Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Tax Avoidance Taskforce — Meeting Budget Commitments

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- In the 2016–17 Budget, the ATO received $679 million over four years to establish and run the Tax Avoidance Taskforce.

- The Taskforce builds on the ATO's existing work to help make sure taxpayers comply with the law and pay the correct amount of tax.

- Entities that receive additional funding to expand or enhance their existing work should be able to demonstrate how they achieve that.

Key facts

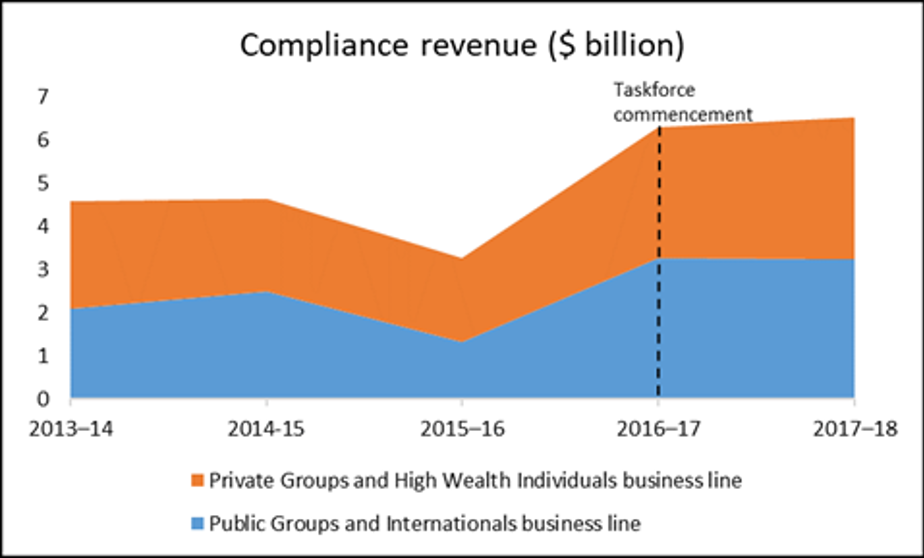

- Compliance revenue increased significantly since the commencement of the Taskforce.

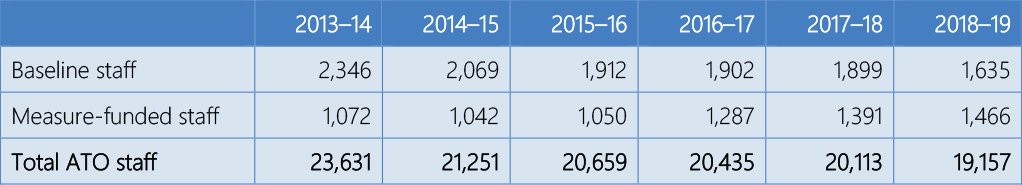

- Measure-funded staff numbers increased while baseline staff numbers declined.

What did we find?

- Taskforce-funded positions were integrated into existing business service lines, but the ATO lacked a comprehensive methodology to attribute resources between the Taskforce and other areas.

- The ATO's approach of attributing revenue using a percentage of total resourcing does not necessarily provide an accurate indication of Taskforce output.

- There has been a substantial increase in compliance revenue over the life of the Taskforce, but it is not clear the extent to which this is a result of additional Taskforce activity.

What did we recommend?

- We made two recommendations about the way the ATO develops funding proposals and how it evaluates their results.

- The ATO agreed to one recommendation in full, and one recommendation in part.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) administers the tax and superannuation systems that support and fund services to Australians. As part of its ongoing operations to ensure that all taxpayers pay the correct amount of tax, the ATO undertakes risk and compliance activities. These activities may be undertaken either as part of business-as-usual activities or through separately funded Budget measures.

2. In the 2016–17 Budget, the ATO was provided $679 million over four years from 1 July 2016 to enhance its compliance activities through the establishment and operation of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce (the Taskforce). The funding was intended to increase the resources available to the ATO for compliance activities focused on multinational companies, large groups and high-wealth individuals. The Taskforce was forecast to raise an additional $3.7 billion in tax liabilities1 while also providing other benefits, such as deterring taxpayers from future tax avoidance.

3. There is no standalone Tax Avoidance Taskforce business unit or work stream within the ATO. At the commencement of the Taskforce, the ATO decided not to divide its casework or people into Taskforce and non-Taskforce groups. Some of the Taskforce work streams were extensions of existing programs which were already funded to the end of 2016–17 and received continued funding through the Taskforce from 2017–18, while others were new programs2 funded from 2016–17.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The ATO receives ongoing funding to undertake its core departmental functions, including monitoring and enforcing compliance with Australia’s taxation system. The ATO also receives substantial additional funding through specific Budget measures. The decision to provide this additional funding is based on an estimate of the likely cost and benefit to the government, which is set out in the corresponding Budget measure. Entities that receive funding through Budget measures should be able to demonstrate their performance against these estimates.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the ATO’s effectiveness in meeting its revenue and resourcing commitments for the Taskforce. The high level criteria were:

- Has the ATO resourced the Tax Avoidance Taskforce in accordance with Budget estimates?

- Has the Tax Avoidance Taskforce performed in accordance with Budget estimates?

Conclusion

6. While there has been a significant increase in compliance revenue over the life of the Taskforce, it is not clear the extent to which this is a result of Budget measure resources provided for the Taskforce. This is because the ATO’s approach of attributing revenue using a percentage of total resourcing did not necessarily provide an accurate indication of Taskforce revenue. The ATO also had not implemented a methodology that accurately monitored Taskforce resourcing. The ATO therefore cannot conclusively demonstrate that the Tax Avoidance Taskforce has met the revenue and resourcing commitments set out in the 2016–17 Budget.

7. The ATO had not implemented a methodology to clearly demonstrate that the Taskforce had been resourced in accordance with Budget estimates. The ATO recruited staff for the Taskforce broadly in line with Budget estimates. At the same time, there was an overall reduction in business-as-usual staffing in the relevant business lines.

8. There has been a significant increase in revenue raised by the ATO’s relevant business lines since the commencement of the Taskforce. With the assistance of Taskforce funding, the business lines have increased both the liabilities raised and cash collected from their compliance work. However, because the ATO had not implemented a methodology to clearly identify revenue arising from Taskforce activities, it is not clear exactly how much of this increased revenue is a direct result of the Taskforce. The Taskforce has provided benefits in addition to the revenue raised.

Supporting findings

Taskforce resourcing

9. The methodologies used by the ATO to develop resource estimates were appropriate except for documenting the bases of underlying assumptions, identifying estimates of baseline resources and including proposed measurement approaches. Documentation supporting the Taskforce extension and the black economy program was more detailed than for the earlier 2016–17 Taskforce measure.

10. The ATO had processes and practices in place to monitor and report Taskforce resourcing, but lacked a comprehensive methodology to attribute resources between the Taskforce and business-as-usual activities. The ATO endorsed an improved methodology in August 2019, but had not applied it at the time of the audit. The ATO advised that it intended to use the endorsed methodology in late 2019 to account for all Taskforce expenditure to date.

11. The lack of a comprehensive methodology to attribute resources to the Taskforce has meant that it is unclear whether overall resourcing has been consistent with Budget estimates. Analysis indicates that Taskforce staffing was broadly in line with Budget estimates while baseline resourcing declined.

Taskforce revenue

12. The structure of the models used by the ATO to estimate Taskforce revenue was appropriate and the calculations employed were sound. The models and supporting documentation did not include an explanation of the bases of the assumptions used or the approaches that would be used to monitor actual Taskforce revenue.

13. The ATO’s approach of attributing revenue using a percentage of total business service line budgeted resourcing does not necessarily provide an accurate indication of Taskforce output. Limiting factors include that compliance staff work on a mix of activities, budgeted resourcing may not match actual resourcing, and revenue from previous work was allocated to the Taskforce. The ATO has not reported revenue on the same basis as it was presented in the Budget measure — additional to existing revenue. Nevertheless, the ATO has implemented extensive monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Taskforce, including performance measures that link to corporate outcomes.

14. Overall revenue raised by the relevant business service lines has increased considerably since the commencement of the Taskforce in 2016–17, including raising $6.3 billion in liabilities that year and $6.5 billion in the following year, compared to $3.3 billion in 2015–16. The ATO attributed a considerable portion of this revenue to the Taskforce, reporting that it had raised $5.5 billion in the first two years — which was nearly 150 per cent of the total four-year Budget commitment of $3.7 billion. However, the accuracy of this attribution is questionable. Without accurate attribution or a baseline comparator, the exact amount raised by the Taskforce cannot be verified. The Taskforce has delivered other non-revenue benefits, including the implementation of new legal and administrative tools designed to address tax avoidance.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.37

In proposals for specific Budget funding of compliance activities, the Australian Taxation Office documents:

- the source and basis of each assumption used in the resourcing and revenue models;

- how it will monitor and report actual resourcing and revenue associated with the funding measure; and

- either the pre-existing levels of resourcing and revenue related to the measure, or why it is not feasible to provide these levels.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agree with (a); Disagree with (b) and (c).

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.41

The Australian Taxation Office develops a framework or set of principles to support accurate monitoring of actual costs and revenues of compliance measures, consistent with the measure’s proposals.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agree.

Summary of Australian Taxation Office response

15. The ATO’s summary response is provided below. A formal response and a letter to the Auditor-General are at Appendix 1.

The ATO welcomes the review of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce – Meeting Budget Commitments and in particular the confirmation of the success of the Government’s initiative, which is based on the collective efforts of the ATO and the determination, commitment and passion of our officers to address corporate tax avoidance.

The audit focused on whether the Taskforce has been resourced and performed in accordance with the Budget estimates.

There are significant complexities involved in relation to the management of large budget measures such as the Taskforce, particularly when government funding extends existing resources that have been in place for a very long period of time, increases ATO resources to expand existing programs and undertake new work programs. The Taskforce is an increase in ATO programs organised in a way to deliver the collective efforts of our existing and new staff.

There is a clear methodological difference of opinion between the ANAO and the ATO on how the ATO attributes results and expenses to government-funded initiatives, particularly large and integrated initiatives such as the Taskforce. The ANAO expressed a preference for a distinct separation of Taskforce funded positions and case work from existing ATO funded positions and case work. Whilst this approach might be appropriate for some specific funded measures, the same cannot be said for the Taskforce.

Since its inception in 2016, it has been clear that the Taskforce is not a separate program but a combination of effort across various business areas of the ATO to tackle tax avoidance. This initiative enhanced and extended existing compliance activities targeting large multinationals and high wealth individuals. The collective and integrated approach taken by the ATO is validated by the outstanding success of the initiative.

The ANAO also seems to prefer a “lock-in” of previous funding in business-as-usual activities “adjacent” to a government-funded initiative, perhaps with some allowance for efficiency dividends. While superficially attractive, this is not workable for a variety of reasons, including that it would restrict the ATO from flexibly allocating “base” resources to the best current use: what the ANAO is implicitly positing is that the government-funded initiative is effectively “grossed up” to include “adjacent” base funding and locking those funds away, or in other words an element of base funding is effectively “hypothecated” to an initiative for its term. In the ATO’s view, this would be a fundamental change to Government practices relating to new integrated initiatives.

This is made even more apparent when one considers the multitude of government-funded initiatives augmenting activities across the broad range of operations of the ATO – effectively this would limit the entire flexibility of the ATO (if indeed even possible to achieve given both explicit efficiency dividends and absorbed measures).

The ATO has been very clear from the start on the methodologies it would use in attributing revenue outcomes and expenditure for the Taskforce. The methodologies were built on the basis of the collective efforts across the office and are reviewed and updated annually to ensure they are appropriate and reflective of the funding levels and organisational structures each year.

There are some conclusions and findings in the report that the ATO does not agree with, and some instances where the ATO’s position is not reflected in the report. This is very misleading to a reader who does not have the full context of the specific issues raised and gives the impression the ATO has made certain decisions without careful consideration.

The ATO agrees with recommendation 1 in part. We agree with 1(a), in that we will continue to work on the documentation of the source and basis of assumptions used in our revenue and resourcing models for all new funding proposals. We disagree with 1(b) and 1(c). The ATO’s view is that our approach for developing Budget funding proposals is in line with Departments of Finance and Treasury requirements.

The ATO does not consider the business-as-usual or baseline is an essential starting point for revenue estimation or reporting methodologies. Firstly, given the cost associated with terminating programs it is not clear what baseline funding might have remained had the Taskforce not been announced. Secondly, the ATO needs to be able to respond to circumstances as they emerge and any attempt to lock in the application of baseline funding for the next four years is not in the best interests of the administration of the tax system.

ANAO comment on Australian Taxation Office response

16. The ANAO notes the ATO’s disagreement with the assessment of how it has attributed results and expenses for a Budget measure that provides additional funding to increase, expand or enhance existing activity. This reflects a difference in principle regarding the extent to which an entity should be accountable for delivering the additional level of activity agreed through the Budget measure funding.

17. The ANAO’s audit is based on the principle that where Budget measures are agreed to on the basis that they are additional to an existing level of funding and activity, it is necessary to know this baseline in order to demonstrate that additional outcomes have been achieved. The baseline should therefore be included in the Budget measure. The baseline activities should also be maintained unless there is Government approval to the contrary.

18. The ATO disagrees with this approach. The ATO advises that it ‘does not consider [that] business-as-usual or baseline is an essential starting point for revenue estimation or reporting methodologies’. The ATO considers that baseline funding needs to be able to be flexibly utilised, and that ‘any attempt to lock in the application of baseline funding for the next four years is not in the best interests of the administration of the tax system’.

19. The ANAO has undertaken this audit on the principle that Budget measures designed to increase, expand or enhance existing activity are intended to add to the existing baseline, for the benefit of Government and citizens. The same view has been taken in the three previous audits undertaken of Budget measure implementation.3 Without this comparator, the relative success of budget measure objectives cannot be determined.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Accountability and transparency in Budget measures

1. Background

Tax Avoidance Taskforce

1.1 The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) administers the tax and superannuation systems that support and fund services to Australians. As part of its ongoing operations to ensure that all taxpayers pay the correct amount of tax, the ATO undertakes risk and compliance activities. These activities may be undertaken either as part of business-as-usual (BAU) activities or through separately funded Budget measures.

1.2 In the 2016–17 Budget, the ATO was provided $679 million over four years to enhance its compliance activities through the establishment and operation of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce (the Taskforce). The funding was intended to increase the resources available to the ATO for compliance activities focused on multinational companies, large groups and high-wealth individuals. The Taskforce was forecast to raise an additional $3.7 billion in tax liabilities while also deterring taxpayers from future tax avoidance (see Table 1.1). A Budget factsheet on the Taskforce described the measure as providing ‘significant new resources to … secure more revenue’.

Table 1.1: Tax Avoidance Taskforce — 2016–17 Budget estimates ($ million)

|

Item |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Total |

|

Revenue |

77.4 |

767.7 |

1283.8 |

1610.0 |

3738.9 |

|

Expenses |

48.8 |

203.3 |

212.6 |

214.2 |

678.9 |

Source: Budget measure — ‘Tax Integrity Package — establishing the Tax Avoidance Taskforce’.

1.3 The Taskforce commenced operation in July 2016. Its stated objectives are to:

- detect tax avoidance to protect revenue and maintain the integrity of the tax system;

- increase transparency and develop a better understanding of commercial drivers and the industries in which taxpayers operate;

- improve the ATO’s data, analytics, risk and intelligence capabilities to identify and manage tax avoidance risk; and

- provide the community with confidence that large public and private groups and wealthy individuals are paying the right amount of tax, according to Australian law.

1.4 The Taskforce consists of key compliance and enforcement programs across different work streams within the Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals4 and Public Groups and International business areas of the ATO. There is no standalone Tax Avoidance Taskforce business unit or work stream (although there is a dedicated Taskforce program management office, consisting of six staff, to co-ordinate monitoring and reporting of Taskforce performance). The ATO advised that a deliberate decision was taken not to divide casework or staff into Taskforce and non-Taskforce groups. This was intended to foster greater collaboration and efficiency across teams and ensure consistency in program expectations and incentives.

1.5 Some Taskforce work streams were extensions of existing programs that were already funded to the end of 2016–17 and received continued funding through the Taskforce from 2017–18, while others were new (or additional) programs5 funded from 2016–17. The key work programs are shown below, with more descriptions at Appendix 2.

- Extending programs:

- international risks program; and

- private groups and wealthy Australians, including high wealth individuals, trusts and promoters.

- Additional programs:

- the top 1000 multinationals and public companies tax performance program;

- the top 320 private groups tax performance program;

- multinational anti-avoidance law (MAAL) implementation;

- diverted profits tax implementation; and

- base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) action plan implementation.

1.6 In the 2019–20 Budget, the ATO received a further $1 billion to extend and expand the Taskforce until the end of the 2022–23 financial year.

Rationale for undertaking the audit and previous audit coverage

Rationale for the audit

1.7 The ATO receives ongoing funding to undertake its core departmental functions, including monitoring and enforcing compliance with Australia’s taxation system. The ATO also receives substantial additional funding through specific Budget measures. The decision to provide this additional funding is based on an estimate of the likely cost and benefit to the government, which is set out in the corresponding Budget measure. Entities that receive funding through Budget measures should be able to demonstrate their performance against these estimates.

Previous audit coverage

1.8 Auditor-General Report No. 15 of 2016–17, Meeting Revenue Commitments from Compliance Measures, examined the ATO’s effectiveness in achieving revenue commitments established under 16 Budget-funded compliance measures. The report identified weaknesses in processes used to estimate likely revenues and costs and to monitor actual revenues and costs.

1.9 The ATO disagreed with the ANAO’s conclusions and recommendations from that audit in important respects, such as the need to develop baselines. Nevertheless, the ATO has expended effort to strengthen its approaches (governance and methodologies) in monitoring expenses and revenues for the Tax Avoidance Taskforce. Chapters 2 and 3 of this audit report examine these approaches.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.10 The objective of the audit was to assess the ATO’s effectiveness in meeting its revenue and resourcing commitments for the Taskforce. The high level criteria were:

- Has the ATO resourced the Tax Avoidance Taskforce in accordance with Budget estimates?

- Has the Tax Avoidance Taskforce performed in accordance with Budget estimates?

1.11 The audit examined the estimated and actual revenue attributed to the Taskforce since its establishment in July 2016, as well as the estimated and actual Taskforce expenditures. This included a detailed examination of the methodologies used to develop Budget estimates and to calculate actual revenues and expenditures. The audit assessed both the establishment of the Taskforce in the 2016–17 Budget and the extension of the Taskforce in the 2019–20 Budget. Assessment of actual revenue and expenditure focused on 2017–18, which was the first year that all components of the Taskforce were funded by the Budget measure. To provide additional assurance on the ATO’s methodologies, the audit also covered a 2018–19 Budget measure that provided the ATO with $311.8 million over four years to expand and enhance its existing activities to combat the black economy.6

Audit methodology

1.12 The audit methodology included:

- review of advice and briefing material provided to government as part of the Budget process;

- examination of expenditure and revenue estimates prepared by the ATO, the Department of Finance and the Treasury;

- analysis of ATO expenditure and revenue records, including compliance case data;

- examination of internal ATO reporting; and

- discussions with key ATO staff.

1.13 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $275,000.

1.14 The team members for this audit were Chiara Edwards, Chay Kulatunge, Evanka Spasojevic, John McWilliam, Peter Hoefer, Tracy Cussen and Andrew Morris.

2. Taskforce resourcing

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO’s) processes to estimate and monitor resourcing for the Tax Avoidance Taskforce (the Taskforce), in order to determine whether it had resourced the Taskforce in accordance with Budget estimates.

Conclusion

The ATO had not implemented a methodology to clearly demonstrate that the Taskforce had been resourced in accordance with Budget estimates. The ATO recruited staff for the Taskforce broadly in line with Budget estimates. At the same time, there was an overall reduction in business-as-usual staffing in the relevant business lines.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO suggested that the ATO establishes a framework for developing revenue compliance measures (paragraph 2.27), and provides information on resourcing in annual Taskforce outcome reports (paragraph 2.33).

Did the ATO use an appropriate methodology to develop resource estimates for the Tax Avoidance Taskforce?

The methodologies used by the ATO to develop resource estimates were appropriate except for documenting the bases of underlying assumptions, identifying estimates of baseline resources and including proposed measurement approaches. Documentation supporting the Taskforce extension and the black economy program was more detailed than for the earlier 2016–17 Taskforce measure.

2.1 New policy proposals with financial impacts are considered in the annual Budget process. Portfolio entities provide advice to government on the expected costs and benefits of these proposals. There are a range of tools to assist in preparing this advice, including standard templates and review by the Department of Finance (Finance) and the Treasury.

2.2 The ATO used the standard Finance template for Budget measure costing. The total Taskforce estimate of some 1300 full time equivalent (FTE) staff was the aggregate of the expected business needs of each specific work area within the Taskforce.7 Taskforce resourcing (staffing levels and total expenses) was reviewed and amended by Finance following its examination of the templates, and subsequently approved by Government. The approved estimates by business service line for the 2016–17 measure are shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Tax Avoidance Taskforce — staffing (FTE) and expenses by business service line approved in the 2016–17 Budget

|

|

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Total |

||||

|

Business line |

FTE |

($m) |

FTE |

($m) |

FTE |

($m) |

FTE |

($m) |

($m) |

|

Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals |

70 |

9.3 |

663 |

83.3 |

663 |

83.7 |

663 |

84.4 |

260.7 |

|

Public Groups and International |

178 |

33.1 |

589 |

87.5 |

639 |

95.0 |

639 |

95.7 |

311.3 |

|

Enterprise Solutions and Technology |

– |

– |

– |

0.1 |

– |

0.1 |

– |

0.1 |

0.4 |

|

Review and Dispute Resolution |

5 |

0.8 |

12 |

1.8 |

12 |

1.8 |

12 |

1.8 |

6.2 |

|

Tax Counsel Network |

– |

– |

6 |

1.0 |

6 |

1.1 |

6 |

1.1 |

3.2 |

|

Debt |

– |

– |

6 |

0.9 |

6 |

0.9 |

6 |

0.9 |

2.7 |

|

Overheads |

– |

5.6 |

– |

28.7 |

– |

30.0 |

– |

30.2 |

94.4 |

|

Total |

253 |

48.8 |

1,277 |

203.3 |

1,327 |

212.5 |

1,327 |

214.2 |

678.8 |

Source: ATO.

2.3 The approved FTE by extending and additional programs by business line are shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Tax Avoidance Taskforce — staffing (FTE) for extending and additional programs in the 2016–17 Budget

|

Program category |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|

Extending programs |

– |

889.5 |

889.5 |

889.5 |

|

Additional programs |

253.0 |

387.0 |

437.0 |

437.0 |

|

Total |

253.0 |

1,276.5 |

1,326.5 |

1,326.5 |

Source: ATO.

2.4 The audit examined the ATO’s approaches in preparing resource estimates for the establishment of the Taskforce in the 2016–17 Budget and its extension in the 2019–20 Budget. The audit also considered the black economy program measure in the Budget.8

2.5 Resource estimates for the establishment of the Taskforce reflected the specific staffing requirements of each business service line by classification level, based on documented assumptions relating to the nature and number of activities to be conducted, such as active compliance cases and contributions to law reform proposals, to address the specified tax population at risk. The resource estimates for the extension of the Taskforce and for the black economy program measure had similar approaches but contained greater detail, including information on past performance and better explanation of overarching program strategies.

2.6 There remains scope for further improvement in the preparation of resource estimates. In particular, the ATO could have:

- thoroughly documented the bases of the assumptions used in its cost models, including any underlying evidence; and

- included estimates of the baseline resources employed at the commencement of the measure to provide transparency over the actual change in compliance resources resulting from the measure.

Documenting the basis for assumptions

2.7 Financial models necessarily use assumptions about what will occur in the future. The reliability of a model depends, in part, on the suitability and robustness of these underlying assumptions. All assumptions used in developing costings should be clearly outlined and explained in full in the model or associated documents.

2.8 While the ATO’s resource models and other documents for both the establishment and the extension of the Taskforce identified the assumptions made, they did not provide evidence of the basis for those assumptions, such as data from past performance or comparable population groups. The models should have documented why certain values (such as the number of compliance cases expected to be completed by one FTE) were chosen, as these assumptions had significant impact on the estimates of resources required to achieve the revenue and other benefits anticipated from the Taskforce.

2.9 The ATO noted that the 2016–17 Budget measure included a significant rollover of previously funded resources9 and it had limited opportunity to review and revise the resource estimates to ensure they were a more accurate reflection of current business line structures. The necessary detail included information about the effort that was required in the previous and current environment at the time (that is, the number of cases expected to be completed) and on the same population groups. The ATO advised that Finance did not request any additional information about the rollover. Nevertheless, the ATO could have outlined the bases of the key assumptions made, even if they related to periods a number of years prior to the proposed new measure.

2.10 The ATO agreed to Recommendation 1(b) of Auditor-General Report No. 15 of 2016–17, Meeting Revenue Commitments from Compliance Measures, to specify in revenue models for Budget measures the assumptions used and the basis of those assumptions, including data sources.10 However, the ATO had not done this in models for the extension of the Taskforce in the 2019–20 Budget and for the black economy program in the 2018–19 Budget.

Including estimates of baseline resources

2.11 Including baseline resources can provide a complete picture of the impact of Budget measures on the ATO’s overall compliance activity and provide assurance that additional revenue commitments will be met. New policy proposals that clearly identify total resources (and total projected revenue) from Budget measure and business-as-usual (BAU) activity at the commencement of the measure support transparency and accountability about the overall change in compliance resources (and revenues) over time as a result of the measure.

2.12 For the establishment of the Taskforce, the ATO’s justification statements and models distinguished between resources for both extending and additional programs, indicating the total resources required for the Taskforce to meet its objectives. However, the justification statements and models did not identify either a baseline level of resourcing or the resourcing that would eventuate if the Budget measure did not go ahead. The statements and models also did not outline the level of total resourcing in the Public Groups and International (PGI) and Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals (PGH) business lines including the measure funding, to provide an indication of the overall resourcing and importance of the Taskforce within those business lines.

2.13 Auditor-General Report No. 15 of 2016–17 recommended that the ATO document in its funding proposals how the additional revenue from a measure will be determined and any pre-existing level of activity related to the compliance risks addressed by the measure. The ATO disagreed with this recommendation.11

2.14 In response to this current audit, the ATO has advised it continues to disagree with the recommendation. With respect to the Taskforce, which was extending many activities, the ATO advised that:

Measuring the impact of a loss of funding is not simply a matter of deducting the loss and leaving an identifiable base. In calculating the situation an administrator would face, consideration needs to be given to related costs and delays in reducing ongoing staff which were previously funded by the terminating measure. This impacts the amount of base funding available and leads to very complex calculations for certain outcomes. The ANAO needs to recognise it is impossible to undertake such complex calculations in the very short timeframe (as required by Government) for an agency to construct a new funding proposal. Hence, due to the complexities in determining or maintaining a baseline, the ATO remains of the view that specifying a baseline is flawed.

2.15 As discussed in the following section of this report, there is considerable integration of Taskforce and BAU activities, with associated issues for the ATO in accurately apportioning resources and revenue between Taskforce and base activities. This creates issues for the ATO in accurately measuring resourcing and revenue of the Taskforce. Outlining intended measurement approaches, and acknowledging any inherent challenges (including in establishing meaningful baselines), would provide a stronger basis for examination of new policy proposals by Finance and the Treasury, and for funding decisions by government.

2.16 Where entities seek funding for measures to expand or increase activity above existing levels, they should clearly identify the expected level of baseline resourcing for the duration of the measure. This provides transparency about the additional activities and promotes accountability for the delivery of Budget measure outcomes.

2.17 Auditor-General Report No. 41 of 2016–17 noted that ‘it is not consistent with the basis of the funding agreed by Government during the Budget to attribute [additional] compliance activities to a measure where the agreed volume of business-as-usual activities has not been maintained’.12 This view was consistent with advice provided to the ANAO by the Department of Finance in relation to new policy proposals.13

Does the ATO have sound processes and practices in place to attribute, monitor and report actual Tax Avoidance Taskforce resources?

The ATO had processes and practices in place to monitor and report Taskforce resourcing, but lacked a comprehensive methodology to attribute resources between the Taskforce and business-as-usual activities. The ATO endorsed an improved methodology in August 2019, but had not applied it at the time of the audit. The ATO advised that it intended to use the endorsed methodology in late 2019 to account for all Taskforce expenditure to date.

Issues in attributing actual Taskforce resourcing and expenses

2.18 The ATO identified actual Taskforce resourcing in 2016–17 and 2017–18 for the additional programs in PGI based on the teams in which staff were working. The ATO advised that many areas in PGI and PGH have integrated teams of staff that do a mix of work — both Taskforce and base – in order to manage tax affairs and risks in a holistic way.14 This integration particularly affects existing activities that were extended and rolled into the Taskforce from 2017–18.

2.19 The ATO advised it was not possible to identify actual staff funded by the extending programs given the nature of integration of teams between Taskforce and base.15 Together with the decision not to distinguish cases or activities between Taskforce and base (see Footnote 15), this meant the ATO was unable to identify resources as Taskforce or base for these programs. Consequently, the ATO needed to develop a proxy approach for measuring the actual Taskforce resourcing (and outcomes) for these programs.

The ATO’s attribution of actual Taskforce resourcing and expenses

2.20 In addressing the issues outlined above, the ATO has taken various approaches in attributing actual Taskforce resourcing, as shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: The ATO’s approaches to estimating Taskforce staffing expenses, 2016–17 to 2018–19

|

Year |

ATO approach |

|

2016–17 |

Public Groups and International business service line Actual taskforce staff were identified by either being in a dedicated Taskforce cost centre or as Taskforce resources in general cost centres for specific organisational units. This approach was in the context of all cases being under additional programs. Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals business service line The cost of the additional 40 FTE staff working on the compliance activities was determined on a pro-rata basis. |

|

2017–18 |

Taskforce status reports provided results only for the budgeted 387 FTE staff for additional programs (270 for PGI and 117 for other business service lines). This limited approach was in place pending endorsement (expected in 2018–19) of a methodology to determine the measurement of costs associated with staffing the extending programs (889.5 budgeted FTE staff as per Table 2.2). |

|

2018–19 |

An endorsed methodology was not in place. Instead, Taskforce status reports included the number of budgeted FTE staff for PGH, and actual FTE staff for PGI, for the additional element and applying a pre-determined ratio based on extending funding compared to non-NPP funding for the remainder of the resources. The methodology endorsed on 1 August 2019 is expected to be applied in 2018–19 end of year reporting. |

Source: ATO.

2.21 Table 2.3 shows that for the first three years of the Taskforce the ATO did not have an endorsed comprehensive methodology to monitor and report Taskforce resources, notwithstanding that many activities had been conducted for numerous years.

2.22 On 1 August 2019, the ATO’s Tax Avoidance Taskforce Leadership Group endorsed a methodology for attributing Taskforce and base expenditure attribution. The methodology uses direct tracking of expenses where possible and apportionment for the balance. In particular, the methodology includes:

- direct attribution for FTE staff and supplier expenses in the additional funding where there are specific cost centres or organisational units set up to capture direct expenses;

- apportioned FTE staff attribution based on budgeted FTE staff for those staff that are not identifiable in the specific Taskforce cost centres or organisational units as they are part of integrated teams comprising Taskforce and base funded positions and delivering a combination of Taskforce and base outcomes; and

- supplier expenses mainly based on apportioned FTE staff as case officers are usually the drivers of this expenditure.16

The combination of these techniques allows for a more detailed and accurate assessment of Taskforce expenditure than apportionment alone.

2.23 As indicated in Table 2.3, the ATO advised that it would apply the new endorsed methodology in developing the June 2019 Taskforce Status report. The ATO also advised that it would undertake what it described as a ‘wash-up exercise’ in late 2019, using the endorsed methodology to account for all Taskforce expenditure to date. The endorsed methodology will also be applied, as appropriate, across all years of the Taskforce in a closure report for the initial measure, which ends in 2019–20. The closure report is to compare budgeted to actual resourcing, expenses and revenue for the Taskforce.

2.24 While the endorsed methodology is an improvement over costing approaches previously applied for 2017–18 and 2018–19, it still involves apportionment for a considerable (not yet known) proportion of funding for the Taskforce on the basis of budgeted FTE staff. Apportionment will affect the accuracy of the reported actual expenditures, depending on the:

- proportion of Taskforce resourcing and expenses that will be apportioned;

- extent to which actual FTE staff numbers match budgeted FTE staff numbers each year for the apportioned extending programs; and

- extent to which supplier expenses are related to the proportion of budgeted FTE.

2.25 With regard to the proportion of Taskforce resourcing and expenses apportioned, the ATO advised that under the extended Taskforce, PGH is moving to a model similar to PGI; with separate Taskforce cost centres to track expenditure and increase transparency and control. This is progress compared to the commencement of the Taskforce, and highlights the importance of the ATO using specific cost centres (or Taskforce case codes17) wherever practicable for Taskforce activities to reduce the extent of apportionment. Any steps the ATO can take in the near term to reduce the extent of apportionment will support more accurate measurement and reporting of actual expenses on the initial phase of the Taskforce.

2.26 The ATO also advised that the level of integration of activities between Taskforce and base has meant that it has not been practicable to compare actual with budgeted FTE for the extending programs at the end of each year. If this remains the situation, there will be an unknown but possibly substantial level of inaccuracy in the measurement of actual expenses for the Taskforce. This highlights the importance of the ATO recognising, and documenting in funding proposals, possible limitations in accurately measuring the use of resources18 in Budget measures, to better support government funding decisions.

2.27 There would also be value in the ATO establishing a framework that could be used to support reliable and consistent attribution of the actual costs (and revenues) of compliance measures. Without prescribing any particular methodology, the framework could codify principles of good practice, such as:

- developing a measurement methodology prior to the commencement of a new Budget measure;

- clearly defining a baseline level of expenses and outcomes;

- using direct attribution wherever possible; and

- using actual (rather than budgeted, historical or averaged) figures.

2.28 A principles-based framework would need to be supported by the ATO’s corporate systems.

Supplier expenses

2.29 The challenges in attributing staff resourcing expenses to the Taskforce are common to other expenses (generally known as supplier expenses, which include consultants, contractors and legal advisers), and the ATO has used a mix of direct attribution and apportionment to account for these costs. From 1 August 2019, the ATO’s endorsed approach to measuring actual supplier costs is:

- In PGI, supplier costs associated with additional programs are attributed directly to the relevant area, using dedicated cost centres and organisational units. Supplier costs for extended programs are apportioned based on the number of Taskforce-funded FTE staff.

- In PGH, supplier expenses are pooled. Costs are apportioned based on the number of Taskforce-funded FTE staff, although direct attribution is used for large items where possible.19

Monitoring and reporting actual Taskforce resourcing

2.30 Ongoing monitoring and reporting of Taskforce resourcing and expenses has largely been through monthly Taskforce status reports. These have been prepared by the Taskforce program management office for the Taskforce Leadership Group. The program management office receives input from all Taskforce program areas as well as the ATO’s corporate area.

2.31 These status reports focus mainly on Taskforce activity and outcomes, but also contain a section on Taskforce expenditure that sets out FTE staff numbers, labour costs and legal expenditure. These figures are presented as year to date, projected year end and, where applicable, for the relevant month. The section also includes commentary about trends, risks and emerging issues in Taskforce resourcing.

2.32 The reporting is consistent and comprehensive, but its accuracy was affected by shortcomings in the underlying methodology.

2.33 The ATO has produced annual reports against outcomes for the each year of the Taskforce so far (see paragraphs 3.21 and 3.22 for further discussion). These reports do not include information about Taskforce resourcing. While resourcing is not a compliance outcome, it is affected by the Budget measure and forms part of the ATO’s commitment to government. To provide greater transparency around whether it has met this commitment, the ATO should include information on resourcing (including staffing and expenses) in annual outcomes reports.

Is Taskforce resourcing to date consistent with Budget estimates?

The lack of a comprehensive methodology to attribute resources to the Taskforce has meant that it is unclear whether overall resourcing has been consistent with Budget estimates. Analysis indicates that Taskforce staffing was broadly in line with Budget estimates while baseline resourcing declined.

2.34 As noted previously, the ATO only recently adopted a comprehensive methodology for attributing Taskforce expenses, and there have been limitations in the approaches to measuring actual Taskforce expenses to date.20 Accurate, comparable estimates of resource usage across the life of the Taskforce are therefore not available.

2.35 While recognising these limitations and the different approaches used by the ATO to attribute costs across the life of the Taskforce, monthly internal Taskforce status reports have indicated that:

- in 2016–17:

- in 2017–18:

- total Taskforce staff utilisation for additional programs was 61 FTE short of the original full year 387 FTE (staff for the extending programs was not reported).23

2.36 These reports suggest that the ATO did not fully resource the Taskforce compared to Budget estimates over the course of 2016–17 and 2017–18 for the additional programs in PGI, but was close to those budgeted resourcing levels at the end of each year.

2.37 Taskforce status reports and internal recruitment documentation indicated increases in Taskforce staffing. These reports stated that by 30 June 2018 the Taskforce had filled 347 additional (new) positions against a target of 387. By 4 April 2019, reports indicated the Taskforce had placed a total of 434.8 FTE in additional Taskforce positions, representing 99.5 per cent of the target of 437 FTE.

Overall resourcing across PGI and PGH

2.38 Given the absence of a robust methodology in costing Taskforce activities, the ANAO also analysed overall resourcing across PGI and PGH from 2013–14 to 2018–19, which can be divided into two categories: resourcing for Budget measures (including the Taskforce, black economy program and others), and resourcing for base or BAU activity.

2.39 Information provided by the ATO shows that the number of FTE staff undertaking business-as-usual activities across PGI and PGH has declined in recent years (see Table 2.4). This is in the context of declining total staffing between 2013–14 and 2018–19, and increasing staffing attributed to Budget measures.

Table 2.4: Business-as-usual and Budget measure related staff 2013–14 to 2018–19

|

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

Total business-as-usual staff |

2,346 |

2,069 |

1,912 |

1,902 |

1,899 |

1,635 |

|

Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals |

1412 |

1248 |

1162 |

1185 |

1151 |

959 |

|

Public Groups and International |

934 |

821 |

750 |

717 |

748 |

676 |

|

Total measure-related staffa |

1,072 |

1,042 |

1,050 |

1,287 |

1,391 |

1,466 |

|

Private Groups and High-wealth Individualsb |

732 |

702 |

647 |

680 |

747 |

756 |

|

Taskforce measure – extending |

– |

– |

– |

– |

512 |

512 |

|

Taskforce measure – additional |

– |

– |

– |

40 |

80 |

80 |

|

Public Groups and International |

340 |

340 |

403 |

607 |

644 |

710 |

|

Taskforce measure – extending |

– |

– |

– |

– |

347 |

347 |

|

Taskforce measure – additional |

– |

– |

– |

178 |

242 |

292 |

|

Total BAU and measure-related staff |

3,418 |

3,110 |

2,962 |

3,189 |

3,290 |

3,101 |

|

Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals |

2,144 |

1,950 |

1,809 |

1,865 |

1,898 |

1,715 |

|

Public Groups and International |

1,274 |

1,161 |

1,153 |

1,324 |

1,392 |

1,386 |

|

Total ATO staffc |

23,631 |

21,251 |

20,659 |

20,435 |

20,113 |

19,157 |

Note a: Measure-related staff includes all Budget measures.

Note b: PGH was formed in 2015–16 from a combination of existing business lines.

Note c: Total employee headcount including ongoing, non-ongoing and casual positions.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

2.40 This analysis suggests that the ATO has been prioritising the staffing of Budget measure activities in PGI and PGH, with staffing of BAU activities across the two business lines being reduced. However, the analysis does not clearly indicate whether actual staffing of Budget measures met Budget commitments.

2.41 From 2015–16 (the year prior to the Taskforce’s commencement) to 2018–19, total ATO staffing declined by approximately seven per cent. PGI and PGH BAU staffing declined at double this rate, falling by approximately 14 per cent over the same period.

2.42 With respect to changes in baseline funding, the ATO advised that its BAU compliance activity changes as the tax and superannuation administrative processes, compliance risks and priorities evolve; these changes impact the way in which the ATO prioritises baseline resources.24 Factors that can influence baseline resourcing include efficiency dividends, other government savings, changing technology demands, and increases in data and analytics costs.

Resourcing in line with funding decisions

2.43 In its initial consultation with Finance, the ATO sought funding of approximately $11 million per year for two ancillary programs (Smarter Data and the Tax Counsel Network). Following Finance’s review, this was amended to $1 million per year in the final submission. The ATO subsequently reallocated Taskforce funding back to the ancillary programs as follows:

- $6.0 million in 2017–18; and

- $3.8 million in 2018–19.

2.44 The ATO advised that these resourcing decisions reflected what it considered to be the strategic importance of these activities to the overall success of the Taskforce. The ATO also questioned whether it was obliged to allocate funding in accordance with the funding breakdown endorsed by Finance. The ATO’s view was that ‘the final decision of Government was for a sum of money, not for a sum of money broken down into constituent parts’. The ATO therefore considered that it had scope to allocate the funding to operational areas in ways that it considered most effective and efficient, regardless of the intended funding breakdown.

Measuring actual expenses for the black economy program

2.45 In relation to the black economy program, the ATO advised that there is no way to track effort against compliance work undertaken across the ATO. The ATO was not able to provide the number of FTE working on the program or what activities the program includes. However, the Black Economy Program Office has developed a methodology to estimate resourcing using average case completion times. The ATO has also established project codes to track black economy case work.

3. Taskforce revenue

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO’s) processes for estimating, monitoring and reporting on revenue for the Tax Avoidance Taskforce (the Taskforce), in order to determine whether it had performed in accordance with Budget estimates.

Conclusion

There has been a significant increase in revenue raised by the ATO’s relevant business lines since the commencement of the Taskforce. With the assistance of Taskforce funding, the business lines have increased both the liabilities raised and cash collected from their compliance work. However, because the ATO had not implemented a methodology to clearly identify revenue arising from Taskforce activities, it is not clear exactly how much of this increased revenue is a direct result of the Taskforce. The Taskforce has provided benefits in addition to the revenue raised.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at documenting assumptions and monitoring arrangements in funding proposals (paragraph 3.37), and developing a framework for monitoring actual costs and revenues of compliance measures (paragraph 3.41).

Did the ATO use an appropriate methodology to develop revenue estimates?

The structure of the models used by the ATO to estimate Taskforce revenue was appropriate and the calculations employed were sound. However, as noted for resourcing, the models and supporting documentation did not include an explanation of the bases of the assumptions used, or the approaches that would be used to monitor actual Taskforce revenue.

Revenue estimates for the 2016–17 Taskforce measure

3.1 For all new compliance measures, the ATO develops an estimate of the revenue that will be raised, which is then reviewed by the Treasury. The ATO estimated that the 2016–17 Taskforce measure would raise an additional $3.7 billion in tax liabilities over four years. This estimate can be broken down by source and population (summarised at Table 3.1), which illustrates:

- the breakdown of additional revenue from direct Taskforce activities (59 per cent over the life of the measure) and the indirect revenue (41 per cent) that was estimated to be raised as a result of greater taxpayer compliance from increased awareness of their obligations and the need to avoid investigation by the ATO;

- the amounts that were expected to be recovered from continuation (extending) of lapsing Budget measures (70 per cent over the life of the measure) and from additional compliance measures (30 per cent);

- the value of liabilities expected to be raised (that is, the revenue amounts that were included in the Budget measure) and the value expected to be collected.25 It was estimated that 59 per cent of liabilities would be collected over the life of the measure; and

- the components that relate to the compliance activities of each of the Private Groups and High-wealth Individuals (PGH) and Public Groups and International (PGI) business service lines.

Table 3.1: Tax Avoidance Taskforce — 2016–17 Budget revenue estimates

|

Item |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Total |

|||||

|

Liabilities ($m) |

77.4 |

767.7 |

1,283.8 |

1,610.0 |

3,738.9 |

|||||

|

Direct |

22.4 |

29% |

515.6 |

67% |

779.2 |

61% |

873.0 |

54% |

2,190.2 |

59% |

|

Indirect |

54.9 |

71% |

252.1 |

33% |

504.6 |

39% |

737.0 |

46% |

1,548.7 |

41% |

|

Extending |

0.0 |

0% |

554.1 |

72% |

930.1 |

72% |

1,141.9 |

71% |

2,626.0 |

70% |

|

Additional |

77.4 |

100% |

213.7 |

28% |

353.7 |

28% |

468.1 |

29% |

1,112.8 |

30% |

|

PGH |

26.2 |

34% |

421.3 |

55% |

638.2 |

50% |

746.2 |

46% |

1,831.8 |

49% |

|

PGI |

51.2 |

66% |

346.4 |

45% |

645.6 |

50% |

863.8 |

54% |

1,907.0 |

51% |

|

Collections ($m) |

8.1 |

250.1 |

728.4 |

1,204.0 |

2,190.6 |

|||||

|

Direct |

8.1 |

100% |

195.1 |

78% |

476.2 |

65% |

699.4 |

58% |

1,378.8 |

63% |

|

Indirect |

0.0 |

0% |

54.9 |

22% |

252.1 |

35% |

504.6 |

42% |

811.7 |

37% |

|

Extending |

0.0 |

0% |

165.0 |

66% |

513.5 |

70% |

853.1 |

71% |

1,531.6 |

70% |

|

Additional |

8.1 |

100% |

85.1 |

34% |

214.9 |

29% |

350.9 |

29% |

659.0 |

30% |

|

PGH |

8.1 |

100% |

131.1 |

52% |

400.0 |

55% |

624.0 |

52% |

1,163.1 |

53% |

|

PGI |

0.0 |

0% |

119.0 |

48% |

328.4 |

45% |

580.0 |

48% |

1,027.4 |

47% |

Note: Differences in totals are due to rounding.

Source: ATO.

3.2 The ‘FAST’ model was used to assess the technical adequacy of the revenue models.26 This standard uses four key principles — flexible, appropriate, structured and transparent — to provide guidance on the structure and design of efficient spreadsheet-based models. The ANAO’s assessment of the ATO’s models against these principles is shown at Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: The ANAO’s assessment of the 2016–17 ATO Taskforce revenue models against the FAST principles

|

FAST principle |

Description and ANAO comment |

ANAO assessment |

|

Flexible To be effective, the structure and style of models require flexibility for both immediate usage and the long term |

The ATO models can be used for multiple new policy proposals. |

Flexible |

|

Appropriate Models must reflect key business assumptions directly and faithfully without being cluttered in unnecessary detail |

The models used a number of assumptions to calculate the revenue estimates. These included FTE, direct return per direct FTE, direct return per ancillary FTE, indirect return, credit amendment rate, bad debt rate and cash collection. The tax segment populations used in the models did not correspond to the justification document and the revenue from extending programs was calculated in one tax population, rather than maintaining the populations of the existing measure. |

Partially appropriate |

|

Structured Rigorous consistency in layout and organisation is essential in retaining the model’s logical integrity over time |

Each model employed a consistent structure (business service line, populations, extending or additional and direct/indirect liabilities and collections). Gross liabilities were calculated and reduced for credit amendments to enable net accrual liabilities to be reported as revenue for the measure. These were further reduced for bad debts to calculate cash collections. Given the small size of the PGI model, it is unclear why two separate models were required. |

Structured |

|

Transparent Effective models are founded upon simple, clear formulas that can be understood by other modellers and non-modellers alike |

Each model had simple and clear formulas. However, the use of undocumented assumptions (and inconsistencies in the assumptions) reduced the ability of the models to be understood. For example, the model assumed, without explanation, that:

Penalties and interest were not separately calculated, reducing the transparency and robustness of the revenue calculations. The models did not include baseline data to enable accurate reporting of the additional level of revenue from the compliance activity following implementation of the measure. |

Not transparent |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO revenue models for the 2016–17 Taskforce measure.

3.3 The 2016–17 revenue models could have been improved by explaining the sources and bases of the assumptions used, and by including baseline data. Without explanation of the sources and bases of the assumptions used in the models, it is not possible to readily assess the appropriateness of methodologies used. Assumptions should be included in proposed measures to provide assurance that they are reasonably based. Similarly, there is merit in the ATO outlining the bases for estimated indirect revenue. While the ATO has developed organisation-wide methodologies for estimating indirect revenue, it would increase transparency to document how those methodologies have been applied in specific cases.

Distinguishing pre-measure and post-measure revenue

3.4 In proposing Budget measures where additional revenue is to be raised from funding additional compliance resourcing, the ATO should provide assurance in the justification documents and associated revenue models that it will be able to accurately monitor the additional revenue. In particular, the ATO should demonstrate that either:

- the revenue from the Budget measure can be accurately measured in its own right; or

- a meaningful baseline can be established showing pre-measure and post-measure revenue within a broader compliance program.

If neither of these can be done, then it is not possible to substantiate that the revenue is ‘additional’ and the measure should be proposed on another basis.

3.5 The revenue models for the Taskforce clearly distinguished revenue from extending activities and revenue from additional programs. However, the models and justification documents did not outline how revenue would be monitored. There would be merit in the ATO seeking input from Treasury and/or the Government in relation to how revenue will be monitored and measured.

3.6 The revenue models and related documents also did not provide a baseline of pre-measure and post-measure revenue. In relation to this, the ATO has restated its response to the previous ANAO audit, which was that it ‘is not always possible to meaningfully attribute revenue from business-as-usual (BAU) activities to risks or activities which could be aligned to proposed measures’.27

3.7 As discussed in Chapter 2, the ATO can and does redirect resources from baseline compliance activities to other competing priorities, and there is no assurance that all of the revenue from the measure is in addition to what would have been realised had the ATO maintained pre-existing base staffing levels. For this reason, the ATO should include in its new policy proposals estimates of expected revenue both with and without the measure if it cannot otherwise indicate how it will clearly monitor the additional revenue to be generated.

Changes in ATO revenue estimates in other funding proposals since 2016–17

3.8 To assess how the ATO’s processes have changed since 2016–17, the audit also examined the revenue models used for the extending of the Taskforce, announced in the 2019–20 Budget, and the black economy program measure in the 2018–19 Budget.

3.9 Auditor-General Report No. 15 of 2016–17 recommended that in developing compliance measures, the ATO:

- specifies in revenue models for the measures the assumptions used and the basis of those assumptions, including data sources (agreed by ATO); and

- includes revenue from penalties and interest in the revenue estimates where possible, and separately identifies penalties and interest when reporting outcomes (agreed by ATO).

3.10 The ATO separately identified revenue from penalties in some, but not all, revenue models since 2016–17. The ATO advised that revenue from penalties and interest is included only where it can be calculated with certainty. While it may not be possible to calculate the precise extent of taxpayers’ expected lateness and non-compliance, compliance revenue models should nonetheless incorporate some estimation of revenue from penalties and interest, as its value is significant28 and it is always included in revenue results.

3.11 Revenue estimates for the black economy program and the Taskforce extension did not include explanations of the assumptions used in the models. As noted in paragraph 2.7, the strength of a financial model is directly related to the reliability of its underlying assumptions.

3.12 The funding proposals prepared by the ATO for the black economy program and the Taskforce extension did not include any consideration of the methodology that would be used to measure revenue outcomes. Similarly, the ATO did not take into account the amount of baseline revenue that would have been raised in the absence of the measures.

Does the ATO have sound processes and practices in place to accurately monitor and report Taskforce revenue and other outcomes?

The ATO’s approach of attributing revenue using a percentage of total business service line budgeted resourcing does not necessarily provide an accurate indication of Taskforce output. Limiting factors include that compliance staff work on a mix of activities, budgeted resourcing may not match actual resourcing, and revenue from previous work is allocated to the Taskforce. The ATO has not reported revenue on the same basis as it was presented in the Budget measure — additional to existing revenue. Nevertheless, the ATO has implemented extensive monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Taskforce, including performance measures that link to corporate outcomes.

Revenue measurement

3.13 The ATO attributes compliance revenue to the Taskforce based on the percentage of budgeted business line resources that are funded by the Taskforce measure. As discussed in Chapter 2, the ATO adopted an apportionment methodology in relation to the Taskforce because it does not distinguish between Taskforce and BAU cases or staff. In respect of revenue apportionment, the ATO advised that:

As the majority of the business lines’ activities are directed towards addressing tax avoidance, and as cases are not considered to be either Taskforce or not Taskforce, the revenue attribution method adopted is an apportionment formula taking into account the proportion of resources provided to the Taskforce by Government.

3.14 There are a number of issues in using an apportionment method to determine revenue, including that:

- the time taken to finalise cases and collect compliance revenue results in revenue from past activities being attributed to the Taskforce29;

- the percentage of measure-funded FTE does not necessarily provide an accurate indication of Taskforce output, since compliance staff work on a mix of activities; and

- it does not adequately demonstrate the extent to which compliance revenue has increased due to the additional funding provided by the measure.

Moreover, if a pro rata apportionment method is used, it should reflect actual (rather than budgeted) staffing numbers.

3.15 The apportionment percentages are shown in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Percentage attribution of business service line revenue

|

Year |

Business service line |

Taskforce (%) |

Base (%) |

|

2016–17 |

PGI |

39 |

61 |

|

PGH |

N/A |

N/A |

|

|

2017–18 |

PGI |

45 |

55 |

|

PGH – Engagement and Assurance Services |

66 |

34 |

|

|

PGH – Aggressive Tax Planning |

46 |

54 |

|

|

2018–19 |

PGI |

47 |

53 |

|

PGH – Engagement and Assurance Services |

67 |

33 |

|

|

PGH – Aggressive Tax Planning |

56 |

44 |

|

Source: ATO.

3.16 For PGH in particular, the percentages used to determine the proportion of Taskforce-funded FTE do not reconcile with actual staffing information provided by the ATO. Figures provided by the ATO indicate that Taskforce FTE represented 33 per cent of total PGH FTE in 2017–18, while the Taskforce was credited with between 46 and 66 per cent of PGH revenue.

3.17 The ATO has the capability in its case management system to designate activities as being Taskforce-related and to monitor revenue on this basis, but does not do so. As discussed previously, the ATO chose not to distinguish Taskforce and BAU compliance activities.

3.18 The $3.7 billion forecast revenue to be raised by the Taskforce was additional to the revenue to be raised by PGI and PGH in the course of BAU activity. While it is clear that overall business line revenue has increased across the life of the Taskforce (see Table 3.6), it is not possible to accurately determine how much of this was facilitated by the additional Taskforce funding. The inability of the ATO to report Taskforce revenue on this basis is a significant weakness of the design of the measure and reduces transparency to the Parliament that funding appropriated for the activity has been used for its intended purpose.

Monitoring and reporting of Taskforce performance

3.19 The ATO has implemented reporting arrangements for the Taskforce, including annual outcomes reports, monthly Taskforce internal status reports, and monthly reports to the Minister on the Taskforce and cross-border activities.30 These reports provide detailed reporting about the operations and outcomes of the Taskforce.

3.20 The ATO has a set of high level outcomes for the Taskforce that link to corporate outcomes and reports against these on an annual basis. Each work stream under the Taskforce determines key performance indicators and reports against them during the project period.

Annual outcomes reports

3.21 For 2016–17 and 2017–1831, the ATO prepared a report against outcomes, drawing on information in monthly Taskforce internal status reports and other sources, to indicate the impact of the Taskforce over the previous year. The reporting has focused on the outcomes agreed by senior ATO staff in the months prior to the annual report being developed, as shown in Table 3.4. The 2016–17 and 2017–18 end of year reports describe improvements in each outcome area.

Table 3.4: Selected Taskforce annual outcomes

|

Outcome |

Source |

2016–17 reported results |

2017–18 reported results |

|

Community trust |

ATO Taxpayer Behaviour Survey. |

Perceptions of big business tax compliance improved slightly in the previous six months. |

There was some improvement in perceptions that the ATO is effective in making sure large companies pay the correct amount of tax.

|

|

Stakeholder perceptions |

Stakeholder feedback, including public statements. |

The Treasurer and Minister for Revenue and Financial Services publicly acknowledged Taskforce efforts.

|

The Senate Standing Committee on Economics commented positively the ATO’s efforts on corporate tax avoidance. Treasury and external stakeholders praised the ATO’s contribution to legislative design. |

|

Total revenue effectsa |

Total value of cash collected plus estimated wider revenue effects. |

The Taskforce delivered total revenue effects of $1.47 billion ($1.12 million in cash collected plus $344.1 million in estimated wider revenue effects).

|

The Taskforce delivered total revenue effects of $1.93 billion ($1.87 billion in cash collected plus $62.5 million in estimated wider revenue effects). |

|

Tax assureda |

Total value of tax assured under Taskforce programs. |

Tax assured under Taskforce programs totalled $2.3 billion.

|

Tax assured under Taskforce programs totalled $9.7 billion. |

|

Client experience |

Client surveys and feedback. |

Client feedback was generally positive. The ATO estimated red tape reduction would provide a saving of $23 million in compliance costs each year.

|

The ATO received an Australian Business Award for Service Excellence for its implementation of the MAAL. |

|

Cultural traits |

Australian Public Service Employee Census and staff feedback. |

Census responses from PGH were more positive for ATO cultural traits than the previous year.

|

Census results for PGI and PGH were broadly consistent with whole-of-ATO results.

|

|

Capability |

Taskforce capability assessment survey and team leader feedback. |

Targeted Taskforce recruitment contributed significantly to ATO capability.

|

There was a perceived improvement in staff expertise.

|

|

Consistency of case outcomes |

Team leader feedback. |

Better governance and validation processes contributed to more consistent decision making.

|

The quality and consistency of compliance decisions improved.

|

|

International exchanges of information |

Records of inbound and outbound information sharing |

Australia exchanged almost 400 rulings with 20 jurisdictions.

|

N/A |

|

Clever use of data |

Team leader feedback |

N/A |

The Taskforce Data and Analytics Vision was developed. Other supporting data initiatives were developed and realised. |

Note a: Reported figures were subsequently revised for the ATO annual report.

Source: ATO reports.

3.22 The Taskforce annual outcomes reports, monthly status reports and various other internal reports include information on revenue and other commitments to Government. The reports were prepared in a consistent and timely fashion, using information from a variety of sources (both internal and external) and were subject to a feedback and approval processes. While the overall reporting framework is sound, the value of the reports is diminished by the inability of the ATO to determine the work and revenue directly attributable to the Taskforce. Revenue figures are reported on different bases, and in some cases are inconsistent, across these reports.

3.23 Auditor-General Report No. 15 of 2016–17 recommended, and the ATO agreed, that the ATO should implement a consistent performance monitoring framework for compliance measures, including a comprehensive set of performance indicators and quality control of the calculations.32 The measures in the Taskforce annual outcomes reports and monthly status reports represent a performance monitoring framework, which is consistent in linking to corporate outcomes. The measures would benefit from additional targets or benchmarks and greater quality control over some calculations. The ATO advised it has undertaken further work to identify data sources and targets for each outcome. The ATO also plans to include an additional outcome — efficient management of program resources — in future reports to address issues raised by this audit.

Is Taskforce revenue to date consistent with Budget estimates?

Overall revenue raised by the relevant business service lines has increased considerably since the commencement of the Taskforce in 2016–17, including raising $6.3 billion in liabilities that year and $6.5 billion in the following year, compared to $3.3 billion in 2015–16. The ATO attributed a considerable portion of this revenue to the Taskforce, reporting that it had raised $5.5 billion in the first two years — which was nearly 150 per cent of the total four-year Budget commitment of $3.7 billion. However, the accuracy of this attribution is questionable. Without accurate attribution or a baseline comparator, the exact amount raised by the Taskforce cannot be verified. The Taskforce has delivered other non-revenue benefits, including the implementation of new legal and administrative tools designed to address tax avoidance.

3.24 The 2016–17 Budget measure forecast that the Taskforce would raise $3.7 billion over four years, in addition to the other revenue generated by PGH and PGI. As the value of this base revenue is not identified, it is not immediately clear whether the Taskforce has achieved this target.

3.25 Overall ATO revenue figures (such as those reported in the ATO’s audited financial statements) are taken from the Integrated Core Processing (ICP) system. This system contains a record of every credit and debit against a taxpayer’s account, but does not specify the reason for these. Tax owing due to a newly-filed tax return is recorded in the same way as an additional tax debt uncovered by a compliance audit.

3.26 The ATO therefore uses the liabilities and collections recorded in its compliance case management system (Siebel) to determine the amount of compliance revenue it has raised. To calculate Taskforce revenue, the ATO applies its apportionment methodology (see paragraphs 3.13 to 3.18) to selected overall PGI and PGH figures reported in Siebel. 33