. acquiring off‐the‐shelf (OTS) items, either military off‐the‐shelf (MOTS) or commercial off‐the‐shelf (COTS), without modification and accepting the trade‐offs necessary if they do not fully meet the requirement;

c. acquiring and modifying OTS items, either MOTS or COTS, recognising that this can be a high‐risk option;

d. integrating existing systems, military or commercial, which can again be a high‐risk option; or

e. pursuing new designs, which is the highest risk option.48

3.5 Consistent with Defence’s risk ranking, preview T&E will be particularly important in the case of OTS equipment acquisitions, which are a recognised mechanism for Defence to reduce equipment cost, schedule and performance risks. As indicated, OTS acquisitions may be categorised as MOTS equipment or COTS equipment. In both instances these products have already been delivered to another military, government body or commercial firm and hence are expected to have completed wide-ranging T&E.

|

Case study 5. Example of Defence’s acquisition of off-the-shelf equipment |

|

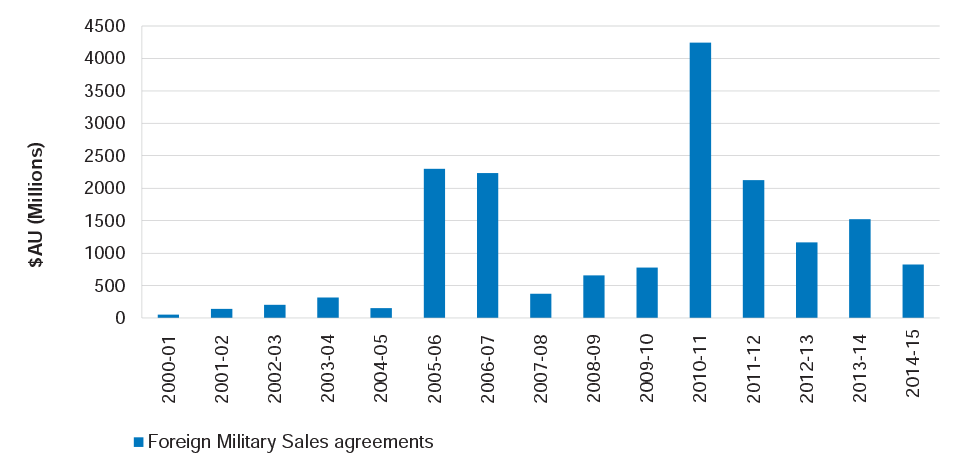

Defence has increasingly pursued OTS acquisitions in recent years. Defence sources its OTS equipment predominantly from the US through the US Government’s Foreign Military Sales program. The program manages government-to-government agreements for the sale of US defence articles and services, as authorised by the US Arms Export Control Act. The program operates on a ‘no profit/no loss’ basis, and must be funded in advance by the customer. Figure 3.2 (below) shows the then-yearA Australian Dollar value of Foreign Military Sales contracts from 2000 to 2015.B These expenditures totalled US$19.523 billion. Australia’s purchases in 2011 included two C-17 Globemaster III aircraft and associated equipment, parts, training and logistical support; AIM-120C-7 Air-to-Air missiles for the Air Force’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornet fleet; and through-life-support for Navy’s 24 MH-60R Seahawk helicopters. Australia’s purchases in 2012 included MH-60R Seahawk helicopter mission avionics systems, cockpits and support elements; and 10 C-27J Spartan aircraft and associated equipment, long lead spare parts and logistical support. |

Note A: Then-year prices are based on the cost of labour and materials and currency exchange rates at the time the expenditure occurred.

Note B: A 3.8 per cent Foreign Military Sales Administrative Surcharge is applicable to all purchases made through the US Foreign Military Sales program. Other additional Foreign Military Sales fees include a Contract Administration Services Surcharge of 1.5 per cent, and a Nonrecurring Cost fee for pro rata recovery of development costs. The amount of cost recovery is decided during negotiation of a Foreign Military Sales case and may be waived.

Figure 3.2: US Foreign Military Sales to Australia, 2000–01 to 2014–15

Source: Department of Defence.

3.6 The 2012 Senate Committee inquiry considered the issue of T&E in the context of OTS acquisitions at length49, and made a recommendation with regard to the use of preview T&E.50

3.7 In this chapter, the ANAO examines Defence’s:

- progress in implementing the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendations; and

- approach to preview T&E for three OTS equipment acquisitions.

Has Defence fully implemented the 2012 Senate Committee’s recommendation to mandate preview test and evaluation?

Defence has implemented the 2012 Senate Inquiry recommendation that it mandate a default position of engaging specialist T&E personnel prior to seeking First Pass government approval for acquisition options to proceed into detailed analysis.

When implemented well, Defence preview T&E has mitigated acquisition risks, particularly with respect to OTS equipment acquisitions. OTS defence equipment acquisitions are not risk free and acquisition risks still need to be managed through the conduct of preview T&E and operational T&E.

The mixed experience with the MRH90 helicopter acquisition and other recent OTS acquisitions, such as Land 121 (medium and heavy vehicle fleet) and Land 125 (F88 Steyr rifle), underscore the importance of OTS equipment being subjected to T&E sufficient to allow the mitigation of cost, schedule and capability risks.

3.8 The 2012 Senate Inquiry expressed concern about Defence projects experiencing ‘very serious problems’, and attributed the cause in part to risks not being managed properly.51 The Senate Inquiry recommend that Defence:

… mandate a default position of engaging specialist T&E personnel pre-First Pass, during the project and on acceptance in order to stay abreast of potential or realised risk and subsequent management. This requirement was also to apply to military off-the-shelf/commercial off-the-shelf (MOTS/COTS) acquisition.52

3.9 To give effect to this recommendation, Defence has mandated the conduct of preview T&E and relies on its technical regulatory systems to ensure adequate T&E is performed throughout the Defence capability life cycle (see Figure 1.1). The DCDM makes the Director General T&E responsible for determining compliance with preview T&E policy, as each Defence Capability Plan submission progresses through its First and Second Pass approval processes. ADTEO is responsible for reporting to the Chief of CDG any non-conformance with preview T&E policy.

3.10 From the overall capability life cycle perspective, Defence’s technical regulations require equipment suppliers to conduct sufficient T&E to enable their products to be certified as complying with specified standards and to be technically fit for service in their intended role. Design acceptance organisations such as DMO (now CASG), are required to certify they have validated the design by proving, by examination of designers’ claims and supporting evidence, that the specified end-use of a product or system has been accomplished in its intended environment. Technical Regulatory Authorities may conduct compliance assurance audits that review the evidence supporting design certification and confirm that recognised organisations were employing sound processes within their engineering and quality systems.

Test and evaluation for off-the-shelf equipment

3.11 As noted, OTS acquisitions are products that have already been delivered to another military, government body or commercial firm. Consequently, OTS acquisitions may, in systems engineering terms, progress directly from the Requirements Definition Phase to System Acceptance as developmental and acceptance T&E will have already been completed by the originating source. However, acquisition risks and issues still need to be managed through the conduct of preview T&E and operational T&E to validate an acquisition’s ability to meet Defence requirements and its ability to integrate with Defence’s Fundamental Inputs to Capability.53 Technical and reliability deficiencies experienced by OTS equipment have required Defence to make ad hoc changes to equipment designs, and to adjust operational tactics, techniques and procedures. This has resulted in significant delays in achieving required Final Operational Capability.

3.12 ADTEO has reported that recent acquisitions of OTS equipment, including some deployed directly into military operations, experienced significant unanticipated operational limitations. That outcome may stem from OTS items being specifically designed for their country of origin with design features that rely on a different set of Fundamental Inputs to Capability. These differences have affected the equipment’s ability to satisfy Defence’s operational needs.

MRH90 Helicopter